Introduction

Today, the vast majority of industrialised countries are experiencing an accelerated ageing process, and Chile is no exception. The national population census of 2017 revealed that, for the first time in national history, the number of adults over 60 years of age had surpassed the population under 15 years (Censo, 2017). People aged 60 years and above now represent nearly 20 per cent of the total population of Chile, mainly due to decreased birth rates and increased life expectancy of an average of 79.5 years, which is the highest among all South American countries. It has also been forecasted that by 2050, nearly 33 per cent of the total Chilean population will belong to the age group of 60 years and above (Censo, 2017). This fast-paced population ageing has socio-cultural, economic and political implications.

The pension and social care systems are being greatly affected by population ageing. The savings accrued in the pension reserve funds are insufficient to cope with the high costs of living in Chile, due to unstable employment trajectories and low wages throughout the lifecycle, mainly among women. Furthermore, the legal retirement age in Chile is relatively low: 60 years for women and 65 years for men. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately one-third of older people in Chile were working beyond the legal retirement age (UC-Caja Los Andes, 2020).

Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has had an enormous impact on older individuals' economic activity. According to the Ageing Observatory (2020), between March and May 2020, the number of formally employed people in the age group of 60 years or above decreased by 25 per cent when compared to the same period in 2019, with over 380,000 older people becoming unemployed. This also suggests that a higher number of older individuals have been forced to undertake informal jobs, thereby being more exposed to the risks of the pandemic.

Given the current demographic and health challenges, which undoubtedly have a substantial effect on the national economy, the labour participation of older adults in Chile requires special attention. It is crucial to understand the factors that retain older adults in the labour market, by analysing the intrinsic motives of older individuals for extending their economic activity beyond the statutory pension age.

Since the social, political and economic implications of population ageing have become more widespread over the past decade in many developed and developing countries, there has been more research undertaken in the field of post-retirement work, which was previously shadowed by the early and on-time retirement research (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Phillipson2016). So far, a considerable number of studies in the field of extended careers have focused mainly on factors related to working conditions, including work flexibility, training and development, organisational support or financial incentives (Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Moore and Hodgkin2014; Radford et al., Reference Radford, Shacklock and Meissner2015; Thieme et al., Reference Thieme, Brusch and Büsch2015; de Wind et al., Reference de Wind, Scharn, Geuskens, van der Beek and Boot2018). The literature on implicit factors of a psycho-social nature that stimulate older adults to remain within the labour market, on the other hand, has been relatively scarce. However, several scholars have agreed that intrinsic motivation plays a crucial role in understanding extended career decisions (Catania and Randall, Reference Catania and Randall2013; Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Campbell, Kroeker-Hall, Burke, Cooper and Antoniou2015; Sewdas et al., Reference Sewdas, De Wind, Van Der Zwaan, Van Der Borg, Steenbeek, Van Der Beek and Boot2017) and there has been recent evidence showing that people's intrinsic work motivation does not necessarily decrease over time (Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Farrow and Blank2012; Akkermans et al., Reference Akkermans, de Lange, van der Heijden, Kooij, Jansen and Dikkers2016).

The majority of existing research on intrinsic work motivation is, however, quantitative and has mainly focused on European and other English-speaking developed countries (Van Den Berg, Reference Van Den Berg2011; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, de Lange, Jansen and Dikkers2013; Akkermans et al., Reference Akkermans, de Lange, van der Heijden, Kooij, Jansen and Dikkers2016). Thus, there has been a recent call for more studies using qualitative methods (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Phillipson2016) to include the perspective of the main actors – older workers – acknowledging their heterogeneity and internal motives.

The present study focuses on intrinsic motivation among older adults in the particular context of Chile for several reasons. As mentioned above, Chile has been experiencing a noticeably accelerated population ageing process and is likely to position itself among the oldest 30 countries of the world within the next 20 years (United Nations, 2019). Given the presence of the free market economy, the lack of government policy interventions and remarkably low pension replacement rates (Dintrans et al., Reference Dintrans, Browne and Madero-Cabib2020), a greater number of older Chilean adults decide to engage in post-retirement work. When it comes to the social policy landscape of post-retirement work in Chile, notwithstanding an increasing number of active older adults, there is an absence of public policies aimed at extending careers which could be found in other developed countries, including lifelong training opportunities or financial incentives to continue working after the legal retirement age. This suggests that post-retirement work decisions in Chile are rather driven by the lifecourse events than by national policy measures (Madero-Cabib and Biehl, Reference Madero-Cabib and Biehl2021). Interestingly, although financial need seems to be the primary reason why older people work longer in Chile, a national survey revealed that over 60 per cent of older people would like to continue working even if they did not have an economic need to do so (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Abusleme, Arenas, Berwart, Fernández, Kornfeld, Madero-Cabib, Quesney, Rojas, Rojas and Belloni2018). Moreover, recent research (Galkutė and Herrera, Reference Galkutė and Herrera2020) also reported a positive and significant association between intrinsic motivation and post-retirement work in Chile, indicating the need to deepen our knowledge of older adults' work experiences.

Hence, the present research aims to identify and explain the intrinsic work motivation of formally employed Chilean adults at retirement age. To do so, we use the Meaning of Work theoretical perspective (Harpaz, Reference Harpaz1998; Rosso et al., Reference Rosso, Dekas and Wrzesniewski2010), which emphasises the meaningfulness of work through its focus on people's lives, societal norms, valued work outcomes and goals, and self-identification with the work role.

