Introduction

In the United Kingdom (UK) and other Anglo-Saxon countries it is increasingly argued that we are entering a period of choice and control with regard to work in later life. Whereas previously workers were often forced out of employment at age 65, the abolition of mandatory retirement ages in the United States of America (USA), UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand means that people now have the theoretical right to continue working (Lain and Vickerstaff, Reference Lain and Vickerstaff2015). In the USA, this is often allied to a portrayal of the ‘baby-boomer’ generation as being agentic and refusing to accept standardised paths out of employment and into retirement (Rix, Reference Rix and Hudson2008). In the UK, policy makers depict working longer as taking control and ‘reinventing retirement’ (Altmann, Reference Altmann2015; Cridland, Reference Cridland2016). In his interim review of UK State Pension ages, for example, John Cridland (Reference Cridland2016) highlights the fact that older people are disproportionately self-employed and/or part-time, relative to younger workers, and argues that moves into these types of employment represent the development of attractive pathways into extended working lives. However, whether or not people actually do move into part-time work and self-employment, and if so, whether this is the result of genuine choice, is not empirically examined in Cridland's report (although see Van der Horst et al., Reference Van der Horst, Lain, Vickerstaff, Clark and Baumberg2017).

The inevitable criticism of emphasising choice is that UK government policy means that many older people have little financial option but to continue working (Lain, Reference Lain2016). Demographic changes put pressures on state pension systems everywhere, which means governments are reforming pensions and raising state pension ages (Axelrad and Mahoney, Reference Axelrad and Mahoney2017). However, the speed and extent of UK State Pension age increases have been criticised by academic scholars (Macnicol, Reference Macnicol2015; Lain, Reference Lain2016), particularly as the broader welfare state is poor at providing decent alternative sources of income for those exited from work early (Lain, Reference Lain2016). State Pension ages are rising rapidly, and will reach 66 for men and women in 2020, 67 in 2028 and, ultimately, 70+ (The Guardian, 2017a). Salary-related occupational pensions have declined dramatically in the UK, and benefits for unemployment and ill health are only worth half that of the already low UK State Pension.Footnote 1

In contrast to this emphasis on choice and control in policy debates, an alternative argument is that older people are increasingly members of ‘the precariat’, following Guy Standing's (Reference Standing2011) book of the same name. According to Standing, a diverse range of groups have joined the precariat, including young people, ‘old agers’ and ethnic minorities. These individuals have jobs which lack security, both in terms of the prospects they provide for continued, long-term employment within an ‘occupational niche’, and in terms of a decent stable income. Older people are increasingly said to be entering the precariat by taking low-level jobs in older age, divorced from their previous careers, to supplement dwindling pension incomes.

Both positions presented above, of Standing (Reference Standing2011) and Cridland (Reference Cridland2016), view employment in older age as a period of change. The difference, however, is whether changes in older age are viewed as resulting from choice and control on the part of older people (Cridland, Reference Cridland2016), or whether individuals are being forced into precarious employment (Standing, Reference Standing2011). What both positions miss, however, is the sense of precariousness that older people in long-term jobs may experience in the context of increased pressures to work longer. This is important because prospects of finding new work in older age are actually relatively weak (Lain, Reference Lain2016; Lain and Loretto, Reference Lain and Loretto2016). It is our contention that, for a significant proportion of older workers, the pressure to work for longer, combined with limited alternative employment prospects, gives rise to a heightened sense of precarity.

This paper argues that in order to understand fully the lived experience of precarity amongst older workers in the UK, it is necessary to extend our focus beyond employment, and consider other aspects of individuals’ socio-economic circumstances. We argue that precarity is also located in the domains of the welfare state and the household – two crucial aspects of individuals’ socio-economic contexts which until now have remained under-explored in discussions of older workers and precarity. This is important because aspects of household circumstances (such as family composition and overall household income), in combination with relationship to the welfare state (such as level of pension provision), may serve to either reinforce or mitigate the effects of precarious employment. It follows from this that protecting individuals from precarity requires us to reconsider how the state and welfare state support individuals in making work and retirement choices. In this paper, we examine the intersecting influences of precarious jobs, precarious welfare states and precarious households upon older workers’ sense of ‘ontological precarity’ in the UK.

In developing the argument above, this paper proceeds in a number of stages. First, we briefly review recent research on precarity. We then develop a theoretical model for understanding precarity as a lived experience, which is influenced by the intersection between precarious jobs, welfare states and households. This model is then illustrated by drawing on empirical research with older workers in two UK case study settings: local government and hospitality. The implications of our analysis for future research and policy are discussed in the Conclusion.

Previous debates on precarity and precarious work

Since publication in 2011, Standing's book, The Precariat: The Dangerous New Class, has dominated debates about precarious employment. As Millar (Reference Millar2017) points out, Standing's work follows a number of researchers exploring precarious employment as a labour condition or outcome (see e.g. Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1998; Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2009; Vosko, Reference Vosko2010). In some senses Standing's work deviates from previous analyses by purporting to examine people with precarious employment as a class, who represent a potential ‘danger’ to the status quo (Millar, Reference Millar2017). The primary focus of Standing's book is, however, similar to much of the previous research: it identifies the characteristics of precarious employment and the factors influencing why people do it.

Standing (Reference Standing2011) argues that the precariat have jobs that lack three forms of security: ‘income security’ (decent stable incomes), ‘employment security’ (security from dismissal) and ‘job security’ (an occupational niche that can be further developed). Job security differs from employment security in the sense that it relates to opportunities for career progression, rather than security from dismissal. In addition, there are four broader forms of security of relevance – ‘labour market security’ (the availability of alternative jobs), ‘work security’ (protection from accidents, etc.), ‘skill reproduction security’ (access to training) and representation security (trade unions, etc.). It is argued that older people of ‘pension age’ are increasingly taking low-level, low-paid jobs in older age, divorced from their previous careers, in order to supplement their increasingly inadequate pensions. Older people can afford to take these lower-level jobs because they receive pensions. The book is presented as a form of theory building, and so no empirical evidence is presented for this assertion.

