“There is no problem with stigma- these are inferior persons.”

“Scumbag, trash … this is what happens when you let people breed like rabbits or rats and do not enforce birth control rules.”

In the fall of 1939, Adolf Hitler, with the support of the German medical community, authorized a secret, and now largely forgotten, initiative called the “T-4” program, named after the Berlin address of the program’s coordinating center (Tiergartenstrasse 4). The plan was to perform “euthanasia,” or mercy killings, of persons that the Nazi party considered to be Lebensunwertes Leben, which translates as “life unworthy of life” (another commonly used term was Unnütze Esser or “useless eater.”) These persons were residents of public and private hospitals, psychiatric institutions, and nursing homes who met certain criteria, including persons who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, dementia or other psychiatric and neurological disorders that were considered incurable, people who had been committed on criminal grounds, and anyone who had been at the institution for more than five years. People identified by physicians were then moved to special centers, where they were killed using newly developed poison gas procedures, and their remains disposed of using mass cremation.Reference Scull1 Although the T-4 program was not limited exclusively to people that we would now consider to have severe mental illnesses, it is clear that such individuals made up the bulk of those targeted. Estimates for the total number of persons killed under the T-4 program vary, and range from roughly 80,000 to 250,000.2 It is estimated that roughly three-quarters of Germans with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were killed under the T-4 program.Reference Read, Masson, Read and Dillon3

The T-4 program is historically significant because it predated by roughly two years the much larger Nazi effort to kill derogated ethnic groups, including Jews, Gypsies and others, and it is regarded by many to have been a “dress rehearsal” for this campaign (which we now know of as the Holocaust), since it used essentially the same methods of killing and cremating. In the context of mental health stigma, however, the T-4 program is very important because it can be seen as definitive evidence that negative stereotypes about severe mental illnesses can have powerful social effects when taken to their logical conclusion. The T-4 program was an extreme action, but it stemmed from many of the same negative stereotypes that were widely held at the time and that (to some extent) persist to this day (see quotes at the beginning of this chapter). In fact, as we shall see, the actions of the Nazi state were greatly influenced by ideas that were widely supported in the United States and the United Kingdom prior to World War II.Reference Scull4

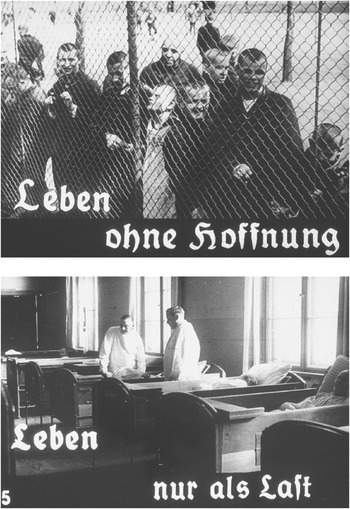

The role of negative stereotypes leading to the T-4 program is evidenced by the logic that the Nazis used to justify their widespread extermination of people with mental illnesses. These were individuals who were believed to be “without hope” of recovery (see Figure 3), hence the belief that the killings met the criteria for euthanasia or “mercy killing.” They represented a “burden” on public resources, and their tainted genes threatened the genetic integrity of the German people.

Figure 3 Photos from a Nazi propaganda film intended to provide support for the T-4 Euthanasia program. The photos show residents of an insane asylum, and the captions translate as “life without hope” and “life only as a burden.”

How did humanity arrive at the point where attitudes toward people diagnosed with mental illness had become so negative that they were considered unworthy of life, and how far have we come since then? This chapter will review what we know about the extent to which mental health stigma has always been a part of human society, how it has changed over time, and what its current status is. It will then discuss some theories about why mental health stigma exists and persists.

Mental Illness and Mental Health Stigma through History

Has severe mental illness existed throughout human history and does it exist in all human societies? A number of historians and cultural anthropologists have been concerned with answering this question. Many of these investigations also provide information on a related question: Are people that exhibit severe mental illnesses always responded to with negative stereotypes and social exclusion/discrimination, and are they responded to in the same way in all human societies? Although sifting through these examinations is a complicated process, I will try to draw some conclusions from an examination of this literature. I will then discuss what we know about why stigma occurs, when it does.

