Introduction

Europe is frequently characterized as a continent that shies away from discussing racism (El-Tayeb Reference El-Tayeb2011; Sierp Reference Sierp2020). Its history of colonialism, slavery, antisemitism, anti-Romanyism, and Nazism establishes a political context in which some countries deem it problematic to use the concepts of “race” and “racism.” Other countries consider themselves impartial observers, considering these issues irrelevant because “race” and “racism” do not exist inside their borders (Keskinen et al. Reference Keskinen, Tuori, Irni and Mulinari2009). In European contexts, race and racism are located within specific temporalities rather than being an everyday phenomenon (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006; Lentin Reference Lentin2008; Salem and Thompson Reference Salem and Thompson2016; Wekker Reference Wekker2016). The concept of race has been removed from mainstream discourse and replaced by references to “ethnicity,” “diversity,” “culture,” “religion,” or “background,” or it is often conflated with migration. This silence about race renders present-day raciality beyond the limits of what can be thought and said (Bilge Reference Bilge2013). It banishes racism from political discourses that celebrate the European values of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, making white Europeanness a norm (Essed et al. Reference Essed, Farquharson, Pillay and White2019; Lentin Reference Lentin2008, 496). However, Europe’s colonial past and racism and discrimination today are inextricably connected to one another: “Colonialism is silently inscribed in the genes of the European integration project since its origins” (Pace and Roccu Reference Pace and Roccu2020, 671; see also Benson and Lewis Reference Benson and Chantelle Lewis2019; Lewicki Reference Lewicki2017; Sierp Reference Sierp2020).

The EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) has provided evidence about the prevalence of racism and discrimination in Europe over the years (see, for instance, 2017; 2018). An active European civil society, antiracist organizations and movements, academics, some politicians, and equality bodies and institutions have, for decades, engaged in a struggle to put racism and antiracism on the political agenda (cf. Essed et al. Reference Essed, Farquharson, Pillay and White2019; Ohene-Nyako Reference Ohene-Nyako2018; Reference Ohene-Nyako2019). The force of the US-based Black Lives Matter movement was felt across Europe, too, and became one catalyst of debating racism in Europe in the 2020s.

The European Union (EU) has made important efforts to combat racism in member states. The Amsterdam Treaty 1997 widened the scope of the EU’s equality policies and enabled the enactment of significant directives, of which the Racial Equality Directive (RED) (2000/43/CE) was a culmination of antiracist activism in the EU (Givens and Evans Case Reference Givens and Case2014, 2). It outlawed discrimination based on race and ethnicity in housing, employment, education and training, and the provision of goods and services (Guiraudon Reference Guiraudon2009). By drawing a distinction between direct and indirect discrimination, it pushed member states to address “more nuanced patterns of racism” (Hermanin, Möschel, and Grigolo Reference Hermanin, Möschel, Grigolo, Möschel, Hermanin and Grigolo2013, 2). Another important landmark was the European Commission’s first Anti-Racism Action Plan for 2020–2025, which committed to taking antiracism further by changing laws so as to combat racial and ethnic discrimination and confront everyday racism in policing, employment, health, education, and housing (European Commission 2020, 25).

The emergence of EU antiracism policies, political struggles around these policies, and their influence on member state policies have been studied in numerous scholarly works (Geddes and Guiraudon Reference Geddes and Guiraudon2004; Givens and Evans Case Reference Givens and Case2014; Guiraudon Reference Guiraudon2009; Hermanin, Möschel, and Grigolo Reference Hermanin, Möschel, Grigolo, Möschel, Hermanin and Grigolo2013; Niessen and Chopin Reference Niessen and Chopin2004). However, we contend that there is a notable gap in the academic literature on racism within EU institutions, as opposed to EU policies. Studies from other contexts suggest that such research on racism within political institutions could usefully focus on patterns of the political representation of racialized minorities (Mügge, van der Pas, and van de Wardt Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019) and also reach beyond numbers to capture how racism, racist practices, and racialization work in contexts like parliaments (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003; Puwar Reference Puwar2004).

Building on these debates, this article scrutinizes racism and normative whiteness in one of the political institutions of the EU: the European Parliament. The European Parliament represents the citizens of the 27 EU member states, and its 705 Members of European Parliament (MEPs) are elected by member state electorates in direct elections every five years. It is frequently regarded as the most egalitarian and democratic of all EU institutions and has consistently pushed other EU institutions to adopt more ambitious antidiscrimination policies (Givens and Evans Case Reference Givens and Case2014, 2–3). For example, it has passed two recent resolutions: one concerning the fundamental rights of people of African descent in Europe (2018/2899[RSP]), requiring concrete action on the part of EU institutions and member states to eradicate racism, and one concerning “the anti-racism protests following the death of George Floyd” (2020/2685[RSP]), which addressed manifestations of structural racism in the United States and Europe, including police brutality.

The lack of political representation of racialized minorities in the European Parliament may come as unexpected in such a context. According to the European Network Against Racism ([ENAR]; 2019), Black people and ethnic minorities constitute around 10% of Europeans. However, the representation of Black and ethnic minority MEPs in the current parliamentary term is 4%. After Brexit in 2020, there were only 24 MEPs of color, amounting to 3% of all MEPs (ENAR 2019). Journalistic media accounts of individual politicians’ experiences of racism, social movement activism such as the #Brusselssowhite campaign, and the few existing scholarly studies about racist language within the parliament (Bartłomiejczyk Reference Bartłomiejczyk2020), along with academic research from other contexts, suggest that racism is an issue for the European Parliament.

One interviewee in our research material said that discussing racism in the European Parliament was “like shouting to a brick wall” (Interview 40). The citation shows how debating and undertaking meaningful actions concerning racism within the Parliament are difficult. Sara Ahmed writes that “banging against the brick wall” describes how diversity work is like “coming up against something that does not move, something solid and tangible” (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 26). The wall materializes “the lack of institutional will to change” (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 26).

The research objective of the article is to analyze how the European Parliament’s whiteness—as one such brick wall—is maintained. The article asks the following questions: how does European whiteness, as a norm, relate to and sustain racism in the European Parliament? How does this affect efforts to tackle racism and advance internal antiracist practices within the institution? We understand whiteness as a positionality and norm that does not recognize racialized relationships as a primary factor in the reproduction of racism (Wekker Reference Wekker2016). White privilege gives invisible assets and unearned advantages that allow white people to be “color blind” and oblivious to racialized discrimination (Bridges Reference Bridges2019b). Moreover, European whiteness is a formative criterion of belonging in Europe today (Essed et al. Reference Essed, Farquharson, Pillay and White2019). More specifically, we consider three strategies that sustain whiteness, as an institutional norm, in the European Parliament: deflection, distancing, and the denial of racialization and racism (Lentin Reference Lentin2015).

We use extensive research material consisting of 140 interviews with MEPs and political staff and parliamentary ethnography collected for a research project. We complement this with an analysis of relevant political documents issued by the parliament and political groups. The empirical analysis is divided into three levels: individual, political group, and parliamentary. This allows us to demonstrate the connections and disconnections between these levels and how whiteness is maintained in the parliament. Racism is not only linked to the actions and attitudes of individuals (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012; Lentin Reference Lentin2016) but, rather, produced through the European Parliament as an institution.

The contributions of the article reach beyond the specific case of the European Parliament. Combining critical race theory and critical whiteness studies with an institutional analysis of parliaments, we develop an analytical framework in which individuals, political parties, and parliaments can be studied together. We operationalize deflection, distancing, and denial in a parliamentary context to explain the maintenance of institutional whiteness while also creating space for understanding antiracist work within parliaments.

