Refine search

Actions for selected content:

60621 results in Classical studies (general)

Robert Flacelière: Greek Oracles. Pp. ix + 92; 16 plates. London: Elek Books, 1965. Cloth, 25s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 16 / Issue 2 / June 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 238

- Print publication:

- June 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Three notes on Euripides' Bacchae

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 16 / Issue 2 / June 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 136-138

- Print publication:

- June 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Enclosing Word Order in the Latin Hexameter. I

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 140-171

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Theme of Liberty in the Agricola of Tacitus

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 126-139

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

More Notes on Euripides' Electra

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 51-54

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

A Grasshopper's Diet—Notes on an Epigram of Meleager and a Fragment of Eubulus

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 103-112

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Some Problems of Text and Interpretation in the Bacchae. I

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 27-50

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Porson's Law Extended

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 1-26

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Importance of Δianoia in Plato's Theory of Forms

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 65-69

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

AmΦIΣbhthΣiΣ TiΣ (Aristotle, E.N. 1096b7–26)

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 55-64

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Herodas 4

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 113-125

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Athenian Imperialism and the Foundation of Brea1

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 172-192

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

CAQ volume 16 issue 1 Front matter

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. f1-f4

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Some Manuscripts of Plato's Apologia Socratis

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 70-77

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Aristotle and the Best Kind of Tragedy

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / May 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 78-102

- Print publication:

- May 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Plato, Plotinus, and Origen - John M. Rist: Eros and Psyche: Studies in Plato, Plotinus, and Origen. Pp. xi+238. Toronto: University Press (London: Oxford University Press), 1964. Cloth, 56s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / March 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 84-86

- Print publication:

- March 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Italo Lana, Armando Felon: Antologia della letteratura Latina. I: Dalle origini all'età di Cicerone. Pp. 692. Florence: D'Anna, 1965. Paper, L. 1,700.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / March 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 121

- Print publication:

- March 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Juvenal: Satires. Translated by Jerome Mazzaro with an Introduction and Notes by Richard E. Braun. Pp. [viii]+235. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1965. Cloth, $5.00.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / March 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 118

- Print publication:

- March 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Plautine Cantica - Gregor Maurach: Untersuchungen zum Aufbau plautinischer Lieder. (Hypomnemata, Heft 10.) Pp. 89. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1964. Paper, DM. 16.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / March 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 45-47

- Print publication:

- March 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

Jews in Egypt - V. A. Tcherikover, A. Fuks, M. Stern: Corpus Papyrorum Judaicarum. Vol. iii. xvi+209; 6 plates. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1964. Cloth, 96s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 16 / Issue 1 / March 1966

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 40-42

- Print publication:

- March 1966

-

- Article

- Export citation

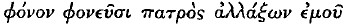

(89). For him to brandish

(89). For him to brandish  at his father's murderers is natural there, where he is delivering a sort of general manifesto as to his aims, and where the strong word

at his father's murderers is natural there, where he is delivering a sort of general manifesto as to his aims, and where the strong word  is justified and alleviated by the jingle with

is justified and alleviated by the jingle with  juxtaposed (‘to requite them murder as they murdered my father’). But there is no reason for Orestes to go on insisting on the bloodthirstiness of these aims, and

juxtaposed (‘to requite them murder as they murdered my father’). But there is no reason for Orestes to go on insisting on the bloodthirstiness of these aims, and  reads oddly in 100, where he is explaining soberly his plan of campaign.

reads oddly in 100, where he is explaining soberly his plan of campaign. ‘can hardly mean “leek” here’ and he assumes it to be ‘groundsel’; Dain in the Budé edition is satisfied with the rather prosaic explanation that it is an ‘observation très juste … la cigale ne se nourrit que des sues des plantes’. I hope to show that the diet of leeks and dewdrops from the mouth is promised by the love-sick swain of Meleager's poem for the same specific reason—to refresh the grasshopper's ‘voice’ for a new day's beguilement by song and persuasion to the sleep which will again free him from the cares of love. Although the ancients were aware of the means by which such insects produced their incessant sound, they remained faithful to the poetic tradition, which made them drink dew as a prelude to their singing, first found in Hesiod,