This article is organised as follows. First, we explain the key elements and approaches of the Meaning of Work theory and how it can help understand intrinsic work motivation in later lifestages. Next, we discuss the findings of the most recent research regarding post-retirement work in Chile. We then describe the methodology used in this study, while results are outlined in the subsequent section. Finally, in the last section we discuss our results in light of the theoretical framework and make suggestions in the form of practical implications as to how employers might address the specific intrinsic motivations identified in this study.

Theoretical background

Older adults' employment and participation in economically productive activities are closely related to the active ageing approach (Deeming, Reference Deeming2009). As stated in a policy framework elaborated by the World Health Organization (2002: 12), ‘active ageing is the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age’. The active ageing approach refers to older adults' participation in diverse areas, including economic, social or spiritual affairs, thus moving from a passive and dependent way of life in old age towards an engaged and dynamic lifestyle (Foster and Walker, Reference Foster and Walker2013; Foster, Reference Foster2018). Further, several studies found that staying economically active beyond legal retirement age can promote the physical, mental and social wellbeing of older adults (Rohwedder and Willis, Reference Rohwedder and Willis2010; Shura et al., Reference Shura, Opazo and Calvo2022), an idea that is also reinforced in one of the latest works by Phillipson (Reference Phillipson, Lain, Vickerstaff and van der Horst2022). Therefore, an active ageing approach with its particular focus on older adults' economic activities can facilitate a better understanding of extended careers, challenges and opportunities encountered by an ageing population in this regard (Foster and Walker, Reference Foster and Walker2013).

Since one of the targets of active ageing is to encourage older people to remain engaged in the labour market because this could contribute to a more active and healthy lifestyle, it is important to analyse which factors, both intrinsic and extrinsic, facilitate older adults' work engagement. There has been a broad agreement in the literature differentiating between intrinsic and extrinsic work motivation, that could broadly apply to all individuals (Loo, Reference Loo2001; Rosso et al., Reference Rosso, Dekas and Wrzesniewski2010; Catania and Randall, Reference Catania and Randall2013). While extrinsic motivation refers to explicit factors that manifest themselves as economic rewards or recognition, intrinsic motivation to work is usually described as an inclination to perform labour activity that stems from the work experience itself, such as challenge, or personal interest (Catania and Randall, Reference Catania and Randall2013; Akkermans et al., Reference Akkermans, de Lange, van der Heijden, Kooij, Jansen and Dikkers2016).

It is particularly on intrinsic motivation that many scholars have focused their research in order to understand and explain the meaningfulness of work. Nevertheless, there is still no consensus upon a clear definition of meaningful work (Weeks and Schaffert, Reference Weeks and Schaffert2019), mainly because there are many definitions of work meaningfulness varying according to age, gender, and educational and cultural background. Notwithstanding the above, there have been remarkable attempts to create an all-encompassing theoretical model that would help explain aspects that define meaningful work. One of the most significant approaches was developed by Lips-Wiersma and Morris (Reference Lips-Wiersma and Morris2009), who used two dividing axes of ‘self’ versus ‘other’ and ‘being’ versus ‘doing’ to explain the principal sources of meaningfulness in work. Hence, their meaningful work model, also known as the Comprehensive Meaningful Work Scale, is divided into four quadrants, namely ‘developing and becoming self’ (self/being), ‘expressing self’ (self/doing), ‘unity with others’ (others/being) and ‘serving others’ (others/doing). All four sources contribute to creating work meaningfulness across different generations and occupations (Lips-Wiersma and Morris, Reference Lips-Wiersma and Morris2009; Weeks and Schaffert, Reference Weeks and Schaffert2019).

Another significant effort to explain the importance of intrinsic motivation sources can be attributed to Jahoda's latent deprivation model (Jahoda, Reference Jahoda1982) that is considered as one of the most prominent approaches for understanding the meaningfulness of employment (Paul and Batinic, Reference Paul and Batinic2010; Wood and Burchell, Reference Wood, Burchell and Lewis2018). This theoretical approach, also known as social-environmental or latent consequences model, not only identifies the latent functions that intrinsically stimulate people to remain in their workplaces, but also explains how those functions influence their psychological wellbeing. Although it recognises the existence of a manifest function that refers to financial income, Jahoda's framework argues that real work meaning stems from five latent, underlying functions, namely time structure, enforced activity, social contact, collective purpose, and status and identity (Jahoda, Reference Jahoda1982; Wood and Burchell, Reference Wood, Burchell and Lewis2018). These five latent functions are likely to satisfy social and psychological needs, with a subsequent increase in people's psychological wellbeing and employment being the primary source of these latent functions (Creed and Macintyre, Reference Creed and Macintyre2001; Paul and Batinic, Reference Paul and Batinic2010; Wood and Burchell, Reference Wood, Burchell and Lewis2018). Therefore, individuals who find themselves out of the labour market are likely to experience distress resulting from the non-fulfilment of these basic human needs (Jahoda, Reference Jahoda1982; Paul and Batinic, Reference Paul and Batinic2010).

As mentioned above, the role of intrinsic and extrinsic factors in meaningfulness of employment is likely to vary according to age, gender, and educational and cultural background. The contrasting results of previous research highlight this. For example, while Creed and Macintyre (Reference Creed and Macintyre2001) identified financial rewards as the main predictor of psychological wellbeing, other scholars have argued that the importance of extrinsic rewards decreases as one gets older (Kanfer and Ackerman, Reference Kanfer and Ackerman2004). This was confirmed by a study conducted in the Polish context, which concluded that ‘older workers were less insistent on financial gratification than others’ (Łaszkiewicz and Bojanowska, Reference Łaszkiewicz and Bojanowska2017: 83). A study conducted in Russia by Linz (Reference Linz2004) revealed that older Russian employees valued extrinsic rewards more than their younger counterparts. Another study conducted in Malta found out that the country's workforce was driven by intrinsic factors to a greater extent than by extrinsic ones, independent of chronological age (Catania and Randall, Reference Catania and Randall2013).

