Introduction

Caches are one of the most common types of ritual deposit found in the archaeological record. The term ‘cache’, however, can refer to many different activities. Schiffer (Reference Schiffer1987: 79–80) defines a ritual cache as a “reasonably discrete concentration of artifacts, usually not found in a secondary refuse deposit; in addition, ritual caches generally contain complete artifacts, sometimes unused, that are intact or easily restored”. Archaeologists employ various lines of evidence to distinguish ritual caches from those in which objects were stored for future use. Cached items, for example, may be unsuitable for utilitarian use or intentionally destroyed (Bradley Reference Bradley1982). Both Schiffer and Bradley point out that the term ‘ritual cache’ encompasses multiple types of ritual deposition, including offerings associated with construction episodes and periodic depositions in special locations. These deposition processes may vary over time and space or in relation to one another.

Coe (Reference Coe and Willey1965) observes that while any deposit of hidden objects may be considered a cache, almost all such deposits in the Maya area are ‘ceremonial’. In the following discussion, therefore, the term cache is used to refer to ritual caches only. Coe defines three styles of offering common in the Maya area: dedicatory caches hidden in construction fills or below monuments; terminal offerings deposited on floors, or in shallow, uncovered pits, marking the end of one living surface or building before a subsequent construction fill is laid down; and intrusive offerings cut into surfaces that are still in use. This final style was possibly created on a calendrical cycle. Coe acknowledges that these categories may overlap and that the classification of some caches may be unclear. Both Coe and Becker emphasise that it is impossible to distinguish caches that contain human remains from burials, including human sacrifices. Thus, standard archaeological typologies do not adequately represent the ritual deposition practices of the ancient Maya (Becker Reference Becker, Danien and Sharer1992).

Today, the three categories described by Coe are frequently referred to as ‘caches’ by Maya archaeologists, although the category of ‘termination offering’ is complex. Maya termination deposits often consist of broken artefacts spread over a wide area, and so are not generally considered to be caches (Mock Reference Mock1998; Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Brown and Pagliaro2008; Tsukamoto Reference Tsukamoto2017; Newman Reference Newman2018). Many different activities, however, are labelled ‘terminations’. Some deposits left on floors are more concentrated and more closely resemble nearby dedicatory caches deposited in fills, making it logical to categorise them alongside other ritual caches. Whether cached objects are placed on the previous floor or within the subsequent fill, the ritual deposit marks a construction event. The termination cache, therefore, is common in the Preclassic Maya literature (e.g. Hammond Reference Hammond1991; Awe Reference Awe1992; Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck and McAnany2004). Nevertheless, some archaeologists do not consider any termination deposits to be caches (e.g. Chase & Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Houston1998).

While studies of cache contents and symbolism are common across the Maya lowlands, less attention has been paid to patterns in the styles of cache deposition. Dedicatory and termination caches associated with construction episodes must have held different meanings from periodic intrusive caches deposited in special locations. In addition, the physical process of digging a pit and burying an object differs from placing an object on a floor or in a fill. The present study analyses trends in cache-deposition activities in domestic and public contexts during the Preclassic period (c. 1000 BC–AD 300). Although domestic vs public is often a misleadingly rigid dichotomy, in this case, it is a useful concept. As Pendergast (Reference Pendergast and Mock1998) shows, patterns in caching behaviour emerge when archaeologists differentiate residential platforms from communal plazas—and these patterns shift over time. This study focuses on the site of Ceibal, where both domestic and public spaces dating to the Preclassic period have been investigated. Evidence from Ceibal is compared to published data from other Preclassic, lowland Maya sites, particularly those of northern Belize and the Belize River Valley region. Published reports from these areas provide detailed information concerning Middle Preclassic (c. 1000–350 BC) residential areas. The results contradict a widespread assumption that public rituals developed from domestic rituals.

Preclassic Ceibal

In the Maya lowlands, the Middle Preclassic period is associated with the shift to a sedentary, agriculturalist lifestyle and the adoption of ceramic technology. Throughout this period, a more homogeneous material culture, recognisable as distinctively ‘Maya’, developed across the region and monumental, communal structures were built. The subsequent Late Preclassic period is characterised by increased population, urbanisation and inequality. Maya rulers emerged around the end of the Late Preclassic period (c. 350–75 BC) and the beginning of the Terminal Preclassic (Protoclassic) period (c. 75 BC–AD 300).

