Judicial power is critical for the rule of law, human rights, and democratization (Baird Reference Baird2001; Gibler and Randazzo Reference Gibler and Randazzo2011; Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2003; Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2003; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2015; Widner Reference Widner2001). An empowered court makes decisions without external political constraint (judicial independence) and induces universal obedience (Cameron Reference Cameron, Burbank and Friedman2002; Hall Reference Hall2010; Staton Reference Staton2010). But because courts lack formal mechanisms to enforce their rulings (the “implementation problem”), they are reliant on the public and elites for their power to be realized (e.g., Carrubba Reference Carrubba2009; Staton Reference Staton2010; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2015). This poses a critical dilemma in regimes around the world: Judicial power ultimately derives from political power. The same courts that are tasked with enforcing constitutional limits on political power are also vulnerable to political constraints by politicians and the public, particularly in new democracies where presidents are dominant and judiciaries are nascent (e.g., Widner and Scher Reference Widner, Scher, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008). Under what conditions do citizens, the focus of our study, support or oppose judicially imposed limits on those in political power, particularly if they support that party in power? For citizens, is support for judicial power dependent on who is in political power?

Conventional wisdom would answer this question in the negative. In strong form, citizens are “guardians of judicial power” (e.g., Carrubba Reference Carrubba2009; Friedman Reference Friedman2009; Stephenson Reference Stephenson2004; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005, Reference Vanberg2015). Citizens are said to value courts’ institutional integrity over partisan political advantage. Support for courts is therefore rooted heavily in positive process-based considerations (e.g., procedural fairness), whereas partisan or ideological considerations—in relation to courts’ outputs—exhibit minimal or non-existent effects (Gibson Reference Gibson2007; Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2003, Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009; Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003b; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2014, Reference Gibson and Nelson2015; Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009; Tyler Reference Tyler2006b; Tyler and Rasinski Reference Tyler and Rasinski1991).

Moreover, the threat of electoral punishment from the public prevents politicians from attacking courts (Carrubba Reference Carrubba2009; Stephenson Reference Stephenson2004; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2015). Public ascription of “legitimacy”—rightful authority to render declarative rulings that, inter alia, limit political power (Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2014; Tyler Reference Tyler2006a)—then helps courts solve the implementation problem. In short, judicial power is maintained in large part because of public support and subsequent elite forbearance.

Three substantial gaps exist within these extant explanations. First, with the focus on apolitical explanations, the literature has largely ignored the possibility that citizens may prioritize partisan political advantage over courts’ institutional integrity and autonomy. Yet, because courts can constrain executive power and executives possess mechanisms to influence the judiciary, support for judicial power may turn on partisan alignment with the president, a political foundation prior work has left unexplored. Recent work in the United States has shown that support for high courts can be driven by disagreement with rulings on policy (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013, Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Christenson and Glick Reference Christenson and Glick2015) and partisan grounds (Clark and Kastellec Reference Clark and Kastellec2015; Nicholson and Hansford Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014). However, with their focus on alignment with court outputs, these studies lack a theoretical framework outlining the mechanisms by which citizens may assess judicial power instrumentally and on the basis of partisan attachments to incumbents in political power.Footnote 1

Second, most work focuses on “institutional legitimacy” or “diffuse support”—broad assessments of a high court’s fundamental role in the political system (see Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2014). Those concepts, which contrast with “specific support” (support for policies and decisions), have become underdefined and overinclusive of multiple concepts such as support for court-curbing (attacks on judicial power), trust, and process-based perceptions.Footnote 2 We contend that “support for judicial power” is the most operative and clearly definable outcome of interest, as it fundamentally taps attitudes about courts’ relative status and role in the political system writ large. As we elaborate, the concept of judicial power has implications for, but is distinct from, legitimacy.

Third, while judicial power and related concepts are often treated as monolithic, a crucial distinction exists between vertical power, or power over the public, and horizontal power, or power over the executive and legislative branches. As we demonstrate, this distinction has key implications for understanding how partisan attachments to the president influence public support for judicial power.

In this paper, we develop a conceptual and theoretical framework that seeks to fill these gaps. We advance a theory of partisan alignment which argues that public support for judicial power will be dependent on partisan support of those in power. Importantly, because the theory emphasizes that assessments of partisan (dis)advantage can drive judgments of judicial power, it predicts asymmetric effects on support for vertical versus horizontal power. Presidential co-partisans should be less supportive of judicial power over the president (horizontal) than out-partisans; co-partisans do not want their president constrained by courts, while out-partisans do. But, because citizens anticipate that executive influence may tilt judicial outputs in their favor, co-partisans should be more supportive of judicial power over the people (vertical) than out-partisans. We also discuss how these effects compare to a more approval-based (“specific support”) evaluation like “trust” in courts, where extant perspectives would expect more partisan-based evaluations.

We test the argument with evidence from Africa. Our research design affords a high degree of internal and external validity. First, we focus on Ghana to provide unique causal evidence about the impact of co-partisanship with the president on attitudes about judicial power. Drawing on seven rounds of Afrobarometer data collected from 1999 to 2017, we conduct difference-in-differences analyses testing how citizen attitudes about judicial power change when their preferred party moves in and out of power. To demonstrate generalizability, we conduct a multi-country analysis using all six rounds of Afrobarometer data collected since the late 1990s. The data include over 140,000 respondents across 34 countries.

Overall levels of support for judicial power are high in the African countries we study. Yet, support for judicial power is conditional on partisan alignment with the president. After transitions of power in Ghana, the president’s co-partisans become less supportive of horizontal power over the president, while out-partisans become more supportive of horizontal power. Presidential co-partisans also increase in their trust of courts, while trust among out-partisans declines. In the multi-country analysis, presidential co-partisans are less supportive of horizontal power, more supportive of vertical power, and have more trust in courts. In sum, supporters of the president are more likely to reject horizontal power and more likely to support vertical power. These results highlight a partisan foundation—vis-à-vis the president—to attitudes about judicial power.

Our theory and results make a number of contributions. First, existing research has largely overlooked the role of instrumental partisan motivations in shaping attitudes about judicial power. We provide a theoretical framework for understanding how and why partisan alignment with the president influences support for judicial power. This framework is related to but distinct from “outcome-based” explanations for support for courts, which focus on partisan (dis)agreement with specific rulings or partisan cue-taking generally. Importantly, we show that presidential co-partisanship influences approval-based indicators of support for courts (such as trust) and more diffuse measures of support for courts’ general horizontal and vertical power. The latter findings contrast with the conventional wisdom that emphasizes an apolitical foundation to support for courts. While our aim is not to rule out the potential impact of process-based factors emphasized in the literature, our theory and results highlight a partisan political basis for judicial power that has not been identified or explained. We also contribute by showing how partisan alignments with the president can have asymmetric effects on support for vertical versus horizontal power.

Second, we present novel causal evidence on the impact of presidential co-partisanship on public attitudes toward courts. Our difference-in-differences analyses are unique in this literature, which mainly includes analyses of cross-sectional datasets that make causal inference challenging. The multi-country analysis illustrates generalizability and provides the first systematic inquiry of public support for judicial power across African states. We thus contribute new evidence to the important, but relatively small, comparative literature on public support for judicial power (e.g., Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Staton Reference Staton2010).