Likewise, Lopez and Ramos (Reference Lopez and Ramos2016) revealed that all categories of the Comprehensive Meaningful Work Scale tended to be equally important to individuals, independent of their age. Michaelson et al. (Reference Michaelson, Pratt, Grant and Dunn2014) argued that gender, age and family status were some of the aspects that were likely to affect the perception of work meaningfulness, encouraging scholars to conduct more research in this field, taking into account generational and gender differences. Similarly, a literature review conducted by Lyons and Kuron (Reference Lyons and Kuron2014: S153) presented evidence that there were significant differences in the workplace in terms of age, particularly when it came to employees' ‘personality, work values, attitudes, career expectations and experiences, teamwork, and leadership’, which could affect the definition of ‘meaningful work’ across generations.

Therefore, given this conflicting evidence, it seems that the meaningfulness of work is likely to be ‘determined by persons' individual choices and experiences and by the organisational and environmental context in which they work and live’ (Harpaz, Reference Harpaz1998: 146), an idea strongly supported by several scholars in the work-related research field (Hofstede et al., Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010; Weeks and Schaffert, Reference Weeks and Schaffert2019). Moreover, it is particularly important to study extended careers with a gender perspective due to the historical gender division of work that has accentuated social and cultural gender roles, placing women in a disadvantaged position in the labour market when compared to men (Burnay et al., Reference Burnay, Ogg, Krekula and Vendramin2023; Lain et al., Reference Lain, Vickerstaff and van der Horst2022). One strong link that has been drawn in this regard is the thesis of cumulative disadvantages, which identifies the mechanisms and pathways through which inequalities persist and deepen over time (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer2003). Due to a number of disadvantages accumulated over time, such as discontinuity caused by care-giving duties or lower occupational status associated with less-attractive reward systems, women are more likely to encounter unfavourable working conditions at older ages. These cumulative disadvantages, particularly influential in the lives of women, tend to dictate their post-retirement work decisions to a greater extent when compared to men (Galkutė and Herrera, Reference Galkutė and Herrera2020).

In this sense, due to women's cumulative disadvantages over the lifespan, it is expected that their meaningfulness of work may differ to some extent from that of men. Thus, work meaningfulness and, consequently, the intrinsic motivation to continue working beyond the legal retirement age, tend to be sensitive to gender and cross-cultural differences (Ní Léime and Ogg, Reference Ní Léime and Ogg2019). Burnay et al. (Reference Burnay, Ogg, Krekula and Vendramin2023) also argue that women are more likely than men to take into account their partner's retirement decisions when making their own, which supports the need to analyse extended careers in the light of gender differences. Therefore, when conducting research on older adults' intrinsic motivation to continue working, it is crucial to incorporate a gender perspective and consider the country's particular social, cultural, political and economic context that tends to shape people's perceptions, motivations and behaviour towards work.

Extended careers in the Chilean cultural context

In relation to formal work, one of the main characteristics of the Chilean labour market is the lack of part-time and flexible job opportunities, with full-time employment being the most commonly available formal work option (Madero-Cabib et al., Reference Madero-Cabib, Undurraga and Valenzuela2019). Moreover, job quality in Chile has always been low, compared with other countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2018). While these drawbacks tend to characterise the entire labour force in Chile, some specific groups of workers, such as working mothers or older workers are likely to be the most negatively affected by such employment features. It has been reported that older Chilean men are more likely to work for an employer, either in the public or in the private sector, while older women more frequently tend to be self-employed, which might reflect, to some extent, unequal opportunities in accessing formal employment among men and women. In addition, retired Chileans favour part-time jobs, while those in the younger age groups prefer having full-time jobs (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Abusleme, Arenas, Berwart, Fernández, Kornfeld, Madero-Cabib, Quesney, Rojas, Rojas and Belloni2018).

Financial reward is a crucial factor that stimulates older Chilean adults to remain employed. As some scholars have acknowledged (Vives et al., Reference Vives, Gray, González and Molina2018), extremely low pension replacement rates (nearly 38% for men and merely 33% for women), lack of governmental benefits for old age and excessively high drug prices make it hard to make ends meet once one retires from employment. In fact, OECD reports demonstrate that Chile presents much higher post-retirement work rates when compared to other countries (OECD, 2018), which can be closely related to the above-mentioned economic necessity at the older stages of life. Therefore, there has been a widespread assumption that extrinsic factors, such as financial rewards and benefits, are the main motives that drive older Chilean adults to extend their careers (Vives et al., Reference Vives, Gray, González and Molina2018), neglecting, to some extent, the role of the intrinsic motivation to do so.

While some proposals to extend careers have been made in recent government mandates in Chile, they have not been implemented in legal practice (Madero-Cabib et al., Reference Madero-Cabib, Undurraga and Valenzuela2019). In this sense, considering that there are no public policies specifically targeting post-retirement work in Chile, a major need arises to examine the intrinsic motivations of extended careers.