Upholding Whiteness as an Institutional Norm: Deflection, Distancing, and Denial of Racism

Our theoretical framework combines insights from critical race theory, critical whiteness studies, and Black Feminism. We understand race and racism as maintained and reproduced through hegemonic power structures (see Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012; Lentin Reference Lentin2016). Race is not biologically real but, rather, socially constructed (Delgado Reference Delgado2018) and has “real, though changing, effects in the world” and on individuals’ lives (Frankenberg Reference Frankenberg1993, 11). Black Feminists show that race, class, gender, and other axes of domination are reciprocally constructed phenomena and that racism intersects with sexism, heteronormativity, capitalism, and Eurocentric coloniality (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991; Hill Collins Reference Hill Collins1990).

Racism remains a systemic feature of our societies, one embedded within institutions that replicate inequalities. Racism is not confined to a few “bad apples” or isolated incidents; rather, it is structural and systemic (cf. Bridges Reference Bridges2019a; Delgado Reference Delgado2018). However, public discourses and policies often link racism to the actions and attitudes of individuals at the expense of its structural and institutional dimensions (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012; Lentin Reference Lentin2016). Structural racism refers to the often subtle and nefarious ways in which laws and public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work to reinforce racial domination (Bridges Reference Bridges2019a).

In this article, we employ the concept of institutional racism to describe how institutional structures, processes, practices, and cultures organize to perpetuate racialized hierarchies within an institution (Salem and Thompson Reference Salem and Thompson2016). When studying racism in political institutions, such as the European Parliament, it is therefore significant to acknowledge not merely the most explicit individual expressions of racism but also the seemingly subtle ways in which institutional practices uphold structures of racialized power and privilege.

European countries frequently display a “peculiar coexistence of, on the one hand, a regime of continent-wide recognized visual markers that construct ‘non-whiteness’ as non-Europeanness with, on the other hand, a discourse of color-blindness that claims not to ‘see’ racialized difference” (El-Tayeb Reference El-Tayeb2011, xxiv). Despite colonial history and its consequences, public discourses in European countries still construct “Europeanness” as “whiteness” and render people of color invisible (Salem and Thompson Reference Salem and Thompson2016; Wekker Reference Wekker2016). Studying race and racism in the European Parliament must therefore interrogate whiteness, which is understood as a mutable social construction that is historical and unfixed (Rastas Reference Rastas2004).

Whiteness represents a location of structural advantage and race privilege—a standpoint from which white people view themselves and society. Whiteness equally refers to a set of normative cultural practices, standards against which all are measured and expected to fit (Frankenberg Reference Frankenberg1993). Whiteness and racism operate in relation to one another. White people willfully enjoy a “transparent” (for them) privilege that allows them to overlook and ignore racism (cf. Eddo-Lodge Reference Eddo-Lodge2018). This white privilege is a benefit consisting of “racial advantage” inflicted on people of color (Bridges Reference Bridges2019b, 456). On the one hand, a primary feature of whiteness both as a standpoint and as a norm is that it does not recognize the existence of colonial histories and racialized relationships and that such relationships also determine white people’s lives (Wekker Reference Wekker2016). On the other hand, this “white innocence” (Wekker Reference Wekker2016)—not knowing and not wanting to know about the work that race does and disavowing privilege—reproduces racialized hierarchies in societies and institutions. Even though white privilege stems from white supremacy, different white people have different levels of access to this privilege (cf. Bridges Reference Bridges2019b), and notably, we are analyzing a predominantly white institution composed of European political elites.

We use concepts of normative whiteness (Bridges Reference Bridges2019a; Delgado Reference Delgado2018) and institutional whiteness (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012) to engage with whiteness and its relationship to racism in the European Parliament. The concept of normative institutional whiteness allows us to explore racialized power structures in the parliament. Our approach relies on understanding normative whiteness in the parliament as configured around practices that normalize “white experience” and bodies that can (unconsciously) contribute to outcomes that are discriminatory and disadvantageous to racialized minorities. Color-blind practices, which allegedly represent everyone, legitimize and reproduce institutional norms that, in fact, undermine and marginalize racialized experiences (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 37–8). Racism and its nonrecognition also reinforce the normative whiteness of an institution.

Alana Lentin (Reference Lentin2016) distinguishes among “the three D’s of post-racial racism management” to show how race and racism are strategically trivialized and antiracist activities are delegitimized. First, deflection occurs by shifting foci, such as emphasizing the positive vocabulary of diversity rather than the language of race and racism (Lentin Reference Lentin2016, 44). Deflection also manifests when critiques of racism are perceived as defamation against the institution. As a result, debates tend to focus on accusations of racism instead of the acts and structures that caused these accusations (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 150–1). Second, distancing presents racist acts as abnormal, deviant behavior on the part of individuals. Racists are set apart from the rest of society or from routine racism. For instance, racism is often attached to the far right or extremism (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006). In institutional contexts, racism is often projected onto a figure “who is ‘not us’ and does not represent a cultural or institutional norm” (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 150). Perceiving racism as exceptional or individualizing it allows structural and institutional forms of racism to recede from view. Also, locating racism in a remote past or another country represents a form of distancing (Lentin Reference Lentin2008; Wekker Reference Wekker2016). Third, racist acts are frequently accompanied by the denial of their racist nature, and assertions regarding “not racism” accompany many structurally white discussions of racism (Lentin Reference Lentin2018; van Dijk Reference van Dijk1992). Racism can also be denied through positive celebrations of the essentially antiracist characteristics of national cultures or institutions.

Deflection, distancing, and denial can occur at various levels: in interpersonal interactions, in practices and discourses of specific institutions, and at societal level—for example, in public policies and media discourses (cf. van Dijk Reference van Dijk1992). These three intertwined practices may represent intentional attempts to silence racism and uphold white privilege or be subtly embedded in established ways of thinking and acting. In such a context, fighting for racial justice means exploring and exposing the mechanisms of racialized subordination, such as normative institutional whiteness. To dismantle and fight against racialized hierarchies, we must examine normative whiteness and its privilege. Critical race studies scholars have shown that this goes beyond discussions of “inclusion” and “diversity.” Confronting normative whiteness is a necessary step in antiracist resistance.

Importantly, some forms of antiracism may participate in trivializing race and racism, for instance, through focusing on extreme events rather than on structural and institutional racism (Lentin Reference Lentin2016, 44). Ahmed’s (Reference Ahmed2012) claim that institutional diversity work may reproduce the institutional whiteness it seeks to overcome is particularly relevant for our study. Building on Puwar (Reference Puwar2004), she argues that setting the inclusion of “people who look different” as a goal confirms whiteness as the norm, without questioning it (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 33). Diversity is often turned into simply “generating the ‘right image’ and correcting the wrong one,” without questioning the structures that created and maintained institutional whiteness in the first place (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 34). Ahmed also suggests that commitment to diversity may conceal racism because it contradicts the positive image reproduced through diversity work (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 142, 152–4).

These theories and concepts of institutional racism; institutional whiteness; and deflection, distancing, and denial as primary strategies for ignoring racism and maintaining whiteness as an institutional norm provide the foundation for our analysis of the European Parliament.

Studying Institutional Whiteness in the European Parliament

Extant research on race and racism in parliamentary contexts provides us with insights for operationalizing these ideas while also demonstrating the novelty of our approach. Parliaments, as institutions, are historically characterized by whiteness and masculinity (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003; Puwar Reference Puwar2004). Parliamentary discourses on issues such as immigration have been studied in terms of racism (e.g., Wodak and Van Dijk Reference Wodak and van Dijk2000). Bartłomiejczyk’s (Reference Bartłomiejczyk2020) nuanced discursive analysis describes the challenges of studying racism in the multilingual context of the European Parliament. Member states have different cultures of racism, and racism is expressed in national languages in different ways, which creates challenges for the parliament’s official interpretation between these languages. Analyzing the descriptive and substantive representation of racialized minorities, in turn, shows that racialized minority politicians address the interests of racialized minorities more often than do their white counterparts and that substantive representation relies on a small group of critical actors (Brown Reference Brown2014; Mügge, van der Pas, and van de Wardt Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019; Saalfeld and Bischof Reference Saalfeld and Bischof2013). We expect this to apply to addressing racism and institutional whiteness in the European Parliament as well.

