In his sixteenth-century plague treatise, the physician Niccolò Massa provides the following sanitary guidelines:

Many people, from fear and imagination alone, have fallen to pestilential fever; therefore, it is necessary to be joyful … One should stay in a beautiful place, such as a bright home adorned with tapestries and other trappings, with scents and fumigations, according to one’s station and means. Or take a walk in a well-appointed garden, since the soul is restored by this. Furthermore, the soul gladdens in meeting dear friends and in talking of joyful and funny things. It is especially advantageous to listen to songs [cantilenas] and lovely instrumental music, and to play now and then, and to sing with a quiet voice, to read books and pleasant stories, to listen to stories that provoke moderate laughter, to look at pictures that please the eyes (such as those of beautiful and respectable women), to wear lovely and colorful silken garments, and to look at silver vessels and to wear rings and gems, especially those with properties that resist plague and poison.Footnote 1

To our modern eyes, Niccolò’s advice may not be legible as a medical prescription. Aside from a few notes that may resonate with us as “aroma therapy” or “music therapy” – which today are not medical commonplaces in any event – this passage of Niccolò’s plague tract seems to be no more than well-intentioned encouragement to “stay positive” or to “relax.” We may further be tempted to dismiss Niccolò’s caution against fear and imagination as a case of squeamishness. Certainly, his prescriptions elsewhere of what to eat and drink, and his recipe for a plague pill register with us as more serious advice – diets and drugs, after all, are the more recognizable touchstones of modern medicine.

On this point, Borges’s story about a Chinese encyclopedia that so delighted Foucault and “shattered the familiar landmarks of [his] thought” seems particularly apposite.Footnote 2 Borges writes of The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, which divides the animal kingdom into such inconceivable categories as “those that belong to the Emperor,” “those that are embalmed,” “those drawn with a very fine camelhair brush,” “those that have just broken the water pitcher,” and “those that, from a long way off, look like flies.”Footnote 3 “In the wonderment of this taxonomy,” Foucault writes, “the thing we apprehend in one great leap, the thing that, by means of the fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that … [But] what is impossible is not the propinquity of the things listed, but the very site on which their propinquity would be possible.”Footnote 4 Mutatis mutandis, to understand the propinquity of music, pills, stories, bloodletting, and well-appointed gardens in anti-pestilential prescriptions, as well as the connection between fear, imagination, and disease, we need to recover the very site of their propinquity – to retrace the anatomical map of the premodern body and the psychosomatic bond that held together its faculties.

Imaginatio facit casum

Music’s place in the pestilential pharmacopoeia rested on the tight bond between the premodern processes of perception and cognition, and the material body. The key here is the imagination, or the imaginatio, an internal sense faculty that is seated either in the front ventricle of the brain (according to Galen and Avicenna) or the heart (Aristotle). Broadly speaking, the imaginatio functions as a gateway between sense and intellect. When a sensible object is perceived by one or more of the external senses – sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch – a simulacrum of its accidental properties is taken into the inner senses.Footnote 5 This simulacrum would first enter the sensus communis (the common sense), which perceives and collates the incoming sensations. We owe our ability to perceive a well-cooked piece of steak by sight, taste, smell, and touch, for example, to the sensus communis. The sensus communis, however, cannot retain these sensations for long; otherwise, we would constantly perceive an object that is no longer there. Instead, the sensible forms are passed onto the imaginatio, a kind of memory that stores the sensations. If the sensus communis is like water – receptive of impressions, but ephemeral – then the imaginatio is like stone, more recalcitrant, allowing for more permanence. The imaginatio can pass sensations back into the sensus communis so that they can be perceived even when nothing is directly sensed. It is on account of this persistence of sensations that the imaginatio is often described as “vain” or “wandering.”Footnote 6

The imaginatio also serves as a seat for higher cognitive processes. One of these, the vis imaginativa, can combine and recombine the materials in the imaginatio to produce new forms, such as a two-headed man or a mountain made of gold. A healthy individual could imagine buboes on his or her own body through this vis imaginativa. Another power, the vis extimativa, extracts intentions and forms judgments upon the materials in the imaginatio based on either instinct or previous experience, giving rise to passions (variously termed “affections of the soul” or “accidents of the soul”); a dog fears the form of a stick, for example, or a patient the sound of a funeral bell on account of this process. Although we can roughly think of passions as “emotions,” these products of the imagination are not mere “mental states” nor do they merely create “mental illness” in our modern-day sense of the term. In the pre-Cartesian world, there was a psychosomatic two-way traffic by which the mind could affect physical health and vice versa.Footnote 7 In the Isagoge, Johannitius thus describes the relationship between the accidents of the soul and bodily health:

Sundry affections of the mind produce an effect within the body, such as those which bring the natural heat from the interior of the body to the outer parts of the surface of the skin. Sometimes this happens suddenly, as with anger; sometimes gently and slowly, as with delight and joy. Some affections, again, withdraw the natural heat and conceal it either suddenly, as with fear and terror, or again gradually, as distress. And again some affections disturb the natural energy both internal and external, as, for instance, grief.Footnote 8

The passions disturb the balance of humors and circulate inner vital heat, and such movements of heat within the body can have powerful consequences. Cautioning against the negative affections (especially fear) in his 1504 plague tract, Gaspar Torrella enumerates their negative effects:

Rage shall not come into the regimen of health. Fury, sadness, fretting, worry, and fear are also to be avoided, for in a state of fear, heat and the vital spirit move inward rapidly, and it corrupts, chills, dries up, emaciates, and diminishes the natural human state, for it freezes the entire body, dims the spirit, blunts ingenuity, impedes reason, obscures judgment, and dulls the memory.Footnote 9

In short, negative affects can make one sick and stupid.

In premodern medicine, these powerful accidents were classified under the category res non naturales (things that are external to, but nevertheless affect the body) in distinction to res naturales (all the things that constitute the human body, such as the humors, the elements, and the organs) and res contra naturam (diseases and their causes). The nonnaturals were generally six in number and included (1) air, (2) food and drink, (3) motion and rest, (4) sleep and waking, (5) repletion and evacuation, and (6) the passions. In theory, one could preserve or restore health by manipulating the nonnaturals; a carefully controlled regimen of food, drink, exercise, and passions can help stave off or even reverse illness. Niccolò Massa’s caution against imagination and fear was, in this respect, no mere squeamishness.

Occasionally, the matter of the body may adapt itself directly to the forms apprehended in the imaginatio. These perceived forms travel into the blood and imprint themselves onto the body, resulting in some potent somatic changes. In one of the earliest plague tracts to be issued after the Black Death, Jacme d’Agramont warns against a wayward imagination by recalling the common knowledge that the influence of a mother’s imaginatio is so great, “it will change the form and figure of the infant in [her] womb.”Footnote 10 So that there is no doubt regarding the power of the imagination, Jacme invokes the authority of the Bible:

To prove the great efficacy and the great power of imagination over our body and our lives one can quote in proof … the Holy Scripture where we read in Genesis chap. 30 that the sheep and goats that Jacob kept, by imagination and by looking at the boughs which were of divers colors put before them by Jacob when they conceived, gave birth to lambs and kids of divers colors and speckled white and black.Footnote 11

The effects of the imaginatio can be downright miraculous. The medieval mystic Margaret of Città-di-Castello (1287–1320), despite being blind, imagined and spoke of the holy family so fervently throughout her life that, postmortem, her heart was dissected and was found to contain three little stones, each carved with the Nativity scene: baby Jesus, Mary at the manger, and Joseph with a white dove.Footnote 12 Her habitual and concentrated meditation had etched the images of her imaginatio onto her very flesh. Biblical and hagiographical accounts aside, the power of the imaginatio is evident enough through everyday experiences: “Imagine someone eating a sour fruit,” Nicolas Houël writes in his plague tract, “and your teeth will ache and go numb.”Footnote 13 All things considered, the imaginatio is a potent sensory faculty. Not only can it “wander” over forms that are absent from immediate sensation, but it can also conjure formal hybrids “such as cannot be brought to light by nature,” according to Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.Footnote 14 Considering also the psychosomatic effects that the imaginatio may generate, we can begin to appreciate why the mere imagining of plague, regardless of whether calamity is actually at hand, was thought to be enough to bring on buboes.Footnote 15