The Fifth National Survey of Older People's Quality of Life in Chile before the COVID-19 pandemic showed that two-thirds of the older Chilean adults who were working intended to continue working even if they did not have an economic necessity. Furthermore, 26 per cent of older adults who did not work indicated that they would be available and willing to do so (UC-Caja Los Andes, 2020). These findings suggest that many older people in Chile seem to feel intrinsically motivated to continue working, but the labour market might not offer the right conditions to suit their needs, ‘pushing’ them towards informal employment.

Although the above-discussed studies offer considerable insight into the general employment patterns among older adults in Chile, their intrinsic motivation to continue working remains under-researched. Moreover, there is a clear lack of qualitative studies conducted in the Chilean context with older adults, thus, further research is required to gain a deeper understanding of their personal experiences in the labour market.

In view of the accelerated population ageing process Chile is experiencing, the lack of public policy interventions aimed at extending careers, low pension replacement rates and very limited literature existing on post-retirement work in this country, this research aims to provide valuable insight into intrinsic work motivation among older Chilean adults, highlighting important gender and occupational differences.

Methods

This qualitative study represents the second phase of a larger mixed-methods investigation of the factors associated with post-retirement work in Chile. Guided by the findings of a previous quantitative study, which demonstrated the relevance of intrinsic motivation to continue working among older people (Galkutė and Herrera, Reference Galkutė and Herrera2020), we designed a semi-structured interview guide. The fieldwork took place between September and December 2019, having been previously approved by the ethics committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

Although our main goal was to discover and deepen the understanding of work meaningfulness and older adults' intrinsic motivations to extend their careers, it was also considered important to explore other work and personal life-related aspects in order to get a better insight into how these spheres interact and complement each other. Thus, the topics discussed during the in-depth face-to-face interviews include participants' work trajectories, the characteristics of the current job, extrinsic factors valued in the current job, intrinsic motives to continue working, perceived work–life balance, and views about current public and work policies concerning older people. Although the interviews were guided by semi-structured predetermined topics and questions, the interview participants were encouraged to introduce new topics and expand on issues that seemed relevant to them.

The selection criteria for the participants was to be formally employed and over the legal retirement age. The snowball technique was used for sampling, identifying potential participants first through personal contacts, with these participants then acting as ‘gate-keepers’, enabling the researchers to recruit their referees with similar characteristics. This process was repeated until the sample reached saturation.

The interviews were held at locations most convenient for the interview participants, usually their workplaces, their homes or nearby coffee shops. Before starting the interview, the participants were required to sign an informed consent form. It should be noted that some participants did not know how to read. In such cases, the researcher read the informed consent form aloud and received verbal consent from the participants, which was audio-recorded. The interviews lasted between 45 and 100 minutes. There was no monetary reward for participating in the study.

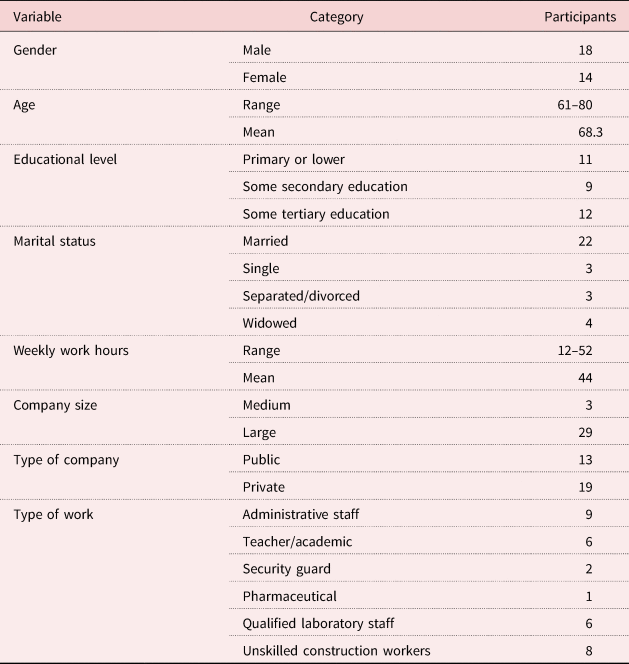

A total of 32 interviews were conducted, including 18 men and 14 women. All participants lived in Santiago, Chile. As we aimed to achieve greater variety among the research participants (following the maximum variation sampling strategy suggested by Patton, Reference Patton2002), they were purposively recruited from public and private sectors, with divergent occupational backgrounds including educational, scientific, secretarial and construction fields, among others. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the participants. In order to protect their anonymity, no personal information is disclosed, such as the real names of the participants or those of their organisations. All the interviews were transcribed, and the data were then analysed applying the thematic analysis method (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), using the software package ATLAS.ti 8 for the initial open coding and formulation of categories. The data analysis took place simultaneously with the data collection process, applying a constant comparative iterative method among codes and emerging categories, which enabled the researchers to identify gaps and to address them in subsequent interviews.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

Note: N = 32.

Results

During the data analysis, three main emerging themes were identified: (a) the meaning that work gives to life; (b) future projects and post-retirement orientations; and (c) work as the main source of social interaction. These topics are presented and further discussed below.

The meaning of work

When asked about the positive aspects besides the financial rewards that work brought to older people's lives, the most frequently mentioned feature was personal satisfaction from feeling useful.