With regard to whether mental illness has always existed, findings from the historical and anthropological literature are clear: As best we can tell, mental illness appears to have existed throughout human history, and it manifests itself in all human societies, regardless of level of industrialization or development. As historian Andrew Scull summarized in his comprehensive review of the history of “madness” in human society (Madness in Civilization), there are descriptions of behavior consistent with mental illness going back to some of the earliest human writings in ancient Israel, Greece, and China. More importantly, as sociologist Allan Horwitz summarized in Social Control of Mental Illness, behaviors that are seen as “incomprehensible” (i.e., that cannot be explained as motivated in some coherent way) are almost always labeled in some way as “mad” or “crazy.”Reference Horwitz5 Moreover, twentieth-century cultural anthropologists who have studied contemporary tribal societies (including aboriginal societies in New Guinea, tribal groups in Nigeria, and native arctic tribes) have consistently found that such groups all have conceptions of, and labels for, behavior that is consistent with the Western idea of mental illness.Reference Murphy6 It should be noted, however, that, in most cases, the labeled behavior is not explained as being the result of a psychological or biological process, but is explained using supernatural conceptions (e.g., that it is the result of magic, a curse, or demon/spirit possession).

Tribal Societies

Although evidence is fairly clear that mental illness exists in all human societies, there is considerably more controversy regarding whether people who exhibit severe mental illnesses are always responded to with negative stereotypes and social exclusion. Beginning with research on tribal societies, anthropological studies of these groups suggest that they tend to take a very supportive and caring stance toward persons demonstrating behavior likely to be related to mental illness. However, for the purpose of this book, the more important question is whether the person is “discredited” as a result of having demonstrated such behavior. Some anthropological studies suggest that, at least in some tribal contexts, people are not discredited when they demonstrate “incomprehensible” behavior. For example, studies of arctic Inuit societies have found that these communities use the word pibloktoq to describe episodes of wild and odd behavior (similar to episodes of mania or psychosis). A study of how people who have exhibited pibloktoq are subsequently treated, however, found that:

an attack of pibloktoq is not automatically taken as a sign of the individual’s general incompetency … The attack may be the subject of good-humored joking later but it is not used to justify restriction of the victim’s social participation. There is, in other words, little or no stigma; the attack is treated as an isolated event rather than as a symptom of deeper illness.Reference Wallace and Hsu7

Similarly, in a study of the Bena tribe in New Guinea, an anthropologist found that, in response to people who experienced negi negi, or episodes of wild and odd behavior: “There is no stigma attached to having such an episode – no public censure – and the occasion is soon forgotten.”Reference Langness8

Despite these examples, there is disagreement regarding whether people who have experienced episodes consistent with mental illness are never discredited in tribal societies. Horwitz concluded that the literature suggests that there is minimal social exclusion of people with mental illnesses in such societies, however, in a review of the literature on this topic, anthropologist Horacio FabregaReference Fabrega9 found mixed evidence for this conclusion, and determined that the extent of stigma depends on both the specific society being studied and the specific types of mental illness behavior being demonstrated. Perhaps one way of making sense of this is to consider that if supernatural explanations are used to explain “incomprehensible” behavior, the extent to which people will be stigmatized depends on the meanings that are attached to the supernatural forces at play. For example, if black magic or spirit possession is invoked, is this the result of mere chance or the fault of some other person who cast a spell, or is it the result of a blameworthy action assumed to have been performed by the possessed person? We can easily imagine how the first explanation could be shrugged off as “bad luck” and have no long-term impact on the possessed person’s reputation, while the second might lead to assumptions that the possessed person is in some way “tainted” for having upset local spirits or dabbled in black magic.

The Ancient World

There is similar controversy when examining evidence for the existence of stigma throughout the history of the major civilizations of Europe, Asia, and Africa (information on the Americas is largely missing). Indeed, there seems to have been some variability in how mental illness was responded to, depending on how its causes were understood. In ancient Greek writings, there is ample discussion of behavior consistent with mental illness, and many of the terms that we use currently to describe psychiatric symptoms (such as mania, melancholia, and phobia) were first used in ancient Greece. The ancient Greeks introduced biological explanations developed by Hippocrates (specifically, that madness resulted from an imbalance of body fluids or “humors”), but primarily saw mad behaviors as resulting from supernatural factors (being cursed by the gods, for example). Although we might expect that demonstrations of madness resulting from the actions of the gods might be seen as temporary and not the fault of the affected person, it appears that the Greeks usually regarded madness to be evidence that the person had done something to deserve being cursed.Reference Scull10 As a result, the response often consisted of many of the reactions that we would now see as consistent with stigma, including ridicule, condemnation, avoidance, and the ritual of spitting upon the sight of the mad person.Reference Fabrega11 For example, an incident that was recorded as occurring in Alexandria indicated that a “lunatic named Carabas … whose madness … was of the easy-going gentler style” was “made game of by the children” and publicly mocked.Reference Rosen12 Similar responses seem to have predominated in ancient Rome.

