This chapter is about stories and the perception of the monastic landscape created by stories – stories told about famous monastic leaders and famous places, and stories told about communities to create identity. But more importantly, it is about the stories of the Egyptian desert embedded within the Late Antique hagiographies that gave meaning to the stories about leaders, places, and community.

Aside from the fact that it makes up the majority of Egypt’s natural landscape, the desert was a central component of ancient Egyptian and Christian theology. The nature of the desert as both a positive and a negative space for spiritual encounters is rooted in ancient pharaonic thought. Before the introduction of Christianity, Egyptians conceived of the desert (dšrt) as the realm both of evil gods, such as Seth, and of the sacred.1 As early as the Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BCE),2 the land for the dead was associated with the sacred or segregated land (t3 ḏsr) and was always located in the desert cliffs that hug the cultivated land below.3 The western bank of the Nile in particular was associated with the land of the deceased. From this space, the deceased could move into the afterworld.4 Despite the fact that the desert has an important place in the religious topography of ancient Egypt, sedentary populations throughout antiquity did not elect to inhabit the desertscape. Family members often visited tombs to make offerings to the spirits of their relatives, but they never lived alongside the tombs.5 A few individuals did reside in the desert, but this was linked to their occupations, such as quarrymen and miners, tomb builders, soldiers on outposts, caravan drivers, and nomads who elected to call the desert their home. In all cases, those living in the desert were only temporary residents. They lived in natural caves, older abandoned tombs, and even the quarries they were cutting for just so long as the job required.6 Yet, monastic stories created a desert that was devoid of the presence of these others and did not recount their narratives. For the conquest of the desert was a story of triumphal occupation by monks, like Antony: “Indeed it was only in the loneliness of this environment, devoid of life and its quiet hardship, that the naked ascetic mind, emptied of all vain images, could attain true spirituality.”7

This chapter examines Egyptian monastic space in the broadest of terms from the imagined landscape of foundation narratives found in the hagiographic tradition linked to five famous monastic sites. Three were locations well known to monastic communities within the Mediterranean worlds of Byzantium and western medieval Europe. Two were known only within Egypt, and yet they were two of the largest and most important for Egyptian monasticism. Read together, the stories of these communities demonstrate how monastic authors spoke of the land, its suitability for spiritual living, and how founders laid claim to the land for monastic habitation. The sites of Wadi al-Natrun and Kellia in the Delta, Bawit in Middle Egypt, and the sites around Tabennesi and Sohag in Upper Egypt offer rich stories for analyzing how monastic authors described the environment and the need to build in locations not previously inhabited. I use these five examples to illustrate the rhetorical strategies utilized by monastic elites to construct a particular perception of the monastic mindscape that would come to define monastic literature for centuries to follow. But in order to understand how the stories of relocation and occupation developed, we begin by exploring why monastic communities moved to the fringes and how they were part of a longer tradition of moving outside of the city to inhabit new landscapes.

The Impulse to Move to the Fringes

The desert is an important spiritual realm in biblical topography and naturally expanded into monastic teaching as a land both terrifying and beautiful.8 Both the Old and New Testaments contain references to the desert as a space conducive for powerful spiritual encounters – both positive and negative. For the Hebrews, the desert was a space of punishment for forty years. The environmental challenges of the landscape provided all the necessary tools for teaching the Hebrews to rely on God. In the New Testament, the author of Hebrews evokes the bleakness of the desert when describing the prophets and their suffering as they “wandered in deserts and mountains, living in caves and in holes in the ground” (Heb. 11:38).9 Despite these harsh and punitive qualities, other biblical writers described positive and protective elements of the desert for those called to God’s service. For example, David and his men successfully eluded Saul in several deserts (1 Sam. 23, 24); later Elijah lived in the Judean desert, fed by ravens sent by God (I Kings 17); and gospel accounts tell of John the Baptist living and preaching in the desert of Judea, subsisting on locusts and honey (Matt. 3:1–4).

The most powerful biblical image of the desert is found the temptation of Jesus (Matt. 4:1; Luke 8:29). With this story the desert is both a teacher and a facilitator for encounters with the spiritual realm. It is in the desert that Jesus meets the devil, and we have the fullest development of the desert as the home of demonic beings. Although the desert could be used for God’s ultimate purpose for training and protection, it was clearly also the residence of creatures opposed to God or those removed from God’s care (Lev. 17:17; Isa 13:21; 34:14; Matt 12:43).10 Jesus consciously and deliberately left his community to enter into a space that would provide the appropriate conditions for fasting and for prayer. The experiences of Jesus in the desert set up the model for later monastics who regard the desert as the training ground for their spiritual disciplines. The immediate encounter with the devil, who resides in the desert, allows Jesus to employ tools for spiritual combat. He recites Scripture and affirms knowledge of his true identity, thereby deflecting Satan’s temptations. Similarly, monks would regard the desert as a spiritual training ground, akin to an athletic training ground, that would force a confrontation with their own temptations and demons.11 The desert provided an environment for individuals to test the depths of their desires and dedication. It became an essential part of the spiritual topography of monastic life, such that monks would seek out caves, holes, deserts, and mountains where they could hope to prove themselves worthy.

The desert was a place of temptation, but it was equally a demanding teacher: “Truly that desert leads each person into feats of asceticism, whether he wants to or not.”12 The very nature of the desert provided physical and emotional challenges, testing the resolve of individuals who wished to emulate Christ.13 It was not a space for the weak-willed. Sometimes the desert was used episodically for training a monk. Shenoute sent a monk to live in a cave for just under a year until the weak spirit fled from his body. On acknowledging the strange phenomenon of seeing the spirit leave, Shenoute invited the monk back into the community, who then left the desert.14 Monastic literature recounts several stories of individuals who are either turned away or required to wait a period of time before being accepted into the community. The individual was constantly tested, and many were found lacking in maturity or even practical skills needed to sustain a life in the desert. Such a life was not impossible. Numerous men elected to relocate to the desert in substantial numbers. According to Athanasius, even the devil started to feel the encroachment into his land when Antony modeled successful ascetic living. Antony’s success was so great that the devil feared Antony “would turn the desert into a city of asceticism.”15

Relocation Traditions in Roman Egypt

The impulse to move to a new location and to embrace a new philosophical outlook was not unique to Christianity or even monasticism.16 The Mediterranean world witnessed how Cynics, Epicureans, Stoics, Neo-Platonists, and Neo-Pythagoreans all endorsed a moderate form of askesis, or training, that monitored the body and the mind in order to meet larger goals.17 The ultimate aim was to practice restraint in indulgences rather than to abstain entirely from the pleasures of the world. Moderation, as espoused by Plato, was a larger challenge than complete asceticism or indulgence; to practice restraint reflected one’s ability to control the body with limits.18 The mechanism for control grew from the delicate balance between controlling one’s desires and actions. The foods one ate, the amount of sex one had, and the bonds one held to another could all enhance or hinder progress in the philosophical life.19 To prepare and to train oneself was the basic meaning of askesis for many athletes and gladiators as well as the philosophers. They practiced in spaces with like-minded individuals and often worked at the pleasure of their trainers and sponsors. It is therefore not surprising to find monastic authors speaking about their lives as ones dedicated to philosophy and using language evocative of athletic training: “[I]f one were to call them a choir of angels or a band of athletes or a city of the pious or a new choir of seventy apostles, one would not err in appropriateness.”20 Just as athletes and philosophers trained their bodies, monks trained to monitor and control their diets, sexual activity, and interactions.21 One essential component of this new life was the need to move to spaces with others who shared the same goal.

In Roman Egypt philosophers, athletes, and monks shared an ascetic imperative – a need to move away from the culture of the world and toward a culture that elevated the divine.22 In particular, the ascetic movement involved a widely held belief that particular areas should and could be set aside for religious activities. These sacred spaces were the only appropriate areas for the practice of contemplation, or the act of seeing the divine. The relationship between the divine and the individual was enhanced by the condition of the space. This belief matches well with Lefebvre’s definition of social space as a place that is altered through the ideas individuals hold about a particular space. The link between spaces with acts of contemplation was central to ascetic beliefs and behaviors. Two examples from Roman Egypt illustrate the critical importance of spatial separation for fostering spiritual living prior to the emergence of monasticism. Both provide a rhetorical context for understanding why monastics moved into the deserted regions, whether in houses in a town, the fringes of the fields, or in the escarpments. The examples also contextualize how the generalized monastic landscape emerged in Egypt.