First, the majority of the respondents expressed in different ways that their work entailed personal satisfaction. This personal satisfaction seemed to emerge from a sense of usefulness, as these two concepts were usually mentioned together, as stated by one participant: ‘Personal satisfaction, feeling useful, feeling that I am worthwhile, that I am going through life…’ (R1, female, 62, medium-educated, administration field). Similarly, another participant reinforced this idea:

I feel useful. I think I am doing it well and I am doing it for the welfare of many other people … Thus, I feel useful, that is why I feel satisfied. (R12, male, 69, highly educated, scientific field)

Personal satisfaction in older Chilean adults was often linked to the possibility of helping others, indicating that personal satisfaction is likely to arise from the feeling that the work performed by older adults has a positive impact on other people's lives. This was evident in the following respondent's answer:

Even if it means solving a problem via the phone. I like that. It makes me feel good. I feel like if I help someone, it was a good day. For me, that is rewarding … if someone calls me saying ‘I have a problem’ and I can help them solve that problem, it is silly really, but the person leaves happy! And I like that. (R22, male, 67, medium-educated, administrative field)

Although this sense of usefulness that brought the feeling of satisfaction was mentioned by participants of both genders and of different education levels, it was more frequent among those who worked in the education sector and those who performed customer service-related tasks, thereby, having more frequent contact with other people. As one female respondent who worked with children in a primary school said:

There is a dynamic; it matters whether you are here or not. You make a difference. In this job I know I make a difference by being here. So that gives me plenty of satisfaction. (R23, female, 66, highly educated, education field)

Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that a considerable number of blue-collar workers declared that they continued working because they had worked their entire lives, relating their post-retirement career decisions to usual practice or regular habit, rather than to deep satisfaction stemming from their work. Rather than being engaged with their specific job tasks, these interviewees were likely to be committed to working with something they were used to doing and could not imagine their lives without it. This pattern could also be noticed among some medium-educated older workers, performing routine-based roles, as expressed by one participant stating: ‘Because I have worked all my life – I have worked since I was 17 – so it is somewhat weird to stay at home and do nothing’ (R24, female, 70, medium-educated, administrative field). Therefore, more than a source of profound personal satisfaction and fulfilment, post-retirement work is likely a way to avoid inactivity for non-professional older Chilean workers. This was especially observed among the male interviewees.

Future projects and post-retirement orientations

In some cases, work was likely to be perceived as the best option when compared to the opposite extreme of staying at home and doing nothing. A large number of respondents confessed they were afraid of retirement, as they had not prepared themselves emotionally and psychologically for this period. For example, one male respondent who worked as a security guard explained: ‘I am afraid. Why? Because I would not want to stay in bed until 12 pm, watching TV, getting up for lunch, and doing nothing. That worries me; I do not want that to happen to me’ (R2, male, 68, low-educated, security field). Thus, the absence of future projects and not having alternative activities that could substitute the role of work motivated many respondents to continue working beyond the state pension age in Chile. Interestingly, the absence of plans and projects, and the complete concentration on their current jobs as the main and only activity could be noticed among older people from diverse occupations and educational backgrounds. For instance, a man who worked in the administrative field revealed: ‘Other people may have thought about travelling or doing business, while in my case I do not have any trade, business or extra activity planned that would allow me to keep my mind active’ (R22, male, 67, medium-educated, administrative field). Similarly, another highly educated respondent supported this idea by clarifying:

I also did not do the mental exercise of putting myself in an inactive situation at home. I do a lot of manual tasks, repairs, house maintenance, gardening, even cleaning. My wife and I share all the tasks. But still, they are not full-time jobs that would satisfy me in the event of retirement. That is the other important reason. (R14, male, 72, highly educated, scientific field)

Although some women expressed their worries about inactivity during retirement, this pattern was noticeably more common among male respondents. Hence, the complete focus on economic activity throughout their lifespan, in the case of men, makes it somewhat more problematic for them to withdraw from the labour market, as they find it more difficult to encounter other activities as fulfilling and enjoyable as their job tasks had been throughout their working lives. It is also important to mention that only one of the 32 participants had part-time employment during the study period. Most male respondents not only exceeded the maximum weekly work hours by voluntarily staying in their workplace longer due to their job engagement, but two of them even had an extra job during the weekends as a hobby. Therefore, it appeared that male interviewees were more likely to focus exclusively on economic activities, with gainful employment being the only way for them to maintain their personal and social identities, as compared to the female interviewees.

On the other hand, while some female respondents also recognised that they had not carefully planned their retirement stage, it was much easier for them to come up with alternative ways of staying engaged. Going out with friends, volunteering in organisations, exercising or travelling were some of the options mentioned by the female interviewees. Even though they found their jobs enjoyable and satisfying, many older women were clear at what age they would like to withdraw, not turning so much to the option of working ‘as long as their health allowed it’, which was a more common response among the men. One respondent who worked as a part-time lecturer explained:

The municipality has many courses, workshops … those things you cannot enjoy when you have a schedule. Well, there is something I am doing recently, but I still have a long way to go … for example, I do not know Europe … Travelling is the most enriching thing one can do. I shall dedicate myself to travel. (R4, female, 65, highly educated, education field)

The existence of alternative goals, not related to the main job, clearly affected female respondents' intrinsic motivation to continue working, as expressed by one participant:

I have other interests out there too. I paint with watercolours and I study Russian. So I have something to develop. A goal, shall we say. So if I had the financial security and saw that painting with watercolours could be in my future development, I would stop working. But, otherwise no, because it is fun here. (R23, female, 66, highly educated, education field)

Therefore, it seems that female respondents, as compared to their male counterparts, were more likely to have work–life balance, presenting a wider array of alternative lifestyle activities able to substitute, to some extent, the enjoyment and fulfilment achieved in the workplace.

