Sometime in the 1330s, Le Tac (c. 1260s–c. 1340s), an elderly scholar living in exile in Hanyang, Hubei, in the Mongol-ruled Yuan empire, wrote a book about his native land, Annan zhilue/An Nam chi luoc (“A Brief History of Annan”). Le Tac had had an extraordinary political career: he served both the Tran dynasty of Dai Viet and, later, the Yuan dynasty of China. A career spent serving two dynasties often at war with one another was not without drama. As we shall see below, Le Tac, like others living through the turbulent late thirteenth century, faced a crisis of loyalty. We cannot be sure how he understood, or tried to resolve, the tension between opposed loyalties; Le Tac self-identifies as both a former subject of the Tran and a current subject of the Yuan, but does not comment on this dual identity. He treats as significant only a third self-identification: that of a participant in the larger world of classical culture. The preface to his book makes this clear:

This humble servant was born and grew up in Nan Yue. As undeserving as I am, I served the government [of the Tran dynasty]. In a period of ten years I travelled through most of the country, so I know a bit about its mountains and rivers. For more than fifty years I have been attached to the royal court [of the Yuan dynasty]. I am ashamed of my foolishness; all that I once studied is muddled and confused. In my twilight years I have delighted in books, regretting that it is too late: I will never be able to read all that I want from the past and present. I have collected histories of successive dynasties, atlases of Jiaozhi, and scattered classical allusions, and taking advantage of my leisure I have patched together A Brief History of Annan in twenty chapters, including a narrative of my personal experiences that I have appended at the end.Footnote 1

Le Tac is ashamed neither of his work with the Tran, nor of his even longer service to the Yuan. Indeed, he is proud of both. He is ashamed only at his inability to recall all that he learned in his youth, in his classical education, and in his service to two regimes. For all his humble protestations, Le Tac’s book achieved his goal of organizing and transmitting most available information on Vietnam from the earliest times to his own lifetime, and thereby submitting his bid for Annan’s inclusion in the northern canon. The great strength of A Brief History is that it drew on Le Tac’s personal experience while synthesizing the most important Chinese materials. His book remained an influential source on Annan within China for centuries. It is therefore an ideal starting point for contextualizing the history of Sino-Viet relations, since it set the baseline of knowledge about Vietnam for future generations of readers in China.

Piecing together the history of his country was no easy task. One reason was the challenge simply in establishing whose history he meant to write. Within the single paragraph of the preface quoted above, Le Tac refers to his homeland by the name of a second-century-BCE kingdom (Nan Yue), a Han-era province (Jiaozhi), and a Tang-era protectorate (Annan). This multiplicity of names for early Vietnam reflects the region’s shifting fortunes and borders, as the political control of northern states over the Red River Delta and its environs waxed and waned and weathered local resistance.Footnote 2 Each turn in fortune gave rise to a new name.

This chapter takes A Brief History of Annan as our guidebook and Le Tac as our guide to the entangled history of Sino-Viet relations up through the fourteenth century. I begin with Le Tac’s personal experience of the Mongol invasions to explain how multiple demands on his loyalty led him to work for the Yuan government. Even though it is the best contemporary account of the Mongol wars in Dai Viet, A Brief History of Annan’s liminal status as belonging fully neither to China nor to Vietnam has caused it to be overlooked as a source on the Mongol wars and their role in Sino-Viet relations. Indeed, despite the devastation caused by the Mongol invasions, and Dai Viet’s remarkable success in maintaining its northern border against Mongol incursions, the Mongol campaigns in Vietnam have received little attention from historians of the Mongols.Footnote 3 The chapter’s next section summarizes Le Tac’s own account of the history of Sino-Viet relations. Unlike many modern historians, he did not attempt to extricate “Vietnamese” history from “Chinese” history. I use his historical poem to contextualize and explain the many names used in China for Vietnam, each differing in their descriptive and critical overtones, and all of which will recur in later chapters. The subsequent section turns to Le Tac’s discussion of Vietnamese customs and their similarities to northern customs. This section of A Brief History of Annan had a riotous afterlife in quotations and misquotations by later Chinese and Korean literati, as we will also see in later chapters. I conclude the chapter by arguing that Le Tac’s writing was in part motivated by a desire to prove that southern history was worthy of inclusion in the historical record and that southern scholars were the equals of their northern counterparts. Le Tac’s life and life’s work illustrate the intertwined nature of Vietnamese and Chinese elite culture and the crisis of loyalty faced by those caught between political forces as northern control of Dai Viet ebbed and flowed.

Displaced by the Mongol wars

The armies of the Mongol empire attacked Dai Viet three times, in 1257, 1284, and 1287. These attacks, along with the Yuan conquest of what became Yunnan province, and Mongol-led campaigns against Burma and Champa, caused massive disruption throughout Southeast Asia. Relatively little attention has been paid to the Vietnam campaigns despite an abundance of written sources, primary among them Le Tac’s A Brief History of Annan. In studies of China or of the Mongols, it is recognized that fighting in Vietnam did not go well for the Mongols. Nevertheless, the campaigns are often treated as a success because tributary relations with Dai Viet were eventually resumed.Footnote 4 In contrast, Vietnamese historiography makes much of Dai Viet’s military victories over the Mongols, which support the idea of a Vietnamese people united in their struggle against foreign aggression. A Brief History of Annan brings to the fore three noteworthy aspects of the Mongol wars. First, the Mongols were not merely seeking tributary relations with Dai Viet along the lines of the Song dynasty. Their demands on the Tran government were unprecedented and far more onerous than typical demands or tributary missions and gifts by northern states. Second, the Vietnamese people were bitterly divided over how best to confront the Mongols. Third, Song refugees fled into Dai Viet in great numbers and played an important role in the resistance.

Le Tac’s tumultuous life illustrates all of these points. His story is buried in the back of A Brief History of Annan. Le Tac traces his ancestry to a northerner sent to the Red River Delta in the service of a Chinese dynasty: “I, Tac, am from Annan, a descendent of Nguyen Phu, the Prefect of Jiaozhou for the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420 CE).”Footnote 5 Le Tac’s family lived in Ai Chau (in present-day Thanh Hoa province along the North Central Coast of Vietnam) for generations, producing a series of court officials. His father passed examinations and became the Director of the Library during the Tran dynasty (1225–1400). Le Tac studied the classics from an early age and took the children’s examination before he was nine years old. He grew up, married a woman née Truong, and had every expectation of a life of scholarship and government service just like the long line of ancestors preceding him. This was not to be. Le Tac and his contemporaries were caught up in Dai Viet’s decades-long struggle against the Mongols, whose armies invaded Dai Viet three times in his lifetime.

The purpose of the Mongols’ first foray into Dai Viet, in 1257, was to open a southern front against the Southern Song dynasty of China. By this time, the Mongols had been fighting the Southern Song for more than two decades, and had already conquered parts of Sichuan and the kingdom of Dali in Yunnan in order to besiege the Southern Song from the west. A southern front, accessed through Dai Viet, would allow them to exert even more pressure on the Southern Song.Footnote 6 The Tran ruler Tran Du Tong opposed a foreign army crossing his territory, particularly to launch a military campaign against a Tran ally, the Southern Song. According to Le Tac, Tran Du Tong dispatched soldiers on elephants to chase the Mongol-led troops off. An eighteen-year-old Mongol general “directed sharpshooters to target the elephants. The terrified elephants turned and trampled them [the Tran army] and they were routed.”Footnote 7 After a Tran prince and countless others were killed, and the capital Dong Kinh (present-day Hanoi) destroyed, Tran Du Tong submitted. The following year, the Tran commenced regular diplomatic relations with the Mongol court, sending an embassy with tributary gifts of local goods.Footnote 8 By opening regular tributary relations with the Mongol court, the Tran treated the Mongols as equals to the embattled Southern Song dynasty without renouncing their ties to the Song.