Ceibal (previously Seibal) is a large Maya site located adjacent to the Pasión River in south-west Petén, Guatemala (Figure 1). Harvard University's Seibal Archaeological Project conducted excavations at the site between 1964 and 1968 (Willey et al. Reference Willey, Smith, Tourtellot and Graham1975). Although the project focused on Classic-period material, early Middle Preclassic (c. 1000–700 BC) ceramics were recovered from the lowest cultural strata at the centre of the site (Sabloff Reference Sabloff1975). The Harvard Project named this early pottery the ‘Real ceramic phase’.

Figure 1. Map of the southern Maya lowlands, with sites mentioned in the text (figure by J. MacLellan).

From 2005–2016, the Ceibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project investigated further at the site, focusing on the origins of the Maya civilisation. Most of the caches discussed below were excavated by this project. Ceibal-Petexbatun cache identification numbers begin at 101, while Harvard Project numbers begin at one. The site chronology has been refined through ceramic analysis and radiocarbon dating (Inomata Reference Inomata2017; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, MacLellan, Burham, Aoyama, Palomo, Yonenobu, Pinzón and Nasu2017a); all the dates below were calibrated using the IntCal13 curve in OxCal 4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey1995; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2013).

Middle Preclassic period: distinct public and domestic rituals

Plaza caches

Large excavations in the Central Plaza (Figure 2) undertaken by the Ceibal-Petexbatun Project have shown that the foundation of Ceibal involved the carving out of a ceremonial plaza and platforms in the natural, sterile marl soil (bedrock) (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Aoyama, Castillo and Yonenobu2013). These constructions formed an E-Group, a type of Middle Preclassic ceremonial complex found in southern Mesoamerica (Clark & Hansen Reference Clark, Hansen, Inomata and Houston2001; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017). Radiocarbon dates place construction of the first plaza floor at c. 950 BC—at the beginning of the Real 1 ceramic phase (c. 1000–850 BC).

Figure 2. Map of central Ceibal (after Smith Reference Smith1982).

From the creation of the plaza, caches containing greenstone axes and other objects were repeatedly deposited along the central axis of the public space. These public rituals were probably overseen by specialists who had access to Olmec-style greenstone objects and knowledge of similar caching practices within E-Groups at sites in Chiapas and on the Gulf Coast, as well as at the early Maya site of Cival (Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Heizer and Squier1959; Lowe Reference Lowe and Benson1981; Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2006).

The Middle Preclassic caches from the Central Plaza at Ceibal have been described in many publications (Smith Reference Smith1982; Inomata & Triadan Reference Inomata, Triadan, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2015; Aoyama et al. Reference Aoyama, Inomata, Pinzón and Palomo2017a & b; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Pinzón, Palomo, Sharpe, Ortíz, Méndez and Román2017b). A total of 28 Middle Preclassic caches have been identified, including two by the Harvard project (Table 1). Most were found along the east–west axis of the plaza. At least 17 caches were deposited in intrusive pits, five of which were capped by the fill of a subsequent floor. Five dedicatory caches were also placed in the fills below floors.

Table 1. Preclassic caches, Central Plaza (EMP = early Middle Preclassic; LMP = late Middle Preclassic; LP = Late Preclassic; TP = Terminal Preclassic).

Domestic caches

Domestic caches are caches found in residential areas, in or near dwellings. The earliest evidence of occupation at Ceibal is concentrated at the centre of the site (Triadan et al. Reference Triadan, Castillo, Inomata, Palomo, Méndez, Cortave, MacLellan, Burham and Ponciano2017). In addition to the Central Plaza, Real 1-phase material was found at A-24, a large platform to the south-west (Figure 2). At A-24, an earthen platform was constructed in the earliest phase occupation at Ceibal. During the Real 2 phase (c. 850–775 BC), the platform supported superstructures, possibly domestic, and two early Middle Preclassic caches (caches 127 and 131) found here may have come from domestic contexts (Table 2). These caches were deposited within the fills of successive floors of a superstructure on the Real 2-phase platform (Inomata & Triadan Reference Inomata, Triadan, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2015). Excavation identified no intrusive pits associated with either cache. Cache 127 contained three greenstone axes, while cache 131 contained a greenstone axe preform or pseudo axe. These are the only greenstone axes found in a potentially residential context at Ceibal.

Table 2. Preclassic caches in residential contexts (EMP = early Middle Preclassic; LMP = late Middle Preclassic; LP = Late Preclassic; TP = Terminal Preclassic).