In ancient Israel, despite the belief in only one God, madness (represented by the still-familiar word meshugga) was also often seen to be the result of a divine curse. And, since the actions of God were believed to always be correct, this meant that the curse was justified because the person had done something to incur God’s punishment. As a result, people who demonstrated “mad” behavior were often mocked and publicly scorned. In addition, Israelite law officially limited the rights of people who were mad, and invalidated marriages where one member was found to be insane.Reference Fabrega13 On the other hand, there appear to have been some mixed feelings about apparently mad behavior, as the “prophets,” important figures in Israeli society, sometimes behaved in a manner that was consistent with madness (the Hebrew word for “to rave” translates as “to behave like a prophet”), but were revered instead of scorned.Reference Rosen14

In ancient China, historians indicate that there was much less discussion of what we now call mental illness and less differentiation of it from physical illness, making our understanding of the extent to which stigma was demonstrated more difficult. Officially, behavior that was incomprehensible was explained as being the result of disequilibrium of internal forces. Nevertheless, historians have concluded that even given these explanations, there is evidence for a high degree of shame regarding madness throughout Chinese history, exacerbated by a belief that a family’s reputation was tainted when it was known that a family member had exhibited mad behavior.Reference Fabrega15 The reasons for the shame are not fully clear, but a plausible explanation is that while the Chinese did not employ the concept of genetics per se, they believed that one’s “lineage” or ancestry was a major contributor to one’s behavior and social value, and the demonstration of madness by a family member could taint the reputation of one’s lineage, as well as pose a specific threat to the marriage prospects of family members.Reference Yang, Purdie-Vaughans, Kotabe, Link, Saw, Wong and Phelan16

The Medieval European and Islamic Worlds

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Christianity dominated European society, but supernatural explanations of what we now call mental illness persisted. Most typically, madness was seen to be the result of demonic possession. However, contrary to what was usually believed by the ancients, possession was not necessarily thought to be the fault of the person who had become possessed. Furthermore, there was a belief that practices such as exorcism could lead to healing or “cure.” As a result, there were a number of saints’ shrines that were believed to be places where madness could be cured. Notably, the shrine of St. Dymphna in Gheel (present day Belgium) became a major pilgrimage destination for families seeking the cure of a “mad” family member, and as a result became a place where the behavior of people considered to be mad was greatly tolerated by the general community.Reference Scull17 Despite the case of Gheel, whether or not what we now call mental illness was widely tolerated in Medieval European society is the subject of debate among historians. French philosopher Michel Foucault, in his book Madness and Civilization,Reference Foucault18 put forth the view that there was widespread tolerance and acceptance of madness in Medieval Europe, but others have disputed this conclusion.Reference Fabrega19 Although it is hard to determine what the true situation was, it might be safe to say that the Medieval Christian perspective at least allowed for the possibility that a person who had demonstrated “mad” behavior could return to a normal social role and therefore not be permanently discredited.

The Medieval Islamic world (which comprised the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Europe) presents an interesting contrast with Christian Europe because physiological interpretations of the causes of mental illness, drawn from the writings of ancient Greek and Roman scholars, became widely accepted. In addition, the teachings of Islam placed a strong emphasis on charity and communal responsibility, and it has been stated that the Quran specifically mandates charity toward the mentally “incompetent.”Footnote a, Reference Youssef and Youssef20 As a result, there is evidence that the Medieval Islamic world was quite “progressive” in its response to mental illness in the sense that people were not blamed for exhibiting signs of madness, there was a belief that families bore a responsibility to patiently care for relatives experiencing episodes, and, in some cases, people were offered treatment in specialized hospital units (the first of their kind in the world). Although it was also believed that demons (or jinn) could cause mental illness, there was not a corollary belief in the value of supernatural healing or exorcism, so this did not factor into the “treatment” that was offered. In an assessment of the degree to which mental illness was stigmatized in the Medieval Islamic world, Fabrega determined that there is evidence that stigma was less of a factor in these than in other societies.Reference Fabrega21

The Early Modern World

A number of important changes in the conceptualization of and treatment toward what we now call mental illness began to take place in the late 1700s, as European and North American society became more secular and government power became more centralized. With regard to conceptualization, the first major factor was that supernatural explanations were no longer favored and biological conceptualizations became preferred. Specifically, the brain and the nervous system began to be seen as the center of thought and emotion, and madness was increasingly seen as a “nervous disorder.” Another major factor was that as society became more urbanized, the poor were increasingly believed to be responsible for their plight, and the publicly “mad,” along with others, were lumped into the category of “subhuman brutes.”Reference Fabrega22 With regard to treatment, the major change was that there was a move toward greater confinement, such that it was believed to be less and less acceptable for the poor and others (including the publicly mad) to “roam freely.” The process of confinement proceeded in a series of stages, beginning with confinement in general poorhouses, jails, and a small number of “madhouses,” and eventually asylums (for a more thorough review of this process, the reader is referred to Scull’s Madness in Civilization).

