No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 December 2015

1 Cuadernos, number 23 (marzo-abril, 1957), pp. 22–23.Google Scholar

2 “Decálogo del artista,” Desolación (New York, 1922), p. 207.Google Scholar

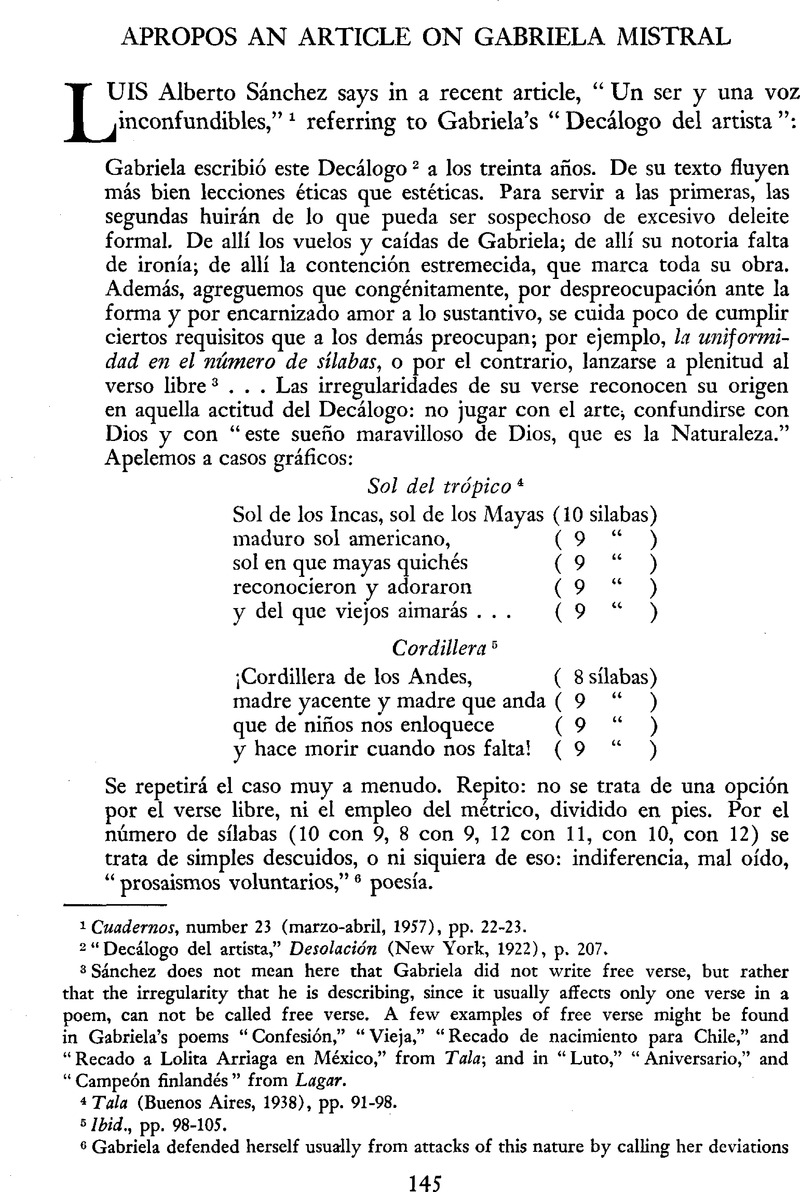

3 Sánchez does not mean here that Gabriela did not write free verse, but rather that the irregularity that he is describing, since it usually affects only one verse in a poem, can not be called free verse. A few examples of free verse might be found in Gabriela’s poems “Confesión,” “Vieja,” “Recado de nacimiento para Chile,” and “Recado a Lolita Arriaga en México,” from Tala; and in “Luto,” “Aniversario,” and “Campeón finlandés” from Lagar.

4 Tala (Buenos Aires, 1938), pp. 91–98.Google Scholar

5 Ibid., pp. 98–105.

6 Gabriela defended herself usually from attacks of this nature by calling her deviations from the accepted norms “prosaísmos voluntarios.” These deviations are defended by Gerardo Diego on the grounds that they are “necessary abnormalities.”

7 Alonso, Amado in defending the irregularity of the poem “Fantasma” of Neruda, Pablo (Poesía y estilo de Pablo Neruda [Buenos Aires, 1951], p. 153)Google Scholar calls this anormalidad necesario “cuidadoso descuido” on the part of Neruda.

