In ‘Mental Cases’, Wilfred Owen gives us an unflinching account of the indelible images of violent death which continued to haunt some men’s minds even when they were removed from the actualities of the war. In depicting the particular hell of these ‘mental cases’, he also presents us with the close, detailed observation of death which most combatants experienced. ‘Wading sloughs of flesh’ and ‘treading blood from lungs’ remind us that soldiers might be literally knee-deep in the bodies of others; ‘shatter of flying muscles’ catches the way flesh could be blown to fragments, spattering the still-living. ‘Carnage incomparable, and human squander / Rucked too thick’ emphasises the sheer quantity of the butchery. Here, Owen sees soldiers’ deaths uncompromisingly as ‘multitudinous murders’ but, in other poems, he variously focuses on the dead body with an angry distress born of tenderness (‘Futility’), treats the ubiquity of death with bitter irony in the voice of the ordinary soldier (‘A Terre’), catches the moment of death in furious battle (‘Spring Offensive’) and imagines the dead of both armies conversing in the caverns of hell (‘Strange Meeting’). And that is only one poet. In this first chapter we foreground the central subject of our book – the way we remember through poetry the soldiers killed in the First World War – by looking at a range of poetic representations, written during the war and just afterwards.

All poets living through the First World War, whether combatant or not, were faced with the task of representing experiences which were so far from normality that they must have sometimes seemed to defy representation. In ‘Mental Cases’ Owen reaches for a grotesquerie of language, resonating with a deliberately Shakespearean timbre, to answer to the excesses of tragic horror he depicts. We see poets of this era continually seeking different forms and voices, sometimes stumbling, sometimes erring towards bathos or sentimentality, as they try to give expression to what might seem inexpressible.

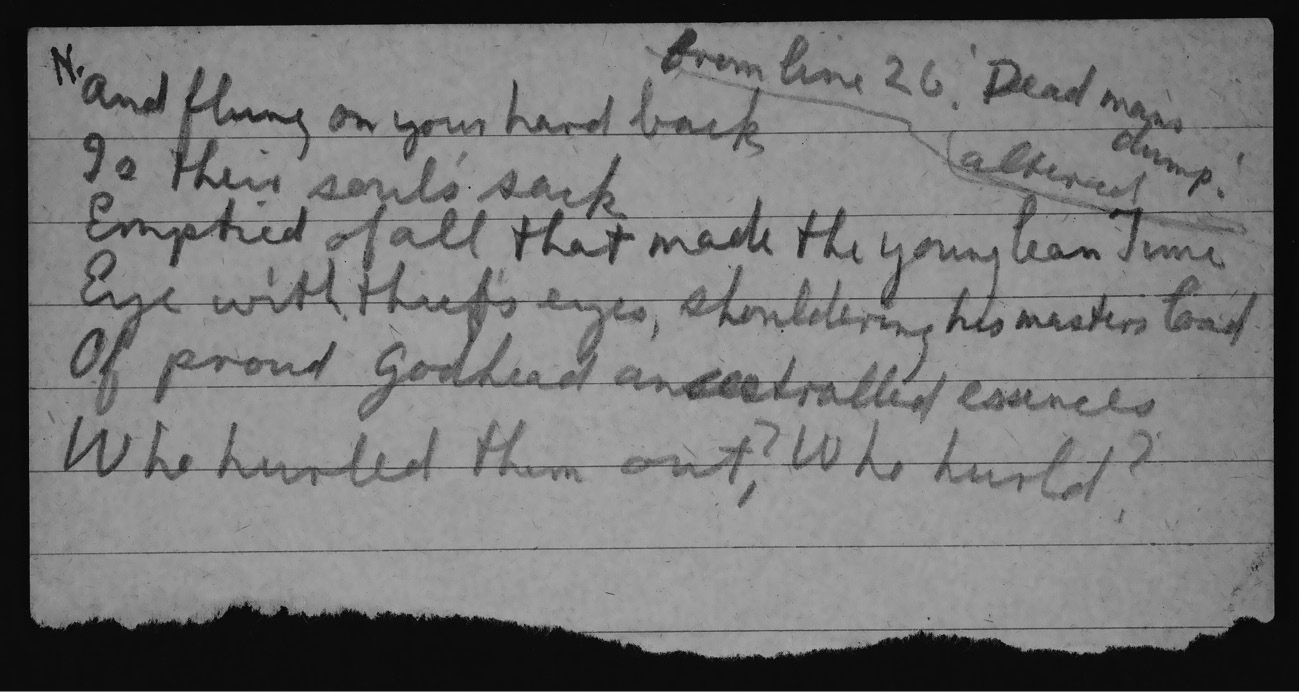

As the memory theorist Jan Assmann suggests: ‘The rupture between yesterday and today, in which the choice to obliterate or preserve must be considered, is experienced in its most basic and … primal form in death.’Footnote 2 This imperative was intensified on the front line, where death was ever-present and often both sudden and obliterating. To witness such deaths at close quarters must have been traumatic enough in itself; to this was added the imminent likelihood of one’s own death. As Edmund Blunden writes, ‘The more monstrous fate / Shadows our own, the mind swoons doubly burdened’, reflecting the fact that, when a poet wrote about the death of a fellow soldier, he was also imagining his own extinction.Footnote 3 The existential vertigo this could produce was a challenge to capture, and it is not surprising that poets sometimes chose to veil or elide it. At the same time, combatant poets – indeed all combatants – had little time or space in which to reflect properly, as is evident sometimes in the content of the poems, but more notably in the materiality of surviving texts. While some poetry was written on leave or in training camps, or behind the lines, much was also written in the front line, on scraps of paper, backs of envelopes, with stubs of pencils (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Isaac Rosenberg’s amendment to ‘Dead Man’s Dump’, included in a letter to Gordon Bottomley, 20 June 1917.

So the poet was faced with the large questions of life and death, made inescapable by the present actuality of the corpse – ‘the lawn green flies upon the red flesh madding’ – yet he might barely have had time to put pencil to paper, if indeed he had pencil and paper.Footnote 4

There was the further problem that the poetic tradition on which these writers characteristically drew often failed when they tried to use it to express their current experiences and reflections. The classical and epic repertoire was enmeshed with deeply heroic values which the mechanical slaughter of the First World War undermined; the Romantic poets’ pastoral redemption was swamped by the muddy wasteland of the Front. Edgell Rickword comments on the gulf between the literary tradition and the actuality of death on the line in ‘Trench Poets’, where the speaker attempts to cheer a corpse with various poems from the Metaphysical tradition:

The issue of representation was then both a human and an artistic problem for the poets of the First World War. It was compounded by the demands of public representation at home which remained true to the ideal of honour and noble sacrifice (even when, as sometimes with press reportage, those writing were privy to the more complex underlying picture). Such representation often issued in government-led propaganda, with a number of prominent poets enlisted in its service.Footnote 6 The misrepresentations of propaganda, combined with the censorship and self-censorship at the Front, made it difficult for those at home to have any idea of the realities of trench warfare. The bursting apart of values along with bodies did not penetrate the Home Front except in rare cases, and the private representations of non-combatants struggled with the realities of a world entirely other than that experienced at home. This struggle presented itself in an acute form to those who were writing poetry in response to the war. And this in part revolved also round competing ideas of poetic representation – what a poem should be at this time, and how to represent war and the experience of war in a poetry that would be seen as good.

In looking at the way these poets represented dying, death and those killed, we also begin to consider the developing processes of remembrance and commemoration. The poets writing out of the heat of the First World War were forming the first literary expressions of a shared grief. The nature of remembering and remembrance was an inherent concern for any poet in the front line: these were poets acutely aware of posterity, not so much in relation to their own poetic reputation, but in terms of constructing a memory. This memory might have been specific, personal, individually commemorative, or it might have been more overtly political and historical, seeking to represent a particular view of what death meant in this war. In the event, the memories these poets constructed helped to create a particular understanding of their historical moment: their poetry contributed to the formation of collective memory.

