“Defeat is an orphan.”

—John F. Kennedy

The decision to enter armed conflict is among the most consequential a country can make, and yet is widely believed to be among the least democratically controlled in the United States. Instead, popular wisdom holds that as the possible consequences of armed conflict have grown ever larger, democracy’s grip on the dogs of war has grown ever weaker. While the Constitution clearly endows the legislative branch alone with the power to declare war, in the years since Truman committed the US to the Korean War unilaterally in 1950, hundreds of uses of force have been undertaken absent any kind of vote of approval from lawmakers. The oft-violated War Powers Resolution of 1973, likewise, is widely considered to be a failure.

Americans across the political spectrum overwhelmingly agree that Congress should have meaningful influence over questions of war and peace, and yet nothing seems to change. Since Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s publication of The Imperial Presidency a half-century ago, scores of political scientists, jurists, politicians, and everyday Americans have bemoaned an unconstrained executive in the war powers context—a perspective to which many still subscribe. While some scholars have pushed back against the strongest claims of the imperial presidency thesis over the past two decades, widespread doubt over serious congressional influence in crises continues. Skeptics point to an undeniable reality that many find difficult to reconcile with substantial lawmaker influence: uses of force are almost always undertaken unilaterally by the president.

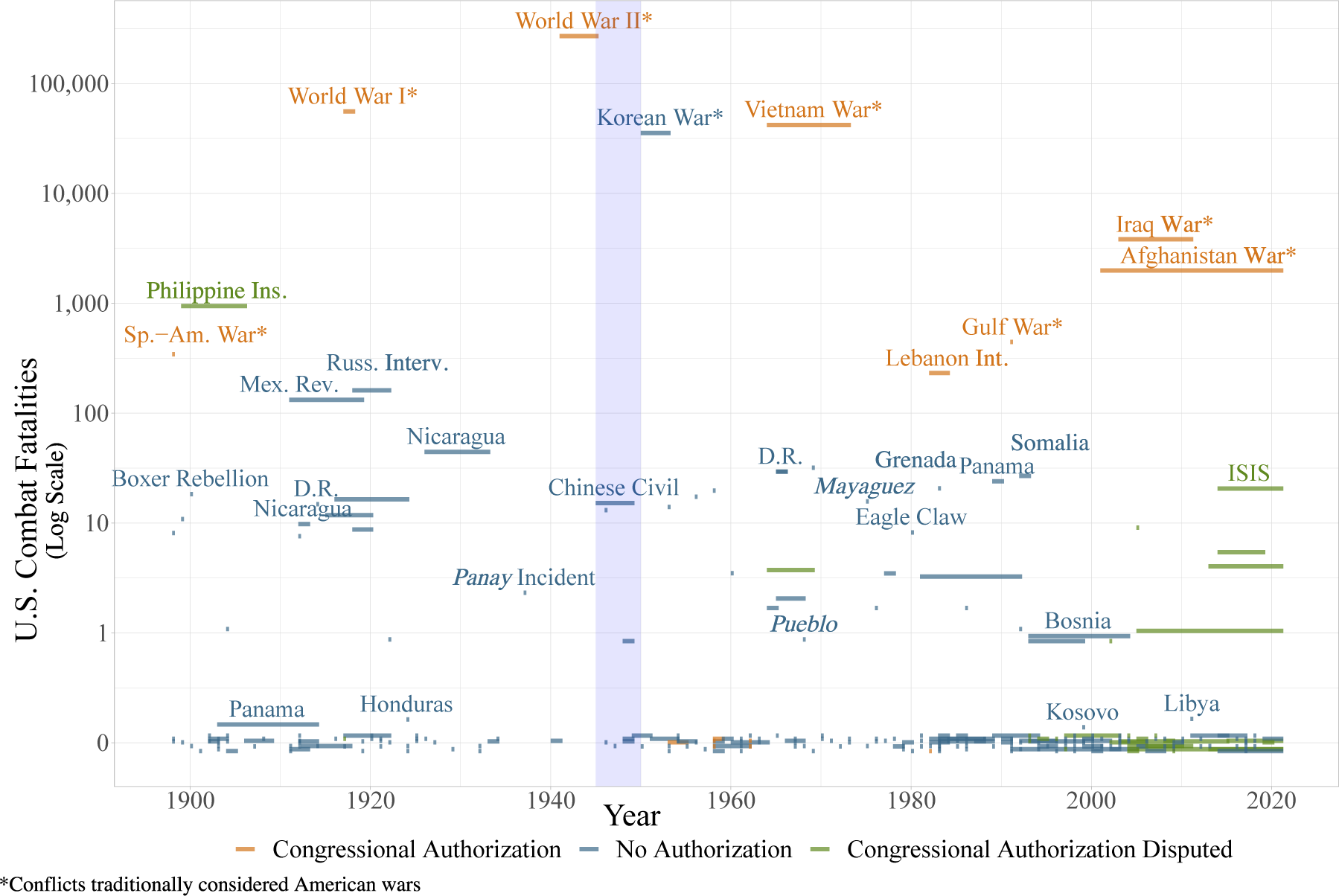

Since Truman’s precedential “police action” in the Korean War, presidents time and again have demonstrated an ability to act without congressional approval. Figure 1, however, presents something of an empirical puzzle: despite the supposed precedential value of Truman’s unauthorized war in Korea, in the subsequent seven decades there has never again been a full-scale war undertaken unilaterally.Footnote 1 In fact, there are several examples of presidents seemingly deterred from the use of force precisely due to a lack of authorization from Congress. Yet, at the same time, smaller uses of force are virtually always undertaken absent Congress’s formal blessing. Why is it the case that in the years since 1950 smaller uses of force have almost always been undertaken unilaterally, and yet full-scale wars have only been initiated after legally binding authorization was acquired?

Figure 1. American Uses of Force by Authorization Status since 1898

Note: Based on MIP dataset (Kushi and Toft Reference Kushi and Toft2023).

This work argues that presidents are highly reticent to undertake full-scale war absent formal authorization from Congress due to their elevated exposure to “Loss Responsibility Costs” (LRCs) when acting unilaterally. Despite having the ability to legally justify initiating virtually any use of force unilaterally, presidents de facto will not engage in casualty-heavy armed conflict absent the legally binding blessing of lawmakers due to their exposure to this political risk. Presidents often act unilaterally in smaller uses of force, in contrast, not because such interventions contradict the will of Congress, but more often because lawmakers realize they can free-ride off the executive’s unilateral action, forcing the commander-in-chief to act alone. Footnote 2 While unilateral action is frequently interpreted as evidence of presidential dominance and congressional impotence, in the war powers context it is perhaps often better viewed as a manifestation of congressional power: encouraging the president to intervene, yet refusing to go “on the record” and hence avoid responsibility if the use of force ends poorly. Skeptics of congressional influence have noted this dynamic before, but overlooked its larger implication: this is not leading to the “erosion” or “atrophy” of congressional constraint over the use of force, as is frequently alleged. Such behavior, instead, yields constraint: congressional sentiment is not only taken into account by presidents when acting unilaterally, but especially so. As demonstrated by the novel data introduced below, presidents are almost always acting pursuant to Congress’s informal preferences when acting unilaterally.

This work makes two contributions to existing work pushing back against the imperial presidency thesis—one theoretical and one empirical. First, it provides an explanation for formal war powers behavior by way of the introduction of a formal model building off common intuitions and existing scholarship of the incentives found in the strategic setting. Specifically, it concentrates on the blame avoidance incentives widely cited in this context (Ely Reference Ely1995; Schultz Reference Schultz and Drezner2003).Footnote 3 Connecting findings from the American politics literature with work in international crisis bargaining, the model focuses on LRCs: ex post costs levied on a leader by domestic audiences for a use of force that ends poorly. Reasoning out the logic of war powers behavior gives insight into when we should expect uses of force to be undertaken unilaterally versus pursuant to formal authorization, as well as the circumstances under which presidents are most constrained by a lack of formal authorization from Congress.

Second, the article then introduces novel empirical evidence consistent with the substantial congressional constraint on the executive predicted by the model. After showing there is surprisingly little evidence of an actual willingness on the part of presidents to enter full-scale war unilaterally after Truman’s unilateral action in 1950, it introduces new data measuring sentiment in congressional floor speeches in nearly two hundred postwar crises. While previous scholarship utilized rougher proxies of congressional preferences (making the extent of constraint by Congress less clear), these new “Congressional Support Scores” reveal a clear pattern of constraint by the legislature. The data show that even when acting unilaterally in smaller uses of force, presidents have nearly always acted pursuant to informal support in Congress. To the extent presidents actually act in contradiction of the will of Congress, this is limited to isolated strikes and non-combat deployments presenting little risk to American lives.

These findings not only speak to our understanding of unilateral politics, but to other literatures as well. By developing a model that incorporates insights from scholarship on American political institutions into a crisis bargaining framework, it helps realize a vision put forth by scholars decades ago of better connecting the two subfields (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2005), but which so far has seen limited progress. Second, it contributes to the international security literature more broadly by highlighting a cost levied by domestic audiences, but which is distinct from Audience Costs (ACs) (Fearon Reference Fearon1994).Footnote 4 Just as ACs serve a functional role as an incentive-rearranging mechanism,Footnote 5 so too can LRCs serve in a similar incentive-rearranging capacity creating crisis credibility.Footnote 6

This manuscript begins by reviewing the literature on congressional constraint over the use of force, as well as domestic politics and crisis bargaining. It then presents a formal model of the war powers, followed by novel empirical evidence demonstrating the extent of congressional constraint on the executive. It concludes by summarizing its arguments and exploring implications for democracy and policy more broadly.

THE DEBATED IMPERIAL PRESIDENCY

Since at least the Vietnam War, there has existed substantial skepticism that Congress has meaningful influence over the use of military force (Fisher Reference Fisher2013; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1973). It is widely recognized that presidents have strong incentives to accrue unilateral powers (Moe and Howell Reference Moe and Howell1999) and that executives have more discretion over foreign policy than domestic matters (Lowande and Shipan Reference Lowande and Shipan2022; Wildavsky Reference Wildavsky1966). Not only do presidents have more de jure constitutional power in foreign affairs, but they additionally maintain several structural advantages such as greater agenda setting powers, first mover advantages, and informational advantages (Canes-Wrone, Howell, and Lewis Reference Canes-Wrone, Howell and Lewis2008). Electoral incentives make members of Congress less interested in taking the lead in foreign policy (Canes-Wrone, Howell, and Lewis Reference Canes-Wrone, Howell and Lewis2008), and instead encourage lawmakers to simply focus on avoiding blame (Weaver Reference Weaver1986). Likewise, the existence of the standing army after the Second World War and the reluctance of courts to intervene in war powers debates is widely held to facilitate presidential imperialism. From these factors, many leading scholars in law and political science continue to argue congressional influence in crises is, at best, highly limited (Koh Reference Koh2024; Binder, Goldgeier, and Saunders Reference Binder, Goldgeier and Saunders2024).

Nevertheless, some have pushed back against the strongest claims of the imperial presidency over the last two decades. Howell and Pevehouse (Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007) and Kriner (Reference Kriner2010) argue that even when presidents act unilaterally, lawmakers can influence executive decision-making by creating expectations of costs and resistance to be faced in the event military action is undertaken. Howell and Pevehouse, for example, reason that “congressional discussions about an impending military action” signal to the president the reaction they “would likely receive when, and if, military actions did not beget immediate success” (Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007, 23), thereby influencing the intervention decision at the outset. These works did not focus on explaining war powers behavior, however—for example, the question of why so many uses of force were undertaken unilaterally in the first place. A theory of the war powers requires understanding the conditions under which presidents are inclined to seek authorization, the conditions under which Congress is incentivized to grant it, and whether a lack of formal authorization in itself meaningfully constrains the executive.

Subsequent work by skeptics of the imperial presidency has made progress toward understanding these dynamics by demonstrating that formal authorization for the use of military force (an “AUMF”) provides presidents political benefits (Kriner Reference Kriner2014), that Americans dislike unilateral action in general (Reeves and Rogowski Reference Reeves and Rogowski2022), and that “constitutional criticisms” made by lawmakers against a president’s unilateral use of force can meaningfully reduce public support for an operation (Christenson and Kriner Reference Christenson and Kriner2020). But these findings, absent more, leave their own puzzles: if AUMFs provide such important benefits to presidents, why is it so rare for presidents to acquire them?

