Gustavo Grandal Montero (ALJ): Could you give an overview of the main aims and context of the project?

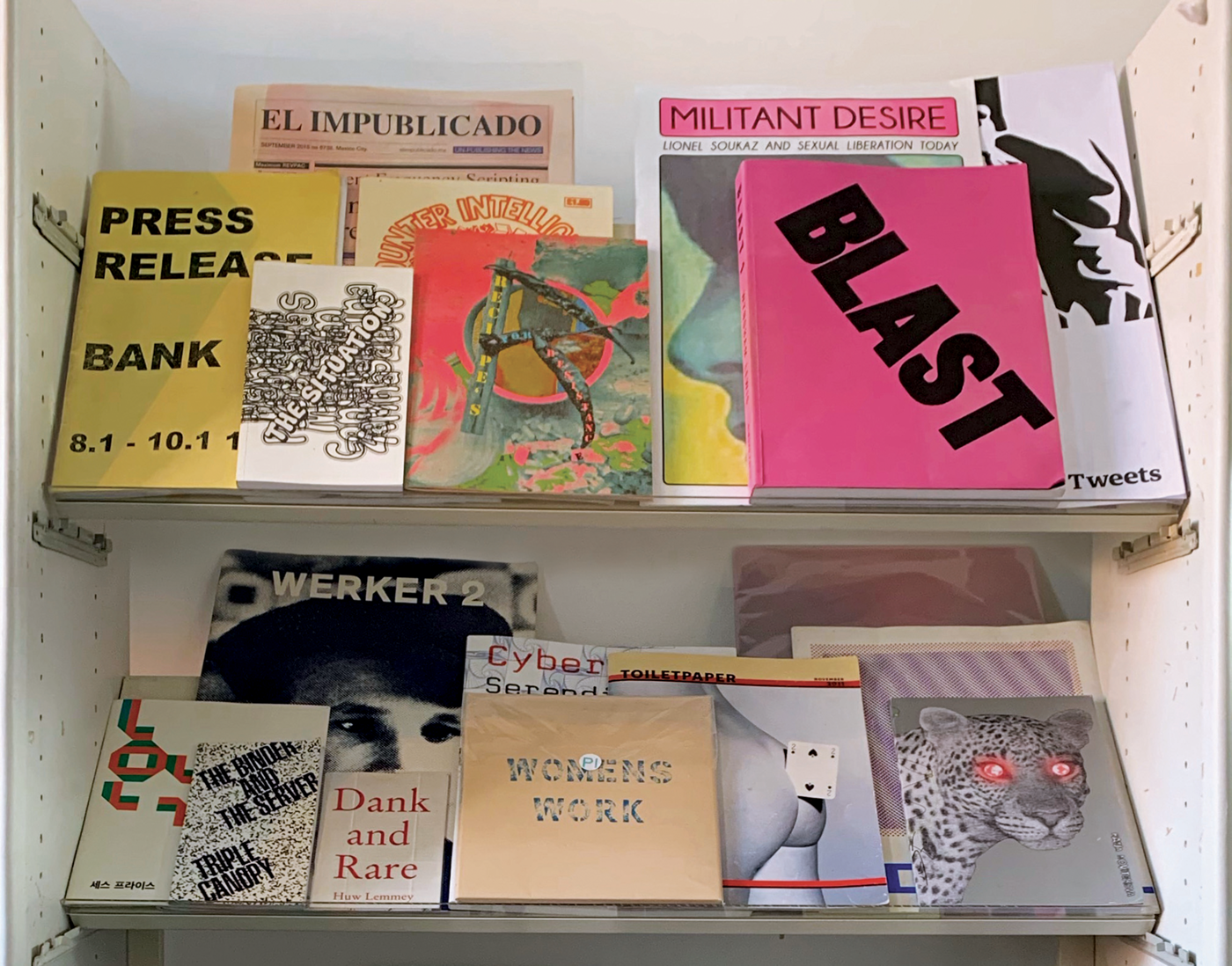

Ami Clarke (AC): The Digital Archive of Artists’ Publishing (DAAP) is an interactive, user-driven, searchable database of artists’ books and publications, that acts as a hub to engage with others, built by artists, publishers and a community of creative practitioners in contemporary artists’ publishing, developed via an ethically-driven design process, and supported by Wikimedia UK and Arts Council England. The project is inspired by the site of Banner Repeater's public Archive of Artists’ Publishing on Hackney Downs train station, with 11,000 people passing a day, in response to the need for a similarly dynamic approach to archiving in an online context.