This did not satisfy the Mongol ruler, Khubilai Khan. He did not wish to simply emulate the tributary relations between Dai Viet and the Song, which entailed receiving a tributary mission and gifts of local products from Dai Viet once every three years. He wanted instead a peaceful annexation of Dai Viet. This can be seen from the list of six demands he sent to the Tran in 1267. He demanded that the new Tran ruler, Tran Hoang, personally come to the Mongol court; that a son and younger brother or members of the younger generation of the royal family be sent as hostages; census records of Dai Viet’s population; Vietnamese soldiers to join the Mongol military; taxes; and Tran acceptance of a darughachi (a local commissioner or governor) to be stationed in the capital Dong Kinh to oversee the government. According to Khubilai, only this would “demonstrate the sincerity of your adherence.”Footnote 9 These demands outlined a relationship markedly different than that of Dai Viet and the Song dynasty or the later Ming dynasty.Footnote 10 Not only would Dai Viet be expected to pay taxes to the Mongols in both money and labor, to be checked against the census rolls, but they would have to accept direct oversight from a Mongol-appointed darughachi. Although Dai Viet was accustomed to sending tribute to the Song every three years, they received valuable gifts in return and the tribute missions were a lucrative trading opportunity. Khubilai Khan had a different vision, one more in line with Mongol customs than with Chinese tradition. He even submitted specific requests for the content of the tribute. He asked for “incense, gold, silver, cinnabar, agarwood, sandalwood, ivory, tortoiseshell, pearls, rhinoceros horn, silk floss, and porcelain cups.” In addition, he wanted the Tran government to send its two most virtuous scholars, talented doctors, beautiful women, and skilled artisans every three years.Footnote 11 The Tran government demurred, and evaded outright conflict only while the Mongols were otherwise occupied fighting the Song in China.

In 1271, the Mongols established the Yuan dynasty. Within the decade, the Song dynasty fell. Thousands of Song refugees flooded into Dai Viet, some settling in Dong Kinh, others eventually swelling the ranks of the Tran armies.Footnote 12 It is likely that the Song refugees brought military technology with them, most notably a gunpowder “fire-lance” that shot arrows from an ironwood tube.Footnote 13 This weapon “was almost certainly the direct precursor of true firearms.”Footnote 14 Despite these ingenious weapons,Footnote 15 the Yuan dynasty overthrew the Southern Song dynasty in 1276, asserting Mongol control over all of China. Dai Viet now shared a border with Khubilai Khan’s Yuan dynasty.

Alarmed by the destruction of their neighbor and erstwhile ally, the Tran state warily watched the border. Khubilai Khan’s aggressive demands and the frequency of diplomatic contact was a new situation for Vietnamese rulers. Mongol penetration of the Sino-Viet borderlands brought the South into closer contact with the northern state. Even though parts of northern Vietnam had been loosely controlled by northern states in the past, the Tran state was suddenly in much more direct contact with the northern court than before.Footnote 16 Following their conquest of the Song, the Yuan court renewed their unprecedented demands on the Tran dynasty, and complained that Tran Hoang sent inferior tribute gifts and did not treat edicts from the Yuan with the proper decorum and respect. In turn, Tran Hoang complained that the tribute demands were burdensome and that Annan would be a laughingstock for having a darughachi, as if it were some kind of small border tribe rather than a state. In 1278, Tran Hoang retired and his son Tran Kham took the throne. The Mongol court demanded that Tran Kham personally visit Beijing. Moreover, they sent an edict to Tran Kham that threatened that if he did not at last obey the six demands and personally visit the Yuan court, then he had better “strengthen the city walls and put the military in order, to await the arrival of our army.” Tran Kham responded that he had spent his life in the seclusion of the palace, was not used to riding a horse, and could not handle the hardships of the road. When he had still not complied two years later, the Yuan court sent him a letter that read, “If you cannot come in person, then send a gold statue to represent your person, with two pearls to represent your eyes, as well as virtuous scholars, doctors, children, artisans, two of each, to represent the local people. If not, repair your walls and moats, and await your trial and execution.”Footnote 17

In 1283, Khubilai Khan sent word to Tran Kham that he intended to send Yuan armies across Tran territory in order to attack the Tran’s southern neighbor, the kingdom of Champa. Khubilai Khan was not requesting permission; he was demanding that the Tran contribute provisions and other support to the Yuan army. Tran Kham refused. Khubilai appointed his eleventh son, Toghan, to lead the offensive, granting him the title “King of the Suppressed South” (Zhennan wang). Toghan led troops overland while the Mongol general Sogetu led troops by sea through a southern route, from Champa. In the winter of 1284, Yuan armies crossed the border into Dai Viet and were attacked by Tran troops led by the royal prince Tran Hung Dao.Footnote 18 The Yuan troops overcame their resistance and progressed to Dong Kinh, occupying the abandoned palaces. According the the History of the Yuan (Yuan shi), they killed many Tran subjects and captured others, including high officials of the fallen Southern Song dynasty.Footnote 19

At this time, after several years of government service, a twenty-something Le Tac was assigned to assist the royal prince and military commander Tran Kien in the field. Tran Kien was a nephew of the senior emperor, Tran Hoang. Le Tac described Tran Kien as tall, studious, modest, generous, good with a bow and arrow, and interested in military books.Footnote 20 In 1285, Le Tac accompanied Tran Kien, along with tens of thousands of troops, to resist the Sogetu in Thanh Hoa. By this point, Tran Kham had fled, Dong Kinh had fallen, and several Tran generals had been killed by the Mongols. The fighting at Thanh Hoa did not go well for Tran Kien and his troops. Le Tac wrote that “our endurance was weakening and we were cut off from support.”Footnote 21 They did not know if Tran Kham was alive or dead. Tran Kien assessed the situation and decided that facing danger day and night in such uncertain times would be “perverse.”Footnote 22 He said, “The small should not antagonize the large, the weak should not antagonize the strong. Weizi [of the Song state of the Eastern Zhou period] returned to Zhou, this was good and logical. I am the grandson of the ruler, how could I bear to see the country overturned and lose my life?” Then he surrendered to the Yuan. Le Tac and the rest of the soldiers joined him. Tran Kien was not alone in choosing to throw his lot in with the Yuan. Several other Tran princes surrendered as well, bringing their battalions with them, most notably Tran Ich Tac, the emperor’s younger brother.Footnote 23

Several factors contributed to the large number of the people who capitulated to the Mongols. Since the time of Khubilai’s grandfather, Genghis Khan, the Mongol military juggernaut had reshaped the Eurasian world. Not confined to the north and northwest, the Mongols presided over unprecedented penetration into southwest China and Southeast Asia. Their recent conquest of the Southern Song would have had a profound effect on Vietnamese observers, as would have Mongol campaigns as far afield as Champa and Burma. In 1285, Mongol conquest must have looked inevitable to many, and surrender the only way to ensure survival.

