I have established the republic. But today it is not clear whether the form of government is a republic, a dictatorship or personal rule.

Funeral of General Omar Torrijos

The huge funeral procession for Omar Torrijos, with perhaps a quarter of a million mourners, wound its way down Avenue of the Martyrs (formerly Fourth of July Avenue), along a border that previously separated Panama City from the Canal Zone. Days earlier, on July 31, 1981, Torrijos had perished when his light plane crashed into a mountainside jungle during a storm. The cortege route traced a line of repeated confrontations between Panama and the United States over the former’s rights. It recalled an earlier definition of the Panama Canal as “a body of water entirely surrounded by controversy.”Footnote 1

* * * *

Torrijos’s death left a mixed legacy. On one hand, he had ruled the country as dictator for thirteen years, having overthrown duly elected President Arnulfo Arias in 1968. Many elite families had lost influence during the dictatorship, as the general appealed to poor and rural people to support his regime. Elections were held only for the Assembly of County Representatives, a weak body the regime easily manipulated.Footnote 2 On the other hand, Torrijos had persevered in his quest to replace the hated 1903 treaty with the United States that gave the colossus the right to build, operate, and defend the Panama Canal, with little participation by Panama. He was credited with concluding negotiations for the 1977 Carter-Torrijos Treaties that eventually gave Panama the Canal free of encumbrances in 1999. And, in 1978, he began a transition to restore democracy under a civilian president. Politicians and military officers saw his death cast these plans into disarray. For all these reasons, the mourners felt genuine grief and loss the day of his burial.Footnote 3

Credible evidence pointed to pilot error as the cause of Torrijos’s plane crash, yet numerous conspiracy theories circulated for years. Torrijos’s death left a void at the top of Panama’s government and provoked a scramble for power.

Premature Transition to Democracy

Attempting to sway US senators reluctant to approve the Panama Canal Treaties in 1978, President Jimmy Carter and other heads of state suggested to General Torrijos that the chances of success would be better if Panama proceeded toward democratic government, and Torrijos agreed. He acted partly because his coalition had failed to form a strong administration, and likely due to fatigue as well.Footnote 4 He announced that the country would begin a return to democracy, starting with lifting restrictions on political activity and finding a civilian president. His subservient Assembly duly passed Law 81 to allow the return of political exiles, end censorship, and authorize the formation of parties dormant during most of the decade.Footnote 5

To guide administration officials and supporters, he had his staff create a new party, the Partido Revolucionario Democrático (PRD), inspired loosely on Mexico’s Partido Revolucionario Institucional. Torrijos clearly dominated the PRD, whose program would consist of “torrijismo,” or the policies and actions he had instituted in preceding years.

Prominent among the returned exiles stood Arnulfo Arias, former president from the 1940s and victim of the 1968 coup, still a formidable vote-getter at the head of his Panameñista Party.Footnote 6 Meanwhile businessman Roberto “Bobby” Eisenmann founded the independent newspaper La Prensa to publish critical information about these unfolding events.Footnote 7

La Estrella, in continuous print since its founding in 1853, began as a Spanish version of an English-language paper sold to foreigners crossing during the California Gold Rush. Generally mainstream ideologically, it has changed ownership many times in its long history.

El Panamá América, founded in 1928, was associated with the political interests of the Harmodio Arias family. Shortly after the 1968 coup, the military seized full control of Editora Panamá América (EPASA) and all its newspapers, including Crítica, the all-time bestselling local tabloid founded in 1958. After the return of civilian government, EPASA reverted to the Arias family and sought to compete with La Prensa. In 2010, EPASA was sold to a consortium whose major shareholder is said to be Ricardo Martinelli.*

La Prensa was founded in 1980 by businessman Roberto Eisenmann to oppose military government. It was shut down by the military from 1986 to 1990. When reopened, with technical support from Winston Robles, it pioneered a modern printing plant, a digital edition, and more in-depth, original reporting often critical of incumbent governments and elected officials.

El Siglo, founded in 1985 by businessman Jaime Padilla Véliz, was acquired by business tycoon Abdul Waked in 2001, with strong editorial management by Ebrahim Asvat until 2011. The paper sought to add political content to a tabloid format, and its generally independent stance has intermittently made it a circulation leader. Waked, also the major shareholder of La Estrella since 2006, apparently released control of both in 2017.

Radio ownership and broadcasting has varied from highly partisan to non-political and has been the most diverse and locally focused medium in Panama. The Eleta brothers extended their radio empire to start television broadcasting in 1960, when RPC Channel 4 went on the air. Medcom and its increasing number of affiliates remained nominally independent. The Roberto F. Chiari family started TVN Channel 2 in 1962; during the dictatorship it was acquired by a group close to the military, headed by Carlos Duque. In 1990, it was sold to another group, and today the Motta family remains the major shareholder of this more independent network. Both broadcasters have offered original national programming since the 1990s. After the advent of cable television in the new century, viewers were offered many more viewing options.

* In 2012, then-President of Panama Ricardo Martinelli also acquired a large percentage of shares of the RCM Nextv television channel, in apparent violation of Law 24 of 1999, which prohibits radio and television concessionaires from controlling a daily newspaper. See Aminta Bustamante, “Martinelli, los medios y el poder,” in La Prensa, May 8, 2013.

These and other measures, later called a “democratic transition” in the rest of the continent, promised that the implementation of the new treaty would be accompanied by a freer political climate. In evocative language, Torrijos spoke of the military “returning to the barracks.” The process would culminate in the direct election of a new president in May 1984.Footnote 8 Freedom of the press would be crucial for the transition to succeed.

Torrijos also told his close associate and minister of planning, Nicolás Ardito Barletta, that he intended to retire all current members of the Guardia high command and replace them with younger men loyal to himself. He did not wish to have some ambitious senior officers overthrow a civilian leader the way he himself had done in 1968. Clearly, Torrijos intended to lead a return to democracy yet sensed an inclination on the part of the military to retain autocratic rule.Footnote 9

Torrijos chose to be president the talented, handsome, 38-year-old law professor and current minister of education Aristides Royo (1978–82). Born in the suburbs and educated at the hyper-political National Institute, Royo had gone to Salamanca to earn his law degree. Upon his return, he taught law at the University of Panama, joined the prestigious Morgan & Morgan law firm, and then plunged into the political turmoil of 1968. He helped write the Torrijos “revolutionary” constitution of 1972 and participated in treaty negotiations in the mid 1970s. He became minister of education in 1973 and helped create a more positive, reformist image for the regime.

Torrijos, who had come to rely on Royo’s judgment and political skills, nominated him for election by the Assembly of Representatives of Municipalities to a six-year presidential term to oversee the democratic transition. Businessman Ricardo de la Espriella became his vice president, in equally automatic fashion. Royo soon created an economic advisory council made up of prominent businessmen Torrijos had cultivated during the 1970s, called the Frente Empresarial del PRD. Torrijos had cleverly won over economic leaders by offering government subsidies, protection, and concessions, following the broader vision enunciated by Ardito Barletta. Now, Royo garnered their support as well, managing to set up Panama’s first Chamber of Commerce in 1979.Footnote 10 Finally, he led the festivities at a massive celebration of the Panamanian takeover of the former Panama Canal Zone, held on October 1, 1979, which included the participation of Mexican President José López Portillo and US Vice President Walter Mondale.

When President Jimmy Carter sought a refuge for the deposed Shah of Iran, Torrijos quickly agreed, but he left it up to President Royo to quell the controversy, until the Shah abandoned his hideaway on Contadora Island for a more tranquil residence in Egypt.Footnote 11

Demilitarization of government lay at the core of the transition in Panama, and Royo gave it a civilian face. He implemented Law 81 that lifted rigid controls on speech and politics and set a timetable for return to full democracy in 1984. Pent-up demands and challenges arose, and vocal discontent that had built up to some of Torrijos’s programs suddenly erupted. On October 9, 1979, the National Opposition Front organized what it claimed was the largest political demonstration in Panamanian history, attended by about 300,000 people. This was complemented by a sixty-eight-day, nearly nationwide teachers’ strike in the fall of 1979. If transition occurred, many objected to its being led by military-installed newcomers.Footnote 12

In 1980 the PRD civilianization process seemed a little more secure, and Torrijos routinely told favor-seekers to go see the president, that he was now retired. The PRD, meanwhile, gathered enough signatures to qualify as a legal party.Footnote 13 Slightly relaxed electoral procedures in September 1980, the first open elections since 1968, chose nineteen members of a legislative council within the Assembly. Had the Panamanian transition succeeded, it would have been a first among the many Latin American military regimes to return to democracy during the 1980s.Footnote 14 But it was not to be.