Finally, as we elaborate, our results have implications for research on judicial politics in new democracies and beyond. First, our results have implications for understanding how judicial decisions will impact public and elite support for power. By highlighting the role of instrumental partisan considerations, the results illuminate the strategic environment that judges face, a crucial starting point for investigations of judicial behavior and elite behavior toward courts. A partisan political foundation to judicial power can impose limits on judicial power: It sends signals to elites that they can attack courts for uncongenial decisions, and courts may strategically recoil in the face of such attacks for fear that their decisions will not be faithfully implemented. Second, the results have implications for judicial legitimacy. On the one hand, overall levels of support for judicial power suggest that many citizens desire empowered courts. On the other, the partisan foundation to attitudes about judicial power suggests a legitimacy deficit—politicized ascription of power does not imply “rightful authority”—and a challenge for the long-term building of institutional legitimacy.

JUDICIAL POWER: CONCEPTUALIZATION

Our core outcome of interest is citizen support for judicial power. Judicial power is a court’s ability to “cause by its actions the outcome that it prefers” (Staton Reference Staton2010, 9). At the decision-making stage, power is equivalent to judicial independence—courts are not constrained by external political forces (Cameron Reference Cameron, Burbank and Friedman2002; Staton Reference Staton2010). At the implementation stage, judicial power is the ability to induce compliance by political elites and the public (Hall Reference Hall2010; Staton Reference Staton2010). Judicial power is important because: (1) courts lack formal mechanisms to enforce their rulings and are reliant on political elites and the public for the full realization of their power and (2) courts, particularly those in emerging democracies with histories of executive dominance, are vulnerable to varieties of political constraint (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2011; Helmke Reference Helmke2012; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992; Staton Reference Staton2010; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005; VonDoepp Reference VonDoepp2009; VonDoepp and Ellett Reference VonDoepp and Ellett2011; Widner and Scher Reference Widner, Scher, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008).

Although the literature typically treats judicial power and related concepts as monolithic, a centerpiece for our inquiry is the distinction between vertical power and horizontal power. Judicial power ultimately requires widespread support from both the mass public and politicians, including incumbent executives and legislatures. Vertical power is judicial power over the mass public: When courts rule, the people should comply with those rulings. Horizontal power is judicial power over incumbent politicians: When the court makes a ruling that reverses government policy, the government should comply with that ruling.Footnote 3

Judicial Power and Legitimacy

We distinguish judicial power from the concept of institutional legitimacy—rightful authority to render rulings for the polity and a widespread belief that a court is “appropriate, proper, and just” (Tyler Reference Tyler2006a, 375; see also Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2014). Legitimacy is a normative, more aggregate concept that develops when citizens and elites ascribe power to a court as an end in itself. Under this definition, when courts are legitimate, support for their power is not conditional on policy or partisan agreement with court outputs (e.g., Easton Reference Easton1965). It is important to distinguish judicial power (and related concepts such as trust) from legitimacy because conflating them can lead to analyses that suffer from an observational equivalence problem: People may have high support for judicial power because (1) they agree with a court’s rulings or expect partisan advantage or (2) they believe that a court has rightful authority regardless of partisan considerations. But those levels of support are derived from two drastically different processes. The first connotes instrumental support, while the latter connotes legitimacy (see also Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020).

By this logic, legitimacy is difficult to evaluate and is best inferred when tested in the face of political or partisan disagreement (e.g., Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Gibson Reference Gibson, Bornstein and Tomkins2015; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2002). Support for judicial power, which can be directly conceptualized and measured, provides a basis for such a test. If people support judicial power only when they agree with a ruling or foresee partisan political advantage and they withhold power otherwise, that is a detriment to legitimacy. Legitimacy can therefore be evaluated on the basis of whether partisan or policy/ideological considerations influence support for judicial power (see Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020). More recent “revisionist” works in the US case have found such an effect on more diffuse forms of court support, a challenge to conventional wisdom (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013, Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Christenson and Glick Reference Christenson and Glick2015; Clark and Kastellec Reference Clark and Kastellec2015; Nicholson and Hansford Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014; Zilis Reference Zilis2018). But the literature (including some of those studies) has drifted on both conceptualization and measurement surrounding legitimacy, including the aforementioned issue of equating it with diffuse types of court support or conflating concepts like support for court-curbing, procedural fairness versus politicization, and trust into a single “legitimacy” or “diffuse support” measure (see, e.g., Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003a; Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2015).Footnote 4

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Conventional wisdom holds that the public plays a crucial role in the development of judicial power.Footnote 5 As guardians of judicial power, citizens value the institutional integrity and autonomy of judicial institutions, including their role as enforcing constitutional limits against political overreach. Citizens are said to ascribe power on the basis of apolitical process-based factors, for example, fairness, democratic values, and socialization to legal norms and symbols (e.g., Gibson Reference Gibson2007; Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009; Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014; Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009; Tyler Reference Tyler2006b; Tyler and Rasinski Reference Tyler and Rasinski1991). This public support, and the threat of electoral or other punishment from the public, then constrains the behavior of elites who may want to attack courts’ powers (Friedman Reference Friedman2009; Nelson and Uribe-McGuire Reference Nelson and Uribe-McGuire2017; Staton Reference Staton2010; Stephenson Reference Stephenson2004; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005, Reference Vanberg2015). In sum, the conventional narrative would imply that public support for judicial power—either variety—does not depend on partisan political foundations such as alignment with the president.

We advance an alternative to the conventional wisdom. Our partisan alignment theory posits that citizens may also view courts as instrumental vehicles to attain partisan political advantages.Footnote 6 This perspective has connections to revisionist “outcome-based” perspectives (contrasted with the aforementioned process-based perspectives) showing that disagreement with court’s policies—rooted in broad ideological orientation, specific policy/issue preferences, or partisan politics—diminishes judicial power and ultimately legitimacy (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013, Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Christenson and Glick Reference Christenson and Glick2015; Clark and Kastellec Reference Clark and Kastellec2015; Nicholson and Hansford Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014). Our theory is distinct in that it emphasizes the importance of partisan alignment with the incumbent president and it makes different predictions about support for horizontal versus vertical power.

Partisan connections to those in power are important for several interrelated reasons. First, executives generally possess a number of mechanisms to influence and potentially control judiciaries and judicial outcomes. These tools can range from influence to outright domination depending on context. For example, executives have used appointment and removal as a vehicle of political control over judiciaries (Ellett Reference Ellett2013; Gloppen Reference Gloppen2003; VonDoepp and Ellett Reference VonDoepp and Ellett2011). Politicians may also threaten or lodge attacks on judicial power (“court-curbing”), which can constrain judicial decision making (e.g., Clark Reference Clark2011; Helmke Reference Helmke2012; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1992; Staton Reference Staton2010; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005; VonDoepp Reference VonDoepp2009; VonDoepp and Ellett Reference VonDoepp and Ellett2011). Although the extent and nature of executive influence and control can vary across institutional and historical contexts, what is important is that citizens observe that executives possess a variety of formal and informal tools to influence judicial behavior. Second, partisan connections with those in power are important because they can shape the extent to which citizens believe that they will be advantaged (or disadvantaged) by judicial power that constrains the executive.

