13.1 Introduction

In Chapter 11 we saw that human beings have a part to play in mediating divine providence into the empirical world. But to play this role involves a crucial duality within the soul: a capacity for knowledge (of forms) on the one hand, and for perception and opinion (of empirical objects) on the other. And these two capacities are difficult to keep in balance. Many people, indeed, effectively ignore their intellect and pass their lives quite unaware of the existence of forms. Those who recognise the significance of intellect may find that it is hard to build its exercise into their everyday routine, and that the ideal of the so-called ‘contemplative life’ (a life which draws its purpose and value from contemplation of the forms) is actually at odds with the demands of the ‘practical life’ (a life of engagement with the empirical world and which, in the absence of contemplation, even finds its purpose and value there). The proper appreciation both of the limits of thought about the empirical world and of the nature and significance of contemplation is central to Platonist anthropology, and vital for Platonist ethical theory.

13.2 Shortcomings of Empiricism

The question of how thinking about forms relates to thinking about the empirical world is one that we started to address in Chapters 8 and 9. Is empirical thought merely a degraded form of intellection, or does it have independent roots?

It is a common view of Plato’s own mature epistemology that he thought something like the former: that is, that our ability to make sense of the empirical world is not just based on our possession of a soul whose essence is, as a matter of fact, shaped somehow by the forms, but that in order to think about the world at all we need to invoke the forms – even if we do so unconsciously. This involves the mechanism of ‘recollection’, the idea being that all of our concepts (i.e. the mental categories into which we sort our empirical experience and make sense of it) are, whether we realise it or not, in fact dim traces or ‘memories’ of the forms. The argument goes that, when we ‘acquire’ an empirical concept, for example ‘green’, it is because our encounter with certain features of the empirical world sparks a distinct ‘memory’ of a putative form ‘Green’ which our soul must have encountered on some earlier occasion. (As we saw in Chapter 9 Section 9.6, this becomes an argument for the pre-existence, and ultimately the immortality, of souls.) Most people of course never interrogate this process closely enough to realise that the acquisition of the concept is an act of recollection like this, and for that very reason they are not motivated to make the effort to move beyond the empirical concept (the ‘recollection’) to recapture that of which it is memory. But if there had been nothing there to recall, if the mind had been what empiricist philosophers such as the Stoics liked to call a ‘blank tablet’ (e.g. SVF 2.83 = LS 39E.1) and nothing more, the empirical experience of something green would have had no purchase on it. It turns out in fact that our acquisition of empirical concepts involves something like a remote and shadowy contemplation of the forms.

There is some prima facie evidence that Platonists were indeed thinking along these lines. A number of texts, namely, seem to make the point that our raw empirical (sensory) experiences do not have the regularity or consistency to carve clear conceptual divisions into the mind: M, O; 9Kk[3]. Empiricists say that we acquire our concepts by repeated experiences of particular sensibilia; but do we in fact ever experience the same quality twice – or do we rather rely on some prior mental capacity in order to be able to conceptualise qualities as similar, and bring them under the same heading? (The Stoics, who were radical empiricists, might be especially vulnerable here because they were also nominalists, and believed that no two qualities could in fact be identical or even, at least in principle, indiscernible: see LS 40 J.6–7.)

Despite this opening, however, it seems certain that Platonists did not all (or did not always) deny the possibility of an empiricist foundation for some form of cognition. For one thing, they had to explain the cognitive abilities of animals, which are evidently able to make systematic empirical discriminations in the world around them, and more generally to learn from experience. Even those Platonists who believed that animal souls were essentially rational might have fought shy of claiming that animal cognition involved ‘recollection’. (Those who denied that they were rational would not have this available as recourse at all.) But something more fundamental to their own metaphysics prevented Platonists from linking all cases of concept-acquisition to recollection. It might be possible to construe Plato as having posited ideal correlates for sensibilia; but Middle Platonists did not take him this way. As we saw in Chapter 5, their belief was that forms corresponded by and large only to natural species. There is certainly no form ‘Green’. But that means that our ability to develop a concept of ‘green’ can have nothing at all to do with recollection: it must be entirely based on our empirical experience. But if experience can get us to concepts of all empirical properties – and, presumably, the way they are regularly ‘bundled’ in the natural world (see Chapter 8 Excursus) – then there seems to be no principled objection to the possibility that humans could develop a fully articulated mental apparatus capable of successful pragmatic discrimination, and of underwriting a fully rational life, purely by the mechanisms of empiricism.