As Panama began the new decade, Royo ran into still stronger crosswinds, fanned by the world recession and ambitions among National Guard colonels to extend the dictatorship. Panama’s economy skidded into stagnation that felt more painful because of the high expectations people had for prosperity under the new treaties. A November 1981 article in The New York Times claimed that Royo seemed to be prevailing in a struggle for power with the new National Guard Commander, Colonel Florencio Flores Aguilar, but warned that economic conditions were deteriorating badly for the masses:

the economy seems to be booming with new luxury apartments and office blocks rising. Over the last decade, Panama has also been a leading “offshore” financial center for Latin America, its 114 foreign banks, including many from the United States, controlling $38 billion in deposits. But such service functions produce little real economic growth. Unemployment, already high, has gone higher and frustrations, barely held in check by Torrijos, threaten to erupt.Footnote 15

Without the gravitas of Torrijos and with the economy on the skids, Royo faced formidable obstacles to returning to an open political system. In some ways, his presidency was also doomed by the death of Torrijos, after which the colonels in the Guard began maneuvering to hold on to power. Royo, who never accepted the primacy of the military, stood in their way. Suddenly, at the end of July 1982, Royo announced his resignation, allegedly for reasons of health. In fact, Guard officers had decided to roll back civilianization with their own transition – to re-militarization. They were not going quietly back to the barracks.

On the first anniversary of Torrijos’s death, veteran journalist Alan Riding described the behavior of yet another new commander, Rubén Darío Paredes, at the swearing in of de la Espriella as President. Paredes seemed to be “trying to look constitutional but behaving as though he had just carried out a coup,” when he suspended the publication of all newspapers for seven days and demanded the resignation of all the officials of the outgoing government.Footnote 16

Royo’s nearly four years in office stood in sharp contrast to the following period, dominated by military chiefs, especially Manuel Antonio Noriega. Civilian presidents de la Espriella and his successor Jorge Illueca openly acknowledged that their authority flowed from the Comandancia (headquarters) and served for short tenures. Others, like Nicolás Ardito Barletta and Eric Arturo Delvalle, who attempted to defy Noriega, ended up about as quickly and surely deposed.Footnote 17

Resurgence of the Guard

On the military side, several ranking officers who had resisted Torrijos’s democratization plans, to protect their positions, began jockeying to take power after his death. The Guard had long provided muscle for the regime, and its leaders had become accustomed to the power, money, and stature they enjoyed. The Guard also played important roles in suppressing opposition activities, raising money for illicit purposes, and managing intelligence gathering at home and abroad.Footnote 18

In 1981, ranking Guard officers included Col. Florencio Flores (Commander), Col. Rubén Paredes, Lt. Col. Manuel Antonio Noriega, and Col. Roberto Díaz Herrera, most of whom had experience in a variety of activities besides police work and national defense. In mid 1982, fellow officers dismissed Flores as commandant and replaced him with the more politically ambitious Paredes. The new leader had no intention of allowing civilians to exercise real power and planned to run for president himself in 1984. Still, he pushed an electoral reform package through the legislature. To assuage the ambitions of other Guard officers, he signed a secret agreement allowing them to rotate into the presidency after his term ended.Footnote 19

Paredes also appointed a commission to transform the Assembly of Representatives of Municipalities (corregimientos) into the Legislative Assembly, one similar to the body that had existed for most of the twentieth century. It would enjoy more autonomy vis-à-vis the executive branch and participate in a broader range of law-making activities. It also inherited the patronage distribution role of its predecessor, allowing its members to win reelection, enrich themselves, and enjoy immunity from prosecution for wrongdoing. Carlos Guevara Mann, a historian who has studied corruption for decades, argues that the 1983 reforms, rather than encourage democratic government, actually extended a long tradition of careerism, corruption, and impunity in that body. The reform was approved in a referendum and took effect the following year.Footnote 20

Meanwhile Noriega, head of the Guard’s intelligence branch (called G-2 after US military usage), became second in command under Paredes. When Paredes had to resign in August 1983 to run for president the following year, Noriega assumed command of the Guard and promoted himself to general. He had encouraged Paredes to step down and run but soon double-crossed him; instead he sought a civilian to head the military-backed PRD ticket.Footnote 21 First, he offered the candidacy to Fernando Manfredo, a longtime Torrijos friend and collaborator who at the time served as deputy administrator of the Panama Canal Commission (PCC). Manfredo declined, so Noriega’s representative invited Nicolás Ardito Barletta to run.Footnote 22 He had served in numerous capacities with Torrijos during the 1970s, ending up as minister of planning and economic policy (MIPPE) from 1973 to 1978. From there he went on to be vice president for Latin America in the World Bank.

When Ardito Barletta asked Noriega if the Guard would defer to his presidential authority, in the event he was elected, Noriega assured him it would. Later events proved that Noriega really intended to maintain authority behind the scenes. He needed Ardito Barletta to give legitimacy to the regime and to solve the country’s economic problems. Despite the appearance of a return to democracy, then, some suspected that the balance of power still resided in the Guard headquarters in Chorillo, rather than the Las Garzas presidential palace, in the Casco Viejo district.Footnote 23

Noriega carried out an even more audacious power grab shortly after becoming commander. With support from the joint committee for defense of the Canal, he pressured the legislature to pass Law 20 to reorganize, strengthen, and convert the Guard (created in 1953 by previous strongman José Antonio Remón) into the Panama Defense Forces (PDF). The Assembly dutifully complied. The new unit was a rapid response force along the lines of the Israeli Defense Force – well-armed, superbly informed, highly trained, and capable of lightning action to thwart potential threats. It also took over other police functions and enjoyed enhanced autonomy from civilian oversight. US authorities went along, since, until 1999, the US military’s Southern Command (Southcom), with headquarters in the Canal Area, would backstop the force, and, in the long run, the Treaty for Permanent Neutrality would help to shield the Canal from threats.Footnote 24

At the time, Noriega enjoyed good relations with the national defense establishment in Washington, which included the Pentagon, CIA, DEA, NSC, and other agencies. He had worked with Vice President George H. W. Bush, who “handled” him when he was CIA director. These agencies approved of the beefed-up force, on the grounds that, under the new treaties, Panama would have to shoulder increasing responsibility for defending the Canal. The move also benefitted the escalating US war against the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, where Noriega later served the Iran-Contra operation in multiple ways.Footnote 25 The reinforced PDF also fit nicely with the national security doctrines adopted by the US-backed military regimes in the Southern Cone, which stressed fighting domestic communism over external threats. Finally, Law 20 created a buffer between the Panamanian executive branch and the armed services and gave the PDF broad authority to intervene in many aspects of national life.Footnote 26

US support for Panama in 1984–85 was authorized at the highest levels. The 1983–84 Kissinger Commission on Central America recommended major increases in economic and military aid to the region, to block the spread of communism from Cuba there. It spoke of an extra $800 million in the 1984 fiscal year as a down payment on a long-term commitment of $24 billion in economic assistance by 1990.Footnote 27 Although Panama received little specific attention in the report, it was clear the State Department intended to help Ardito Barletta’s government succeed in returning the country to democracy and adopting austerity measures following the profligate Torrijos years. And the DOD foresaw an accelerated hand-off of Canal protection to the PDF. Economic aid mushroomed from an average $9 million between 1980 and 1984 to $74 million in 1985, and military aid from $15 million to $93 million in the same years. The following year, Congress left Panama out of the AID budget due to the Noriega crisis, but by then the damage had been done. The lopsided emphasis on defense gave credence to the later observation that Noriega was a strongman, nurtured by the United States, who could only be toppled by his creator.Footnote 28

1984 Presidential Election and Ardito Barletta Administration

The 1984 election could have been a turning point in Panama’s destiny, but it was not to be. Ricardo de la Espriella had succeeded to the presidency when the Guard jettisoned Royo in 1982. Later, when Manfredo turned down the PRD presidential nomination, de la Espriella offered it to Ardito Barletta, who, in late 1983, accepted to run based on Noriega’s commitment to obey his administration. Ardito Barletta’s close collaboration with Torrijos, plus his experience in international finance, made him an excellent choice to address the country’s economic malaise. His approval by the PRD sealed his nomination.Footnote 29 He lined up backing from David Samudio, the unsuccessful candidate against Arnulfo Arias in 1968, as well as from parties like PALA, the Liberals, and the Republicanos. Haltingly, the country’s parties began to evolve from personalistic vehicles toward broader organizations representing diverse elements and interests.