Research tracing institutional practices and interpersonal dynamics that uphold racialized power and privilege within parliaments has given voice to the perspectives of racialized minority politicians (Brown Reference Brown2012; Reference Brown2014; Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003; Puwar Reference Puwar2004). Racialized minority MPs, women in particular, have been shown to be constructed as “other” and subordinate through tactics such as silencing, stereotyping, enforced invisibility, exclusion, marginalization, and challenges to epistemic authority (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003, 546). Nirmal Puwar (Reference Puwar2004, 31) uses the term “space invaders” to describe “racialized minorities in positions of authority historically reserved for specific types of white masculinities.” Even if Black bodies constitute a minority, they would be perceived as a threat (Puwar Reference Puwar2004, 48). We expect to see similar tactics of othering in the European Parliament as well.

Our specific focus is on institutional practices of silencing racism and antiracist work to call out such behavior, which shifts the perspective from experiences of marginalization to the perpetuation and challenging of institutional racism and whiteness. In this respect, studies on other parliaments have mapped strategies such as the creation of institutional mechanisms and support networks (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003, 538). Such institutional mechanisms in the European Parliament include the High-Level Group on Gender Equality and Diversity, which was appointed by the Parliament and leads some internal equality and diversity work, as well as the informal Anti-Racism and Diversity Intergroup (ARDI), which brings together members interested in antiracist policies and internal practices.

Beyond individual actors and the parliament as a whole, political divisions provide an important context for the investigation of normative whiteness and institutional racism in the European Parliament. The MEPs sit in seven transnational political groups in which members are required to share “political affinity,” according to the parliament’s rules (Kantola, Elomäki, and Ahrens Reference Kantola, Elomäki, Ahrens, Ahrens, Elomäki and Kantola2022). The political groups negotiate policies and decide on internal rules and practices, including tackling racism. In the 2019–2024 legislature, the political groups included, in order of size, the center-right and conservative European People’s Party (EPP), with a large Christian-Democrat majority; the center-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D); the center-right and liberal Renew Europe; the far-right group Identity and Democracy (ID); the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA); the increasingly radical right populist European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR); and the Left (GUE/NGL).

The European Parliament has traditionally been analyzed as a two-dimensional political arena structured along a left-versus-right socioeconomic cleavage (Hix, Noury, and Roland Reference Hix Simon and Roland2007). More recently, the political groups have been classified along the dimension of GAL (Greens, Alternatives, and Libertarians) versus TAN (Traditionalists, Authoritarians, and Nationalists; Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). On matters of equality and human rights, there are often stark differences between groups located on the TAN side and those located on the GAL side. Previous research has illustrated that the rise of the far right in Europe in the 1990s and early 2000s was important in catalyzing the left into action and using EU institutions to advance the Racial Equality Directive (Givens and Evans Case Reference Givens and Case2014, 6). However, we expect that the division is not as clear-cut when we consider racialized discourses and practices. Based on critical race theory and previous research on race and parliaments, neither the TAN nor the GAL group can be absolved of racist behaviors and narratives or ignorance regarding race and racism.

We contend that analyzing the maintenance of whiteness as an institutional norm in the European Parliament requires paying attention to three institutional layers and their interactions. These are (a) individual members of parliament, (b) political groups, and (c) the European Parliament as a whole. These three are crucial to understanding how institutional racism works within the Parliament and how it can be challenged. Analyzing individuals shows how MEPs and staff select their activities, either explicitly addressing racism or engaging in practices of deflection, distancing, and denial. Focusing on political groups illustrates the role of these key institutional power players in response to institutional racism, as well as in implementing (or not implementing) antiracist practices of their own. Finally, scrutinizing the Parliament as a whole demonstrates how the parliament works as an EU institution and the weight it gives to addressing institutional racism. Together, these three levels of analysis allow us to explore institutional practices, processes, and norms while simultaneously acknowledging the space for and the role of individual agency in shaping them.

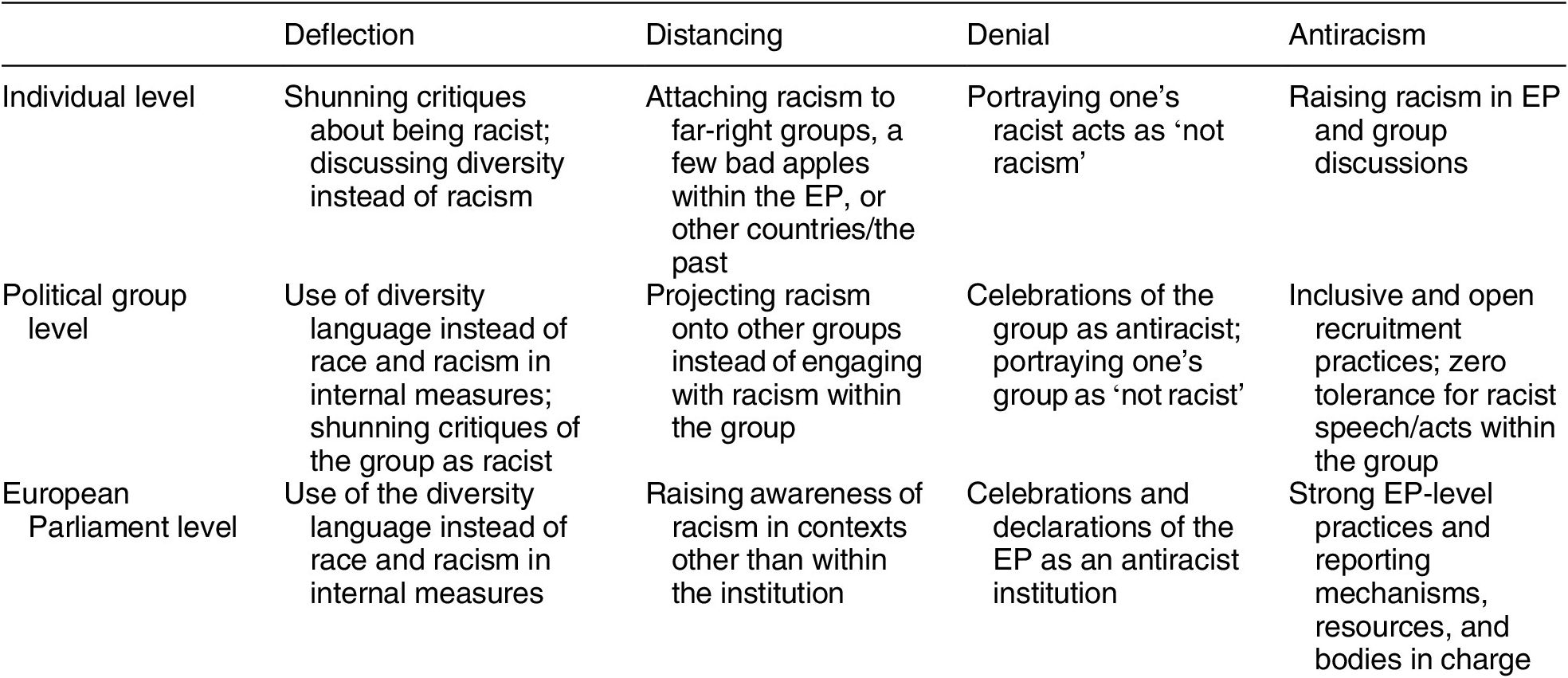

Focusing on these different levels of analysis enables us to systematically show how deflection, distancing, and denial, as techniques for trivializing race and racism, function in the Parliament and analyze the multidimensionality of antiracist work within the institution. We expect to observe deflection, distancing, denial, and antiracist activities at all three levels. Based on the extant literature, we can form expectations about what forms deflection, distancing, denial, and antiracism may take at each level, as illustrated in Table 1. The individuals, the political groups, and the European Parliament, as an institution, may all be complicit in maintaining institutional whiteness and concealing racism as well as being instrumental in countering racism.