The care of the imaginatio and the passions was therefore crucial during times of plague. To that end, the senses – gateways to the internal sensitive faculties and ultimately to the body – had to be safeguarded. Niccolò Massa warns against “lingering in dark and fetid places, gazing upon sick and dead bodies and other monstrous things, looking at dreadful pictures,” for they weaken and dispose the viewers to illness.Footnote 16 Similarly, Jacme d’Agramont advises that during such calamitous times, “no chimes and bells should toll in case of death because the sick are subject to evil imaginings when they hear the death bells.”Footnote 17 When plague broke out in Pistoia in 1348, civic authorities sought to control the soundscape of the city precisely for that reason. On May 2, a city ordinance was issued banning, among other things, town criers and drummers from summoning any citizen of Pistoia to a funeral or corpse visitation, under penalty of ten denari.Footnote 18 Furthermore, items ten and twelve of the ordinance state:

10. In order that the sound of bells does not attack or arouse fear amongst the sick, the keepers of the campanile of the cathedral church of Pistoia shall not allow any of the bells to be rung during funerals, and no one else shall dare or presume to ring any of the bells on such occasions, under the penalty of ten denari … When a parishioner is buried in his parish church, or a member of a fraternity without the fraternity church, the church bells may be rung, but only on one occasion and not excessively; same penalty …

12. No one shall dare or presume to raise a lament or cry for anyone who has died outside Pistoia, or summon a gathering of people other than the kinsfolk and spouse of the deceased, or have bells rung, or use criers or any other means to invite people throughout the city to such a gathering, under the penalty of twenty-five denari …

However it is to be understood that none of this applies to the burial of knights, doctors of law, judges, and doctors of physic, whose bodies can be honored by their heirs at their burial in any way they please.Footnote 19

It is possible that this initial prohibition did not gain much traction, since the authorities soon felt the need to increase the fine and totalize the ban. On June 4, this revision was issued: “At the burial of anyone no bell is to be rung at all … under the penalty of twenty-five denari from the heirs or next of kin of the deceased.”Footnote 20

If horrific sounds on the pestilential soundscape can have a negative effect on the imagination and the body, then joyous and harmonious music can conversely function as an anodyne. To counteract the effects of fear with joy (gaudium), or at least to distract the mind from vile imaginings, authors of plague tracts prescribe, time and again, socialization, games, storytelling, beautiful objects, and joyous music. Such prescriptions appear in the earliest of plague treatises. Responding to the Black Death, the Florentine Tommaso del Garbo writes,

Do not occupy your mind with death, passion, or anything likely to sadden or grieve you, but give your thoughts over to delightful and pleasing things. Associate with happy and carefree people and avoid all melancholy. Spend your time in your house, but not with too many people, and at your leisure in gardens with fragrant plants, vines, and willows, when they are flowering … And make use of songs and minstrelsy and other pleasurable tales without tiring yourselves out, and all the delightful things that bring anyone comfort.Footnote 21

Similar prescriptions can be found throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries across Europe. One German writer champions the use of stories and music, writing that they, along with “good hope and imagination” are “often more useful than a doctor and his instruments.”Footnote 22 With more elaboration, Johannes Salius advises,

Play the harp, lute, flutes and other instruments [Cythara testudo fistulae aliaque instrumenta musica pulsent]. Let songs be sung [cantilena], fables be recited, joyful stories be read, and the songs [carmina] of the lighthearted muse be played. Finally, let the space where you spend your time be clean and well-decorated. Let beautiful clothes, rings, belts, jewelery, and all sorts of other ornaments of gold, silver, and precious gems be worn, so that the soul may be uplifted by such cheerfulness.Footnote 23

The French doctor Nicolas de Nancel personally recommends that

[B]efore and immediately following meals, stay quiet and calm; some time after, take small walks, and refresh the spirit by some chaste activity. And in my opinion, I prefer music [la musique] to all else, if someone knows how to play the lute [toucher du luth] or some other instrument, just as I do. For it’s not a good idea immediately after drinking and eating to sing with force; for that much force incites the rheums, especially for those who are not accustomed to it.Footnote 24

Later, on the accidents of the soul, Nicolas advises:

It will be good to read the holy Bible or holy and notable stories; tell some fun tales without villainy; play games sometimes, such as aux eschecqs, à l’ourche, aux dammes, tarots, reinette, triquetrac, au cent, au flux, au poinct and other such games, which are well known through the jokester Frenchman Rabelais, the father and author of Pantagruelism. But play without choler, and with pleasure; not for high stakes or for greed … Also sing sweetly and melodiously some sweet spiritual song [chanson spirituelle], not crass words or songs of villainy that some drunk singers and musicians might belch or vomit up. Or play musical instruments, like I said before, for music greatly refreshes the spirit …Footnote 25

Writing in 1565, Borgarucci calls for “music (suoni), games, and comedies,”Footnote 26 and Giovanni Battista da Napoli likewise urges the use of games, music, song (suoni e canti), and stories to pass the time.Footnote 27 Numerous prescriptions of music, beautiful clothing, and gems with occult powers can be found into the seventeenth century.

A number of generalizations can be made about the medical prescription of music in these plague tracts. First, where music is mentioned, it is almost always within a discussion of the imagination and the accidents of the soul, sitting alongside other nonnaturals such as food, drink, exercise, and rest. Nicolas de Nancel’s description of music as a post-meal activity falls under his discussion of exercise and is therefore idiosyncratic in that respect. Second, although explicit references to music do not appear in every plague treatise, an overwhelming number of plague tracts do refer to the accidents of the soul. Therefore, even where music is not specifically mentioned, there is presumably still a place for it in the anti-pestilential regimen.

Third, recommendations for music often accompany suggestions of adorning a home with beautiful furnishings and decorations, and it is very often mentioned in the same breath as games, jokes, stories, and keeping company with a small coterie of close friends and loved ones. The authors thereby impart a sense of domesticity and seem to advocate music-making in private, rather than public, contexts. Nicolas Houël comes closest to this point when he writes that “keeping to yourself and being solitary is not good, but neither is being in a large crowd; find happy people and honest recreation, occasionally sing, play flutes, viols, and other musical instruments.”Footnote 28 A large part of the emphasis, therefore, falls on the idea of light-hearted and private sociability; the writers are not prescribing solitary contemplation, but rather active and intimate engagement.

Lastly, the writers used a variety of terms for music and music-making. While some such as “cantus,” “melodia,” “carmina,” and “harmonia” are very general and could refer to a variety of musics, others like “canzone,” “cantilena,” “toucher du luth,” and the references to “tripudium” imply lower genres of secular, amatory, and dance music. These genres, again, suggest social and even physical participation. Once more, Nicolas de Nancel’s specification of “chanson spirituelle” is idiosyncratic in this regard, as is the direct juxtaposition of high-minded activities (reading the Bible) with low-brow amusements (Gargantua’s games). This instance aside, the beneficial joy conferred by music was, from the medical perspective, meant very much to be a worldly one.