Similarly, it is unclear from existing work whether a lack of formal authorization from Congress meaningfully constrains presidents. After all, even proponents of the imperial presidency thesis have long recognized that legal authorization empowers presidents (Beschloss Reference Beschloss2018; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1973), highlighting the irony that these “constraints” actually augment presidential power (Irajpanah Reference Irajpanah2024). They often view AUMFs as “blank checks,” and thus as further evidence of congressional impotence (Burns Reference Burns2021; Koh Reference Koh2024). It is often argued that presidents have the option of securing authorization as political insurance, yet still maintain the easy alternative of nevertheless undertaking the use of force unilaterally if securing legislative authorization proves too burdensome. Similarly, presidents might substitute some form of international authorization in lieu of Congress’s approval (Kreps Reference Kreps2019). As one scholar puts it, “presidents have thus not based their decision-making around the assumption that Congress could effectively veto a military proposal” (Griffin Reference Griffin2013, 240).

Indeed, there is seemingly strong evidence presidents are not deterred by lack of approval from Congress: as proponents of the imperial presidency thesis repeatedly emphasize, presidents overwhelmingly use force unilaterally. Skeptics of congressional influence cite a slew of significant combat operations undertaken absent legal authorization from Congress as perhaps their primary piece of evidence of congressional impotence: Panama (1989), Somalia (1992–94), Kosovo (1999), Libya (2011), ISIS (2014), Yemen (2024), and others. Hence, prominent scholars of Congress and American foreign policy continue to argue that “the imperial presidency is alive and well” (Binder, Goldgeier, and Saunders Reference Binder, Goldgeier and Saunders2020) and characterize the modern executive—especially in the war powers context—as the “unconstrained presidency” (Goldgeier and Saunders Reference Goldgeier and Saunders2018). Leading authorities on the war powers continue to portray a virtually unconstrained executive (Burns Reference Burns2019; Fisher Reference Fisher2013; Koh Reference Koh2024; Rudalevige Reference Rudalevige2005). More generally, unilateral action—especially in the realm of war-making and national security—is broadly interpreted as presidential power at its pinnacle.

This work contributes to existing work critiquing the imperial presidency thesis (Christenson and Kriner Reference Christenson and Kriner2020; Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007) by developing a theory of formal war powers behavior that demonstrates how a de facto highly constrained presidency is fully consistent with an abundance of unilateral action. This manuscript builds on scholarship in American political institutions and the domestic politics of foreign policy to formalize the logic of the war powers interaction. It first motivates the assumptions of the theory and then lays out the model formally. Developing such a theory requires, first, understanding the major driver in the “invitation to struggle” between the president and Congress: the political costs of being found responsible for a use of force ending in failure.

LOSS RESPONSIBILITY COSTS

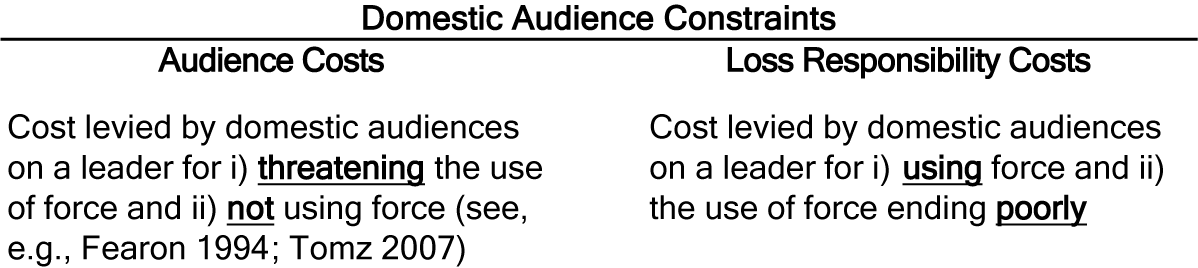

In recent decades, international security scholarship has considered how domestic politics affects conflict behavior. A sizable literature focuses on domestic audience constraints across regime types (Hyde and Saunders Reference Hyde and Saunders2020). Most prominently, “audience costs” were proposed by Fearon as a way domestic political actors might affect international crises (Reference Fearon1994). Subsequent work has debated the microfoundations of ACs and the extent to which such costs exist.Footnote 7 In their original formulation, ACs specifically referred to a cost of (i) escalating a dispute and (ii) then backing down (Fearon Reference Fearon1994; Tomz Reference Tomz2007), but others have pointed out that relevant domestic audience constraints faced by leaders are much broader than this narrow formulation (Gelpi and Grieco Reference Gelpi and Grieco2015; Hyde and Saunders Reference Hyde and Saunders2020).Footnote 8 LRCs here refer to, instead, a cost of (i) using military force, and (ii) the intervention proceeding poorly (Figure 2). ACs and LRCs are distinct, and can even create strong countervailing incentives for leaders (Baum Reference Baum2004).

Although not explicitly named, LRCs are implicitly recognized in the existing literature. Most prominently, an extensive line of work debates the relationship between regime type and leader sensitivity to military defeat. The consistent theme in these works is that loss in armed conflict is politically costly for leaders with domestic audiences (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003; Debs and Goemans Reference Debs and Goemans2010; Reiter and Stam Reference Reiter and Stam2002; Weeks Reference Weeks2014). Moreover, while this literature has focused primarily on variation between states, LRCs can also vary significantly even within the same institutional framework. Croco has highlighted, for example, that perceived culpability affects the punishment imposed by domestic audiences (Croco Reference Croco2011; Croco and Weeks Reference Croco and Weeks2016). Although this scholarship has mostly contemplated the specific sanction of losing office, LRCs can come in other forms and in different magnitudes as well (Gelpi and Grieco Reference Gelpi and Grieco2015; Saunders Reference Saunders2024). Baum, for example, suggests the costs of failure will be a function of the political salience of the use of force (Baum Reference Baum2004), and others have recognized that the scale of uses of force will entail different levels of constraint (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007; Schultz Reference Schultz2017).

Figure 2. Audience Costs vs. Loss Responsibility Costs

Lawmakers and the Imposition of Costs on the Executive

While presidents face relevant domestic audiences beyond Congress, lawmakers play an especially important role in influencing costs imposed on the executive (Christenson and Kriner Reference Christenson and Kriner2020; Gelpi and Grieco Reference Gelpi and Grieco2015; Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007). Members of Congress are able to use hearings, investigations, media appearances, public appeals, and legislative measures to sanction—or threaten to sanction—the presidency (Kriner Reference Kriner2010; Reference Kriner2014; Kriner and Schickler Reference Kriner and Schickler2016).

First, lawmakers have the potential to directly impose costs on the president (Saunders Reference Saunders2024), or otherwise make such costs more likely. In their most blunt and obvious form, Congress could impeach and remove a president for starting a war that ended in disaster. Lawmakers can file lawsuits against the executive branch, attempt to legislate withdrawal from a conflict, or refuse to fund operations (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007). Legislators can create resistance more asymmetrically as well—for example, by threatening to cut-off aid to an ally (a tactic used to force American withdrawal from South Vietnam, for example). More generally, lawmakers can use issue linkage to “upend congressional action on other aspects of the president’s policy agenda” (Howell Reference Howell2013). Gelpi and Grieco (Reference Gelpi and Grieco2015) demonstrate, for example, that presidents who suffer failure in foreign policy have a much more difficult time advancing their legislative agenda in Congress.

Second, lawmakers can indirectly impose costs on the executive by influencing public opinion (Christenson and Kriner Reference Christenson and Kriner2020; Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007; Trager and Vavreck Reference Trager and Vavreck2011). Howell and Pevehouse (Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007), for example, demonstrate that legislators can mold public opinion over potential use of force decisions by shaping media coverage in the build-up to war. In addition to attacks on policy grounds, charges of unconstitutional behavior can also be levied (Kriner Reference Kriner2018). Americans not only dislike unilateral action in general, but are perhaps clearest in their displeasure when it comes to the initiation of military conflict absent congressional approval (Reeves and Rogowski Reference Reeves and Rogowski2022). Because the Constitution clearly endows Congress alone with the power to declare war—and an overwhelming majority of Americans across the political spectrum believe that military operations should only be taken pursuant to formal congressional approval (Christenson and Kriner Reference Christenson and Kriner2020; Kriner Reference Kriner2014)—these attacks can resonate broadly with the American public.

Factors Influencing the President’s Exposure to Loss Responsibility Costs

Two factors, in particular, influence the total exposure to LRCs faced by the executive: (1) the scale of the use of force, and (2) congressional sentiment regarding the potential use of force ex ante.

First, larger uses of force—costing more blood and treasure—are more likely to trigger a broader domestic response. More publicly visible, and hence salient, uses of force will risk greater political fallout (Baum Reference Baum2004). American combat deaths, in particular, will motivate increasing attention and resistance (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007). Leaders of democracies are especially sensitive to casualties, and this is particularly the case after military defeat (Croco Reference Croco2015; Valentino, Huth, and Croco Reference Valentino, Huth and Croco2010). Thus, there is a connection between the scale of force utilized by the executive and the magnitude of political fallout they might anticipate, especially if the operation ends poorly.

Second, informal congressional sentiment toward the use of force will also scale the president’s exposure to these costs. Even when avoiding formal responsibility over use of force decisions, legislators will still often engage in position-taking over potential interventions, just as they do in virtually any other area of public policy, foreign or domestic (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). This informal sentiment in Congress will then have the effect of either augmenting or minimizing the political exposure a president might anticipate.Footnote 9

Congressional sentiment in favor of the use of force, for example, will dampen the political risk faced by the executive. First, if there was widespread support for the intervention at the outset, the executive might reasonably be viewed as less culpable by domestic audiences ex post if a poor outcome is experienced. Second, members of Congress who favored the operation from the beginning will have a more difficult time attacking a president later because those who originally supported an intervention will be subject to charges of hypocrisy and “flip-flopping” (Croco Reference Croco2015). Additionally, vocal congressional support signals to the White House that lawmakers will likely provide resources for the intervention and, at a minimum, do not intend to create obstacles toward the use of force, thus making defeat less likely (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007).Footnote 10 Supportive informal congressional sentiment toward the use of force therefore can lessen the political exposure anticipated by the president. Overwhelming support in Congress for action against ISIS, for example—especially among prominent Republicans such as John McCain—gave the Obama White House cover to use force in 2014, despite the administration’s dubious legal position in the intervention.

In contrast, when congressional sentiment is opposed to an intervention at the outset, presidents are more exposed to LRCs. To begin with, should the intervention result in failure, the executive will be viewed by domestic audiences as particularly culpable for the use of force: the president undertook the operation in the face of opposition from the representatives of the American people. Likewise, having voiced disapproval from the outset, lawmakers will be in the perfect position to highlight their own competence and heighten their own political status by attacking the president should the worst occur. While perhaps still reluctant to directly attack their party leader, even close copartisan political allies of the president may nonetheless omit to defend them. Instead, they might distance themselves from the foreign policy of the White House while still supporting the president on domestic issues. Lastly, strong congressional opposition signals to the president that a poor outcome might be made more likely via the denial of resources needed by the executive or encouraging the adversary (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007). Hence, the political risk facing a president contemplating military action in the face of strong congressional opposition to the use of force will be greater. For example, a year before intervening against ISIS, the Obama White House omitted to intervene in the region during the 2013 Syria “red line” crisis, with many attributing this to the significant political risk it faced acting pursuant to weak support in Congress (Christenson and Kriner Reference Christenson and Kriner2020, 189–91).Footnote 11

An Indispensable Role for Formal Authorization from Congress

However, while presidential exposure to LRCs is thus lower when acting pursuant to congressional support, significant exposure may nevertheless remain absent a more formal commitment from lawmakers. Presidents realize that even when they find backing among lawmakers for an intervention at the outset, combat over the long term—and especially American casualties (Kriner and Shen Reference Kriner and Shen2014)—will put ever-increasing pressure on lawmakers to abandon their prior support. Presidents thus seek commitment, and for this purpose, legally binding authorization from lawmakers is without equal.

First, by having members of Congress publicly affix their name to the operation, it rearranges lawmakers’ own incentives over the long term. Lawmakers who vote to authorize the use of force undertake the most high-profile and public endorsement possible, and thus are the most entrapped by their position later on, even if the intervention sours (Croco Reference Croco2015; Kriner Reference Kriner2014). Now they, too, are responsible for the intervention. Their political fortunes become tied to the success of the operation, and they thus have a vested interest in supporting it over time.Footnote 12 Moreover, the vote makes it more difficult for lawmakers to credibly attack the president for poor judgment in foreign policy, because they themselves voted in favor of the operation. Additionally, securing formal authorization removes virtually all constitutional and legal doubt that the president has the power to undertake the operation: they have received a legally binding AUMF. This eliminates a powerful criticism from the arsenal of opponents, who can no longer claim the president is violating the Constitution (Christenson and Kriner Reference Christenson and Kriner2020; Reeves and Rogowski Reference Reeves and Rogowski2022).

