Introduction

Meaning in life refers to a broad field of experiences, needs, motivations, cognitions and emotions that constitute the meaningfulness (or lack thereof) of people’s daily lives (Reker and Wong, Reference Reker, Wong, Birren and Bengtson1988; Steger, Reference Steger, Snyder and Lopez2002; Hicks and King, Reference Hicks and King2009; Wong, Reference Wong and Wong2012; George and Park, Reference George and Park2016; Hupkens et al., Reference Hupkens, Machielse, Goumans and Derkx2018). Meaning in life has been the subject of philosophical reflection over the centuries. In psychology, the theme of meaning in life only came to the fore much later and is mainly based on the work of Viktor Frankl, Abraham Maslov and Irvin Yalom, who understand meaning in life as a fundamental human (psychological) need and a central aspect of human development. Within positive psychology meaning in life is an important theme too, e.g. in Carol Ryff’s psychological wellbeing model and Aaron Antonovsky’s theory of salutogenesis (Antonovsky, Reference Antonovsky1987; Ryff, Reference Ryff1989). Meaning in life is related to a positive attitude towards life, a sense of communion with others, engagement in meaningful activities, a sense of inner strength and harmony, and a better point of departure for coping with stressful life events, existential dilemmas and adversities (Zika and Chamberlain, Reference Zika and Chamberlain1992; Park and Folkman, Reference Park and Folkman1997; Baumeister and Vohs, Reference Baumeister, Vohs, Snyder and Lopez2002; Janoff-Bulman and Yopyk, Reference Janoff-Bulman, Yopyk, Greenberg, Koole and Pyszczynski2004; Krause, Reference Krause2007; Park, Reference Park2010). Research indicates that living a meaningful life is accompanied by better physical and mental health, wellbeing and quality of life (Zika and Chamberlain, Reference Zika and Chamberlain1992; King et al., Reference King, Hicks, Krull and Del Gaiso2006; Low and Molzahn, Reference Low and Molzahn2007; Krok, Reference Krok2014; Czekierda et al., Reference Czekierda, Banik, Park and Luszczynska2017; Söderbacka et al., Reference Söderbacka, Nyström and Fagerström2017; Volkert et al., Reference Volkert, Härter, Dehoust, Ausín, Canuto, Ronch, Suling, Grassi, Munoz, Santos-Olmo, Sehner, Weber, Wegscheider, Wittchen, Schulz and Andres2019; Beach et al., Reference Beach, Brown and Cukrowicz2021; Li et al., Reference Li, Dou and Liang2021), and even greater average longevity (e.g. Pitkala et al., Reference Pitkala, Laakkonen, Strandberg and Tilvis2004; Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Barnes, Buchman and Bennett2009, Reference Boyle, Buchman, Barnes and Bennett2010; Krause, Reference Krause2009). In later life, meaning even seems to gain importance (Pachana and Baumeister, Reference Pachana and Baumeister2021). This is manifested, for instance, in the increasing need for life review, the need for adjustment to different roles (e.g. after retirement, upon becoming care-dependent or following a change in place of dwelling), or issues and confrontation with death and finitude, which tend to increase with age (Wong, Reference Wong1989; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Metcalf and Schow2000; Takkinen and Ruoppila, Reference Takkinen and Ruoppila2001; Reker and Woo, Reference Reker and Woo2011; Krause and Hayward, Reference Krause and Hayward2012; Cozzolino and Blackie, Reference Cozzolino, Blackie, Hicks and Routledge2013; Lan et al., Reference Lan, Xiao and Chen2017; Manning, Reference Manning, Bengston and Silverstein2019; Aydin et al., Reference Aydın, Işık and Kahraman2020).

