1.1 A Short History of the Computer, IC, and Connector

The advance in computer performance has been nothing short of spectacular. In just 60 years, within the lifetime of the average human being, computer performance has increased by 100,000-fold, while power consumption has decreased by a similar factor of 100,000, physical dimensions by a factor of 1,000,000, and price by a factor of 1,000. However, advance in integrated circuit (IC) technology, which has been fueling this explosive growth, is now facing severe challenges that may bring the growth to a stop. Before we ponder where we are going to go from here, it is worth looking back to see how we have come to this point.

1.1.1 History of the Computer

The 2014 British film The Imitation Game portrays the development of a computer by Alan Turing to break the secret code behind Nazi Germany’s Enigma communications machine. Turing is considered one of the fathers of the modern-day computer due to his development of the Turing machine that provides the model for a general-purpose computer. Nevertheless, his code-breaking computer completed in 1938 had the sole purpose of breaking the Enigma machine.

Indeed, early computers were specific-purpose computers where the types of problems they could solve were determined by how their components were wired together. In other words, it was a wired-logic computer architecture. Therefore, what we think of as programming today was done by rewiring the components, if at all possible. This hardwired architecture has two severe challenges.

(1) Challenge of scale: the size of problems that can be solved is limited by the scale of the network of components.

(2) Challenge of wiring: as the system scale goes up, the wiring complexity grows exponentially and beyond what can be handled manually.

These two challenges were overcome with two groundbreaking inventions: the von Neumann computer with stored programs and the IC. In a von Neumann computer, the data to be processed and a list of commands in the form of a program to control how the hardware processes the data are stored in memory. The computer operates by retrieving input data and the program from memory. Then in each operational cycle, a different command is executed resulting in a different set of operations. Different types of problems can thus be solved by feeding different programs with different sets of commands to the same piece of hardware with the same wiring. A von Neumann computer is therefore a general-purpose computer. More complex problems can be solved with more complex programs, overcoming the challenge of scale.

Meanwhile, invention of the IC, chronicled in the next section, has enabled a large number of circuit elements to be integrated and interconnected all on a single chip. Using photolithography, all interconnections can be made in parallel as part of the chip-making process, overcoming the challenge of wiring. The IC enables integration and parallelization of simplified and progressively downsized computing resources, driving rapid advance in chip computational performance.

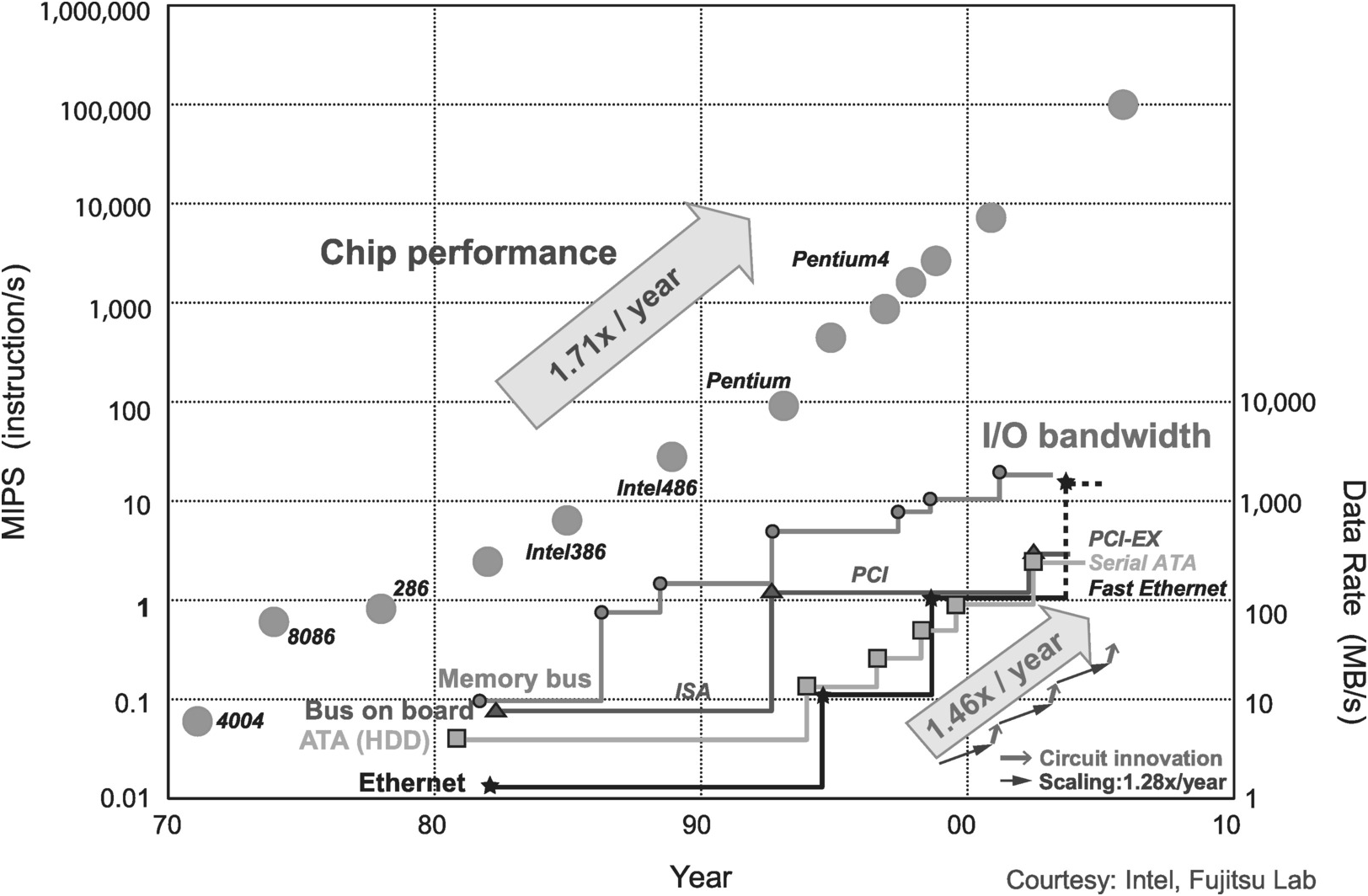

However, as computational performance continues to rise, a new challenge in interconnecting chips is emerging. In particular, economics requires that the processing unit and the bulk of the memory it uses be implemented on separate chips, and connecting these two chips has become challenging as the amount and required speed of data flow in the chip interface grows, resulting in what is known as the von Neumann bottleneck in the interface, limiting overall system computational performance. Consequently, continuous advance in computer performance requires increasing both chip and interface performance.

On the other hand, the rapid advance in artificial intelligence technology based on neural network and deep learning is renewing interest in the wired-logic computer architecture, where the function performed is implemented through hardwiring like the neural network in the human brain. As a result, history has come full circle and the challenges of scale and wiring are once again pushed to the forefront, which necessitates innovative solutions to drive the next phase of computing technology advancement.

1.1.2 The Four Seasons of IC Development

1.1.2.1 The “Big Bang”: Invention of the IC

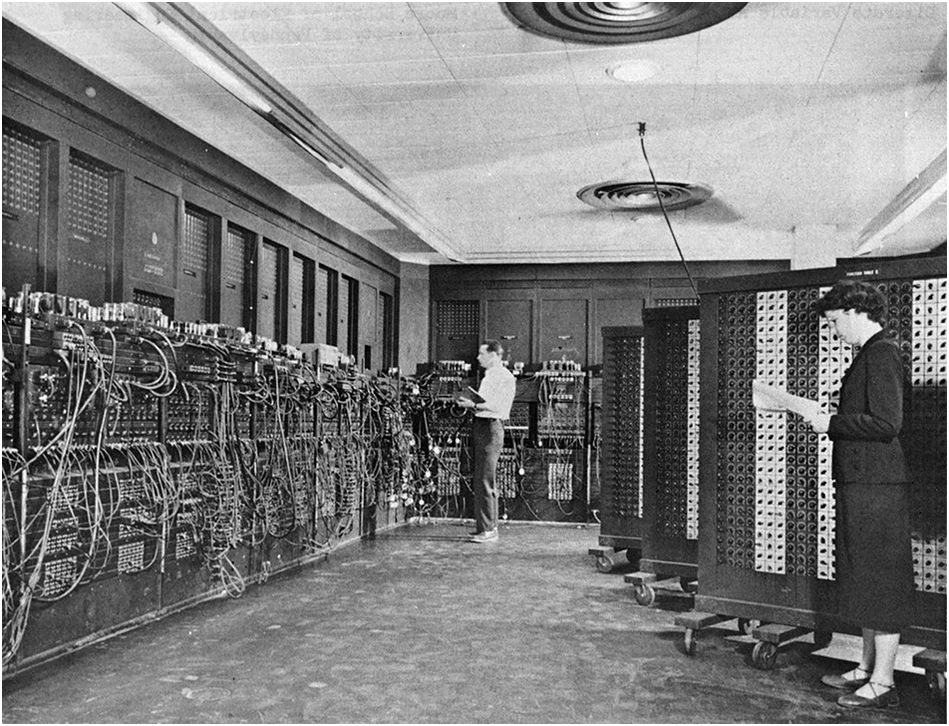

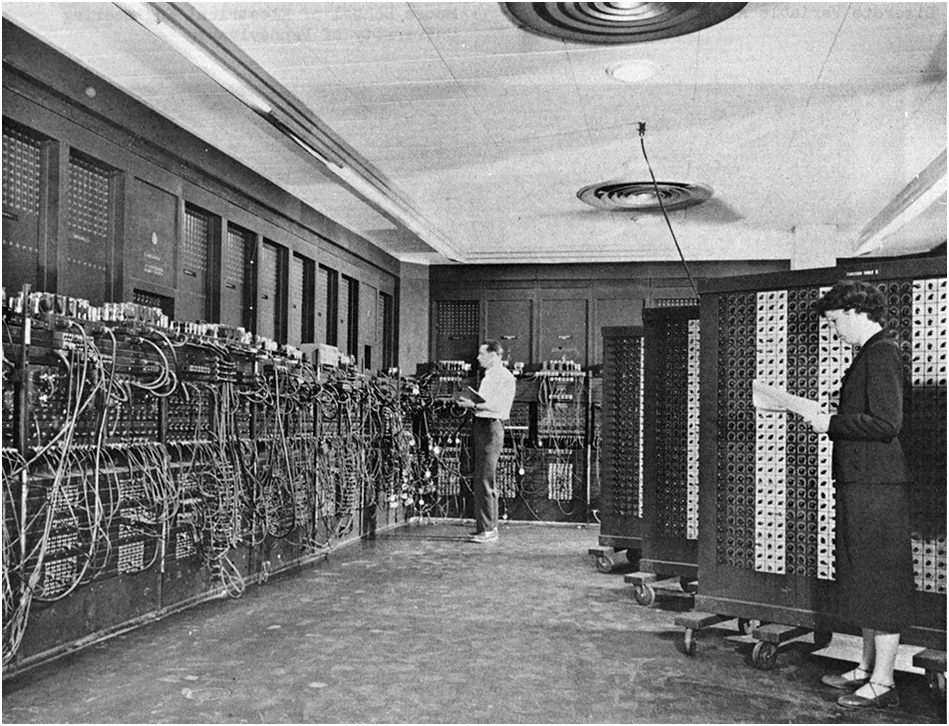

One of the first general-purpose computers built was ENIAC (Figure 1.1), developed in the United States in 1945 and introduced in 1946. It was a gigantic piece of machine built with 100,000 components and weighed 27 tons. It consumed so much power – 150 kW – rumor has it that streetlights in the neighborhood dimmed when it was being operated. It had about 5,000,000 solder connections made by hand. Its heat-generating vacuum tubes had such poor reliability that a few of them broke and the system went down every day.

Figure 1.1 Programming ENIAC. Photo by US Army, public domain

The transistor, a more reliable replacement of the vacuum tube, was invented by William Shockley et al. in 1948, based on the groundwork laid by Bell Labs in the prior year. With much less heat generation and higher reliability, it enabled construction of much larger-scale systems. However, the increasing scale of computer systems led to the exponential growth in the number of interconnections between components and hence wiring complexity. It was such a challenging problem that it became known as the tyranny of numbers. The winning solution that emerged, among various proposed, was the IC.

The IC was invented by Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce in 1958–1959. At the time, Texas Instruments (TI) was working on the Micro-Module solution to the problem of the tyranny of numbers that enabled circuit components to be densely packed on a printed circuit board (PCB). Kilby, despite being a TI engineer, developed an alternate solution – the groundbreaking concept of a monolithic IC where all circuit elements are integrated on a single piece (mono) of semiconductor substrate (lithic). In the following year, Robert Noyce would develop the silicon implementation of the IC.

1.1.2.2 Spring: Explosive Growth through Scaling

Around the same time in December 1959, American physicist Richard Feynman delivered a lecture entitled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” where he discussed scientific manipulation at the atomic level. This could be considered the start of nanotechnology research, a field that fueled the advance in IC technology and hence its explosive growth.

In 1965, Gordon Moore of Fairchild Semiconductor (and later of Intel Corporation) published a paper entitled “Cramming More Components into Integrated Circuits,” where he described the potential of the IC with its exponentially growing integration density. He observed that the number of components in an IC had doubled approximately every year, and speculated that such a growth rate would continue. This speculation would later become known as Moore’s law and set the collective target for the advance of the semiconductor industry.

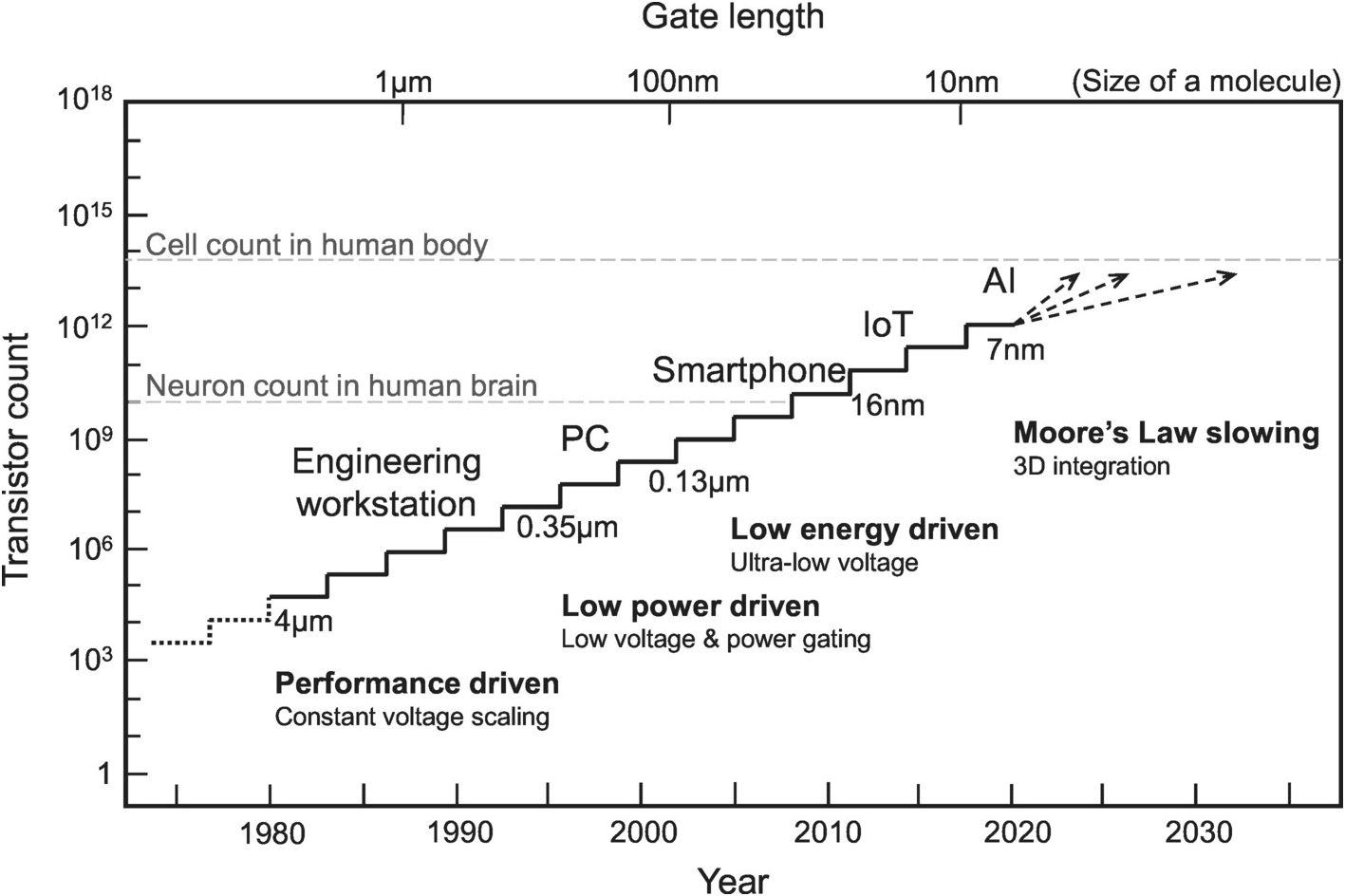

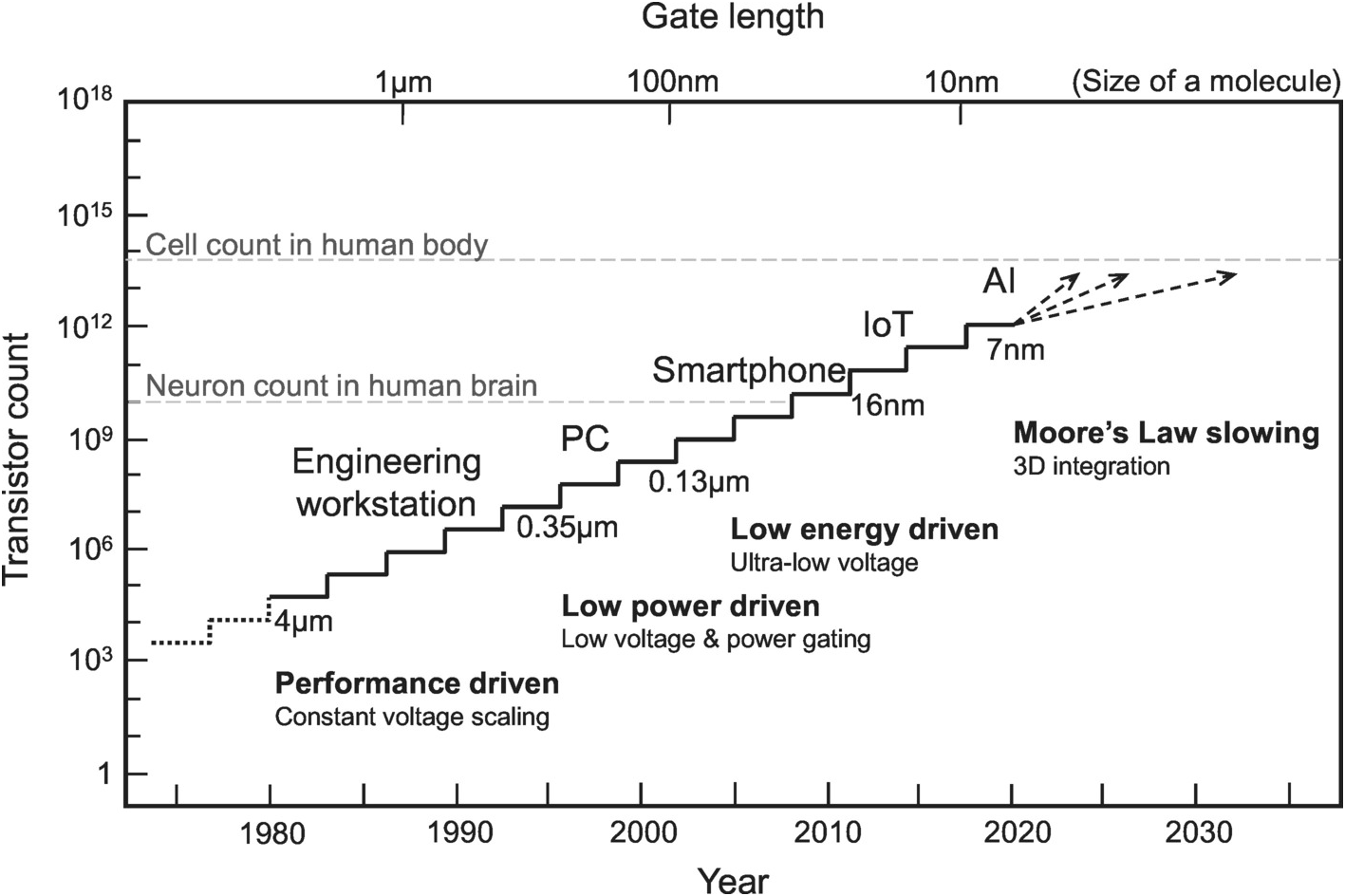

Figure 1.2 illustrates how the dominant computing device has evolved as transistor count increases following Moore’s law, and the changing driving force behind the evolution. From around 1980 to 1995, transistor channel length shrank from 4 to 0.35 µm. Meanwhile, the number of transistors that can be integrated on an IC increased from 100,000 to 100,000,000. As a result of this increased chip-level integration, the computer evolved from being an engineering workstation to a personal computer (PC), and its adoption spread from being one per group to one per person. As the trend continued, the smartphone replaced the PC as the dominant computing device, the Internet of Things (IoT) became ubiquitous, and artificial intelligence (AI) computing finally entered into the mainstream.

Figure 1.2 Evolution of the integrated circuit [Reference Kuroda1].

In this manner, scaling fueled the explosive growth of the IC. Unfortunately, there was a trade-off with an undesirable consequence that lurked in the background as computational performance rose. Eventually, around 1995, it reared its ugly head in the form of a wall that threatened to stop further scaling.

1.1.2.3 Summer: The Power Wall

Around 1995, process scaling ran into a power wall. Scaling resulted in a continuous increase in power consumption, to the point that the IC released so much heat as to degrade its reliability, bringing further scaling to a halt. As an illustration, from 1980 to 1995, in 15 years, power consumption of an IC increased 1,000-fold. On a per-unit-area basis, an IC generated as much heat as an electric cooktop – you can fry an egg by powering an array of these chips under the fry pan! How did that happen?

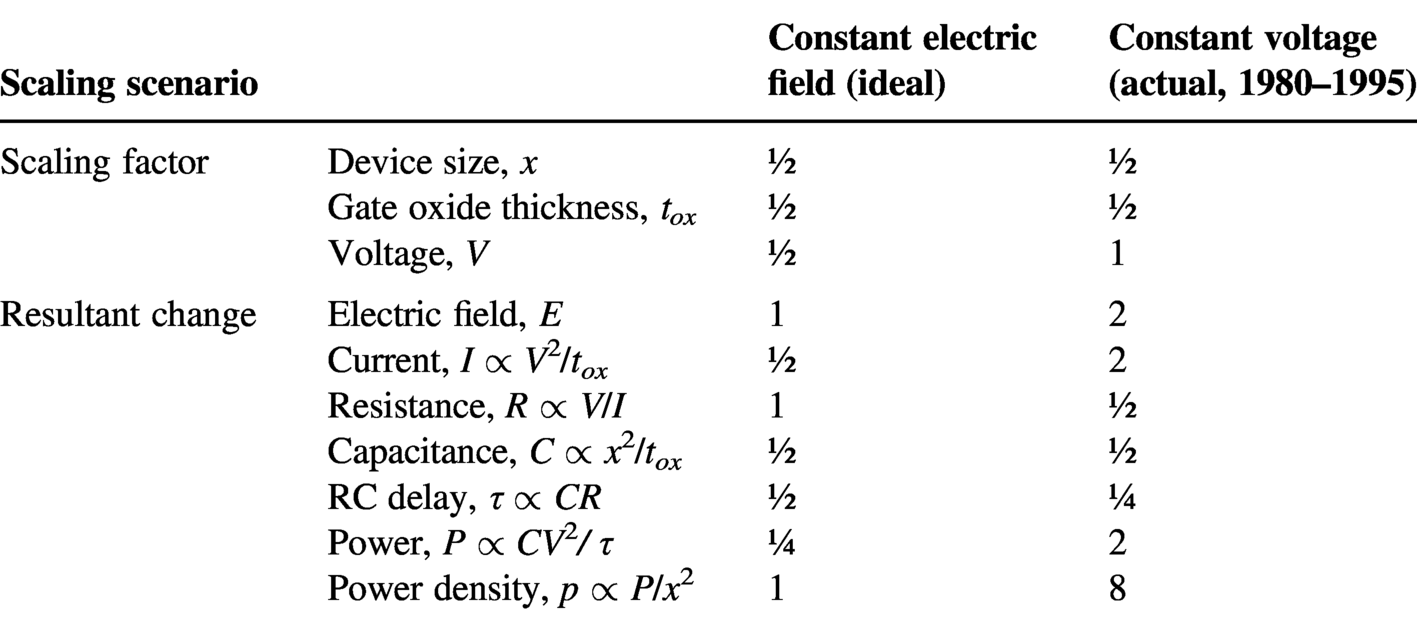

In 1974, Robert Dennard, inventor of dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), formulated with his colleagues the scaling theory that describes an ideal scaling scenario where the electric field within the semiconductor device is kept constant. If you scale the supply voltage and physical dimensions of the device by the same factor, the electric field, which is a function of the ratio of voltage to distance, will remain constant. As a result, transistors whose operation is driven by manipulation of the electric field will perform the same way after scaling. Under this scaling scenario, power density would remain unchanged as well. Therefore, for the same chip size, power remains the same after scaling, and hence no heat generation or dissipation problems should arise (see the column “Constant electric field” in Table 1.1). Meanwhile, as the device gets smaller, more devices can be integrated in the same area, leading to lower manufacturing costs. Furthermore, the circuit resistor–capacitor (RC) time constant is reduced, resulting in higher operating speed. It is indeed a beautiful scenario that, if realized, would have no undesirable consequences.

Table 1.1. Transistor scaling scenarios

| Scaling scenario | Constant electric field (ideal) | Constant voltage (actual, 1980–1995) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaling factor | Device size, x | ½ | ½ |

| Gate oxide thickness, tox | ½ | ½ | |

| Voltage, V | ½ | 1 | |

| Resultant change | Electric field, E | 1 | 2 |

| Current, I | ½ | 2 | |

| Resistance, R | 1 | ½ | |

| Capacitance, C | ½ | ½ | |

| RC delay, τ | ½ | ¼ | |

| Power, P | ¼ | 2 | |

| Power density, p | 1 | 8 | |

The reality was that scaling was implemented with no reduction in supply voltage. In other words, it was not a constant electric field but rather constant voltage scaling. In this case, the circuit ran even faster as RC delay was further reduced, IC computational performance went up further, and more chips were sold bringing in higher revenues. The flip side was a large increase in power (see the “Constant voltage” column in Table 1.1). Given that IC power consumption was small to begin with, its increase had initially only a secondary effect. Nevertheless, continuous scaling resulted in rapid increase in power consumption. Before long, it hit a painful limit. This power wall was therefore the result of an unintended side effect of nonideal scaling.

The power consumption increase with scaling was the result of the laws of physics. It is therefore not an easy problem to solve. Faced with the power wall, various schemes were devised to handle the extra power that came with performance increase. For instance, in power gating, circuit operations are diligently monitored. Whenever a circuit is not in use, its power is cut off. In another scheme, supply voltage is lowered whenever high circuit performance is not required. Such power-saving actions may sound obvious given that we practice similar power conservation in our daily life. But with hundreds of millions of transistors on a large-scale IC, uncovering waste is no simple task. For any waste we can find and eliminate, that much power can be exchanged for increased performance. In other words, “no gain in power efficiency, no gain in IC performance.” This is a trade-off IC development has continued to face to this day.

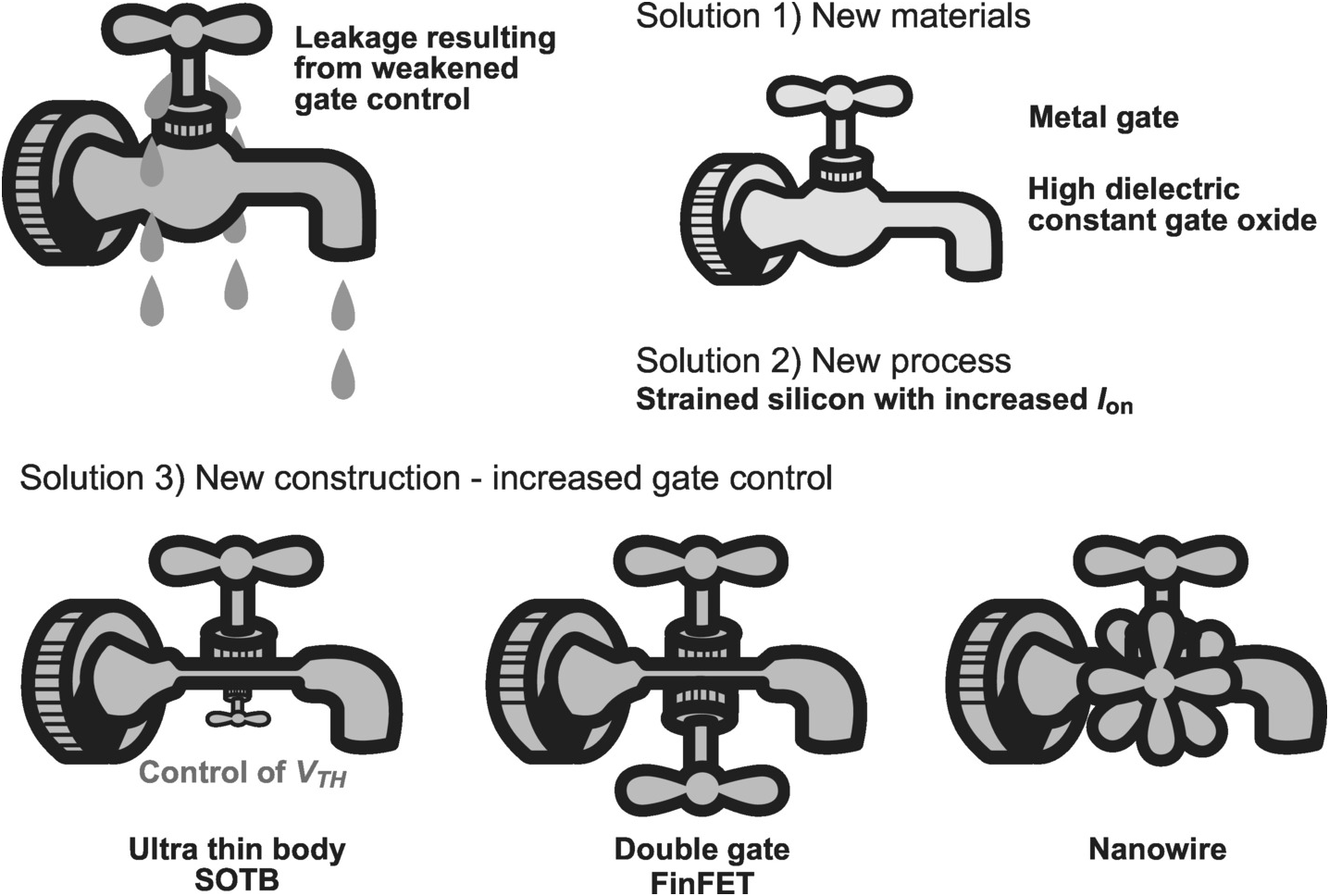

1.1.2.4 Fall: The Leakage Wall

Around 2005, scaling hit yet another wall – the leakage wall. Unlike the power wall, the leakage wall was not a result of the progression of scaling; rather, it was the consequence of scaling reaching its limits. As transistor channel length was scaled down to 100 nm, gate oxide thickness was reduced to 1.2 nm, about the thickness of 4 molecules. If the oxide layer were thinned further, it would be subject to quantum effects under which tunneling current would flow. But without proportional reduction in gate oxide thickness, further transistor scaling would weaken ability of the gate to properly turn off the channel, resulting in leakage current. It is analogous to a faucet not properly turned off, allowing water to drip.

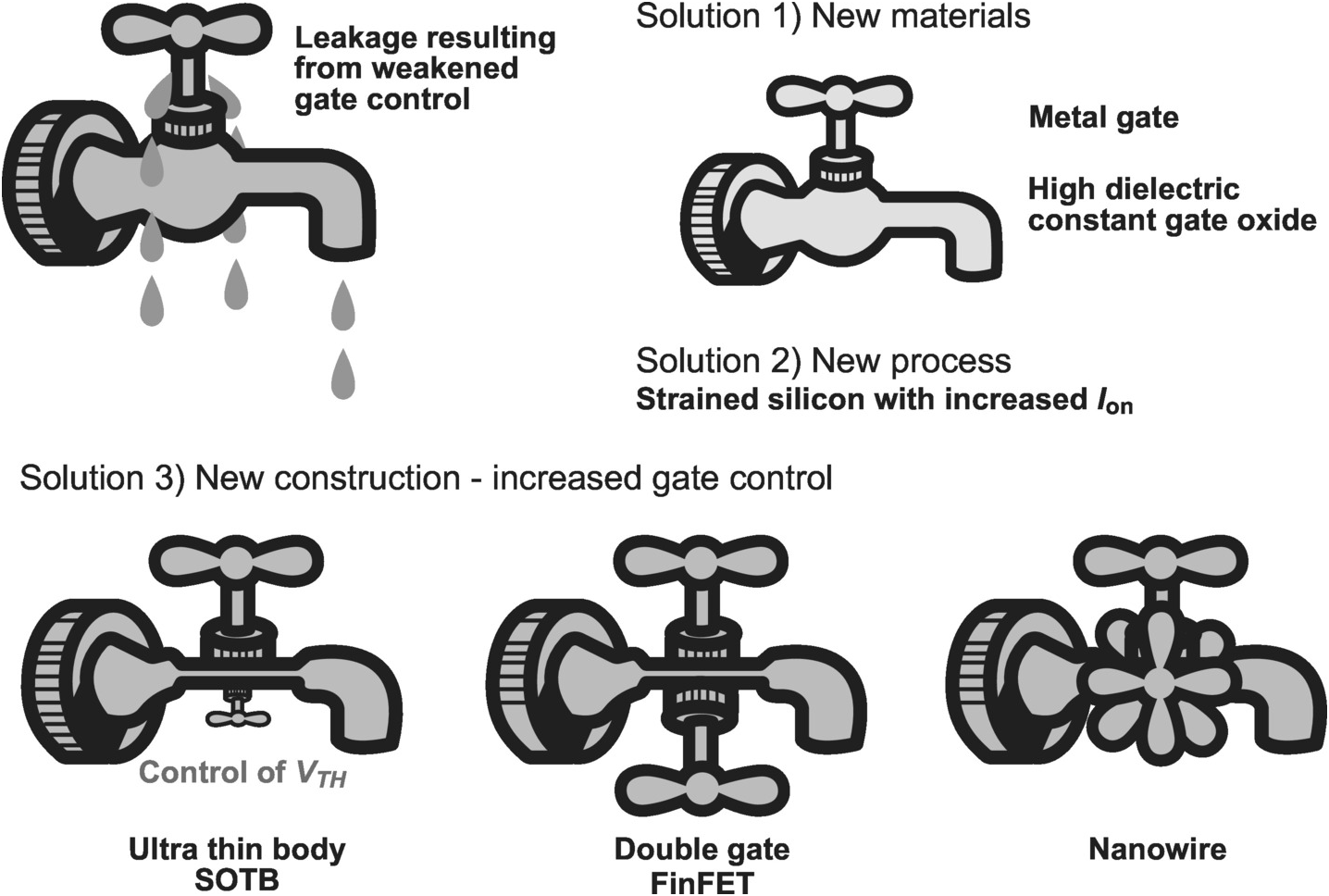

The options for fixing the “leaky faucet” include changing materials, modifying the manufacturing process, or adjusting how the device is constructed, as shown in Figure 1.3. For example, dielectric materials with higher dielectric constant were introduced to increase electric field strength without reducing thickness. In parallel, development of a manufacturing process was started to introduce distortions in the silicon structure (strained silicon) to stretch the silicon atoms to boost mobility and hence current when the transistor is on, without increasing leakage when the transistor is off. Furthermore, transistor gate construction was transformed from being planar to three-dimensional, such as in a fin field-effect transistor (FinFET), in order to strengthen gate control of the channel.

Figure 1.3 Low leakage device technologies [Reference Kuroda3].

Nevertheless, all these are measures to provide temporary relief only; there are no good ways to counter quantum effects that result from the laws of physics.

1.1.2.5 Winter: The End of Scaling?

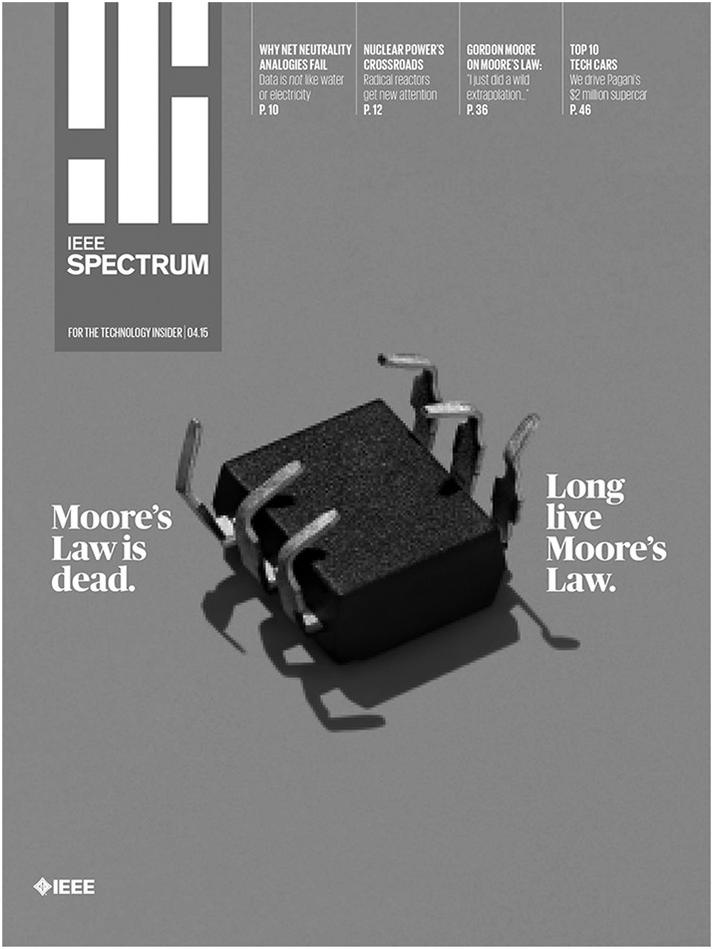

The cover of the April 2015 issue of IEEE Spectrum (Figure 1.4) depicts a flipped-over computer chip in the shape of a belly-up, dead bug, with the competing headlines of “Moore’s Law is dead” vs. “Long live Moore’s Law.” “Is Moore’s Law dead?” is the billion-dollar question faced by the IC industry: Is scaling, that has propelled the industry in the last half of a century, coming to an end? Has IC development entered its winter season?

Figure 1.4 IEEE Spectrum cover, April 2015.

Over the prior 40 years, the manufacturing cost per transistor had dropped by a factor of 4 million. However, as channel length shrank below 28 nm, this unit cost started to rise. The economic benefits from scaling finally started to disappear. IC manufacturing has become a privilege that only a few companies with deep pockets can afford due to the enormous investment required. Even the costs for making an R&D test chip have risen from only several hundred thousand dollars to several million dollars. Faced with such adverse economic reality, once thriving IC research in both the academia and industry is gradually losing momentum.

1.1.2.6 The Second Spring

Nonetheless, innovation is not slowing; it is only taking a different form. Innovation in the semiconductor industry over the last 60 years has been mainly driven by Moore’s law in process scaling that has fueled an exponential proliferation in IC quantity and made it ubiquitous in our society. With the slowing or even ending of scaling, innovation is shifting to enhancing quality, in terms of how we apply IC technology in various innovative ways to enrich our life. The excitement in dramatically improving the price performance of an IC has been replaced by excitement in research and development of novel applications, including automated driving, artificial intelligence, big data, and IoT. Each of these areas is exploring different innovative ways to realize the potential provided by the performance achieved in scaling – IC’s first act. After experiencing the excitement of achieving a 100 million-fold improvement in the price performance of a computer, we are witnessing the opening of the curtain on IC’s second act, where advance in IC technology enters its second spring to deliver enrichment across various facets of our life.

1.1.3 History of the Connector

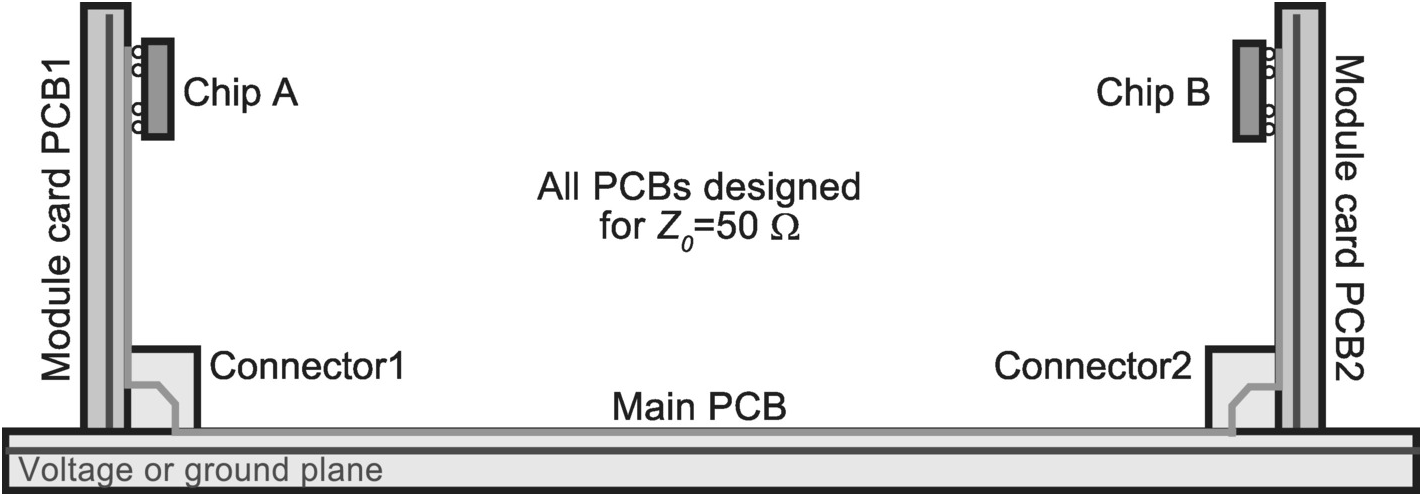

Regardless of where we are on the transistor count growth curve, there is a limit on how many functions can be packed into an IC. Similarly, there is a limit on how big a package, a module, and a printed circuit board can practically and economically be manufactured. Furthermore, not all desired functions can be performed by transistors. For instance, many functions require the use of sensors, actuators, and other input/output devices. On the other hand, economics oftentimes requires sourcing components made with different processes by different suppliers, and economy of scale favors the use of standardized parts. As a result, a computing system is generally constructed by connecting separate parts together, which necessitates not only interchip integration but also module integration using connectors.

In contrast to the IC, the history of the connector over the last 70 years has been characterized more by advances in quality instead of quantity, by how connections are made instead of exponential increase in the number of connections. The major technological innovations during this time include the following:

Crimped termination

Insulation displacement contact

Wire wrapping

Press-fit

Optical connector

In particular, the crimped termination represented a major paradigm shift since it gave rise to a solderless connection.

1.1.3.1 The Solderless Connection

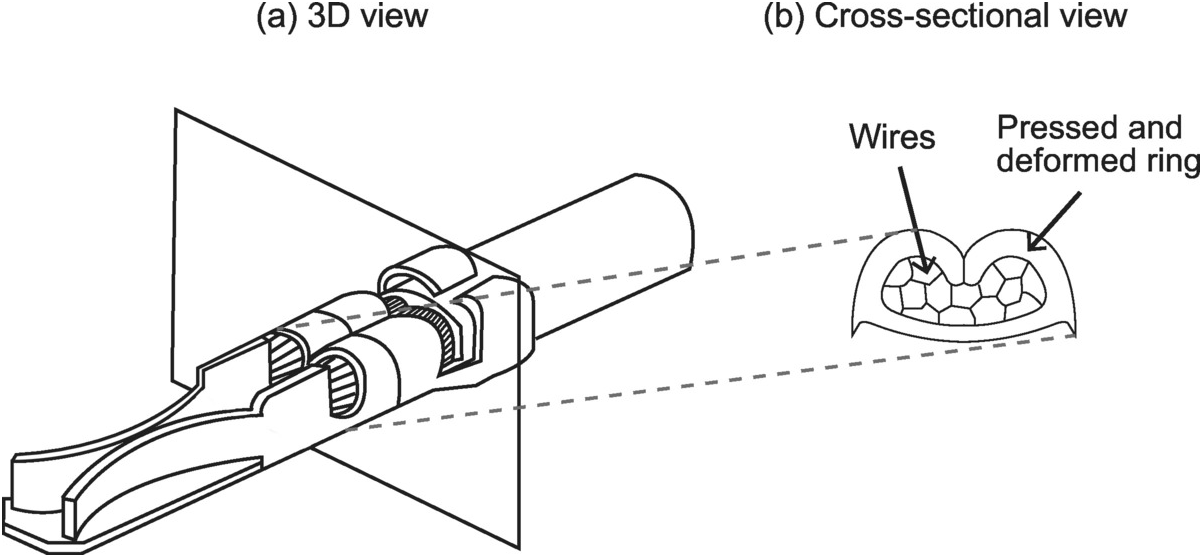

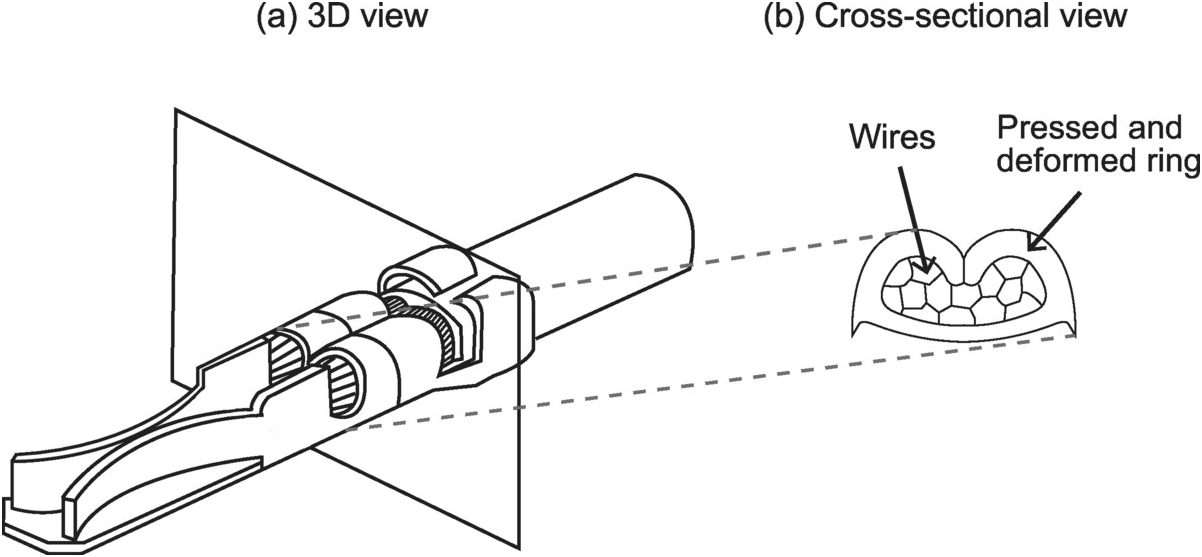

The solderless electrical connection was invented by American engineer Uncas A. Whitaker in 1941 [4]. Known as a crimped termination, it is a connection formed by inserting open wires on one end into a small metal tube with a ring on the other end, and pressing the ring against the wires using a specialized tool (Figure 1.5). Compared to a rigid, soldered connection, this revolutionary technology delivers a much faster way to make and break a connection in a smaller space. Furthermore, it offers higher reliability in the face of shock and vibration. Consequently, when the United States entered World War II, the technology was widely adopted in military applications since it maintained electrical connections even under harsh operating conditions. Furthermore, it significantly increased the speed of equipment repair, including that of fighter jets on aircraft carriers, which was a critical advantage in wartime. After the war ended, the application of crimped termination was extended to commercial applications, especially those that required operation in harsh environment, including automotive and appliances, such as power tools for the homebuilding boom that ensued after the war.

The solderless electrical connection opened up the possibility for an easily breakable connection and hence the idea of an electronic connector, which enabled modularization and flexible selection of different combinations of modules in building a large-scale electronic system, resulting in flexibility, expandability, and scalability. System assembly can be done by users in the field, and it is easy to replace or upgrade part of the system. Consequently, it represented an advance that is parallel to the IC in solving the connection problem of large-scale systems.