Table 1. Maintaining and Challenging Institutional Whiteness in the European Parliament

Research Methods and Material

We conceptualize the European Parliament as a multilayered deliberative space in which supranational institutional and party politics are negotiated and constructed by individual MEPs. Thus, we build on constructionist approaches to analyze how the parliament exhibits institutional racism by upholding whiteness as a set of normative practices (cf. Frankenberg Reference Frankenberg1993). Such an approach allows us to decipher the micropolitical complexity and nuance regarding normative issues such as antiracism (Bracke, Manuel, and Aguilar Reference Bracke, Manuel, Aguilar and Solomos2020, 359). Our approach explores internal conflicts and differences both between and within political groups.

Methodologically, analyzing both discursive practices and institutional practices is at the center of our endeavor. In line with our theoretical approach to race as a social construct, which has real effects, we approach the research material as putting forward constructions of race, racism, and antiracism within the institution. These constructions can be studied as discursive practices that sustain power relations—for example, through normative whiteness. They become the “truths” about racism and antiracism within the institution and have tangible effects on possibilities for action within institutions (see, for example, Lombardo, Meier, and Verloo Reference Lombardo, Meier and Verloo2009). To capture the dynamics of institutional racism, this analysis of discursive practices must be complemented with an analysis of institutional practices. An analytical distinction can be made between formal institutions as codified institutional activities, the rules of which can be read from official documents, and informal institutions as enduring rules, norms, and practices that are normally not codified but still shape action and behavior (Chappell and Mackay Reference Louise, Mackay and Waylen2017, 279).

The research project this article builds on focused primarily on aspects of gender and how they play out in political groups, selected policies, and institutional settings. We understand that researchers cannot avoid sociostructural and situational factors such as age, gender, professional status, or opinions (Abels and Behrens Reference Abels, Behrens, Bogner, Littig and Menz2005, 177). The research team consists of women researchers self-identifying as white and belonging to ethnic majority groups in their respective home countries and the EU more broadly. As white researchers studying racialized relations, we are aware of the limitations regarding our understandings of racialized minorities’ experiences (Brown Reference Brown2012) and right to access “safe spaces” for people of color and antiracist activists (Rastas Reference Rastas2004). We acknowledge the limitation of our research methodology resulting from our positionality: what we can inquire about and observe in our interviews and ethnographic observations may limit our ability to grasp many aspects of both antiracist resistance and experiences of racist microaggressions (see Brown Reference Brown2012). We countered this via the focus of our research: identifying racist discourses and practices that sustain whiteness as a norm within the Parliament in an attempt to recognize the power of racialized discourses, racializing practices, and our positionality within these racialized hierarchies (cf. Rastas Reference Rastas2004). Following Rastas (Reference Rastas2004, 96), this included the “constant scrutiny of assumptions included in the research frame” and concepts “situated within the discourses of race, and how they might potentially either reproduce or challenge those discourses.” We reflected on the influence that our positionality had on data collection and analysis in various team meetings.

Our interview data consist of 140 interviews with MEPs, political group staff, and parliamentary administration, which were conducted in Brussels and remotely (2018–2021), as well as a parliamentary ethnography documented in the form of field notes.Footnote 1 Ten percent of interview participants were from racialized minorities: six MEPs (two women, four men), five group staff (two women, three men), and one parliamentary staff member (woman). Two MEPs from racialized minorities were shadowed—one woman and one man. Additionally, we examined the Parliament’s Rules of Procedure, the statutes of the political groups, resolutions and activities of the ARDI, parliament-related events, and parliamentary press releases.

The interviews covered the democratic practices of political groups, leadership, MEP/staff lives, behavior and conduct, and policy-making practices. The interviewees signed consent forms concerning data protection (see Kantola et al. Reference Kantola, Elomäki, Gaweda, Miller, Ahrens and Berthet2022). All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and anonymized. Although gender was understood intersectionally in the interview guide—which contained questions such as “What about other axes of difference/categories of inequality?” and “Which equality questions are easy to negotiate within the group and form a joint stance? Which are difficult?”—the semistructured interview format allowed additional topics to originate during the interviews (Corbin and Strauss Reference Corbin and Strauss2008, 28). Intersectional aspects and racism within the Parliament frequently emerged from the interviews and were actively pursued by the interviewer.

The parliamentary ethnography (see also Miller Reference Miller, Ahrens, Elomäki and Kantola2022) consists of a broader corpus of 192 pages of field notes taken during onsite visits in Brussels and Strasbourg over a period of 55 days during 2018–2020. In total, we shadowed nine MEPs and accessed 10 political group meetings. The ethnographic fieldwork offered opportunities to identify and talk with prominent individuals in antiracist initiatives, attend antiracism events organized by intergroups and individual MEPs, and follow debates on intersectionality in meetings (see the list of Research Material in the Appendix).

All interviews and ethnographic fieldnotes were coded deductively and inductively with AtlasTi in a team-coding process. For this article, we included the codes “Intersectionality/Race” and “Racism.” “Intersectionality/Race” included all mentions of intersectional aspects of race both implicitly and explicitly (experiences, practices, and policies). “Racism” included all descriptions of racist practices, experiences about racism, and antiracist practices, such as events attended, outrageous racialized language and terminologies, and discussions of migration background. In the analysis, we were sensitive to the positionality of those using terms, such as migration background, which could have different inflections, depending on the political group. In team meetings, we discussed all quotations and codes, then distinguished them in relation to political groups and, finally, heuristically compiled them into the results presented in this article. Institutional racism and the European Parliament’s whiteness appeared as meta-topics when analyzing a collection of related deductive and inductive codes.

Analytically, we applied Lentin’s (Reference Lentin2016) differentiation of (a) deflection, (b) distancing, and (c) denial to discern various types of attention to and engagement with institutional racism and maintaining normative whiteness. First, we divided codes by political groups and marked which interview citations addressed the European Parliament and its institutional components. All citations mentioning racism or racist incidents independent of the Parliament were disregarded. Second, we developed a systematization along different institutional levels—individuals, political groups, and the Parliament and its administration—and extracted activities (or the lack thereof) on the part of relevant actors. In the empirical analysis, we present the results for the various levels originating from our qualitative analysis.

Given the diversity of national contexts in which racialized social relations are described and the different positionalities of individuals in racialized social hierarchies, the “politics of naming” matters. Our analysis of the European Parliament, where national delegations additionally employ different terms, led us to consider which term to use: BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic), BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), PoC (People of Color), racialized people, or racialized minorities. We decided to use “racialized minorities” because, unlike words referring to color, it entails less risk of essentialism and is less embedded with racist ideas (Rastas Reference Rastas, Essed, Farquharson, Pillay and White2019). Unlike “racialized people,” it does not suggest that only nonwhite individuals are racialized (Rastas Reference Rastas, Essed, Farquharson, Pillay and White2019). However, we retained the original acronyms and terms that individuals, organizations, and institutions used to refer to themselves or their work.

Maintaining Whiteness in the European Parliament

In this empirical section, we analyze how whiteness, as an institutional norm, is maintained and challenged in the European Parliament via operationalizing the multidimensional framework above (Table 1). First, we focus on individual MEPs to trace their constructions and actions regarding racism in the Parliament. Second, we focus on political groups to analyze the differences and conflicts within the Parliament. Third, we scrutinize the Parliament’s practices at the institutional level. These three levels show that unchallenged individual racist practices aggregate at the institutional level in a way that reinforces deflection, distancing, and denial. We demonstrate that, for each level, deflection operates via shunning critiques by emphasizing diversity language; distancing operates via putting blame on “bad apples,” referring to individual far-right MEPs, other groups, or other EU institutions; and denial operates via celebrating one’s self/group/institution as nonracist. Antiracist practices are manifest in only a few exceptions.

