Pope Felix, a predecessor of Saint Gregory, built a noble church in Rome in honour of Saints Cosmas and Damian. In this church there was a man, a devoted servant of holy martyrs. One of the man’s legs had been totally consumed by a cancer. While he was asleep, the two saints appeared to their devoted servant, bringing salves and surgical instruments. One of them said to the other: ‘Where can we get flesh to fill in where we cut away the rotted leg?’ The other said: ‘Just today an Ethiopian was buried in the cemetery of Saint Peter in Chains. Go and take his leg, and we’ll put it in place of the bad one.’ So, he sped to the cemetery and brought back the Moor’s leg, and the two saints cut off the sick man’s leg and inserted the Moor’s in its place, carefully anointing the wound. Finally, they took the amputated leg and attached it to the body of the dead Moor. The man woke up, felt no pain, put his hand to his leg, and detected no lesion. He held a candle to the leg and could see nothing wrong with it and began to wonder whether he was himself or someone else. Then he came to his senses, bounded joyfully from his bed, and told everyone what he had seen in his dreams and how he had been healed. They sent at once to the Moor’s tomb and found that his leg had indeed been cut off and the aforesaid man’s limb put in its place in the tomb.Footnote 1

Over time, Cosmas and Damian, twin brothers reportedly martyred for their Christian faith in 297 CE, part of the persecutions during the reign of the emperor Diocletian (283–303 CE), became venerated as the patron saints of medicine, surgery, pharmacy, and, perhaps somewhat surprisingly to a contemporary reader, organ transplantation.Footnote 2 The pair are said to have been born in the mid-third century CE at Aegae in the Roman province of Cicilia (modern-day Ҫukurova in Turkey) on the Bay of Alexandretta (modern-day Iskenderun), and to have studied medicine in Syria. Once they began practicing medicine, they became renowned for refusing to accept payment for their services. Their most famous healing episode, and the reason for their role as patron saints of organ transplantation, is known as the ‘miracle of the black leg’.Footnote 3 This miracle involved the twins treating a white man suffering from a gangrenous wound in his leg by amputating the afflicted limb and replacing it with the limb of a deceased black man (in some versions described as an Ethiopian, in others a Moor).Footnote 4 Whatever the original motivation for telling the story in this way and making a concerted effort to differentiate between the patient and the donor on the grounds of race, it is clear that the ‘miracle’ would have been at once apparent to an individual hearing or reading this story, or seeing a visual representation of it.Footnote 5 The source for this episode, the writings of the archbishop of Genua Jacob de Voragine’s The Golden Legend, dates to the late thirteenth century (a specific date between 1252 and 1260 has been proposed), so well after the lives and deaths of Cosmas and Damian and the establishment of their cult. The earliest known illustration of this episode is found in a late-thirteenth-century manuscript of de Voragine’s work, and depicts Cosmas and Damian in the middle of the transplantation; they have removed the gangrenous white leg, which lies discarded to one side of the patient’s bed, and are in the process of attaching the black leg.Footnote 6 However, it soon became a popular subject for medieval artists and numerous later depictions of the event survive.Footnote 7

Figure I.1 Page from Jacob de Voragine’s The Golden Legend manuscript. Huntington Library manuscript HM 3027, folio 132 r.

Cosmas and Damian are part of a long tradition of miraculous healing in which the restoration of lost body parts serves as a demonstration of divine power. Inscriptions recovered from the healing sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidauros and dating to the fourth century BCE claim that visitors to the sanctuary underwent incubation rituals, and during these rituals the god appeared to them and cured their ailments.Footnote 8 One man claimed that the god restored his missing eye:

Once a man came as a supplicant to the god who was so blind in one eye that, while he still had the eyelids of that eye, there was nothing within them and they were completely empty. Some of the people in the sanctuary were laughing at his simple-mindedness in thinking that he could be made to see, having absolutely nothing, not even the beginnings of an eye, but only the socket. Then in his sleep, a vision appeared to him. It seemed the god boiled some drug, and then drew apart his eyelids and poured it in. When day came he departed with both eyes.Footnote 9

Another, Heraieos of Mytilene, claimed that the god restored his lost hair:

This man had no hair on his head, but plenty on his chin. Ashamed because he was laughed at by the others, he slept here. The god anointed his head with a drug and made it have hair.Footnote 10

It was not just Asklepios, the Greek god of medicine, who was purported to restore lost body parts. Other examples include the goddess Minerva Medica reportedly restoring a woman named Tullia Superiana’s lost hair at a sanctuary near Travo in the Trébbia valley in northern Italy during the Roman period.Footnote 11 Additionally, early Christianity was replete with tales of the restoration of lost body parts, with Jesus supposedly restoring the ear of a high priest’s servant that was cut off by his disciple Peter in an attempt to prevent Jesus’ arrest.Footnote 12

There have been numerous attempts to rationalise ancient healing miracles.Footnote 13 If one felt inclined to do so, one could rationalise these stories of restored body parts – whether extremity, eye, or hair – by referring to prostheses.Footnote 14 Thus, the man supposedly operated on by Cosmas and Damian was in actual fact given an extremity prosthesis, the man who claimed that Asklepios restored his lost eye was in actual fact given a prosthetic one (after all, no mention is made of his vision having been restored, just his eye), and the man who claimed that Asklepios restored his lost hair was in actual fact given a wig or hairpiece. This potential connection between ancient healing miracles and prostheses can be traced through the use of so-called ‘anatomical’ votives – that is, votive offerings in the form of body parts both external (such as fingers, hands, arms, toes, feet, legs, etc.) and internal (such as viscera, uteri, etc.) made from substances including, but not limited to, precious and semi-precious metal, marble, ivory, terracotta, and wood. The traditional interpretation of these objects is that they served as a representation of the part of the body that was ill, injured, or impaired in some way; they were offered to the god either in the hope that the god would heal the afflicted part, or as thanks for the afflicted part having been healed. See, for example, Figure I.2: this marble votive relief found near the Enneakrounos fountain in Athens, originally from the sanctuary of the hero-physician Amynos and dating from the late fourth century BCE.Footnote 15 It was dedicated by Lysimachides, son of Lysimachos, from Acharnai, and depicts him holding what appears to be an anatomical votive leg displaying a prominent varicose vein, with two anatomical votive feet on the left-hand side. Ever after, or at least until the sanctuary was cleared out and the votives ritually disposed of, the votive body part remained with the god, a visual representation both of the dedicant’s faith in the god and the god’s power.Footnote 16 The isolated body part contrasted with the now whole real body of the dedicant.Footnote 17 However, it has been suggested that anatomical votives can be viewed as an attempt to signify the metaphorical representation of the body in illness and pain.Footnote 18 In this way, they were used to represent the fragmentation or disaggregation of the ailing body of the person who was dedicating them, with the healing process conceived of as the reintegration of the fragmented parts leading to the reconstitution of the body of the person who was dedicating them.Footnote 19 One example of this process can be seen on a votive relief found in the Asklepieion at Athens and dating from the fourth century BCE.Footnote 20 It depicts what appears to be the offering of anatomical votives to Herakles Menytes by a female dedicant; if all of the disparate parts on display were put together, they would form a complete female body.Footnote 21 It has been interpreted as ‘a kind of “non-amputation” underscoring the integrity of the absent, cured dedicant’.Footnote 22 In some cases, anatomical votives represented an amputated part.Footnote 23 They have been considered to serve as ‘ritual prostheses, deployed to render the body whole and healthy again’.Footnote 24 They have also been described as ‘a psychological prosthesis … an aid to feeling whole … an aid to the healing process’.Footnote 25 It has been observed that anatomical votives rarely depict the illness, injury, or impairment; rather, they usually represent the body part in its normal or desired state.Footnote 26 Interestingly, a documentary papyrus from Egypt dating to around 118 CE can be seen as making this link explicit through its reference to a maker of artificial limbs manning a healing shrine.Footnote 27

