Introduction

Individual behavior change is a critical component of climate change mitigation (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Gustafson and Van der Linden2020; IPCC, 2022; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Clayton, Stern, Dietz, Capstick and Whitmarsh2021a). However, in both scientific and public discourse, climate change mitigation is often portrayed as requiring an either/or choice between investing in individual behavior change versus systemic change. Systemic change (broadly conceptualized as changes in the system of rules, norms and institutions; Chater and Loewenstein, Reference Chater and Loewenstein2022) is then typically considered the more powerful, direct or urgent route toward climate change mitigation. The concern is that individual behavior change is hard to achieve, not impactful enough and sometimes even comes at the cost of the needed systemic change (Shove, Reference Shove2010; Mann, Reference Mann2019; Meyer, Reference Meyer2021; Chater and Loewenstein, Reference Chater and Loewenstein2022).

Here, we argue that pessimism about the potential impact of behavior change originates from an overly narrow view of pro-environmental behavior as the personal choices that individuals make to reduce their carbon footprint (e.g., saving household energy, avoiding air travel or reducing meat consumption; Klöckner, Reference Klöckner2013; Brownstein et al., Reference Brownstein, Kelly and Madva2021). With others (Amel et al., Reference Amel, Manning, Scott and Koger2017; Brownstein et al., Reference Brownstein, Kelly and Madva2021; Nielsen, Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Clayton, Stern, Dietz, Capstick and Whitmarsh2021a; Schill et al., Reference Schill, Anderies, Lindahl, Folke, Polasky, Cárdenas, Crépin, Janssen, Norberg and Schlüter2019), we posit that behavior change can be more appropriately understood as extending beyond individual contributions to decarbonization, and also comprises the role of individuals as members of communities and as citizens who have the power to influence the broader social and cultural structures they are part of. For example, individuals can influence the behaviors of groups of people, and collectively, they have the power to shape economic and political reform (Marteau et al., Reference Marteau, Chater and Garnett2021; Hampton and Whitmarsh, Reference Hampton and Whitmarsh2023). To be sure, the behaviors of individuals alone will likely not suffice to mitigate climate change sufficiently. However, individuals’ contributions may be significant when they galvanize system changes, such as those reflected in national laws, industrial policies or international treaties. We propose that a greater emphasis on behavior change as an indispensable factor of system change may not only encourage individuals’ pro-environmental commitments and actions but also spur system changes (e.g., public policies, industrial incentives) that, in turn, accommodate individuals to change their lifestyles (Cherry and Kallbekken, Reference Cherry and Kallbekken2023; Steg, Reference Steg2023).

While it is uncontested that both individual behavior change and broader systemic change can contribute to sustainability transitions (Grubler et al., Reference Grubler, Wilson, Bento, Boza-Kiss, Krey, McCollum and Valin2018; Van Vuuren et al., Reference Van Vuuren, Stehfest, Gernaat, Van den Berg, Bijl, De Boer and Van Sluisveld2018; Akenji et al., Reference Akenji, Lettenmeier, Koide, Toivio and Amellina2019), our understanding of their potential for mutual or synergistic contribution is only beginning to develop (Brownstein et al., Reference Brownstein, Kelly and Madva2021; Whitmarsh et al., Reference Whitmarsh, Poortinga and Capstick2021; Steg, Reference Steg2023). We challenge the ‘disputable duality’ (Bandura, Reference Bandura2000, p. 77) that pits individual behavior against institutional structures as if they are siloed entities or even detract from each other (Chater and Loewenstein, Reference Chater and Loewenstein2022). Instead, we build on emerging literature and aim to demonstrate how individual and systemic changes toward climate mitigation are fundamentally co-dependent and have the potential to reinforce each other – both in a bottom-up (from individual to system) and a top-down (from system to individual) fashion (Brownstein et al., Reference Brownstein, Kelly and Madva2021; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021b; Newell et al., Reference Newell, Daley, Mikheeva and Peša2023; Steg, Reference Steg2023). Specifically, we draw on the literature and distinguish four key pathways that explain how individual behavior change and system change are intertwined and may support each other. We do not argue that these pathways are orthogonal or mutually exclusive. Rather, while we acknowledge conceptual overlap, we discuss the pathways separately for the sake of clarity.

