Refine search

Actions for selected content:

60621 results in Classical studies (general)

The Manuscript Tradition of Seneca's Tragedies

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 150-179

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

A New Text of the Logistai Inscription

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 84-94

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Nundinae and The Chronology of the Late Roman Republic

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 189-194

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

On the Halieutica of Oppian

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 60-68

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Some Problems of Text and Interpreation in the Hippolytus

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 11-43

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Manuscript Tradition of Simplicius' Commentary on Aristotle's Physics i-iv

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 70-75

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Trimalchio's Zodiac Dish (Petronius, SAT. 35. 1–5)

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 180-184

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

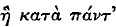

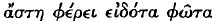

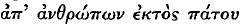

The Text of Parmenides Fr. I. 3

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, p. 69

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

CAQ volume 18 issue 1 Front matter

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. f1-f4

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Phrasal Abundantia in Cicero's Speeches

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 142-149

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

A Note on Odyssey 10. 86

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / May 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 1-3

- Print publication:

- May 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Coins of Abdera - J. M. F. May: The Coinage of Abdera (540–345 B.C.). Pp. xi + 298; plates. London: Spink & Son (for the Royal Numismatic Society), 1966. Cloth, £5. 5s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 99-101

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Italo Mariotti: Aristone di Alessandria. Edizione e interpretazione. Pp. 113. Bologna: Patron, 1966. Cloth.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 110

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Laws of Solon - Eberhard Ruschenbusch: Σ⋯λωνος ν⋯μοι. Die Fragmente des Solonischen Gesetzeswerkes mit einer Text- und Überlieferungsgeschichte. (Historia Einzelschriften, 9.) Pp. ix + 140. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1966. Paper, DM. 30.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 36-38

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Gaetano de Sanctis: Storia dei Romani. Vol. iii, Parte prima: L'età delle guerre puniche. Nuova edizione: Florence: La Nuova Italia, 1967. Paper, L. 5,000.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 121-122

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Aristotle and Platonism - G. E. L. Owen: The Platonism of Aristotle. (British Academy: Dawes Hicks Lecture in Philosophy, 1965.) Pp. 26. London: Oxford University Press. Paper, 5s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 40-41

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Modern Greek: A Scholarly Handbook - George Thomson: A Manual of Modern Greek. Pp. xiv + 112. London: Collet, 1967. Limp cloth, 21s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 102-103

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Pierangelo Catalano: Linee del sistema sovrannazionale romano: i. Pp. xvi + 318. Turin: Giappichelli, 1965. Paper, L. 3,600.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 123-124

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

Africanus Minor - A. E. Astin: Scipio Aemilianus. Pp. xiii + 374. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967. Cloth, 65s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 85-87

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Oxford Helen - A. M. Dale: Euripides, Helen. Edited with Introduction and Commentary. Pp. xxxiv + 179. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967. Cloth, 28s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 1 / March 1968

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 30-33

- Print publication:

- March 1968

-

- Article

- Export citation

at the same time there are some profoundly significant variants in the manuscripts, and it will be argued that the text of 405–12 has suffered from ancient garbling and interpolation. In the following discussion I am everywhere indebted to W. S. Barrett's commentary, whose detailed approach at least draws attention to numerous difficulties that have been hitherto neglected, but the conclusions reached differ radically from his.

at the same time there are some profoundly significant variants in the manuscripts, and it will be argued that the text of 405–12 has suffered from ancient garbling and interpolation. In the following discussion I am everywhere indebted to W. S. Barrett's commentary, whose detailed approach at least draws attention to numerous difficulties that have been hitherto neglected, but the conclusions reached differ radically from his.

). The more percipient critics have realized that

). The more percipient critics have realized that  is difficult or impossible to defend, for it makes no good sense and is incompatible with 1. 27, according to which the way is

is difficult or impossible to defend, for it makes no good sense and is incompatible with 1. 27, according to which the way is  . In fact

. In fact  , which is alleged to be the reading of the best manuscript of Sextus' books

, which is alleged to be the reading of the best manuscript of Sextus' books