It is also possible that Tran Kien and other high-ranking defectors were hoping to increase their own power, or even find a way to claim the throne of Dai Viet for themselves with Yuan support. For the historian Keith Taylor, Tran Kien’s surrender is indicative of the divisions and resentments within the Tran royal family. Tran Kien’s grandfather, though the eldest son, had been passed over in the line of kingship, removing his sons and grandsons, including Tran Kien, from direct succession. Due to a rift with Tran Kham’s son, Tran Kien had “used studying Zhuangzi and Laozi as a pretext to live in seclusion.” This was the very year he was called upon to fight the Yuan troops.Footnote 24 In Taylor’s view, a “disgruntled” Tran Kien, “unable to overcome the store of resentment he had been nursing for years,” opted to join the Mongols and even to serve them as a guide.Footnote 25 Le Tac gives indirect evidence for this tension within the royal family in his book, mentioning in a section on annual customs that “On the fourth day of the fourth month, the sons and younger brothers of the royal family and the palace eunuchs gather in the Mountain Spirit Temple to swear that they are not hatching revolutionary plots.”Footnote 26 The Tran rulers had good reason to fear internal threats to their power. These divisions were made clear when some chose resistance to the Yuan and others chose collaboration. Perhaps Le Tac hoped to replace the Tran emperor with a different member of the royal family and therefore viewed Tran Kien’s actions as justified. He wrote that Tran princes were motivated to surrender to the Yuan because they “admired justice.” Though this may be dismissed as the sort of praise demanded of a document submitted at the Yuan court, he also described the actions of the Tran ruler Tran Kham as selfish and cowardly, and may well have harbored resentment for the way Tran Kien’s troops – including himself – were stranded without backup forces: “The king [Tran Kham] fled to the ocean and hid himself in the forest, leaving the innocent to endure hardship for his crime.”Footnote 27 He describes Tran Kham as panicking and throwing Tran Kien into the fray, because he had no other plan for conducting the war.Footnote 28 After Tran Kien surrendered, Tran Kham sent messengers to sue for peace, but refused the Yuan request that he do so in person, a decision Le Tac presents in a negative light.Footnote 29 In this way, whether through fatalism, guile, or a sincere desire for a change of leadership within the Tran family, a great number of Tran subjects “failed the test of loyalty” during the Mongol invasions.Footnote 30

Following his surrender, the Mongols rewarded Tran Kien and arranged for him to travel to Beijing for an audience with Khubilai. Tran Kien and his entourage had not made it as far as the border when some local chieftains allied with the Tran state launched a fierce and unexpected attack against the Yuan troops and their entourage.Footnote 31 Le Tac described how the two sides skirmished throughout the night. Tran Kien was killed in his saddle. Le Tac held the body of his deceased leader before him on his own horse and galloped away from the battle, burying Tran Kien tens of miles away at the border town of Khau On in Lang Son.Footnote 32 By the time the battle ended, according to Le Tac, half of Tran Kien’s subordinates had been killed.Footnote 33 Unable to return home, Le Tac joined the tattered Yuan battalion in their retreat and went north to Beijing. His period of wandering had begun.

The Yuan decided to deal with the uncooperative Tran Kham by appointing their own “King of Annan” from afar. They chose Tran Ich Tac, a younger brother of the Tran emperor, who had already surrendered and was willing to enter Dai Viet at the head of a massive Yuan army. This army was divided into three divisions led by the generals Omar, Zhang Wenhu, and Aoluchi, under the general command of Toghan. They would again attempt a pincer movement, attacking overland and by sea. The soldiers were drawn from Mongols, Han Chinese, Guangxi indigenes, and members of the Li tribe of Hainan island. The latter two groups would presumably have fared better in the humid and malarial conditions of northern Vietnam. In 1287, a massive navy advanced overseas from the southern port of Qinzhou, the other divisions advancing overland from Guangxi and Yunnan.Footnote 34 Le Tac joined the overland group, though illness detained him from the front lines and probably saved his life.

After initial successes, including once more occupying and looting the capital, Toghan made the decision to retreat with the forward troops. By this time, Le Tac had crossed the border into Dai Viet along with a column of nearly five thousand Yuan soldiers.Footnote 35 Le Tac recounted that the Yuan forces advanced to the Binh River and stood their ground against the Tran army. The battle raged all day and through the night. The Tran fought fiercely and rained poisoned arrows on their foes. The worn-out Yuan troops were routed. During the night, Toghan himself was struck with a poisoned arrow and several thousands of troops got lost in the unfamiliar terrain and were not heard from again, presumably picked off by hidden Tran soldiers. The remnants of the great army followed Le Tac, the only person familiar with the terrain, to safety in the north. Those who fell to the end of the retreating column were at risk of falling prey to the Tran troops. Le Tac, noticing that the nine-year-old son of Tran Ich Tac, Tran Duc, was nearly captured, gave him his own fresher horse. They raced along through the night, with Le Tac whipping the horses on from behind, evading a number of attacks. They reached safety at midnight on lunar New Year’s Day, 1289, congratulating one another on their narrow escape. Le Tac resigned himself to fate, telling his companions, “Whether I live or die is Heaven’s will.” Many of his companions were not so lucky; Le Tac claimed, surely hyperbolically, that ten thousand died between the mountain passes of the Sino-Viet borderlands.Footnote 36

Prevented from going home, Le Tac accompanied Yuan soldiers on their patrols of the border for three months. When the troops were withdrawn in advance of the malarial season, Le Tac went north with them. As late as 1293, the Yuan government planned a fourth campaign to install Tran Ich Tac. When Khubilai died early in 1294, interest in the project died with him. Le Tac, now stranded in the North, was granted a sinecure by the Yuan government and appointed to the symbolic position of the Prefect of Pacified Siam (tongzhi Anxianzhou). After ten years in China, Le Tac remarried, noting that his “mother and father and family had been scattered by war” and were not traceable. This second wife was a descendent of the former Ly royal family of Dai Viet. Like Le Tac, members of the Ly family were displaced by the war in Dai Viet and relocated in China, surviving on land granted to them by the Yuan.Footnote 37 Tran Ich Tac also lived out the rest of his life in the community of Dai Viet exiles in Hanyang, Hubei province. In addition to Vietnamese exiles, some former subjects of the Southern Song who had fled into Dai Viet to avoid the Mongols, only to surrender or be captured along with Tran Kien, now lived in this exile community. Le Tac mentions two such friends, the Song scholar Mi Kai and the high-ranking Song official Seng Yuanzi. Mi Kai lived out the rest of his life with Le Tac in Hubei.Footnote 38

Did Le Tac regret surrendering? Did he join the Yuan by choice or by necessity? He does not tell us. On the one hand, in the course of performing his duty to the Tran court, a chain of events pushed him irrevocably away from home and family. He attempted to return with the Yuan forces in 1287, but Tran resistance made it impossible. On the other hand, Le Tac may have truly wished to depose Tran Kham and replace him with a member of a different branch of the Tran family. Perhaps Le Tac felt that his country’s current disorder would be best resolved by this compromise: enthroning a Tran family member who already had the Yuan’s support. Though he surely adopted a northern perspective in his writing in part to fit the expectations and viewpoint of his patrons, he expressed genuine frustration that Tran Kham broke the Tran-Yuan détente by refusing passage to Champa through Dai Viet in 1284. Perhaps he saw the bloodshed and displacement that he witnessed as preventable. If so, the origin of Le Tac’s tragedy of dislocation was in his backing of the losing side of an internal dispute.

The three Mongol wars are now remembered within Vietnam and Vietnamese historiography as prime examples of Vietnamese resistance to foreign aggression. The third invasion was the scene of one of the most celebrated victories in Vietnamese history: the 1288 battle of Bach Dang River near Ha Long Bay. First, unbeknownst to the Mongol troops already in Dai Viet, the Tran destroyed the Mongol supply fleet at sea. Toghan’s land forces and Omar’s navy waited in vain for the arrival of provisions before beginning their retreat from Dong Kinh. Then Tran forces led by the royal prince Tran Hung Dao ambushed the Mongol fleet at Bach Dang estuary. Tran Hung Dao’s troops hid metal-tipped wooden stakes beneath the waterline and then set upon the Yuan fleet impaled on the stakes. The Yuan fleet was obliterated.Footnote 39 The land troops, including those that accompanied Le Tac, were unable to receive supplies and fled in disarray.