Figure I.2 Greek votive relief. National Archaeological Museum of Athens inv. 3562.

But what of actual prostheses in classical antiquity?Footnote 28 While literary, documentary, archaeological, and bioarchaeological evidence for congenital and acquired amputation of various parts of the body in ancient Greece and Rome is plentiful, evidence for prostheses, prosthesis use, and prostheses users is somewhat harder to come by, and the evidence that exists is open to debate. The earliest surviving mention of a prosthesis in Graeco-Roman literature can be found in Pindar’s recounting of the myth of Pelops in the first Olympian Ode (circa 522–433 BCE), but this is obviously a mythological rather than an historical episode, and so we should proceed with caution when using this as a source for the lived experience of an actual ancient person in possession of a physical impairment.Footnote 29 While the finer details of the myth vary from source to source, ancient authors are generally in agreement regarding the main points: Pelops’ father Tantalus wished to make a suitable offering to the gods of the Olympian pantheon, so he killed his son, cut him up, and cooked him in a stew, which he then served to them.Footnote 30 All of the gods except for Demeter declined the stew, but since she was distracted by the loss of her daughter Persephone following her abduction by Hades, she ate the portion she was offered, and it so happened that this portion contained Pelops’ left shoulder. Upon discovering what Tantalus had done, the gods reassembled and resurrected Pelops, replacing his missing shoulder with an ivory prosthesis. However, the earliest mention of a prosthesis in Graeco-Roman literature that can be classed as historical and attributed to a genuine historical figure can be found slightly later than Pindar’s Olympian Odes in Herodotus’ Histories (circa 485–484 BCE).Footnote 31 According to Herodotus, Hegesistratus of Elis, the most distinguished soothsayer from among the Telliads, a Greek clan renowned for their knowledge of prophecy, was captured and imprisoned by the Spartans and, in an attempt to avoid the torture and execution which they undoubtedly had in store for him, amputated enough of his foot to enable him to remove his shackles. He then broke through the wall of his cell and escaped to the safety of Tegea. Once his wound healed, he acquired a wooden foot and continued to work against the Spartans, actions which led to his subsequent recapture and execution after the battle of Plataea.Footnote 32

Precisely how useful either of these episodes are as a source of information on any aspect of ancient prostheses, prosthesis use, or prostheses users is debatable.Footnote 33 Yet while there are some obvious differences in the fine details of these two accounts, there are also some notable similarities. Both the myth of Pelops and the account of Hegesistratus demonstrate an individual losing a body part and subsequently replacing it with an artificial substitute; ancient authors emphasise the fact that their incomplete bodies are rendered complete through these actions, thus contextualising and rationalising the decision to do it.Footnote 34 They demonstrate a particular emphasis being placed upon the material from which the prosthesis is manufactured; Pelops’ prosthesis is made from the exotic and luxurious imported substance ivory; ever after, this ivory shoulder serves to distinguish its bearer by its gleaming, shining and glowing, while Hegesistratus’ prosthesis is made from ubiquitous, utilitarian, hardy wood, a material that was readily available even in wartime.Footnote 35 They demonstrate that subsequently these prostheses are what they are famous for (in the case of Pelops, reference to his prosthesis serves almost as a heroic epithet; in the case of Hegesistratus, his act of self-mutilation is described in the language of heroic accomplishment and his prosthesis is an eternal indicator and reminder of that act).Footnote 36

The English term ‘prosthesis’, which is used today to refer to an artificial device that replaces or augments a missing or impaired part of the body – whether lost or impaired because of trauma, disease, or a congenital condition – is a compound of the Greek preposition πρός (‘on the side of’) and noun θέσις (‘setting’ or ‘placing’). It seems to have first entered the English language in 1533, and at that time was used in a grammatical capacity to designate the addition of a syllable to the beginning of a word; it was not until 1704 that it seems to have been first used in a medical capacity, and only in the middle of the nineteenth century that it came to mean this almost exclusively.Footnote 37 Despite its Greek origins, it is not a term that was readily utilised by ancient authors, or at least not quite in the way that we use it today.Footnote 38 When the word πρόσθεσις (‘application’) is used in Greek literature, it indicates the application of an object for a specific purpose, as in the application of a medicinal remedy such as a pessary or a piece of medical equipment such as a cupping vessel, both of which would have been temporary.Footnote 39 No ancient Greek or Latin medical treatise mentions what we would recognise as prostheses, however; clearly, the application of a prosthesis to the body for the purpose of replacing a missing part, whether temporary in the sense of applying it for a period of time each day, or permanent in the sense of applying it every day for the remainder of one’s life, was not considered a medical remedy. The nearest any ancient Greek or Latin medical writer gets to this is recommending that gold wire be utilised to fix loose teeth in place; there is, however, no mention of the possibility of utilising a dental prosthesis to replace these loose teeth if the gold wire is unable to secure them and they are lost.Footnote 40 Whereas in the twenty-first century we tend to refer to prostheses using the noun ‘prosthesis’ or the adjective ‘prosthetic’, whatever the type of prosthesis under discussion, when prostheses are referred to in ancient literature, they are described in a very different way, which involves using the combination of the substitute body part and the substance from which it is made. So, for example, Pelops has a shoulder of ivory (ὦμος ἐλεφάντου or umerus eburno), Pythagoras has a thigh of gold (μηρός χρυσοῦ), Hegesistratus has a foot of wood (πούς ξυλίνου), Marcus Sergius Silus has a hand of iron (manus ferrea), and Statyllius has the hair belonging to another (ἀλλότριος πλόκαμος).Footnote 41