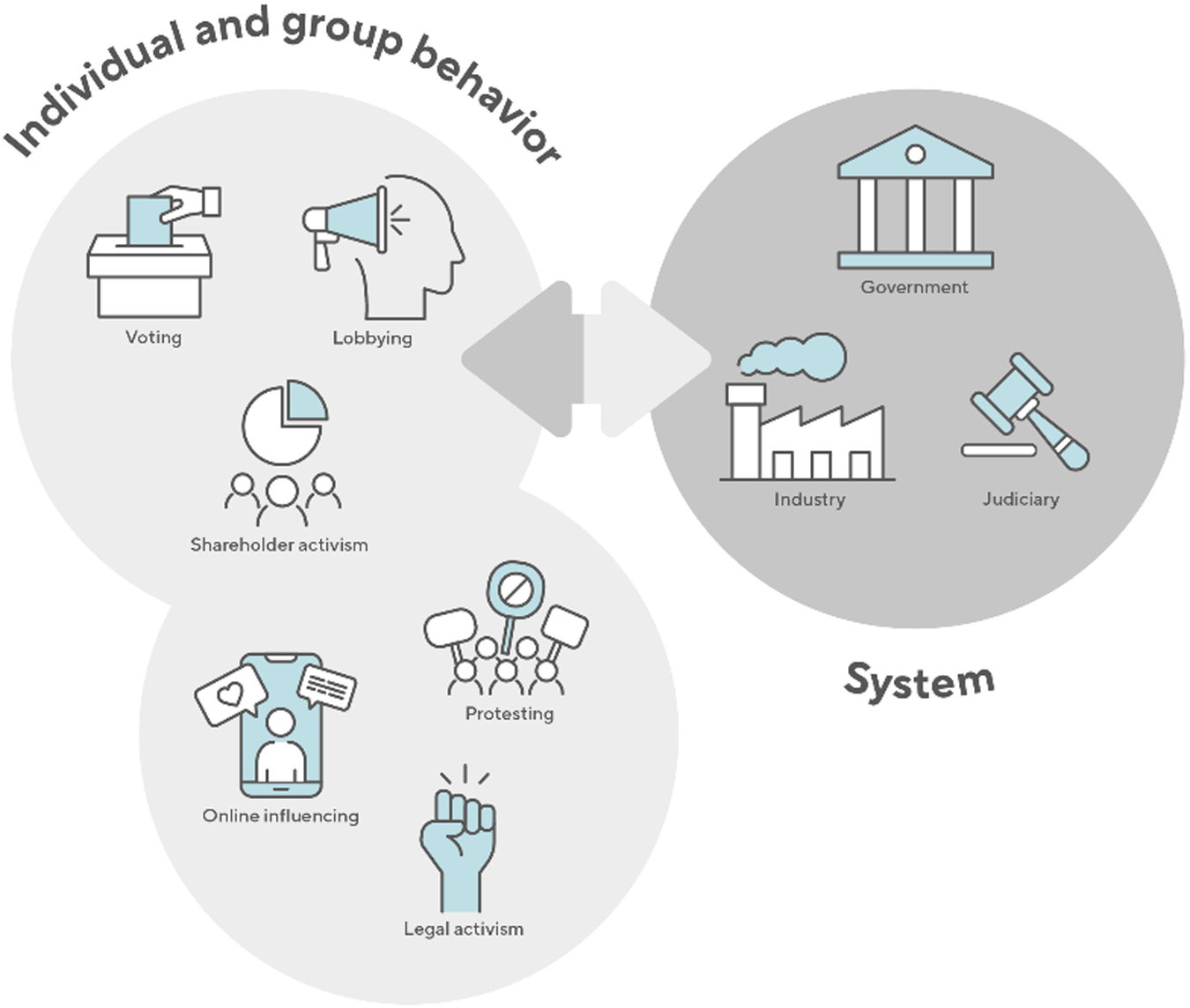

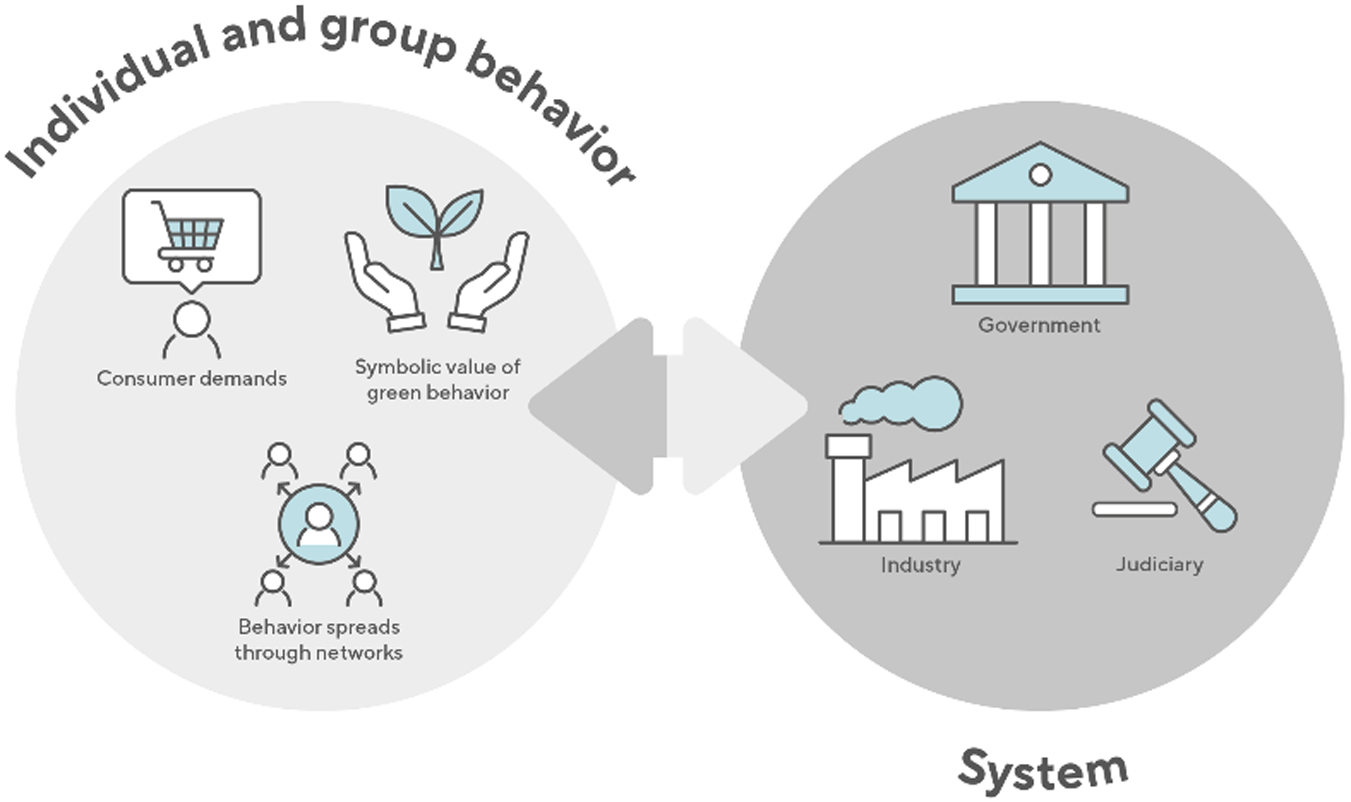

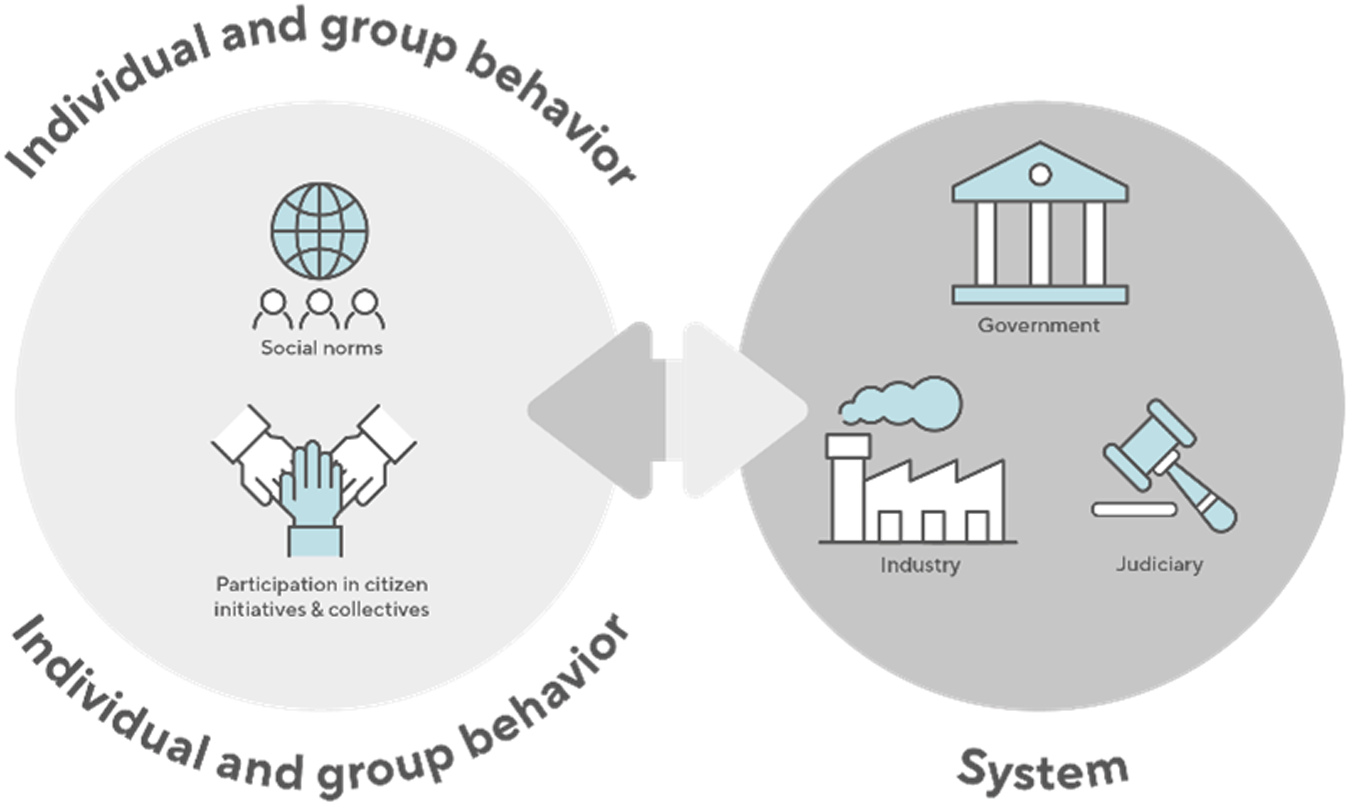

The first pathway emphasizes how consumer activism (e.g., voting, lobbying, participating in social movements) can foster policy actions for system change, as one illustration of how individuals’ behavior may directly impact the system. A second pathway emphasizes possibilities for system change resulting from shifting consumer values and demands, thus illustrating how individuals’ behavior may indirectly impact the system. The third pathway emphasizes that engaging people as a group, rather than as isolated individuals, may increase their commitment to climate change mitigation. This perspective focuses on the idea that participating in groups enhances individuals’ experience that they are part of (rather than separate from) the system. Finally, the fourth pathway emphasizes that the system can facilitate opportunities for individual contributions by creating policy arrangements that support people in their efforts to adopt sustainable lifestyles.

Importantly, the pathways of influence that we distinguish are not necessarily one-directional (i.e., top-down or bottom-up). If we accept that individual and systemic changes are co-dependent and can influence each other, as we argue, this opens up the possibility that climate change mitigation initiatives have the potential to set in motion a chain of events that contribute to sustainability transitions through a reciprocal process of mutual (i.e., top-down and bottom-up) influence. Such reciprocal processes are potentially powerful, to the extent that they may cause sustainable change to spiral and spread through society, potentially allowing large-scale sustainability transitions to unfold. These reciprocal processes are not just hypothetical – although still rare, they are happening right now, triggered by both bottom-up and top-down initiatives, as we will detail in our review.