Early house platforms were found below the East Court to the north-east of the Central Plaza (Figure 2; Triadan et al. Reference Triadan, Castillo, Inomata, Palomo, Méndez, Cortave, MacLellan, Burham and Ponciano2017). Here, the earliest structure is a possible house platform carved from the natural marl and dated to the Real 3 ceramic phase (c. 775–700 BC). Later in the same phase, this structure was covered by a larger platform that supported a residential patio group. Two caches from the East Court date to the Real 3 phase (Table 2; Inomata & Triadan Reference Inomata, Triadan, Golden, Houston and Skidmore2015; Triadan et al. Reference Triadan, Castillo, Inomata, Palomo, Méndez, Cortave, MacLellan, Burham and Ponciano2017): cache 156 was deposited on a floor next to the earliest house platform structure, while cache 133 was found in the fill of a later floor. Each cache contained one ceramic plate. Two further caches at the East Court date to the late Middle Preclassic period (c. 700–350 BC). Cache 129 comprises three stone spheres placed in a triangle, or hearth shape, on a floor. Cache 123 was deposited in the fill of a platform and included 11 notched obsidian blades (Aoyama et al. Reference Aoyama, Inomata, Triadan, Pinzón, Palomo, MacLellan and Sharpe2017b).

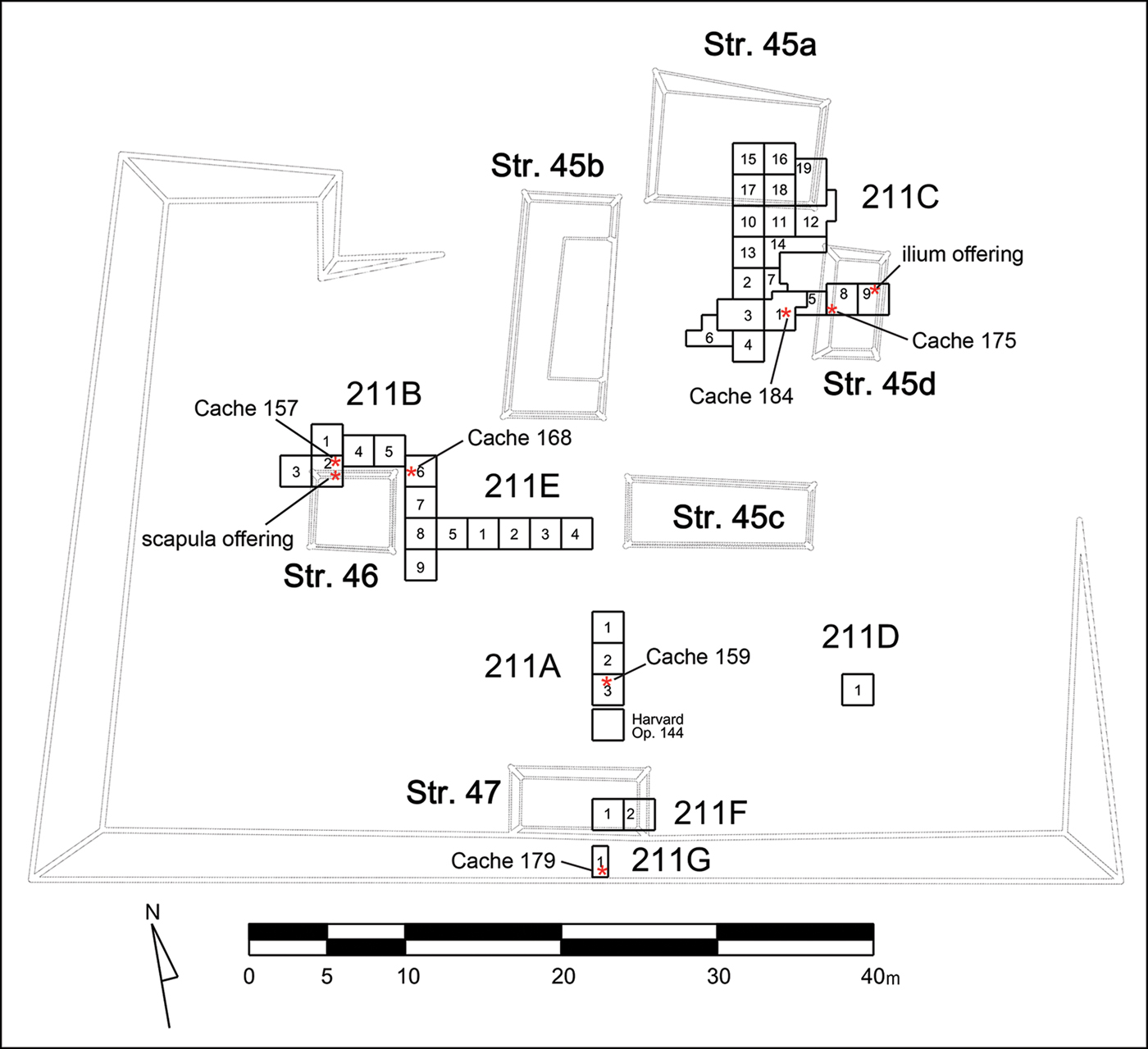

The Karinel Group is a residential platform located 160m west of the Central Plaza (Figure 2). Tourtellot (Reference Tourtellot1988: 171–74) investigated the group during survey of Ceibal's periphery and found early Middle Preclassic ceramics. Due to its early occupation, relatively shallow overburden and proximity to the centre of the site, the Karinel Group was an ideal location for the Ceibal-Petexbatun Project to investigate large areas of Middle Preclassic domestic activity, and four seasons of fieldwork were undertaken here between 2012 and 2015 (Figure 3; MacLellan Reference MacLellan2019a & Reference MacLellanb). The earliest evidence of occupation at the Karinel Group dates to the Real 2 phase, with the earliest residential structures dating to the Real 3 phase (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan, Triadan, Munson, Burham, Aoyama, Nasu, Pinzón and Yonenobu2015a). Two late Middle Preclassic caches were also excavated here (Table 2). Cache 157 contained a large fragment of a ceramic