At the heart of Standing's (Reference Standing2011) argument is a contradiction. On the one hand, he views the precariat as a ‘dangerous class’, implying that they are unified in their anger and liable to take action. Standing (Reference Standing2011: 19–24) argues that they experience anger, anomie, anxiety and alienation. On other hand, he presents older people in the precariat as rather passive:

uninterested in career building on long-term employment security … They can take low-wage dead-end jobs lightly [because of pension income]. They are not frustrated by career-lessness, in the way youth would be. But older agers too may be grinners or groaners. (Standing, Reference Standing2011: 83)

According to this assessment, older ‘grinners’ do not want a ‘better’, more-demanding full-time career job; they are happy to be in a ‘precariat job’ that gives them ‘money for extras’ or a pleasurable activity to do (Standing, Reference Standing2011: 59). On the other hand, older ‘groaners’ are purely in employment for financial reasons, and they have limited job choices as they ‘face competition from more energetic youth’ (Standing, Reference Standing2011: 59).

This impression of ‘grinners’ and ‘groaners’ implies a range of psychological responses to being in the precariat, which do not necessarily imply that people feel a sense of precarity. However, the term ‘precarity’ arguably implies a form of uncertainty that impacts negatively on the psyche (Molé, Reference Molé2010; Millar, Reference Millar2017). Indeed, Standing's (Reference Standing2011) broader arguments about the precariat experiencing anxiety, anger, anomie and alienation seem to suggest this.

Millar (Reference Millar2017) identifies an interesting alternative to focusing on precarity solely as a ‘labour condition’ (e.g. a type of insecure work). Drawing on the work of Judith Butler (Reference Butler2004), Millar (Reference Millar2017) argues for a focus on ‘ontological precariousness’. Precarity can be related to ontological experience in the sense that the individual views their reality as being precarious. This reality is inherently multifaceted and roots any ‘labour condition’ in the individual's wider life. Thus, while a precarious ‘labour condition’ may contribute to feelings of ‘ontological precarity’, the extent to which an individual feels precarious will also depend on whether or not their wider life circumstances provide security. The concept of ‘ontological precariousness’ therefore aims to bridge the gap between viewing precariousness as a ‘labour condition’ and viewing precarity as a form of vulnerability or negative insecurity that is experienced by the individual. According to Miller (Reference Millar2017: 5), precarity is thus ‘both a socio-economic condition and an ontological experience … It aims to capture the relationship between precarious labor and precarious life’.

Theorising precarity

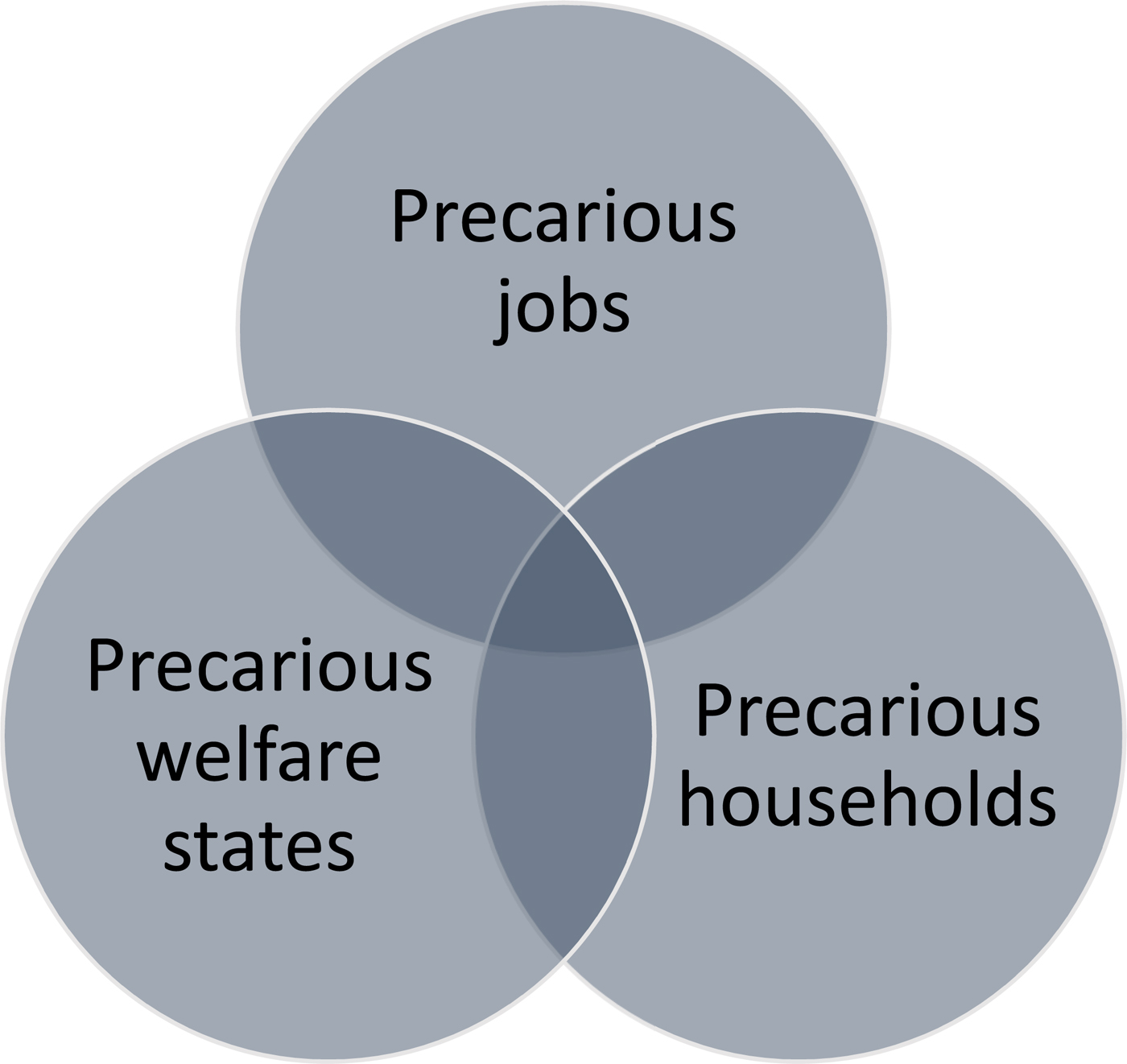

Extending Millar's (Reference Millar2017) approach, we argue that precarity as an ontological experience relates to precarious conditions in one or more domains of an individual's life. Such precarity may take the form of anxiety, whether mild or severe, which is partly anticipatory, i.e. it is grounded in a set of circumstances but also concerned with what may happen in future (Molé, Reference Molé2010). To fully make sense of precarity in the domain of employment, as a lived experience, it is necessary to take broader social context into account: precarious jobs, welfare states and households; this framework is represented by Figure 1. This suggests that precarity in one domain (e.g. employment) can be heightened/diminished by precarity/security in another domain (welfare states or households).