Lyndon Johnson, for example, specifically sought the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution because he believed “only if Congress was in on the takeoff would it take responsibility for any ‘crash landing’ in Vietnam,” (Beschloss Reference Beschloss2018, 506). Similarly, Bush 41 sought formal approval prior to the Gulf War so that if things started to go poorly, lawmakers could not “paint their asses white and run with the antelopes,” (Hess Reference Hess2006, 96). After the 9/11 attacks, the Bush 43 administration sought formal congressional authorization so that “it would be more difficult for Democrats or Republicans to squawk later about President Bush taking action” (Gonzales Reference Gonzales2016, 128–9). Presidents thus seek formal congressional authorization ex ante in order to substantially lessen exposure to LRCs ex post.Footnote 13

MODELING THE WAR POWERS

A president’s anticipated exposure to LRCs, therefore, will be ordered as follows: greatest when acting in the face of congressional opposition, less when acting pursuant to informal support from Congress, and least when acting under the imprimatur of formal authorization from the legislature.

Formally modeling the war powers allows us to clearly lay out our assumptions of the strategic situation, and then work out the decision-making with an eye toward answering the puzzle raised at the outset: why is it that the vast majority of uses of force are undertaken unilaterally, yet at the same time major wars are only undertaken after legally binding authorization has been acquired by the president?

The model here attempts to include all the maladies frequently identified by critics of the war powers status quo, and thus seemingly “stack the deck” against finding congressional influence. Model I considers unilateral action alone, whereas Model II extends the first model by introducing the possibility of formal authorization from Congress.

-

• Unilateral action by the president: We assume that the president possesses the ability to act unilaterally—and, indeed, in this case we make even stronger assumptions of executive discretion than normally taken in the literature. While Howell’s Unilateral Politics Model gives the legislature and the judiciary the opportunity to overturn the policy set by the president (Howell Reference Howell2003, 29), here, we assume that neither Congress nor the courts have any such opportunity.Footnote 14 In this model, the president effectively has unlimited discretion over the policy. In Model I, Congress is not even involved in the decision leading up to the use of military force, whereas in Model II, Congress can be asked for formal authorization prior to actual conflict, but even here the choice of asking for such permission is the president’s alone to make. Moreover, even if the president chooses to seek congressional approval, the executive can still choose to employ as much military force as they see fit regardless of whether Congress approves or rejects the president’s request.

-

• An opportunistic Congress: In Model I, Congress sits on the sidelines and its influence is only felt through the LRCs anticipated by the president. In Model II, we similarly assume that, ceteris paribus, Congress would rather not approve the use of force even if it supports the military intervention from a policy perspective. While the legislature has its own preferences, the best case scenario for lawmakers is when Congress can “have its cake and eat it too”—that is, have its preferred policy enacted without having to actually vote on the deployment. Congress thus seeks to avoid the risk of blame whenever possible (Schultz Reference Schultz and Drezner2003; Weaver Reference Weaver1986).Footnote 15

-

• An absent judiciary: The judiciary has consistently refused to hear cases related to the extent of presidential war initiation authority under a series of non-judiciability doctrines. We thus assume that the 1973 War Powers Resolution is irrelevant, and that legal checks are immaterial.

-

• A “Standing Army”: The model essentially assumes that the president can use any amount of force.

MODEL I: THE UNILATERAL USE OF FORCE

We first construct a simple formal model of crisis bargaining taking account of LRCs.

Sequence of Moves

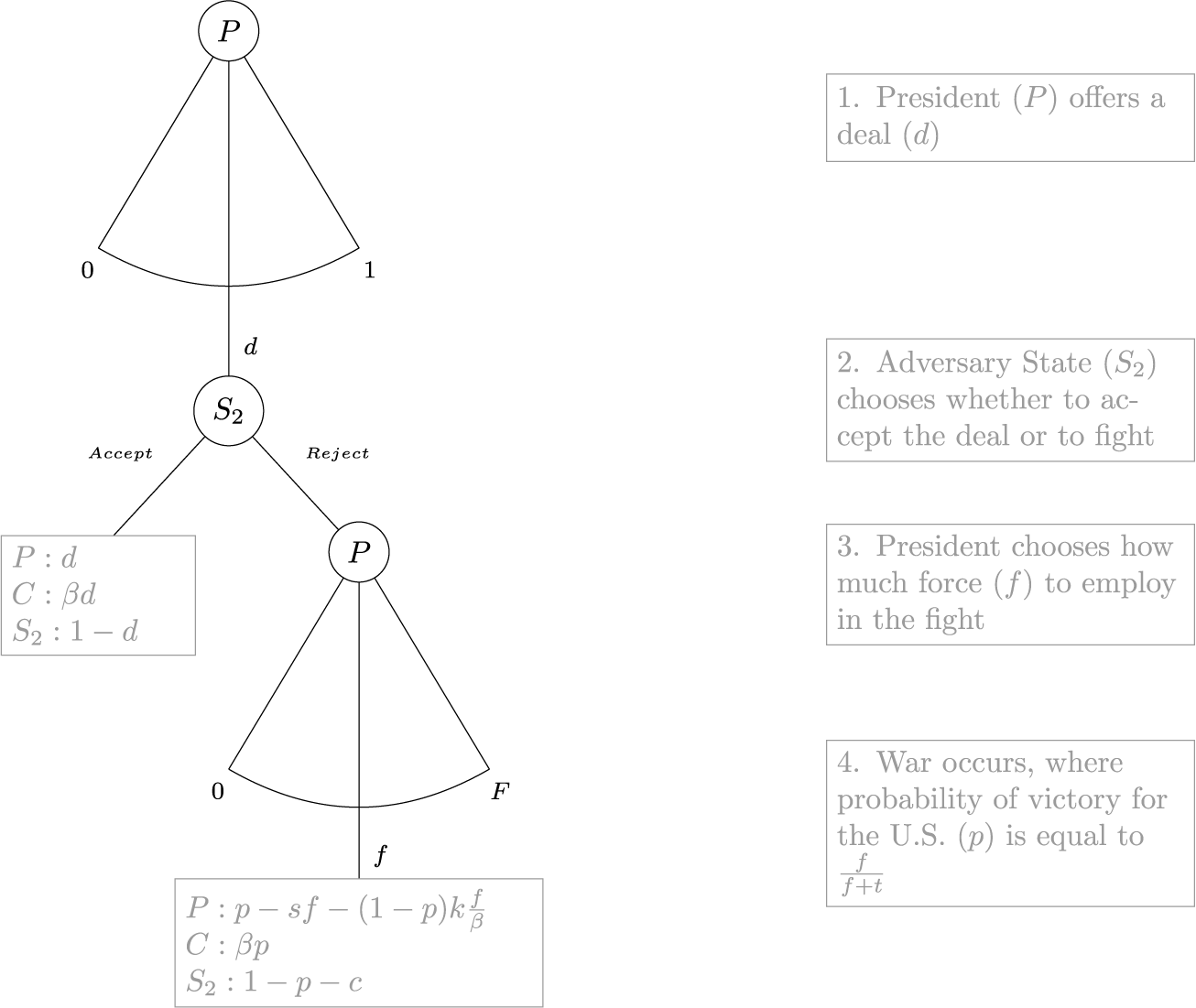

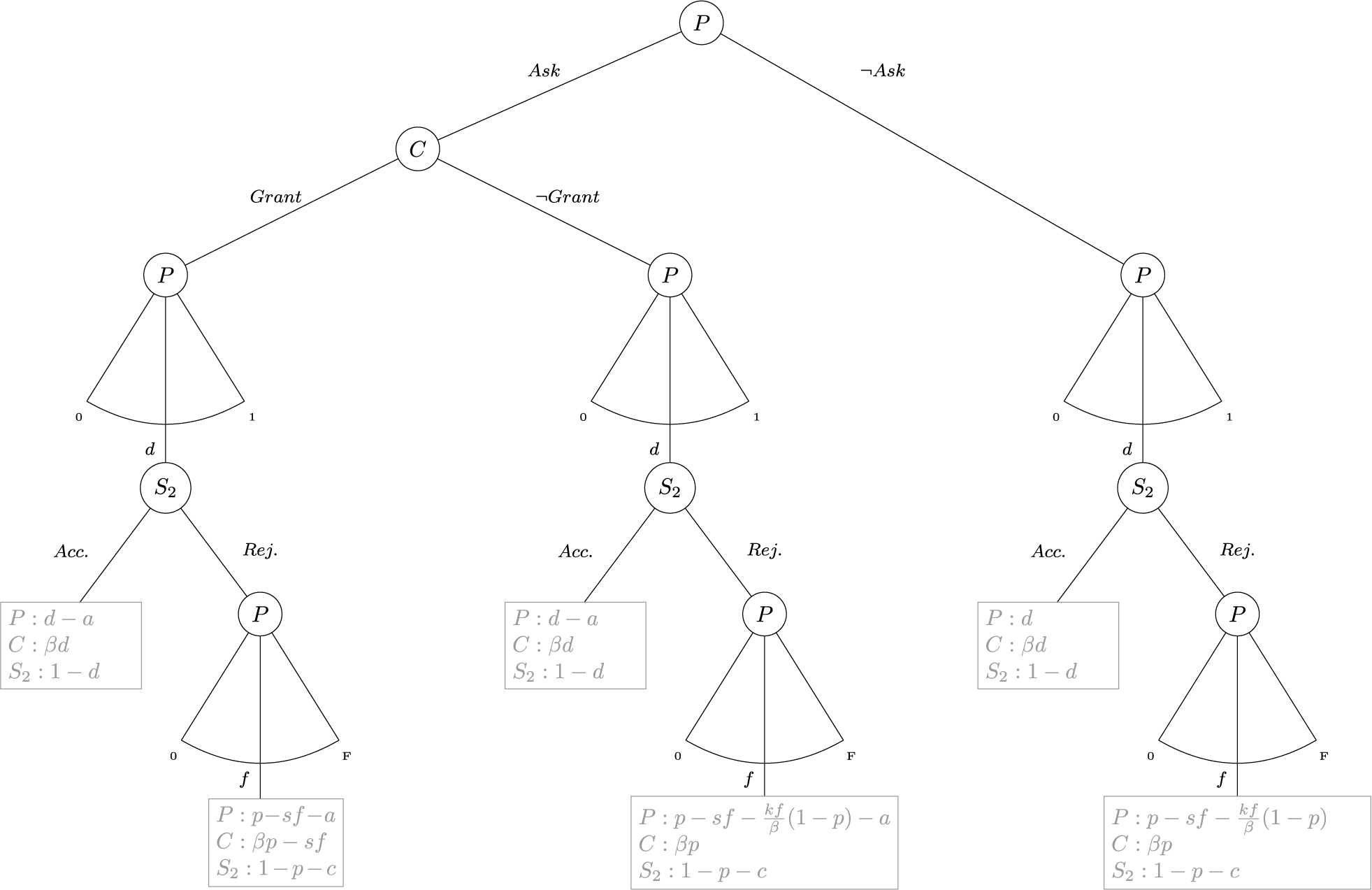

The extensive form of the game is illustrated in Figure 3. Two countries, the US—which is represented by the president (P)—and an adversary state (S

2) compete over an issue space equal to 1. P begins the interaction by proposing a deal (d, where

![]() $ 0\le d\le 1 $

) to

$ 0\le d\le 1 $

) to

![]() $ {S}_2 $

for the division of the good. After viewing P’s proposed deal, d,

$ {S}_2 $

for the division of the good. After viewing P’s proposed deal, d,

![]() $ {S}_2 $

then decides whether to accept the deal or to reject it and go to war. If

$ {S}_2 $

then decides whether to accept the deal or to reject it and go to war. If

![]() $ {S}_2 $

rejects the deal, the president selects an amount of force (f, where

$ {S}_2 $

rejects the deal, the president selects an amount of force (f, where

![]() $ 0\le f\le F $

) to employ and war occurs. The probability of victory for the US will be a function of the amount of force the president chooses to employ (f) and the power of the adversary (t), using the common contest function

$ 0\le f\le F $

) to employ and war occurs. The probability of victory for the US will be a function of the amount of force the president chooses to employ (f) and the power of the adversary (t), using the common contest function

![]() $ p=\frac{f}{f+t} $

. After conflict occurs, the president faces LRCs if the US is unsuccessful in the conflict.

