Japan, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan, China are neighbouring high-income countries with some similarities in health systems policy. All three have historically organized publicly financed health coverage around the labour market, with the government paying for some or all of the costs of self-employed, retired or poorer people, but Japan has a much higher share of public spending on health and a much lower share of out-of-pocket payments than the other two. All three rely heavily on the private sector to deliver health services. And in all three, private health insurance plays a supplementary role, offering subscribers daily cash benefits in case of hospitalization or lump sum payments in case of severe illness such as cancer. Although private health insurance markets in these countries are marginal in terms of spending on health, they cover relatively large shares of the population.

This chapter reviews the origins and development of private health insurance in the three countries and considers why the market is not larger in terms of health spending, especially given the relatively high share of out-of-pocket payments in the Republic of Korea and Taiwan, China and the widespread use of cost sharing for publicly financed health services in all three countries.

Country case studies: Japan, Republic of Korea, Taiwan, China

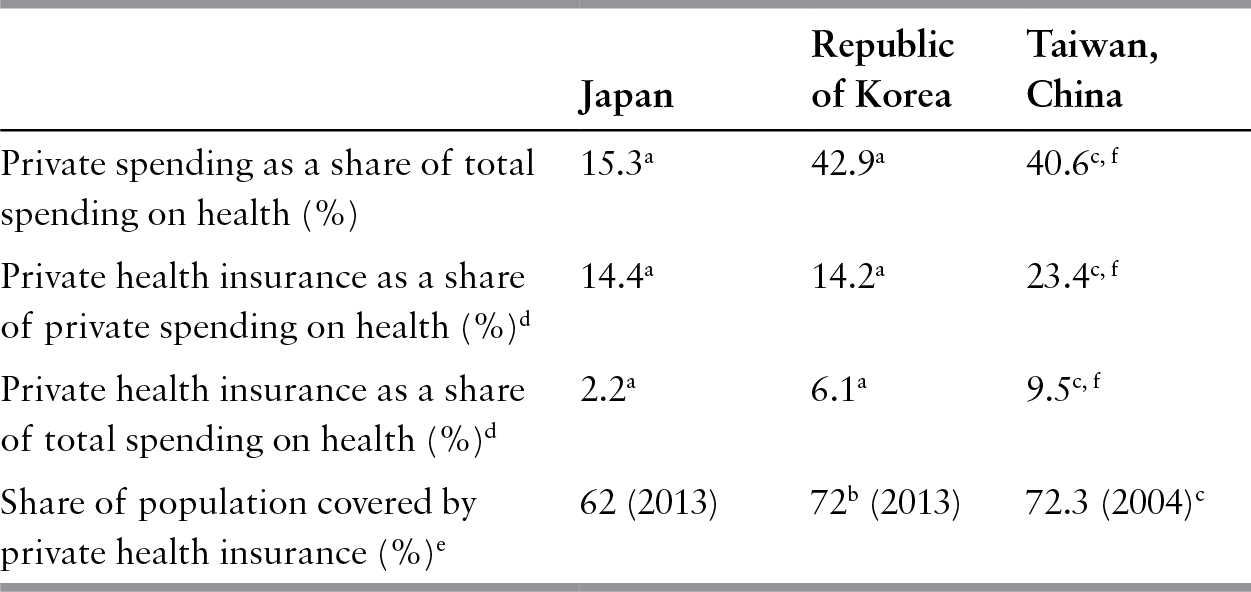

Public spending on health accounts for 84% of total spending on health in Japan and close to 60% in the other two countries (see Table 9.1). Consequently, the out-of-pocket share of total spending is lowest in Japan (13%) and significantly higher in the Republic of Korea (37%) and Taiwan, China (34.7%) (MOHW, 2016a; WHO, 2018), although in the latter two countries its share has fallen over time. Private health insurance accounts for less than 3% of total spending on health in Japan, around 7% in the Republic of Korea and almost 10% in Taiwan, China.

Table 9.1 Health financing indicators in Japan, Republic of Korea and Taiwan, China, 2015

| Japan | Republic of Korea | Taiwan, China | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private spending as a share of total spending on health (%) | 15.3a | 42.9a | 40.6c, f |

| Private health insurance as a share of private spending on health (%)d | 14.4a | 14.2a | 23.4c, f |

| Private health insurance as a share of total spending on health (%)d | 2.2a | 6.1a | 9.5c, f |

| Share of population covered by private health insurance (%)e | 62 (2013) | 72b (2013) | 72.3 (2004)c |

Notes: d Private health insurance expenditure data should be interpreted with caution because private health insurance seldom pays directly for health care. The cash benefits that it provides may not bear much relation to the actual health care costs incurred.

e Various years (see text). For Japan, the share of those having private health insurance has been calculated as 74% of the 84% who have life insurance policies (based on Association of Life Insurance, 2016).

f Because most private health insurance plans only provide cash benefits, only administrative costs (5.7 billion New Taiwan dollars or about 0.58% of total spending on health in 2014) of private health insurance are included in national health spending statistics. The share of private health insurance in total spending on health is calculated as the ratio of private health insurance benefit payments and total spending on health.