Figure 1. Mapping the intersections between precarious jobs, welfare states and households.

The model has been designed with reference to the UK, a country where precarity has arguably been exacerbated by pressures to work longer in the context of a relatively unregulated labour market (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001) and a welfare state that is ungenerous by international standards (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). However, as we discuss in the Conclusion, we believe the framework may be useful for understanding precarity in other countries as well to varying degrees, given pressures to work longer in the context of welfare state retrenchment (Vickerstaff et al., Reference Vickerstaff, Street, Ní, éime, Krekula, Ní Léime, Street, Vickerstaff, Krekula and Loretto2017: 227).

We discuss the three domains of precarious jobs, welfare states and households in turn.

Precarious jobs

The idea that work is becoming more precarious is not new and, as Fevre (Reference Fevre2007) notes, it follows in part from arguments made by social theorists that we have reached an age of insecurity (Beck, Reference Beck1992, Reference Beck2000; Castells, Reference Castells1996; Giddens, Reference Giddens1998; Sennett, Reference Sennett1998). While this perception has become common, empirical research in the period up to the mid-2000s seemed to contradict this argument, finding little statistical evidence of increases in perceived job insecurity, temporary employment or short-duration employment (Marsden, Reference Marsden1999; Fevre, Reference Fevre2007; Doogan, Reference Doogan2009). However, since the 2007/2008 financial crash, in some sectors of employment the threat of job loss has also increased significantly, most notably in the public sector following severe budget cuts (Wanrooy et al., Reference Wanrooy, Bewley and Bryson2013). At the same time, many of the jobs replacing those lost in the UK have been considered ‘low-quality’ part-time work or self-employment (Klair, Reference Klair2016), with the assumption that people (particularly men) were involuntarily recruited to these jobs.

We also need to consider ontological precarity in relation to the changing nature of work, however. For example, work intensification has increased in general across a range countries (Burchell et al., Reference Burchell, Ladipo and Wilkinson2005; Green, Reference Green2006), with people expected to perform more work per hour than in the past. This is because private-sector employers have become more competitive and market-orientated (Green, Reference Green2006) and employers in the UK public sector have to work with reduced budgets (Wanrooy et al., Reference Wanrooy, Bewley and Bryson2013). An outcome of this work intensification has been the restructuring of employment and tasks within many organisations and a significant decrease in UK job satisfaction among older workers (White and Smeaton, Reference White and Smeaton2016). Older workers may experience work intensification as a form of precarity because it becomes harder to perform in the context of pressures to work longer (Sheen, Reference Sheen2017). Such work may be viewed as unsustainable in the long term, particularly for stressful and physically arduous jobs, given declines in health as people age (Lain, Reference Lain2016).

However, simply focusing on the jobs that older workers do misses at least half of the puzzle – it is the jobs that are not available to older workers in the labour market that are just as relevant to individuals’ sense of precarity. Standing (Reference Standing2011) identifies the concept of ‘labour market insecurity’ – a lack of available jobs in the wider labour market. However, older people are arguably affected by this differently compared to younger groups. Older people may find that the type of job they do is no longer viable given declining health, but perceive few suitable alternative employment opportunities. Previous evidence suggests that older people anticipate that it would be hard to get another job (Smith, Reference Smith2000: 30; Loretto et al., Reference Loretto, Airey and Yarrow2017), which reflects the reality that older people find it harder to re-enter employment following unemployment (Lain, Reference Lain2016). In this context of limited recruitment prospects, average job tenure of UK workers aged 55–64 has risen from 14 to 14.5 years since 2007–2008. Long job tenure may be associated with a feeling of precarity because people feel that they have little option but to ‘cling on’ to their jobs because of limited employment prospects and a weak welfare safety net to catch them. This may mean staying in jobs that seem to be the antithesis of precarious employment – full-time, permanent jobs. Indeed, Bell and Rutherford (Reference Bell and Rutherford2013) found that UK workers over 50 were four times more likely to say they wanted to reduce, rather than increase, their hours of employment.

In sum, job precarity among older people may relate to job prospects for the future (inside or outside the current organisation) or the unsustainable content of the work itself. These changes have been exacerbated by recession (Axelrad et al., Reference Axelrad, Sabbath and Hawkins2018), budget cuts in the public sector (Wanrooy et al., Reference Wanrooy, Bewley and Bryson2013) and longer-term structural change in the labour market resulting from increased market competition.

Precarious welfare states

Feelings of job precarity discussed above are likely to be heightened if the individual has limited options for drawing on alternative sources of non-wage income; in such instances individuals will be located in the intersection between precarious jobs and precarious welfare states (see Figure 1). The welfare state is likely to engender a sense of precarity if individuals feel they would not be provided with adequate financial security in the absence of employment. Welfare states may also be viewed as precarious if individuals do not feel they have the complete certainty of knowing when they will be eligible to draw on state pension income. The UK welfare state is likely to be viewed as precarious in both of these senses.

One of the key roles for welfare states is to reduce, or ‘de-commodify’, individuals’ reliance on the market for survival, enabling individuals to opt out of employment when they perceive this to be in their best interests (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). Inevitably, the extent to which welfare states ever did this has varied, but UK increases in State Pension age significantly increase the extent to which individuals are reliant on the market (and employment) for survival until older ages. Lain (Reference Lain2016) argues that the UK is moving towards what he terms a ‘self-reliance’ model where most individuals now have the theoretical right to continue working past age 65, but rapid State Pension age rises offer little realistic alternative to employment. As recently as the early 2010, women could receive a state pension at age 60, and men at age 65. Since this time projected female State Pension age rises have accelerated and have risen sharply, such that state pension ages for both sexes will be 66 by 2020 and 67 in 2028; after 2028 pension ages will be reviewed at regular intervals and will rise still further. In this climate, individuals in ‘earlier’ older age may have doubts about when they will be able to receive state pension.