Prostheses in the Twenty-First Century

In a monograph dedicated primarily to the subject of prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users in classical antiquity, it would be helpful at the outset to clarify to what am I referring when I use the term ‘prosthesis’. What, exactly, is a prosthesis?Footnote 42 To the twenty-first-century reader, a prosthesis is a device that replaces a missing body part, usually (but, crucially, as we shall see, not always) designed and assembled according to the individual’s appearance and functional needs, and usually (but, again, crucially, not always) as unobtrusive and as useful as possible so as to maximise the chances of their acceptance of it.Footnote 43 The missing body part can be missing due to a congenital or an acquired impairment, although in the case of the former scenario it could be argued that the individual is not, in their opinion at least, impaired as they have never known any different.Footnote 44 Studies have shown that if an individual both mentally and physically accepts their prosthesis and is satisfied with it, they will be more likely to use it: the prosthesis needs to ‘fit’, in all senses of the word, its user.Footnote 45 A user is more inclined to accept a prosthesis that is aesthetically pleasing to them than not and consequently considerable effort is expended on the part of the prosthetist to match skin tone, hair colour, etc., or to design and create something unusual and truly unique if that is what the user desires.Footnote 46 A user is also, understandably, more inclined to accept a prosthesis that makes their life easier than one that makes their life harder.Footnote 47 Thus, it is necessary to consider each contemporary prosthesis as having a dual role, one aspect of this being its form and another being its function, although these aspects can and do also overlap, as we shall see. The nature of these forms and functions varies from prosthesis to prosthesis. A contemporary extremity prosthesis such as a finger, hand, or arm not only resembles the missing finger, hand, or arm but can also restore some (but not all) of its functionality, whereas in the not too distant past someone who lost a hand or an arm was required to choose between a prosthesis shaped like a hand but impractical, or one shaped like a hook but practical.Footnote 48 A facial prosthesis – or cosmesis, as examples of this type are sometimes designated – such as an eye or a nose resembles the missing eye or nose and, while it does not restore the lost sense of sight or smell, it does enable the user to ‘pass’, if that is what they wish to do.Footnote 49 And, indeed, the precise form of a prosthesis can be its primary function, if it is designed first and foremost with its appearance in mind, and its function is to be seen and to make a statement on behalf of its user, whatever its owner wishes that statement to be. In this sense, it may be said that its function is not to be practically useful to its user but to be impractically useful to its user. It depends entirely upon one’s perspective.

Yet this was not always the case, and it would be helpful to summarise briefly how we got to this point. How far can utilising contemporary prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users as points of comparison assist us in our attempt to understand their ancient equivalents? It is important to remember that not only is our contemporary understanding of impairment and disability not necessarily applicable to ancient societies, but also that our contemporary understanding of assistive technology might not necessarily be either. While, as we shall see over the course of this monograph, congenital and acquired amputation has always been present in human history, prosthesis use seems to have been relatively static from our first available archaeological evidence of it from Italy and China in the third century BCE until the sixteenth century, a period of some 1,800 years.Footnote 50 The French surgeon Ambroise Paré seems to have been the first maker of prosthetic limbs to explore the possibilities of mechanics.Footnote 51 However, the contemporary prosthesis in all its variability is the result of almost three centuries of medical and surgical advances, such as the development of anaesthesia, antiseptic, and amputation techniques, in conjunction with recognition of the necessity of dealing with the after-effects of modern warfare.

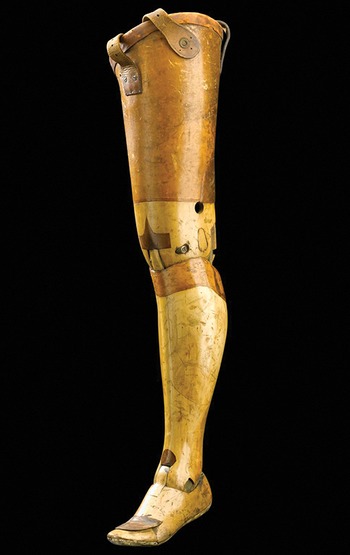

We first see prostheses come to prominence, albeit on a small scale, in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15). Henry William Paget, the first Marquess of Anglesey, was shot in the right knee at the Battle of Waterloo, and his right leg was amputated.Footnote 52 He was subsequently fitted with a prosthetic leg designed and patented by James Potts of London, the world’s first articulated prosthetic leg, that comprised a wooden shank and socket, and a foot that could be controlled by catgut tendons running from the knee to the ankle. Flexion of the knee caused dorsiflexion of the foot, and extension of the knee caused plantar flexion of the foot. Even though this type of leg had first been manufactured in 1800, it came to be known as the ‘Anglesey Leg’ after its most famous user. He ultimately came to possess several different prosthetic legs, examples of which can be seen at Plas Newydd in Anglesey, the Household Cavalry Museum in London, and the Musée de l’Armée in Paris.Footnote 53 The amputation did not spell the end of his military career; he went on to become a Field Marshall, Knight of the Garter, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and Master-General of the Ordinance. In fact, the amputation and the adoption of an extremity prosthesis made the Marquess, who came to be known as ‘One-leg’, something of a celebrity in Victorian society, and both his original leg and his prosthetic leg likewise became celebrities.Footnote 54 It is worth noting, though, that he was in a privileged position as a member of the British aristocracy, being wealthy enough to afford to purchase multiple technologically advanced prosthetic legs, and having been operated on by a surgeon competent enough to leave him with a stump that enabled him to wear them. Many contemporaneous amputees had to make do with simple peg-legs, or even just a pair of crutches. In some cases, the ‘social condition’ of a patient was considered by the surgeon performing the amputation, who was of the view that while a wealthy individual would be in a position to avail themselves of the highest-quality prosthesis, which necessitated providing them with a suitable stump, a poor individual would not, so it did not.Footnote 55

Figure I.3 Anglesey Leg. Science Museum/Wellcome Collection inv. A500465.