The doctors’ general consensus on the value of music in times of plague, however, did not go unchallenged. In an etiological paradigm where spiritual and physical health were intimately linked, religious authorities claimed at least equal, if not higher, stakes in the battle against disease. While clergymen found little to fault in the medical opinions on air, diet, surgery, or drugs, they were more ambivalent about the treatment of the passions – particularly with music and other “frivolous” delights. To expose the roots of the disagreement on musical healing, it might be helpful to consider the clinical case of the artist Hugo van der Goes and the ways in which music came under religious purview.

The Case of Hugo van der Goes (1440–1482)

According to the chronicles of Gaspar Ofhuys, a member of the Red Cloister near Brussels, brother Hugo suffered an episode of mental illness around 1480.Footnote 29 One evening, as Hugo was traveling home from Cologne, he began to complain to his companions that he was a lost soul destined for eternal damnation and became intent on suicide. When they reached Brussels, a prior was summoned to treat the tormented artist. Encouraged by the biblical story of David and Saul, the prior prescribed music to his ward:Footnote 30

[Prior Thomas], after confirming everything with his own eyes and ears, suspected that he was vexed by the same disease by which King Saul was tormented. Thereupon, recalling how Saul had found relief when David plucked his harp, he gave permission not only that a melody be played without restraint in the presence of brother Hugo, but also that other recreative spectacles be performed; in these ways he tried to dispel the delusions.Footnote 31

Although, by Ofhuys’s account, this course of treatment had little effect, it appears that Hugo, having likely completed some paintings after this episode, was not wholly incapacitated by his madness. Ofhuys goes on to explain that we could understand Hugo’s illness in two ways: “First, we may say that it was a natural sickness and some species of phrenitis.” This phrenitis, he suspects, was caused by the painter’s consumption of melancholy-inducing foods and strong wine, which further troubled the passions of his soul. Moreover, Ofhuys writes that we can also speak of his illness as divine and didactic providence: because Hugo is so exalted for his artistic gifts, God, not wishing him to perish, compassionately sent him the illness as a lesson in humility for everyone to learn.

Hugo’s case reveals a fluid interchange of terms and ideas between what is putatively religious and moral, and what is natural and medical. Prior Thomas treats the biblical story of David and Saul as a medical episode and draws from it a therapeutic precedent. The solutions he prescribes – melodies and recreative spectacles – are in turn also found in the doctor’s medicine chest. On his part, Ofhuys diagnoses Hugo’s illness in two separate, but not mutually exclusive, ways: first, in terms of regimen and humoral theory and, second, in terms of divine providence. The conflation of these two terms lies precisely at the heart of the premodern etiology of disease. The Hippocratic-Galenic system inherited by Renaissance doctors was built on a naturalist and pagan framework that, in its original form, took little account of the existence of divine illnesses.Footnote 32 In the encounter between this pagan naturalism and Christianity, ancient medicine was subsumed by the Christian church under God’s work.Footnote 33 The majority opinion held that God was the ultimate cause of diseases. As Penelope Gouk explains, “even the most progressive medical writers believed that new forms of plague and other virulent diseases recently visited on European society were divine retribution for sin.”Footnote 34 Although God could bring about such punishments directly through supernatural means, the usual assumption was that He worked through nature, inciting remote events such as the conjunction of celestial bodies and more proximate phenomena such as weather or natural disasters. And if God worked through such natural means, then medical intervention, using the medicine that God had placed on earth for our benefit, was a viable response to disease.Footnote 35

In this paradigm, Saul’s divinely imposed affliction and subsequent cure by music read like a prototypical script in etiology and medical treatment. It is not surprising, therefore, that exegetes of this biblical episode often conflate its spiritual and medical aspects. Nicholas of Lyra’s explication, for example, centers not on the moral or ecclesiastical aspects of the story,Footnote 36 but rather on whether the power of music can actually dispel demons. Because demonic influence works upon the brain and human perception, music, Nicholas argues, working upon those same faculties, can counteract its effects.Footnote 37 In some hard-line Renaissance naturalist interpretations, Saul’s “unclean spirit” was interpreted through the lens of humoral theory. A mid-fifteenth-century Bible owned by Borso d’Este, for example, depicted Saul, lying in bed, suffering from melancholy (the same diagnosis that Ofhuys applied to Hugo). Likewise, theologian Tommaso Cajetan asserted that Saul’s unclean spirit was really a melancholia that troubled him with sensory delusions.Footnote 38 This account of disease explains how Saul’s (and Hugo’s) illness could be both divine and natural and how, under these terms, music can enter this bifurcated model of disease. It is revealing that, in his Complexus effectum musices – a fifteenth-century compendium of twenty uses and effects of music – Tinctoris files the biblical story of David and Saul not under the fourteenth use of music – music to heal the sick – but rather under music’s ninth effect – its power to banish evil.Footnote 39 This is a particularly marked choice given that Tinctoris’s authority for music’s healing powers, Isidore of Seville,Footnote 40 interprets the biblical episode medically in the De medicina section of Etymologiae, as an example of music’s power to allay frenzy.Footnote 41 As Jones writes, Saul’s evil spirits are “preternatural, but if they are to have any influence on humanity it must be through actions which are subject to the laws of nature”; it follows that even diseases imposed by God can be treated through natural (and even musical) means.Footnote 42

Plague, like other diseases, fell within this bifocal etiology. The commingling of the religious and the natural in medical discourse is evident in all varieties of prescriptive plague writing throughout the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. It was openly acknowledged in many plague treatises that God was the primary cause of the affliction. Johannes de Saxonia provides one of the most succinct accounts of pestilential teleology in his fifteenth-century treatise:

God is the most remote cause of epidemic, the heavens are the more remote, the air is remote, the humor is near, putrid air is nearer, and the putrid vapor infused in the heart is the nearest … This is clear, for the cause is more remote when there are more intermediate causes between the agent and the effect, and the cause is closer when there are fewer intermediate causes. And between God and epidemic, there are many other intermediate causes, and there is nothing between putrid vapors of the heart and illness.Footnote 43

Because God sat atop the etiological chain, it was to Him that doctors ultimately had to defer. Such spiritual deference is frequently woven into medical discussions or, at the very least, bookends otherwise secular medical treatises. Nicholo de Burgo’s treatise opens with the caveat that “only Jesus Christ can heal” and that any healing is done with his help,Footnote 44 and Antoine Royet concludes his with an exhortation to prayers and confessions, along with a French translation of Psalm 91.Footnote 45

All of this is not to say, of course, that the intermediate and proximate causes of plague should be ignored in favor of divine intervention. In his survey of religious literature on the plague, Franco Mormando finds that, while some religious writers and preachers do prioritize spiritual answers over medicine, none of them counsel their audiences to simply disregard medical advice: “both forms of response, the spiritual sources say outright or imply, are to be attended to.”Footnote 46 There were numerous religious reasons that justified the use of temporal medicines. For one, to completely ignore available medical advice in favor of divine intervention is to spurn the magnanimity of God and to commit the sin of self-destruction. Additionally, as Ambroise Paré writes in his Traicté de la peste, medicine gives us the opportunity to glorify the Lord:

My advice to the surgeon is to not neglect the remedies approved by ancient and modern medicine. For as much as this malady is sent by the will of God, so it is by his divine will that the means and help are gifted to us by Him to use as instruments of his glory, looking for remedies for our illnesses, even in his creatures, in which he gave certain properties and virtues for the relief of the unfortunate. And He wishes us to use secondary and natural causes as instruments of his blessing. Otherwise, we could be ungrateful and spurn his beneficence. For it is written that the Lord gave the knowledge of the art of medicine to men in order to be glorified in its magnificence …Footnote 47

It was also thought that God grants medicine to man so that it might serve as a model for the therapy of the soul. The Franciscan preachers Bernardino de Busti and Panigarola, for example, both point out in their sermons on the plague that spiritual remedies have counterparts in the temporal ones; physical separation from infected places, for example, reminds us of the necessity of fleeing from sin.Footnote 48 Such a parallel between spiritual and natural medicine is sometimes evident in discussions of regimen. The doctor’s advice for moderation in things such as food, drink, passions, sex, and sleep had moral equivalents in the preacher’s caution against excesses such as gluttony, wrath, lust, and sloth. In such a scheme, humoral balance went hand in hand with spiritual cleanliness. It is rather meaningful, in understanding the parallels between natural and spiritual medicine, that priests were called “physicians of the soul.”