Pathway 1: Impact of climate activism on system change

Climate activism is one way in which citizens can influence communities, governments, or industries to take responsibility and foster sustainable change. While climate activism can take various forms, its intended outcomes are typically to promote climate awareness, behavior change and policy support among the public, or to pressure political and industry leaders to bring about sustainable change. A distinction can be made between forms of climate activism that have direct versus indirect effects on greenhouse gas emissions (Fisher and Nasrin, Reference Fisher and Nasrin2021). Activism with direct effects promotes sustainable consumer behavior in groups of individuals (and aligns with notions central to Pathways 2 and 3). For example, this type of activism advances the establishment of green energy communities (e.g., Boulanger et al., Reference Boulanger, Massari, Longo, Turillazzi and Nucci2021), initiates car-sharing plans (e.g., Böcker and Meelen, Reference Böcker and Meelen2017) or develops strategies to encourage groups of individuals to reduce their meat consumption (e.g., Phua et al., Reference Phua, Jin and Kim2020) or avoid fast fashion (e.g., Johnstone and Lindh, Reference Johnstone and Lindh2022).

Other forms of activism do not aim to directly impact greenhouse gas emissions, but they do so indirectly by galvanizing change at the level of governments or industries. One route for such activism is via litigation. Across the world, citizens and climate advocacy groups have started legal procedures to demand from governments and industries that they adhere to climate responsibilities (Peel and Osofsky, Reference Peel and Osofsky2020). For example, in the Netherlands, the NGO Urgenda has won a landmark court case that forced the Dutch government to cut its greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in a drastic capacity reduction of the country’s coal-fired power stations (Wewerinke‐Singh and McCoach, Reference Wewerinke‐Singh and McCoach2021). Another route for such activism is by targeting industries, such as via shareholder activism (i.e., shareholders pushing companies to adopt sustainable changes) or by pressuring investors to abandon their holdings of stocks in polluting businesses (Glomsrød and Wei, Reference Glomsrød and Wei2018). Yet another route is to influence the political process, such as by lobbying governmental officials over climate policy (Meng and Rode, Reference Meng and Rode2019) or supporting election campaigns of green parties.

Arguably, the most visible form of activism with indirect effects on greenhouse emissions are climate strikes and related forms of public protest. Since 2018, the Extinction Rebellion (XR) and Fridays For Future (FFF) movements, in particular, have managed to grasp the attention of the general public and political leaders (De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, De Vydt, Uba and Wahlström2021). XR’s acts of nonviolent civil disobedience and disruptive protest (e.g., blocking roads, gluing oneself to entrances of public buildings) have been covered widely in the media, and the same is true for FFF’s climate strikes, which mobilized a historically large number of young people. Although their tactics and ideological emphases differ somewhat, both movements have held governments responsible for sustainable action and encouraged political leaders to rally behind climate science (De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, De Vydt, Uba and Wahlström2021). Some commentators have expressed concern that forms of activism that frustrate the interests of other individuals (e.g., blocking roads) create unnecessary division and undermine the large-scale solidarity that is needed to bring about change (e.g., Spicer, Reference Spicer2019). That said, emerging evidence suggests that XR and FFF have been effective at reaching at least some of their goals. For example, their actions have increased climate awareness and pro-environmental motivation and behavior among the general public (Fritz et al., Reference Fritz, Hansmann, Dalimier and Binder2023; Kountouris and Williams, Reference Kountouris and Williams2023), caused climate activism to spread around the world (Gardner et al., Reference Gardner, Carvalho and Valenstain2022), boosted voting for green political parties (Fabel et al., Reference Fabel, Flückiger, Ludwig, Rainer, Waldinger and Wichert2023) and benefited the value of green firms in stock markets (Schuster et al., Reference Schuster, Bornhöft, Lueg and Bouzzine2023).