Work as the main source of social interaction

Social ties in the workplace and connectedness with society in the broader sense were crucial aspects of understanding retirement-age Chilean adults' intrinsic motivation to continue working. The most featured aspects were related to the possibility of leaving home, intergenerational relations at work and good relations with direct employers.

First, having a paid job for some interviewees meant maintaining their daily routines, which included taking public transport, communicating with citizens while on their way to the workplace or observing other people in the city. A 74-year-old female accountant explained: ‘For the fact that you leave the house. The same act of getting on the subway, walking, seeing how people have changed. This thing is attractive’ (R11, female, 74, medium-educated, administrative field). Thus, even in cases where the role performed at work did not involve much interaction with other colleagues, the possibility to keep in touch with the society was still a highly appreciated feature that stimulated the interviewees to continue working.

Correspondingly, good relationships at the workplace established over many years were one of the key motives to remain employed, as mentioned by many of the respondents. Some of them expressed the importance of work-based relationships, sometimes even referring to their colleagues as family members. Interestingly, this was particularly common among most blue-collar male workers who attributed particular importance to their work relationships. For example, one participant stated: ‘In construction, one becomes like a family, because you spend more time at work than at home, like any other job too’ (R17, male, 69, low-educated, construction field). This view was shared among different construction workers, many of whom insisted that ‘work is a second family that you create’ (R31, male, 70, low-educated, construction field).

The rest of the interviewees also placed a great deal of emphasis on social interaction at work, where good relationships and the absence of conflicts were critical factors in post-retirement work motivation. For example, when asked what he liked most about his job, a 70-year-old male respondent explained: ‘As I said before, the social contribution, personal relationships, collaborations, etc. It is something that thrills me’ (R21, male, 70, highly educated, scientific field). This view was supported by other interviewees, both men and women with widely divergent professional backgrounds, who stated that they were willing to interact with other people, and that they enjoyed the social contact at their workplaces, referring especially to their colleagues.

Along the same lines, it is noteworthy that the interviewees, who worked in education or scientific fields, or in other fields involving constant interactions with younger colleagues, often acknowledged the relevance of intergenerational relations. A 62-year-old secretary who worked in a large public organisation is only one of many such examples:

I love relating to younger people, always. I like it, because it is positive and I laugh with them. Same here with the younger colleagues. I have always liked relating to younger people … those young people who came along taught me and I have learnt a lot from them. (R32, female, 62, medium-educated, administrative field)

Some interviewees pointed out that they did not like interacting with people their age since their conversations tended to be more pessimistic and complaining, whereas talking to younger adults brought vitality, positive energy, the capacity of adaptation and learning new things.

The idea of continuous learning through social interaction was expressed by numerous respondents, such as in the case of one older woman who performed the role of dean's secretary at a private secondary school:

I have developed myself, I have learnt a lot, I have contacted many people and also many people who have different skills, you see? It is about people better than yourself, so you are learning. (R26, female, 62, highly educated, administrative field)

The possibility to learn new things and to continue developing their skills was also mentioned by several unskilled construction workers. One of them explained:

I think what it [work] brings is knowledge, knowledge regarding construction. Because, as I was saying, there are so many new things here, that one learns in construction. And if you stay home, you will not learn anything! All you will learn is to waste time. But not here, because suddenly things come up that you did not anticipate, so that is good. (R29, male, 70, low-educated, construction field)

Therefore, social interaction that brings along the possibility to keep updated seems to be equally appreciated by both Chilean men and women with divergent educational backgrounds.

Likewise, a good relationship with the direct employer was another facet mentioned by various respondents as influencing their motivation to continue working. For instance, one female interviewee attributed her decision to keep on working to the attachment she had to her employer:

She [employer] asked me not to leave: ‘Stay while I take this challenge. We have worked well together. You cannot leave me alone right now.’ And I am infinitely fond of her. And I said: ‘It is not so terrible. I shall stay with her for a while…’ (R4, female, 65, medium-educated, administrative field)

This kind of strong psychological contract and personal engagement with the direct employer was particularly acknowledged by women who worked in large organisations. Notwithstanding the size of the company, these women explained that the unit they worked for was small and thus the relationships within the unit were friendly and gratifying even with the managerial staff. It seems that good vertical communication contributed as an essential component of the rewarding work environment. Another representative example of the importance of vertical communication was a female respondent who continued working as a part-time lecturer:

We are evaluated by our employers, and I have always been very well evaluated. Even a few months ago, I was congratulated because I had been recognised as the best lecturer in that module. And that is quite good now because one needs recognition. And they [employers] are always telling you that. So there is positive feedback there. (R3, female, 67, highly educated, education field)

These examples clearly demonstrate the relevance of the psychological contract built between the employee and the employer, strengthened by the existence of effective vertical communication, which reshapes the value that older adults attach to their work environment, creating it as a peaceful and pleasant place to stay.

Discussion

In light of deteriorating pension funds around the world, there is an increasing need to continue working in old age, which implies the promotion of healthier and more active lifestyles among older adults. In this context, there has been a recent call for more research to be conducted on post-retirement work in different countries, especially from a qualitative perspective (Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Farrow and Blank2012; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Phillipson2016; Sewdas et al., Reference Sewdas, De Wind, Van Der Zwaan, Van Der Borg, Steenbeek, Van Der Beek and Boot2017), taking into account how the motivation to work might differ across divergent work contexts (Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, De Lange, Jansen, Kanfer and Dikkers2011; Deery et al., Reference Deery, Kolar and Walsh2019).