Porphyry (d. ca. 305) preserved an account of the old Hellenistic-Pharaonic priesthood in Egypt, as reported by Chaeremon, a first-century CE Memphite priest, in De abstentia 4.6–8.23 Chaeremon’s report demonstrates that observers of the practices of these priests had an awareness of the use of architectural space for spiritual living and of the necessity to be within that space for maintaining spiritual commitments.

[T]hey (the priests) chose the temples as the place to philosophize. For to live close to their temples, was fitting to their whole desire of contemplation, and it gave them security because of the reverence for the divine ... And they were able to live a quiet life ... They renounced every employment and human revenues, and devoted their whole life to contemplation and vision of the divine. Through this vision they procured for themselves honor, security, and piety; through contemplation they procured knowledge; and through both a certain esoteric and venerable way of life.24

Chaeremon and Porphyry consciously linked a devotional life to philosophy. The quietude of the temple enhanced the conditions the priests desired for living a contemplative life. Residence within the temple required that the priests reject the typical forms of wage-earning that were common in the cities and towns of Roman Egypt.25 They could live in quarters in the temple and dedicate their time to all spiritual matters. Chaeremon describes how participation in temple life necessitated that priests separate themselves physically from others. The physical area of the temple served as a distinctly social space for encountering like-minded individuals and for contemplating the divine. The space beyond the temple’s precinct held distractions that would be detrimental to the goals of the priests for a quiet and noble life.

Similar themes for a generalized religious landscape are found in a portrait of a contemporary group of Jewish ascetics living near Alexandria and known to Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE–50 CE) as the Therapeutae.26 In a short treatise called On the Contemplative Life, Philo describes in detail the beliefs and customs of the Therapeutae and then describes how they live.27 No archaeological evidence has been found to belong to the settlement of the Therapeutae, and many scholars doubt whether it was an actual community. Despite its questionable existence, Philo’s presentation contains elements of a generalized and idealized landscape that reflects ideological expectations of a well-designed life. His classification of the community as philosophers illustrates his belief that the Therapeutae were pursuing knowledge akin to other philosophical communities of the time.28 Philo’s account includes a thorough consideration of how daily activities were conducted in particular spaces; how these activities differed from, or were superior to, practices of urban life; and how the overall goal of the Jewish philosophers was met only when they physically relocated to an area outside of Alexandria.

The Therapeutae originally resided throughout all of Egypt, but Philo points out that they preferred an area near Lake Mareotis, south and west of Alexandria.29 Here individuals, motivated by their “longing for the deathless and blessed life,” established themselves in a new settlement.30 Philo explains that the Therapeutae possess a logical rationale for relinquishing personal goods and relocating to foster their new identity: “[T]hey do not migrate into another city” for they regard the city as a place “full of turmoils and disturbances,” electing instead to live “outside the walls pursuing solitude in gardens or lonely bits of country.”31 Philo seeks to explain the rationale behind the belief that divesting oneself of possessions will produce a type of mental freedom from the anxieties of ownership. Philo is determined to prove that these individuals were different from those who moved aimlessly from city to city. The Therapeutae moved deliberately to free themselves from the disturbances found from living in close proximity to one’s family. The resettlement outside of Alexandria did not stem from fear but rather from a serious consideration of how to construct the proper environment for fostering the pursuit of wisdom.

According to Philo, the Therapeutae selected a variety of locations to live in, such as sites outside of walled settlements, gardens, and abandoned or deserted areas. However, these sites were not completely isolated, for they were in sight of farms and villages.32 It was in these areas that Philo says the Therapeutae pursued solitude and wisdom. He uses eremia (Gk.) in three distinct but related ways to convey various notions of the desert and desert places. First, eremia is a state of mind; second, a physical place; and third, a quality or nature of a place. In all three usages, eremia links ideas of solitude, wilderness, desertion, and abandonment.33 However, these ideas do not equate to isolation, but rather to a clear separation between individuals and other built environments.34

After moving to the new residences, the Therapeutae devised a way of living that was remarkably similar to that of later Christian ascetics.35 The Therapeutae lived in simple houses to provide protection from the extreme heat of the day and cold at night.36 Although Philo does not expressly state whether or not the Therapeutae built these dwellings, based on the descriptions of the activities that were carried out in these spaces, it is unlikely that they were already in existence in this area.37 Philo describes the general layout to include a sanctuary (semneion) or monastery (monastērion).38 The houses contained at least two rooms, if not three, with one designated as a special room for spiritual activities. The room is described as a holy or a solitary room (monastērion). The monastērion, or sacred room, existed solely for the occupant to aid in the cultivation of the memory of God.39 Specifically, Philo says this space helps them be aware of God while awake and while dreaming. Within these spaces individuals prayed at appointed times, dedicated the day to the reading of Scripture, and studied the allegorical interpretation of Scripture for hidden meanings. The obvious similarities between the practices of Philo’s Therapeutae and Athanasius’s Antony impressed Eusebius so much that he considered the Therapeutae as an early Christian community.40

In the end, the two examples may not reflect actual practices of Egyptian priests or those of later Alexandrian Jewish ascetics. However, the portraits do highlight a religious and philosophical tradition about space, religious devotion, and the underutilized landscape. The desert and deserted places both in a village and on the edges of the inhabited areas became very attractive locations for monks to use as new settlements. The importance of the desert in biblical topography is clear. It is a space to confront demons, to challenge oneself, and to encounter God. Together these ideas combined to make a compelling argument for the value of the Egyptian desert as a spiritual training arena. In seeking out locations outside of the normative urban environment, monastics were part of an older tradition first started by athletes, but developed fully by Hellenistic philosophers and other religious groups that found separation beneficial to their success in reaching disciplinary goals. Monastic descriptions of the desert, their settlements, and how they selected locations for their communities reveal the complexity of ascetical spatial beliefs. The efficacy of the landscape for success in monitoring and maintaining progress was essential for every monk. As we will see, how monastics explained the value of the desert location would take on unique qualities as monastic authors crafted a narrative of the generalized desert landscape to explain the spatial value of where they lived for a spiritual existence.

Displacing Demons in the Byzantine Desert

Monastic relocation into new areas was motivated by a shared belief that the goals of true monastic living could be best met in areas with other monks and away from societal distractions. To construct new physical environments, monastic communities articulated a message of the spiritual benefits for both monks and those who benefited from their prayers. Rather than seeking a quiet landscape, monks consciously sought battle and engagement with a noisy desert – a place that was occupied not by people, but by demons. Monastic authors explained why, in moving to the fringes of the occupied land, ascetics made a choice to occupy an already inhabited place populated by demons that claimed the desert as their domain.41 David Brakke’s analysis of monastic–demon encounters in the desert highlights the importance of the desertscape as an area of engagement not effectively available in the urban communities: “By striking out in the desert, however, the monachos or ‘single one’ radicalized the quest for simplicity of heart and likewise intensified an ambivalence about the multiplicity of human relationships that was deeply rooted in the late antique project of self-cultivation and particularly acute for Egyptian villagers of this period.”42 Monastic sites were arenas for intense spiritual activity. The battlefield imagery of the ascetic life occurs frequently in the descriptions of monks as warriors and as soldiers of Christ.43 The Sayings of the Desert Fathers offer numerous examples of this theme, best expressed by Poemen: “If I am in a place where there are enemies, I become a soldier.”44 The theme of military combat and occupation was an essential characteristic of what it would mean to embrace ascetic practices.

The Coptic Life of Phib incorporates much of the topographical language found in Late Antique documentary sources.45 The hagiographer Papohe writes: “After all these things, we went to a mountain (toou) of the desert (daie) opposite a village (time) called Tahrouj. We found some holes in the rock (petra) there and made some small dwellings (manšōpe) and stayed in them and lived the monastic life with numerous ascetic practices.”46 Despite the general nature of the terms, the steps for establishing a monastic settlement are clearly laid out and reflect Old Testament themes that were used again and again in the accounts of many monastic communities throughout the Byzantine Near East (Heb. 11:38). The desert “was a topos overlaid by a plethora of other topoi” that could be used by monastic authors to “articulate a new type of Christianity” that allowed for a Christian conquest of the landscape.47 The landscape would then be settled and used for a new purpose.