This does not mean that Platonists are going to be content with empiricism, however. Empiricism might be pragmatically successful and it might allow us to live rationally; in short, it might underwrite a successful shot at the (merely) ‘practical life’. But there would be no guarantee that it would be a well-grounded life, in just the sense that there would be no guarantee that the concepts on which it was based had any factive authority. 9Kk[3], then, which at first glance appears to suggest that all concept-formation involves recollection in fact allows that we could acquire concepts empirically, but with the qualification that they would be fallible and defeasible. So the argument is precisely that ‘learning’ – which must here be taken as a success-term: the acquisition of reliable and accurate concepts – is recollection, not that all concept-formation is. M likewise should not, after all, be read as an attack on the possibility of empirical concept-formation, but rather as an attack on the idea that empiricism could provide stable foundations for epistemically privileged claims about the world. To live this way is precisely to live as animals do (see again 10X): successfully enough, but not with anything that could count as well-grounded understanding.

It is in the light of these considerations that we can see why some Platonists thought that the scepticism of the Hellenistic Academy was justified in some measure: not, of course, insofar as the claim might have been that knowledge is actually impossible, but very much so if one considers it as a reaction to the claims of Stoics and Epicureans to find empiricist underpinnings for knowledge. Read ad hominem, the arguments of the Sceptical Academy amount to a demonstration that empiricism, even if it can guide practical choice, can never lead to knowledge – something with which Platonists can cheerfully agree. (The debate between someone like Plutarch, who thinks that the New Academy was a legitimate part of the Platonist tradition, and those, like Numenius, who believe it to be a betrayal of Plato – see above Chapter 1 with Note 3i – is largely a debate over whether the Academics themselves intended their arguments to be purely ad hominem in this way.) Without a grasp of the forms, there is no justification at all for confidence in one’s empirical concepts: none that they correspond to real features in the world in the first place, and none that they are correctly applied to the articulation and understanding of particular empirical circumstances.

For Platonists, then, knowledge could only be found in the forms, whose contemplation in consequence is, or is the basis for, the best sort of life. But this leads to an important question. We shall see in Chapter 17 that Platonists build their understanding of the ethical end on a line of Plato’s that includes the exhortation to ‘flee the world’; but, as we have already seen in Chapter 9, our commission for the time being is to live in it and widen the diffusion of good through it. This is what raises the ethical question about how we are supposed to square the pursuit of contemplation with the calls of practical activity in the empirical realm; but first of all it raises a question of epistemology. To what extent, exactly, can contemplation of the forms improve the quality of our understanding of empirical matters, and affect our actions? Allowing that contemplation will never be able to elevate our empirical judgements to the status of knowledge, can it nevertheless help us to make better calls on the basis of our experience? Or (the more ‘pessimistic’ response) does it merely help us to achieve critical distance on the imperfections and uncertainties of the world, and serve to motivate our flight from it?

13.3 Theory 1: Anon. in Tht. and Alcinous

13.3.1 Knowledge and the Criterion

Anon. in Tht. is one of those who thinks that contemplation of the forms can improve our empirical judgements. B shows that he subscribes to the definition of knowledge (strictly, what he calls ‘simple knowledge’) in the Meno: ‘right opinion bound by an explanation of the reasoning’; and he goes on to make it clear that by ‘right opinion’ he means what the Theaetetus means by it. (The Theaetetus, as he says, fails to achieve a definition of knowledge only because it fails to add the idea of a ‘bond’ to the last definition it explores, right opinion with reason.) He specifies further that he is talking about items of knowledge such as ‘individual theorems which go to make up geometry and music’: C. But from the way this is connected with the Meno, and from the discussion of recollection, especially the fact that Theaetetus is the ideal interlocutor because he is someone capable of ‘recollecting’ (D), anon. evidently thinks that these items of knowledge are recollected. This means that he thinks that recollection feeds into our understanding of the world. Specifically, it provides the elements which go to make up a scientific framework and reference-point for the objects of our mundane experience.