In Africa, where executive dominance has been a central theme, the most operative political division surrounding public support for judicial power is whether one is a political supporter of the president (“co-partisan”) or an opposition supporter (“out-partisan”). A similar “winners versus losers” division based on presidential association is a potent explanation of attitudes about regimes and legitimacy among citizens in African states (see Kerr and Wahman, Reference Kerr and Wahmanforthcoming; Moehler Reference Moehler2009).

How should co-partisanship with the president (or lack thereof) influence support for judicial power? The partisan alignment theory’s starting point is that citizens desire outcomes that accord with their partisan preferences, and thus, their support for judicial power is driven by partisan considerations vis-à-vis the president. Because assessments of partisan (dis)advantage drive judgments of judicial power, the theory predicts asymmetric effects of presidential co-partisanship on support for vertical and horizontal power.

Regarding support for horizontal power—judicial power that can constrain executive power—the theory predicts that presidential co-partisans should be significantly more likely than out-partisans to reject horizontal judicial power. If support for judicial power is shaped by partisan motivations, supporters of the president will prefer that the executive is not constrained by the courts, while out-partisans will favor powerful courts that can limit the power of the executive. Out-partisans want courts to stand up for constitutionalism and place limits on executive power, but such support is transitory, as these individuals will alter their positions if their favored president wins. For co-partisans, partisan goals outweigh the maintenance of constitutionalism and the rule-of-law checks on political power.

Because executives have mechanisms for shaping courts and influencing their outputs, the theory predicts different effects on support for vertical judicial power over the people. If citizens expect mechanisms of executive influence to shape outcomes, presidential co-partisans should generally expect to support those outputs. In turn, they should be more likely to believe that all people should comply with court rulings. Out-partisans, by contrast, are likely to expect more disagreement with court rulings and therefore become less supportive of vertical power.

In sum, the partisan alignment theory predicts that support for judicial power does indeed depend on who is in power. Because partisan considerations drive support for judicial power, the theory predicts that presidential co-partisans should be less supportive of horizontal judicial constraints on the executive. But, because of mechanisms of executive influence over courts, co-partisans should be more supportive of vertical power. By contrast, out-partisans support horizontal power with the hopes that courts will exhibit checks on the executive. However, they are less likely to ascribe power to the courts for rulings that bind the people. Out-partisans are hopeful in the case of horizontal power but skeptical in the case of vertical power.

• Partisan Alignment Hypothesis: Presidential co-partisans will be: (a) more supportive of courts’ vertical power than out-partisans and (b) less supportive of horizontal power than out-partisans.

An added dynamic element exists for an even richer story underlying this theory. In the event of a change in partisan control of the presidency, we expect that support for judicial power will change. This dynamic story again underscores the instrumental nature of support for judicial power and its basis in maximizing partisan advantage.

• Dynamic Partisan Alignment Hypothesis: After partisan regime change (in the presidency), former co-partisans—now out-partisans—will decrease in support for vertical power and increase in support for horizontal power. Former out-partisans—now co-partisans—will increase in support for vertical power and decrease in support for horizontal power.

Comparison with Indicators of More Specific Support

“Support for judicial power”—our key outcome of focus—represents an evaluation over the preferred role of courts in a political system. In our analysis, we compare this more “diffuse” form of support with more evaluative perceptions—along the lines of “specific support,” or approval of judicial decisions. Evaluative concepts for courts include approval of rulings, confidence, and trust (see Gibson Reference Gibson2011; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003a; Staton Reference Staton2010). We focus on “trust” because it is both backward and forward looking. It can be formed on the basis of how good of a job people believe courts are doing in the present and will do in the future (Staton Reference Staton2010). It can also tap their experience with the courts. We distinguish this evaluative perception of courts from the assessment of “support” for judicial power, and moreover, it provides a key comparison with such support measures. We should expect “specific support” oriented measures, like trust, to be more rooted in partisan political foundations and thus track partisan preferences (e.g., Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003a). The extent to which support for judicial power is rooted in these same factors suggests a more politicized foundation to the broad concept of support for judicial power.

POLITICS AND JUDICIAL POWER IN AFRICA

Most African countries gained independence from colonial rule in the 1960s. Many emerged as democracies, with judicial power enshrined in their constitutions (Prempeh Reference Prempeh2006b). Most countries transitioned to autocratic politics relatively quickly after independence. Through the 1970s and 1980s, the continent was populated by authoritarian governments characterized by a high concentration of power in the executive and a weak rule of law (Prempeh Reference Prempeh2008). In most cases, judiciaries lacked the power to effectively constrain executive power, and courts were subject to executive dominance (Prempeh Reference Prempeh2006b; Widner Reference Widner2001).

Beginning in the 1990s, many autocratic governments in Africa adopted political reforms that included the introduction of multiparty elections. Often, these reforms included legal or constitutional changes aimed at solidifying judicial power (Prempeh Reference Prempeh2006a). As a result, courts in a number of African countries have been increasingly asserting more power. For example, the Supreme Court of Kenya invalidated the results of the country’s 2017 elections, the first time a high court in Africa had ruled against an incumbent in a case challenging the legality of an election result. In Zambia, the courts have been willing to rule against the incumbent in cases challenging parliamentary elections results (Kerr and Wahman, Reference Kerr and Wahmanforthcoming). Despite these assertions of power, courts still face challenges and pressure from elites, and there are recent cases where they have been unwilling or unable to constrain executive power (Prempeh Reference Prempeh1997; VonDoepp Reference VonDoepp2009; VonDoepp and Ellett Reference VonDoepp and Ellett2011; Widner Reference Widner2001).

This context provides a useful ground for our analysis for several reasons. On the one hand, support for democracy and the rule of law tend to be high in most African countries (e.g., Bratton, Mattes, and Gyimah-Boadi Reference Bratton, Mattes and Gyimah-Boadi2005), perhaps in part because of the history of authoritarian rule. These are, therefore, settings where the conventional wisdom could plausibly apply. On the other hand, most African countries are characterized by the conditions in which the mechanisms of our partisan alignment theory could be operative. Despite the political changes of the 1990s, the executive remains dominant in most African countries (Prempeh Reference Prempeh2008; van de Walle, Reference van de Walle2003), which is important for several reasons. First, mechanisms for executives to influence the judiciary persist (VonDoepp Reference VonDoepp2009; VonDoepp and Ellett Reference VonDoepp and Ellett2011), which we argue can have implications for attitudes about vertical power. Second, citizens in many countries perceive that the president plays the most important role in the allocation of valued distributive resources. Presidential co- and out-partisans are thus likely to have different expectations about the extent to which they will be (dis)advantaged by judicial constraints on executive power.

SUPPORT FOR JUDICIAL POWER IN GHANA

We first conduct a set of difference-in-differences analyses using data from the Afrobarometer surveys conducted in Ghana between 1999 and 2017. During this period, Ghana experienced three transitions in the party that controlled the presidency (Table 1). We leverage these transitions to analyze how Ghanaians’ views about the courts change when they have or do not have a co-partisan president.

TABLE 1. Presidential Turnover and the Afrobarometer Surveys in Ghana

Note: NDC = National Democratic Congress; NPP = New Patriotic Party. *President Atta Mills passed away in July 2012. The survey was conducted in May 2012. Vice President John Mahama assumed the presidency and was the NDC candidate in the December 2012 election.