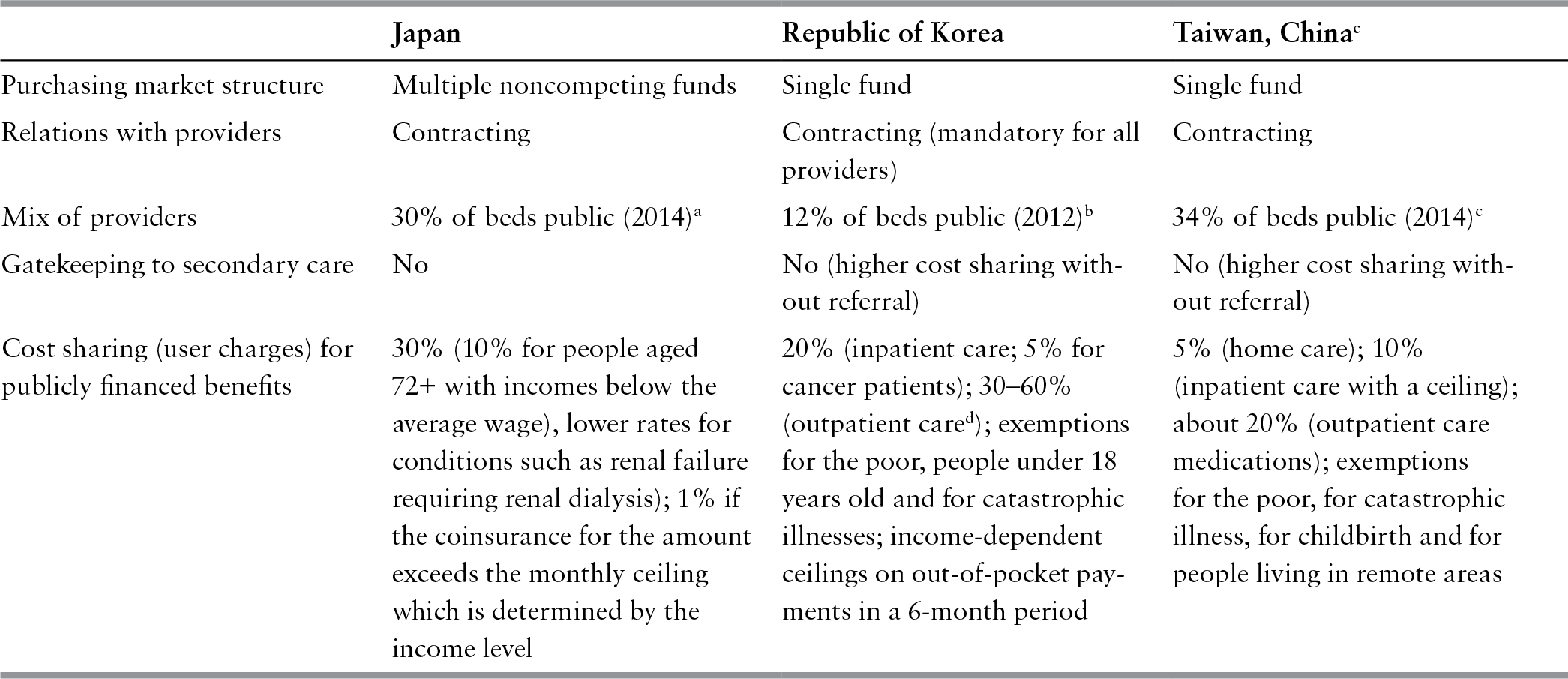

Publicly financed health coverage has historically been organized around employment, with substantial use of government transfers to cover the non-employed part of the population (see Table 9.2). While Japan uses multiple noncompeting health insurance funds to purchase publicly financed benefits, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan, China use a single, national health insurance fund. The private sector plays an important role in delivering health services. There is little gatekeeping by primary care physicians and fee-for-service is the most common form of provider payment.

Table 9.2 Organization of the health systems in Japan, Republic of Korea and Taiwan, China, 2016

| Japan | Republic of Korea | Taiwan, Chinac | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purchasing market structure | Multiple noncompeting funds | Single fund | Single fund |

| Relations with providers | Contracting | Contracting (mandatory for all providers) | Contracting |

| Mix of providers | 30% of beds public (2014)a | 12% of beds public (2012)b | 34% of beds public (2014)c |

| Gatekeeping to secondary care | No | No (higher cost sharing without referral) | No (higher cost sharing without referral) |

| Cost sharing (user charges) for publicly financed benefits | 30% (10% for people aged 72+ with incomes below the average wage), lower rates for conditions such as renal failure requiring renal dialysis); 1% if the coinsurance for the amount exceeds the monthly ceiling which is determined by the income level | 20% (inpatient care; 5% for cancer patients); 30–60% (outpatient cared); exemptions for the poor, people under 18 years old and for catastrophic illnesses; income-dependent ceilings on out-of-pocket payments in a 6-month period | 5% (home care); 10% (inpatient care with a ceiling); about 20% (outpatient care medications); exemptions for the poor, for catastrophic illness, for childbirth and for people living in remote areas |

Notes: d Depending on the type of health care facility: 30% for health clinics; 40% for hospitals; 50% for general hospitals; and 60% for high-level (tertiary-care teaching) general hospitals.

