Refine search

Actions for selected content:

23990 results in Ancient history

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020, pp ix-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - During Betrothal

-

- Book:

- Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020, pp 87-108

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index Locorum

-

- Book:

- Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020, pp 307-321

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Breaking a Marital Bond

-

- Book:

- Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020, pp 153-201

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020, pp 322-332

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Discussion and Conclusions

-

- Book:

- Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020, pp 202-218

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Sanctuary at Bath in the Roman Empire

-

- Published online:

- 07 January 2020

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020

Jewish Law and Early Christian Identity

- Betrothal, Marriage, and Infidelity in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian

-

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2020

The Roman Empire in Late Antiquity

- A Political and Military History

-

- Published online:

- 29 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 22 November 2018

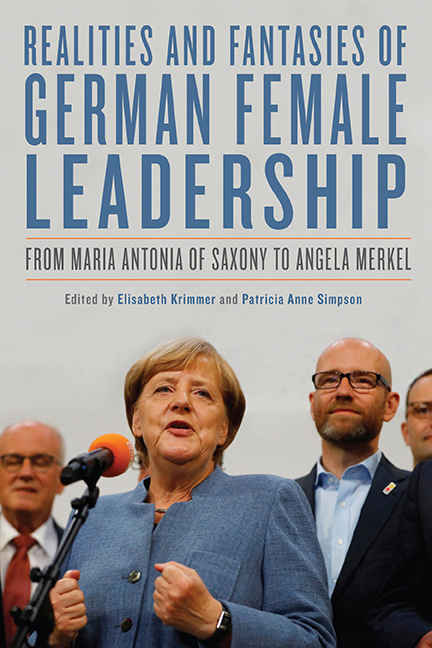

Realities and Fantasies of German Female Leadership

- From Maria Antonia of Saxony to Angela Merkel

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 24 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 01 August 2019

The Films of John Schlesinger

-

- Published by:

- Anthem Press

- Published online:

- 04 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 August 2019

Class and Power in Roman Palestine

- The Socioeconomic Setting of Judaism and Christian Origins

-

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 03 October 2019

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Class and Power in Roman Palestine

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 03 October 2019, pp 261-332

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Appendix C - Palamyra Duties (137 ce)

-

- Book:

- Class and Power in Roman Palestine

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 03 October 2019, pp 259-260

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Class and Power in Roman Palestine

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 03 October 2019, pp 1-15

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Class and Power in Roman Palestine

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 03 October 2019, pp xi-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

CHAPTER 2 - Land Tenancy and Agricultural Labor

-

- Book:

- Class and Power in Roman Palestine

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 03 October 2019, pp 71-110

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Class and Power in Roman Palestine

- Published online:

- 03 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 03 October 2019, pp 249-254

-

- Chapter

- Export citation