In the broadest terms, medieval and Renaissance Christians wove their inherited Hippocratic-Galenic medicine into a generally coherent model of disease and etiology that sees the natural world subsumed under divine providence. It can be said that, whether addressing the ultimate cause of plague by placating God or whether attending to the proximate causes such as the environment or the patient’s humors, priests and doctors labored ultimately toward the same goal. Yet this theoretical model of health belies the uneasy rift between the spirit and the flesh in Christian theology. This deep-rooted divide becomes particularly apparent in the details of some pestilential therapies: what is good for the body may not necessarily be good for the soul, and measures against natural afflictions may exacerbate spiritual ones (and vice versa). Music – with its sensuous and fleshly qualities called into question long ago by the likes of St. Augustine – and its relationship to the passions was one of the subjects that problematized the coherent surface of premodern etiology.

Temperate and Intemperate Mirth

Although most authors of plague treatises would have agreed that timor and tristitia were to be avoided, they did not all prescribe gaudium unequivocally. Some writers distinguished between two types of joy: a healthy, temperate, permissible kind and an excessive, harmful kind. In his plague treatise, Johann von Glogau spells out the medical consequences of the respective types:

It is said that joy, which is used against pestilence, is of two kinds, namely the permitted (permissivum) and the harmful (perniciosum). The former type of joy does not spread the plague, but greatly impedes it, for, by such joy, man is delighted and increases his vital spirits, and it should be both suitable and moderate. But harmful joy is that which is suddenly caused in man and infects and corrupts the vital spirits and occurs especially in women, who, sometimes on account of one strange thing or another, magnify so much in their vital spirits, that they lose such spirits and their life. Furthermore, fear harms and greatly weakens men, and sadness also consumes men.Footnote 49

In the same vein, Gaspar Torrella explains that “joy is to be used, but not excessively, because such excess induces fainting spells and sudden death.”Footnote 50 By extension, an excessive use of music can become unhealthy: as Nicolaus of Udine explicitly advises, attain joy “by means of cantilenas and other favorite melodies, but temper their use, for excesses are noxious, destroying the spirit and natural heat.”Footnote 51 With a different rationale, one Neapolitan writer encourages the use of music and stories (giochi soni et canti), but warns against too much happiness, for excessive laughter causes the inhalation of a great deal of corrupted air.Footnote 52 An excess of joy (and music), it turns out, is as detrimental as fear and sadness.

The prescription for moderation naturally invited moralizing from high-minded authorities who emphasized the idea of plague as an arm of divine punishment. From the religious perspective, they argue that music and other entertainments such as comedies, theater, and spectacles represent excesses and gateways to serious vices that are themselves the causes of plague. In the Jesuit Antonio Possevino’s 1577 tract Cause et rimedii della peste, et d’altre infermtà – which, despite its title, is nothing more than religious exhortation with very little medical content – the author provides five categories of plague-inducing offenses: (1) pride, arrogance, ambition, vanity, and blasphemy; (2) heresy; (3) theft, rapine, usury; (4) luxury and carnality; (5) music as well as other oft-prescribed delights:

The fifth cause of plague is that which is the cause of carnality and lust, that is immodest madrigals and canzones, lascivious dance, indecent familiar conversation, the extravagance of clothing, lewd literature … [and] the use of nude images in which under the pretext of artistic expression, the world is easily roused to every sordid from of concupiscence.Footnote 53

For Possevino, these entertainments lead to the luxury and the carnality that invite pestilential punishment. This suspicion against music and other entertainments circulated not only within plague treatises. According to the Golden Legend, a plague struck Rome in the sixth century because, after a period of clean living over Lent and Easter, the Romans broke their fast with unrestrained feasting, games, and carnival celebrations. The mistrust of music even became religious policy during the Milanese plague of 1576–1578. Carlo Borromeo instructed his priests to preach against immorality throughout the city, especially to the men guarding the city gates; vices to be avoided included sloth, dishonesty, theft, blasphemy, games, dancing, and singing.Footnote 54

If these temporal means for attaining gaudium could so easily lead to sin, then true happiness must be found with God. One plague-tract writer, who is otherwise mostly interested in the natural aspects of plague, repeats the oft-encountered advice to avoid the “negative” accidents of the soul, but provides a spiritual prescription. He writes, “Ire, sadness, worry should be avoided, and be joyful, honest, and in delightful company. One is always gladdened by making peace with God, for then, one will not fear death.”Footnote 55 Another writer advises, “Joy and happiness should be used to comfort the spirits. Similarly, through peace, good hope, meditation, and the worship of God, the fear of death would be diminished and wrath, worry, and sadness, greatly avoided.”Footnote 56 These writers graft together the religious aspect of plague writing with the medical. But at the joint of these two discourses lies a practical conundrum: should the imagination be turned away from illness and death altogether or focused on the preparation for the life hereafter? For Savonarola, the choice is clear:

The devil, when he realizes that you want to think about death, goes about provoking others to distract you from these thoughts; he sets it in the mind of your wife and your relatives as well as the doctor that they should tell you that you will soon recover and that you should not worry and that you should not think that this [illness] means that you will die.Footnote 57

The Dominican friar turns the doctor’s advice on its head. Where some writers might caution against the mere mention of plague, the hard-liner Savonarola condemns any optimism. Equally revealing is Giovanni Pietro Giussano’s report that, during the Milanese plague of the 1570s, Borromeo publicly denounced a finely dressed woman for her levity and sartorial ostentation, saying, “Wretched woman! thus to trifle with your eternal salvation, when you know not that this day may not be your last in the world!” The next morning, the woman died suddenly, and all who had witnessed Borromeo’s earlier rebuke felt, in Giusanno’s words, a “salutary fear.”Footnote 58

It is precisely on account of the roaming yardstick of what is permissible joy and what is excessive joy (and what is pernicious and salutary fear) that the place of music and other entertainments in the pestilential regimen was not entirely secure. In this regard, we can sometimes even discern contradictory impulses within the writing of a single author. If Savonarola and Borromeo were swift and explicit in their condemnation of earthly distractions, Giovan Filippo Ingrassia, the head medico of Palermo when plague struck in 1575, was more ambiguous and ambivalent. In his Informatione del pestifero et contagioso morbo, Ingrassia initially proposes salubrious merriment, but, caught up in his subsequent attack on secular music, concludes with a caution for sobriety.

Ingrassia first advises his readers to put aside their worries and to preserve their imaginations by being happy, dressing beautifully, wearing jewels, putting on gallantries, abiding in brightly lit places decorated with a variety of paintings, and by avoiding fearful thoughts of death.Footnote 59 Unlike other doctors, however, Ingrassia makes a fine distinction between the different temporal comforts and writes:

But we do not wish to follow what some say we should do in such times: attending banquets, enjoying pleasurable pastimes with friends, games, witty conceits, laughter, comedy, songs, music [canzone, musiche], and other such nonsense. As we continually witness, in this divine battle, many dying in the space of a few days, others from one moment to the next without confession or other sacraments (amongst whom are very close friends, relatives, or neighbors), carried off to be buried away from the churches in the countryside, having their possessions burned, and the whole world going to ruin; despite this, worse than irrational beasts, they expect to have as good a time as possible and a leisure-filled life … Who could be so fatuous and thoughtless, with no fear for his own life, witnessing daily so many who, despite diligence and extreme caution, are nevertheless being carried off by the contagion and unexpectedly dying? And finally, what blind mole could, in such a situation, be happy and carefree, mindlessly living like Sardanapalus?Footnote 60

Here, Ingrassia separates solitary pleasures such as inspecting pictures and wearing elegant clothing from social entertainments such as music and storytelling. He ends up inveighing against levity; solemnity and spiritual vigilance are imperative when sudden death is quotidian. Ingrassia then caps off his tirade with a warning from Horace: “Tunc tua res agitur, paries cum proximus ardet” (Your property is in danger, when your neighbor’s wall burns). So much for not worrying! A little further on in the treatise, however, Ingrassia returns to music and reaches a rapprochement of sorts. He writes, “Our music should be the organs of the church. And its music, the daily music of the religious, should be our songs [canzoni], leaving behind all sadness over deceased friends and relatives.”Footnote 61 In the end, Ingrassia concedes a little room for sacred music to temper the passions.