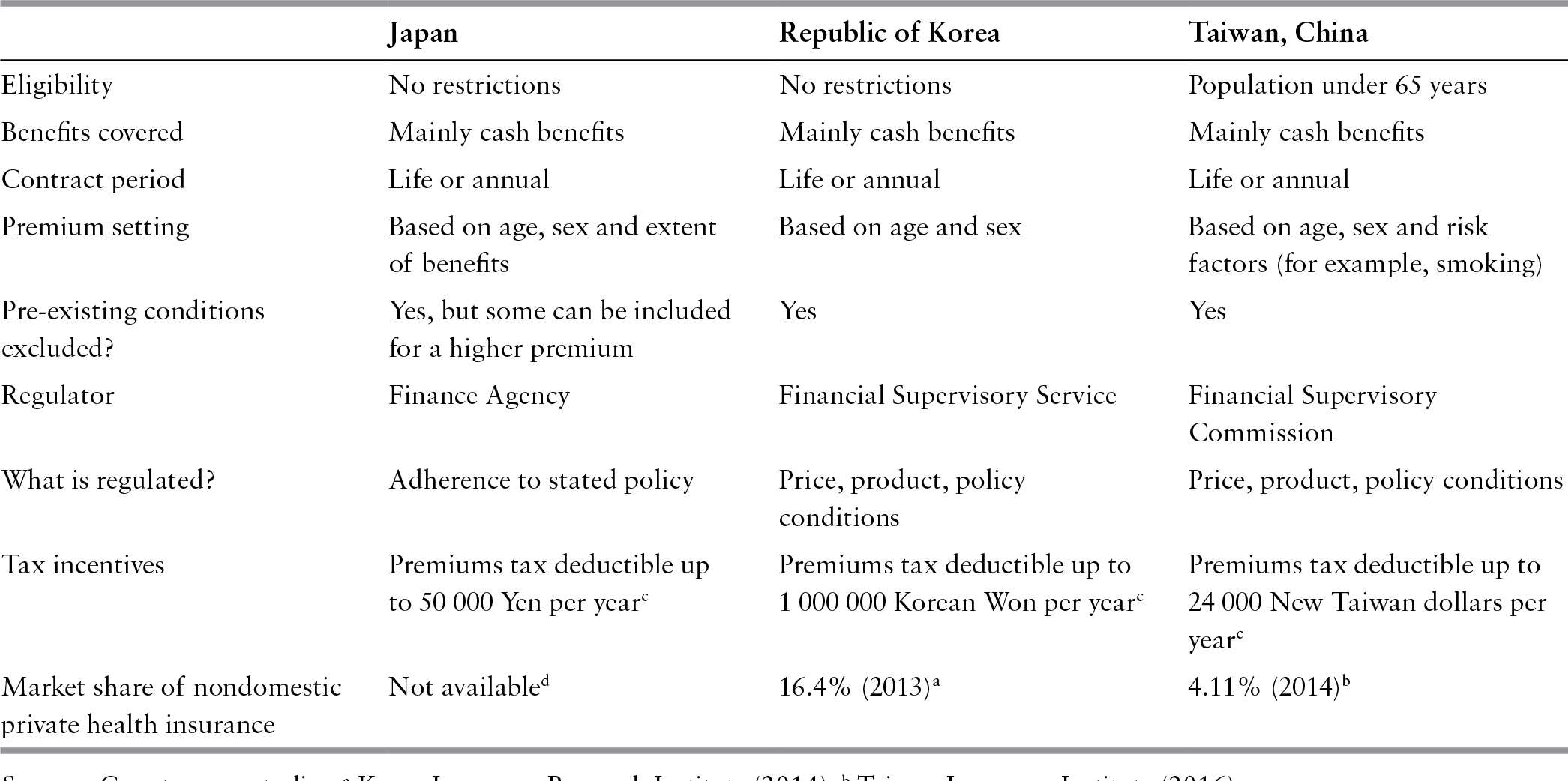

Private health insurance is sold as a supplement to life insurance or a stand-alone product. Plans typically cover inpatient services (including surgery) for cancer and other potentially high-cost conditions. Accident insurance also covers health care. Benefits are in the form of cash (see Table 9.3), usually lump sum payments in case of cancer or for a surgical procedure, per diem payments for hospital admission or per visit payments for follow up after hospital discharge or surgery. Cash benefits are seldom related to the cost of care and are usually lower than the actual cost incurred. Some private health insurance contracts are multi-year, investment-linked or interest-sensitive products, allowing subscribers to earn interest on their contributions; so they are used as financial instruments, not just for health protection.