We look first at the very nomenclature poets used for those who died, since this linguistic choice was part of the first formation of memory about this historical moment, as well as the first commemoration of those who died. The versions of address to, and description of, the dead that were passed down affect current formations of memory and the choice of commemorative languages used to mark the First World War’s centenary. For even to talk of ‘the dead’ is to make a choice about how we remember, since it generalises and removes us from the specific individuals who were killed. At the same time many of the early poems make another sort of choice, bringing the dead back to life, contradicting the actuality occasioning the poem. The most common form of resurrection is to speak to those who have died as though they were present. Thus Ivor Gurney, in his retrospective ‘Farewell’, can’t help addressing his dead comrades as ‘you dead ones’, as if they might still hear him, unable quite to grasp even now – ‘But you are dead!’Footnote 7 Sassoon similarly addresses his great friend Robert Graves in ‘To His Dead Body’: ‘Safe quit of wars, I speed you on your way’ (Graves had been mistakenly listed as ‘Died of Wounds’ and when the poem was written Sassoon believed him dead).Footnote 8 May Wedderburn Cannan expresses the particular impotence of women left behind to mourn, speaking to her dead lover in ‘Lamplight’ (‘You took the road we never spoke of’).Footnote 9 Only Gurney amongst these meticulously speaks of ‘you dead ones’, and addresses some of them by name, in one of his many breaches of poetic convention. But it is clear too in both Sassoon’s and Wedderburn Cannan’s poems that a particular, known person is being addressed and, in that address, he is being thought of as in some sense still able to hear what the poet is saying.

Elsewhere, poets make the dead men themselves speak to us, in a kind of prosopopoeia, as in John McCrae’s ‘In Flanders Fields’.Footnote 10 Here, however, they have again become a mass, a generalised not an individual body, the capitalised ‘Dead’:

These ways of imagining dead soldiers refuse to accept the very fact that occasions the poem: their lives are over. The dead are not entirely dead, these poems say; they can hear us, see us, admonish us. This idea of the dead persisting in the living world may sometimes spring from a specific religious conviction about the survival of the soul after death; but more frequently the dead are imagined as embodied, sentient and either speaking or hearing. In terms of the response of collective memory to the death of our fellow humans, this is perhaps a particularly striking cultural expression of what Jan Assmann calls ‘an act of resuscitation performed by the desire of the group not to allow the dead to disappear but, with the aid of memory, to keep them as members of their community and to take them with them into their progressive present’.Footnote 12

These hallucinatory re-appearances of the dead to the living have become a standard phenomenon in the fiction which reimagines the First World War, starting with Virginia Woolf’s depiction of the dead Evans appearing to Septimus Warren Smith.Footnote 13 Whether such disruptions of ‘normal’ reality are the product of the extreme psychological pressures of combat, or of the stress of personal loss, the sense and even the material apprehension of the dead person existing after death is likewise a familiar epiphenomenon of bereavement. The pathological nature of hallucinatory reappearances of the dead to the living reminds us that the idea of a dead man somehow continuing to live is not necessarily benign. Far from being a comfort, there is a horror in the irrepressible irruption of the dead into the minds of men who want only to forget them, as Owen’s ‘Mental Cases’ vividly depicts. This disjunction enters the poetic discourse of the First World War. On the one hand, there is a fear of seeing the dead rise up again, because that means the memory of all that death can never be extinguished – hence ‘Memory fingers in their hair of murders’. On the other, if the dead man can be imagined as sentient enough to enjoy the peace of death, to still be able to hear the poet address him, or indeed to speak himself, then death becomes less fearful to those still living, as well as offering consolation about how the dead themselves ‘feel’.

The desire to keep the dead alive was perhaps more acute and more sustained in the First World War precisely because of the numbers of dead.Footnote 14 Those who wrote poetry might naturally, then, take it a step further and give voice to or address those who had died. But perhaps the more powerful influence was poetic convention, notably that of the elegy, which simultaneously weeps for the dead person and addresses him as shining through all eternity. The acme of this poetic expression of an ever-persisting life for those who are dead can be found in Rupert Brooke’s five sonnets, published originally in New Numbers in early March 1915, and then republished in 1914 and Other Poems, hastily assembled by Edward Marsh after Brooke’s death in April, and published posthumously in June 1915.Footnote 15 This was an immensely powerful text in its historical moment, and that moment has reverberated to the present day. Brooke’s sonnets are undoubtedly an example of both the formation and the transmission of cultural memory. Here we’ll look at those five sonnets as the expression, early in the war, of a particular sort of feeling about death in battle, and as the epitome of one sort of poetic remembrance which contributes powerfully to cultural memory. These poems were deeply resonant and highly influential, and became for a time a touchstone against which both other poetry and soldierly and masculine behaviour and values were measured. The extent to which Brooke’s poetic contemporaries either conformed to or departed from his poetic world view is thus a useful starting point to look at the range of poetic responses to death in the First World War, and at the complex problem of how best to remember ‘you dead ones’ in poetry.

In using Brooke’s sonnets as both index of and point of contrast to the ways other poets represented and commemorated those who died, we will refer to the theories of memory touched on above. We will also draw, in this chapter and elsewhere, on two recent commentaries on the way the rhetoric of mourning in First World War poems is rooted in traditional forms but at the same time departs from those conventions in response to the particularity of the experience of death, loss, mourning and remembrance in the First World War. In the first, Jahan Ramazani argues that, while elegy as a genre remains significant in the twentieth century, it must be an altered elegy to represent an altered world; one of his examples of this altered elegy is the poetry of Wilfred Owen.Footnote 16 In the second, Elizabeth Vandiver reaches even further back to the representations of death in battle in classical epic, showing the deep influence of classical tropes on First World War poets, especially those who were steeped in that tradition through their public school education.Footnote 17 There is an inherent link between Ramazani’s and Vandiver’s work in that the elegy of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries itself draws on classical models, often ossified into literary conventions in the formal elegy. In Brooke’s sonnets we see both influences at work – the atavistic appeal of the unaltered formal elegy, decorated with the spiritual paraphernalia of death in battle as represented in classical epic. From elegy come the tropes of the dead body being at one with nature and thereby still having life, providing consolation and redemption both through that and through the act of commemoration in the elegy itself. From martial epic comes the idea that only through battle can a man’s qualities be tested, and that the normal values of the peaceful world are mean and, in the end, meaningless – ‘all the little emptiness of love!’Footnote 18

Brooke completed a draft of the sonnets towards the end of December 1914, while at training camp, and by mid-January they were in proof stage ready for New Numbers.Footnote 19 He had volunteered only a few weeks after the outbreak of war and, in October 1914, after minimal training, his company was sent to Antwerp to reinforce Belgian troops; this turned almost immediately into a retreat. Brooke describes his relief, ‘to find I was incredibly brave!’, revealing, rather touchingly, in the next sentence that his bravery hadn’t yet been much tested: ‘I don’t know how I’d behave if shrapnel were bursting over me and knocking the men round me to pieces.’Footnote 20 So he didn’t see combat of the sort that Owen, Sassoon, Gurney, Rosenberg and others would see at the Front, though not for want of trying. The sonnets are, then, written out of only a very brief experience of a soldier’s life. But as the poetry of Harold Monro and Wilfrid Gibson – both non-combatants writing early in the war – shows, lack of experience is no barrier in itself to an imaginative understanding of what death in battle might be like.Footnote 21 And it’s not as if Brooke lacked the necessary imagination; in the same letter describing his reaction to active service, he mentions writing final letters before action:

I felt very elderly and sombre, and full of thought of how human life was a flash between darknesses, and that x per cent of those who cheered would be blown into another world within a few months … it did bring home to me how very futile and unfinished life was… There was nothing except a vague gesture of good-bye to you and my mother and a friend or two. I seemed so remote and barren and stupid. I seemed to have missed everything.Footnote 22