1.1.3.2 Recent Challenges for the Connector

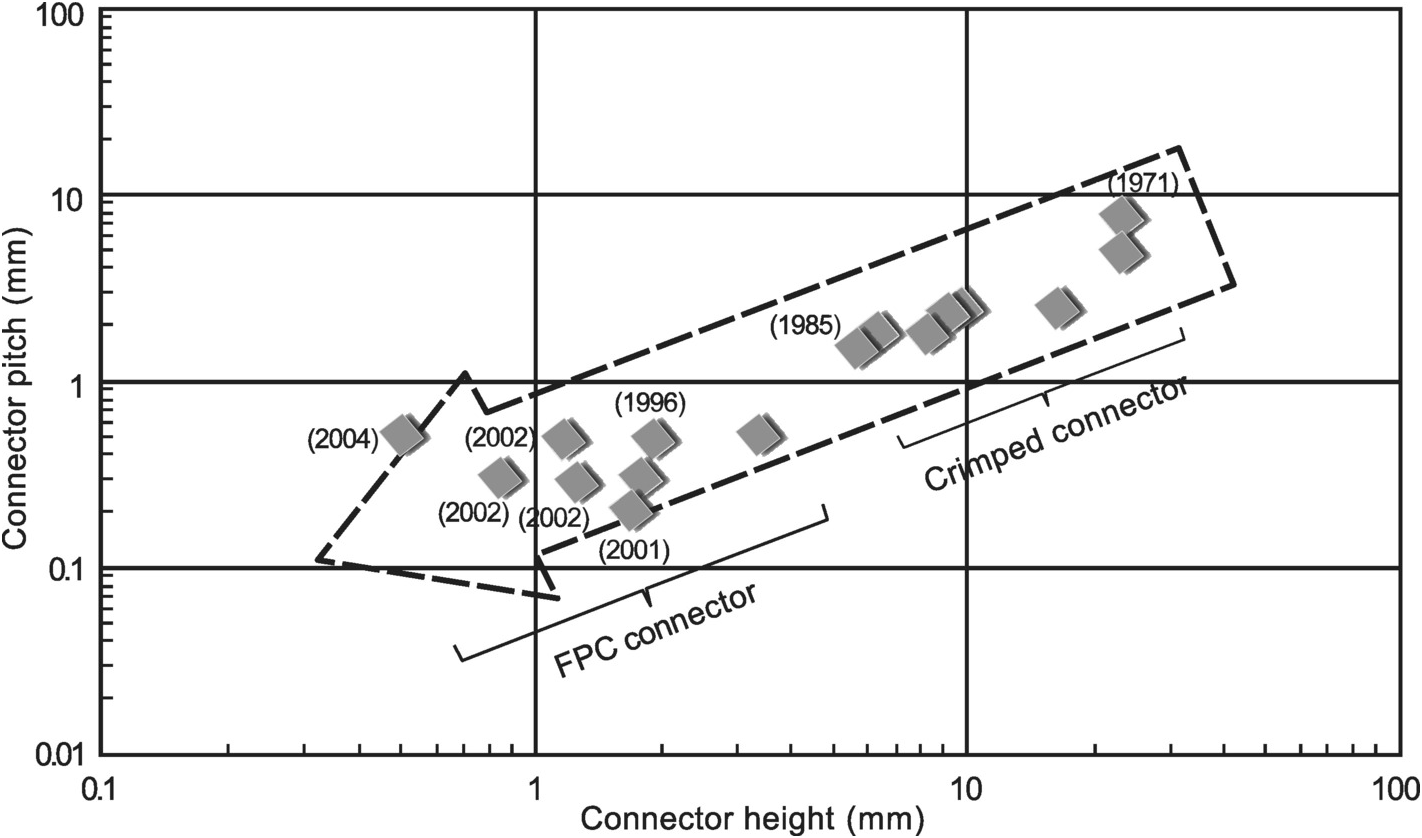

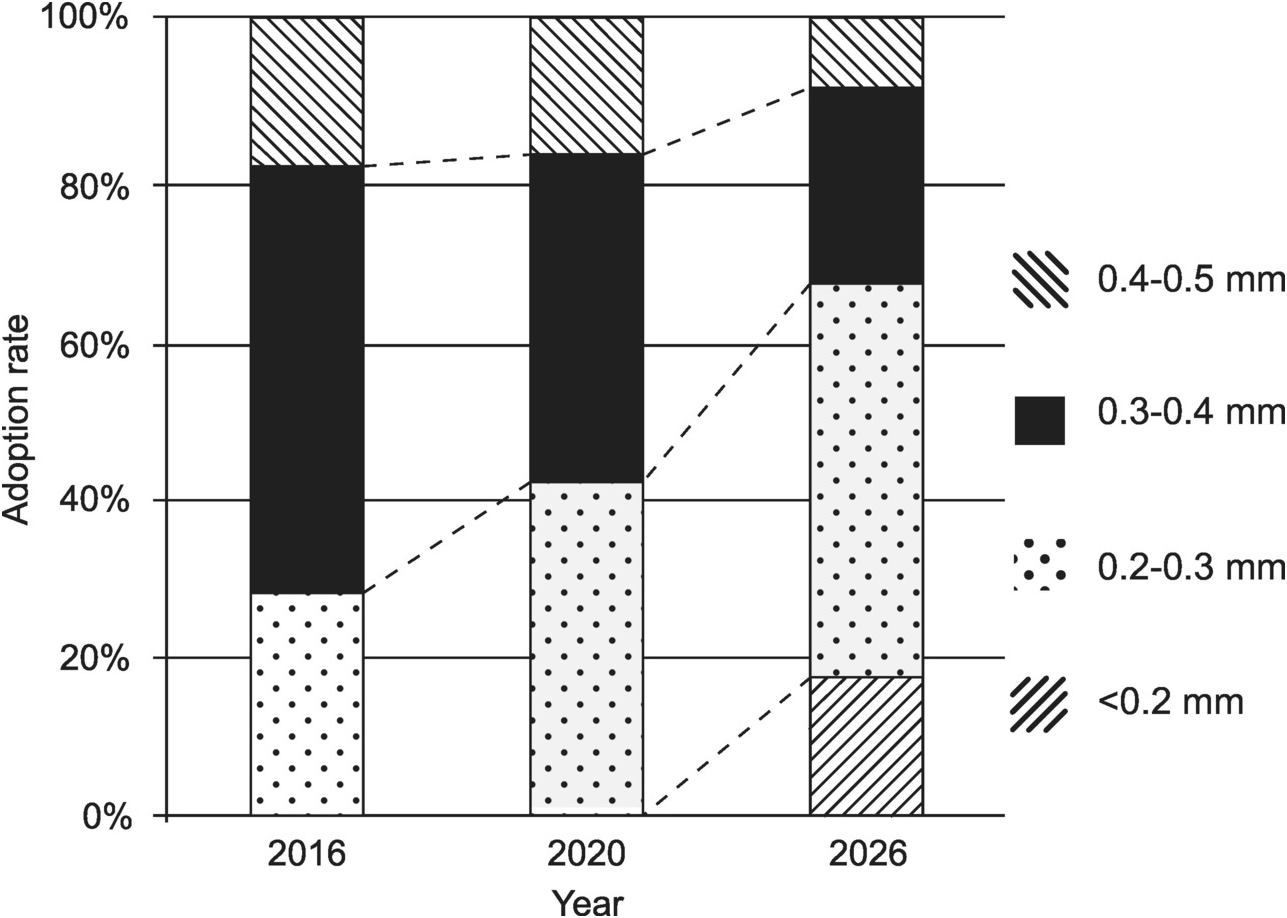

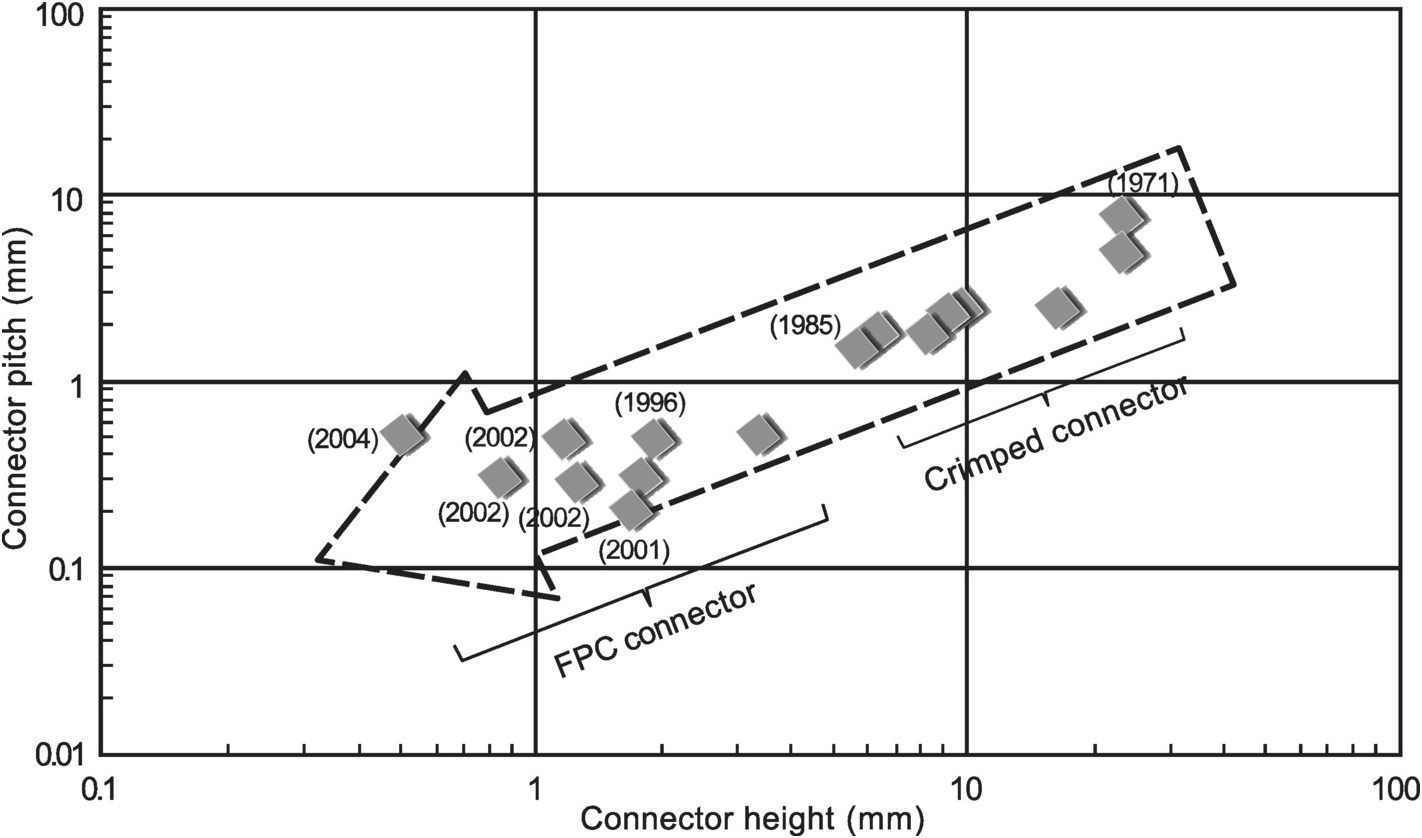

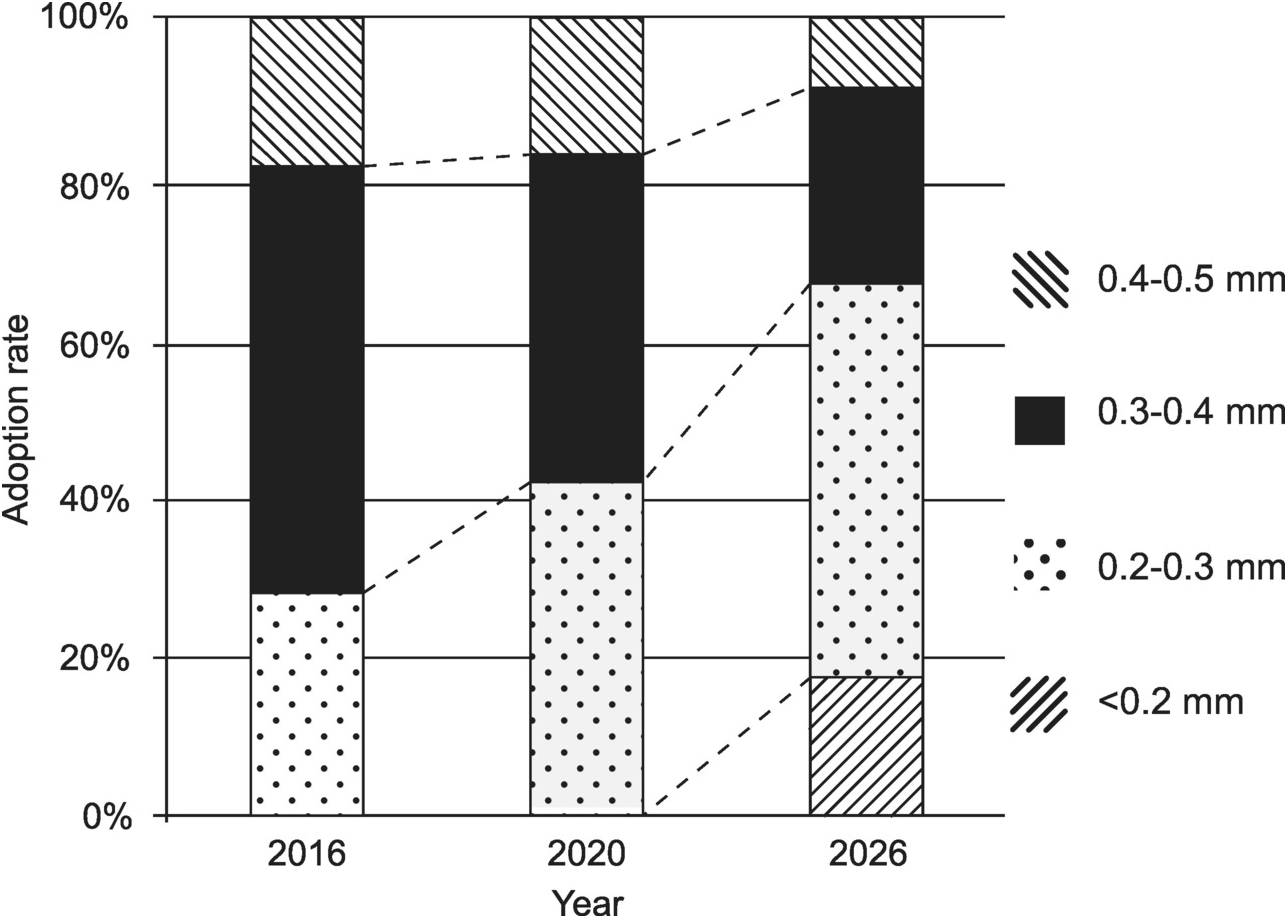

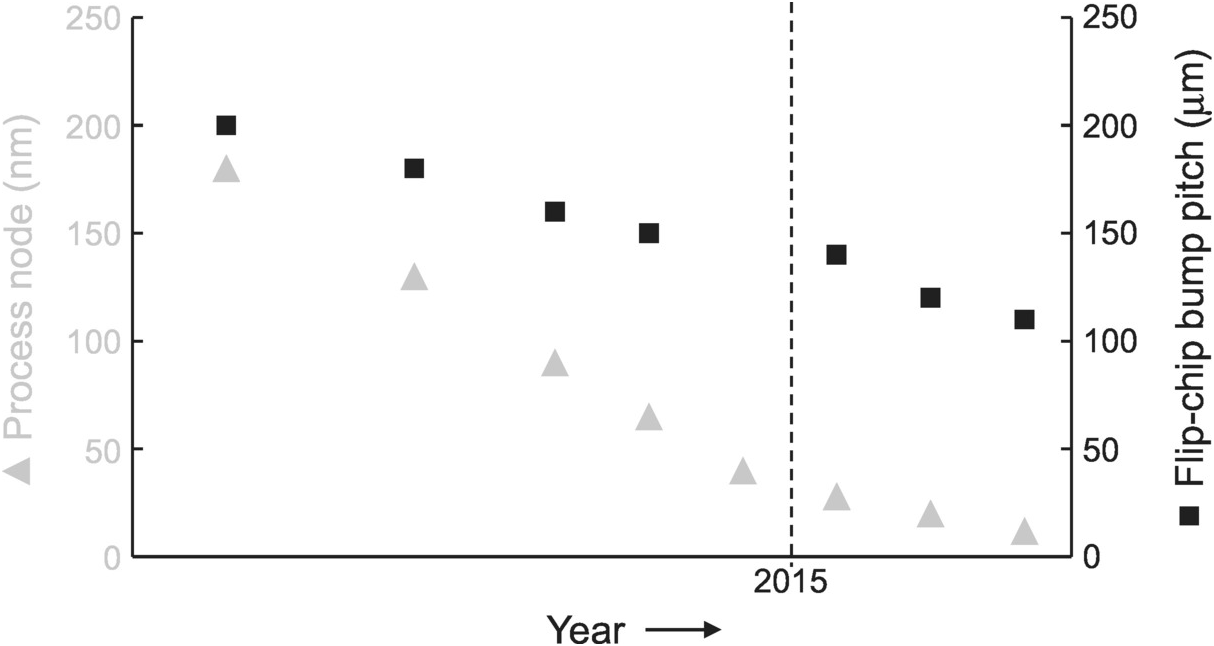

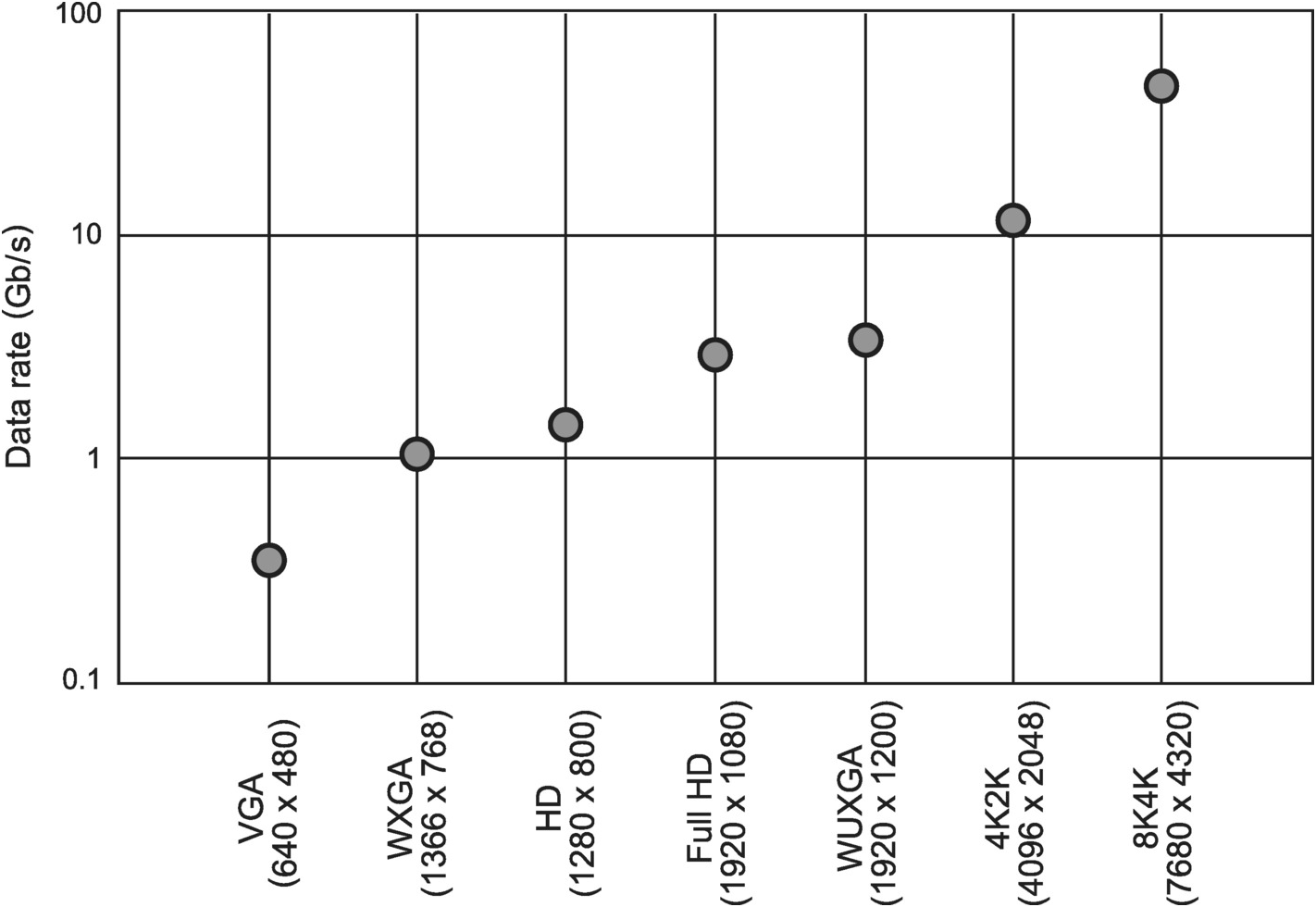

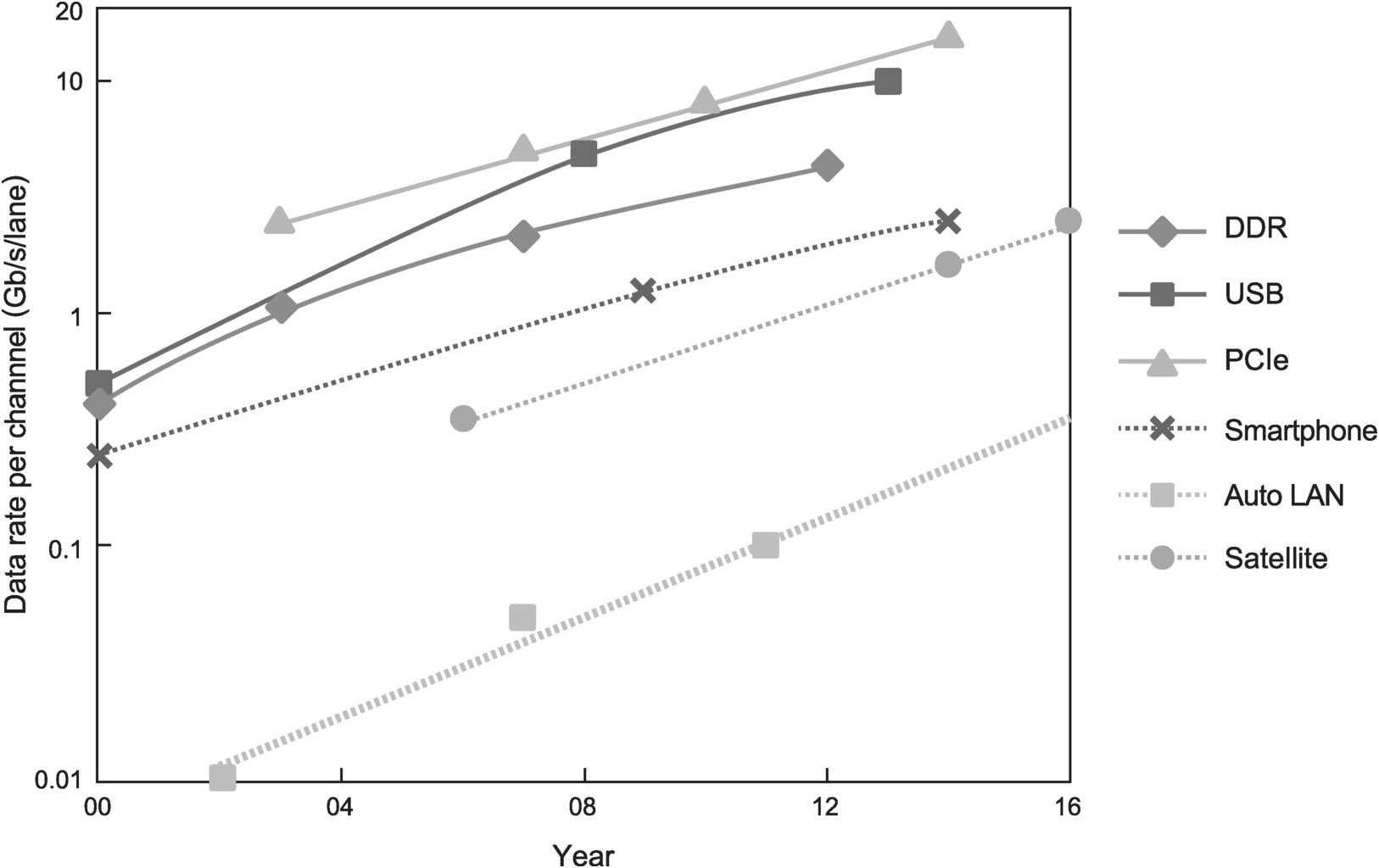

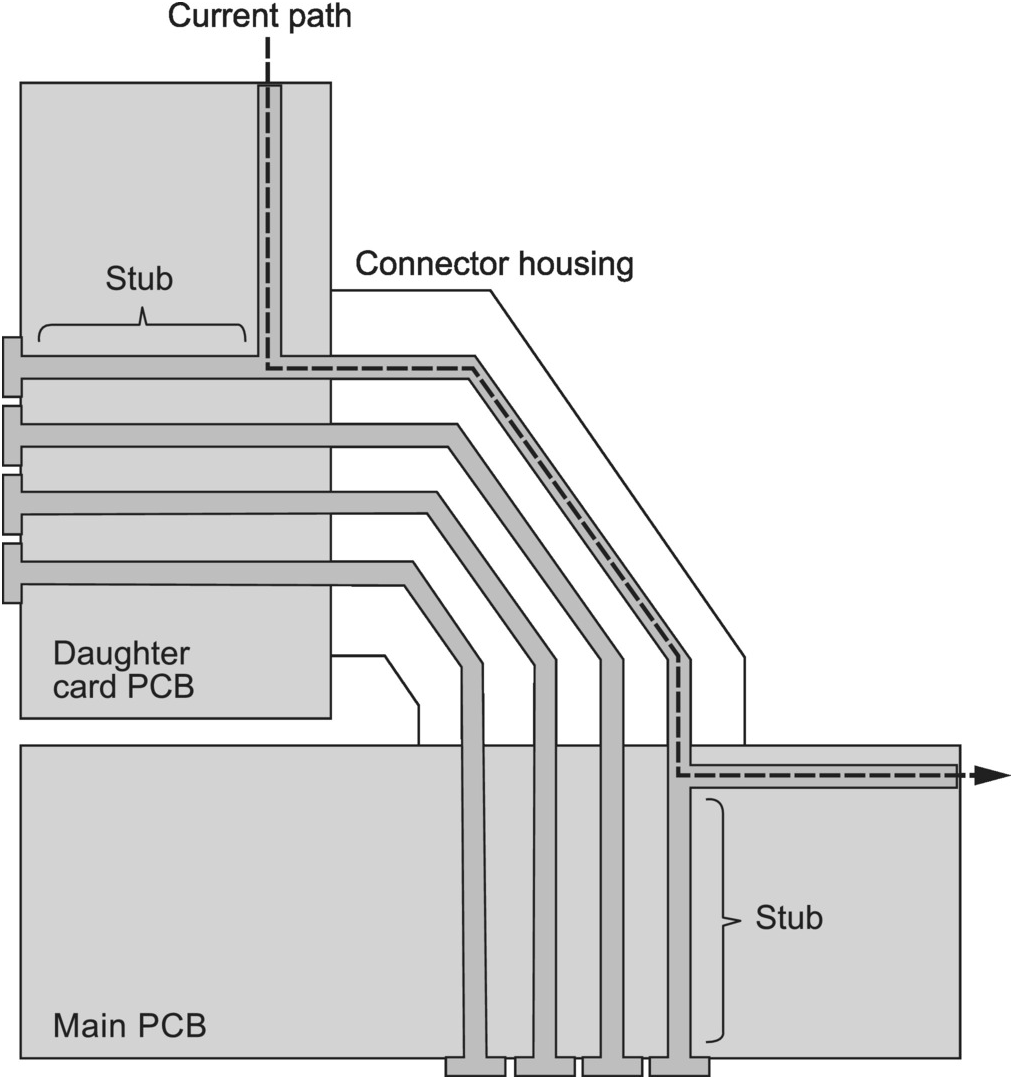

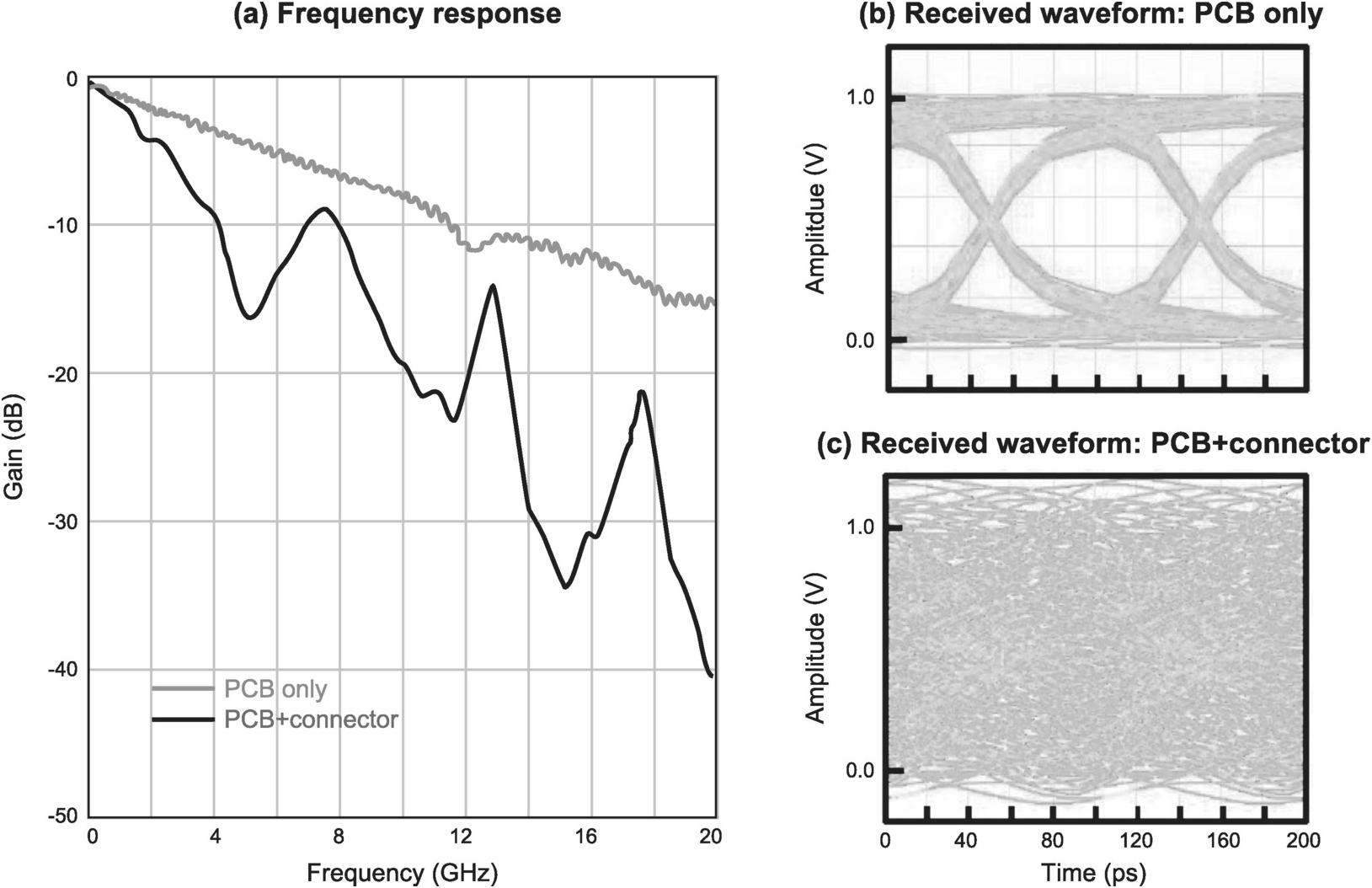

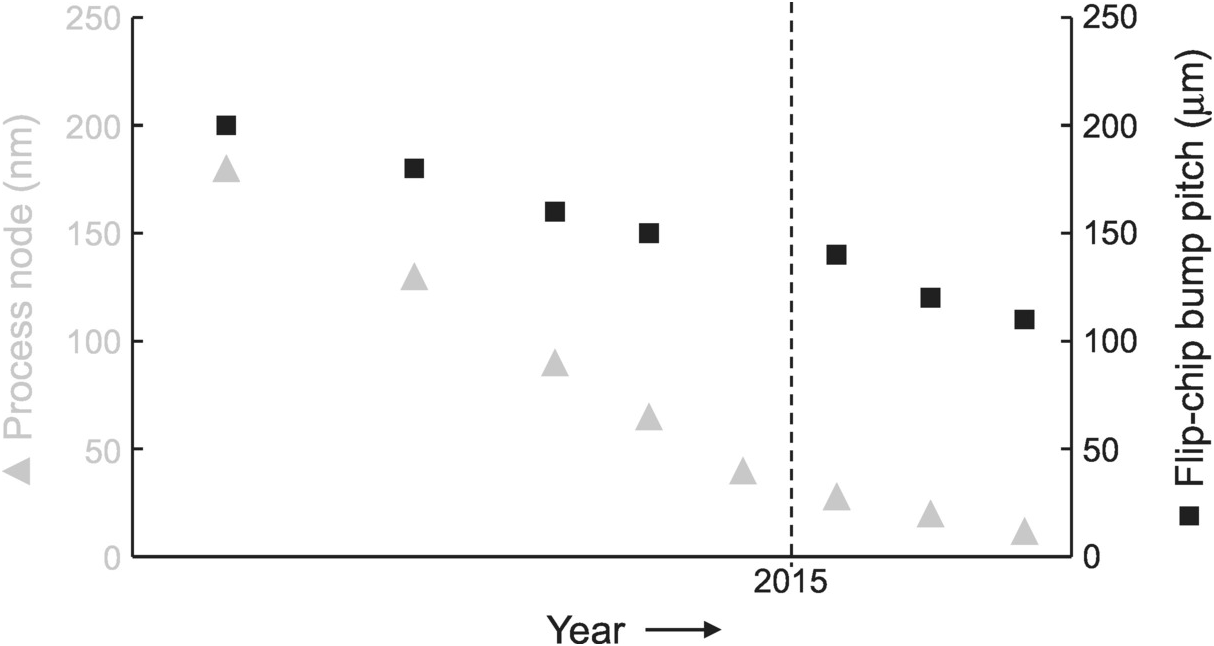

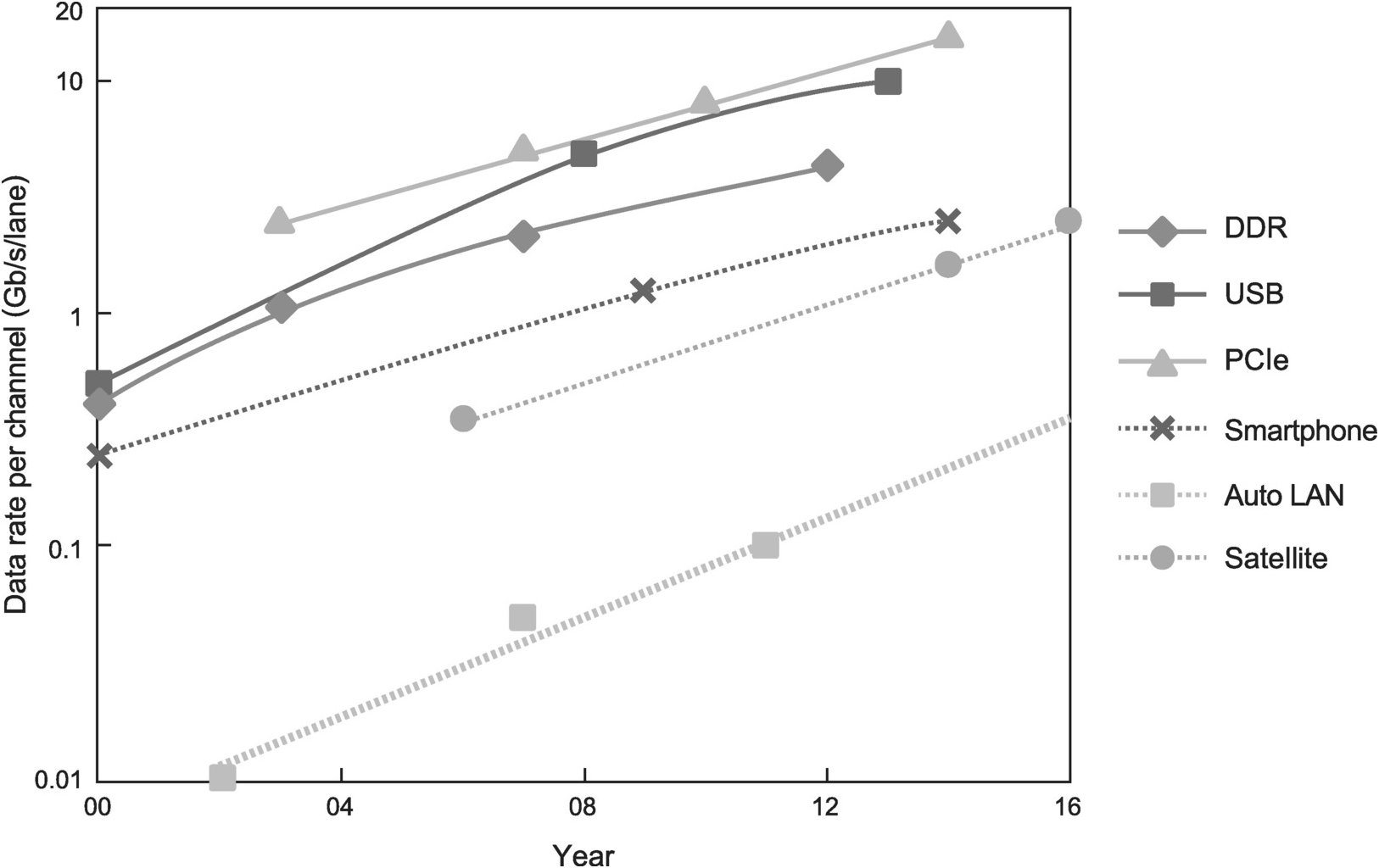

The introduction of the iPhone in 2007 set in motion the rapid shift from the PC to the smartphone as the dominant form of electronic and computing system. Even the first-generation iPhone represented an order-of-magnitude shrink in form factor compared to the PC. The subsequent exponential growth in functionality and performance of the smartphone with continuous, albeit incremental, shrink in form factor in the last decade only added to the pressure to continuously shrink both the footprint and height of the components within. Nevertheless, scaling of connector dimensions is not keeping pace with that of the IC. This is illustrated by the historic trend in the scaling of flexible printed circuit (FPC) connector pitch. Because of its flexibility, low profile, and small dimensions, FPC and its connector are commonly used in mobile devices. From 1996 to 2004, FPC connector pitch scaled by roughly 0.4× and its height by roughly 0.25× in eight years, corresponding to average scaling of 0.89× and 0.84× per year, respectively (Figure 1.6). By contrast, around the same time from 1995 to 2003, Intel process migrated from 350 to 90 nm, scaling gate length from 350 to 50 nm, or 0.14× in eight years [6]. More recently, based on the roadmap published by the Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association (JEITA), mainstream pitch of FPC-to-PCB connectors used in small form-factor devices is projected to shift from 0.3–0.4 mm in 2016 to 0.2–0.3 mm in 2026 (Figure 1.7), which translates to total scaling of 0.714× over 10 years, and a modest average scaling of 0.967× per year. This represents a rapid deceleration in the scaling of FPC connector pitch.

The challenges in scaling connector dimensions are not surprising given the mechanical processes required in manufacturing connectors. Furthermore, it is difficult to significantly scale the dimensions of the connector housing that is needed to provide mechanical stability to ensure a reliable connection, especially when it is subject to shock and vibration, such as in an automotive or space application. This is on top of the challenge in maintaining signal integrity as the data rates of signals passing through connectors rise rapidly. The time is ripe for another revolutionary connector technology to enable a leap in miniaturization and performance of electronic systems.