It is worth noting that there will be no option to take a reduced pension before State Pension age (Lain, Reference Lain2016: 169). Furthermore, Pension Credit, which provided retirement incomes for men and women from age 60, will no longer be available before State Pension age. These changes place more pressure on individuals to remain in work in older age, particularly given that unemployment and ill health-related benefits are worth half that of the State Pension (Lain, Reference Lain2016).

In this context, the extent to which workers feel a sense of precarity will depend upon their access to non-wage private sources of income. Some individuals will have accrued sufficient salary-related occupational pension income to retire without recourse to State Pension income. This will become less common in future, with the shift from defined benefit to defined contribution pensions, which offer less security and are typically less well funded (Hacker, Reference Hacker2006; Office for National Statistics, 2013). Nevertheless, the extent to which older workers feel a sense of precarity will continue to be influenced by their savings, assets and non-state pensions. In this regard, we expect considerable gender differences, as women are less likely to build up significant pension incomes in their own regard (Ginn, Reference Ginn2003; Ní Léime and Loretto, Reference Ní Léime, Loretto, Ní Léime, Street, Vickerstaff, Krekula and Loretto2017). This presents a particular problem for single women who do not have a partner with a decent pension, highlighting the importance of the household as an influence upon ontological precarity.

Precarious households

For much of the 20th century UK social policy was based on the assumption of a ‘modified male breadwinner model’ (O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Orloff and Shaver1999). The premise of this model was that most people married relatively early, remained married and had their children during the early years of marriage; these children had left home whilst parents were in middle age to set up their own homes. Often the husband worked full-time, while the wife worked part-time to provide a ‘component wage’ to supplement the male ‘full’ wage (Siltanen, Reference Siltanen1994).

While employment patterns of women have continued to be influenced by this modified male breadwinner model, particularly in relation to part-time employment (Office for National Statistics, 2013), households have become much more precarious and uncertain (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2011). In England in 2014–2015, only around 53 per cent of women and 57 per cent of men aged 50–59 were in a marriage and married to their first husband/wife (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Batty, Begum, Demakakos, Oliveira, Head, Hussey, Lassale, Littleford, Matthews, Nazroo, Oldfield, Oskala, Steptoe and Zaninotto2016: 228). Among those aged 55–59, some individuals had inevitably never married (15.1% of men and 7.4% of women). However, particularly in the case of women, being single through divorce was more common (22% of women were in this category), while widowhood among women became common by age 65–69 (12.1%).

Divorce and widowhood is known to increase the likelihood of being in the poorest wealth quintile, but the impact of this is stronger for women than men (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Batty, Begum, Demakakos, Oliveira, Head, Hussey, Lassale, Littleford, Matthews, Nazroo, Oldfield, Oskala, Steptoe and Zaninotto2016: 228); this is likely to be partly because women are less able to amass significant pension income in their own right as a result of marriage and family trajectories (Ginn, Reference Ginn2003). Older divorced women are often highly dependent upon their own resources, as State Pensions from a former partner cannot be shared, and there are no guarantees that divorce settlements will split occupational pensions or provide continued alimony payments after children have grown up (UK Government, 2018). Referring back to Figure 1, we may therefore anticipate that some women in particular are likely to be in the centre of the Venn diagram, experiencing precarity as a result of their precarious employment prospects/content, ‘precarious’ marriage/household trajectories and their limited prospects of obtaining alternative sources of pension/benefit income.

While the above focus is on single people, it is also important to note that households involving couples will face different forms of precariousness. Remarriage may lead to more complex household arrangements in older age and financial pressures to continue working from taking on financial responsibility for young stepchildren (Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff2015). Added to these pressures is the fact that young adults are increasingly financially dependent upon their parents more generally, given lengthened periods of study and increased difficulties establishing careers and households of their own (Office for National Statistics, 2016).

One of the key ways in which disruptions to household structures impact upon individuals is in relation to home-ownership. Lain (Reference Lain2016: 146–149) found that at age 65–69, 8 per cent of individuals in England in 2010 were still paying off their mortgage, and that paying off a mortgage doubled the likelihood of someone working at this age (see also Smeaton and McKay, Reference Smeaton and McKay2003). Those who have experienced some form of marital disruption are most likely to have outstanding mortgage debts in older age (for a discussion, see Lain, Reference Lain2016). More generally, with the rise of interest-only mortgages there has been a sharp increase in individuals reaching ‘retirement age’ with outstanding mortgage debt since 2010 (The Guardian, 2017b). The need to pay off this mortgage debt before retiring is likely to intensify feelings of precarity further.

While the likelihood of owning your own home outright increases with age, it is important to note home-ownership is far from universal. Just under half of those aged 55–64 in 2015–2016 owned their own home outright (45.4%) in England, with just over a quarter still paying off the mortgage (26.5%) and a quarter renting (28.1%) (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2017). The proportion of older people renting privately has risen since 2007, and by some estimates is likely to reach a third by 2040 (Centre for Ageing Better, 2018). A projected decline in home-ownership may therefore intensify feelings of precarity among older people in future.

In summary, our assumptions from the literature review are that in order to understand precarity as a lived experience we need to bring together the domains of precarious jobs, welfare states and households (Figure 1), and consider the intersections between them. To do this we draw upon empirical data from qualitative case study research in two different employment organisations.

Methods

The material discussed here is part of a larger study examining how the policies encouraging extended working lives and changes in the transitions from work to retirement are managed within five contrasting organisations. A case study methodology was used, following Marshall (Reference Marshall1999: 380), as a means to create a ‘comprehensive description of the setting’. A variety of data-collection methods were adopted, including: face-to-face interviews, focus groups and documentary evidence. We aimed to capture views and experiences of a range of stakeholders, including employees aged 50+, line managers, human resources (HR) and occupational health managers.

