Introduction

The island of Bornholm has a strategically important position in the Baltic Sea and has historically been a hub of transport, trade and connection (Figure 1). But this favourable location also manifests instability in island geopolitics, a phenomenon that continues today.

Figure 1. Bornholm in the Baltic Sea (figure by Anders Pihl).

Bornholm’s rich Iron Age (c. 500 BC–AD 1000) archaeology has been a focus of research since the nineteenth century. Six prehistoric fortifications are identified but have been investigated only sporadically since the 1950s, although approaches have been made towards a major research project to investigate all six fortifications (Nielsen & Staal Reference Nielsen, Staal and Olausson2014). We therefore lack basic chronological understanding of the fortifications and their roles in the natural, social and cultural landscapes of Bornholm. In contrast, research from later decades in Sweden, Norway, mainland Europe and in the British Isles has updated and added nuance to interpretations of fortifications, directing attention towards their multiple functionalities (cf. Ibsen et al. Reference Ibsen, Ilves, Maixner, Messal and Schneeweiß2022).

In 2022, the project Fortified Island (FORTIS) received funding to evaluate and improve our knowledge of Bornholm’s fortifications, focusing on the period c. 100 BC to AD 1000. Running from December 2023 to March 2027, the project uses a multimethod approach to upgrade our understanding of the fortifications in the context of societal developments on Iron Age Bornholm, both locally and from a European perspective.

Iron Age Bornholm

The rich archaeological landscape of Bornholm means that the island has a high density of good-quality data (Figure 2). As with the other Baltic Sea islands, Öland and Gotland, an influx of wealth in the Iron Age is exemplified by large numbers of Roman silver and gold coins (Horsnæs Reference Horsnæs2013). Over the past 40 years, amateur metal-detectorists have identified a total of 602 detector localities on Bornholm. These include five high-status sites with thick cultural layers and finds dating across the first millennium AD. Most famous of these is Sorte Muld, known for its 3200 miniature gold-foil figurines (guldgubber) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Key localities on Bornholm dating to the first millennium AD (figure by Anders Pihl).

Figure 3. Gold-foil figurine (guldgubbe) measuring approx. 26 × 21mm, from Sorte Muld c. sixth–eighth centuries AD (photograph by Martin Stoltze/Bornholm Museum).

Under the FORTIS project, a PhD study combines archaeological settlement evidence with cartographical studies and toponymy (the study of place names), to enable high-resolution mapping of first millennium AD developments in settlement patterns and agricultural organisation. This study extends a pilot investigation in northern Bornholm that revealed hitherto undiscovered traces of Iron Age rural organisation in early-nineteenth-century cadastral maps (Pihl Reference Pihl, Kristiansen and Bentsen2021). FORTIS further explores how beacons and surveillance systems were organised on the island, drawing on other Baltic islands for comparative discussions, particularly the larger ongoing project about Öland’s fortifications (Lidén et al. Reference Lidén, Eriksson, Kalmring, Isaksson, Papmehl-Dufay and Victor2024).

Bornholm’s many Iron Age cemeteries are well researched in terms of kinship, warrior elites and object chronologies (Lund Hansen Reference Lund Hansen, Hansen and Bitner-Wróblewska2010), and the island constitutes a large proportion of the known Iron Age weapon graves from Denmark (Jørgensen & Nørgård Jørgensen Reference Jørgensen and Nørgård Jørgensen1997; Watt Reference Watt, Jørgensen, Storgaard and Thomsen2003). FORTIS aims to evaluate distributions of cemeteries with weapon graves and practices of depositing weaponry in burials. Situating these as aspects of social and ritual communication, weapon graves can be compared with ritual weapon depositions in wetlands and in the island’s high-status settlements.

On a general level, a shift in the distribution of cemeteries can be detected in the fifth century AD. Cemeteries from the first to fourth centuries are evenly spread across the island, while in the fifth to eighth centuries cemeteries are concentrated in the coastal areas, particularly in the north (Figure 2). This change coincides with the abandonment of Early Iron Age field systems, a move that left central parts of the island as commons and heathlands into historical times (Pihl Reference Pihl, Kristiansen and Bentsen2021: 55, 59). All of the island’s preserved fortifications are found in these heathlands.