This is the note of futility and existential absurdity that we find in some of the most interesting poetry of the war: note that Brooke says not It but I seemed ‘remote and barren and stupid’, transferring the sense of alienation to his very self. There is a similar note of the understood void that future death represents in ‘Fragment’ (entitled posthumously by Marsh), written in April 1915 just before his death, where he foresees, as he wanders on the ship’s deck at night, that ‘This gay machine of splendour’ would ‘soon be broken, / Thought little of, pashed, scattered’. Seeing the live bodies of his shipmates through the saloon’s lamplit window while he remains unseen outside, he understands that they are already ‘coloured shadows, thinner than filmy glass, slight bubbles … Perishing things and strange ghosts – soon to die’.Footnote 23

Yet there is not an iota of that existential anxiety in the sonnets; their tenor owes more to the literary traditions in which he was steeped than to the force of his experience. ‘Fragment’ was not included in 1914 and Other Poems (1915), but it was published in the subsequent, highly popular Collected Poems of 1918, which ran to sixteen impressions before a revised edition appeared in 1928. However, as a small but significant counter-voice to the tone of the sonnets, it went unnoticed, and remains so now.Footnote 24 The sonnets, conversely, were widely promulgated and embody a number of standard values which were broadly shared at the beginning of the war, at least by the officer class, since many of them derived from the classical models in which the officers were educated. Central was the idea that ‘God … has matched us with His hour’, which underwrites the belief that war provided a unique challenge to manhood to prove its finest qualities, and so men should be grateful for this chance that history has given them.Footnote 25 Inevitably, therefore, death became a necessary – the necessary – risk, and had to be depicted as part of the general good. In the first of two sonnets entitled ‘The Dead’ (sonnet III), indeed, death becomes a positive gain since, if one makes the ultimate sacrifice in a challenge set by God and country, death becomes the best prize. Vandiver goes so far as to say that Brooke sees such a death as the sine qua non of a happy life, and that, in sonnet III, he ‘appropriates classical tropes to delineate the requirements for human happiness’.Footnote 26 In his opening sonnet, ‘Peace’, Brooke couches that sacrifice in terms of a Christian God, but when reflecting on being sent to the Dardanelles it is of the Trojan War and the classical gods, not God, that he thinks. Vandiver notes ‘the complexity with which classical, medieval and Christian imagery intertwined in the minds of public-school graduates to support the insistence that the deaths of … young men … were not only necessary but glorifying’.Footnote 27 Thus for Brooke the ‘Dead’ are ‘rich’ and in dying they offer ‘rarer gifts than gold’, ‘Honour has come back, as a king, to earth’ and ‘we’ (men who fight) ‘have come into our heritage’ (‘The Dead’, sonnet III).

There is no room in this set of values for either the grisliness or the existential absurdity of death. Rather the imagery of cleanness, beauty and wholesomeness accompanies any reference to the body – ‘swimmers into cleanness leaping’ (‘Peace’), ‘Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home’ (‘The Soldier’, sonnet V), ‘pouring out’, not blood, but ‘the red Sweet wine of youth’ (‘The Dead’, sonnet III). Even when the body is buried, ‘There shall be / In that rich earth a richer dust concealed’ (‘The Soldier’). Perhaps most powerful in Brooke’s vision is the idea, written into the very grammar and syntax of the lines, that the dead body will somehow know the peace that spells the end of life. Certainly, this is a common conception for anyone trying to grapple with the idea of death, since it is difficult for us, alive, to think of the state of non-being. Being faced with bodies suddenly, regularly and randomly annihilated would make it difficult to accept this consoling fiction, that the dead can feel the peace that comes with the loss of sentience. Yet this is precisely what Brooke envisages: ‘a body of England’s, breathing English air, / Washed by the rivers, blest by the suns of home’ (‘The Soldier’). The strength of Brooke’s sonnets, and what perhaps led them to be so influential initially, is the fact that his poetic values are of a piece with his moral values. There is no room for questioning or doubt, as he forges a complete and consistent set of images in which the reality of an actual body torn apart cannot possibly insert itself. Instead, richness, cleanliness, safety, beauty, comfort and peace are all stitched in not just to the vocabulary but to the tight form of the sonnet.

Jan Assmann, specifying the characterising features of cultural memory (in the context of Egyptology), suggests that it is defined in part by its ‘specialised tradition bearers’, those figures who represent what, in a different conceptual framework, we might call the dominant ideology.Footnote 28 If Brooke was a bearer of that ideology – born and brought up first in the environs of and then, from the age of three, within Rugby School when his father became housemaster of the School Field House; educated in his father’s House; classical scholar at King’s College Cambridge, where his uncle was Dean; a member of the Cambridge Apostles as an undergraduate, then appointed to a Fellowship at King’s; highly literate and literary, well-travelled and extremely well-connected – he was also a victim of it. When Brooke was looking for a way into the war, Edward Marsh, his great friend, admirer and literary promoter and also Winston Churchill’s Private Secretary, eased the way for him to join the Royal Naval Division, one of Churchill’s pet projects. That led to Brooke’s brief skirmish in Belgium, after which he drafted the 1914 sonnets. Then he was off to the Dardanelles, another of Churchill’s ventures, this to prove disastrous. For Brooke and his fellow officers, steeped in Greek poetry, to fight in Gallipoli was tantamount to refighting the Trojan War. While Brooke’s letters on the subject are infused with self-reflexive irony, there’s no doubt about his excitement at this coincidence of geography and value. He writes to Violet Asquith, ‘Oh Violet it’s too wonderful for belief … I’m filled with confident and glorious hopes… Will Hero’s Tower crumble under the 15 in. guns? Will the sea be polyphloisbic [roaring loudly] and wine dark and unvintageable?’Footnote 29

Brooke, at this early stage of the war, and with no actual experience of ‘shrapnel … bursting over me and knocking the men round me to pieces’, clearly reaches back to both his classical and his English literary antecedents, in a way one might almost describe as innocent. Brooke’s sonnets then would, in Halbwachs’s and the Assmanns’s terms, be seen as culturally determined, by his class, his education and his literary understanding. Astrid Erll notes, in discussing the Assmanns’s concept of cultural texts: ‘In uncommon, difficult, or dangerous circumstances it is especially traditional and strongly conventionalised genres which writers draw upon in order to provide familiar and meaningful patterns of representation for experiences that would otherwise be hard to interpret.’Footnote 30

We can see then the way that Brooke, at this time of personal and national danger, naturally reached for the comforting genres of epic and elegy, and the values they embody, and went to the familiar and canonical form of the sonnet as a means of expression of those values. Epic is a founding cultural text and repository of cultural memory, but also a key generic carrier of ideas about war; elegy is founded on certain classical values and tropes, embodying an inherently consolatory and redemptive attitude to death and mourning; and the sonnet is the axiomatic English lyric form, contained and controlled but expressive of deep personal emotion. Thus Brooke reached back, against the pull of modernity, to a deeply conservative understanding of death in battle. Brooke answered perhaps to a precise ideological moment, just before he could be exposed to the bleak failure and human cost of the Gallipoli campaign.