Table 9.3 Key features of the private health insurance markets in Japan, Republic of Korea and Taiwan, China, 2016

| Japan | Republic of Korea | Taiwan, China | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | No restrictions | No restrictions | Population under 65 years |

| Benefits covered | Mainly cash benefits | Mainly cash benefits | Mainly cash benefits |

| Contract period | Life or annual | Life or annual | Life or annual |

| Premium setting | Based on age, sex and extent of benefits | Based on age and sex | Based on age, sex and risk factors (for example, smoking) |

| Pre-existing conditions excluded? | Yes, but some can be included for a higher premium | Yes | Yes |

| Regulator | Finance Agency | Financial Supervisory Service | Financial Supervisory Commission |

| What is regulated? | Adherence to stated policy | Price, product, policy conditions | Price, product, policy conditions |

| Tax incentives | Premiums tax deductible up to 50 000 Yen per yearc | Premiums tax deductible up to 1 000 000 Korean Won per yearc | Premiums tax deductible up to 24 000 New Taiwan dollars per yearc |

| Market share of nondomestic private health insurance | Not availabled | 16.4% (2013)a | 4.11% (2014)b |

Notes: c Applies for the sum of premiums of all types of private insurance, that is, not only for private health insurance. d Over 80% if restricted to cancer products.

Japan

Publicly financed health coverage

The current system was established in 1922 with the Health Insurance Act (Kenkou Hokenhou), which secured health services for employees – mainly blue-collar workers – and gradually expanded to cover other groups (Reference Campbell and IkegamiCampbell & Ikegami, 1998; Reference Ikegami and CampbellIkegami & Campbell, 2004). Self-employed people began to be covered in 1938 through the Citizens’ Health Insurance Act (Kokumin Kenko Hokenhou, officially translated as the National Health Insurance Act), which gave municipalities the power to establish coverage for their residents. At its peak in 1943, 70% of the population was covered by municipal schemes. As the economy recovered after the Second World War, the major political parties worked to establish a welfare state, the Ministry of HealthFootnote 1 increased its funding for municipal schemes and the whole population was eventually covered by national health insurance (NHI) in 1961.

Enrolment in NHI is mandatory for all legal residents, including foreigners, except recipients of public assistance and short-term visitors. Around 60% of the population is covered by a health plan provided by their employer and the remaining 40% (the self-employed or retired) are insured by their municipality. Dependants are covered by the scheme of their head of household. For those employed, contributions are deducted from salaries and the employer pays about half of the contribution.Footnote 2 Health plans fall into four categories according to the degree to which they rely on tax funding from the central government. Thanks to these transfers from the central government, everybody pays about the same share of their income for health coverage, up to a gross annual income of 14.4 million Yen for the employment-based plans.Footnote 3

A new plan for people aged 75 and over was established in 2008. Managed by a coalition of municipalities in each prefecture, it is financed by contributions from all other plans, and allocations from the government budget. To equalize the cost for people aged between 65 and 74, all plans (except the plan for people aged 75 and over) must contribute on an equal basis. As a result of these two cross-subsidies, over 40% of the revenue of plans in the first category is allocated to pay for the care of older people.

In terms of health service delivery, over two thirds of all beds are in the private sector, mainly in physician-owned hospitals, and the remaining are publicly owned by the local government, or by established public organizations, such as the Red Cross. There is mutual animosity between the two groups as the publicly owned hospitals are the key beneficiary of the government’s subsidies and, as a result, can invest in high-tech care and hire more staff.

The national fee schedule set by the government plays a key role in linking financing and delivery by controlling the amount of money that flows from health plans to providers. Plans provide essentially the same benefits, including unrestricted access to virtually all health care providers and to services and medicines on a positive list. Excluded items include surcharges for private hospitals beds, eyeglasses and contact lenses, and new technologies and medicines not yet in the fee schedule. Some restrictions are also applied to dental care in terms of what materials can be used (Reference Tatara and OkamotoTatara & Okamoto, 2009). Items not listed in the fee schedule cannot be provided in combination with listed items in the same episode of care administered by the same doctor in the same setting. Should they be included, all costs, including staff and facility costs, and not only the costs of the uncovered item, must be paid for out of pocket. The only exception to this rule is services listed under the Specified Medical Costs of the national fee schedule, such as hospital rooms with more amenities and new technologies still under development, for which extra-billing is allowed (Reference IkegamiIkegami, 2006).

In the past there have been major differences in the extent of cost sharing for different population groups, with initially free care for the employed and high cost sharing for dependants and those covered by municipal schemes. Following various changes in policy, all pay 30% of the cost of covered health services out of pocket, except for more than 90% of the people aged 72 and over who pay 10%, and children whose co-payment rate depends on the municipality, but this rate declines to 1% for payments beyond the catastrophic amount (Reference Ikegami and BankIkegami, 2014).