In the wake of the United States of America’s Civil War (1861–5), during which an estimated 60,000 limbs were amputated, a concerted effort was made by private companies to develop prosthetic technology to cater to the unprecedented demand for it, and these drew upon the ‘Anglesey Leg’ for inspiration.Footnote 56 This relationship between warfare and prosthesis manufacture continued in the wake of the First World War (1914–18) and other wars fought in the twentieth century, such as the Second War (1939–45), the Vietnam War (1955–75), and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (2001–present).Footnote 57 It has been suggested that the soldiers who returned from these wars posed a problem: the ‘crippled soldier problem’.Footnote 58 In order to reintegrate veterans into society, it was considered necessary to restore not only the former soldier’s economic productivity and thus prevent him from proving a drain on national resources, but also his masculinity, endangered by his new-found frailty and vulnerability. Anxiety about a former soldier’s or sailor’s ability to return to their previous occupation or at the very least earn a living was profound.Footnote 59 This anxiety was not only felt by the soldier or sailor in question, but also by society at large, which saw the primary problem with the veteran being not the impairment but the possibility that it would result in them becoming a burden on post-war society, crippling (and here I use that pejorative word deliberately) the nation’s economic growth and well-being.Footnote 60 This was a problem that needed to be solved. Consequently, cooperation between surgeons who performed amputations and prosthetists who designed and manufactured prostheses increased. Alternatively, we could consider these soldiers to be ‘broken soldiers’ rather than ‘crippled’, ‘wounded’, or ‘injured’, because what is ‘broken’ can be ‘fixed’, and it is clear that a concerted effort was made to ‘fix’ these ‘broken soldiers’ by crafting them prostheses of varying types.Footnote 61 In this period, the preferred prosthesis was one that was facilitated easy and natural motion; appeared realistic; and was durable, lightweight, and affordable.Footnote 62 It promised its user the ‘fiction of wholeness’.Footnote 63 While there was a certain amount of pride felt about a wound received in service to one’s country, which could be viewed a sign of martial valour and manly courage, broadly speaking nineteenth and twentieth century society tended to stigmatise impaired bodies and characterise them as economically burdensome, psychologically unstable, and socially objectionable.Footnote 64

Concurrent with the development of the prosthesis industry during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was the rise of mechanical surgery – that is, treatment with apparatus such as trusses and other types of ‘technologies of the body’.Footnote 65 This resulted in a complex relationship between bodies, machines, instruments, and mechanics, and an equally complex relationship between their effects upon an individual’s appearance, image, and identity.Footnote 66 For perhaps the first time, it was thought that errant nature could be corrected.Footnote 67 Purveyors approached their target audience as customers rather than patients, and claimed that their approaches would succeed where medicine had failed, deliberately creating a link between medicine and scientific instruments and gadgets.Footnote 68

Just as the Marquess of Anglesey popularised prostheses in Victorian society, the increasingly high profile of prostheses in western Europe during the early twenty-first century is the result of the high profile – one might say celebrity status, even – of veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and participants in the Paralympic Games, particularly the London 2012 Olympic Games. Personalised prostheses are becoming more popular, particularly among younger prosthesis users. Thus, we might speak of ‘aesthetic prosthetics’ or ‘proAesthetics’.Footnote 69 Notable here is the work of Sophie Oliveira Barata at the Alternative Limb Project, where ‘alternative’ prostheses are designed and constructed in consultation with the client and their prosthetist according to the client’s specific tastes and preferences, with prices for an ‘alternative’ prosthesis starting at £1,000 (the Alternative Limb Project also offers ‘realistic’ prostheses; prices for these start at £700 and can go up to £6,000).Footnote 70 Other companies, such as Limbitless Solutions, aim to utilise 3D printing to create bionic prostheses for children at affordable cost, and a promotional short film for the company featured the actor Robert Downey Jr, in character as the Marvel superhero Tony Stark/Iron Man, presenting a 3D printed prosthesis to a young boy with a partially developed right arm.Footnote 71

Bespoke prostheses such as those made by Sophie Oliveira Barata are intentionally simultaneously prostheses and works of art, and have been exhibited accordingly, demonstrating recognition of the growing importance of the form of a prosthesis in addition to its function, and the way that this form can be enlisted as a means of self-expression, just like any other accessory.Footnote 72 In 2017, the exhibition ‘Prosthetic Greaves’ ran from 14 to 29 October at the Glasgow School of Art, and exhibited the outcomes of the Glasgow School of Art’s ‘Prosthetic Greaves’ research project.Footnote 73 Two researchers, Jeroen Blom and Tara French, developed a method for digitally designing bespoke limb-shaped models that can be customised according to an amputee’s body shape and preferences, and these models could then be used to create craft-specific templates that suit the materials and techniques. Using this method as a basis, the creative design process between artisans and amputees could focus on creating a shared background and deep understanding of the needs that can be translated into the designs of the lower limb prosthesis covers. Since research has found that many amputees prefer a different aesthetic than the common prosthetic design choices of either a foam limb-shaped cover or a bare pole, the ‘Prosthetic Greaves’ research project sought to deliver a beautiful crafted aesthetic for lower limb prothesis covers – ‘greaves’ – by having artisans work in collaboration with amputees.Footnote 74 Three unique prosthesis covers were created and subsequently displayed in conjunction with information about the design and production process. The first, made by Karen Collins from Naturally Useful, a willow weaving company, used different types and colours of willow and wove them into a beautiful, strong, and lightweight shape. The ‘greave’ sought to embody the connection to nature using naturally grown materials woven by hand, and the prosthesis user took part in practicing the weaving of willow, strengthening the personal connection with the final product. The second, made by Scott Gleed from Gleed3D, a company that specialises in model-making, combined casting techniques of white metal and crystal-clear resin to create a seamless integration of materials. The front of the ‘greave’ showed a pattern of stockings and the rear combined metal and resin to create the seam of the stocking. The rear also had an angular design, so it has its own unique shape rather than mirroring a human limb. The third, made by Roger Milton from Auldearn Antiques, an antiques company that also restores items and creates its own unique pieces of furniture, used carefully selected timber, highlighting the imperfection of the burls on the material to emphasise its unique character. Burls occur due to ‘illness’ of the tree, and the pattern that it creates is something truly unique to the tree and highly sought after by woodworkers. The resultant beautiful imperfection of the ‘greave’ signified the beautiful ‘imperfection’ of the human body through amputation, creating unity between the ‘greave’, the prosthesis, and the prosthesis user. This approach to the problem of the undesirability of the form of the contemporary basic prosthesis, essentially providing a desirable form for a cover for the prosthesis, is potentially a very flexible – not to mention cost-effective – solution.

Figure I.4 Naturally useful greave.