People can derive meaning from various sources, such as love, work, leisure time, religion, spirituality, nature, health, self-realisation, personal growth and relationships with others (see e.g. Debats, Reference Debats1999; Bar-Tur et al., Reference Bar-Tur, Savaya and Prager2001; Stillman et al., Reference Stillman, Baumeister, Lambert, Crescioni, DeWall and Fincham2009; Krok, Reference Krok2014, Reference Krok2015; Hupkens et al., Reference Hupkens, Machielse, Goumans and Derkx2018). Although the importance of these sources varies with age and culture, many studies show that social relationships are the most important source of meaning in life for older persons, regardless of the culture in which they live (see e.g. Bar-Tur et al., Reference Bar-Tur, Savaya and Prager2001; Hedberg et al., Reference Hedberg, Gustafson and Brulin2010; Grouden and Jose, Reference Grouden and Jose2014; Jonsén et al., Reference Jonsén, Norberg and Lundman2015). This is especially true for positively experienced relationships with family, partners and friends (Ebersole and DePaola, Reference Ebersole and DePaola1987; King et al., Reference King, Hicks, Krull and Del Gaiso2006; Fegg et al., Reference Fegg, Kramer, Bausewein and Borasio2007; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Stillman, Baumeister, Fincham, Hicks and Graham2010; Steger, Reference Steger, Diener and Oishi2018; Duppen et al., Reference Duppen, Van der Elst, Dury, Lambotte and De Donder2019; Man-Ging et al., Reference Man-Ging, Öven Uslucan, Frick, Büssing and Fegg2019; Krause and Rainville, Reference Krause and Rainville2020; Golovchanova et al., Reference Golovchanova, Owiredua, Boersma, Andershed and Hellfeldt2021). Furthermore, meaningful social contact can help older people realise their potential for generativity, ego-integrity and gerotranscendence (Erikson, Reference Erikson1997; Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005; Villar et al., Reference Villar, Serrat and Pratt2023). Apart from personal relations, participation in meaningful activities is also an important source of meaning in later life. Both social events and achievement events in daily life can contribute to fulfilling a variety of meaning needs, such as purpose, control or self-worth, and help to connect one’s life to a larger context of social and cultural practices, many of which rely intensely on shared routines and habits (Penick and Fallshore, Reference Penick and Fallshore2005; Machell et al., Reference Machell, Kashdan, Short and Nezlek2015; Heintzelman and King, Reference Heintzelman and King2019). Finally, religion and spirituality are important providers of meaning in life for many older adults. Religion provides a connection with a transcendent reality and serves as a global meaning framework providing a sense of belongingness, coherence, a set of values and moral directions, that guide people in finding answers to pressing existential and moral questions, for instance, about one’s nearing end. Religion and (many forms of) spirituality are beneficial for addressing these existential questions satisfactorily (Park, Reference Park2010; Silberman, Reference Silberman2005; Krause and Hayward, Reference Krause and Hayward2012; Steger, Reference Steger and Wong2012; Krok, Reference Krok2014, Reference Krok2015).

While positive social relationships are crucial for the presence of meaning for older persons, Western countries are confronted with growing numbers of older adults who have reduced personal networks and are socially isolated. Empirical studies indicate that about 10 per cent of the adult population in Europe suffers from social isolation (Fokkema et al., Reference Fokkema, De Jong Gierveld and Dykstra2012; Cornwell et al., Reference Cornwell, Schumm, Laumann, Kim and Kim2014; d’Hombres et al., Reference d’Hombres, Barjaková and Schnepf2021). These socially isolated older adults have little or no actual social contacts and interactions with family members, friends or the wider community (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2009; Cloutier-Fisher et al., Reference Cloutier-Fisher, Kobayashi and Smith2011; Dury, Reference Dury2014; Zavaleta et al., Reference Zavaleta, Samual and Mills2014). In recent years, many studies have been carried out on the relationship between social isolation and health, wellbeing and quality of life (e.g. Holt-Lunstad et al., Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris and Stephenson2015; Valtorta et al., Reference Valtorta, Kanaan, Gilbody and Hanratty2016; Baarck and Kovacic, Reference Baarck and Kovacic2022), but hardly anything is known about the relationship between social isolation and meaning in life. This study focuses on this gap. Since meaning in life for older adults presumes social connectedness with significant others or with the broader community, this study aims to explore whether and how older adults who live in social isolation experience meaning in life. Such knowledge can contribute to helping this target group and ensure that interventions are aligned with them.

Meaning in life

Although the importance of meaning is widely recognised, and a large number of studies on meaning are available, meaning in life is conceptualised in several ways, using varying definitions that emphasise different aspects (Brandstätter et al., Reference Brandstätter, Baumann, Borasio and Fegg2012; George and Park, Reference George and Park2016; Hupkens et al., Reference Hupkens, Machielse, Goumans and Derkx2018). Based on a thorough review of empirical findings, the American social psychologist Roy Baumeister concluded that four needs shape the human experience of meaning, which can be understood as ingredients or criteria for a meaningful life. The four needs that give direction to the human endeavour to find meaning are the need for purpose, values, efficacy and self-worth (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister1991). Having a purpose gives direction to one’s life and connects present events with future events. The purpose may be aimed at a desired situation or inner fulfilment, such as love or happiness. Values are the basis for action and justify one’s way of life. These values ensure that a person has done the right thing and that regrets, fears, guilt and other forms of moral distress are limited. Efficacy refers to the need to have influence and a grip on situations and circumstances in life: when people have control, they can achieve their goals based on the values they hold dear. Finally, a basis for self-worth is needed so that people can see themselves as valuable. People derive self-esteem from individual goals they achieve or through participation in a social group that they perceive as valuable.

After studying a variety of social psychological and philosophical sources, the Dutch philosopher Peter Derkx added three more needs: coherence, excitement and connectedness. Coherence refers to the need for a coherent understanding of the reality in which one lives, e.g. by creating a coherent life narrative for oneself, which safeguards a stable sense of identity and continuity (McAdams, Reference McAdams1997; Nygren et al., Reference Nygren, Aléx, Jonsén, Gustafson, Norberg and Lundman2005; Heintzelman et al., Reference Heintzelman, Trent and King2013; George and Park, Reference George and Park2016; Martela and Steger, Reference Martela and Steger2016). The need for excitement describes the importance of elements in life that breach the dullness, monotony and boredom of routines, e.g. an aesthetic experience of wonder or awe when one is immersed in nature or art (Frankl, [1946] Reference Frankl2006; Melton and Schulenberg, Reference Melton and Schulenberg2007; Morgan and Farsides, Reference Morgan and Farsides2009). The need for connectedness is understood as being connected to other people, and feeling closeness or communion with others or to something other than oneself, with an impersonal Other, with God, with nature or with a positively valued transcendent reality (Derkx et al., Reference Derkx, Bos, Laceulle and Machielse2019).