$ p=\frac{f}{f+t} $

. After conflict occurs, the president faces LRCs if the US is unsuccessful in the conflict.

Figure 3. Bargaining Model with Loss Responsibility Costs

Payoffs

The president (P) and the Adversary State (

![]() $ {S}_2 $

) both value the object bargained over at a normalized value of 1. Congress’s (C) value of the object—that is, informal congressional sentiment—in contrast, is given by an exogenous parameter,

$ {S}_2 $

) both value the object bargained over at a normalized value of 1. Congress’s (C) value of the object—that is, informal congressional sentiment—in contrast, is given by an exogenous parameter,

![]() $ \beta $

. We assume β > 0.Footnote 16

$ \beta $

. We assume β > 0.Footnote 16

If

![]() $ {S}_2 $

accepts the deal offered (d), the game ends peacefully with the president thus receiving a payoff of d, Congress receiving βd, and

$ {S}_2 $

accepts the deal offered (d), the game ends peacefully with the president thus receiving a payoff of d, Congress receiving βd, and

![]() $ {S}_2 $

receiving 1−d. If, instead, the deal is rejected and conflict occurs, the payoffs of the actors will involve the following components:

$ {S}_2 $

receiving 1−d. If, instead, the deal is rejected and conflict occurs, the payoffs of the actors will involve the following components:

-

• Value of object: The value of the object being fought over, as described above, is normalized to 1 for the president and the Adversary State, while Congress values it at

$ \beta $

.

$ \beta $

. -

• The cost of fighting: Because the president selects how much force (f) to employ, the projected cost of fighting for the president is proportional to the force utilized. A cost sensitivity parameter—s—is multiplied by the amount of force used (f) to yield the president’s costs of fighting:

$ sf $

.Footnote 17 While the president has thus internalized the cost of fighting, we assume that Congress has not done so, since it has not formally authorized the use of force. Lastly,

$ sf $

.Footnote 17 While the president has thus internalized the cost of fighting, we assume that Congress has not done so, since it has not formally authorized the use of force. Lastly,

$ {S}_2 $

maintains the standard cost of fighting parameter, c.

$ {S}_2 $

maintains the standard cost of fighting parameter, c. -

• “Loss Responsibility Costs”: Here, we assume the president suffers this cost if the conflict ends in failure. The size of this potential penalty will be equal to

where f is the amount of force utilized, $$ \begin{array}{rll}k\frac{f}{\beta },& & \end{array} $$

$$ \begin{array}{rll}k\frac{f}{\beta },& & \end{array} $$

$ \beta $

is congressional sentiment, and k is a scaling parameter. As discussed above, the potential penalty will be directly proportional to the amount of force employed and inversely proportional to congressional sentiment—more support for the use of force will give a president more political cover while greater opposition will increase the risk they face. Thus, f is in the numerator and

$ \beta $

is congressional sentiment, and k is a scaling parameter. As discussed above, the potential penalty will be directly proportional to the amount of force employed and inversely proportional to congressional sentiment—more support for the use of force will give a president more political cover while greater opposition will increase the risk they face. Thus, f is in the numerator and

$ \beta $

is in the denominator.

$ \beta $

is in the denominator.

Assuming a deal has been rejected and conflict occurs, each actor will pay its cost of fighting. If the US is victorious, the president and the Congress will additionally receive their values for the object, while

![]() $ {S}_2 $

will receive 0. In contrast, if the US is defeated, the president and Congress will receive no utility from the object, while

$ {S}_2 $

will receive 0. In contrast, if the US is defeated, the president and Congress will receive no utility from the object, while

![]() $ {S}_2 $

will receive its value. Lastly, the possible LRC will be factored into the president’s payoff. Altogether, the president’s utility function will thus be

$ {S}_2 $

will receive its value. Lastly, the possible LRC will be factored into the president’s payoff. Altogether, the president’s utility function will thus be

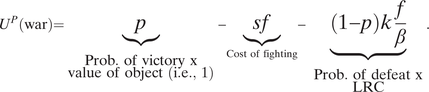

$$ \begin{array}{c}{U}^P(\mathrm{war})=\underset{\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{Prob}.\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{victory}\ \mathrm{x}\\ {}\mathrm{value}\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{object}\ (\mathrm{i}.\mathrm{e}.,\ 1)\end{array}}{\underbrace{p}}-\underset{\mathrm{Cost}\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{fighting}}{\underbrace{sf}}-\hskip2px \underset{\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{Prob}.\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{defeat}\ \mathrm{x}\\ {}\mathrm{LRC}\end{array}}{\underbrace{\left(1-p\right)k\frac{f}{\beta }}}.\end{array} $$

$$ \begin{array}{c}{U}^P(\mathrm{war})=\underset{\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{Prob}.\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{victory}\ \mathrm{x}\\ {}\mathrm{value}\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{object}\ (\mathrm{i}.\mathrm{e}.,\ 1)\end{array}}{\underbrace{p}}-\underset{\mathrm{Cost}\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{fighting}}{\underbrace{sf}}-\hskip2px \underset{\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{Prob}.\ \mathrm{of}\ \mathrm{defeat}\ \mathrm{x}\\ {}\mathrm{LRC}\end{array}}{\underbrace{\left(1-p\right)k\frac{f}{\beta }}}.\end{array} $$

Solution and Results

Assuming perfect and complete information, the game is solved simply utilizing backward induction. The step-by-step solution is provided in Appendix I of the Supplementary Material, but will be briefly outlined here.

Looking at Figure 3, we start with the president’s decision over how much force to employ. The president has two competing incentives: on the one hand, more force utilized entails a greater chance of victory. On the other hand, more force utilized entails more fighting costs and greater LRC to be suffered upon defeat. The president will then select the amount of force that maximizes their expected utility based on these constraints.

Knowing the amount of force the president will choose to employ—which then affects the probability of victory in the contest—the Adversary State will be able to calculate its expected payoff from war. Knowing

![]() $ {S}_2 $

is making this calculation, the president will calibrate the deal to maximize their own “slice of the pie” (d), while avoiding conflict. The president will offer a deal that makes

$ {S}_2 $

is making this calculation, the president will calibrate the deal to maximize their own “slice of the pie” (d), while avoiding conflict. The president will offer a deal that makes

![]() $ {S}_2 $

indifferent between accepting the deal and going to war, and

$ {S}_2 $

indifferent between accepting the deal and going to war, and

![]() $ {S}_2 $

will accept the offer. Because there is perfect and complete information, there is no actual risk of war. Nonetheless, the model effectively illustrates how LRCs influence both the amount of force the president would be willing to utilize and the outcomes of crises.

$ {S}_2 $

will accept the offer. Because there is perfect and complete information, there is no actual risk of war. Nonetheless, the model effectively illustrates how LRCs influence both the amount of force the president would be willing to utilize and the outcomes of crises.

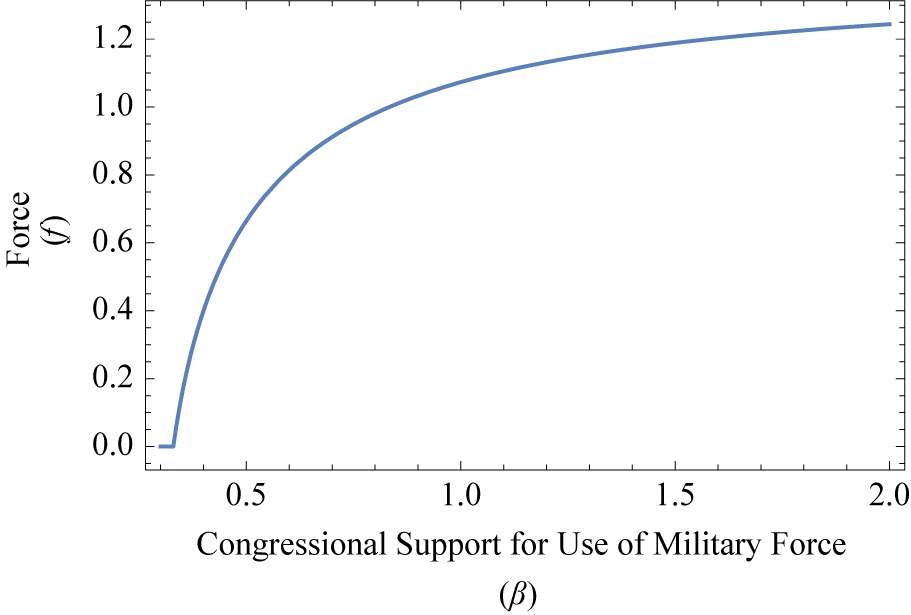

Plotted in Figure 4 is the amount of force,

![]() $ {f}^{*} $

, the president will employ as a function of congressional sentiment toward the use of force (

$ {f}^{*} $

, the president will employ as a function of congressional sentiment toward the use of force (

![]() $ \beta $

).Footnote 18 As the plot shows, f and

$ \beta $

).Footnote 18 As the plot shows, f and

![]() $ \beta $

exhibit a positive relationship. This implies that as congressional sentiment increasingly supports the use of force, the amount of force a president would be willing to employ correspondingly increases. Conversely, increasing congressional opposition to the use of force (decreasing

$ \beta $

exhibit a positive relationship. This implies that as congressional sentiment increasingly supports the use of force, the amount of force a president would be willing to employ correspondingly increases. Conversely, increasing congressional opposition to the use of force (decreasing

![]() $ \beta $

) leads to more constraint on the president. Note that this is consistent with existing informal work arguing that expressions of support or opposition in Congress will incentivize presidents to use more or less force in a crisis (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007, 114).

$ \beta $

) leads to more constraint on the president. Note that this is consistent with existing informal work arguing that expressions of support or opposition in Congress will incentivize presidents to use more or less force in a crisis (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2007, 114).

Figure 4. U.S. Force Threatened as a Function of Congressional Sentiment

This simple comparative static result has an important implication: because congressional sentiment, by way of the LRC mechanism, is influencing the maximum amount of force a president might be willing to employ, congressional sentiment is constraining the decision of the president even when the president is acting unilaterally.

Hypothesis 1. Necessary condition in degree—Sentiment in Congress toward the use of force serves as a constraint on the maximum scale of force presidents utilize.

Indeed, congressional sentiment is counterintuitively more influential when the president acts alone, because here they are the most exposed to LRCs. None other than J. William Fulbright, the celebrated chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, repeatedly made this exact point throughout his career. When acting unilaterally, the president would be acting “entirely on his own responsibility” and thus “would hesitate to take action that he did not feel confident he could defend to the Congress. He would remain accountable to Congress for his action to a greater extent than he would if he had specific authorizing language to fall back upon.”Footnote 19 Hence, the point is not simply that presidents are constrained by LRCs despite acting unilaterally; it is that presidents are substantially constrained by LRCs because they are acting unilaterally. To paraphrase Schlesinger, they are acting at their own peril (Reference Schlesinger1973, 162).

Note, moreover, that the hypothesis is framed as a necessary condition in degree: there is a limit to how much force a president will utilize as a function of congressional sentiment. It is not simply suggesting a positive correlation between congressional support and the amount of force utilized—instead, it is suggesting a ceiling line (Dul Reference Dul2016; Goertz, Hak, and Dul Reference Goertz, Hak and Dul2013). Crises are fundamentally bargaining situations (Schelling Reference Schelling1960); because war is ex post inefficient (Fearon Reference Fearon1995), there are strong incentives for actors to reach a deal short of combat, or at a lower level of combat than otherwise might be tolerated. Thus, it would be unsurprising if we observed a president employ less force than they (or Congress) would have tolerated, given that there should almost always be Pareto superior deals to fighting.

MODEL II: ALLOWING FOR FORMAL CONGRESSIONAL AUTHORIZATION

We now introduce the possibility of formal authorization from the legislature—a legally binding AUMF—into the game. For the sake of simplicity, we assume that securing formal authorization ex ante removes the possibility of LRCs ex post (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Bargaining Model with Loss Responsibility Costs and Possibility of Formal Authorization from Congress

Sequence of Moves

First, the president (P) decides whether to ask Congress (C) for formal authorization to use military force. The president, as is well recognized, always has the option of simply bypassing Congress entirely. If they do so, the actors will then be in a subgame identical to the “unilateral” game analyzed in the section above. Indeed, there are substantial incentives to act unilaterally because seeking approval is not cost-free. Instead, asking for formal authorization entails a cost, a. Footnote 20 The benefit of securing such approval is substantial, however, as it eliminates the president’s exposure to LRCs.