The responses to Brooke’s death were equally closely entwined with ideology, but less innocently so. Even before Brooke’s death, ‘The Soldier’ had been picked out by the Dean of St Paul’s to feature in his Easter sermon. Immediately after his death, the man and his poems were conflated as a prime example and expression of patriotic masculine sacrifice. In Churchill’s encomium for Brooke as lost hero, published in The Times of 26 April 1915 (Brooke had died three days earlier), we can see the turning of the man and his writings into a combined lieu de mémoire, which would go on to be endlessly re-sacralised.Footnote 31 This secondary movement, which turned Brooke and his sonnets into a myth, rendered his poetry even further regressive, un-individualised and ultimately in the service of state memory. Canonised, in both senses, by a premier politician, and a premier churchman, Brooke and his poetry had little chance to be anything other:

Rupert Brooke is dead… A voice had become audible, a note had been struck, more true, more thrilling, more able to do justice to the nobility of our youth in arms engaged in this present war, than any other …

During the last few months of his life, months of preparation in gallant comradeship and open air, the poet-soldier told with all the simple force of genius the sorrow of youth about to die, and the sure triumphant consolations of a sincere and valiant spirit. He expected to die; he was willing to die for the dear England whose beauty and majesty he knew; and he advanced towards the brink in perfect serenity …

The thoughts to which he gave expression in the very few incomparable war sonnets which he has left behind will be shared by many thousands of young men moving resolutely and blithely forward into this, the hardest, the cruellest, and the least-rewarded of all the wars that men have fought. They are a whole history and revelation of Rupert Brooke himself. Joyous, fearless, versatile, deeply instructed, with classic symmetry of mind and body, he was all that one would wish England’s noblest sons to be in days when no sacrifice but the most precious is acceptable, and the most precious is that which is most freely offered.Footnote 32

Max Egremont notes, in passing, that Marsh was in fact the author of this eulogy, which would explain its note of hectic dolour.Footnote 33 But Churchill certainly knew what he was doing, hitching his own wobbling reputation to a star which he was himself helping to create. As a politician he was taking power from a dead soldier-poet by iconising him at the moment when the cultural memory of this occasion was in the process of being formed.

The absences in this passage are as interesting as the presences. Churchill had initiated the two engagements that Brooke had been involved with, Antwerp and Gallipoli, both of which were strategic failures. This is turned on its head into the paradigm of noble sacrifice which Brooke’s sonnets encapsulated. And no mention is made of the cause of Brooke’s death – weakness brought about by sunstroke, followed by septicaemia caused by an unnoticed insect bite. The lacuna leaves the reader to imagine a glorious death in battle. Brooke’s sonnets are marked by the same lacunae; the physical nature of death is displaced into absence by the idiom and ideology that marked the start of the war, themselves underwritten by Homeric values, and promulgated in the public and private schools which produced most junior officers.

In the months and years after his death, versions of Brooke were constructed as both communicative and cultural memory simultaneously. We can see this process at work in Virginia Woolf’s contemporary responses. In a Times Literary Supplement review (27 December 1917) of John Drinkwater’s Prose Papers, she commends his piece ‘Rupert Brooke’ because it does not simply assent to the poet’s ‘canonisation’. She ends the review with an exhortation: ‘If the legend of Rupert Brooke is not to pass altogether beyond recognition, we must hope that some of those who knew him … will put their view on record and relieve his ghost of an unmerited and undesired burden of adulation’.Footnote 34 When Edward Marsh’s The Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke was given to Woolf to review by the Times Literary Supplement, she had the perfect opportunity to fulfil the duty she had outlined, to put her more complicated view of Brooke ‘on record’. Indeed, she described Marsh’s memoir as ‘a disgraceful sloppy sentimental rhapsody’ – but only in her private diary.Footnote 35 In her review of 8 August 1918, in spite of the protection of anonymity, she was much more cautious, repeating only that ‘those who knew him’ (implying that Marsh didn’t) would be left ‘to reflect rather sadly upon the incomplete version which must in future represent Rupert Brooke to those who never knew him’.Footnote 36 She thus did not take the opportunity to deconstruct the myth she knew was being made. An explanation of sorts is given in a letter to Katherine Cox, Brooke’s former lover, admitting that she is the author of the review: ‘when it came to do it I felt that to say out loud what even I knew of Rupert was utterly repulsive, so I merely trod out my 2 columns as decorously as possible’.Footnote 37 The reluctance which even Woolf (in a position at that time of some cultural influence) felt to speak ‘out loud’ shows the power of cultural pressure on the individual – though rarely are its workings so clearly revealed.

Had Brooke survived to experience more fully the horrors of war, his poetic representations might have been different, and the cultural representation of him and his work would have changed accordingly. His merging Gallipoli with Troy, and seeing the waters he crossed towards his death as ‘wine dark’, may have been collectively and culturally formed, but they remain an aspect of his individual consciousness, which consciousness might have been changed by different experiences. Charles Sorley was raised ‘upon the self-same hill’ of classical literature as Brooke.Footnote 38 However, Sorley’s response seems to have been to see not the richness but the blankness of death, at least in his most famous poem, ‘When you see millions of the mouthless dead’. His emphasis is on that ‘mouthless’: they cannot speak and perhaps, too, they are literally mouthless. Indeed all the senses are missing; he warns the reader not to imagine that the dead can hear our praise:

He tells us not to cry for them (‘Their blind eyes see not your tears flow’), nor to honour them, because:

Vandiver notes that Sorley refers directly here to the passage in the Iliad where Lycaon, the son of Priam, begs Achilles for mercy, and Achilles responds by reminding him that ‘Patroclus too has died, who was far better than you.’Footnote 40 The import is that all come to death; being good, being powerful in battle, being Patroclus himself, makes no difference. But Sorley is not reminding us here of the truism that all are equal in death, in the manner of Thomas Gray’s ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’, but rather that, if even such a great one as Patroclus must die, then all deaths are equally meaningless. Sorley set great store by this passage, asserting in one of his letters to his old headmaster at Marlborough that it ‘should be read at the grave of every corpse in addition to the burial service’.Footnote 41 Echoes of his bleak view are already there in his 1914 poem, ‘All the hills and vales along’:

This, however, is a poem of a very different tone, fostered by the sing-song rhythm and rhyme which puts the serious and non-serious on the same level to reflect nature’s indifference. In ‘When you see millions of the mouthless dead’, Sorley, like Brooke, calls on the sonnet form to give his vision a greater gravitas but, in doing so, he shows us that this form can also be framed to cut against tradition. Customarily, a sonnet will have some kind of ‘turn’ or change in direction in its final section, and Sorley seems about to make such a turn, though later than usual, in the last quatrain, offering the possibility of hope, of contact beyond the grave:

But he quickly withdraws this in the next line, by completing the sentence with these four words: ‘It is a spook’, and adding: ‘None wears the face you knew.’ The dead are dead, and all we can say about it is: ‘They are dead.’ To say otherwise is a falsehood. For all its being so closely informed by Sorley’s classicism, this sonnet is a great negation of the very values the Iliad upholds.

If Brooke’s sonnets are prime examples of hegemonic texts embodying the dominant ideology, Sorley’s last sonnet is a triumphantly individualistic counter-example to the power of that hegemony. Using a traditional verse form, and drawing on his own deep classical learning, he deliberately rejects the language, iconography and values of Brooke’s sonnets. His considered response to those sonnets (made only a few days after Brooke’s death) was that the poet was ‘far too obsessed with his own sacrifice, regarding the going to war … as a highly intense, remarkable and sacrificial exploit’. His summary judgement was that ‘he has taken the sentimental attitude’ (an interestingly ambivalent phrase since it can apply to both moral and poetic values).Footnote 43 ‘When you see millions of the mouthless dead’ may be a deliberate riposte to that attitude.Footnote 44 Certainly it subverts elegy in the way Ramazani suggests a properly modern elegy should, to the point of being an anti-elegy: ‘In becoming anti-elegiac, the modern elegy more radically violates previous generic norms than did earlier phases of elegy: it becomes anti-consolatory and anti-encomiastic, anti-Romantic and anti-Victorian, anti-conventional and sometimes even anti-literary.’Footnote 45 Such a literary poem can’t really be said to be anti-literary, but it does use its poetic reference points to undermine the standard tropes of elegy, and in so doing is one of the few First World War lyrics to cast the authentically cold eye of modernity on the predicament of remembering the dead. Even the apparent generalisation and reification of the ‘millions of the mouthless dead’ is there to remind us that death nullifies the individual, not by rendering him a part of a greater whole (‘the dead’), but by making him anonymous. ‘None wears the face you knew’. No one is left.