Derkx proposes a model that encompasses Baumeister’s four needs for meaning (purpose, values, efficacy and self-worth, and the added needs of coherence, excitement and connectedness). This model provides a helpful framework for analysing what causes people to experience their life as meaningful or not. It also provides concrete distinctions for enabling care-givers to recognise elements of meaning (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister1991; Derkx et al., Reference Derkx, Bos, Laceulle and Machielse2019). Therefore, in this study, I choose to focus on this needs-based model of meaning in life.

Materials and methods

This study is part of a more-extensive qualitative study being conducted in Rotterdam, the second-largest city in the Netherlands. In that study, a large group of socially isolated community-dwelling older adults is followed over time to identify changes in their daily life situations and their need for help and support (Machielse, Reference Machielse2015; Machielse and Duyndam, Reference Machielse and Duyndam2020, Reference Machielse and Duyndam2021). The longitudinal study aims to gain insights that will contribute to the quality of the assistance provided to this target group (Machielse and Hortulanus, Reference Machielse, Hortulanus, Baars, Phillipson, Dohmen and Grenier2013). In this study, a qualitative research methodology with a strong exploratory character is followed, to provide insight into the subjective experiences of the socially isolated older adults themselves. They are seen as ‘experts’ who have indispensable knowledge about their situations, which is necessary to offer adequate help (Sackett et al., Reference Sackett, Straus, Richardson, Rosenberg and Haynes2000; McNeece and Thyer, Reference McNeece and Thyer2004).

Participants

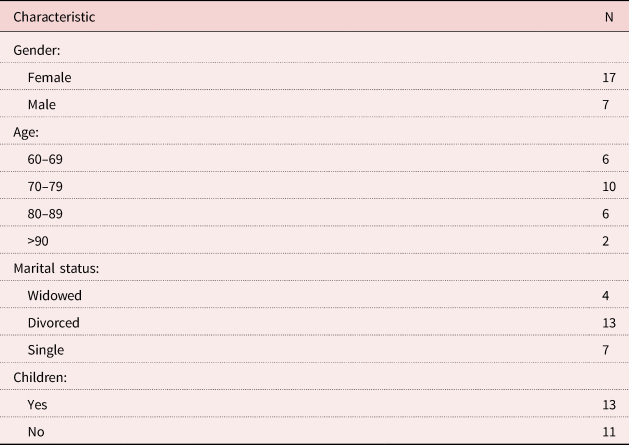

The criterion-based sampling of participants for this sub-study took place in close consultation with social workers of a mentoring project in which trained volunteers are coupled with socially isolated older adults. During the intake interview with newly registered participants, the social workers assessed which older people they wanted to invite to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were age 60 or older, absence of social contacts with family members, friends or acquaintances, and no participation in social activities. Exclusion criteria were severe mental problems or addiction for which they received psychiatric help or addiction help. The consequence of this selection procedure was that only interviews were held with socially isolated older adults who were known to the social service agencies. The social workers acted as gatekeepers and made their considerations. Whether or not the older adults wanted to participate depended (in part) on their relationship with the social workers. The interviews with them took place at the time the assisting social worker had gained sufficient trust from the client to introduce a researcher. Some of the participants invited indicated that they did not want to co-operate with the study because they found it too burdensome, or had no desire to participate in the study. The sample (see Table 1) consisted of 24 participants (seven men and 17 women), ranging in age from 62 to 94, all living alone (13 divorced, four widowed and seven who had never married and had lived alone their entire adult life). Thirteen participants did have adult children but were estranged from them. The two children of one participant had died.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants

Note: N = 24.

Data collection

Data were collected via in-depth, semi-structured interviews with the selected participants, conducted in 2018 and 2019. The interviewer followed the flow of the conversation while preserving the orientation on the subject, aided by a list of topics. The main themes in the topic list were: the participants’ living situations and daily life, the background of their social isolation, and meaning in life. Much attention was paid to an open, attentive attitude/approach towards the participants and their experiences (Thomas and Pollio, Reference Thomas and Pollio2002; Smith and Eatough, Reference Smith, Eatough, Lyons and Coyle2016). The interviews were held at the participants’ homes and lasted between 1.5 and 3 hours. All participants were willing to talk very extensively about their situations and experiences. Twenty-two participants were interviewed twice, at 4–6-month intervals. Two participants were not interviewed a second time: one woman (age 69) had died (due to suicide) and one man had moved to a nursing home. The researcher made arrangements for the follow-up interviews without the intervention of the social workers, although the latter were notified (after the agreement of the participant concerned). The follow-up interviews aimed to arrive at a deeper understanding of the research topic by clarifying issues that emerged in the prior interviews and discussing the researcher’s interpretations (member checking). All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim, with the participants’ permission.

Data analysis

The analysis was an iterative process that alternated data collection and analysis using a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive thematic analyses (see Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, Reference Fereday and Muir-Cochrane2006).