Tran Hung Dao is today commemorated on the 500 dong note of the Republic of Viet Nam, as well as in statues and street names across the country, and even venerated as Saint Tran.Footnote 40 If Tran Kien represents all those who saw a better future in surrendering to the Yuan, Tran Hung Dao is the most famous of the many who preferred to stand and fight. Tran Hung Dao was Tran Kien’s uncle, with an even stronger claim to the throne than Tran Kien, a fact that makes his loyalty even more remarkable. Examples of resistance to northern invasions are immortalized in books as disparate as the fifteenth-century Dai Viet su ky toan thu (“Complete Chronicles of Dai Viet”) and Tran Trong Kim’s still-influential 1920 Viet Nam su luoc (“An Outline of Vietnamese History”). A recent book rightly notes, “The Vietnamese are to this day very proud of the fact that they found themselves among a very small number of people in the world to have been able to successfully resist the onslaught of the Mongols.”Footnote 41 This sentiment, though entirely justified, overlooks the thousands of people who, like Le Tac, chose or were forced to surrender to the Yuan and even resettle in China.

A Brief History of Annan gives insight into the dilemma of those thousands. The book is undoubtedly the best account of the Mongol wars in Vietnam, but it is also problematic, written as it was by a Vietnamese exile beholden to the Yuan court. It highlights the difficulty of researching Vietnam in this time period; many surviving sources were written from a northern perspective, or else influenced by regional tensions within the expanding country of Dai Viet. Le Tac lived through the events and paid a high personal price. He knew intimately the loss of life and displacement and the deep divisions in Tran society that were exposed by the fighting. Although Le Tac wrote frankly of the death toll and dispersion caused by the Mongol campaigns in Annan, he still employed a triumphalist rhetoric that presumed the justice of Yuan actions. Likewise, Yuan sources or sources written from a perspective sympathetic to the Mongols, unsurprisingly, treat the Vietnam campaigns as a success.

In truth, the campaigns were an unmitigated disaster for the Yuan. Although Dong Kinh fell to the invaders three times, each time the occupiers discovered the royal family as having fled, the capital city evacuated, and food in short supply. Tran forces employed the tactics of guerrilla warfare, melting away as the Yuan troops advanced, and reappearing to harass the Yuan forces once they were tired, distracted, attenuated, or in retreat. In the words of the Persian historian Rashid al-Din, a contemporary of Le Tac, “there are forests and other places of difficult access … On one occasion, [Toghan] penetrated with an army to those towns on the coast, captured them, and sat for a week on the throne there. Then all at once their army sprang out from ambush in the sea, the forest, and the mountains and attacked Toghan’s army while they were busy plundering.”Footnote 42 The Tran emperor and his sons fled on boats and could not be found. During the second campaign, Sogetu died in battle, and of the men under his command, five or six out of ten drowned.Footnote 43

Mongol troops struggled in the tropical climate, unused to heat and humidity and unseasoned to tropical diseases such as malaria. The dense forests of the South hindered the movement of their horses. The humidity caused their wooden crossbows to swell and fire off course. It was a miserable experience.Footnote 44 Although Mongols are famed today for their use of psychological warfare, the general Omar was disturbed by the boldness of captured Tran soldiers who tattooed “Kill the Tartars” (sha Da) on their arms.Footnote 45 This tactic may have been picked up from the refugee Song soldiers in their midst, for whom coerced military tattoos, sometimes containing military slogans, were part of life in the ranks.Footnote 46 Even after these costly campaigns in difficult conditions, the Yuan were able to neither extend their borders into Dai Viet nor place their puppet emperor on the throne.

Le Tac was aware that relations between the Yuan and Tran Dai Viet were normalized following Khubilai Khan’s death in 1294, and yet he stayed in China.Footnote 47 It is likely that Le Tac did not return because the Tran dynasty was still in power and he feared being punished for treason. Perhaps he feared that his family had been killed. His clearest expression of regret and resignation comes at the end of his personal narrative: “Grieved that I could not go back, I purchased a gravesite on Phoenix Pavilion Mountain [in Hubei].”Footnote 48 His Brief History of Annan was his attempt to preserve his memories and historical research on Annan before they died with him.

From Jiao to Annan

The early history of Vietnam was mainly recorded in literary Sinitic by northern authors, making it exceedingly difficult to uncover non-imperial points of view from textual sources. Le Tac’s book is noteworthy because it is the earliest extant work on Dai Viet by a Vietnamese author.Footnote 49 Though written by a southerner, A Brief History had to be written from a northern, Yuan perspective to suit Le Tac’s patrons. And not only did Le Tac write his history of Annan for Chinese (and Mongol) readers, but he also wrote it from Chinese sources. Le Tac drew on a range of classical texts, especially the Book of Rites (Liji, dated to the Warring States), Records of the Historian (Shiji, c. 109–91 BCE), History of the Former Han (Han Shu, 111 CE), and the History of the Later Han (Hou Han Shu, fifth century CE). Thus, while Le Tac’s book stripped out some of the more exotic, far-fetched, or prejudicial views of Dai Viet,Footnote 50 it largely presents what information about Dai Viet was already available to northerners in the fourteenth century. Thanks to the enduring availability and interest in the book, A Brief History helped fix certain tropes of Dai Viet, even as that country was changing in unexpected ways, and served as the basis of knowledge about Dai Viet within China for centuries to come.

Le Tac tells the history of his country in A Brief History of Annan in a variety of ways. The most exceptional is his poem “Verses on Geography,” consisting of one hundred seven-syllable rhyming lines. The poem is the only place in the book where Le Tac gives a narrative account of Vietnamese history. By limiting himself to one hundred lines, he allows us to see the events he deemed most important to Vietnamese history. The poem breaks into five topical sections: the early history of Vietnam; the rise and fall of the Nan Yue kingdom; the rebellion of the Trung sisters; the fall of the Tang and the rise of independent Vietnamese states; and the recent history of the Tran and Yuan.

Below, I will use excerpts of “Verses on Geography” to outline Vietnamese history as mediated through Le Tac. Rather than explicating a complete history of early Vietnam, this section will establish the sum of textual knowledge about the Red River Delta region and its environs in Le Tac’s lifetime. This helps contextualize the ways in which Dai Viet was described in China at that time. In particular, Le Tac’s poem can help us to understand some of the most common names applied to Vietnam and the Vietnamese people by those writing in literary Sinitic, namely Man, Yi, Jiao, Nan Yue, and Annan.

First, Le Tac situates the early history of Vietnam. He introduces nine names for the South and its people and covers more than two thousand years in just eleven lines:

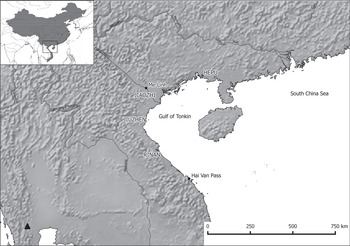

Le Tac begins his poem by delineating the borders of Annan, defining it as the territory between Yunnan, Guangxi, and Guangdong to the north and the kingdom of Champa (in present-day southern Vietnam) to the south.

Jiaozhi, Yuechang, Xiangjun, Jiaozhou

The most important function of these first lines, though, is to gather several names for early Vietnam within a single frame, and to assert their co-antiquity with the North. He does so by naming two of the North’s cultural heroes, the legendary King Yao (third millennium BCE) and the Duke of Zhou (eleventh century BCE), a sage regent and Confucian hero. The Hou Han Shu records that during the early Zhou, a kingdom called Yuechang (VN: Viet Thuong) sent tribute to China. Later, this perhaps legendary kingdom came to be associated with northern Vietnam. When the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) unified the central states of the Yellow River plain, it also claimed control of parts of Vietnam under the evocative name Xiangjun (VN: Tuong quan), literally “elephant commandery.”Footnote 53 During the reign of the Han dynasty emperor Wudi (140–87 BCE), Jiaozhi (VN: Giao Chi) became one of the thirteen circuits of the Han empire, and included Guangdong, Guangxi, and northern Vietnam, all south of the Five Passes. In the Eastern Han (25–220 CE), the name Jiaozhi was changed to Jiaozhou.