While those at the Front saw ‘the mouthless dead’ on a regular basis, those at home were given false constructions of such deaths. The disjunction between the reality of life and death at the Front and the way that was represented at home is well documented and contributed further to the difficulty that serving soldiers had in making sense of their experiences on active service, so utterly at odds with the banalities of home life but also at odds with the way their experiences were being reported at home, and being received. This is poignantly evident in the correspondence about Brooke between Vera Brittain and Roland Leighton. Indeed Brittain herself comments in her memoir Testament of Youth on that gulf of experience, made worse by the delay between letters sent and those received, speaking of ‘that terrible barrier of knowledge by which War cut off the men who possessed it from the women who, in spite of the love that they gave and received, remained in ignorance’.Footnote 46 Roland Leighton, known best now as Brittain’s fiancé, was, like Brooke, deeply versed in classical literature and its ethos. In July 1914, as he left Uppingham School, he was laden with prizes for Greek and Latin, and had won a Classical Postmastership to Merton College, Oxford.Footnote 47 He left school with the words of his headmaster in his Speech Day address ringing in his ears: ‘If a man cannot be useful to his country, he is better dead.’Footnote 48 By October 1914 he had enlisted as a second lieutenant, and was continuing to write promising poetry. In March 1915, his regiment was sent to the Front. In all these ways his path mirrored Brooke’s, though his family was more bohemian. In August 1915 Vera sent Leighton a copy of the recently dead Brooke’s newly published Poems 1914, expecting, not unnaturally, that he would share the ideals expressed there. Leighton’s initial response was frustration that he himself had not achieved as he had wished. At the same time, he issued a muted challenge to Brooke’s ideas: ‘it is only War in the abstract that is beautiful’.Footnote 49 His more deeply felt response came, however, in September, a few weeks after the leave in which he and Vera had become officially engaged. In this letter to her, he describes the dead bodies he has seen, making bitter reference to Brooke’s sonnet III and to the values of the five sonnets in general:

… in among the chaos of twisted iron and splintered timber and shapeless earth are the fleshless, blackened bones of simple men who poured out their red, sweet wine of youth unknowing, for nothing more tangible than Honour or their Country’s Glory or another’s Lust of Power. Let him who thinks War is a glorious, golden thing, who loves to roll forth stirring words of exhortation, invoking Honour and Praise and Valour and Love of Country … let him but look at a little pile of sodden grey rags that cover half a skull and a shin bone and what might have been Its ribs, or at this skeleton lying on its side … perfect but that it is headless, and let him realise how grand and glorious a thing it is to have distilled all Youth and Joy and Life into a foetid heap of hideous putrescence. Who is there who has known and seen who can say that Victory is worth the death of even one of these?Footnote 50

This passage is the more remarkable in that Leighton is responding to seeing the dead bodies of German soldiers.Footnote 51 He had been at the Front for seven months; he was twenty; it was relatively early in the war. Leighton is angry with himself, and with the entire ethos of his youth – embodied in his school, his many prizes and his classical learning – which he had embraced so willingly. He is angry with Brooke for so powerfully voicing that ethos in his sonnets. And he is, implicitly, angry with his beloved Vera for sharing those values – though she went on praising Brooke to Roland in her letters, apparently oblivious to the source of his bitterness.Footnote 52

Leighton had, a few months earlier in April 1915, written ‘Violets’, addressed to Vera but not sent at the time of writing, though he sent her some of the actual violets which it describes.Footnote 53 The poem has a softness and tenderness missing from his angry letter – it is a love poem, and it is written only a couple of weeks after Leighton’s arrival at the Front – but the contrast it draws is the same:

The simple oppositions of this poem derive from Leighton’s address to his loved one at home, but they perhaps also reflect his own struggle to reconcile the beauty of the violets with the ‘soaked blood’ in which they grew. Beside the fierce, almost brutal, and precocious detachment of Sorley, and indeed beside the immense confidence of Brooke, Leighton’s poem betrays his poetic inexperience. But there is a poignant quality to his attempt to bring together the incompatible poles of his experience. This is a very young man trying to come to terms with the immediate experience of battlefield death.

These poets were struggling with how to represent rightly those who were being killed. Sorley’s depiction of ‘the dead’ as ‘mouthless’ and ‘millions’ is highly unusual. In First World War poetry ‘the dead’ (especially when capitalised as ‘the Dead’) often suggests a community of like-minded beings. Moreover, it turns an adjective into a noun so that we don’t have to say out loud what it is that’s dead; it deprives dead men of their bodies, makes them ethereal, insubstantial, spiritual. And that makes it easier to use abstract nouns like immortality, holiness, honour and nobleness, all of which appear in Brooke’s sonnet III, ‘The Dead’. Clearly there is a difference between the non-capitalised and the capitalised ‘dead’. But in general the poets who think in a more complex way about death invoke particular dead bodies rather than either ‘the dead’ or ‘the Dead’.

The most powerful of such poems are those which try to make sense of, or attend to the detail of, the act and moment of dying, rather than a generalised death, or the dead. If we step back here from the way the already-dead are depicted to look at the way First World War poets depicted the actual moment of dying, we see also a progression to some extent from the traditional mode of remembrance, with its attendant traditional forms and tropes, to a more obviously modernist enterprise. The ubiquity of death at the Front prompted (especially combatant) poets to dwell on the moment when the living consciousness ceased. This is perhaps the most mysterious moment but the most pregnant with meaning for those concerned with the existential. In its high modernist forms this issued in an acute interest in the nature of consciousness and ways of representing that accurately in language. In First World War poems which try to capture this moment, we see these conceptual and philosophical concerns worked out in the human landscape of those about to die, those dying and those just dead.

Isaac Rosenberg – who was also critical of Brooke’s ‘begloried sonnets’, telling one friend: ‘they remind me too much of flag days’ – brings his keen poetic eye to the detail of death in exactly this way in ‘Dead Man’s Dump’.Footnote 54

Here we see the acute difference between Brooke’s ‘the rich Dead’ and Rosenberg’s ‘sprawled dead’, the latter not dignified even by the definite article (though we will argue they are dignified in a different way). ‘Shut mouths’ is maybe not as strong a protest as Sorley’s ‘mouthless’, but it reminds us that someone else’s actions have actively shut these mouths. And the oxymoron of ‘pained them not, though their bones crunched’ captures the vertiginous existential ambivalence of the dead body. We are glad it feels no pain. But it feels no pain because it is dead. This is all the comfort we have; worse, this is all the comfort the dead body can’t have. He describes the stretcher-bearers leaving a just-dead man with the older dead bodies on the dump:

These lines recall Wordsworth’s exploration of this paradox:

Wordsworth’s Lucy is on a continuum with the ‘sprawled dead’; do we take comfort from Lucy’s neither hearing nor seeing, or do we shiver at the coldness of this rough universe? Rosenberg poses the same question, yet perhaps even more feelingly since we imagine the dead body at the same time both feeling and not feeling pain. Lucy is literally dead to the world; Rosenberg, in a modernist way, creates at once the sensation and the lack of sensation, allowing the two worlds to collide.

While Rosenberg begins uncompromisingly with the fact of being dead, and the numbers of the dead, his real interest is in that one brief moment between life and death. He tries to apprehend what lies beyond the body, if anything does, questioning that moment when the body dies:

He is ‘hurled’ – to where, and by what or whom, lies unanswered, unanswerable. Rosenberg doesn’t even allow us to rest there, bleak moment that it is. He pursues the feelings of the living:

He recognises here something difficult to admit, that the living are lucky – and they feel lucky; for all that someone else is dead, they are still alive, and in that moment they feel immortal as though the ichor that ran through the veins of the gods runs also through theirs. But this poem is a drama, moving us from stage to stage of the lived consciousness of death. No sooner than we have shared the understanding of the survivor’s sense of immortality, than dread strikes;

The existential drama of being glad to have survived (which must have carried a sort of elation as the odds were made visible by the surrounding dead) is immediately undercut by the terror of anticipating that ‘end’. In this way, Rosenberg constantly cuts against the imagined reality he himself has created. Drawn into thinking about the soul, or at least into thinking hopelessly that something must exist beyond the body (‘Somewhere they must have gone’), we are yanked back to the body:

Rosenberg can’t stray far, though, from that question of whether anything lies beyond; it is tied relentlessly to the barbarism of the crunching apart of the dead – or worse, the dying – body.