Individual Level: Everyday Racism

Public accounts of individual MEPs describe normative whiteness and everyday racism in the European Parliament: not feeling welcome in the parliament (Magid Magid, Greens/EFA, UK), having difficulties in advancing issues such as Roma rights (Soraya Post, S&D, Sweden), or testifying against the racist actions of the Belgian police (Pierrette Herzberger-Fofana, Greens/EFA, Germany). Our own interview material also shows such everyday racism toward racialized MEPs and staff across political groups and regardless of the member state.

A sensitive topic for many, the term “race” was rarely used. Instead, our research material relays an epistemological effervescence with various references to “ethnic origin,” “people of color,” “BAME,” “people like me,” “the skin issue,” or “the color aspect.” Some interviewees expressed their personal sensitivity to the issue but would not talk about racism directly, as evidenced by the interviewee who initially said, “For me personally, as a migrant child […],” and then continued, “I’m always fighting […] for all the, I won’t say minorities, but you know what I mean, for these kind of groups in our society” (Interview 17). This reflects the fact that talk about racism can lead to denials of racism (e.g., El-Tayeb Reference El-Tayeb2011; Salem and Thompson Reference Salem and Thompson2016; Rastas Reference Rastas, Essed, Farquharson, Pillay and White2019). Some interviewees explicitly discussed racism within the European Parliament and described its “subtlety,” calling it “dinner-party racism” or “polite racism,” which is far more difficult to combat than openly racist acts and “far more pernicious” (Interview 4). Although it is “everywhere,” it is not “something that you can pinpoint and say, ‘that is racist’” (Interview 37). One staff member discussed her experience of subtle forms of everyday racism and the difficulties involved in reporting such to the institution: “I don’t make any complaints, because I don’t see the point. […] What am I gonna say? He [security guard] spends two seconds longer on my badge than he does the other people?” (Interview 9).

Diversity, in contrast, remained a preferred term for many. Analyzed as a form of deflection (cf. Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012; Lentin Reference Lentin2016), this “happy” term recognizes a lack of descriptive representation but steers attention away from institutional practices and cultures that organize and perpetuate racialized hierarchies within the Parliament. As illustrated below in the section on political groups, despite acknowledging problems with representation, interviewees across the political spectrum engaged in celebrations of diversity within their groups or national delegations: “I think that is not an issue for us […] We have Black people” (Interview 18); “We’ve got Black MEPs, ethnic minority MEPs … they’re totally part of it” (Interview 6); “We had even somebody from Asia, from Korea” (Interview 20); “We got good diversity” (Interview 36). By devoting their attention to what they saw as positive examples of diversity, MEPs and staff disregarded the broader processes, practices, and culture that reproduced racialized hierarchies and whiteness within the parliament.

One interviewee raised concerns about how, in the parliament, the term “diversity” was chiefly used with reference to LGBT+ and gender issues (Interview 4). This suggested the existence of a hierarchy between inequalities, with race being at the bottom (cf. Hancock Reference Hancock2007). For instance, one interviewee said, “Well, the European Parliament, as a whole, is well ahead of almost all the national parliaments in terms of its own composition when it comes to gender balance, but it’s not so good when it comes to ethnic and ethnic minority and Black representation” (Interview 3). The same interviewee suggests that a term such as “diversity,” which comprises different categories, is strategically put forward to hide pitfalls regarding racialized minorities. Concerns about structural racism were also expressed and defined as pervasive and invisible. Several interviewees described institutional racism with the example of the division of labor between MEPs and cleaners: “In Strasbourg, when you arrive at eight o’clock, all these women with their scarves are coming out, and we are all there, these ladies with our nice little suits and our nice little suitcases arriving, and they’re coming out” (Interview 11).

An example of deflection at the individual level was asking the researcher to “define racism” during the interview because “You’re a doctor, so obviously, you should know, right?” (Interview 23) while also claiming that radical right populists are victims of defamatory accusations: “What does it mean? Because I’ve been called it live on TV, I’ve been called it in front of my young children, I’ve been called it in a crowd of thousands of people, and it just makes me laugh because none of them know what they’re saying. What does racism mean?” (Interview 42). In this way, the emphasis was deflected onto definitional disputes, away from racism and its effects.

Devoted MEPs and staff perform a significant role in drawing attention to the racism of the Parliament at both parliamentary and group levels. As discussed further regarding the ECR group below, the diversity work of a political group can rely on one active individual. Also, as argued further below, ARDI Intergroup membership was a significant arena for individual involvement on the part of MEPs and staff alike. These critical actors identified themselves as racialized minorities and connected their sensitivity and activities to their own backgrounds (Interviews 4 and 17) or their own experiences of racism within the institution (Interview 4). Although the lack of racialized minority representation in the parliament was something that white interviewees also recognized (e.g., Interview 6), it was mainly interviewees identifying as belonging to racialized minorities who explicitly discussed racism.

The MEPs engaged in individual practices to challenge the normative whiteness of the European Parliament using parliamentary activities as a tool of antiracist work (e.g., joining the ARDI Intergroup) or urging political groups to act. Sometimes, frustration with formal parliamentary and group activities or the desire to represent their constituencies pushed MEPs to seek other channels. These included efforts to mark religious festivals, such as hosting a Diwali celebration (Ethnographic field note 4). Others challenged the whiteness of the European Parliament via antiracist individual initiatives “funded […] out of my pocket,” specifically recruitment policies and mentoring in the form of a shadowing scheme to get “young people […] from different ethnic backgrounds” to come and work in the EP (Interview 6). Interviewees also stressed the importance of informal parliamentary networks in discussing experiences of racism (Interview 9). One ECR MEP sought to establish such a network but failed because of his “wrong” political affiliation: “Cause I was a conservative” (Interview 4). Few white interviewees spoke about reacting against racism beyond the cordon sanitaire that they believed excluded “racist” far-right MEPs from parliamentary work. One S&D MEP refused to share taxis with openly racist MEPs (Interview 38), and another, from Renew, challenged their opinions informally and spontaneously “in a taxi journey between the parliament and the station” (Interview 39). These show that antiracist individual acts targeted “bad apples.”

Our material reveals that calling out racism, reacting to racist acts in the European Parliament, and formulating antiracist actions often remained a concern of racialized minority MEPs and staff only. The majority of white interviewees who discussed race did so from a diversity perspective that focused on descriptive representation and symbolic celebrations that deflected the conversation away from racism or drew attention to positive examples in a manner that resembled denial.

The Political Group Level: Lack of Internal Antiracist Practices

In this section, we inquire into how political groups address race and racism and promote diversity or antiracism. Political groups are implicitly bound by EU Regulation 2018/673, which obliges them to “respect […] the rights of persons belonging to minorities” (Morijn Reference Morijn2019, 630). We show that none of the political groups placed fighting racism at the heart of their politics. None had significant internal practices for combating racism or promoting antiracism. For some, we observed distancing strategies that presented racism as a problem of far-right groups; for others, we observed outright denials of racism as a relevant issue in the Parliament or Europe. Our interview analysis suggests dividing the political groups into three clusters.

Deflection and Distancing by GAL Groups

The S&D, Greens/EFA, and Left GUE/NGL, which all belong to the GAL side of the GAL–TAN axis, each demonstrate an awareness of the lack of representation of racialized minorities. Some of their individual MEPs are proactive, as seen above, but political groups, as a whole, are not. Antiracism is not at the core of their identity, which ultimately reproduces the normative whiteness of the European Parliament. The groups frequently used deflection and distancing strategies when discussing racism (cf. Lentin Reference Lentin2015).