Alcinous seems to think something similar. Rather like anon., he equates an object of recollection with what he calls ‘simple knowledge’ (A[6]), and although he identifies the domain of such knowledge as the ‘intelligibles’, he distinguishes ‘primary’ from ‘secondary’ intelligibles, characterising the latter as ‘forms in matter which are inseparable from matter’: A[7] (see Chapter 8 Excursus with Note 1b(i)). It looks very much as if recollection is being invoked here once again to give a scientific framework for understanding the world (in addition, that is, to leading us to an undiluted vision of the primary intelligibles which are distinct from it). Unfortunately for us, Alcinous does not gather this thought together with his discussion of ‘right opinion’, as anon. does. (Perhaps he prefers to keep the language of ‘opinion’ to particular empirical judgements – e.g. ‘this is Socrates’: see A[5] – while anon. is prepared to say that a person’s grasp of Pythagoras’ theorem, say, is also an ‘opinion’ of a sort.) But it looks very much as if he shares his underlying view. This impression is strengthened by the coda to Alcinous’ discussion, where he applies his account of knowledge to the field of ethics (see also 19E[2]). In ethics, he says, we do not make judgements of truth and falsity, but about what is appropriate or not appropriate: A[8]. But we make these judgements ‘by referring them to our natural concepts’ (which are objects of recollection, as we shall shortly see), ‘as to a definite standard of measurement’. So what we recollect informs our ethical judgements – just as, I suppose, our scientific understanding of the world in general informs judgements we might make concerning members of the various species.

In general, then, recollection on this theory informs and grounds certain of our judgements – not, to be sure, about whether this is Socrates, but, for example, what we expect in general terms from a human. One can operate in the world without it, but not with the scientific understanding that it allows.

13.3.2 Knowledge and Recollection

So much for what recollection is for on this theory. But what exactly will recollection lead us back to? The answer might seem obvious – the paradigm forms – but in fact the adherents of this theory appear to deny this: at least, they deny that the process of recollection can lead us back to a direct experience of the forms. Such experience, they claim, is only possible for the soul when it is out of the body: A[6]; cf. 2M; 17A[3]. During life, we only have available to us the memories of forms – memories which are what constitute the natural concepts: A[6], 9Kk[3]; cf. 14A[5.7].

Anon., for his part, is not so explicit that incarnate recollection is the recovery of memories rather than a road to direct cognition of the forms; but like Alcinous he describes recollection as a process of ‘unfolding’ and ‘articulating’ what he too calls ‘natural concepts’: D. It seems quite likely that he too thinks that these ‘natural concepts’ are psychological artefacts of our encounter with forms, rather than naming the encounter itself – just as empirical ‘concepts’ are psychological artefacts of our perception of sensibilia, and not the experience of perceiving itself.

If this is right, there are the beginnings of a correlation here; because Alcinous and anon. would be the only (Middle) Platonists we know of who make the point that recollection is the recovery of ‘natural concepts’ and also the only Platonists we know of who think that recollection supplies criteria for our mundane judgements – the only Platonists who think that our judgements can be improved and to some extent ‘grounded’ by the process of recollection. Is this any more than coincidence?

Perhaps not. One might, after all, wonder whether direct cognition of the forms would even be capable of doing the job that the recovery of memories of them does for Alcinous and anon. – that is, the job of providing criteria of a sort for empirical judgements. There are two potential obstacles to their doing this. The first is that a direct vision of the forms might simply distract us from the world – just as conversely, in the normal situation, our perception of the world distracts us from the forms. It seems odd to think that one can both be actively contemplating the forms and also applying them, instrumentally, to the assessment of empirical data.