The “asylum movement” describes the rapid and massive process of confining people deemed to be “insane” in specialized treatment institutions (called asylums) that occurred in the early 1800s throughout the Western world. Asylums were initially developed around the humanistic belief that allowing people who were “insane” to live in an environment that was protected from the stresses of the home and urban, industrialized society would facilitate a recovery from madness.Reference Davidson, Rakfeldt and Strauss23 Treatment was supposed to be strict but humane (the use of shackles and beatings, which had been used in the earlier “madhouses,” was prohibited). In fact, the early asylums reported high “cure” rates of 70% and higher, and “cured” individuals were allowed to return to the community. This suggests that, despite high rates of confinement, the early period of the asylum movement represented a time of greater optimism regarding the potential for people with what we now call mental illness to recover, and therefore less of a complete discrediting of the person.

Nevertheless, the early optimism of the asylum movement deteriorated within a few decades and, by the mid-1800s, asylums were becoming overcrowded and considerably less humane in their treatment approach. Reported cure rates declined and it became increasingly less likely that persons admitted to asylums would be able to return to the community. For example, of the roughly 8,000 people admitted to a large asylum in New York State between 1869 and 1900, less than 20% were ever discharged, with the remainder spending the rest of their lives in the asylum.Reference Penney and Stastny24

Were people who were confined to asylums “discredited”? Evidence from the writings of people who lived in them certainly suggests so. For example, John Clare, a poet who spent 27 years in British asylums in the early 1800s, poignantly wrote:

A later account of the experience of living in an asylum that communicates the “discredited” nature of living in one of these settings is provided in the memoir of Dr. Perry Baird (recovered and transcribed by his daughter), a prominent dermatologist who experienced periodic manic/psychotic episodes. Dr. Baird wrote: “once one has crossed the line from the normal walks of life into a psychopathic hospital, one is separated from friends and relatives by walls thicker than stone; walls of prejudice and superstition … The brutalities that one encounters in state and city psychopathic hospitals must be the by-product of the fear and superstition with which mentally ill patients are regarded.”Reference Baird26

The Rise of Eugenics

Attitudes toward people deemed to be insane took a particularly negative turn in the late 1800s as the idea of “moral degeneracy” (popularized in the work of French psychiatrist Benedict-Augustin Morel) became part of the conventional wisdom in Europe and North America. Essentially, this perspective viewed social ills, including insanity, to be signs of the decay of civilization. New ideas about heritability combined with this view to lead to the belief that insanity was biologically determined, immutable, and a sign of “inferiority.” Although charged with caring for people with mental illness, psychiatrists (or alienists, as they were also called) could be among the most virulent believers that these persons were “tainted” and “defective.” For example, prominent British psychiatrist Henry Maudsley, after whom a major London psychiatric hospital is named, wrote repeatedly about the incurability of insanity and equated it with moral degeneracy and criminality.Reference Scull27

The term “eugenics” was coined by British aristocrat (and cousin of Charles Darwin) Francis Galton in 1883 to describe a moral philosophy to improve human society. Influenced by his cousin’s writings and the belief that human traits were genetically inherited, he proposed that it would be to the betterment of society if people with the “healthiest” traits were encouraged to have more children with each other. The types of traits that most interested Galton were “genius,” “beauty,” “talent,” and “character”; he did not put much of an emphasis on insanity, and experienced at least two “nervous breakdowns” himself (descriptions of them are consistent with the interpretation that he experienced manic episodes).Reference Gillham28 However, his colleague Karl Pearson, after whom a major statistical analytic technique is named, linked “insanity” to degeneracy and bad character, and others were quick to agree.Reference Painter29

