Book contents

- Medieval Bruges

- Medieval Bruges, c. 850–1550

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Origins and Early History

- 2 The Urban Landscape I: c.1100–c.1275

- 3 Production, Markets and Socio-economic Structures I: c.1100–c.1320

- 4 Social Groups, Political Power and Institutions I, c.1100–c.1300

- 5 The Urban Landscape II: c.1275–c.1500

- 6 Production, Markets and Socio-economic Structures II: c.1320–c.1500

- 7 Social Groups, Political Power and Institutions II, c.1300–c.1500

- 8 Religious Practices, c.1200–1500

- 9 Texts, Images and Sounds in the Urban Environment, c.1100–c.1500

- 10 Bruges in the Sixteenth Century: A ‘Return to Normalcy’

- Conclusion: Bruges within the Medieval Urban Landscape

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

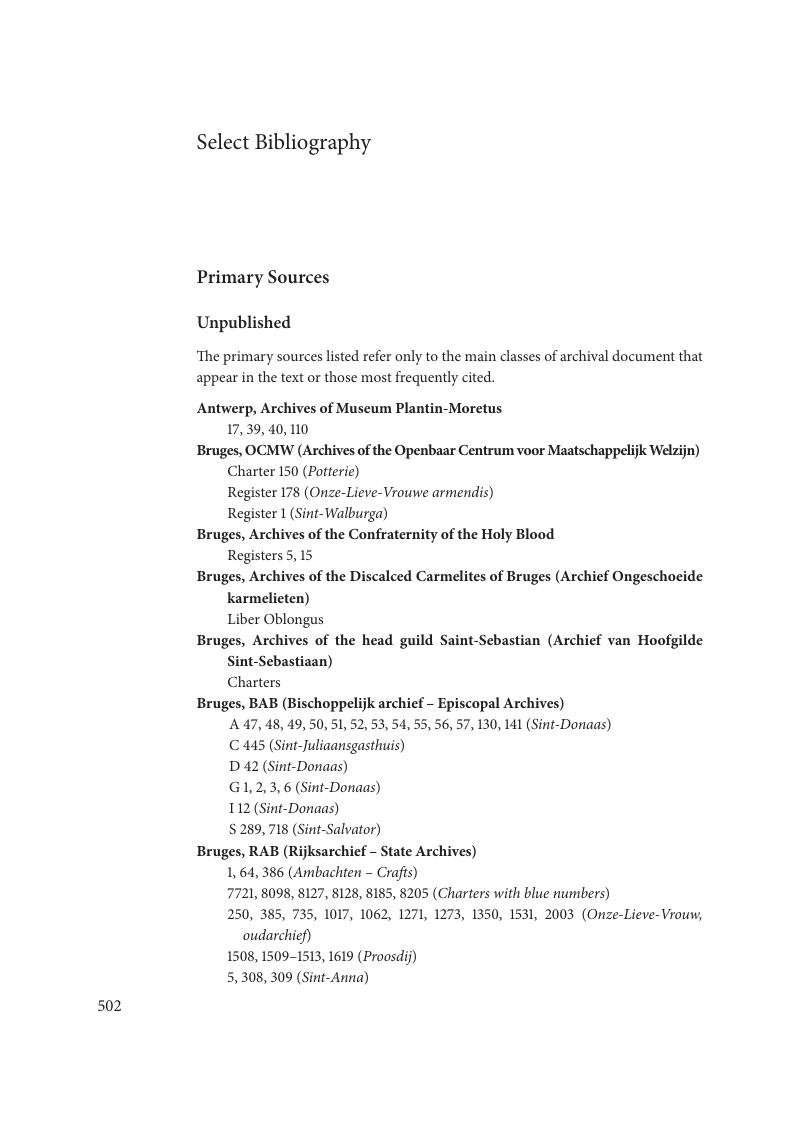

Select Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 May 2018

- Medieval Bruges

- Medieval Bruges, c. 850–1550

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Origins and Early History

- 2 The Urban Landscape I: c.1100–c.1275

- 3 Production, Markets and Socio-economic Structures I: c.1100–c.1320

- 4 Social Groups, Political Power and Institutions I, c.1100–c.1300

- 5 The Urban Landscape II: c.1275–c.1500

- 6 Production, Markets and Socio-economic Structures II: c.1320–c.1500

- 7 Social Groups, Political Power and Institutions II, c.1300–c.1500

- 8 Religious Practices, c.1200–1500

- 9 Texts, Images and Sounds in the Urban Environment, c.1100–c.1500

- 10 Bruges in the Sixteenth Century: A ‘Return to Normalcy’

- Conclusion: Bruges within the Medieval Urban Landscape

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Medieval Brugesc. 850–1550, pp. 502 - 528Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2018