Music was everywhere in ancient Rome. Wherever one went in the sprawling city – in houses, on the street, in theatres and amphitheatres, shops and bars, temples and marketplaces – one encountered signs of musical life. Busking musicians, dispersed along busy thoroughfares, competed for the attention of passers-by.Footnote 1 Travellers entertained themselves by humming cheerful jingles.Footnote 2 Labourers and shopkeepers sang while they worked.Footnote 3 At night, taverns came alive with singing and piping, strumming and drumming.Footnote 4 Wealthier patrons meanwhile, were serenaded by bands of musicians as they dined in their homes.Footnote 5 For every occasion, for every season and for every time of day, there was music. And every member of Roman society – whether old or young, male or female, rich or poor – played their part in keeping this vibrant musical culture alive.

But music, to the Romans, was never purely incidental. It had the power to captivate hearts and minds, to educate and enlighten, to forge communities and mould citizens. ‘Music is connected with knowledge of things divine’, writes Quintilian in his Institutes of Oratory (composed ca. 95 CE), ‘and no one can doubt that some men famous for wisdom have been devotees of music’.Footnote 6 For centuries, music-making brought the Roman people together in the pursuit of religious and artistic expression. It was through song that the Romans paid tribute to the gods; it was from song that poetry was born. According to Quintilian, music even held the key to Rome’s ascendancy as a military power: ‘What else is the function of trumpets and horns in our legions? The more forceful their sound, the more does Roman military glory prevail over the rest.’Footnote 7

And yet, to many Romans – Quintilian included – music also posed a real and present danger to society. In the eyes of Cicero, writing in the middle of the first century BCE, singing in the forum constituted ‘a great perversion’ (magna perversitas) of societal norms, an action strongly discordant with civilized behaviour.Footnote 8 It was imperative, therefore, that the right kinds of music were heard in the right places and at the right times. Members of the upper classes, Cicero maintained, should sing only when it was appropriate.Footnote 9 As early as the 180s BCE, a Roman magistrate was publicly reprimanded by a prominent senator for ‘singing whenever he feels like it’ (cantat ubi collibuit).Footnote 10 Moral strictures of this sort are commonplace in Roman literature. Men and women are accused of enjoying music too enthusiastically or playing instruments too skilfully. What inspired this rhetoric of contempt? Why did singing and playing instruments generate such intense feelings of anxiety, indignation and shame among generations of Roman citizens? What were the criteria for distinguishing ‘good’ music from ‘bad’? And who was responsible for determining these criteria?

This book examines the role that music played in the political and social landscape of ancient Rome. It does not purport to be a comprehensive history of Roman music as such. Rather, it is intended primarily as a study of how Roman attitudes to music evolved throughout the mid-to-late Republic and early Principate, and how music was used as a political tool by Roman elites during this period. Since the vast majority of the extant written sources from the Roman world were produced by members of the educated upper classes, it is much easier to reconstruct the musical experiences and attitudes of those at the very top of society than those lower down. However, the elite’s interactions with music had far-reaching consequences for the urban populace at large. This book asks not only what Roman leaders thought about music and how they used music, but also how their use of music in turn affected wider social attitudes and practices.

Approaching Roman Music

Although the centrality of music in the cultural life of the ancient Romans has long been recognised, the intersections between music, politics and society at Rome have not received sufficient attention.Footnote 11 The study of Roman music, in general, has languished by comparison with the study of Greek music, which has in recent decades blossomed into a vibrant field of scholarship.Footnote 12 Indeed, Roman music has traditionally been dismissed as little more than a crude derivative of Greek music – a topic worthy of antiquarian interest, perhaps, but devoid of any real historical or musicological importance. This theory, which has its roots in the intellectual currents of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, is predicated on a long-outdated notion of the moral and aesthetic superiority of Greek culture over Roman.Footnote 13 The Romans, being a pragmatic and bellicose people, are said to have developed a taste for music only through exposure to, and appropriation of, the civilizations of conquered peoples (especially the Greeks and Etruscans). So, in the entry on ‘music’ in the Oxford Classical Dictionary, published in 1949, it is stated that ‘in the whole range of Latin literature we find only the most commonplace and conventional references to music, and … nowhere is there any indication that the Romans regarded music as anything more than a tolerable adjunct of civilized life’.Footnote 14 John Landels reaches a similar conclusion in his book Music in Ancient Greece and Rome (1999): ‘In dealing with the role of music in Roman life, we shall not be looking at the emergence of a new and totally different musical culture. It would be fair to say that the Romans did not attempt to develop a musical identity of their own.’ The reader is even assured that ‘the Romans themselves do not seem to have been troubled or embarrassed by their lack of interest and proficiency in music’!Footnote 15

Not all scholars have been so dismissive. In 1967, the German philologist Günther Wille published a weighty monograph entitled Musica Romana: die Bedeutung der Musik im Leben der Römer. In the book, Wille sought to challenge the prevailing view of the Romans as an innately unmusical people. His approach was simple yet ambitious: to document every identifiable reference to music in the entire corpus of Latin literature, supplemented by inscriptions and material artefacts. The product of this endeavour is an impressive anthology of more than four thousand texts, laid out over some seven hundred pages. Coincidentally, just two years before the publication of Musica Romana, the art historian Günther Fleischhauer published an extensive catalogue of musical images from Rome and Etruria, comprising some eighty illustrations with accompanying descriptions.Footnote 16 The two works did much to raise the profile of the subject in the face of continued scholarly efforts to undermine its value. However, while Wille succeeded in demonstrating the pervasiveness of music in Roman culture, his treatment of the evidence was inadequate in several respects. Musica Romana provides an object lesson in the privileging of quantity over quality: each page is crammed with copious references to primary source material, and yet the author’s broad thematic deployment of this material allows virtually no scope for analytical discussion. Sensitive issues of philological and historical importance are passed over in silence. Moreover, many of Wille’s arguments in favour of the ‘originality’ of Roman music (such as the theory that Horace’s lyric poems were set to melodies) do not hold up to scrutiny.Footnote 17 Above all, then, Musica Romana sounded a clarion call for further research in this area.

Only in the last few decades have scholars begun to comb through the vast body of evidence which Wille and Fleischhauer so painstakingly assembled nearly sixty years ago. Classical philologists such as Nevio Zorzetti, Thomas Habinek and Denis Feeney have attempted to trace the origins of Latin literature back to an archaic Roman song culture, whose existence is first posited by Cato the Elder.Footnote 18 Thanks to the pioneering work of Timothy Moore, we now have a much deeper appreciation of the vital contribution of song and dance to the Roman theatre.Footnote 19 Studies have also demonstrated how music enhanced Roman audiences’ experience of gladiatorial games and chariot races by punctuating moments of tension or climax.Footnote 20 Jörg Rüpke, Christophe Vendries and others have done much to illustrate the role of the sensorium, and sound especially, in shaping participants’ experience of religious rituals in Rome, stressing, for instance, the association of different kinds of music with different sanctuaries and cults.Footnote 21 Nicholas Horsfall has drawn attention to the importance of music in the culture of the Roman plebs, emphasising in particular the strong connection between song and memory.Footnote 22 Finally, the lives of musicians in the Roman world have been the subject of no fewer than four monographs, including, most recently, Alexandre Vincent’s Jouer pour la cité: une histoire sociale et politique des musiciens professionnels de l’Occident romain.Footnote 23

The growing body of scholarship devoted to Roman music attests to the great potential of this subject to enrich our understanding of the ancient world. Nonetheless, it would not be an overstatement to say that we have barely scratched the surface of the evidence. Above all, there remains an urgent need for a systematic analysis of what we might call the ‘cultural politics’ of Roman music – that is, the attitudes, discourses and ideologies generated by, and in response to, musical practices. Following the model of Wille’s Musica Romana, scholarly discussions have tended to filter the sources through a synoptic lens. As a consequence, they have promoted a largely homogeneous view of Roman musical culture, with little variation across time and space. However, as I argue in this book, the Roman musical experience was marked by conflict, contradiction and change. It is true that many aspects of Roman music-making, such as the use of certain instruments and the organisation of musical performances, remained constant over several centuries. However, we should not assume that the Romans’ attitudes towards and interactions with music were unaffected by broader social, cultural and political developments. On the contrary, as we shall see, Roman engagements with music are inextricably bound up in complex and evolving discourses on morality, class, ethnicity, gender and sexuality. By paying closer attention to these discourses, we can gain a more nuanced and more fully contextualised view of music’s place in Roman society.