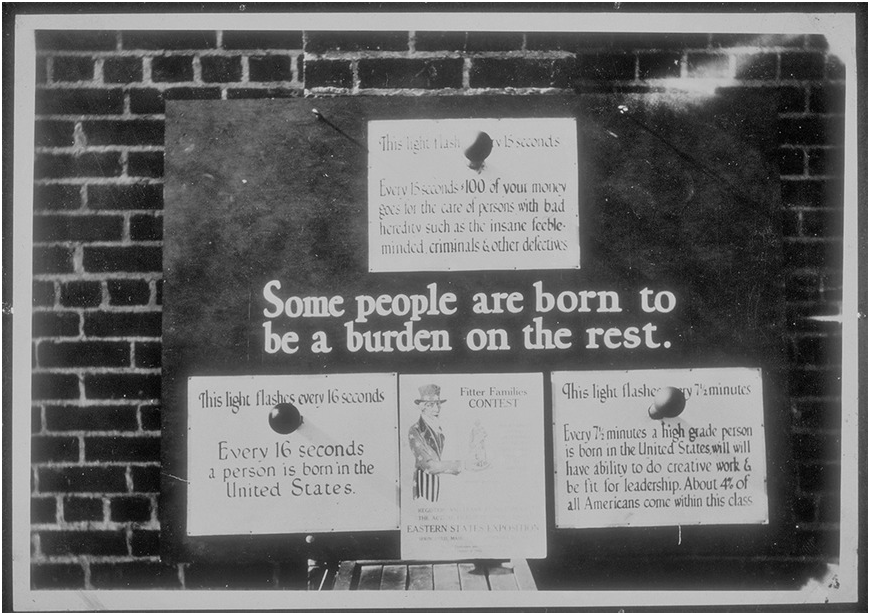

Galton’s ideas soon enjoyed wide support in Britain and especially took off in the United States, where their popularity was probably linked to their appeal in providing “scientific” justification for racist and anti-immigrant sentiment. Rather than just focusing on increasing positive traits, American eugenicists (Charles Davenport and John Harvey Kellogg, of the breakfast cereal company, were two major adherents) also focused on the need to eliminate “defective” inherited traits, including “insanity,” “feeble-mindedness,” and “criminality” (see Figure 4). The American eugenicists also introduced a new idea for reducing the degree to which “defective” traits existed in the human gene-pool: forced sterilization.

Figure 4 American eugenics display used with exhibits and “fitter family” contests, circa 1926. Top sign reads “Every 15 seconds $100 of your money goes for the care of people with bad heredity such as the insane, feeble-minded, criminals & other defectives.”

Lest the reader question how popular these views actually were in the United States in the early twentieth century, the evidence should speak for itself: 40 of 48 states enacted forced sterilization laws (groups that could be sterilized included the “feeble-minded” and “insane”), and roughly 21,000 persons were sterilized by 1935. These laws were upheld by the US Supreme Court in an infamous 1935 decision that has never been officially overturned. Furthermore, America’s forced sterilization laws directly inspired Germany’s new Nazi regime, which created its own sterilization law in 1933 and honored American eugenicist Harry Laughlin at a Heidelberg University ceremony in that year for his pioneering work in the area.30 Germany’s forced sterilization laws were the precursor to the “euthanasia” effort described in the beginning of this chapter.

After World War II

As should be well-known to readers, the end of World War II exposed the horrors of the Holocaust to the world, and it became far less acceptable to espouse eugenic ideas in this period (despite this, forced sterilization continued in some US states until the 1970s, when the last forced sterilization laws were struck down). The 1950s and early 1960s were a time of great change and optimism with regard to the treatment of people with severe mental illnesses, as new medications that might successfully manage symptoms became available (beginning with the discovery of chlorpromazine, commercial name Thorazine, in 1952), and as a gradual reversal of the practice of mass long-term hospitalization began (“deinstitutionalization”).

The extent to which deinstitutionalization was an overall success or failure has been discussed amply by othersReference Lamb and Weinberger31 and is not the focus here; rather, the question is, did the “discrediting” of people who had been diagnosed with a mental illness persist during this transitional period? Two major studies of the American public were conducted in the 1950s that provided some answers to this question. The first, which included more than 3,000 participants, was conducted by Shirley Star at the National Opinion Research Center and was discussed in two presentations given in the 1950s (unfortunately, an official summary of findings was never published).Reference Star and Star32 The second was conducted by Jum Nunnally and used a method called the “semantic differential scale” to gauge the favorability of the public’s opinions toward various groups, including “mental patients.”Reference Nunnally and Kittross33 Summarizing her findings, Star concluded that attitudes toward people with psychotic disorders were generally pessimistic and that the general public largely believed that such individuals were dangerous and/or unpredictable. For example, Star stated that “only a fifth of the American population believes that most psychotics can and do get better again, while two-fifths feel that most can, but don’t.”Reference Star34 She also indicated that roughly two-thirds of the American public “viewed the typical psychotic patient as dangerous” and “feel that all psychotics should be institutionalized.” Furthermore, a summary of Star’s findings in 1961 stated that they indicated that 60% of the American public endorsed that they would “not feel or act normally toward an ex-mental patient.”35 Nunnally’s research was of a smaller scale and only included persons living in Illinois; however, his findings also supported that the public’s perception of “mental patients” was unfavorable, and that the public endorsed the association of such individuals with undesirable characteristics, including unpredictability, weakness, and dangerousness.

These studies led many at the time to conclude that the general public had unfavorable attitudes that needed to be addressed through public education. This fueled several large efforts to educate the public about mental illness and the need for treatment. Many of these efforts were focused on emphasizing that mental illnesses are “diseases like any others” and are not the fault of the people who have them. The 1990s were a period of particular emphasis on educating the general public about the presumed biological origins of mental illness, and were dubbed “the Decade of the Brain” in a 1990 proclamation by President George H. W. Bush. In the proclamation, President Bush expressed a desire “to enhance public awareness of the benefits to be derived from brain research.”36

Where Are We Now?