Central to how Banner Repeater operates is our location, with a gallery, a bookshop and an archive deliberately sited within the ebb and flow of the commuting public, enmeshed within the public transport networks in a busy thoroughfare of passing traffic, in order to distribute excellent art and artists’ publishing directly into a main artery of the city of London. Networked strategies underpin everything we do, pioneering a hybrid way of working in contemporary critical art practice through the strong symbiosis between precedents set via experiments in text and publishing held in the Archive, and artistic practices engaging in networked strategies today.

Publishing is particularly interesting in this regard, as it developed alongside technological advances throughout history. Textual productions over time, tend to reveal how they inflect, as well as contain, traces of the ‘subject’ - that's me and you - emerging in synthesis with their environment: that includes the means of production, and distribution, at any given time in history. A subjectivity that emerges through market relations, and in a present-day context, that means Twitter, Tik Tok, Instagram, Facebook and so on, enmeshed within the protocols of platform/surveillance capitalism. If it's free, you are the product. Artists’ publishing, both historically, and in the current context, blurs the lines between publishing and broadcasting, via social media and other networked connectivities, helping to make visible through experimentation, ideas of this sort, regarding the ‘copy’, questions of authorship, intellectual property, copyright, and the constitution of a ‘reading public’, the dynamics of which have never been more pertinent to democracy than today. Technology has a tendency to draw out like a poultice existing biases and discriminations in the world precisely because of this ludicrous notion of neutrality, when in actuality it privileges a predominantly white, western, male perspective. It is humans who design software and interact and engage with it through very specific dynamics, that include the highly exploitative practices of capitalism, often predicated upon extractive relations that can be traced to colonial times. Unsurprisingly, unless you take account of these power dynamics, tech, when thought of as ‘neutral’, has a tendency to amplify existing systemic violences.

Fig. 1. Public archive at Banner Repeater.

Back in 2010, I set up a basic system of cataloguing the material in the archive, but it soon became clear that this was a completely inadequate response to something that should be as lively as the Archive on the platform. About four years ago Arnaud Desjardin and I started to talk about what would amount to something worth having of a digital sort, for a rapidly growing community in artists’ publishing. And then, as luck would have it, I began a long conversation with Lozana Rossenova after several visits to Banner Repeater that started from a shared interest in artists’ publishing and a critical engagement with technology, which brings us to where we are today with the benefit of her great expertise.

Lozana Rossenova (LR): With this project, we quickly established how the characteristics which distinguish artists’ publishing from other more conventional forms of both art making and book publishing, pose multiple challenges to traditional content management, archival and collection management systems. Drawing on my research and design-oriented work with digital archives, one of the main aims of the project became the adoption of new developments in linked open data and open source software in order to address some of these challenges and develop ways of describing artists’ publications in structured, machine-readable data formats.

Interest among cultural heritage institutions in the potential uses and application of linked open data for cultural collections management has been growing steadily over the last few years. While the benefits of adopting linked open data are widely recognised, adoption has been slow for most institutions. However, the release of the open source WikibaseFootnote 1 software opens new opportunities to start working with linked dataFootnote 2.

Even with some of the technical barriers removed, the larger question as to how to model and express cultural data as linked data remains open, particularly within specific fields which require the direct input of subject specialists in order to develop meaningful models. Existing standards like the CIDOC-CRM (developed by the International Council of Museums, ICOM) and FRBR (developed by IFLA) present useful models for cultural heritage objects and traditionally-published books, however these are not always flexible enough to accommodate the needs of contemporary artistic practices. With the DAAP project, we aim to gather scholars and practitioners in the field of art, artists’ publishing and creative technology in order to set a precedent for modelling bespoke and non-standard art publications as linked data.

ALJ: At what stage of development are you currently? What are the next steps?