The power of climate protest is that it can set in motion a reciprocal process of mutual (i.e., top-down and bottom-up) influence. FFF, for example, started bottom-up: a few committed individuals stepped outside the norm and, with the help of efficient communication networks (Eide and Kunelius, Reference Eide and Kunelius2021), sparked a highly visible movement supported by masses of young people. As such, FFF not only heightened public attention to the climate crisis but also raised political urgency and facilitated systemic change. Although it is hard to prove the causal effects of social movements, various industries targeting young people have begun to adopt sustainability initiatives over the past few years. Fast fashion leaders such as H&M, for example, have made efforts to improve the sustainability of their supply chain management to align with their sustainable branding (Wren, Reference Wren2022). Similarly, in response to growing demand among young consumers, fast-food chains increasingly offer plant-based menus or use climate impact menu labels (Ye and Mattila, Reference Ye and Mattila2021; Wolfson et al., Reference Wolfson, Musicus, Leung, Gearhardt and Falbe2022). Importantly, fast-fashion and fast-food chains do not just follow changing norms – rather, they have the power to amplify or accelerate changing norms as well, as illustrated by a study showing that doubling the proportion of vegetarian meals on offer in cafeterias increased vegetarian sales by more than 40% (Garnett et al., Reference Garnett, Balmford, Sandbrook and Marteau2019; cf., Raghoebar et al., Reference Raghoebar, Van Kleef and De Vet2020). As these examples illustrate, climate activism can set off chains of events that let sustainable change spiral through society (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Climate activism impacts system changes.

Pathway 2: Impact of consumption behavior on system change

Another way for individuals to influence system change lies in their consumption behavior, such as the energy they use, the food they eat or the ways in which they commute. Such ‘household consumption’ is estimated to be responsible for about two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions (mainly due to home energy use, food and mobility; Hertwich and Peters, Reference Hertwich and Peters2009). Thus, consumption behavior change offers important potential for climate change mitigation, with high-impact behaviors including shifting to plant-based diets, living car-free and reducing airplane travel (Wynes and Nicholas, Reference Wynes and Nicholas2017; Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Barrett, Wiedenhofer, Macura, Callaghan and Creutzig2020).

Still, in recent years, some experts have become increasingly skeptical of the potential for consumer behavior to contribute to climate change mitigation. One main argument driving such skepticism is that consumer behavior is notoriously hard to change. Indeed, people are drawn to routine behaviors that provide comfort (e.g., taking long showers, eating meat; MacDiarmid et al., Reference MacDiarmid, Douglas and Campbell2016; Gössling et al., Reference Gössling, Hanna, Higham, Cohen and Hopkins2019), are reluctant to forego personal benefits for the sake of the common good (Van Lange and Huckelba, Reference Van Lange and Huckelba2021), lack discipline (Gifford, Reference Gifford2011), are insufficiently aware of the urgency of sustainable behavior change (Weber, Reference Weber2006; Weber and Stern, Reference Weber and Stern2011) or are susceptible to misleading marketing (e.g., greenwashing; Fella and Bausa, Reference Fella and Bausa2024). Another argument is more strategic and emphasizes that advocacy for individual contributions to climate mitigation may shift attention away from the needed climate policy support and systemic change (Mann, Reference Mann2019; Palm et al., Reference Palm, Bolsen and Kingsland2020; Chater and Loewenstein, Reference Chater and Loewenstein2022).

While the value of consumer behavior to sustainability transitions is occasionally dismissed as ‘only symbolic’, we propose that this symbolic nature of consumer behavior is important to its potential for impact. First, consumer behavior can be meaningful to individuals. Even behaviors that have negligible environmental impact in and of themselves (e.g., using straws made of paper rather than plastic) can be meaningful to the extent that they activate or strengthen individuals’ pro-environmental identities. Identity-concerns can serve as potentially long-standing and powerful sources of motivation for individuals to engage in pro-environmental behavior (Brick et al., Reference Brick, Sherman and Kim2017; Fritsche et al., Reference Fritsche, Barth, Jugert, Masson and Reese2018). Moreover, relatively simple acts of pro-environmental behavior can strengthen individuals’ sense of efficacy or hope that one is able to make a positive difference, which may provide them with the needed motivation to adopt an enduring sustainable lifestyle (Lauren et al., Reference Lauren, Fielding, Smith and Louis2016).