Sources of Evidence

Understanding the musical experience of historical peoples is a task fraught with difficulty. In the case of ancient Rome, the difficulty is compounded by the fact that we know relatively little about the actual melodies that were heard by listeners some two millennia ago. There are, nevertheless, various sources of evidence which help us to understand the role of music in Roman life. Of particular importance for the purposes of this book are literary texts which contain descriptions of musical performances, accounts of the history of music, or reflections on the theoretical, ethical and political significance of music. Passages of this nature crop up in a wide variety of genres, but are chiefly found in speeches, histories, poems and philosophical treatises. Of course, there is much that does not survive. The loss of the treatise on music written by M. Terentius Varro, the great scholar and polymath of the first century BCE, is particularly regrettable. Contained in the seventh book of his Disciplinae (Disciplines), the De Musica was widely consulted by later musicologists, including Augustine, Martianus Capella and Boethius.Footnote 24 Varro’s contemporary, Cicero, is a more eloquent witness; his views on music have been particularly neglected and will be considered at length in Chapter 2.

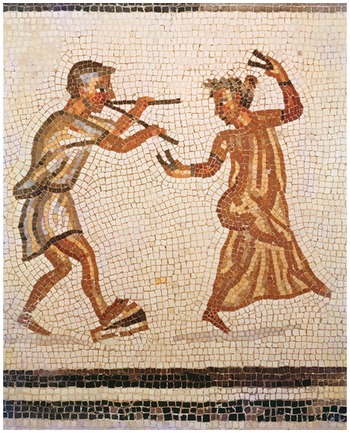

There are two additional sources of evidence that contribute to our understanding of Roman musical culture – namely, epigraphy and art. The lives of musicians are documented in hundreds of funerary inscriptions from across the Roman world. These range from simple records of the deceased’s name and profession to elaborate verse epitaphs commemorating the individual’s attainments. Many musicians belonged to professional associations, known as collegia, which set up inscriptions publicly memorialising their participation in civic festivals and religious cults.Footnote 25 As Vincent shows, this rich body of evidence attests to the integration of many freed or freeborn musicians into Roman society, affording an impression that is in many ways diametrically opposed to that conveyed by the literary sources.Footnote 26 Scenes of music-making are also ubiquitous in Roman art.Footnote 27 For example, portrayals of singers and musicians in Pompeian wall-paintings and mosaics can help us to visualise what a musical performance looked like from the perspective of Roman audiences, supplementing the eye-witness accounts of contemporary authors (see Fig. 0.1). Additionally, the appearance of musical imagery on statues and coins often carries distinct political resonances. The representations of Apollo in Augustan and Neronian iconography are particularly revealing in this respect, as will be discussed in Chapters 3 and 4 respectively.

Figure 0.1 Mosaic panel by Dioscurides of Samos showing masked actors playing musical instruments (tibiae, cymbala and tympanum). Based on an episode from Menander’s Theophoroumene.

Although this book is not primarily concerned with uncovering the actual sounds of Roman music, it will be necessary at various points to engage with the practical and technical aspects of Roman song and instrumental performance. It seems worthwhile, therefore, to examine briefly how one might approach such a topic. There are three main types of evidence which aid in the reconstruction of Roman music: extant examples of ancient Greek musical notation; Roman dramatic texts from the late third and second centuries BCE that were originally set to music; and archaeological remnants of musical instruments. The best insights can be gleaned from examining all three types of evidence together.

Around sixty examples of notated Greek music survive from antiquity. Interestingly, the majority of these examples are preserved on stone or papyrus fragments from the Roman Empire, including several hymns attributed to Mesomedes, the court musician of the emperor Hadrian.Footnote 28 The interpretation of Greek musical notation is made possible by the survival of a treatise written by the late-antique Egyptian scholar Alypius. Entitled Introduction to Music (Eisagoge Mousike), the treatise lists the correspondence of each symbol to its respective note on the Greek musical scale. This has allowed modern experts to produce accurate renderings of ancient melodies, which, when performed on replica instruments, afford a remarkably realistic impression of ancient Greek music as it would have sounded some two millennia ago. However, if we wish to understand the indigenous musical traditions of Roman Italy, Greek notation can only take us so far. First, the Greek system of musical notation was, as far as we know, never repurposed by composers of Latin songs.Footnote 29 Second, musical notation does not seem to have been in widespread use in Greco-Roman antiquity, but rather was developed by and for a small number of professional practitioners.Footnote 30 Third, the fact that Latin and Greek had different systems of accentuation is likely to have resulted in a significant degree of melodic variation: songs set to Latin words are unlikely to have used the same melodies as songs set to Greek words.Footnote 31

For further insights, we can turn to the comedies of Plautus and Terence. The musical complexity of Roman drama has been brilliantly illuminated by Moore in a series of pathbreaking publications, including most notably his monograph Music in Roman Comedy, published in 2012. We know from various sources that performances of Roman comedy were accompanied by a pipe-player (tibicen). The actors, meanwhile, did not simply recite their lines, but also sang and danced. More specific information about the plays’ musical accompaniment comes from didascaliae, production notes preserved in the manuscripts of Plautus and Terence. For example, the didascaliae preceding Terence’s Phormio state that ‘Flaccus, the slave of Claudius, produced the music on unequal pipes (tibiis inparibus) through the whole play’.Footnote 32 The plays themselves also contain valuable clues as to the nature of the musical accompaniment. Analysing the metrical arrangements of the texts allows us to distinguish between verses that were sung (cantica) and verses that were recited (deverbia).Footnote 33 We can therefore determine when the music started and stopped, and on this basis draw inferences about how Plautus and Terence used music to enhance the dramatic effect of their plays (for example, by accentuating certain plotlines or character traits). Additionally, as Moore’s recent research has shown, the metres of Roman comedy can provide insights into an audience’s musical memories within a play and between different plays, based on their recollections of different musical patterns.Footnote 34

Dozens of musical instruments from the Roman period have been brought to light in archaeological excavations. Finds have been made throughout Italy and Sicily, and in sites as far removed as Gaul and the Levant.Footnote 35 At Pompeii alone, archaeologists have discovered fifteen pipes (tibiae), five trumpets (cornua), and a large number of cymbals (cymbala), drums (tympana) and rattles (sistra) (see Figs. 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4).Footnote 36 We also have the remains of three water-organs (hydraulae), uncovered at Aquincum (modern Budapest), Dion (in northern Greece) and Aventicum (modern Avenches, Switzerland) during the twentieth century.Footnote 37 Though often extremely fragmentary, these artefacts provide valuable information about what ancient instruments looked like and how they were made. It has also been possible to manufacture playable replicas based on surviving ancient models, allowing us to ‘hear’ Roman music as it might have originally sounded (see Fig. 0.5).Footnote 38

Figure 0.2 Facsimile of a Roman cornu found at Pompeii, produced by the Belgian instrument-maker Victor-Charles Mahillon (1841–1924).

Figure 0.3 Pair of bronze cymbals linked by a chain; Pompeii, first century CE. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.

Figure 0.4 Roman sistrum, made of bronze or copper alloy; first or second century CE; now in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. The top of the instrument is decorated with a cat and two suckling kittens – an ornamental feature typical of Roman sistra – perhaps evoking the goddess Bastet.