If the president chooses to seek formal congressional approval, C then decides whether to grant such authorization. By granting authorization, however, C is forced to put some “skin in the game.” As explained above, the president will always internalize a sensitivity to casualties (

![]() $ sf $

) regardless of whether the use of force is authorized. Now, if Congress formally approves the use of force, it too is penalized for higher casualty counts and is subject to that as a cost of fighting (

$ sf $

) regardless of whether the use of force is authorized. Now, if Congress formally approves the use of force, it too is penalized for higher casualty counts and is subject to that as a cost of fighting (

![]() $ sf $

). Thereafter—regardless of whether P asked for authorization, and, if so, whether C granted such authorization—the same bargaining game explained in the section above occurs.

$ sf $

). Thereafter—regardless of whether P asked for authorization, and, if so, whether C granted such authorization—the same bargaining game explained in the section above occurs.

Payoffs

The payoffs of each player are most easily described in comparison to those found in the “unilateral” game (Model I). First, if the president simply chooses not to ask (

![]() $ \neg Ask $

) Congress and act unilaterally (the subgame on the right), the payoffs are precisely the same as those found in Model I. Second, consider what happens if the president seeks approval but is rejected by the legislature (the middle subgame). Here, all the payoffs are precisely the same as those in Model I, except for the additional cost of asking, a, paid by the president.

$ \neg Ask $

) Congress and act unilaterally (the subgame on the right), the payoffs are precisely the same as those found in Model I. Second, consider what happens if the president seeks approval but is rejected by the legislature (the middle subgame). Here, all the payoffs are precisely the same as those in Model I, except for the additional cost of asking, a, paid by the president.

Lastly, consider the situation in which the president has sought formal approval and Congress has granted it (the subgame on the left). Payoffs here differ from the original “unilateral” game in the following ways: first, the president pays the cost a of asking. Second, the exposure to LRCs has been eliminated. Because of this, the entire LRCs term has been removed from the president’s payoff when fighting with the formal approval of Congress. Lastly, as alluded to above, Congress now also suffers a cost of fighting (

![]() $ sf $

) if force is actually used after legislative authorization is given. Because in this case Congress has formally affixed its approval to the operation, Congress can no longer metaphorically “wash its hands” of the conflict and “sit on the sidelines.”

$ sf $

) if force is actually used after legislative authorization is given. Because in this case Congress has formally affixed its approval to the operation, Congress can no longer metaphorically “wash its hands” of the conflict and “sit on the sidelines.”

Perfect and Complete Information: Solution and Results

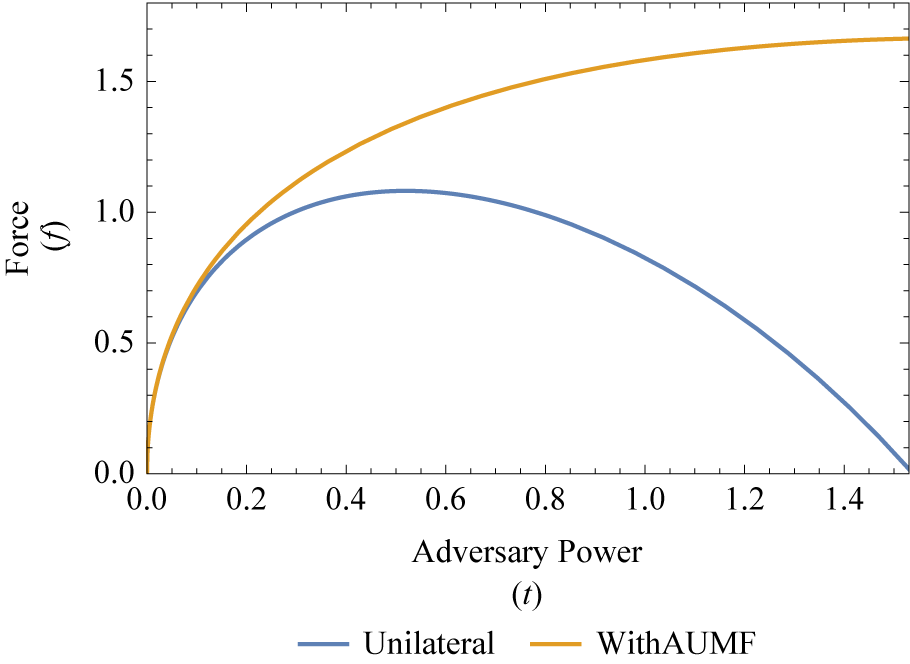

First, we assume a situation in which information is perfect and complete. As with the “unilateral” model, the step-by-step solution for the game is included in Appendix I of the Supplementary Material. The most important result is that the president is willing to utilize more force when acting pursuant to formal authorization than when acting unilaterally. The intuition here is straightforward: from the previous model, we saw that increasing LRCs incentivized presidents to “pull their punches,” or perhaps not intervene at all. When acting pursuant to an AUMF, however, presidents no longer have to worry about LRCs and thus are willing to utilize more force. The president no longer has political exposure; they have political cover.

The plot in Figure 6 shows the amount of force a president will be willing to use at different levels of adversary power.Footnote 21 The orange curve represents a president operating under an AUMF, while the blue line signifies one operating unilaterally. Notice that when the adversary is very weak, there is little meaningful difference between the two. In this case, the executive is quite certain the US will prevail (given the massive power imbalance) and can use relatively little force to achieve a high chance of victory. In this case, LRCs are quite small, and the executive has few qualms about unilateral action.

Figure 6. Force Employed as a Function of Adversary Power (t), Comparing Unilateral Action and with AUMF

A different story unfolds, however, as adversary power grows. As the president faces stronger adversaries, they will begin “pulling their punches”: increasing force risks higher LRCs, and the adversary’s power makes defeat a substantial possibility. Eventually, the executive will be so deterred from unilateral action that they simply will not intervene. Acting pursuant to formal approval from the legislature, however, provides substantial political cover to the executive and incentivizes them to utilize more force. This credible threat of more force, in turn, then improves the bargaining leverage of the US.Footnote 22

The second main takeaway from the model is that with complete information—and thus, in this model, no actual chance of war—Congress will always grant authorization for the use of force. The simple intuition here is that because there is zero probability of war, and because Congress is only hurt by authorizing the use of force if war actually occurs, Congress knows it will never actually have to suffer the possible consequences of authorizing the use of force. It is therefore always optimal to give the president the extra bargaining leverage formal approval creates because—in this version of the model—there is no downside to doing so.Footnote 23

Model with Incomplete Information over Adversary’s Cost of Fighting

We now introduce asymmetric information here to create a real risk of war, and to see how this then affects Congress and the president’s behavior with regard to formal authorization. We assume that the US does not know the adversary state’s cost of war, c, with certainty. The distribution of types for

![]() $ {S}_2 $

is continuous and uniform over the interval

$ {S}_2 $

is continuous and uniform over the interval

![]() $ c\in [0,\overline{c}] $

, where

$ c\in [0,\overline{c}] $

, where

![]() $ 0<\overline{c} $

and where c is drawn randomly by nature (N). S

2, in contrast, is perfectly and completely informed of Congress and the president’s actions and payoffs. This incomplete information version of the game is solved using the Bayesian Perfect Equilibrium solution concept. The full solution to the game is provided in Appendix I of the Supplementary Material.

$ 0<\overline{c} $

and where c is drawn randomly by nature (N). S

2, in contrast, is perfectly and completely informed of Congress and the president’s actions and payoffs. This incomplete information version of the game is solved using the Bayesian Perfect Equilibrium solution concept. The full solution to the game is provided in Appendix I of the Supplementary Material.

Discussion

Unlike in the complete information version of the game, here there is a positive probability of war under certain parameters. Because of this, Congress does not always grant authorization, as it now faces the possibility of having to share responsibility in an actual armed conflict. This creates a risk-reward trade-off for legislators, giving even informally supportive legislators second thoughts before going formally on the record in support of military action. While formally authorizing the use of force might lead to better outcomes for the US—a better bargain and, under certain parameters, even a decreased probability of conflict—lawmakers undertake a sizable downside risk should war actually occur.Footnote 24

Moreover, because Congress does not always grant authorization, the president does not always seek it. Indeed, in equilibrium, the president will only seek authorization when Congress will grant it. Thus, when commentators note that it is uncommon for Congress to reject a presidential request for authorization—often suggesting Congress simply “rubber stamps” these requests whenever made—this needs to be put into context. Because seeking authorization is costly, and because the president faces the exact same unilateral use of force option regardless if they go to Congress and are rejected or simply bypass Congress altogether, it is better to simply sidestep Congress and thus avoid the cost of asking. In other words, the White House is only incentivized to seek authorization when it anticipates that such a request will be approved.Footnote 25 Hence, the very high overall success rate of presidential requests for formal authorization (Lindsay Reference Lindsay2013) can be explained not by Congress simply granting whatever the president wants (the conventional wisdom), but by the White House strategically anticipating the reaction of lawmakers. A good analogy for this dynamic is veto bargaining (Cameron Reference Cameron2000), but with the roles simply reversed. The president will only propose an AUMF they think will pass and consciously avoid going to Congress otherwise. Moreover, as we will see below, Congress has strong incentives to avoid authorizing the use of force whenever possible. Together, this means that we will often have situations in which Congress clearly supports the use of force, and the president realizes they would benefit substantially from authorization (Kriner Reference Kriner2014), but the president is forced to act unilaterally because they realize lawmakers are not about to go “on the record” in favor of the intervention. Congress free-rides off the president; the legislature takes advantage of the president’s ability to act unilaterally.

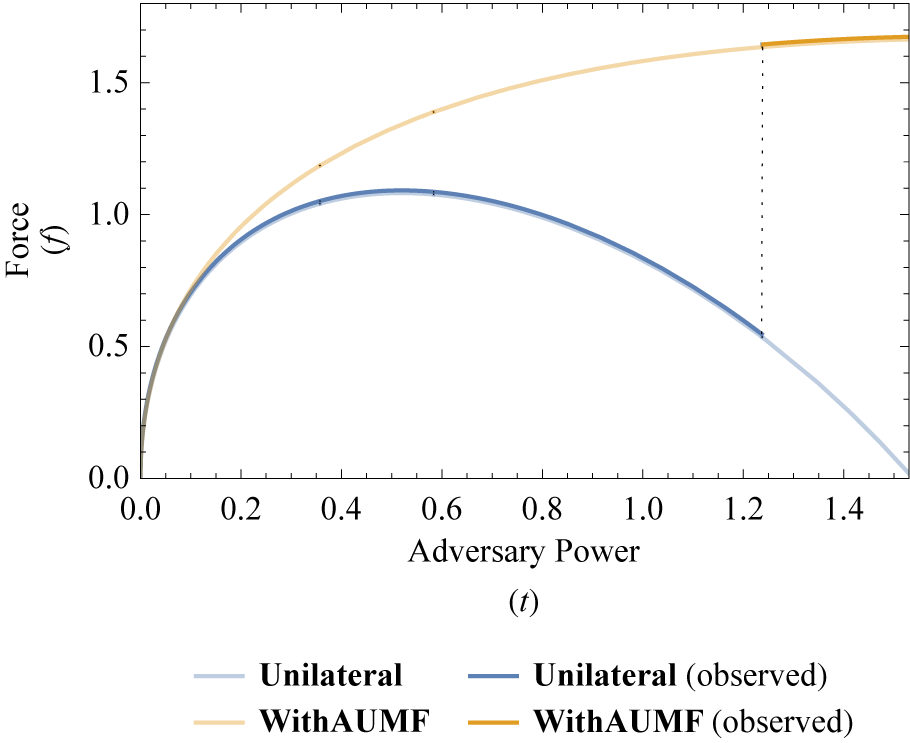

Moreover, this does not imply presidents will simply proceed to undertake the same action absent formal authorization from Congress as they would with lawmakers’ legal blessing. Instead, as the size of the threat increases, the force level employed by a president unilaterally versus under the cover of formal authorization becomes increasingly divergent. The plot illustrated in Figure 7 depicts the equilibrium amount of force employed (or—if war does not occur—the amount of force credibly threatened to be employed) as a function of adversary power (t).Footnote 26 Note that this is the same plot as that presented in Figure 6, but now additionally highlights the authorization status we will observe in equilibrium. Against weaker adversaries, the president is quite willing to act alone, and the blue line barely diverges from the orange line: essentially, the same amount of force would have been used regardless of authorization status. As the size of the threat increases, however, the increasing exposure to LRCs incentivizes the president to “underdeploy.” Indeed, around

![]() $ t=0.5 $

, unilateral force reaches its maximum. Thereafter, increasingly less force is deployed even as the size of the threat increases, and eventually

$ t=0.5 $

, unilateral force reaches its maximum. Thereafter, increasingly less force is deployed even as the size of the threat increases, and eventually

![]() $ {f}^{*}=0 $

: the US simply does not enter the contest. This implies that the largest uses of force—that is, full scale wars—will be undertaken pursuant to formal authorization from Congress, or not at all. Undertaking such a major conflict unilaterally simply leaves a president far too exposed politically, thus deterring it from occurring. The burden is too heavy for the president alone to bear.

