Introduction—historical and archaeological context

The Łambinowice Site of National Remembrance holds a unique status in Poland, Europe and the world. Since 1870, through decades marked by wars and the displacement of the civilian population, successive prisoners of war and resettlement camps operated on the outskirts of the small village of Lamsdorf (Rezler-Wasielewska Reference Rezler-Wasielewska2017). The landscape of these former camps has been legally protected since the 1960s and a dedicated museum institution (Central Museum of Prisoners of War) was established in 1964, which oversees the preservation and management of this historical site (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice: A) view of the PoW cemetery and the surrounding forests, where PoW and resettlement camps were located; B) a quarter of marked graves of PoWs dated to the Great War (source Central Museum of Prisoners of War; photographs by D. Frymark).

An important part of the Museum’s activities involves preparing scientific research on the site’s history. From 2022 to 2024, multidisciplinary fieldwork was conducted to document material traces of the former camps that are preserved in the local forest landscape (Kobiałka et al. Reference Kobiałka2023). Thousands of these traces were successfully registered using remote sensing data (e.g. lidar data, historical aerial spy photographs).

Archival research revealed that the site likely contains unknown and unmarked graves of PoWs from various nationalities, including Polish and Italian soldiers, as well as of civilians from the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, who died in captivity. Such records indicate that in 1959, representatives of the Italian government searched for the graves of Italian soldiers who had died in Poland during the Second World War. Up to 60 Italians were believed to be buried in the cemetery associated with the functioning of Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf, but their graves were not marked and could not be located in 1959 because of the lack of care for the cemetery (Kobiałka et al. Reference Kobiałka2024).

Excavations carried out in 2023 led to the discovery and examination of two features identified as graves in the ‘unknown quarter’ at the camp cemetery. Camp numbers preserved on identification tags found alongside human remains in these graves suggested that the buried individuals were Italian soldiers who had died in Lamsdorf around 1943 to 1944. Relevant Polish institutions and the Embassy of the Italian Republic in Poland were notified of this significant discovery, prompting the decision to continue archaeological research.

The site—field research in 2024

Interdisciplinary research conducted at the site from 2022–2024 allowed for comprehensive documentation of material remains related to the Lamsdorf camps. The 2024 efforts primarily employed invasive methods, focusing on excavating and identifying the ‘forgotten’ graves, with possible exhumation depending on the situation.

Excavation of a 24 × 19m trench allowed for the documentation of 60 rectangular structures, each containing human remains. It can be inferred that the entire quarter was arranged to a specific plan. The layout consisted of five rows of graves: four rows with 13 burials each, and a final row containing eight graves (Figures 2 & 3). In all cases, the deceased were buried in an extended supine position with their heads turned to face north-east. Traces of wooden coffins, with variable preservation, were recorded in most of the burials.

Figure 2. Archaeological excavation: A) preparing the trench for photographic documentation; B) visible outlines of grave pits (source Central Museum of Prisoners of War; photographs by D. Frymark).

Figure 3. Excavation of the grave pits; each pit contained a single individual in an extended supine position (source Central Museum of Prisoners of War; photographs by D. Frymark).