Two recent major museum exhibitions at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the world’s leading museum of art and design, have included prostheses, and have raised the profile of prostheses as works of art even further. In fact, both exhibitions’ advance publicity and promotional material featured the prostheses heavily. In 2018 the exhibition ‘Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up’ ran from 16 June to 4 November and displayed more than 200 of Kahlo’s possessions that had been discovered in the Blue House in 2004, having been locked away since the artist’s death in 1954. Among these possessions were several of her ‘technologies of the body’, a number of medical corsets that she wore to support her spine after a traffic accident she was in at the age of eighteen displaced three of her vertebrae, and a prosthetic leg that she wore after she contracted gangrene and her right leg was amputated in 1953.Footnote 75 The prosthetic leg is set into a red leather boot embroidered with fantastical creatures and strung with bells that would jingle as she walked. Kahlo designed and decorated these items herself, reclaiming these medical objects as a means of self-expression and using them to communicate her own feelings about her physical condition. Her relationship with these objects has been described as ‘one of support and need – her body was dependent on medical attention – but also one of rebellion’.Footnote 76 By personalising her ‘technologies of the body’ through decorating and adorning them, Kahlo was presenting herself as having explicitly chosen to wear them, rather than having to wear them.Footnote 77 Moreover, they served as a means of simultaneously revealing and concealing her disabilities, allowing her to present herself on her own terms.Footnote 78

Figure I.5 Gleed 3D greave.

Figure I.6 Auldearn Antiques greave.

In 2015, the exhibition ‘Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty’ ran from 14 March to 2 August and served as the first retrospective of the fashion designer’s life and work.Footnote 79 McQueen has been described as ‘the designer [who] has most meaningfully worked with disability and disabled bodies’.Footnote 80 In his work, ‘there is an understanding of and willingness to see disability as an aesthetic possibility, something which can be worked with, rather than disguised’.Footnote 81 His thirteenth fashion show, n° 13, for spring/summer 1999, was opened by the Paralympic athlete and double amputee Aimee Mullins, and to do so she wore a pair of prosthetic legs that McQueen had designed especially for her.Footnote 82 They had collaborated the previous year for the September 1998 ‘Fashion-Able’ issue of Dazed & Confused magazine and its ‘Access-Able’ editorial, and McQueen subsequently aimed to create three different pairs of legs for her to wear in his show. The first of these was to be glass, the second Swarovski crystal, and the third wood, although ultimately only the wooden pair was produced. The legs were designed to resemble a pair of Victorian knee-length boots with Louis heels, pointed toes, and slim ankles (McQueen was fascinated by Victorian literature, particularly the works of Charles Dickens), and inspired by a Louis XIV style table and contemporary wood carvers such as Grinling Gibbons.Footnote 83 They were made from ash wood for two reasons: the first being that the strength of the wood was sufficient to bear Mullins’ weight, and the second that it could be elaborately carved.

Figure I.7 Medical corset belonging to Frida Kahlo.

Figure I.8 Prosthetic leg belonging to Frida Kahlo.

Most recently, in the autumn of 2018 the National Museum of Scotland acquired the ‘Vine Arm’, a prosthetic arm made by Sophie Oliveira Barata at the Alternative Limb Project for the model Kelly Knox, to display in its Technology by Design exhibit.Footnote 84 Knox was born without her lower left arm and chooses not to use a functional prosthesis; rather, she uses prostheses as accessories to express her personality and explore aspects of her identity.Footnote 85 According to Knox, ‘I want to change the way society perceives disability – showing disability can be cool, fashionable, beautiful and powerful … it’s like my body is a canvas and when wearing an Alternative Limb, I become art.’Footnote 86 The ‘Vine Arm’ comprises a botanical tentacle which contains twenty-six individual vertebrae that allow movement in the arm to be fluid and curve around objects, and this is controlled by round sensors worn in Knox’s matching shoes, underneath her big toes, that enable her to move the Vine from side to side and to curve it. By pressing on the sensors with different pressure, she can control the speed and direction of the Vine’s movement.Footnote 87 In this context, Knox is not simply wearing a prosthesis; rather, she is wearing an entire outfit. The form of the ‘Vine Arm’ is its entire function.

According to Sophie Oliviera Barata, the Alternative Limb Project’s mission statement is to use ‘the unique medium of prosthetics to create highly stylised art pieces. As with fashion, where physical appearance becomes a form of self-expression, [we see] the potential of prosthetics as an extension of the wearer’s personality.’Footnote 88 Testimonials from the Alternative Limb Project’s clients support this. Jo-Jo Cranfield says the following of her ‘alternative’ prosthetic arm:

I’ve never seen the interest in having a prosthetic arm, they are heavy, uncomfortable and not at all practical. I like to be different and I love the fact that having one arm makes me effortlessly different to the majority of people – however, an alternative limb is something entirely different; I wanted people to have to look at me twice with amazement. My alternative limb is so different to any other prosthetic limb I have ever had. I wear it with pride. I’ve never seen a two armed person with snakes crawling into their skin, and even if I did I don’t think it would be so comfy! My alternative arm makes me feel powerful, different and sexy!Footnote 89

Kiera Roche notes the fundamental importance of her prostheses in coming to accept her new life as an amputee, and says the following of her prosthetic leg:

My attitude to being an amputee and wearing an artificial limb has changed with time. To begin with one is very aware of being different, of being disfigured, but as time moves on one adjusts and changes perspective. In the first few years my focus was on trying to be normal, wearing clothes that hid the fact that I was an amputee, but over the years I have become more comfortable with who I am and I now embrace having different legs for different activities and different occasions. I think losing a limb has a massive impact on one’s self esteem and body image. Having a beautifully crafted limb designed for you makes you feel special.Footnote 90

Figure I.9 Vine Arm designed by the Alternative Limb Project for Kelly Knox. National Museum of Scotland inv. T.2018.1.

Figure I.10 Snake Arm designed by the Alternative Limb Project for Jo-Jo Cranfield.

Figure I.11 Floral Leg designed by the Alternative Limb Project for Kiera Roche.