Only monks were adequately prepared to see the demons that resided in the desert and defeat them, for the “air which is spread out between heaven and earth is so thick with spirits ... For no fleshly weariness or domestic activity or concern for daily bread ever makes them cease.”48 Since ordinary humans were not emotionally or spiritually prepared to bear the sight of demons, it was the responsibility of ascetics to render the demons ineffective. John Chrysostom vividly represents this belief in the bravery and spiritual power of a monk in A Comparison between a King and a Monk: “The king alleviates poverty ... but the monk by his prayers will set free souls who are tyrannized by demons ... For prayer is to a monk what a sword is to a hunter. In fact, a sword is not so fearsome to the wolves as the prayers of the just are to the demons.”49 Chrysostom’s analogy of the monk to a hunter provides context for Poemen’s statement that monks become spiritual swords used in battle. Monastics moved into demon-inhabited lands in order to provoke a spiritual confrontation, thereby forcing demons to concede territory to the monks. The villages “depend[ed] on the prayers of these monks as if on God himself,” for the monastic settlements provided a protective barrier around the villages.50

Early monastic literature is clear that monastic settlements transformed the topography of Egypt both physically and spiritually. Monastic settlements adopted features that architecturally resembled clouds of earthly angels: “There is no town not surrounded by hermitages as if by walls.”51 In addition to monastic sites located near the towns, nonmonastics were aware of other settlements in remote places and in desert caves. Mindful of the comparisons between those living in remote locations and those in the immediate vicinity of the towns, the author of the History of the Monks in Egypt states that “those living near towns or villages ma[d]e equal efforts, though evil troubles them on every side, in case they should be considered inferior to their remoter brethren.”52 Both groups of ascetics were vital for establishing the proper balance in the world.

The reclamation of the desert for habitation is a powerful image first introduced by Athanasius (296–373) in his Life of Antony.53 For Athanasius, an urban bishop living in Alexandria, the movement of men into the fringes of the inhabited land in the fourth century reflected a conscious choice to establish a heavenly city dedicated to God: “[Antony] persuaded many to choose the monastic life. And so monastic dwellings (monasteria) came into being in the mountains and the desert (eremia) was made a city by monks: having left their homes, they registered themselves for citizenship in heaven.”54 The actual landscapes that Antony moved through were of little importance to Athanasius, for “[a]lthough he differentiated between the ‘outer’ and the ‘inner’ desert, this apparent dichotomy seems to refer only to basic geographical facts of the Eastern Desert, which the Alexandrian bishop did not translate into any essential difference in how these landscapes out to be understood.”55

A later fifth-century Syrian text, On Hermits and Desert Dwellers, provides a salient description of how monastic settlement of the desert transformed the very nature of the space: “The desert, frightful in its desolation, became a city of deliverance for them, where the harps resound, and where they are preserved from harm. Desolation fled from the desert, for sons of the kingdom dwell there; it became like a great city with the sound of psalmody from their mouths.”56 The physical nature and qualities of the desert were altered by the presence of the monks and their activities. The desert was no longer the space of punishment and the realm of demons – it was a landscape overrun by monks, conquering the demons and creating a pure landscape filled with athletes of Christ.

Monks Civilizing the Deserted Places of Late Antique Egypt

Narratives of relocation and settlement figure prominently in hagiographies and other forms of Egyptian monastic literature. The stories present carefully crafted accounts explaining why the founder of a community moved where he did and what incidents propelled his desire to seek out a desert place. But are these sources reliable historical accounts? Despite efforts to examine the redaction of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers in earlier generations for the kernels of historical events, most scholars are convinced that we can find little of the “Desert Fathers of history” and are instead looking at the “Desert Fathers of fiction.”57 In the Sayings, initially composed in the fifth century in Palestine and based upon oral transmissions of earlier stories, we can observe how a mindscape of Egyptian monasticism emerged. A few of the Sayings refer to monastic buildings, the monks living within the landscape, and the importance of desert living. Certainly, details of those living in remote areas are extremely difficult to reconstruct except from passing references to individuals who reside in the more remote inner desert for short periods of time. In looking at the foundation narratives, we learn how monks were taught to regard the environment, their participation in a legacy of their founder, and the importance of God as a navigator to suitable locations for monastic living.

Wadi al-Natrun and Kellia are home to two of the most famous locations for the loose confederation of Desert Fathers. Known more for their individuality and independence as expressed in the Sayings, the two locations represent the essential founding of monastic life in northern Egypt. In Upper Egypt, Pachomius founded the first enclosed and self-defined communal monastery, koinonion, at Tabennesi. His foundation narratives, pieced together from the various later Lives and a handful of letters, provide an excellent comparison to the foundation stories for monastic communities in the north. Lastly, the sites of Bawit, in Middle Egypt, and Sohag, in Upper Egypt, are examples of sites with complex settlement plans and communities not well known outside of Egypt. Unlike the founders of the sites of Wadi al-Natrun, Kellia, and Tabennesi, who were revered in the broader Mediterranean monastic world, the founders associated with Bawit and Sohag had only a very minor impact on the exported history of Egyptian monasticism. The story of Apollo makes only a small appearance in the History of the Monks in Egypt, and yet the archaeological remains of his community at Bawit blossom into a massive monastic town and the monks participated in several monastic and lay economic networks. In the case of Shenoute, neither he nor his monastic federation is mentioned at all in the travelogues or histories recounting the birth and development of early Egyptian monasticism. Thus, we see a significant gap in the overall narrative of Egyptian monasticism. And, this is exactly the uneven portrait of Egyptian monasticism that has been recycled, retold, and codified as the mythology of Egyptian monasticism, one based on Delta monasticism and only select encounters with Upper Egyptian monasticism through the accounts of Pachomius.58 A strong possible reason for this lacuna is that Apollo and Shenoute were not necessarily the founding monastic fathers for these sites, but later became honorific founders in the generations that succeeded them. Therefore, the foundation narratives did not circulate outside of Egypt. Taken together, the five sites illustrate how monastic authors crafted a generalized monastic landscape that overshadowed the actual landscape of connected monastic communities.

The Desert of Macarius in Sketis

Wadi al-Natrun was one of three areas in the northwest Delta to quickly earn an international reputation as the center for the monastic movement. Travelers such as Evagrius, John Cassian, and Palladius provide the major portraits of this desert as they traveled to Sketis and Kellia, often becoming temporary residents.59 Palladius describes the monastic landscape as including a variety of locations: “I visited many cities and very many villages, every cave and all the desert dwellings of monks.”60 Since he traveled in both the Egyptian and Libyan deserts and then visited monks in Upper Egypt, Mesopotamia, Palestine, Syria, Rome, and Campania, Palladius offers a comparative assessment of the Egyptian desertscape as he recounts it for his reader, Bishop Lausus.61 Palladius traveled to Egypt and lived at Kellia with Evagrius, before the latter’s death in 399. When John Cassian described Egypt and the settlements of the monks, he invited his listeners to “bear in mind the character of the country in which they dwelt, how they lived in a vast desert.”62 As a native of Scythia, Cassian placed the unusual landscape at the center of monastic training for his community that he founded in southern Gaul and highlighted the need for isolation in a place where monks are single-minded in their spiritual pursuits. Thus, the travelogues function not as naturalist accounts but as didactic treatises for authors and their audiences, who did not have first-hand knowledge of the landscape. While the desert became a central component of monasticism throughout the Mediterranean, descriptions about the Egyptian landscape, monastic settlements, and the records of foundations were embedded in larger themes to offer spiritual edification for contemporary communities.63

The importance of Sketis as a place for monastic training was both physically and rhetorically constructed through the works of visitors to the communities and later Lives written about the monks who lived in Wadi al-Natrun. The physical space of Wadi al-Natrun with its salt lakes and the importance of the desert for both physical and mental challenges provided authors with rich imagery to build a myth of the monastic desert. Wadi al-Natrun was the center of a healthy salt trade, as the materials gathered there were used in the millennia-old practice of mummification (see Fig. 34).64 The numerous salt lakes span a length of 30 kilometers in the Western Desert. Of this trajectory, an area of roughly 8,400 hectares was modified in some form for monastic habitation, with pockets of dense habitation in at least four areas with settlements ranging from 160 to 250 hectares.65 The belief in the efficacy of Sketis for correct teaching and monastic living was a powerful tradition that led to the rapid mythologizing of the desert.66 Early visitors, such as Palladius and John Cassian, referred to the area as Sketis (Coptic Shihīt), but it was equally known as the “Desert of St. Macarius,” reflecting the importance of its first and most famous inhabitant and monastic founder.67