In this paper we focus on qualitative interviews with older workers aged 50+ in two of the case studies: ‘Local Government’ and ‘Hospitality’. We found examples of older worker precarity in each of the five case studies. However, the organisations examined here were selected because their individual circumstances heightened the sense of precarity felt by older workers, despite having very different workforces. In Local Government, older workers were mainly in ‘white-collar’ jobs and experienced a sense of ontological precarity as a result of cuts in government funding, which led to a 40 per cent drop in the workforce over the period 2010–2016 (equivalent to 4,000 full-time equivalent posts). This was achieved through successive voluntary severance (VS) schemes, with financial incentives dependent on job tenure. The schemes were open in terms of who could apply, but management chose between applicants based on skill needs. Fear of later job loss encouraged people to apply, but a lack of clarity over who would be accepted caused further anxiety. Alongside job cuts, significant organisational restructuring and job redesign occurred as a result of radical changes to the delivery of services. As a case, Local Government represents an apparently classic example of precarity in terms of job insecurity.

The second case, Hospitality, is a catering and cleaning business unit of a large educational establishment. Here workers were predominatly in ‘blue-collar’ jobs and precarity was not (ironically, given the sector) related to job security itself but rather to the capacity of individuals to continue doing the work. The workforce were engaged in hard manual labour and most had worked in this or a similar sector for most of their working lives. They did not typically have significant occupational pensions that would provide a financial cushion in retirement. The workforce displayed the typical range of health issues for a group of manual workers over 50: arthritis, especially knees and hands; diabetes; general aches and pains; and diminished ability to bounce back after long shifts.

We draw on individual interviews conducted in 2015 with 59 employees aged 50+, 37 in Local Government and 22 in Hospitality. The sample group comprised men and women in blue-collar, white-collar and managerial positions (see Table 1). Semi-structured interviews examined the factors influencing decisions about retirement timing, attitudes to extended working life policies, financial circumstances and the management/treatment of older people in the workplace.

Table 1. Demographic profile of the interviewees

Interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. Data storage, coding and analysis were supported by the use of NVivo 10. Team members collaborated to develop a data coding framework, based upon both the interview topic guide and emergent themes derived from preliminary reading of interview transcripts. All interviews were coded in NVivo using this framework, which allowed for a rigorous and theoretically underpinned approach to data analysis.

Findings

Precarious jobs

The nature of job precarity differs to some degree between the case studies. In Local Government there was a fear that individuals would lose their jobs due to job cuts. Such concerns were not present in the case of Hospitality. However, in both cases there was a sense of precarity related to the fact that jobs were becoming unsustainable due to work intensification and, in the case of Local Government, restructuring. We look at fears about job loss in Local Government first, and then examine work intensification in both organisations.

Fear of job loss in Local Government

The majority of the Local Government employees interviewed for this study had experienced the consequences of restructuring. Jobs had been reorganised, resulting in fewer available posts; as a result, many of the interviewees had been required to reapply for their own jobs. Others had been redeployed elsewhere within Local Government, sometimes to a lower-grade job on protected pay for a three-year period. Many interviewees had been invited to apply for VS and were in the process of considering this at the time of interview. Thus, job-related insecurity and associated anxiety was widespread amongst the interviewees in the Local Government sample group. Individuals expressed fears as to whether they would continue to have a job in the next wave of restructuring:

I'm a little bit scared at the moment because, you know, they've got to cut 600 staff so I'm thinking, okay, you've got to be sort of on your guard, there's not a good atmosphere. (LGF18, female, aged 57, divorced, poor health, white collar)

I've always felt insecure since they've had all the budget cuts, things about my job. I never –, I used to be more carefree about things but I think the last three years I've been a bit more worried about it. (LGF06, female, aged 58, married, good health, white collar)

Redeployment to another job was commonly mentioned as a possible outcome for many workers. Thus for some interviewees, the anxiety stemming from job insecurity was associated with a loss of control and uncertainty over the future of their working lives; a further aspect of restructuring which reinforced a sense of ontological precarity:

You're not naturally in control of your own destiny anyway, in terms of they might decide that this job, you know, we can't afford to do it anymore and something else will have to happen or we've got too many people doing it, so we'll move you again. (LGM10, male, aged 55, married, good health, white collar)

This sense of uncertainty about job roles was underpinned by a concern that jobs they were allocated might not be appropriate or sustainable for them in the longer term. In this context, a minority of interviewees viewed VS schemes as a means through which they could attempt to regain control of their working lives, even if this meant that they ended up retiring from their jobs sooner than they had originally intended. Drastic changes to the organisational context had prompted a few employees to choose to leave their jobs rather than be forced into a new role that they did not actually wish to undertake, or did not view as suitable for them:

At least if I take this option I know exactly where I stand. I have the facts and figures and I know that I am not being transferred to a job that I really don't want to do. (LGM29, male, aged 56, co-habiting, good health, blue collar)

For Local Government employees, work-related precarity was compounded by their perceptions of ageism within the organisation. Although HR managers within Local Government maintained that applications for VS were assessed in relation to skill needs, there were some employees who commented that when posts were cut, it was older workers who had tended to lose out on jobs when competing with younger colleagues:

I mean there was no way you could prove it obviously, but a lot of people who ended up not with a job, or not with a job they originally wanted, were the older people. (LGF02, female, aged 56, married, good health, white collar)

Women were more likely than men to express such concerns, and their accounts suggest that they perceived there to be a gendered dimension to ageist attitudes:

I think it's to my advantage to not tell people my age anyway, and people probably do think I'm much younger anyway, but I think people will think, oh she'll start slowing down and she won't be able to do her job, if they knew my age … I think I've still got a lot to give. (LGF11, female, aged 61, never married, good health, white collar)

Almost all of the Local Government interviewees were long-standing employees within the organisation, and they expressed doubts about their ability to secure employment within the wider labour market, as illustrated by the representative quotation below:

I'm mindful that, you know, reading the press, people who are over 55 you don't always get a job … So that's a bit worrying. (LGF36, female, aged 55, divorced, health status unknown, managerial)

They therefore perceived the labour market to be virtually closed to over-50s, which increased their sense of ontological precarity.