$ {f}^{*}=0 $

: the US simply does not enter the contest. This implies that the largest uses of force—that is, full scale wars—will be undertaken pursuant to formal authorization from Congress, or not at all. Undertaking such a major conflict unilaterally simply leaves a president far too exposed politically, thus deterring it from occurring. The burden is too heavy for the president alone to bear.

Hypothesis 2a. Necessary Condition in Kind—The largest uses of force (full scale wars) will only be undertaken pursuant to formal authorization from Congress.

Figure 7. U.S. Force Employed (or, Credibly Threatened) and Authorization Status Observed in Equilibrium as a Function of Adversary Power

Lastly, we consider when we will observe a president act unilaterally and when we will see action undertaken pursuant to congressional authorization. Observe that the darkened portions of the curves in Figure 7 represent the actual amount of force (and authorization status) we will observe in equilibrium after the decisions by the president and Congress over formal authorization have been made. Here, Congress’s reluctance to formally approve uses of force is the primary driver of the behavior.Footnote 27

Smaller threats are undertaken unilaterally by the president, so the blue line is darkened up to a certain threshold threat level (on this plot, around

![]() $ t=1.23 $

). At this point, however, Congress becomes willing to formally authorize the intervention, and the use of force, instead, occurs pursuant to formal approval: presidents will act unilaterally against smaller threats, and pursuant to formal congressional approval for larger threats.

$ t=1.23 $

). At this point, however, Congress becomes willing to formally authorize the intervention, and the use of force, instead, occurs pursuant to formal approval: presidents will act unilaterally against smaller threats, and pursuant to formal congressional approval for larger threats.

The intuition behind this is as simple: because lawmakers are driven primarily by blame avoidance in the use of force context, Congress seeks to avoid going “on the record” on use of force decisions as much as possible. The only time they are incentivized to formally approve the use of force is when they receive some significant offsetting gain that overcomes the downside risk they undertake. When Congress’s vote makes a vast difference (which, as we see from Figure 7, it does when the largest threats and largest uses of force are contemplated), here we see the possibility that lawmakers calculate they care enough about a foreign policy objective to “pony up” and “put their money where their mouths are” and formally authorize the use of force.Footnote 28 The president’s de facto inability to bear this heavy burden alone forces Congress to make a consequential decision.

In contrast, if presidents are simply going to undertake a similar use of force regardless of what Congress does (as we see is the case in Figure 7 against smaller threats for smaller uses of force) lawmakers have no incentive to put their necks on the line: even when otherwise informally supporting the use of force, Congress strategically avoids a vote. In a way, Congress uses the president’s ability to act unilaterally against them. Lawmakers know that the great expectations put on the American executive will force them to act unilaterally, and thus lawmakers can free-ride off of this.

Altogether, this then explains the pattern we observe after the Korean War: full-scale wars are only undertaken pursuant to formal authorization, while smaller uses of force are consistently undertaken unilaterally—and this is the case even when Congress overwhelmingly supports the intervention informally.

Hypothesis 2b. Smaller uses of force will be undertaken unilaterally (even when Congress informally supports the use of force).Footnote 29

Moreover, this implies that a lack of formal congressional authorization is not evidence of a lack of informal congressional support. While many commentators simply assume unilateral uses of force reflect an executive reaching beyond the wishes of Congress, these interventions undertaken absent formal congressional approval could just as easily reflect Congress’s preference: permitting, perhaps even pressuring, the White House to take action and yet also assume the full political cost in case of disaster. In this way, Congress gets to have its cake and eat it too. Model I, after all, showed that presidents would be highly exposed to LRCs when acting unilaterally, incentivizing them to not stray far beyond what informal congressional sentiment supports. Unilateral action, thus, is not symptomatic of an “erosion” or “atrophy” of congressional influence; it is often a manifestation of it.

EMPIRICAL ASSESSMENT

The hypotheses yielded above suggest two necessary conditions when it comes to Congress and the use of force. The first focuses on informal congressional sentiment: informal sentiment among lawmakers will serve as a necessary condition in degree for all crises (Hypothesis 1). In other words, the number of casualties a White House is willing to sustain is limited by informal sentiment on the Hill. The second focuses on the formal authorization status of interventions: while smaller uses of force are undertaken unilaterally (Hypothesis 2b), a formal AUMF serves as a necessary condition for the largest uses of force (Hypothesis 2a). Altogether, the hypotheses suggest the following: the largest uses of force will only be undertaken with formal authorization from Congress, while even smaller unilateral uses of force will see a president substantially constrained by informal congressional sentiment.

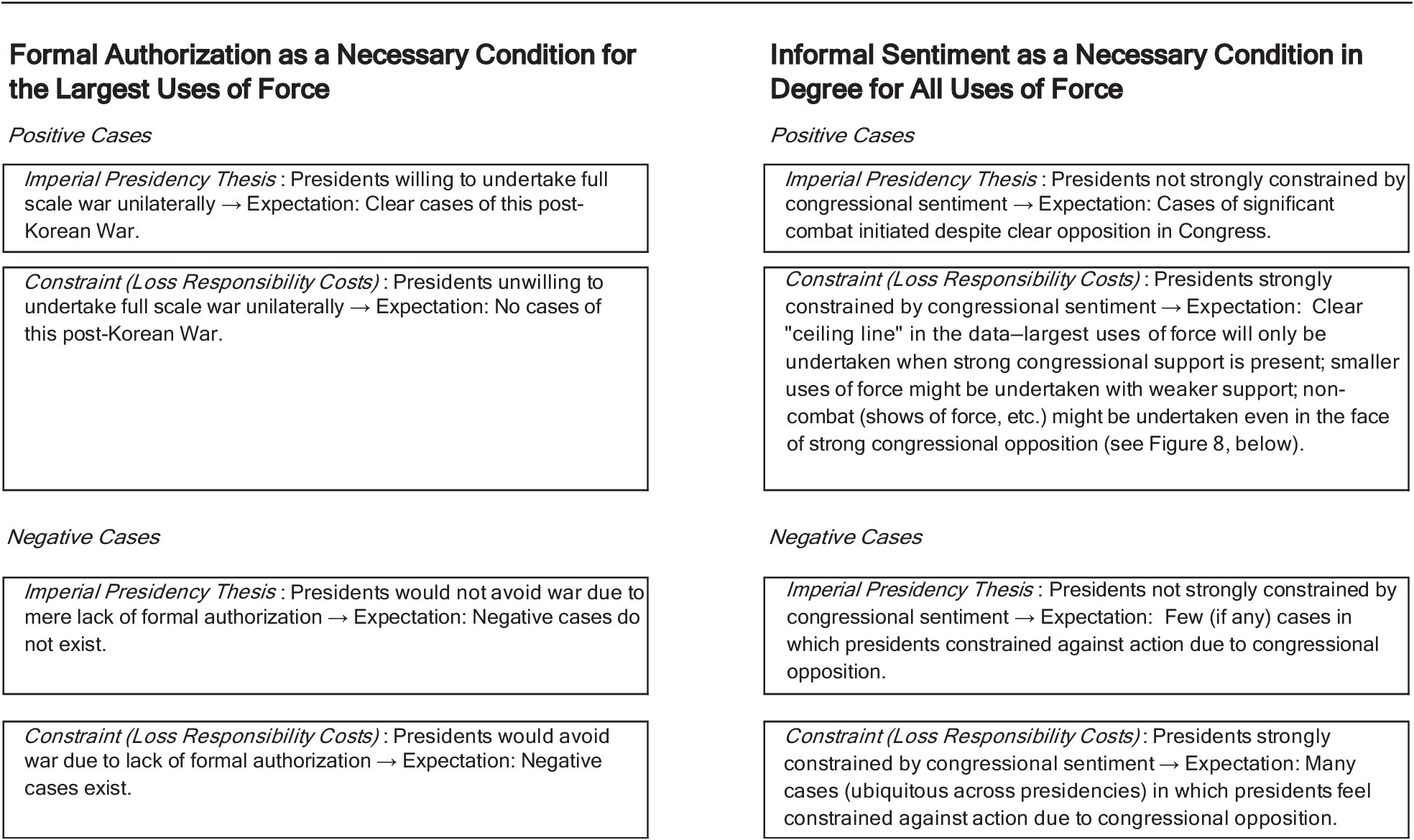

Constraint theories imply two kinds of observable implications, which will be referred to here as “positive” and “negative” cases.Footnote 30 First, when we actually observe the outcome (i.e., a “positive” case), we expect the necessary condition to be present. Here, the theory suggests we will only observe a use of force of a certain magnitude when there exists a requisite level of support in Congress. Hence, we seek to identify instances in which force was used, and ask whether this was the case. Second, we would also expect to find cases in which the absence of the condition prevented the outcome from occurring (i.e., “negative” cases). Hence, we ask whether we can identify cases in which the outcome (the use of force) was prevented by the lack of the necessary condition (a requisite level of support expressed by Congress). Table 1 summarizes these observable implications and contrasts them with those implied by the imperial presidency thesis. Each is discussed further in the analysis below.

Table 1. Observable Implications—Imperial Presidency Thesis vs. Constraint (Loss Responsibility Costs)

Formal Authorization as a Necessary Condition for the Largest Uses of Force

A typical telling of war powers history recounts that Truman entered the Korean War absent formal authorization from Congress, and that this precedent of unilateral action then led to a vast expansion of presidential war power (e.g., Fisher Reference Fisher2013; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1973). Political scientists have assumed that a lack of formal authorization serves little constraining role on the executive in the postwar era, while legal scholars—paying close attention to what presidents and their lawyers say—consistently bemoan that presidents have “not based their decision-making around the assumption that Congress could effectively veto a military proposal” (Griffin Reference Griffin2013, 240).

But while many scholars of the war powers cite the Korean War as the watershed precedent opening a floodgate of unilateral action in the postwar era, Figure 1 showed strikingly little evidence of this. Instead, if anything, the Korean intervention appears more like antiprecedent: every major war undertaken after 1953 occurred pursuant to formal authorization from Congress. While there were, indeed, many unilateral uses of force undertaken after the Korean War, these were all several orders of magnitude smaller in scale than the Korean conflict. The most casualty-intensive uses of force undertaken unilaterally after the Korean War were interventions in Panama and Somalia, with fewer than 25 American combat deaths (compared to the 30,000 suffered in the Korean conflict).