But even if this were possible, it is not clear that the forms have the appropriate sort of commensurability with the empirical objects whose principles they are. Can one even in principle compare the objects we perceive with the forms we cognize, placing them as it were side by side? The answer ought to be ‘no’ if, for the reasons we have seen, forms lack empirical properties (Chapter 5 Section 5.3; cf. perhaps O). On the other hand, one might be able to imagine how memories corresponding to a previous experience of the forms, i.e. conceptualisations of the forms which we acquire through our experience of them, could work to provide a sort of bridge between our previous experience of the forms and our current empirical experience. There is no a priori reason why such conceptualisations might not be commensurable with empirical concepts, so that they can be criterial for them.

One might be tempted to think of the system of Alcinous and anon. (‘Theory 1’) as one with some formal similarities to Stoic epistemology. The hope of such thinkers, presumably, would be to mitigate the form of scepticism appropriate to the empirical world. Of course, we cannot have knowledge of it – only opinion (doxa); but one’s opinions can be better or worse, at least in the sense of being more or less well founded. And this is possible insofar as recollection gives us a mode of knowledge against which one can measure the deliverances of ‘opinionative’ reason (see A[2–3]), and distinguish those which are consistent with them from those which are not – just as Stoic ‘common concepts’ can be used as criteria for judgements (e.g. LS 40A). Naturally, Platonists do not go anywhere near as far as the Stoics, who allow (in principle) unshaken certainty to anything one might perceive; on the other hand, Alcinous and anon. can say that they improve on the Stoics by providing objective grounding for their ‘natural concepts’ which the Stoics are not able to do: Platonist natural concepts, namely, are grounded in our incorrigible prenatal experience of forms.

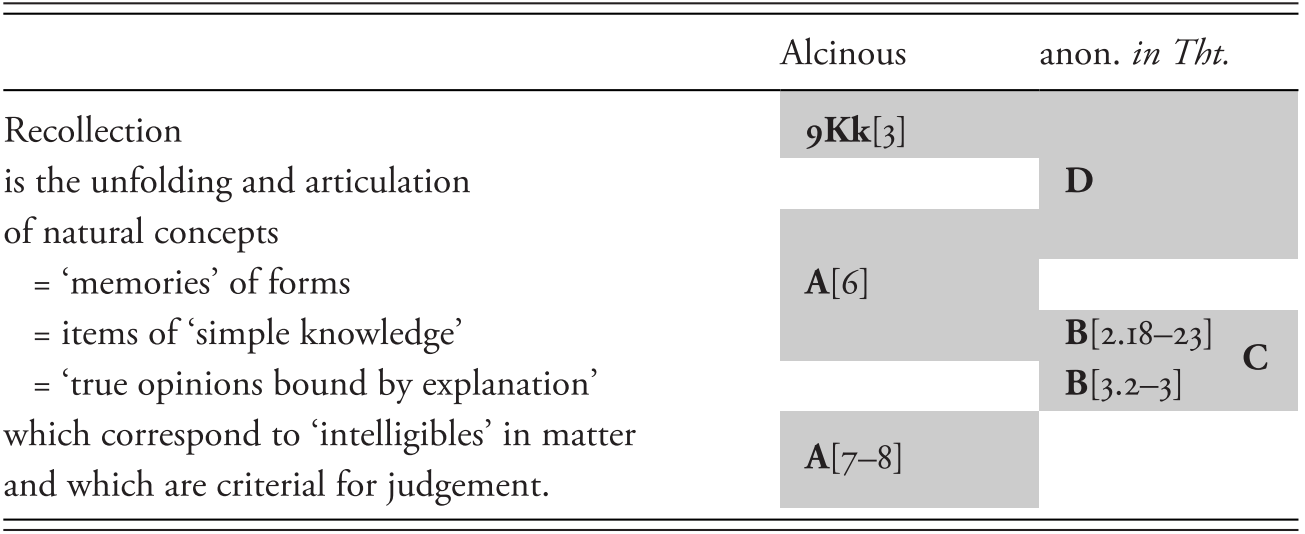

Table 13.1 Summary of ‘Theory 1’ in the evidence of Alcinous and anon. in Tht.