Ghana’s judicial system was established in 1993 when the country adopted a new constitution as part of its transition to democracy.Footnote 7 The Superior Court system includes the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, and the High Court and Regional Tribunals. The Supreme Court’s Chief Justice is appointed by the President and is approved by the parliament. The other Supreme Court Justices are appointed by the President, who acts on the advice of a Judicial Council, and are approved by the parliament. The Supreme Court has constitutional authority to rule on the validity of presidential elections, while the High Court has jurisdiction over challenges to parliamentary elections results.

Increasingly, Ghana’s courts are being called upon to rule in cases related to elections and political conflict between incumbents and opposition parties. Most notably, the then-opposition New Patriotic Party (NPP) challenged the results of the 2012 presidential election, claiming that irregularities and fraud had influenced the outcome. After highly publicized proceedings, the Supreme Court upheld the results of the election in a 5–4 decision.Footnote 8 More recently, the Supreme Court ruled on an election petition ahead of the 2016 elections. The NPP requested that the Electoral Commission audit the electoral register before the elections on the grounds that the outdated register facilitated electoral fraud and irregularities. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the opposition.Footnote 9

Also relevant is the highly publicized corruption scandal that has embroiled Ghana’s judicial system in recent years (Odartey-Wellington, Anas, and Boamah Reference Odartey-Wellington, Anas and Boamah2017). In 2015, the investigative journalist Anas Aremeyaw Anas released a documentary exposing significant corruption in Ghanaian judiciary, including video of judges accepting bribes. This scandal is very likely to have consequences for public attitudes about courts.

The Ghanaian case provides analytical leverage for several reasons. First, since democratization in 1992, Ghana has experienced three transitions of presidential power between the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the NPP. The NDC is the successor party of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), which ruled Ghana’s military government from 1981 until 1992. Jerry Rawlings, who led the coup that brought the PNDC to power and was the head of the PNDC government, won elections in 1992 and 1996. The NPP emerged as the main opposition party in the 1990s. Each party has controlled the presidency twice since 1992.

Second, electoral politics in Ghana has been dominated by the two major parties (Gyimah-Boadi and Debrah Reference Gyimah-Boadi, Debrah and Agyeman-Duah2008; Whitfield Reference Whitfield2009). Partisan alignments have been relatively stable—and have deep historical roots (Whitfield Reference Whitfield2009)—and both parties enjoy substantial and ongoing support from a large proportion of the population.

This stable party system, combined with alternations of power, allows us to estimate the impact of presidential co-partisanship with regression models that include partisan group fixed effects. As detailed below, these fixed effects control for potentially important (and unobserved) differences between partisan groups that could impact their attitudes toward courts.

These features are relatively unique to Ghana, making it an analytically useful case. However, Ghana is comparable to other African countries along a number of dimensions that should be important for generalizability. First, like most African countries, Ghana has a history of authoritarian rule and a relative lack of judicial power. Second, despite the reforms of the 1990s, the presidency remains dominant relative to other branches (Barkan Reference Barkan2009). Mechanisms for the executive to influence the judiciary persist, with potential implications for support for vertical power. Third, political competition and partisan attachments tend to center around distributive politics, rather than ideological or partisan differences (Nathan Reference Nathan2019). Moreover, because power is centralized in the executive, many Ghanaians perceive that the president plays the most central role in the allocation of distributive resources (Ichino and Nathan Reference Ichino and Nathan2013), perceptions with implications for support of horizontal judicial constraints on executive power.

Measuring Attitudes about Courts

Afrobarometer conducts nationally representative surveys across Africa.Footnote 10 Seven have been conducted in Ghana since 1999 (Table 1).Footnote 11 We analyze data from the merged multi-country datasets from Afrobarometer rounds 1–6 (Afrobarometer Data 1999–2016) and from the round 7 survey in Ghana (Afrobarometer Data, 2018). Table 2 provides the question wording and coding for each outcome variable.

TABLE 2. Summary of Variables and Measurement from Afrobarometer Surveys

The main outcome variables capture the distinction between support for horizontal and vertical power. The first, president should obey the courts, measures support for horizontal power. The second, people should abide by court decisions, measures support for vertical power. We create 5-point measures where higher values indicate greater support for judicial power (see Table 2). We rescale these variables to run on a 0–1 scale.Footnote 12

We also measure trust in the courts of law. Trust taps an evaluative perception of the job courts are doing and expectations about how reliably they will carry out their functions. Trust may also capture individual experiences with the court system.Footnote 13 We create a 4-point scale where higher values indicate greater trust in the courts of law. Trust is also recoded to run on a 0–1 scale.

To enhance our reporting of substantive significance, we also create dichotomous outcome measures. For horizontal power and vertical power, we code those who agree or strongly agree with the statements as 1, and all others as 0, including those who are neutral. For trust, we code those who trust courts “a lot” or “somewhat” as 1, and those who trust courts “a little” or “not at all” as 0. In all analyses, we present results on the continuous and the binary measures.

Measuring Partisan Alignment with the President

The main explanatory variable captures respondents’ partisan alignment with the president at the time they are surveyed. Our central measure is dichotomous, close to president’s party, which takes a value of 1 of the respondent reports feeling close to the president’s party, and 0 otherwise. Independents are those who do not feel close to any political party. In Online Appendix D, we also analyze two other measures. President party voter indicates whether the respondent would vote for the president’s party if the election were held tomorrow. President coethnic indicates whether the respondent is a co-ethnic with the president.

Graphical Analysis

We first present the evidence graphically. Figure 1 presents the means of support for horizontal power among NDC and NPP supporters by year (survey round). The figure illustrates a partisan gap in support for horizontal judicial power.Footnote 14 When the NPP is in power, NPP supporters (dark circles) are less likely to believe the president should be bound by courts than are NDC supporters (light triangles). After an NDC president is elected in 2008, the partisan gap flips. For example, in 2005, 82% of NDC supporters support horizontal power, while 74% of NPP supporters do (Panel B). In 2012 following the election of an NDC president in 2008, support for horizontal power among NDC supporters drops to 71%, while it rises to 79% among NPP supporters. Support for horizontal power drops among both co-partisans and out-partisans in 2014, although the drop is more significant for co-partisans. This drop could be driven by popular reactions to the Supreme Court’s role in the 2012 election. Notably, the direction of the partisan gap reverses again after an NPP president is elected in 2016. This reverse trend is especially notable given that the survey was conducted in 2017 after the corruption scandal that shook public confidence in Ghana’s judicial system in 2015–16. This suggests that partisan considerations may be sufficiently strong to outweigh the effect of other important events that might otherwise reduce support court power. These results corroborate the “dynamic partisan alignment hypothesis.”

FIGURE 1. Support for Horizontal Judicial Power Over Time in Ghana

Note: Data from Afrobarometer rounds 3–7. Figure presents means of support for horizontal power among NPP supporters (dark circles) and NDC supporters (light triangles). Vertical dotted lines indicate a change in the presidency.

Figure 2 presents evidence for support for vertical power.Footnote 15 Here, both partisan groups trend very similarly from 2002 to 2012, with attitudes seemingly unaffected by the transition from the NPP to the NDC. A partisan gap does emerge in 2014 (round 6), with the president’s (NDC) supporters expressing greater support for vertical power and out-partisans becoming significantly less supportive of vertical power. This drop among NPP supporters (out-partisans) likely results from their reaction to the Supreme Court’s role in the 2012 elections. NPP partisans do become somewhat more positive about vertical judicial power after an NPP president was elected in 2016. However, on balance the evidence suggests that, in Ghana, attitudes about courts’ vertical power are not conditioned by partisanship.