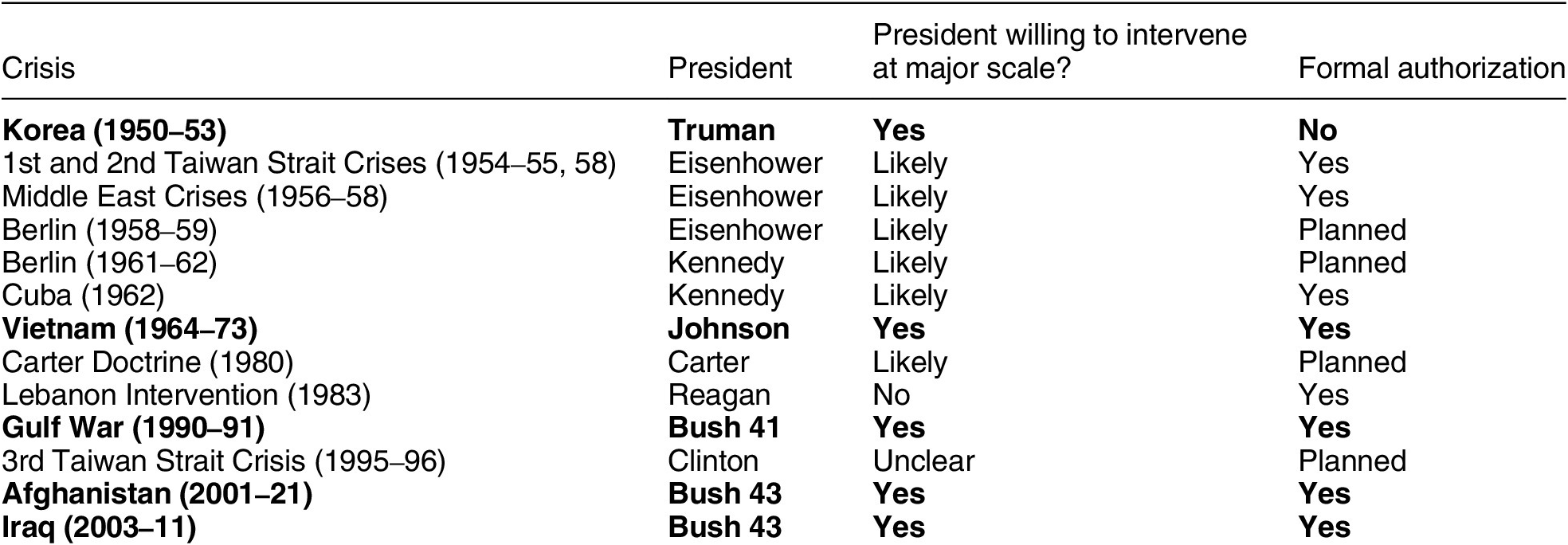

Positive Cases

Politicians took a clear lesson away from Truman’s “police action” in the Korean War: by not having members of Congress formally authorize the use of force ex ante, the president left himself highly exposed ex post. Instead, formal authorization has been privately perceived as a de facto necessary condition for the largest uses of force since 1953.Footnote 31 Again, such an analysis involves considering both “positive” and “negative” cases. Positive cases include those in which we have substantial evidence a president was willing to sustain casualties on the order of a full-scale warFootnote 32—either because they actually did so (e.g., the Vietnam or Iraq Wars) or because they appeared willing to do so but the adversary backed down (e.g., the Cuban Missile Crisis or the First Taiwan Strait Crisis). What one finds is that in each of these cases, presidents either acquired, or expected to soon receive, formal authorization for the use of force from Congress.Footnote 33 Table 2, below, briefly lists these positive cases. Put simply, there is not a single clear case of a president willing to enter a full-scale war absent legal authorization after the Korean conflict more than seven decades ago.

Table 2. Positive Cases—Crises in Which President Was Seemingly Willing to Employ Major U.S. Force (Actualized Wars in Bold)

Authors frequently emphasize in these cases that even when seeking and acquiring formal authorization, presidents have consistently claimed they did not need such approval and would act the same regardless of Congress’s own action (Fisher Reference Fisher2013; Griffin Reference Griffin2013). But these claims are just that—claims—and it must be kept in mind that presidents have strong incentives to bluff a willingness to act (Fearon Reference Fearon1995). The Johnson administration, for example, publicly maintained it did not need the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution to conduct the Vietnam War, but an abundance of evidence clearly shows that Johnson in private was not politically willing to actually do this.

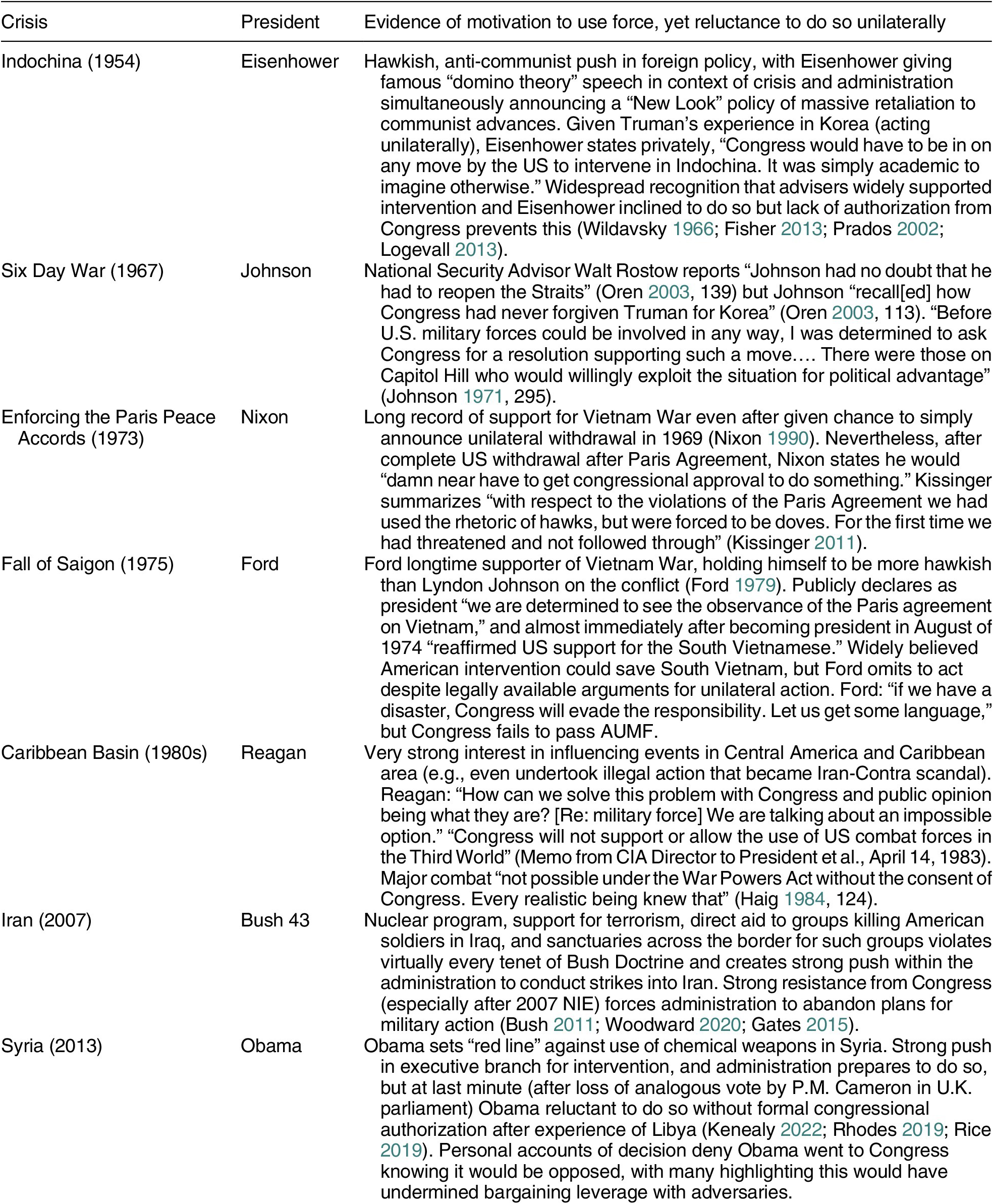

Negative Cases

Negative cases, in contrast, are cases in which the evidence suggests that the executive desired to intervene, but was deterred from doing so by a lack of formal authorization from Congress. Because these are “dog not barking” cases, they are difficult to locate and almost always overlooked in the war powers literature. Nevertheless, they are important to consider if one seeks to provide strong evidence of a necessary condition (Goertz Reference Goertz2017). Here, the evidence is unambiguous: there are many of these cases from the 1950s to the present—including under some of the most hawkish presidents least likely to respect constitutional boundaries (see Table 3). Note that some of these episodes seemingly contemplated actions well short of full-scale war. If a president was unwilling to intervene at a level short of full-scale war unilaterally, it then follows a fortiori they would certainly have been unwilling to enter a much more casualty intense conflict absent formal authorization.Footnote 34

Table 3. Negative Cases—Crises in Which Action Was Seemingly Deterred Specifically Due to Lack of Authorization

These negative cases are each incongruous with the predictions of the imperial presidency thesis, which would expect such cases to not exist. Instead, given that after the Korean War there are no clear examples of presidents willing to enter full-scale wars absent formal authorization from Congress, and many cases of presidents avoiding conflict due to a lack of formal authorization, this suggests that formal authorization from Congress has served as a sine qua non for the largest uses of force (confirming Hypothesis 2a).

Informal Sentiment as a Necessary Condition in Degree

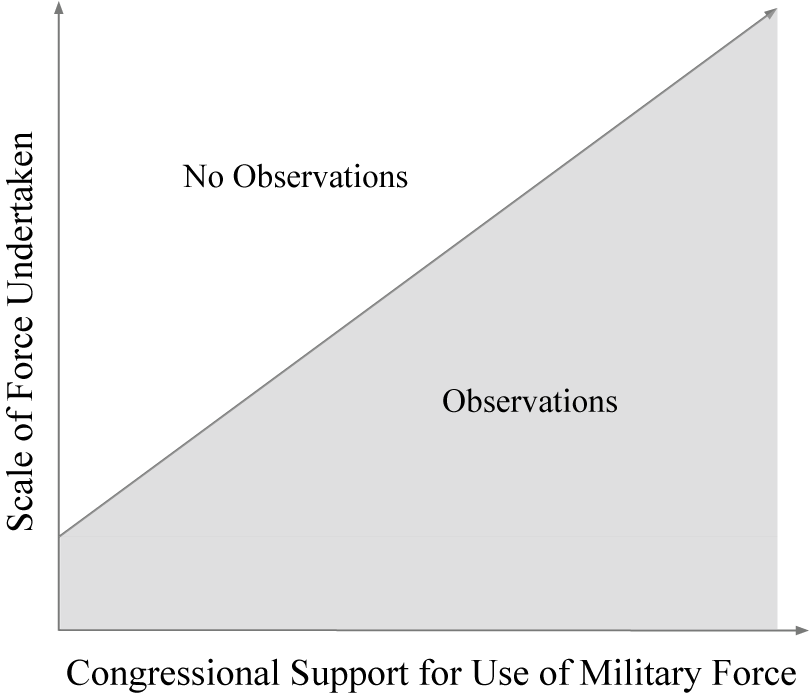

Hypothesis 1 proposed that informal sentiment toward the use of force would serve as a necessary condition in degree for all uses of force. In other words, even for unilateral uses of force, the level of casualties an executive would be willing to incur would be limited by informal congressional support for the specific use of force. On one end of the spectrum, presidents might have few qualms about conducting a show of force—or even ordering an isolated drone strike—in the face of congressional opposition. As the contemplated risk of American casualties increased, however, higher levels of support in Congress would be seen as necessary. We would thus expect a scatter plot of observations of American uses of force similar to Figure 8 (the signature plot yielded by a necessary condition in degree—see Goertz Reference Goertz2017; Dul Reference Dul2016).

Figure 8. Expectations: Necessary Condition in Degree

Appendix II of the Supplementary Material discusses how a novel dataset of “Congressional Support Scores” (i.e., informal sentiment in Congress) for nearly two hundred U.S.-relevant postwar crises was measured. In short, potentially-relevant floor speeches from foreign policy leaders in Congress were hand-coded for expressed support or opposition to the use of force in each crisis. In crises in which force was actually utilized, scores only include speeches prior to the use of force. The positions of speakers were then aggregated to create an overall “Congressional Support Score.” As a robustness check, these scores were also re-estimated using GPT-3.5 to predict a label for each potentially relevant floor speech from every member of Congress. Validation exercises show that these estimated “Congressional Support Scores” far outperform any other existing proxy for congressional sentiment toward the potential use of military force. Because the scores obtained by hand labeling exhibit higher performance, they are presented here, but very similar findings are exhibited when utilizing the GPT-3.5 predicted labels as well. Additionally, as a further robustness check, brief qualitative descriptions are provided in Appendices III (positive cases) and IV (negative cases) of the Supplementary Material.