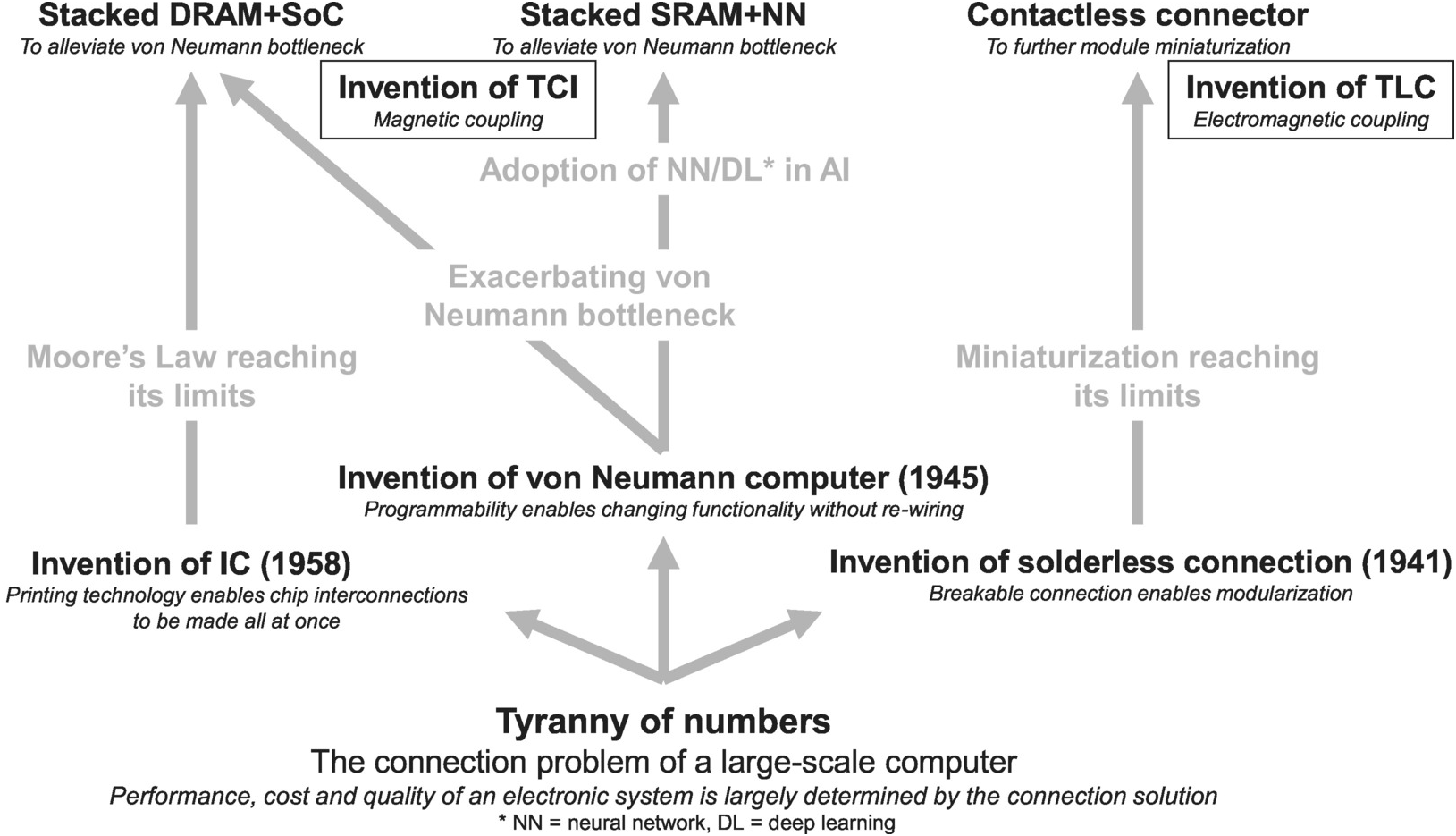

1.1.4 Closing Thoughts

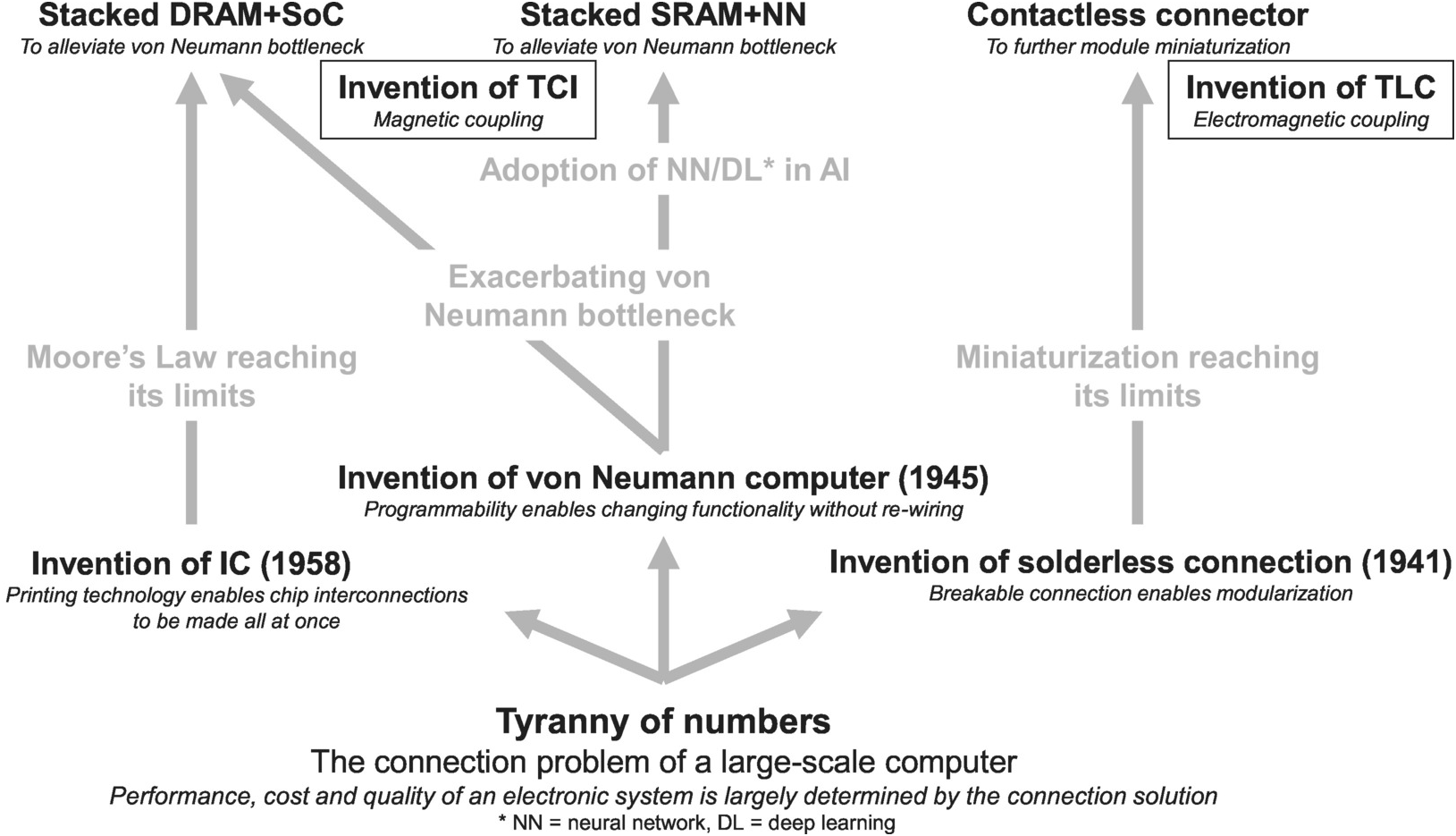

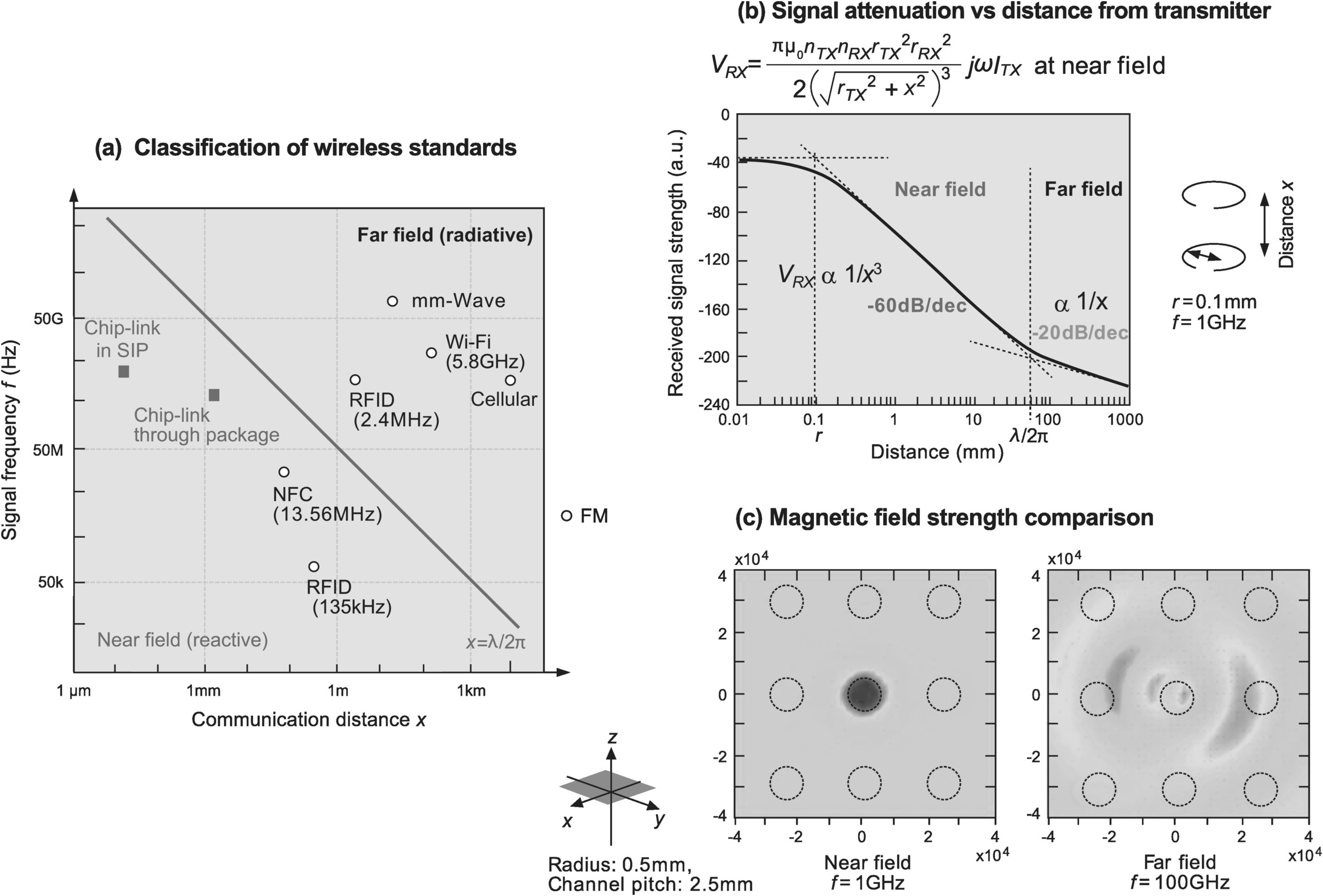

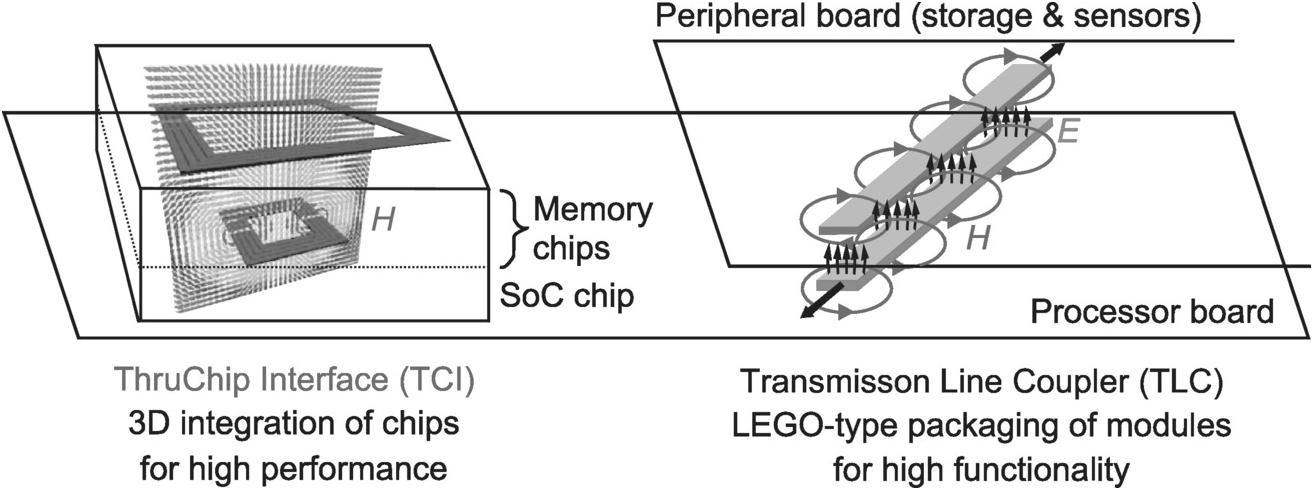

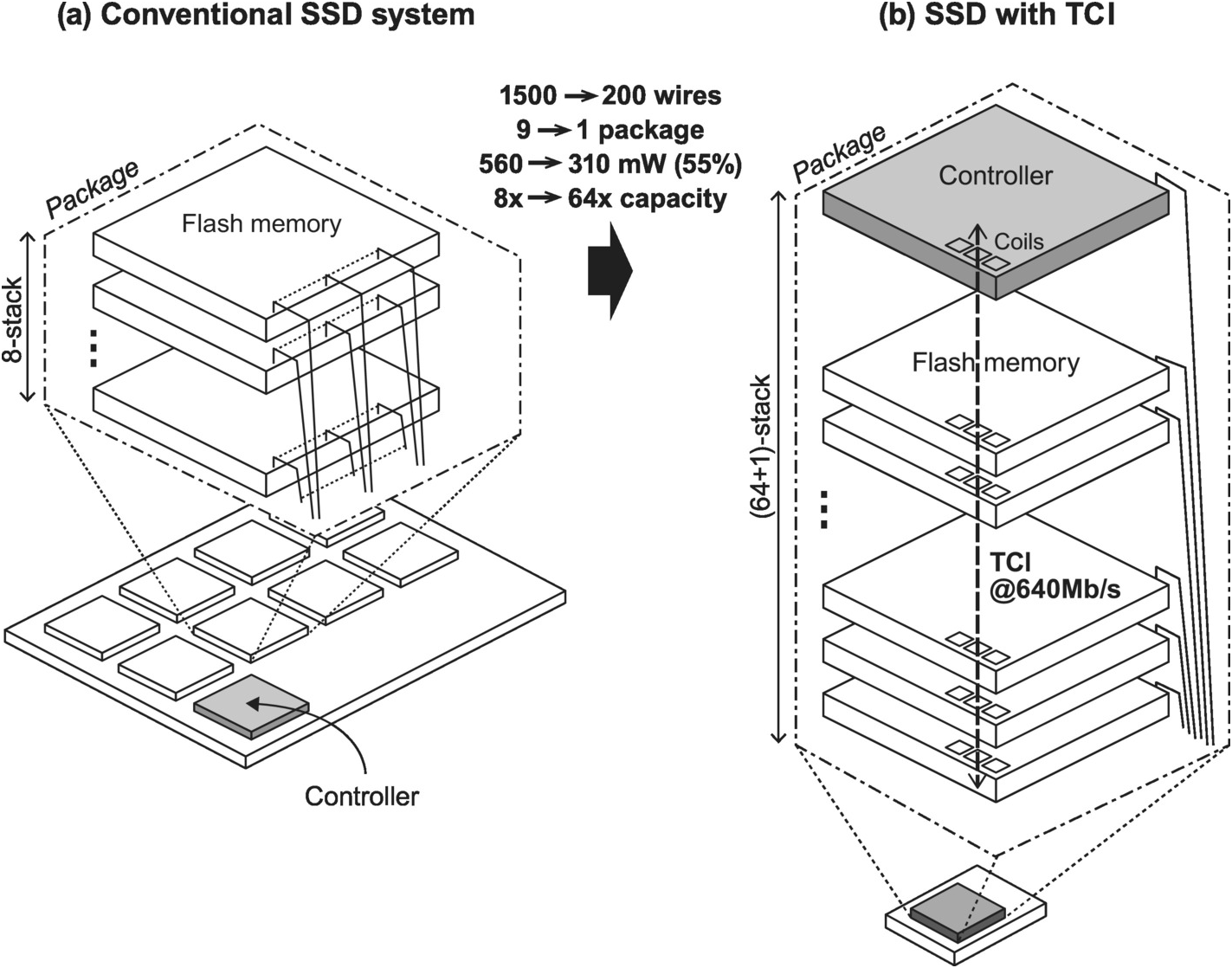

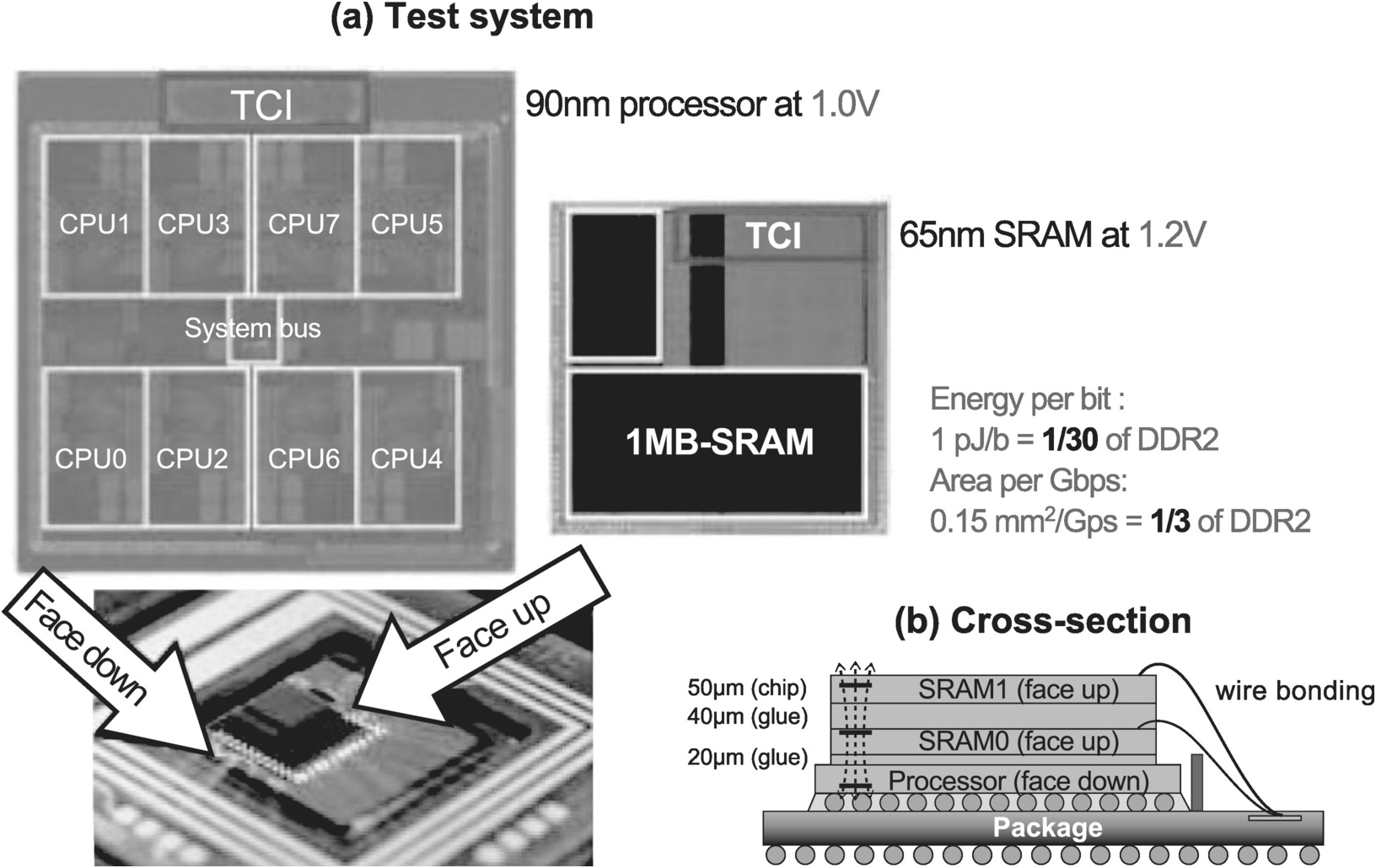

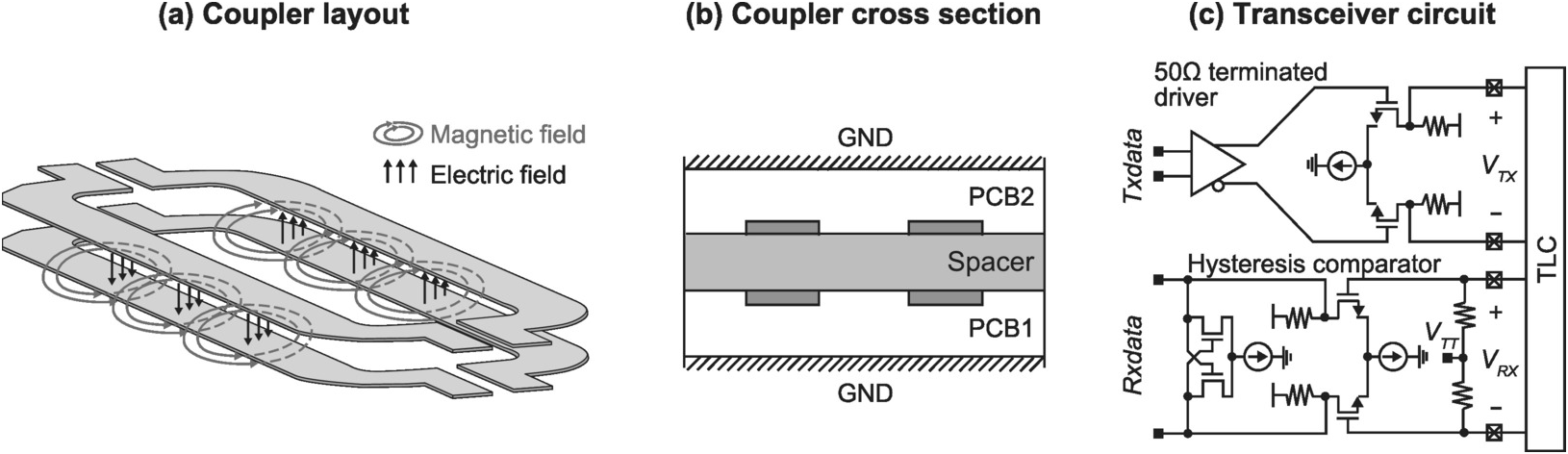

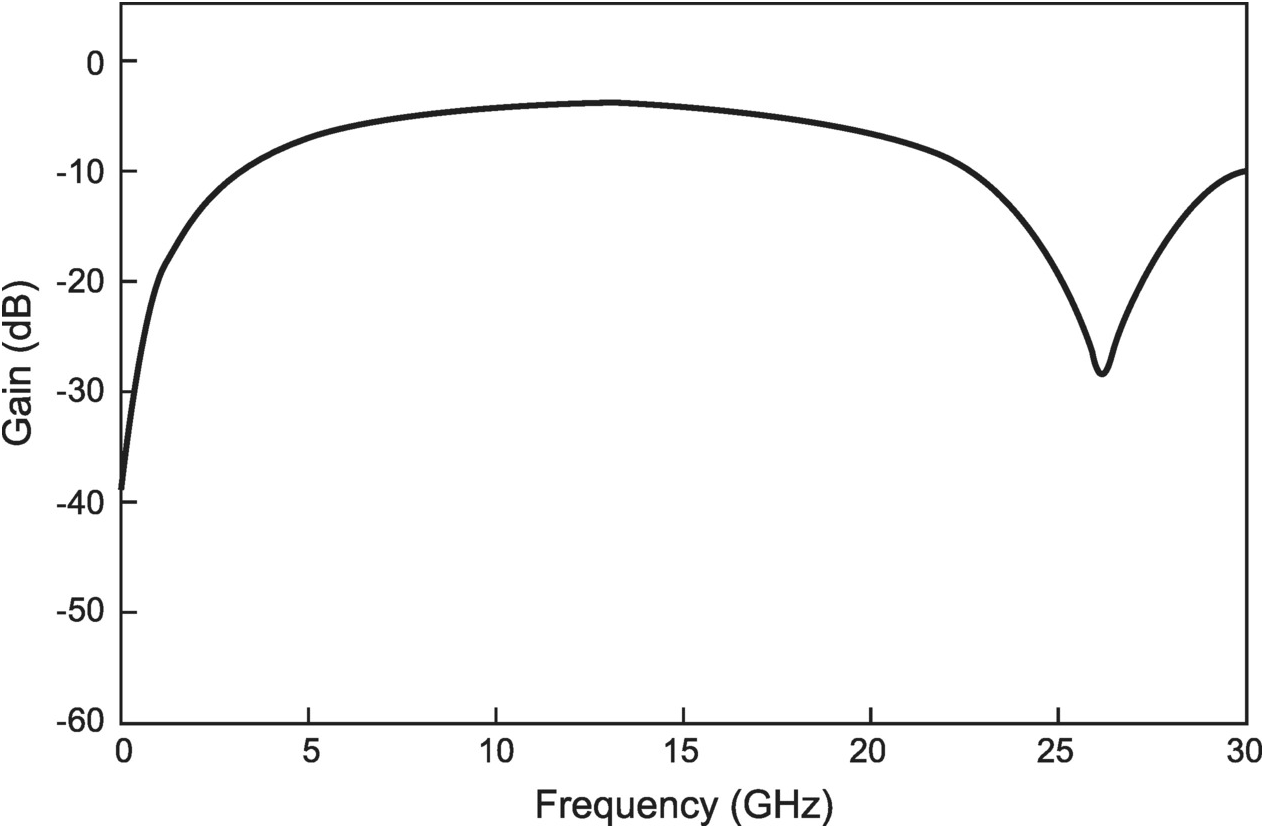

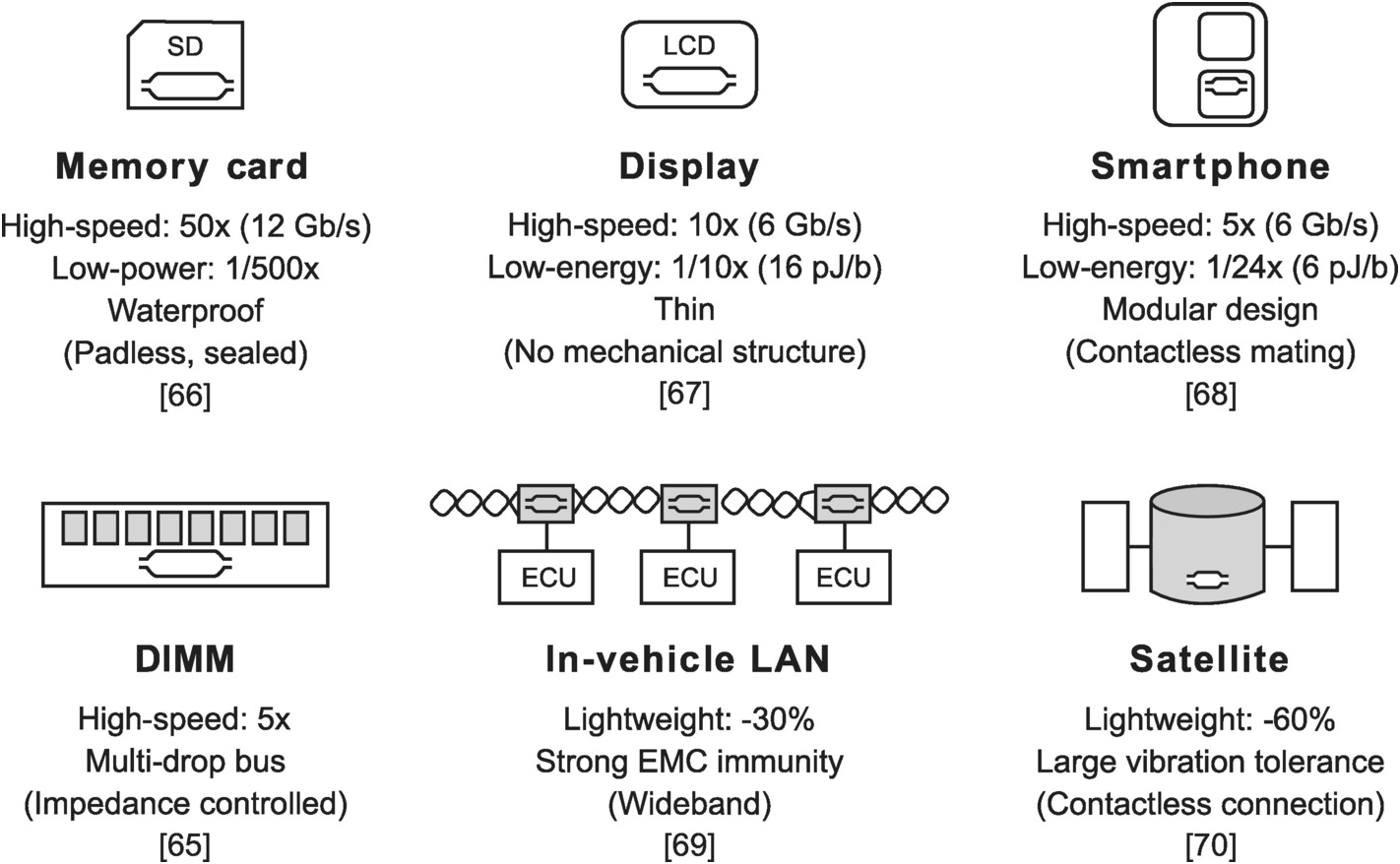

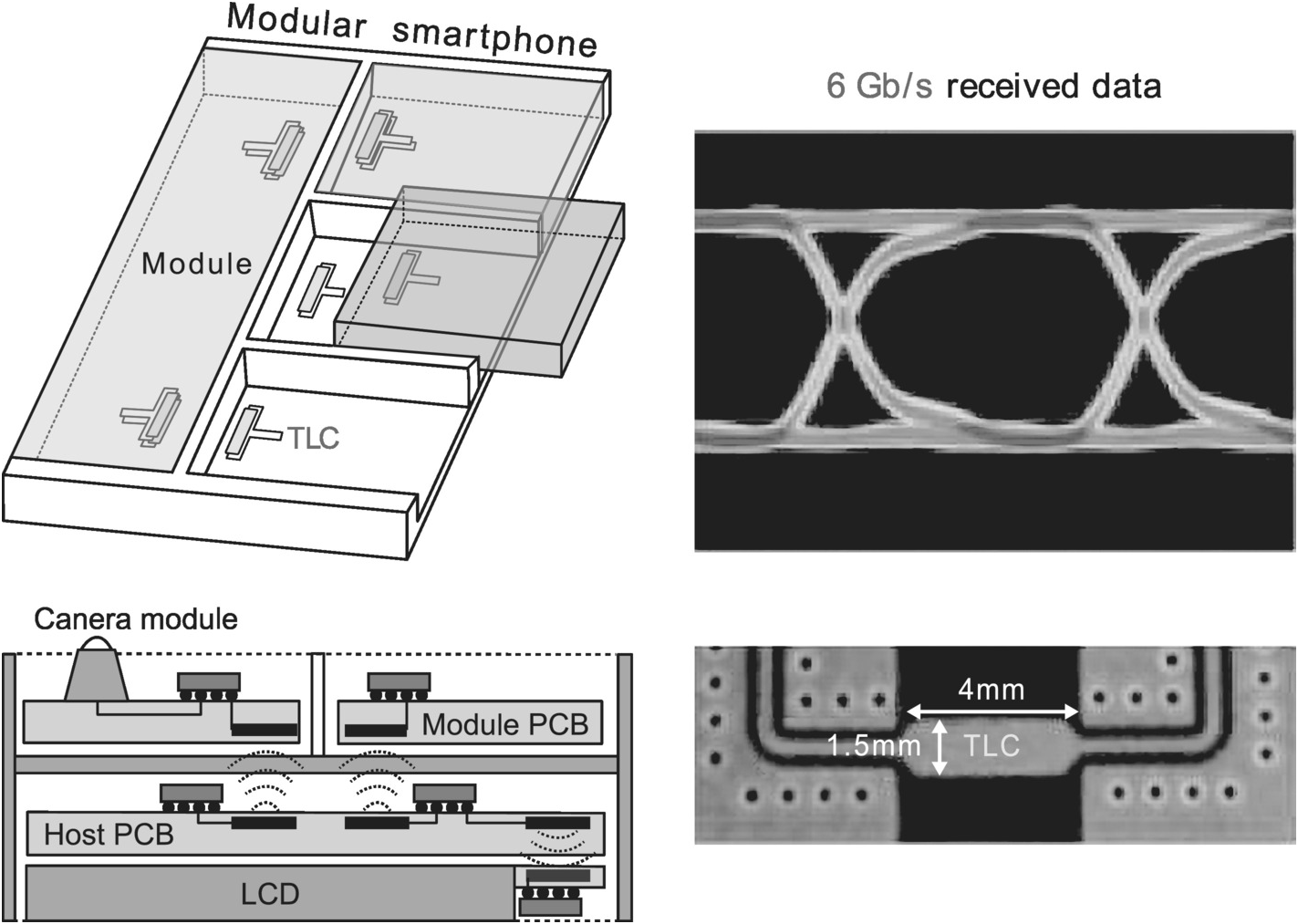

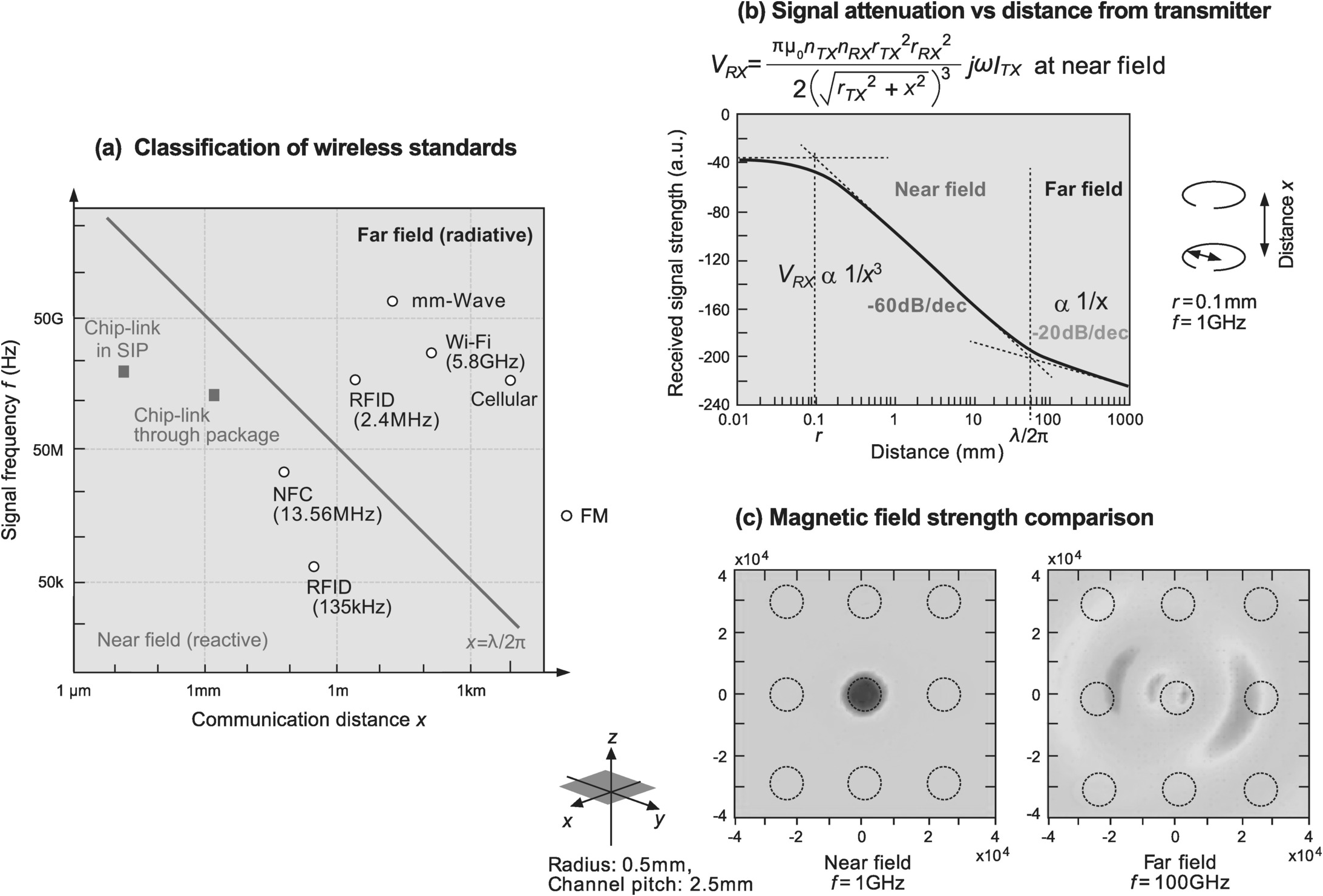

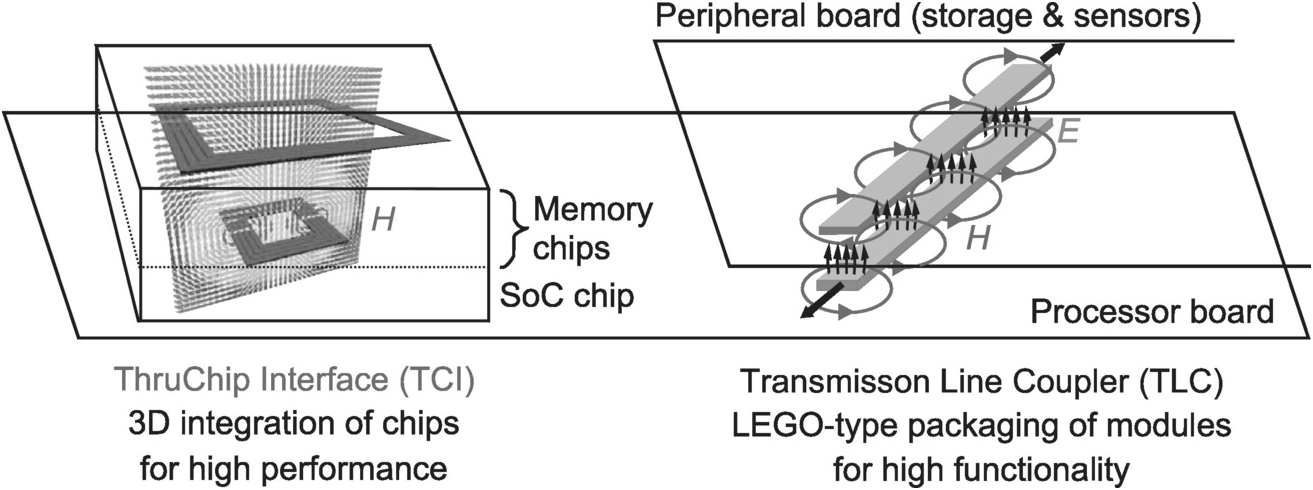

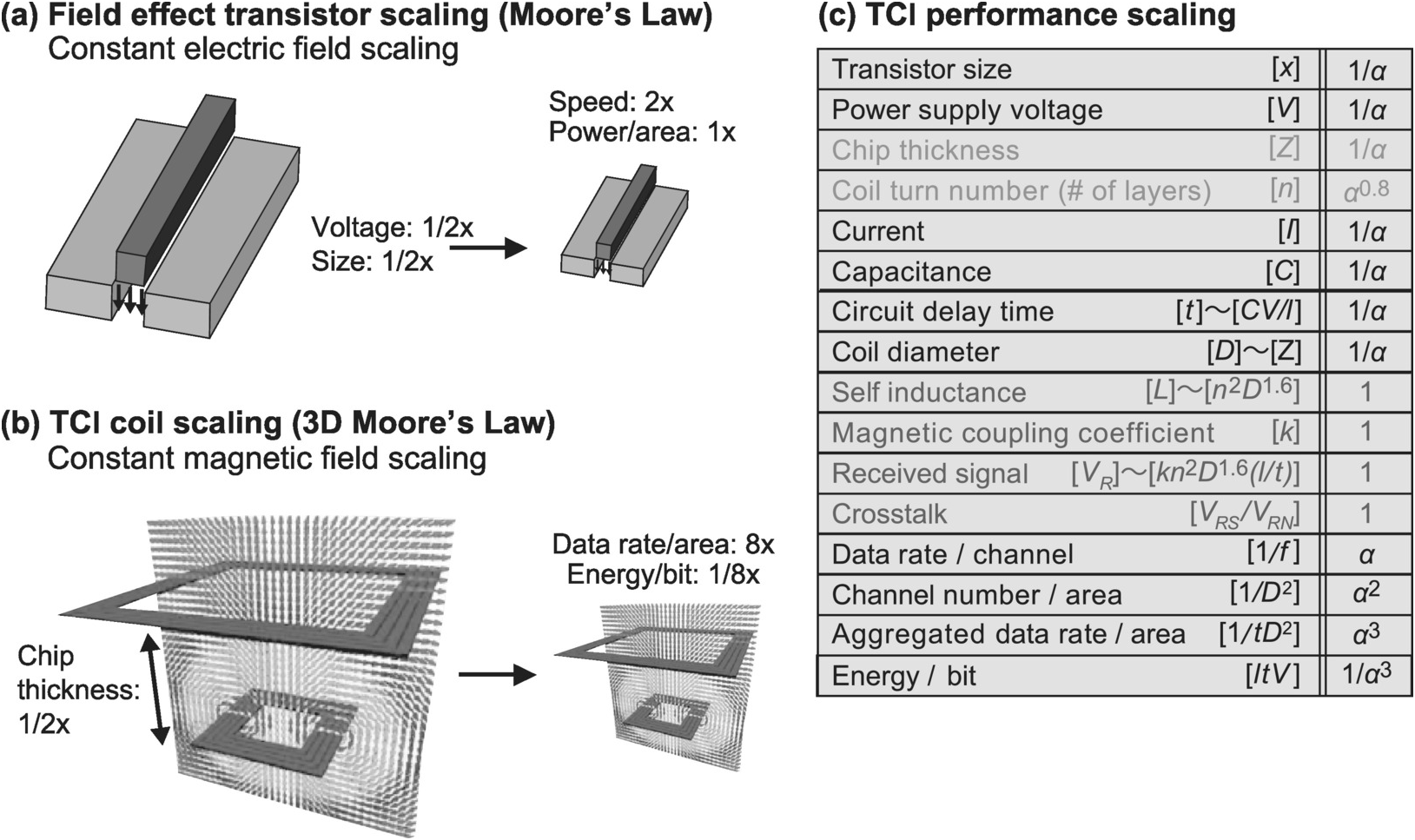

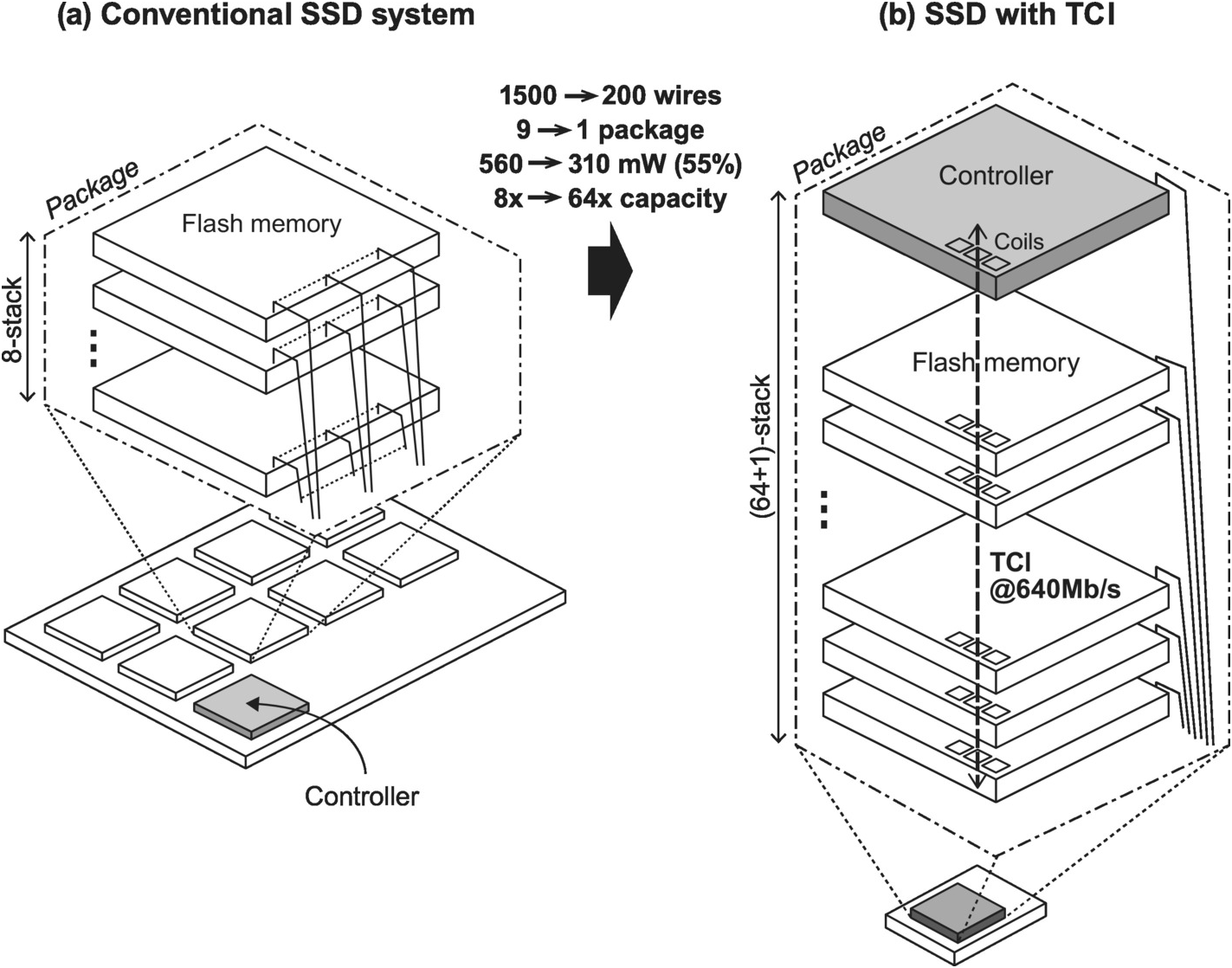

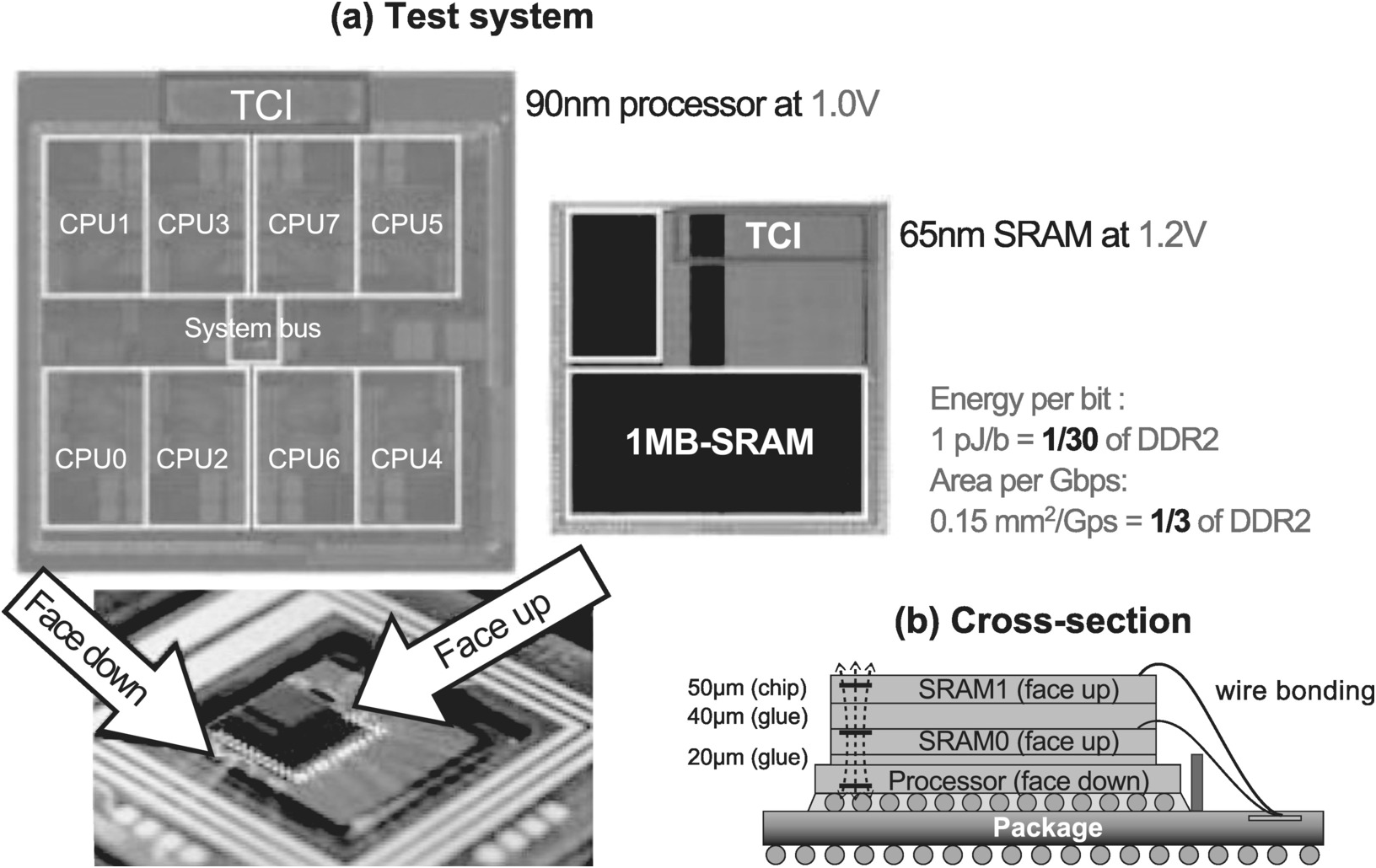

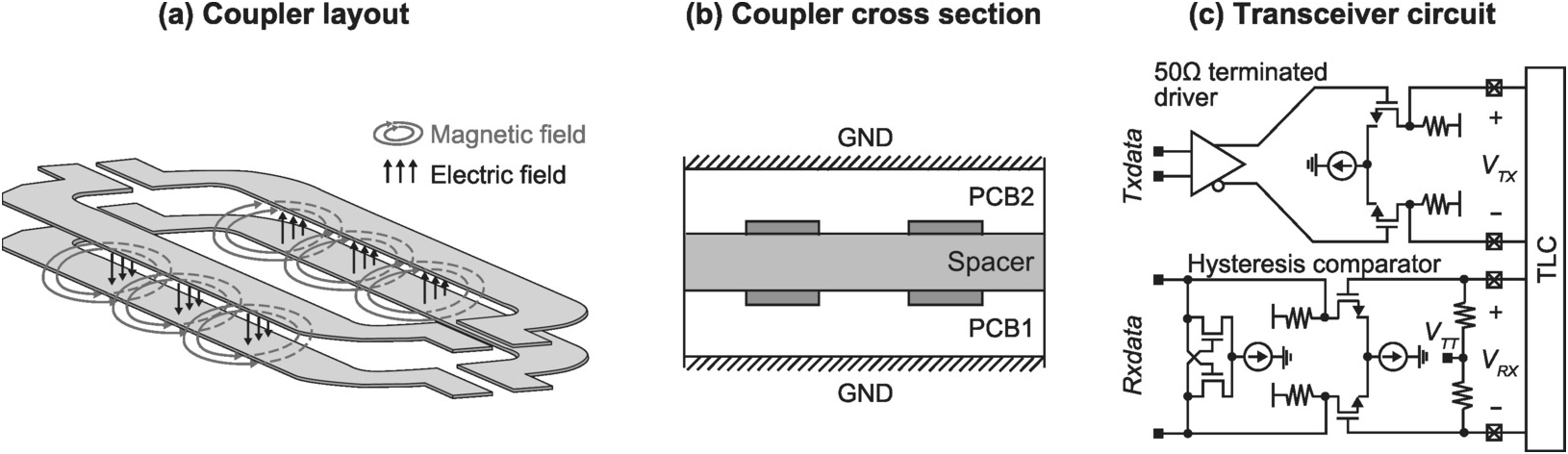

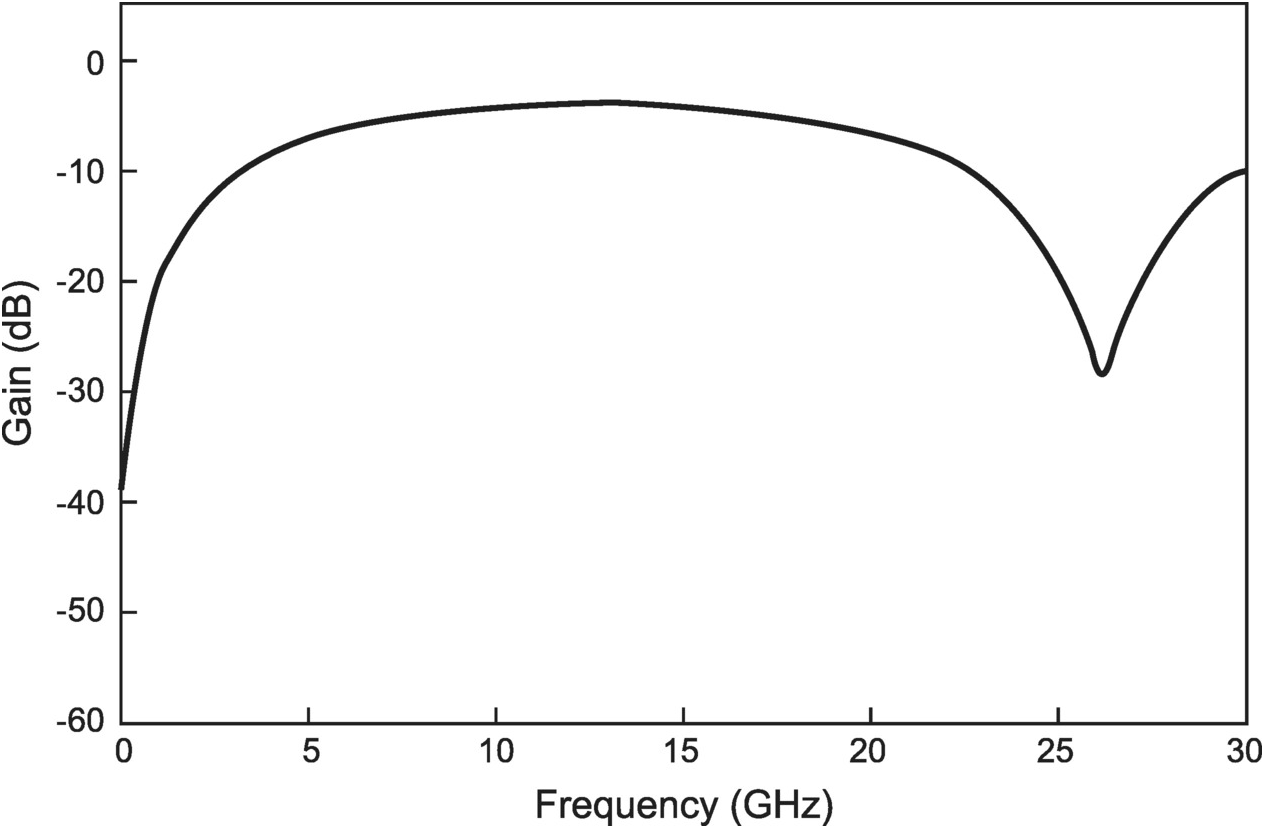

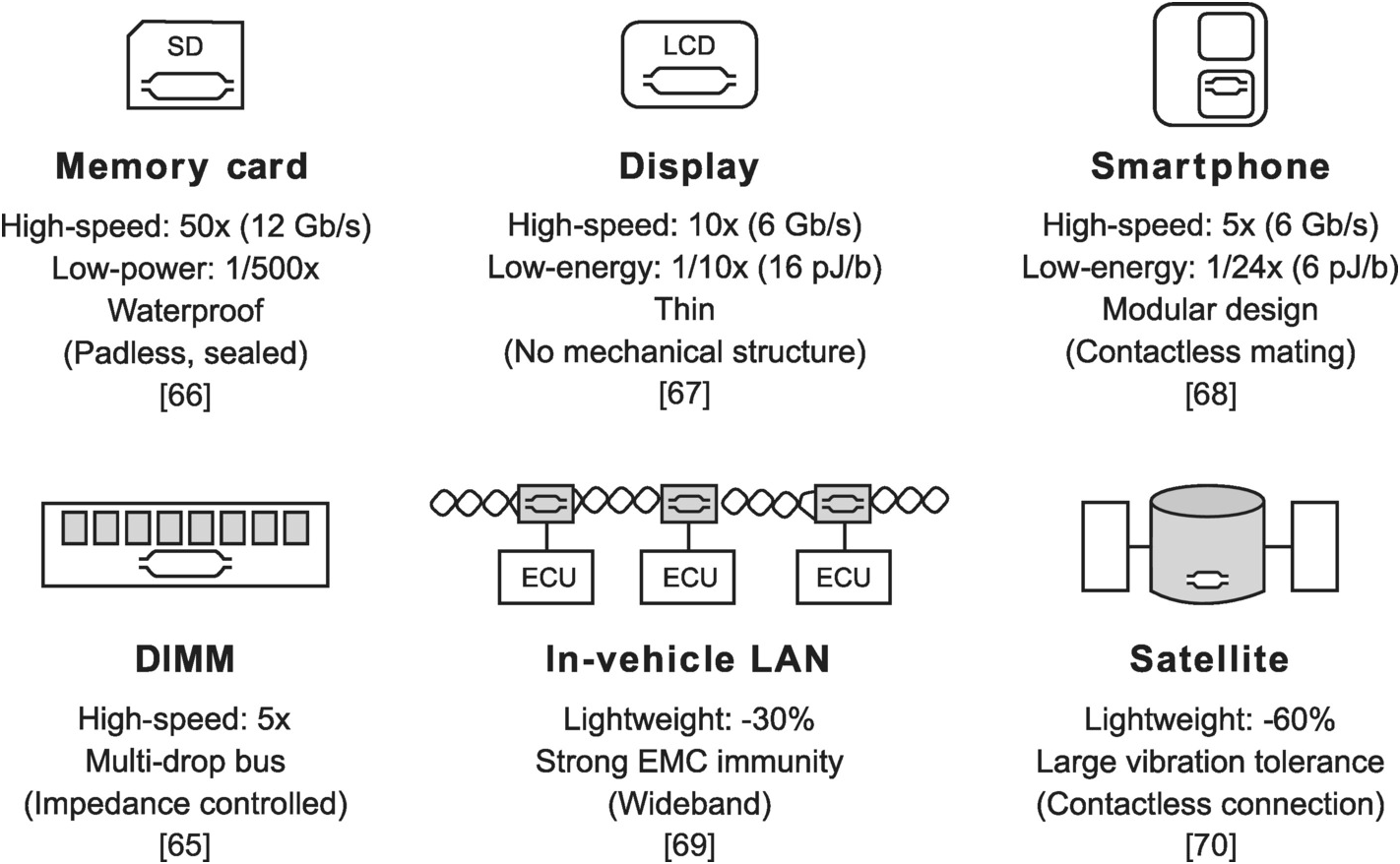

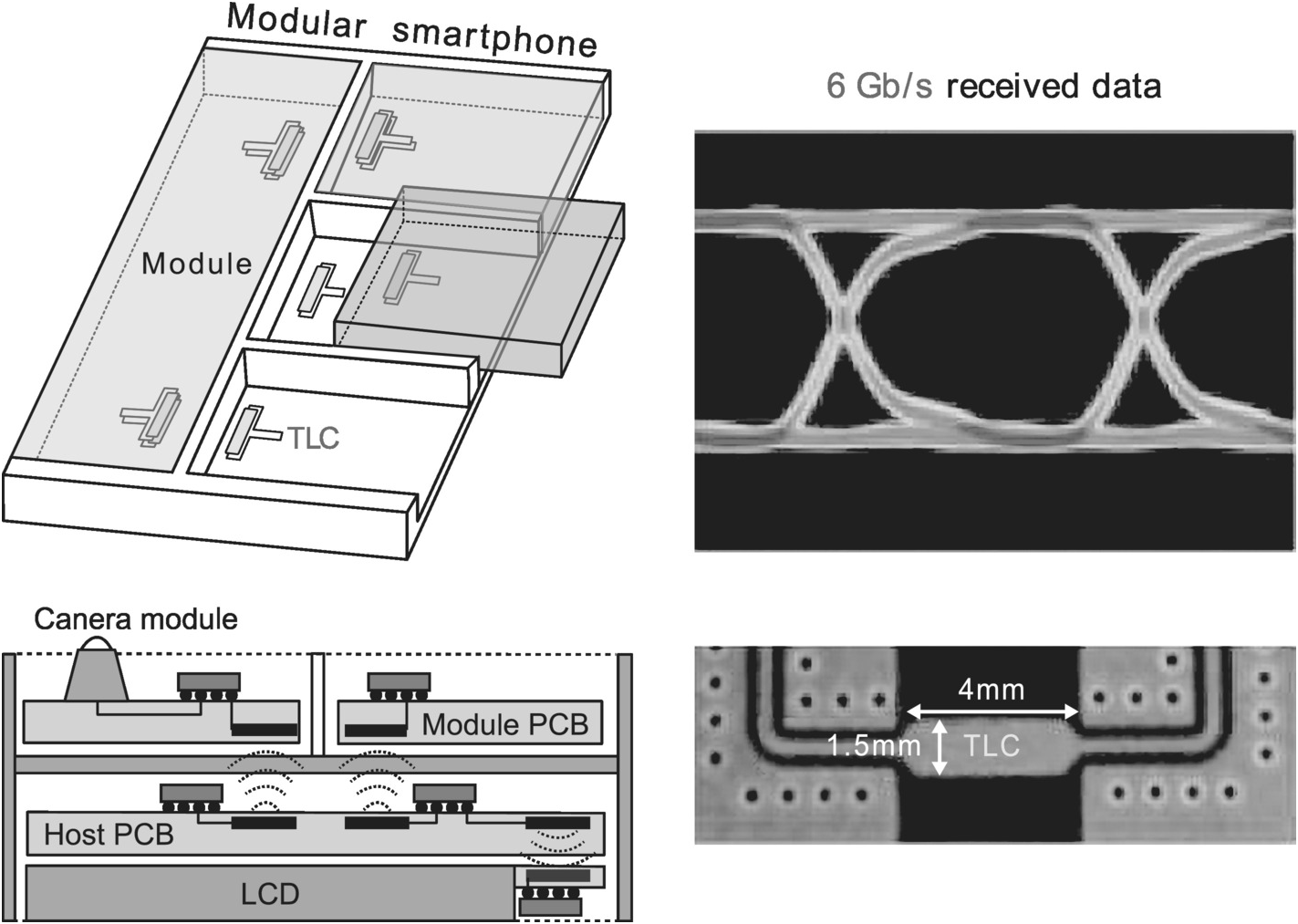

Figure 1.8 depicts the evolution of large-scale computer systems, their current challenges, and proposed solutions. The connection problem of the early large-scale computers, the tyranny of numbers, was solved by the invention of the von Neumann computer, integrated circuit, and solderless connection. However, the advance that has been achieved in all these technologies has made them the victim of their own success, with Moore’s law scaling and connector miniaturization each reaching its limits, and von Neumann bottleneck exacerbating. Furthermore, the adoption of neural network and deep learning in AI has once again brought to the forefront the challenges of scale and wiring in building hardwired computers. We believe the solutions can be found in our two wireless coupling technologies – ThruChip Interface (TCI) and Transmission Line Coupler (TLC). TCI, a magnetic coupling technology, enables stacking DRAMs with the system on a chip (SoC) to alleviate the von Neumann bottleneck. The same technology also enables stacking of static random-access memory (SRAM) with neural network chips implemented in field-progammable gate arrays (FPGAs) or reconfigurable processors to solve the challenges of scale and wiring in an AI computer. On the other hand, TLC, an electromagnetic coupling technology, enables a contactless connector that overcomes the scaling limits of its electromechanical counterpart. Each of these two wireless coupling technologies will be introduced in ensuing sections.

Figure 1.8 Evolution of solutions to the connection problem of a large-scale computer.

1.2 Energy-Efficient Computing

1.2.1 High-Performance IC

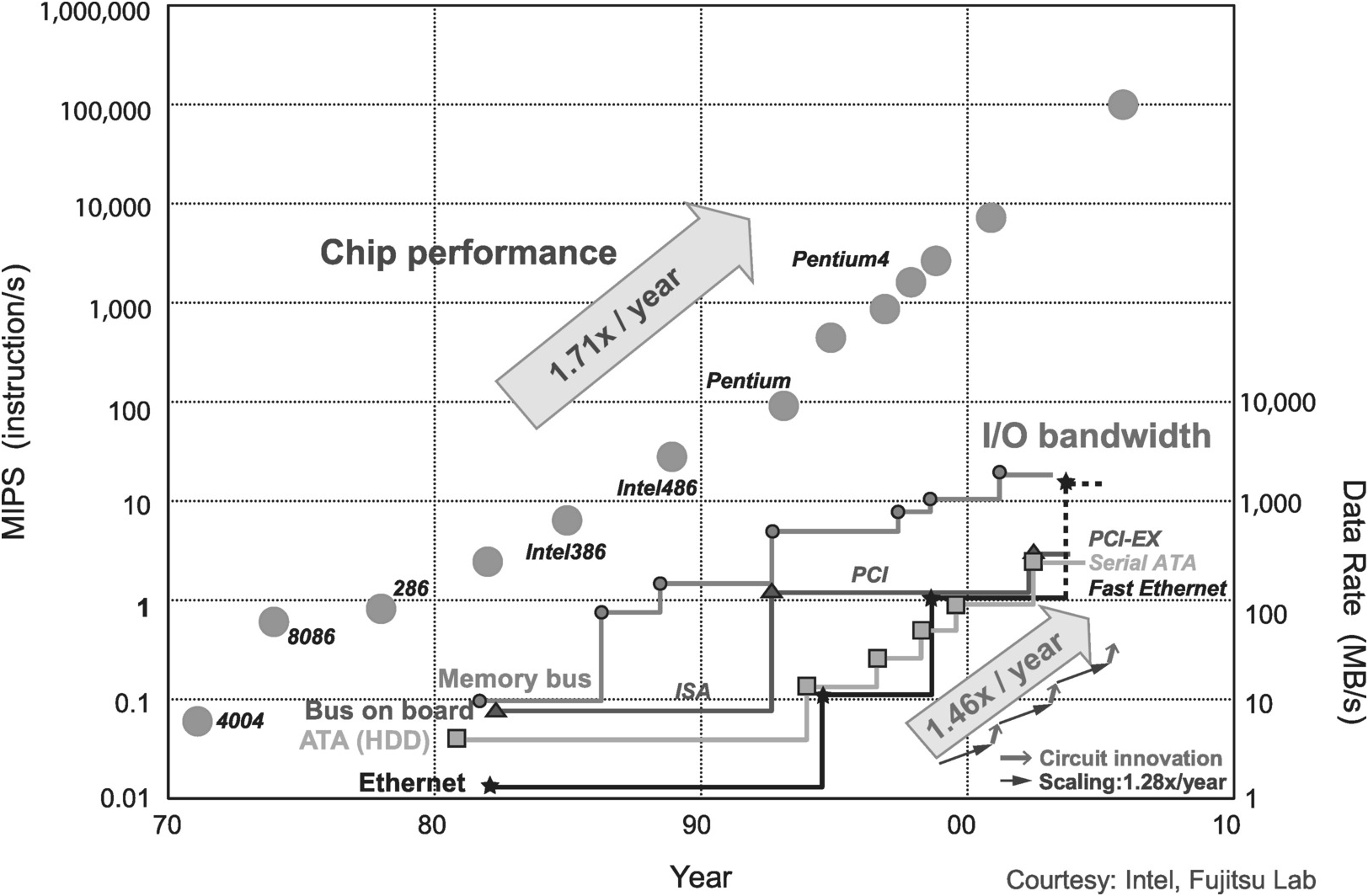

As noted in Figure 1.2 in Section 1.1, early IC development was performance driven, where process scaling delivered rapid performance increase as anticipated by Moore’s law. As an illustration, comparing the Intel Pentium from 1995 to the 8086 processor from 1980, in the span of 15 years, transistor count increased from 30,000 to 3,000,000, clock frequency from 5 to 300 MHz, computing power from less than 1 to several hundred MIPS, in line with the target rate of a twofold increase every two years. Since minimum line width shrank from 3 to 0.35 µm, device size scaled by approximately 0.75 times every two years. Such exponential growth was fueled by smooth progress in process scaling, including advances in lithography, process technology, wafer size, and manufacturing yield.

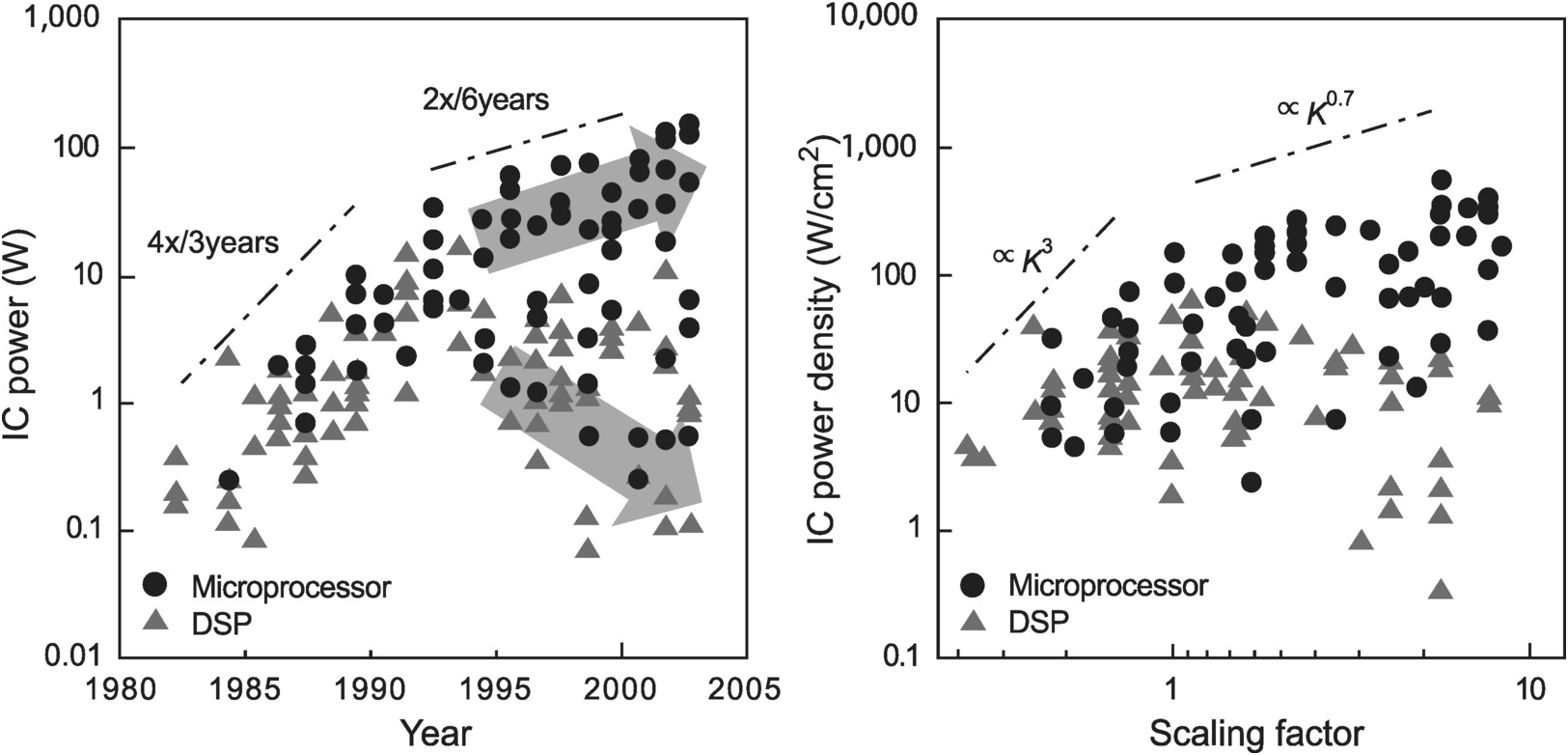

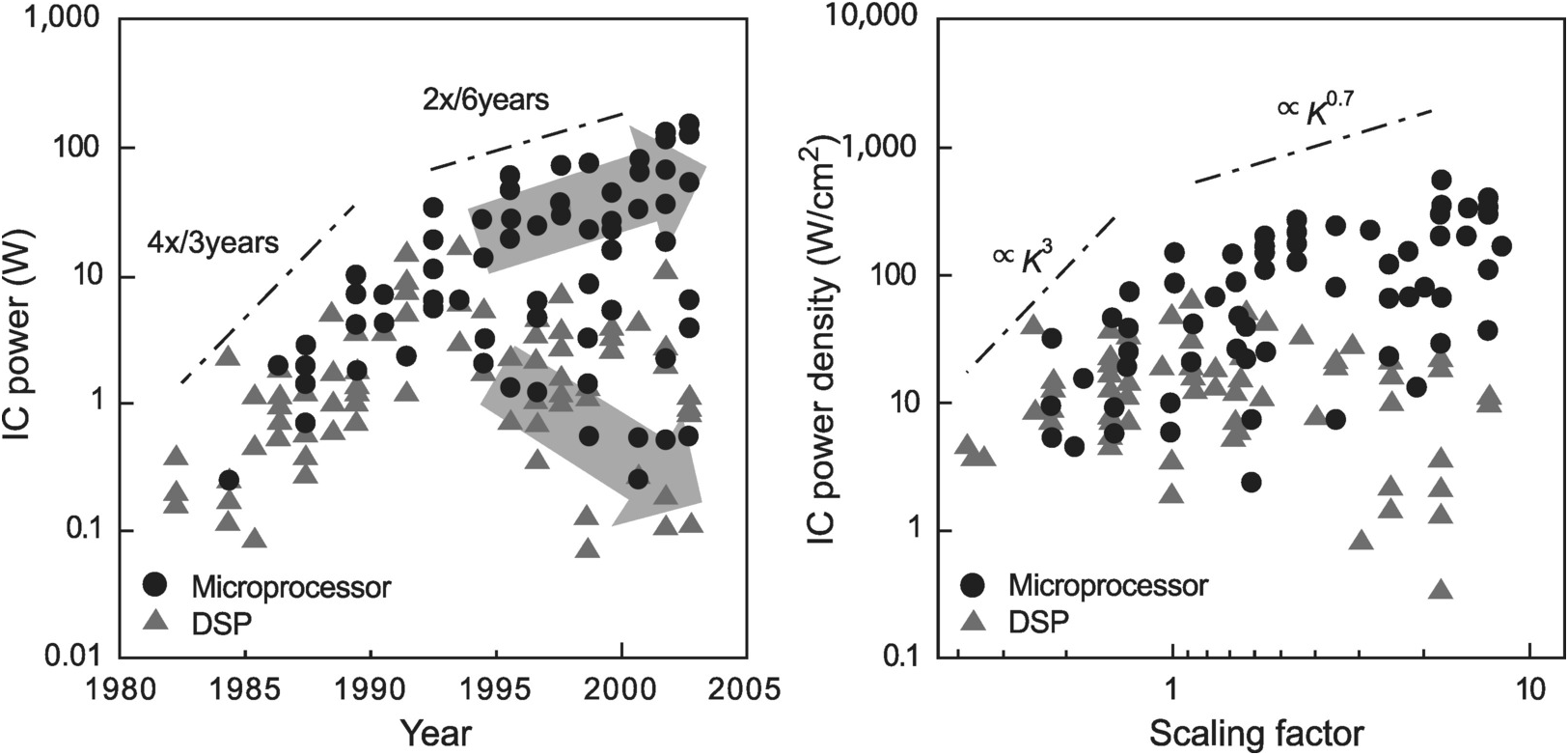

As explained in Section 1.1.2.3, under an ideal constant electric field scaling scenario where both dimensions and voltage are halved, delay is halved and power reduced to 1/4, while power density remains unchanged. However, if voltage is kept unchanged, delay is further reduced by half. At a time when the engineering workstation was the technology driver, and hence performance the driving factor, and with the switch from n-channel metal–oxide–semiconductor (NMOS) to complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS), which produced a three-orders-of-magnitude drop in power, constant voltage scaling became an easy choice over constant electric field scaling. But since constant voltage scaling results in a twofold increase in power and an eightfold increase in power density, from 1980 to around 1992, in 12 years IC power skyrocketed by increasing fourfold every three years (Figure 1.9).

Eventually when IC power exceeded 10 W, the problem of increasing power could no longer be ignored. Consequently, constant electric field scaling was introduced as a countermeasure and voltage started to drop. Nevertheless, the electric field had risen to the point where charge carrier mobility had reached saturation. As a result, while ideally current scales as V2, in reality it was scaling as V1.3 (Table 1.2). Furthermore, leakage current prevented V from fully scaling proportionally with device dimensions. For example, while V scaled from 2.5 to 1.8 and then 1.3 V for the 250, 180, and 130 nm process nodes respectively, its scaling slowed to 1.2, 1.0, and 0.9 V as process scaled to 90, 65, and 45 nm. As a result, power increase from scaling was not suppressed as much as desired, and IC power continued to climb at a rate of twice every six years (Figure 1.9). Eventually, in the second half of 1990s it approached 100 W, and the IC heat generation problem became quite severe.

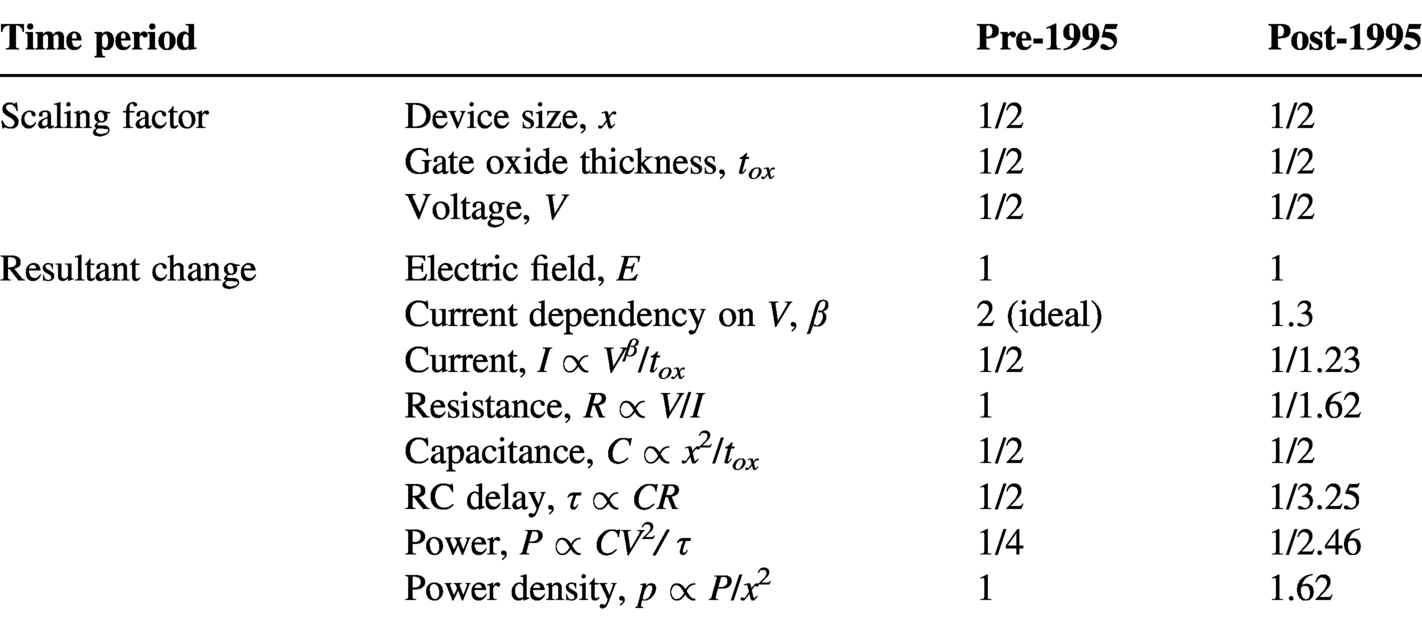

Table 1.2. Constant electric field scaling changes from around 1995.

| Time period | Pre-1995 | Post-1995 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaling factor | Device size, x | 1/2 | 1/2 |

| Gate oxide thickness, tox | 1/2 | 1/2 | |

| Voltage, V | 1/2 | 1/2 | |

| Resultant change | Electric field, E | 1 | 1 |

| Current dependency on V, β | 2 (ideal) | 1.3 | |

| Current, I | 1/2 | 1/1.23 | |

| Resistance, R | 1 | 1/1.62 | |

| Capacitance, C | 1/2 | 1/2 | |

| RC delay, τ | 1/2 | 1/3.25 | |

| Power, P | 1/4 | 1/2.46 | |

| Power density, p | 1 | 1.62 | |

1.2.2 Low-Power IC

In the decade from around 1995 to 2005, low power became a key design goal in IC development, in addition to performance. Solutions were developed to scale the power wall, while process scaling continued to raise the transistor count. During this period, the technology driver shifted from the engineering workstation to personal computer, which further exacerbated the power problem due to the shrinking system form factor.

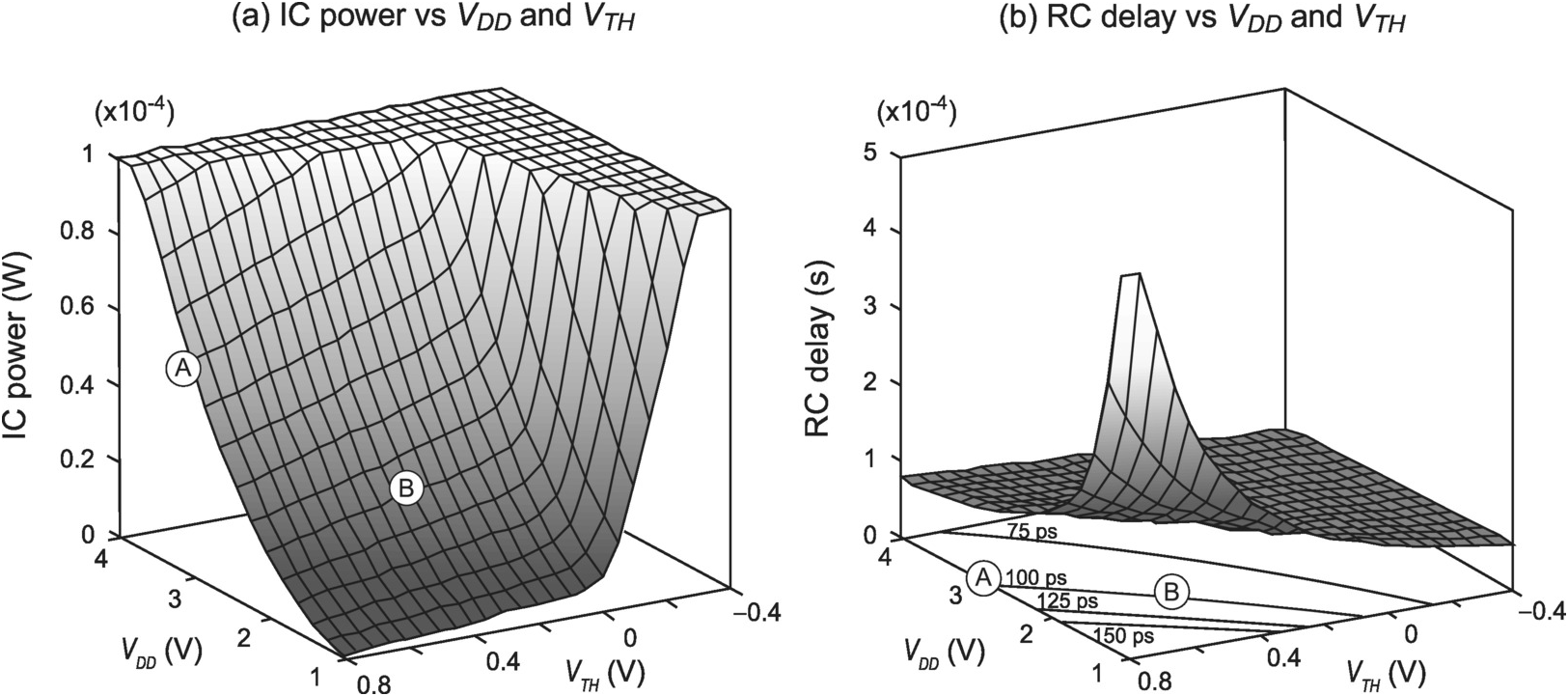

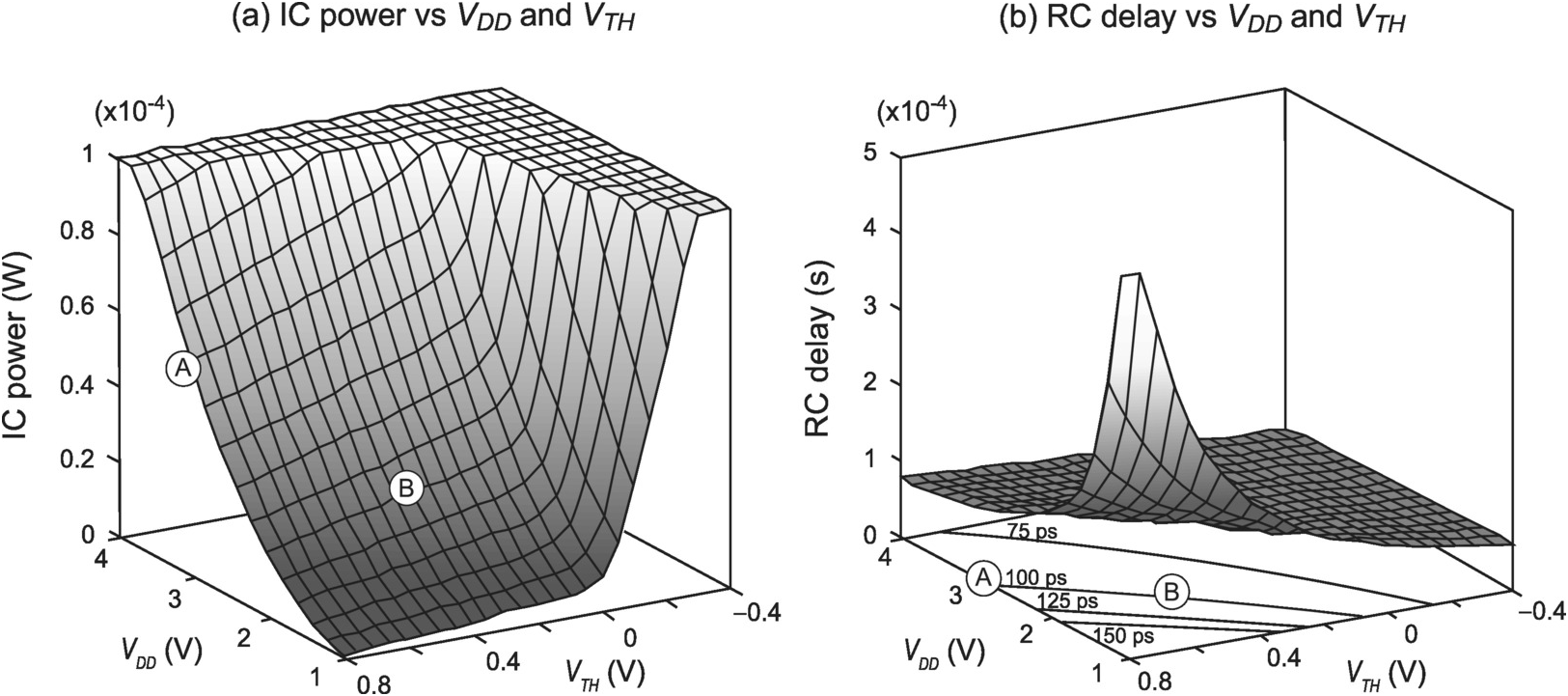

One low-power solution that drew a lot of attention was the optimization of drain voltage (VDD) and transistor threshold voltage (VTH). Figure 1.10 depicts how IC power and RC delay vary respectively as a function of VDD and VTH. When VDD is lowered to reduce power, delay goes up. But if VTH is lowered accordingly, it is possible to suppress the rise in delay while significantly reducing power. For instance, if VDD and VTH are lowered simultaneously to move from operating point A to B in Figure 1.10b along the equip–delay line of 100 ps, there is no change in delay, but total power is reduced as shown in Figure 1.10a.

Figure 1.10 IC power and RC delay as a function of VDD and VTH.

The optimization of VDD and VTH for the best trade-off of power and delay can be performed both dynamically during chip operation and spatially based on the design requirements of individual circuit blocks. With close monitoring of chip activity, VDD and VTH can be adjusted dynamically in accordance with the speed requirement at any particular time.

Spatially, circuit blocks that demand high speed can be supplied with a high VDD combined with a low VTH, while blocks that can afford to run slower are supplied with a low VDD combined with a high VTH, trading off execution time for lower power. The drawback is an increase in the complexity of the power supply, especially in the case of spatial optimization, where multiple voltages have to be generated at the same time.

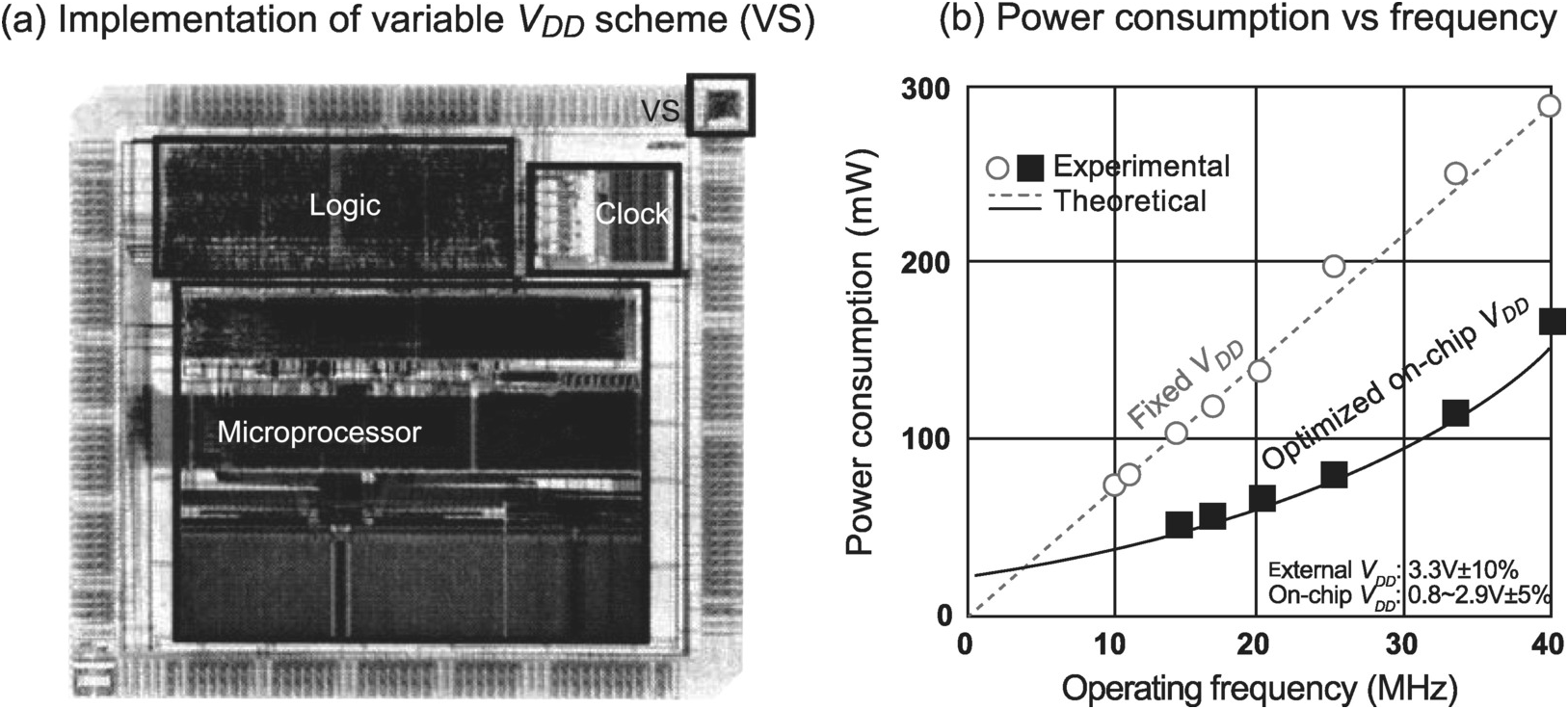

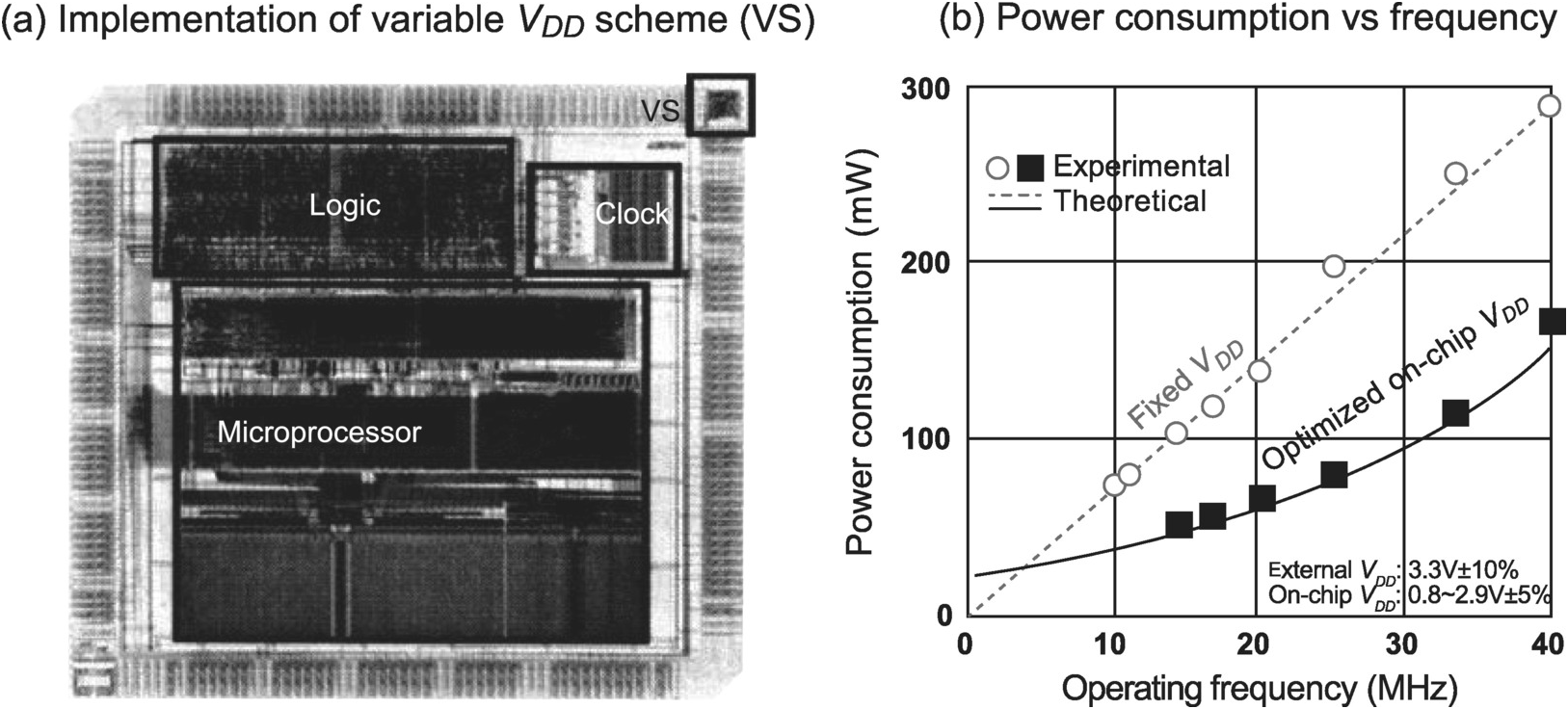

By moving the on-board DC–DC converter that supplies VDD to on-chip for internal adjustment, and by varying the substrate bias to adjust VTH, it is possible to dynamically optimize these two parameters. Figure 1.11 depicts an example processor that implemented an on-chip, variable VDD supply. By setting VDD to its minimum acceptable value for correct operation at any particular frequency, power consumption was reduced by up to 50%.