Ardito Barletta’s decision to run for president ended the pleasant job he held at the World Bank, but it reflected his earlier work with Torrijos and promised professional rewards. In 1968–70, as director of planning under Torrijos, he had overseen the creation of an ambitious plan for national development, Estrategia para el desarrollo nacional, which had guided the Torrijos administration.Footnote 30 Later, as minister of planning and economic policy, he had the opportunity to put many of his ideas to work. Ardito Barletta now hoped that as president he could resurrect that plan while also solving short-term difficulties.

Ardito Barletta had never run a political campaign before, but he returned home in January 1984 and threw himself into the race with gusto and considerable backing from the government. The coalition he assembled, called the Unión Democrática Nacional, augmented his core PRD support. His platform called for democracy, strong and honest government, economic and national development, and foreign policies favorable to Panama. President Carter’s former chief of staff, Hamilton Jordan, provided strategic advice for his campaign.Footnote 31 Ardito Barletta focused on winning votes from civil servants and teachers, from whom he expected warm support, and played to large crowds in all regions of the country, including indigenous and ethnic communities. In his wife’s province of Los Santos, he wore guayaberas and posed as a man with rural roots. His final rally in the capital mobilized 180,000 supporters, whom he addressed with confidence and vigor.

Ardito Barletta’s program drew on the planning he had done since the late 1960s and emphasized utilization of the Canal properties and assets becoming available under the 1977 treaty. It contained fulsome promises to working and middle-class citizens. He also addressed the need for governability, that is, stronger public institutions and enhanced government effectiveness. As for eventual ownership of the Canal, he spoke of Panama finally benefitting fully from its superb geographical location and expanding beyond the simple business of ship transits.Footnote 32

Arnulfo Arias, showing his 82 years, threw his hat in the ring as well. Ardito Barletta had met with him the preceding November to argue that he desist from running and choose his own designee as Ardito Barletta’s vice president. Arnulfo declined and instead ran a low-key, traditional campaign as the “patriarch of democracy.” He declined invitations to debate Ardito Barletta, trying to appear above the fray. Meanwhile, President de la Espriella, hoping to undermine Ardito Barletta and end up extending his own tenure, consulted with Arias, the military’s archenemy. After failing to convince Arias, de la Espriella was himself deposed for disloyalty. Second vice president Jorge Illueca assumed the presidency in January 1984, three months before the election.

The outcome of the 1984 contest remains controversial, due in part to Arnulfo’s vociferous complaints of fraud and reporting by foreign reporters. Ardito Barletta’s campaign no doubt received abundant government support, and open favoritism toward him by the US government raised suspicions of meddling. Finally, the fact that Noriega’s PDF stood firmly behind Ardito Barletta convinced most that it had rigged the election. After the electoral tribunal annulled some 23,000 of his votes (along with 19,000 of Arnulfo’s), Ardito Barletta emerged as the winner, with a margin of less than two thousand votes.Footnote 33 He was inaugurated on October 11, 1984, along with a PRD majority in the legislature. Former president Jimmy Carter and US Secretary of State George Schultz flew to Panama to congratulate him, and numerous Latin American heads of state attended. Potential investors began visiting too.

The revamped Legislative Assembly, elected in 1984 and expected to work with the new president, contained a mixed bag of former members and newcomers, totaling sixty-seven. The PRD and its allies won a quarter of the overall votes and just over half the seats. The Panameñistas won a fifth of the votes and a fifth of the seats. Several smaller parties divided up the remaining twenty seats. The PRD majority suggested a continuation of subservient relations with the executive branch, much stronger than the Assembly.Footnote 34 Subservience did not mean honesty and transparency, however, because corruption continued unabated. Guevara Mann concluded:

By encouraging bribery, embezzlement, and related corrupt activities, exempting certain individuals from justice (impunity); and manipulating voters through the particularistic assignment of public goods (clientelism), all three traits contradict the notions of political equality and universalism that are central to the idea of democracy.Footnote 35

Clearly, under these circumstances, the Assembly accomplished little of the people’s business.

Corruption looms large in Panama’s politics, if not always explicitly. Guevara Mann specified three of the dimensions (economic, impunity/prosecution, and political culture) that surface most commonly. A fourth is its institutional impact, as we will observe. Systematic analysis of corruption such as Guevara Mann developed for the Assembly lies beyond the scope of this study. Instead, we will cover episodes as they arise and register contemporaries’ judgments about them.

Ardito Barletta first toured friendly nations to show off Panama’s newly restored democracy, while at home he enjoyed high approval ratings and support from the two major TV stations. He appointed more technocrats than politicians to his cabinet, intending to run an effective administration. The economy proved most challenging, so he invited prominent US planner Marc Lindenberg to consult with his team. They built on earlier visions of Panama as a hub for global services and trade, comparing it to Singapore, which had enjoyed success as a small nation using its position for strategic advantage. They propagated the concept of Panama as a “Centerport,” a place for container marshalling, bonded manufacturing like in the Colon Free Zone, air transport, maritime services, and offshore banking. The president invited Asian investors to support these developments.Footnote 36

In a short time Ardito Barletta posted impressive accomplishments. He overhauled the national budget agency, the Contraloría, and its watchdog twin, the Tribunal de Cuentas, and he won Assembly approval for a new judicial code. He inaugurated the Parque Metropolitano, which incorporated a large part of the forested lands transferred from the former Canal Zone. He had several investment incentives approved. He arranged for the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), long housed in the Zone, to become a US-Panamanian entity, and he designated new coastal lands for it to expand its marine research facilities.Footnote 37 He empaneled the Tripartite Canal Alternatives Study group, by which Panamanian, Japanese, and US specialists weighed the possibilities of a sea-level Canal, a land bridge, or expansion of the existing facility. Other initiatives also won approval by the legislature.Footnote 38

Ardito Barletta focused most of his presidential powers, however, on achieving economic development. His goal of unleashing the productive energy of the nation faced severe shortages of financing and investment, due to the general depression that overlay the region. The first order of business, then, had to be raising capital from the international banks, which he was fully acquainted with from his World Bank days. To accomplish this, he had to carry out austerity measures to encourage domestic growth and also to qualify for new international credits. The public debt, run up during the preceding fifteen years, stood at an unhealthy 85 percent of the GNP, and spending still ran 7 percent over revenues. His remedy was to trim government payrolls, cut subsidies for public services, assess new taxes, promulgate a less protective labor code, and support industry so it could expand the economy. The opposition, meanwhile, denounced these measures as harmful to the poor and working class, but Ardito Barletta remained steadfast; Noriega and most union leaders, aligned with the PRD, agreed with him.

At first, Noriega seemed to embrace the bitter medicine prescribed by the president. His chief of staff, Col. Díaz Herrera, did not like it, however, calling it imperialist punishment.Footnote 39 The reforms, in fact, had the effect of laying off government employees and increasing taxes. Opponents focused their ire on proposed Law 46, submitted to the legislature in November 1984. In hindsight, the president admitted that he may have failed to promote enough public discussion and gather cosponsors to win support. Within a month, huge demonstrations organized by the opposition erupted in the capital, and Ardito Barletta had to retreat on raising taxes.Footnote 40

The following February, Ardito Barletta submitted to the Assembly a milder version of the law, to assuage critics and regain the initiative. This time it passed, and he complemented its rollout with well-targeted pork-barrel projects. Yet by spring 1985, military commanders, especially Díaz Herrera, began to doubt Ardito Barletta’s ability to lead the country, and some spoke of “shared governance,” i.e. more PDF participation in decision-making. They imposed some cabinet changes in May to enforce their opinions and perhaps pave the way for a military coup. Some US observers also viewed the president as ineffectual. Meanwhile, Ardito Barletta paid a friendly visit to Mexican President Miguel de la Madrid, himself a veteran of economic hard times, and hired a new political consultant to help explain his reforms to the public.

In mid 1985 Ardito Barletta readied his proposal for a World Bank credit to refinance the foreign debt, based on the structural changes he had instituted, such as competitiveness, financial probity, and opening the economy to trade and investment. He shared the draft letter with businessmen, politicians, and labor leaders in hopes of gaining support. Sensing the fragility of the moment, the State Department requested that General John Vessey, Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, pay a visit to the president and to General Noriega to urge them to continue on the democratic path.Footnote 41

In late August, the president invited Noriega and other commanders to meet and discuss the World Bank proposal, which Díaz Herrera opposed. As a result, Ardito Barletta agreed to phase in the reforms to dampen their negative impact. They would be implemented over seven months: agricultural to revive farming; labor to raise worker productivity; industrial for factory expansion. Schools would be on vacation during those months, cushioning the potential for public protest. The president informed the legislature that his policies had already produced GDP growth of 5 percent and reduced the fiscal deficit. His assurances would prove to be insufficient.