34. Salt accumulation by one of the shores of a lake in Wadi al-Natrun, Egypt.

How did Sketis become the “Desert of Macarius?” This is a difficult story to extract from the hagiographical sources we have, but is necessary, as the attribution of a famous monastic founder to one’s community and landscape provided a sense of identity and unity for later authors.68 David Brakke honestly states the vexing nature of the historical study of early monasticism is that “many of our literary sources are, to be blunt, not true ... few literary works come directly from Egyptian monks of the fourth and early fifth centuries.”69 Therefore, reconstructing the story of Macarius as the founder of monasticism in Wadi al-Natrun truly is an effort in reconstructing a mosaic from bits from later traditions, possible oral histories, and much later community perceptions about Macarius. Despite this distance from the historical Macarius, it is invaluable to consider the accounts that were told about him. For “fiction may tell us as much about early monastic culture as the papyri and archaeological remains that more positivist historians value so highly.”70 The exploration of how the desert of Sketis became “Macarius’s Desert” provides a path of inquiry that is just as informative for reconstructing perceptions of the landscape as reading letters and contracts from Late Antique monastics. In pulling together threads from a wide range of literary sources, and in one case from the letters and sermons of one founder, Shenoute, we can observe the construction of a monastic landscape through the eyes of later generations. It is a landscape that requires good stories and memorable individuals, but in the end, those accounts are not historical truths, but historical stories that lend authority to existing communities.

Macarius of Egypt, also known as Macarius the Great and a contemporary of Amoun of Nitria, was the first monk to build his monastic residence in Sketis. His biographies in the Sayings and various Coptic sources differ as to whether he was married or not. In the Sayings, Macarius lived a monastic life in a cell near a village.71 The villagers, after learning of his piety, desired to make him their priest. Macarius effectively rejected their efforts by moving to another place where he could live in peace, this time living with another ascetic. Then a woman, who had become pregnant, leveled accusations of impropriety against him. Once he was found innocent of fathering the child, he moved yet again farther away from the town. With this final encounter, Macarius went to the desert of Sketis and built his own cell.

The horizontal movement from the populated to the uninhabited land reflects a vertical movement in terms of spiritual achievement and maturity. In the early fifth century, Palladius recounts his stories of Macarius after his own sojourn through the monastic deserts of Egypt and several years living as a monk at Kellia.72 During his lifetime, Macarius had at least two residences in Sketis and lived there for sixty years.73 One was a cell where he resided with two other monks, and the second was a cave. Macarius could retreat to the cave, which was connected to his cell by a 90-meter tunnel running underground.74 While Macarius the Great is an important figure for the section on the monks of Sketis, the place is not yet equated with him or his first settlement. For Palladius, Sketis is the “great desert” or the “great interior desert,” and therefore is known more for its physical size and its interiority, in contrast to the other monastic settlements he visited.75 John Cassian, similarly, associates Sketis with greatness, for it is home to the “most celebrated fathers of monasticism, the ultimate in excellence” and Macarius has only a limited appearance in the stories that Cassian tells his fellow monks.76

The Coptic Life of Macarius, which follows the biography of the Lausiac History, details how Macarius shared his ascetic life with two disciples, one who lived with him and another who lived in a cell nearby.77 The Coptic version also identifies Sketis as the “great desert,” which “leads each person into feast of asceticism, whether he wants it or not.”78 To be sure, this model of apprenticeship departs from the more communal house model of several individuals living under the guidance of a house father that will be common in the Pachomian and Shenoutean communities in Upper Egypt, or the later development of dwelling places in Sketis.79 In all the descriptions of the landscape, the desert is described as the land of monks, and we hear little about who was the “first,” except for the short entry on Macarius of Alexandria in the History of the Monks in Egypt in which he, and not Macarius the Great, is identified as “the first to build a hermitage in Sketis. This place is a waste land laying at a distance of a day’s and night’s journey from Nitria through the desert.”80 The tradition of Macarius as the first inhabitant is mentioned only in passing in the Sayings, linked to Macarius the Great when he is described as “the only one living as an anchorite, but lower down there was another desert with several brothers.”81

By the eighth century, a slightly different story is detailed in the Coptic Life of Saint Macarius of Scetis that firmly places Macarius as the spiritual founder of desert monasticism in Wadi al-Natrun.82 In this vita, Macarius married against his wishes and adopted a spiritual marriage, always maintaining his purity. His only avenue to escape his marriage was to participate in the salt-mining trade in Wadi al-Natrun.83 The topography mentions mountains of natron and the routes workmen used to move their camels back and forth between the salt areas and the villages. During one of his trips to the lakes, Macarius spent the night on an outcrop with other salt traders. While there, he had a dream or vision that would provide the basis for his eventual move to the desert.84 The passage provides a vivid description of the landscape and then offers a gendered image of Macarius as a nursing mother for his spiritual children.

Later that night he found himself dreaming; a man was standing above him in a garment that cast forth lighting and was multicolored and striped, and he spoke to him, saying:

“Get up and survey this rock on both sides and this valley running down the middle. See that you understand what you see!” “And when I looked,” he [Macarius] said, “I said to the person who had spoken to me, ‘I don’t see anything except the beginning of the wadi to the west of the valley and also the mountain surround[ing] the valley; I see it.’ And he said to me, “Thus says God: ‘This land I will give to you. You shall dwell in it and blossom and your fruits shall increase and your seed shall multiply [Gen 12:7] and you shall bear multitudes of spiritual children and rulers who will suckle at your breasts; they will be made rulers over the peoples and your root shall be established upon the rock.85

In this first identification of Sketis as Macarius’s land, God bestows the land and the promise of generations of children as a gift. The vision is a direct parallel to the promise made to Abram when he surveyed the land held by the Canaanites. Macarius does not, however, move into the desert of Sketis, but rather resides with other ascetics in cells on the edges of different towns. Eventually he adopts a cell of his own and receives a second visitation, this time from a cherub, who rebukes him for failing to respond to his earlier vision to relocate to the desert.86

After prayer, Macarius was ready, “leaving behind everything in his cell” as a sign of his commitment to his new mission in the desert.87 The walk took two days, which would roughly be between 48 and 95 kilometers, depending on the heat and the difficulty of the paths taken into the desert.88 At this point the cherub asked Macarius to choose the location he would like to settle in, but he admitted that he did not recognize anything in the area. The cherub said: “See, the place lies before you; but examine it and take possession of a good site. Only, be on the watch for evil spirits and their evil ambushes.”89 He selected a place at “the beginning of the wadi near the site where natron was extracted.”90 In deciding to be close to the salt mines, he also made a conscious choice to be near others, the workmen and guards at the salt lakes, which would later prove to be detrimental to his solitude.

Forced to find a quieter location because of the noise of the salt mine industry, Macarius moved again – this time to a mountain cave. He went now into the desert and selected a natural rock formation for carving two caves. One served for his daily needs for plaiting baskets and the other was purely for liturgical use. His presence in the desert caused the demons to complain restlessly about his occupation of their territory. They voiced their fears that more monks might join him: “Shall we allow this man to stay here and allow the desert places on account of him to become a port and harbor for everyone in danger, and especially to become a city like heaven for those who hope for eternal life? If we allow him to remain here, multitudes will gather around him and the desert places will not be under our power.”91 The conquest of the desert places surfaces again as a central theme in the stories of monastic occupation of the landscape. The deepest fear of the demons is quickly realized as multitudes start to gather around Macarius in the desert.

The Life describes how Macarius taught the monks how to build their own dwellings. They carved caves into the rock and also used palm branches, trunks, and stalks “from the wadi” to finish off the dwellings and create a good shelter.92 At this point the community was made up of individual cave dwellings and the monks still fetched water from the wadi, as Macarius “had not yet dug cisterns.”93 Practically speaking, the community’s building program needed to expand to accommodate both daily and spiritual needs of the residents. They built a small church together, then dug wells, and finally they needed larger dwellings.94 As a sign of God’s pleasure with Macarius, a cherub told the saint: “The Lord has come to dwell in this place on account of you.”95 The fact that God now dwells in the desert is directly linked to Macarius’s success in forcing the demons out of the land.