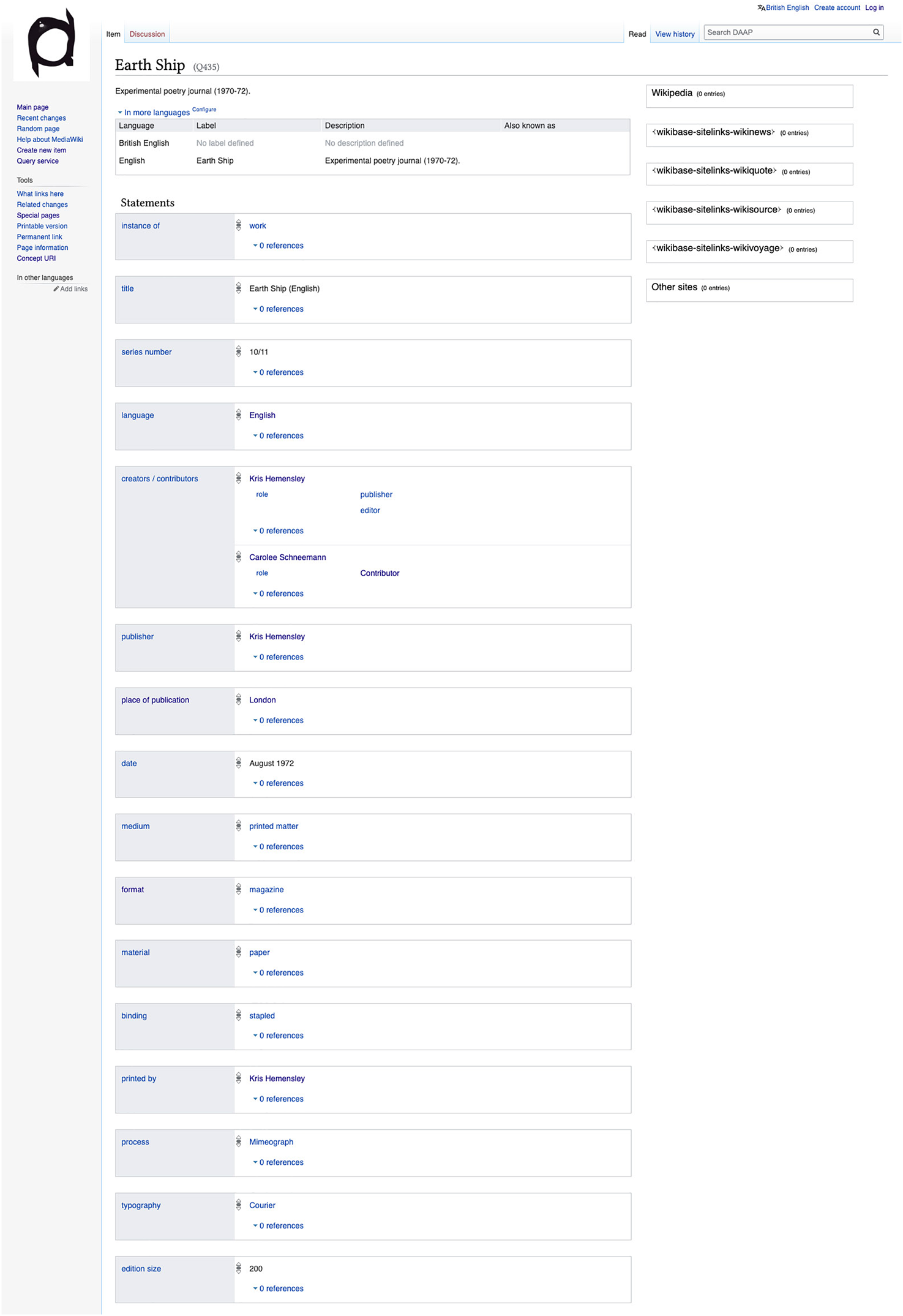

LR: We have deployed a custom instance of Wikibase to store and manage the DAAP data. DAAP's installation of Wikibase benefits from the technical affordances of the Wikimedia Foundation's public platform Wikidata, including: storing structured data; using a flexible linked-data-compliant model for developing bibliographic data about publications; capacity for multiple users to contribute to the database; version control; and, sophisticated querying options and visualizations provided via Wikidata Query Service tools.