Second, to the extent that pro-environmental consumption takes place in social contexts, it can serve a communicative function and has the potential to spread. Consider the example of an individual teenager deciding to eat plant-based alternatives to animal products in their school canteen. When the context is right (e.g., when their behavior is visible, when they have status within their peer group), such norm-setting can influence peers to adopt similar eating habits. As such, initial sustainable behaviors enacted by individuals have the potential to spread across social groups (Farrow et al., Reference Farrow, Grolleau and Ibanez2017; Sparkman et al., Reference Sparkman, Howe and Walton2021).

Third, and most importantly for the present purposes, consumer behaviors can have potentially far-reaching consequences by setting off systemic change. Laws of commerce imply that if consumption-related attitudes and behaviors shift within the population (i.e., among individual consumers), then industry will follow suit. Sustainable consumption trends are no exception. For example, consumers’ concern about the environmental impacts of mobility – supported by substantial government subsidies (Sierzchula et al., Reference Sierzchula, Bakker, Maat and Van Wee2014) – caused electric vehicle sales to grow (Rietmann et al., Reference Rietmann, Hügler and Lieven2020). Importantly, shifts in consumption patterns can quickly become widespread. Indeed, humans are sensitive to social influence and shifting social norms, which can compel large groups of individuals to change their consumption habits at relatively short notice (Alae-Carew et al., Reference Alae-Carew, Green, Stewart, Cook, Dangour and Scheelbeek2022; Constantino et al., Reference Constantino, Sparkman, Kraft-Todd, Bicchieri, Centola, Shell-Duncan and Weber2022).

We acknowledge that not all individuals are equally amenable to changing their consumption. One segment of the population for whom consumption behavior change is relatively viable and consequential are young people – and especially adolescents. Adolescence is a sensitive time for learning and growth, and a time when initial commitments to certain behaviors (e.g., eating plant-based foods) can serve as gateways to more enduring lifestyles (Dahl et al., Reference Dahl, Allen, Wilbrecht and Suleiman2018; Thomaes et al., Reference Thomaes, Grapsas, Van de Wetering, Spitzer and Poorthuis2023). Moreover, adolescents tend to be early adopters: they easily notice and internalize shifting social norms, especially norms that they observe in their peers. The implication for policy is that well-designed, developmentally-informed strategies that promote change in adolescents’ consumption behaviors can have sustained impacts (Thomaes et al., Reference Thomaes, Grapsas, Van de Wetering, Spitzer and Poorthuis2023; Figure 2). Of course, people (including young people) do not always voluntarily engage in or endorse sustainable behaviors. In those cases, some form of regulation may be needed. Simple rules mandating behavior can be beneficial to the extent that they set clear behavioral standards or expectations. However, telling people how to behave may undermine their trust in institutions and impede reciprocal behavior that could otherwise occur (Ostrom and Walker, Reference Ostrom and Walker2003; Rietz et al., Reference Rietz, Schniter, Sheremeta and Shield2018).

Figure 2. Changes in consumer behavior impacts system changes.

Pathway 3: Involving people as a community

Behavioral science research has provided lessons that policymakers can use to help people commit to climate change mitigation, such as framing climate change as a personal risk or appealing to environmental goals that people intrinsically value (Van der Linden et al., Reference Van der Linden, Maibach and Leiserowitz2015; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Gustafson and Van der Linden2020). These strategies mostly speak to climate mitigation as an individual effort. Our third pathway, however, proposes the potential of strategies that speak to climate mitigation as an effort of groups or ‘communities’ (Ballew et al., Reference Ballew, Goldbert, Rosenthal, Gustafson and Leiserowitz2019). People who consider themselves individual actors are at risk of experiencing helplessness or apathy, leading to inaction. Even if they consider their own pro-environmental contributions as potentially important, the anticipated inaction of others can compromise people’s motivation to contribute to the collective good of climate change mitigation. While massively scaling up individual actions may lead to significant reductions in global emissions (e.g., Creutzig et al., Reference Creutzig, Fernandez, Haberl, Khosla, Mulugetta and Seto2016; Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Satre-Meloy, Velasco and Green2018), efforts to commit groups of people by promoting ‘we-thinking’ are still relatively scarce.