plate, an obsidian blade and an obsidian flake core (Figure 4; Aoyama et al. Reference Aoyama, Inomata, Triadan, Pinzón, Palomo, MacLellan and Sharpe2017b). Worked bone and turtle shell were found in the fill around the cache, and may have been part of the same ritual deposit. Cache 157 dates to the Escoba 2 phase (c. 600–450 BC) and was deposited on the surface of a platform and covered by the fill of the next construction event. Another deposit that included a human scapula and large ceramic sherds was placed in a wall of an Escoba 3-phase (c. 450–350 BC) platform during its construction.

Figure 3. Excavation units and cache locations, Karinel Group (after Smith Reference Smith1982).

Figure 4. Cache 157 and its location (photographs by T. Inomata).

Late and Terminal Preclassic periods: a shift to more similar ritual practices

Domestic caches

At the Karinel Group, the earliest intrusive caches were deposited into a patio floor c. 350 BC, at the transition to the Late Preclassic Cantutse ceramic phase (Table 2). Cache 175 contained a complete ceramic vessel (Figure 5). Another pit yielded a single human ilium. The deposits that contained the scapula and ilium were not labelled caches during excavation, but are considered domestic caches here (Table 2).

Figure 5. Cache 175 (photograph by J. MacLellan).

Other caches at the Karinel Group date to the Terminal Preclassic period. Cache 184 comprises a ceramic vessel in an intrusion into a patio floor. While the exact chronology of this deposit is unclear, it dates to the end of the Cantutse phase or the Terminal Preclassic. Cache 159 was deposited into a pit cut into the floor in front of domestic temple structure 47 during the Xate 1 (c. 75 BC–AD 50) or Xate 2 (c. AD 50–125) ceramic phase (Figure 6). The intrusion reached the natural bedrock, upon which 18 ceramic vessels were placed, rim to rim. The cache also included an obsidian blade and two small limestone discs. A burial (burial 138) of a child was found immediately above, within the fill of the intrusion. The 18 vessels in cache 159 were poorly fired and not durable enough for everyday use, suggesting that they may have been manufactured specifically for the purpose of caching. Cache 159 resembles the Terminal Preclassic ceramic vessel caches in the Central Plaza.

Figure 6. Cache 159 (photograph by T. Inomata).