Figure 1.11 Power consumption reduction through VDD optimization.

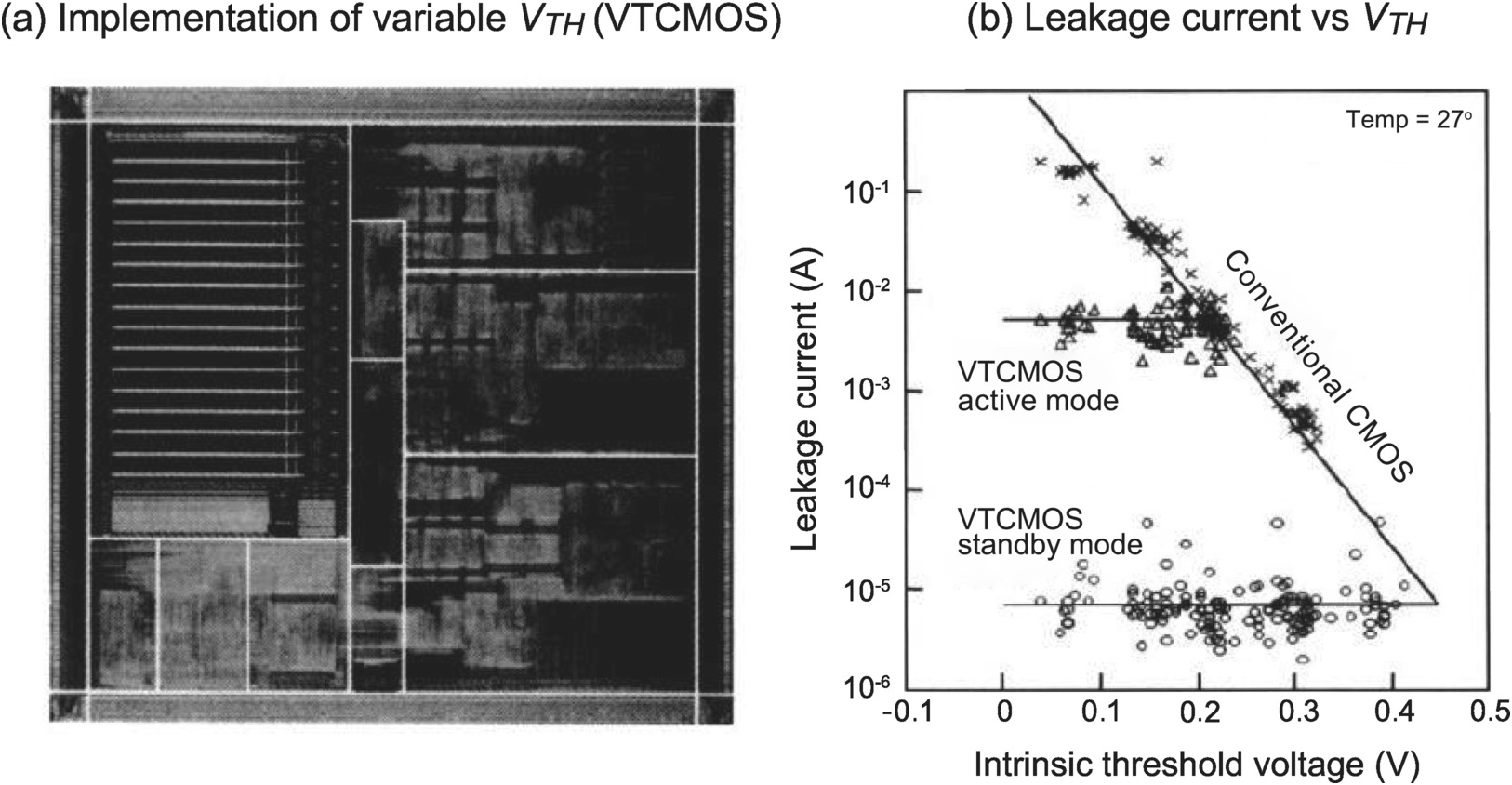

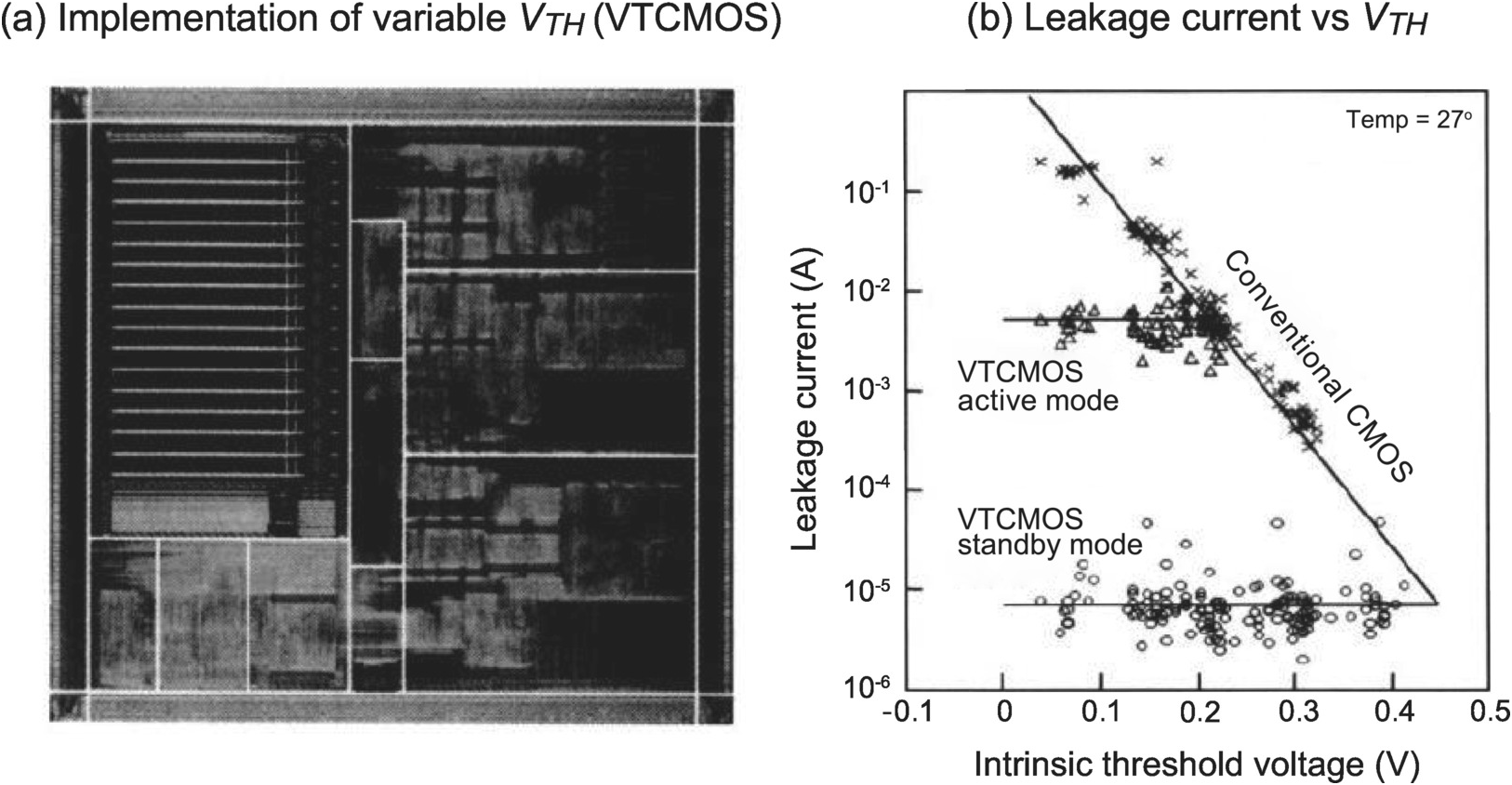

Figure 1.12 depicts an example image processor that implemented an on-chip substrate bias circuit to vary VTH to achieve significant reduction in leakage current.

Figure 1.12 Leakage current reduction through VTH optimization. (b)

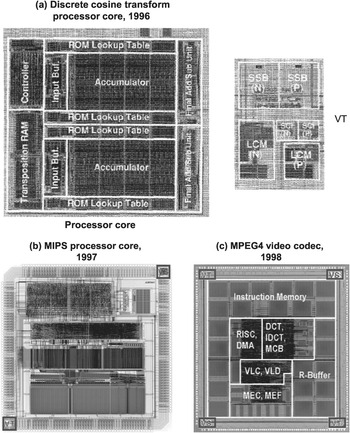

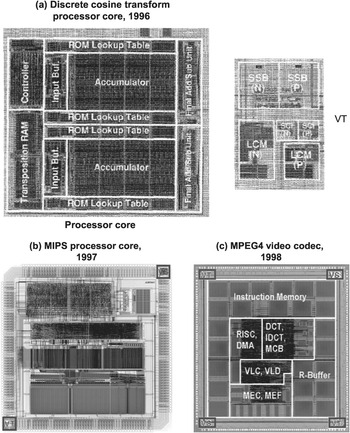

Between 1996 and 1998, Toshiba in Japan successfully developed the world’s first processors with controllable VDD and VTH (Figure 1.13, [Reference Suzuki, Mita, Fujita, Yamane, Sano, Chiba, Watanabe, Matsuda, Maeda and Kuroda10, Reference Kuroda, Fujita, Mita, Nagamatsu, Yoshioka, Suzuki, Sano, Norishima, Murota, Kako, Kinugawa, Kakumu and Sakurai12–Reference Takahashi, Hamada, Nishikawa, Arakida, Fujita, Hatori, Mita, Suzuki, Chiba, Terazawa, Sano, Watanabe, Usami, Igarashi, Ishikawa, Kanazawa, Kuroda and Furuyama13]). The technology was soon adopted by Transmeta, followed by Intel and AMD, validating the need for processor developers to counter the pressing power problem.

Figure 1.13 Example ICs with variable VDD (VS) and VTH (VT).

Nonetheless, even though Intel had been aggressively driving up processor performance by raising clock frequency, by October 2004, the company decided to change course and shifted focus away from pushing clock frequency beyond 4 GHz. It was more a business than engineering decision since it was technically possible to further raise the clock frequency. But by doing so, the leakage and heat problem would become too expensive to solve. Instead, Intel shifted to boosting performance by increasing the number of processor cores.

1.2.3 Low-Power IC Interface

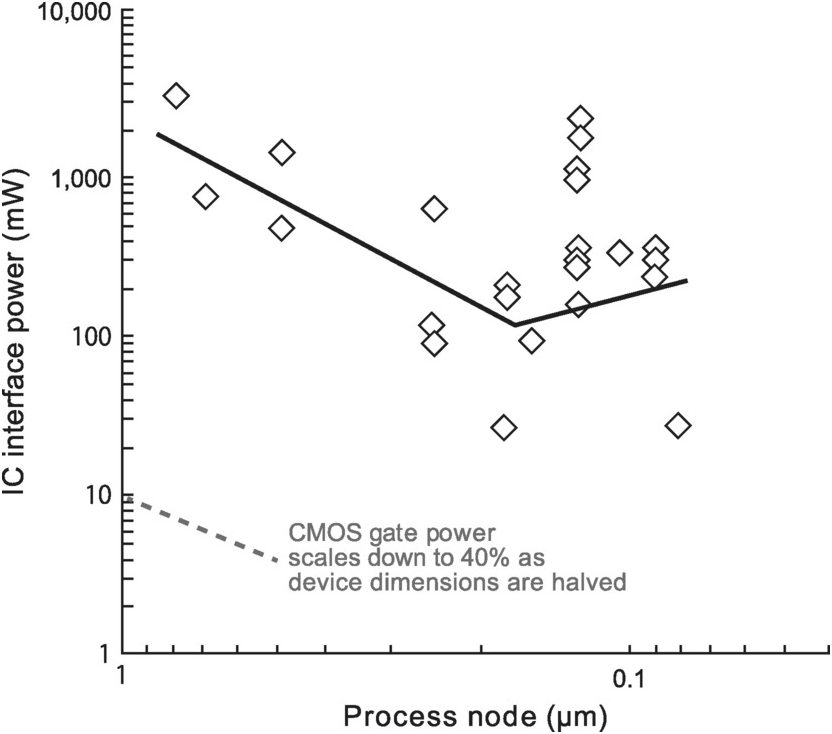

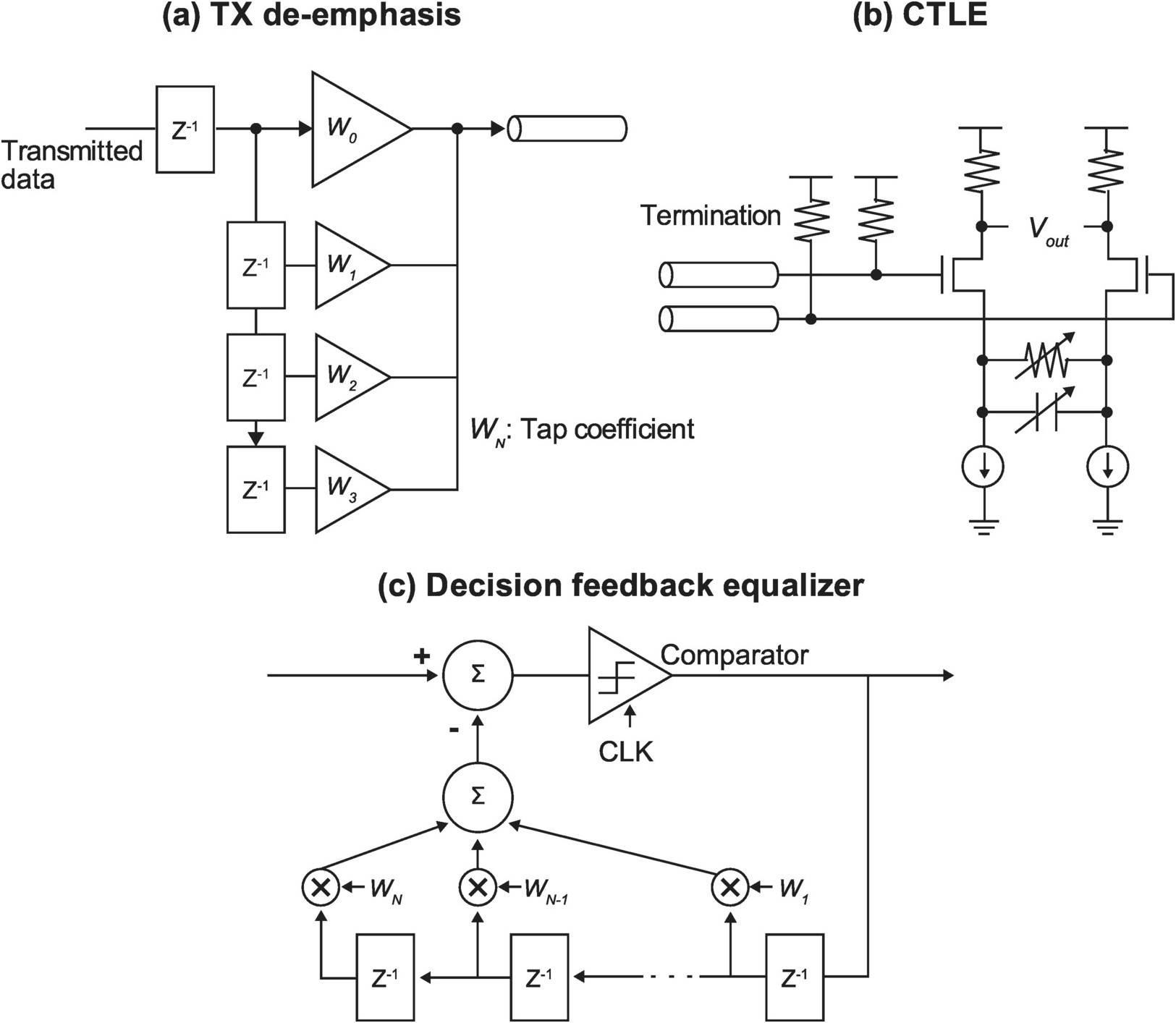

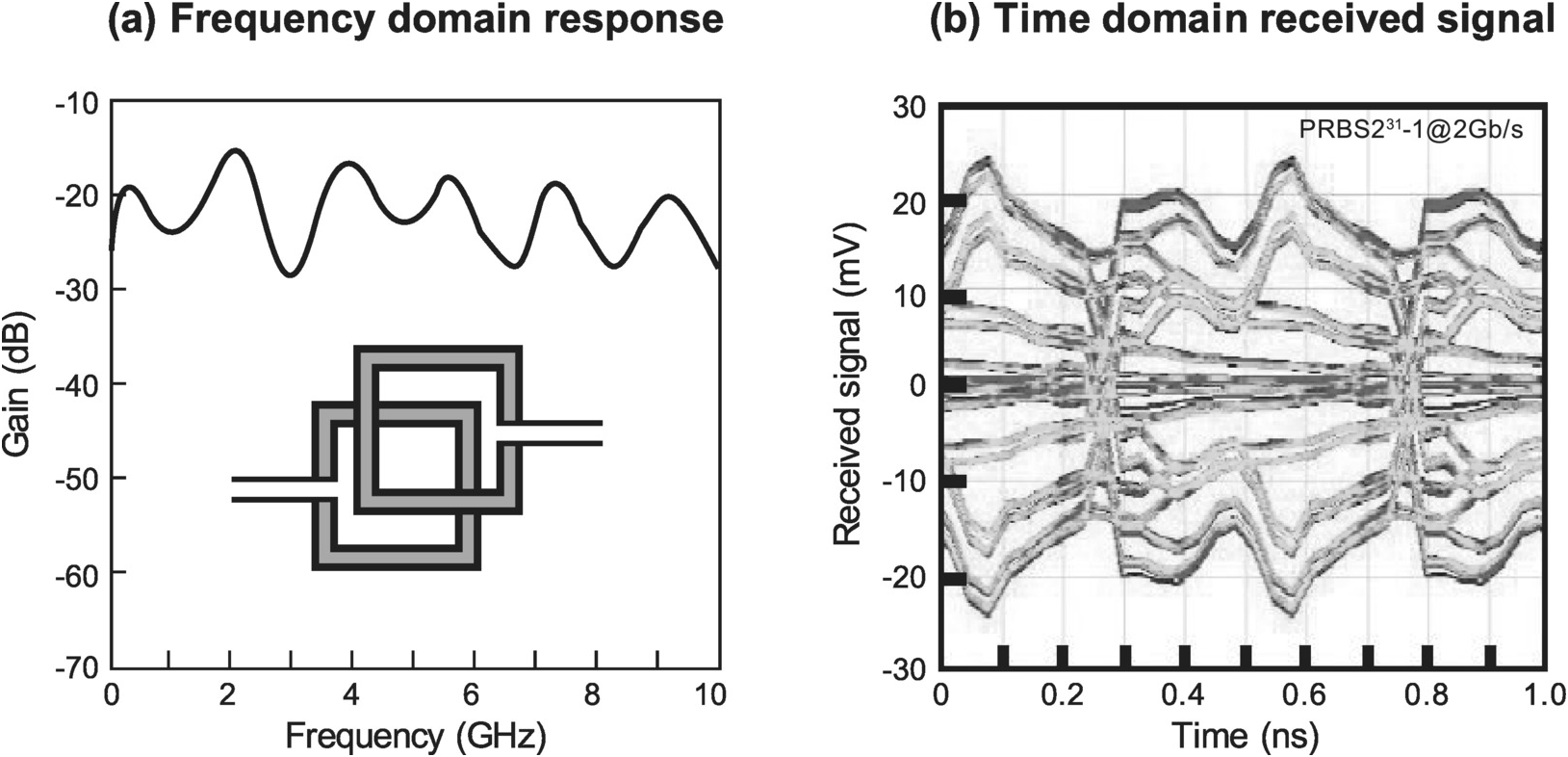

An IC must communicate with the outside world to perform useful functions. Therefore, in minimizing overall system power, in addition to minimizing power of the IC itself, IC interface power must also be taken into consideration. Conceptually, the IC interface can be divided into two components – the on-chip input/output (I/O) circuits (transmitters or drivers, and receivers) and the off-chip physical interconnections. Power optimization of the IC interface thus requires both low power I/O circuits and off-chip interconnect design.

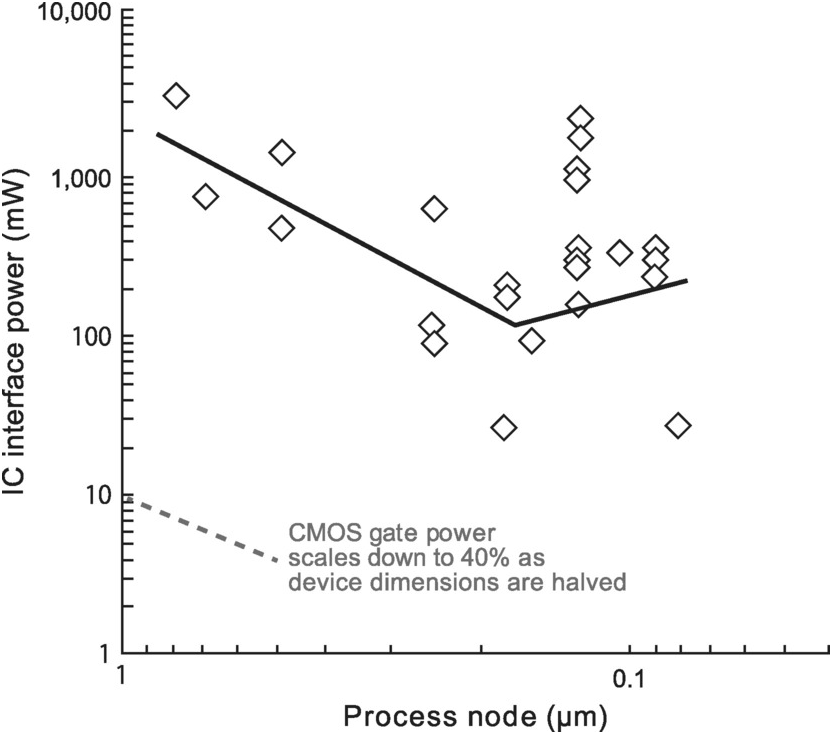

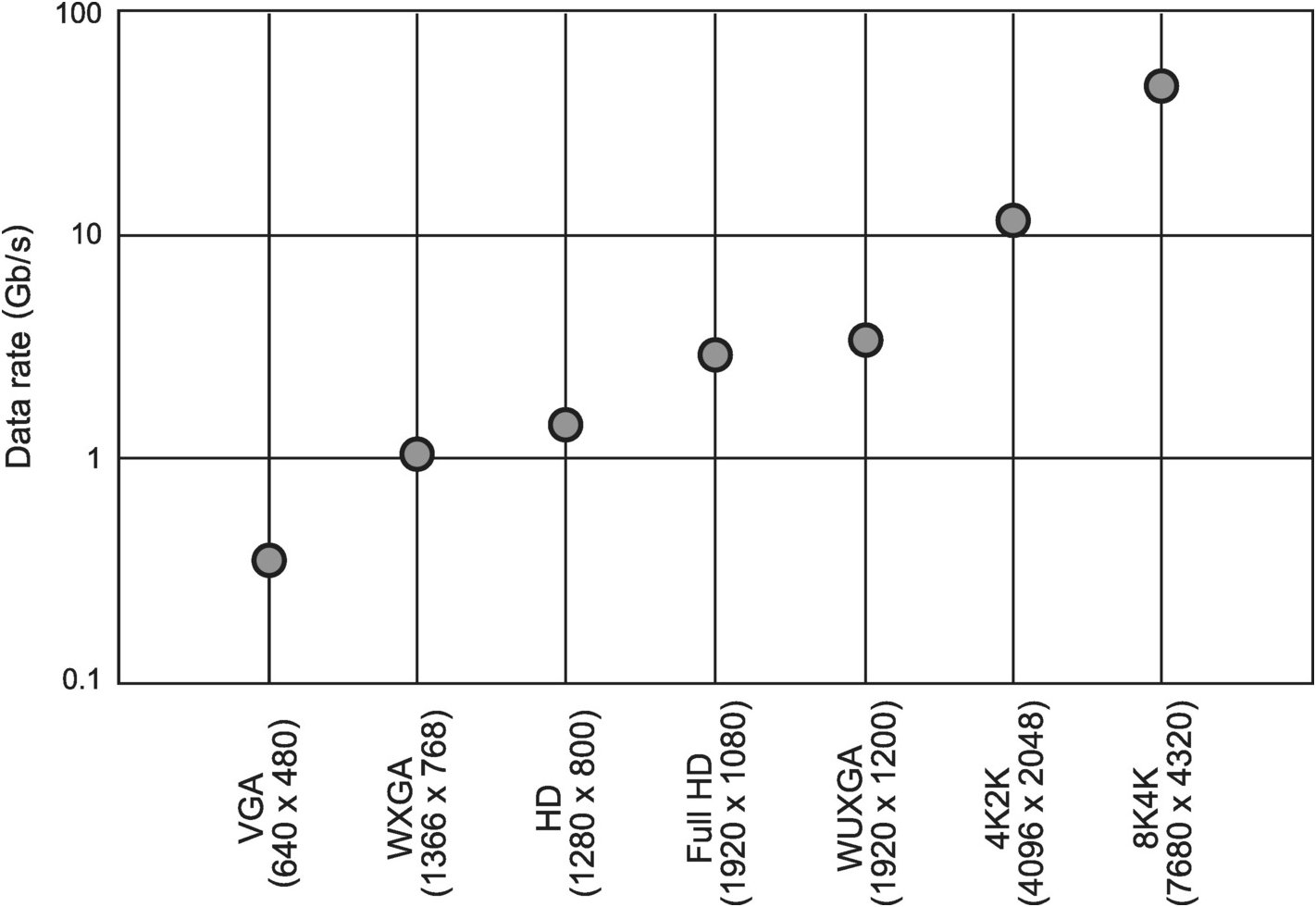

Signal transmission in and out of the IC involves generating an analog waveform that represents the transmitted digital information, preserving the integrity (quality) of the waveform as it propagates, and receiving and correctly extracting the embedded digital information. It is therefore an operation in both the digital and analog domains. As a result, unlike their digital counterpart, I/O circuits’ performance, including power consumption, does not scale proportionally with process. As transmission speed increases, circuit design must change to support the higher data rates, leading to rising power. For example, buffers must be inserted in the clock path for higher speed clock distribution to compensate for the higher attenuation at higher frequency. Furthermore, increased adoption of common mode logic (CML) circuits to support faster digital switching also contributes to higher power. As a result, while IC interface power roughly followed the scaling of CMOS gate power in earlier processes, from around the 130 nm node it reversed course and rose steadily thereafter (Figure 1.14). To counter this trend, an effective solution is to limit the increase in signal data rate and instead increase the number of parallel signals transmitted to increase total interface bandwidth. This was facilitated by the shift in the placement of I/O circuits from being along the perimeter to across the surface of the IC, leading to the shift from wirebond to flip-chip packaging.

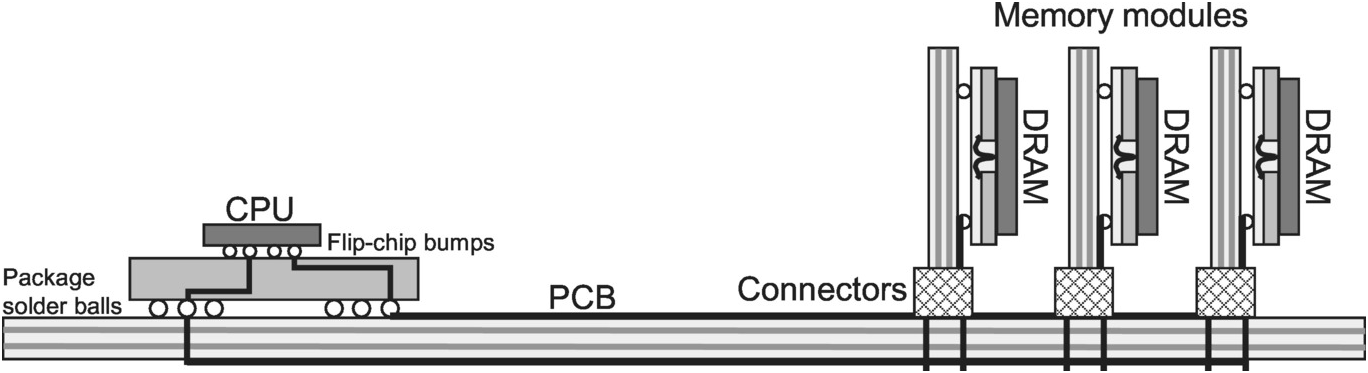

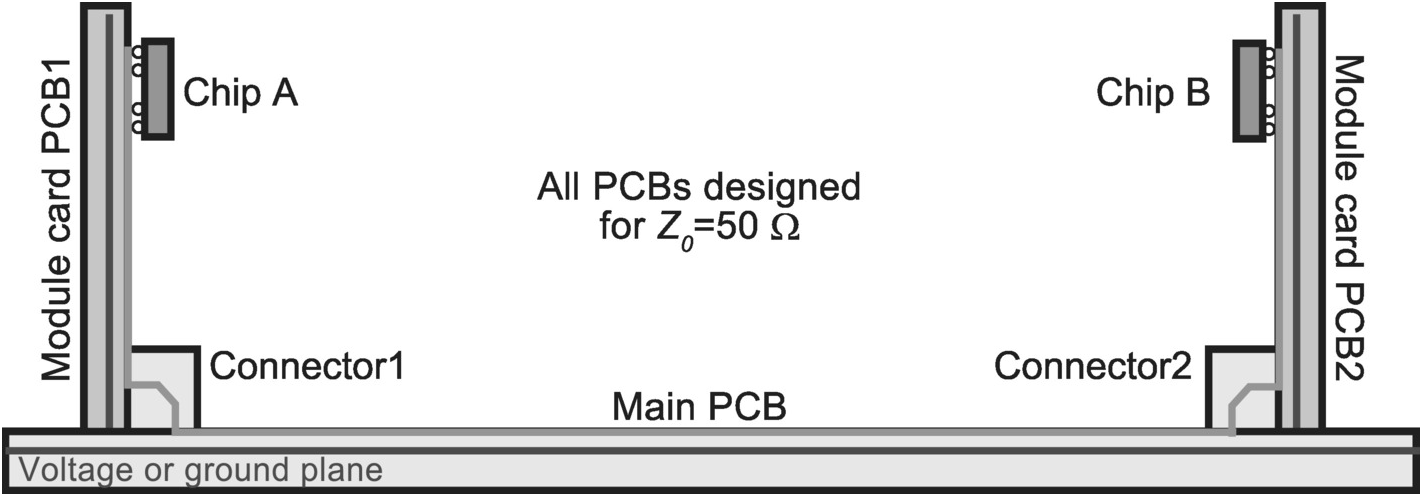

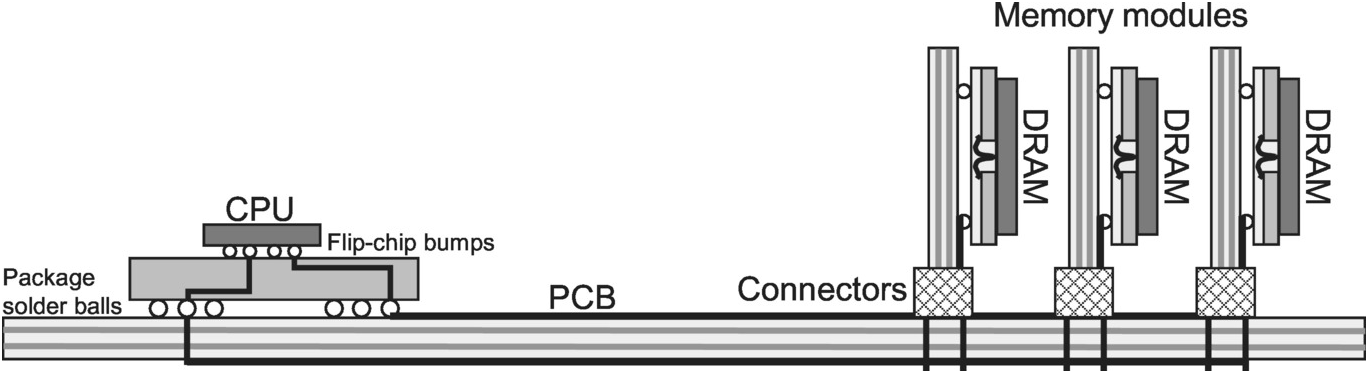

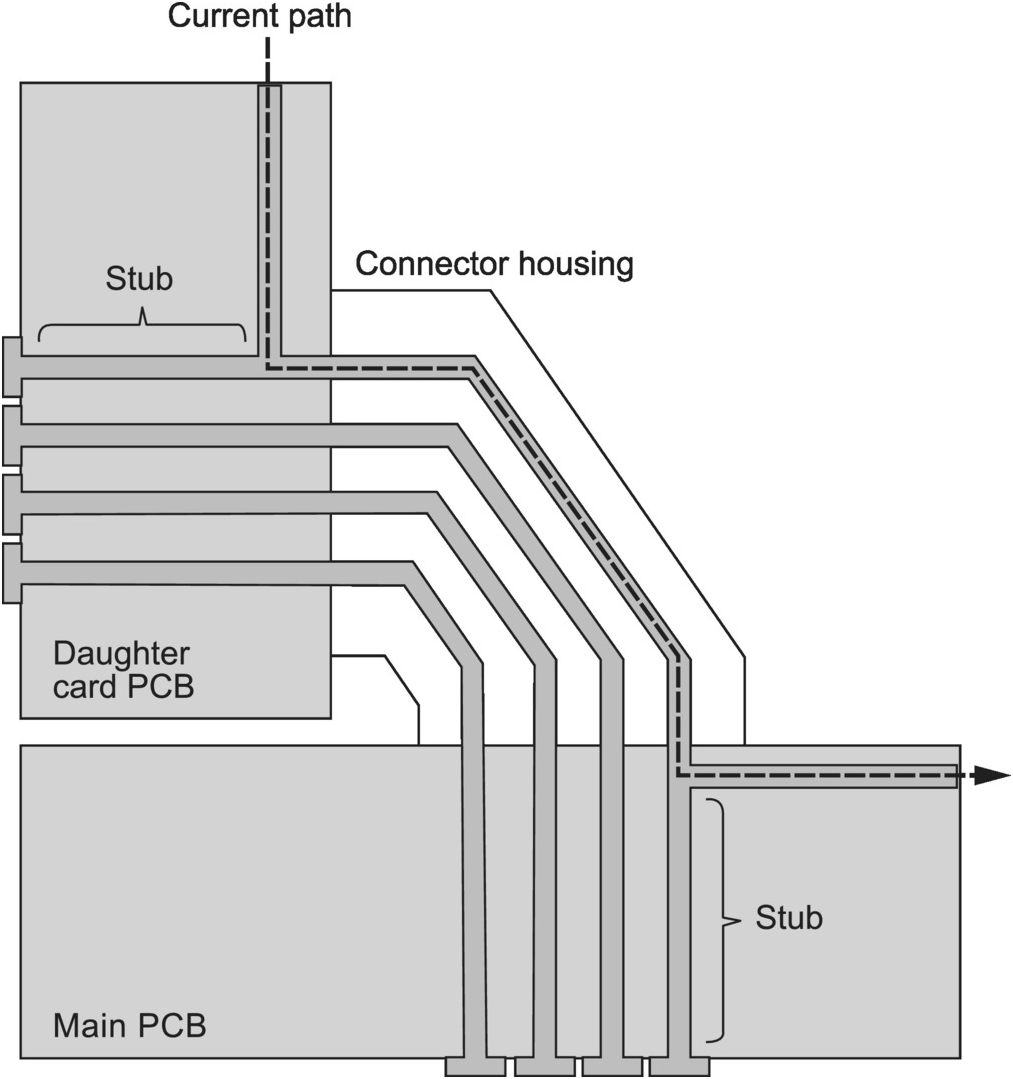

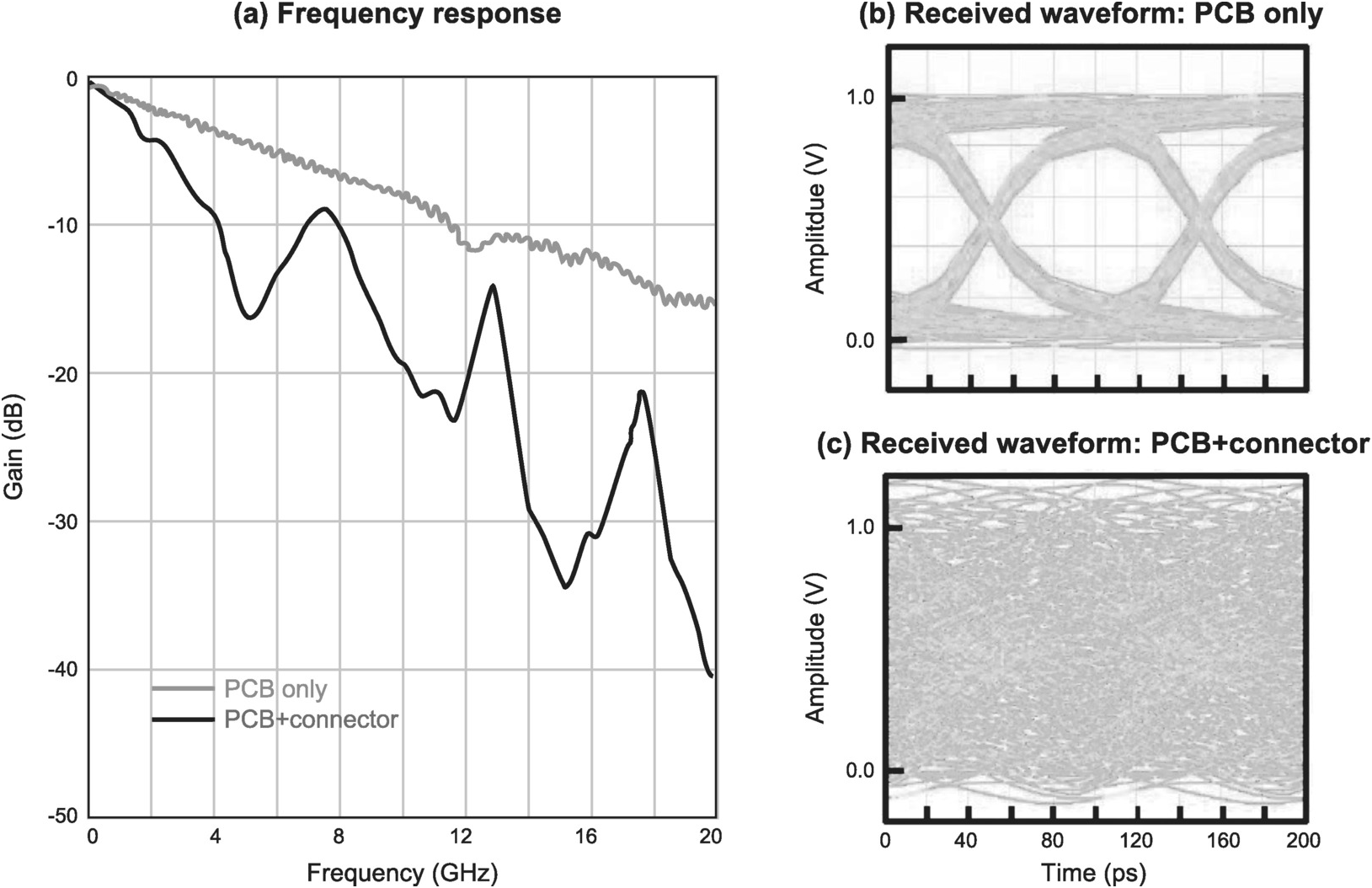

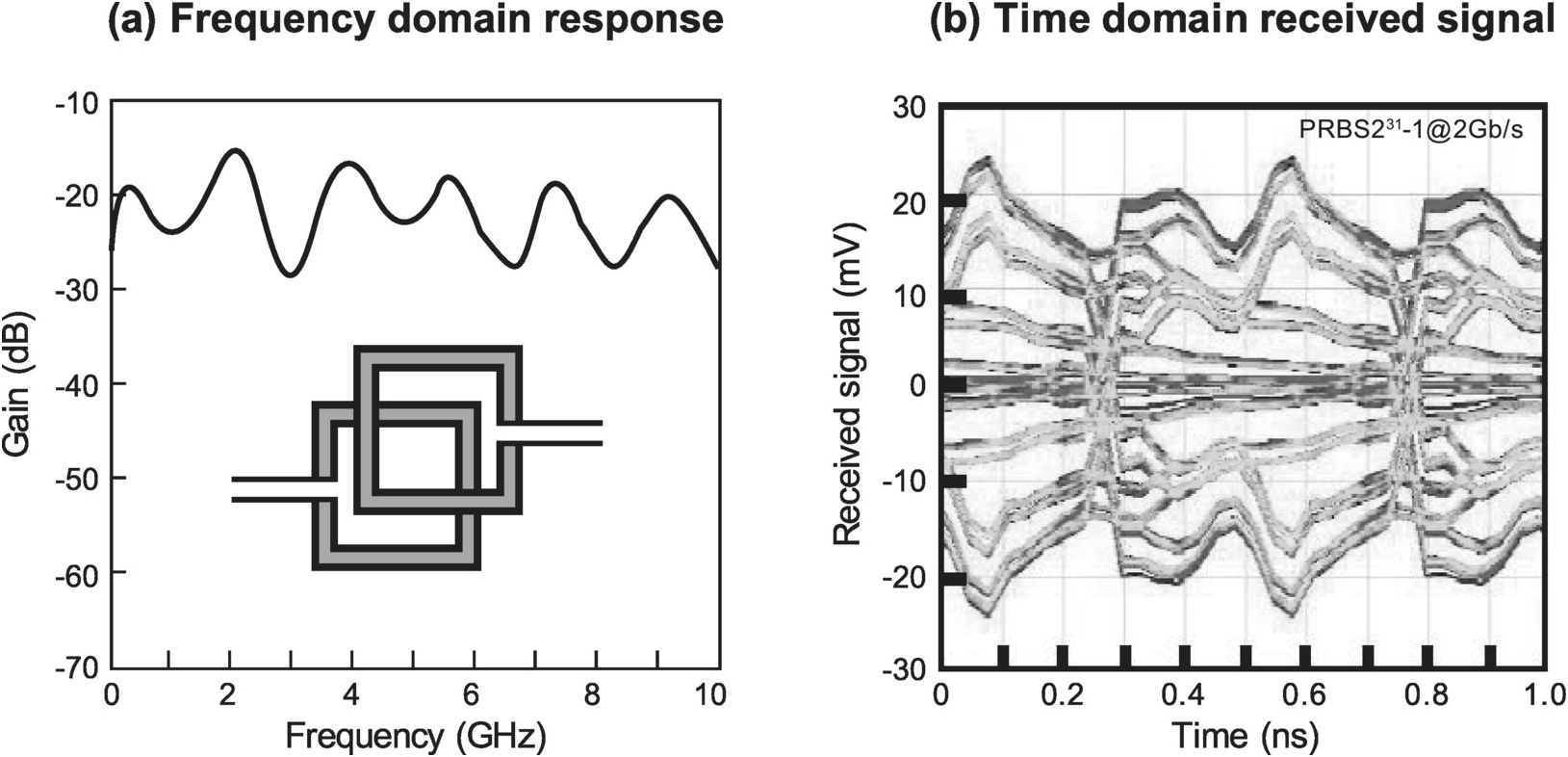

The off-chip physical interconnections of an IC generally consist of bond wires or flip-chip bumps and solder balls, package traces, vias, PCB traces and connector pins, with total distance of more than an order-of-magnitude longer than the size of the IC (Figure 1.15). Consequently, off-chip interconnects have different electrical behavior than on-chip interconnects. As a rule of thumb, when an interconnect has delay that satisfies the following condition, it appears as a transmission line to signal propagation:

where td is the propagation delay of the interconnect, and tr is the edge rate of the signal. Delay of a typical PCB interconnect is around 6 ps/mm, while the typical edge rate of a 1 Gbps signal is around 200 ps. Therefore, a PCB interconnect only needs to be longer than 1.67 mm to appear as a transmission line to a 1 Gbps signal. Hence, typical PCB interconnects in high-performance computing systems that are on the order of a centimeter or more in length behave as transmission lines. Furthermore, due to the combination of high conductivity and sufficiently large surface area, PCB interconnects are generally low-loss transmission lines with relatively low resistive loss and hence low power consumption.

Figure 1.15 An off-chip interconnection in a typical PC memory system.

The approximate electrical behavior of a low-loss transmission line is fully defined by its characteristic impedance Z0 and propagation delay γ, which can be computed as follows:

(1.2)

(1.2)where L0 and C0 are the per unit length inductance and capacitance respectively of the transmission line. In a low-loss transmission line, attenuation of signal amplitude is small. However, if the transmission line Z0 varies along its length, some of the signal energy will be reflected. When that happens, the shape of the received signal in a certain time slot depends not only on the shape of the transmitted signal in that time slot, but also the shape of reflection of the transmitted signal in prior time slots, resulting in what is known as intersymbol interference (ISI). Therefore, impedance variations along a transmission line result in ISI, which degrades integrity of the received signal.

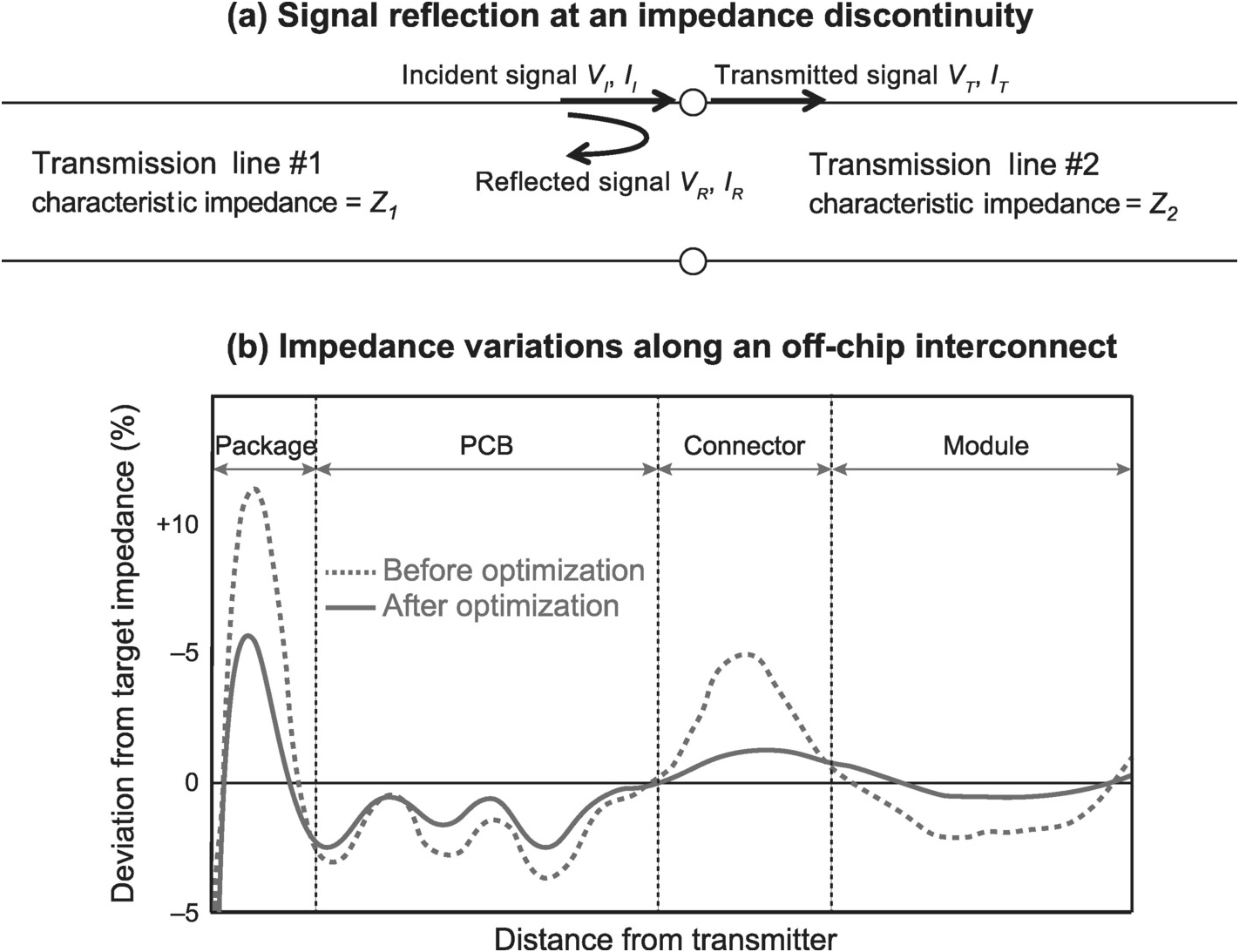

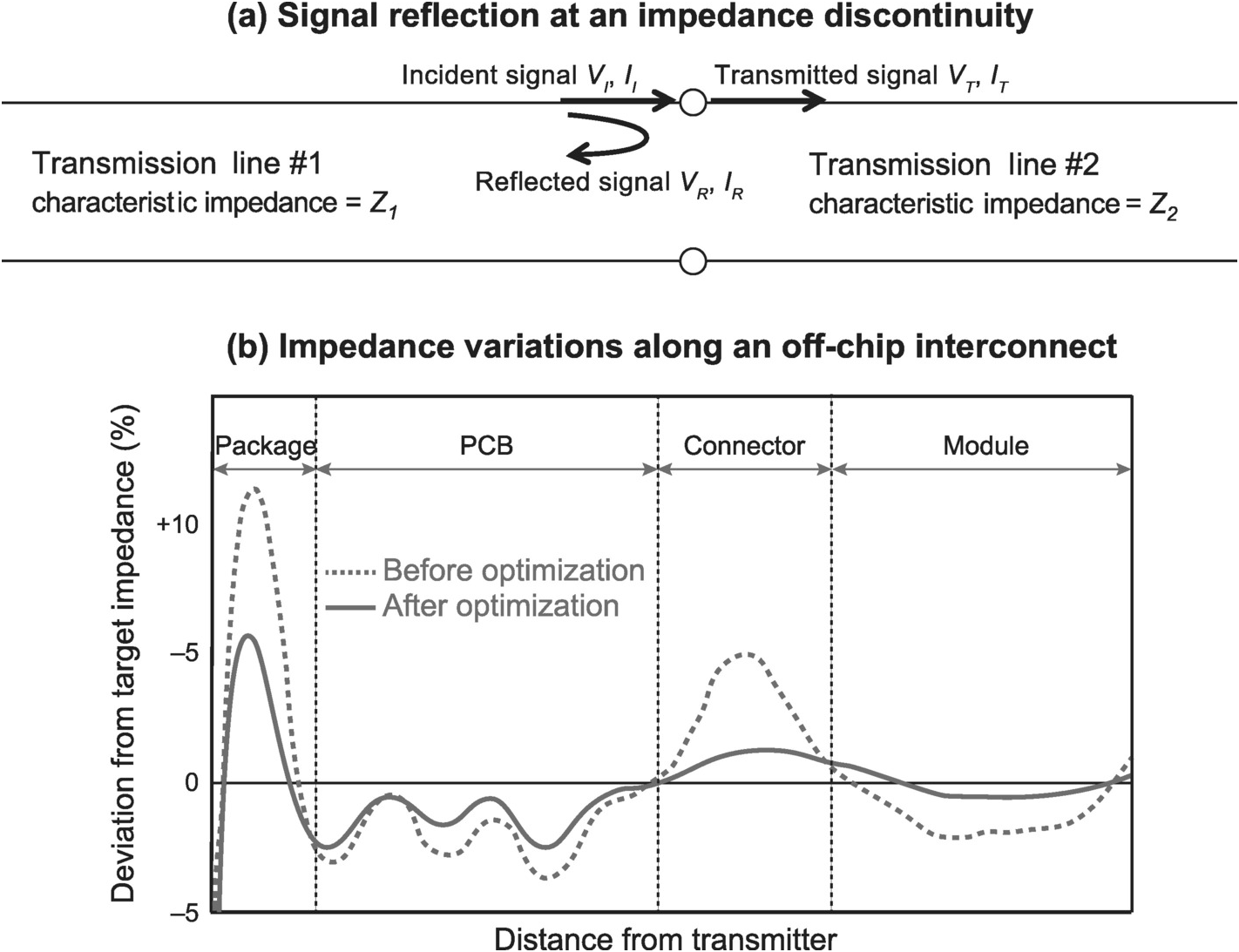

When a voltage step VI arrives at an impedance discontinuity, a voltage step VR is reflected, resulting in a voltage step of VT being transmitted (Figure 1.16a). The voltage steps are related through the following two equations:

where ρ and τ are known as the reflection and transmissoin coefficients, and Z1 and Z2 the characteristic impedance of the transmission line before and after the discotninuity respectively. Therefore, the goal of off-chip interconnect design is to maintain a smooth characteristic impedance profile along its entire length to minimize reflection in order to preserve the integrity of the transmitted signal. Nevertheless, given the complexity of the off-chip interconnect, characteristic impedance variations along its length are unavoidable even with meticulous design optimization (Figure 1.16b).

Figure 1.16 Impedance variations of off-chip interconnects.

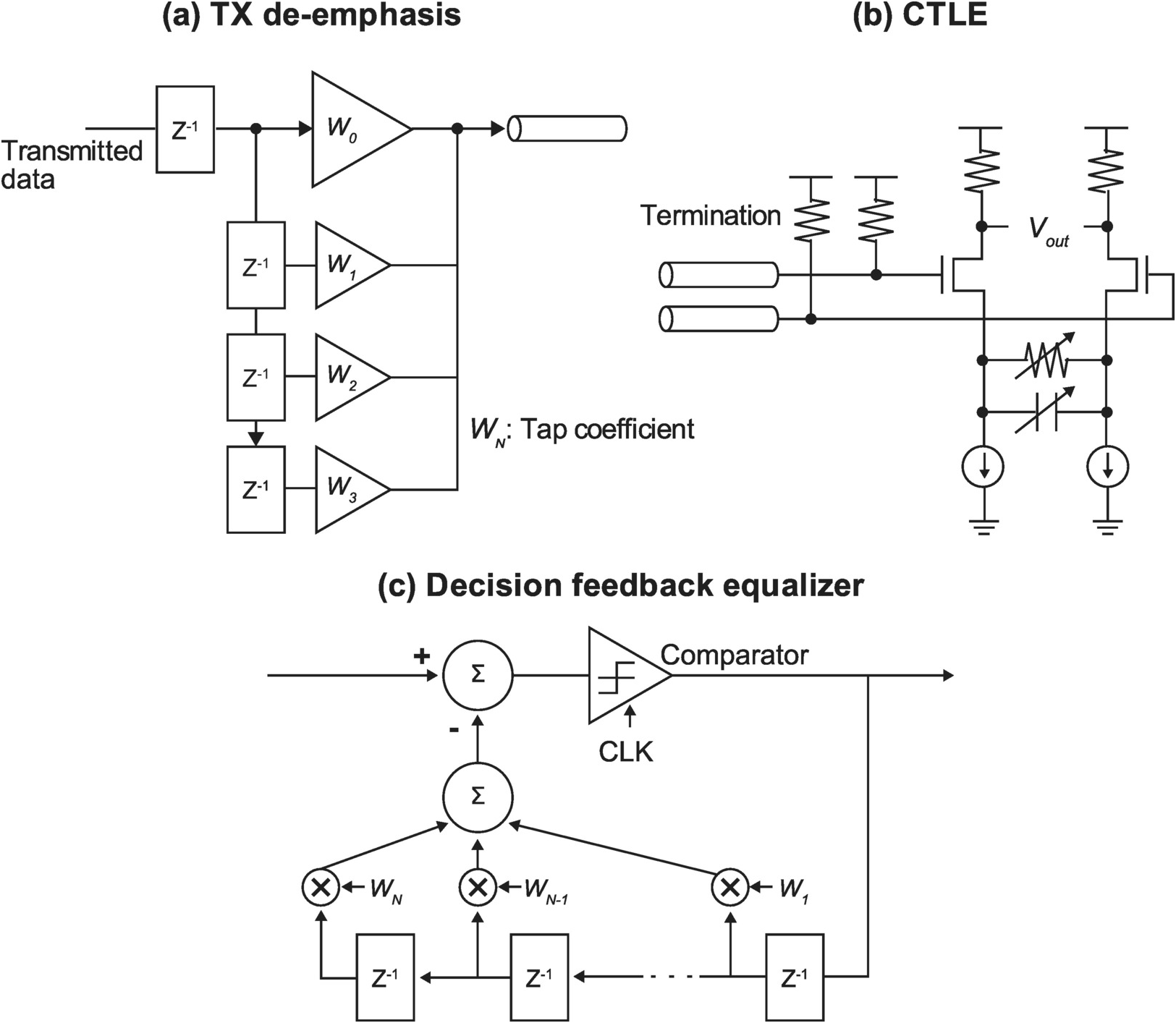

To compensate for the loss in integrity of the transmitted signal due to impedance variations of off-chip interconnects, I/O circuits must be modified accordingly, for example by adding equalization circuits, resulting in increased complexity and power consumption. Furthermore, in general, the driver at the near end of the interconnect has lower impedance while the receiver at the far end higher impedance than the interconnect, representing additional discontinuities. To minimize reflection due to these discontinuities requires adding resistors at the driver and/or receiver to alter their impedances, resulting in additional area, cost, as well as power consumption. Consequently, a more effective way to preserve signal integrity of a low-power IC interface is to minimize the communication distance to limit transmission line effects in order to reduce I/O circuit complexity and power consumption.

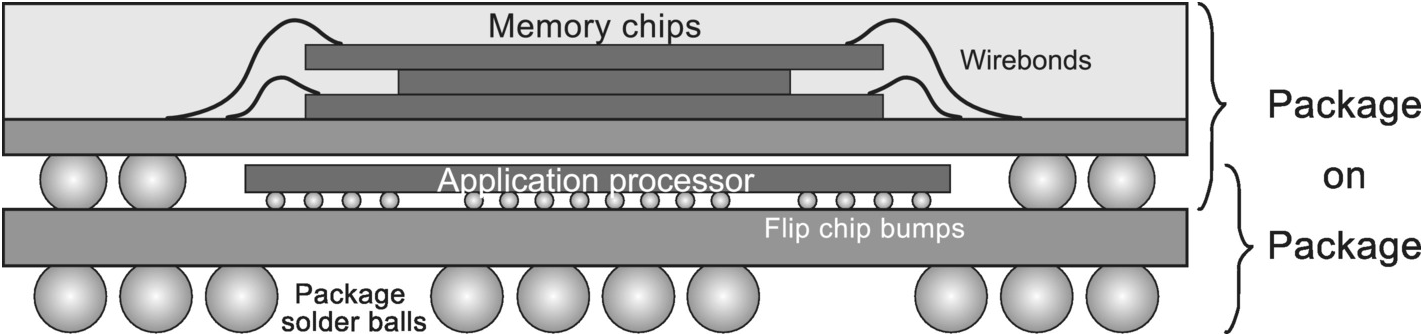

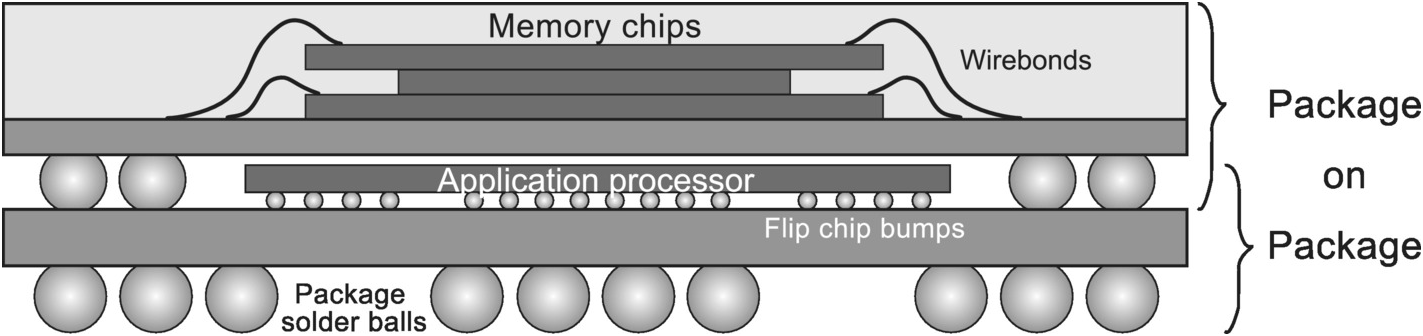

Putting the entire system on a single chip in the form of an SoC will result in the shortest communication distances. However, in practice, there is a limit on how much of the system can be brought on-chip. In addition to the high manufacturing costs of a bigger die, a larger and more complex SoC increases development costs and time to market. Furthermore, an SoC precludes tailoring the manufacturing process toward individual functions to minimize manufacturing costs. For instance, logic and memory chips are manufactured in substantially different processes for economic reasons. Therefore, putting the two functions on the same chip means the manufacturing process would be suboptimal for one or both functions, leading to suboptimal costs and performance. An alternate solution to minimize communication distance that is compatible with a multichip system is a system-in-package (SiP). The best example of an SiP is the memory subsystem of a smartphone implemented in a package-on-package (PoP), where a packaged memory chip is stacked on top of the application processor (AP) mounted on a second package substrate, thus eliminating the PCB connection that exists when the two chips are mounted separately on the board (Figure 1.17).