Man and Yi

Le Tac also brings up two of the most contentious terms in all of Chinese history: Man and Yi. These terms, singly or together, are most often translated as “barbarian.” This translation is not without controversy, sparking academic debate and hurt feelings. Whether treated as two separate terms (Man and Yi) or as the compound Man Yi, this was a Chinese exonym rarely if ever adopted as an autonym. Although Le Tac here relegates the name to the past, in truth it had currency in China as a way to refer to southerners and foreigners even through the nineteenth century. For that reason alone, it is worth exploring the origin and connotations of Man and Yi.

Man and Yi were two of the four names that had been in common use since the Warring States (475–221 BCE) to refer to people beyond the borders of Chinese states. Man, Yi, Rong, and Di referred respectively to peoples of the South, East, West, and North. All contrast explicitly with Hua, literally “florescence,” an early term for the location and culture of what we now call China.

In using the terms Man and Yi to designate the inhabitants of the South, Le Tac invoked the earliest texts of the Sinitic canon. The Book of Documents (Shang Shu, possibly fifth century BCE) provides a spatial understanding of the Sinic world, with the Man, Yi, Rong, and Di at the outer fringes. According to this “five-zone theory,” the central royal domain was surrounded by concentric rings of domains whose cultural and political connections to Hua decreased as one moved farther from the center. The central domain was encircled by the noble’s domain, followed by the pacified zone. The Man and the Yi lived in the fourth zone, the controlled zone, while the Rong and the Di were located in the outermost wild zone. From the Hua perspective, the farther a region was from the center, the less civilized its inhabitants were. The Warring States period Book of Rites further identifies the Yi and Man, their location, and their differences: “The Eastern region is called Yi. They wear their hair loose and tattoo their bodies. Some of them do not cook their food. The Southern region is called Man. They tattoo their faces and intertwine their feet (jiaozhi). Some of them do not cook their food.”Footnote 54 Although what the author meant by intertwining feet is unclear, the supposed Man trait of “jiaozhi” became a place name for the Red River Delta region.Footnote 55 Indeed, it is the Jiaozhi of Le Tac’s line “Jiaozhi has existed since the time of the sage king Yao.” Although ancient by the Ming, these lines were often invoked in Chinese texts that purported to introduce readers to Annan.Footnote 56

In their most basic senses, then, the terms Man and Yi implied not only compass direction but also geographical distance and cultural difference. They implied political difference too: Man and Yi, not to mention Rong and Di, were outside of the authority of the Hua state. Because the terms Man and Yi had both locational and cultural-political dimensions, their connotations could range from the relatively neutral (non-Hua) to the outright pejorative (barbarian).Footnote 57 In this light, we can reassess the Jiaqing emperor’s statement in 1802, as we saw in the Introduction, that his Vietnamese counterpart was just “a little Yi from a marginal area.” Whether the term Yi implied that Nguyen Phuc Anh was a barbarian or just a foreigner, he clearly meant that the Nguyen state was too insignificant and too foreign to claim the ancient name Nan Yue.

Although Le Tac uses it here, Vietnamese writers generally used neither Man nor Yi as an autonym. This particularly applies to Man, which had a more pejorative tendency than Yi. Stark evidence for this is the Vietnamese adoption of the word Man as a negative term for highland (non-Vietnamese) people.Footnote 58 On the surface, then, it may seem surprising that Le Tac uses with no irony the potentially pejorative terms Man and Yi to describe the inhabitants of ancient Vietnam. This is perhaps explainable by an appeal to Le Tac’s loyalties. Although he identifies himself as Annanese, Le Tac does not see the Man and Yi as constituting that, or his, identity. In fact, he traces his own origins not to southern indigenes but to northern elites, starting from the prefect Nguyen Phu of the northern Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420). Northern elites and their descendents, himself included, are the subject of his inquiry, not the highland dwellers both states labeled Man and Yi. When Man and Yi do make a rare appearance in Le Tac’s book, they are relegated to Dai Viet’s past or margins.

The word Jiao, originally used in the context of jiaozhi (“intertwining feet”) in the Book of Rites, persisted as a Chinese term for Vietnamese people (jiaoren) throughout the late imperial period. Le Tac uses the term to refer to people from his region, the heartland of ancient Vietnam near present-day Hanoi. Late imperial Chinese texts used the term with less precision to refer to Vietnamese people in general, especially when they wished to highlight place of residence over political and cultural difference. When they wished to emphasize the latter, they would use terms such as Man or Yi.

Jiuzhen and Rinan

Le Tac makes clear that there were divisions between Jiao and the surrounding areas: Cuu Chan and Nhat Nam were adjacent to it. It is illuminating that Le Tac distinguishes Cuu Chan (Ch: Jiuzhen) and Nhat Nam (Ch: Rinan) from Jiaozhou. Jiuzhen and Rinan were south of Jiaozhou, in present-day central Vietnam. Jiuzhen corresponds to present-day Thanh Hoa and Nghe An provinces, and Rinan to the region just north of the Hai Van pass, including the city Hue. He shows in several parts of his book that he most identifies with the dwellers of the Red River Delta region, the area historically most linked to Chinese states. In Le Tac’s time, regional differences and identity were strong.

The second section of “Verses on Geography” is devoted to the Nan Yue kingdom (204–111 BCE). Le Tac, like Nguyen Phuc Anh five centuries later, clearly saw Nan Yue as centrally important to the history of Annan.

When the Han dynasty came to power in 206 BCE, it was not initially able to incorporate what had been the Qin’s southernmost commandery. During the chaos of the Qin-Han transition, Zhao Tuo (240–137 BCE), an official posted to the South by the earlier regime, rose to prominence. Taking advantage of the weakness of the new Han state, Zhao Tuo declared himself king of the Nan Yue kingdom. The first Han emperor, Han Gaozu, opted to recognize Zhao Tuo’s kingship, rather than imperil his fragile new state by declaring war with Nan Yue. Later, when Empress Lu imposed an embargo on trading iron to Nan Yue, Zhao Tuo declared himself the “Martial Emperor of Nan Yue,” in defiance of the Han emperor’s exclusive claim to the title emperor (di). Zhao Tuo extended his territory farther to the west, and began riding in a yellow carriage and issuing “edicts” in imitation of Han imperial practice. The Zhao family continued to rule Nan Yue after the death of Zhao Tuo, until internal unrest in Nan Yue attracted the attention of a newly expansive Han dynasty. In 111 BCE, the armies of the Han destroyed Nan Yue and incorporated its territory under Han rule, bringing parts of northern Vietnam under central Chinese rule for the first time.Footnote 61 The story of Nan Yue established enduring Chinese tropes about Vietnam: its rebelliousness; reliance on remoteness to oppose central control; usurpation of Chinese imperial prerogatives and symbols; and appeasement to avoid Chinese military intervention. Le Tac transmitted and confirmed these tropes by including them in his poem.

It is curious that in the first line of his preface, Le Tac identified himself as one born in “Nan Yue,” a kingdom that had been defunct for more than a thousand years.Footnote 62 What can this mean? On a surface level, it reflects the lack of precision and specificity of place names for the South that was still common in the fourteenth century. On a more significant level, it may signal Le Tac’s hybrid identity, and his intellectual goal of uniting the South and North through a unified Sinitic history. He did so by affiliating himself with Nan Yue, a kingdom that crossed the border of both states.

Le Tac’s recounting of the Nan Yue story, based on the History of the Han and the Records of the Historian, demonizes Zhao Tuo as a rogue minister and rebel. In Le Tac’s telling, Han conquest had the positive result of transforming the Man and Yi of the borderlands to subjects of the northern state. “Central Florescence” refers to China, specifically the Han dynasty, the first official sponsor of what came to be classical culture. Here, Le Tac employs the standard rhetoric of a civilizing mission, dating the transformation of the Vietnamese people to the fall of Zhao Tuo’s culturally hybrid Nan Yue state.