His achievements prepare him for his final relocation to an even more important area of the wadi that Macarius will bring to perfection. The Life offers yet another description of the land Macarius is directed to occupy:

The cherub led him and took him atop the rock at the southern part of the wadi to the west of the cistern at the top of the valley and said to him, “Begin by making yourself a dwelling here and build a church, for a large number of people will live here after a while.” And so he lived there to the day of his death, and after his death they called that place “Abba Macarius” because he finished his life there.96

Macarius’s story of movement into the desert reflects similar patterns of movements for other monks. Many began by living alone in their town or village; some are even married and secretly agreed to a “spiritual marriage” with their wives in order to practice the ascetic life. When tensions arose that threaten the privacy of the private ascetic life, many sought out a more experienced monk to serve as a mentor and guide.

In the Coptic Odes to Saints of Scetis, Macarius is described as “the great net who drew everyone into the Way of God, and put upon them the holy habit, teaching them to dwell solitary in holes of the ground.”97 The reference to “holes in the ground” invokes the language of the faithful prophets, who resided in the harsh landscape of the desert (Heb. 11:38). Sketis evolved from the residence of a solitary monastic to become an entire region, home to four well-known and still existing monastic communities. Christian Arabic authors often referenced the region as Mizān al-qulūb, meaning the place of the “Weighing of Hearts,” a literal Arabic rendering of the Coptic Shi-hēt, as a reference to the spiritual challenges one faced while in the region. In the bulk of the Arabic literature of Christians and Muslims, however, the region is identified as Wadi al-Natrun, the most common designation today, or as Wadi Habīb. Medieval authors, such as Abu al-Makarim and al-Maqrīzī, attribute Macarius as the founder of the monastic community in Wadi al-Natrun.98 Abu al-Makarim reports that Macarius was directed by Antony to move to Wadi al-Natrun and then many monks took up residence in Wadi al-Natrun because of Macarius’s “noble deeds.” By the fifteenth century a listing of monasteries in al-Maqrīzī’s Khitat includes a description of Wadi al-Natrun and he presents an extensive etymology. Al-Maqrīzī listed eighty-six monasteries in the desert.99 He describes Wadi Habib as being known by a variety of names such as Wadi al-Naturn, “Desert of shihāt,” “Desert of askīt,” and Mizān al-qulūb. His settlement history recounts how the monasteries dwindled down to seven in a land where “sandy flats alternate with salt-marshes, waterless deserts, and dangerous rocks.”100 The great desert of Macarius had numerous monasteries “in ruins.”101 The ruins would remain until the visits of Hugh Evelyn White, who also remarked on the ubiquitous nature of the “ruins” in the 1920s.

The Greek, Coptic, Syriac, and Arabic traditions relating to the settlement of Wadi al-Natrun share and enhance the importance of its salt as a purifying agent in monastic living and Macarius as a builder. The salt of Wadi al-Natrun was a “spiritual salt” and was “an explicit contrast with the salt of death” found in the inhabited world.102 The salt also became a physical representation of the theological importance of Wadi al-Natrun in the monastic imagination. By inhabiting the desert, the monks tamed the wilderness.103 They caused the salted land to be fertile again, both physically and socially, with athletes of God. In the end, all the accounts about Macarius speak to the importance of displacing demons through settlement and occupation.

The Quiet Retreat of Amoun at Kellia

Traveling nearly forty years after the founding of Nitria and Kellia, the first long-term visitors and foreign residents at the two sites wrote accounts that were focused more on inspiring their readers or patrons than on offering an accurate recounting of the physical landscape or the monastic architecture that they lived in. Palladius lived for nine years at Kellia and Evagrius for sixteen; yet, neither writer is compelled to tell us much about the actual landscape, as they, like other monastic writers, are engaged in writing literature to inspire and encourage other monastics about how to live the ascetic life. Therefore, the story of Kellia’s foundation needs to be pieced together from fragments of diverse monastic sources with very different objectives than recounting the life of one particular founder.

The foundation story of Kellia is linked directly with the older foundation story for Mount Nitria.104 Both sites were located further north of Sketis and are often described in Late Antique travelogues in terms of distance relative to or from Alexandria, the closest urban center to the two settlements.105 Unlike Sketis, where a sustained monastic community preserved and expanded earlier written traditions throughout the late medieval period, the communities at Nitria and Kellia were abandoned by the eighth or ninth century, resulting in fewer sources that document how monks reproduced their community’s history. Therefore, the accounts of Palladius, Evagrius, John Cassian, and the anonymous author of the History of the Monks in Egypt provide an early record of oral traditions circulating within Egypt before the written form of the later fifth-century Sayings of the Desert Fathers.

The story begins with a man named Amoun, who left his wife after eighteen years to live in the Delta at the site of Nitria. When Palladius ventured to Nitria, it was a mountain located seventy miles from Lake Mareotis and inhabited by more than 5,000 monks, and it was Arsisius, a resident, who told him the story of the community’s origins.106 Having the blessing of his wife, Amoun set out to the “inner part” of the mountain of Nitira, “for there were no monasteries there yet – and he made himself two round cells.”107 The Coptic Life of Antony includes a chapter on Amoun, where he is identified as one who lived at the Toou of Nitria, and his death was known by Antony, who saw his soul ascend.108 That story is the beginning of the account in the History of the Monks in Egypt for Amoun.109 The area of Nitria, like Sketis, was associated with the mining of niter (potassium nitrate), a substance used in cleaning but not the same as natron.110 Like Macarius, Amoun sought out the remote settlements that others had inhabited, which illustrates he knew men were living in the fringes. Here in the flat desert, far from urban centers and rugged limestone cliffs, Amoun gained a following and encouraged his male colleagues to adopt both solitary and communal dwellings in the Delta.111 The story of Kellia’s founding is not found in the sayings attributed to Amoun, but rather in the stories about Antony, reflecting his greater significance as being a companion in the establishment of the settlement along with Amoun.

In the Sayings attributed to Antony we learn that he visited Amoun one day and they discussed a growing concern surfacing at Mount Nitria – the mountain was too crowded and too noisy.112 Amoun felt restless because his fellow monastics were arguing about how to live and where to live in great silence. He asked Antony: “How far from Nitria are these brothers to go before building their new dwellings?”113 The two monks set out after breakfast and walked into the desert until the sun set. They covered roughly 19 kilometers that day.114 As a sign that their relocation was sanctioned by God, the two monks were protected from the intensity of the sun that day. Once they had stopped for the night, they planted a cross to mark the location.115 Antony said that others would recognize the cross as a sign and would know that this would be a peaceful place to live, if they wished to live in such a manner.116 It was here that Amoun began the community later known to Evagrius, Palladius, and John Cassian (see Fig. 14).

The distance between Kellia and Nitria was enough for a day’s walk between the two communities, but also significant enough that there was a separation between the two groups. The location was in the inner desert, removed farther from paths of activity than Mount Nitria, and in a deserted area.117 The settlement would become known as a monastic retreat from more bustling sites, for to live here was “to live a more remote life, stripped down to the bare rudiments.”118 The remarkable nature of Kellia is that the settlement grew from Amoun’s desire to find solitude and to escape the crowds, but it is a later story, one that emerges perhaps in response to the growing popularity of monastic tourism in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. In the end, the site superseded that of Nitria and literally became the city in the desert that Athanasius hoped would one day develop. Archaeological evidence exists at the site for definite settlements in the fifth century, but the earliest levels do not correspond with the time of Amoun, Evagrius, or Palladius. The site’s eventual decline in the late eighth and ninth centuries would also mean a decline in monastic literature about the settlement as the built community became a part of the desert topography. Both Kellia and Sketis, as representatives of desert monasticism in Lower Egypt, convey how monastic literature was shaped within Egypt and in non-Egyptian sources. For those who transmitted the accounts of Egypt’s northern desert monasteries, the stories of foundations were of lesser importance than the lessons to be learned in hearing the words of the Desert Fathers. And despite the importance of Kellia as a location welcoming to foreign, monastic guests, it was other monastic sites, such as Sketis, that seemed to capture the imagination of monastic authors more than the location of the “Cells,” the colloquial name for the site. For Sketis, where monasticism still thrives in Wadi al-Natrun, we have a rich history to consult for later medieval perceptions of Delta monasticism. But by the ninth century, Kellia had vanished from the early medieval geography of monastic Egypt, not to be found again until 1964.