Work intensification in Local Government and Hospitality

Work intensification was an issue reported by many interviewees within both case study groups. This was a source of a precarity for older workers because it decreased their confidence that continuing to work was sustainable. In Local Government the consequence of work intensification was viewed more in relation to the psychological rather than the physical toll this placed on individuals, reflecting the white-collar nature of much of this work:

I just don't like work anymore. I dislike work, it's too much pressure. It's mainly I guess because of the way we've been restructured, we've lost staff through voluntary early retirement, through voluntary early severance. A number of staff have left, they've never been replaced, but the workload continues to increase. (LGM20, male, aged 55, married, white collar)

Given the physically arduous nature of much work, Hospitality employees focused on the increasing physical pressures, alongside the psychological pressures related to meeting deadlines, as illustrated in the following quote:

Some of us that have been here 12 years or maybe longer, we've seen changes and the job sort of gets more and more demanding and physical, and you think, I can't see me doing this is in another couple of years or five years. (HF11, female, aged 50, divorced, fair health, managerial)

As this section on precarious jobs has shown, employees in both case studies felt that they lacked choice and control over their working lives and doubted their ability to stay working over the longer term.

Precarious welfare states

Financial insecurity was a key theme within the data, as a dimension of household precarity which strongly influenced employees’ choices concerning extending working life. Here we present data which demonstrate the implications for older workers of an increasingly precarious welfare state (in the form of reduced access to the State Pension), and we highlight the ways in which the precarious welfare state intersected with precarious employment and precarious health (a facet of precarious households) in the lives of the case study employees.

In both case studies there were individuals who reported that, although they would like to retire before State Pension age, they could not afford to do so as they had no alternative sources of income. In this context, the rise in State Pension age was perceived by some employees (particularly women) as an unfair ‘shifting of the goalposts’, which had reduced individuals’ degree of choice and control over the timing of retirement. The following comment was typical:

I've got to work till I'm 66 to get my State Pension even though I'm in the [organisation] pension. If I was to take early retirement, I couldn't afford it. I couldn't afford to live. (LGF28, female, aged 58, divorced, good health, white collar)

Comparison of employees in the two case studies reveals that, overall, Local Government employees had accrued higher occupational pensions and savings over the lifecourse, compared to workers in Hospitality, who were generally in lower-paid occupations. For some workers in Hospitality, even retiring at State Pension age was perceived to be unattainable, as they did not think that they would be able to manage financially on their State Pension income. The following comment is indicative of these low-paid workers’ concerns about their income in retirement:

It does worry me about what am I going to be living on, what the State Pension's going to be ’cause they keep reducing and reducing all the welfare. (HF16, female, aged 53, divorced, good health, blue collar)

The significance of a precarious welfare state is most vividly illustrated through the accounts of several blue-collar workers in Hospitality who reported current poor health and/or who anticipated worsening health in the foreseeable future. Uncertainty about future health status, of self and others, had become an increasing concern for these employees; this may be thought of as ‘precarious health’, and it emerged as a key theme within the Hospitality employee data. These workers generally felt that they had little financial option but to continue working until State Pension age, if not longer, but they doubted whether their health would enable this. This combination of financial and health pressures caused considerable anxiety amongst interviewees, who described the precarity of their circumstances in graphic terms, as in the quotation below from a female blue-collar employee:

I'd like to go pretty soon, actually, but I can't afford it. It basically comes down to money, really. I mean, you're not going to get much in the State Pension and, you know, they keep putting the age up and quite frankly, I can't see me physically and mentally being able to do this job, you know, at those ages they're talking about. I think it's 66 for me … I mean, that's ridiculous. I really cannot see me being able to cope with all the workloads, not in this job. (HF24, female, aged 60, co-habiting, fair health, blue collar)

This employee's comments were echoed by another female worker, who described how her current health problems already made it difficult for her to do her job:

I'm not going to lie to you, yeah, I am finding it very, very tough and some days I think oh, God, I don't know how I'm going to carry on doing this. ’Cause I've had my letter from the pension people, ‘You can't retire till you're 67’ (laughs). I probably won't even here by the time I'm 67 … it's tough because I know that I can't pay my bills without going to work … I know I've got to carry on working till the day I drop, basically, and there's nothing I can do about it. (HF28, female, aged 57, married, poor health, blue collar)

Arguably, access to a decent State Pension at a younger age would have allowed these workers a greater degree of choice and control over whether or not to continue working after the onset of chronic health problems. This is particularly the case when Employment Support Allowance for those unable to work due to ill health was only worth £73.10 a week in 2017, half that of the already low UK State Pension.Footnote 2 Pension policies designed to extend working life actually therefore exposed workers whose circumstances were already precarious (due to their poor health and low-paid employment), to increased precarity. In sum, these data highlight not only the interactions between precarity in health and household finances, but also the significance of a precarious welfare state in reinforcing, rather than protecting against, the precarious position of low-paid older workers in poor health.

Precarious households

The domestic or household context was important in terms of mediating the impact of precarious work on individuals’ own sense of ontological precarity. Household circumstances could reinforce interviewees’ sense of precarity, or act as a kind of buffer against it. In both case studies, those employees who were married, owned their own homes outright, lived in dual-earner households, who had been able to save money into occupational or private pension schemes throughout the course of their lives and who no longer had dependent children, were least likely to report that work-related precarity had undermined their sense of ontological security. On the other hand, being divorced or single, living in a low-income household, having a mortgage to pay off and having dependent children still living at home, were all associated with a heightened sense of ontological precarity in the face of precarious working conditions and a precarious welfare state.

In the case of Local Government, whilst work had become more precarious for almost all employees, there was a sub-set of interviewees who had sufficient financial resources to regard the prospect of VS as an opportunity to make choices about the end of their working lives that would not otherwise have been available to them. These interviewees were generally male white-collar workers who had been employed by Local Government for over 25 years. They had built up generous pension entitlements over the course of their working lives, were owner-occupiers who either owned their homes outright or were close to paying off their mortgages, and were thus relatively financially secure. For these men, VS was an attractive proposition, as illustrated by the following quotation:

I think that it would be a good opportunity for me to start doing something I'd rather, you know, I'd enjoy more and get a bit more from it. (LGM33, male, aged 57, married, fair health, white collar)

By contrast, for other employees within Local Government VS was not feasible, due to their overall household financial circumstances. For example, one female employee was the main wage earner in her household. Her husband only worked part-time, and she was ten years away from State Pension age:

I would say with having another ten years to go to draw my State Pension, it's not feasible really because my husband's only got a part-time job as well and I'm the main bill-payer, whereas if he was in a different situation I might consider it. (LGF21, female, aged 55, married, fair health, white collar)

Housing tenure emerged as a key facet of household context that mediated work-related precarity. Across both case studies, those interviewees in owner-occupied housing who had paid off their mortgages made reference to the sense of financial security that they derived from owning their homes outright. Home-ownership acted as a buffer against the perceived financial risks associated with work-related precarity. For example, in the quotation below, a female employee in Local Government, whose job was precarious due to the restructuring, explained why this work-related precarity did not pose much of a threat to her sense of security:

I haven't got as much to lose, I mean, I don't have a mortgage to pay and my kids, I'm nearly financially stable, so I don't have the pressure that younger people have. (LGF02, female, aged 56, married, good health, white collar)

In Hospitality, home-ownership was viewed by several interviewees as a source of wealth that could be released through downsizing, which could buffer them from the loss of income in retirement arising from minimal pension savings:

We've talked about downsizing in the next two years … releasing a little bit of capital out of our house, so that's another option. (HF08, female, aged 56, married, good health, managerial)

The importance of the household with respect to the financial position of women is illustrated by the relatively small number of low-paid women in Hospitality who felt financially secure because they owned their own home, and their husbands had accrued some pension savings. One such respondent reported:

We've got no mortgage anyway, so my husband's good with, you know, he's got a good pension and stuff. (HF17, female, aged 60, married, poor health, blue collar)

By contrast, those interviewees who were still paying a mortgage or who lived in rented accommodation expressed much more concern about their financial circumstances when faced with precarious work. For these individuals, choice and control about the timing of retirement were closely bound up with the need to pay for housing, and thus the potential negative financial consequences of precarious work were much more threatening. Here again, the significance of the relationship between marital status and housing tenure becomes apparent. Across both case studies, divorced women were less likely to own their homes outright than married male and female interviewees living in dual-earner households. For many of these women, who had taken out new mortgages in their forties or fifties, the continuing need to pay their mortgages had led to them revising the age at which they anticipated they would retire. As one female employee in Local Government remarked:

To be honest, because I have got a mortgage now, I've never even contemplated or thought about retirement … when you're one person it's got to be everything, hasn't it, because you've got to financially make sure you're fine yourself. You've got no-one else to rely on. (LGF27, female, aged 56, divorced, good health, white collar)

Similarly, a divorced female employee in Hospitality wished to retire but could not afford to do so. Her description of her situation highlights the links between her divorced status, her income, her housing tenure and the ways in which these elements of her personal circumstances constrained her degree of choice and control over the timing of retirement:

Sometimes I think I'll just go at the financial year end, and then I think there's no way I can. Financially I can't do it, I live in rented accommodation, erm due to my divorce going badly wrong, but that's how it is, so we don't own anywhere. I keep doing sums and looking at figures and thinking I want to do things and if I retire I won't be able to do anything. (HF15, female, aged 64, divorced, good health, blue collar)

This gendered disadvantage in housing tenure for divorced women was reinforced by the loss of access to their husband's pension savings, exposing them to financial precarity in later life, as this employee from Hospitality explained:

If I'd still been married, I would have been quite happy to retire at 60, because financially we would have been fine, because the pension that my husband was paying into would have covered both of us. On his leaving, I got left with nothing, so I've had to work and start paying into a pension here. So financially I'm not in a position to retire. Even when I get to 67, I still don't know how financially I would be able to manage. So I would say I would work as long as I could possibly work. (HF12, female, aged 61, divorced, fair health, white collar)

Gendered financial precarity in relation to pension savings was not solely the preserve of divorced women. In general, women reported much lower occupational pension savings than men. This was partly due to periods of child care-related absences from the labour market, meaning that they had lost out on years of pension contributions. Women were also more likely to have been employed in part-time jobs over the course of their lives, and in some cases this meant that they had not been eligible to contribute to an occupational pension. In the case of many Hospitality workers, low earnings also restricted the amount that they had been able to afford to save into a pension. However, married women were afforded some protection from financial precarity in retirement by their husbands’ pension entitlements.

The impact of precarious work on ontological precarity can therefore be reinforced or buffered by household circumstances, namely housing tenure, household composition, marital status and overall household financial resources. It is also clear that household-related precarity is gendered in ways that tend to disadvantage divorced women. Overall, therefore, this analysis illustrates the importance of considering precarious household dynamics when assessing precarity amongst older workers.

Conclusion

Contemporary policy debates view extended working lives through the lens of individual choice and control (see e.g. Altmann, Reference Altmann2015; Cridland, Reference Cridland2016). The influential counter-arguments made by Standing (Reference Standing2011) are welcome in the sense that they challenge this assumption. Standing (Reference Standing2011) highlights the fact that some older workers are forced to take on precarious jobs in older age due to dwindling pension incomes. However, the position of older people in the ‘precariat’ has been under-theorised, with older people being presented as rather passive and in some cases content to be in these jobs. Likewise, arguably Standing (Reference Standing2011) does not take into account people in long-term jobs experiencing ‘ontological precarity’.

In this paper, we have presented a theoretical framework for understanding precarity in older age as a lived experience in the UK, which is influenced by the intersection between precarious jobs, precarious welfare states and precarious households. This model was illustrated by drawing on qualitative research on older workers in two case study settings: local government and hospitality. In both organisations older workers experienced a sense of ontological precarity because they were worried about the long-term sustainability of their jobs and saw few alternative sources of retirement income. In Local Government older workers felt a sense of precarity as a result of fears about losing their jobs in the context of severe budget cuts. This was not an issue in Hospitality, but in both case study settings older workers worried that their jobs were not sustainable in the long term because of work intensification (for a wider discussion, see Green, Reference Green2006). Work intensification resulted in psychological pressures in Local Government, and increased physical demands in Hospitality.

A significant proportion of interviewees in Hospitality had health problems, or feared the onset of health problems, given the nature of their work. However, in the domain of precarious welfare states, individuals were well aware that they would have to wait much longer for the State Pension; disability benefits (in the form of Employment and Support Allowance) were not even on the radar of these workers as an option, which is not surprising given the very low level at which it is provided. Fears about the sustainability of their jobs in the context of very strong financial pressures to continue working resulted in anxiety amongst workers.