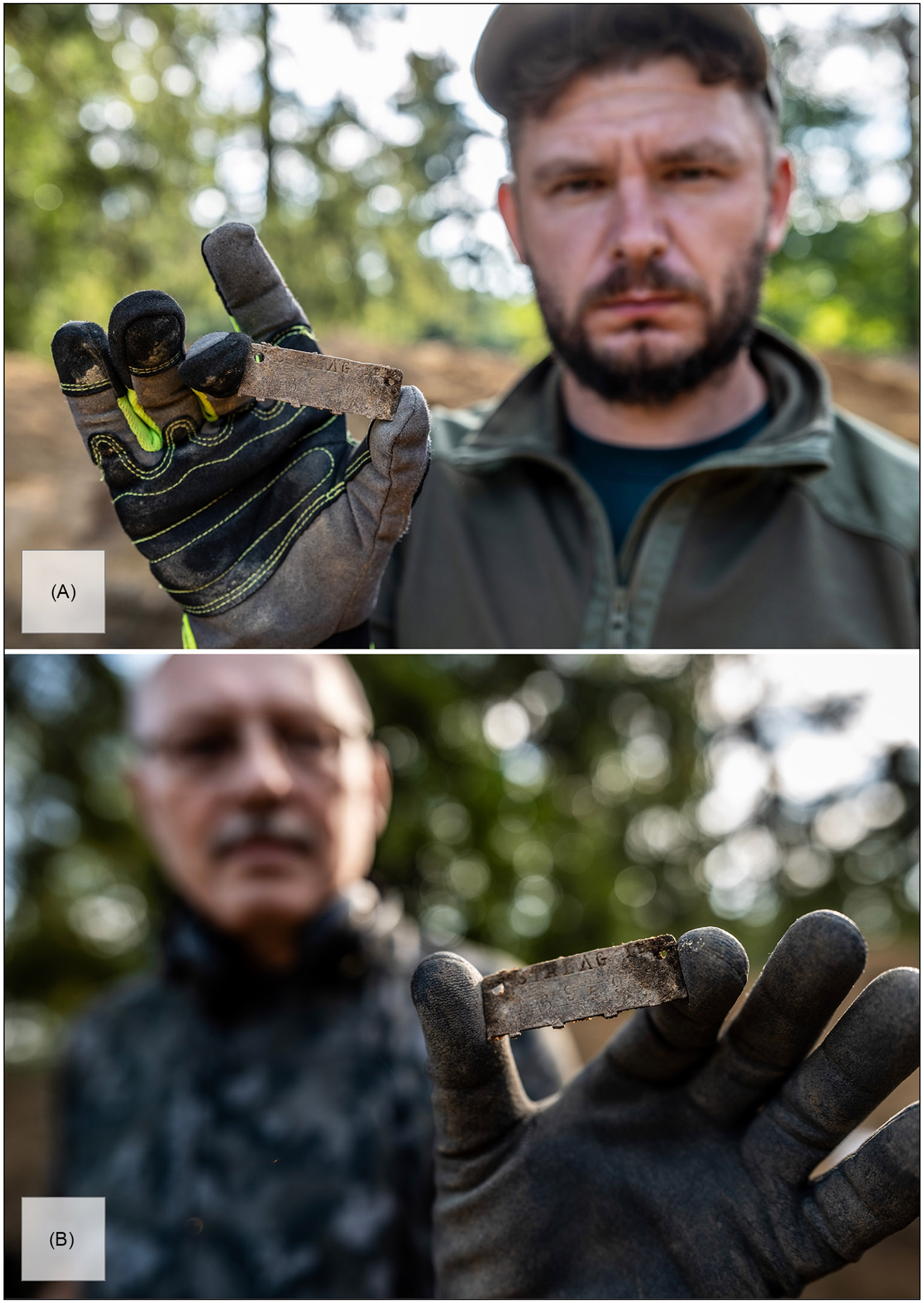

The individuals were not buried in uniforms or civilian clothes as evidenced by the virtual absence of personal belongings in the graves. Only two crucifixes, one medallion and three rings were found in the grave pits. Crucially, broken identification tags were found in nearly all the graves (Figure 4). Conservation work was conducted immediately after the completion of the excavations, enabling the successful deciphering of almost all the dog tags, which was key for restoring the identities of the buried individuals.

Figure 4. Examples of broken dog tags found in graves (source Central Museum of Prisoners of War; photographs by D. Frymark).

Due to intensive archival research, the project team was able to create a detailed list of the given names, surnames and dates of birth and death of each Italian soldier who died in Lamsdorf from 1943–1944. Notably, some historical records even included information about the row and grave number where each individual was buried in the ‘Italian quarter’. By comparing the data from the dog tags with the row and grave numbers, along with the camp numbers given to prisoners, we were able to identify the discovered human remains by name. In this case, both historical and archaeological (material) data aligned, confirming the identities of the individuals.

