Kota Tampan (5°63′318″ north, 100°88′424″ east) is an open-air site located in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Lenggong Valley, in the northern region of Peninsular Malaysia (Figure 1). Lenggong Valley is exceptionally important for the archaeology of the Asia Pacific region as it possesses one of the longest archaeological records of early man in one single locality outside the African continent, spanning the last 1.8 million years (Saidin Reference Saidin2012). Archaeological investigations at the site in 1954 uncovered a large assemblage of stone tools sealed immediately beneath deposits of Young Toba Tuff from the Toba volcano (Sieveking Reference Sieveking1958; Majid Reference Majid1991). A super-eruption c. 74 kya triggered a ‘volcanic winter’, resulting in a drastic decline in global temperatures (3–5°C), which must have affected the survival of human populations in Southeast Asia at that time (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Ambrose, van der Kaars, Ruehlemann, Chattopadhyaya, Pal and Chauhan2009). Their association with this eruption has led to assumptions of a date for the Kota Tampan stone tools before, or at least contemporaneous with, the super-eruption of Toba (Majid Reference Majid1991; Storey et al. Reference Storey, Roberts and Saidin2012). This hypothesis was questioned, however, by Gatti et al. (Reference Gatti, Saidin, Talib, Rashidi, Gibbard and Oppenheimer2013) based on the reworked nature of the sediments in the Lenggong Valley and radiocarbon dates published by Stauffer (Reference Stauffer1973). Stauffer (Reference Stauffer1973) published two radiocarbon dates from charcoal collected from a peat deposit at Ampang immediately beneath the volcanic ash layer dated to 35ka BP. This non-archaeological deposit has been incorrectly linked in the literature to Kota Tampan (Gatti et al. Reference Gatti, Saidin, Talib, Rashidi, Gibbard and Oppenheimer2013), despite being approximately 280km away. While Gatti et al. (Reference Gatti, Saidin, Talib, Rashidi, Gibbard and Oppenheimer2013) argued that sediments at Kota Tampan were subject to fluvial redeposition, Majid (Reference Majid1991) and Isa (Reference Isa2007) both contended that the assemblage of Kota Tampan was discovered in situ. Isa (Reference Isa2007) later revisited the Kota Tampan site and secured an optical stimulated luminescence (OSL) date for the layer where the stone tools were discovered, which returned a date of 70 kya.

Figure 1. Location of Kota Tampan (map illustrated by Chaw Yeh Saw).

The chronology of Kota Tampan remains uncertain. Here we focus instead on a re-examination of the stone assemblage using a technological approach that examines the technological attributes of the artefacts (i.e. type of striking platforms, angles, flake scars, number of removals and the like). Previous studies by Majid (Reference Majid1991) and Isa (Reference Isa2007) were heavily focused on classification and typological study. Such approaches have been criticised because they limit our understanding of variation and constrain our understanding of the technological attributes and reduction techniques (see Marwick Reference Marwick2008). Given the significance of Kota Tampan as one of the most important Palaeolithic archaeological sites in Mainland Southeast Asia, it is crucial to develop a technology-based model drawing upon methods used across Southeast Asia to understand its regional context.

Our study re-examined 69 stone artefacts excavated at Kota Tampan by Ann Sieveking in 1954 (Sieveking Reference Sieveking1958), which are currently stored in the Department of Museums Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. Sieveking (Reference Sieveking1958) recorded a total of 234 identifiable stone artefacts; of these, 165 artefacts could not be located, however. The context of artefacts included in this study was retrieved from published reports (Sieveking Reference Sieveking1958; Walker & Sieveking Reference Walker and Sieveking1962). Table 1 and Figure 2 summarise the artefact types, raw materials and reduction technology of the lithic assemblage. The classification of artefact types is based on the definition proposed by Moore and colleagues (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Sutikna, Morwood and Brumm2009). Extended metric information on the analytical variables of the stone tools are stipulated in the supplementary tables (Tables S1–7).

Table 1. Stone artefacts recovered from Ann Sieveking's 1954 excavation.

Figure 2. Reduction sequence of stone artefacts from Kota Tampan (illustrated by Chaw Yeh Saw & Noridayu Bakry).

Our analysis shows that the assemblage predominantly comprises small flakes measuring 60–78mm (63.77 per cent, N = 44), followed by bipolar artefacts (20.29 per cent, N = 14) and a small number of core stones (13.04 per cent, N = 9). Freehand percussion (77 per cent, N = 53) and bipolar percussion (23 per cent, N = 16) were the two main stone flaking techniques employed. The most common method of core reduction was multiplatform core reduction (55.60 per cent, N = 5), following by single-platform (22.20 per cent, N = 2), radial (11.10 per cent, N = 1) and bidirectional reduction (11.10 per cent, N = 1) (Figure 3a–c). All core stones are small (60mm–0.14m) and not extensively reduced where the majority of cores have five to six removals. The flake assemblage was almost entirely the result of early stage reduction (97.70 per cent, N = 43), as demonstrated by a high proportion of early reduction flakes.

Figure 3. Stone artefacts from Kota Tampan: a) bidirectional core; b) multiplatform core; c) radial core; d) bifacial tool; the numbers represent the sequences of flake removal from artefacts a–d; scale: 30mm (image by Hsiao Mei Goh & Noridayu Bakry).