After accounting for the rise and fall of Nan Yue, Le Tac turns to the period of Vietnamese history commonly called “the period of northern domination” (Thoi Bac thuoc). He devoted a significant portion of this section to the 42 CE rebellion of the Trung sisters against the Han dynasty:

As with Zhao Tuo, Le Tac presents the Trung sisters in a negative light. The background information he provides follows the historical record closely: northern Vietnam entered the Han orbit more firmly when the Han general Ma Yuan, the “wave-quelling general,” put down the rebellion of the Trung sisters in 43 CE. The sisters, Trung Trac and Trung Nhi, started their insurrection at the upper edge of the Red River plain in protest of the corrupt rule of their Han overlords. According to legend, after defeating and executing the sisters, Ma Yuan melted down enemy weapons, and with the metal erected bronze pillars to mark the southern limit of the Han empire.Footnote 64 These pillars, though quite possibly legendary, were of enduring interest to Dai Viet watchers. Indeed, in 1272, the Yuan ruler Khubilai Khan sent an ambassador to inquire about the location of the pillars, perhaps in an attempt to determine where the border lay. He was told that no traces of the pillars remained.Footnote 65

As the first in a long line of heroic resisters to foreign aggression, Trung Trac and Trung Nhi have remained a heroic archetype of unity and resistance within Vietnam.Footnote 66 It is noteworthy that Le Tac devoted twelve lines of his poem to their rebellion. Although she does not make an appearance in the “Verses on Geography,” in chapter fifteen under the category “Rebels,” Le Tac tells the story of another female rebel, Lady Trieu. This is also the section where he first addresses the Trung sisters. Lady Trieu never married, and her breasts grew to the fantastic length of 3 chi, so she flung them over her back to keep them out of her way. She lived in the mountains, led a pack of bandits, and fought from the back of an elephant before she was caught and executed.Footnote 67 Le Tac’s treatment of Lady Trieu is not flattering, though some historians interpret her mere inclusion, along with that of the Trung sisters, as a subtle sign of his pride in Vietnamese resistance to northern aggressors.Footnote 68 In fact, he presents these women as subversive and unnatural. Lady Trieu was a physical freak. He notes that one of the Trung sisters was king and the other commander – a comment that should not be mistaken for praise coming from a male scholar of his time and place.

Once the rebellions of the Trung sisters and Lady Trieu were put down, Jiaozhi settled into a long period of relative peace. Local families like that of Si Nhiep exercised hereditary rule, with little direct interference from a progression of northern dynasties of which they were a nominal part.Footnote 69

In the next section of the poem, condensed below, Le Tac narrates the dissolution of the great Tang dynasty and its province of Annan and the rise of independent Vietnamese states:

After centuries of lax northern control, the powerful Tang dynasty (618–907) reasserted control of the South and renamed it “Annan,” literally “the secured South.” Although Le Tac uses Annan in the title of his book, the name was not commonly used within Dai Viet. It was very much a Chinese term for Dai Viet, popular up to the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century, French colonists adopted the Vietnamese pronunciation of the name, Annam, to refer specifically to central Vietnam, ensuring the persistence of this relic of Tang imperialism. After the dissolution of the Tang dynasty, Annan achieved outright political independence in 939 as the state of Dai Co Viet. Although Le Tac does not mention it, Dai Viet was reclassified at that time as a fan, or tributary state, rather than an administrative unit of China.

Le Tac ends his account of the rise of independent Vietnamese dynasties by noting the spread of classical culture. The shorthand of “rites, music, and robes and caps” would be invoked again and again by southern scholars who wish to demonstrate their affinity to their northern counterparts.

The longest section of the poem covers Le Tac’s own life and times, the Tran dynasty, its relations with the Yuan, and Le Tac’s current situation:

Rather than focusing on it as a cause of war, death, and displacement, Le Tac presents the Yuan invasions as bringing a revival of classical culture (the hallmarks of a Confucian government: ritual, music, study). Enabled by his salary, Le Tac used his leisure to write A Brief History of Annan. This is where Le Tac’s historical account ends. What he leaves out is telling: the continued existence of the Tran dynasty, and the Yuan defeat at their hands. The reason for the omission is clearly to fit the expectations of his readers who would not wish to be reminded of the losses suffered in Dai Viet. Despite its omissions, the poem is still useful for understanding Vietnamese history from a northern perspective, a perspective Le Tac largely shared. Le Tac took pains to show that Dai Viet shared roots in the mythological past and in the Confucian present more readily associated with the North. Whether viewed in a positive or negative light, rebels such as Zhao Tuo and the Trung sisters held an important place in Vietnamese history and could not be omitted from the narrative.

Le Tac’s historical account, both in “Verses on Geography” and in the previous chapters of his book, relies on Sinitic sources and employs a northern point of view. These parts contain little information not readily available in older sources, and are distinctive mainly for his refusal to engage tropes of cultural difference. For that reason, historians of Vietnam often refer to A Brief History of Annan but rarely use it as a historical source. Perhaps as a consequence, the more original portions of A Brief History, particularly Le Tac’s account of his personal experience of the Mongol invasions, have also been overlooked. This may be due to Le Tac’s liminal status and the difficulty of co-opting his book for national projects. But we can uncover new information and a distinct perspective by reading parts of A Brief History such as the section on customs.

Customs of the South

In addition to “Verses on Geography,” A Brief History of Annan contains sections on geography, history, military campaigns, envoys, edicts and letters from both countries, biographies, descriptions of local products, and poetry. Le Tac had access to Chinese books and records and frequently quoted from classic Sinitic works that reference his homeland, including the standard histories, Tang poetry, as well as more recent memorials and communications from the Yuan. The most valuable aspect of his account, though, was his personal knowledge of Dai Viet. His Yuan dynasty audience prized this insider perspective: several of Le Tac’s eleven preface writers attested that his account was “trustworthy and based on evidence” thanks to his firsthand experience.Footnote 73 In his section on customs, Le Tac asserts that Annan was not a barbarian country, but rather shared many customs and cultural traits with the North.

Le Tac’s “Customs” section contains the mix of allusion, direct quotation, and personal observation that characterize his writing. In a book that is otherwise largely conventional, the customs chapter is remarkable in its assertion of cultural similarity between the North and the South. Le Tac began this section by fixing Annan in time and space, asserting that his homeland had shared in the classical culture since the mythical time of sage emperors of the third millennium BCE, predating even the legendary Xia dynasty:

Annan was called Jiaozhi in the past. During [the time of the sage emperors] Yao and Shun, and the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, the influence of the central states reached there;Footnote 74 since the Western Han it has been an inner prefecture.Footnote 75

Modern readers would first note Le Tac’s emphasis on Annan’s subordination to northern states (since the Western Han, it has been an inner prefecture). Less obvious to us but more meaningful to his contemporary audience is his assertion of Annan’s long exposure to classical culture, and therefore the worthiness of southern scholars. In the next few lines, Le Tac makes it clear that he is mainly concerned with dwellers of the coastal plain who practice agriculture and sericulture, like their neighbors in the North; he dismisses highlanders, those people less directly influenced by classical culture, as “foolish and simple.” In this passage, he starts by giving his experience with dwellers of the agricultural lowlands of the Red River Delta region:

Men till the fields and engage in trade, women raise silkworms and weave. They are polite in language and have few desires. When people from distant lands drift to their kingdom, it is their habit to ask question after question.Footnote 76 People from GiaoFootnote 77 and AiFootnote 78 are elegant and thoughtful; those from Hoan and DienFootnote 79 are refined and fond of studying; all the rest are foolish and simple.Footnote 80

Le Tac then described Vietnamese customs, curiously drawing on a five-hundred-year-old poem for support:

The people tattoo their bodies, imitating the custom of Wu and Yue. A poem by Liu ZongyuanFootnote 81 says, “We have all come to the land of the tattooed Hundred Yue.”