Private health insurance

Cash benefits for hospitalizations resulting from traffic accidents began to be sold as an accident insurance option in 1963 and a life insurance option in 1964. They gradually expanded to cover illnesses and, by 1976, all life insurance companies offered them. Independently, in 1974, Aflac JapanFootnote 4 offered cancer insurance as a third type of stand-alone insurance product. In 1995, regulation was passed stipulating that foreign accident and life insurance companies could freely introduce this third type of insurance. To protect the interests of foreign companies and allow them to gain a foothold in a market dominated by domestic companies, the major domestic companies were only given unrestricted access to this market in 2001 (Reference MiyajiMiyaji, 2006). The third type of insurance became popular because cost sharing for publicly covered health services for employees was introduced at a rate of 10% in 1984, rising to 20% in 1997 and 30% in 2003. Private health insurance benefits from tax subsidies; up to 50 000 Yen (about US$500) per year can be deducted from gross income for premiums paid for any type of insurance product.

As competition in the insurance market intensified, commercial life insurance companies strove to develop ever more comprehensive products such as plans for cancer patients offering cash benefits for every outpatient visit after hospital discharge or plans including the early stages of cancer (carcinoma in situ). However, an investigation by the Finance Agency revealed that benefits were often not paid out as stipulated in the contract. Many clients took out insurance without having a full understanding of the contractual terms and did not submit their claims. Legitimate claims were also rejected by front-line staff who lacked sufficient knowledge of the contracts. Penalties were imposed on companies that breached contractual obligations and new rules were introduced so that companies had to inform clients about their benefit entitlement at the time of signing the contract and at the point of meeting front-line staff (Asahi Shinbun, 2007a).

The Ministry of Health had historically abstained from overseeing the private health insurance market but in 2006 it issued a directive stipulating that the extent of catastrophic coverage (coverage provided when coinsurance exceeds a defined amount) should be clearly stated when private health insurance is advertised, although it stopped short of obliging insurers to provide detailed information on the amount of coinsurance that patients are at risk of paying under public coverage (Asahi Shinbun, 2007b). In 2007 the Ministry of Health introduced a further protection for consumers so that eligible subscribers only have to pay coinsurance to the extent not covered by catastrophic illness insurance, instead of paying the whole amount up-front and being reimbursed later. Insurers have to notify eligible subscribers of this entitlement.

In 2001 the Regulatory Reform Council of the Prime Minister’s Office started a campaign to remove restrictions on extra-billing.Footnote 5 The Council drew attention to areas where such restrictions were both unfair and inappropriate, such as limiting the eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori to two regimens.Footnote 6 However, removal of restrictions on extra-billing was opposed by the Ministry of Health and the Japan Medical Association on grounds of safety and equity. In December 2004, a political compromise was reached and it was agreed that extra-billing could be applied to services listed under the Specified Medical Costs. Although the prohibition on extra-billing remained essentially unchanged, the momentum for deregulation was lost after political compromises had been made (Reference IkegamiIkegami, 2006).

It is worth noting that the Regulatory Reform Council did not mention the possibility of private health insurance complementing NHI coverage. Rather, the Council emphasized the importance of the patient as an informed consumer who should be able to make decisions based on benefits and costs, and of physicians providing full and impartial information. One reason for this omission is that, as economists, the conceptual thinking of the Council’s members was focused on ensuring individual choice. A more practical reason is that companies venturing into indemnity-type insurance for extra-billed services would be faced with adverse selection. Another consideration may have been that the Chair of the Regulatory Reform Council was the CEO of a life insurance company and therefore could not openly advocate private health insurance.

The debate on private health insurance is by no means closed. Per person spending on health is the third lowest among G7 countries in purchasing power parity terms (WHO, 2018), three decades of low economic growth have led to a national debt more than twice the size of the gross domestic product and the Ministry of Health has intensified its efforts to contain health care costs. Cuts to the national fee schedule may make the system unsustainable from the perspective of providers, which may remove structural barriers to expanding private health insurance in the future (Reference Ikegami and BankIkegami, 2014).

Republic of Korea

Publicly financed health coverage

National health insurance was established in 1977 for the employees of large firms and gradually expanded to cover the whole population by 1989. In 2000, over 350 quasi-public health insurance societies were merged to create the single, national National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) (Reference KwonKwon, 2003a). There is a separate programme for the poor (Medicaid) financed from general central and local government revenues. NHIS contributions are proportional to wages and shared equally by employer and employee, with government providing some subsidy for self-employed people.

The NHI services are subject to cost sharing in the form of coinsurance (see Table 9.2). There is no coinsurance for Medicaid beneficiaries. In 2004, the government introduced a cap on out-of-pocket payments for covered services, which now has seven ceilings depending on income levels: Korean won (KRW) 1.2 million (per 6 months) for the lowest decile, KRW1.5 million for the second and third deciles, KRW2 million for the fourth and fifth deciles, KRW2.5 million for the sixth and seventh deciles, KRW3 million for the eighth decile, KRW4 million for the ninth decile, and KRW5 million for the highest decile.