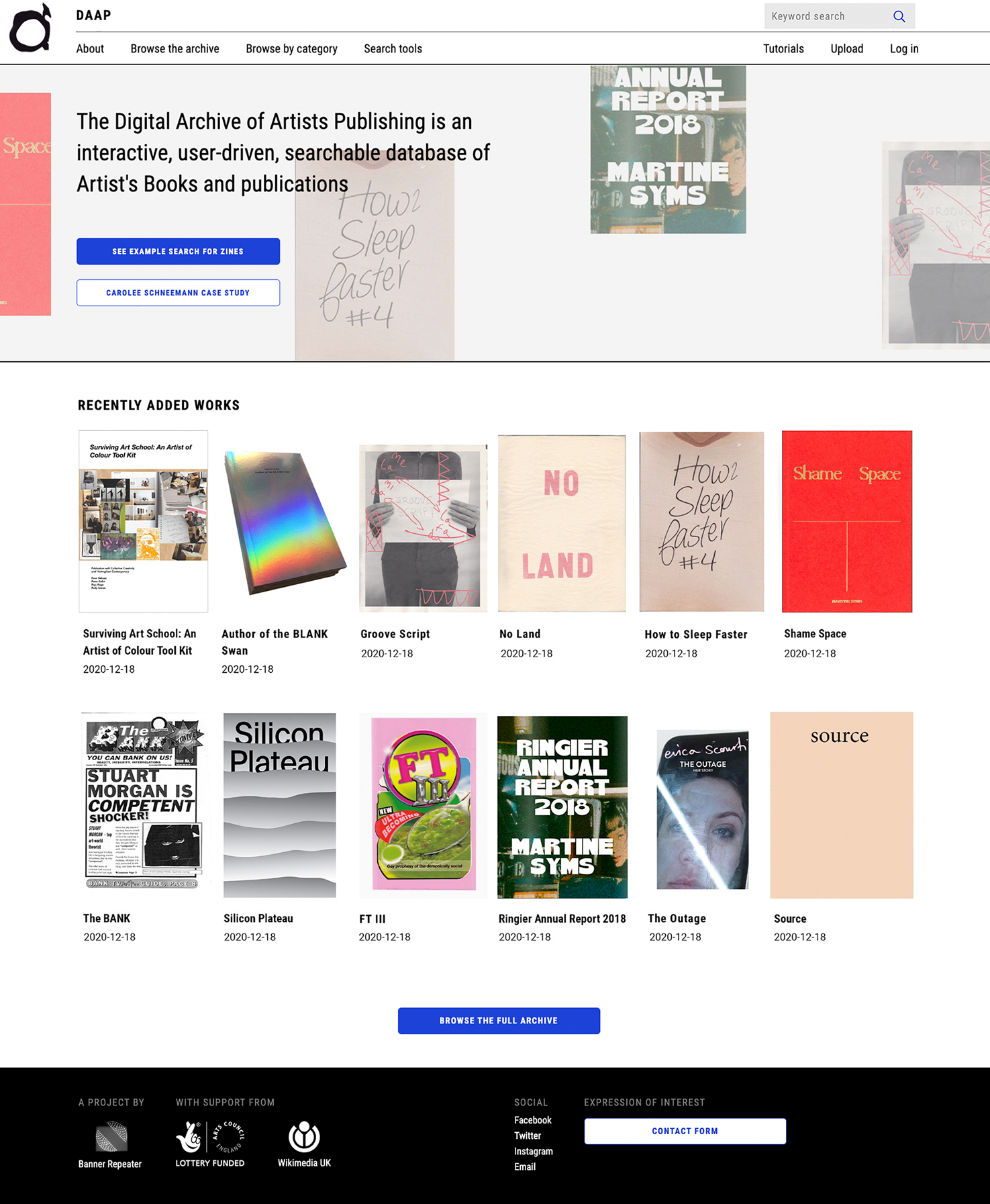

We have also developed a custom frontend interface on top of the Wikibase database, which follows familiar user interface metaphors, increasing accessibility across a broader audience.

Fig. 2. View of the homepage of the DAAP frontend portal.

Both the backend database and the frontend interface draw on the flexibility and richness of the linked open data model we developed with our collaborators during workshops and community discussions. The applicability of the model to the unique requirements of artists’ publishing has been tested in several ways throughout the development of the project by structuring and uploading the bulk of the Banner Repeater archive (over 800 publications) into the database; by working with a diverse range of workshop participants to upload their own materials following the DAAP model; and, finally, by working on a dedicated research case study with curator and archivist Dr. Karen Di Franco, which uses the database to record a selection of seminal publication materials by artist Carolee Schneemann.

In terms of next steps, we plan for continuous improvement of the functionalities of both backend and frontend, in line with the community development of the open source software.

AC: Crucially, collaborating with other cultural organisations, archives and individuals is vital, and we are keen to help facilitate the upload of materials from other archives, publishers, and distributors that may benefit from the increased inter-connectivities that DAAP can provide as a resource and research tool, as well as point of exchange. It's not meant to be Banner Repeater's archive.

ALJ: What is different about this project? How does it relate to existing online catalogues or digital collections of artists’ publications in libraries, but also galleries, bookshops, etc.?