Beginning with the S&D, the largest and most powerful of these groups, the interviewees identified a lack of representation of racialized minorities and were more likely than were others to acknowledge Europe’s colonial history and structural racism in the European Parliament (Interviews 9 and 40). For instance, one interviewee said that “Skin color is a different question in this house… . It’s incredible how white we are here” (Interview 43). However, some attributed racism to the radical-right political groups ENF/ID and EFDD and to “the threat that the far-right is” (Interview 5), with S&D forming “a big block against the right wing, against the racists” (Interview 17). Constructing racism as a problem for only far-right groups constitutes a distancing practice, reinforcing the “exceptionality” of racism and diverting the conversation away from everyday structural racism within more mainstream political groups or the parliament. By pointing to others, S&D overlooks subtle racist group practices and the need to support antiracist activities, thereby reproducing normative whiteness. Racism within S&D was sometimes openly rejected: “That is not an issue for us. […] We have Black people, and it’s just colleagues. For us, it’s not a question of color” (Interview 18). Such constructions of being “color-blind” are part of normative whiteness that perpetuates racist practices by making it harder to discuss them. Indeed, one interviewee spoke about the difficulties of raising the issue of racism within the group (Interview 40). This illustrates how the group shuns criticism regarding being racist.

Interviewees from S&D claimed to actively recruit underrepresented groups (Interviews 19 and 20), notably by including them in the group’s secretariat and traineeship programs. This contributed to countering normative whiteness despite the official rules: “It was difficult, according to the statute, but we found a way” (Interview 20). However, these rules were also used as an excuse for not doing better: their efforts were “not focused on ethnicity. Because this is forbidden by EU staff regulations, we cannot discriminate on [the] basis of race or ethnicity, and this is imposed on us” (Interview 19). Some interviewees commented critically on the lack of a proactive stance toward antiracism and intersectionality in S&D policies (Interviews 5, 18, and 41). One interviewee used time constraints and prioritization as a justification: “A lot of the time, it does come down to time constraints, and really, this should be the first thing we look at rather than the last” (Interview 41). Normative whiteness manifests itself and is reproduced through not seeing antiracist practices and policy work as a priority.

Interviewed Green/EFA MEPs and staff identified a lack of both the representation of racialized minorities and intersectional approaches in European Parliament’s policies, constructing them as problems. “Lack of diversity in terms of race backgrounds and the BAME communities” was described as “a really pressing problem compared to the gender issues” for the group (Interview 8). Equality was not only “for wealthy white women” and cannot be reached “by exploiting women with a migrant background” (Interview 11). This citation illustrates that, for the group, diversity is not achieved if one considers only gender issues. A staff member noted it was, “again and again, a theme in discussions that we are so little diverse” (Interview 10). However, in practice, the group addressed the problem only partially by using standard sentences about diversity in job announcements. Furthermore, there was no concerted action, and the group statutes (governing political groups’ work) did not include any specific regulations on preventing racism or promoting diversity. Despite the limited number of MEPs from racialized minorities (ENAR 2019) and the lack of internal practices in the group, interviews showed that the Green/EFA’s self-image was that of upholding equality. One interviewee said it was “a Green thing” to emphasize, in job announcements, that people from different backgrounds “including disabled and migration backgrounds” were “especially welcome” to apply (Interview 10). However, this statement—despite attempting to illustrate how the political group has made an effort to become more accessible and inclusive—can be interpreted as a manifestation of normative European whiteness; it connects race and racialized discrimination to migration rather than perceiving them as a part of European society.

The interviewees from the left group GUE/NGL acknowledged the lack of representation of racialized minorities and racism as problems in the European Parliament but felt the group did well compared with others: it had a “better than average” representation. Racism had no place within them, and they would be “inclusive to the max” (Interview 13). As the group was portrayed as antiracist, racism was attributed to radical-right groups (Interview 14). However, engaging with racism was also presented as dependent on national delegations. One interviewee stated, “I feel like, culturally, for some parties, that’s important and, for other parties, it’s not […]. It’s Marxist economic determinism. It’s not about skin color or sexual identity […]. Gender changed some over the last 20 years, but it’s still on the other things, like, no, capitalism is the problem. It’s about money” (Interview 15). This citation suggests that some GUE/NGL delegations still saw taming capitalism as the priority, which shows patterns of deflection as well as class (and gender) trumping concerns about racism. Simultaneously, framing racism as a feature of specific countries rather than as an institutional norm in the European Parliament and within political groups can be a form of distancing.

Engagement with diversity existed in the group, and GUE/NGL attended to it in their recruitment practices, but race/ethnicity was treated as one of many dimensions of discrimination (Interview 16). The press office attempted to employ more diverse images regarding skin color and headscarves, but interviewees reported no proactive stance in terms of fighting racism and white privilege. Furthermore, focusing on diverse visuals is insufficient for tackling racism and can be read as a form of deflection that diverts attention away from institutionalized racism by creating an impression of equality.

Denial and Deflection in the TAN Groups

The ECR, EFDD, and ID/ENF represent the TAN side of the GAL–TAN axis. Interviewees from these groups discussed racism but engaged in practices of deflection and denial to refute accusations of being racist. Sometimes, they denied the existence of racism altogether.

Against expectations, some ECR interviewees were outspoken about representation issues and racism within the parliament (Interviews 4 and 26). One stated, “I think the race issue is a massive issue, and it is ignored here, hugely. People just don’t care about it” (Interview 25). Several interviewees mentioned the ECR as being “fairly strong […] on issues to do with race” (Interview 27), as evidenced, according to them, by the relatively high number of racial minority MEPs in the group because of the British delegation (before Brexit), as well as the fact that, during the 2014–2019 term, the group had the first Muslim group leader in the European Parliament. These celebrations of the group as antiracist can be interpreted as denial, given that the group includes several openly racist political parties (McDonnell and Werner Reference McDonnell and Werner2019). The group also considered promoting racialized minorities in recruitment, selection, or promotion “unfair” because “whoever’s the best person will get the job and that’s that” (Interviews 27 and 28). The ECR worked on diversity issues due to pressure from individual UK MEPs (Interviews 4 and 28) but focused on challenging stereotypes and creating positive images of racialized minorities: “We wanted to tell a good story about Africans, creating wealth and creating business, not being all poor people that live in huts” (Interview 4). The persistence of backward views about racialized minorities in the Parliament was illustrated in that racial stereotypes were addressed through events but, at the same time, racialized power relations, including at the Parliament level, remained unchallenged. Brexit revealed that these initiatives were not institutionalized in the group because they were discontinued after the committed MEPs left, and with the Polish Law and Justice Party currently dominating, antigender and racist statements are now frequent (cf. Bartłomiejczyk Reference Bartłomiejczyk2020).

The EFDD and ENF/ID interviewees engaged in practices of deflection and denial in the face of accusations too. For instance, the EFDD amended its statutes when the group was accused of racism (Interview 29), writing that the group “rejects xenophobia, antisemitism and any other form of discrimination” (EFDD 2017, §3). One interviewee said, “We absolutely deny being any of those things, and sometimes, it’s useful to say we’re not, that’s not what we are (Interview 29). However, interviewees could not provide evidence of rule enforcement. One interviewee from ENF acknowledged that having “a brown face” in their group protects them from racist accusations, but also accusing racialized minority MEPs of “[knowing] that and [taking] advantage of it [as a] way to get on in politics” (Interview 30).

Practices of denial led to disregarding racism within the group and in the European Parliament. One interviewee said, “I’m not seeing any racism from anyone. Not just our side, anyone” (Interview 24). Several interviewees from the far-right national party delegations in the EFDD denied the existence of racism as a historical phenomenon and constructed racism as “invented” (Interview 32) or “made-up” (Interview 24), as illustrated in the following citation: “As regards racism, well, it’s irrelevant really, sort of a […]. What is racism? That’s a very good question. It’s invented by all the people who want to cause difficulties” (Interview 32). One interviewee described the word “racist” as having “no useful meaning” (Interview 33). Denial of racism can itself be a form of racist violence (Lentin Reference Lentin2018), and these citations exemplify how the rejection of xenophobia in group statutes fulfilled a merely strategic function.