As a result of public education campaigns, and the “decade of the brain,” the US general public is now much more likely to be exposed to information offering a professional perspective on mental illnesses and their treatment than in the 1950s. For example, in the 2000s, people watching late night television or perusing a general interest magazine might have casually come across an advertisement for Abilify, an antipsychotic medication promoted for its effectiveness in the treatment of depression and bipolar disorder. Are negative stereotypes really that prevalent if advertisements for antipsychotic medications are so commonplace?

Unfortunately, evidence suggests that negative stereotypes about people with severe mental illnesses do persist to a large extent. Focusing on the United States specifically, two studies conducted by researchers Bernice Pescosolido, Bruce Link, Jo Phelan, and others, used data from national US surveys to examine if attitudes had changed over time. The first analysis used a subsample of survey responses from Star’s 1950s survey (described in the previous section) and compared them to 1996 survey findings. Analyses suggested that while the public’s perception of what constituted a mental illness had broadened since the 1950s (and included more nonpsychotic disorders), public perceptions of the dangerousness of people with psychotic disorders had increased.Reference Phelan, Link, Stueve and Pescosolido37 Separate analyses revealed that in 1996, 61% of the American public believed that a hypothetical person with schizophrenia was likely to be violent, and that 63% reported a desire for social distance from this individual.Reference Link, Phelan, Bresnahan, Stueve and Pescosolido38 In a later analysis of change from 1996 to 2006 (after many of the “decade of the brain” public education efforts), the authors found that while the public showed a significant increase in its attribution of the causes of mental illness to neurobiological factors and a belief that treatment was necessary, there was no resultant decrease in expectations of dangerousness or desire for social distance.Reference Pescosolido, Martin, Long, Medina, Phelan and Link39

Things do not look much different if we broaden our perspective beyond the United States. The Stigma in a Global Context – Mental Health Study, which included more than 6,000 participants in 16 countries across six continents, found that in response to a vignette of a person with schizophrenia, there were a core of attitudes that were endorsed at a high level across the countries, including: “likely to be violent to others” (endorsed by 53% on average), “not likely to be productive” (endorsed by 51% on average), “unpredictable” (endorsed by 70% on average), and “shouldn’t care for children” (endorsed by 84% on average).Reference Pescosolido, Medina, Martin and Long40 These findings varied by country, with Iceland showing the lowest endorsement and Cyprus the highest, and with the United States falling somewhere in the middle. Another article reviewed more than 100 studies conducted around the globe regarding attitudes toward people with mental illness and found that while “the majority of the public show pro-social reactions, i.e., they feel sorry for persons with mental illness,” several negative stereotypes were widely held, including the view that people with schizophrenia are unpredictable (endorsement ranged from 54 to 85% depending on the country) and dangerous (endorsement ranged from 18–71% depending on the country).Reference Angermeyer and Dietrich41 There was also an examination of international trends in change with regard to negative stereotypes between the 1990s and 2000s, which confirmed that while “the public’s literacy about mental disorders clearly has increased … at the same time, attitudes towards persons with mental illness have not changed for the better, and have even deteriorated towards persons with schizophrenia.”Reference Schomerus, Schwahn, Holzinger, Corrigan, Grabe, Carta and Angermeyer42

Why have attitudes been resistant to change in the face of the widespread dissemination of information that severe mental illnesses are “diseases like any other”? One interpretation of this finding is that the emphasis on genetics and biology that the “decade of the brain” pushed, partly in an effort to reduce stigma, has backfired. Specifically, analyses from the US surveys suggested that holding the view that mental illnesses are genetically caused “brain diseases” tended to increase the odds that stigmatizing attitudes would be endorsed.Reference Pescosolido43 The authors interpreted this finding to mean that while the general public feels that persons with “brain diseases” are not to blame for their conditions, they are less likely to believe that such persons can get better. Further support for the view that connecting mental illness to “genetics” can increase stigma was found in a separate study conducted by Jo Phelan, which experimentally manipulated whether people were told that the cause of a hypothetical person’s mental illness was genetic or not.Reference Phelan44 This study found that people who were told that the cause of a mental illness was genetic were more likely to think that it was serious and unlikely to change. Another study, employing a similar methodology, found that assigning people to a description linking schizophrenia to genetic explanations was related to both greater desire for social distance and belief in dangerousness, relative to a description of schizophrenia that did not provide a genetic explanation.Reference Lee45 A review of 25 studies on the relationship between the endorsement of “biogenetic” beliefs and stigma also found a similar overall pattern.Reference Kvaale, Gottdiener and Haslam46