The inductive analysis was conducted on two levels: an individual and an overarching level. First, at the individual level, the interviews of each participant were analysed to understand the participants’ unique experiences in context. This analysis involved open coding to identify the themes that emerged from the conversations (cf. Wong and Watt, Reference Wong and Watt1991). Second, a thematic analysis was conducted to discover overarching themes and patterns across different cases. The thematic analysis was less focused on data-driven descriptions and more on discovering patterns of meaning in the entire dataset (Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Lewis, Nicholls and Ormston2013). The analysis on the two levels was a fluid one, as the researcher repeatedly moved in and out, from the parts (individuals) to the whole (all respondents) and back again (Dahlberg et al., Reference Dahlberg, Dahlberg and Nystrom2008). Still, in both phases, codes were initially grounded in the data (inductive coding).

Next, an additional, deductive analysis was conducted. For this, I used the conceptual model of meaning in life, based on Baumeister’s four needs of meaning – purpose, values, efficacy and self-worth – and Derkx’s added needs for coherence, excitement and connectedness. All coded fragments were assigned to one or more of the seven meaning needs of this theoretical model. Aspects from the transcripts that did not relate to aspects of meaning were excluded from the results. The model helped to bring some order to the wide variety of the open codes while attending to how the ‘lived experience’ of the participants can be understood (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz1990). This categorisation also forms the basis for the results presented in this paper.

Research quality

Various strategies were used to establish the trustworthiness of the study’s findings. First, to achieve breadth and depth in the researched casuistry, information about most participants was collected at two different moments in time. The follow-up interviews with 22 older adults offered the possibility of member validation, confirming whether the interpreted findings from the first interviews were in line with the participants’ experiences (Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Lewis, Nicholls and Ormston2013). This improved the integrity of the research process and helped to expand and refine the analysis process. Second, dependability was established by recorded and verbatim-transcribed data, the use of analytical software (MAXQDA 2020) and an analytical framework (Creswell, Reference Creswell2013; Smith and Eatough, Reference Smith, Eatough, Lyons and Coyle2016). Third, reflexivity was fostered through a research diary and through dialogues with the social workers (peer examination) to develop understanding further (Dahlberg et al., Reference Dahlberg, Dahlberg and Nystrom2008).

Results

This section describes the experiences of the participants, structured by the seven needs of meaning, identified by Baumeister – purpose, values, efficacy and self-worth − and Derkx – coherence, excitement and connectedness. The participants have a code: number (P), female/male (f/m) and age.

Purpose

The first dimension of meaning in life is purpose, having a goal one wants to achieve. All participants in this study indicate having no goals for the future and having few expectations at this point. One woman says she has nothing left to live for: ‘My future, I don’t see anything in it. Because what could I possibly have to look forward to? I’m alone all the time’ (P1, f71). A man who after losing his wife became isolated has made arrangements for voluntary end-of-life:

I have very specific plans to put an end to my life because this is no life, I don’t want this life anymore. I’ve read a lot about it, and spoken to the doctor a lot, and everything is ready. (P10, m88)

Others prefer not to think about the future:

I don’t look forward to the future. What could I expect from the future? Every morning when I wake up, I think: “Well, I’m still here.” But I don’t dare peek into the future. No, I really don’t. (P11, f74)

An important point that emerges in the interviews is the health of the participants. They all hope to remain healthy and not need care from others. One woman asks herself what it will be like when she becomes less mobile: ‘If I cannot get around anymore, then I don’t know, I don’t think about it. I’ll figure it out when it happens’ (P19, f76). One man knows that he absolutely wants to stay living in his own home:

I don’t want to go to a nursing home. The change, a new environment, I don’t think I can handle those changes anymore. I would rather just kick the bucket. (P20, m74)

Values

Values are a kind of standard to evaluate if one’s life has been worthwhile and if one has done the right things. Most participants in this study consider love as the most important value in life, yet state that they did not experience enough of it. Only one man says that he had known a lot of love in his life, first from his parents and later from his wife:

I was an only child and had very loving parents. Because of this, I had a very happy youth. And I was very happy in my marriage. (P10, m88)

Since his wife died 10 years ago, happiness has disappeared from his life: ‘I never thought anyone could be so unhappy as I’ve been for the last few years’ (P10, m88). He is the man who wants to voluntarily end his life because he can no longer stand it.

Most seniors in the study have experienced little love in their lives. They have gone through failed relationships, often multiple times:

I had hoped to find a man I could live with forever. Together to the end and happy with each other. But I never met the right guy. Every time it went wrong again. (P21, f80)

For participants with children, divorce often entailed estrangement from their children:

I married a man, I was in love, I was crazy about that guy, but he was no good, and so I left him. But because of that I no longer see my children, it’s been 34 years already. (P16, f77)

Some participants never had a partner, often to their great sadness. One woman says:

I have never been married, unfortunately. I really wanted to, but it never happened. I never met the right person. I’m sorry about that. (P13, f64)

A woman who never had a relationship or children believes this to be the reason her life failed: ‘I love children! I really should have been a mother’ (P6, f78).