Blind Spots and Silence

Finally, our interview material with the conservative EPP and the liberal Renew/ALDE contains few references to race and racism. Only one Renew/ALDE interviewee acknowledged the absence of racialized minority representation and proactive measures in this respect. “We’re pretty rubbish on minority ethnic issues. […] If you look at the minority ethnic diversity across the group, once you take out the Brits […], take out the British staff, then you’re definitely struggling to see anyone of color. That’s true, of course, across the entire set of institutions, and one of the reasons is that they don’t measure, but that’s only one of the reasons” (Interview 21). None of our EPP interviewees described the representation of racialized minorities or racism in the Parliament, let alone in their group. When asked about equality issues of any kind, one interviewee mentioned LGBTI rights but not those of racialized minorities (Interview 34). Normative whiteness is strengthened by this near silence on race and racism.

Regarding practices, the groups’ statutes make no reference to equality issues.Footnote 2 The reasons for this may be different because the political ideologies of the two groups differ starkly: the EPP is a strongly conservative group in relation to equality issues, and the Renew/ALDE is a liberal group that emphasizes individual-level action and responsibility regarding equality. Our interviews suggested that diversity work in the EPP was reduced to generating the correct image for outside audiences (cf. Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012, 76–7). As stated by one EPP interviewee, “Our imagery must be diverse. […] Different colors. Different parts of the world. Different genders. Everything. We are not only communicating to north-European white people” (Interview 35; also Interview 22). The same interviewee asserted that EPP would not tolerate racist comments from its MEPs. However, considering the difficulties of the EPP in dealing with the Hungarian Fidesz membership—a radical-right populist party rejecting human rights values—prior to 2021, when it left the group (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020), the blind spot in our interviews stands out. Our research material with Renew/ALDE does not enable more in-depth analysis or conclusions on the matter.

The European Parliament Level: Upholding a Positive Image

At the European Parliament level, we analyze how the constructed antiracist self-image of the parliament is not institutionalized in its Rules of Procedure, with an evident lack of disciplinary measures. We discuss the ARDI intergroup as a primary antiracist actor that, nevertheless, lacks a formal parliamentary role and further exposes the cracks in the nonracist self-image of the parliament.

Similar to gender equality, the European Parliament constructs itself as the “good” institution vis-à-vis other European and national institutions (Berthet and Kantola Reference Berthet and Kantola2021). The language of the “big, big majorities” that won support for nonlegislative resolutions on antiracism (Ethnographic field note 1, 15) paint the institution as more progressive compared with what the Council and national parliaments are accomplishing, at least politically. However, this meta-construction veers toward deflection and distancing by changing the focus to national or other European institutions while protecting the political reputation of the European Parliament. This was explicitly articulated by one Eurosceptic MEP: “The presentation is often that the European Union is fighting for equality and diversity. It’s a great enlightened set of institutions. They’re the good guys, and anyone who doesn’t want to be in the EU are backward, xenophobes, or whatever” (Interview 2). An S&D MEP explained that most groups understand the EU’s slogan of “United in Diversity” as meaning “united in the EU” rather than in terms of “background” or “color” (Interview 5). Adding to this, race is continuously conflated with migration, be it in the different national cultures of racism visible in official interpretations (Bartłomiejczyk Reference Bartłomiejczyk2020) or radical-right populists stigmatizing migrants and reifying other cultures and inequalities as “non-European” problems (see Wodak and van Dijk Reference Wodak and van Dijk2000).

It is pertinent to consider how the parliament functions as a potentially antiracist actor beyond such discursive practices. For instance, events are critical to reproducing the image of a “good” institution and recognizing racism and antiracist work. Such events included regularly commemorating International Holocaust Memorial Day, marking the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination with an internal roundtable for the European Parliament’s staff in 2021, and arranging a conference on slavery in the same year. However, our ethnographic field notes show that civil society actors participating in these events were skeptical about their effectiveness and alluded to the tokenism of antiracist interventions as “cute,” inquiring “what happens next?” (Ethnographic field note 2, 27). One participant said, “these events are beautiful [but], they peak and then do nothing” (Ethnographic field note 3, 33). The adjectives “cute” and “beautiful” correspond with Ahmed’s (Reference Ahmed2012) discussion of the nonperformativity of affective antiracist language and diversity work as creating the “right image.” Indeed, one MEP noted that the liberal aesthetic of these days of recognition stands in contrast with the absence of important “building blocks” in the parliament, such as diversity monitoring (Interview 1). A staff member pointed out that “[t]his is a house that discusses policies and all that stuff, but yet they don’t really practice what they preach” (Interview 9).

Importantly, the Parliament’s Rules of Procedure (2021) do not mention “race/racism/ethnicity” specifically. They contain some provisions about condemning individual racist acts, but the provision prohibiting “racist and xenophobic language” in parliamentary debates was recently replaced by one prohibiting “offensive language” (Rule 10.4) following a court case involving former MEP Janusz Korwin-Mikke.Footnote 3 Following the insistence of the court, the parliament had to replace the terms “defamatory, racist or xenophobic language or behaviour” with the more generic term “offensive language” (Interview 3). One interviewee suggested that this weakened the ability of the European Parliament to tackle racist speech because “offensive language” was not as specific as racist and xenophobic language and may not cover ambiguous “polite racism,” such as “stereotypes [and] the views of Muslims as being backward,” which one interviewee described as typical (Interview 4). The fact that the assessment of offensiveness should consider the “identifiable intentions of the speaker” left considerable room for denying racism. Official complaints were available to those who wished to report racist acts (Interview 17), but the lack of disciplinary measures made reporting inefficient. For instance, one interviewee described having witnessed blatant acts of racism on a delegation trip to Congo, but would not report them. It would be futile because “they don’t sack people in the institution” (Interview 9). Similar dynamics were visible in the context of gender equality and the #MeTooEP movement against sexual harassment within the Parliament. Here, European Parliament actors pushing for disciplinary measures against sexual harassment met with an unresponsive hierarchy whose agenda was to protect the institution’s good reputation (Berthet and Kantola Reference Berthet and Kantola2021).

In addition to formal rules governing parliamentary work, dedicated actors and structures for antiracism in the parliament are relevant. The Anti-Racism and Diversity Intergroup, established in 2004, is a central actor for antiracist activities in the Parliament. Most antiracist resolutions in the 8th (2014–2019) and 9th (2019–2024) legislative terms saw the involvement of ARDI Intergroup MEPs. However, parliamentary intergroups execute no formal parliamentary function. Rather, an intergroup is “informal,” “consisting of members from different Political Groups with a common interest in a particular theme” (Corbett, Jacobs, and Neville Reference Corbett, Jacobs and Neville2016, 243). Intergroups cannot use the Parliament logo because they are categorically “not organs of parliament” (Conference of Presidents 2012, Art. 1–3). Thus, antiracist work has been delegated to an informal group, which reveals the low level of attention paid to this issue in the Parliament. Delegating the work to informal spaces might divert attention away from the responsibility of other actors in the Parliament. Partly, this resembles the situation regarding gender equality issues in which the Women’s Rights and Gender Equality Committee (FEMM) has a special neutralized status, limiting its power and entailing “an additional workload, thematic exclusion and symbolic disregard” (Ahrens Reference Ahrens2016, 2).

Nevertheless, a notable construction in the interviews was representing ARDI as a politically efficacious intergroup. One interviewee said they decided to join ARDI because of being “kind of sick” of institutionalized whiteness, which included sitting in meetings “of about 50 people talking about trade” in which “every person in the room was white” (Interview 6). One interviewed member of ARDI strongly defended its successes. The intergroup was argued to have been “smart” about its scarce resources: it wisely picked an external secretariat and recruited a leadership with significant antiracist accomplishments in civil society (Interview 1). Thus, the political efficacy of ARDI was based on individual capital, MEP and staff experience in civil society organizations, and committee memberships (Interview 5; see also Landorff Reference Landorff2019), meaning that its expertise depended on its composition.