Figure 0.5 Performance by the group ‘Ludi Scaenici’ at the Festival Tarraco Viva; Tarragona, Spain.

Terminology

The Romans had no single word for what we could call ‘music’. The Greek concept of mousike encompassed not only ‘music’ in the modern sense of the term, but also drama, poetry and dance. In Latin, musica and its derivatives have a different set of meanings. Roman writers typically refer to the ars musica or scientia musica as a way of denoting the discipline of music theory, which was divided according to the Greek model into the three sub-fields of harmonics, rhythmics and metrics.Footnote 39 To the Romans, then, a musicus (from the Greek mousikos) was one skilled in music theory, not necessarily a practising musician.Footnote 40 However, the term musicus also came to mean someone who was generally ‘cultured’.Footnote 41 Its antonym, amousos, could be used equally of someone ‘unmusical’ (that is, lacking in musical cultivation) or of someone ‘uncultured’.Footnote 42 It is important, therefore, to pay close attention to the specific contexts in which these words are used in order to determine their precise meaning.

Roman terminology pertaining to music can be divided into three main categories: Greek technical terms in transliteration (e.g. musica, harmonia, symphonia, melodia), Latin translations of Greek technical terms (e.g. intervalla, accentus) and indigenous Latin words (e.g. carmen, cantus, modus, numerus).Footnote 43 An author’s use of a given term was influenced by various factors, including adherence to a particular Greek source, generic conventions and the date of writing. Cicero comments on the fact that the Romans preferred to borrow the Greek words for ‘music’, ‘philosophy’, ‘rhetoric’ and so on, ‘although they might have been translated into Latin’ (quamquam Latine ea dici poterant), on the grounds that these words ‘have been familiarised through use’ (usu percepta sunt).Footnote 44 Vitruvius, writing in the 20s BCE, observes that in his time there were still no Latin equivalents for many Greek musical terms.Footnote 45 However, as will become clear throughout this book, the fact that Roman thinkers continued to employ Greek loanwords to express musical ideas does not necessarily mean that their conception of music was wholly indebted to the Greeks. In dealing with Roman arguments about music, it is important to establish which elements derive from Greek models and which elements reflect independent thinking on the part of the Roman author(s) in question.

Deciphering Latin musical terminology presents various challenges. Commonly used words like modus and numerus have a wide semantic range, and it is not always easy to ascertain their precise meaning in a given context. Modus (literally ‘measure’), when applied to music, can describe either rhythm or melody, or both.Footnote 46 Likewise, numerus (number) is conventionally linked to rhythm, but in some cases it appears to be more closely associated with melody or harmony.Footnote 47 At the same time, we must be wary of conflating the ancient term harmonia with our modern concept of ‘harmony’. In both Greek and Latin, harmonia referred to an agreeable progression from one note to another; it dealt with ‘the intervals between sounds’.Footnote 48 Harmony as we know it pertains not to the intervals between musical notes, but to a combination of notes sounded simultaneously to produce chords and chord progressions. While both the ancient and modern definitions have an aesthetic dimension, in that they emphasise the pleasing effect of ‘harmonious’ music, the system of chord-based harmony is generally regarded as an invention of the late Middle Ages.

Descriptive terms for music, like flexus (bending) and fractus (broken), pose an additional set of interpretative issues, since it is often unclear whether they are being used in a technical or rhetorical sense. The idea of ‘bending’ music seems to have developed in Greek discourse as a reaction to the so-called New Music of the late fifth century BCE.Footnote 49 The term kampe (bend) is associated in the first instance with melodic modulation (the Greek lyric poet Pindar speaks of a ‘bending melody’, kampylon melos), but it was also used metaphorically as an indictment of the moral laxity of the New Music (contrasted with the simplicity of traditional music).Footnote 50 In Latin descriptions of music, words like flexus or modulatio often have a similarly negative connotation.Footnote 51 For example, while singers and orators alike are encouraged to employ vocal ‘bending’ for the sake of pleasing the ears of their listeners, they are also warned against excessive use of this technique, on the grounds that too much ‘bending’ was unmanly and undignified. Similarly, the term fractus (or infractus), when used in connection with music, entails what Maud Gleason describes as a kind of ‘semantic double-determination’: ‘words or voices that are “broken” are weak, and therefore feminine; rhythms that are “broken” (in Greek, keklasmenoi) soil the dignity of prose with the unmanly ethos of certain lyric metres’.Footnote 52 Instead of looking in vain for the precise technical application of certain musical terms, therefore, we must root out their polyvalent meanings within broader Greek and Roman discourses on morality, sexuality and aesthetics.

The Romans employed various words for song, including carmen, cantus, cantio and canticum.Footnote 53 These words pose notorious problems for the modern interpreter. Since the Latin language does not draw a sharp distinction between singing and speaking, it is often extremely difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether the usage of carmen or cantus in a given text denotes an action that we would consider ‘musical’. According to Thomas Habinek, who tackles this issue at length in his book, The World of Roman Song: From Ritualized Speech to Social Order (2005), the verb canere (to sing) and its cognates ‘describe speech made special through the use of specialized diction, regular meter, musical accompaniment, figures of sound, mythical or religious subject matter, and socially authoritative performance context: in effect, speech that has been ritualized’.Footnote 54 Thus, the verbs canere and cantare indicate, in Habinek’s opinion, a kind of ‘marked’ language, in contradistinction with verbs like loqui (to speak), which indicate ‘unmarked’ language. To add to the complexity, Habinek imposes a further division between canere and cantare: whereas canere refers to marked language in a general sense, cantare is used specifically for ‘the repetition or reperformance of someone else’s authorizing performance’.Footnote 55 Habinek’s framework is useful in highlighting the integral role of song in the formation of Roman social ritual. However, it is of limited value in shedding light on the historical realities of Roman musical performance. When we encounter an instance of ‘marked’ or ‘authorizing’ discourse, how are we to know that singing is involved, especially if we lack external context? A remark in Cicero’s treatise De Legibus illustrates the problem. In passing, Cicero describes the Twelve Tables, an early Roman law code, as a carmen necessarium, which he was required to learn as a boy.Footnote 56 Nicholas Horsfall, in his study of Roman plebeian culture, takes this remark as straightforward evidence for the use of music as a mnemonic aid in the Roman classroom – just as Augustine, much later, recalled chanting his times tables and Jerome the letters of the alphabet.Footnote 57 However, it is possible that Cicero never actually sang the Twelve Tables. As Habinek points out, verbal formulae which required ‘specialized diction’ could be classified as carmina on the basis that they were differentiated from everyday (unmarked) speech. In such cases, the sources unfortunately raise more questions than answers.

Finally, there are terms relating to musical instruments.Footnote 58 Here we find ourselves on firmer ground. By far the most important instrument in the Roman world was the tibia (aulos in Greek), a reed pipe usually played in pairs (see Figs. 0.6 and 0.7). The tibia was used in many types of civic and religious rituals, including sacrifices, theatrical performances and funerals.Footnote 59 A male player of the tibia was called a tibicen, a female player a tibicina.Footnote 60 Other wind instruments employed by the Romans include the panpipe (fistula in Latin, syrinx in Greek);Footnote 61 the transverse flute (tibia obliqua in Latin, plagiaulos in Greek);Footnote 62 the water-organ (hydraulis);Footnote 63 and the bagpipe.Footnote 64

Figure 0.6 A tibia from Roman Syria, made of bone with bronze and silver facing and decorative chalcedony bulb, L. 23⅛ in. (58.6 cm); ca. 1–500 CE.

Figure 0.7 Detail of mosaic panel showing a dancer and tibia player. One of five panels with circus and arena scenes, from Sta. Sabina on the Aventine, Rome; third century CE. Museo Pio Clementino, Vatican Museums.

