Refine search

Actions for selected content:

23990 results in Ancient history

Map - The late Roman world (sites and regions discussed in the text)

-

- Book:

- Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside

- Published online:

- 07 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2011, pp xii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of abbreviations

-

- Book:

- Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside

- Published online:

- 07 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2011, pp xi-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside

- Published online:

- 07 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2011, pp 230-263

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside

- Published online:

- 07 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2011, pp 264-269

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Small politics

-

- Book:

- Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside

- Published online:

- 07 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2011, pp 91-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Power as a competitive exercise

-

- Book:

- Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside

- Published online:

- 07 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2011, pp 121-147

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside

- Published online:

- 07 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2011, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Cornelii Taciti Annalium Libri XIII-XVI

- With Introductions and Notes Abridged from the Larger Work

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 23 June 2011

- First published in:

- 1904

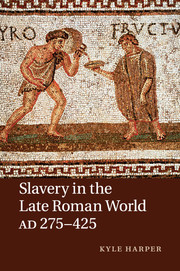

Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 12 May 2011

Die Ssabier und der Ssabismus

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 19 May 2011

- First published in:

- 1856

Cornelii Taciti Annalium, Libri V, VI, XI, XII

- With Introduction and Notes Abridged from the Larger Work

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 10 June 2010

- First published in:

- 1912

Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2010

- First published in:

- 1848

Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2010

- First published in:

- 1841

Ilios

- The City and Country of the Trojans

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 15 July 2010

- First published in:

- 1880

Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2010

- First published in:

- 1851

Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 31 October 2010

- First published in:

- 1849

History and Antiquities of the Doric Race

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 29 July 2010

- First published in:

- 1830

History and Antiquities of the Doric Race

-

- Published online:

- 05 August 2011

- Print publication:

- 29 July 2010

- First published in:

- 1830

27 - Runaways and Quilombolas in the Americas

- from PART VIII - SLAVERY AND RESISTANCE

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge World History of Slavery

- Published online:

- 28 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 July 2011, pp 708-740

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Slavery in Indigenous North America

- from PART III - SLAVERY AMONG THE INDIGENOUS AMERICANS

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge World History of Slavery

- Published online:

- 28 September 2011

- Print publication:

- 25 July 2011, pp 217-247

-

- Chapter

- Export citation