Figure 1.17 A package-on-package in a smartphone.

In the smartphone PoP, the AP and memory chips are connected indirectly through bond wires, solder bumps, and package substrate traces. In a later section, we will introduce a wireless chip interface that allows direct connection between multiple chips, thereby reducing the communication distance to a minimum.

1.2.4 Energy-Efficient IC

Around 2005, the technology driver for the IC industry changed again, from the PC to the smartphone, which demands continuous, aggressive downsizing. Minimum silicon line width has continued to shrink from 0.13 µm to 28 nm, and down to 7 nm, for example, for the A12 application processor in the iPhone XS released in 2018. Meanwhile, battery has become a severe performance limiter, since it occupies a large percentage of both the weight and size of a smartphone. Furthermore, the perceived performance of the device is greatly affected by how often the battery needs to be recharged, and hence how much energy its components consume. As a result, low-energy has become a key IC design objective.

With the smartphone market growth slowing, new technology drivers are emerging. Two of them are undoubtedly data center and IoT, each of which presents different design challenges than the smartphone. Servers and supercomputers for the data center drive the advance in power efficiency. Furthermore, given their tremendous power consumption, the heat they generate becomes a limiting factor on performance, while cooling becomes another large adder to operating costs. On the other hand, IoT, which includes wearables and implantables together with smartphones, demands aggressive reduction in energy consumption. Some of their applications require very small form factor, which significantly limits battery capacity.

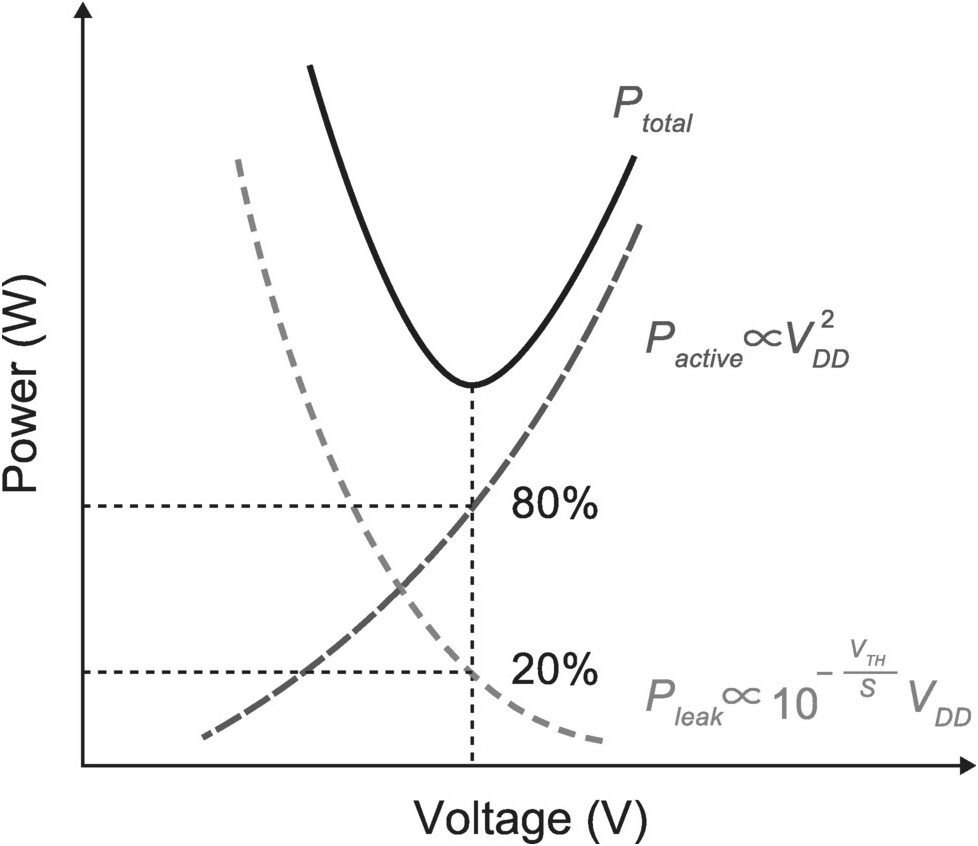

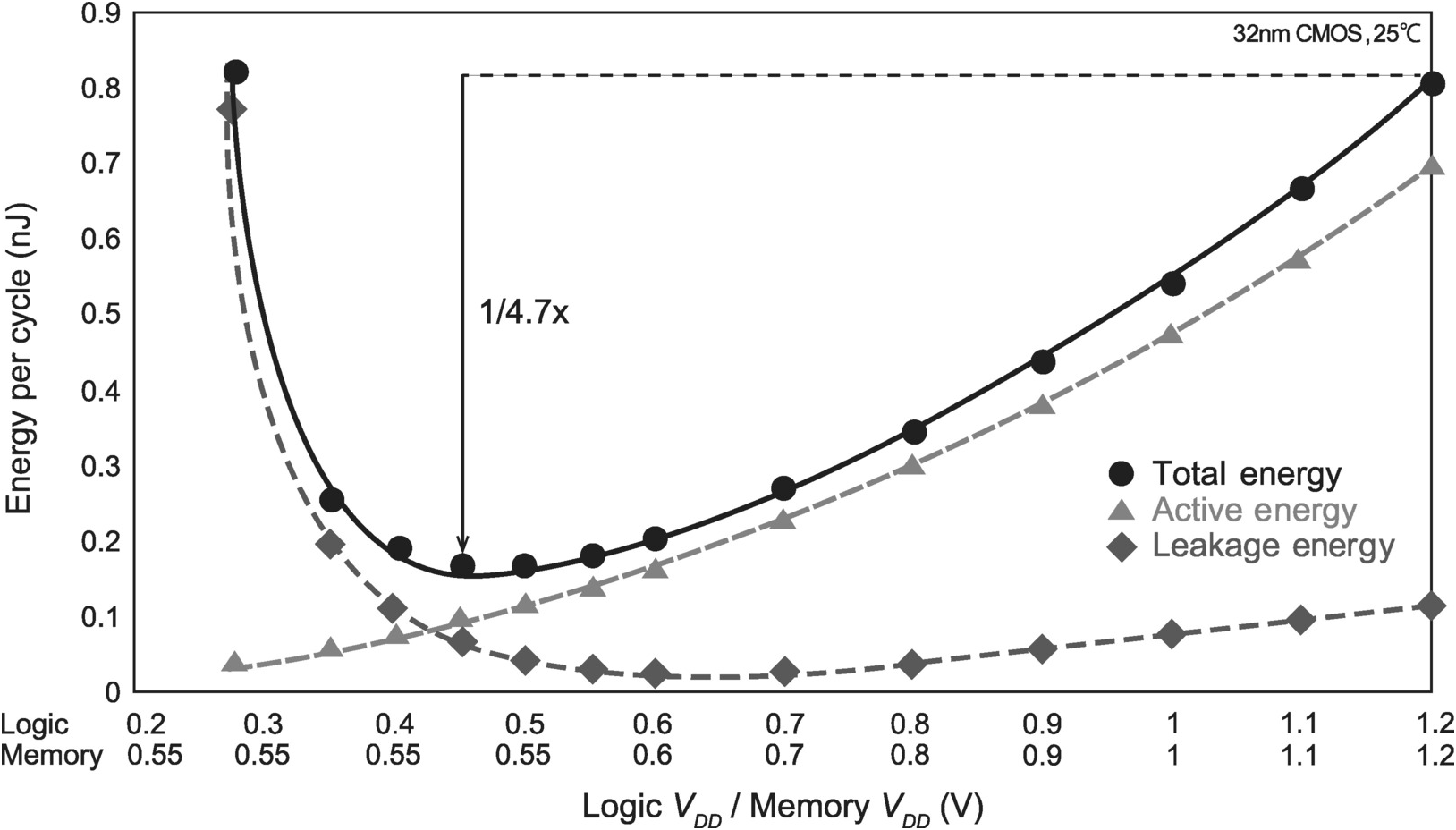

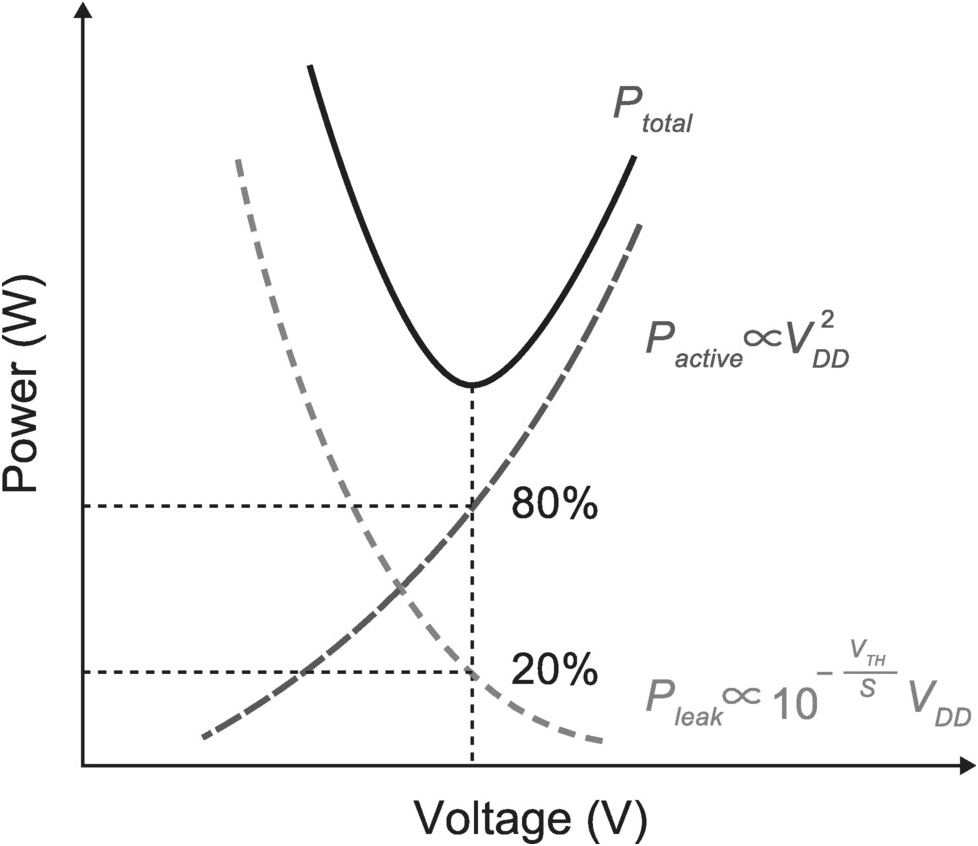

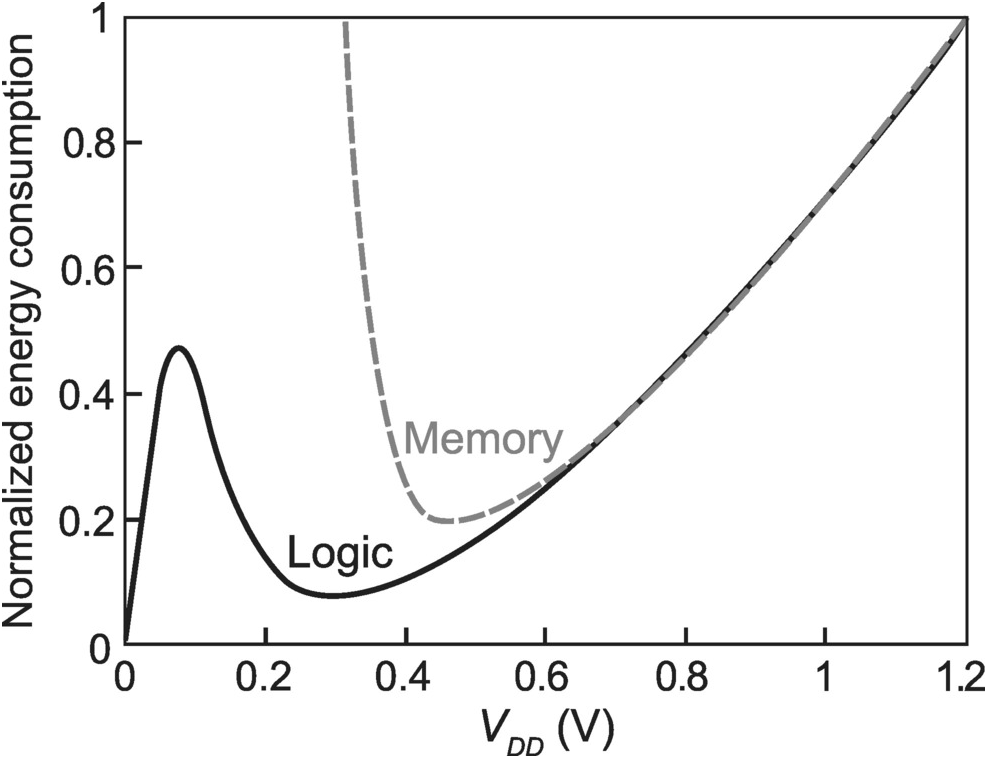

Power and energy consumption are interrelated. But while power P = αCVDD2 f is a linear function of switching frequency f and capacitance C, and a quadratic function of voltage VDD, energy E = CVDD2 varies only with C and VDD. (α is the switching probability). Reducing VDD is therefore an effective way to reduce both power and energy consumption. In practice, when VDD is initially lowered, power and energy will indeed decrease proportionally. But when VDD drops below a certain value, power and energy will reverse course and rise (Figure 1.18). This is due to rising leakage current. When VDD is lowered, VTH needs to be lowered accordingly to avoid performance loss. But when VTH is lowered, leakage current rises exponentially. Consequently, leakage current must be taken into account when considering overall power and energy efficiency. In the case of a metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET), transistor switching is controlled by the electric field between the gate and the substrate. This electric field is like the packing attached to the handle of a water faucet that controls the water flow. If this packing is weakened, the faucet will leak. In the MOS transistor, when the gate length is reduced without a corresponding reduction in oxide thickness, the electric field controlling switching is weakened, resulting in increased leakage. Therefore, as we lower VDD to reduce power and energy consumption, we must implement countermeasures to rising leakage, such as the material and structural changes described in Section 1.1.2.4 and Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.18 IC power as a function of VDD [Reference Kuroda3].

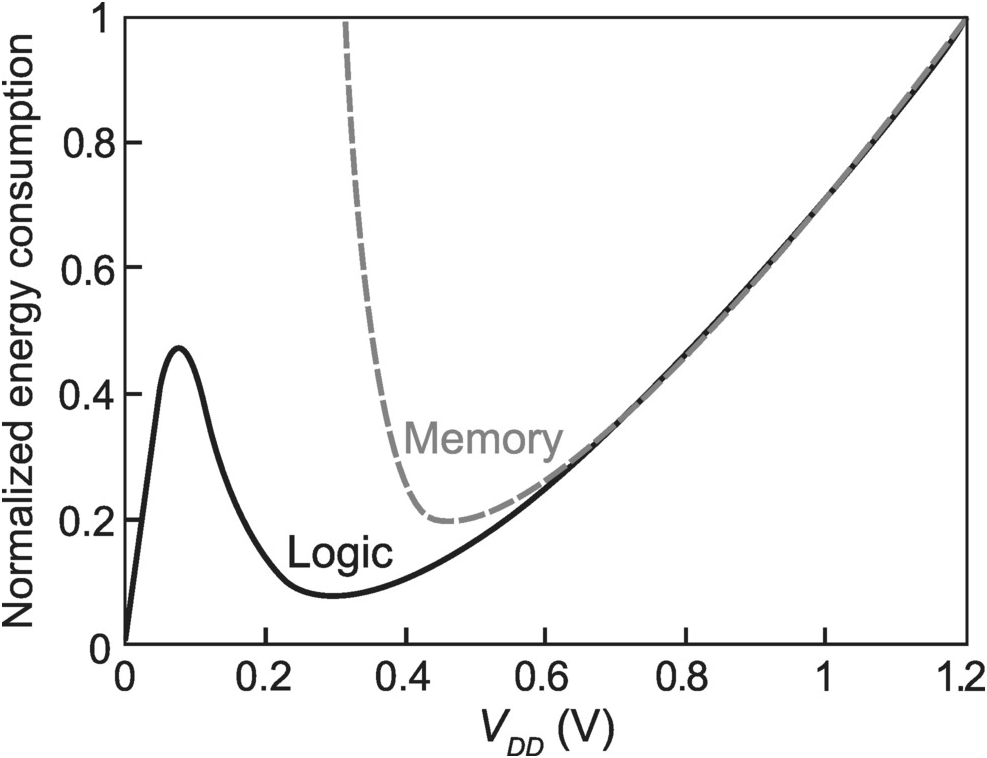

Given that the overall power consumption of a chip is the sum of its active power Pactive and leakage power Pleak, it is a function of how active the chip is. A logic chip that spends a lot of time performing active computation has a larger proportion of active power than a memory chip that is active only during a memory access in a localized area and during management operations. As a result, the optimal VDD and VTH for the lowest power and energy are different between logic and memory chips (Figure 1.19). It is therefore necessary to understand the operation of a chip when we design for low power and low energy.

Figure 1.19 Logic and memory energy consumption as a function of supply voltage.

As an illustration, from experience, lowest overall power is achieved when active and leakage power are around 80% and 20% respectively of overall processor power. For example, both Intel’s Pentium4 and IBM’s Power5 had about 20% leakage power.

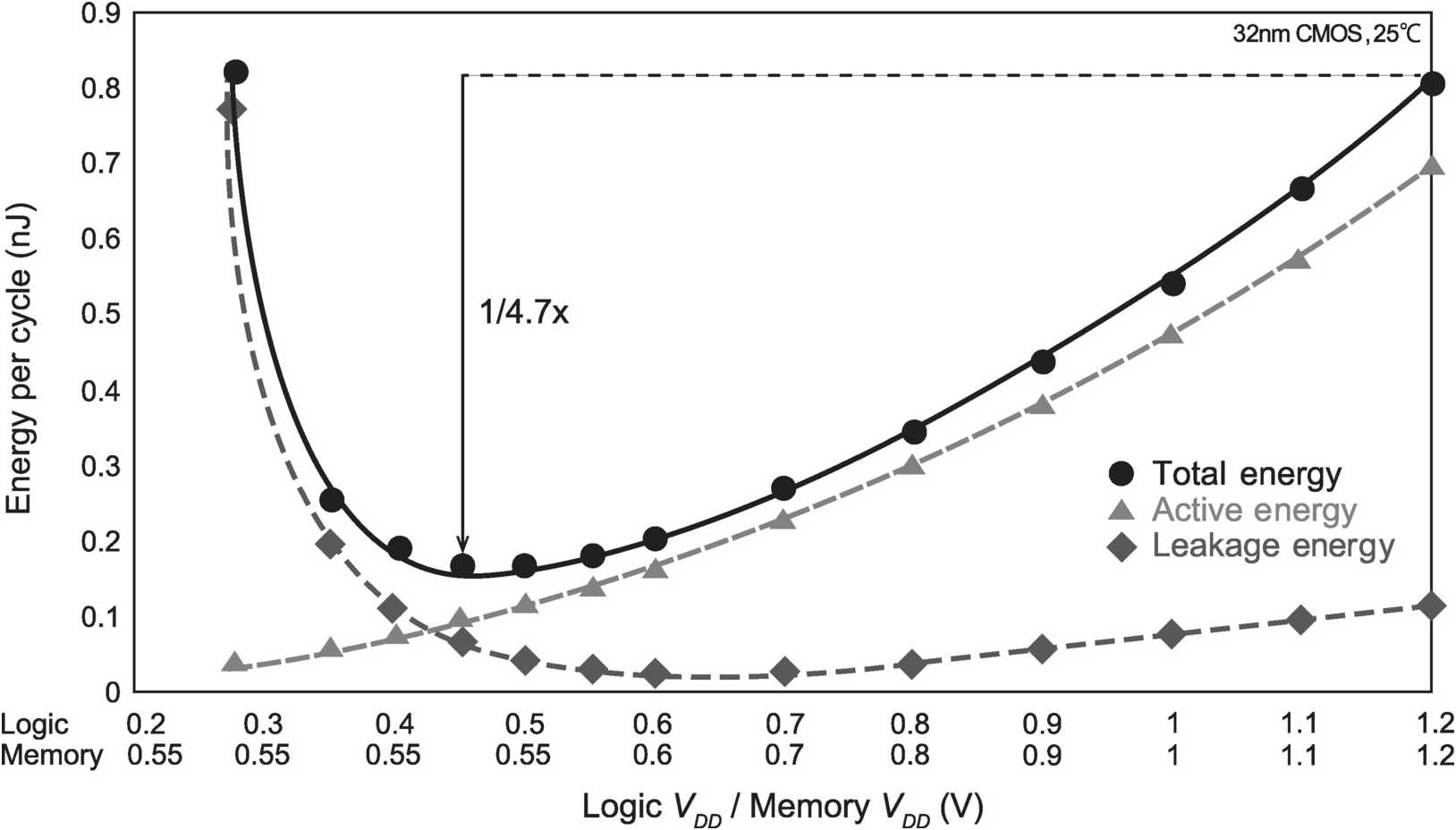

Figure 1.20 depicts the energy consumption as a function of logic and memory VDD for an example processor in a 32nm CMOS process [Reference De15]. Based on these data, overall energy is minimized at a logic VDD of around 0.45 V. The Low-Power Electronics Association & Project (LEAP) in Japan has successfully developed a new device known as silicon on thin buried oxide (SOTB) that can operate down to 0.4 V [Reference Ishigaki, Tsuchiya, Morita, Sugii, Kimura and Swart16], which makes it possible to operate the processor at its optimal VDD for low power.

Figure 1.20 Optimized VDD for minimum total energy.

1.2.5 Energy-Efficient Computing Trends

With SOTB, a low voltage of 0.4 V has been achieved. Yet, there is headroom for further reduction. For logic circuits to function correctly, the output of a CMOS invertor must be able to achieve full swing up to its supply voltage of VDD to drive the invertor in the next stage. Theoretically, VDD can be lowered to 0.036 V before the invertor gain drops below 1. Therefore, VDD can be lowered by another order of magnitude. Since energy is a quadratic function of voltage, there is room to reduce energy further by two orders of magnitude.

Nevertheless, in practice, a lower VDD is difficult to achieve. When VDD is lowered further, gate operation becomes unstable. For example, since the on and off (leakage) currents of the gate inside a flip-flop go against each other, when the on-to-off current ratio becomes too small, the circuit will stop functioning. It is therefore necessary to maintain a certain balance between on and off currents to ensure proper operation. Furthermore, increase in leakage current resulting from lower voltage as discussed in the previous section will need to be addressed. As a result, various research efforts are under way to develop steep slope devices with more pronounced subthreshold characteristics [Reference Topaloglu and Wong17].

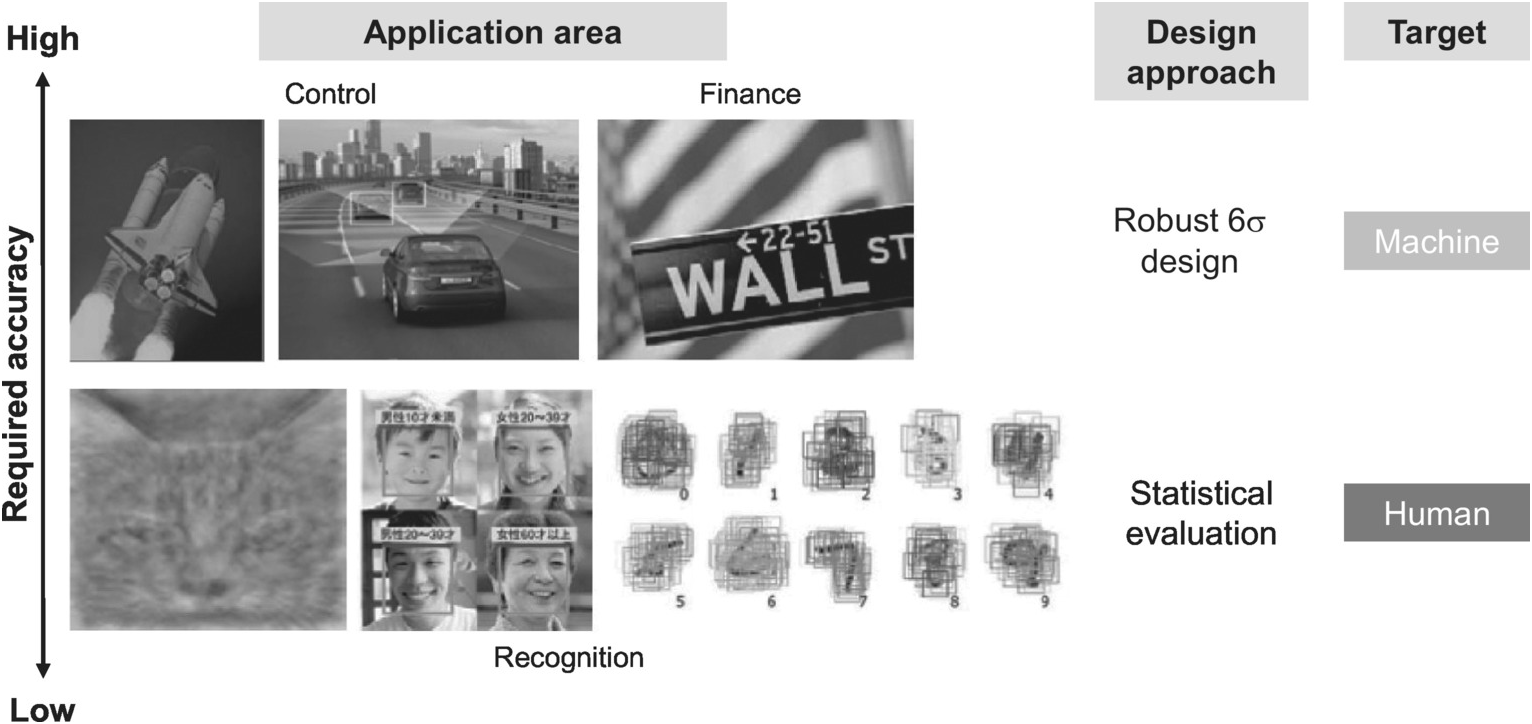

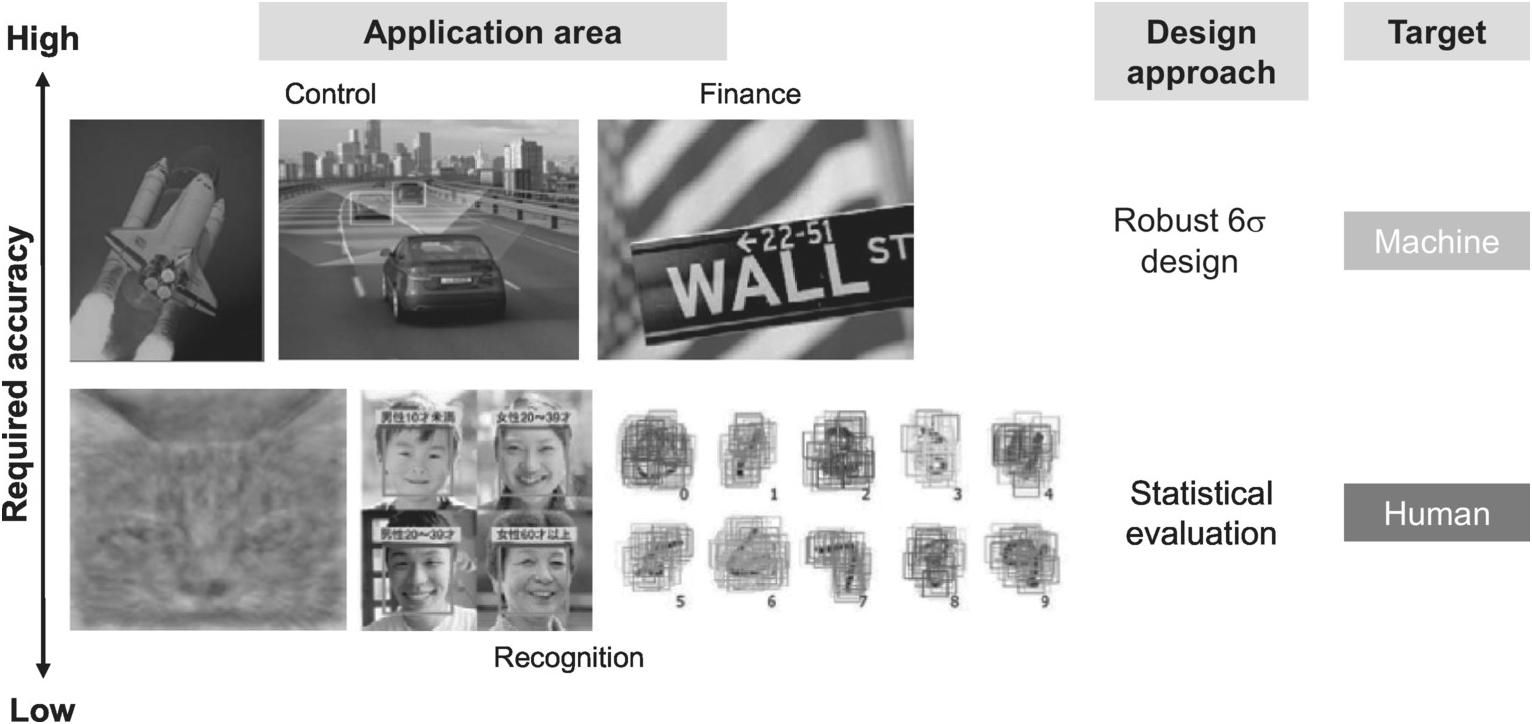

In addition, as voltage is lowered further, manufacturing variations will surface as another challenge. When VDD approaches the threshold voltage, small changes in VTH will lead to large changes in current, resulting in large variations in circuit speed that cannot be ignored. As a result, synchronous circuit designs may not be possible anymore [Reference Fant18–Reference Maruyama, Hamada and Kuorda19]. One solution is to allow certain amount of functional errors, as long as the probability of an error is sufficiently low. In other words, the chip will be functionally correct most of the time, but not 100% of the time. It is a statistical approach.

Of course, this is not acceptable for mission critical applications such as airplane and automotive navigation, as well as financial transaction computation. On the other hand, there are applications where small errors do not alter the outcome, such as image and face recognition (Figure 1.21).

Figure 1.21 Statistical system design approach and its application.

The statistical system design approach is compatible with some of the trending new applications such as image recognition and artificial intelligence. A hot area of technology development in image recognition and artificial intelligence is machine learning, where a deep neural network (DNN) is used to create an artificial intelligence system. The excitement in DNN research started when one such network achieved a breakthrough in dramatically reducing the error rate from 25% to 16% in image recognition in the 2012 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Technology bellwethers such as Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Baidu are all competing to deliver the next breakthrough in machine learning, in addition to startups funded by billions of dollars in venture capital [Reference Rowley20]. The technology is rooted in mimicking the algorithms humans use for image recognition. Since human actions are based on statistical and probability analysis, a statistical design approach can be a good fit for developing energy-efficient machine learning systems.

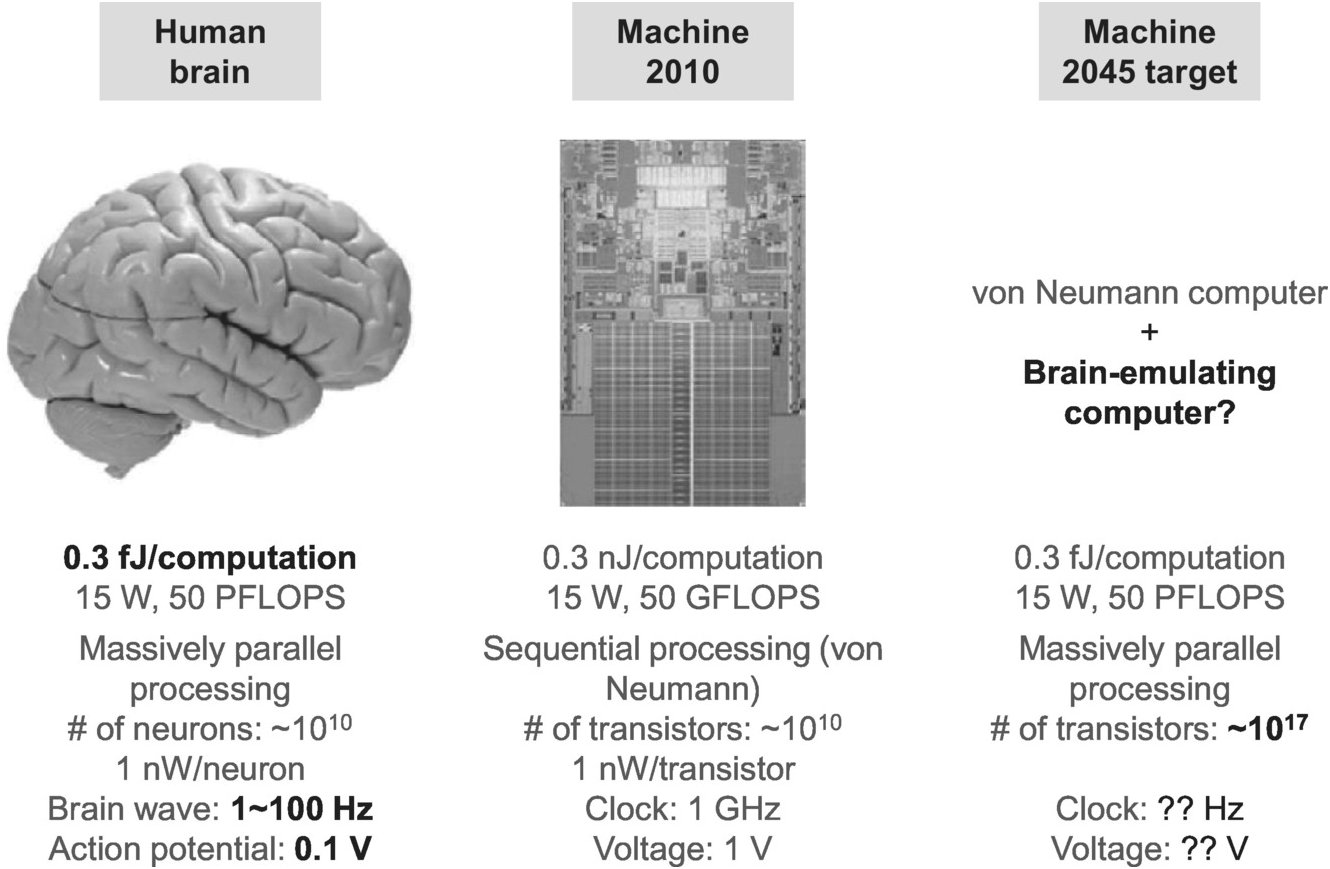

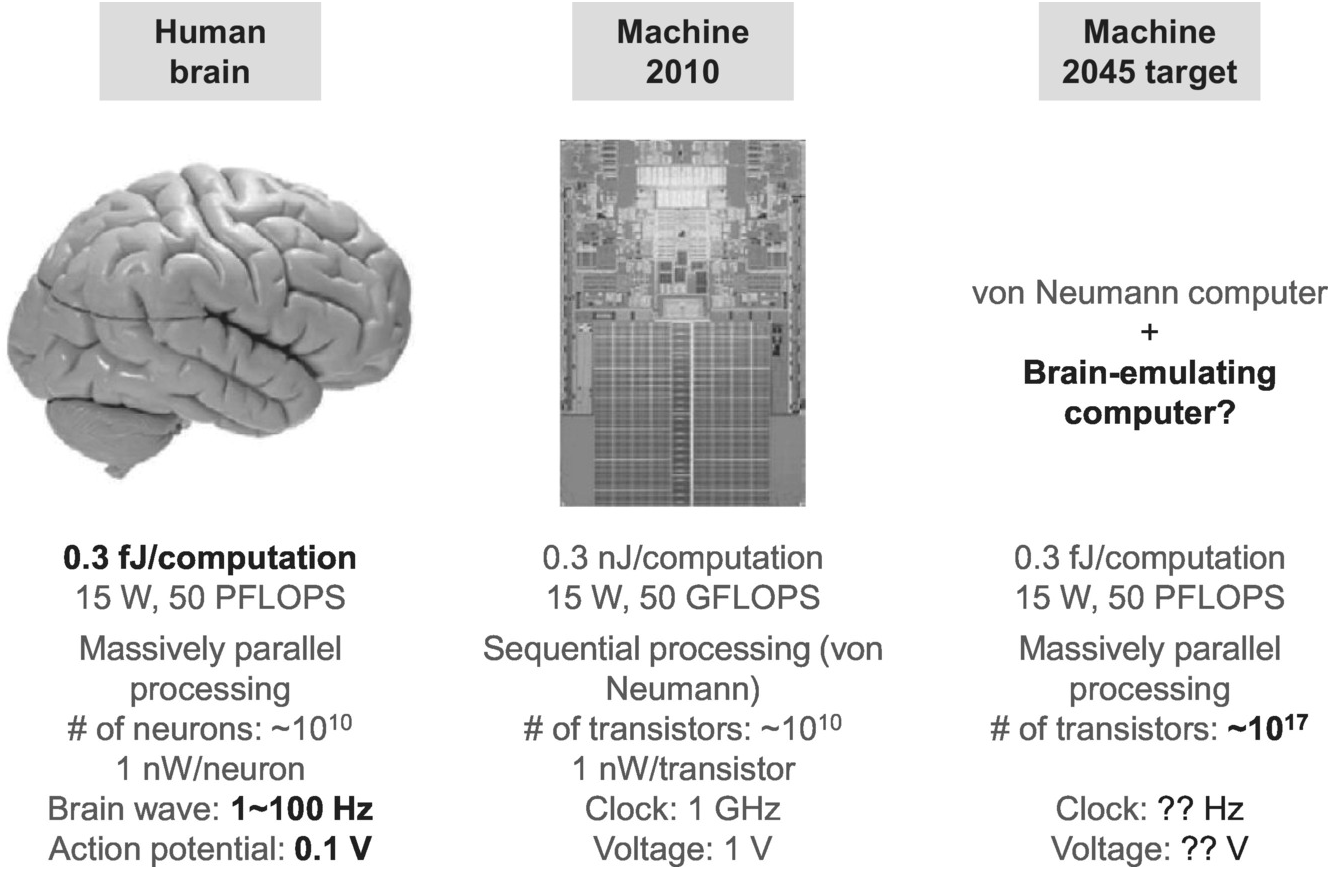

To see how much we need to improve power efficiency for machine learning applications, the natural benchmark for comparison is the human brain. The human brain consumes about 0.3 fJ of energy per computation, corresponding to a power efficiency of 15 W/50 PFLOPS. By contrast, Intel processors from 2010 consume about 0.3 nJ of energy per computation, resulting in an efficiency of 15 W/50 GFLOPS (Figure 1.22). In other words, the human brain is six orders of magnitude more power efficient. It will take a lot of effort, including introducing the statistical system design approach, running the machine nonstop to gain an advantage over the human brain, which needs to sleep every day, and so forth, in order to close this gap.

Figure 1.22 Power efficiency comparison: machine vs. human.

Another trend in energy-efficient computing is distributed computing. At the system level, the trend is to distribute processing over many physically small processing elements that are connected through short-range wireless communication so no one element has to work very hard. Early development efforts include Ubiquitous Computing (PARC/Weiser), Things That Think (MIT), Disappearing Computer (EU), Invisible Computing (Microsoft), Pervasive Computing (IBM), Paintable Computing (MIT), and Pushpin Computing (MIT). The proliferation of IoT can be considered an implementation of distributed computing at a more global level.

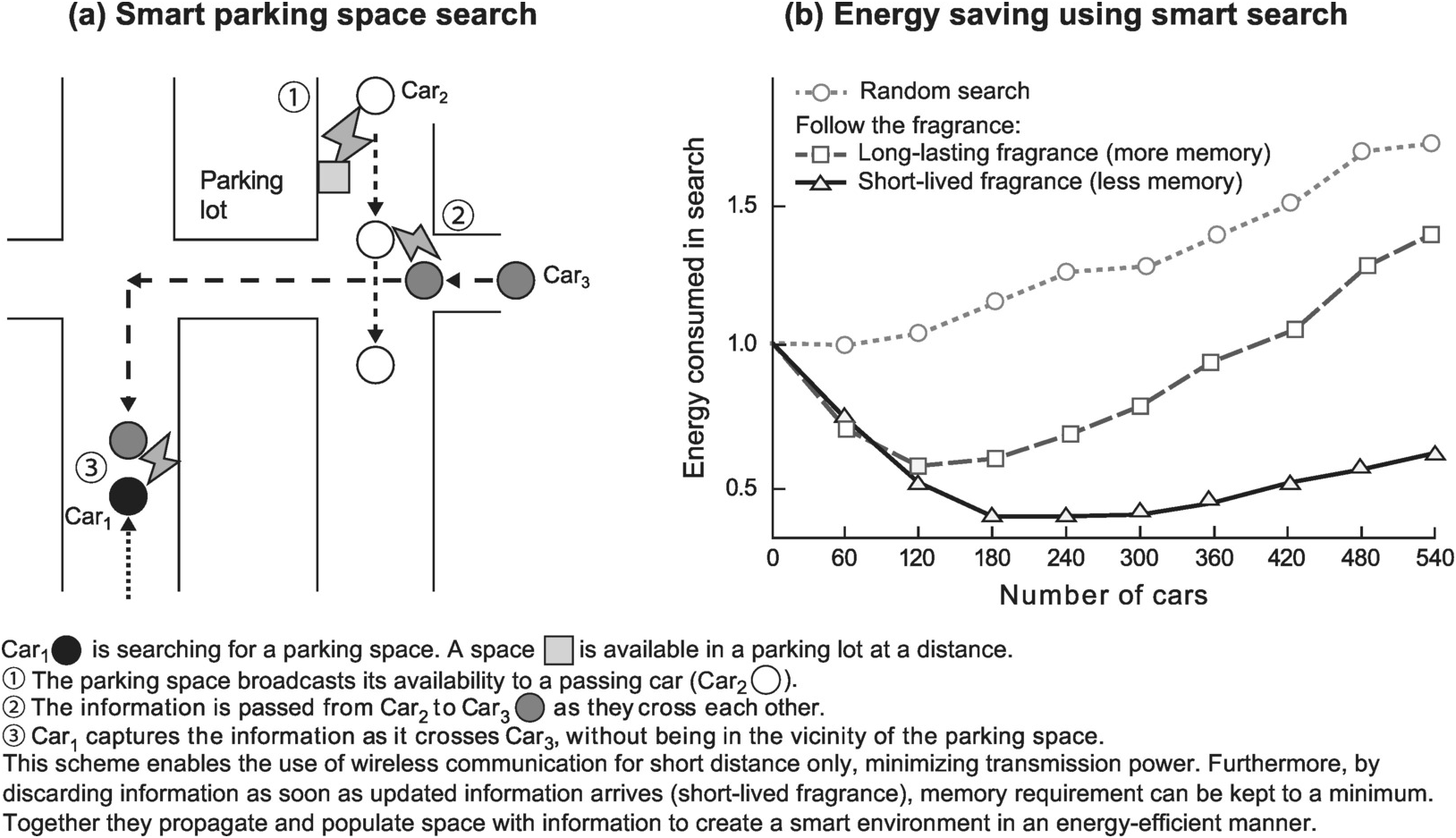

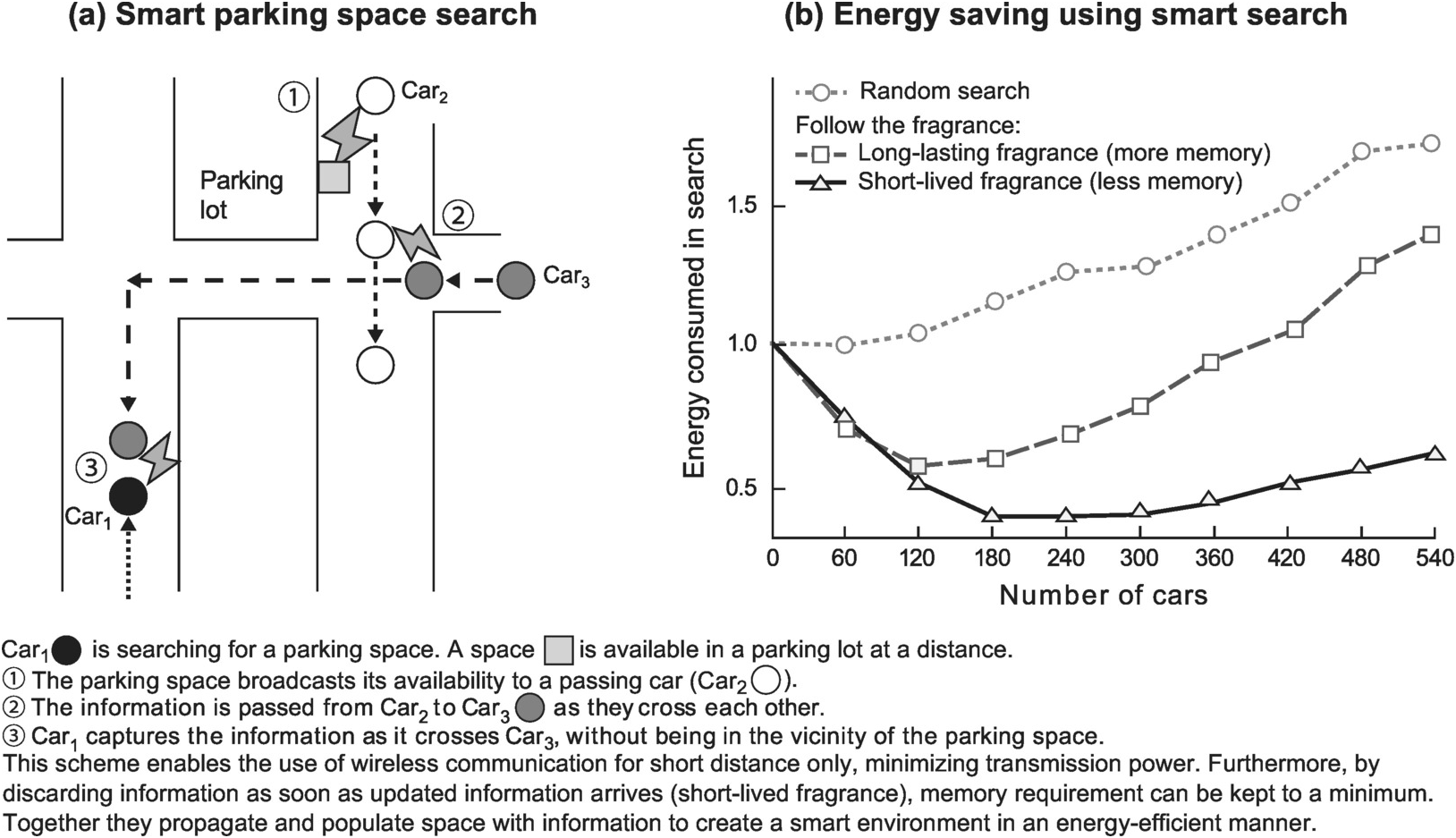

Figure 1.23 depicts an example of distributed computing and its benefits. It illustrates how the problem of searching for a parking space can be solved efficiently with short-range wireless communication and small capacity memory. First, a parking space broadcasts its availability to a passing car (Car3). Then the information is passed from this car to another (Car2) when they cross each other, and the process continues. A car (Car1) searching for a space can capture this information as it crosses Car2 without being in the vicinity of the parking space to directly receive the broadcast information. This is akin to the spread of fragrance, where locating the parking space is like tracing the fragrance back to its origin. The “fragrance” together with the group of cars that spread it makes the environment intelligent, or smart, to use the buzzword of the IoT era. With this smart environment, only short-range communication is required. Therefore, the amount of energy needed to locate the parking space can be dramatically reduced compared to random search using the traditional, centralized processing approach, as illustrated in Figure 1.23b.

Figure 1.23 Using “fragrance” to create a smart environment.

1.2.6 Closing Thoughts

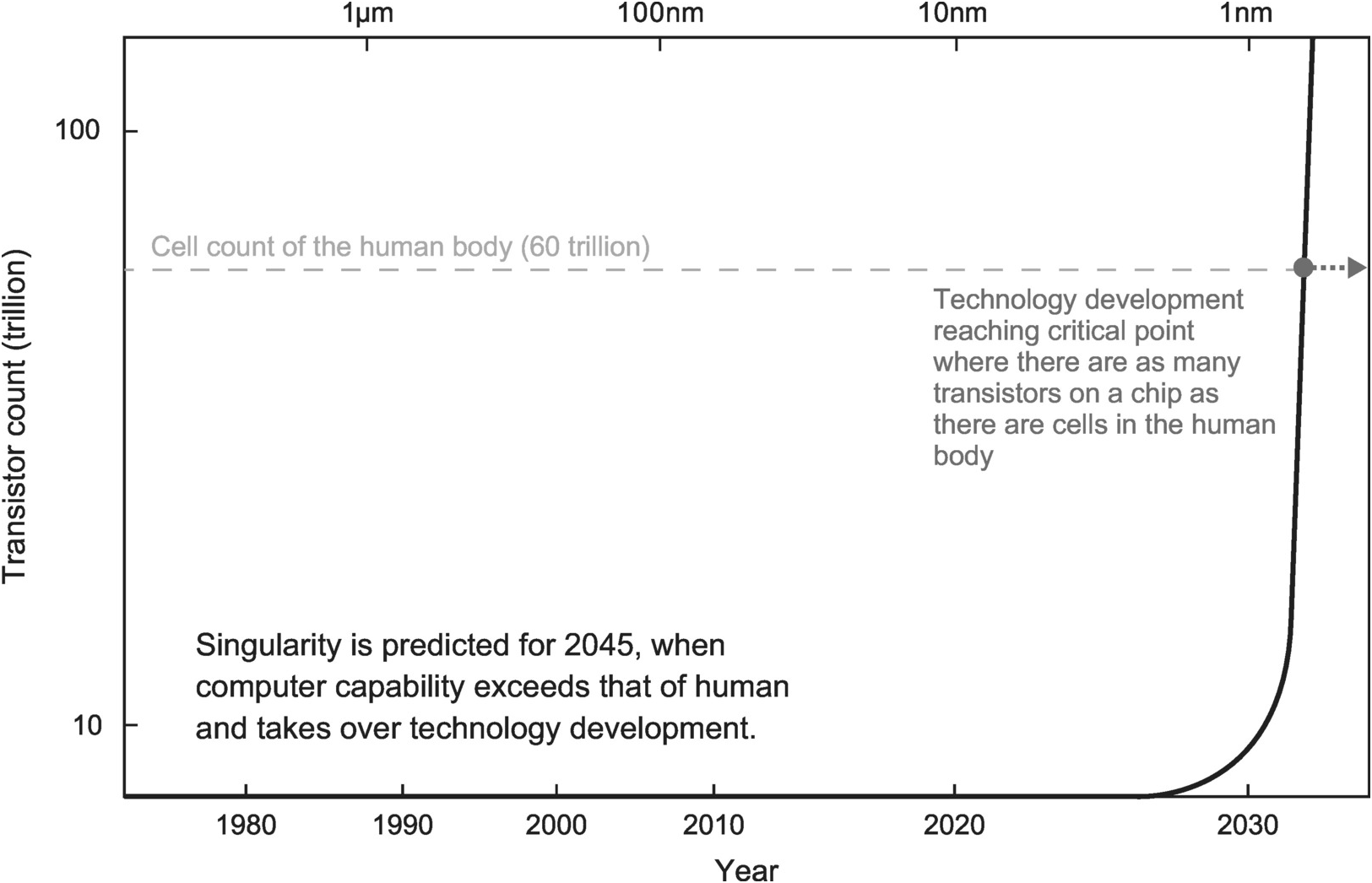

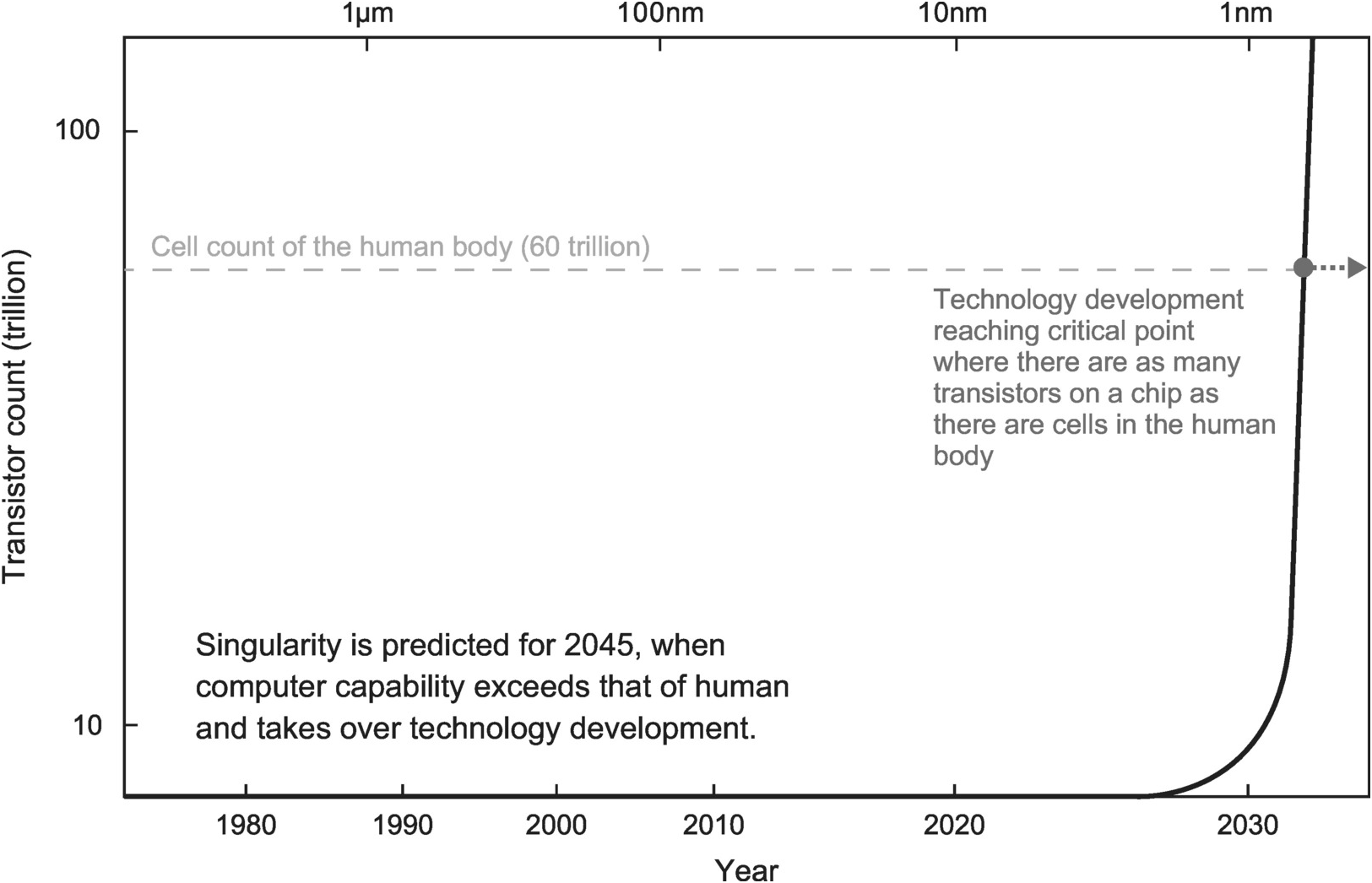

Low-power and energy-efficient designs have allowed IC to continue to scale. Using a 10 nm process, it is now possible to put 100 million transistors on 1 mm2 of silicon [Reference Tyson21], resulting in 0.1 trillion transistors on a 1,000 mm2 chip. While still two orders of magnitude away, the transistor count is starting to approach the 60 trillion cell count of the human body (Figure 1.24). When the chip transistor count finally crosses over the human body cell count, IC development may become dominated by innovative application of the large quantity of transistors made available through advance in power and energy efficiency to achieve the next level of enrichment of our life.

Figure 1.24 Critical point in IC technology development [Reference Kuroda1].

1.3 Evolution from 2D to 3D Integration

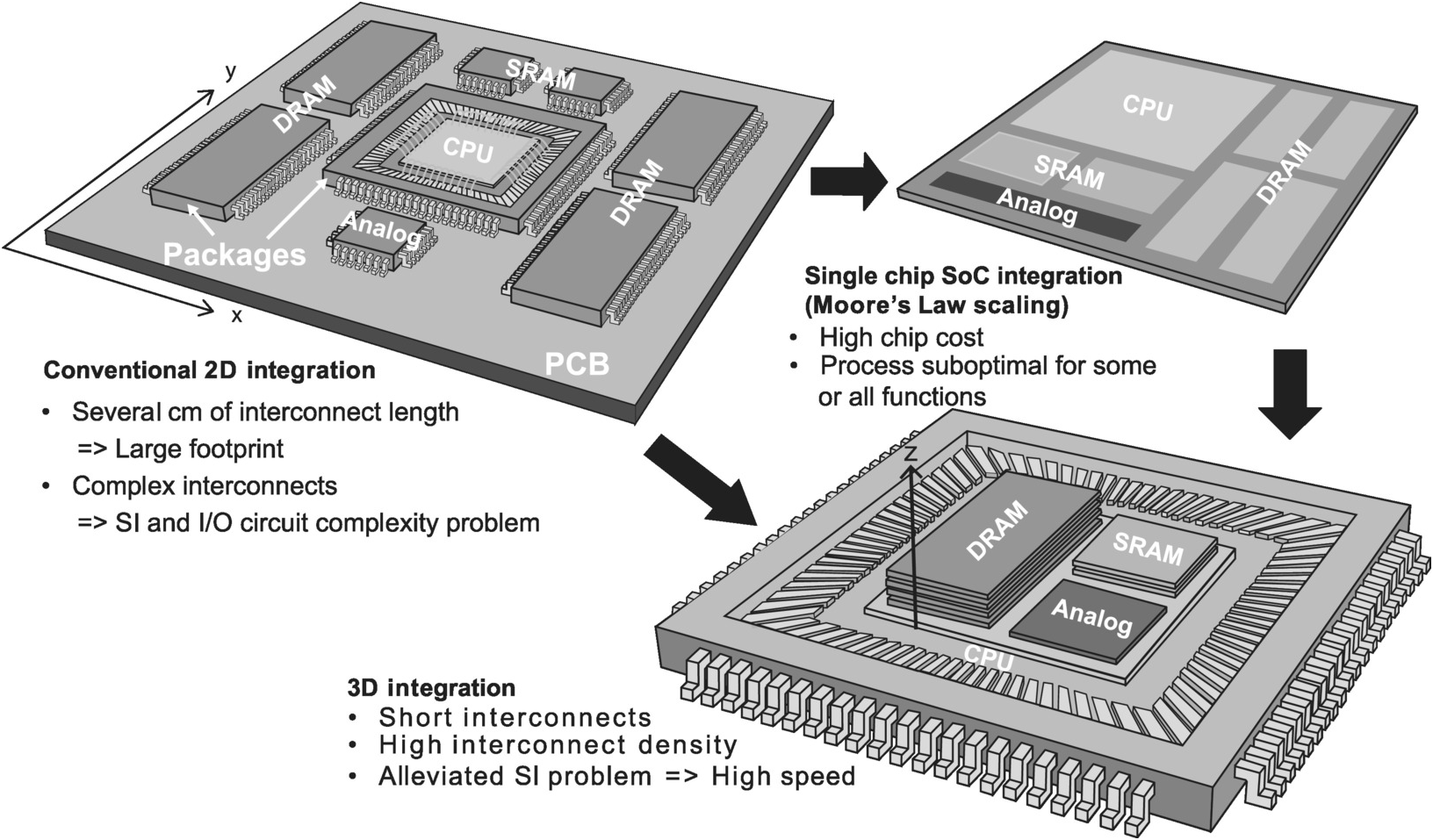

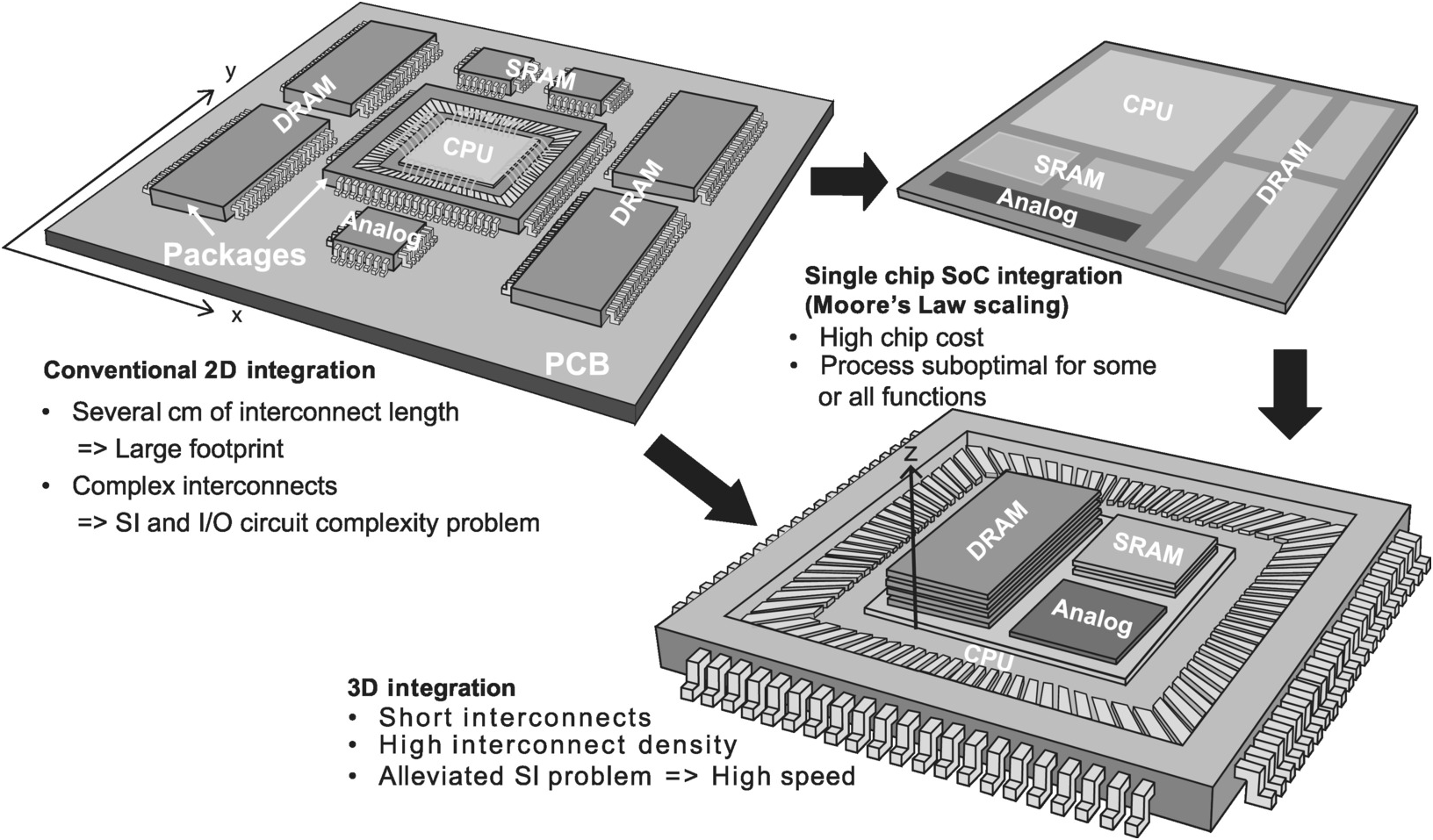

1.3.1 Motivation for 3D Integration

IC chips and other semiconductors are generally packaged and mounted individually on a PCB to build a computer system. Since the individual components are mounted on a 2D surface and connected primarily through traces running in the x- and y-direction (plus vertical vias), this is known as 2D integration. However, as discussed in Section 1.2.3, this complicated off-chip interconnect structure can result in signal integrity (SI) problems due to transmission line effects, which lead to more complex I/O circuit design and higher power. To circumvent these SI problems, 3D integration is adopted where chips are placed on top of each other vertically and connected using primarily interconnects in the z-direction to minimize the communication distance between chips (Figure 1.25). Moreover, stacking chips on top of each other instead of spreading them across a 2D surface minimizes package footprint, which is critical for applications with limited board area such as mobile. This is exemplified by the use of PoP in a smartphone as introduced in Section 1.2.3. But in recent years, a new driver of 3D integration has emerged in the form of More than Moore. As the name suggests, this is an effort to offer more performance than what Moore’s law delivers.