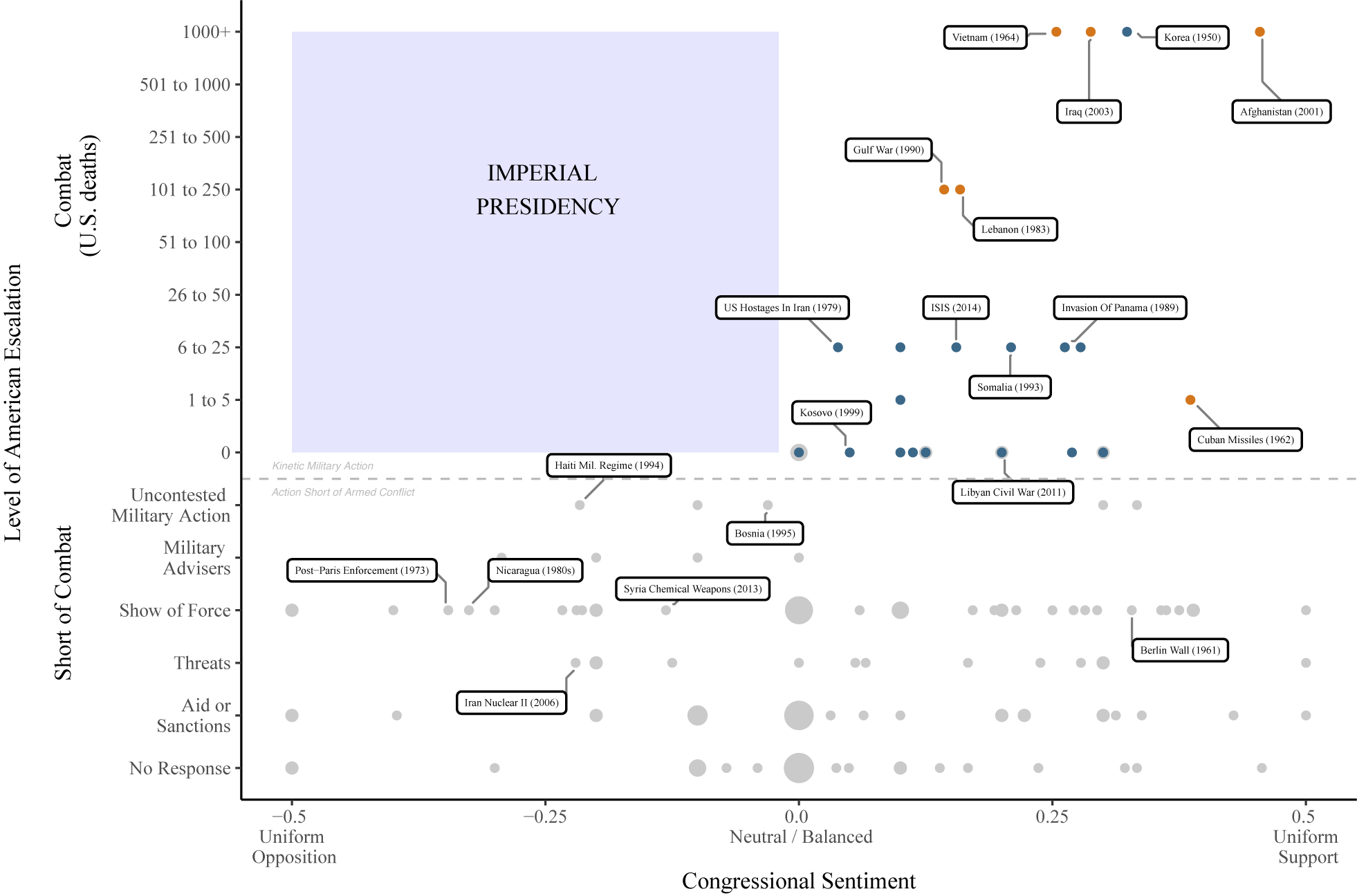

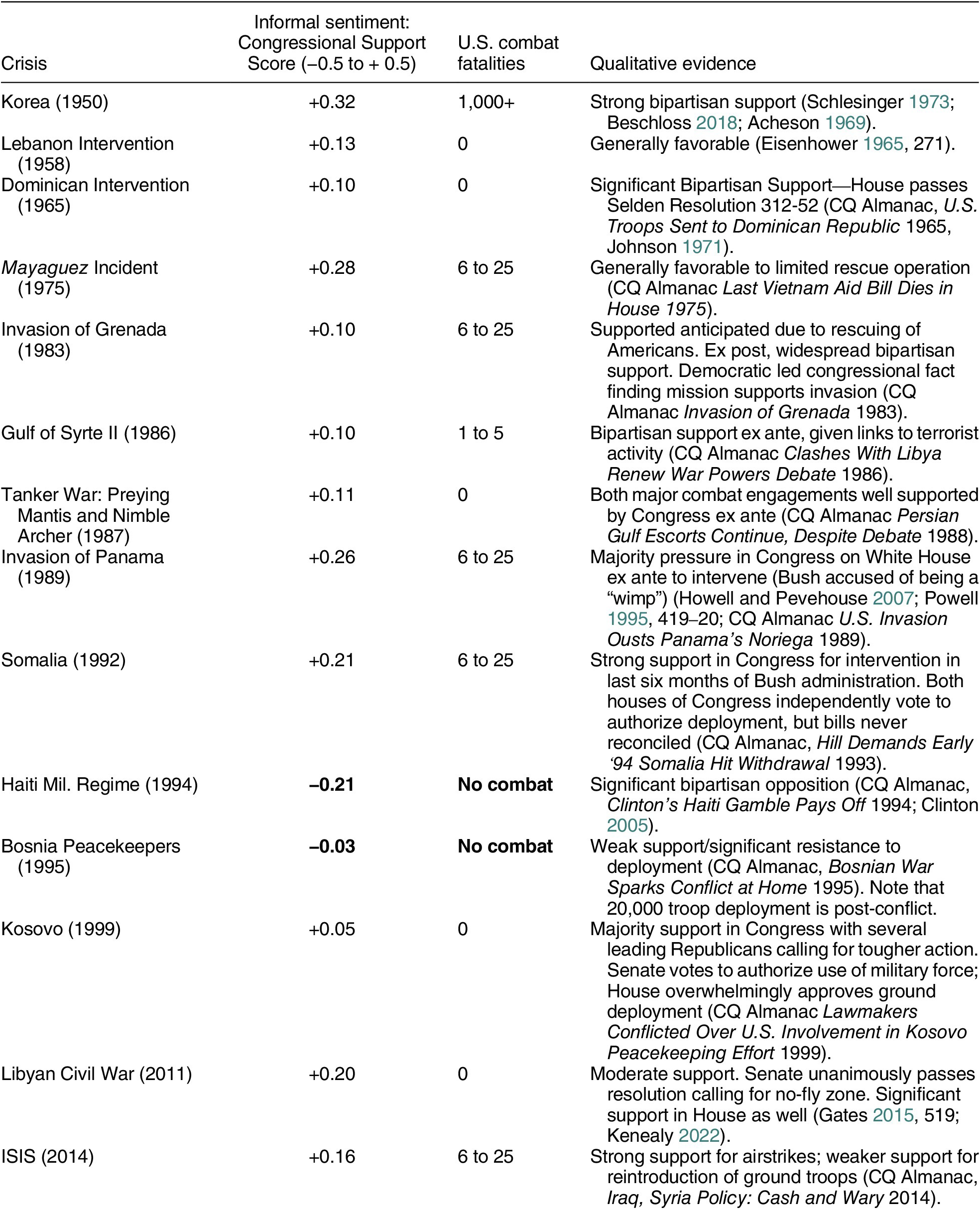

Figure 9 depicts U.S.-relevant crises plotted by the sentiment expressed in Congress toward the use of force versus the amount of force actually employed. Orange dots correspond to uses of force undertaken with congressional approval, whereas those undertaken unilaterally are shown in blue. Crises that did not involve American combat are shown in gray. The Y-axis ranges from crises in which the US took no action whatsoever to full-scale war involving more than one thousand U.S. combat fatalities. Crises above the horizontal dashed line represent conflicts in which American forces engaged in actual combat, while those below the line consist of crises in which American action was limited to that short of armed conflict.

Figure 9. Level of Force Employed by Support in Congress for Use of Military Force in Crisis

Positive Cases

Again, both positive and negative cases need to be considered. Positive cases are, simply, use of force observations. Negative cases involve situations in which the executive was otherwise inclined to use force, but was deterred from doing so due to opposition in Congress.

The imperial presidency thesis would predict the presence of positive cases in the upper left portion of the plot—that is, Congress expressing opposition to the use of force, but the commander-in-chief choosing to use it anyway. Indeed, the primary evidence given in favor of the theory is cases in which it is purported Congress opposed the use of force but the president undertook an intervention regardless (Fisher Reference Fisher2013; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1973). The data, instead, exhibit little evidence of this when it comes to initial use of force decisions,Footnote 35 and instead show the pattern predicted in Figure 8. The same pattern is also yielded when utilizing alternative measures (GPT speech labeling or qualitative case codings): we simply do not observe higher level uses of force absent higher levels of congressional support. The scatter plot is thus consistent with the expectations of Hypothesis 1 and difficult to square with the conventional wisdom of an unconstrained executive.

Instead, we see that the parade of unilateral uses of force frequently cited by proponents of the imperial presidency (the blue dots) exhibit far less imperialism than asserted: while they lacked formal legal authorization, they almost always had the informal backing of the legislature (see Table 4). The three most casualty intensive operations after the Korean War lacking formal authorization from Congress—Panama, Somalia, and ISIS—each clearly saw a Congress ex ante push the president into acting even while declining to formally authorize the operation. In October 1989, for example, even otherwise dovish Democrats accused the president of being a “wimp” after the administration failed to intervene in support of a coup in Panama against the Noriega government.Footnote 36 But even while strongly pushing for the White House to use force—Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell recalled, “Democrats and Republicans in Congress began jumping all over the administration” for not acting (Powell Reference Powell1995, 419)—lawmakers refused to formally authorize it. Indeed, a proposed AUMF for this purpose was tabled in the Senate.Footnote 37 Instead, the Senate passed a statement (99-1) that “the President in his capacity as Chief Executive and Commander-in-Chief has authority” to take action unilaterally in Panama, and that Congress supported “remov[ing] General Manuel Noriega from his illegal control of the Republic of Panama.”Footnote 38 Democratic Senator Sam Nunn, the Chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, argued that no formal authorization from Congress would be needed because “the President has plenty of authority.”Footnote 39

Table 4. Unilateral Uses of Force Often Cited as Evidence of Imperial Presidency

A similar story would play out 25 years later when Congress urged intervention against ISIS but refused to formally authorize the operation. Republicans attacked the administration for underestimating the threat, with Obama infamously calling the group the “JV Team.” Senator John McCain accused the president of “fiddling while Iraq burns,” and when pushing for U.S. intervention made clear that “the president…must make some decisions.”Footnote 40 Pushing for action while avoiding responsibility was widespread: Republican Representative Jack Kingston admitted “A lot of people would like to stay on the sideline and say, ‘Just bomb the place and tell us about it later,’…We can denounce it if it goes bad, and praise it if it goes well and ask what took him so long” (Tama Reference Tama2023, 98). In the words of one Democratic aid, by pushing for intervention but avoiding a formal vote lawmakers “were in a position where they could shit all over the president…but in no way have to own the campaign” (Tama Reference Tama2023, 102). Close Obama adviser Ben Rhodes would bemoan this typical dynamic it faced with Congress: lawmakers would “press for action but want to avoid any share of the responsibility” (Rhodes Reference Rhodes2019, 236).

The 1999 Kosovo and 2011 Libya interventions are also good illustrations of this. While neither received formal, legally binding approval from Congress, both had significant bipartisan support (even if far from uniform).Footnote 41 For example, while avoiding responsibility via formally authorizing the president to use military force against Libya in 2011, the Senate unanimously passed a non-binding resolution calling for United Nations intervention. McCain stated the point of a non-binding sense-of-Senate resolution was to “urge the President of the US to take long-overdue action to prevent the massacres that are taking place in Libya.”Footnote 42 But despite there being clear bipartisan support for the intervention, “quiet inquiry” by executive branch officials with congressional leaders “revealed that…[lawmakers] would not pass legislation, expressing in every conceivable way that they wanted no public votes” (Koh Reference Koh2024, 252).

The Korean War—notably the only major use of force undertaken by a president without formal approval—had overwhelming congressional support across political parties (Acheson Reference Acheson1969; Beschloss Reference Beschloss2018). Truman inquired with congressional leaders as to whether formal approval would be advisable, but was repeatedly told by congressional leaders to not bother, despite there being virtually unanimous support for intervention (Blomstedt Reference Blomstedt2016, 28, 36–7). Indeed, Republican Senators slammed the executive branch for not acting sooner, with one arguing instant action was needed and which could “be done if there is a will to do it by the executive branch of this Government. They need no legislation,” and asked if the administration would rather “sit back and twiddle [its] thumbs and do nothing.”Footnote 43

Hence, the parade of cases frequently cited as evidence of an imperial presidency falls short: there is little evidence of significant combat undertaken absent informal support in Congress, and lawmakers frequently support unilateral action by the White House. The general trend of unilateral action has not been executives acting against the wishes of Congress, but pursuant to them.

Negative Cases