Another important value in the life of the participants is perseverance. Many of them reveal their life was always full of problems and that it is important to be strong and keep going. As one man says: ‘I’ve gone through a lot, both good and bad things. But I’m a fighter and I do not give up’ (P9, m62). One woman was brought up to deal with adversity:

Just keep breathing and face your challenges. That’s what my mother always said: ‘Face your challenges.’ I cannot live without that understanding. I need it in my life. If I didn’t have that understanding, I’d be nowhere. You must attach that attitude to yourself permanently. (P14, f94)

Efficacy

To experience life as meaningful it is important to influence situations and circumstances in one’s life. Most participants in the study feel that they never had a grip on their life or on the circumstances in which they landed:

The situation I ended up in, I can do little about it. This is just my life, that’s my life trajectory, it’s how my life went. (P11, f74)

Some participants blame themselves for having been too passive and letting things happen. One man explains how he always shied away from problems as much as possible throughout his life:

When living in society became too much for me, too terrible or too intolerable, I always withdrew into my little world. That gave me the possibility, the courage, to go on.

He never took steps to give a sense of direction to his life:

I never took a serious decision in my life. Maybe to stay alone, but that wasn’t a decision. If you don’t do anything, nothing happens. And you stay alone. (P2, m83)

Although most participants are not satisfied with their lives, they have no desire to change their lives. They like doing things their way and are used to solving their problems on their own: ‘It’s very difficult to change things. I always had to figure things out by myself, so I’m used to it’ (P18, m72). They want to be the ones in control of their lives and are very reluctant to be interfered with by others. One man states: ‘That might be a weird trait of mine, but I don’t want someone else to run my life’ (P22, m63). Most participants reject the involvement of care providers and want to determine how they lead their life:

My doctor is always saying: you have to do this and you have to do that. And her intention is, of course, good … but I prefer not to. I know exactly how I want things to be. (P1, f71)

Self-worth

Self-worth can be based on a positive evaluation of personal achievements. Solving problems without help from others contributes significantly to the self-esteem of participants. Many older adults in the study indicate being proud of themselves because they could face difficult situations in their lives. According to one woman:

It isn’t always easy, but I am a fighter and am proud of it. That is how I live. Keep trying, don’t give up. (P8, f67)

The fact that they have been doing this all their lives gives them confidence that they will succeed in the future as well:

I always found the strength to carry on. Life never knocked me out. And I will always find the strength to push through. (P17, f73)

Although it is not always easy, they will not easily show it, as this woman tells it: ‘Yes, I could also cry about it, and sometimes I do. But I do it when there’s no one around’ (P4, f78).

A single participant derives self-esteem (dignity) from past activities. One woman specifies that she has meant a lot to others in their life, through her work in a nursing home:

I buttered the residents’ bread, served them coffee, took them to the hairdresser, talked to them, and that was really nice. When I arrived in the morning they would say ‘I’m so glad you came’. I was always hearing things like that. (P3, f66)

One woman tells how important it is to her to dress well and look groomed. That was important in her former job, but now she just keeps doing it:

Because of my profession, of course, I always tried to look very put together. I still do that, every day. Because otherwise you might as well close your eyes and never open them again. (P5, f91)

For her, attention to her appearance is an expression of who she is and contributes to her self-respect. Appreciation from others is also a source of self-worth. One participant gets a lot of appreciation in his new neighbourhood, and he is proud of that:

All the neighbours are glad that I came to live here. Yes, because they know exactly what I’m about. Because I’m a decent person and I’m there for others! (P9, m62)

Some participants are very negative about themselves. They do not find themselves worth it or feel they have failed in life. In the words of one participant:

I’m an angry man, frustrated by a lack of success. Because I did not succeed, got sidetracked, I’m a bit of a misfit. (P2, m83)

One woman indicates that her life has had little meaning. She always lived with her parents, and after they died, she was left all alone:

Sometimes I think: who’s going to miss me? And that is a very negative thought, I do know that. But it goes around in my head. Yes, it’s how I feel. You feel useless. And that is a negative self-image, I know that. But I can’t shake it. (P13, f64)

Coherence

People experience their life as meaningful if they can look back on it with satisfaction, if they feel that their choices and the paths they have taken have a certain coherence (McAdams, Reference McAdams1997; Lövheim et al., Reference Lövheim, Graneheim, Jonsén, Strandberg and Lundman2013). The older adults in the study think a lot about their lives, the choices they made and the things they went through. Most look back on their life with little pleasure. For some seniors, it is mainly negative memories that resurface. One woman says:

You know, I think a lot about it. I think back to what happened in my life. Because I’m getting older, it’s normal for me to look back on my life. What I think of is mainly the bad things, they keep popping up in my mind. I cannot say that I had a happy youth. Or that I had a happy marriage. (P11, f74)

Some people wonder whether their life has been worthwhile: ‘Actually, I often think, what has my life actually been worth? When I look back’ (P21, f80).