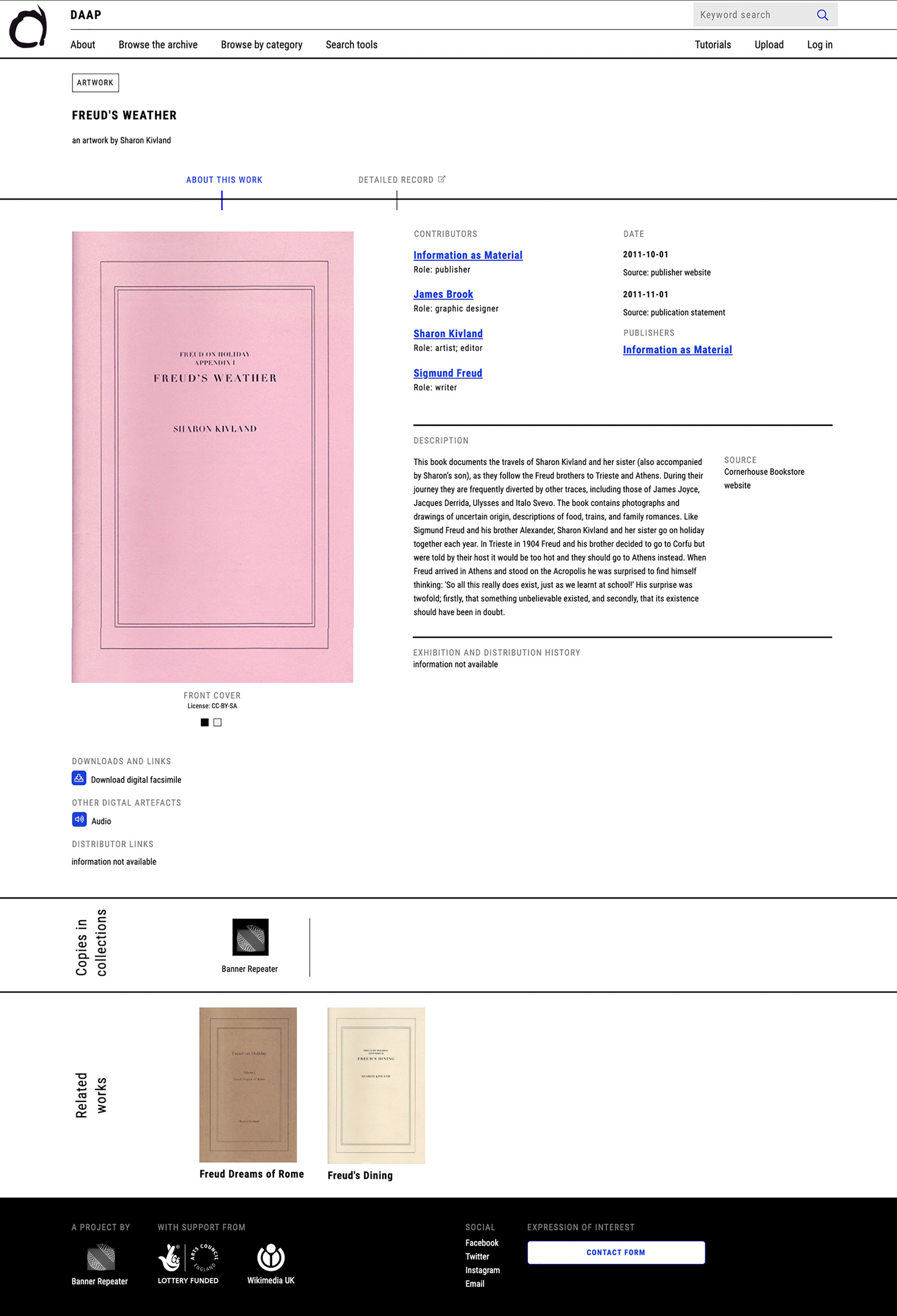

Fig. 3. View of the artwork record page template in the DAAP frontend portal.

AC: We tried to emphasise inclusivity from the start, privileging anecdotal histories and multiple perspectives alongside factual data. The wiki style approach was central to this, and means that users can upload their own material, single items, or entire collections, choosing appropriate sharing permissions at time of upload. Entire collections can sit next to one another, with integrity. Utilising a linked open data environment, DAAP also brings to the surface new and unexpected data connections across diverse collection artefacts, providing a resource to link to other archives, and communities, whilst visualisation tools offer new possibilities of conducting research with data on artists’ publications.

LR: A linked data database enables data to be structured in flexible ways, which can grow and develop organically around community needs, rather than conforming to rigid, pre-existing bibliographic standardsFootnote 3. Traditional standards aim to structure bibliographic data in ways that make it possible to find publications online, but this is not all that this project aims to achieve. Due to its independence from larger linked data platforms like Wikidata, DAAP can also serve as a space for more open experimentation, where data is modelled and tested within an active user community.

Fig. 4. View of the artwork record page template in the DAAP backend database.