How applicable are these aspects of the recent history of prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users to their ancient historical equivalents? They are more applicable than one might first think. Let us bear the statements from users of Alternative Limbs in mind as we consider the Turfan Limb, an extremity prosthesis only very recently recovered from a grave at Turfan in China that has been dated to approximately 300–200 BCE, making it one of the two oldest known functional prostheses in the world.Footnote 91 It is roughly the same age as the famous Capua Limb, an extremity prosthesis recovered from a tomb at Capua in Italy that has been dated to approximately 300 BCE, which will be discussed later.Footnote 92 The skeleton of the deceased prosthesis user was present in the grave alongside the prosthesis, a relatively unusual occurrence when it comes to ancient assistive technology, and this has enabled bioarchaeologists to undertake a detailed examination not just of the prosthesis but of its user as well.Footnote 93 The deceased was a man aged between fifty and sixty-five years old at the time of his death, and he lived with a severe case of tuberculosis that froze his left knee joint in a bent position and consequently rendered walking unaided impossible. Since during this period traditional Chinese law decreed that mutilation punishment (xing) was to be meted out for a range of transgressions, impaired individuals experienced a considerable amount of stigmatisation, whether their impairments were the result of mutilation punishment or not.Footnote 94 The cultural and social context in which the deceased was living might therefore explain why he chose to supplement his impaired limb with a prosthesis rather than undergo surgical amputation of his left leg above the knee and then replace his lost leg with a prosthesis. It is, of course, equally possible that he simply did not have access to a surgeon who could or would have performed the operation had he requested it. But we should also bear in mind that the unusual nature of his impairment meant that he did not have to submit to what would undoubtedly have been a dangerous and extremely unpleasant procedure; he was able to use a prosthesis to restore his lost functionality regardless.

The Turfan Limb was made from leather, sheep or goat horn, and the hoof of a horse or an Asiatic ass.Footnote 95 It comprised a plate that was fastened to the left thigh by leather straps and which tapered into a peg-leg. No attempt was made to carve the peg-leg to resemble the human limb that it was supplementing; on the contrary, the peg-leg terminated in a hoof which may, in fact, have rendered the prosthesis easier to use. There is no indication that the deceased used crutches in conjunction with his prosthesis in the manner of several other ancient prosthesis users that we shall meet later. Since the deceased was not buried in isolation but was only one burial in a cemetery, it is possible to gain a degree of understanding of this community and its circumstances. The population were relatively poor, and the goods recovered from the deceased’s grave do not indicate that he was in any way unusual as far as wealth or social status were concerned.Footnote 96

Figure I.12 Turfan Limb.

The owner of the Turfan Limb was seemingly determined not to allow his impairment to become a disability in a culture and society where impairments were viewed as highly undesirable at best, punishment for a major transgression at worst, but either way were responsible for ensuring that those experiencing them were stigmatised and treated as pariahs. As a member of a relatively poor community with no access to prestige materials such as gold, silver, bronze, iron, etc., he elected to use materials that were in plentiful supply in his agrarian and pastoral society to create his prosthesis. These materials were the animal products of leather, horn, and even a hoof, and while the materials that his prosthesis comprised and the form that his prosthesis took can be seen as entirely practical, even utilitarian, a means of stabilising him as he moved around, it is also possible that his choice of an animalistic rather than humanoid limb was influenced by his Subeixi culture’s interaction with the Pazyryk culture of the Scythian communities in the nearby Altai mountains.Footnote 97

This leads us to an aspect of ancient prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users that it is necessary to take into account that dovetails nicely with the aims of the Alternative Limb Project: since each ancient prosthesis was entirely unique and designed and manufactured in isolation by the user, one artisan (for example, a carpenter), or a team of artisans (for example, a carpenter, a metal-worker, and a leather-worker), ancient prostheses can, perhaps, give us an insight into ancient cultures and societies and their users’ places within those, in addition to telling us something about the individuals themselves. Regarding the finished product, how influential was the consumer? How influential were the artisans? Whether the prosthesis is cosmetic, functional, or a combination of both, how far are the substance or substances from which it is made and the way in which it is made (for example design, craftsmanship, etc.) intended to serve an additional purpose related to conspicuous consumption to either demonstrate or enhance the status and prestige of its wearer?Footnote 98 Should we view ancient prostheses as having been akin to clothing and jewellery, and approach them as a type of ‘bodywear’ by which the ancient prosthesis user could show off his or her personal style or fashion sense?Footnote 99 Or should we view them as having been akin to a scientific gadget, such as the Antikythera Mechanism or the portable sundial, and approach them as a means by which the ancient prosthesis user could show off his or her intellectual and technical sophistication?Footnote 100

Literature Review

To date, relatively little scholarship has focused specifically on prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users, or any type of assistive technology at all, in classical antiquity.Footnote 101 Until 2018, the only reasonably comprehensive work on the subject was Lawrence Bliquez’s contribution to one of the volumes dedicated to medicine in the Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt series, entitled ‘Prosthetics in Classical Antiquity: Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Prosthetics’ (1996).Footnote 102 This piece selectively curated a certain amount of literary and archaeological examples, not all secure, of ancient prostheses, but the analysis and discussion of the subject was relatively limited. Then, in 2019, the edited volume Prostheses in Antiquity, the proceedings of a workshop held in 2015 and funded by the Wellcome Trust, was published. It comprised eight papers, each one dealing with a different type of prosthesis (e.g. facial, extremity) or an issue relevant to the subject (e.g. care).Footnote 103

As far as discussions of impairment and disability in classical antiquity are concerned, discussions of prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users play a relatively minor role. The first monograph devoted to the subject, Robert Garland’s The Eye of the Beholder: Deformity and Disability in the Graeco-Roman World (first edition Reference Garland1995, second edition Reference Garland2010), included a brief reference to the famous story of the Persian diviner Hegesistratus of Elis in a chapter focusing on medical diagnosis and treatment, noting simply that it was possible for an ancient amputee to utilise a prosthesis.Footnote 104 The second, Martha L. Rose’s The Staff of Oedipus: Transforming Disability in Ancient Greece (first edition Reference Rose2003, second edition Reference Rose2013), and the first attempt to integrate the relatively new discipline of Disability Studies into Classics, devoted slightly more space to the subject in the opening chapter of the work, an effort to set the scene in advance of a series of studies focused on particular aspects of impairment and disability in the ancient Greek world.Footnote 105 Like Bliquez, Rose curated some literary and archaeological examples, concluding that ‘it is difficult to believe that any prosthetic device would have been practical as well as cosmetic’.Footnote 106 The third, Christian Laes’ Beperkt? Gehandicapten in het Romeinse Rijk (Restricted? The Handicapped in the Roman Empire) (Reference Laes2014), contains an entire chapter on mobility impairments but prostheses are mentioned only in passing.Footnote 107 The English translation, a slightly updated version of the original Dutch text, Disabilities and the Disabled in the Roman World: A Social and Cultural History (Reference Laes2018), follows suit. Discussions of impairment and disability in the classical world are more frequently found in the form of edited volumes, and accordingly one might expect to find rather more discussion of prostheses here. Unfortunately, these likewise do not devote more than a sentence or two to the subject.Footnote 108 Prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users in other historical periods and contexts are equally understudied, although this is beginning to change.Footnote 109 There is, however, a considerable amount of scholarship on these subjects in the contemporary world and utilising this material as a source of comparative evidence is a distinct possibility.Footnote 110