There is also evidence that diagnostic labels such as “schizophrenia,” which, as a result of public education efforts, are now strongly linked with notions of genetic causes in the public’s view, may serve as a particular trigger for negative stereotypes. This was supported by an experimental study conducted by German researcher Roland Imhoff, who presented more than 2,000 community members with identical descriptions of an individual experiencing symptoms that met the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, except that a random half of participants were also told that the individual had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, while the others were given no such label.Reference Imhoff47 Imhoff found that participants assigned to the “label” condition were significantly more likely to describe the individual as “dangerous” and less likely to describe him as “competent.” This research challenges the view, which some have articulated, that stigma is only triggered by behavior and not affected by diagnostic labels.Reference Lillienfield, Smith, Watts, Craighead, Miklowitz and Craighead48

The conclusion that emphasizing genetics, biology, and diagnostic labels in an effort to combat stigma is problematic makes particular sense when we consider the history of these concepts in the public discourse about mental illness. As we saw earlier in this chapter (and as articulated in Siddhartha Mukherjee’s best-selling book The Gene), historically, notions of traits being related to genetics have been frequently linked to the idea of essentialism; that is, that certain aspects of a person are inherent and cannot be changed.Reference Mukherjee49 Although scientists know that “the brain” and “genetics” are complicated concepts that do not mean that something is unchangeable, the general public may lack this nuanced understanding. This suggests that different aspects of what we know about mental illness may need to be emphasized in order to reduce stigma.

Where Does Stigma Come from?

We can see from the previous sections that, although the endorsement of negative stereotypes has fluctuated over time and varies by location in the present day, there is evidence that stigma has existed to some extent for a large part of human history and exists currently in almost all human societies. This raises the question of why mental health stigma exists in the first place and why it is so resistant to change.

Origins of Stigma

Mental illness is, of course, not the only social category that is linked to negative stereotypes. In fact, there are a myriad of other human characteristics that are or have been linked to prejudicial notions and associated behavior in various locations, such as racial/ethnic heritage (e.g., African American, Arab-American), religious affiliation (e.g., Catholicism, Judaism, or Islam), sexual orientation, physical characteristics (e.g., deformities or physical disability), and other health conditions (e.g., HIV/AIDS).Reference Major and O’Brien50

Why do people so commonly develop negative assumptions about others that they do not personally know? Social psychologists have proposed that the origins of stigma lie in cognitive processes that are intrinsic to being human. Specifically, in the mid-1950s social psychologist Gordon Allport proposed that stereotyping derives from the cognitive process of categorization, or the tendency for humans to group pieces of information into chunks or categories.Reference Allport51 Categorization facilitates memory and simplifies the task of dealing with the world and other people. When categorizing other people into groups, we are provided with a general framework for interacting with them that can guide our interactions. To give a relatively innocuous example, if we’re babysitting middle school children, we might rely on stereotypes about what such children tend to like, to guide what interests we might try to engage them in (e.g., middle schoolers probably like computer games like Minecraft). Of course, we might be wrong, but we might still want to use these stereotypes for our initial plan of interaction, since there are potentially an unlimited number of interests that middle school children can have, and it would be impractical to try to prepare for all of them.

Certainly, the process of labeling a group and linking certain assumptions to that label is related to categorization, but that does not explain why some human characteristics are stigmatized (meaning that distinctly negative stereotypes are attached to them) while others are not. To address this, Jo Phelan, Bruce Link, and John Dovidio proposed that there are three essential reasons why certain characteristics are stigmatized: (1) exploitation/domination (“keeping people down”), (2) enforcement of social norms (“keeping people in”), and (3) avoidance of disease (“keeping people away”).Reference Phelan, Link and Dovidio52 According to this typology, characteristics become selected for stigma either because they facilitate the maintenance of a power hierarchy, facilitate conformity, or reduce exposure to possibly contagious disease.

Origins of Mental Health Stigma

How does this logic apply to attitudes toward severe mental illnesses? In a further discussion of their typology, Link and Phelan suggested that the initial impetus for mental health stigma is probably a desire to “keep people in.”Reference Link and Phelan53 Specifically, they explained that people with mental illness may often violate social norms when they are actively experiencing symptoms (e.g., think of my description of Jose in Chapter 1, who would wander the streets late at night singing loudly). People react negatively as they try to get the person to conform to how one “should” act (e.g., only singing loudly when it’s culturally sanctioned, such as at concerts, parties, or religious events). Furthermore, in instances where individuals are not responsive to initial efforts to get them to conform, there may be further efforts to keep them “away,” by forcing them to stay in settings (e.g., hospitals or segregated housing sites) where their nonconforming behavior will not disrupt the “normal” social order.

Although Link and Phelan’s typology is a helpful start to understanding where stigma comes from, it does not account for a number of aspects of the mental health stigma process. For example, if the main purpose of stigma is to get people to conform to social norms, why is it that people with severe mental illnesses are “discredited” or “discreditable” even when they are not demonstrating any symptoms that might lead them to violate social norms (recall from Chapter 1 that a key part of the stigma process is that a label that is initially linked to behavior comes to be attached to the person)? Furthermore, why do the negative stereotypes about mental illness center on “dangerous,” “incompetent,” and “unable to recover” rather than “nonconformist” or “weird”?