Finally, we noted that articulating political efficacy negated pragmatic struggles in intergroup maintenance, such as capturing resources to implement a fully online reporting facility for racist incidents in the parliament (Ethnographic field note 1, 8). Consequently, intergroup activity was interpreted by one MEP as intermittent in the mandate (Interview 6). Others suggested that antiracism could be more systematically integrated into parliamentary committee work (Interview 7) to free ARDI for further activity. The rules regarding intergroup formation require representation from three political groups (Conference of Presidents 2012, Art. 4), which resulted in cooperation. Some interviewees constructed the rule as also beneficial to ARDI to attract members from the conservative EPP and thereby show its credentials as a mainstream actor (Interview 1). However, as a result one member felt they had to compromise wording in outputs to gain support from across the groupings (Ethnographic field note 1, 11).

In sum, we conclude that, at the parliament level, whiteness was reproduced, first, by the uneasy articulation of a progressive institution vis-à-vis other national and European institutions and symbolic celebrations that sustain the “right image” of the Parliament, which veers toward deflection. Second, the Rules of Procedure in relation to offensive language leave room for racializing hate speech and the denial of racism. Third, antiracist work was delegated to an informal body with discursive and material constraints.

Conclusion

Racism in the European Parliament is systemic, institutionalized, and perpetuated by the normative whiteness of the institution. Whiteness operates as unchecked privilege and “political color-blindness” in the parliament. By employing Lentin’s (Reference Lentin2016) concepts of deflection, distancing, and denial, the article revealed the multiple methods of silencing race and racism in the parliament as well as the interplay between these three mechanisms from the micro to the macro level. The experiences of individual MEPs and staff—although sometimes acknowledged and condemned as unacceptable—remain individualized instead of being recognized as requiring institutional solutions. Antiracist measures by political groups are not formalized or required by the Parliament as an institution but, rather, depend on critical actors such as individual MEPs or the informal ARDI intergroup, both of which lack the institutional power to enforce changes.

Arguably, the entire self-construction of the Parliament tended toward deflection by moving the focus regarding racism to the member-state level or other European institutions while protecting the progressive institutional reputation of the Parliament. Via this mechanism, the Parliament generated a positive self-image and reproduced its whiteness. Simultaneously, the party competition system and the far-right groups’ presence made the Parliament more prone to adopt distancing as a tactic. Some political groups constructed racism as only being a problem for far-right groups. Regarding strategies of denial, the Parliament’s Rules of Procedure covering only individual racializing hate speech meant that structural forms of racism were overlooked. Additionally, we observed more outright forms of the denial of racism in the Parliament. Surprisingly, MEPs from socialist and left groups were complacent regarding racialized minority representation among colleagues.

As shown in the article, attempts to tackle racism existed but were unsystematic and mainly directed at the wider public and managing the image of the Parliament instead of transforming internal parliamentary practices. Antiracist actions at the MEP, political group, and parliamentary levels were disconnected, offering a mere smokescreen. Each level mattered and contributed to reproducing institutional normative whiteness of the Parliament. The effects were captured succinctly by the metaphor of “shouting to the brick wall,” as used by one interviewee to describe the difficulty of confronting racism in the Parliament. The three intertwined mechanisms—deflection, distancing, and denial—facilitated perpetuating institutional whiteness by allowing actors to shirk responsibilities to any other level, thus making it harder to develop, adopt, and implement antiracist measures. However, who uses which mechanisms may make a difference for the Parliament in responding internally to institutional racism and normative whiteness. The political groups on the GAL spectrum—despite using distancing and deflection—show no denial and, together with the EPP and Renew, which are potentially accessible regarding antiracism, constitute a clear parliamentary majority, allowing them to take formal steps. Thus, the question of whether actors deny the existence of racism outright, making it impossible to initiate institutional change, may be an important one.

The article has demonstrated that despite a recent “upsurge” in antiracist output, as evidenced in European Parliament resolutions, the Parliament was not an internally progressive actor. This finding was enabled by our focus on parliamentary discursive and institutional practices around racism and antiracism, as opposed to policies. Such study of discursive and institutional practices of political institutions could usefully be extended to other EU institutions and to other national contexts in future research.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation for this study and a discussion of the limitations on data availability are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FH5WV4.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the editors of the journal and the anonymous reviewers for engaging with the article and for providing critical and constructive comments, which were extremely helpful to us in developing the arguments, theory and concepts, and the empirical analysis of the article. We would like to thank all our research participants from the European Parliament who generously offered their time to be interviewed or shadowed for the purposes of the EUGenDem research project. An earlier draft of the paper received helpful comments and feedback at Tampere University Gender Studies Research Seminar, and we thank all participants of the seminar. Special thanks to our colleague Anna Rastas at Tampere University whose enthusiasm and comments on an earlier draft of the article were crucial.

FUNDING STATEMENT

The research was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant number 771676.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by Tampere Region Ethics Council and the European Research Council and certificate numbers are provided in the American Political Science Review Dataverse (Kantola et al. Reference Kantola, Elomäki, Ahrens, Ahrens, Elomäki and Kantola2022).

The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

APPENDIX: RESEARCH MATERIAL

Quoted Interviews

-

1. S&D MEP, telephone interview, March 24, 2021

-

2. Non-attached MEP, Brussels, January 27, 2020

-

3. S&D MEP, Brussels, November 27, 2020

-

4. ECR MEP, local capital, December 19, 2019

-

5. S&D MEP, Brussels, January 22, 2020

-

6. Greens/EFA MEP, Brussels, January 21, 2020

-

7. S&D group staff, Brussels, March, 2, 2020

-

8. Greens/EFA MEP, Brussels, February 25, 2020

-

9. S&D group staff, online interview, February 14, 2021

-

10. Greens/EFA group staff, Brussels, April 1, 2019

-

11. Greens/EFA MEP, Brussels, March 10, 2020

-

12. Greens/EFA group staff, Brussels, March 21, 2019

-

13. GUE/NGL group staff, Brussels, May 6, 2019

-

14. GUE-NGL MEP, Brussels, March 16, 2020

-

15. GUE/NGL group staff, Brussels, February 24, 2020

-

16. GUE/NGL group staff, Brussels, May 15, 2019

-

17. S&D MEP, Brussels, March 2, 2020

-

18. S&D group staff, Brussels, February 6, 2020

-

19. S&D group staff, Brussels, March 5, 2020

-

20. S&D group staff, Brussels, April 29, 2019

-

21. Renew MEP, Brussels, February 24, 2020

-

22. ALDE group staff, Brussels, July 13, 2019

-

23. EFDD MEP 1, Brussels, January 29, 2019

-

24. EFDD MEP 2, Brussels, January 29, 2019

-

25. ECR MEP, Brussels, January 31, 2019

-

26. ECR MEP, Brussels, October 18, 2018

-

27. ECR MEP, Brussels, December 5, 2018

-

28. ECR group staff, Brussels, February 20, 2019

-

29. EFDD group staff, Brussels, March 19, 2019

-

30. ENF MEP, Brussels, February 7, 2019

-

31. ENF group staff, Brussels, April 26, 2019

-

32. EFDD MEP 3, Brussels, January 29, 2019

-

33. EFDD group staff, Brussels, February 7, 2019

-

34. EPP MEP, online interview, April 8, 2020

-

35. EPP group staff, Brussels, February 26, 2019

-

36. ECR MEP, Brussels, February 21, 2019

-

37. European Parliament staff, online interview, March 20, 2020

-

38. S&D MEP, Brussels, January 30, 2019

-

39. Renew MEP, Brussels, December 13, 2019

-

40. S&D MEP, Brussels, October 16, 2018

-

41. S&D group staff, Brussels, March 2, 2020

-

42. EFDD MEP 4, Brussels, January 29, 2019

-

43. S&D Group Staff, Brussels, November 12, 2019

Quoted Ethnographic Field Notes

Ethnographic field note 1: Meeting with ARDI Intergroup member, Brussels, December 5, 2018.

Ethnographic field note 2: LGBTI Intergroup meeting: The EU and LGBTQI Rights 2020–2024, Brussels, February 4, 2021.

Ethnographic field note 3: Countering Anti-Muslim Racism in the EU panel, Brussels, January 21, 2020.

Ethnographic field note 4: S&D Shadowing Day, Brussels, October 18, 2018.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.