Next to the tibia in importance was the cithara (kithara in Greek). The cithara typically had seven strings and was played with a plectrum in the right hand, while the left hand was used for dampening the strings. Citharae were showpiece instruments, designed for concert performance.Footnote 65 A player of the cithara was called a citharista or citharoedus; the latter term refers specifically to a musician who sang while playing the cithara.Footnote 66 Although it is conventional to translate cithara as ‘lyre’ (as I shall do in this book), there were other types of lyres in Rome besides the cithara. Amateurs and students usually opted for the smaller, bowl-shaped tortoise-shell lyre known in Greek as a chelys (lyra or fides in Latin) or its baritone version, the barbitos.Footnote 67 The Romans were also familiar with a variety of harps of eastern origin. These included the sambuca, a type of arched harp, the trigonon, a triangular harp, and the pandura, a kind of lute.Footnote 68 The generic term for ‘harp’ in Latin is psalterium.Footnote 69 Harp-players are most often found in convivial settings, reflecting their traditional presence in Greek symposia, although they also took part in certain religious rituals.Footnote 70

Horns and trumpets constitute another important category of instruments. There were three main types: the tuba, a long, straight trumpet with a flared bell, made typically of bronze or brass; the cornu (or bucina), a curved horn (Fig. 0.2); and the lituus, a straight trumpet with a curved end. The players of these instruments were called tubicines, cornicines and liticines respectively; aenatores was also used as a generic term for brass-players.Footnote 71 In the textual sources they feature most prominently in military settings, accompanying the daily routines of the army camp or giving signals on the battlefield.Footnote 72 Cornicines and tubicines also participated in triumphs, processions (pompae), funerals, chariot-races and gladiatorial contests.Footnote 73

The most widely used percussion instruments in Rome were hand drums (tympana), cymbals (cymbala) and castanets (crotala). We also encounter the so-called scabellum (or scabillum), a type of clapper made of wood or metal that was worn on the foot (see Fig. 0.7), and the sistrum, a hand-held rattle associated with the cult of Isis (Figs. 0.4 and 0.8). With the exception of the scabellum, which was usually played in theatrical settings by male tibicines, percussionists tended to be women. This is reflected both by the preponderance of feminine nouns in Latin (tympanista, cymbalista, crotalistria, etc.) and by the common depiction of female percussionists in Roman art.Footnote 74

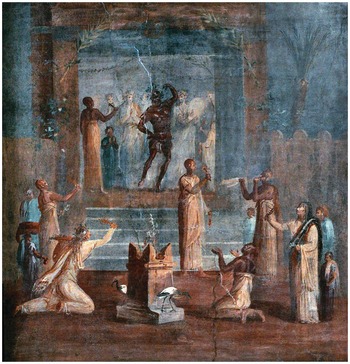

Figure 0.8 Wall painting from Herculaneum depicting a ceremony of the cult of Isis. A figure in a mask performs a sacred dance, accompanied by a female tympanum-player dressed in white, who stands behind him, and a throng of attendants with sistra; ca. 1–79 CE. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.

Greek and Etruscan Influences on Roman Music

It has become axiomatic in modern scholarship to speak of Roman music as simply an amalgamation of Greek and Etruscan music. In support of this idea, scholars have pointed to three factors in particular: the Greek and Etruscan origins of Roman instruments; the dependence of Roman musicological thought on earlier Greek models; and the prevalence of Greek-derived names in the prosopography of Roman musicians. However, these considerations are of limited value in assessing the social and political dynamics of Roman musical culture over the longue durée. In recent decades, scholarly advances in the fields of philology, philosophy, history and archaeology have opened up a range of nuanced perspectives on the cultural interface between imperial Rome and the Greek East. The phenomenon of Hellenisation, it is now understood, was not simply the hegemonic appropriation of a subject culture, as satirised in the immortal verse of Horace, Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit (conquered Greece took its savage victor captive).Footnote 75 Rather, it invoked a bilateral process of borrowing and exchange. Crucially, the transmission of culture through time and space changed how that culture was received and reproduced in its new setting. Thus, to insist on the derivative character of Roman music is to cling onto an outdated notion of what ‘Roman culture’ represents. What is more, it ignores the basic fact that music reflects the specific historical contexts of its creation.Footnote 76 The study of Roman music cannot be reduced to a discussion of musical instruments, performance styles and techniques. We must cast our net more broadly, to look not only at the different ways in which music was consumed, but also at the societal, cultural, political and psychological factors which conditioned how music was experienced and imagined by people of different ages, genders and social classes.

There can be little doubt that the Romans were exposed to foreign musical influences at an early stage in their history through contact with the Hellenised communities of Etruria and northern Italy. Evidence from pottery and tomb paintings attests to the use of music in Etruscan rituals as early as the seventh century BCE.Footnote 77 A wide range of instruments is represented in Etruscan art and archaeology, including double-pipes, panpipes, transverse flutes, trumpets, lyres and castanets. When this music made its way south to Latium cannot be clearly determined. Of course, it is likely that the Romans’ earliest encounters with Etruscan music have left no trace in the archaeological record.Footnote 78 Strabo, the Greek geographer of the first century CE, goes so far as to describe Etruria as the source of ‘all music publicly used by the Romans’ (μουσικὴ ὅσῃ δημοσίᾳ χρῶνται Ῥωμαῖοι), but he unfortunately does not elaborate on this statement.Footnote 79 The earliest tangible evidence for musical interaction between Rome and Etruria dates from the fourth century BCE. A number of engraved bronze boxes (cistae) from Latium, produced mostly during the fourth century, represent pipe-playing satyrs accompanying female dancers in the performance of scenes from Euripidean tragedy. Similar Dionysiac imagery can be found on contemporary red-figure vase paintings from Etruria and Campania.Footnote 80 In addition, the historian Livy, describing the first theatrical performances in Rome in 364 BCE, records that ‘dancers, summoned from Etruria, dancing to tunes provided by a tibicen, performed proper dances in the Etruscan manner, without any singing and without imitating the action of singers’ (sine carmine ullo, sine imitandorum carminum actu ludiones ex Etruria acciti, ad tibicinis modos saltantes, haud indecoros motus more Tusco dabant).Footnote 81 Regardless of the overall historical accuracy of Livy’s account, the suggestion that Etruscan music influenced the development of Roman drama seems creditable on a priori grounds, and is broadly consistent with the impression afforded by the material culture from Latium and the surrounding regions.Footnote 82

Despite the strong ties between Roman and Etruscan music, the Romans saw themselves first and foremost as the inheritors of a Greek musical tradition, which predated the foundation of Rome itself.Footnote 83 The Greeks’ devotion to music was legendary. As Cicero writes, ‘musicians flourished in Greece; everyone would learn music, and whoever was unacquainted with it was not regarded as fully educated’ (in Graecia musici floruerunt, discebantque id omnes, nec qui nesciebat satis excultus doctrina putabatur).Footnote 84 As with Etruscan music, documenting the Hellenic influence on early Roman music is exceedingly difficult. We must rely for the most part on literary texts written during the height of the Roman Empire. A particularly interesting source is Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric who migrated to Rome in around 30 BCE. Dionysius’ magnum opus, entitled Roman Antiquities, traces the history of Rome from its beginnings down to the time of the First Punic War. In one section of the work, Dionysius describes the customs of the Arcadians, a Greek people who came from their homeland to settle on the site where Romulus would later establish the city of Rome. The Arcadians, Dionysius explains, brought with them to Italy ‘music played on instruments which are called lyres (λύραι), trigona (τρίγωνα) and pipes (αὐλοί), the previous people having used no musical devices apart from pastoral panpipes (σύριγξι ποιμενικαῖς)’.Footnote 85 Dionysius goes on to relate how the twins Romulus and Remus, after finding shelter near the Palatine Hill, were given a Greek education by the native settlers, who taught them ‘letters, music (μουσικήν) and the use of Greek arms’.Footnote 86 As Andrew Barker rightly points out, this narrative is far from a reliable record. Not only is it reminiscent of other Greek accounts of the development of ‘primitive’ societies, but it also aligns with the broader aim of Dionysius’ historiographical project – namely, to establish the Greek lineage of the Romans and their customs.Footnote 87 Nevertheless, Dionysius’ account highlights the complex role of music in the cultural memory of Rome’s inhabitants. On the one hand, his attempt to write mousike into the story of Rome’s foundation shows how the Greek and Roman musical traditions were viewed as historically intertwined: Roman mousike is presented by Dionysius as both originating from and developing in tandem with Greek mousike. On the other hand, we can see Dionysius responding here to sceptical readers, both Greek and Roman, who saw music as a late, and therefore relatively minor, addition to the Roman cultural scene. Cicero, for all his admiration of Greek musici, freely admitted that the Romans had been slow to adopt the Greek arts of poetry, music and geometry, choosing to focus instead on oratory.Footnote 88 In reality, Hellenic influence on Roman music was both continuous and pervasive, and most likely began long before the advent of recorded history.