FIGURE 2. Support for Vertical Judicial Power Over Time in Ghana

Note: Data from Afrobarometer rounds 2–7. Figure presents means of support for vertical power among NPP supporters (dark circles) and NDC supporters (light triangles). Vertical dotted lines indicate a change in the presidency.

Figure 3 presents evidence on trust in courts. The figure illustrates a substantial partisan gap in trust in the courts.Footnote 16 Notably, this partisan gap reverses in direction after all three transitions of presidential power, with the presidents’ co-partisans expressing greater trust in the courts. For example, NPP supporters’ trust in the courts increases substantially after the NDCs Jerry Rawlings—who had led the authoritarian government in the 1980s and had won the first two democratic elections in 1992 and 1996—was replaced by the NPPs John Kufuour: In 1999 (round 1), 50% of NPP supporters trust courts and in 2002 (round 2), 86% of them do (Panel B). By contrast, NDC supporters trust in courts drops from 67% in 1999 (round 1) to 41% in 2002 (round 2). After 2002, NPP supporters trend downward in trust, a trend that accelerates when NDC presidents come to power from 2008 to 2016. There was a sharp decline in NPP supporters’ (out-partisans) trust in courts in 2014 (round 6), which again was the likely result of the Supreme Court’s role in 2012 election. NPP supporters trust in the courts rebounds in 2017 (round 7) following the election of an NPP president in 2016. This sharp increase in support for the courts is particularly notable given that it occurred during the same period as the high profile corruption scandal in the judiciary that began in 2015. As noted above, this indicates that partisan considerations may be sufficiently strong that their impact on trust outweighs even the impact of an event that should reduce overall levels of trust in the courts. Overall, the evidence highlights that Ghanaians’ trust in the courts appears to be impacted by presidential turnovers.

FIGURE 3. Trust in the Courts Over Time in Ghana

Note: Data from Afrobarometer rounds 1–7. Figure presents means of trust in courts among NPP supporters (dark circles) and NDC supporters (light triangles). Vertical dotted lines indicate a change in the presidency.

Difference-in-Differences Regression Analysis

To more formally analyze the impact of co-partisanship with the president, we estimate the following regression model using ordinary least squares.Footnote 17

Y ijt is an outcome measure for individual i from partisan group j (NDC supporter, NPP supporter, or independent) at time t. P ijt is a dummy variable indicating whether individual i of partisan group j is a supporter of the president’s party at time t. λ t are fixed effects for each survey year, to control for time-specific factors that might impact support for courts. P ijt is the “treatment” variable; in each survey round, some respondents are treated while others are not. Because the party of the president changes over time, the partisan group that is “treated” changes across survey rounds. Importantly, the model includes fixed effects for each partisan group, γ j. These fixed effects control for time-invariant differences between members of these different partisan groups. Thus, if NDC voters or NPP voters are different in ways that might be relevant for attitudes about courts, the fixed effects control for these differences. Their inclusion, along with survey-year fixed effects, makes β analogous to the interaction term in a more typical (i.e., two-time period, one intervention) difference-in-differences model (for a similar specification, see Franck and Rainer Reference Franck and Rainer2012). β captures the average impact of changes in a partisan connection to the president (i.e., the average difference-in-differences). The model also includes an interaction between the partisan fixed effects and the year fixed effects (γ j × λ t), which controls for time-specific shocks that may impact different partisan groups in different ways. X ijt is a vector of controls including age, gender, poverty, residence in a rural area, democratic values, and education.

To interpret β as a causal effect, we must invoke several assumptions. The first is an exogeneity assumption (Besley and Case Reference Besley and Case2000). This assumption is plausible, as it is unlikely that changing attitudes about courts among a party’s supporters would impact that party’s likelihood of winning a presidential election (reverse causation appears unlikely). Indeed, Ghanaian presidential elections are often decided by the choices of swing and independent voters (Fridy Reference Fridy2012). In addition, Ghanaian presidential elections have often been decided by extremely close vote margins. The 2008 presidential runoff election was decided by less than one percentage point: about 80,000 votes in an election in which nine million cast ballots.Footnote 18

Second, we must invoke the “parallel trends assumption” (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2008): changes in the presidency are not confounded with partisan group–specific time trends. For example, if NPP and NDC supporters’ attitudes were trending in different directions before transitions of presidential power, this could produce a partisan gap in attitudes for reasons unrelated to the transition. For this assumption, we can examine Figures 1, 2, and 3. The figures make clear that time trends are not likely to be confounded with transitions of power. Indeed, we observe sometimes very sharp changes in trends following transitions of power. That such changes occur with every transition in Figures 1 and 3 further increases our confidence that the results are not being driven by time trends that are confounded with changes in the presidency. This highlights an advantage of studying Ghana; multiple alternations in power make it less likely that group-specific trends unrelated to which party controls the presidency are responsible for the partisan gaps we identify.

Third, while partisan group fixed effects controls for time-invariant variables, we must also consider time-varying factors that could be confounded with presidential transitions. To do so, we include individual-level controls for age, gender, residence in a rural area, democratic values, and education.Footnote 19 These latter two variables fall broadly within process-based approaches and prior shows that they can impact attitudes about courts. Online Appendix C describes the question wordings and construction of these variables. The inclusion of these controls helps us to rule out that NPP and NDC supporters are changing in ways that impact their views about courts. The possibility that NDC and NPP supporters are changing in ways that are confounded with presidential transitions highlights an additional advantage of studying Ghana. Because we are leveraging multiple transitions, our results are unlikely to be driven by unobserved changes among NDC and NPP supporters. For example, if one group were becoming more educated over time, this could help them secure the presidency and influence their attitudes about courts. However, a group’s increased education is very unlikely to explain why attitudes toward the courts reverse trend after their party loses the presidency, and then reverse trend again after their party comes to power again, as we observe in Figures 1 and 3.

Finally, we consider the possibility that judicial and other institutions are changing in ways that are confounded with presidential transitions and impact attitudes about courts. To control for time-specific changes that impact all Ghanaians equally, we include survey-year fixed effects (λ t). Because presidential and opposition party supporters may have different reactions to changes in the judiciary—and time-specific effects generally—we also include interactions between the partisan group fixed effects and the year fixed effects. Thus, the specification controls for the possibility that time-specific shocks and factors, including those related to changing judicial institutions, may have a different impact on different partisan groups.

To further assess the possibility that judicial institutions are changing over time, Figure A.1 in Online Appendix A presents trends over time in Ghana on a series of judicial indicators as measured by VDEM (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Henrik Knutsen, Krusell, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Olin, Paxton, Pemstein, Pernes, Petrarca, Römer, Saxer, Seim, Sigman, Staton, Stepanova and Wilson2017). Across the study time period, Ghana’s judicial institutions have been relatively stable: Judicial independence and executive compliance with the judiciary are relatively high, while executive attacks on the judiciary and politically motivated judicial purges or court packing have been rare, and most indicators remain constant across the study time period.