Many participants tell about the choices they made in their lives. A woman who broke off contact with her only daughter 15 years ago explains why she did it:

I fought to make things right, but at a certain point, you have to choose for yourself. Because you cannot keep it up forever, it doesn’t work. At some point, you’re just going to lie six feet under. Of course, I was completely crushed because of it. But fortunately, I’ve always had the strength to get through it. And if I had contact with her again, I would fall back within a few months. So I made the right decision. Because you have to think of your health. (P17, f73)

Some participants think they made wrong choices, which took their lives in a direction they later regretted:

I feel so dumb about some things, now that I look back … I should have never gotten married. As a child I wanted to be a teacher, do something with children, that would have been the best thing for me. (P7, f82)

Another man deeply regrets things he did to others in the past. He cannot shake the feeling, even now that he is older. He tries to find a way to deal with it:

I’ve also done bad things. I went to a psychiatrist and said: ‘It haunts me.’ The psychiatrist said: ‘You must learn to live with it. You really must learn to live with it.’ And I say: ‘But I still have that gnawing feeling, with regret, remorse, remorse, remorse.’ I’m just so sorry I did things that way, whereas I didn’t have to at all. (P9, m62)

This man has a strong need to talk with others so that he can come to terms with it. Most participants who feel they did not choose the right path in their lives realise that they cannot change that. One participant tells:

I know that I screwed up. I always took the wrong turn in life. But what can one do about it at this point? (P2, m83)

Excitement

Most participants can appreciate small things in everyday life. One woman expresses that the fact that she is able to do that keeps her going:

That is just a gift I have, you know, enjoying the little things, even though my situation is very difficult. For example, I bought a little plant for myself and am very happy with it. (P15, f86)

Another woman enthusiastically tells about her favourite football club. She never goes to matches but follows the club from a distance:

I am a member of the Feyenoord Supporters Club. That’s why I get all this information at home, so you’ll be kept up to date, that’s very fun. (P17, f73)

Other participants struggle through the days and derive no pleasure from anything. One man says:

I live from day to day and make the best of it. Try to smoothen it out. That’s what I have learned in those years. To die quietly in the night, sometimes seems a good idea. (P2, m83)

Connectedness

All participants have been living in isolation for many years already and most of them have resigned themselves to the situation. For some of them, being alone becomes less demanding, as their need for contact decreases:

When you get older, you become different, more on your own. Much more. Then you have fewer needs. You don’t need so much anymore. (P19, f76)

For other participants, the need is increasing:

I have never let anyone into my life that deeply, but now at 80 years of age I do miss it. That is because you start to feel and see the relativity much more now. That develops very strongly. (P23, m80)

Being alone keeps getting harder and harder. One woman says: ‘I don’t want to become 100. To be alone for another 20 years, I don’t think I can take it’ (P4, f78).

None of the participants participates in social activities, yet they find it very important to know what is happening in the world. They watch a lot of television or listen to the radio. One woman says:

I keep up with all the news, I am aware of everything. I switch to different stations because I don’t want to be behind. I know everything. I want to be up to date with everything. (P6, f78)

For another participant, the radio is ‘his eye on the world’ (P2, m83).

For several participants, religion is an important source of connectedness. One woman puts it as follows:

I am never alone because I feel that my heavenly Father cares for me. That’s very important for me. I could not do without him. I never go to sleep until I have made some contact. (P16, f73)

Most seniors who no longer have contact with their children think a lot about them. It still makes them sad, and they try to come to grips with it. One woman tries to think mainly of the good moments:

You never get used to the children not visiting. But my memories keep me going because in the past I have also had nice times with the children. I often look back on that. (P12, f78)

The woman who had not had contact with her children for 34 years always thinks about what happened back then: ‘I keep thinking about it, and there is no one to help me with this mental stuff’ (P16, f77).

All persons in this study have situational connections with a social worker. This contact is very important for all of them. They trust the professionals and know that they can always turn to them: ‘If I have a hard time, I call her, and she will come and talk to me’ (P24, f67). They like the professional to keep track of things:

She stops by every three weeks. We make an appointment, and she comes to see how things are going. That’s important because I have someone to talk to. I did not use to have that, and it worried me. It’s good to be able to talk to someone now. (P23, m77)

This monitoring gives older adults a sense of security and peace of mind for the future. For some participants, the social worker is emotionally indispensable, as this woman points out:

She is everything to me, I have even come to love her. And that’s not allowed, of course, so I can’t tell her that. (P24, f67)

Discussion

Previous research indicates that social connectedness with significant others or with the broader community is the most important source of meaning in life for older persons (see e.g. Stillman et al., Reference Stillman, Baumeister, Lambert, Crescioni, DeWall and Fincham2009; Hedberg et al., Reference Hedberg, Gustafson and Brulin2010; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Stillman, Baumeister, Fincham, Hicks and Graham2010; Grouden and Jose, Reference Grouden and Jose2014; Krause and Rainville, Reference Krause and Rainville2020). Since socially isolated older adults lack this important source of meaning in life, this paper aimed to explore whether they do experience meaning in life and, if so, how they fulfil their meaning-making needs. Because meaning in life is an abstract concept with many different aspects, I chose to investigate the experience of meaning in life through a theoretical model, based on the work of Baumeister and Derkx, in which seven different needs for meaning are distinguished: purpose, values, efficacy/control, self-worth, coherence, excitement and connectedness (Baumeister and Vohs, Reference Baumeister, Vohs, Snyder and Lopez2002; Derkx et al., Reference Derkx, Bos, Laceulle and Machielse2019).

