Refine search

Actions for selected content:

60621 results in Classical studies (general)

The Way of Truth

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / May 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 36-41

- Print publication:

- May 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Herodas 6 and 7 1

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / May 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 32-35

- Print publication:

- May 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Zonaras, Syncellus, and Agathias—a Note

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / May 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 82-84

- Print publication:

- May 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Causes and the Outbreak of the Corinthian War 1

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / May 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 64-81

- Print publication:

- May 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Two Notes on Lucretius

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / May 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 94-102

- Print publication:

- May 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Four Notes on Plato's Symposium

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / May 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 42-55

- Print publication:

- May 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

CAQ volume 14 issue 1 Front matter

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / May 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. f1-f4

- Print publication:

- May 1964

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Juvenal 1.149 and 10.106–7

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Quarterly / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / May 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2009, pp. 103-108

- Print publication:

- May 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Opuscula Romana, iv (Skr. utg. av Svenska Institutet i Rom.) Pp. 248; 35 plates, 91 figs. Lund: Gleerup, 1962. Paper, kr. 90.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 120-121

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Gaius and Egyptian Cults - Ernst Köberlein: Caligula und die ägyptischen Kulte. (Beiträge zur Klassischen Philologie, 3.) Pp. 87; 1 plate. Meisenheim (Glan): Anton Hain, 1962. Paper, DM. 12.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 91-92

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Lars Elfving: Étude lexicographique sur les séquences limousines. (Studia Latina Stockholmensia, vii.) Pp. 283. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1962. Paper, kr. 28.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 112-113

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Books Received

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 122-125

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Persian Invasions - Charles Hignett: Xerxes' Invasion of Greece. Pp. xv+496; 8 maps text. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963. 63s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 83-85

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Latin Words in -Men and -Mentvm - Jean Perrot: Les dérivés latins en -men et -mentum. (Études et Commentaires, xxxvii.) Pp. 382. Paris: Klincksieck, 1961. Paper, 40 fr.1

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 63-65

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Franz-Norbert Klein: Die Licht-terminologie bei Philon von Alexandrien und in den Hermetischen Schriften. Untersuchungen zur Struktur der religiösen Sprache der hellenistischen Mystik. Pp. x+232. Leiden: Brill, 1962. Cloth, fl. 22.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 115

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Angelo Procopiou: The Macedonian Question in Byzantine Painting. Pp. 47; 64 plates. Athens (distributed by Parker & Son, Oxford), 1962. Cloth, 40s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 119

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

A Roman Officer in Egypt - H. I. Bell, V. Martin, E. G. Turner, D. van Berchem: The Abinnaeus Archive: Papers of a Roman Officer in the Reign of Constantius II. Pp. xiv+ 191. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962. Cloth, 63s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 102-103

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Tragic Symposium - Le Théâtre tragique. Études réunies et présentées parJean Jacquot. Pp. 539. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (Service des Publications), 1962. Boards, 46 fr.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 22-23

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

R. E. Wycherley: How the Greeks built Cities. Second Edition. Pp. xxi+235; 16 plates, 52 figs. London: Macmillan, 1962. Cloth, 25s. net.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, p. 117

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

Virgil and the Golden Section - George E. Duckworth: Structural Patterns and Proportions in Vergil's Aeneid. Pp. x+268. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1962. Cloth, $7.50.

-

- Journal:

- The Classical Review / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / March 1964

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2009, pp. 43-45

- Print publication:

- March 1964

-

- Article

- Export citation

The first stage of this proof is contained in B 2.

The first stage of this proof is contained in B 2. (i.e. an unqualified yes; an unqualified no; and a noncommittal answer that some- times we must say yes, sometimes no) and rule out two of them. This view involves giving equal status to each of the two wrong answers; but Parmenides appears not to do this. At the start of B 2 he undertakes to tell us

(i.e. an unqualified yes; an unqualified no; and a noncommittal answer that some- times we must say yes, sometimes no) and rule out two of them. This view involves giving equal status to each of the two wrong answers; but Parmenides appears not to do this. At the start of B 2 he undertakes to tell us

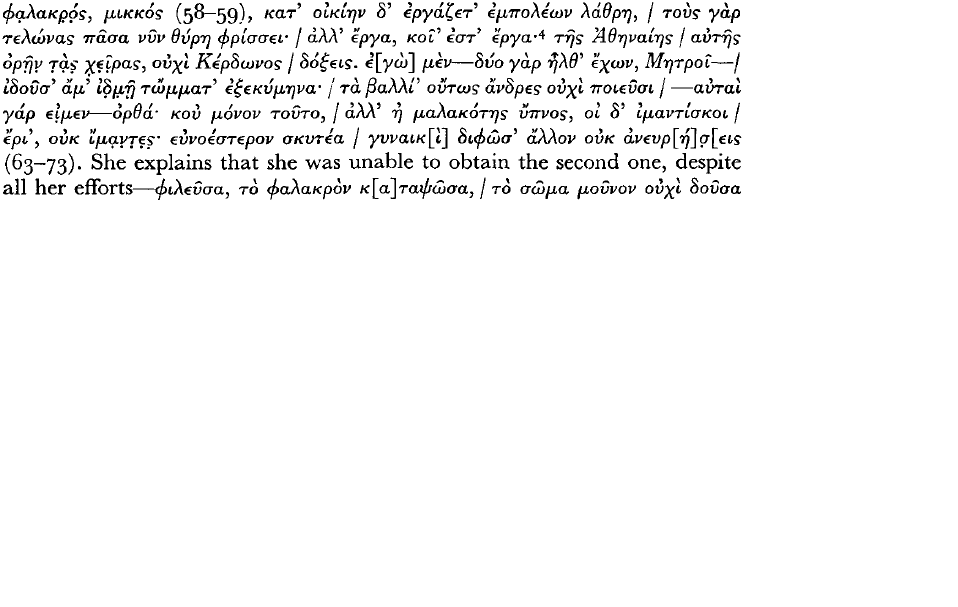

(18–19). Coritto is furious that knowledge of this precious possession has spread so far, and without answering the question asks where Coritto saw it: the reply is,

(18–19). Coritto is furious that knowledge of this precious possession has spread so far, and without answering the question asks where Coritto saw it: the reply is,  (20–21). Coritto laments the faithlessness of those she thought her friends, but is consoled by Metro, who repeats her question. Coritto now reveals that the craftsman was Cerdon, and describes him and his works:

(20–21). Coritto laments the faithlessness of those she thought her friends, but is consoled by Metro, who repeats her question. Coritto now reveals that the craftsman was Cerdon, and describes him and his works:

and she was prevented from this last only by the presence of a neighbour's slave. Metro now asks how Coritto got to know Cerdon, and on hearing that it was through Artemeis, she declares her intention of going to see her, to learn more of Cerdon, and departs (95–98). The poem ends with Coritto giving orders for the door to be closed and the hens counted.

and she was prevented from this last only by the presence of a neighbour's slave. Metro now asks how Coritto got to know Cerdon, and on hearing that it was through Artemeis, she declares her intention of going to see her, to learn more of Cerdon, and departs (95–98). The poem ends with Coritto giving orders for the door to be closed and the hens counted.