Patients pay fully out of pocket for non-covered services such as new tests and materials or private rooms and may pay extra for consulting experienced specialists in tertiary care hospitals. On average, out-of-pocket payments can amount to as much as 40% of the total cost of care (OECD, 2016). Extra-billing for services that are not covered enables a private market in which providers can charge their own unregulated prices. By allowing providers to mix covered and excluded services in the same episode of care, extra-billing has contributed to an increase in the provision of services not covered by NHI (Reference KwonKwon, 2003b).

Health care providers are legally required to participate in the NHI system and treat any NHI-covered person, even if they are not satisfied with the fees paid by the NHIS. However, physicians have considerable power in the market for private services that are not covered by NHI. More than 90% of acute care hospitals and 85% of acute care beds are private. Private hospitals are, in most cases, de facto owned and managed by physicians. There is service overlap and competition among physician clinics and hospitals because physician clinics also have (small) inpatient facilities, mostly for surgery and obstetric care. Specialist clinics compete with hospitals, which have large outpatient clinics as well as beds. The role of gatekeeping by primary care physicians is very limited. Service overlap and fee-for-service payment of providers contribute to inefficiencies in the health system.

Private health insurance

Enrolment in private health insurance plans seems to be high. Different estimates suggest that private health insurance covered 38% of the urban population in 2001 (Korea Labor Institute, 2002), 53% of the total population in 2006 (Reference LeeLee et al., 2006) and 70% in 2008 (Reference Jeon and KwonJeon & Kwon, 2013). High coverage may reflect the fact that private health insurance is often sold as a package with life insurance, which has high take-up rates. However, as a result of the bundling of insurance products, it is difficult to find accurate statistics regarding the size of private health insurance alone.

Survey data suggest that females and economically active groups (especially 35- to 49-year-olds) are more likely to purchase private health insurance (Reference YoonYoon et al., 2005). Income, education and health status are positively associated with the probability of purchasing private health insurance, which means adverse selection is not a major concern. Analysis of the impact of having private health insurance on health service use and spending found that, among cancer patients in a tertiary care hospital, those with private health insurance used more health care (measured in terms of length of stay for inpatient care and number of visits for outpatient care) (Reference Kang, Kwon and YouKang, Kwon & You, 2005). It also found that the outpatient spending of those with private health insurance was greater than those without private health insurance, but there was no difference for inpatient spending. Another study found that people with private health insurance use more outpatient care, resulting in greater spending (Reference Jeon and KwonJeon & Kwon, 2010).

Deregulation of the private health insurance market in 2007 allowed private insurers to develop health insurance products that link benefits to actual medical expenses (rather than just providing fixed cash benefits). This was part of a move by the government, driven by the Ministry of Strategy and Finance, to strengthen the competitiveness of the health care industry, encourage more innovation, boost exports in the areas of medical technology and pharmaceuticals and increase medical tourism. The Ministry of Strategy and Finance also supports the introduction of for-profit hospitals, which would be allowed to opt out of the NHI and contract with private insurers. It believes that an expanded role for private health insurance will relieve fiscal pressure on the government.

The Korean Medical Association and the Korean Hospital Association have in the past been strong supporters of private health insurance, but the former is now ambivalent. Initially, it thought that private health insurance would give its members more opportunities to gain financially. However, it has realized that private insurers can be tough negotiators when setting fees and reviewing claims. There is a split in the Korean Hospital Association’s position between small and large hospitals, depending on their negotiating power in contracting with private insurers.

Private insurers would like to be allowed to cover NHI cost sharing, but the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the NHIS maintain that private health insurance should be limited to services that are not covered by NHI. They fear that the use of NHI services and spending would increase if NHI co-payments were to be covered by private insurers. Although private insurers argue that their market is small because they are limited to covering non-NHI services, out-of-pocket payments for such services account for as much as 24–33% of patient costs (and even more if a patient requires care at a tertiary hospital) (Reference Kim and ChungKim & Chung, 2005); the relative share of out-of-pocket payment for insured services and direct payment for uninsured services (not in the benefits package) was 54.5% and 45.5% of total out-of-pocket payment in 2011 (Reference SeoSeo et al., 2013). So in fact their potential market is already relatively large. Private insurers have also lobbied to lift the ban on for-profit hospitals and to remove the requirement for all providers to contract with the NHIS. If these changes were implemented, for-profit hospitals might opt out of the NHI and cater exclusively for privately insured patients.

So far there has been little regulation of the non-financial aspects of private health insurance, which is overseen by the Financial Supervisory Service supervised by the Ministry of Strategy and Finance. If the market is to expand and play a larger role, the Ministry of Health and Welfare will need to exercise some regulatory power to ensure complementarity between NHI and private health insurance and to ensure private health insurance does not undermine national health system goals.

Taiwan, China

Publicly financed health coverage

Taiwan, China launched employment-based insurance schemes in 1950 and 1958 and covered 57% of the population by 1994. Coverage was extended to previously uninsured groups (mainly women, children, older people, pensioners, casual workers and unemployed people) through NHI introduced in 1995. In 2015, 99.6% of the population was covered by NHI (NHIA, 2015). Most NHI revenues come from income-related (mainly salary-based) contributions and supplementary premiums (paid on incomes other than salary) collected by the NHI Administration (NHIA) and general taxes collected by central government. Contributions are shared between beneficiaries, their employers and the government – 35.45%, 36.26% and 28.28%, respectively in 2014 (MOHW, 2016a).