Two Settings of O beate Sebastiane

Within this milieu of mistrust toward music, is it possible to accommodate the competing demands of doctors and clergymen? Accepting Ingrassia’s concession to sacred music as a starting point, we turn now to a case study of two anti-pestilential motets by Johannes Martini and Gaspar van Weerbeke – O beate Sebastiane – with an eye toward the ways in which they balance both perspectives to provide salutary joy. The genre of the motet itself, situated between the austerity of the Mass and the frivolity of secular song,Footnote 62 carried both spiritual and temporal expectations.Footnote 63 Tapping into this bivalence of the genre, Martini’s and Gaspar’s works juxtapose topoi that offer temporal and spiritual comforts. In this mode of reconciliation, we can discern a resonance across different types of cultural outputs inspired by plague that likewise bring together the earthly and the heavenly.

First, a little background on the works and a justification for considering these motets together as a pair. The two works set the same prayer to St. Sebastian, one of the premier plague saints of the period (see Chapter 4 for the history of Sebastian’s cult). The source of the text is unknown. It is, however, remarkably similar to a number of prayers contained in plague tracts and is likely a commonly circulated prayer.Footnote 64 Agnese Pavanello has identified a gradual for a mass of St. Sebastian from which this text may have been derived: “O Sebastiane, Christi martir egregio, cuius meritis tota Lombardia fuit liberata a mortifera peste, libera nos ab ipsa et a maligno hoste.”Footnote 65

| Prima pars | |

O beate Sebastiane, miles beatissime cuius

precibus tota patria Lombardie fuit liberata a pestifera peste.

|

O blessed Sebastian, the most holy soldier, by whose prayers the entire land of Lombardy was liberated from the pestiferous plague.

|

| Secunda pars | |

Libera nos ab ipsa et a maligno ut digni

efficiamur promissionibus Christi.

|

Free us from that and from evil so that we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ.

|

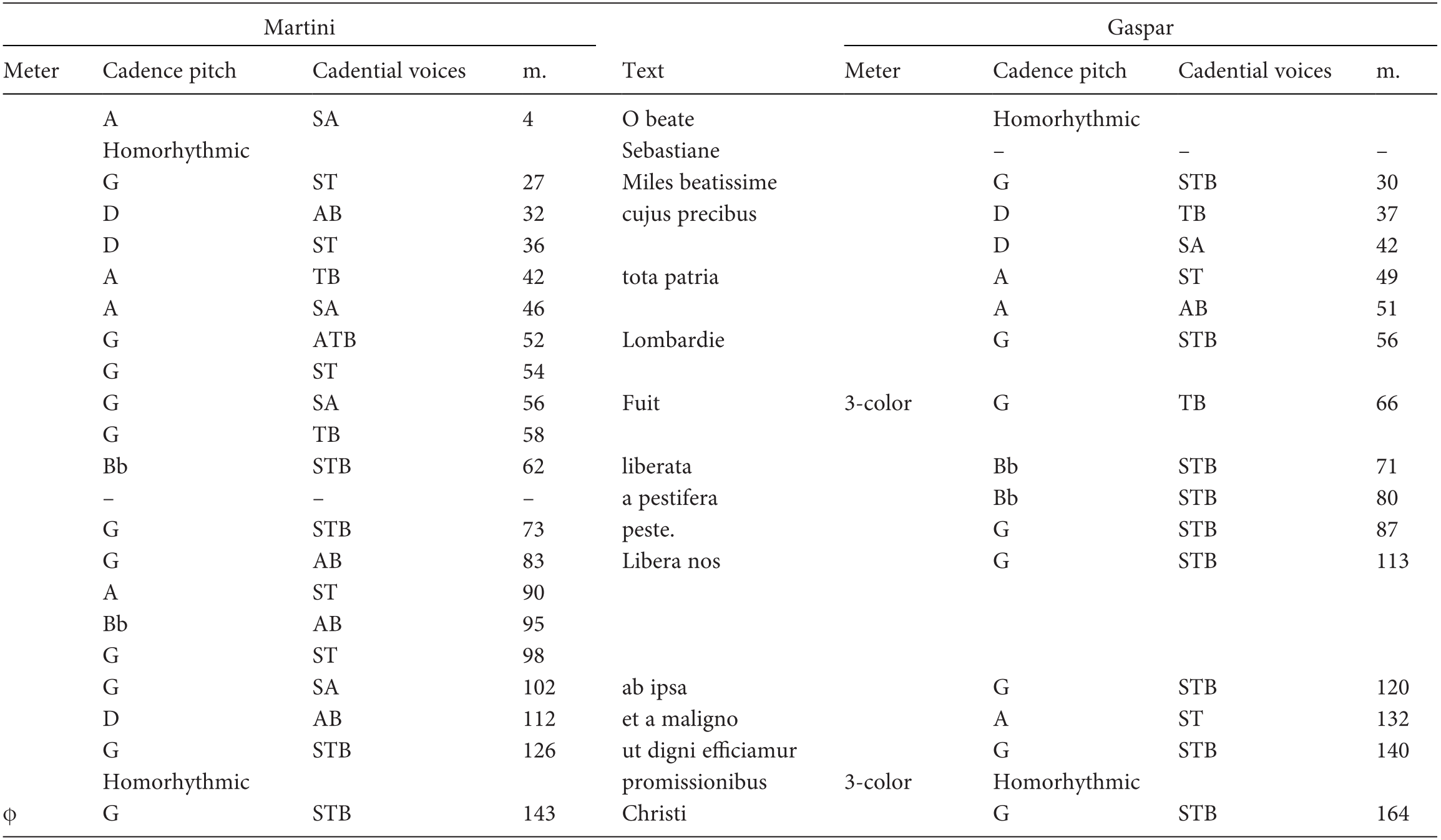

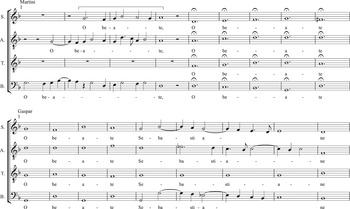

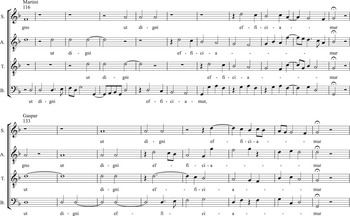

In addition to the use of the same text, there are a number of significant musical similarities between the two works. John Brawley has suggested the use of a common chant melody in the two tenors. “It is in fact,” Brawley writes, “the tenor lines which are primarily responsible for the similarities [of the two motets], and within the tenor lines the likenesses involve the structurally important tones, those most likely to be derived from a plainsong, rather than specifics of a more ornamental nature.”Footnote 66 The two tenors are indeed similar in their melodic fundaments; the openings and the melodic boundaries of each phrase match in almost every instance (see Example 1.1). The most marked difference comes in the “liberata” segment, where Gaspar’s melody is far more elaborate, and the cadential pitches are a third apart. The final pitches of the tenor phrases yield a similar polyphonic cadential pattern across both motets (see Table 1.1).