AC: As discussed, technology is anything but neutral, with an active tendency to reproduce existing biases and discriminations already existing in the world today. How search criteria, and other structural aspects of archiving contribute to this, is an ongoing conversation that drives the development of the archive, drawing from the experiences of users, archivists and technologists. DAAP is deeply committed to challenging the politics of traditional archives that come of issues regarding inclusion and accessibility, from a post-colonial, critical gender, anti-ableist and LGBTQI perspective.

The native features of the linked data environment have been activated within a communal practice, in order for the project to support an equitable, and ethical design process throughout the archive development. This, in itself, is a vital and ongoing conversational process, in which mistakes can be made, discussed and rectified. Workshops have facilitated much of these conversations so far, with a host of users, as well as experts, joining in discussion and debate, which will continue as the archive continues to grow.

LR: The project remains connected to a broader ecosystem of other archives, publishers and distributors by allowing a range of website links and external database identifiers to be added and represented within the main record for every item in the archive. In addition, collectors, publishers, and distributors can create separate records for the individual copies they have in their collections, and easily link these records to the main artwork, as well as all other copies recorded in the database.

There is also a growing adoption of Wikimedia software across the cultural heritage field, and libraries more specifically. Pilot projects testing the feasibility of Wikibase for managing classical bibliographic data have been conducted by the OCLC, the German and French National Libraries, and other large institutionsFootnote 4. It seems likely linked open data databases, including Wikibase, will become more widely adopted across libraries and archives in the near future.

ALJ: Expertise and community are values central to this project, and you are working closely with Wikimedia UK and supported by the Arts Council. Can you give us a bit of background about yourselves and the project, and how these partnerships developed?

AC: I teach, and I'm an artist and writer interested in working within the emergent behaviours that come of the complex protocols of platform capitalism in everyday assemblages, with a focus on the inter-dependencies between code and language in hyper-networked culture. My work is often driven by critical concerns regarding technology and how precedents in publishing provide us with many insights into the complex human/tech entanglements of today. As such, I'm interested in acknowledging, and thinking through the complexities of the subject emerging in synthesis with their environment from a critical position, that questions the humanist project for only ever having privileged some humans, over others. Similarly, throughout the arts programme at Banner Repeater there's been a tendency towards work that speaks about this human enmeshment with technology, as multi-media assemblages that act as sites of affective experimentation and as a means to consider what might amount to ‘criticality’ within our accelerating technicity. Expertise that comes of experience within experimental artists’ practice, is highly valued in this instance, and in fact, vital, in my mind, to be able to deal with the complexities of today. What constitutes the ‘we’ of community, also comes about through working practice as an ever-changing constitution. An important aspect of the database was to make it possible to include everyone sat at that kitchen table back when the ideas began to flow, by making it possible to self-identify as you wish, and include a vast array of roles not usually considered worthy of inclusion.

Questions of access, privilege, and the rights to knowledge, are exemplified by the flame wars online, amidst the distracting cries of ‘fake’ news, with access to knowledge a key driver for social and economic development as Wikimedia, Hannah Arendt and Mercedes Bunz, all attest.

Shoshana Zuboff's fieldwork, today, shows how the new knowledge territories emerging alongside the capacity to analyse processes and behaviours, also result in political conflict over the distribution of knowledge, as surveillance capitalists declared their right to know, to decide who knows, and to decide who decidesFootnote 5. In my mind, DAAP is working through some of these challenges, in some small way, asking urgent questions about how to build software/platforms better - for the user - that question what a top down ‘community’ platform such as Facebook, amounts to, that serves simply to harvest value in the form of likes and behavioural data analysis, that has proven to be so divisive.

LR: My own background is in graphic and digital design and communication. The development of the technical infrastructure of DAAP draws heavily on my PhD research work conducted at digital arts organization Rhizome, who have been using Wikibase as archival platform since 2015Footnote 6. My PhD work developed the data model and user experience for Rhizome's archive of net art, the ArtBase. While the two are distinct art forms, describing net art metadata shares many of the challenges of describing non-standard artists’ publications. The methods around data modelling I developed as part of my PhD practice, in particular, have been influential in my work on the DAAP, as well. For example, thinking through non-hierarchical relationships between different collaborating agents, or the non-binary relationship between an artwork and its various manifestations and versions—and how to express that as linked open data—are some of the questions explored in my PhD thesis, which is due to be published in 2021. Prior to starting my PhD, I was also engaged with contemporary publishing practices through various projects, and for the past few years I have been teaching a course on hybrid publishing to MA design students at the University of Reading.

