Refine search

Actions for selected content:

24576 results in Ancient history

Index of Ancient Sources

-

- Book:

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Published online:

- 02 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2024, pp 300-307

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Plates

-

- Book:

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Published online:

- 02 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2024, pp ix-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Substance and Story

-

- Book:

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Published online:

- 02 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2024, pp 90-127

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Published online:

- 02 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2024, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses

- Published online:

- 02 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 20 June 2024, pp xvii-xix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

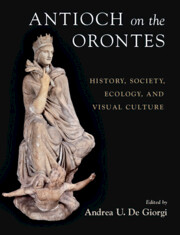

Antioch on the Orontes

- History, Society, Ecology, and Visual Culture

-

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024

Chapter 30 - Memory and the City

- from Part V - Crises and Resilience

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 489-506

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 25 - The Churches of Antioch in the Life of the City

- from Part IV - Religion

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 406-419

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - The Geomorphology of the Greater Antioch Region

- from Part I - Beginnings

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 22-30

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part IV - Religion

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 357-430

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Antioch as a Provincial Capital

- from Part II - The Making of a Capital

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 109-118

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - The People of Antioch

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 245-356

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 24 - Julian in Antioch

- from Part IV - Religion

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 391-405

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp xxi-xxvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Antioch on the Orontes

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 1-6

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Plate Section

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 513-560

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 22 - The First Christians of Antioch

- from Part IV - Religion

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 359-370

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Antioch’s Visual Culture and Its Hellenistic Past

- from Part I - Beginnings

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 89-106

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 23 - Christian Antioch

- from Part IV - Religion

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 371-390

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 27 - Earthquakes and State Response at Antioch

- from Part V - Crises and Resilience

-

-

- Book:

- Antioch on the Orontes

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 433-450

-

- Chapter

- Export citation