The poem Le Tac refers to here, Liu Zongyuan’s “On Climbing the City Wall at Lianzhou, for the Prefects of Zhang, Ding, Feng, and Lian,” was written in the early ninth century as a lament on being exiled to a post in Guangxi near the border with Annan. The description of the scenery and the tattooed people reflected Liu’s loneliness and isolation from home and civilization. Though it seems at first glance like an odd addition to an otherwise firsthand account of Annan, Le Tac included many quotes and references to classical works and poems in his book, to demonstrate his erudition and appeal to his audience of fellow literati.

Le Tac could not have known that the custom of tattooing had changed in his absence. After Le’s exile, in 1299, King Tran Thuyen refused the customary dragon tattoo that Tran men wore on their thigh. By 1323, officers of the palace guard were forbidden tattoos. According to Keith Taylor, tattoos were now seen as “old fashioned and ugly.”Footnote 82 Le Tac left Dai Viet while the state was undergoing important changes, changes he was not aware of from his new home in Hubei. Nonetheless, Le Tac’s book reinforced and fixed the common Chinese perceptions of Annan.

He continued to describe the Vietnamese:

They like to bathe in the river during the summer heat, thus they are good at swimming and handling boats. They usually do not wear hats, stand with crossed arms, and sit cross-legged on mats. When visiting important families, they kneel on their knees and bow three times. When they receive guests they serve betel. They are addicted to salty, sour and seafood flavors, they drink too much, and are very thin and weak.Footnote 83

Le Tac’s recollections of the customs of his homeland is one of the most compelling sections of the book. He reminisced about holidays in the capital, describing the king within the palace watching his children and grandchildren play ball games as the common people set off firecrackers outside the gate. He described wrestling matches, kickball, polo, and songs set to Chinese tunes with Vietnamese lyrics. The festivals (Lunar New Year, the Cold Food Festival) were the same as those in China, and some customs, such as funerals, “are the same as in the Central Country.” The section of the book is a nostalgic assertion of mutual heritage and celebration of small differences, written by an aging author who had spent most of his life in China.Footnote 84

A history for the Yuan court

Le Tac presented A Brief History of Annan at the Yuan court during the Tianli reign period (1328–1330), requesting that it be included in the compendium of government institutions and foreign relations, the Jingshi Dadian. It was.Footnote 85 Judging by the eleven appreciative prefaces to A Brief History, Le Tac’s contemporaries greatly enjoyed his work. One went so far as to say, “The gentry and retired officials pass it around and read it out loud.”Footnote 86

Le Tac’s book, and indeed his life, represents the complicated relationship of the northern and southern countries, inheritors of a shared classical tradition and yet frequent enemies. Le Tac adopted a northern perspective in his book, praising the Yuan state, vilifying Vietnamese resistance to northern interference, and downplaying Dai Viet’s independence. He often referred to Dai Viet in a slippery way, implying that it was a part of the northern empire, or at least not asserting otherwise. But the political situation of his time was even more complex than this allows. Within Dai Viet, there was conflict among the Tran royal family over succession, as well as regional tensions. Le Tac was a regionalist too, clearly favoring his home district in the Red River Delta to upland regions. China itself was under foreign, Mongol rule. Le Tac’s Chinese peers, notably the Song exile Mi Kai who found shelter with him, were, like him, dealing with the shifting tides of power and a crisis of loyalty. Le Tac lived in a world with more complex demands on his loyalties than simply patriotism to homeland. He served a Tran prince who was at odds with the Tran emperor. His regionalism meant that he may have felt that he had more in common with the Song leftover subject Mi Kai than with, for example, his “foolish and simple” compatriots from beyond the heartland districts of Dai Viet.

There is no doubt that Le Tac was constrained to write from a northern perspective. Some historians have combed through the book to find evidence of Le Tac’s patriotism or nationalist inclinations. Wu Xiangqing, the editor of a 2000 Chinese edition of A Brief History, singled out Le Tac’s inclusion of a letter from a southern king admonishing Han Wudi for attacking Nan Yue, and pointed to Le Tac’s forthright assessment that the Song dynasty invasion of Dai Viet caused harm and suffering as proof of his patriotism.Footnote 87 Such claims are difficult to prove. What seems most significant is that Le Tac was asserting the cultural equality of the South with China, and insisting on its long exposure to classical culture to his northern audience.

Le Tac’s book, finished in the 1330s, forms an instructive contrast with two other Vietnamese histories from the same era, Linh Nam chich quai (1380s)Footnote 88 and Le Van Huu’s Dai Viet su ky (1272). The Linh Nam chich quai (“Strange Tales from South of the Passes”) falls within the genre of tales of the strange, and deals mainly with legends, myths, and miracles. It differs from A Brief History in dating the beginnings of the Viet state back to the legendary Hung kings. Since these kings began their rule in the third millennium BCE, their existence would make the southern lineage predate the Zhou dynasty of the North. The final anecdote, “The Tale of the White Pheasant,” elaborates the well-known story of an embassy from Yuechang that traveled to the Zhou dynasty to present tribute of a white pheasant. According to the version recorded in the Linh Nam chich quai, the Duke of Zhou said to the envoys, “Why do you people from Jiaozhi have short hair, tattoo your bodies, and go bareheaded and barefooted?” These were all common stereotypes of Vietnamese people, often repeated in Chinese writings, but not taken up by Le Tac. In contrast, the author of Linh Nam chich quai takes them head on, expressing cultural pride through the mouths of his envoys to the Zhou court: “Short hair is for convenience when traveling through the mountains and forests. We tattoo our bodies to look like dragons, so when we travel through the water the flood dragon will not dare to attack us. We go barefoot for convenience when climbing trees. We engage in slash and burn agriculture [and leave our heads bare] to beat the heat. We chew betel to get rid of filth, and therefore our teeth become black.” As in other versions of the story, the envoys get lost on the way home, so the Zhou dynasty grants them south-pointing carriages to guide the way.Footnote 89

Le Van Huu’s Dai Viet su ky (“Annals of Dai Viet”) was modeled on Sima Qian’s Shiji. Le Van Huu finished this work and presented it to the Tran throne in 1272,Footnote 90 and Le Tac mentioned it in his own work. O. W. Wolters and Keith Taylor understand Le Van Huu’s work as a response to Mongol pressures. Compared with Le Tac, Le Van Huu was much more clearly concerned with elevating the Vietnamese polity to the same level as China.Footnote 91 Evoking the Nan Yue kingdom’s resistance to the northern Han dynasty, Le Van Huu cast the first post-Tang Vietnamese emperor Dinh Bo Linh (924–979 CE), the Le, the Ly, and the Tran as inheritors of Zhao Tuo’s mandate. One of the best examples of this effort to construct a Vietnamese identity is a poem by the general Ly Thuong Kiet, written on the occasion of fighting Song invaders in 1076, either cited or fabricated by Le Van Huu. This poem, according to Taylor, “expresses the idea of northern and southern imperial realms with a clear border defined by separate heavenly mandates.”Footnote 92 The poem is worth citing in full:

This poem has served as a powerful tool for constructing a national past. Whether or not Ly Thuong Kiet truly uttered these words, the message is so clear and resonant that it is still often cited as a prime example of Vietnamese national consciousness and resistance to foreign aggression, and applied to times and circumstances as different as the American War in Vietnam (1955–1975) and the current tensions over the Spratly Islands.Footnote 94

Le Van Huu and Le Tac both drew on classical sources including the Book of Documents, Records of the Historian, and History of the Han for their work. But from that commonality, the books diverged. Those Tran subjects who remained in Dai Viet through the Mongol incursions and, against all odds, prevailed, were galvanized against foreign threats. In contrast, Le Tac made no such overt statement of Vietnamese independence or claim to a separate heavenly mandate.