There is, too, a constant exchange between the dying and the living. Rosenberg echoes the human response in the muscular one; the stretcher-bearer slips his load when caught by the horror of a man’s brains splattering over him, but the shoulders bend again to pick up the stretcher, to take on the human weight though it is hopeless. By which time,

This might seem a natural ending to the poem, but Rosenberg pushes further, always trying to find the moment of death. He distinguishes between ‘this dead’ (‘the drowning soul … sunk too deep / For human tenderness’) and ‘the older dead’, lighting finally on ‘one not long dead’. He imagines this man’s last moments:

This is an anguished understanding. We feel the supplication of the dying man, but also his foresight; he knows he is about to die. In the drama of the poem, this is the moment where Rosenberg unites the initial ‘the wheels lurched over sprawled dead’ with this final, and particular, ‘the rushing wheels all mixed / With his tortured upturned sight’. It is here that we realise that the poem is returning to the poem’s beginning. The wheels that ‘lurched over sprawled dead / But pained them not’ are only now approaching the body of ‘one not long dead’. As ‘the choked soul’ reaches for ‘the living word’, so Rosenberg is reaching, like the dying man, for the moment between living and dying. In the end, he can only catch the moment of death as observed from outside, by the living:

As we are ejected from the poem by this image of apparent indifference, we may feel, like the soldiers and the observant poet, complicit in this death. But the care Rosenberg has taken throughout the poem, standing back from this moment while also giving it the full weight of his poet’s close gaze, makes that complicity also a compassionate one. We feel with and for the dying man whilst not softening the brutality of such a death in war. Rosenberg makes this a sort of recovery of the dead, but not the dishonest one proposed by Brooke; it recovers by paying proper heed.

At an earlier point in the poem, Rosenberg has toyed with a more conventional idea of the moment of death, that of the soul leaving the body in some almost-palpable form:

He envisages the spirit as a kind of a shadow (recalling the old idea of a shade, a ghost), and an exhalation, a wind. Vandiver connects Rosenberg’s passage beautifully with its Homeric antecedents, noting that for Homer the word psyche could mean breath (when passing from the dead body), soul (which survives in the underworld after death) and life (as in the Greek phrase for fighting for one’s life); she exemplifies these nuances of the word in Homer’s descriptions of the death of Patroclus and of Hector, and adds: ‘Rosenberg’s lines reflect these nuances, referring to spirits that leave the body at the moment of death … and also to “life” including the sense “breath”, when “the half used life” passes from “doomed nostrils and the doomed mouth”.’Footnote 57 What Vandiver misses, however, is that Rosenberg evokes the idea of the psyche rushing from the body, only to remove it: ‘None saw’ it leave the body. Here, as throughout the poem, Rosenberg eschews all standard forms of representing the dying. His is a unique gaze, which combines the depth of understanding of Homeric and elegiac tropes with a hard-eyed look at what actually happens. The mystery doesn’t disappear – the poem is littered with questions – nor are attempts to account for the mystery dismissed. But they are carefully displaced by reminding us of what he has seen.Footnote 58

It may be that Rosenberg’s marginality as an East End Jewish poet allowed him to remake a poetic tradition in which he was not fully steeped. In a world of increasingly mobile and disparate communities, the memory theorists’ notion of a coherent and determining collectivity loses some of its force. A further example is Mary Borden, an American émigré in London literary circles, who was able to incorporate the Whitmanesque in radical ways that transform the traditions of poetic commemoration. Her position as an incomer who set up her own hospital at the Somme, seeing at close quarters the damaged, dying and dead bodies of the poilu, was unique, and her poetry is unlike anything else written during this war. It is a Whitmanesque free verse, long, open and allusive. In one poem she writes of the mud as a character and a will with its own voice (‘Song of the Mud’); in ‘Unidentified’ she turns her relentless gaze – and so ours – on the ordinary man in the trenches, about to die and lose his identity at any moment.Footnote 59 Her poetic task is to identify him, by making us, as readers, look at him, look at him properly. Like Rosenberg, she pays due heed, but in a different mode. Hers is a philosophical look, and while it accommodates the fearful conditions of the trenches where ‘Death … suddenly explodes out of the dreadful bowels of the earth’, she really wants us to see man as a poor, bare, forked animal. He is also ‘Your giant – your brute – your ordinary man’; nothing about him is heroic, except that he stands up, and stays upright, even though

Borden’s is an extraordinary vision of the man who is about to die. She learnt this from working in ‘that confused goods yard filled with bundles of broken human flesh. The place by one o’clock in the morning was a shambles. The air was thick with steaming sweat, with the effluvia of mud, dirt, blood.’Footnote 60 Her reference to ‘a shambles’ echoes the view of many soldiers that the trenches most closely resembled an abattoir.

Despite the very wide differences in their cultural experiences, and despite their very different relations to the broad forces of cultural memory, Rosenberg and Borden show the same determination to hold an unflinching gaze on the dying or about-to-die man, in circumstances which threaten to render that man only an animal, in the sense of a beast without consciousness. Their humane insistence on seeing the man – the man containing the animal – derives surely from their common experience of the mutilated body, which unites them more than their differences separate them.

Poets affected by different social and cultural factors, such as those that framed Rosenberg’s and Borden’s view, might then be united by something beyond their differences, such as their outsiderishness. Conversely, poets with very similar cultural formations in terms of class, education and social situation, such as Brooke and Sorley, might represent death in battle in ways that were diametrically opposed. Cutting across all such differences there seems to have been the possibility of apprehending something human tout court – perhaps especially in relation to death and the business of dying. First World War texts are no more transparent than any other texts; but they are tied powerfully to a historical and material reality which may at times eclipse socio-cultural differences which we have learnt to be alert to. The differences are there; but let us be aware also of the similarities in experience in the making of memory during a searingly intensive passage of history expressed, in this poetry, through individual consciousnesses. Such variability of attitude to, and expression of, the contingencies of individual experience, which nonetheless remains at some level a common experience, offer a caveat to the constructivist, collectivist framework posited by Halbwachs and his followers. Santanu Das has set a powerful example in his insistence on the importance of both the cultural conditions which shaped literary expression (and its reception at the time and subsequently) and ‘the material conditions which produced the literature’.Footnote 61 We acknowledge gratefully the influence of that example; and we share his central concern with ‘men and women for whom the material conditions of everyday life – the immediate, sensory world – were altered radically by the war and often came to define their subjectivities’.Footnote 62 While taking into account the cultural mediations which existed at the time, and those which have affected us since, we must beware of allowing the material experience that underlies the poetic texts to be over-mediated by cultural accretions. We must tread carefully amongst the complicated interweavings of the individual, the social and the cultural, and always be alert to the way the ‘subjectivities’ of ordinary men and women were responding to what they experienced.