Methodology

As mentioned, no surviving ancient medical treatise mentions prostheses. No surviving ancient scientific or technical treatise mentions them either. Nor do we have any examples of ekphrasis the way that we do for other lost medical, scientific, or technical objects of antiquity.Footnote 111 Yet, due to the scattered and fragmentary nature of the surviving literary, documentary, archaeological, and bioarchaeological evidence that attests that a variety of different types of prostheses were used by Greeks and Romans (broadly defined) to replace various missing body parts, the subject of prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users in classical antiquity lends itself to a ‘mosaicist’ approach. If we trust that the literary and documentary evidence provides a true representation of the way that the Greeks and Romans referred to prostheses in their daily lives, it becomes apparent that no uniform umbrella term, such as the adjectives ‘prosthetic’, ‘artificial’, or ‘false’, for example, was used. Perhaps the closest ancient authors come is referring to prosthetic hair and teeth using variations on the verb ‘to purchase’ (Greek πρίαμαι, Latin emo). As stated earlier, ancient authors more commonly refer to prostheses using a combination of the substitute body part and the substance from which that substitute has been made. Consequently, searching for ancient literary and documentary references to prostheses necessitates the extremely time-consuming process of entering numerous combinations of adjectives and nouns into bibliographic search engines such as the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae and the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae, and, when that fails, simply reading ancient literary and documentary texts from all historical periods and all historical genres. In Bliquez’s initial study, he admittedly focused his attention rather selectively:

The scope of this investigation was confined to those devices attached to the human body which had some practical as well as cosmetic purpose; that is to say, I was interested in dental appliances and false limbs, as opposed to wigs and bodily padding of the sort detailed by comic poets and satirists.Footnote 112

I have discussed what I consider to be the issues with Bliquez’s differentiation between what he perceived to be practical and impractical prostheses elsewhere.Footnote 113 As discussed, it is extremely difficult to separate a prosthesis’ form from its function. The binary opposition between practical and cosmetic assumes that there is nothing practical about a cosmetic prosthesis; but what may seem impractical to one person is highly practical to someone else. In any case, using this rationale, he collated sixteen ancient literary references to prostheses, comprising eleven dental prostheses and five extremity prostheses (three feet, one leg, one hand). To date, I have found 107 ancient literary references to prostheses, and these include references to prosthetic hands, shoulders, feet, legs, thighs, eyes, noses, teeth, and hair (see Table I.1); due to the nature of the search, even this is not necessarily exhaustive.Footnote 114 It is possible to differentiate between factual and fictitious references in the sense that prostheses appear in both ancient works of non-fiction such as Pliny the Elder’s encyclopaedia Natural History and fiction such as Petronius’ novel Satyricon, and between real and mythological references in the sense that prostheses are used by real individuals such as Hegesistratus of Elis and by mythological figures such as Pelops (see Table I.2). And yet, while at first glance we might be tempted to dismiss some, perhaps many, of these references on the grounds that they are not sufficiently ‘historical’, whether factual or fictitious, whether real or mythological, to a degree, archaeological and bioarchaeological evidence supports their veracity. Examples of prosthetic toes, feet, legs, teeth, hair, and a hand that seem to correspond rather closely with those referred to by ancient authors have been recovered from tombs and graves around the ancient and late antique Mediterranean (see Table I.3). Consequently, this data set can be used to elucidate a substantial amount of information about prostheses in classical antiquity, and the ways in which they were viewed in ancient Mediterranean cultures and societies.

Table I.1 All ancient literary references to prostheses found to date

Table I.2 Types of prostheses mentioned in ancient literature, and natures of prosthesis users

| Body Part | Fact | Fiction | Hypothetical | Total | Historical Figure | Mythological Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finger | ||||||

| Hand | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Arm | 1(?) | 1(?) | 1(?) | |||

| Shoulder | 14 | 14 | 14 | |||

| Toe | ||||||

| Foot | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | |

| Thigh | 9 | 1 | 10 | 8 | ||

| Leg | 3 | 6 | 9 | 3 | ||

| Eye | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Nose | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Teeth | 6 | 2 | 13 | 21 | ||

| Hair | 18 | 10 | 2 | 33 | 12 | 1 |

| Eyebrow | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Phallus | 2 | |||||

| Total | 41 | 35 | 24 | 107 | 28 | 16 |

Table I.3 Types of prostheses mentioned in ancient literature, and genders of prosthesis users

| Body Part | Male User | Female User | Unspecified | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finger | ||||

| Hand | 4 | 4 | ||

| Arm | 1(?) | 1(?) | ||

| Shoulder | 14 | 14 | ||

| Toe | ||||

| Foot | 5 | 5 | ||

| Thigh | 10 | 10 | ||

| Leg | 6 | 3 | 9 | |

| Eye | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Nose | 1 | 1 | ||

| Teeth | 18 | 3 | 21 | |

| Hair | 16 | 17 | 33 | |

| Eyebrow | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Phallus | 2 | 2 | ||

| Total | 63 | 37 | 7 | 107 |

It is crucial, however, that the ancient literary and documentary references to prostheses be treated critically.Footnote 115 Regarding ancient literature, references to prostheses can be found in a variety of different genres, but it is notable that the information provided about prostheses, and the ways in which they are presented, varies considerably depending upon the genre in which the reference is found.Footnote 116 For example, both men and women are presented as using prostheses (see Table I.4).Footnote 117 However, there are significant differences not only in the types of prosthesis that they are presented as using, but also in the ways in which these stories are told, and whether their prosthesis usage is a positive or a negative thing. There are also significantly more examples of men using prostheses than women. Why is this? Is it simply a result of the generally gendered nature of ancient literary sources? Very possibly, for while it is notable that the references are found in both prose and poetry across a range of genres, certain types of references are found in specific genres. The references to men using prostheses are found in all literary genres, but the references to women using prostheses are concentrated in satirical poetry and prose.Footnote 118 Men are presented as utilising extremity prostheses (i.e. feet, legs, hands), while women are presented as utilising facial prostheses (i.e. teeth, hair). Why is this? Were men more likely to lose limbs while women were more likely to lose facial features? Although realistically it is likely that both genders could lose any number of body parts in any number of ways – accidents do happen, after all – in literature men lose their body parts through military or agricultural activity, while women lose their body parts through mutilation or the natural ageing process. For men undertaking military activity, the loss of the right hand (the sword hand) and one or both eyes (due to lack of appropriate protective gear) seem to have been particularly common, while for men undertaking agricultural activity, the feet or legs were at risk from accidents with agricultural tools or bites from venomous creatures.Footnote 119 Women seem to have been particularly at risk of facial mutilation that occurred as the result of interpersonal violence, carried out purposefully to spoil their beauty and, in doing, so make them less attractive to men and therefore less valuable, and the female natural ageing process that resulted in the loss of teeth and hair receives much more commentary from ancient writers than the male one, again because of the effect that this had on a woman’s beauty, her attractiveness to men, and her intrinsic value.Footnote 120 Interestingly, in ancient Jewish literature, facial prostheses are recommended specifically to restore a woman’s physical attractiveness and make her a more desirable potential bride.Footnote 121 But perhaps there was some sort of visible imbalance in prosthesis use in ancient societies and this fed into existing stereotypes and bolstered them. It could be simply that male bodies were more visible in ancient Greek and Roman society than female ones, so male extremity prosthesis use was apparent to the casual observer in a way that female extremity prosthesis use was not.Footnote 122 And, yet again, archaeological and bioarchaeological evidence supports these demarcations (see Table I.5). Of the extremity prostheses that have survived from classical antiquity (broadly defined), all but one of those found in situ were found in the tombs and graves of men.Footnote 123 These include the third century BCE Capua Limb and the sixth century CE ‘Hemmaberg Limb’. Of the facial prostheses that have survived from classical antiquity, all of those found in situ were found in the tombs and graves of women, and the size of those that are unprovenanced indicates that they belonged to women too.Footnote 124