Regarding the need for purpose, it became clear that the older adults in this study have hardly any goals that they want to achieve. They have nothing to look forward to and live by the day. Instead of having high expectations of life, they want to preserve how they live now and hope to remain healthy and mobile. Most participants mentioned love and happiness as essential values, although they did not maintain happy relationships with partners or children. Only a few experienced a lot of love in their lives. Another important value for them is that they have managed in life, despite all the problems they faced. The ability to adapt and the perseverance that was needed to survive gave them a sense of control. They are proud that they manage, and this pride contributes significantly to their sense of self-worth and self-respect. Yet many participants think very negatively of themselves. They consider themselves useless and believe that they will not be missed by anyone when they are gone. Now they are older, they look back on their lives and have a strong need to create a coherent life story. Reflecting on the past brings back memories of pleasant events and things that have been painful or problematic. Those who regret the choices they made in the past try to come to terms with that. Most participants experience excitement in everyday things that break through their daily routines, such as a television programme or a plant in the house. For others, disappointment, frustration and a feeling of emptiness dominate their lives. They struggle to get through the days. All participants have been living in social isolation for a long time. Most of them have become accustomed to being alone and have no need to interact with others. They are afraid that connection with others conflicts with other needs, such as control. Some participants have found alternative ways to fulfil their need for connectedness, e.g. by following the news, or through religious or spiritual activities. For some participants, being alone is getting harder and harder. Especially the broken contact with children continues to cause much grief.

Daily versus existential meaning in life

Meaning-making in later life is conceived as a dialogical process grounded in social relationships with mutual trust, recognition and emotional closeness. This study shows that older adults without such relationships may find anchors for meaning in life and experience daily moments of meaning in modest and seemingly trivial ways. In the literature, this is often referred to as situational meaning in life, meaning of the moment or daily meaning (Park and Folkman, Reference Park and Folkman1997; Reker and Wong, Reference Reker, Wong and Wong2012; Edmondson, Reference Edmondson2015). In addition, the literature speaks of a more existential form of meaning-making, referring to meaning as a response to situations of crisis or existential trauma in which one’s most fundamental values and choices are challenged (Steger, Reference Steger, Slade, Oades and Jarden2018; Hicks and King, Reference Hicks and King2009; Park, Reference Park2010). In those situations, the motivation to search for meaning can be interpreted as a striving to restore coherence with one’s global meaning framework so that other meaning needs can be experienced again (Park, Reference Park2017). This form of meaning seems important for the socially isolated older adults in this study. Since the basic human need for connectedness and belongingness is not met, most participants try to adapt their behaviour or interpret their lives differently to avoid the threat of meaninglessness.

The concept of existential meaning is also related to the view that distinguishes empathically between a meaningful life and a happy life (e.g. Diener et al., Reference Diener, Lucas and Oishi2018; Ryff, Reference Ryff and Wong2012). Where happiness means that one’s needs and desires are satisfied, including being mostly free from unpleasant events (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2008; Keyes and Annas, Reference Keyes and Annas2009), meaning in life is usually understood as a more complex concept (eudaimonia), as it requires interpretative construction of circumstances across time according to abstract values and other culturally mediated ideas (Baumeister et al., Reference Baumeister, Vohs, Aaker and Garbinsky2013). A happy life is primarily about a positive experience in the here and now, where the experience of meaning in life implies the integration of past, present and future, or a sense of coherence and stability (Morgan and Farsides, Reference Morgan and Farsides2009; Baumeister et al., Reference Baumeister, Vohs, Aaker and Garbinsky2013). The socially isolated older adults in this study look back on their lives, searching for some coherence that can explain why certain things happened to them. The resources and personal strengths carried over from previous life experiences help them deal with their current situation and affect their expectations for the future.

Live narratives

In the literature is scant agreement on which theory of a meaningful life is the best starting point for further research, and many authors criticise simplified approaches that neglect the complexity and conceptual range of meaning in life as a construct (e.g. Martela and Steger, Reference Martela and Steger2016). Even though meaning in life is a very abstract and complex concept and definitions are arbitrary or ambiguous, the needs-based model that I used in this study enabled fertile reflection on meaning in the lives of socially isolated older adults. The seven elements of meaning were very helpful in the conversations with older adults and could be used to analyse elements of meaning (or the lack thereof) in their lives.

The analysis also made clear that the theoretically distinct components of meaning are intertwined strongly in the participants’ narratives (cf. Derkx et al., Reference Derkx, Bos, Laceulle and Machielse2019). This allows different sources of meaning to compensate for each other (cf. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Sang, Chan and Schlegel2019). In the literature on meaning in life, connectedness (especially connectedness with other persons) is often presented as the most fundamental and constitutive component of meaning, and social isolation is conceived as a serious threat that reduces the sense of meaning in life (Stillman et al., Reference Stillman, Baumeister, Lambert, Crescioni, DeWall and Fincham2009). In this study, I saw the high importance that all participants placed on control over their situation which could be seen as compensating for their lack of a sense of social connectedness of belonging. Their desire to retain control and not become dependent on others is in line with previous research into people who find themselves in difficult situations (Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2002).