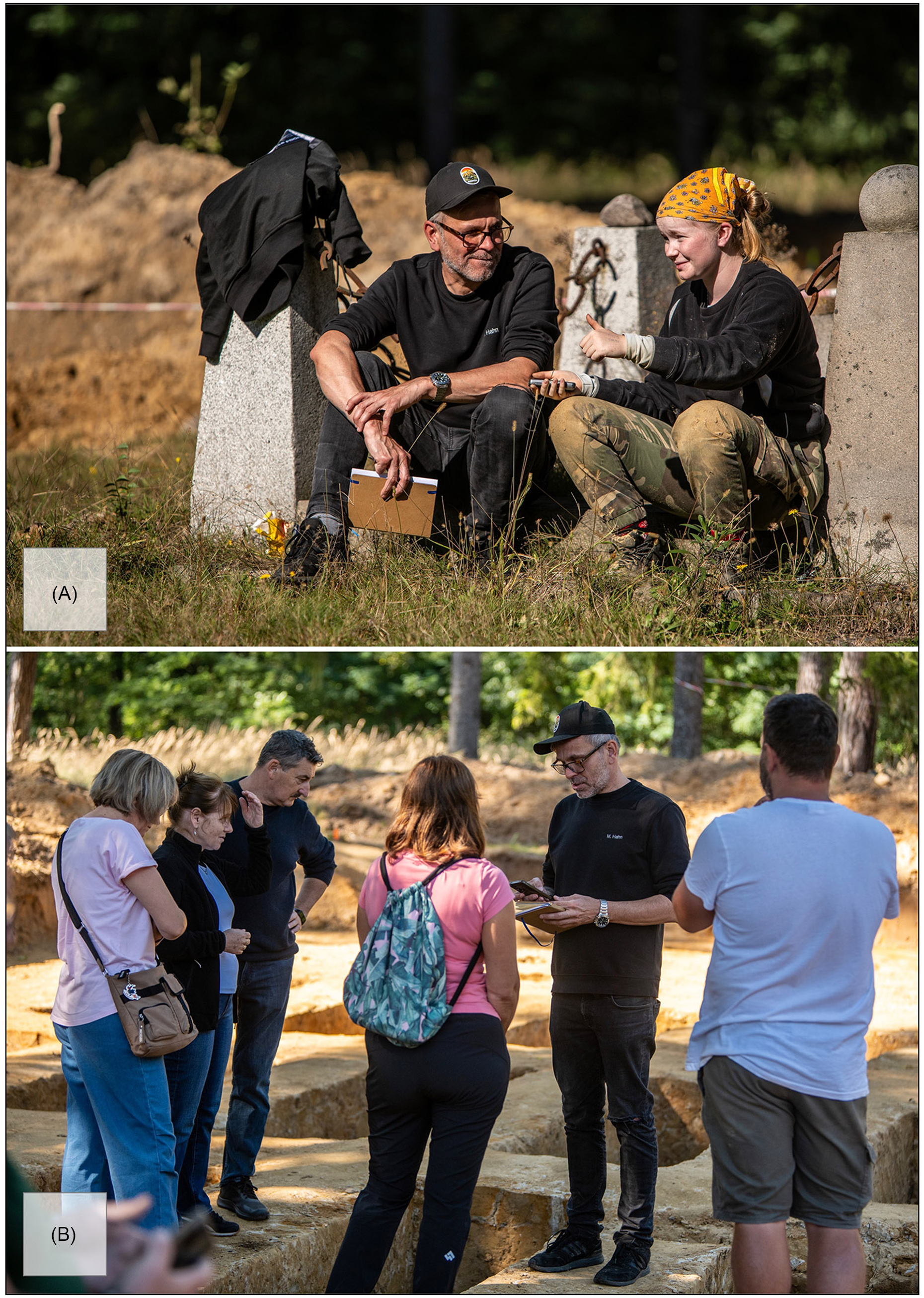

The work was conducted according to the highest standards of archaeological field research, while also considering the important ethical aspects involved. Yet the project goes beyond merely exhuming human remains. Throughout the fieldwork, a drone was used to capture photographs, and measurements were taken with a real-time kinematics GPS device. The remains were also documented using photogrammetry and underwent analyses in the field by both physical and forensic anthropologists and a forensic pathologist. Fieldwork was complemented by archival research. Additionally, the fieldwork and its results were analysed within the framework of the so-called ‘ethnography of exhumations’, examining the impact of exhumations on the local community and their broader social, cultural and political context (Ferrándiz & Robben Reference Ferrándiz and Robben2015) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The ethnography of exhumation: A) interview with a volunteer; B) interview with a group of visitors (source Central Museum of Prisoners of War; photographs by D. Frymark).

Maintaining ethics was equally important during both the planning and the implementation of the project. This included consultation with representatives of the Italian Republic in Poland, and, at their request, the remains of the Italians discovered were temporarily moved to the Italian Soldiers’ Cemetery in Warsaw, where they await their families’ decisions regarding possible reparation to Italy. In this way, the memory of these forgotten soldiers, buried in unknown and unmarked graves, has been brought back to life. This is particularly important for their relatives, who, after 80 years, finally learned the exact location where the remains of their loved ones had been buried.

Conclusion

Archaeology provides tools and methods to address the ‘stains’ in the history of the PoWs of Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf. One such issue is the identification of deceased prisoners who were buried in unknown and unmarked graves. In this context, archaeology serves not only as a scientific discipline but also as a practice of memory; a means of restoring the memory of the difficult and painful reality of the Second World War (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Grassroots commemoration observed for the PoWs during the excavation (source Central Museum of Prisoners of War; photographs by D. Frymark).

The project highlights the immense value of archaeology as a humanitarian practice—it is both a social and cultural activity. The families of the discovered Italians were informed of the findings, with some expressing a wish for the remains to be repatriated to Italy to rest in their native soil among their loved ones.

Funding statement

The research was co-financed by the Polish Minister of Culture and National Heritage.