Bornholm’s fortifications

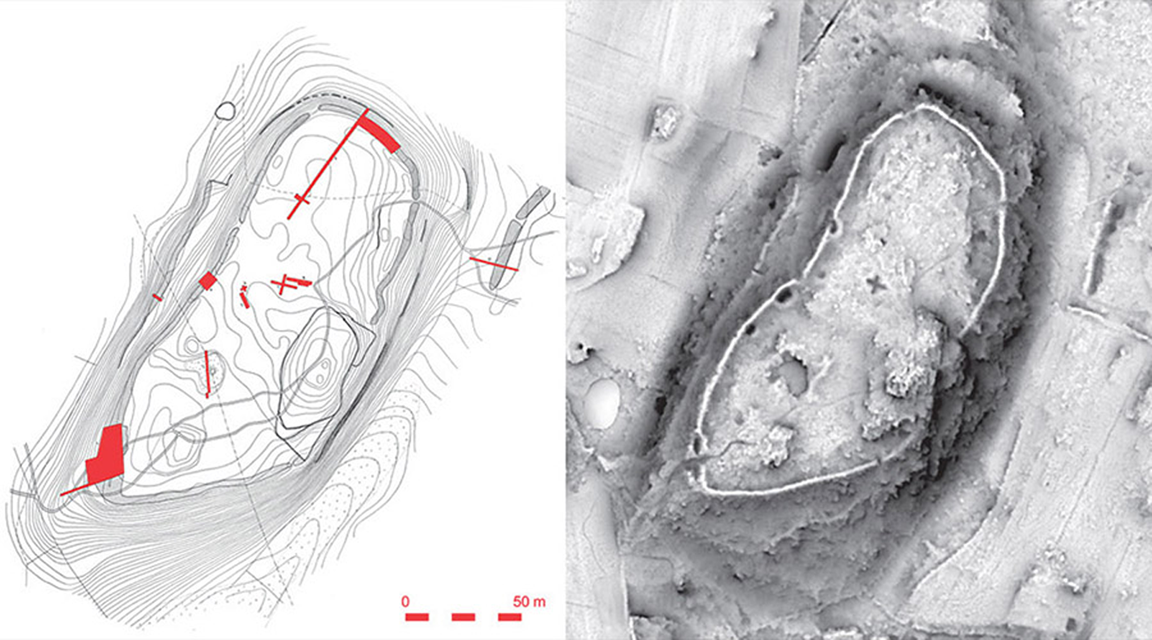

In its first year, the FORTIS project has evaluated Bornholm’s six fortifications through field visits, historical maps, high-resolution lidar data and field reports from previous excavations (Figure 4). While more recent investigations have largely focused on restoration work, extensive excavations were carried out in the mid-twentieth century by Professor Ole Klindt-Jensen. His untimely death in 1980 prevented their completion, and results were only partly published (Klindt-Jensen Reference Klindt-Jensen1957).

Figure 4. Gamleborg, eastern Bornholm, in different registration formats: A) original cadaster from 1802 (CC BY 4.0, Danish Agency for Climate Data); B) 1950 excavation plan (drawing by Poul Simonsen; National Museum of Denmark’s archives) with excavated areas marked in red; C) lidar-scan 2019 (CC BY 4.0, Danish Agency for Climate Data) (figure by authors).

Bornholm’s fortifications are of different sizes and shapes, while all are placed at a distance from the sea and take advantage of the island’s rocky topography. Earthen or drystone walls were built to enhance steep cliffs and enclose large or small plateaus, surrounded by bogs or rivers. The presence of burials, standing stones, large boulders with cup marks and ritual depositions in the local environments around the forts indicate functions beyond strict military purposes.

Two northern fortifications, Borgen and Storeborg, are prehistoric in character but have never been excavated (Figure 5). Most of the forts contain evidence of activity in various periods. Lilleborg is the ruin of a medieval fortress from the thirteenth century AD, but underneath are burnt layers from the fifth century AD and traces of a Neolithic palisade from c. 3000 BC. Gamleborg in eastern Bornholm has finds of ceramics from the Late Bronze Age (c. 1100–500 BC) as well as the second–third and the tenth–eleventh centuries AD; and at Ringborgen in southern Bornholm, a large Neolithic enclosed site has been excavated, along with cemeteries from the three first centuries AD and the eighth century AD. Finds from the centrally placed Gamleborg derive only from the eleventh century AD.

Figure 5. Aerial photograph of the undated northern fort Borgen, July 2024 (photograph by Arne A. Stamnes).

Our archival studies reveal that no clear evidence for dating has been obtained from the wall constructions of any of the forts. Thus, we currently have only chronological information about associated activities, not building phases themselves. Therefore, the project fieldwork, consisting of small-scale excavations and geophysical prospections, will employ various dating methods to improve our understanding of the chronologies of each fort.

Conclusion

While previous research on Bornholm has focused on individual find groups or periods, the FORTIS project studies the island as a whole, using data assemblies as evidence of interlinked social, ritual and military dynamics: fortifications and beacons, settlements and agrarian systems, and weapon burials and their place in the landscape.

Such analyses are still in progress but, through the high-resolution study of Bornholm, results will contribute to the understanding of Iron Age society and geopolitical developments in Scandinavia and the Baltic Region.

Acknowledgements

The project is a collaboration between the National Museum of Denmark and the Museum of Bornholm with participation of scholars from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research and from Moesgaard Museum, Denmark.

Funding statement

Fortified Island is funded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark (Grant number 2063-00037B) and Kibsgaardfonden.