Figure 1.25 From 2D to 3D integration.

As explained in Section 1.1, we can no longer achieve IC performance increase through Moore’s law scaling without having to improve power efficiency. Furthermore, around the 28 nm process node, manufacturing cost per transistor started to rise. In addition, nonrecurring engineering (NRE) and fixed costs including process development cost, IC design cost, mask cost, and manufacturing equipment cost are all going up exponentially with advanced process scaling. For example, it was predicted in 2018 that 3 nm would cost $4 billion to $5 billion in process development, while total IC design cost including software development and validation was estimated to almost triple from 16 to 7 nm [Reference Hruska22]. On the other hand, it was estimated that by 2014 extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography manufacturing equipment development would have already cost $14 billion [Reference Manners23]; yet it required another four years of development before its initial production use was announced in 2018 [Reference Moore24]. It is therefore imperative for the IC industry to explore alternatives to Moore’s law scaling to continue to improve IC cost performance. Since Moore’s law has been about scaling of 2D device structures, it is only natural to explore using the third dimension as an alternative or complement, hence the emergence of 3D solutions.

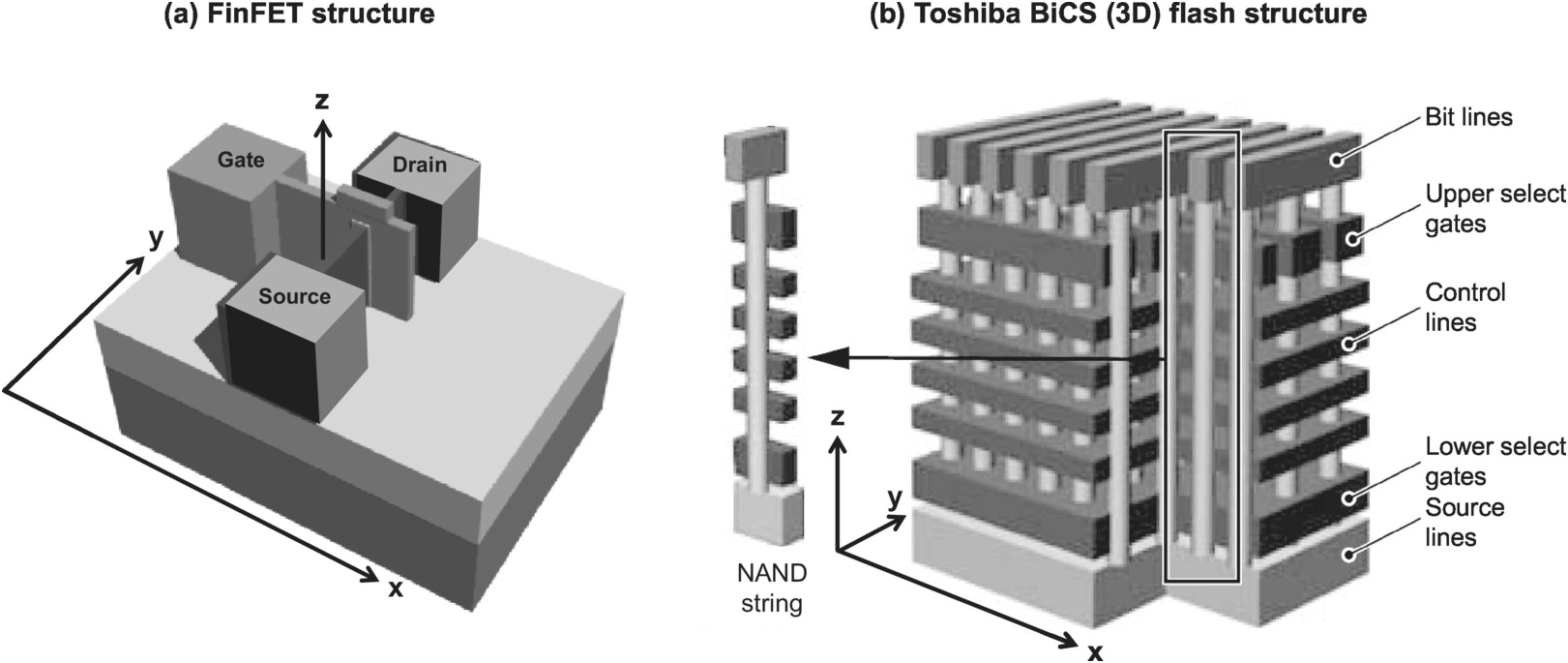

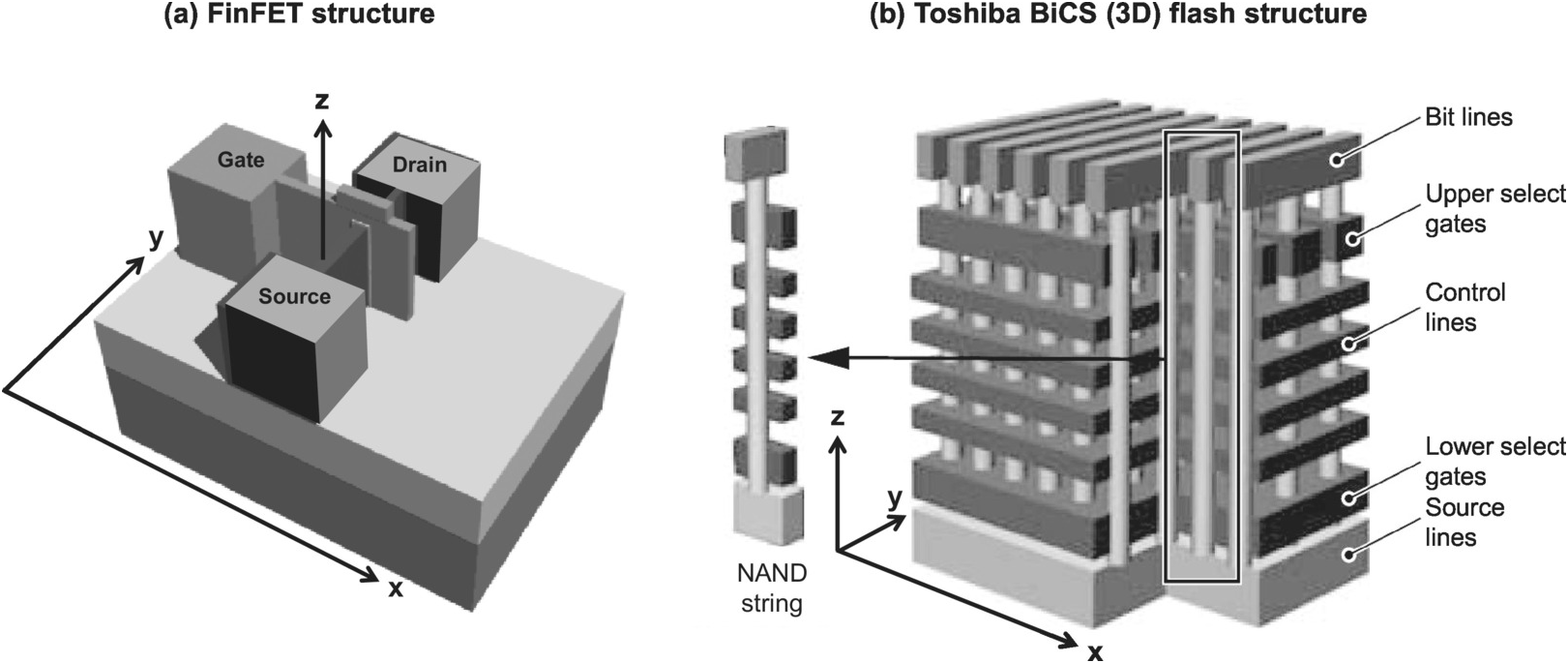

1.3.2 Monolithic 3D IC

The most advanced IC processes today employ a FinFET, which is a 3D device. This is because in FinFET the transistor gate is no longer two-dimensional but instead is wrapped around the channel utilizing the z-direction as well (Figure 1.26a). Another way to extend the 2D IC to 3D is a monolithic IC where multiple device layers are integrated in the vertical direction within the IC. A 3D NAND flash memory chip is one such example where multiple layers of memory cells are stacked on top of each other (Figure 1.26b). Scaling is achieved by increasing the number of layers. One merit of this solution is that since memory cell layers are measured in nanometer in thickness, stacking does not appreciably increase the overall thickness of the IC. In 2018, the most advanced 3D NAND flash in production had a total of more than 90 cell layers.

Figure 1.26 Monolithic 3D ICs – FinFET and 3D NAND.

However, since IC manufacturing cost and yield are highly dependent on the number of processing steps and processing complexity, monolithic 3D IC has significant cost and yield disadvantage, such that its adoption for mass production has been limited to NAND flash. Instead, 3D integration of IC chips is the leading 3D solution for logic and DRAM memory chips.

1.3.3 Conventional 3D Integration Solutions

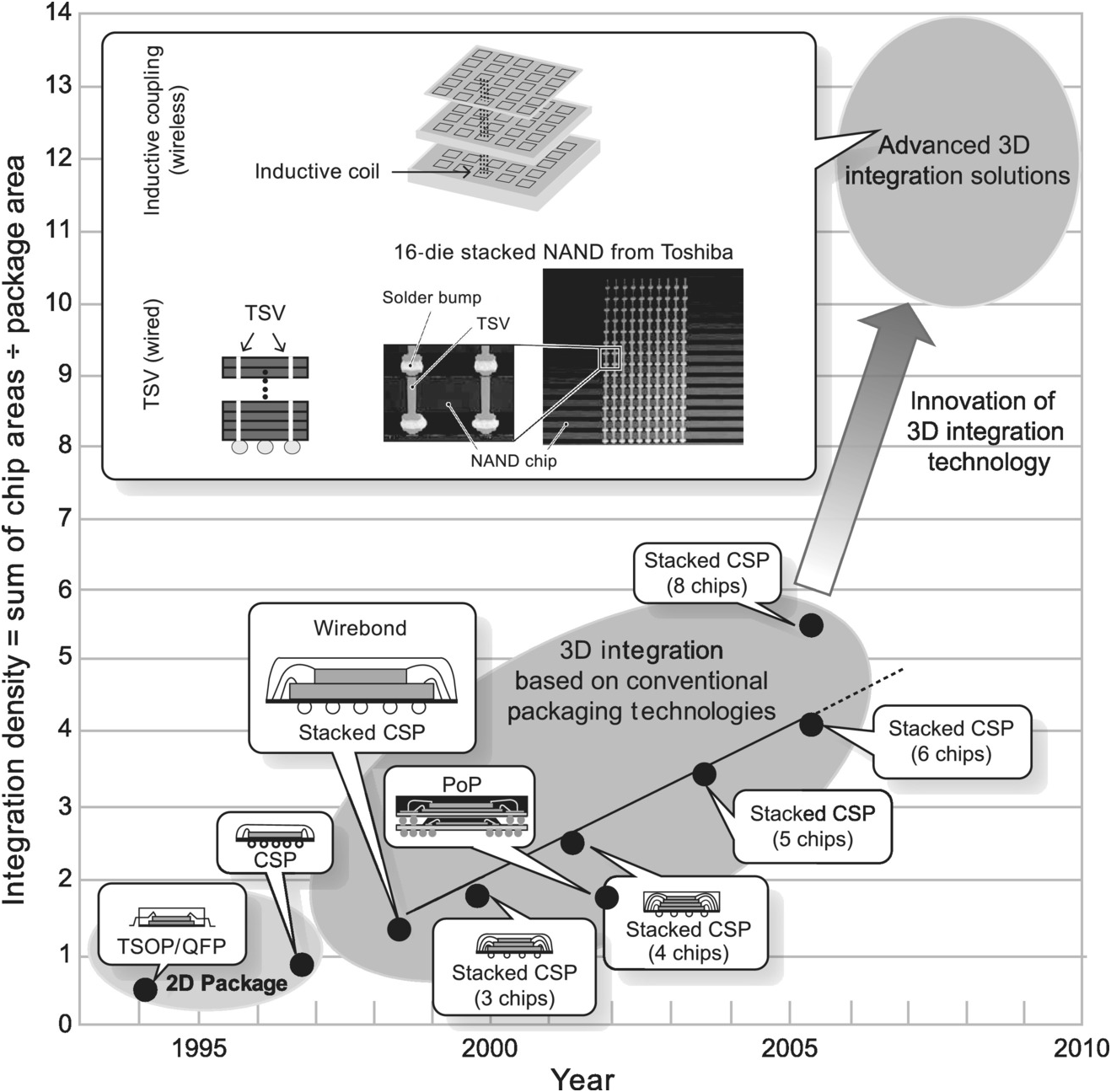

In addition to lowering IC manufacturing cost, 3D integration of IC offers two advantages over monolithic 3D IC and Moore’s law scaling of 2D IC. First, by keeping digital, analog, and memory functions implemented as separate chips, the manufacturing process for each function can be independently optimized to achieve better overall performance. Second, 3D integration enables reuse of intellectual properties (IP) by mixing and matching different chips to develop different systems without IC redesign, significantly reducing development cost in terms of both engineering cost and time to market.

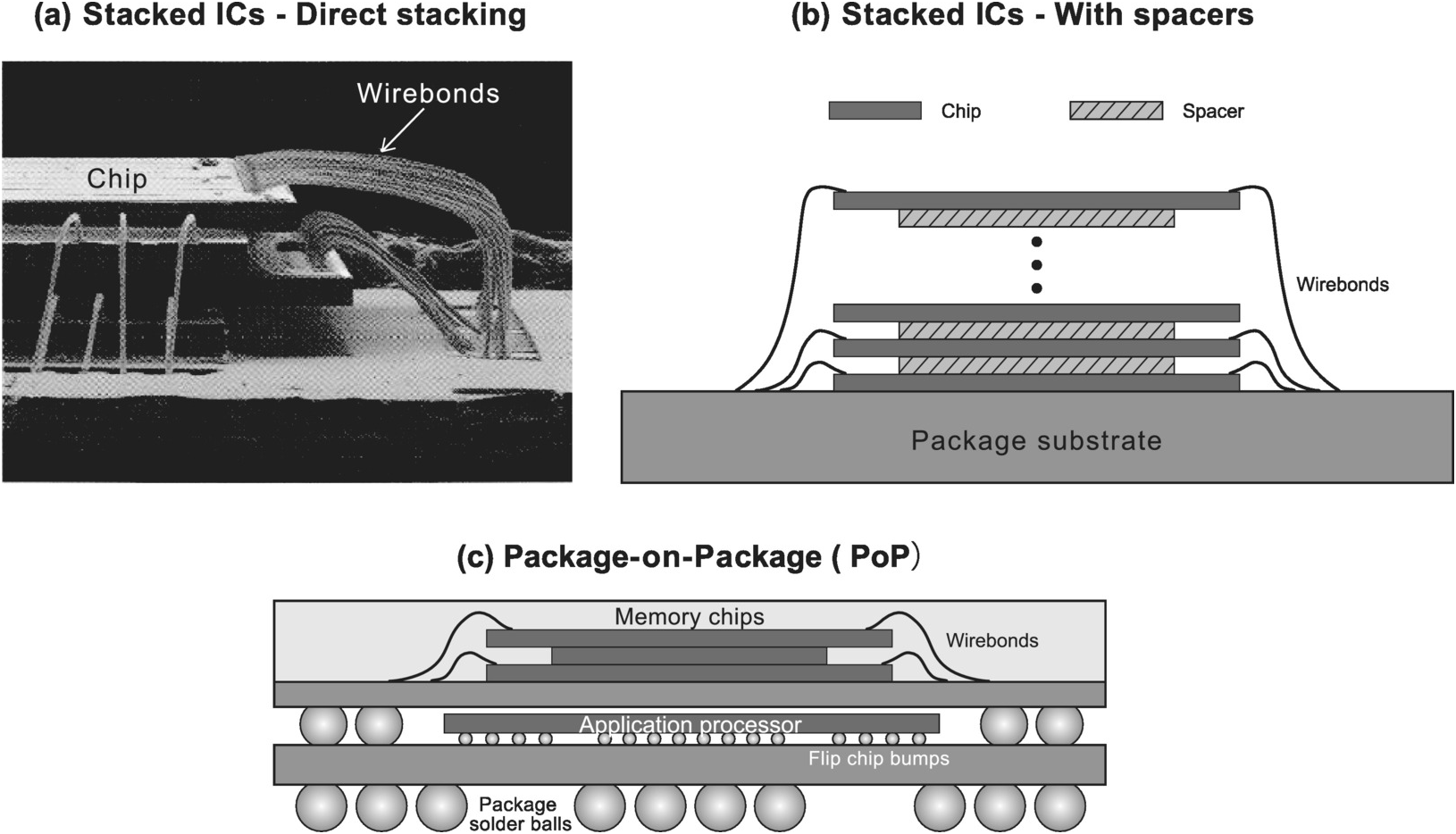

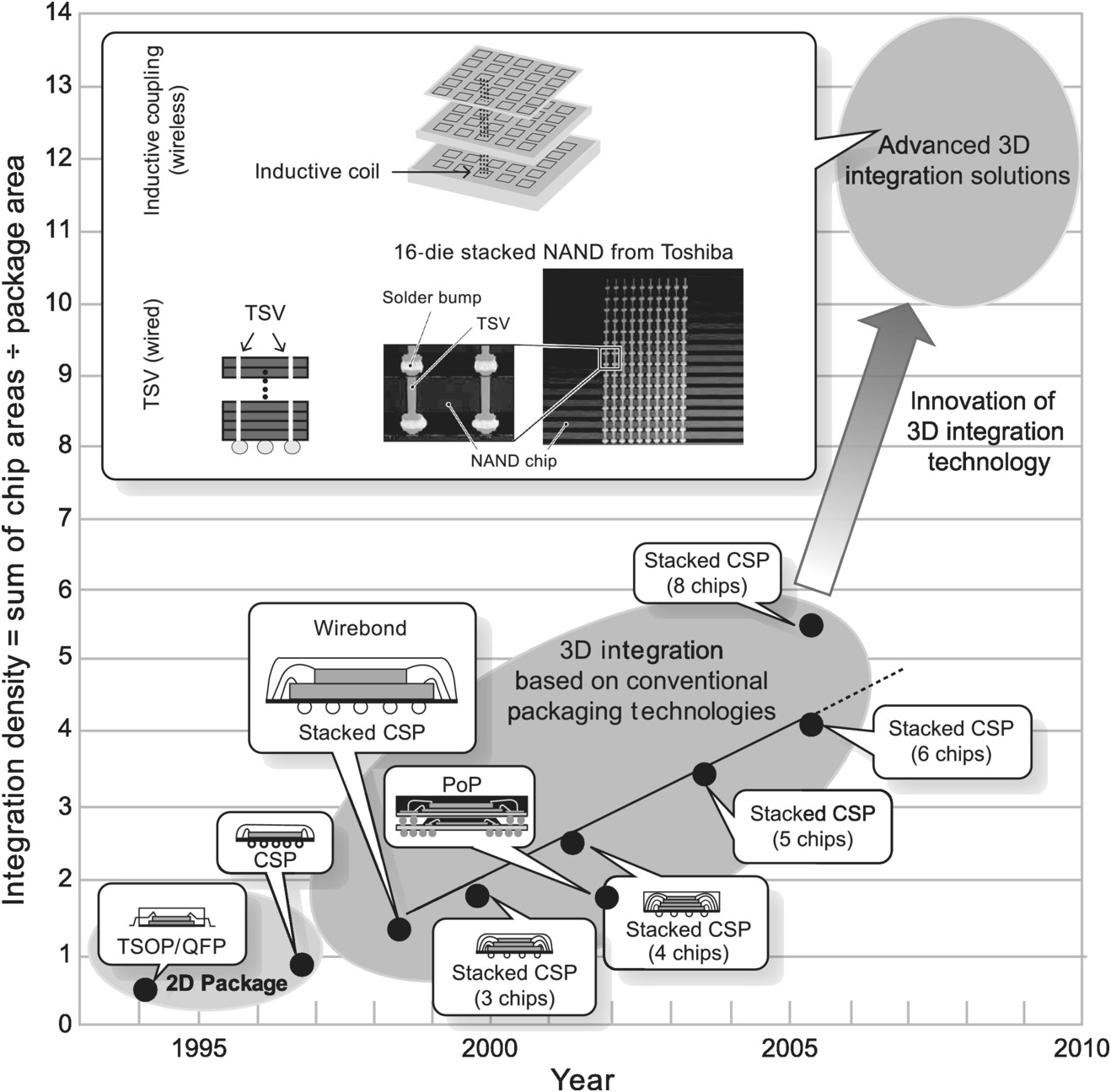

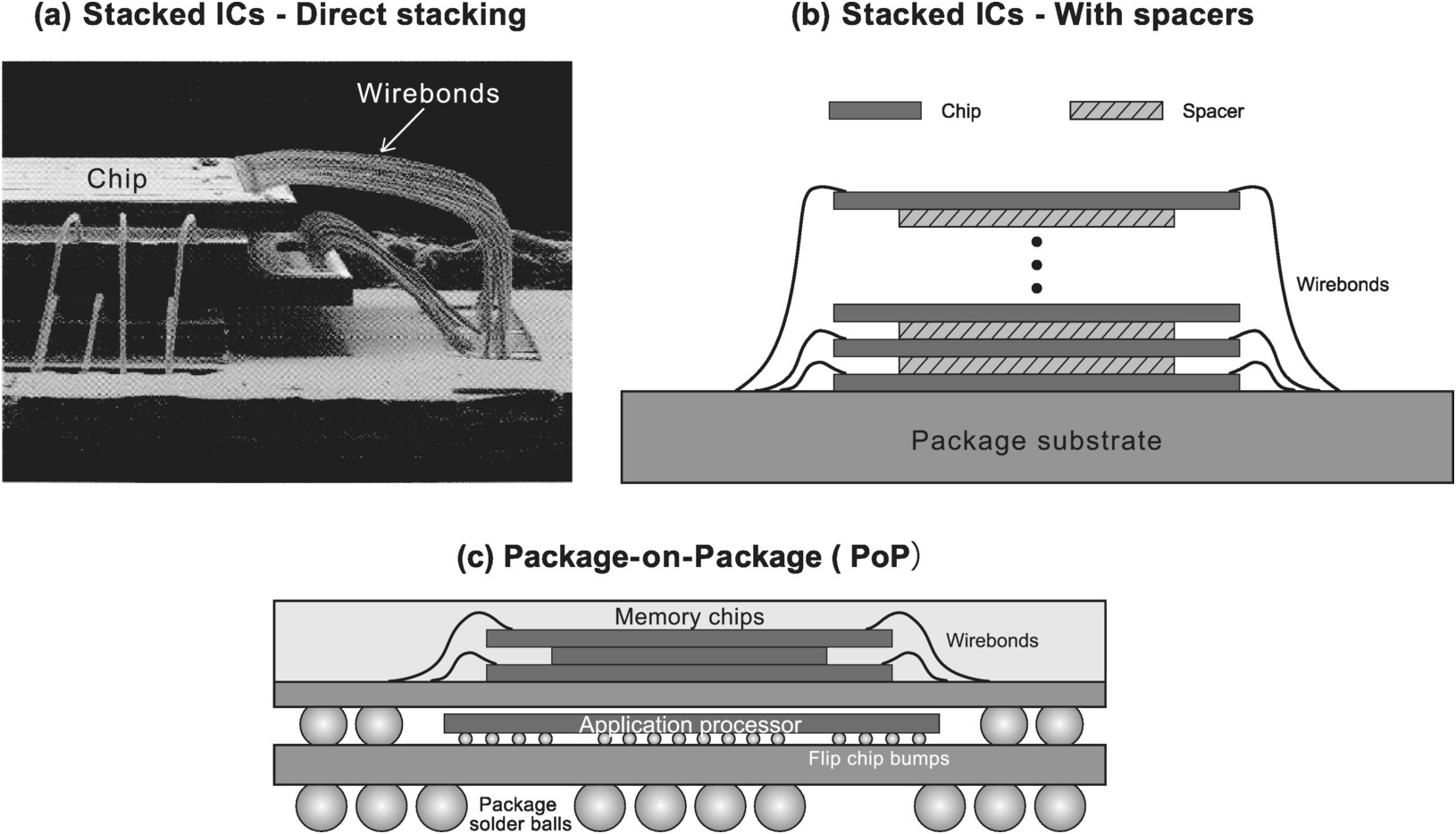

Due to these benefits, 3D integration of IC chips based on conventional packaging technologies have been in use for more than two decades. Figure 1.27 (from [26] with added PoP data point based on [Reference Yano, Sugiyama, Ishihara, Fukui, Juso, Miyata, Sota and Fujita27]) depicts the transition of IC packaging solution from 2D to 3D integration based on conventional packaging technologies in the late 1990s and the evolution of 3D integration technology thereafter. The initial solution was a stacked IC wirebond (WB) package where multiple chips are stacked face-up and wirebonded to a ball grid array (BGA) or chip scale package (CSP) substrate. The chips can be stacked directly on top of each other to minimize overall package height, or with spacers in between to create vertical clearance for wirebonding when the stacking chips are square and of the same size (Figure 1.28a and b). Then in early 2000, PoP was introduced, which stacks single- or multichip BGA packages on top of each other (Figure 1.28c).

Figure 1.27 Evolution from 2 to 3D IC integration.

Figure 1.28 Conventional 3D IC integration solutions.

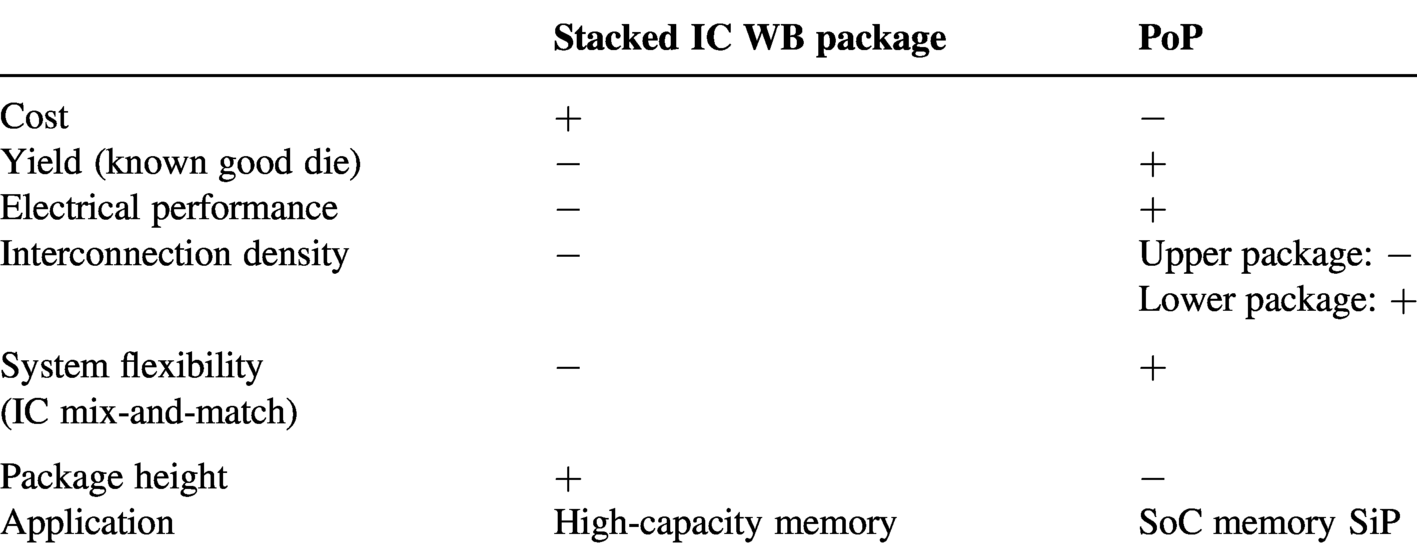

Table 1.3 compares the stacked IC WB package with PoP. While innovations are necessary to reduce wire length and loop height in the stacked IC WB package to increase the number of stacked chips, wirebonding has been in mass production for years and is therefore low cost and reliable. However, since bare dice are difficult to test, it is challenging to provide known good dice. As a result, the packaged part may have a yield problem, especially as the number of chips increases. By contrast, individual packages in a PoP are tested by their respective suppliers before they are stacked. Furthermore, the PoP assembly is done by the system user who is free to mix and match the individual packages. This provides flexibility not only in changing the content of each packaged part, such as changing the mix of memory types or capacity, but also in multisourcing. Meanwhile, since the interconnection between individual packages consists of solder balls and substrate traces, its electrical performance is generally better than wirebond interconnection, which is long and narrow. The lower package, with a full ball grid array, has high interconnection density. However, the upper package, with depopulation of the ball grid array in the center to accommodate the die on the lower package, may have limited interconnection density, especially when the lower package has a large die. Individual packages can use either wirebonding or flip-chip for die attachment. In fact, as previously noted, PoP is commonly used to build a memory SiP in a smartphone where the SoC is housed in a high-performance flip-chip package at the bottom, while memory dice in the upper package are connected to the package substrate with bond wires. Nevertheless, PoP has a disadvantage in package height since individual packages, with a substrate, solder balls, bond wires, and molding compound, are significantly thicker than individual chips.

Table 1.3. Comparison of conventional 3D IC integration solutions.

| Stacked IC WB package | PoP | |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | + | − |

| Yield (known good die) | − | + |

| Electrical performance | − | + |

| Interconnection density | − | Upper package: − Lower package: + |

| System flexibility (IC mix-and-match) | − | + |

| Package height | + | − |

| Application | High-capacity memory | SoC memory SiP |

Rather than stacking heterogeneous chips to create an SiP, the stacked IC WB package, given its drawbacks, is commonly used for stacking homogeneous chips to create a high-capacity memory solution. This is because stacking of low-cost memory chips requires a low-cost solution. Furthermore, being low cost and having high yield means known good die is not as important a requirement. Finally, many chips need to be stacked for capacity, making a stacked IC WB package a better fit than PoP. For instance, [Reference James30] reports a nine-stack, 32 Gb micro-SD flash memory card from Sandisk, as well as a 16-stack, 64 Gb NAND part in an iPhone from Samsung.

Meanwhile, despite the advantages of PoP over the stacked IC WB package, its height disadvantage limits its applicability. When Sharp introduced its PoP technology in 2002, it showed a three-stack example [Reference Yano, Sugiyama, Ishihara, Fukui, Juso, Miyata, Sota and Fujita27], so the technology supports stacking of more than two packages. However, the total stack thickness increases rapidly as the number of packages increases, since package thickness is on the order of 500 µm (without including the solder ball standoff) as opposed to die thickness that is on the order of 50 µm after thinning. As a result, direct die stacking is the preferred solution for stacking many ICs together.

Nevertheless, the use of wirebonding technology in the stacked IC WB package makes it difficult to overcome its disadvantages. In particular, the poor electrical characteristics of bond wires, which result in poor signal and power integrity, prevents it from being used for high-performance chips such as processors, especially as wire length increases with the number of chips being stacked. Furthermore, since wirebonding is a peripheral interconnect technology where bond pads are placed along the perimeter of the IC, most commonly in one or two staggered rows, it is difficult to significantly increase the interconnection density to increase bandwidth. Consequently, an area array interconnect technology with better electrical characteristics and shorter interconnects is needed for heterogeneous 3D chip integration for high-performance systems.

1.3.4 Advanced 3D Integration Solutions

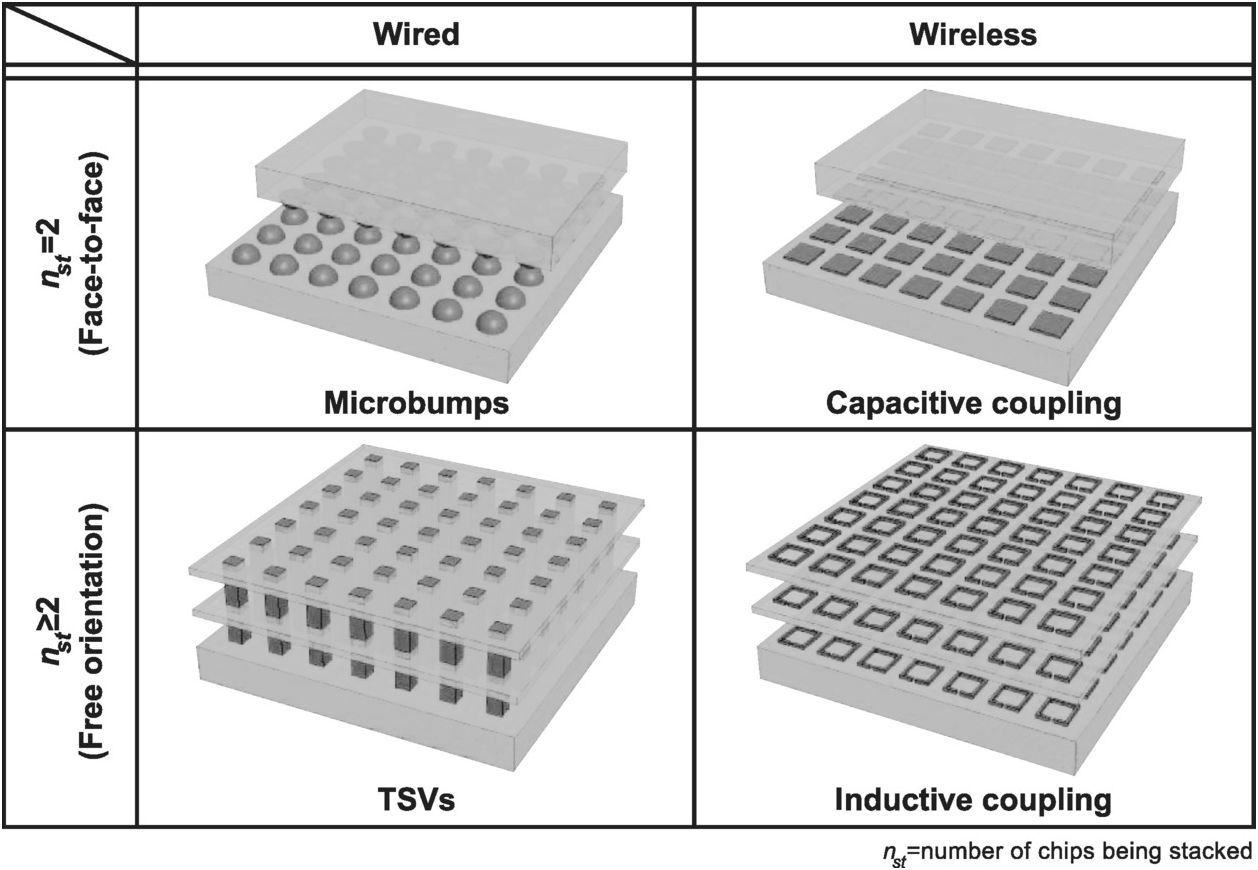

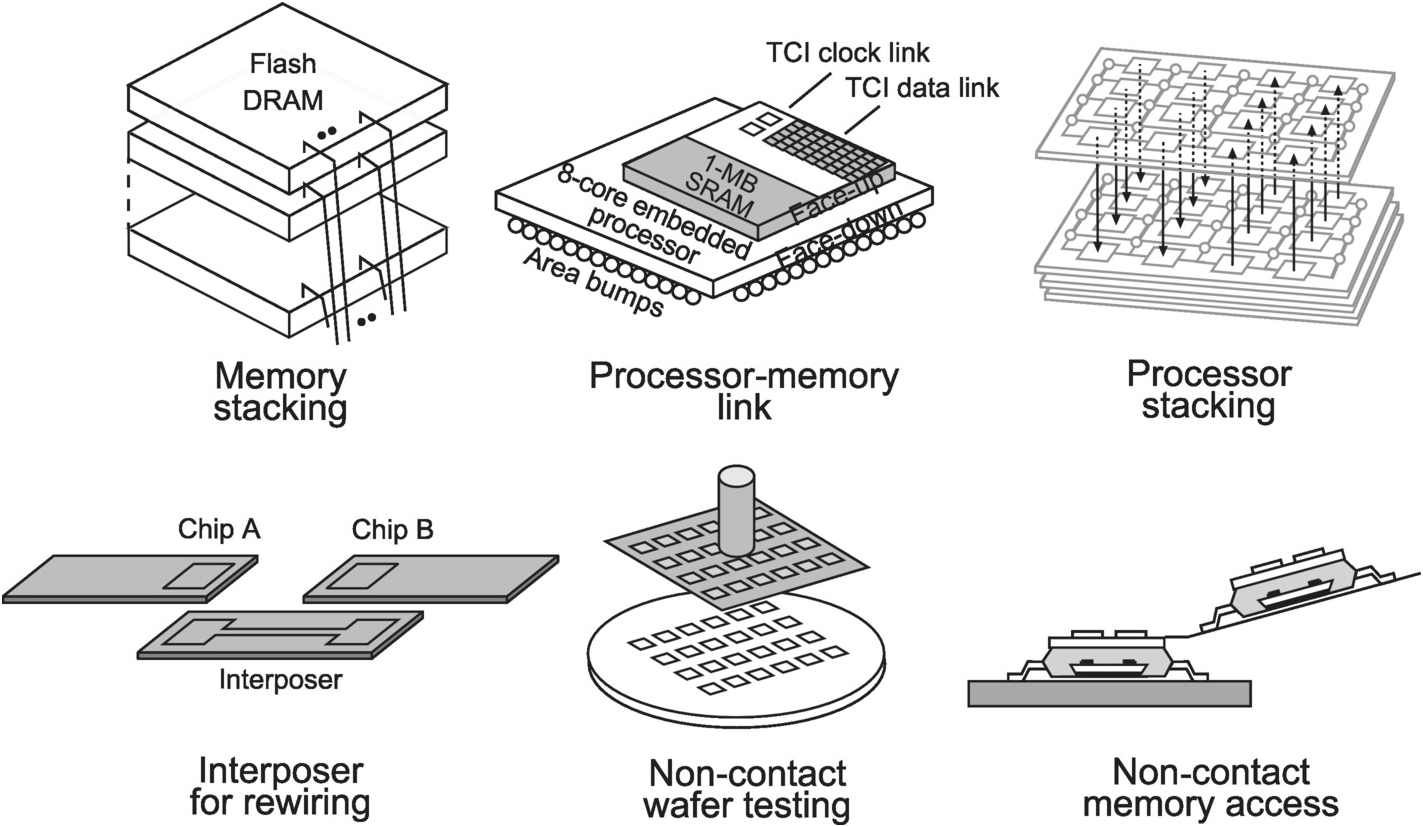

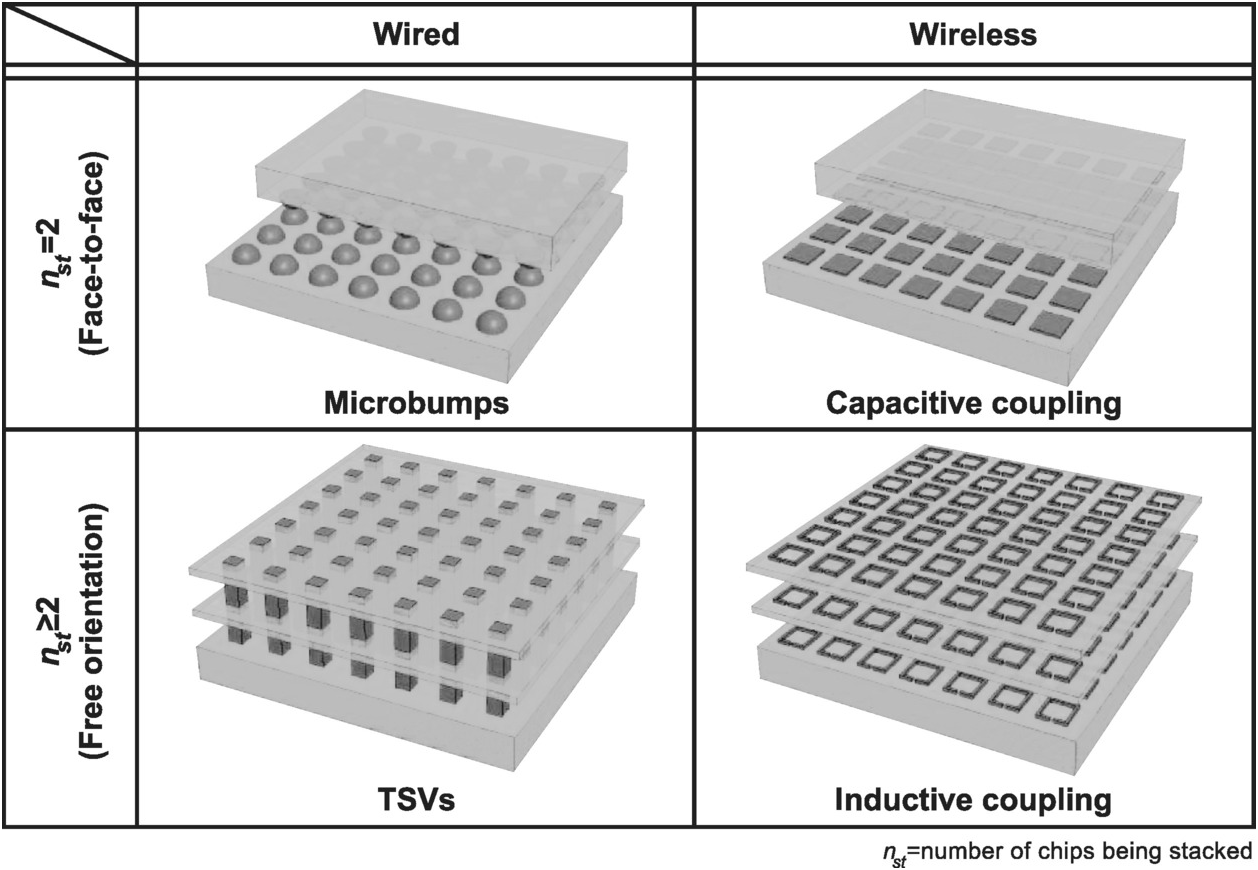

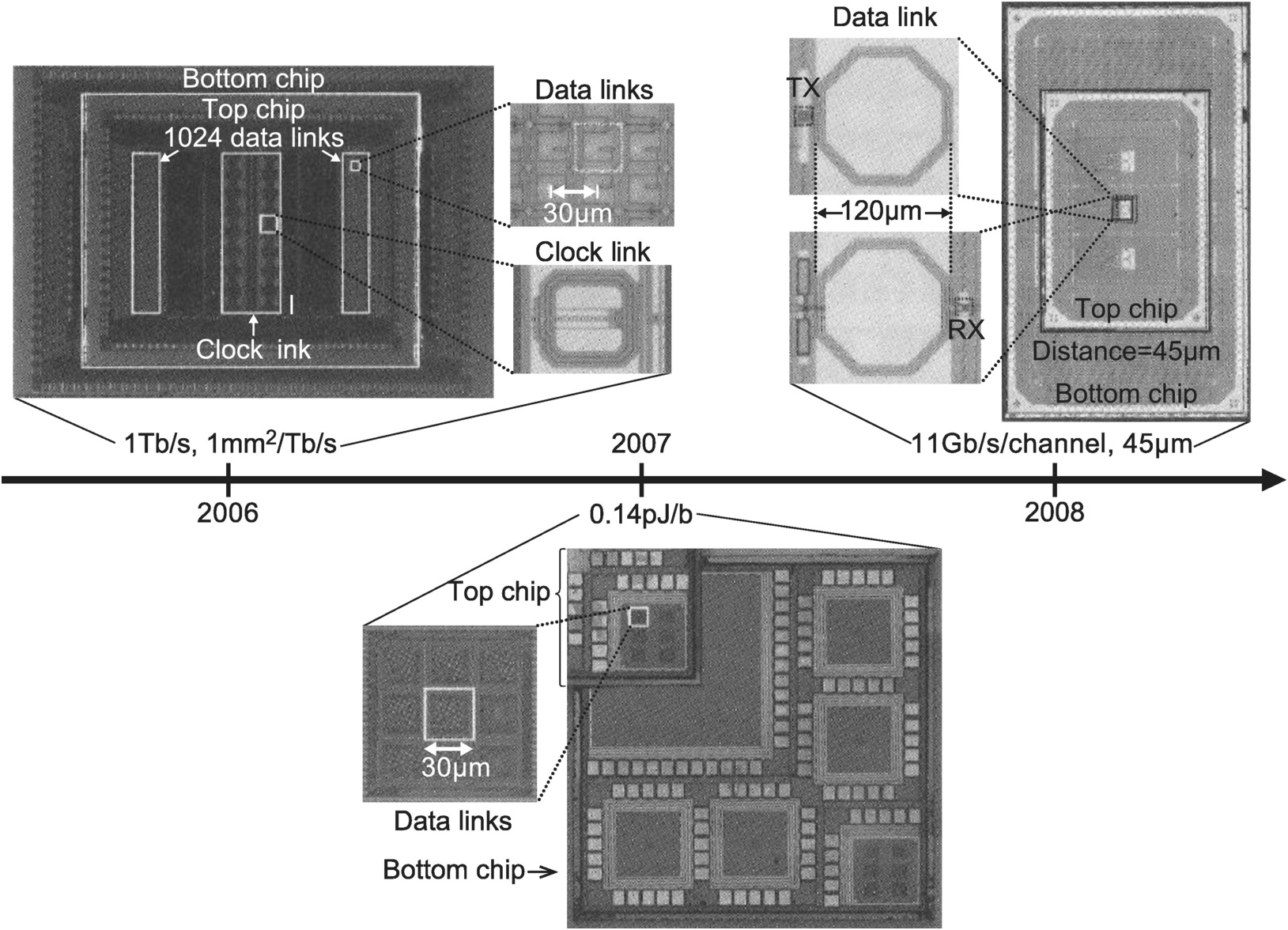

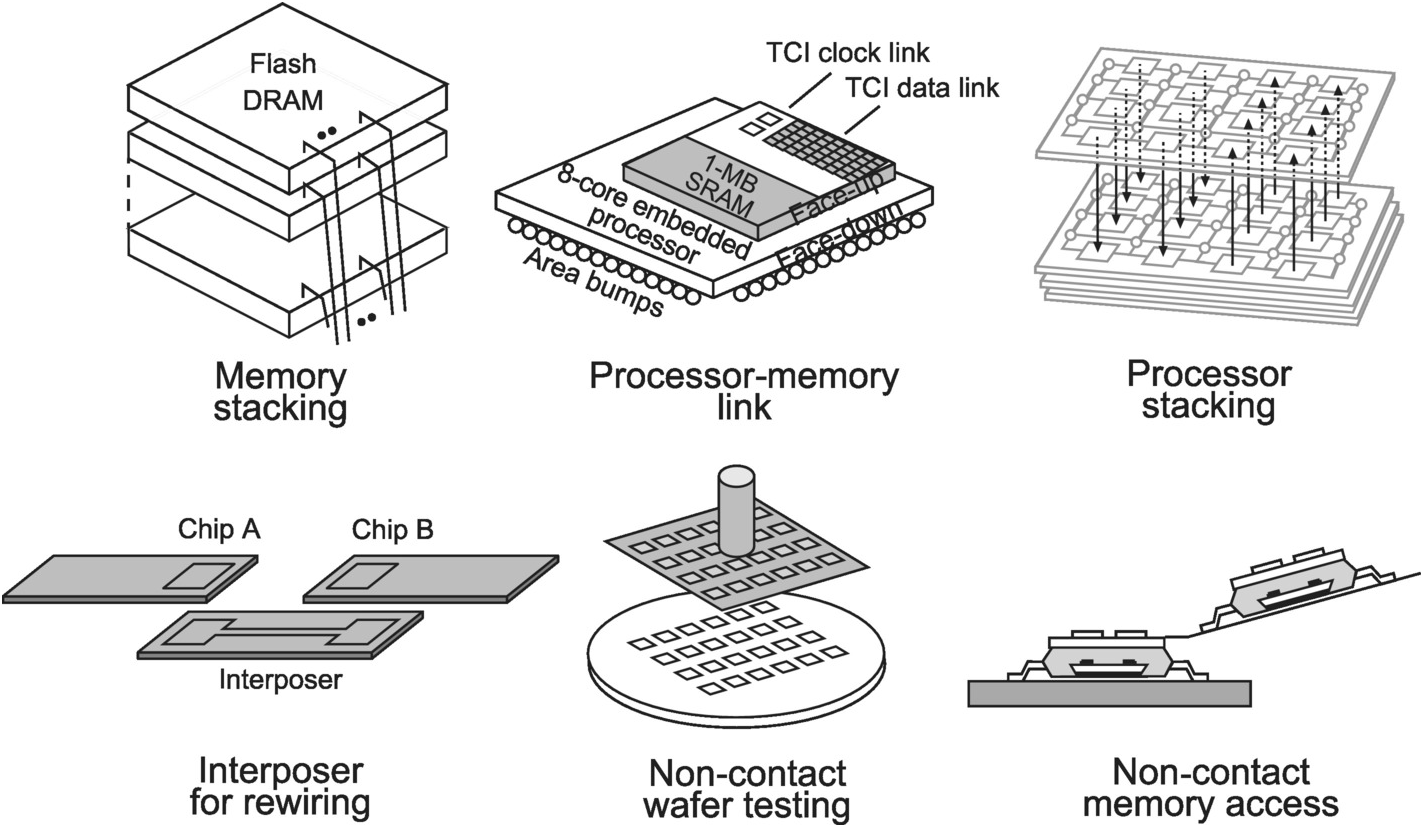

To address the limitations of conventional 3D IC integration solutions, various advanced solutions have been in development to dramatically increase interconnection density and/or the number of ICs that can be integrated. These solutions can generally be classified as wired vs. wireless, and nst = 2 (face-to-face) vs. nst ≥ 2 (free orientation) solutions, where nst is the number of stacked chips (Figure 1.29, [Reference Ezaki, Kondo, Ozaki, Sasaki, Yonernura, Kitano, Tanaka and Hirayarna31]–[Reference Mizoguchi, Yusof, Miura, Sakura and Kuroda34]). All four classes of solutions offer significant improvement in interconnection density and communication distance compared to conventional solutions. Since connection terminals are placed in an area instead of peripheral array in all solutions, the number of interconnections can be increased in a quadratic fashion. On the other hand, because adjacent chips communicate with each other directly instead of through a package substrate, communication distance and hence interconnect lengths are greatly reduced.

Figure 1.29 Advanced 3D IC integration solutions.

Two variants of wired 3D IC integration solutions using microbumps [Reference Ezaki, Kondo, Ozaki, Sasaki, Yonernura, Kitano, Tanaka and Hirayarna31], [Reference Kumagai, Yang, Izumino, Narita, Shinjo, Iwashita, Nakaoka, Kawamura, Komabashiri, Minato, Ambo, Suzuki, Liu, Song, Goto, Ikenaga, Mabuchi and Yoshida35] and through-silicon-vias (TSVs) [Reference Burns, McIlrath, Keast, Lewis, Loomis, Warner and Wyatt32] respectively have entered production. Microbump technology employs small solder bumps formed on the chip surface to vertically connect two chips together. Since connection terminals are on the front side of the chips, the two chips must be oriented face to face for interconnection, which precludes integration of more than two chips. Hence, nst = 2. On the other hand, with TSV, as the name suggests, via holes through the silicon substrate are created to add connection terminals to the backside of the chip as well. Interconnection between chips may still be created using microbumps. But since interconnection can be established using both the front and backside of the chip, integration of more than two chips (nst ≥ 2) becomes possible. TSV therefore has broader applicability than microbump alone.