The expansion of the Roman Empire during the second century BCE had a particularly profound impact on Rome’s relationship with Greek music. Through a series of stunning victories – over the Carthaginian general Hannibal in 201, the Seleucid King Antiochus III in 188, the Macedonian king Perseus in 168 and the Achaean League in 146 – Rome cemented its place as the political and cultural epicentre of the Mediterranean world. Musicians, like many other professionals, flocked to Rome in droves from all over the Greek East in search of patronage and employment. Livy comments revealingly on the mass migration of female harp-players (psaltriae sambucistriaeque) to Rome following the triumph of Cn. Manlius Vulso in Asia Minor in 186. For Livy, the arrival of these performers in the capital symbolised the Romans’ newfound taste for imported luxuries and contributed ultimately to the moral decay of the Roman aristocracy.Footnote 89

No doubt inspired by the influx of highly skilled musicians from abroad, an increasing number of Roman citizens, many from the upper echelons of society, decided to take up musical pursuits themselves. Although we lack quantitative data for the number of Romans who received musical training in any given period, the profusion of individual examples speaks to a widespread and long-lasting tradition of amateur music-making. Children born into noble or wealthy families were frequently taught to sing, dance and play instruments as part of their education; as adults, they continued to perform privately in the company of friends and relatives.Footnote 90 Women were probably afforded greater access to musical instruction than men. Indeed, musicality seems to have been regarded by many as a distinctly feminine virtue. For example, Cornelia, wife of Pompey the Great, was admired for her skill at playing the lyre.Footnote 91 And at the turn of the second century CE, the Younger Pliny boasted of having his verses sung to the accompaniment of the cithara by his wife Calpurnia, ‘with no musician to teach her but the best of masters, love’.Footnote 92 Nevertheless, we should not underestimate the number of men who possessed some degree of musical proficiency. The Roman general Sulla was said to be an excellent singer.Footnote 93 Lucius Norbanus, the consul of 19 CE, was an avid trumpeter.Footnote 94 We also know of several Roman emperors who were talented musicians.Footnote 95 Most notorious of all, of course, was the much-maligned Nero; he was remembered by later generations simply as citharoedus princeps, ‘the emperor who sang to the lyre’.Footnote 96

One did not need to know how to sing or play an instrument to be considered a connoisseur of music. Roman elites could also display their wealth and cultural sophistication by patronising Greek musicians.Footnote 97 The staging of private musical concerts, known as symphoniae, became fashionable during the late Republic and early Principate, inspiring a craze for musically trained slaves (symphoniaci).Footnote 98 The Romans’ penchant for such entertainment is reflected in the decoration of their houses. Pompeian wall paintings often depict musicians engaged in performance, dressed in fine clothing and playing expensive instruments. A particularly well-preserved example comes from the villa of Publius Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale (Fig. 0.9). Dated to around 40–30 BCE, it shows a seated woman holding a large, gilded lyre, while a younger girl stands behind her. The identity of the pair has been disputed, but the most persuasive interpretation is that they represent a Macedonian queen and her daughter or younger sister.Footnote 99 By commissioning artistic depictions of music-making like the one found at Boscoreale, Roman patrons were able to create an air of luxury in their house while advertising their cultural sophistication to visitors.

Figure 0.9 Wall painting with seated woman holding a cithara, from Room H of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale; ca. 50–40 BCE; New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1903 (03.14.5).

The rise of philhellenism affected not only how Roman elites made and listened to music, but also how they engaged with it intellectually. Music came to be valued as an edifying pursuit – ‘a most beautiful art’ (ars pulcherrima), in the words of Quintilian – because of its venerable association with Greek learning (paideia).Footnote 100 By the time of Cicero, if not earlier, the study of music theory (as distinct from musical performance) had become a valuable, even necessary, component of an aristocratic education.Footnote 101 An aspiring orator could be expected to know the technical terms for the different strings of the lyre and the different intervals.Footnote 102 Architectural experts like Vitruvius applied the Pythagorean principle of harmonic ratios to optimise the design of theatres and other buildings.Footnote 103 Music theory also became a bedrock of the Roman philosophical tradition. From studying the precepts of Plato and Pythagoras, Aristotle and Aristoxenus, Roman thinkers such as Cicero, Varro and Seneca the Younger gained an appreciation of how music affected the soul in both positive and negative ways and altered the character of political states.

And yet, the spread of Greek musical culture also generated long-lasting and deep-rooted tensions in Roman society. In Roman discourse, music-making became associated with a set of undesirable traits, such as sexual depravity, effeminacy, luxury and vulgarity, all of which were regarded as quintessentially ‘Greek’ flaws. However, the Romans conceded that some forms of Greek music were more harmful than others. One could object to music on moral or aesthetic grounds while still championing the benefits of a musical education (and, even then, there was considerable disagreement about what kind of musical education was best).

In assessing Roman attitudes to music, therefore, it is vital that the content of the sources is weighed against broader considerations of genre, audience, authorial bias and historical context. The attitudes of Cicero and his friend T. Pomponius Atticus provide a case in point. In the Life of Atticus by Cornelius Nepos, we read that Atticus never exhibited a single musical entertainer at his banquets, such was his concern for avoiding needless extravagance.Footnote 104 In a similar vein, Cicero in his speeches frequently accuses his opponents of singing and dancing in order to cast aspersions on their moral character.Footnote 105 And yet, we know for a fact – thanks to Cicero’s letters – that the philhellene Atticus not only owned his own musician (named Phemius after the Homeric citharode), but also went to great lengths to equip him with a rare musical instrument from Asia Minor, enlisting the help of Cicero, who was serving as governor of Cilicia at the time, to help him find it.Footnote 106 Furthermore, when Cicero wrote to Atticus in July 54 BCE with news of Caesar’s exploits in Britain, he complained of a lack of captives ‘trained in literature or music’ (litteris aut musicis eruditos); if Atticus wished to acquire musical slaves, he would have to look elsewhere.Footnote 107 Taken as a whole, these passages remind us that the Romans’ relationship with Greek music was much more ambivalent and idiosyncratic than historians have tended to assume.