In this context, household circumstances either reinforced interviewees’ sense of precarity, or acted as a buffer against it. For example, workers in Local Government were generally better off financially than their counterparts in Hospitality. However, some divorced women in Local Government felt greater financial anxieties than lower-paid married women in Hospitality whose husbands had pensions. Indeed, divorced women in particular were disadvantaged in multiple ways, because they needed to be financially self-reliant, but had unsustainable jobs and limited alternative sources of income. This illustrates the importance of considering the interaction between precarious jobs, precarious welfare states and precarious households.

We have demonstrated that the ontological experience of precarity cannot be understood solely in relation to the domain of paid employment; the scope of enquiry must extend to other domains of individuals’ lives that overlap with work. Precarity in any one of the three dimensions of work, household and welfare state can potentially undermine individuals’ ability to extend their working lives but it is the interaction between domains as seen here that critically underscores the opportunities for, or threat of, working longer. Thus, ontological precarity may or may not be directly related to precarious work conditions per se: an older worker may have a relatively secure job, but precarity in another area of their life may undermine their sense of ontological security and lead to a loss of control or choice over whether or not to extend their working life. Whilst it has been common for researchers to hypothesise the impacts of labour market and welfare state structure and change on older workers’ employment trajectories, there has been much less interest or consideration of family or household structure and change (Moen, Reference Moen2011; Loretto and Vickerstaff, Reference Loretto and Vickerstaff2013; Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff2015).

Our in-depth analysis demonstrates the crucial role of qualitative research in uncovering the nature and meaning of complex relationships between precarious work, a precarious welfare state and precarious households. In our study, the ways in which older workers experienced and made sense of their employment situations were interwoven with a host of other elements of their individual biographies. Interviewees’ accounts of their lives offer an insight into how the interactions between these overlapping domains may either engender or assuage a sense of ontological precarity, with implications for extending working life. Our analysis also reinforces the need to understand later working lives through a gendered lens, as experiences throughout the lifecourse often position women and men in very different situations in later life (see also Vickerstaff et al., Reference Vickerstaff, Street, Ní, éime, Krekula, Ní Léime, Street, Vickerstaff, Krekula and Loretto2017). Our approach is consistent with those calling for a new research agenda to understand more fully changing patterns of work in later life (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Phillipson2016).

In terms of limitations, this is a relatively small study, based on 59 interviews with older workers. We therefore do not claim that the results are representative of the overall population of older people. However, we would argue that the findings have a more general resonance for older workers beyond these narrow sectors. It is known that job satisfaction, which is allied to precarity, has declined significantly among older workers generally in recent years (White and Smeaton, Reference White and Smeaton2016), and there has been widespread work intensification (Green, Reference Green2006). Analysis by Lain (Reference Lain2016: 98) suggests that around 30 per cent of those working aged 65–74 in England in 2012 were in jobs that could be defined as physically demanding, which raises concerns about the sustainability of many jobs held by older people. Likewise, it is known that older women in particular are heavily concentrated in the wider public sector (Trades Union Congress, 2014: 11), which has been subject to the kinds of cuts and structural changes we saw in Local Government (Wanrooy et al., Reference Wanrooy, Bewley and Bryson2013). Finally, evidence from the USA suggests that jobs in general have become more pressurised and stressful in recent decades (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Mermin and Resseger2011), and there is little reason to believe this is not also the case in the UK (Lain, Reference Lain2016: 98–100). In this context, the challenges facing workers in Local Government and Hospitality are unlikely to be rare amongst older workers more generally.

Taken together with increased financial pressures to continue working, there is therefore a strong argument for estimating that ontological precarity among older people in the UK is fairly widespread; further empirical research is required to verify whether this is indeed the case. In doing so, future work can develop our model quantitatively, to examine further how precarity/security in the different domains of peoples’ lives interact to influence overall ontological precarity (measured using quantitative scales).

Future research could also examine the extent to which this model applies in countries other than the UK. We might expect the UK results to be most closely mirrored in other English-speaking countries, where mandatory retirement ages have been abolished, state pension ages are rising and the welfare state more generally provides only a relatively weak safety net (Lain and Vickerstaff, Reference Lain and Vickerstaff2015). However, policy analysis by Vickerstaff et al. (Reference Vickerstaff, Street, Ní, éime, Krekula, Ní Léime, Street, Vickerstaff, Krekula and Loretto2017) suggests that ontological precarity may not be confined to English-speaking countries. In Australia, Germany, Portugal, Sweden and the UK it is said that there has been an ‘individualisation of risk, retrenchment in public policies and increasing precarity in employment’ (Vickerstaff et al., Reference Vickerstaff, Street, Ní, éime, Krekula, Ní Léime, Street, Vickerstaff, Krekula and Loretto2017: 227).

If, as we argue, a sense of ontological precarity amongst older workers is common, at least in the UK, this cannot be good for the wellbeing of society. We argue that it is necessary to reconsider how policy supports older people in making decisions about work and retirement. This means recognising that, for some people, continuing to work until age 70 is unrealistic, and that state-provided financial support mechanisms are required to enable people to exercise greater control over the timing of the end of their working lives. In the UK context, this involves promoting extended working lives but continuing to allow people to take a state pension at age 65, something that is arguably economically feasible (see Lain, Reference Lain2016: 169–170; also Macnicol, Reference Macnicol2015). Furthermore, there is an urgent need to support employers in renewed approaches to engaging with their older workforce in order to overcome the apparent mismatches between ‘official’ policy rhetoric promoting the mutual desirability of extending working lives and the experienced reality (Loretto et al., Reference Loretto, Airey and Yarrow2017; Wainwright et al., Reference Wainwright, Crawford, Loretto, Phillipson, Robinson, Shepherd, Vickerstaff and Weyman2018). Without such a renewed policy effort, prospects for the wellbeing of us all in older age are precarious.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to those who gave so generously of their time to be interviewed.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number ES/L002949/1). This paper is based on work from COST Action IS1409 Gender and health impacts of policies extending working life in western countries, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Ethical standards

The research design and protocols received full ethical approval from the University of Kent, Faculty of Social Sciences Research Ethics Advisory Group on 3 March 2014.