Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 August 2023

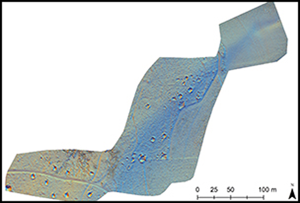

Although conflict archaeology is now well established, the archaeological remains of many specific military confrontations are still to be explored. This article reports the results of fieldwork to document the site of the Battle of the Bulge (16 December 1944–25 January 1945). The authors use drone-mounted 1m-resolution LiDAR and very high-resolution simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) methods to reveal more than 940 features within the forested Ardennes landscape, many of which were subsequently visited and confirmed. As well as highlighting the potential of the LiDAR-SLAM method, deployed here (both in this geographic region and in conflict archaeology) for the first time, the survey results emphasise the need for a debate on managing the heritage of a key modern conflict landscape in Europe.