AC: We were fortunate to be supported by an Arts Council England grant with further support from Wikimedia UK, that meant that the arts programme that accompanies the build of the archive has allowed us to think through archival practices with other practitioners such as artist and educator Raju Rage. Their work, ‘Under/Valued Energetic Economy’: a term inspired by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, informed the title for the installation, and work in progress at Banner Repeater, that maps out the tangled ecology between ‘activism’, ‘arts’ and ‘academia’. We worked with Raju to try and develop a way that DAAP could be made useful, as an online resource, with conversations that began through group workshops, and continues as an ongoing discussion. Other practitioners have joined us via the public workshops over the last two years, which are now primarily online, of course, which in some ways, reveals how apt the platform could become, facilitating conversation and exchange across geographical distance.

We were also able to draw upon the expertise of several specialists in their respective fields that have contributed to the Banner Repeater programme over the years, such as: Arnaud Desjardin of The Everyday Press and author of The Book on Books on Artists' Books; Gustavo Grandal Montero, librarian and researcher at UAL; and curator and digital archivist Dr. Karen Di Franco who produced Book Works digital archive. The artistic team is also joined by historian, archivist and writer Frances Whorrall-Campbell and artist Cicilia Östholm, co-initiator of equal voices in the room?, who addresses bias and inequality through technological intervention, to undermine dominance and hegemonies based on gender binaries and the Western canon. Serious contributions, often spanning quite long periods of time, especially during Covid, have been made by several volunteers who generously contribute their time to Banner Repeater, such as Charlie Pritchard, Ariel Finch, Amelia Claringbull, Louise Rutledge, and Nína Óskarsdóttir and Maša Škrinjar, who were kindly funded by an Erasmus scheme in 2016.

LR: The rest of the technical team on the project includes VariaFootnote 7 member Julie Boschat Thorez, as lead developer, and Dutch designer Paulien Hosang as lead on the design of the visual interface of the archive. I have worked with Julie and Paulien on numerous projects in the past and the synergy of shared values and an extended network of collaborators in digital art and technology has been very important in this project.

As part of my PhD research, I also worked to establish meaningful connections with the community of users and developers working on the Wikimedia software ecosystem. My main contacts were in Wikimedia Deutschland, which is the Wikimedia chapter most actively engaged in the development of the software. Through the international network of the Wikimedia Foundation, we got connected with their UK chapter.

AC: The DAAP is the first use-case of Wikibase in the UK, I believe. Wikimedia UK are committed to the development of open cultural initiatives, and hence interested in supporting our efforts, and have kindly co-facilitated the training workshops with local practitioners, which has been really important. It's been interesting getting to know what they do better, as well as getting to see what their software is capable of, with some very interesting diagrams that can visualise, beautifully, in my mind, the interconnectivities across a wide range of items in the database. I find them fascinating as diagrams as they capture something that's actually quite hard to show otherwise, as non-hierarchial clusters of associations.

We are also looking forward to working with several new international partners that include Asia Art Archive and their extensive network, as well as artists publishers in Mexico City, with a huge wealth of activist and artists’ publishing, amongst many others. Anyone participating in the landscape of artists’ publishing is welcome to join our user community as active collaborators and stakeholders.

ALJ: As mentioned, you are interested in representation and inclusion, and the project is being developed by a large team in collaboration with external participants, using workshops as a method of achieving this. Can you describe your working processes and the reason why these are an important part of the DAAP?

AC: Many problems regarding the digital realm coalesce also in ethical problems central to archiving, such as biases which may be explicitly or implicitly embedded in database and archive infrastructures. During the development of the archive it was important to be in discussion with various practitioners who shared an interest in interrogating archival practice, and we were very fortunate to work with Raju Rage, and fellow attendees of workshops facilitated alongside members of our technical and artistic teams. Key to the development of DAAP has been this ongoing conversation enabled via workshops between the users of archives, whether archivists or artist publishers, and the team, that has meant that discussions held during workshops have informed the design and development of the archive's infrastructure and interface.

LR: We developed three phases of workshops. First, an expert phase where we worked closely with our advisors to develop an initial draft of the data model for the archive. Second, an open phase where we ran workshops that anyone could sign up for, initially in person in London, and later moving online (due to Covid-related restrictions). During this phase we worked with a broader range of users who could test the system and share their feedback, questions, concerns. Third, participants from the open workshops were invited to follow-up, closed sessions where we could collectively explore more advanced features of the system and address specific difficult questions around case studies presented by the participants, e.g. serial publications with unconventional sequencing, or works with complex relationships of influence and derivation, that cannot simply be described as new editions.

This focus on an iterative, participatory methodology allowed the inclusion of multiple voices and concerns, which helped flesh out potential biases and assumptions that the technical team or data modelling team at times attached to specific elements of the information architecture. By involving users with the technical setup of the database, and not just polished frontend visuals, users could directly intervene in the workings and possible failing of the design-in-progress.