So far, there has been a widespread assumption that financial rewards and benefits have been the main motives that drive older Chilean adults to extend their careers (Vives et al., Reference Vives, Gray, González and Molina2018), neglecting the role of the intrinsic motivation to do so. In this sense, one of the main contributions of this study is revealing these older Chilean adults' intrinsic motivations to extend their careers, highlighting important gender and occupational differences.

Since there are no previous papers published on older workers' intrinsic motivations to extend their careers in Chile, it is important to compare the present findings with the results of other studies exploring this topic in order to observe the similarities and differences among different countries, highlighting the unique contributions of this study. This would enable making suggestions for employers and policy makers in Chile, helping generate more favourable workplace conditions for older workers.

A majority of older workers in the present study revealed that the satisfaction they felt in their work stemmed from the sense of usefulness they experienced. More concretely, this sense of usefulness was often linked to the opportunity to help others. This latter finding supports one of the meaningful work theoretical model ideas developed by Lips-Wiersma and Morris (Reference Lips-Wiersma and Morris2009), specifically representing the quadrant of ‘serving others’ (others/doing), which refers to the eagerness to make a difference by contributing to other people's wellbeing. This need to feel useful and help others as one of the main drivers to continue working was not identified in previous, mainly quantitative, studies in other cultural contexts, including Russia (Linz, Reference Linz2004) or Malta (Catania and Randall, Reference Catania and Randall2013).

Further, the present findings also reveal how the meaningfulness of work might differ across occupations and job sectors (Deery et al., Reference Deery, Kolar and Walsh2019). By interviewing older workers from different sectors, thereby maximising the heterogeneity of the sample, we were able to discover that blue-collar older Chilean workers and those who performed more routine-based tasks were more likely to perceive post-retirement work as a way to avoid inactivity. As suggested by Reynolds et al. (Reference Reynolds, Farrow and Blank2012: 82), blue-collar workers in the United Kingdom ‘did not necessarily gain deep satisfaction from their work roles’, it is predominantly about their willingness to remain economically active per se, since it is something they have done their entire lives, as was observed in the present data as well. It seems that blue-collar Chilean workers derived meaning from their jobs primarily in terms of continuity and consistency. Contrastingly, when compared to other professions, those working in the education and customer service-related sectors seemed to be more driven by the willingness to make a difference, which is consistent with the ideas enumerated by Reynolds et al. (Reference Reynolds, Farrow and Blank2012). The above-mentioned findings have a strong resonance with Dannefer's (Reference Dannefer2003) cumulative disadvantage theory, in the sense that they show how disadvantages accumulated over a lifetime (e.g. adverse employment histories, lower occupational status) affect the meaning of work in later life.

Further, the data also showed that personal satisfaction within the workplace could be gained through the opportunity to keep updated. Interestingly, in contrast to what could be expected, our findings demonstrated that blue-collar workers were as driven by continuous learning and development opportunities as professional workers. A possible explanation for this latter finding might be related to a variety of tasks performed by non-professional workers. As explained by Deery et al. (Reference Deery, Kolar and Walsh2019: 644), in the case of employees whose jobs require performing dirty tasks, ‘varying job tasks often provide new challenges and a sense of meaningfulness at work as they augment employees' abilities and skills’. The present evidence suggests that, although often seen as inflexible and resistant to change, older Chilean workers from both professional and non-professional occupations are likely to derive their meaning of work and job satisfaction from continuous learning and developmental opportunities, as well as the eagerness to transfer their knowledge to others. In this sense, workplace can be seen as one of the key environments to promote lifelong learning and skills updating among older adults, fostering their active ageing, as pointed out by Burnay et al. (Reference Burnay, Ogg, Krekula and Vendramin2023).

Furthermore, another important finding of this study is related to the desire to continue working as a reaction to the concern of staying at home and doing nothing. Male respondents were most likely to report that they were unprepared for the retirement period. It may well be that, unlike older women, due to the deeply rooted male breadwinner role in the Chilean context (Madero-Cabib et al., Reference Madero-Cabib, Undurraga and Valenzuela2019), men have not been able, throughout their lifetimes, to find alternative activities capable of fulfilling both their psychological needs and time schedules. This is related to Jahoda's (Reference Jahoda1982) argument that time structure is one of the most relevant latent aspects that help explain work meaningfulness, in the sense that all adults need clear time frameworks filled with programmed activities, which increase their overall wellbeing. The importance of structuring the day through work was also stressed in a recent study by Lain et al. (Reference Lain, Vickerstaff and van der Horst2022). It seems that work tasks constitute a powerful daily routine for most older people, particularly men, which cannot be easily substituted by other leisure or housekeeping activities because of the meaning embedded in the work. These results also support the idea that a gender perspective is crucial in research on extended careers, as explained by Ní Léime and Ogg (Reference Ní Léime and Ogg2019: 2), since ‘gender norms, roles and responsibilities result in specific outcomes’ in extended working lives, especially in the case of women, whose work trajectories have been more often disrupted when compared to men. Therefore, our study highlights the importance of considering different forms of employment in Chile, such as bridge employment, which may be better aligned to the needs of specific groups, as shown by the results of this study, particularly in the case of Chilean men.