Example 1.1 Martini and Gaspar, O beate Sebastiane, tenors compared.

Table 1.1 Meter, texture, and cadential structures of Martini’s and Gaspar’s O beate Sebastiane compared

| Martini | Text | Gaspar | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meter | Cadence pitch | Cadential voices | m. | Meter | Cadence pitch | Cadential voices | m. | |

| Ο | A | SA | 4 | O beate | ₵ | Homorhythmic | ||

| Homorhythmic | Sebastiane | – | – | – | ||||

| Ϲ | G | ST | 27 | Miles beatissime | G | STB | 30 | |

| D | AB | 32 | cujus precibus | D | TB | 37 | ||

| D | ST | 36 | D | SA | 42 | |||

| A | TB | 42 | tota patria | A | ST | 49 | ||

| A | SA | 46 | A | AB | 51 | |||

| G | ATB | 52 | Lombardie | G | STB | 56 | ||

| G | ST | 54 | ||||||

| Ͼ | G | SA | 56 | Fuit | 3-color | G | TB | 66 |

| G | TB | 58 | ||||||

| Bb | STB | 62 | liberata | ₵ | Bb | STB | 71 | |

| Ϲ | – | – | – | a pestifera | Bb | STB | 80 | |

| G | STB | 73 | peste. | G | STB | 87 | ||

| ₵ | G | AB | 83 | Libera nos | G | STB | 113 | |

| A | ST | 90 | ||||||

| Bb | AB | 95 | ||||||

| G | ST | 98 | ||||||

| Ͼ | G | SA | 102 | ab ipsa | G | STB | 120 | |

| ₵ | D | AB | 112 | et a maligno | A | ST | 132 | |

| G | STB | 126 | ut digni efficiamur | G | STB | 140 | ||

| Homorhythmic | promissionibus | 3-color | Homorhythmic | |||||

| φ | G | STB | 143 | Christi | ₵ | G | STB | 164 |

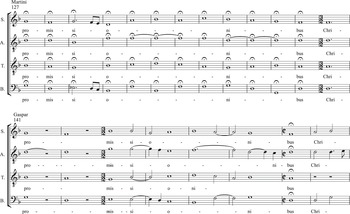

A number of additional shared musical features, however, cannot be accounted for simply by the use of common tenor melody and suggest direct modeling between the two works. In both motets, meter changes occur at “fuit liberata” and “promissionibus Christi.” The one instance where the final notes of Martini’s and Gaspar’s tenors do not agree (at “fuit liberata,” where Martini’s tenor ends on G and Gaspar’s on B♭), Martini nevertheless cadences on B♭, as Gaspar does. Texturally, the openings and endings (“Sebastiane” and “promissionibus”) are set to a succession of block chords in both motets (Example 1.2). More significantly, a number of contrapuntal structures are very similar (and in some cases identical) in both pieces: (1) the superius and tenor combination in Martini at mm. 31–34 creates a contrapuntal module – or an intervallic combination between multiple voices that is repeatedFootnote 67 – similar to that of Gaspar’s superius and altus at mm. 36–39 (Example 1.3). (2) An even more extended example occurs at mm. 49–54 in Martini and mm. 51–56 in Gaspar. In this instance, the module occurs between the same voices, superius and tenor. The two composers shaped the melodic profile of the superius voice from the tenor melody in very similar ways and combined two instances of the soggetto at the same time interval to create nearly identical counterpoint (Example 1.4). (3) All of the parts setting “ut digni efficiamur” are remarkably similar. Especially notable is the insertion of rests that break up the two parts of the text phrase – all voices in Martini, top three voices in Gaspar (Example 1.5). (4) Lastly, the chordal structures for “promissionibus” share a close affinity (mm. 127–138, mm. 141–147). The homorhythmic sections begin and end with identical chords, with the same voicing. In between, the same succession of sonorities occurs with different voicings (Example 1.6).

Example 1.2 Martini and Gaspar, block chords.

Example 1.3 Martini, O beate Sebastiane, mm. 31–34; Gaspar, O beate Sebastiane, mm. 36–39.

Example 1.4 Martini, O beate Sebastiane, mm. 49–54; Gaspar, O beate Sebastiane, mm. 51–56.

Example 1.5 Martini, O beate Sebastiane, mm. 116–126; Gaspar, O beate Sebastiane, mm. 133–140.

Example 1.6 Martini and Gaspar, O beate Sebastiane, “Promissionibus” chord reductions compared.

There are a number of factors that, taken together, suggest a Milanese origin for the motets. The first is textual: the prayer specifically mentions Lombardy (although it must also be noted that, rather than being a clue to the provenance of the works, this geographic marker may be a reference to Sebastian’s vita and cultic history; see Chapter 4). The second is biographical: both composers held posts in Milan. Gaspar spent the bulk of his career with the Sforzas over two tenures (1471–1480, 1489–1495), and Martini had a brief stay in 1474.Footnote 68 The third is stylistic. Both motets feature extended chordal-declamatory passages that bookend the works. Joshua Rifkin has found that, during the Josquin period, only Milanese works or works by composers associated with Milan feature successions of block-chords at either the very beginning or near the beginning of major sections.Footnote 69

Rifkin suggests two events in 1491 that could have occasioned a meeting of the two composers and spurred the composition of these works. There were two nuptials between members of the Este and Sforza families in that year (Martini would have been working for the Estes around this time). The wedding of Ludovico il Moro to Beatrice d’Este, which took place in Pavia on January 17, was celebrated in Milan on January 22, and the wedding of the Alfonso I d’Este and Anna Maria Sforza took place on January 23. While the subject of the motets had little connection to the nuptials, the works could have been written to celebrate St. Sebastian’s January 20 feast day, which fell between the two weddings.Footnote 70 It is also possible that these motets were a direct response to pestilence. Between 1481 and 1487, plague struck various parts of Lombardy, and Milan itself was particularly hard-hit between the years 1483–1485.Footnote 71 If the two motets were indeed composed in the mid-1480s, they would have spoken to the ongoing or recent calamity.

Certainly, too, plague must have been at the forefront of Ludovico’s attention as a result of his administrative work in the construction of a plague hospital during the late 1480s and 1490s. An idea for a lazaretto, located roughly 7 kilometers (5 miles) outside Milan in the town of Crescenzago, had been conceived during the rule of Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1466–1476), but the plans were shelved due to complaints of the town’s locals.Footnote 72 The latest bout of plague in the 1480s helped to revive those plans, with the lazaretto now relocated closer to Milan, at the Porta Orientale (currently the Porta Venezia). The cornerstone of the hospital, named San Gregorio, was finally laid in 1488. The 288-room, moat-separated compound opened in 1512, but was not fully operational until the Milanese plague of 1524.Footnote 73 Traditionally, the rulers of Milan were intimately involved in matters of state health,Footnote 74 and we know through extant letters that Lazzaro Cairati, the notary who first drew up plans for San Gregorio, was in contact with the duke during the construction of the hospital, asking him for design instructions. While we may never know the exact circumstances behind the composition of these motets, we can nevertheless imagine this cluster of events and concerns with which they may resonate.