Cache 168 (Figure 7) was cut into an exterior floor at the Karinel Group and subsequently covered with a layer of rocks. The shallow pit contained 20 small, polished stones that may have been collected from a river. Kazuo Aoyama (pers. comm.) identified 11 as black shale and nine as sandstone. This number of polished stones is intriguing, as 20 is the base of the Maya counting and calendar systems. Cache 168 also contained two limestone spheres, chert flakes and animal bone and shell. Ashley Sharpe (pers. comm.) found mostly riverine species, including crocodile (Crocodylidae), unidentified fish, turtle (Dermatemys mawii and unidentified), river clam (Unionidae) and jute snail (Pachychilus sp.). A marine olive snail (Oliva sp.) shell, a jaguar (Panthera onca) or puma (Puma concolor) phalanx, an opossum (Philander opossum) humerus and deer (Odocoileus virginianus and Mazama sp.) bones were also identified. The olive snail shell, a fragment of turtle shell and an unidentified flat bone fragment were worked. Ceramic sherds from this context date to the Junco 1 phase (c. AD 200–300).

Figure 7. Cache 168 (photograph by J. MacLellan).

Cache 179 was found near the southern edge of the Karinel Group, on the bedrock surface. It consists of a small ceramic vessel dating to the Junco 1 phase. Although no intrusion was detected, placement of the cache must have removed earlier material from the bedrock.

Plaza caches

Four Late Preclassic and 21 Terminal Preclassic caches were identified at the Central Plaza of Ceibal (Aoyama et al. Reference Aoyama, Inomata, Triadan, Pinzón, Palomo, MacLellan and Sharpe2017b; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Pinzón, Palomo, Sharpe, Ortíz, Méndez and Román2017b; Table 1). All were placed in intrusive pits, with two Late Preclassic cache pits (101 and 116) being capped by construction fill. Ceramic vessels were the most commonly cached item in the Central Plaza during this era.

Interregional comparisons

It is unsurprising that few Middle Preclassic caches have been found in residential areas at Ceibal, as such deposits are rare throughout the lowlands. At K'axob, Cuello and Altun Ha in northern Belize, for example, no caches pre-date the Late Preclassic (Hammond Reference Hammond1991; Pendergast Reference Pendergast and Mock1998; Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck and McAnany2004). Similarly, no caches were found in the Middle Preclassic domestic platforms excavated at the Altar de Sacrificios site, located near Ceibal (Smith Reference Smith1972).

A few Middle Preclassic caches have been found in association with house platforms in the Belize River Valley. At Cahal Pech, in the lowest levels of Plaza B, Awe (Reference Awe1992) identified a small number of early Middle Preclassic caches. These comprised artefact clusters left on surfaces or placed within construction fills. Additionally, a crocodile mandible was recovered from below a Cunil house floor (Awe Reference Awe1992: 327, 331, 339–34; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Awe, Garber, Brown and Bey2018: 99). At Blackman Eddy, a partial ceramic vessel and marine shell fragments were deposited on the floor of an apsidal house platform during the end of the early Middle Preclassic or the beginning of the late Middle Preclassic period (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Awe, Garber, Brown and Bey2018: 100). At the Cas Pek Group at Cahal Pech, multiple late Middle Preclassic deposits have been interpreted as caches. Cache 95-1, for example, was found below a large platform, placed on the bedrock (Lee Reference Lee, Healy and Awe1996: 85). It comprised ceramic sherds and an obsidian blade fragment. Caches 95-2 and 94-1 were placed on structure floors and contained partial ceramic jars (Lee & Awe Reference Lee, Awe, Healy and Awe1995: 107; Lee Reference Lee, Healy and Awe1996: 85), while cache 94-3 was found within the fill of an interior floor of a residential structure, and contained a partial ceramic jar and an obsidian blade broken into three pieces (Lee & Awe Reference Lee, Awe, Healy and Awe1995: 107). At Chan, late Middle Preclassic cache 6, containing a single jade ornament, was found under the earliest floor of a residential platform (Kosakowski et al. Reference Kosakowsky, Novotny, Keller, Hearth, Ting and Robin2012). Multiple contemporaneous caches were also placed in the centre of Chan's public plaza. Unlike cache 6, however, these caches were found in intrusive pits that cut into one another. The Chan plaza caches therefore exemplify repetitive caching in a special location, in contrast with caches associated with construction events.

At Ceibal as well as the Belize River Valley sites, none of the Middle Preclassic domestic caches were found in defined, intrusive pits. Rather, these deposits represent dedications (found in fills or under floors) and terminations (found on floors) of buildings. Complete ceramic vessels rarely feature in Middle Preclassic caches.