Pachomius’s Community of Village Monasteries

After the Desert Fathers of Lower Egypt, the most often referenced communities of monks of Egypt were those associated with Pachomius (292–346) and his koinonia in Upper Egypt.119 His place in the history of Egyptian monasticism is as central as Antony’s. Both Antony and Pachomius hold positions of authority more through the retelling of their ascetic lives as recounted and recycled by later authors and biographers than by what they actually built. James Goehring explains the difficulties surrounding Pachomius’s place as a founder:

The picture of Pachomius’s originality is, however, literary rather than historical ... The Vita makes clear through these stories that Pachomius’s innovation had little to do with the coenobitic institution itself. It was rather the organizational principle of a koinonia or system of affiliated coenobitic monasteries and the development of a monastic rule that are credited to Pachomius... The theory of a Pachomian origin of coenobitic monasticism must thus be discarded ... The vast number of monasteries in Egypt in the late Byzantine era simply cannot be traced to a single point of origin.120

Philip Rousseau urges for a similar corrective in the reading of monastic foundations by asserting “the formal establishment of a communal way of life did not represent a sudden lurch in a new direction.”121 For the discussion here, the story of Pachomius’s monastic foundations provides a useful case study for assessing how monastic communities looked at the desert and constructed the story of monastic settlement in Upper Egypt. But, like the narratives of the northern Delta deserts, the sources we have are deeply layered in generations of authors and redactors, consciously constructing a life of Pachomius. The authors were motivated to create history and thereby ensure the community’s identity.122

Goehring has written extensively about the nature of village monasticism as a phenomenon that is more significant than scholars once believed: “Properly understood, Pachomian monasticism is not a product of the desert, but a form of village asceticism.”123 The repositioning of Pachomius out of the desert and into the cultivated land is an important component of nuancing the history of Egyptian monasticism. Do the accounts of Pachomius’s reoccupation of the village share any themes with the famous accounts of the communities in the north? And in what ways do the descriptions provide a regional, Upper Egyptian story of monastic settlements?

Pachomius’s story is unique in comparison to that at the other four sites discussed in this chapter, as we do not have any substantive archaeological remains for any of the six monasteries that he built or the three other monasteries that later joined his koinonia. Given the rich literary sources surrounding Pachomius and his importance in monastic history both in Egypt and in the wider Mediterranean monastic world, the lack of physical evidence is an unfortunate lacuna in the archaeology of monastic Egypt. Physical indications of monastic settlements and the presence of monastic travelers are certainly evident in the form of Christian graffiti and dipinti in the towns and villages, in such areas as Wadi Sheikh Ali, Abydos, Naqada, and even around Pbow, where Pachomius lived.124 The only probable physical remains associated with Pachomius are linked to a small church at Faw al-Qibli, ancient Pbow, which was excavated in the late 1970s and 1980s.125 Working in the late 1960s, Fernand Debono interpreted some mud brick walls at Pbow as possible monastic structures, but his excavation areas have been lost and subsequent explorations in the area by Bastiaan Van Elderen, and later Peter Grossmann, did not locate Debono’s excavation areas.126 Therefore, we do not have any extensive monastic remains available for archaeological study that would allow us to examine the physical realities in comparison with the monastic literature associated with Pachomius.

Let’s begin by looking at the numerous stories of Pachomius’s life to learn how he came to start a monastic movement that embraced the fringes but not the desert. The Life of Pachomius is preserved in several manuscripts in Coptic (Boharic and Sahidic), Greek, and Arabic.127 The Boharic Life (also called the Great Coptic Life of Our Father Pachomius) provides the richest description of Pachomius’s movements, building methods, and the settlements. On his release from conscription, Pachomius set out to live in service to others, but he was not yet a monk, according to the Boharic Life. He arrived at his first “deserted village” called Šeneset (Gk. Chenoboskion), which had only a “few inhabitants.”128 He walked down to a standing temple called Pmampesterposen, “the place of the baking of the bricks.”129 God directed Pachomius to “settle down here” and he planted both a vegetable garden and palm trees so that he could provide for himself and serve some villagers with his food.130 The location was “scorched by the intensity of the heat,” but it was not entirely abandoned, as other Christians lived there, and he was baptized in a local church.131 As a result of Pachomius’s generosity and charismatic Christian example, the population in the town began to increase, and the burden of community service caused Pachomius to spend a lot of time teaching others.132 After a plague ravaged the population and Pachomius tended to the sick and dying, he decided that his physical ministry was not suitable and he needed greater solitude. It was during this period of searching that Pachomius encountered Apa Palamon, a monk who lived on the outskirts of the village. Pachomius decided he would rather live with Palamon and away from the needs of the villagers. Before his departure, Pachomius entrusted the responsibility for his garden and date palm trees to an old monk. Despite Palamon’s efforts to send Pachomius away, Pachomius convinced Palamon of his will to pursue the ascetic life and trained with the older monk for three months.133

The location of Palamon’s dwelling is not clear in the Lives except that it is just beyond the village of Šeneset and near or on a mountain of the desert. Palamon was considered a father and teacher for a collection of other like-minded monastics who resided in the mountain; but only Pachomius lived with Palamon.134 Palamon and Pachomius trained their bodies by carrying baskets of sand up and down the mountain.135 Pachomius, being younger than Palamon, also ventured into the acacia forest and the “far desert” to practice his askesis.136 In addition to the natural environment, Pachomius also used the abandoned tombs “filled with dead [bodies]” for prayer; he was so dedicated to this practice that the ground beneath him in the tomb would be muddy because of his perspiration.137 Others monks resided nearby on the mountain, but only Pachomius appears to have traversed the desertscape. After Palamon experienced a severe illness, Pachomius took a further step to seek independence from Palamon and pursue his own path, but away from others at Šeneset. He left the mountain, crossed the desert, and arrived at the large acacia forest by the Nile: “Led by the spirit, he covered a distance of some ten miles and came to a desert village on the river’s shore called Tabennesi.”138 It was here that Pachomius was instructed by a heavenly voice to reside.

A description of the desert on the east bank of the Nile tells more about Pachomius’s ability to withstand difficulties than about the specific topography: “Around that mountain was a desert full of thorns where he was frequently sent to gather and carry wood. And since he was barefoot, he was sorely troubled for some time by the thorns which fixed themselves to his feet.”139 On another walk through the desert, he ended up near the deserted village of Tabennesi (Nag’ al-Sabriyat). Here he heard from God while in prayer: “Stay here and build a monastery; for many will come to you to become monks.”140 Pachomius agrees to expand his dwelling in a “deserted village” to a monastery.141 On his return to Palamon, Pachomius shared his account with his spiritual father. Together they built a cell at Tabennesi for Pachomius, and Palamon affirmed his ties to Pachomius as a “true son” so that they would visit each other after Pachomius remained in Tabennesi. The importance of mutual visitation was a tangible component of their relationship.142 The fact that the site is called a “deserted village” in all accounts, including the Arabic Life, suggests that Pachomius and other monks like him had found standing buildings or ruins, at the very least, and that the spaces could be repaired for habitation.143 The ease of adding and repairing a mud brick structure would have made the processes relatively quick.

Soon afterwards Palamon died, and Pachomius returned to Šeneset to bury his teacher.144 It is at this point that Pachomius was visited by his biological brother, who went north on learning of Palamon’s death to live with Pachomius. The Sahidic Life records in an abbreviated form a significant disagreement between the two brothers, and in the Boharic Life we learn that the cause stems from a difference of opinion regarding whether to expand their monastic settlement and invite others to join them. It is a rich passage in early monastic hagiography about monastic construction and attitudes toward the built environment at Tabennesi: “One day, as they were building a part of their dwelling, Pachomius wanted to extend it because of the crowds that would come to him, but John’s mind was that they should stay alone. When Pachomius saw that John was spoiling the wall they were building, he said to him, ‘Stop being foolish!’”145 The tension between the two brothers is expressed in the building itself and in how well the walls were made for the expansion. John’s deliberate sabotage of the built wall reflected his displeasure with changing the two-person dwelling into one that would accommodate more monks and thus expand their settlement.