Regression Results

Table 3 presents the main results, with the coefficients in row 1 providing our estimates of β. Columns 1 and 2 show that co-partisanship with the president significantly reduces support for horizontal judicial power. The effect size in column 1 represents about a 15% decrease from the mean among opposition supporters. Column 2 shows that co-partisans of the president are about 8 percentage points less likely to believe that the president should obey the courts and the law (p = 0.058). The effect sizes in both columns are similar to the effect size of support for democracy, an indicator of democratic values, which is a factor that the existing literature highlights is an important driver of support for court power.

TABLE 3. Partisan Alignment with the President and Public Support for Courts in Ghana, Difference-in-differences Analyses

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Omitted reference category for the education variables are those with No Formal Schooling. Omitted reference category for the partisanship variables are independents and those who support minor parties.

Columns 3 and 4 present the results on vertical power. In contrast to the results from all countries that we present below, co-partisanship with the president in Ghana has no impact on support for vertical judicial power. The partisan divisions on vertical power may be smaller because of survey question wording: The horizontal survey item directly mentions the president, which likely primes partisanship, while the vertical item does not directly reference politics. Columns 5 and 6 show that co-partisanship with the president significantly enhances trust in courts. The effect size in column 5 represents about a 16% increase in trust relative to opposition party supporters and independents. Column 6 shows that co-partisanship with the president increases trust by about 7 percentage points (p = 0.054), about a 14% increase over the mean among opposition supporters.

Table 3 also shows that support for democracy is a significant predictor of support for horizontal and vertical power, as well as trust in the courts. These patterns are consistent with process-based models that emphasize the importance of democratic values in shaping attitudes toward judicial institutions. While more educated Ghanaians are less trusting of courts—perhaps because of increased exposure or knowledge—education does not consistently predict attitudes about power.Footnote 20

Table 4 presents the results from more stringent tests. We restrict each analysis to include only two survey rounds: the one that precedes and the one that follows each presidential transition (Table 1). In narrowing the time window, we can be more confident that contextual and judicial variables are being held constant while the party of the president changes. For example, as Online Appendix A shows, the characteristics of the judiciary in Ghana generally remain relatively constant before and after transitions. Moreover, we can be more confident that the composition of the judiciary remains more constant. For example, although the NPP president who was elected in 2016 has recently appointed new justices to the Supreme Court, the AB survey in 2017 was conducted well before these appointments.

TABLE 4. Partisan Alignment with the President and Public Support for Courts in Ghana Narrowing Analysis to Time Window Around Presidential Transitions

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. All models include partisian and survey-year fixed effects, and all controls from Table 3. Top panel analyzes change from NDC to NPP president in 2016 (surveys in 2014 and 2017). Middle panel analyzes change from NPP president to NDC president in 2008 (surveys in 2008, before the election, and in 2012). Bottom panel analyzes change from NDC president to NPP president in 2000 (surveys in 1999 and 2002). Only the trust measure was included in round 1.

The main results hold when we conduct these more narrowly focused analyses. Panels A and B, which examine the transitions that occurred in 2008 and 2016, show that presidential co-partisanship reduced support for horizontal power.Footnote 21 All three panels present the results on trust and show that presidential co-partisans are substantially more trusting of courts in the periods before and after all three presidential transitions.

Online Appendix J shows that these results are robust to the use of an alternative measure of presidential co-partisanship, president party voter; the inclusion of region fixed effects, which control for additional differences that may exist between the supporters of the major parties;Footnote 22 the inclusion of interactions between the round fixed effects and the individual-level controls, which control for changes over time in the impact of the individual-level variables; and a more conservative approach to clustering standard errors.

Generalizability: Evidence from 34 African Countries

To demonstrate generalizability, we analyze survey data gathered by the Afrobarometer in 34 African countries. We analyze data from rounds 1–6.Footnote 23 Table 5 displays the sample countries and their regime type at the time of the AB surveys, as measured by VDEM (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Henrik Knutsen, Krusell, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Olin, Paxton, Pemstein, Pernes, Petrarca, Römer, Saxer, Seim, Sigman, Staton, Stepanova and Wilson2017). Online Appendix B presents further information about the sample.

TABLE 5. Sample Countries by Regime Type (VDEM) and AB Rounds Surveyed

Note: Table indicates countries in the sample and their VDEM regime category for each AB survey round in which they enter the sample. Countries listed twice in the table changed regime categories across survey rounds.