Finally, there was also a clear underlying gain, expressed by a majority of the respondents, derived from social engagement with others, particularly with co-workers and, to a lesser extent, with employers. This is consistent with recent research by Deery et al. (Reference Deery, Kolar and Walsh2019), which showed that social relationships within the workplace had a positive effect not only on the job satisfaction of the less-qualified workers but also on their dignity. The possibility of meeting and sharing time with people was also emphasised as an appealing activity to older adults in a recently published book by Lain et al. (Reference Lain, Vickerstaff and van der Horst2022). Hence, this finding confirms another essential latent function of employment proposed by Jahoda (Reference Jahoda1982), namely social contacts. According to Jahoda, a sense of belonging in a broader social context through economic activity cannot be easily substituted by other relationships (e.g. family members) since it ‘provides more information, more opportunity for judgement and rational appraisal of other human beings with their various foibles, opinions, and ways of life’ (Jahoda, Reference Jahoda1982 in Paul and Batinic, Reference Paul and Batinic2010: 48). Moreover, our results also contribute to the intergenerational relationship theories in the work-related context as our participants revealed the relevance of intergenerational relations at work, which tend to bring them vitality, positive energy, as well as adaptation and continuous learning.

Limitations and future research

Despite the theoretical implications of this research, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, the fieldwork was limited to older workers living and working in formal settings in Santiago, Chile. Therefore, this study leaves out a large proportion of older workers in the informal sector of the economy. Furthermore, it is essential to bear in mind that work and life conditions in a metropolitan city such as Santiago are likely to be considerably different from those in the rest of the country.

It is also important to note that by purposively including interview participants with divergent occupational backgrounds we aimed to offer a first overview of intrinsic motivation to continue working of older Chilean adults, a largely understudied topic in this country. However, sample heterogeneity prevented us from conducting in-depth analyses, which could be developed further in future research.

Interestingly, some factors associated with working conditions did not appear in the interviews, probably because the interview participants either had work conditions suitable to their needs or they had adjusted their expectations to the unfavourable conditions. The need for job flexibility (OECD, 2018) did not appear as relevant in the interviews either, indicating that it is perhaps a demand for early retirees rather than for post-retirees.

Given the evidence above, we identify several opportunities for future research. Since work-related demands and concerns differ widely across people according to their age, gender, social class and occupation (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Errasti-Ibarrondo, Low, O'Reilly, Murphy, Fahy and Murphy2020), more studies are needed to explore in depth the diversity of meanings that older adults might attribute to work. In particular, a future investigation could focus on how the meaningfulness of work is enacted by workers engaged in low-quality or informal jobs and how meaningfulness in such contexts may differ from that in high-quality and formal jobs. Likewise, future research could explore specific job characteristics or types of work that are more appealing to older adults in Chile from a gender perspective, which would provide valuable information for employers and policy makers.

It is important to note that this study focused on older Chilean adults who continued to be economically active. Due to the lack of research on post-retirement work in Chile, it would also be valuable to investigate the experiences of older adults who are already retired but willing to find employment, giving insight into their intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, as well as the barriers they face in the labour market.

This study also showed that older Chilean adults were keen to continue learning, contrary to the prevailing general perception about them being inflexible and resistant to change. It would therefore be valuable if future studies were to analyse how societal attitudes and cultural values influence older adults' decisions to continue working, and whether these cultural values affect their intrinsic motivation.

Finally, it is worth considering whether these motivations to continue working identified during the global COVID-19 pandemic remain unchanged in a post-COVID-19 era, especially among the workers who carry out remote work. For example, if one of the main motivations is contact with other people in a physical workplace, it is possible that by diluting these face-to-face contacts, older workers may be losing their motivation to work.

Therefore, further research is necessary to overcome the above-mentioned limitations and gain a comprehensive understanding of post-retirement work motivation in Chile and other contexts.

Conclusion and recommendations

This research sheds new light on the complex interaction between intrinsic work motivation, gender and occupational differences in Chile, a country with an accelerated ageing process and an absence of public policies aimed at extending careers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on older workers' intrinsic motives to extend their careers in Chile. The findings of the present research enable making suggestions for employers and policy makers in the country, helping generate more-favourable workplace conditions for older workers.

One of the main findings of this research is that older Chilean adults value experiencing a sense of usefulness with respect to others, which was particularly common among the white-collar workers, regardless of gender. This suggests that work meaningfulness differs across occupations. On the other hand, gender differences could be clearly observed with regards to post-retirement orientations and the capacity to replace employment with another equally significant activity, suggesting that men may value a gradual retirement plan to a greater extent when compared to women. Another key finding of this research is that both professional and non-professional older workers were driven by continuous learning and development opportunities, which indeed challenges negative ageist stereotypes of older people not being interested in upgrading their skills.

There are several recommendations in the form of practical implications as to how employers might address the specific intrinsic motivations outlined here. It would be highly beneficial to create intergenerational work environments that enable interaction between younger and older generations, also facilitating knowledge transfer. It is also crucial to implement phased retirement policies in the workplace, which would especially help men in their transition to full retirement, and promote women's likelihood of extending their careers. We also recommend focusing older adults' jobs, when possible, on problem-solving tasks that assist others, as social interaction and helping others was one of the main motivators identified in this research. Finally, employers should pay special attention to the importance of vertical communication, reinforcing older employees' motivation through continuous positive feedback.

Author contributions

MG collected and analysed the data, as well as took the lead in writing the manuscript. MSH supervised the project and performed the critical revision of the article.

Financial support

This work was supported by the ANID (National Agency for Research and Development) (grant number 21180597); and FONDECYT (National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development) (grant number 1220936).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

This study was approved by the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile ethics committee (reference number 181206002).