Cantus jocosos

At the heart of these two motets, I would suggest, lies great healing potential. The exuberant melismas in both settings that accompany the idea of liberation (“fuit liberata a pestifera peste” and “libera nos ab ipsa”) sonically paint the idea of abandonment (see Examples 1.7a and b). In Martini’s setting, the superius even sings the word “peste” (mm. 68–73) on an ecstatic melisma that rises, with semiminim and fusa turns, through a twelfth, the entire range of its tessitura. The mood of celebration may be proleptic for the supplicants involved, but feeling of joyousness conveyed in these passages undoubtedly leads the imagination to better times. Moreover, the switch from duple into triple meter at the phrase “fuit liberata” further contributes to the joy of the passage (and “ab ipsa” similarly goes into a lilting triple time in the Martini setting). Bernhard Meier writes of such isolated triple-meter passages:

Episodic adoption of triple meter as a rhythmic peculiarity instead of the duple meter … used formerly can also act to express words. Passages in triple meter have an almost dancelike effect in comparison to the rest of the work. Consequently, they serve to express “joy” in general, but also depict events that are characteristically associated with dance: for example, to portray the term “wedding,” but also “idolatry” (think, for example, of the dance around the Golden Calf, also often represented in painting).Footnote 75

At the thematic level, the allusion to dance celebrates Sebastian’s miraculous work in Lombardy. But more than this, Martini’s and Gaspar’s topical reference is here not merely a description of joy but also a prescription for the supplicant singers and their listeners. Recall that doctors emphasized, time and again, the idea of sociability in their plague tracts, whether in playing games, telling stories, or sharing a laugh and a song. Although they are not always precise when it comes to pinpointing genres of music, they nevertheless give the impression that lower, secular, and social music was more suitable to the task. Thinking in these terms, one could argue that within the stylistic limits of the motet, Martini and Gaspar are here invoking the lower stratum of dance music, leading listeners to imagine gatherings of close friends or the joyous public celebrations that often accompany the end of plague. Considering, too, that both of these works were published by Petrucci and disseminated through the marketplace, we can also imagine the actual kinds of social performance situations prescribed by doctors that might attend the works’ salubrious gestures of joy.

Example 1.7a Martini, O beate Sebastiane, mm. 47–106

Example 1.7b Gaspar, O beate Sebastiane, mm. 51–120

It is also possible that the very use of triple mensuration itself could have had positive effects on the body. The connection between musical time and the passions had been recognized since antiquity and receives occasional mention in Renaissance music treatises. Zarlino, for example, urges composers in book IV of his Istitutioni harmoniche to choose rhythms that suit the subjects of their texts, using slow and lingering movements for tearful matters, and setting cheerful topics with “powerful and fast movements, namely, with note values that convey swiftness of movement, such as the minim and the semiminim.”Footnote 76 In his 1618 Musicae compendium, which draws on Zarlino’s Istitutioni harmoniche, René Descartes reiterates this connection between swift musical movement and joy. Descartes then extends the association of cheerfulness to triple meters as well, reasoning that those meters create more movement for the listener to attend to:

As regards the various emotions which music can arouse by employing various meters, I will say that in general a slower pace arouses in us quieter feelings such as languor, sadness, fear, pride, etc. A faster pace arouses faster emotions, such as joy, etc. On the same basis one can state that duple meter, 4/4 and all meters divisible by two, are of slower types than triple meters, or those which consist of three parts. The reason for this is that the latter occupy the senses more, since there are more things to be noticed in them. For the latter contain three units, the former only two.Footnote 77

Where Zarlino frames his discussion around the composerly problem of text–music relationships – matching the correct rhythmic movements with the correct subject matter – Descartes focuses squarely on listener response. Quicker rhythms and triple-meter music are appropriate not only for depicting happiness but also for directly arousing joy in audiences.

Similarly explicit connections between musical meter and psychosomatic responses were also made by doctors. In the 1586 Treatise of Melancholy, for example, Timothy Bright explains that sounds, next to visual stimuli, most affect sufferers of melancholy. Such melancholic ears, therefore, would greatly benefit from cheerful music,

of which kinde for the most part is such as carrieth an odde [i.e. triple] measure, and easie to be discerned, except the melancholicke have skill in musicke, and require a deeper harmonie. The contrarilie, which is solemne, and still: as dumpes [instrumental déplorations], and fancies, and sette musicke, are hurtfull in this case, and serve rather for a disordered rage, and intemperate mirthFootnote 78

For Bright, music in triple meter can incite happiness and act as a direct remedy for illness. Moreover, simple and “easy” music can have the same benefits for general audiences; musical experts, however, would require something more complex. Returning to the Sebastian motets, one may reason that the increased movement in the melismas and triple-meter text-painting at once describe and deliver a dose of joy, stirring the imagination to better humor (in multiple senses of the word).

But what of the austere chords that bookend the two motets? Bonnie Blackburn has termed such homorhythmic style of writing the “devotional style.” When found in Masses, these devotional chords most often set the vocative “Jesu Christe” or the word “Amen,” and in motets, they are often used for invocations, as they are here.Footnote 79 The topical reference may also be Eucharistic, given that chordal passages in motets – particularly in the Milanese repertoire – sometimes accompanied the Elevation during the Mass; “promissionibus Christi” may certainly hint at that sense. By Descartes’s and Bright’s accounts, the triple-time passages and the devotional chords in these motets would generate contrary passions in the listener, one arousing mirth, the other a sadness that dampens “intemperate mirth.” On a symbolic level, the juxtaposition of these musical topics – the dance and the prayer, the earthly and the spiritual – and their effects on the passions perfectly represent the competing demands of medicine and spirituality on the premodern patient.

Plague and the Carnivalesque

Several scholars have explored this uneasy juxtaposition between spiritual and temporal remedies in relation to other forms of pestilential art. Sheila Barker distinguishes between the “horrific memento mori” type of St. Sebastian images and the therapeutically beautiful type.Footnote 80 The former is exemplified by Andrea Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian (ca. 1506, Ca’ d’Oro, Venice), where the grimacing saint, pierced by a multitude of arrows, stands atop an inscription reminding the viewer that “nothing except the divine is stable; all else is smoke” (nil nisi divinum stabile est caetera fumus). The contour of one arrow, piercing him above his right knee, is even gruesomely visible under his skin. By contrast, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio’s 1500 Casio Madonna altarpiece (Louvre, Paris) shows Sebastian without any arrows and merely speckled with a few droplets of blood. Standing in a verdant countryside, his downcast gaze falls serenely on the Christ child. This and other similar depictions of St. Sebastian where his form is tranquil and his wounds are minimized offer salubrious sensual pleasures, not unlike being surrounded by precious clothing, metals, and gems.Footnote 81

Such pleasures can go too far, however. For Renaissance artists, the sensuous nude image of St. Sebastian often served as a platform for “one-upmanship” of artistic excellence. Vasari relates an anecdote of how Fra Bartolomeo responded to the frequent taunt that he was unable to depict nudes by painting an extremely attractive, borderline erotic image of St. Sebastian (in a near-transparent loincloth falling off his hips), earning praise from other artists. While the picture was on display in San Marco in Florence, the friars discovered via the confessional that women had sinned in looking at it, on account of its comely and lascivious realism, whereupon the painting was removed to the chapter house.Footnote 82 Other Renaissance Sebastian images were likewise so beautiful that they inspired moral apprehension in the climate of the Council of Trent. Caught up in the spirit of reform, Giovanni Andrea Gilio writes in his 1564 Dialogo … degli errori e degli abusi de’ pittori that the suffering of saints should be rendered truthfully, regardless of its gruesomeness. St. Lawrence, for example, should be shown on the grill charred and deformed, while Sebastian ought to be depicted with so many arrows that he looks like a porcupine – as in Mantegna’s image.Footnote 83 It was feared that beautiful nude images of Sebastian, much like bawdy music, had the potential to inspire improper lust (recall Possevino’s five causes of plague).