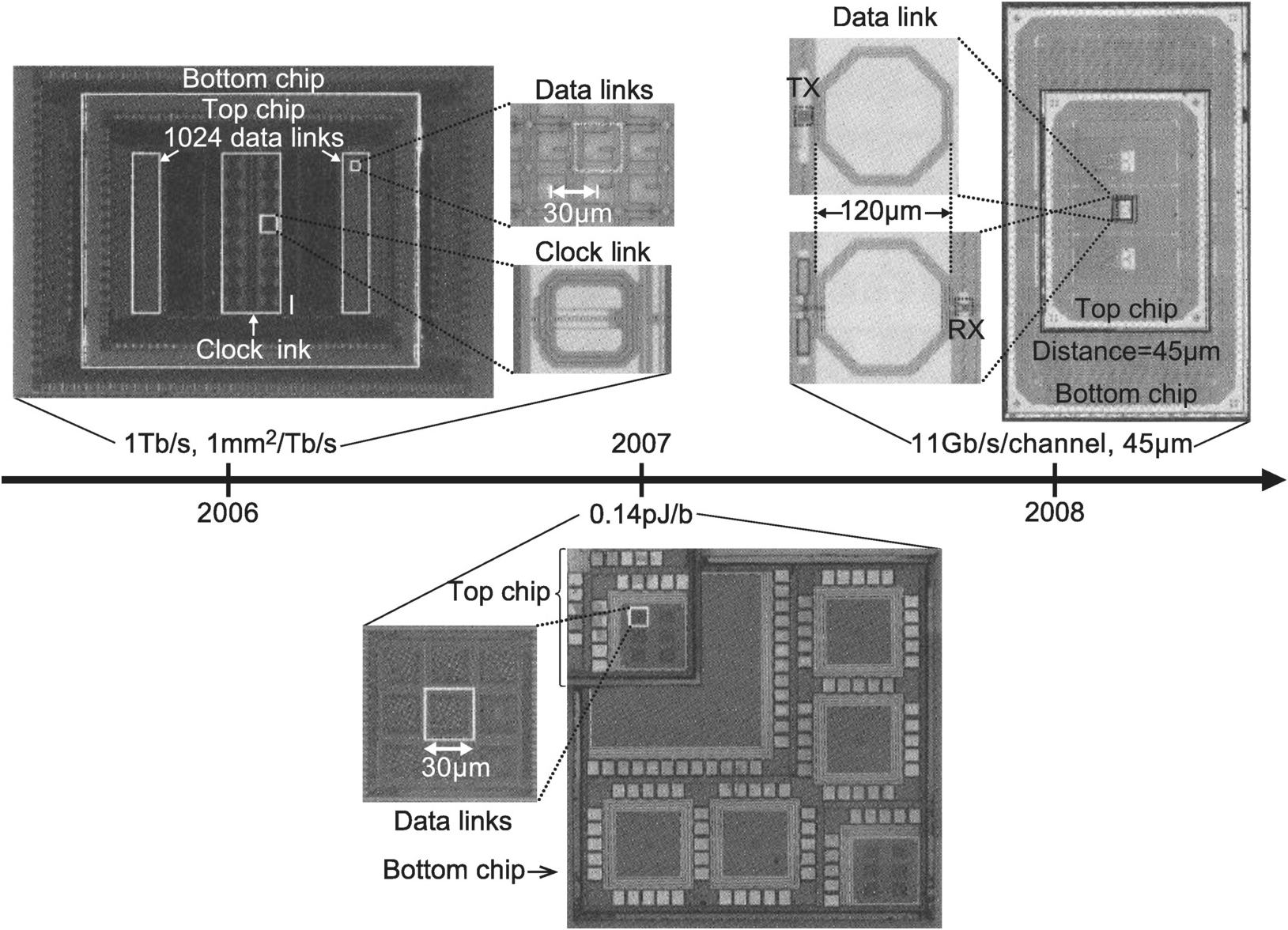

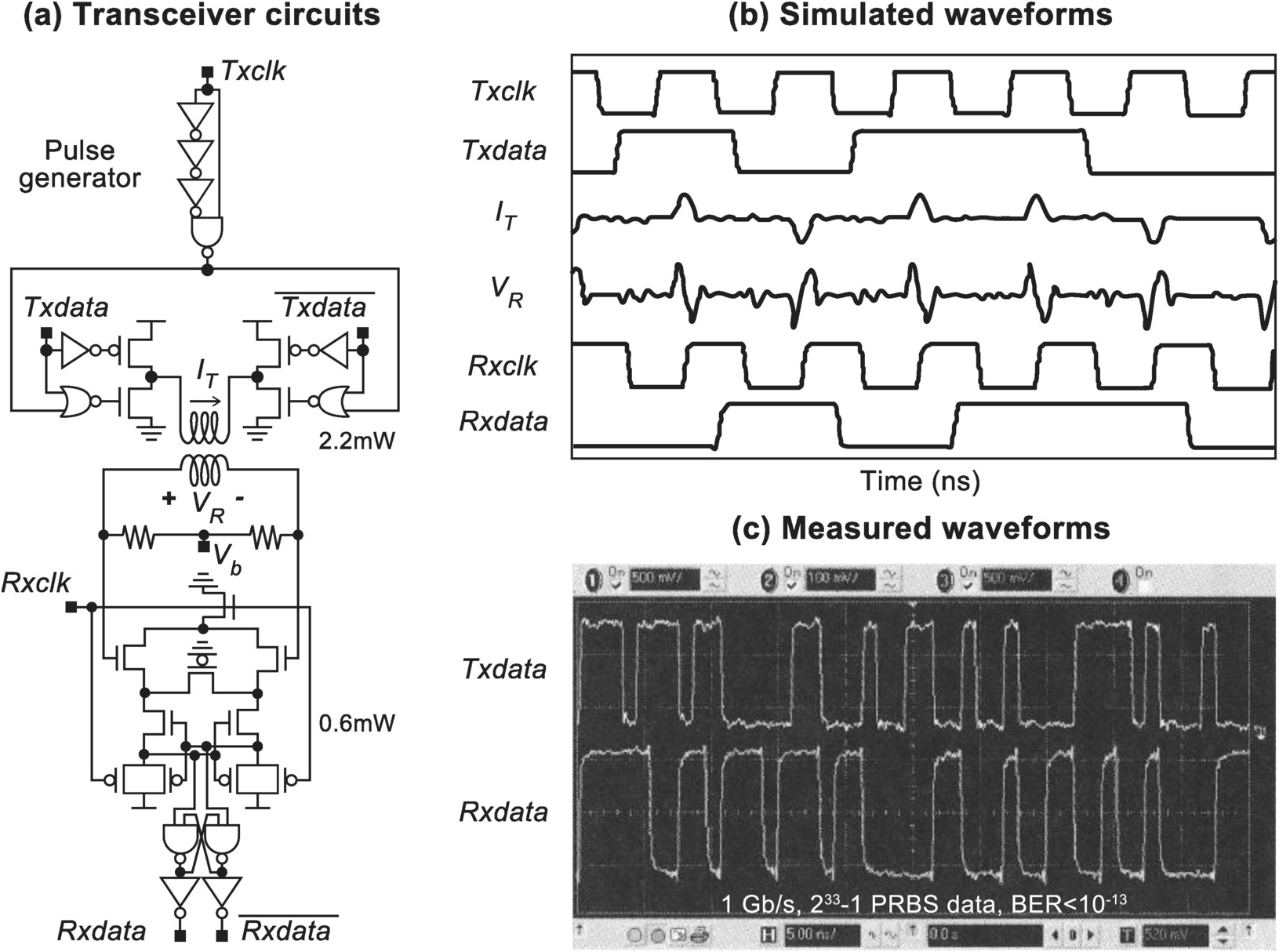

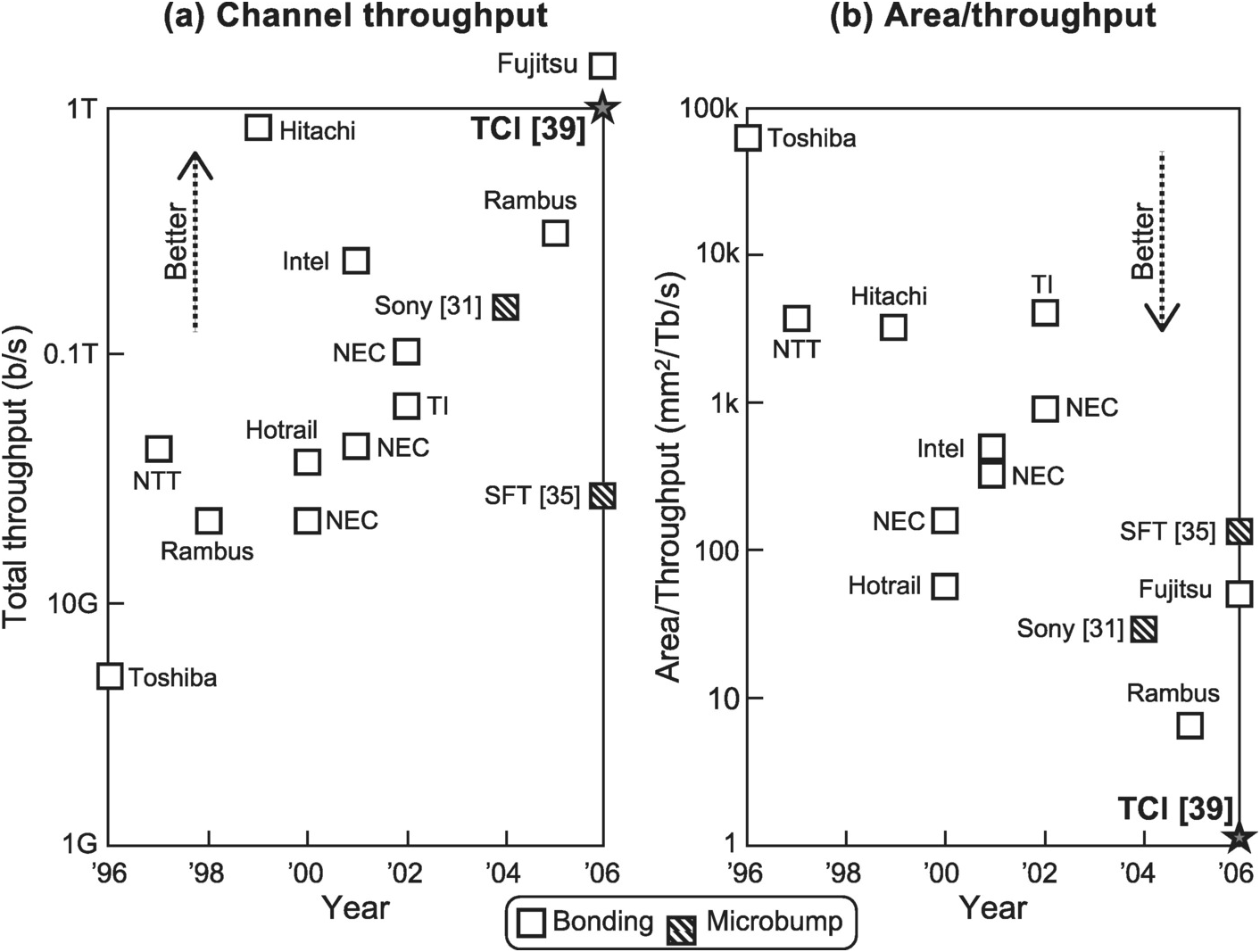

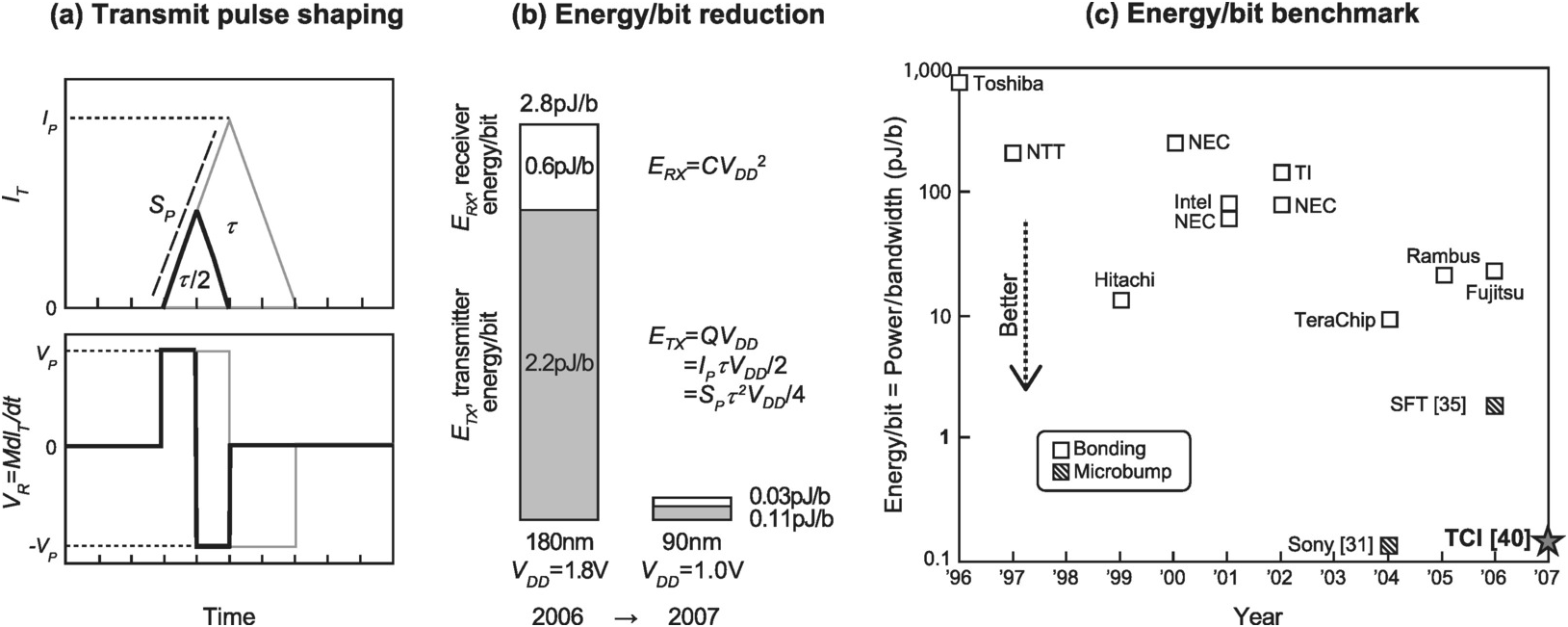

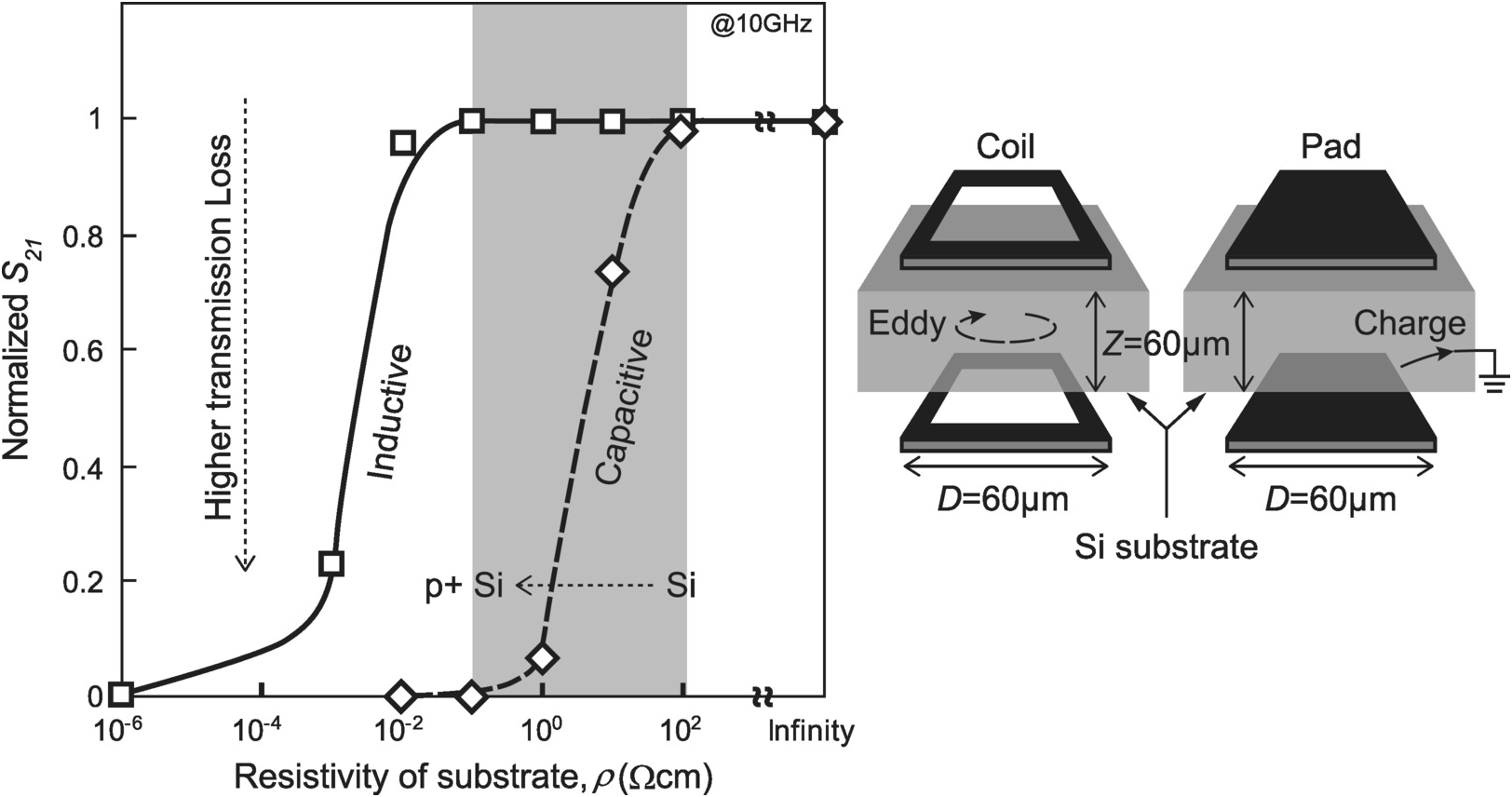

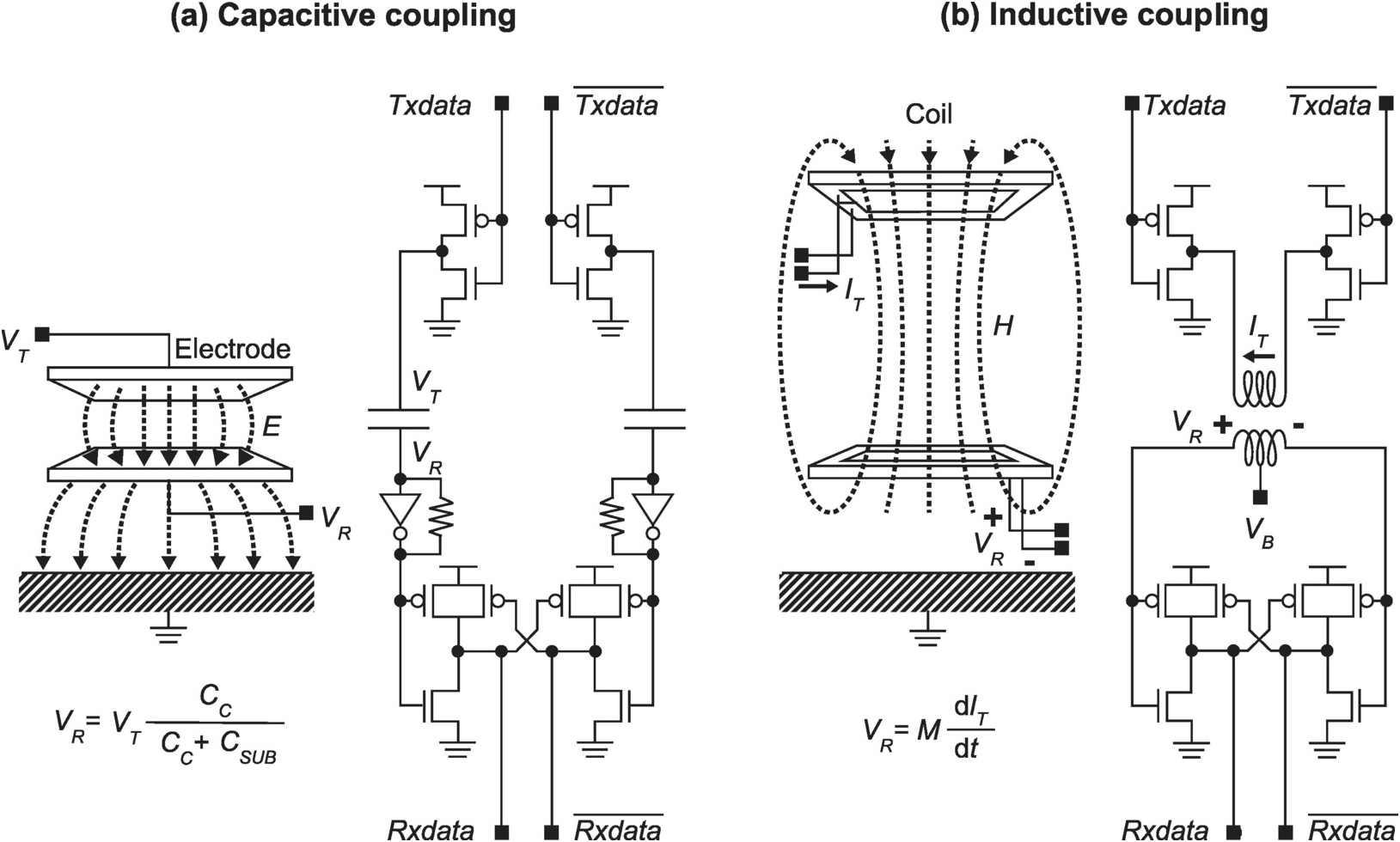

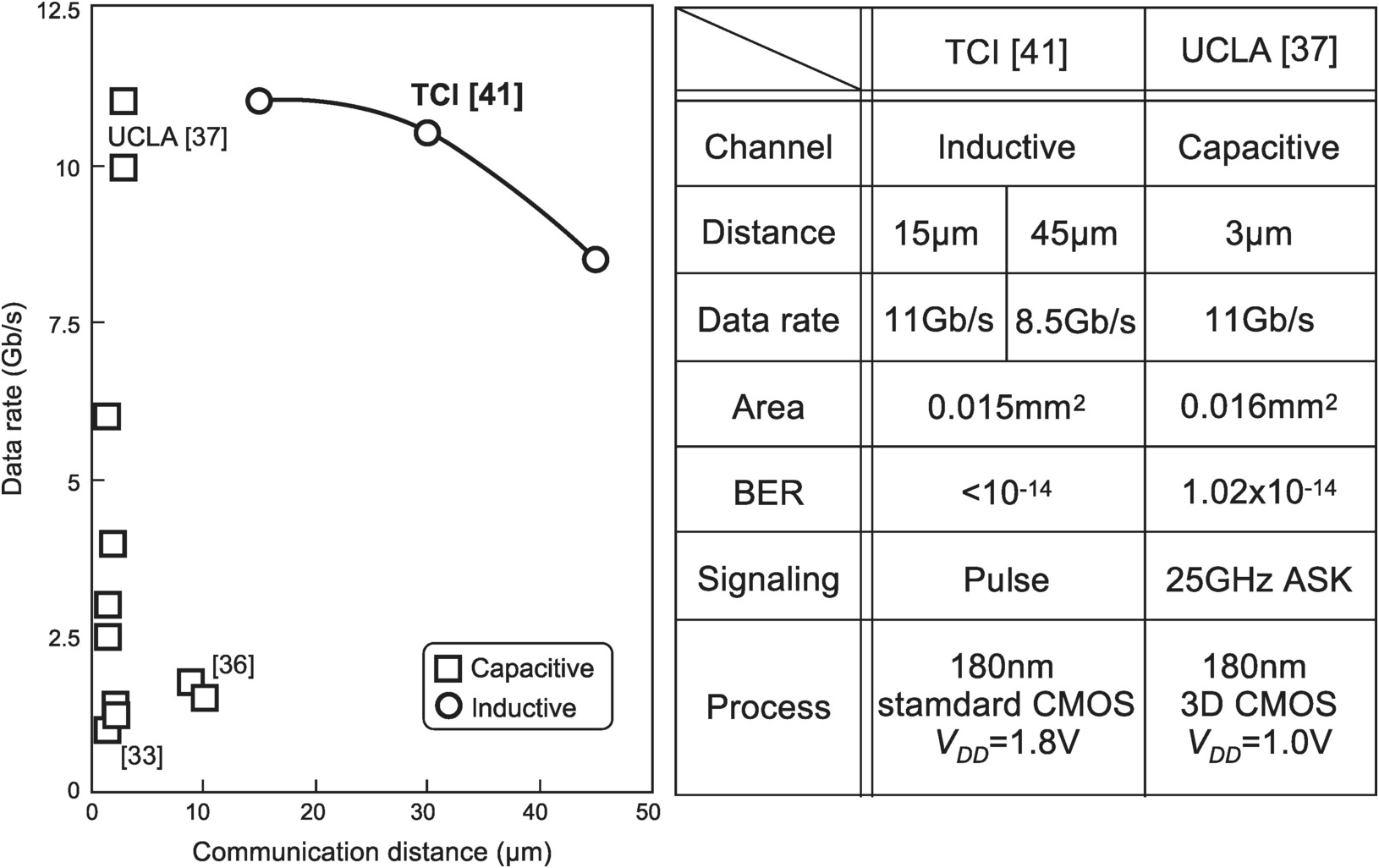

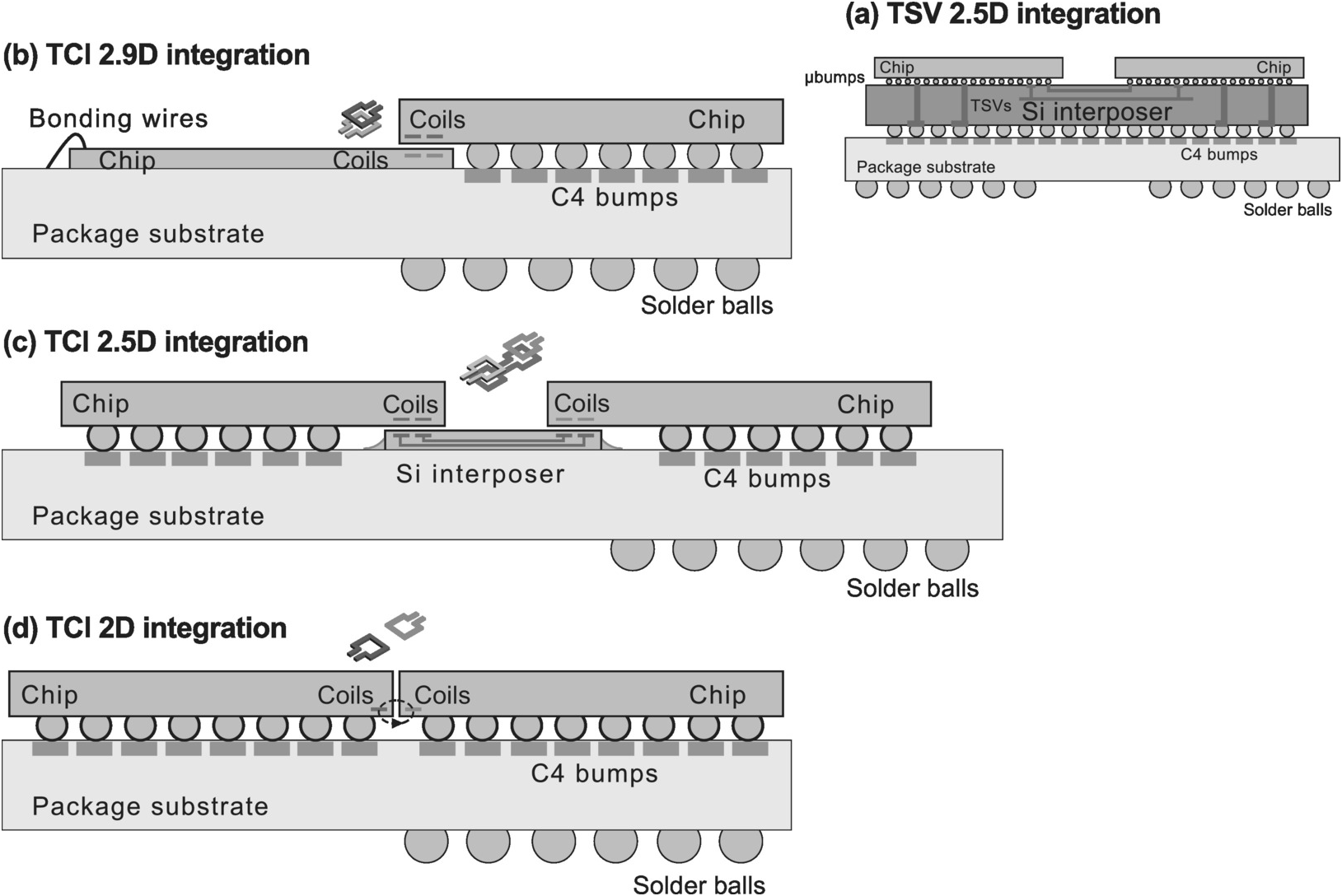

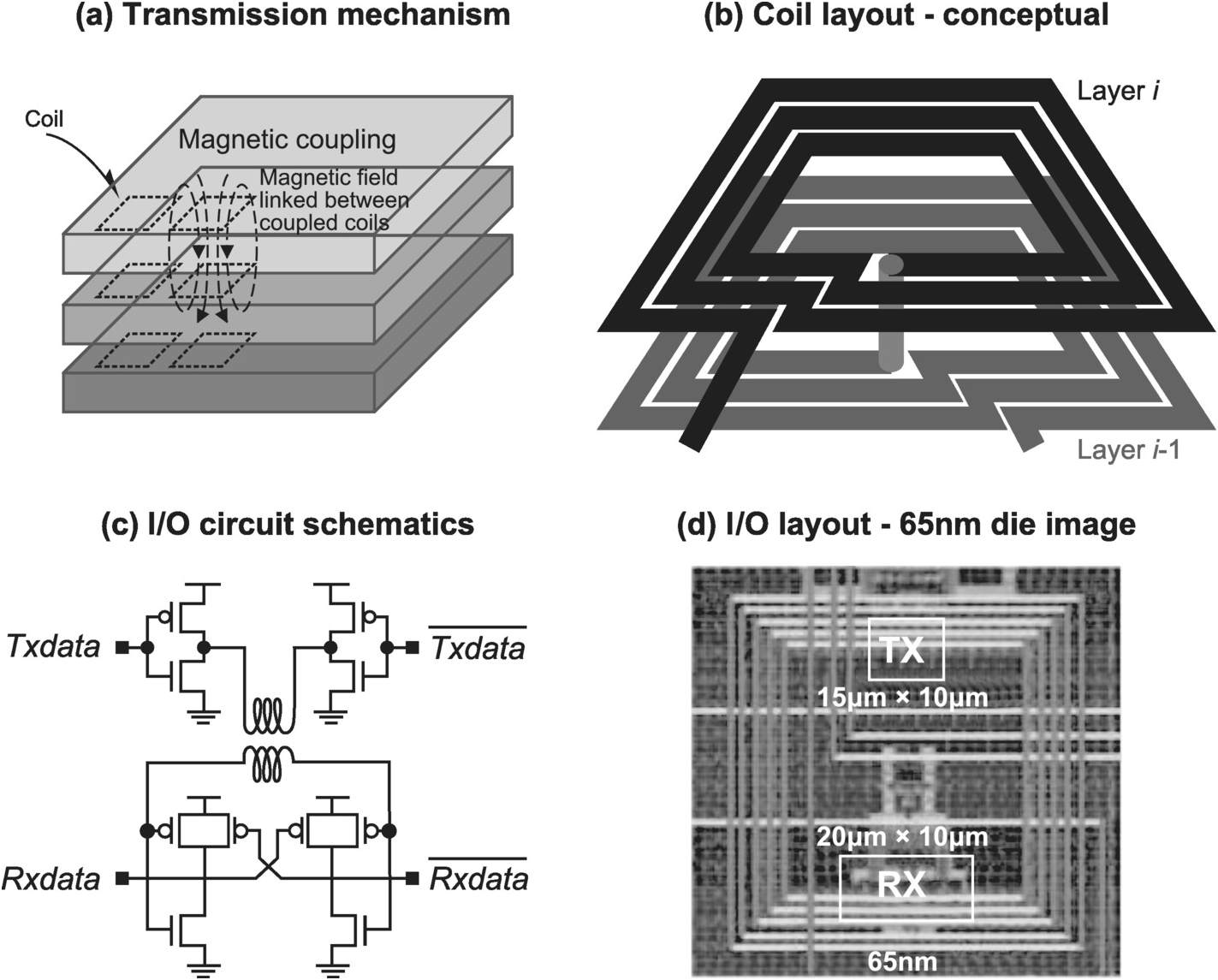

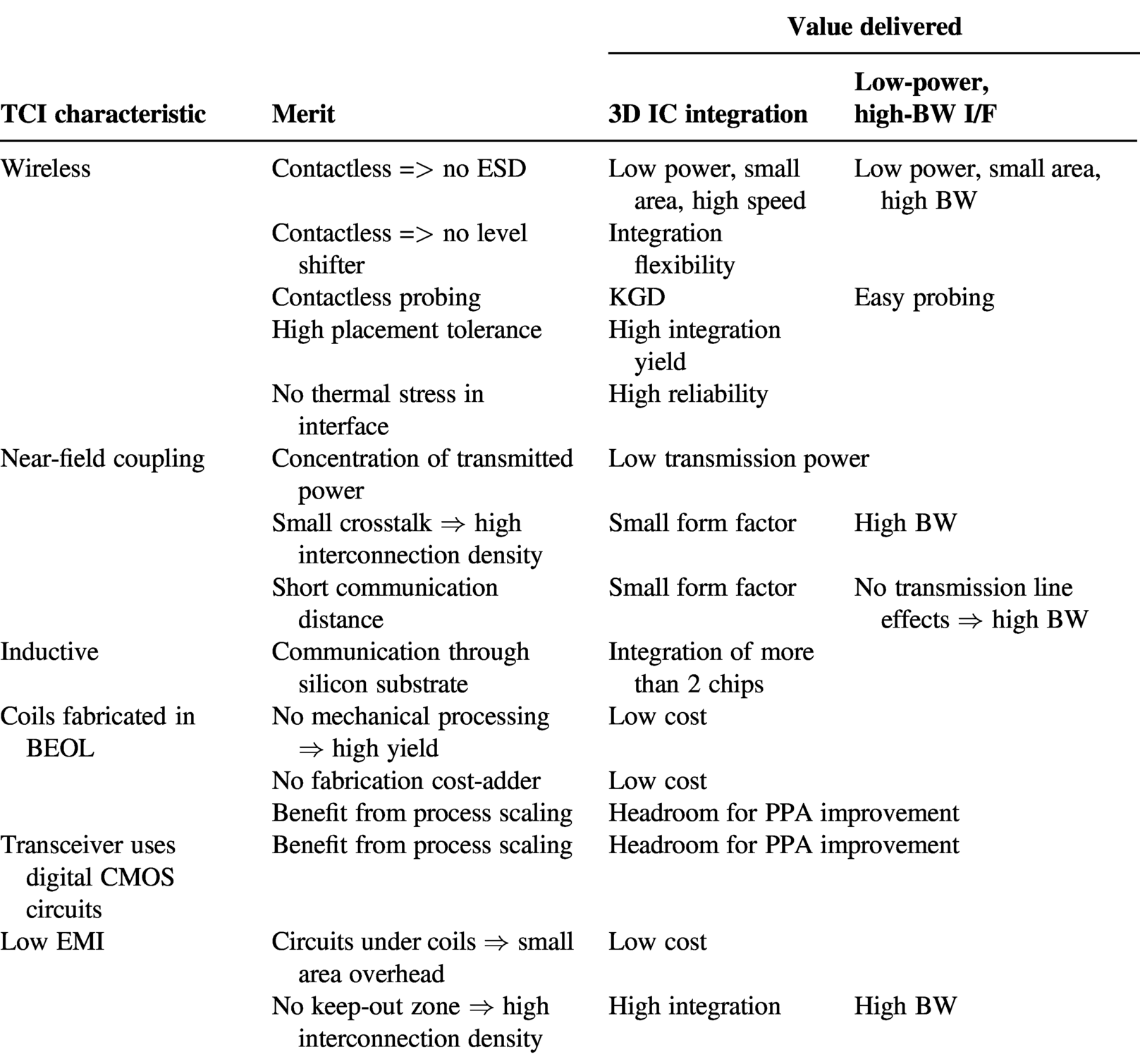

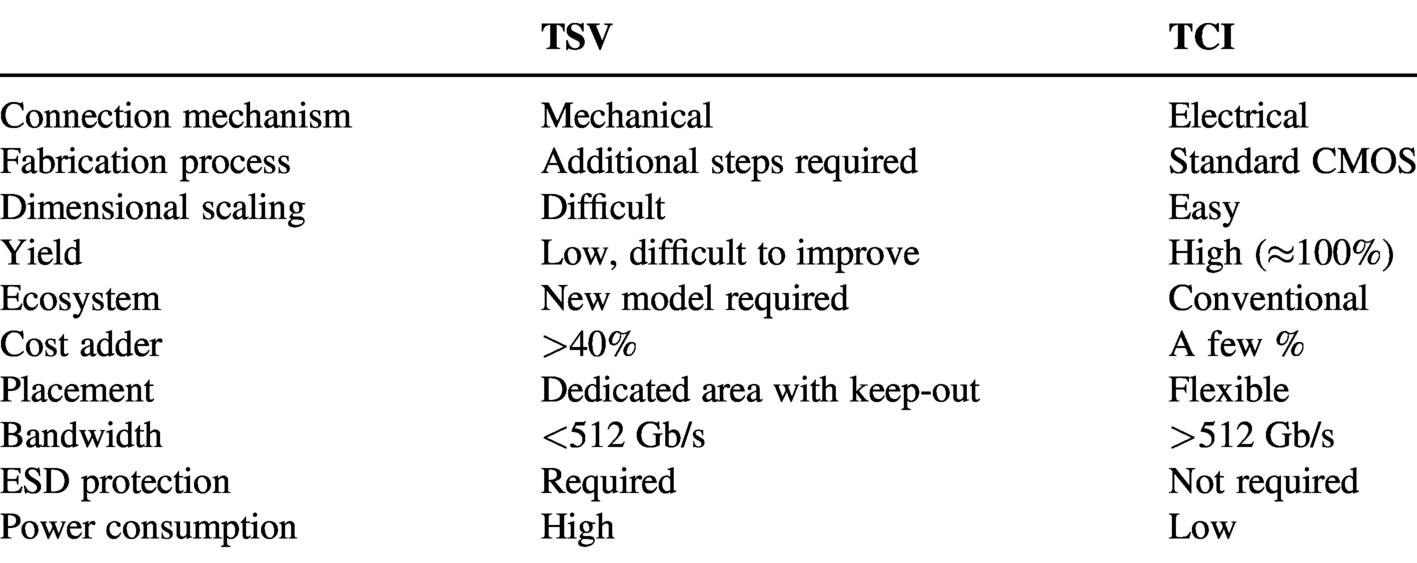

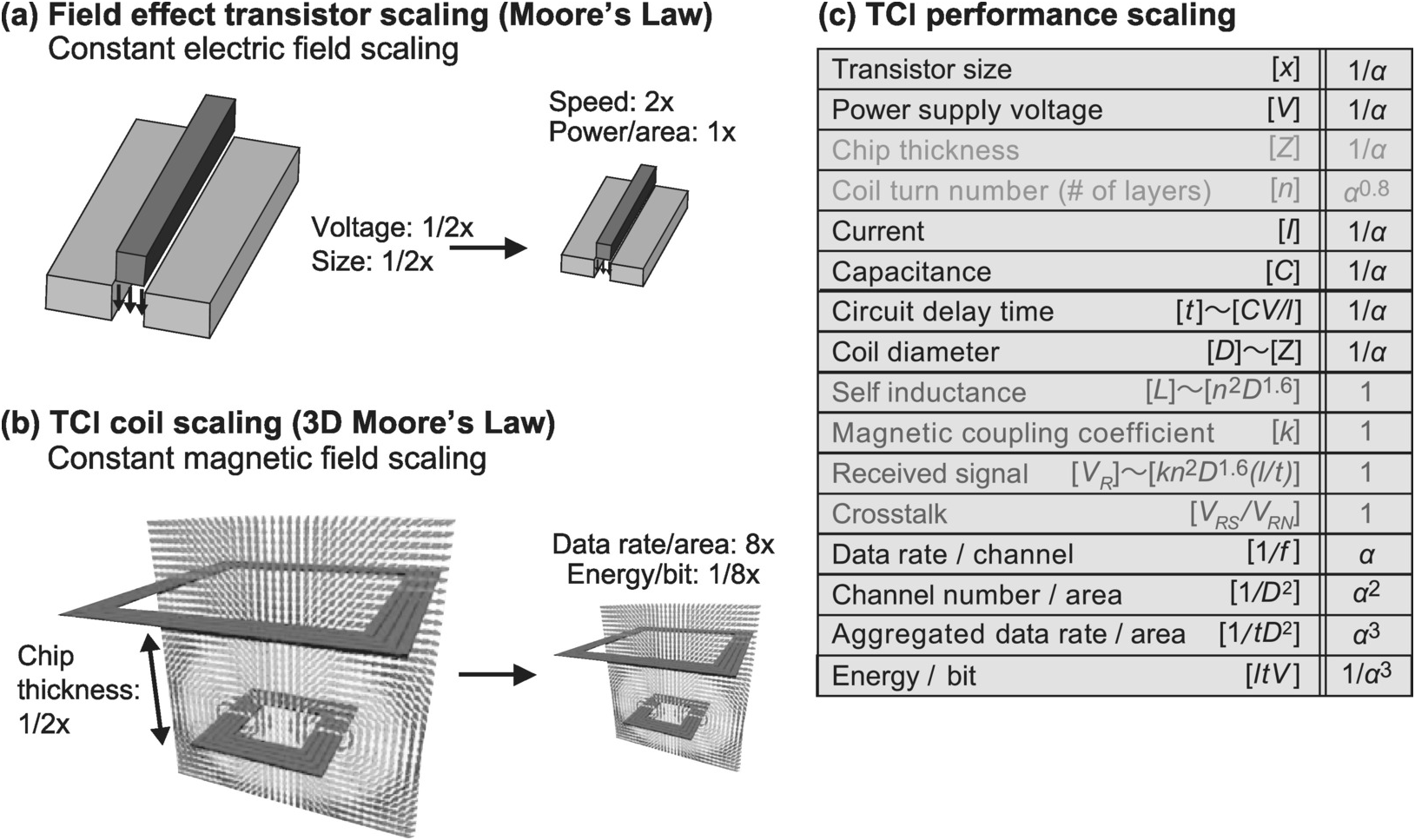

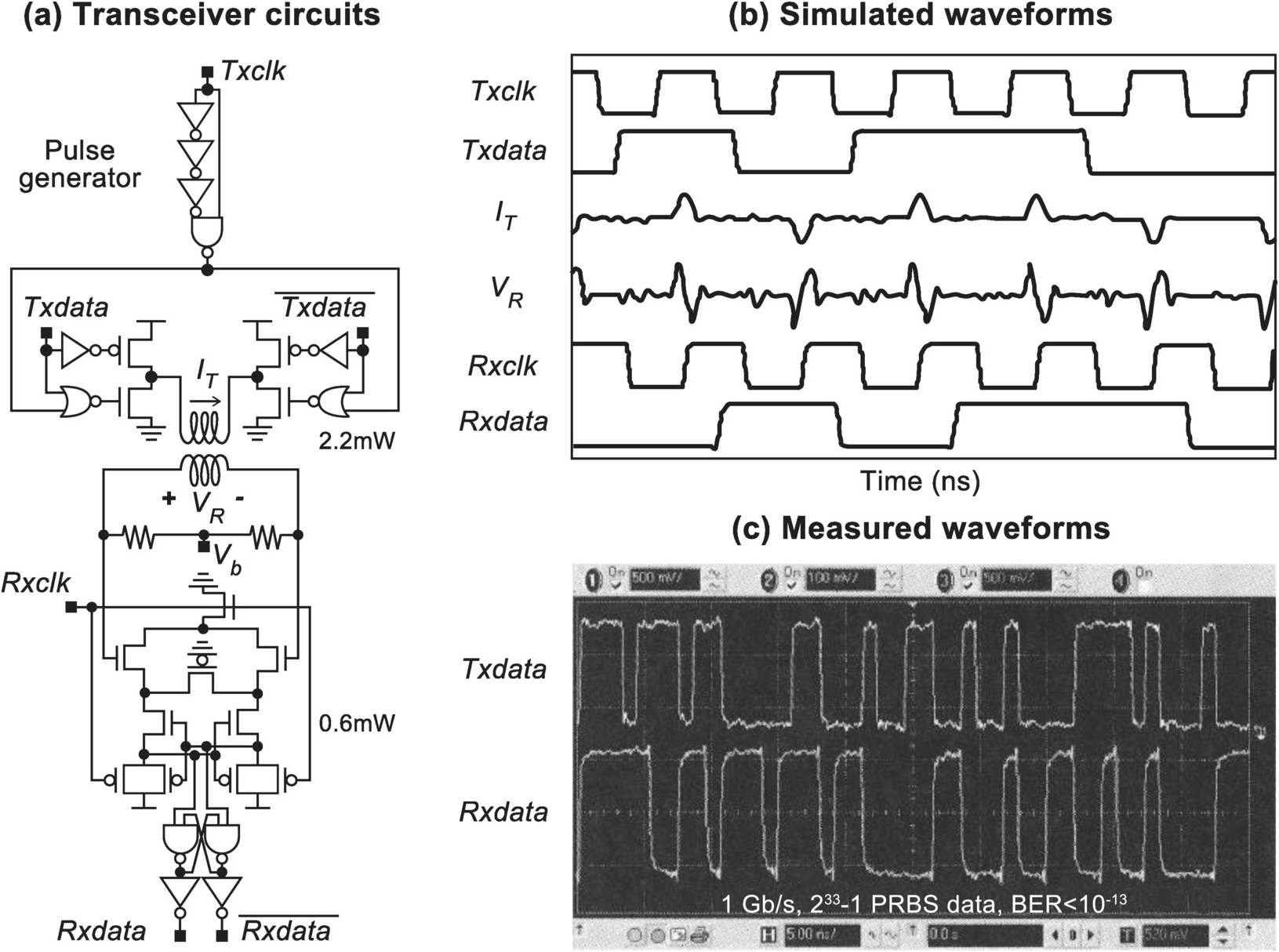

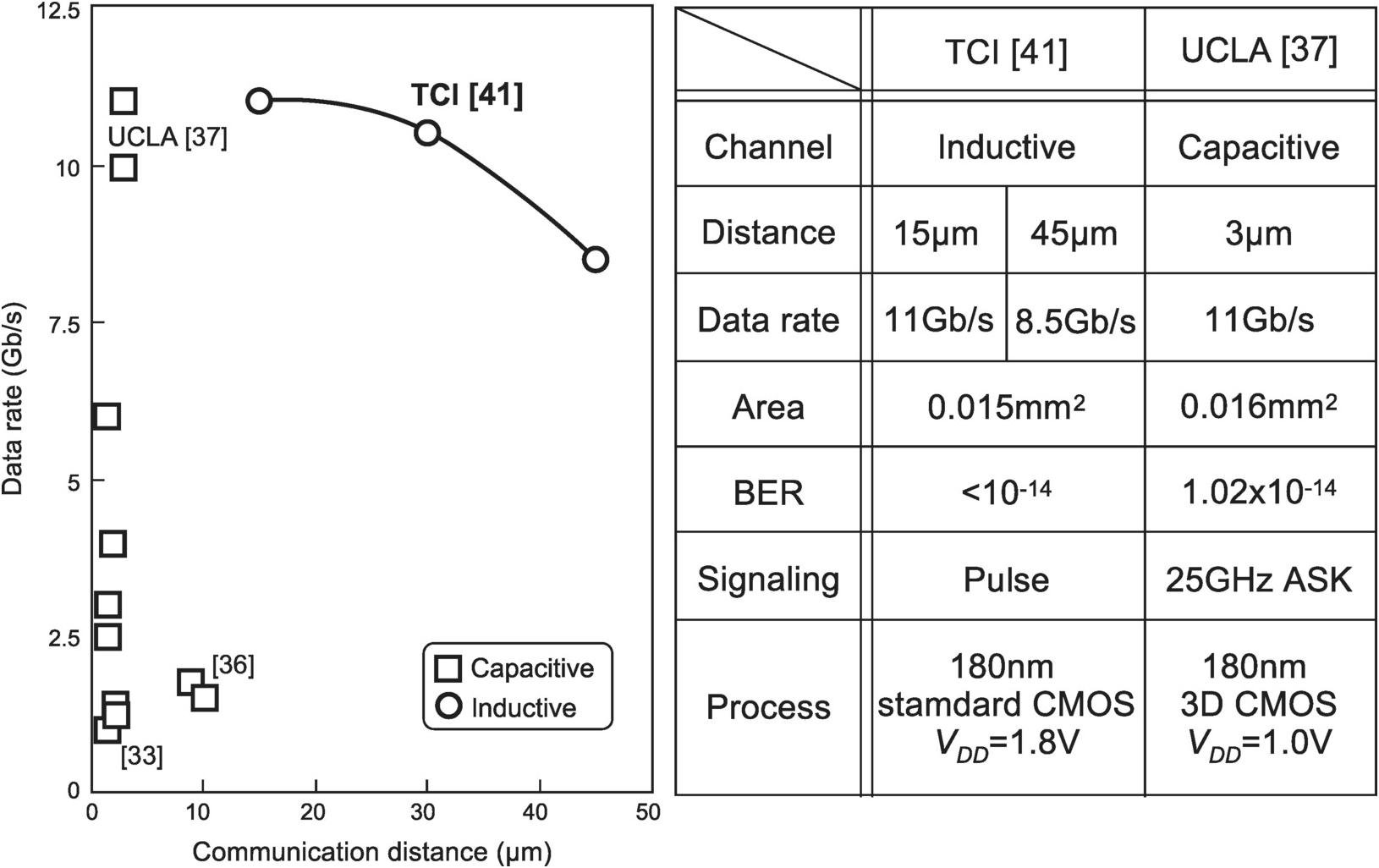

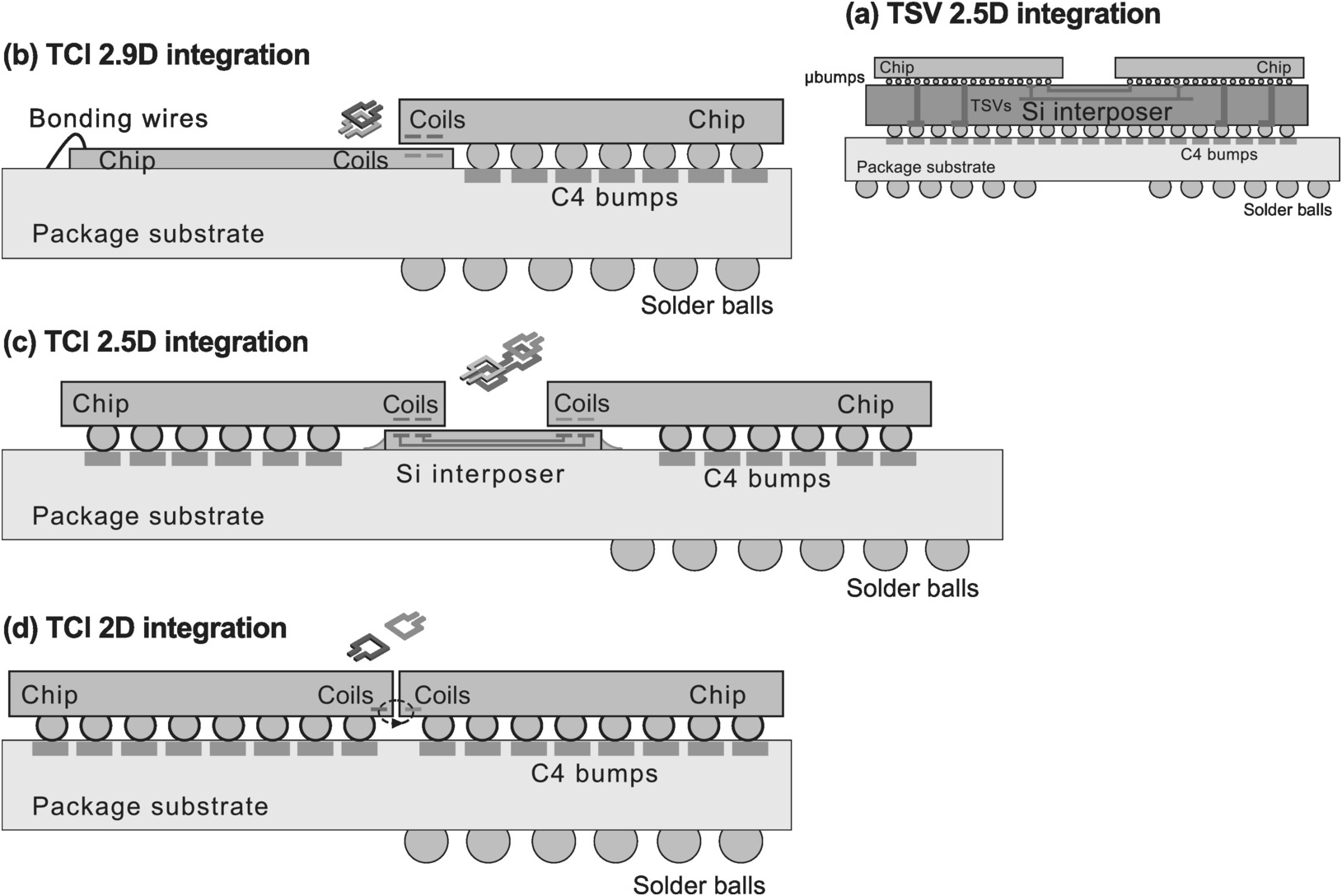

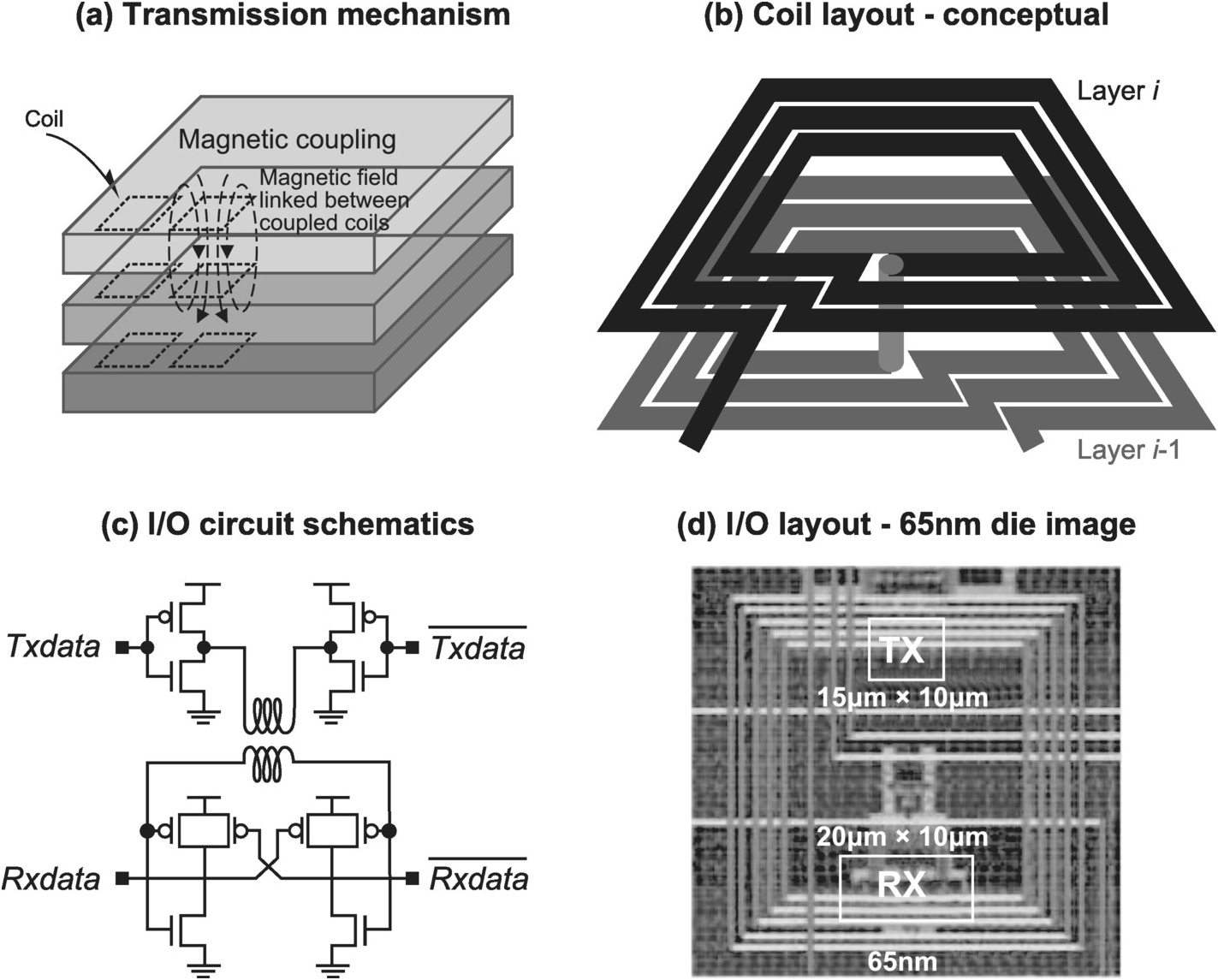

For wireless 3D IC integration, the initial solution proposed uses capacitive coupling [Reference Kanda, Antono, Ishida, Kawaguchi, Kuroda and Sakurai33, Reference Hopkins, Chow, Bosnyak, Coates, Ebergen, Fairbanks, Gainsley, Ho, Lexau, Liu, Ono, Schauer, Sutherland and Drost36–Reference Gu, Xu, Ko and Chang37]. It establishes an electrical connection by aligning connection terminals in the form of metal pads on the surface of the mating chips across a dielectric gap to form a capacitor. Since the impedance of a capacitor is inversely proportional to frequency, this is an alternating current (AC) only connection with no direct physical contact – information is passed through the gap between mating chips by varying the electric field associated with the capacitor. Given that electric field cannot effectively penetrate a silicon substrate, this capacitive coupling solution can only be applied to two chips oriented face to face. Hence, nst = 2. To overcome this and other shortcomings of the capacitive coupling solution, an alternate solution using inductive coupling has been developed that replaces the matching metal pads with matching inductive coils and communicates by changing the magnetic field linked to the coils [Reference Mizoguchi, Yusof, Miura, Sakura and Kuroda34], [Reference Miura, Mizoguchi, Inoue, Tsuji, Sakurai and Kuroda38]–[Reference Miura, Kohama, Sugimori, Ishikuro, Sakurai and Kuroda41].

1.3.4.1 Nature of a TSV

Since electronic circuits are formed on the top surface of an IC, the straightforward way to connect to them is from the front side. Therefore, the natural way to stack more than two dice over each other is to stack all of them facing up and connect the top surface of individual dices to a common point to create interconnections, which is how it is done in a conventional wirebond stack. To enable a drastically different integration scheme, the die must be additionally processed in such a way as to enable its electronic circuits to be connected from the back side as well. Such is the concept of a TSV. It is an electrical connection that traverses the silicon substrate, thereby enabling connection to active circuits of the chip from its back side as well.

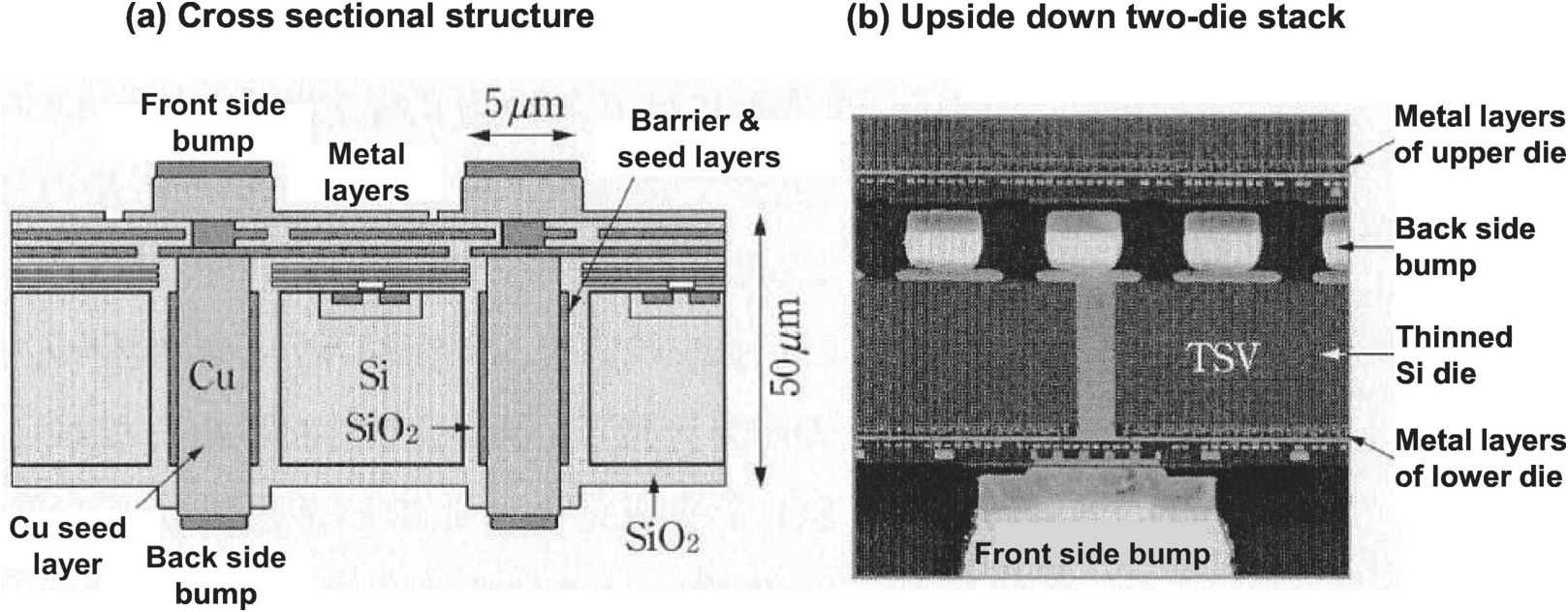

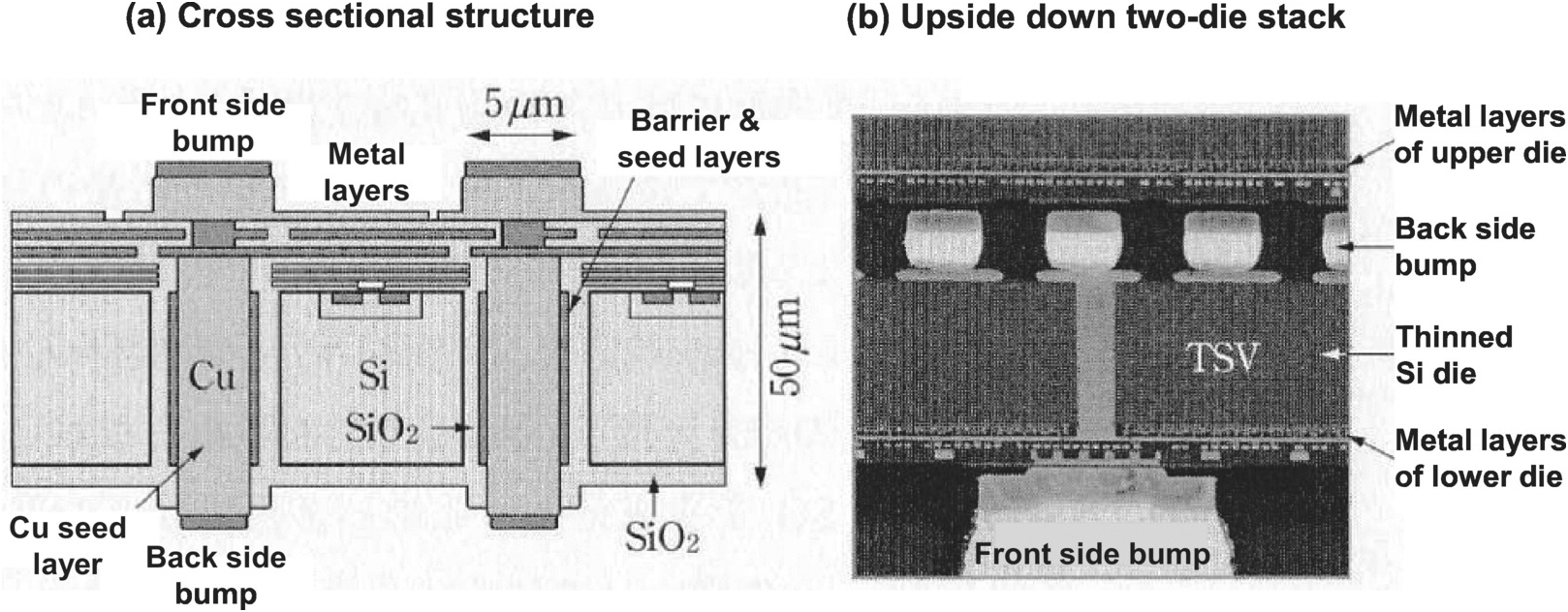

Figure 1.30 depicts the basic structure of a TSV fabricated using one of two commonly employed processes known as a via-middle process [Reference Denda42]. It connects the metal layers on the front side of the die to its back side. A microbump on each of the front and back sides allows the die to connect with an adjacent die above and below respectively. While the die in a single-chip package is generally 200–500 µm thick, for TSV 3D integration it is thinned to about 50 µm. A thinner die helps to keep the stack height low, even if many of them are stacked. But more importantly, it helps to keep the TSV short and hence its diameter small, while maintaining a certain via aspect ratio for manufacturability. A shorter TSV in turn results in a shorter fabrication time. A 50 µm die thickness results in a via diameter between 3 µm and 20 µm, with 5 µm being a typical value. The via wall consist of a SiO2 insulating layer, a barrier layer that is, for example, made of tantalum (Ta), titanium oxide (TiO2), or titanium nitride (TiN) to prevent copper from diffusing into the silicon substrate, as well as a copper seed layer. The copper seed layer serves as an electrode for plating to fill the via with copper, thereby completing the electrical connection from the front to back side of the die. Even with this simplified picture, it is clear that the structure of TSV consists of multiple structural components made of different materials. This has implications in processing complexity as well as yield and reliability due to thermomechanical stresses.

Figure 1.30 Structure of a TSV.

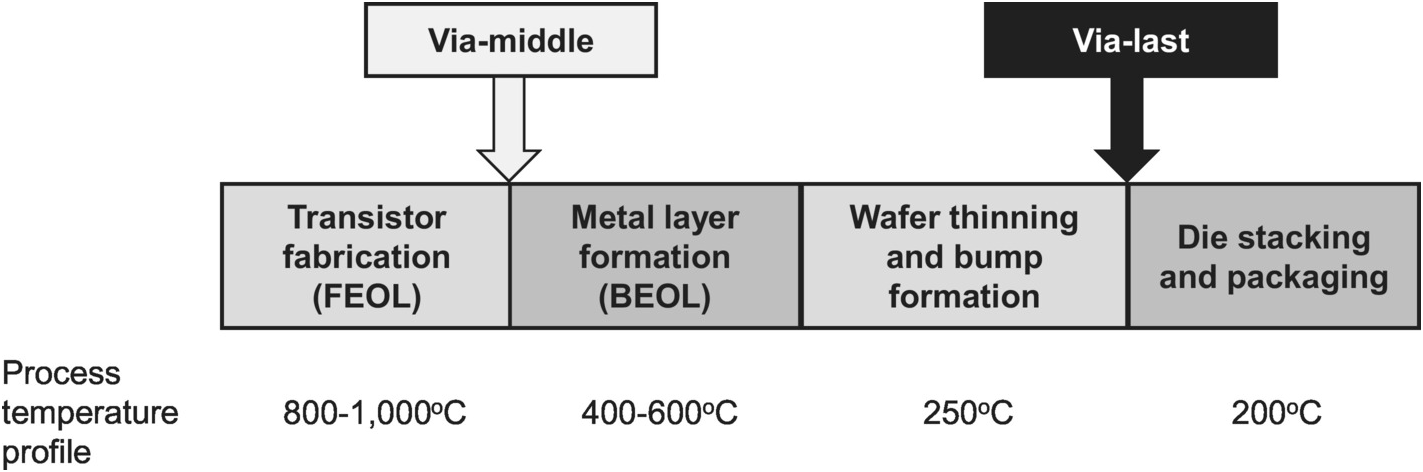

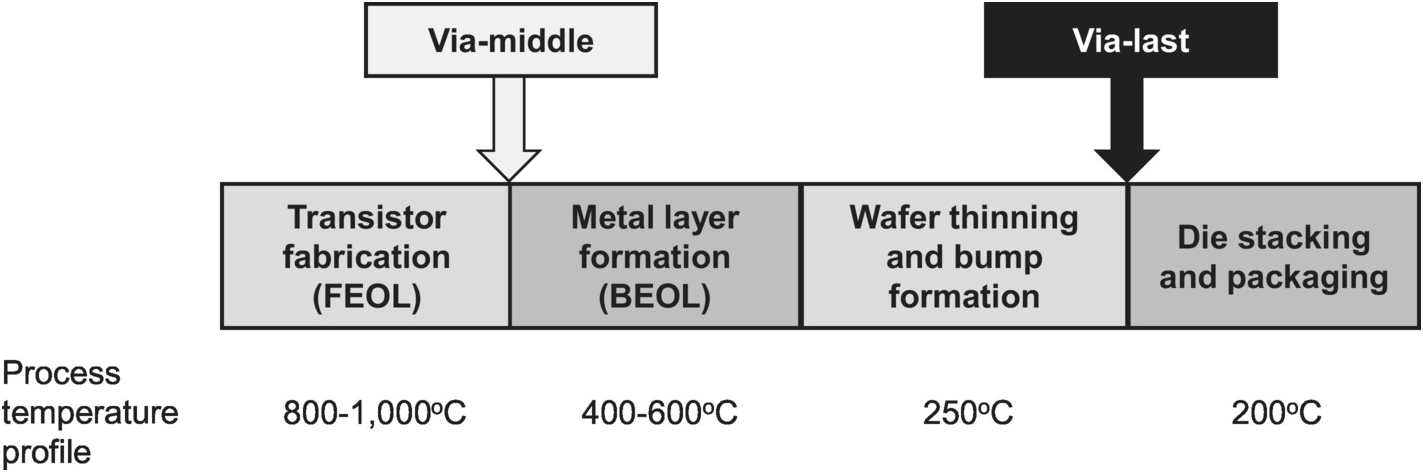

The via-middle process is so named because the TSV formation occurs in the middle of the IC fabrication process, after the front end of line (FEOL) process to create the transistors, but before the back end of line (BEOL) process to form the metal layers. A second common process known as via-last creates the TSVs at the end of the IC fabrication process, after wafer thinning and bump formation. Figure 1.31 depicts where the TSV formation occurs within the IC fabrication flow, including the temperature profiles for each of the fabrication steps. The two TSV processes are different not only because of the different positions within the IC fabrication process flow, but also because of the very different process temperature profiles they are exposed to, resulting in different process complexities and cost and yield equations. Furthermore, for outsourced manufacturing, while the via-middle TSV process falls naturally within the flow of the foundry, the via-last process may occur either at the foundry or outsourced semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) vendor. As a result, the choice of the TSV fabrication process has supply chain implications as well.