Sound, Space and Social Control

The recent proliferation of scholarship on the senses in antiquity has transformed our understanding of how sound structured the Romans’ interactions with the urban environment.Footnote 108 However, the role of music within the Roman sensorium has not yet been fully explored. In one sense, of course, music is (and was) a ‘universal language’.Footnote 109 In an age before recording technology, music broke down the barriers, both conceptual and concrete, which separated those at the top of the social hierarchy from those lower down. Amorphous and ephemeral, its presence could not easily be confined within spatial or temporal bounds. Moreover, unlike many of the sensual pleasures enjoyed by Rome’s affluent elite (foodstuffs, perfumes, fine clothing, etc.), the delights of music could be freely enjoyed by all. To experience the best music Rome had to offer, one simply had to go to the theatre and listen.Footnote 110

For the Roman governing class, who spent much of their time conducting business in public, the inescapable presence of music in the urban environment was a source of both temptation and irritation. Roman elites placed a premium on silence (a luxury afforded to them by virtue of the fact that they owned large houses which insulated them from the external noises of the city) and viewed the music of the plebs – the music of the street-corner, the theatre, the circus and the tavern – as a threat to that silence.Footnote 111 Privileging the intellectual order of the ars musica, by contrast, served to confine music to the silent realm of the library, closing it off to the disorderly, uneducated masses. Accordingly, Roman writers typically portray the people’s music as a kind of noise pollution. In a famous passage from his Moral Letters, Seneca the Younger describes the various sounds which could be heard from his apartment above a bath complex. Standing out amidst the din of passing traffic, the groans of weightlifters in the palaestra and the cries of street vendors was a busking musician warming up on little flutes and pipes at a nearby fountain (hunc qui ad Metam Sudantem tubulas experitur et tibias). Far from being a pleasant diversion, the musician merely added to the cacophony: he was supposed to be making music, but all he did was make a racket (nec cantat sed exclamat).Footnote 112

Loud music produced within the household had the potential to spill out onto the street, penetrating into public spaces where it was unwelcome.Footnote 113 Cicero ridicules a flamboyant resident of the Palatine who employed so many musicians at his dinner-parties ‘that the whole neighbourhood echoes with the sound of voices and strings and pipes and nocturnal revels’.Footnote 114 It was a source of great annoyance to Seneca that those who attended musical concerts at the houses of friends would go about in public afterwards humming the melodies they had heard – ‘a proceeding which interferes with their thinking and does not allow them to concentrate upon serious matters’.Footnote 115 From the perspective of Cicero and Seneca, music of this kind not only contributed to the noise pollution plaguing the city of Rome, but also blurred the boundary between work and play, negotium and otium. Those who sang in the Forum committed a ‘great perversion’ (magna perversitas), according to Cicero, precisely because they were claiming for their own personal leisure a space which represented both the literal and symbolic centre of Roman civic life.Footnote 116

The use of music in public religious ceremonies was subject to particularly stringent controls. The resonant tones of the tibiae were deemed essential for ensuring the efficacy of sacrifice, drowning out any extraneous noise which might detract from the sanctity of the ritual.Footnote 117 Indeed, without the constant accompaniment of the tibicen, the entire ceremony could be deemed null and void.Footnote 118 For the worshippers of Bacchus, Isis and Cybele, music took on a very different, yet equally significant, ritual meaning. Whereas traditional Roman sacrifices featured just a single tibicen, who occupied a stationary position next to the officiants, the ceremonies devoted to these ‘foreign’ deities involved a varied assortment of drums, cymbals, rattles and pipes.Footnote 119 The frenetic noise of these instruments, accompanied by the loud chanting and wailing of worshippers, was supposed to have induced a state of ecstasy in those who heard them. On certain days of the year, the priests of Cybele would dance through the streets, begging alms and playing drums while their followers accompanied them on pipes. Their ability to transgress public norms in this way reflected their status as social outsiders. According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a senatorial decree passed during the republican period prohibited ‘any native Roman citizen from processing in a spangled robe begging alms to the music of the pipes (καταυλούμενος) or celebrating the goddess’ orgies in the Phrygian manner’.Footnote 120

Disturbances to the sonic order were not always problematic, however. There were certain official occasions, such as the triumph or the Saturnalia, which facilitated a temporary suspension of social order, allowing for the controlled expression of sounds that would under normal circumstances be considered disruptive. Triumphs provided an opportunity for the populace to come together in communal celebration. Brass musicians played a prominent role in the procession, escorting the soldiers, captives and spoils on their journey through the city. The soldiers themselves would sing humorous songs which poked fun at their general.Footnote 121 The festivities which accompanied the Saturnalia in December included ‘drinking, noise and games and dice, electing kings and feasting slaves, singing naked and clapping frenzied hands’.Footnote 122 The Saturnalian king could command the guests to ‘shout out something disgraceful about himself, to dance naked, to pick up the woman playing pipes and carry her three times around the house’.Footnote 123 Music clearly added much to the carnivalesque atmosphere of these occasions.

Professional musicians even had their own festival. Held annually on 13 June, the so-called Lesser Quinquatrus (Quinquatrus Minusculae) featured a riotous parade of pipe-players through the streets of Rome. During the parade, the pipe-players wore masks and long robes and sang light-hearted verses before gathering at the temple of Minerva, the patron goddess of pipe-playing, on the Aventine Hill.Footnote 124 The origins of the festival were attributed to a famous, and possibly fictitious, incident in 311 BCE, when the pipers’ guild (collegium tibicinum) staged a walk-out in response to some unfair restrictions which had been imposed on them by the Roman political authorities.Footnote 125 Knowing that the Romans would be unable to perform the correct religious rites without their assistance, the pipe-players absconded in protest to the nearby town of Tibur. Eventually, the Senate managed to trick the tibicines into returning by getting the Tiburtines to ply them with wine until they passed out in a drunken stupor. They then proceeded to load the musicians onto wagons and drove them back to Rome under cover of darkness. The festivities of the Lesser Quinquartus – the noise, the gaudy costumes and general merriment – served as a reminder of this episode and of the tibicines’ indispensable role within the civic community.

Sensing Music, Embodying Music

Like their Greek forebears, the Romans believed that music elicited complex mental and physical responses in human beings. They conceptualised the act of listening to music not only as a sensory experience, but also as a psychological and embodied experience. Sounds ‘invaded the body, and they were capable of corrupting – or alternatively, of cultivating – minds’.Footnote 126 This phenomenon was not limited to auditory stimuli: tastes, sights and smells also worked upon the body in powerful ways.Footnote 127 However, ancient sources give an indication of the particular potency of music in relation to other sensations. ‘Nothing is so akin to our minds as rhythms and melodies (numeri atque voces)’, writes Cicero; ‘they arouse and inflame us, soften us and calm us down, and often lead us to laughter and to sadness’.Footnote 128 Hence the need for caution, according to Plutarch: ‘Melody and rhythm take us captive and corrupt us by means of concoctions more pungent and varied than the products of any cook or perfumer, overwhelming our senses … Therefore, we must be especially wary of these pleasures; they are extremely powerful, because they do not, like those of taste and touch and smell, have their only effect in the irrational and “natural” part of our mind, but lay hold of our faculty of judgement and prudence.’Footnote 129

So great was music’s influence over the mind and body that it was even thought to possess miraculous healing properties.Footnote 130 The physician Asclepiades of Bithynia, who counted Cicero among his clients, is said to have often used music to treat cases of phrenitis.Footnote 131 Celsus, the Roman medical writer active during the reign of Tiberius, prescribes ‘music, cymbals and loud noises’ (symphoniae et cymbala strepitusque) for patients suffering from depression (tristes cogitationes).Footnote 132 Listening to music was also recommended by Rufus of Ephesus (ca. 100 CE) as a cure for lovesickness.Footnote 133 The remedial benefits of music were not limited to diseases of the mind. According to the second-century writer Aulus Gellius, the sound of the tibiae was useful for alleviating the symptoms of gout and for treating snakebites.Footnote 134 Not all kinds of music were therapeutic, however. ‘The sound of music congests the head’ (cantilenae sonus caput impleat), explains the late-antique physician Caelius Aurelianus, and ‘in some cases music arouses men to madness’ (accendat aliquos in furorem).Footnote 135 One unfortunate patient, diagnosed by Galen with ‘delirium’ (paraphrosyne), imagined that a troupe of pipers had taken up residence in a corner of his house. The man cried out for them to leave, but the musicians kept on playing regardless, ‘so that they neither let up during the night, nor were in the least bit silent throughout the whole day’.Footnote 136