The NHI offers comprehensive benefits. Cost sharing in the form of coinsurance is imposed on all patients except for poor people, disabled people, veterans and their dependants, children under 3 years old, those living in remote areas, those suffering from expensive diseases, and for maternity care. The coinsurance rate is 10% for inpatient care subject to a ceiling per hospital admission or annual cumulative ceilings of, respectively, 6% and 10% of the national average income per person. The mandatory coinsurance rate for outpatient care is 20%. Hospital patients without a referral are subject to higher coinsurance rates, but because of political and feasibility considerations, the NHIA tends to set the co-payment amounts at levels which are lower than the mandatory rates. The co-payment for outpatient medications is about 20% of the costs (up to a maximum of 500 New Taiwan dollars (NT$)Footnote 7 per visit), except for patients whose medicine costs are lower than NT$100 per visit or for those refilling prescriptions, who do not have to pay the co-payment for medicines. The coinsurance rate for home care is 5%. There is no ceiling on maximum payments for outpatient and home care (NHIA, 2015). In general, extra-billing is prohibited by law except for costs associated with private or upgraded hospital beds, private nurses, designated physicians and medical devices or materials of higher quality, such as drug-coated stents, orthopaedic joints and any other items designated by the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Health care delivery is a mixture of public and private. In addition to public health stations, most clinics and two thirds of hospital beds are private (MOHW, 2016b) and most hospitals (93%) are contracted by NHI (NHIA, 2015). The market is highly competitive and patients usually have free choice of provider. Payment is mainly on a fee-for-service basis, although fees for 98% of services were capped by the national global budget programme in 2002 (Reference ChengCheng, 2003; Reference LeeLee et al., 2006). Diagnosis-related groups were introduced in 2010. As of 2016, 401 out of 1017 DRGs have been implemented.

Private health insurance

In 2004 private health insurance covered 72% of the population (Reference LinLin, 2006). Survey data indicate that in 2006, among those who had private health insurance, 70%, 80% and 90% had catastrophic, cancer and inpatient cover, respectively (Reference 324TsaiTsai, 2007). Most had more than one type of cover. Cover was positively associated with income and was highest among those aged 25–44 (about two thirds of this age group had private health insurance), followed by those aged 45–54 (53%) and those aged below 25 (32%). People over 55 had the lowest coverage rate (17%), possibly due to age restrictions set by private insurers (the maximum eligible age for cover is around 75). Overall, private health insurance coverage is highly selective and more likely to favour so-called ‘good’ risks.

Private health insurance accounted for 9.5% of total spending on health in 2014 (Taiwan Insurance Institute, 2016). Its share of private spending on health grew rapidly from 1.8% in 1991 to 23.4% in 2014. Total income from private health insurance premiums, at about NT$306.5 billion in 2014, was higher than the total income from household NHI contributions, which stood at NT$151 billion. However, private health insurance spending accounted for only 0.6% of gross domestic product in 2014, which was much lower than that of NHI payments (3.2%) in that year. The ratio of income to claims in private health insurance is very low (30.9%), partly due to favourable risk selection and partly because many private health insurance products are multi-year products or investment insurance products, so it may be meaningless to calculate claims ratios on an annual basis. Private health insurance premiums below NT$24 000 per year are tax-deductible.

As the NHIA’s global budgets have tightened, providers have become more enthusiastic about developing services not covered by NHI and extra-billing has become more common. The NHIA has also introduced new measures to contain costs by reducing coverage – for example, it has increased co-payments, excluded nonprescription drugs from coverage, introduced selective coverage for some extremely expensive but less cost-effective drugs and expanded the list of services (mainly medical devices) for which extra-billing is allowed. All of these strategies leave more room for the development of complementary private health insurance.

Changes to hospital management also create new opportunities for the private health insurance market. To control spending, since 2003, the NHIA has introduced self-governing strategies (equivalent to individual hospital budgets) for some hospitals that are able to meet set utilization and quality criteria. Although this arrangement provides strong incentives for hospitals to control costs, it could increase the likelihood of waiting times, cream-skimming or lower quality of care, potentially creating more demand for private health insurance. It has also shifted costs to households. Out-of-pocket payments have risen as a share of total spending on health from 32.7% in 2004 to 34.7% in 2014 (MOHW, 2016a).

However, private health insurance has not developed enough products to meet the changing needs of NHI beneficiaries. Currently, it offers coverage that is focused more on the less-prevalent high-loss inpatient care or catastrophic costs, rather than on more prevalent outpatient care for chronic conditions or long-term care, for which people have to pay significant co-payments without any cap. Furthermore, private health insurance reimbursement principles encourage patients to try to obtain more payment, for example, by selecting more expensive inpatient care over outpatient care, or through longer hospital stays. These practices undermine the NHIA efforts to improve efficiency.