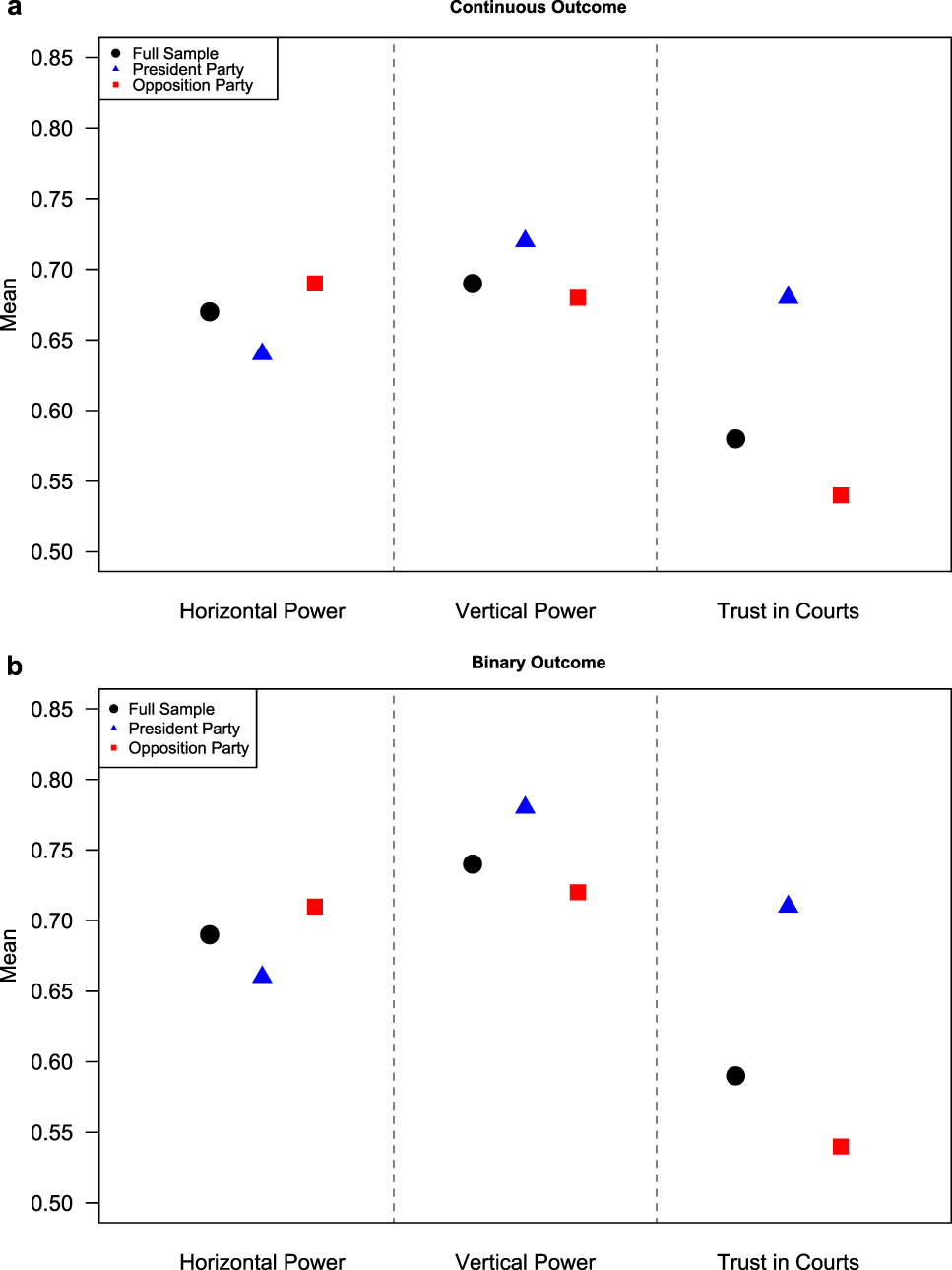

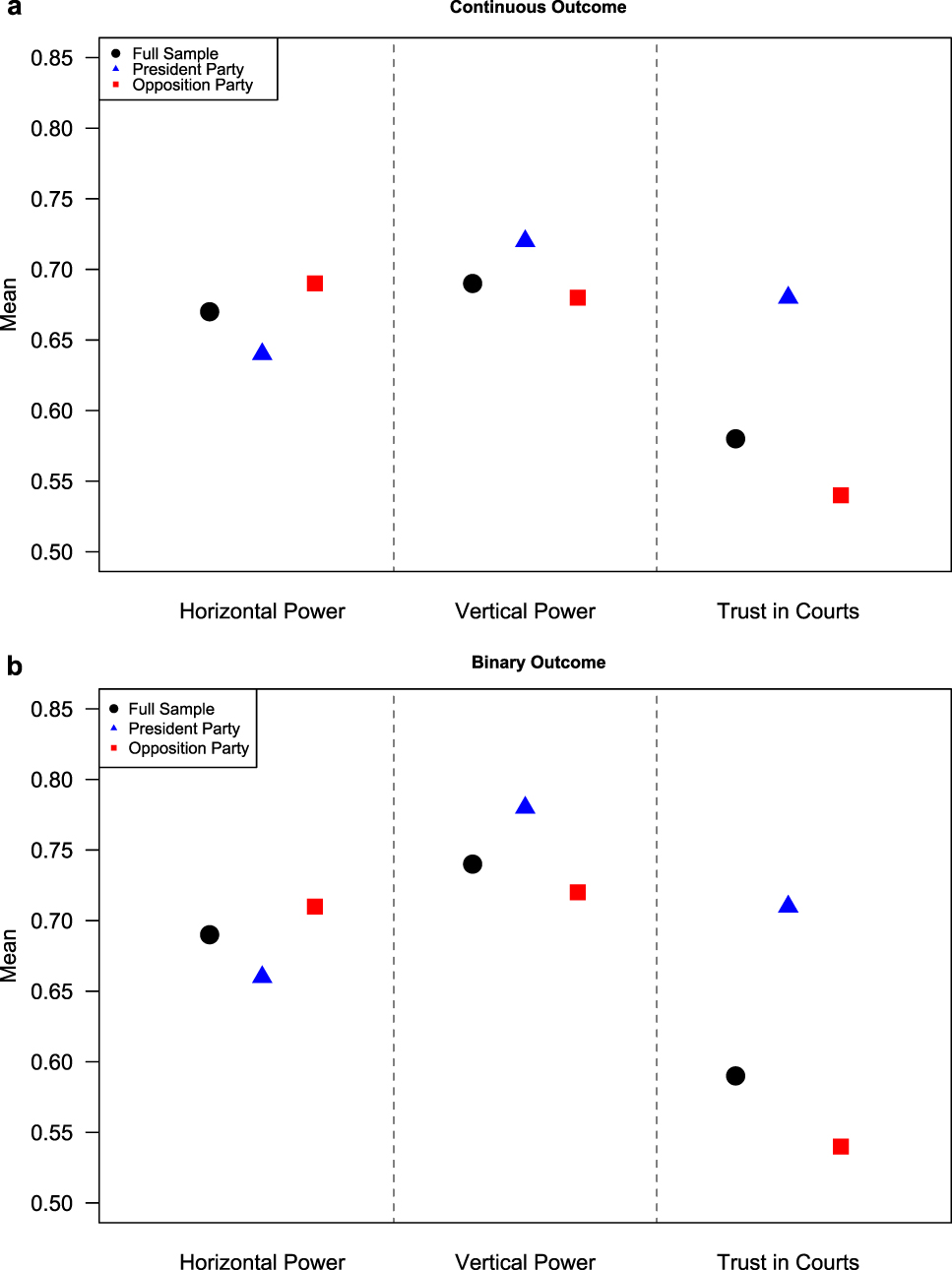

Figure 4 presents the means of the outcome measures for three groups: the full sample (pooling all rounds and countries), president co-partisans, and opposition party supporters. The figure demonstrates that, on average, those in our sample have relatively high support for both horizontal and vertical judicial power, but relatively low trust in courts. About 69% agree or strongly agree that the president should always obey the courts (panel b), while about 25% believe that the president should be able to ignore the courts. Regarding vertical power, about 74% agree or strongly agree that courts have the right to make decisions that the people must abide by, while 18% do not. By contrast, 40% trust the courts just a little or not at all, while about 60% trust the courts somewhat or a lot (note that 29% trust the courts a lot).Footnote 24 Overall, this evidence suggests a gap in what the Africans in our sample desire from the courts and what they perceive they are actually getting; the latter is picked up by the trust measure.

FIGURE 4. Means of Main Dependent Variables in the Full Sample and by Partisan Connection to the President

Note: Figure displays means of each outcome variable. Panel (a) presents the means for the continuous measures, rescaled to run from 0 to 1. Panel (b) presents the binary measures. Both panels present means in the full sample (circles), among president co-partisans (triangles), and among opposition and party supporters (squares).

Figure 4 also provides evidence of partisan gaps in public judgments about courts. Presidential co-partisans are about 4 percentage points less likely to support judicial power over the president, evidence that presidential supporters are more likely to reject horizontal power. Presidential co-partisans are, however, about 4 percentage points more supportive of power to make binding decisions for the people, an indicator of support for vertical power. The gaps in trust are substantially larger. Presidential co-partisans are substantially more trusting of courts than are independents and opposition supporters. They are about 14 percentage points more likely to express trust in the courts of law. Assessments of trust in courts appear to be politicized—via partisan alignment with the president—to a greater extent than support for judicial power.

Table 6 presents regression results. All models include AB survey round and country fixed effects. The survey-round fixed effects control for time-specific factors, while the country fixed effects control for country-specific differences, which include contextual differences, differences in political systems, differences in legal tradition, and colonial legacy. Together, the round and country controls also control for time and country-specific factors that might shape considerations driving attitudes about courts. For example, in countries with a recent history of violence or conflict, citizens might value courts that preserve peace and stability (Long et al. Reference Long, Kanyinga, Ferree and Gibson2013). We also include control variables that could be correlated with partisanship and can impact attitudes about courts. We control for democratic values, level of education, male/female, urban/rural, poverty, and age. We cluster standard errors by country–round–partisan affiliation with the president. We emphasize that a key difference between these models and those in the Ghana analysis is that we are unable to include partisan group fixed effects. Thus, these analyses are less causally identified than the Ghana analysis. However, they have the advantage of allowing us to test whether presidential co-partisanship is associated with attitudes about courts across a larger number of countries and time periods.