‘can hardly mean “leek” here’ and he assumes it to be ‘groundsel’; Dain in the Budé edition is satisfied with the rather prosaic explanation that it is an ‘observation très juste … la cigale ne se nourrit que des sues des plantes’. I hope to show that the diet of leeks and dewdrops from the mouth is promised by the love-sick swain of Meleager's poem for the same specific reason—to refresh the grasshopper's ‘voice’ for a new day's beguilement by song and persuasion to the sleep which will again free him from the cares of love. Although the ancients were aware of the means by which such insects produced their incessant sound, they remained faithful to the poetic tradition, which made them drink dew as a prelude to their singing, first found in Hesiod,  : no word can end after a long anceps, except at the caesura in the middle of the line.’ He lists the types of metre to which the rule applies as the stichic iambic trimeters and trochaic tetrameters of the early iambographers and the Attic tragedians, the dactylo-epitrites of Bacchylides, the trochaic trimeters and dimeters of Alcman's

: no word can end after a long anceps, except at the caesura in the middle of the line.’ He lists the types of metre to which the rule applies as the stichic iambic trimeters and trochaic tetrameters of the early iambographers and the Attic tragedians, the dactylo-epitrites of Bacchylides, the trochaic trimeters and dimeters of Alcman's  ) and

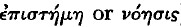

) and  . The first distinguishing characteristic of

. The first distinguishing characteristic of  is that it ‘is compelled to employ assumptions, while knowledge of the Forms tries to advance to a certain first principle’ (510 b 4–9). The second distinguishing characteristic of

is that it ‘is compelled to employ assumptions, while knowledge of the Forms tries to advance to a certain first principle’ (510 b 4–9). The second distinguishing characteristic of  is that it employs the ordinary objects of sense-perception as images (510 d 5–511 a 1). The geometer, in order to find out about ‘

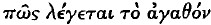

is that it employs the ordinary objects of sense-perception as images (510 d 5–511 a 1). The geometer, in order to find out about ‘ ;—answers different, presumably, to that or those rejected in A.

;—answers different, presumably, to that or those rejected in A.

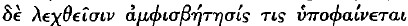

, ‘a controversy can just be seen in what has been said’. These words, referring back to arguments that appear also in E.E., suggest to me that the objection Aristotle is about to discuss is one that had actually been brought against those arguments, after they had been delivered in their Eudemian or some other earlier form, by an opponent who might have belonged to the Academy, but might equally well have belonged to the Lyceum itself. For ease of exposition, I shall in what follows assume this to be the case, and shall refer to the author of the objection as the Objector. This assumption is not, however, essential to the main argument of this article.

, ‘a controversy can just be seen in what has been said’. These words, referring back to arguments that appear also in E.E., suggest to me that the objection Aristotle is about to discuss is one that had actually been brought against those arguments, after they had been delivered in their Eudemian or some other earlier form, by an opponent who might have belonged to the Academy, but might equally well have belonged to the Lyceum itself. For ease of exposition, I shall in what follows assume this to be the case, and shall refer to the author of the objection as the Objector. This assumption is not, however, essential to the main argument of this article. of Herodas is entitled in the papyrus

of Herodas is entitled in the papyrus

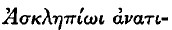

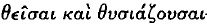

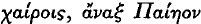

—a title which very well describes the beginning and end of the poem, but disregards the middle, the most important part. The poem divides naturally into sections as follows: (i)1–20a;(2) (i)20b–38, (ii) 39–563, (iii) 56b–78; (3) 79–95.

—a title which very well describes the beginning and end of the poem, but disregards the middle, the most important part. The poem divides naturally into sections as follows: (i)1–20a;(2) (i)20b–38, (ii) 39–563, (iii) 56b–78; (3) 79–95. ) and mention of his dwelling-places (Trikka, Kos, Epidauros), family (parents, Koronis and Apollo;

) and mention of his dwelling-places (Trikka, Kos, Epidauros), family (parents, Koronis and Apollo;