Part of the market’s lack of responsiveness to changing circumstances may have been due to regulatory constraints. In 2006 the Bureau of Insurance (BOI) loosened its regulation of private health insurance product review. While pre-approval is still required for certain products, the previous pre-filing system has been replaced by a post-filing system. Since 2015, to meet the emerging needs of an ageing population, BOI has been encouraging provision of private health insurance plans offering in-kind benefits for medical care, health management and long-term care (Financial Supervisory Commission, 2016).

A newly amended NHI Act, implemented in 2013, introduced additional NHI contributions from nonsalary income to relieve fiscal pressure. It allows extra-billing for expensive new medical devices and will establish a priority-setting mechanism, to apply health technology assessment to the coverage decisions of new medications/procedures/ technologies (DOH, 2011). These policies, except the first one, will increase the need for complementary private health insurance. However, as some civic and welfare groups argue, the extra-billing bill is pro-rich and will increase the allocation of NHI resources to the wealthy who can afford private health insurance. The introduction of Ten-Year Long-Term Care Development Plans in 2008 (The Executive Yuan, 2007) and its amendment in 2016, providing free long-term community and home services with 16–30% coinsurance to all citizens may increase the demand for long-term care and so benefit the private health insurance industry.

Overall, there would seem to be more opportunities than threats for the development of private health insurance playing an enhanced supplementary and complementary role. However, fierce competition in the insurance market has driven insurers into a price war. The majority of life insurance profits come from financial investment income rather than from underwriting profits (Reference FangFang, 2006). In a climate of slow gross domestic product growth, private health insurance needs to develop more innovative products so that it is better able to fill gaps in NHI coverage.

Discussion

Private health insurance has not developed beyond cash payments in the three countries and, in spite of relatively high rates of population coverage, its share of total spending remains quite low. This reflects the fact that private health insurance tends to cover younger and healthier people – people who may not need additional cover at all – and may indicate some lack of understanding of the benefits offered by NHI. It could also indicate a high degree of risk aversion, especially among people who can afford to over-insure themselves – an Asian “save for a rainy day” attitude. Some may also be swayed by the investment opportunities that private health insurance offers.

Under NHI, the development of a substitutive role for private health insurance is unlikely. During the 1990s the government in Taiwan, China proposed moving towards a privatized, market-based multi-insurer system that would have facilitated the development of substitutive private health insurance. Although the reform proposal was supported by private insurers and some academics, the society of medical professionals was divided and the reform bill failed, due in part to the inability of political party leaders to reach consensus (Reference WongWong, 2003) but also due to heavy opposition from a social movement to save the NHI involving over 200 groups, primary care physician associations and academics.

Benefits of NHI tend to be comprehensive, limiting the scope for private health insurance to play a complementary role covering excluded services. In addition, private health insurance plans pay out regardless of the actual cost of care and are in fact usually lower than the actual cost incurred, especially for expensive care. Private insurers also set rigorous restrictions on insurance claims and often deny them.

Private health insurance has probably benefited from the high coinsurance rates for NHI coverage in all three countries, although for various reasons insurers have not developed specific products aimed at covering NHI co-payments. First, insurers may have feared adverse selection in offering coverage of co-payments. Second, although coinsurance rates can be high, NHI exempts or caps out-of-pocket payments for some groups of people or types of care in all three countries. Third, in Japan, rich companies sometimes offer much lower coinsurance rates than NHI, lowering demand for additional cover.

Supplementary private health insurance has not developed to offer faster access to health care due to the absence of waiting times or recognized groups of elite specialists. Patients generally have direct access to secondary or tertiary care without referral and are usually seen promptly. The fee-for-service payment of providers also ensures that productivity is high. In the context of growing financial pressure on NHI in all three countries, the role of private health insurance may increase in the future. The loosening of regulation of the private health insurance market in the second half of the 2000s may also lead to the development of new products, which could increase the linkages between NHI and private health insurance. For example, private insurers in the Republic of Korea (and also in Taiwan, China) have begun to sell products that reimburse medical costs instead of simply paying lump-sum benefits (although they can only reimburse up to 90% of NHI out-of-pocket payments). The extent to which private health insurance grows will depend on the political and regulatory context in each country, including the relative powers of the ministries of health and other government ministries responsible for the economy and industry; it will also depend on the willingness of the private health insurance industry to develop new products.

Conclusions

So far, private health insurance in Japan, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan, China has played a relatively minor supplementary role and has had little interaction with publicly financed health coverage, providing mainly lump-sum cash benefits for hospitalization or severe illness rather than covering actual health care costs. However, take-up of private health insurance is quite high, largely due to products being sold alongside or as part of life insurance.

Private health insurance has generated debate in all three countries, especially as fiscal pressures on NHI have grown, and the industry is a powerful interest group in policy discussions about NHI. Over time, regulation of private health insurance has been loosened, which may encourage private insurers to develop new products more closely linked to NHI coverage gaps in terms of excluded services, co-payments and extra-billing.