Table I.4 Materials the prostheses mentioned in ancient literature are made from

Table I.5 Archaeological and bioarchaeological evidence for ancient prostheses

| Body Part | Archaeological Evidence | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Finger | ||

| Hand | Povegliano Hand (Italy) | 1 |

| Arm | ||

| Shoulder | ||

| Toe | Greville Chester Toe (Egypt); Cairo Toe (Egypt) | 2 |

| Foot | Bonaduz Foot (Switzerland) | 1 |

| Thigh | ||

| Leg | Capua Leg (Italy); Hemmaberg Leg (Austria); Griesheim Leg (Germany) | 3 |

| Eye | ||

| Nose | Unknown (Egypt) (1) | 1 |

| Teeth | Etruria (Italy) (1); Bisenzio (Italy) (1); Lake Bolsena (Italy) (1); Orvieto (Italy) (2); Chiusi (Italy) (1); Populonia (Italy) (1); Tarquinia (Italy) (5); Vulci (Italy) (2); Valsiarosa (Italy) (1); Teano (Italy) (1); Praeneste (Italy) (1); Satricum (Italy) (1); Bracciano (Italy) (1); Tanagra (Greece); Sardis (Turkey); Sidon (Lebanon) (2); Alexandria (Egypt) (1); El-Qatta (Egypt) (1); Tura El-Asmant (Egypt) (1); Eretria (Greece) (1); Rome (Italy) (1); Jersualem (Israel) (4) | 32 |

| Hair | Les-Martres-de-Veyre (France) (3); Rainham Creek (England) (1); York (England) (1); Vindolanda (England) (1); Newstead (Scotland) (1); Dush (Egypt) (2); Gurob (Egypt) (1); Harit (Egypt) (1); Unknown (Egypt) (2); Rome (Italy) (2) | 15 |

| Eyebrow | ||

| Phallus | ||

| Total | 55 |

It is likewise crucial that archaeological and bioarchaeological evidence for prostheses be treated critically.Footnote 125 While some of the surviving ancient prostheses, such as the ‘Hemmaberg Limb’ and the ‘Povegliano Veronese Hand’, have been discovered only very recently, and as a result have been excavated carefully and scientifically analysed as rigorously and comprehensively as possible, most surviving ancient prostheses were discovered a century or more ago, and little, if anything, is known about their provenances.Footnote 126 In the case of the Capua Limb, while the prosthesis was excavated, recorded, photographed, and sketched carefully, it was subsequently destroyed in an air raid during the Blitz and only a partial replica survives today. Where possible, I have visited museums and examined both original and replica prostheses, and, where it exists, their accompanying documentation, to get a sense of the objects themselves. This has provided me with insights regarding their design, creation, and usage that I would not otherwise have had, and I have applied these insights to what follows.

Outline

This monograph will examine the prostheses, prosthesis use, and prosthesis users of classical antiquity from several different angles. My aim is to answer the following questions: How common – or uncommon – were prostheses in classical antiquity? Who made them? How did they make them? Why did they make them? Who used them? How did they use them? Why did they use them? How were they – and their prostheses – viewed by other members of ancient society as a result? I shall do this by focusing on each type of prosthesis that we have ancient evidence – literary, documentary, archaeological, bioarchaeological – for in turn. Where relevant, I shall also consider evidence for other types of assistive technology, such as walking sticks, canes, crutches, and walking frames that were used in conjunction with prostheses.

The first chapter, Extremity Prostheses and Assistive Technology, will explore the numerous ways in which extremities ranging from fingers, hands, and arms to toes, feet, and legs could be lost, and how prostheses were utilised as a means of substitution. It will survey the ancient literary evidence for extremity amputation and prosthesis use, and study in detail the archaeological remains of extremity prostheses and the bioarchaeological remains of individuals who utilised them. The second chapter, Facial Prostheses, will explore the numerous ways in which parts of the face – eyes, nose, teeth – could be lost, and how or even if prostheses were utilised as a means of substitution. Unlike with extremity prostheses, the evidence for facial prostheses, particularly prosthetic eyes and noses, is limited and enigmatic. The third chapter, Hair Prostheses, will explore the type of ancient prosthesis for which the evidence is most plentiful: the wig or hairpiece. Yet, although wigs and hair pieces are so well attested in the classical world, that is not to say that their interpretation is straightforward. It will survey the ancient literary evidence for wig and hairpiece use, and study in detail the archaeological remains of wigs and hair pieces and the bioarchaeological remains of individuals who utilised them. The fourth chapter, Design, Commission, and Manufacture of Prostheses, will survey the evidence for the process of commissioning, designing, and manufacturing a prosthesis, and consider the materiality of ancient prostheses and other types of assistive technology. The fifth chapter, Living Prostheses, will consider the extent to which other people, primarily the enslaved, and animals, such as dogs or apes, served as ‘living prostheses’, and either supplemented prosthesis use or rendered it unnecessary.Footnote 127 It will explore how this process of requisitioning the body of another entity was rationalised.

Ultimately, the aim of this monograph is to fill the current gap in scholarship and offer a new insight into the lived experience of the impaired and disabled in classical antiquity, thereby contributing to the study of impairment and disability in classical antiquity, the history and archaeology of medicine in antiquity, and social and cultural history.