Another perspective suggests that these specific stereotypes have developed because they have grown from a “grain of truth”; that is, although they may not accurately describe the reality of all or most people with mental illnesses, they are essentially exaggerations of reality.54 This view is consistent with Allport’s initial thinking about why specific stereotypes develop about particular ethnic groups.Reference Allport55 Is there evidence that there is a “grain of truth” to these stereotypes of dangerousness, incompetence, and inability to recover? Many have argued that there is, given that (to focus on the dangerousness stereotype), although research confirms that the great majority (roughly 90%) of people with severe mental illnesses do not engage in violent behavior,Reference Elbogen and Johnson56 there is adequate evidence to support the idea that certain symptoms of mental illness increase the risk for violent or aggressive behavior.Reference Link, Andrews and Cullen57, Footnote b

However, while the “grain of truth” perspective might explain where a given stereotype originates, it does not explain why it is maintained in the face of disconfirming evidence, and why it is held when there is ample evidence that other groups (e.g., in the case of dangerousness, young menReference Corrigan and Watson58, Footnote c) are much more likely to demonstrate the characteristic, yet are not similarly stigmatized. This suggests that there are other factors at play that lead to the maintenance of the stereotype. For this reason, Patrick Corrigan and Amy Watson proposed that a different approach to understanding stigma, called “system-justification,” should be considered.Reference Corrigan, Watson and Ottati59 This approach suggests that we should understand negative stereotypes as coming about in an effort to justify inequities that have arisen for historical reasons. For example, women might be stereotyped as weak and incapable of complex thought to justify their being barred from leadership positions in society (an arrangement that benefits men), while African Americans may have been stereotyped as intellectually inferior to justify slavery and other oppressive institutions. Applying the system-justification perspective to the case of mental health stigma makes some sense when we consider that while the discrediting of people with mental illnesses has existed for a long time, the stereotypes that support it have varied depending on local and historical context. For example, while the current driving-force for stigma is concerns about dangerousness (“Get the Violent Crazies off Our Streets”), the eugenicist and Nazi justifications for stigma made little mention of this, instead focusing on the insane being a “hopeless burden” to society. In this regard, it is plausible that the “second-class citizen” status of people with mental illness, which potentially benefits others in society, is the outcome that these different stereotypes seek to justify. In Chapter 4, we’ll consider further whether and how a focus on negative stereotypes about mental illness might benefit particular groups in society.

Nevertheless, the system-justification perspective runs into problems when we try to use it to explain every aspect of stigma. For example, it seems to be a bit too much of a coincidence for the “system” that stigma supports to have existed in so many different human societies over the course of history. Furthermore, there undeniably are aspects of the behavior that many people with mental illness sometimes engage in when they are actively symptomatic that are genuinely disquieting and frightening to others. Of course, our concern here is why people continue to be “discredited” during the 95%Reference Davidson, Rakfeldt and Strauss60 of their lives when they are not demonstrating any symptoms, but it is plausible that societies have developed some of the negative stereotypes that exist about mental illness as a method of self-protection.Reference Kurzban and Leary61 The fluctuating and episodic nature of mental illnesses may be confusing to others seeking to predict future behavior, so societies may have developed a tendency to apply blanket labels to people with any history of symptomatic behavior as a means of increasing their sense of security. For example, although people with severe mental illnesses are less likely to engage in violent behavior than many other groups in society that are not negatively stereotyped, many community members may feel that they can predict when these other groups are likely to be violent (since it’s more likely to be driven by “comprehensible” motives), and therefore protect themselves from harm. However, an inability to understand the internal motives of people with mental illnesses and therefore predict their behavior may lead community members to be more frightened of them, even though the risk that they pose is actually lower than other groups.

No part of the discussion of the reasons for stigma is intended to excuse people for holding on to stigmatizing attitudes. We do not excuse people for endorsing racist, sexist, or homophobic views even though those prejudices arose for a reason as well. However, it is helpful to form an understanding of the origins of stigma in order to develop a directed plan for combating it. Perhaps there is no single satisfactory explanation for why stigma persists because stigma, like many other issues in human society, is determined by a number of factors. This suggests that efforts to overcome stigma will require a combination of strategies. We will further explore explanations for stigma in Chapter 4 when we consider some of the demographic and personal characteristics that are associated with a greater likelihood that a given individual will endorse stigmatizing attitudes and behavior, and theoretical explanations for those associations, while our focus in the next chapter will be the ways that negative stereotypes impact community members’ behavior toward people with mental illness.