Figure 1.31 TSV formation within the IC fabrication process flow.

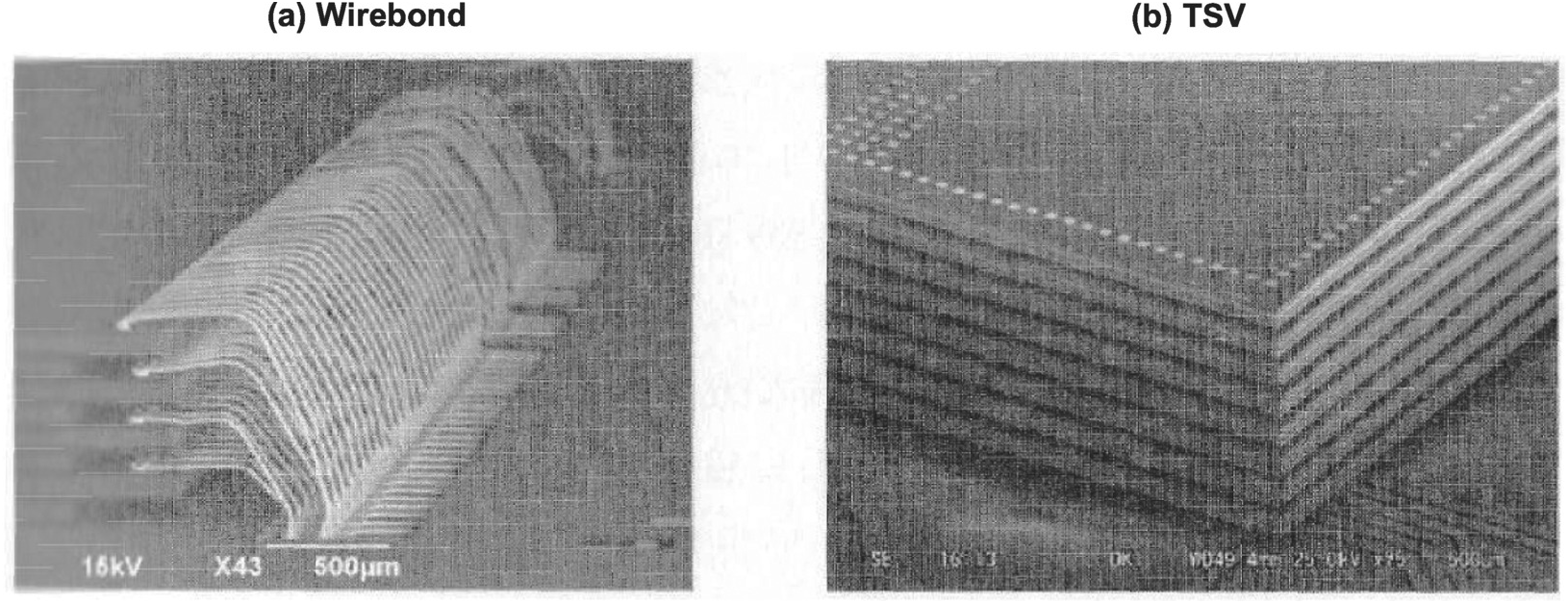

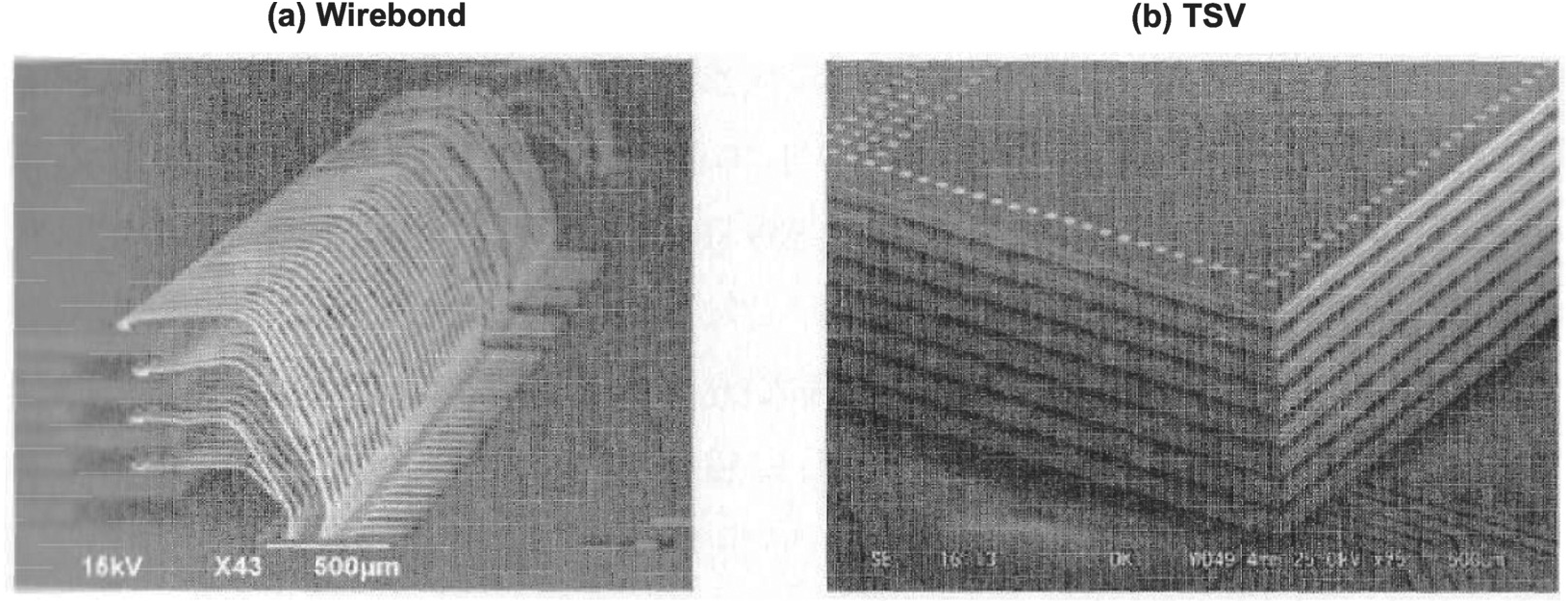

Figure 1.32 contrasts the use of TSV versus wirebond in 3D IC integration. The following key differences can be observed:

TSV enables a smaller form factor: the wirebond stack requires additional area and height to accommodate the wire loops as well as bond pads on the package substrate. Besides, while the example in the figure uses 90 degree rotation of every other die to create clearance for the wire loops, when the dice are square and of the same size, spacers must be inserted between adjacent dice to create such clearance, which increases the stack height further.

TSV enables more robust interconnection: the visual comparison in Figure 1.32 illustrates the contrast in interconnection complexity between the two solutions. While the interconnects in the TSV stack are short and tucked away, those in the wirebond stack are long and susceptible to mechanical force that can tangle them and cause electrical shorts.

TSV enables a larger number of dice to be stacked: in the wirebond stack, the number of wires and their maximum length increase with the number of dice. Therefore, the maximum number of dice in the stack is limited by manufacturability and electrical requirements. Longer wires are more susceptible to sweeping force that can cause electrical shorts. Furthermore, longer wires have higher inductance that can lead to unacceptably large power supply noise and signal degradation, especially at high frequency.

The TSV stack enables a higher interconnect density: while both TSV and wirebond pitch are on the order of 50 µm, TSVs are placed across the surface of the die while wirebonds are limited to its perimeter. Consequently, TSV increases interconnect density in a quadratic manner.

TSV is therefore an advanced technology offering a small form factor, robust, high-capacity stacking, and high interconnect density solution for 3D IC integration.

Figure 1.32 3D IC integration technology comparison: wirebond vs. TSV.

1.3.4.2 TSV for Wired IC Integration

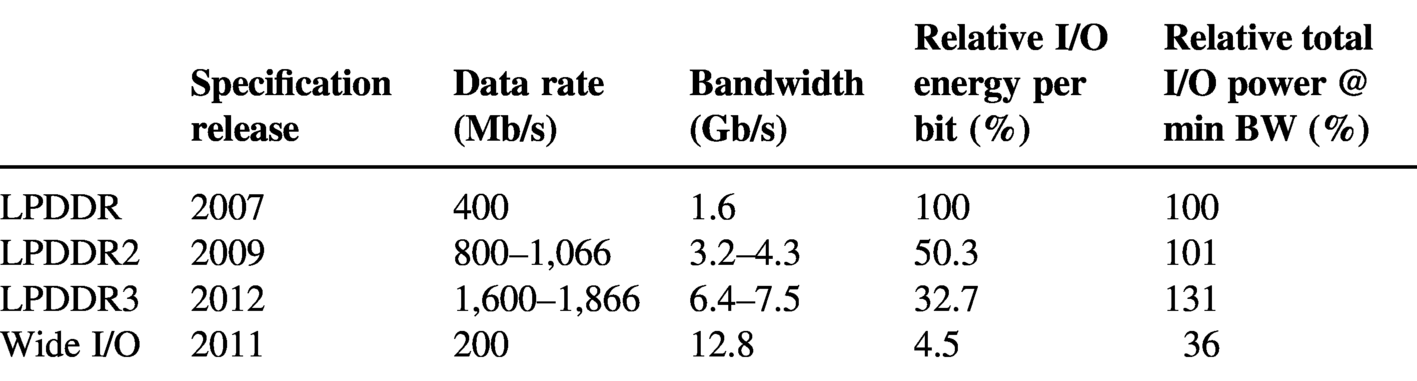

The first industrywide effort to commercialize the application of TSV to wired 3D IC integration was driven by the Joint Electron Device Engineering Council (JEDEC) through its release of the Wide I/O specification in 2011. At the time, the mobile DRAM industry was looking for a solution to deliver a quantum leap in energy efficiency. The transition from the first- to second-generation low-power DRAM technology, LPDDR to LPDDR2, achieved an almost 50% reduction in I/O energy per bit in conjunction with a doubling of bandwidth, resulting in the same total power. However, the next transition achieved only another 35% reduction in energy per bit while the bandwidth again doubled, resulting in a 31% increase in total power. This is summarized in Table 1.4, which is based on data published in [Reference Denda42] and [Reference Kim43]. The continuous increase in data rate demanded by the industry was anticipated to make improvement in energy efficiency more and more difficult as LPDDR evolves. In particular, for the memory interface, higher data rates exacerbate signal integrity problems, including signal reflection, ISI, and crosstalk. Furthermore, skew in delay across LPDDR’s parallel data bus becomes a larger and larger percentage of bit time, especially as the bus width increases to achieve higher bandwidth. Meanwhile, a higher-frequency clock is harder to generate and distribute due to higher jitter, higher sensitivity to noise, and higher attenuation. All these problems require architectural and circuit improvements to solve, such as the use of equalization circuits, transmission line terminations, signal phase alignment circuits, phase locked loop (PLL), delay locked loop (DLL), on-chip power supply bypassing, and insertion of clock buffers that lead to increased power. As a result, the Wide I/O solution was proposed to take low-power memory development in a different direction to enable continuous bandwidth scaling while drastically improving energy efficiency.

Table 1.4. Evolution of mobile DRAM energy efficiency.

| Specification release | Data rate (Mb/s) | Bandwidth (Gb/s) | Relative I/O energy per bit (%) | Relative total I/O power @ min BW (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPDDR | 2007 | 400 | 1.6 | 100 | 100 |

| LPDDR2 | 2009 | 800–1,066 | 3.2–4.3 | 50.3 | 101 |

| LPDDR3 | 2012 | 1,600–1,866 | 6.4–7.5 | 32.7 | 131 |

| Wide I/O | 2011 | 200 | 12.8 | 4.5 | 36 |

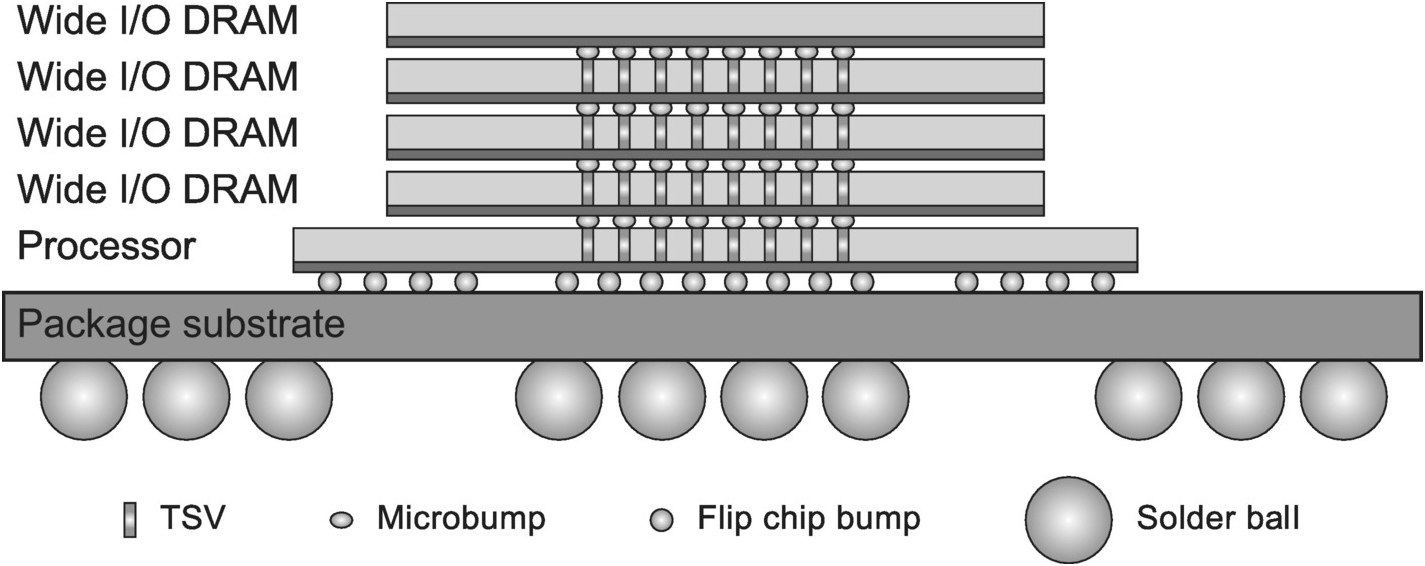

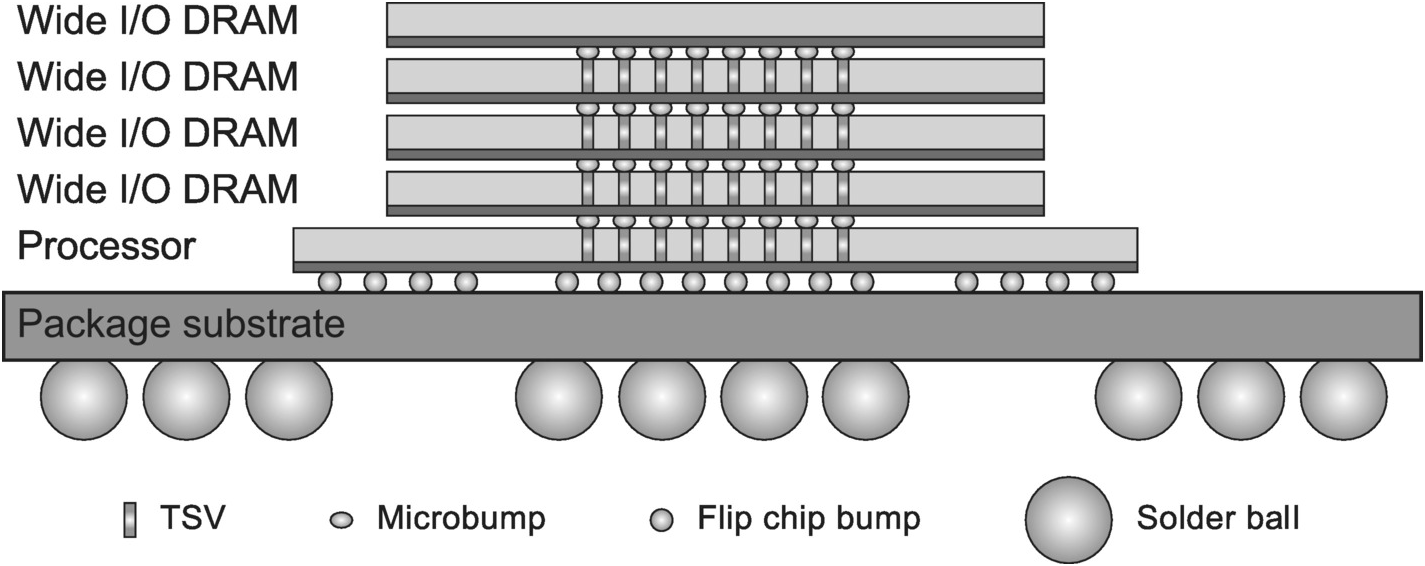

Figure 1.33 depicts the construction of a Wide I/O memory system. It consists of one or more Wide I/O DRAM dice stacked on top of a processor die. The 3D die stack is interconnected with TSVs and microbumps, while the bottom processor die is flip-chip attached to the package substrate.

Figure 1.33 Construction of a Wide I/O memory system.

As the name suggests, Wide I/O adopts a very wide data bus to achieve high bandwidth while keeping the data rate and hence I/O power low. Despite running at ¼ the data rate, it delivers four times the bandwidth of LPDDR2. This is made possible by the use of TSV to enable the 512-bit wide data bus, which is 16 times that of LPDDR2. The use of TSV instead of the conventional PCB interconnect results in drastic reduction in both the interconnect area (5 µm TSV diameter vs. 100 µm PCB trace width) and length (50 µm TSV length vs. tens of mm of PCB trace length), thereby avoiding an order-of-magnitude increase in interface area while significantly reducing interconnect capacitance and transmission line effects. Furthermore, since the interface bypasses the package, the bus width is not limited by the pin count and cost of the package. As a result of the lower data rate and simpler interconnects, the energy per bit is reduced by an order of magnitude while bandwidth is more than tripled compared to LPDDR2 (Table 1.4).

1.3.4.3 2.5D IC Integration Using TSV

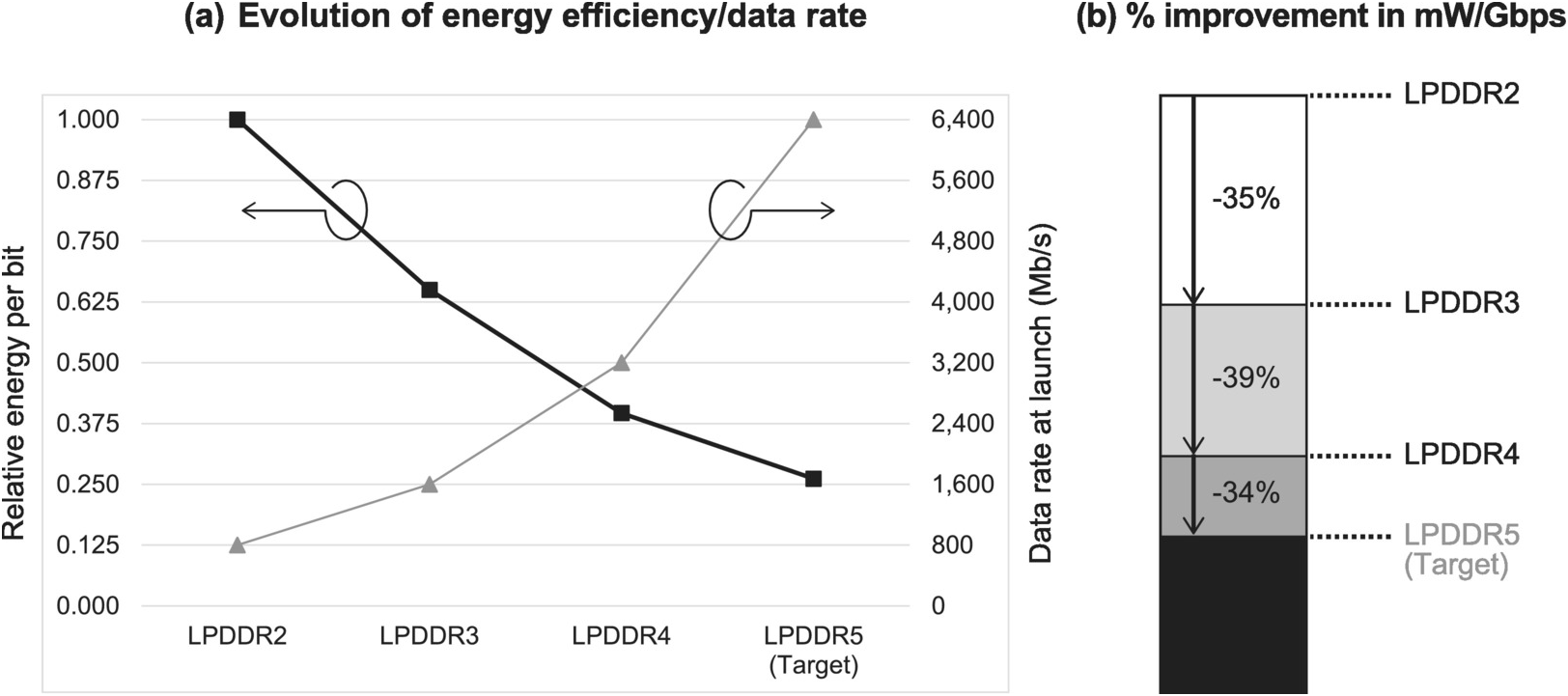

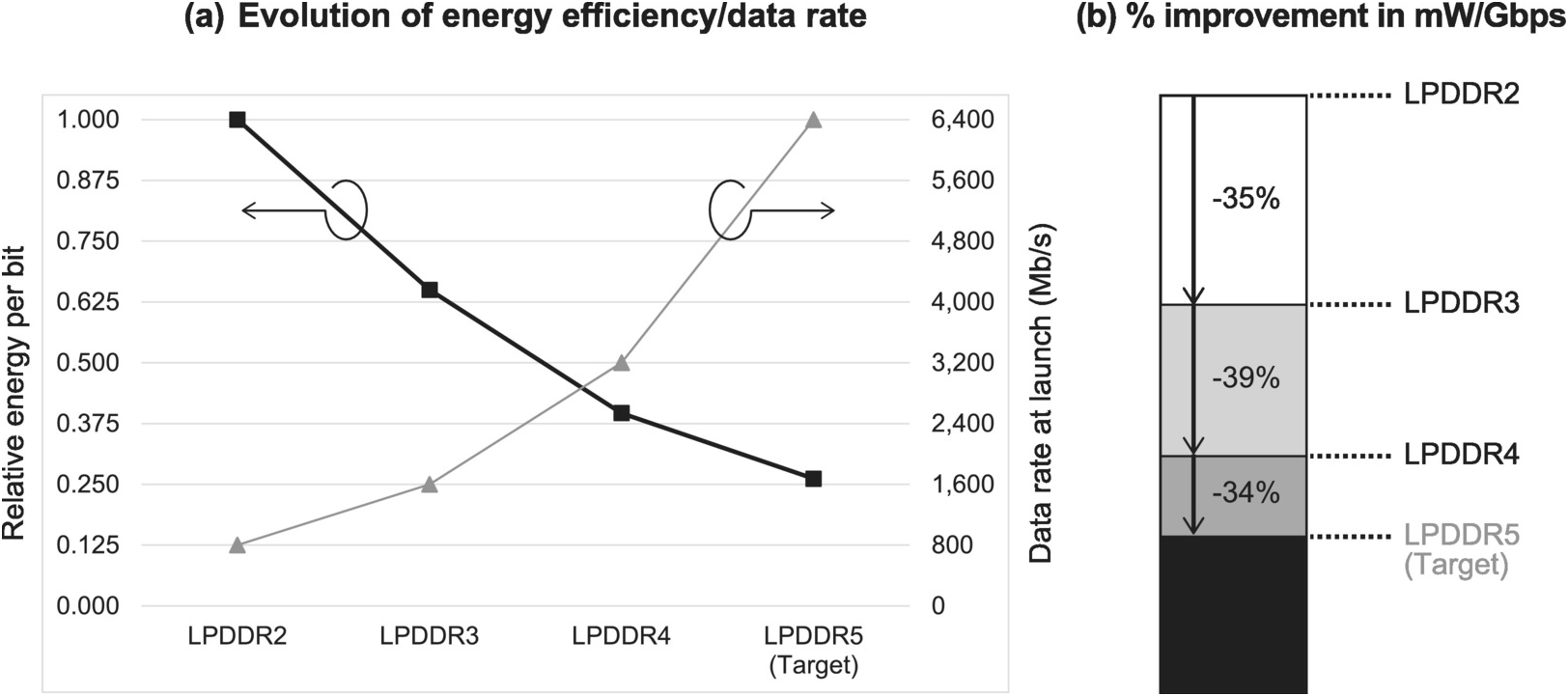

Despite the promise of dramatically improved energy efficiency, Wide I/O (both versions 1 and 2 released in 2011 and 2014 respectively) was not able to replace LPDDR as the low-power memory solution for mobile applications. After the release of the Wide I/O specification, LPDDR continued to evolve from LPDDR3 in 2012 to LPDDR5 in 2019, doubling the data rate in every generation, as shown in Figure 1.34 based on [Reference Kim43]. Meanwhile, energy efficiency improved by about 35% in every generation. This is not sufficient to fully offset the increase in power due to doubling of the data rate, so total memory I/O power goes up at maximum bandwidth. Nevertheless, the industry has so far decided to stay with this evolutionary path, due to challenges in applying TSV to 3D integration of heterogeneous dice.

Figure 1.34 Evolution of LPDDR bandwidth and energy efficiency.

The challenges in applying TSV to 3D integration of heterogeneous dice include added manufacturing cost, yield loss, thermomechanical reliability problems, and device performance degradation. The added manufacturing cost is the result of both added processing for TSV formation and die area overhead. Meanwhile, the complexity of the TSV structure and the multitude of materials used that have diverse coefficients of thermal expansion (CTEs) lead to creation of thermomechanical stresses when the die stack is subject to thermal cycling during both manufacturing and normal operation. Such stresses result in lower manufacturing yield, lower reliability, and semiconductor device performance degradation [Reference Karmarkar, Xu and Moroz44]. Furthermore, thermomechanical stress also occurs at the flip-chip bump interface between the bottom die in the stack and the package substrate below, due to CTE mismatch between silicon and the package substrate material, such as epoxy resin. Such stress exists in single-die packages as well. But the much thinner die in a 3D stack means it is more susceptible to warpage.

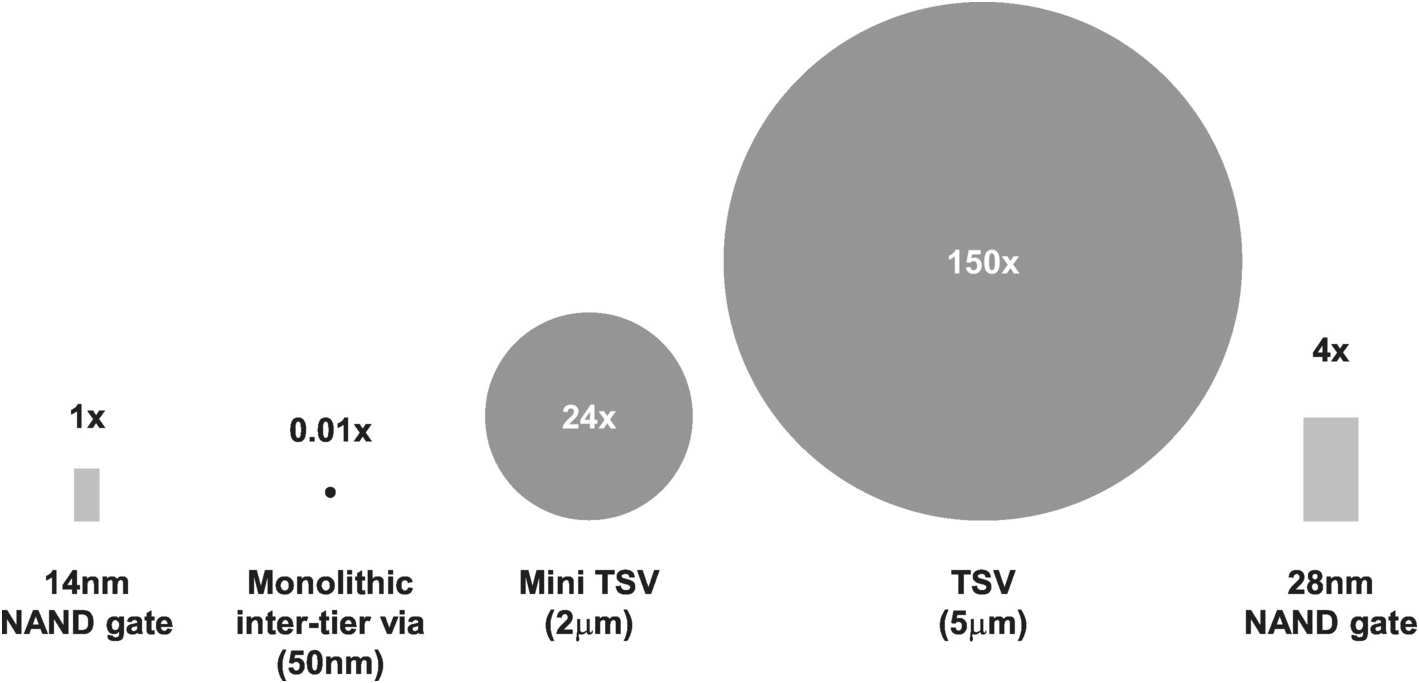

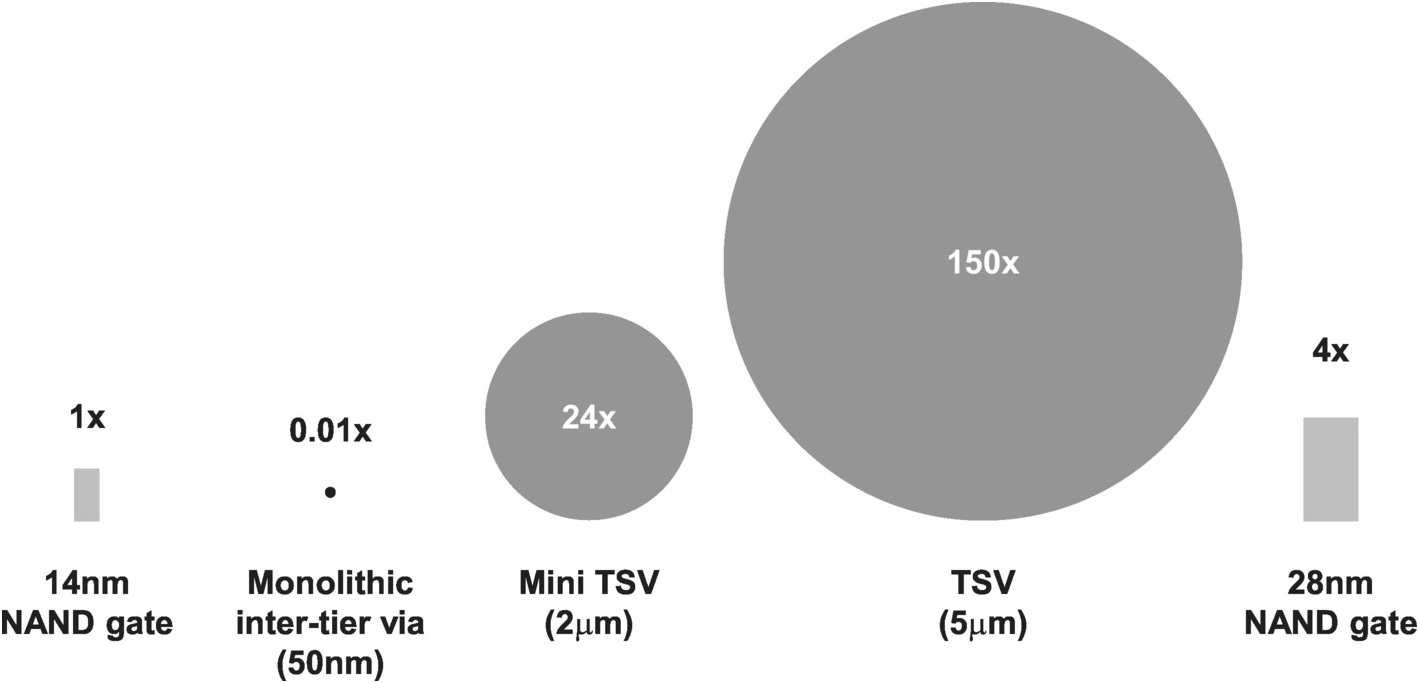

There are solutions to overcome some of these challenges, such as adding redundant TSVs and enlarging the TSV keep-out zone to keep active circuits away. But such solutions increase the already large area overhead. Figure 1.35 depicts a relative size comparison between TSVs and NAND gates. The study in [Reference Samal, Nayak, Ichihashi, Banna and Lim45] from 2016 estimated a die area overhead of almost 40% for a TSV diameter of 5 µm in a 14 nm FinFET process, while noting that practical TSV diameters could be up to 10 µm large.

Figure 1.35 Relative size comparison: TSV vs. NAND gate.

One additional challenge for TSV 3D integration of heterogeneous dice arises when a high-power chip is placed toward the bottom of the stack, which is the case with Wide I/O, where the processor chip sits at the bottom. In this case, heat removal from the high-power chip can be a challenge even if there is a heat sink at the top, especially if there are many chips in the stack.

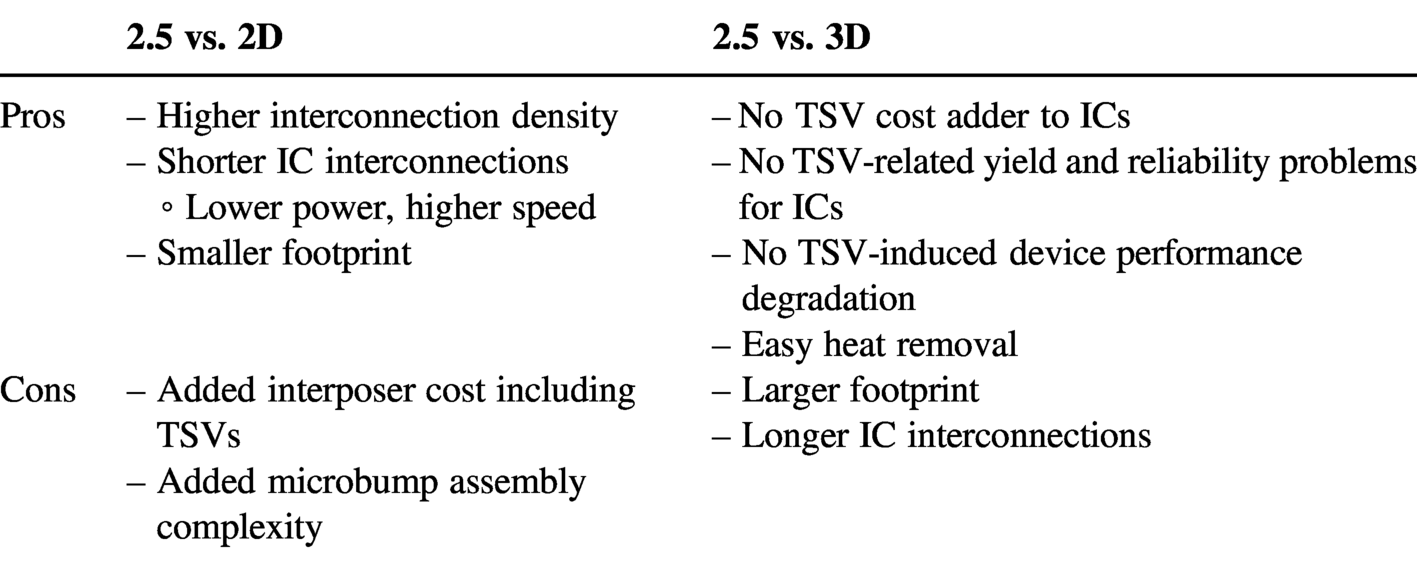

To alleviate these problems, an intermediate solution known as 2.5D IC integration has emerged that has achieved commercial success especially in the high-end FPGA and graphics processing unit (GPU) markets.

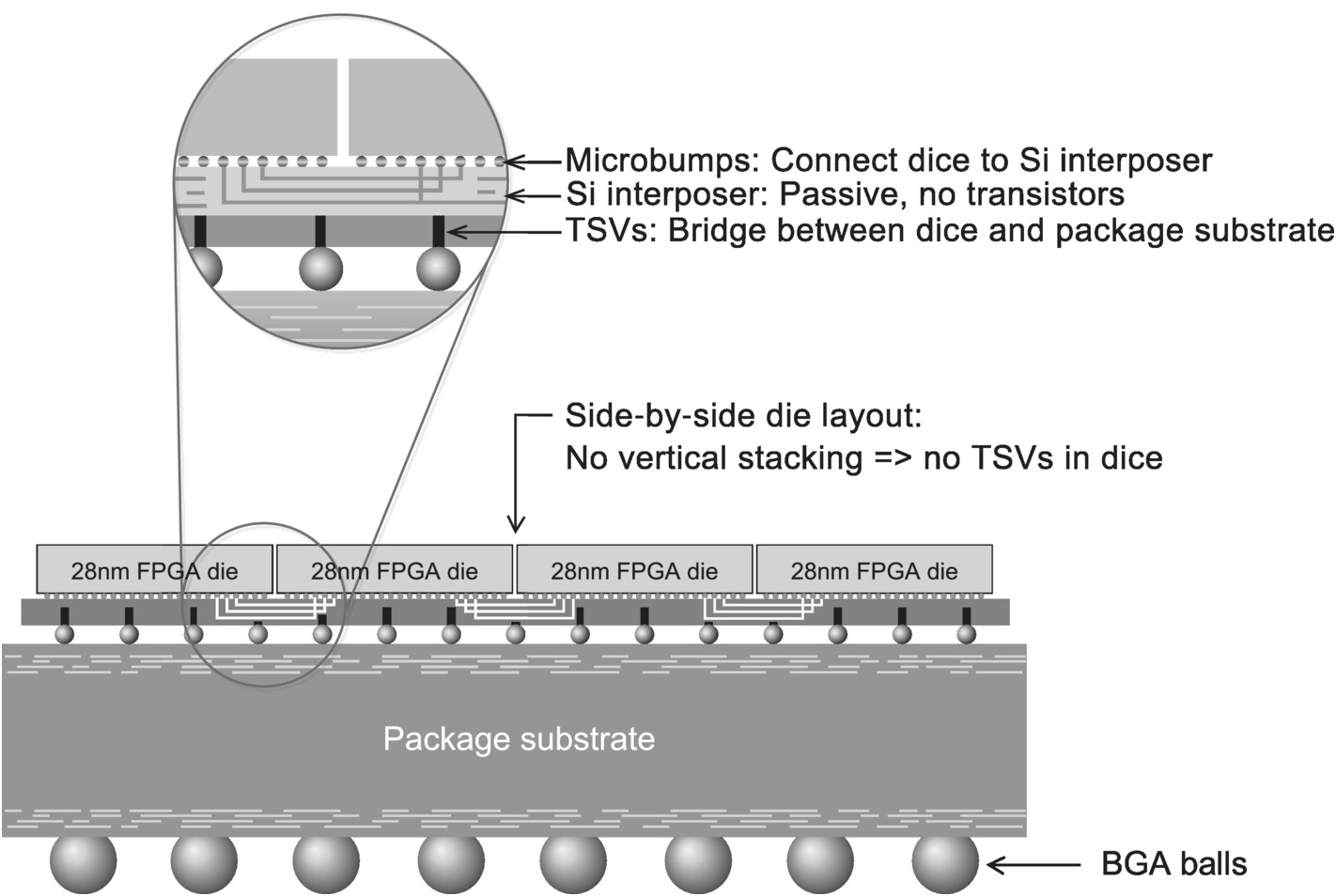

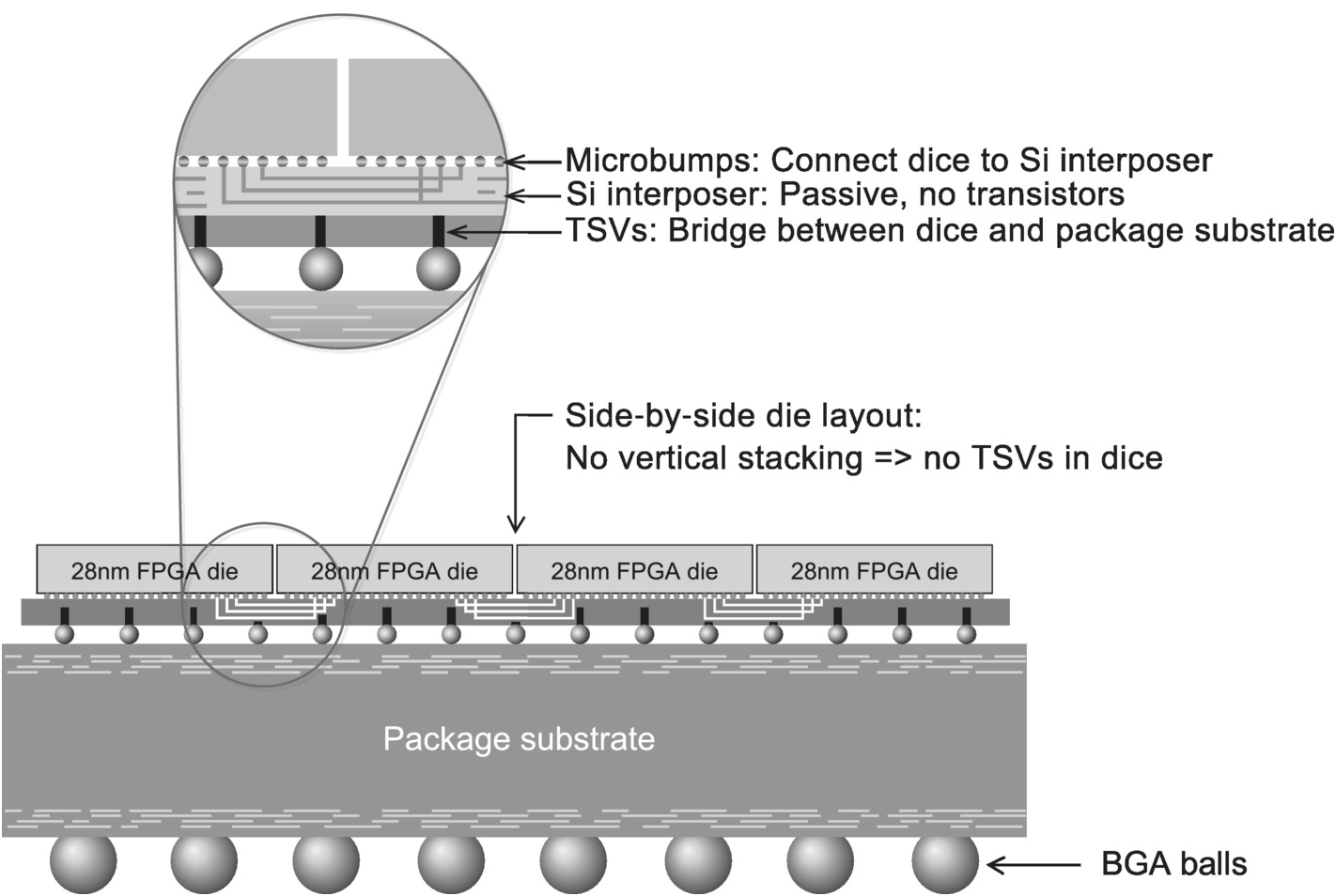

Figure 1.36 depicts the cross section of the first 2.5D integrated FPGA commercial product announced by Xilinx in late 2011 [Reference Bolsens46]. It illustrates the basic construction of a 2.5D IC using TSV. First, the ICs are not stacked and hence have no TSVs. This facilitates heat removal from the individual ICs and eliminates IC manufacturing and reliability problems related to the use of TSV. Second, there is a passive silicon interposer inserted between the ICs and package substrate. The interposer serves the sole purpose of interconnecting the ICs and the package substrate and hence contains no active circuits. Interchip connections consist of microbumps and metal traces only without using TSVs. TSVs in the interposer are only used for power, ground, and external I/Os. Consequently, the TSV density is much lower than in 3D IC integration. As a result, the interposer can be fabricated in a lower-performance, more mature, and hence less expensive process. Furthermore, since the use of TSV is limited to the passive interposer, there is no TSV-induced device performance degradation.

Figure 1.36 Cross section of a 2.5D integrated FPGA.

Figure 1.36 shows an example of homogeneous 2.5D integration where all the chips are of the same type. The same technology can be applied to integration of heterogeneous chips. For instance, in Virtex-7 HT, which is also introduced in [Reference Bolsens46], three FPGA chips are integrated with two 28G SerDes transceiver chips in a 2.5D package. Furthermore, 2.5D can be combined with 3D integration where one of the chips mounted on the silicon interposer is a 3D integrated IC. A representative example is high bandwidth memory (HBM), which is introduced later in this section.

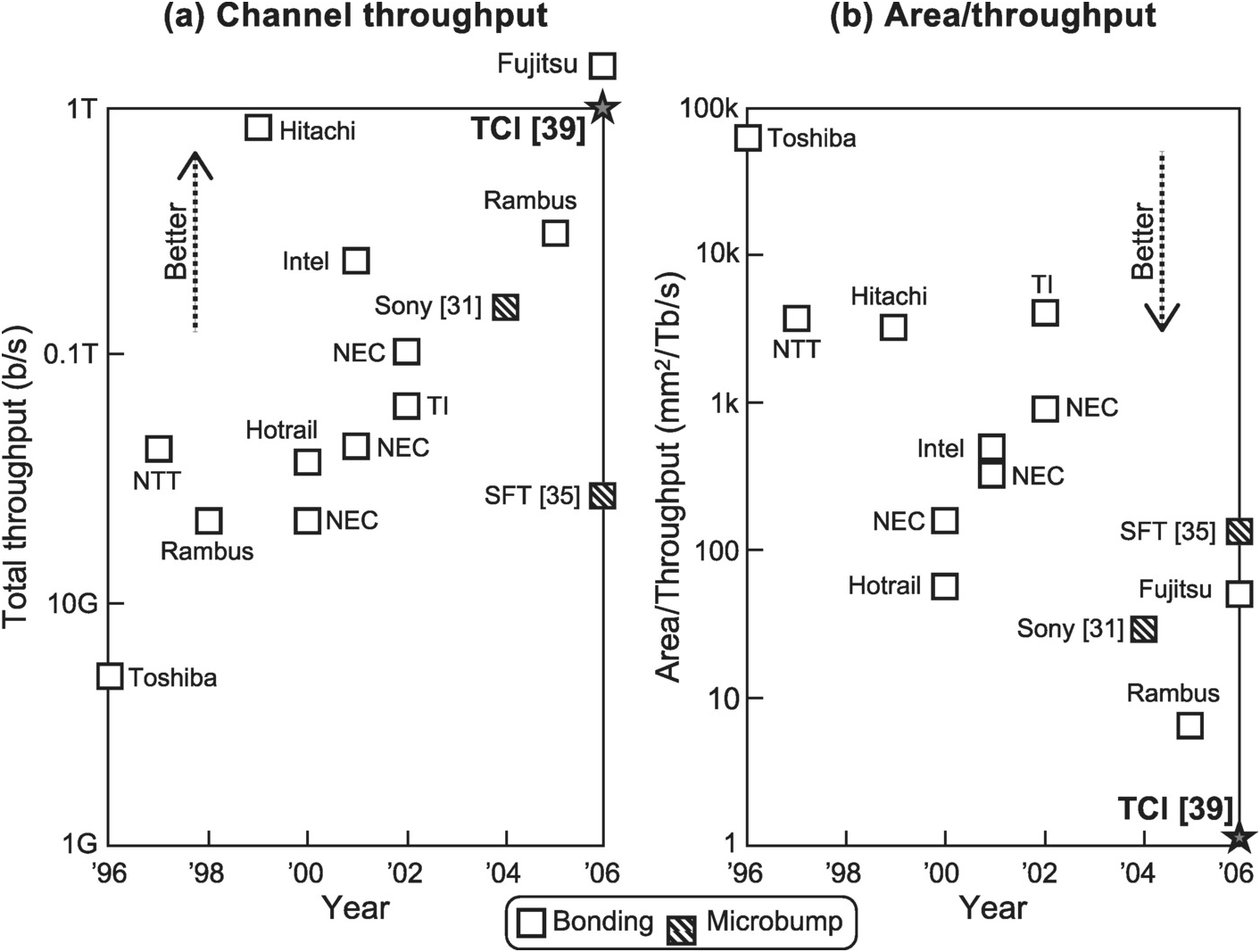

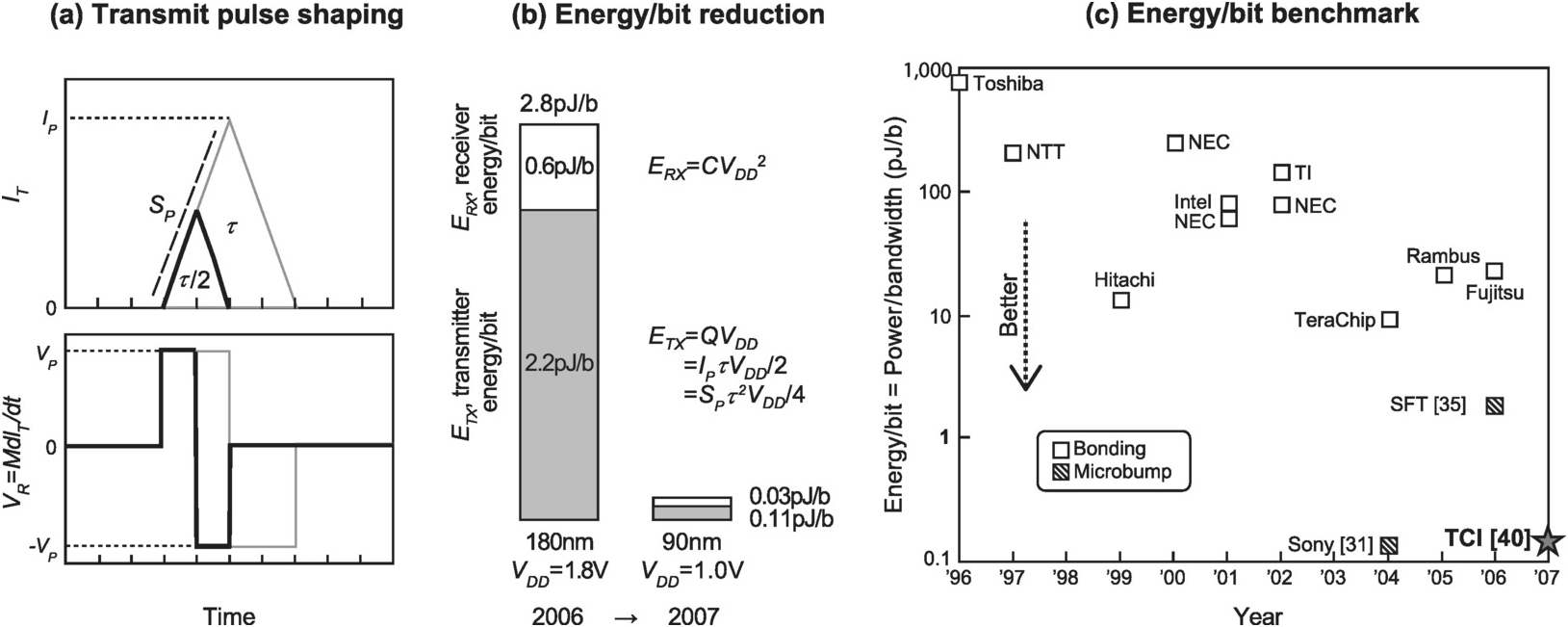

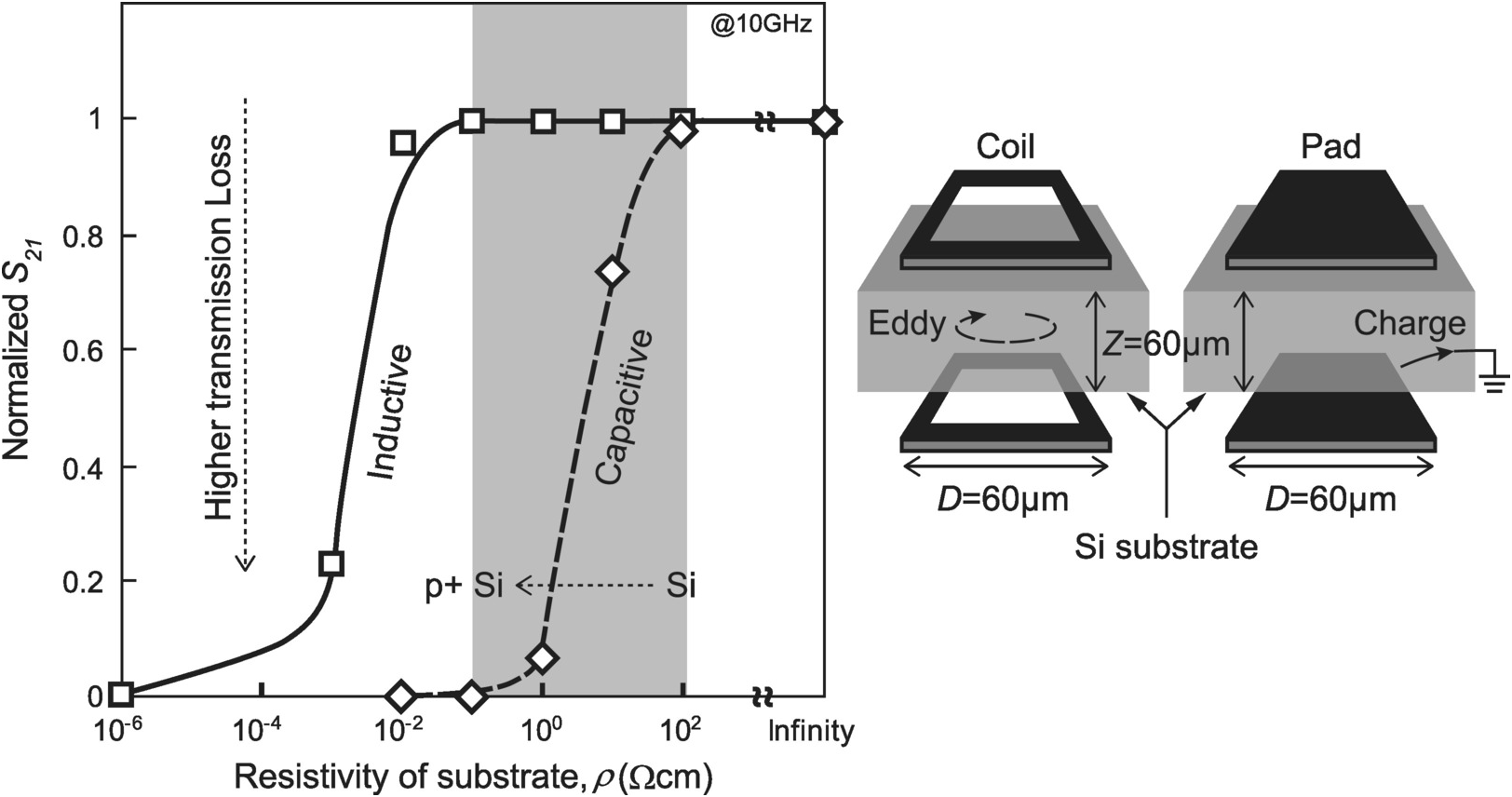

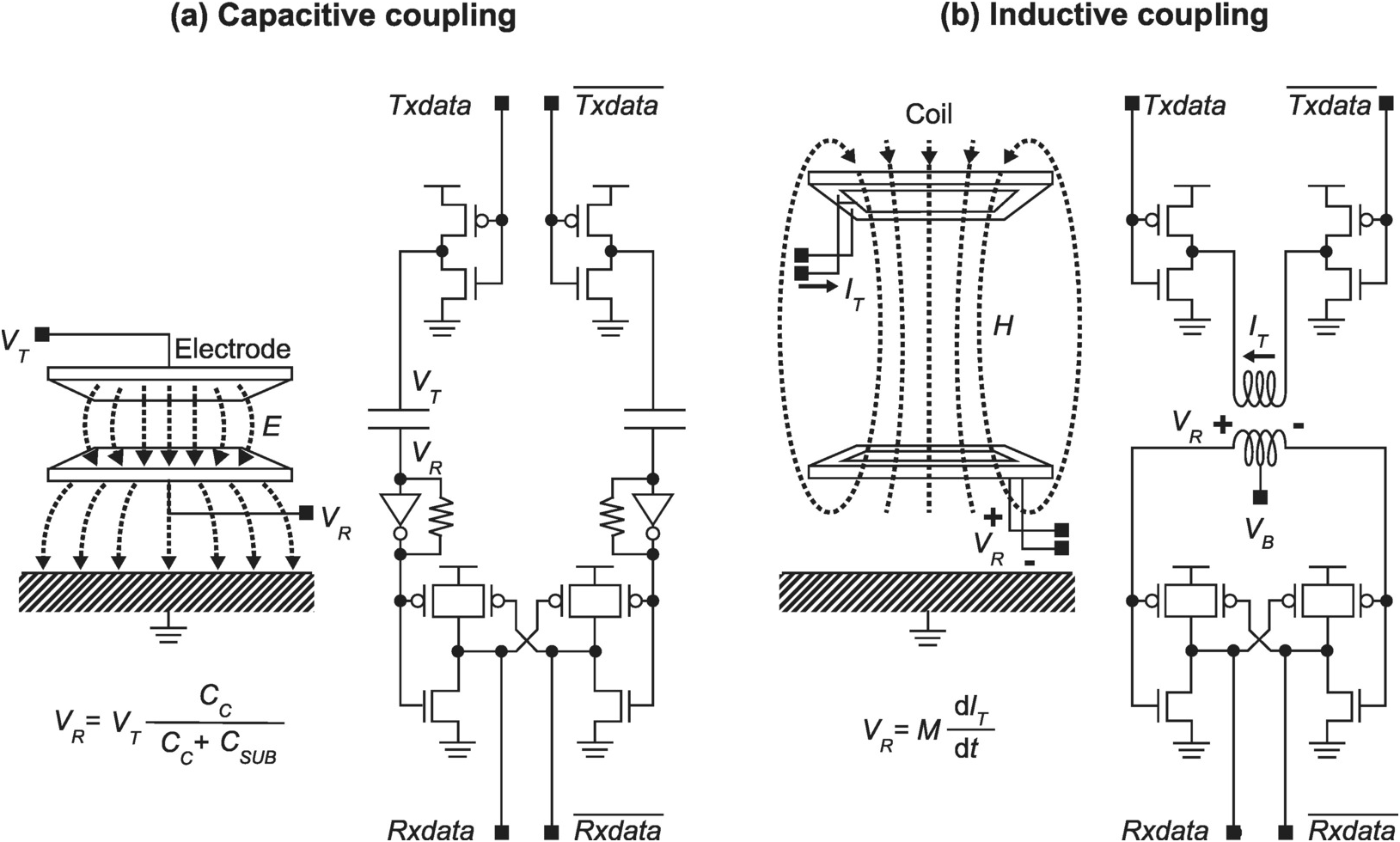

As elaborated in [Reference Bolsens46], compared to 3D, 2.5D integration represents an evolutionary solution in terms of design flow, test, thermal, and reliability. Furthermore, a 2.5D integrated FPGA offers high logic cell capacity at much lower power. As an illustration, the Virtex-7 2000T FPGA from Xilinx is a homogeneous 2.5D integration of four identical 28 nm FPGA chips on top of a 65 nm silicon interposer. It contains a total of 2 million logic cells and about 10,000 connections between adjacent chips and consumes 19 W of power. Using conventional FPGAs, four individually packaged chips will be required to match the capacity, while consuming almost six times the power, with 28.6% consumed by the interconnections.