8 Homenaje a Gabriela Mistral (Madrid, 1946), p. 39.Google Scholar

9 Gabriela Mistral, su vida y su obra (Santiago de Chile, 1946), p. 21.Google Scholar

10 “Geste and Romance,” The Spirit of Romance (Norfolk, Conn., n.d.), p. 67 Google Scholar n.

11 The italics are Pound’s.

12 In conventional orthography: “Now if a man had sense enough to write a beautiful poem like this is, wouldn’t you think he would have had sense enough to be able to count up to ten on his fingers if he had wanted to?”

13 Ocampo, Victoria (“Gabriela Mistral y el premio Nobel,” Testimonios; tercera serie [Buenos Aires, 1946], p. 175)Google Scholar did not find a very rustic, outdoor Gabriela in April of 1937: “Gabriela descubría los encantos de este paisaje nuevo para ella [Argentina] (la arrastrábamos a las estancias de los alrededores … pues no le gustaba mucho salir)”

14 [ de Montolíu, Manuel], Prólogo of Las mejores poesías (líricas) de los mejores poetas (Barcelona [1923]), p. 174.Google Scholar

15 These observations are from the notes I took when I compared the first draft of the poem which is in manuscript to the first published version. From 1953 to the time of Gabriela’s death (January 10, 1957) I had access to all the poetry she had in manuscript. The quotations from Gabriela in this article, in which the source is not given, are from personal conversations with her during this same period.

16 In the version of “Una palabra” that appears in Lagar (Santiago de Chile, 1954), pp. 53–54 Google Scholar, there are still more changes: the third stanza is broken into two after verse 5; la in verse 1 becomes mi; entre, verse 17, is changed to con. Not only was it difficult for Gabrila to read through a poem silently without making some correction, even when she was making a tape recording of her poems she corrected them orally: in the case of “Una palaba” which she recorded in the Library of Congress on December 12, 1950, she changed cal y mortero, verse 3, to cales y cales.

17 Cuadernos hispanoamericanos (sept.-dic, 1949), pp. 344–345.Google Scholar

18 Machado, Antonio, prologue of his Páginas escogidas (Madrid, 1946), p. 39.Google Scholar

19 “Imperfección y albricia,” Homenaje a Gabriela Mistral (Madrid, 1946), p. 39.Google Scholar

20 “Surco de Gabriela Mistral,” op. cit., p. 30 Google Scholar. The italics are mine.

21 Fotunately, thanks to the diligence of Francisco Aguilera, Assistant Director of the Hispanic Foundation of the Library of Congress, Washington, D. C, Gabriela’s voice can still be heard. On December 12, 1950, she made recordings of the following poems: “Meciendo,” “Apegado a mí,” “Dormida,” “Canción quechua,” “Sueño grande,” “Arrullo patagón,” “Ronda de la ceiba ecuatoriana,” “Ronda de segadores,” “Encargos,” “Miedo,” “Benediciones,” “El hijo,” “La cajita de Olinalá,” “La manca,” “La casa,” “Una palabra,” “Pais de la ausencia,” and “Recado a Lolita Arriaga en Mexico,” which are all available on tape from the National Tape Library, Washington, D. C. Francisco Aguilera (“Iberian and Latin American Poetry on Records,” The Library of Congress Quarterly Journal of Current Acquisitions, vol. 14, no. 2 [February, 1957], p. 51) quotes Gabriela’s attitude toward recording poetry: “I am very much interested in this work of the Library of Congress. Poetry hushed and inert in books fades away or dies. The air, not the printed page, is its natural home. Poetry should not suffer the fate of a stuffed bird. Recordings serve it well.”

22 The italics are Gabriela’s.

23 Mistral, Gabriela, “Recado para Julio Barrenechea,” Nosotros (June, 1943), p. 46.Google Scholar

24 “Diálogo entre Juan de Mairena y Jorge Meneses,” Abel Martín (Buenos Aires, 1943), p. 54.Google Scholar

25 Reprinted in Indice (15 de abril, 1952). It appeared first in La gaceta literaria (1 de marzo, 1929) in which Ernesto Giménez Caballero asks the “directores culturales de España” what they think of the new generation of Spanish poets, the Generation of the Twenties.