If, within this flexible framework, Brooke and Sorley nonetheless represent an insider’s view, and Rosenberg and Borden, in some sense, an outsider’s view, Wilfred Owen was both insider and outsider. His lack of public school, or even grammar school, education placed him outside the establishment, but his own aspirations were to enter that world as he pursued a classical education through his own efforts.Footnote 63 Owen’s poetic considerations of dying are often troubled or marred by aureate diction; beside Rosenberg’s unflinching eye, Owen’s sometimes seems clouded by romanticism. He also often elides or obscures the moment of death itself. ‘Spring Offensive’ provides a rare description in his work of soldiers being killed, but the moment takes place in a subordinate clause of a sentence which comments ironically on the ways in which those deaths will later be spoken of:

‘Some say’. This reminds us of Rosenberg’s raising the idea of the psyche being seen to leave the body, only to refuse it. Owen tells us that, unlike those who say such things, surviving soldiers ‘speak not … of comrades that went under’. Apart from the soldierly euphemism ‘went under’ (which itself indicates the difficulty of confronting that moment), ‘Spring Offensive’ is written in high rhetorical style, with a vocabulary sometimes Keatsian, sometimes epic, sometimes frankly archaic. In using that mode it tries to catch the moment of high excitement and terror of ‘going over the top’:

This is one way of representing the moment of death in battle which identifies its connections with athletic prowess and heroic combat. But it is far away from the philosophically scrupulous attention of Rosenberg and Borden. Owen does, however, give us an account closer to theirs in spirit, but different again in its insight into the prospect of death, in ‘A Terre’. But he can do this only in a voice other than his own, the voice and vocabulary of a crippled soldier. If this man had his way, he would be speaking from the grave (‘I tried to peg out soldierly’) and he is very nearly dead (‘Less live than specks that in the sun-shafts turn’) but, living, he contemplates the conundrum of what awaits him:

This is like Sorley’s cold reminder, as perceived internally by the ordinary soldier – albeit one who has read Shelley, though only to ironise him:

Shelley’s pantheistic vision is reduced to the soldier’s wry notion of death, where the consolation of oneness with nature has been leached from the language.Footnote 66 Owen signifies that new understanding with his mixture of languages, ‘stunning’ the Shelleyan poetic with the clear-eyed vernacular of the common soldier (just as Rosenberg called up the Wordsworthian consolation only to reject it). All that remains of that unified vision of the world in Owen’s poem is a kind of anticipatory prosopopoeia, whereby the good-as-dead man (he is ‘three-parts shell’, with a bandage that ‘feels like pennies on my eyes’) is given a voice. At times, he speaks of himself as already dead (‘To grain, then, go my fat, to buds my sap’) and finally speaks to the living as if from the grave:

Here, he inhabits his future dead self, but he sees that he will have already become only the grief another person can utter for him – and so recognises that he will have no voice himself. This is a prosopopoeia of the modern universe, recognising that the voice of ‘the dead’ will not be heard.

In ‘Strange Meeting’ Owen takes a further step along this road, dramatising a meeting between two dead soldiers from opposite sides; both dead men are given direct speech, and they speak both to each other and to us. Unlike Brooke’s imagined dead, gambolling in an eternal pastoral idyll, these men are doomed to haunt ‘some profound dull tunnel’, a cross between the underground caverns of the battlefield and a mythic underworld, surrounded by other dead. But in being given a voice, not only are they reanimated, but they can seek redress each from the other. When one of the dead springs up, the ‘I’ of the poem sees where he is:

While the poem recognises the actual hell of the battlefield which has led to these men’s deaths, the foray into the underworld, and the reconciling of the unreconciled, place it firmly in a classical line running back through Dante to Homer and Virgil. Apostrophe and prosopopoeia themselves derive from that classical tradition, one grounded in the epic account of battle, but one too where the dead can be reimagined and re-encountered without entailing the Christian belief in resurrection. Vandiver thus places this encounter in the tradition of katabasis, in which the living visit the dead of the underworld and then return to the land of the living (as exemplified in the Odyssey and the Aeneid). But this is to miss a central tenet of Owen’s poem: both those figured here are dead, and neither will return to the world above. This is a meeting of the equal dead, and the oxymoron of addressing ‘the enemy you killed, my friend’ makes sense only in the imagined state of after-death: Owen’s is an imaginative reanimation of the dead within a powerful poetic tradition, one which enables him to give voice, per impossibile, to what the dead might think if they had the power to reflect on their own fate. But it is not consolatory, except in so far as those who died are at least represented in a continuing poetic tradition. For these poets, addressing the dead, and giving voice to the dead, are part of the powerful tradition of being a poet: to speak to and to speak for. And for a combatant seeing men dying all around him, what is more important than to speak to and for the dead body itself? But Owen, Rosenberg and Borden do this by creating a new framework for that speaking, one that refuses the comfort of a continued aliveness-in-death.

Owen’s vision is not modernist in the way that Rosenberg’s and Borden’s are; his poetry is soaked with traditional forms and language. But he brings the dead to life in a different way, one that is emphatically not Brookeian even though it may use similar modes. ‘Greater Love’, for all its Brooke-like diction, is nonetheless a riposte to Brooke too, recalling the ‘red sweet wine of youth’ in ‘Red lips are not so red / As the stained stones kissed by the English dead’.Footnote 68 It is also an ironic retort to the biblical quotation – ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends’ – often inscribed on war memorials.Footnote 69 For what Owen explores in the poem is the interplay between love for a man when alive (‘red lips’, ‘slender attitude’, ‘dear voice’) and the actuality of death, where the lips can kiss only the ‘stained stones’, the mouth is ‘stopped’, and the body ‘trembles not exquisite’ but is ‘rolling and rolling there / Where God seems not to care’ (echoes of Wordsworth’s ‘Lucy’ again). In what is a daring poem in its open declaration of male beauty, Owen expresses the paradox that drove many like him to return to be with their fellow soldiers even when they began to doubt the point of the war. That ‘greater love’ prevailed, but it entailed the endless loss of the men that inspired it.

Harold Monro had a quite different imaginative landscape, created in part by his constant interchange with, immeasurable encouragement to, and financial and cultural support of, the poets who passed through his seminal Poetry Bookshop (including Owen).Footnote 70 As the war started, many of these were heading to battle, his friend Brooke at that time the most significant amongst them. Monro was too old to fight. But like Owen he recognises the power of the young male body as he contemplates death in war. His poignant sequence ‘Youth in Arms’ traces a brief narrative starting with the uniformed young man preparing for war, and ending with his dead body. The last of the four poems, ‘Carrion’, encapsulates the best qualities of the previous three. The poet imagines the dead young body as a still-alive, to-be-desired, body:

‘Lovely curve’ and its answering ‘watery swerve’ marry the man’s body with the landscape. This is a return to the unified Romantic, as he imagines ‘The crop that will rise from your bones is healthy bread’. We don’t quite believe that determinedly optimistic note though; and there is also something of the Brookeian misting over, as the poet imagines that the earth will not fall on the body

It all seems wishful thinking, but we can forgive the writer given his honesty about the beauty of the dead body in that first stanza. ‘The lovely curve / Of your strong leg’ is what he really grieves for.

Poets left behind to wait, to fret, to write hopeful, cheerful letters to those fighting, to re-meet and then as soon bid goodbye to lovers, friends or sons, then begin the whole business of waiting again – this is what marks the writing of both men and women put at a distance from the place of death, yet always imagining it. Often these poets remain stuck in an old-fashioned rhetoric – as sometimes even combatant poets do – but it is more difficult for the home poets to break out of it as they are stuck, too, in a place of longing and fear for the loved person in battle. There is little or no agency in such a role, unless, like Borden, you have work. Women left to fret or grieve, but also give support, are in a particularly cramped position as poets.

Eleanor Farjeon, circumscribed even more by her loving the married Edward Thomas while (probably) not being his lover, writes the perfect poem of a distanced, delayed understanding of the loved one’s death. ‘Easter Monday’ catches the particular agony inflicted by the time delay in getting news of the loss of a loved one.Footnote 72 She has written and sent three letters to Thomas, only to discover later that he was dead all that time; the structure of the poem holds this dramatic irony within its form. Taking a line from his own letter to her in the first half of the poem – ‘“It was such a lovely morning”’ – she repeats it in the second half to reflect her own experience of that Easter Monday, when she was still ignorant of his death. The multiplying ironies are reflected in the simplicity of the last line: ‘There are three letters that you will not get.’ It is heartbreaking that, even now, she cannot stop herself from continuing to address him in the present. Farjeon wrote her poem in the knowledge that Thomas was dead; Vera Brittain inscribed her poem ‘To My Brother’ on the flyleaf of a poetry anthology, The Muse in Arms, which she sent to her brother Edward on the Italian Front, thinking him still alive.Footnote 73 But Edward was killed four days after she sent it, and before he could read her poem of tribute. Reading it now, we can’t escape that irony; our hindsight embeds it in the poem.