Throughout the lowlands, caches in domestic areas became more common during the Late Preclassic period. Some are intrusive and many include whole ceramic vessels. The earliest cache at K'axob, for example, was created during the early Late Preclassic period, when a ceramic vessel was deposited in a pit dug into an interior house floor (Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck and McAnany2004). Throughout the Late and Terminal Preclassic periods, residents of K'axob continued to cache objects in domestic areas. Most of these caches contained ceramic vessels and were placed in pits, although others were placed on floors and in construction fills. Some of the intrusive caches overflowed the pits and protruded into the subsequent construction layers (Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck and McAnany2004).

Discussion

As Bradley (Reference Bradley2005) observes, public ceremonies often grow out of domestic, subsistence-oriented practices. In the Maya lowlands, caches are sometimes used as an example of how public rituals derive from domestic predecessors (e.g. Lucero Reference Lucero2003). Empirical data, however, show that caches were rarely deposited in residential areas during the Middle Preclassic period. When caches are identified in early domestic areas, they are invariably associated with construction episodes and are not found within intrusive pits. Some of these deposits, particularly the terminations, would not be considered to be ‘caches’ by all archaeologists. In contrast, the Middle Preclassic caches in public spaces were normally placed in intrusions and are rarely associated with construction episodes.

One aspect in which Middle Preclassic domestic and plaza caches differ is in the timing of their depositions. The domestic caches coincide with construction projects; the dedications and terminations “mark transitional stages in the life of a structure” (Garber et al. Reference Garber, Driver, Sullivan, Glassman and Mock1998: 125). Halperin (Reference Halperin2017: 530) argues that such “critical events in the lifecycle of Maya households […] disrupted the habitual routine of daily life to allow ancient people to reflect on their lives, and thus provided moments to either reproduce existing practices or shift course”. There is no evidence that houses were rebuilt following a specific calendar; rather, major alterations to early residences might be due to the developmental cycle of domestic groups (Goody Reference Goody1958), or other concerns. In contrast, the repetitive nature of caching in plazas may indicate adherence to a ritual calendar. Middle Preclassic E-Groups probably functioned as imprecise solar observatories, designed to mark the solstices and equinoxes (Aveni et al. Reference Aveni, Dowd and Vining2003; Aimers & Rice Reference Aimers and Rice2006; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Chase, Dowd and Murdock2017). It is plausible that the caches deposited along the east–west axes followed a solar calendar, connected to the agricultural cycle. As others have hypothesised, the placing of greenstone axes in pits could metaphorically represent the planting of maize (Taube Reference Taube, Clark and Pye2000; Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2006). The E-Group and axe caches also indicate interactions with regions outside the Maya lowlands, including Chiapas and the Gulf Coast (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Aoyama, Castillo and Yonenobu2013). These connections shaped Middle Preclassic communal rituals, but do not seem to have affected domestic ritual in the same ways.

The Middle Preclassic caches from Ceibal show that while public ritual may indeed have related to subsistence, separate domestic and ritual systems began to develop as early as the shift to a sedentary lifestyle (Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, MacLellan and Burham2015b). The relationship between domestic and public rituals shifted at the transition to the Late Preclassic period, when intrusive caches—predominantly comprising ceramic vessels—became common in both contexts. Simultaneously, ceramic figurines, which are considered to have been used in domestic rituals, became rare, and temple-pyramids were built in outlying residential groups for the first time (Ringle Reference Ringle, Grove and Joyce1999). Broadly, public and domestic rituals became more similar (Burham & MacLellan Reference Burham and MacLellan2014).

It is important to remember that the term ‘cache’ is a creation of archaeologists, and we cannot expect it to reflect accurately the ways in which ancient, non-Western groups understood their own actions. While classifications facilitate our analyses, archaeologists may inadvertently combine distinct sets of ritual practices by grouping together many different kinds of deposits as caches. By focusing on the act of deposition, the dedicating and terminating of constructions can be distinguished from the repeated digging of cache pits in certain spaces. This distinction may better represent emic classifications of ritualised behaviour, and it raises new questions about the significance of caches. The variation and transformation in Preclassic deposition practices at Ceibal encourage further research into the roles of domestic and communal rituals in the development of complex societies.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (BCS-1518794) and the Alphawood Foundation. Additional support was provided by Dumbarton Oaks and the University of Arizona (School of Anthropology, Graduate and Professional Student Council, Social and Behavioral Sciences Research Institute). Permits were granted by the Instituto de Antropología e Historia, Guatemala (29–2009; 25–2013; DGPCYN-12-2014). Thanks to Takeshi Inomata, Daniela Triadan and the Ceibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project members. Samantha Fladd and anonymous reviewers provided comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. No conflicts of interest affected this research.