Within days of launching his economic plan, the president learned of a brutal murder that shocked the nation. On September 13, the charismatic physician Hugo Spadafora, member of a prominent family, had been decapitated and dumped just across the Costa Rican border. Having fought in the civil wars in Central America, Spadafora enjoyed widespread public adulation. He had recently denounced Noriega for various crimes, including drug trafficking, and he announced his intention to enter politics in Panama. Critics of the government immediately attributed his horrific murder to PDF agents, and Noriega, although out of the country when it occurred, seemed likely to be behind the act.Footnote 42 Public outrage over the Spadafora murder engulfed the nation, and Ardito Barletta promised the family he would appoint a commission to determine responsibility for the crime, which he did.

Vice President Delvalle used the Spadafora crisis to urge Díaz Herrera to push Ardito Barletta out, rather than allow the investigation to proceed, so that he could succeed to the presidency. Díaz Herrera did not need much convincing. Shortly after the president’s return from a speech at the United Nations, he was summoned to PDF headquarters. There top officers detained and badgered him for fourteen hours, until he agreed to take leave or step down as president, which the military portrayed to the public as his resignation. At the end of the ordeal, he looked Noriega in the eyes and said, “Remember my words, you are going to regret what you are doing here.” And four years later the general went to jail in the United States, later suffered prison in France, and ended up in Panama’s penitentiary, released to house arrest just two months before his death in March 2017.Footnote 43

During the coup against him, Ardito Barletta received encouragement from Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Elliot Abrams to “hang tough,” despite no concrete support. He later learned that Pentagon operative Nestor Sanchez had apparently condoned the coup. Ardito Barletta believed that the situation had become hyper-polarized, and he mistakenly thought that the military would back down. He received condolences and job offers from colleagues in Washington but declined them. The Washington Post denounced the coup as the “beheading of Panama,” alluding to the Spadafora murder. The new regime, meanwhile, condemned many of the president’s allies as traitors of the nation, including prominent figures like Gabriel Lewis, Fernando Eleta, Roberto Motta, and Mario Galindo.Footnote 44

The Noriega Crisis of 1987–89 and the National Civic Crusade

The reasons why American leaders seemed willing to accommodate strongman Noriega in the mid 1980s, with a civilian front man like Ardito Barletta, have been told many times and still echo in the memories of American news consumers from that era. Later, most of these same US leaders turned against the dictator and carried out a trenchant campaign to push him out or remove him.Footnote 45 The US press bombarded the American public with stories that demonized Noriega. The New York Times’ Seymour Hersch had helped launch the campaign against Noriega with a blockbuster article on June 12, 1986.Footnote 46 Between then and the invasion and capture of Noriega in December 1989, thousands of stories appeared in the press around the world, prejudging him. Afterward, many “instant” trade books were published about the general and his demise, such as those by Kempe, Sánchez Borbón and Koster, Woodward, Dinges, Buckley, and Weeks and Gunson. His rise and fall in the court of public opinion could not have been more dramatic.

Some of the reasons Noriega had seemed appropriate for the role of strongman in 1983–84 evaporated in following years. For one, several other military regimes in South America, along with their national security doctrines, relinquished power. The Central American conflict moved toward resolution, no longer requiring a broker in Panama. The Cold War itself drifted toward conclusion, removing other justifications for supporting dictators. Finally, some US congressional opponents of giving the Canal to Panama played up the Noriega crisis as a strategy for annulling the 1977 treaties.Footnote 47 By 1989, Noriega had been thoroughly vilified by the US government, the press, and public opinion.

The “stability” that Noriega supposedly provided (as Torrijos had done before him) grew tenuous in the mid 1980s. Foremost among troubling developments was an open break between Noriega and rival Díaz Herrera. The latter had served as chief of staff and expected to succeed to commander in 1987, as had been promised when Noriega became comandante. When Noriega dismissed him, he retaliated by publicly denouncing the dictator with graphic descriptions of wrongdoings.Footnote 48

Although much of the growing opposition to Noriega originated overseas, Panamanians also mounted a serious movement against his regime that ranged from academic denunciations to street protests. Its origins went back to the 1968 coup and mobilized well-to-do professionals and their families who found their well-being threatened by the military government. During the 1970s, opposition bubbled along mostly underground, in the form of clandestine publications, student activism, anti-government networks, and guarded newspaper columns.

La Prensa clearly served as the flagship newspaper for the opposition in the mid 1980s. It supported Arnulfo Arias in the 1984 election, denounced the death of Spadafora in 1985, calling for a full investigation, and reprinted the Seymour Hersh and other revelations from the US press in mid 1986.Footnote 49

Student protests and repression expanded in July 1986, with street clashes, police raids on schools and the University of Panama, and mobilization of riot police nicknamed the Dobermans for their vicious tactics and black uniforms. Students denounced mistreatment and jailing of Professor Miguel Antonio Bernal and Guillermo Sánchez Borbón, a popular columnist with La Prensa. Police clubbed protesters and fired tear gas to disperse them, only igniting more resistance.Footnote 50

The protest movement erupted again during the Díaz Herrera crisis of June 1987, as people opposed to the regime believed that its end was imminent. Tens of thousands demonstrated, and hundreds of civic organizations aggregated into a loose coalition, the National Civic Crusade.Footnote 51

Anti-government protesters in mid 1987 organized marches with placards and chants, pot-banging, and white scarves. Their demonstrations quickly drew attacks and dispersal by the Dobermans. Such protests, drawing students from the universities and high schools, highlighted middle-class dissatisfaction with the regime. Even some lower-class protesters made their opposition to Noriega heard.Footnote 52

Other organizations joined in. Business associations called several general strikes in 1987, signaling their disapproval of their diminished civic freedoms and constrained economic possibilities. Civic clubs, like Rotary, Lions, Kiwanis, and the Chamber of Commerce, and others like Aurelio Barrios, also registered their opposition to the unconstitutional regime.Footnote 53 Much of this was covertly encouraged by the US State Department. Meanwhile, Noriega had La Prensa seized and shut down, not to reopen permanently until early 1990.

The 1989 election debacle clinched most observers’ conclusion that Noriega had become a demon who should be removed from power. Noriega went on the defensive due to the US sanctions and diplomatic campaign against him, but to assuage opinion he called for a presidential election on May 7, 1989. He chose friend and business associate Carlos Duque to head the ticket. The opposition mobilized behind standard-bearer Guillermo Endara of the Panameñistas for president (Arnulfo had died the previous August). His allies Ricardo Arias Calderón of the Christian Democrats and Guillermo “Billy” Ford, of MOLIRENA and the business community, ran for first and second vice president. Few observers were sanguine about the opposition’s chances to vote out Noriega, but everyone agreed that it would be a plebiscite on his regime.Footnote 54

Because of skepticism lingering after the 1984 election, many groups offered to monitor the elections in 1989, including the Carter Center, the European Parliament, the OAS, the US State Department, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and various former heads of state.Footnote 55 Noriega acquiesced, certain that his influence on the Electoral Tribunal and police watchers would help his candidate prevail. After a massive turnout on election day, the vote-counting arm of the Tribunal went to work, while Noriega agents alternatively stole ballot boxes and attempted to alter the results tabulated by computers. Observers witnessed gross violations of the rules and denounced them to the international press. Independent exit polls showed the opposition winning by margins so large that no amount of fraud could overcome them.

Three days after the election, Endara, Arias Calderón, and Ford led a march to the presidential palace to protest these government actions. They were attacked by irregular militiamen named dignity battalions or “digbats,” who killed Ford’s bodyguard. The thugs attacked and bloodied the candidates, and images of the melee went out to a shocked world.Footnote 56

Noriega and the Tribunal cancelled the election results on the grounds that legal procedures had been violated. He installed another puppet, Francisco Rodríguez, as provisional president on September 1, 1989, the seventh to serve in eight years.Footnote 57 Less than four months later, US armed forces invaded Panama to arrest Noriega, restore constitutional government, and ensure implementation of the 1977 treaties.