TABLE 6. Partisan Alignment with the President and Public Support for Courts

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. All models include survey-round and country fixed effects.

The first two columns show that co-partisanship with the president significantly reduces support for horizontal judicial power. The magnitude of the coefficient in Column 1 represents about a 5% reduction from the mean among opposition party supporters. Column 2 shows that presidential co-partisanship reduces the probability of supporting court power over the president by 5 percentage points, about an 8% reduction. To assess the political importance of these effect sizes, we compare these coefficients to the magnitude of coefficients on other variables that prior literature has deemed important in shaping attitudes toward courts. For example, the effect of co-partisanship with the president is equivalent to moving from having no formal education (the omitted reference category) to secondary or post-secondary education. The effect size is also about the same magnitude of the effect of support for democracy, a variable that has been shown to impact support for courts.

Columns 3 and 4 show that co-partisanship with the president is associated with a significant increase in support for vertical power. The effect size in Column 3 is modest, representing about a 3% increase over the mean among opposition supporters. The effect size is, however, about the same as the effect of democratic values and about the same as the effect of moving from no education to secondary. Consistent with the partisan alignment theory, co-partisans of the president are more likely to support vertical power.

Finally, Columns 5 and 6 show that those who support the president’s party have significantly greater trust in the courts of law. The coefficient in Column 5 represents an almost 20% increase in trust over the mean among opposition supporters. Column 6 shows that the president’s supporters are about 15 percentage points more likely to trust the courts. Trust in courts thus appears to be highly conditional on partisan connections to those in power—and to a greater extent than support for judicial power.Footnote 25

Online Appendix F shows that the results are robust to controlling for perceptions of judicial corruption, a factor that may influence attitudes about courts. We do not include this variable in the main specification because perceptions of judicial corruption are likely endogenous to partisanship.

Online Appendix E replicates the main analyses on each AB Survey round individually. The results are the same in all survey rounds, which suggests that the findings are not particular to specific time periods. Online Appendix H presents country-by-country results. With respect to horizontal power, the co-partisanship coefficient is negative in 25 of the 34 countries, and statistically significant in 16. For vertical power, presidential co-partisanship is positive in 30 countries and statistically significant in 22. For trust, the coefficient on presidential co-partisanship is positive in all countries, and statistically significant in 32. These analyses highlight the generalizability of the findings.

Online Appendix F examines whether the results generalize across regime types and contexts with varying degrees of judicial independence.Footnote 26 The negative effect of presidential co-partisanship on support for horizontal power is biggest in countries that are more democratic and where judicial independence is strong (Figures I.1 and I.2). This suggests that the partisan political stakes regarding executive power are enhanced—and presidential co-partisanship is activated to a greater extent—in contexts where democracy is strong but courts have higher capacity to constrain elected leaders.

By contrast, the effect of co-partisanship on trust in courts is somewhat bigger in less democratic countries and those with less judicial independence (Figures I.5 and I.6)—although we emphasize that the trust results hold in almost all countries. Finally, democracy and judicial independence do not condition the effect of co-partisanship with the president on attitudes about vertical power (Figures I.3 and I.4).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Public support plays an important role in the establishment and maintenance of judicial power. What drives this public support? Is public support for judicial power contingent on who is in political power? We advance a theoretical model in which instrumental partisan considerations play an important role in shaping attitudes about judicial power. The theory highlights why and how partisan alignments with those who control the executive will shape attitudes about different forms of judicial power. Specifically, presidential co-partisanship reduces support for horizontal judicial power (over the president) and increases support vertical power (over the public). We provide evidence consistent with the argument from 34 African states, as well as a focused analysis of Ghana, a context which provides analytical leverage to make causal inferences about the impact of presidential co-partisanship.

This paper makes several contributions. First, in contrast with the conventional wisdom highlighting the importance of apolitical factors in driving public support for judicial power, we theorize and demonstrate that instrumental partisan considerations can also be consequential. Although we cannot rule out that other factors may also be important, we contribute by highlighting the previously unexplored role of partisan alignment with the president in shaping support for judicial power. Second, we contribute new empirical evidence to the literature on public attitudes toward courts outside of the American context. Although it is widely recognized that the public can play an important role in establishing and maintaining judicial power, this is a relatively understudied topic at the citizen level. Importantly, our analysis of Ghana provides causal evidence that is unique in the literature, while the multi-country analysis demonstrates that the findings generalize to a broad range of other African countries.

This paper suggests a number of areas for future research. First, further research could unpack why presidential co-partisanship impacts support for vertical power in the multi-country analysis but not in Ghana. More broadly, research could build upon our multi-country analysis to analyze why co-partisanship influences support for vertical power in some countries but not in others. Second, future studies could utilize different research designs—particularly experimental designs—to examine more deeply the mechanisms implied by the partisan alignment theory. Third, although we provide evidence from a set of African countries, the theoretical framework we develop is general and could be tested in other contexts. Indeed, we would expect the theory to travel to contexts where (1) executives have mechanisms to shape and influence judiciaries and (2) presidential co-partisans (out-partisans) expect to be disadvantaged (advantaged) by judicial efforts to constrain executive power. These conditions characterize many countries around the world, including older democracies such as the United States. Future research could adopt similar research designs to test the impact of partisan alignment with the president in other contexts.Footnote 27

The results also have broader implications for the strategic environment in which courts and other political elites operate, which will be important for future research on judicial politics to take into account. First, although it is beyond the scope of this paper to study the role of judicial decision making in building and maintaining public support for judicial power, the findings lay an important foundation for research on strategic judicial decision making. Indeed, if courts are aware that public support for their power is to some extent driven by instrumental partisan considerations, this is likely to shape and potentially constrain their decision making. In some cases, this could pose an impediment to the realization of robust judicial power, as courts could “play it safe” in an effort to limit partisan backlash or decrease the likelihood of elite attacks on the judiciary. In other instances, courts may be more aggressive if they deem the benefits to outweigh these potential costs. Either way, future research on judicial decision making and strategy should account for the impact of partisan considerations on support for judicial power. Relatedly, the results have implications for elite behavior toward courts. If executives know that support for horizontal judicial power is lower among their supporters, this opens the door for them to attack judicial power or circumvent court rulings.

Finally, our analysis of public support for judicial power has implications for judicial legitimacy. As we have emphasized, legitimacy as “rightful authority” is difficult to observe and is best assessed when support for judicial power comes into conflict with partisan political interests. Such tests occur when courts are called on to decide election disputes, when they make rulings that constrain executive power, or when citizens expect courts to make decisions that conflict with their partisan preferences and interests. Our analysis of presidential co-partisanship and support for judicial power focuses precisely on this latter test. On the one hand, robust levels of support for judicial power among African mass publics suggest that citizens desire empowered and legitimate courts. On the other hand, there is to some extent an instrumental partisan basis to support for judicial power. Ultimately, this suggests a legitimacy deficit and a potential obstacle to the establishment of judicial legitimacy over time. We hope this work will spur future research on the public foundations of judicial power and its connection to the rule of law in new democracies.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000704.

Replication materials can be found on Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HDGUDZ.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.