ALJ: Could you describe the key features of planned functionality, particularly searching and browsing?

LR: I already mentioned some of the key features around data storage and organisation facilitated via the Wikibase software. These core features also make possible some new functionality, not typically encountered in archival or collection management software. Search is currently possible via two pathways: a standard keyword search box which searches through the whole database for plain text matches; and also a second interface for advanced search, which is fundamentally different from the familiar facets in most traditional database systems.

At the moment, search interfaces to linked data remain a challenge to users (and designers). On the one hand, they use unfamiliar interaction patterns: searching for links across data items based on multiple variables (rather than fixed facets). On the other hand, they do not afford the full flexibility of manually coding a search request in a query language. Still, these interfaces are constantly being developed and improved, and users can be trained on best practices in interacting with them.

The results of pre-programmed queries can be embedded into web pages, which users can more easily interact with and navigate. For instance, the frontend interface offers users to browse lists of items structured by creator, or publisher, or another set of variables. More complex lists, such as related works based on creator, publisher, or format can also be presented as a browsable interface driven by a set of dynamic queries to the database. The visualizations of these lists do not have to be tabular or grid-like, but can take a variety of forms made available via the advanced search toolkit. These can include graphs, or dimension diagrammes, and more.

ALJ: How are you approaching the design of the interface, and data visualisation more generally?

AC: The design of the interface has been developed over a long period, with sketches done by myself, initially, and then more detailed work by Lozana, Julie and Paulien.

LR: We are taking a flexible approach which responds to conditions in the field. Working with open source software involves being attuned to developments in the community maintaining the software, knowing where priorities lie for future feature development, and what aspects of the software should not be customized in order to avoid future incompatibility issues. For example, we have not modified the default interface for logging into and working with the database, but we have developed a custom frontend to make browsing and navigating the archive more accessible.

We have taken a mixed approach to addressing the advanced search toolkit. We retain the ‘default’ interface of this toolkit as per its development by Wikimedia. It is the standard interface for querying Wikidata, the world's largest public linked data database. This means there is plenty of well-developed training materials about it. It also means that anyone who can use Wikidata's query interface, can use the DAAP's query interface and vice versa. At the same time, we make some modifications to the advanced search interface when we visualize the results of pre-programmed queries within the custom frontend interface.

AC: The question made me think of another aspect that's interesting to mention, related to the way you choose to represent the work online. Artists’ publishing is fantastically complex, with practices that range from the paperback to performance, long at the fore of pushing the potential for critical engagement, via feminist, post-colonial, queer, anti-ableist, and anti-capitalist critiques. Often these deploy strategies meant to evade the market, or prevent an easy reading that falls in step with oppressive structures inherent within language, for instance. As such, we have attempted to develop a database with sufficient complexity, whilst remaining searchable, that affords multiple histories to develop, confronting issues of authorship and representation, whilst addressing the challenges of cataloguing often deliberately difficult to categorise materials. And this is no short order.

With this degree of complexity comes an educational need to make available the reasons ‘why’ you might want to share something, and in what format would be most apt, or, perhaps, indeed, why you would not. In simple terms, if you wanted to circulate something widely, it may be advantageous to share it via the vast expanse of the Wikimedia commons. It may also be wise to hold back the distribution of the pdf of the book that you've just published in print. At least for a while. So, a big part of the work has been producing educational materials that can help inform users in making these decisions for themselves.

ALJ: Some features of the database require active participation by the user, like creating advance searches, and you are working with different communities to expand engagement, including adding data and actively developing it. How do you see the role of the active user, and how will you support it (e.g. training tools)?

LR: The role of the active user is crucial to the development and long-term maintenance and sustainability of this project. Many aspects of this system are complex, because they don't blackbox the system operations, but try to keep them open to users. With this software and this project, users are given the chance to participate more actively in the way their data is stored, structured, managed and in the end searched and visualized. We have been running workshops with the aim of showing what forms this active participation can take, and we are developing various tutorials and training materials to be published on the DAAP website, too.

We are also not alone in this endeavour. Being part of the Wiki community, this project can rely on an international community of other users who already actively use Wiki software and participate in various community events regarding training, feature development, growing community capacity, etc. Wikimedia UK have been supportive precisely in this direction. In addition, a newly inaugurated Working Group within IFLAFootnote 8 is dedicated to developing the Wikidata and Wikibase ecosystem, from feature development to training and documentation, within libraries. We see these parallel efforts as significant to the development of a healthy and sustainable ecosystem wherein users play an active role.

The DAAP is accessible online at: https://daap.network/.