Implications for social work practice

The findings of this study make demands on the professionals who provide support to socially isolated older adults. Due to their strong need to maintain control over their lives, they are wary of interference from others that may disturb the peace they have so painstakingly earned in their lives. Previous research revealed that people who live in social isolation for a long time develop strategies and routines that offer them security and peace of mind (Machielse and Duyndam, Reference Machielse and Duyndam2020). To avoid compromising this, they are not open to support or interventions that could bring about a change in their situation. They perceive their isolation as irreversible and like to keep the situation as it is. Help from others, after all, often means that they must break through coping strategies and abandon their trusted routines. This passive attitude is often found among older adults who have been through a lot in their lives (see e.g. Dittmann-Kohli, Reference Dittmann-Kohli1990; Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2002). Still, socially isolated older adults may need some support to persevere and deal with further problems, e.g. health problems, or more existential problems related to their isolation. Since social workers are the main contact for these older people, being ready to react to complex existential themes is an essential part of their help. They need the expertise to empathise with their clients and recognise their emotions of sadness, desperation and disappointment (Van Dijke et al., Reference Van Dijke, van Nistelrooij, Bos and Duyndam2020).

Another important focal point for professionals is that meaning in life for socially isolated older adults is not a momentary problem, but a theme that requires taking a lifecourse perspective, that connects their past, present and anticipated future (Thompson, Reference Thompson1992). Creating a coherent life narrative presupposes the sharing of life memories with others and this sharing becomes more important in later life when time horizons are constrained and death draws near (Carstensen et al., Reference Carstensen, Fung and Charles2003; Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005; Cozzolino and Blackie, Reference Cozzolino, Blackie, Hicks and Routledge2013; Johnson, Reference Johnson, Johnson and Walker2016). Sharing their experiences and life stories with a professional helps them conceive of events and choices in the past as understandable and meaningful. This lifecourse perspective should also include the temporal dimensions of specific meaning components, which seem of special relevance as people age and their self-reliance declines. These are important findings for social work practices since interventions for socially isolated older adults are often social facilitation interventions aimed at combating loneliness (Gardiner et al., Reference Gardiner, Geldenhuys and Gott2018; Beckers et al., Reference Beckers, Buecker, Casabianca and Nurminen2022).

Limitations of the study

Some limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the contribution of the social workers who acted as gatekeepers and determined which clients they invited to participate in the research. It is not always clear how the social workers judged whether or not a specific client would be eligible to participate in the study. Second, all participants in this study had contact with a social worker and were prepared to converse with the researcher. Therefore, it is improbable that the participants in this study represent the entire target group of older adults who live in social isolation. Third, all participants are living independently, but there is a large variation in age (from 62 to 94). Also, the gender distribution is not equal because the social workers involved have more women than men in their caseload. It is possible that within the group of participants in this study there are still patterns to be discovered that are related to their gender or age. Fourth, the findings cannot be generalised to all socially isolated older adults. The practical value of this study is to be determined by social workers, who from their professional background can determine whether there are sufficient relevant similarities to make it plausible for the findings to apply to non-researched situations too. Follow-up studies should explore the experiences of older adults in different age categories, and older adults who are marginalised even further and who are not being reached through any interventions or supportive services in the community.

Conclusion

This study explores the experiences of meaning in the lives of older people who have been in social isolation for a long time, using a needs-based model that distinguishes seven aspects of meaning. The model turned out to be a helpful framework for analysing what causes people to experience their life as meaningful or not. The seven dimensions of meaning provide concrete distinctions for enabling care-givers to recognise elements of meaning. The model allows the seven aspects of meaning to overlap and relate to each other in people’s narratives. It also makes clear there may be a certain tension between the dimensions. For example, the strong need for control of the socially older adults leads to the rejection of help and interference, while they have a strong need to talk about their lives and their situation. These findings are relevant because evaluation studies show that interventions for socially isolated older adults produce hardly positive results (Dickens et al., Reference Dickens, Richards, Greaves and Campbell2011; Machielse, Reference Machielse2015, Reference Machielse2022; Gardiner et al., Reference Gardiner, Geldenhuys and Gott2018; Machielse and Duyndam, Reference Machielse and Duyndam2021; Beckers et al., Reference Beckers, Buecker, Casabianca and Nurminen2022). Knowledge of meaning needs can help improve the quality of support for this target group.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the participants, social workers and social work agencies who collaborated on this project.

Financial support

This work was commissioned and funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Wellbeing and Sports (VWS); the Rotterdam municipality; and Movisie, the national knowledge institute in the social domain in the Netherlands.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical standards

In this study, standard procedures for the Netherlands, including the Dutch Code of Conduct for Applied Research for Higher Professional Education (Algra et al., Reference Algra, Bouter, Hol and Van Kreveld2018) were followed. An ethics committee assessed the research proposal following Dutch guidelines. The research was found not to be subject to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). All respondents expressly agreed to participate in the study and before the start of each interview confirmed their informed consent, which was audio-recorded digitally. Special attention was paid to anonymity in all notes and observation descriptions. In the article, codes are used for the participants.