In the Sahidic Life, Pachomius’s response to the difference of opinion involves an unusual account of a brick used for prayer. It demonstrates the use of materials and their response to the spiritual devotion of Pachomius. Apparently he stood on a mud brick for discomfort in an underground cell in order to deter sleepiness. After a night of fervent prayer, the brick had dissolved because of the great volume of Pachomius’s perspiration. On a second night of prayer, necessitated by another bout of conflict with his brother, Pachomius prayed and perspired so much that the brick did not just break up but actually became a muddy pile.146 This story reveals one of the rare instances of construction materials, such as mud bricks, being used in ascetic practice.147 His prayers were effective, for many individuals began to visit the brothers, thereby proving Pachomius to be correct in his desire for expansion.

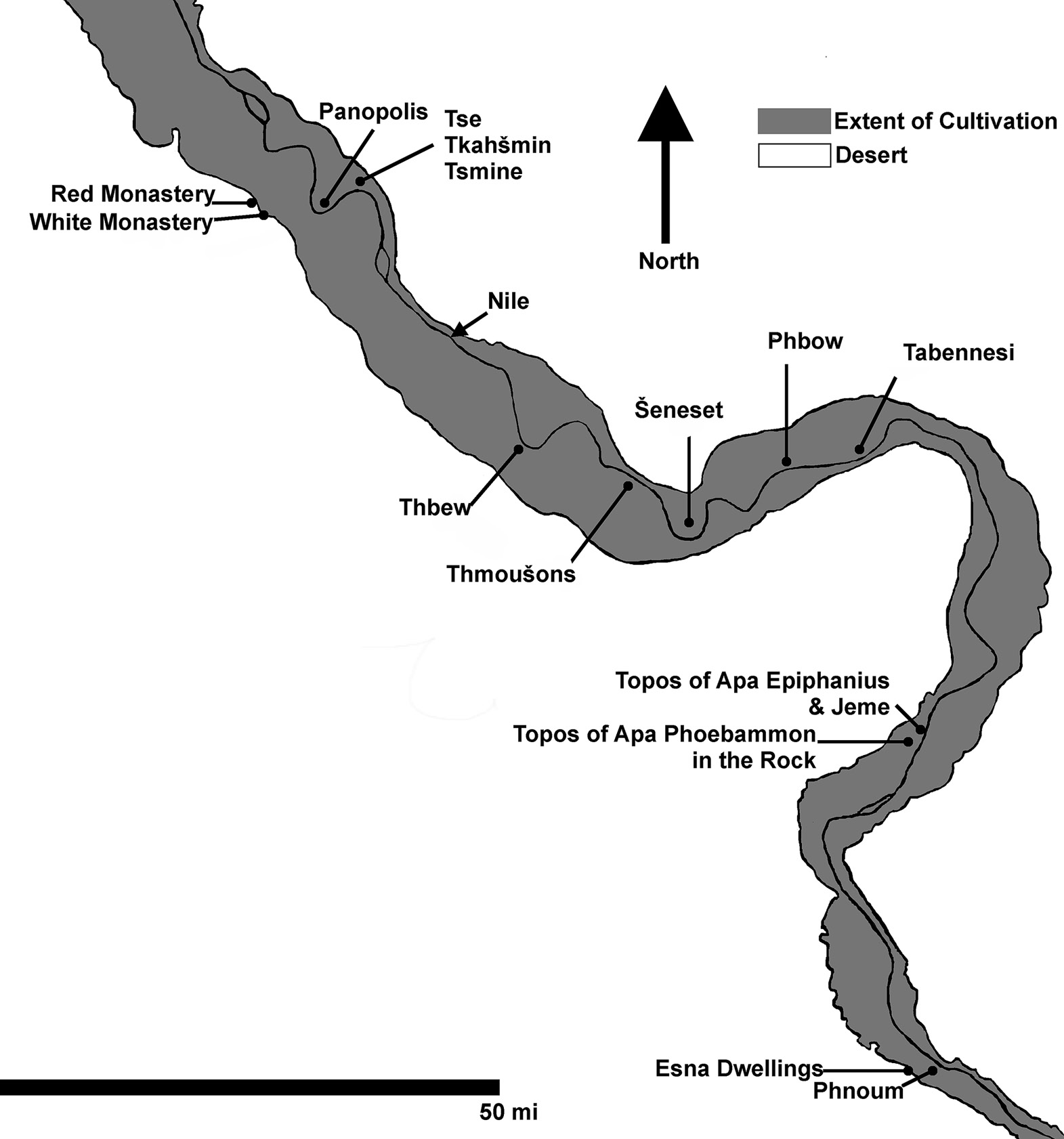

Individuals from the surrounding villages started to join Pachomius and build dwellings for themselves. Pachomius’s fame was not tied to just Tabennesi, and within a span of a few years Pachomius ruled over nine monastic settlements spanning a distance of more than 220 kilometers of the Nile, from Panopolis to Latopolis. Pachomius’s network was one of governance and a shared monastic rule – the koinonia. The nine monasteries that formed this network, in order from north to south, were Tse, Tkahšmin, Tsmine, Tbew, Tmoušons, Šeneset, Pbow, Tabennesi, and Phnoum. In addition to these, Pachomius also formed two communities for women, stemming from a desire to build a community where his sister could practice monasticism.148 Of the nine male communities, Pachomius and his brothers built six, sometimes only building a wall around existing structures. Unlike Macarius, whose authority extended only to those immediately living around him and his successors and did not cover the entirety of the 30-km-long stretch of the natron lakes, Pachomius’s leadership spanned an extensive area of Upper Egypt. This does not mean he had jurisdiction over all the monastic communities that lay between and among the eleven communities. The accounts of those who elected to seek membership in Pachomius’s koinonia reveal the prevalence of other monastic communities in the region. Even if we look more conservatively at the concentration of the five male monasteries around Tabennesi, Pachomius was traveling in a 55,000-hectare district, often by boat.149 The fact of the matter is that the area Pachomius moved into was not entirely deserted and was already home to a variety of cities and villages along the Nile banks, associated with cultivated fields and easy access for river travel.

The account of how the nine men’s monasteries came to be part of the koinonia is a complex story of building and incorporation. Tabennesi was the first Pachomian community built in a deserted village, likely meaning an area with low population and some vacant buildings that Pachomius and others could repurpose (see Fig. 35).150 But then the population in Tabennesi started to increase; however, we are not told whether this is a natural increase in population after the plague or if Pachomius and his brothers were a point of attraction. He and his fellow monastics built a church for the lay community, and eventually even the monastic population increased enough that they needed their own sanctuary within the monastery. However, the “cramped” and “crowded” nature of Tabennesi forced Pachomius to pray for wisdom as to what he should do.151 For reasons we are not told, further expansion at Tabennesi seemed out of the question. God answered Pachomius’s request for guidance through a vision and provided a clear directive: “Go north to that deserted village lying downriver from you which is called Phbow (Pbow), and build there a monastery for yourself.”152 With this vision relating to the founding of Pbow, we have the first of the monasteries that formed Pachomius’ koinonia, as he was no longer the head of a single community, but the leader of a nascent federation.

35. Map detailing the possible location of Pachomian monastic establishments in relationship to other monastic sites in Upper Egypt.

Similar to Tabennesi, Pbow was a deserted village and presumably had some standing mud brick structures and possibly even a few inhabitants. In examining the foundation passages and how the Lives present the villages, Goehring raises the question as to the literary nature of the phrase “deserted village” and whether it is a conscious choice by the authors to describe an area that had experienced depopulation: “While the Pachomian accounts suggest a completely vacant village akin to the ghost towns of the old American West, it is possible that the label indicates nothing more than that a sufficient degree of vacancy and open space existed within the late antique villages to enable Pachomius to establish ascetic communities there.”153 At the very least, there was vacancy in the village so that Pachomius was not challenging village or town authorities by adding settlements to the area. The deserted nature of the village may, therefore, also imply it was deserted by administrative secular authority. There seems to have been some ecclesiastical authority over the village, because the Boharic Life states that when Pachomius built the “celebration room,” he needed the permission of the bishop in order to do so.154 Whatever the state of Pbow, Pachomius also built a wall for the monastery and houses for the monks. The third monastery added to the koinonia involved the addition of an already preexisting monastic community at Šeneset.155 Further north, and across the river on the west bank, Apa Jonas, the leader of the monastic community at Tmoušons, asked Pachomius for affiliation with the koinonia.156 With the addition of Šeneset and Tmoušons, Pachomius now had four monasteries in a 400-square-kilometer area under his leadership.