Le Van Huu’s Dai Viet su ky was absorbed into the Dai Viet su ky toan thu (“Complete Chronicles of Dai Viet”) by imperial request in 1479. Court historians continued to supplement this work through the seventeenth century.Footnote 95 The Complete Chronicles was not well known in China. In contrast, Le Tac’s Brief History of Annan was available to Chinese readers during the Ming era, but likely unknown in Dai Viet. Qing dynasty (1644–1911) scholars rediscovered A Brief History and compiled extant manuscripts into an authoritative edition containing nineteen of the original twenty chapters (a final chapter of poems was lost). Scholars were still eager to consult A Brief History of Annan more than five hundred years after it first appeared; it was rushed to the press in 1885 when the Sino-French War caused a surge of interest in Vietnam. A French edition soon followed, translated by Camille Sainson as Mémoires sur l’Annan and published in Beijing in 1896.Footnote 96 French and Chinese scholarly interest in the text was no doubt bolstered by their colonial enterprise in Vietnam.

Just as Le Van Huu’s Dai Viet su ky forms a useful counterpoint to Le Tac’s work, a Tran ambassador named Mac Dinh Chi (c. 1280–1350) illuminates the path not taken by Le Tac. Mac Dinh Chi is mostly remembered today as the sixth-generation ancestor of the dynastic founder Mac Dang Dung (c. 1483–1541). He had an illustrious career serving the Tran dynasty, beginning with his first-place performance in the 1304 examinations held under the Tran. In 1308, Mac Dinh Chi traveled to Beijing as an envoy. Le Tac was living in Hubei at the time, but there is no indication that he would have met with or even known about Tran envoys. Mac Dinh Chi’s visit is not recorded in Chinese sources, but the Complete Chronicles of Dai Viet contains an unusually long passage describing his trip:

The [Tran] emperor sent Mac Dinh Chi to the Yuan. Dinh Chi was short and thin and the Yuan people disdained him. One day the steward summoned him for an audience and he was seated with the others. At that time it was the fifth month, and the courtyard had just a thin canopy. There was an embroidered image of a sparrow in the branches of a bamboo. Dinh Chi pretended that he thought it was real and rushed forward as if to catch it. The Yuan people all burst out laughing. Then Dinh Chi grabbed the canopy and rent it in two. Everyone was amazed and asked him why he did that. He answered, “I have heard that in ancient times there were paintings of sparrows in plum trees, but I have yet to hear of a painting of a sparrow in bamboo. Now inside the prime minister’s tent there is an embroidered sparrow in bamboo. Bamboo represents the gentleman and the sparrow represents the petty person, and yet in this embroidered canopy the sparrow exceeds the bamboo. I am afraid the petty person’s way will be strengthened and the gentleman’s way will disappear. Therefore I have eliminated [the embroidery] for the imperial dynasty.” Everyone admired his ability.

After this episode, Mac Dinh Chi had an audience with the Yuan emperor. The emperor asked him to inscribe a fan he had just received from another foreign ambassador. Dinh Chi picked up his writing brush and composed a poem without hesitation. His poem reflected on the moral charge of government officials by means of several classical allusions. According to the Complete Chronicles of Dai Viet, it caused all the Yuan people to gasp in admiration.Footnote 97 Mac Dinh Chi was lauded for his success upon his return to Dai Viet and given the nickname “Valedictorian of Two Countries” (luong Quoc trang Nguyen). His triumph was well known as late as the nineteenth century.Footnote 98

The anecdote shows an initially despised southern intellectual demonstrating that his erudition and moral sensibility exceeded that of his northern interlocutors. Mac Dinh Chi inverted a hierarchy of knowledge (Beijing as a cultural center and Dong Kinh as an outpost) by demonstrating that the Yuan court had lost their sense of propriety. The southern valedictorian, by contrast, preserved his sense of right and instructed his grateful northern interlocutors. The story ends happily, with the Yuan people readily acknowledging his abilities. Like Le Tac, Mac Dinh Chi’s goal (or the goal of the author of the Complete Chronicles) was not to show that Vietnamese culture was different though equal to that of China’s, but rather that Dai Viet was as much an inheritor and preserver of classical learning as China was. In fact, in this case, Mac Dinh Chi had to instruct the Yuan people, who had lost touch with that past and its moral foundation. This is perhaps a commentary on the degrading influence of Mongol rule. Le Tac and Mac Dinh Chi thus both desired to demonstrate Vietnamese mastery of classical culture, but took different life paths: Le Tac as a minister of the Yuan, and Mac Dinh Chi as a minister of the Tran.

The afterlife of A Brief History of Annan

Once French colonial rule of Vietnam came to an end, Vietnamese nationalists finally turned to Le Tac’s Brief History for their own purposes. The Republic of Vietnam (RVN) sponsored the Committee for the Translation of Vietnamese Historical Documents to work on translation projects. Based at Hue University, these translation projects were meant to bring Vietnamese precolonial texts, all of which were written in literary Sinitic or the character-based demotic script Nom, to a readership literate only in the modern quoc ngu (“national language”) script of romanized Vietnamese. According to the historian of Vietnam Nu-Anh Tran, the RVN sponsored historical research, performances of court rituals, and revival of traditional art forms in order to establish itself as “the inheritor of state power and cultural authenticity.”Footnote 99 The committee chose A Brief History of Annan as its second translation, in 1961, illustrating its importance to the RVN historical narrative. At the same time, Le Tac confused modern readers because he failed to imagine himself into the community that twentieth-century nationalist meta-narratives would lead one to expect. Scholars dismissed the text through the 1930s, dismissing the author and book as “a historian who sold out the country, a work of history that is a humiliation.”Footnote 100 Even the editors of the 1961 edition, no doubt sensitive to the RVN’s then-fraught situation, labeled him a traitor.Footnote 101

Is A Brief History of Annan a Vietnamese book, properly designated An Nam chi luoc in the romanized Vietnamese quoc ngu script? Should it be considered as such because it was written by a Dai Viet-born author, even though it was largely unknown in Vietnam before the twentieth century? Or should it be considered a Chinese work, romanized in Mandarin pinyin as Annan zhilue, acknowledging that it was primarily written for, and read by, a Chinese audience? Is Le Tac a traitor for surrendering to the Yuan and fleeing his country? Or is he a patriot who contributed to the history of Vietnam and recorded the stories of southern resisters to northern aggression for posterity?

The answer to these questions lies somewhere in between. Le Tac’s book reflects the dual nature of Vietnamese history, its long and fruitful connection to classical culture, its educational system based on literacy in literary Sinitic and knowledge of the classics, paired with its centuries of hard-fought political independence. Le Tac, and others like him, had a complicated set of personal and literary allegiances that shifted over his lifetime. A Brief History of Annan has been adopted and put to work by a number of different stakeholders, from the Mongols to the RVN, but the circumstances of its creation are more complex than that which a restrictive binary of an opportunistically imperialist China or a patriotically rebellious Vietnam allows.

In the end, Le Tac had nothing left but to commit his memories and knowledge to print. He clearly wished his book to be read, preserved, and disseminated. Retired, no longer able to return home, Le Tac pored over books ranging from the classic Book of Documents, through Tang poetry, to recent Yuan edicts to compile his Brief History. As his friend Liu Bide reported, he “stays inside but his mind ranges all over the place.”Footnote 102 His family and the country that he knew were lost, but he could still seek solace and claim his place in the familiar world of classical culture, the world he proudly shared with his father, grandfather, and ancestors, stretching all the way back to Prefect Nguyen Phu of the Eastern Jin.