Music, then, had the power not only to invigorate and inspire, but also to debilitate and derange, to loosen minds and weaken bodies. An anecdote in Cicero’s treatise De Consiliis Suis serves as a cautionary tale of the dangers of musical intoxication. The philosopher Pythagoras, walking along the street one day, stumbled upon a gang of drunken youths. ‘Aroused by the playing of the pipes, as often happens’, the men were trying to break down the door of a respectable lady’s house. Sensing the danger, Pythagoras instructed the tibicina to play a different melody, and when she did so, ‘the slow pace of the rhythms and solemn character of the music calmed their uncontrolled aggression’.Footnote 137 Though the story is obviously apocryphal, it is informative for several reasons. Firstly, it reflects a widely held belief in antiquity that the younger generation was particularly susceptible to the corrupting effects of music. Secondly, the story highlights the strong association in Greek and Roman culture between the pleasures of music, wine and sex. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the story demonstrates the connection between the consumption of music and the performance of Roman masculinity. In Cicero’s time, men were expected to display self-control at all times. Since one’s capacity for self-control was thought to be conditioned by one’s environment, it mattered what kinds of music one was accustomed to hearing. Initially, the sound of the pipes encourages the rowdy behaviour of the youths. It is only when they are exposed to music of a more sedate and solemn character that they are able to regain the composure that is expected of them as adolescent men.

As noted earlier, it is common in both Greek and Latin literature for some kinds of music to be associated with a softening effect on both mind and body and other kinds with a hardening effect. This language of ‘softening’ and ‘hardening’ is heavily implicated in ancient discourses on gender: hardness (robur) is equated with virility, and softness (mollitia) with femininity. We have already seen, for example, how the blare of horns and trumpets was thought to strengthen the manly resolve of soldiers in battle. Conversely, the theatre is often criticised for promoting emasculating tunes and rhythms. Thus, Quintilian draws a distinction between proper ‘macho’ types of music (traditional banquet songs, military fanfares, songs to accompany manual labour, and so on) and the ‘effeminate’ (effeminata) music of the contemporary stage, ‘corrupted by shameful melodies’ (inpudicis modis fracta); the latter, he claims, has ‘destroyed any vestige of manly strength left in us’ (quid in nobis virilis roboris manebat excidit).Footnote 138 Three centuries later, the historian Ammianus Marcellinus bemoaned the fact that Roman soldiers had abandoned the traditional war chant in favour of ‘effeminate ditties’ (cantilenas … molliores), doubtless picked up from the theatre.Footnote 139

Beyond the realm of public entertainment, the gendering of music was also reinforced in the religious sphere. The cults of Cybele, Isis and Bacchus were notorious for driving worshippers into a music-induced frenzy. Instruments like the sistrum, the rattle beloved by the followers of Isis, and the tibia Phrygia, the distinctive curved pipe associated with the rites of Cybele, created a powerfully charged sonic atmosphere, ideal for stimulating minds and loosening bodies; the ‘Phyrigan pipe’ was said to ‘breathe life into bones with its liquid spirit’.Footnote 140 Music, in these contexts, facilitated not only the relaxation of social inhibitions, but also the subversion of conventional gender roles. For example, Juvenal imagines the wailing of the effeminate galli (the castrated priests of Cybele) drowning out the voices and drums of their lower-ranking followers, while Seneca the Younger refers to them as ‘half-men’ (semiviri) driven out of their minds ‘upon command’ (ex imperio) by the sound of the tibiae.Footnote 141 In effect, the loud singing and instrumental music which accompanied the public rites of the galli served as an audible marker of their liminal status in-between the masculine and feminine spheres (see Fig. 0.10).

Figure 0.10 Marble funerary relief depicting a priest of Cybele with cymbala, tympanum and Phrygian tibia; from Lavinium, Rome; ca. mid-second century CE. Musei Capitolini, Centrale Montemartini, Inv. S. 1207.

The Status of Musicians

Although musical expertise was widely frowned upon by the Roman upper classes, men and women of lower status who chose to practice music professionally enjoyed relatively good social and economic prospects. As Alexandre Vincent has highlighted, many musicians in Rome belonged to the respectable middling ranks of society, performing important functions in the army, law courts, political assemblies and other civic settings. These musicians were social insiders, with access to the same opportunities for long-term employment, financial success and community-building that were available to other urban professionals in the Roman world.Footnote 142 However, the musicians whose lives are foregrounded in Vincent’s study represent in many ways a privileged group. At the opposite end of the spectrum were enslaved musicians, sometimes called symphoniaci, who were employed by their owners (or rented out) to provide entertainment at parties and other social gatherings. Cicero refers quite frequently in his speeches to the buying, selling and exchanging of symphoniaci among wealthy senators, especially those stationed in the East.Footnote 143 Horace portrays a slave-dealer at a market in Rome advertising a young boy who ‘will sing for you over your cups in an unpolished yet charming manner’ (canet indoctum sed dulce bibenti).Footnote 144 Similarly, in a scene from the Life of Aesop, an anonymous biography dating from the second century CE, a merchant arrives on the Greek island of Samos with several slaves in tow, including one trained as a musician. In preparation for the auction, ‘he dressed the musician, who was good-looking, in a white robe, put light shoes on him, combed his hair, gave him a scarf for his shoulders and put him on the selling block’.Footnote 145 Remarkably, we have evidence from the first and second centuries CE of musical slaves from the Roman Empire being traded as far east as India and China, where they were offered to local potentates as exotic gifts.Footnote 146

The stain of slavery was one of several factors which brought the musical profession into disrepute. Even for those musicians who were not enslaved, the very fact that they were implicated in the world of commercial entertainment marked them out as socially inferior in the eyes of many citizens. The stereotype of the money-grubbing, upstart musician looms large in Roman literature. For instance, Juvenal belittles a popular lyre-player of the time by referring to him as ‘one who sells his voice to the praetors’ (vocem vendentis praetoribus). In a similar vein, Martial describes the vocations of the citharoedus and choraules as ‘money-making arts’ (pecuniosae artes).Footnote 147 Those who made a living at other people’s expense were said, according to one Roman proverb, to ‘live the life of a pipe-player’ (αὐλητοῦ βίον ζῇς).Footnote 148 Many musicians doubtless struggled to make ends meet (another proverb speaks of the poor as having a ‘piped out life’ (βίος ἐξηυλημένος) as though worn out by piping for a living).Footnote 149 The music industry was, and always has been, a high-stakes business. But the risk of failure was offset by the promise of immense riches. Juvenal sneers at the upward mobility of professional horn-players (cornicines) – ‘the permanent followers of country shows, their rounded cheeks a familiar sight through all the towns’ – who, despite their humble origins, had attained a status rivalling members of the municipal aristocracy. Having started out accompanying gladiatorial shows, they had now accumulated the resources to produce gladiatorial shows in their own name (‘after all, they’re the type that Fortune raises up from the gutter to a mighty height whenever she fancies a laugh’).Footnote 150 Exaggerated though this description may be, there is no question that some musicians were extremely well paid: in the time of Martial, the citharode Pollio earned enough money to purchase a luxurious estate on the outskirts of Rome.Footnote 151