Assessing Blame

There was plenty of blame for the Noriega crisis to go around. Noriega himself misread US intentions until the last minute, believing that his skills at bluffing the gringos would stave off their overwhelming military superiority. He made the mistake of having his legislature declare that the United States had put Panama in a state of war, which some media quickly twisted around as “Noriega declared war on the United States.” His long association with prominent figures in the US government, including now-president Bush, led him to believe he could simply outmaneuver them. His wanton execution of officers who tried to overthrow him also warranted decisive sanctions.Footnote 58

President George H. W. Bush and his advisors also merited blame, for keeping Noriega on the payroll in the intelligence network for so long, even resurrecting him after Carter had let him go. Presidential candidate Bush killed a mid-1988 proposal that might have produced Noriega’s departure, fearing that “dealing with a dictator” would harm his election chances, while ignoring the prolonged torment the Panamanian people were suffering under economic sanctions.Footnote 59 The defense establishment had encouraged Noriega’s enhancement of PDF powers in 1983, arming him and giving him roles in international affairs that were inappropriate for a military chieftain. By 1985, however, the State Department and the DEA had already cranked up a campaign against Noriega.Footnote 60 Then, before Bush decided to invade, he could have taken the counsel of General Fred Woerner, head of Southcom in Panama, who did not favor an invasion. Instead the White House replaced Woerner with General Maxwell Thurman (nicknamed “Mad Max”), who colleagues described as anxious to get on with the job. Finally, the Zonians who remained in the PCC deserve some blame for making the treaty implementation as difficult as possible, in the hopes that it might be judged failed and be revoked.Footnote 61

Most diplomats we have spoken with believe that the invasion was an unnecessary and mistaken act, a fallback to outmoded gunboat diplomacy, and a violation of international laws we were party to, including the charters of the UN and the OAS.Footnote 62 Assigning blame and second-guessing, however, are not historical analysis, which requires a longer view of causes and outcomes.

Like the 1984 election, the Christmas invasion of 1989 (code named Just Cause) marked a major turning point in Panama’s history, unfortunately, one over which its citizens had no control. Post-invasion President Guillermo Endara told a reporter it had been like a “kick in the head … We were not really consulted.” A rich literature has accumulated about this episode, the United States’ biggest military undertaking between the Vietnam War and Desert Storm.Footnote 63

Historian Greg Grandin looked back at the invasion on its 25th anniversary, trying to gauge its longer-term causes and effects. He noted that the top members of the Bush security team found themselves uninformed about Panama and unsure what to do with Noriega.Footnote 64 They opted for a rapid, surgical invasion with overwhelming force without defining its objectives and exit strategy. When it was over, they rejoiced at its tactical success, in sharp contrast to the flawed invasion of Grenada six years earlier. They also ignored or played down the extensive civilian casualties and collateral damage to Panama City, on the heels of years of economic sanctions. Bush declared that with Just Cause, the United States had kicked the “Vietnam syndrome,” that is, its reluctance to engage in military operations overseas.Footnote 65

Grandin found longer-term implications of the invasion. The Berlin Wall had just fallen weeks before, so in hindsight Just Cause foreshadowed how the United States might deal with the world after the end of the Cold War, in its new role as sole superpower. In this context, Just Cause was a dress rehearsal for Desert Storm a year later. And it shaped the mentality of a generation of “neo-conservative” (neocon) strategists, who militarized US foreign policy and who rose to influence under Bush’s son, George W. Bush, a decade later.Footnote 66

Panamanians who lost loved ones, property, or their liberty in Just Cause may not take much consolation from Grandin’s analysis, but it shows how small nations can lose control of their destinies and be mistreated by large ones in the long sweep of history. Meanwhile, curious readers have available book-length accounts of the invasion from Panamanian viewpoints, which may be supplemented with the documentary “Invasión,” by Abner Benaim, aired in 2014.Footnote 67

Canal Transition

Implementation of the 1979 Panama Canal Act (also known as PL 9670 and the Murphy Law, after its sponsor Congressman John Murphy [D-NY]) proceeded according to a number of schedules or calendars, as established by the treaty and augmented by the law.Footnote 68 The Carter administration had drafted implementing legislation, which it passed on to President Royo in Panama for his approval. The latter, a lawyer, pointed out items where the draft diverged from the treaty and Panama’s expectations.Footnote 69 The White House did not address the Panamanian complaints, and as noted in this chapter, the House of Representatives developed its own bill. The drafters were led by Representatives Murphy, archconservative Robert Bauman (R-MD), and other avowed enemies of the treaties. Rather than create an independent public corporation, as the treaty and Carter draft had called for, their version kept much closer control, especially fiscally, over Canal management. Many Panamanians and their sympathizers believed these congressmen were coached by Zonians, who hated the treaty, and were aided by Murphy’s chief of staff and former Canal legal counsel, W. Merryl Whitman.Footnote 70

The House bill made the PCC an agency of the executive branch funded by annual appropriations, subject to continuous congressional oversight, rather than a government corporation financed by its own revenues and expenses. It also made the PCC board supervisory rather than managerial, concentrating power more firmly in the hands of the administrator and his superiors in the Pentagon. Whitman then helped create a new position, that of chief engineer, who had to be a US citizen. He explained that this would make the deputy administrator, a Panamanian, redundant. Given these shifts in structure, the four Panamanian board members also became largely powerless. The Carter administration intention of binational and independent Canal management became impossible.Footnote 71

President Carter appointed two men to lead the PCC. Dennis “Phil” McAuliffe became administrator, and his Panamanian counterpart, Fernando Manfredo, took the deputy administrator position.Footnote 72 McAuliffe had served as commander of Southcom in the Canal Zone for the previous four years and was familiar with and supportive of the treaty and transition to binational management. He held the post until 1989, under the Reagan and Bush administrations. Manfredo had served on the Panamanian treaty negotiating team in 1975–77 and was accepted by the US side to serve as deputy administrator. Nominated by Torrijos and approved by Carter, Manfredo ended up in that role throughout the 1980s and became the first Panamanian administrator in 1990, according to the terms of the treaty, albeit briefly.Footnote 73

Michael Rhode, Jr., played a key role in drafting the Act and in Canal administration during the 1980s, a role even more critical after the 1989 invasion. Serving as secretary of the PCC’s Washington, DC office, he took up duties that far exceeded his modest title: he managed liaison between the Canal and Congress and with numerous government agencies whose actions were critical for Canal operations. He helped to brief Ronald Reagan’s 1981 nominee for president of the PCC board, William Gianelli. From Manfredo’s point of view, Rhode became an eminence gris.Footnote 74

General McAuliffe, who was not a Zonian, worked well with his Panamanian counterpart and made every effort to implement the treaty, despite the difficulties Congress threw in his way.Footnote 75 Zonians, however, never reconciled to the treaty and followed it only grudgingly, in the spirit of Spanish colonial administrators who said “obedezco pero no cumplo,” i.e. I obey but do not carry out. Even if Panama eventually took over the Canal, they reasoned, they would not facilitate the process. Manfredo once remarked that the Zonians’ idea of “transition” was that Zonians would run the Canal until they turned off the lights on December 31, 1999; Panamanians could come in the next day and turn the lights back on, if they could find the switch.

During the 1980s, the Canal operated under the almost exclusive authority of the US government; Panama played little part in policy decisions, despite the binational façade of the PCC. President Ardito Barletta, in office 1984–85, said Canal matters occupied little of his time. Panamanians mostly stood on the sidelines, hoping for a bountiful future of cash transfers, new jobs, and business opportunities. Most were sorely disappointed. This was especially true before many Panamanians became conversant in Canal operations and during the period the two governments sparred over the tenure of General Noriega in power. During the 1990s, as more Panamanians rose into executive roles in the Canal and better relations prevailed between the countries, board members and managers, calling themselves “canaleros” (canal men), gradually exercised more influence.

Five US and four Panamanian members comprised the board of directors of the PCC, all nominated by their respective presidents and ratified by the US Senate. The board always approved the decisions of the administrator, because its US members, a majority, were obliged to vote as their president instructed, and he in turn reported to the Secretary of the Army and the Secretary of Defense in Washington. And if that weren’t enough top-down control, Congress required that the PCC capital and operating budgets be submitted annually for its approval until 1987, when they adopted a more flexible rotating fund budget.Footnote 76

To coordinate the actions of the many US agencies with a stake in the Canal and ancillary military operations, the White House in the 1960s had established a Panama Review Committee, under the guidance of the US ambassador and the Canal Zone governor. The Southcom commander usually took an active part, also. During treaty implementation, the committee oversaw a large number of joint commissions and subcommittees to discuss and define policy across a range of matters, with special attention to environmental protection and defense. A former ambassador said that the military dominated its deliberations.Footnote 77

Panamanian board members, despite having no real decision-making power, gained valuable experience while watching issues presented and approved, and they became familiar with the complex structures and operations of the Canal. To improve their efficacy, Manfredo suggested to Torrijos that Panama create an advisory board to coordinate Panama’s participation in Canal management, autonomous like a transit authority in the United States and as a counterpart to the US review committee.