The second wave of expansion took Pachomius’s vision significantly further downriver, about 80 kilometers from Tmoušons to Tkahšmin, which is located near the city of Panopolis (Coptic Šmin).157 Although it is not described as a desert village, the brothers traveled down the Nile to the site to build the monastery and dwelling places (pl. mma shope) for the monks. On completion, the community was given the name Tse. The sixth settlement to join the koinonia was facilitated by a letter from Arios, a bishop from Šmin.158 The full participation of the brothers even included Pachomius, who carried the clay used for making the bricks on his back, just like the others.159 The story of this construction project takes on an interesting turn when a segment of the population in Šmin regarded Pachomius’s building activities as a threat and vandalized the construction site at night, “throw[ing] down what the brothers had built up during the day.”160 In the end, God instructed an angel to provide a protective barrier around the building site and wall with a ring of fire, protecting the site from further vandalism. The monastery of Tbew was the seventh monastery incorporated into the koinonia.161 Following the pattern of earlier existing monasteries that sought affiliation with Pachomius, Tbew was the last of the five core monasteries in the immediate 50-kilometer stretch of the Nile, running north from Tabennesi, to join the koinonia.

The last two monastic foundations are discussed in the Boharic Life, but only mentioned in passing in the Greek Life.162 Pachomius receives divine directives for the last two settlements at Tsmine, near Šmin, and Phnoum, near the mountain of Sne (Gk. Latopolis). These monasteries create the north boundary (Tsmine along with the monasteries at Šmin and Tse) and the south boundary of Pachomius’s administrative presence in Upper Egypt. Tsmine’s building program was similar to the others as he “finished it well, like all the other monasteries.”163 It seemed important enough that he transferred Petronios from Tbew to the region of Panopolis to supervise the three monasteries located there: Tsmine, Šmin, and Tse. All three had been built under Pachomius’s hand.

The building of the monastic community at Phnoum by the mountain of Sne, 150 kilometers upriver from Pbow, was extremely far away from the heart of the koinonia. A final vision directed Pachomius to go south and organize another monastery.164 The final building project was not without its problems. The author of the Boharic Life includes a brief report on the tensions between Pachomius and locals. In this case a bishop, who rightly may have seen Pachomius’s presence in his area as a challenge to his authority, organizes the protest. The erection of the monastic wall by Pachomius becomes a visual source of conflict for the inhabitants of Sne, who shared the same dislike for monastic construction as the inhabitants of Šmin. The passage demonstrates the symbolic power inherent in new boundary walls as a challenge to present authority in the region:

When he had begun building the wall of the monastery, the bishop of that diocese got a large crowd together; they set out and rushed at [Pachomius] to drive him out of the place. The man of God our father Pachomius withstood the danger until the Lord scattered them and they fled before his face. After that he built the monastery, a very large one, and finished it well, in full keeping with the rules of the eight other monasteries he had built.165

The final description of the ninth monastery states that Pachomius had in fact built all the others, when in reality the Lives clarify that he built only six of the nine. The other three became members either through self-election into the koinonia or by donation. The later conflicts in Šmin and Phnoum therefore highlight the sharp difference between Pachomius’s first monasteries built in the deserted villages where ecclesiastical authorities and local administration did not interfere with his efforts, perhaps owing to the lax attitude toward new building projects in Late Antique Egypt.

The foundation accounts of the village monasteries of the Pachomian koinonia provide a rich and variegated account of the many ways spaces became monastic outside of the desertscape. Despite the hagiographical tendency of these sources to commemorate Pachomius and his immediate successors, Theodore and Horsiesius, the stories provide several important components that reflect a generalized landscape of Upper Egypt. Pachomius was always commanded to build monasteries by God, and when other monastic communities desired his leadership, it was because their own leader recognized the benefits of the koinonia. The six monasteries Pachomius built included two sparsely populated villages (Tabennesi and Pbow), two cities (Šmin and Phnoum), and two areas located near the same city of Šmin (Tse and Tsmine). In the case of the three affiliated monasteries, two had very different origins: Šeneset was a loosely inhabited village like Tabennesi and Pbow, while Tbew was built on a wealthy family’s estate.

When comparing the Pachomian foundation narrative material, whose complex history includes purpose-built structures and the occupation of abandoned buildings and monasteries, with the material from Middle Egypt and the Great Desert of Sketis, two parallels appear. First, the literary traditions use visions and dreams as mechanisms for legitimizing the actions of founders and foreshadowing the success of their settlement choices. Pachomius had received the first indication of his future success on the night of his baptism with a dream. He was given a surrealist image of how God’s pleasure with him would be a blessing for those around him. As dew fell from heaven upon his head, it condensed in his right hand simultaneously, transforming into a honeycomb. This sweet sign of blessing and favor – his honeycombed right hand – fell to the ground and spread honey over the earth.166 His blessedness spreads throughout the land of Egypt and beyond.

Another similarity between the monastic narrative sources is the importance of the generalized landscape and its topography with the physical markers of the monastic settlements. The deserts, caves, mountains, forests, villages, and the Nile appear as real places for monastic living. Towers, dwellings, and walls mark the texts as signs of monastics laying claim to the land. As athletes and soldiers of Christ, monks could quickly build a mud brick structure or repair a wall, which was vandalized in the night, with the end goal of fulfilling God’s vision. If they were faithful in building, God would reside in the new locations and bless the community.

The one significant difference between the village monastic settlement narratives of Pachomius and the accounts of the desert dwellings is the importance of displacing demons through habitation. In the case of Sketis and the regions around Nitria and Kellia, the natural environment was certainly inhabited, but not by bishops, villagers, or administrative officials. While we know that miners were living in the Delta, the narratives present the only real threats in the deserts as nonhuman. Demons could hide in the desert, camouflaged by the caves, quarries, and mountains. The monastic settlement then forces demons to become beings without homes as the desert and its associated areas transform into heavenly realms of angels on earth.

Village monastic narratives do not dwell on demons and their locations because people already inhabited the villages they wished to live in. The dangers were different in village monasteries: monks refusing to follow the coenobitic rule, family members who continually visit, and even bishops who tear down walls. Pachomius and his followers carved out different spaces for themselves in the towns. They remodeled abandoned buildings as others remodeled quarries. In the end, building near others who did not share the monastic goal of the ascetic life could result in significant conflict, just like the conflict with demons in the desert. In all cases, the sources do not focus on the spatial configuration of the settlements, or how monastic buildings differed from nonmonastic structures.

Apollo Builds a Monastery for Phib in Bawit

The monastic settlement of Bawit, located 310 kilometers south of Wadi al-Natrun and 250 kilometers north of Tabennesi, is in the heart of Middle Egypt, and is the site of the Monastery of Apa Apollo. In contrast to Sketis’s, whose reputation spread widely outside of Egypt to the Mediterranean world, Apollo’s community was less well known, perhaps because of its southern location and the fact that fewer foreign, Late Antique Christians traveled to it. The Monastery of Apa Apollo’s location should not, however, suggest it was small or insignificant. The central built community covered an area of 40 hectares and its walls were painted with the faces of numerous monks who may have once lived at the community in the sixth and later centuries (see Fig. 36). If the remote cliff dwellings are included in the area, the community expands to an area of 78 hectares, although not all of the land was used for building. Bawit is roughly half the size of Al-Ashmunein (Gk. Hermopolis Magna) (65 hectares), one of the largest cities in Upper Egypt for this period. This comparison illustrates that Bawit was a medium-sized town in its own right. Given Bawit’s size and significance as a major settlement in Middle Egypt, how does its foundation narrative history contribute to a history of monastic authors crafting a generalized landscape, which overshadowed the reality of the actual monastic landscape?

36. Wall painting from Chapel 56 at Bawit showing three monks: Apa Makarios, Apa Moses the Freeman, and Apa Jeremias.