Like prostitutes, actors and gladiators, musicians aroused feelings of both intense desire and intense suspicion.Footnote 152 They were judged not only by the quality of the music they produced, but also by their physical beauty. This extended beyond the clothes they wore (although the musician’s costume was certainly integral to his or her aesthetic appeal).Footnote 153 As performers, musicians put their bodies on show for the titillation and gratification of Roman audiences.Footnote 154 With this public exposure came both celebrity and notoriety.Footnote 155 In his sixth satire, Juvenal imagines flocks of female admirers swooning over their favourite lyre-players, collecting their plectrums as souvenirs and even praying to the gods on their behalf.Footnote 156 Though Juvenal’s depiction is surely fanciful, it speaks to a general fixation in Roman discourse on the sexual potency of musical performers.Footnote 157 Enslaved musicians and dancers were especially prone to being objectified in this way, since their bodies were sexually violable by law. One of Martial’s Epigrams is devoted to a female slave named Telethusa, who was ‘skilled at performing lascivious gestures to Baetican castanets and dancing to tunes from Gades’.Footnote 158 Similarly, in Statius’ representation of a theatrical spectacle during the reign of Domitian, ‘the cymbals and jingling Gades’ (cymbala tinnulaeque Gades) provide the soundtrack to the dancing of ‘Syrian troupes’ (agmina Syrorum) and ‘buxom showgirls from Lydia’ (Lydiae tumentes). Lest we be left in any doubt about the sexual availability of these foreign starlets, we are assured by the poet that their services are ‘easily bought’ (faciles emi).Footnote 159

It is little surprise, then, that Roman elites came to associate musical expertise with extreme social degradation. Upper-class Romans who spent too much time in the company of musicians, or whose skill at singing or playing instruments resembled that of a consummate professional, attracted a great deal of censure. Cicero’s comparison of the two individuals Valerius and Numerius Furius is indicative in this regard:

Valerius cotidie cantabat; erat enim scaenicus: quid faceret aliud? at Numerius Furius, noster familiaris, cum est commodum, cantat; est enim paterfamilias, est eques Romanus; puer didicit quod discendum fuit.

Valerius used to sing every day, and naturally so, being a professional; but our friend Numerius Furius sings when it suits him, for he is the head of a household and a Roman equestrian; he learnt what was appropriate when he was a boy.

Cicero does not actually state what occasions were ‘appropriate’ (commodum) for a Roman equestrian to sing: he simply took it for granted (and assumed that his readers would too) that a well-born citizen should know what kinds of musical pursuits were or were not acceptable for someone of Numerius’ rank. Suitable occasions for singing might have included banquets, religious festivals and weddings.Footnote 160 In his speech On Behalf of Murena, Cicero suggests that dancing was a natural accompaniment to a debauched feast and was allowable to the extent that it represented an occasional indulgence.Footnote 161 The key point here is that music was considered a luxury, not a pleasure to be taken at liberty; the serious duties of business and politics always came before the casual enjoyment of song and dance.

Although, in general, music-making seems to have been policed more strictly for men than for women, there are a few notable exceptions. Particularly revealing is Sallust’s criticism of the noblewoman Sempronia in his monograph on the Catilinarian conspiracy of 63 BCE. A notorious associate of Catiline, Sempronia is accused of ‘playing the lyre and dancing more elegantly than is appropriate for a respectable woman’ (psallere [et] saltare elegantius quam necesse est probae).Footnote 162 The commentary on this passage by the fifth-century Roman writer Macrobius is instructive: what Sallust objected to, Macrobius explains, was not the fact that Sempronia danced, but the fact that she did so ‘with aplomb’ (optime).Footnote 163 Again, what is at stake here is the idea that, while occasional singing or dancing was admissible in certain situations, a freeborn Roman should not aspire to professional levels of musicianship, especially if he or she was of aristocratic birth.

Roman responses to music were therefore conditioned by a variety of factors, including the cultural politics of Hellenism, conceptions of sound and its place within the urban environment, the perceived influence of music on the human mind and body, and the categorisation of music-making as an ‘infamous’ profession. Music pointed up a fundamental set of distinctions – between Roman and non-Roman, free and slave, elite and plebeian, young and old, male and female – which structured social relations and political discourses. For this reason, the study of music has much to offer the historian of ancient Rome.

Chapter Outline

The following chapters are framed around four substantive case studies, each focusing on a different period of Rome’s history: the middle Republic (Chapter 1); the late Republic (Chapter 2); the Augustan Principate (Chapter 3); and the Neronian Principate (Chapter 4). My decision to concentrate on these four periods was partly contingent on the availability of source material. We lack direct testimonies for Roman musical culture prior to the second century BCE; the evidence for the late Republic and early Principate, on the other hand, is relatively plentiful. However, there are also methodological reasons for adopting a narrower chronological focus. The narrative of this book opens in 167 BCE with a performance given by Greek musicians in Rome during the height of the empire’s expansion and ends circa 67 CE with a performance (or rather a series of performances) given by a Roman musician – an emperor, no less – in the heart of Greece. The reign of Nero seemed to provide a natural endpoint, in that it marked not only the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty but also the culmination of over two centuries of musical interaction between Greece and Rome, anticipating the cultural florescence of the Second Sophistic. Although I will draw on later sources where appropriate in order to support my arguments, a full discussion of Roman musical culture in the High Empire and Late Antiquity, taking into consideration the extensive corpus of early Christian writings on music, would require a very different set of sources and approaches from those employed in this book, and therefore is afforded only minimal treatment here.Footnote 164

Chapter 1 takes as its central focus the triumphal games given by the Roman praetor L. Anicius Gallus in 167 BCE. The chapter deconstructs Polybius’ hostile account of this event by exploring how he represents the role of music in the spectacle. The first part of the chapter examines how Anicius manipulated the musical dynamics of the spectacle in order to amplify the importance of his triumph. The second part uses the episode as a springboard for investigating broader developments in Greek and Roman musical culture during the second century. As well as discussing the general treatment of music in Polybius’ Histories, I consider how the dissemination of Greek musical culture during this period sparked a reaction from senior members of the Roman political elite, as evidenced by the fragmentary speeches of Cato the Elder and Scipio Aemilianus.

Chapter 2 looks at the role of music in the political contests of the late Republic. Taking Cicero’s discussion of music in the De Legibus as a point of departure, I argue that Cicero’s comments need to be seen against the background of major changes in the culture of Roman spectacle in the 50s BCE – most notably, the construction of Pompey’s stone theatre. Furthermore, the chapter identifies points of overlap in the critical discourse focused on musical entertainment and the hostile characterisations of the so-called populares. This collapsing of the boundaries between popular music and popular politics provides an important new angle on the political struggles of the late Republic.

Chapter 3 is devoted to the relationship between Octavian/Augustus and Apollo’s incarnation as citharoedus (lyre-player). The main contention of the chapter is that the Augustan period fostered a revival of music which resonated with and to some degree embodied a restorative political message. Not only did Augustus integrate images of Apollo Citharoedus into his own imagery (both in Rome and in the commemorative monuments around the gulf of Actium), but he also exploited harmonia as a metaphor for his newly established regime, imbuing musical rituals like the Ludi Saeculares of 17 BCE with powerful symbolic resonances. The chapter also makes a case for seeing Mark Antony’s use of music as a key part of a project to present himself through the symbolic language of Hellenistic kingship, against which Octavian in turn defined his own musical ‘programme’.

Chapter 4 examines the reign of the notorious musician-emperor Nero. The chapter offers a comprehensive survey of the ancient material relating to Nero’s performances, stressing also his important role behind the scenes as producer, composer and choreographer. Building on the recent ‘performative turn’ in Neronian studies, I argue that Nero used music not to satisfy some narcissistic or tyrannical bent, as has traditionally been maintained, but rather as part of a self-conscious strategy for the negotiation and representation of imperial power. Nero’s music-making responded to, and drew energy from, the cultural interests of both the ordinary Roman people and the young metropolitan elite. In this way, I suggest, Nero succeeded in creating and disseminating an original musical language, which repackaged elements of Greek culture into a distinctly Roman product optimised for popular consumption.

Finally, in the epilogue, I bring together the arguments of the four chapters in order to assess broader changes and continuities in Roman musical culture during the period under consideration. While the ideological frameworks underpinning musical discourses remained largely constant over time, and competing political actors continued to use music for their own ends, I show that the gradual evolution of Roman society and politics prompted new types of engagement with music. This has important ramifications for our understanding of Rome’s relationship with Greek culture, as well as the interactions between elites and non-elites.