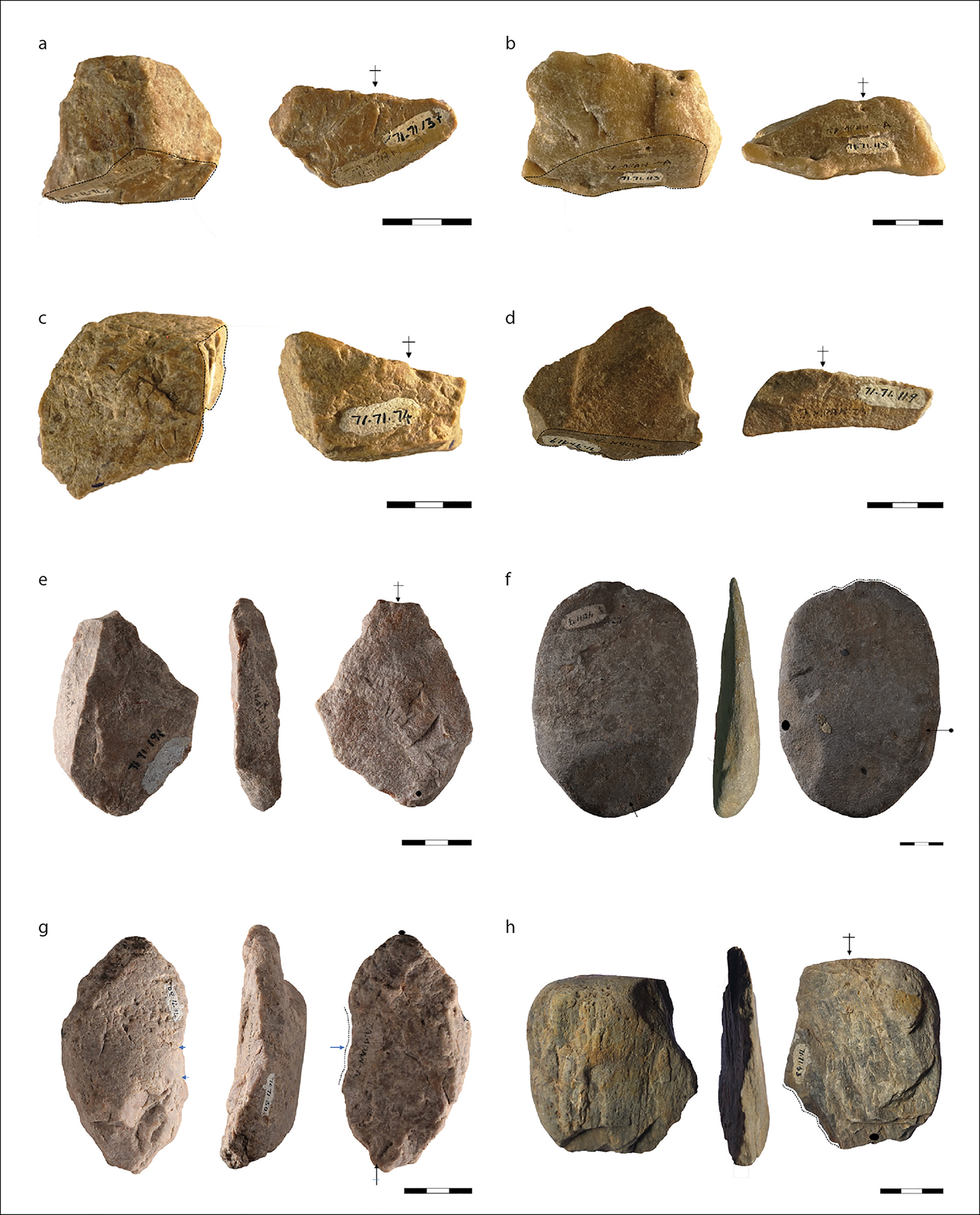

Almost half of the flake assemblage (N = 20) was unifacially retouched on early reduction flakes (Figure 4), whereas another eight flakes were further modified using the truncation method (Figure 5a–d). We also identified 12 bipolar flakes (Figure 5e–h) and one bifacial pebble tool that was centripetally flaked (Figure 3d). The majority of the stone artefacts (94 per cent, N = 65) were made on locally available quartzite and quartz cobbles, with only four stone artefacts made from slate and fine-grained granite.

Figure 4. Flake tools from Kota Tampan: a–d) early reduction flakes; e–g) retouched early reduction flakes; h) early reduction flake; scale: 30mm (image by Hsiao Mei Goh & Noridayu Bakry).

Figure 5. Flake tools from Kota Tampan: a–d) truncated early reduction flakes; e–h) bipolar flakes; scale: 30mm (image by Hsiao Mei Goh & Noridayu Bakry).

Discussion and conclusion

This study indicates that the early humans of Kota Tampan employed freehand and bipolar percussion techniques in stone flaking. Most of the stone artefacts were unifacially retouched and produced during the early stages of reduction. Although the number of specimens is small, it seems that the most commonly used method was multiplatform core reduction. Since the 1980s, the lithic assemblage of Kota Tampan has been attributed to Anatomically Modern Humans (Majid Reference Majid1991); our new analysis of the technological attributes of the Kota Tampan assemblage further strengthens this claim. The Kota Tampan assemblage also strongly resembles the 40 000-year-old stone artefacts recovered from Bukit Bunuh, a lithic workshop located just a few hundred metres from Kota Tampan (Saidin Reference Saidin, Bacus, Glover and Pigott2006). The similarities between the two assemblages together with the recent OSL date from Kota Tampan (Isa Reference Isa2007) and evidence from other early human sites across Southeast Asia (Bae et al. Reference Bae, Douka and Petraglia2017) suggest that early modern humans arrived in and began to exploit the insular Sundaland around 70 000 years ago.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.158

Acknowledgements

This project is funded by Universiti Sains Malaysia (P4595), and we would like to thank the Department of Museums Malaysia for the permission to study the Kota Tampan stone assemblage.