In 1978, Torrijos established the first of several such bodies. One version was the Panama Canal Authority (ACP), under the direction of Torrijos associate Gabriel Lewis Galindo, designed to centralize decision-making under the executive branch.Footnote 78 Problems arose immediately, as agencies and strong-willed politicians fought for access to returned lands and facilities. Two notable examples were the National Guard and the Port Authority, which claimed military assets, the ports, and the railroad. The Authority succumbed to such competing pressures in 1982–83 and was eventually replaced by the Executive Directorate for Canal Matters (DIPAT), charged with educating, coordinating, and advising its board members. It was lodged in the presidency at first but later moved to the ministry of foreign relations.

From the outset, Panamanian board members found themselves largely ignored and expected to play subordinate roles. But they insisted on challenging the Act, especially the ways it violated the treaties. Such recriminations fell on deaf American ears, so the Panamanian board members had little influence in the early years. By its third year, however, the board settled down and became a more constructive forum for discussing Canal policies.

US ambassador Ambler Moss elucidated a major contradiction in the Board’s mandate:

Any Panamanian Government official or businessman knows what a board of directors is in a corporation. But they quite rightly question the role of a board of directors in an appropriated fund agency. It doesn’t make sense; it doesn’t fit legally somehow.Footnote 79

The control Congress retained over the budget eviscerated the powers of the Board and frustrated the Panamanians’ expectations of playing a part in Canal management.

The same contradiction hobbled the Coordinating Committee of division chiefs and their Panamanian counterparts. Deputy Administrator Manfredo observed that “a US representative, a bureau director in the Canal Agency, had more power than the Panamanian member who, as part of the Government of Panama’s Executive Branch, was not in a position to affect the day-to-day operations of the Canal.” Asymmetry undermined a sense of shared responsibility.Footnote 80

Panamanian board members’ concerns in the early years ranged from widening the Culebra/Gaillard Cut (the longer excavated portion on the Pacific side of the Canal), continued waterway maintenance, imbalance between US and Panamanian administrative authority, personnel policies, a second bridge over the Canal, limited power to raise tolls, and costly bureaucratic duplication. Again, Panamanian board members’ complaints were largely ignored – one critic called them an “echo chamber” that only heard its own voices.Footnote 81

This awkward collaboration persisted until 1985, when General Noriega asserted more control over his board members and ratcheted up conflict by appointing an iron-handed official, Major Delgado, to keep them in line. Binational cooperation only reappeared after the invasion.Footnote 82

Reversion

The immediate turnover of lands and assets in 1979 became the big story for Panama in this period, far overshadowing the small part the nation played in Canal affairs. The assets included the Panama Railroad, the ports of Balboa and Cristobal at either end of the Canal, and 58 percent of the lands formerly contained in the Canal Zone, which ceased to exist on October 1, 1979.Footnote 83

Administratively, the ports and railroad transferred to Panama’s Port Authority, even though little business went on in these facilities.Footnote 84 The railroad and ports turned out to be white elephants, a drain on the treasury. The railroad had long been neglected and used largely for moving personnel and light cargo around the Zone. The ports handled scant trade and had not been modernized in years, especially given the containerization revolution underway. The two workforces had little to do but were protected by local unions. To spare the government of Panama from having to fire hundreds of redundant employees upon the transfer, the Canal personnel office pensioned off most of them.Footnote 85

The reverted lands included most non-US employee housing (4,300 units), schools, recreation areas, and community buildings. The ACP began to inventory these properties and attempted to provide maintenance until they could be sold to private owners. Considerable pressure arose to show favoritism for powerful people or to sell properties at below market rates, which made the work of the ACP more difficult. This process took many years to complete, during which time critics of the treaty pointed to un-mowed grass, sweetheart deals, run-down neighborhoods, and buildings deteriorating in the tropical climate.

One property scheduled for reverting to Panama proved especially troubling. The School of the Americas (SOA), an army training facility operated at Fort Gulick for Latin American military officers since the end of World War II, was not covered in the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) negotiated for the other US bases in Panama. Therefore, it would transfer to Panama in 1984 unless a separate SOFA was signed. Noriega, who had taken several courses at the SOA, intended for the United States to continue using the facility but did not wish to give permission publicly, for fear of protests by nationalists. Noriega wanted the SOA but without a SOFA, according to a State Department official. The Pentagon was wary of any deal without a legal basis, however, and at the last minute decided to pull the school out and relocate it at Fort Benning, GA. The incident created doubts about Noriega’s ultimate loyalty to the US military.Footnote 86

Manfredo had to deal with a particularly thorny problem with strong cultural overtones: properties built by non-profits, particularly churches, recreation centers, and clubhouses. The close-knit society of the old Zone had over 500 such organizations, which expected to purchase them at nominal prices. But the treaty only provided for a grace period of thirty months, beyond which they would have to regularize their ownership and operations under Panamanian law. In some cases, their fragile finances would not allow this, and they closed their doors. Manfredo made a concerted effort to help most make the transition, knowing that they promoted better morale in the Canal workforce and provided essential social services. He commented that half his time was devoted to handling such special cases.Footnote 87

Most of the transferred lands, largely secondary tropical forest, lay along both sides of the Canal and to the Northeast, including the Chagres River basin, Alahuela (formerly Madden) Lake, and the southern slopes of the central Cordillera mountains. Presidents Royo, Jorge Enrique Illueca, and Ardito Barletta acted quickly to designate forest lands along the Canal as national parks, to prevent their being despoiled by developers and squatters. They created several large forest reserves: Parque Soberanía in 1980, Parque Metropolitano in 1985, and Parque Camino de Cruces in 1993. For many years, the government of Panama struggled to deal with farmers and ranchers – estimated as perhaps 100,000 – who quietly penetrated the former Zone lands, because their clearings jeopardized the Canal and contributed to siltation in Gatun Lake. The establishment of a national forestry agency in 1986, INRENARE, later a part of ANAM, did not fully remedy the problem.

The joint policy committee set up for watershed protection attempted to educate the public about the potential dangers of deforestation and to create awareness among the political elite of the urgency of protecting the watershed. They established the Watershed Management Plan to accomplish this, and intellectuals and other opinion leaders embraced it.Footnote 88 They laid the groundwork for later extensive cooperation between Panamanian institutions, the Panama Canal Authority, and USAID.

The protection of the regional watershed concerned more than simply Canal maintenance. These same waters generated electricity, irrigated farmlands, and supplied consumers in the terminal cities. And ultimately, the Canal which Panama would take over in 1999, a historic patrimony of the nation, would succeed or fail largely on whether they could sustain the hydrologic system of the Chagres River basin. Eventually, the successor Autoridad del Canal de Panamá (ACP), created in the mid 1990s, assumed responsibility for protecting these lands.

Under the treaty, the remaining 42 percent of lands and waterways necessary to operate and defend the Canal was allocated to the Panama Canal Area, under the jurisdiction of the PCC, and military zones containing US bases, under the Department of Defense (DOD), for the remainder of the treaty period.

In the transferred or “reverted” areas, Panama immediately assumed responsibility for ordinary public services, including mail, police, courts, jails, fire protection, utilities, and garbage collection. In 1984, these services were extended to the whole Canal Area, excepting military bases. Within two years, the Panamanian police, their Canal counterparts, and the national courts functioned very well, a bright spot in treaty implementation. Manfredo agreed to a special pay bonus to help US employees adapt to Panamanian services and stores, even though it was not authorized in the treaty.Footnote 89

Several observers noted that the most successful phase of implementation consisted of new joint police patrols, made up of Panamanian and former Zone policemen, which began on October 1, 1979, and ended thirty months later. Their efficacy stemmed in part from the fact that for years the two forces had coordinated, cross-trained, shared intelligence, and enjoyed informal communication. This early success engendered confidence, especially among the US Canal employees, that their lives could carry on without immediate danger.Footnote 90

Other changes in services after 1979 involved schools, hospitals, retail sales, and US housing, many of which were taken over by the Army, Air Force, or Department of Defense Dependent Schools System for the duration of the treaty. Most of these took place among US agencies and had little effect on Panama, except for Panamanians employed by the PCC or DOD.Footnote 91

Disagreements arose, however, as to the public services available to members of the US armed forces and their dependents. Military personnel, their spouses, and DOD employees continued to run their own operations, including APO mail, police, and the coveted commissaries and PX stores. They were also exempt from paying rent on residences, which would have brought in over two million dollars a year. Finally, the embassy’s surreptitious use of the diplomatic pouch for Zonian mail also rankled, because it took away hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue from the PCC. These constituted questions of equity between Panamanian and US employees, not just budget issues.Footnote 92