| Alcinous | anon. in Tht. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recollection | 9Kk[3] | D | |

| is the unfolding and articulation | |||

| of natural concepts | A[6] | ||

| = ‘memories’ of forms | |||

| = items of ‘simple knowledge’ | B[2.18–23] | C | |

| = ‘true opinions bound by explanation’ | B[3.2–3] | ||

| which correspond to ‘intelligibles’ in matter | A[7–8] | ||

| and which are criterial for judgement. | |||

13.4 Theory 2: Plutarch, Celsus, Numenius

13.4.1 Forms and Recollection

Whatever the advantages of Theory 1, it is not without its theoretical challenges. It wins for Platonism what one might think of as a more ‘optimistic’ epistemology (although that is of course a prejudicial way of putting it); and it might be an easier reading of Plato, especially the Phaedo, to say that we can only encounter the forms when outside the body. But at what price do these advantages come?

The problem here is to understand whether it is even coherent to talk about a ‘memory’ or ‘conceptualisation’ of a form. What, exactly, would such a thing be like? Precisely because forms lack empirical properties, they lack those attributes which one would expect to be needed if we were to acquire concepts of them which we could relate to empirical bodies. Indeed, one might think that cognition of forms is not, and cannot be, representational at all. Rather, there is some kind of union between our intellect and the form. It is, precisely, direct cognition. In fact, this is crucial to the role that forms play as epistemological absolutes: it is cognition through union that eliminates the possibility of doubt or mis-representation (see later Plotinus, Ennead 5.5.1). But if our cognition of forms is not representational, it is hard to see how it can be, or become, conceptual. One can easily argue that it should not be possible to have concepts of forms at all.

In this case, one might more naturally think that the way recollection works is that our experience of the empirical world challenges us to see that there must be non-empirical principles in terms of which the orderliness evident in empirical patterns is explained; recollection is, simply, the process by which we think harder and harder about the order in the world, and what these principles must be such that they explain it. The end-point of the process is not the recovery of a suppressed ‘memory’ or concept of the forms; it is the turning of our mind back towards the forms themselves. This construal of recollection seems much truer to the evidence for other Platonists, who do quite clearly talk as if we can get to see the forms themselves during life, albeit rarely and with difficulty. Notable examples are Plutarch (Q; cf. 9Aa), Celsus (P) and Numenius (O). It may of course not be coincidence that at least some of these people believe that the forms have a more intimate relationship with the constitution of the soul than we can assume for Alcinous (see Chapter 8 Section 8.5.2.2.2); or that the human intellect is precisely that part of the soul which is never ‘in’ the body at all (as Plutarch thinks: 9R).

13.4.2 Forms and Empirical Cognition

But notice what is lost. On this theory, the process of recollection cannot improve our empirical or practical judgements about the world. This is due to the problem of incommensurability that I raised before: one cannot assess sense-based judgements against the forms. And anyway, even the authors who talk of our seeing the forms during life think that we can see them only fleetingly – a fact which guarantees that they really are talking about what we can achieve during life, but also guarantees that our vision of the forms is not meant to underpin our ability to make sound judgements. (It cannot, for example, be the case that we can only make ethically well-informed decisions on those rare occasions when we glimpse the form of the good. Quite apart from anything else, the circumstances of concentrated meditation under which we can achieve these glimpses will tend to be circumstances when we are least likely to be called on for practical decision-making.) Of course the existence of the forms continues to guarantee and underpin the reality of cosmic order, and might to that extent guarantee the appropriateness of the empirical apparatus we acquire in our interactions with it. To that extent, the metaphysical system as a whole indirectly gives extrinsic validation to the full range of our judgements, a form of validation to which the Stoics, for example, cannot appeal. But it does not, in any case, affect the intrinsic quality of those judgements.

So what does recollection achieve for us? Under this theory, I suggest, its effect is to be understood within a broader ethical frame. Recollection of the forms, especially the form of the good, is essential to our ethical success and underpins it consistently – even though the experience of recollection itself might be limited and sporadic, and even though our vision of the forms cannot directly inform our ethical judgements. It does this because the epistemic content at which it aims is not what is important: what is important is the discipline and behaviour involved in the activity of recollecting. But a full account of this is something that will have to wait until Chapter 17.