In a similar vein, Glending Olson argues that some plague literature closely reflects contemporary views on the health benefits of recreation. For example, the conceit of Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353) – ten young, well-to-do Florentines escape the plague-ridden city at the start of the outbreak of 1348 to various spots in the country to tell stories and play music – parallels medical recommendation to flee infected areas and to engage in social entertainments.Footnote 84 As such, Boccaccio’s scenario is not “merely escapist but therapeutic” – and therapeutic not only thematically, for the brigata, but also for readers who enjoy the stories.Footnote 85 Olson does not find the competing spiritual and medical demands on Boccaccio’s storytellers particularly problematic; after all, the brigata chooses to live “onestamente,” maintains decorum, avoids overindulgence, and uses storytelling properly, for pleasure and healthful profit. “The very act of intelligent listening (and, by extension, reading),” Olson writes, “becomes part of the shared values of propriety, harmony, and amity.”Footnote 86

But what of the stories they tell, the mordant ecclesiastical satires, the raunchy fabliaux, and the scatological farces that, on more than one occasion, leave the brigata breathless and aroused?Footnote 87 And what of Boccaccio’s apologies for these lurid tales and lewd language? In the epilogue, he insists that he is merely a dispassionate reporter of the tales told at the gathering, using common expressions of the marketplace. Furthermore, he insists, “It is perfectly clear that these stories were told [not] in a church, of whose affairs one must speak with a chaste mind and a pure tongue … nor in any place where churchmen … were present.”Footnote 88 And finally, Boccaccio warns, “The lady who is forever saying her prayers, or baking pies and cakes for her father and confessor, may leave my stories alone,” and “If it should cause [the readers] to laugh too much, they can easily find a remedy by turning to the Lament of Jeremiah, the Passion of Our Lord, and the Plaint of the Magdalen.”Footnote 89 Reading between the lines of his apology, we may suspect that his stories reach so low that they may do more harm than good.

Within this rift between the high and the low, the permissible and the excessive, the official and the unsanctioned, Bakhtin finds a spirit of the carnivalesque. He writes of Boccaccio’s conceit, “The plague in his conception … grants the right to use other words, to have another approach to life and to the world … Life has been lifted out of its routine, the web of conventions has been torn; all the official hierarchic limits have been swept away … Even the most respectable man may now wear his ‘breeches for headgear.’”Footnote 90 During this loosening or suspension of normal time occasioned by plague, Boccaccio trots out the lower bodily stratum – images of the material body and its gross and festive acts – to create a laughter that is at once creative, healing, and regenerative, but is also antithetical to the intolerant seriousness of the church ideology.Footnote 91 Colin Jones describes a similar function of plague time, from the religious perspective, writ large on the level of life itself: “In an odd way, plague is like carnival – another disruptive, subversive event that slips the bounds of conventional time and space, and another target for Catholic moralizing … Indeed anyone who can seek out fun in these conditions is seen as extraordinarily contemptible.”Footnote 92

From the records of plague chroniclers, who either praised the heightened virtue of a city or denounced its marked moral decay, we can see that the spirit of carnivalesque inversion seemed to have infected the moral lives of citizens as well. Alessandro Canobbio, for example, was particularly impressed by the Veronese; when plague struck in the 1570s, concubines of the city “left one another and returned to their legitimate partners, other sinners changed their ways, and many enemies voluntarily made peace.”Footnote 93 The situation in Milan was quite the opposite during the same outbreak, according to Olivero Panizzone Sacco, who complained of sex, games, dancing, excessive feasting, adultery, and other sins committed throughout the city, behind closed doors and even in the city’s lazaretto.Footnote 94 An account of San Gregorio by its warden, Fra Paolo Bellintano of Saló, confirms Sacco’s claims. He describes an incident at the plague hospital thus:

One night the inmates were staging a dance, in order to cheer themselves, keeping the event secret even though I forbid all such activities. The day before, brother Andrea had recounted to me that he had seen among the cart of dead bodies a very old woman, and knowing about these festivities, he planned to instill a bit of terror among the dancers. He went that night to the pit in the middle of the lazaretto where they threw corpses, and searching among them diligently, finally found her again. Hoisting her on his shoulders, her stomach stretched taut forcing air in her gut out through a great belch from her mouth. Who wouldn’t be frightened of such a thing? Not our Andrea. He said in our language [Brescian dialect], “Quiet old girl, we’re going to a dance.” And he went into the room, knocked on the door, and announced, not as friars do with “God bless,” but in local [Milanese] dialect, “Let us in, we’ve come to party!” When they opened the door, he hurled the body into the middle of the room saying, “Let her dance, too.” Then he added, “Is it really possible you will stay here debauching, offending God, when your deaths are so close at hand?” And he told them other such things and then left. The dance ended.Footnote 95

This grotesque tale of a ball of the infected illustrates many of the characteristics of the Bahktinian carnival: the laughter and the festive impulse of the inmates; the spectacularly disgusting lower bodily stratum of the corpse as fodder for shock and comedy; and the Christian moralizing of a killjoy friar. For the patients at San Gregorio, staging such a joyous and social event “in order to cheer themselves” is exactly what the doctor would have ordered. But this earthly laughter is wholly offensive to the Christian ideology, with its nagging emphasis on death and the afterlife. In life and in art, plague serves as a site where the earthly and the spiritual meet, at times placing incommensurate demands on both the lower and the upper bodily strata.

Just as these competing demands from the doctor and the priest leave their marks on pestilential artworks such as the St. Sebastian images (salubrious beauty versus frightful memento mori) and the Decameron (raunchy stories versus pious decorum), they likewise shape the very contours of Martini’s and Gaspar’s motets. The pious homorhythmic openings of the two works resist, but eventually break down into a laughter that is earthly, bodily, and carnivalesque. Dancelike triple-meter writing, uplifting tunefulness, and exuberant melismas in the middles of the motets convey a joy squarely at odds with the sobriety demanded by the preacher. Dance, as we have witnessed in the Milanese lazaretto, has a very real potential to upset ecclesiastical order. Recall Meier’s description of celebratory, triple-meter music, his reference to both “wedding” and “idolatry” points to the bivalence of dance, from the legitimate (a community celebrating a marital bond) to the subversive (heretical revelry). This bifocal view of the dance topic resonates with Renaissance suspicion of dance itself. In a tract attributed to Carlo Borromeo in which he condemns dance and comedies, the cardinal distinguishes between two types of dancing referenced in the Bible. The first is inspired by the Holy Spirit and comes from “a movement of grace,” exemplified by David’s dance in the presence of God. The second is based solely on pleasure – witness the lascivious dancing daughters of Sion depicted in Isaiah 3:16 – and is utterly offensive to the Lord.Footnote 96

But for all of Martini’s and Gaspar’s evocations of dance, joy, and laughter, theirs are sacred and prayerful songs, not lascivious madrigals or canti carnascialeschi. Here, the laughter points to the lower stratum, but never becomes wildly immodest. Although the eruption of dancing in these motets gesture toward “degradation” in the Bakhtinian sense – a “coming down to earth” and an emphasis on the material body – this degradation is not intent on rapturous blasphemy, but rather on bodily health. At the end of the motets, homorhythmic declarations of “promissionibus” cordon off the festivities and re-establish a sense of solemnity. These devotional-elevation chords complete the works’ textural symmetry, enveloping the works with high-minded devotion – a final turn, then, to the Passion of Christ, lest we laugh too much. Through the course of the works, we move between degradation and elevation, between our physical dancing bodies and Christ’s metaphysical Eucharistic body. The works offer, in essence, both the chanson spirituelle and Gargantua’s entertainment prescribed by Nicolas de Nancel. Such a juxtaposition of topics betokens the motets’ (and the Motet’s) capacity for achieving a rapprochement between spiritual and temporal medicines. The messy juxtapositions of the medical and spiritual prescriptions are still very much present and heard, but Martini and Gaspar have combined their respective prescriptions for a double dose of medicine that treats the body and the soul.