Panamanianizing the Canal

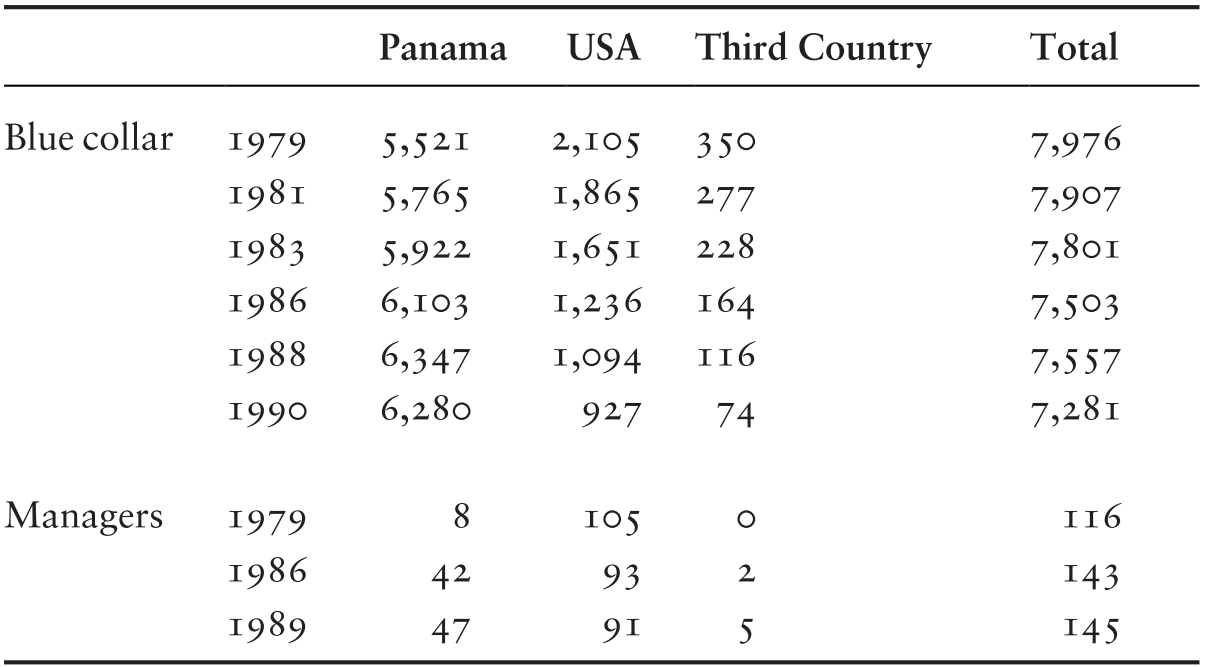

During the early 1980s Canal managers faced multiple challenges. Foremost, they had to ramp up recruitment and training of Panamanians for positions at all levels of responsibility, with the goal of nearly 100 percent Panamanian staffing by the time the Canal was turned over in 1999. Millions of dollars were expended for this purpose, and by 1990 about 86 percent of the total workforce was Panamanian, up from 69 percent in 1979. Recruitment and training for executive, management, and senior maritime positions, especially pilots and captains, lagged, however, reaching less than a third by 1989.Footnote 93

The PCC rolled out a wide array of special programs to prepare Panamanians for successful employment and/or advancement: apprenticeships for craftsmen, towboat mate training, pilot understudies, pilots-in-training, towboat engineer training, clerical training, career internships, upward mobility, career internships, and cooperative education tracks for college students. The first Panamanian administrator later remarked that the PCC was a veritable university of education.Footnote 94

Canal pilots, the men who guided ships through the Canal itself, proved to be the most difficult work category to Panamanianize. Their jobs, requiring exacting skills and experience, were far and away the most demanding and paid the highest wages, comparable to senior airline pilots. It also had the strongest union. The administrator recalled that negotiations with their union in 1980, 1983, and 1985 proved very arduous. But once the other US employee unions accepted the treaty, the pilots finally acquiesced. By the late 1980s, twenty Panamanian pilots were qualified, with another fifteen in the pipeline.Footnote 95 Still, it took many years for pilots to earn masters’ papers to assume full command of ships in the Canal.

To accommodate the increase in Panamanian employees, the PCC created the Panama Canal Employment System, which reinstituted two tiers of compensation, one for US employees and a Panama Area Wage Base for new local hires. The plan, like the notorious Gold and Silver rolls that had existed through the 1940s, and the Local Rate/US Rate system through the 1970s, was intended to hold down wages so that by 1999 they would be comparable with pay scales in Panama’s economy. This caused such an outcry that the PCC went back to a single pay schedule regardless of nationality. It went into effect between 1983 and 1985 and added some $3 million to the payroll. In addition, by 1986, all Canal employees except senior management were also covered by collective bargaining agreements.Footnote 96

Panamanianizing the upper echelons of Canal management created more difficulties, as Zonians fought tenaciously to protect their high pay and benefits. Table 2.1 shows that less than a third of the managers were Panamanian after more than a decade of treaty implementation. A former Canal executive remembered that PCC board presidents William Gianelli and Robert Page supported the Zonians and attempted to block efforts by McAuliffe and Manfredo to add more Panamanians to management positions.Footnote 97

Table 2.1 Panamanianization of the Canal Work Force, 1979–90

| Panama | USA | Third Country | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue collar | 1979 | 5,521 | 2,105 | 350 | 7,976 |

| 1981 | 5,765 | 1,865 | 277 | 7,907 | |

| 1983 | 5,922 | 1,651 | 228 | 7,801 | |

| 1986 | 6,103 | 1,236 | 164 | 7,503 | |

| 1988 | 6,347 | 1,094 | 116 | 7,557 | |

| 1990 | 6,280 | 927 | 74 | 7,281 | |

| Managers | 1979 | 8 | 105 | 0 | 116 |

| 1986 | 42 | 93 | 2 | 143 | |

| 1989 | 47 | 91 | 5 | 145 | |

Those Panamanians who did win appointments constituted a small but important generation critical for eventually taking over the Canal. From Manfredo on down, they faced discrimination and exclusion on the part of the Zonians. Manfredo’s memoir contains myriad cases of being snubbed and ostracized, beginning with denial of housing designated for the deputy administrator.Footnote 98 He and others had to bear up under this treatment in order to persevere. In 2003–04 Ana Elena Porras collected candid testimonies by a dozen Panamanian and US officials from the transition era that recorded the anger and frustration most experienced.Footnote 99

Panamanians who earned good positions in the early transition included Luis Noli and Anel Belis, public information directors, and George Mercier, head of personnel. Assistant director positions were held by Numan Vásquez (engineering-construction), René Van Hoorde (general services), and Carlos Alvarado (marine division). They were joined by Ricardo Varela (human resource development) and Orlando Allard (pilot training). Several would become top executives after Panama took over the Canal, like Jorge Quijano, Onésimo Sánchez, Rodolfo Sabonge, and Manuel Benítez. Allard went on to represent Panama as ambassador to the International Maritime Organization and founded the Universidad Marítima Internacional de Panamá for training merchant marine officers and seamen and organized the periodic Panama Maritime conferences after the early 1990s. Executive Director Joseph Wood lauded Tilsia McTagger, Equal Opportunity Officer.Footnote 100

To help standardize pay scales throughout the Canal area, the DOD reluctantly agreed on similar wage systems for its local employees at military installations. In the early 1980s, the Canal employment office also instituted Reductions-in-Force (RIFs in federal parlance), so that US personnel whose jobs ended due to transfer of operations to Panama could displace (bump) others below them in seniority if they qualified for the new jobs. Meanwhile, the projected exodus of US employees did not materialize: only about 100–150 Zonians left each year in the 1980s.Footnote 101 Nor did the large-scale departure of West Indian descendant employees occur as forecast: only 1,666 took advantage of 15,000 special US immigration visa slots provided by the treaty.Footnote 102

Assuring proper maintenance of the Canal up to the time of transfer constituted another challenge facing Canal managers. Some projects chosen for funding enhanced efficiency, like widening and deepening Culebra/Gaillard Cut to allow two-way transits of Panamax ships, while others simply kept equipment in working order, like lock locomotives, tugboats, lock gates, hydroelectric plants, and dredging barges.Footnote 103 Capital expenditures, like all outlays, came from a new Revolving Fund set up by the US Treasury Department in 1987, and they usually detracted from the meager funds available to transfer to Panama beyond treaty requirements, especially during the Noriega crisis.Footnote 104