Many of the poems written by those outside the battle are necessarily valedictory, and here we come back to memorialisation. The remembrance uttered by combatant poets, speaking from the thick of battle, even if a poem was written on leave or behind the lines, is imbued with the here and now of death. But, with some exceptions such as Gurney with his named comrades, they mourn a whole group of people even when it is one death that they fix on. The poems of those left to grieve at a distance are characteristically personal, and they address that person lost. This is different from the general address to the dead we discussed earlier, and different too from the gaze of either Rosenberg or Borden on the impersonal dead body. When Brittain wrote to her brother, she did not know he would be dead when her poem arrived; but Farjeon writes to Edward Thomas, whom she knows to be dead, in exactly the same intimate tones. Margaret Postgate Cole’s ‘Afterwards’ is likewise addressed to ‘my beloved’.Footnote 74 These poems escape the charge of a dishonest bringing to life of the dead. These women poets know full well the men they address are dead; these are elegies on an ordinary scale, with the scale of grief reined in. Postgate Cole touchingly invokes the future she and her lover might have imagined for themselves:

They might, too, have returned to ‘the larches up in Sheer’, and this she does in the ‘afterwards’ landscape of the poem, but now alone:

Nature has been laid waste to feed the mechanised demands of battle; the larches are corpses as her dead lover is a corpse:

The Wordsworthian/Shelleyan pact between man and nature has been felled by this war; not only are the larches dead, the pit-props are dead, and the man is dead:

From the depth of personal grief and loss, Postgate Cole raises the same existential questions that Borden does, that Rosenberg does, that Sorley and Owen and Monro do, and that so many First World War poets do. The non-combatant poets joined the combatant poets in the task of remembrance and memorialisation – keeping the dead in the imagination of the living.

If Brooke was the earliest manifestation of ‘cultural memory’ about the First World War, Owen’s poetry has become an alternative accredited ‘cultural memory’ of a different kind. The Assmanns’s theory of the role of reception in the formation of memory makes these two competing strands possible. Owen’s work certainly became the late-twentieth-century popular site for our understanding of First World War deaths, mourning and remembrance – and to an extent remains so. But a feature of this centenary moment, at which we reconsider all the issues outlined in this chapter, is the far greater diversity of representation now available to us. Poems and poets of all ilks have been revived and reverberate in the public memory. Among the most notable of these is Ivor Gurney, who has emerged as a major voice only in the last twenty years. Gurney addresses like no other both the particulars of death in battle and the far larger sense of desperate loss as it turns into existential terror.

In ‘To His Love’, Gurney creates the poetic correlative of what Roland Barthes calls the Irremediable. Barthes, analysing, only days after his mother’s death, his own intense and lacerating feelings of loss asks, ‘In the sentence “She’s no longer suffering”, to what, to whom does “she” refer? What does that present tense mean?’Footnote 75 Barthes notes the contradiction in our tendency to think or speak of the dead as still alive, yet claim consolation for them in their not being alive, as though they can experience the lack of suffering. In fact, of course, they experience nothing. That they experience nothing is itself a consolation, but one that can’t be known by them precisely because they experience nothing. And for those of us left behind, it is not a consolation either because the horror is precisely that they can experience nothing.Footnote 76 That is the existential void, the ‘Irremediable’ of death.Footnote 77 Gurney, in ‘To His Love’, expresses the void, as well as reflecting on memory itself. The poem is at heart the commemoration of a particular man. Gurney had been in the front line since June 1916; in August of that year he heard that his much loved friend from Gloucestershire days, Will Harvey, was missing, presumed dead. Gurney’s deep sense of loss at that time is recorded in several letters. The received view of ‘To His Love’ is that it was finished after Gurney learned that Harvey was not in fact dead, but was in a prisoner of war camp. But the poem doesn’t read like that. Rather it has the feel of an ungoverned grief and despair, a cry of loss. ‘He’s gone’ – in that small phrase Gurney leaps straight into the modern voice.Footnote 78 The colloquial elision of ‘He’s’ is inexorably in the present, while the dependent ‘gone’ is ineluctably in the past. The voice is colloquial, yet all the pain of the poem is contracted into that brief clause. Everything that comes after is predicated on the loss it expresses: ‘all our plans are useless indeed’.

The tenses of the poem play backward and forward so that we are not sure where we are in time. ‘We’ll walk no more on Cotswold’ conjures up a future and cancels it at the same time, just as the present of ‘he’s’ is cancelled by the past participle ‘gone’. Yet the sheep remain steadily in the historic present, feeding and taking no heed. The same interplay of tenses can be seen in the second stanza:

We move though ‘was’ (past), ‘Is’ (present), ‘not’ (cancelling the present ‘is’), ‘Knew’ (past again) and ‘Driving’ (continuous present). The subject of the poem is still alive in memory, yet unimaginably dead; the play of tenses against each other tries to make sense of that.

Here we have a poet, in the midst of fighting, hearing, as he thought, of the death of a man he loved. But the poem goes beyond those specifics, catching the existential vertigo that comes with understanding that a man alive one minute can be dead the next, cancelling his future, and making a mockery of his past. At the Front, sudden death was everywhere; but the death of this one man brings the poet up against the problem of making some meaning of it. If the first three stanzas of the poem with their grazing sheep, Severn river and violets call up the comfort of pastoral, in the final stanza we see the flash of horror which cannot be concealed by any amount of flowers, and which links back to the modernity of the opening, ‘He’s gone’:

‘Red wet’ in a First World War context can only mean one thing; but then Gurney uses the actual word ‘Thing’ which, in its very lack of specificity, adds to the line’s power after the particularity of place and flower names. It is these which are now made silly by what is unimaginable in any specific terms. The loved ‘body that was so quick’ has been reduced to a ‘thing’, its quickness spilled out in the ‘red wet’, and that memory is now caught forever, making the earlier innocent memories impossible. Being the one thing to forget, it is forever remembered. Tim Kendall suggests that ‘Gurney attempts to observe the rites of official remembrance while withstanding a panicked reaction to the wounded corpse’.Footnote 79 But Gurney is signalling a lacuna rather than a contradiction – an existential panic. He allows no comfort into the poem; the lure of pastoral redemption is floated before us only to be refused. Rather he wants to reflect that moment of utter hopelessness when the past is made barren and the future hopeless, that moment of laceration, the irremediable. The sudden horror of the last two lines ends the poem on a void, ejecting the reader into the real world beyond the poem and to a fresh understanding of her own mortality. It is a long poetic journey from Brooke’s red sweet wine to Gurney’s red wet thing.

The grief we feel for soldiers killed in war is so sharp because their lives have been brutally cut short. The grief for those killed in the First World War is sharper still because so many were amateur soldiers – carpenters, teachers, bakers, mechanics – who had no clear idea of the realities ahead. When Owen reminds us of the ‘Carnage incomparable, and human squander / Rucked too thick for these men’s extrication’, he is lamenting a double tragedy, the scale of death itself, and the inability of men’s minds to comprehend it. The poets we consider in this book did somehow manage the act of imaginative extrication from ‘carnage incomparable, and human squander’, bringing to us – at the distance of a hundred years – some understanding and engagement with a moment in history whose horrors sometimes seem to defeat representation. More than that, they bring us face to face with our human, mortal selves and the fact of our own extinction. Out of their own grief for the loss of comrades, from the feared loss of their own lives, and from the grief of those at home who suffered the loss of loved ones, came poems, each one an attempt to move beyond the howl of despair, to give it shape and meaning. These poets look hard at death – though their eyes are sometimes cloaked – and they bring us missives from that Front, in the form of poems. It is the intention of this book to look as closely as the poets do.