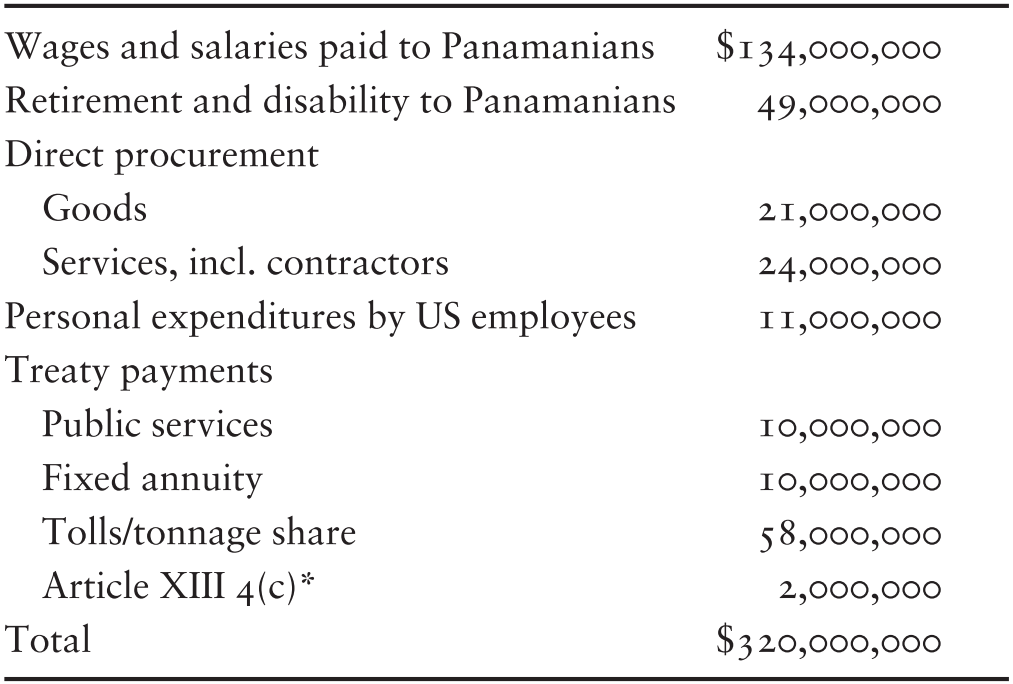

Panamanians had expected a windfall of income from the Canal under the treaty, and in fact treaty-designated payments to Panama rose from only three to around eighty million a year in the 1980s. In addition, the Canal injected more money into Panama’s economy through a variety of means, not simply payment for use of the facility. An estimate for fiscal year 1987 appears in Table 2.2:

Table 2.2 Gross Income to Panama 1987

| Wages and salaries paid to Panamanians | $134,000,000 |

| Retirement and disability to Panamanians | 49,000,000 |

| Direct procurement | |

| Goods | 21,000,000 |

| Services, incl. contractors | 24,000,000 |

| Personal expenditures by US employees | 11,000,000 |

| Treaty payments | |

| Public services | 10,000,000 |

| Fixed annuity | 10,000,000 |

| Tolls/tonnage share | 58,000,000 |

| Article XIII 4(c)* | 2,000,000 |

| Total | $320,000,000 |

* This article provided for giving Panama up to $10 million per year from excess of revenues over expenditures, even though the PCC was not supposed to produce “profits.” In subsequent years, few funds were transferred under this treaty provision. See Chapter 3 for more discussion of this issue.

As employment of Panamanians rose in the 1980s, so did compensation, income tax, and social security contributions, the last two now paid to the government of Panama. The Canal also increased procurement of goods and services in Panama, anticipating the Canal turnover in 1999.

Manfredo explained that while “profit sharing” in the 1980s was minimal, the PCC did invest some $25–30 million a year in improvements, so that the Canal would be maintained and operating well in 1999. Widening the Culebra/Gaillard Cut, the biggest project slated for execution in the late 1980s, would permit two-way transits of the larger Panamax ships using the Canal during daylight hours.Footnote 105 Estimated to cost some $400 million, it was postponed due to the political conflict between Washington and Noriega and to the economic sanctions the United States imposed. It was completed in the early 2000s, along with other maintenance and improvement projects to be discussed in Chapter 3.Footnote 106

The impact of Canal transfers and expenditures fell dramatically in 1988 and 1989, when the US government withheld all funds and business with Panama to pressure Noriega to step down from power. The GDP dropped 20 percent from previous years, and the country began to run out of cash because currency shipments (Panama has used the US dollar since 1905) were embargoed. Blocking social security payments and income tax withholding on behalf of Panamanian employees of the Canal created special hardships, from deputy administrator on down, because the Noriega regime began assessing fines on them and withholding services. They even issued an arrest warrant for Manfredo!Footnote 107

The Canal operated well during the 1980s, despite administrative friction between Panamanian and US authorities. Toll revenues increased slightly in the early 1980s due to increased traffic, especially oil tankers carrying Alaska North Slope crude to the East Coast. In 1983, 9.8 percent higher toll rates, authorized under the Act, went into effect. The following year, revenues remained about the same, as rate increases were offset by the shift of Alaskan North Slope oil to a pipeline that began operations between Panama’s Chiriqui and Bocas del Toro provinces, near the western border with Costa Rica.Footnote 108

The rest of the decade the number of transits remained steady at around 12,000 a year, yet volume of cargo rose somewhat due to a growing number of larger Panamax vessels. Part of the later growth was also due to shipments of Japanese autos to the East Coast in specialized automobile carriers known as roll-on-roll-off or Ro-Ro vessels.Footnote 109

Since the 1960s, the United States had negotiated with Panama for rights to build a sea-level Canal to replace the existing lock Canal, and the 1977 treaty had left that option open. In 1986, the PCC began considering that possibility and others, forming the Tripartite Canal Alternatives Study Group, comprising the United States, Panama, and Japan. They resurrected the sea-level studies (favored by Japan) done in the 1960s and estimated costs, ending up recommending not to pursue that course. Instead, they endorsed either enlarging the existing Canal (along the lines of the Third Locks project of 1939–42) and/or developing what they called the “Centerport,” where the Canal and adjacent lands would become a marshalling center for containers, which carried an increasing share of world commerce, and other lines of commerce.Footnote 110 The added cost of port improvements, railroad reconstruction, and highway connections to achieve the Centerport would be far less than a sea-level Canal, not to mention avoiding the environmental dangers of massive excavation. One incentive to upgrade container handling was the growing competitiveness of the US “landbridge” or intermodal routes, where containers were offloaded on the US West coast and sent by rail to Midwest and even East coast destinations.Footnote 111

Panama’s Economy in the 1980s

Zimbalist and Weeks’s study of the deterioration of Panama’s fortunes by 1990 devoted considerable attention to the economic story. They demonstrated that the country relied heavily on international services to earn its livelihood: the Canal, the banking center, an oil pipeline opened in 1983, ship chandlering, and the Colon Free Zone. Manufacturing and agriculture, by comparison, made up less than a quarter of the GDP.Footnote 112 Despite urging by the US government, the IMF, and the World Bank, Panama found it difficult or impossible to wean itself from its role as service provider. And the economic sanctions applied by the United States from 1987 to 1989 severely hobbled the economy, which Zimbalist and Weeks described as a disaster waiting to happen.Footnote 113

Panama had long been recognized as having one of the most unequal distributions of income in the hemisphere. This resulted from many very poor people, while wealth remained concentrated in the hands of a small elite. Urban migration only shifted poverty from the countryside to the city, rather than ameliorating it.Footnote 114

The early 1980s had proved disastrous for Latin American economies in general, becoming what economic historians called the “lost decade,” when growth stagnated and unemployment ravaged populations. The 1981–82 recession caused extreme hardship, devaluations, and debt moratoria. Panama suffered these effects as well, especially difficult after the relatively expansive years that accompanied Canal treaty negotiations. Torrijos’s death and ensuing political instability exacerbated the economic distress. Fiscal deficits and heavy debt service pushed the country to the edge of bankruptcy. Thus, the 1983 presidential nomination of Ardito Barletta was partly designed to pull the economy out of its spiral. International credit would be essential.Footnote 115

Difficulties aside, the economy rested on fairly solid foundations, because of, rather than despite, its dependence on the service sector. The banking center had grown and prospered in the previous decade, peaking at some $49 billion in assets and nearly 9,000 employees in 120 banks by 1982. It provided liquidity for other activities through loans and deposits.Footnote 116 One downside of the banking industry was its use for money laundering by a variety of clients, including General Noriega. Such activities generated profits, to be sure, but they contributed to Panama’s reputation as a crime-tolerant nation and underpinned some of the indictments used to arrest Noriega. The issue has continued to occupy diplomats and bank inspectors ever since.Footnote 117