Yet, behavioral science distinguishes at least two opportunities for doing so. First, research on social norms has revealed that communicating what others do, or think should be done, influences people’s motivation for behavior change (Cialdini, Reference Cialdini2003; Abrahamse and Steg, Reference Abrahamse and Steg2013; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Gustafson and Van der Linden2020). People feel empowered and are more inclined to adopt pro-environmental behaviors when they know that members of their own community – their friends, families and neighbors – endorse and adopt these behaviors as well (Estrada et al., Reference Estrada, Schultz, Silva-Send and Boudrias2017; Constantino et al., Reference Constantino, Sparkman, Kraft-Todd, Bicchieri, Centola, Shell-Duncan and Weber2022). Similarly, research on dynamic norms indicates that articulating a trending social norm can encourage pro-environmental behavior change (Sparkman et al., Reference Sparkman, Howe and Walton2021), suggesting that learning about others who act against the prevailing norm may serve as an impetus for changing one’s own behavior.

And yet, the potential of group power is not optimally harnessed if we rely on norm communication only. Social norms research typically treats norms as individual perceptions (e.g., individual perceptions of the expectations and behaviors of other people). However, norms also define what other people consider ‘normal’ or appropriate to do, and sets expectations in social interactions. There is a lack of research on the impact of pro-environmental norms that are actively conveyed in social interactions, such as when people discuss their views on what they consider to be normative or desirable (Prentice and Levy Paluck, Reference Prentice and Levy Paluck2020; Whitmarsh et al., Reference Whitmarsh, Poortinga and Capstick2021). This is unfortunate, given that people often underestimate how much others share their pro-environmental views if norms are not discussed openly (a phenomenon known as pluralistic ignorance; Geiger and Swim, Reference Geiger and Swim2016; Sparkman et al., Reference Sparkman, Geiger and Weber2022).

Second, supporting individuals to participate in joint efforts and collectives is an approach that is increasingly acknowledged as a promising way forward (De Ridder et al., Reference De Ridder, Aarts, Ettema, Giesen, Leseman, Tummers and De Wit2023; Amel et al., Reference Amel, Manning, Scott and Koger2017; Fritsche et al., Reference Fritsche, Barth, Jugert, Masson and Reese2018). When people’s feelings of connectedness to others increase, this may lead them to view climate change mitigation as a collaborative challenge and to experience collective agency (i.e., people’s shared beliefs in their joint power to produce desired results; Bandura, Reference Bandura2000; Fritsche and Masson, Reference Fritsche and Masson2021). In turn, collective agency may promote personal agency (Jugert et al., Reference Jugert, Greenaway, Barth, Büchner, Eisentraut and Fritsche2016) and increase the belief that individual actions have a substantial impact on the collective good of a sustainable society (Cojuharenco et al., Reference Cojuharenco, Cornelissen and Karelaia2016). Traditionally, collective action research has employed a social identity approach, resting on the notion that collective action is more likely when people identify with a group (their ‘in’ group) which they consider to be unjustly treated by another group with whom they disagree (the ‘out’ group) (Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Wullenkord, Reese and Van Zomeren2024). However, recent research suggests that people may not need an outgroup to be able to bond within their ingroup (De Ridder et al., Reference De Ridder, Aarts, Ettema, Giesen, Leseman, Tummers and De Wit2023; Fritsche and Masson, Reference Fritsche and Masson2021). Unlocking the power of the community may be achieved by conveying what people can do together for the sake of communal benefit – with the sense of community being twofold, referring both to the process (people acting together) and the outcome (benefit for all; De Ridder, Reference De Ridder2025). Importantly, realizing that other people acknowledge the problem of climate change and act accordingly creates a tipping point that may inspire others who were originally less inclined to change their behavior (Nyborg et al., Reference Nyborg, Anderies, Dannenberg, Lindahl, Schill and De Zeeuw2016). Taken together, an approach that speaks to people as members of a community opens up new avenues for engaging larger and more diverse groups of individuals who may not be pro-environmental frontrunners but have positive intentions nonetheless (Figure 3). Involving this group in collective action by providing supportive policy arrangements may critically facilitate behavioral sustainability transitions, as we will discuss as part of Pathway 4.

Figure 3. Facilitating groups to get together impacts system changes.

Pathway 4: Creating policy arrangements for collective climate action

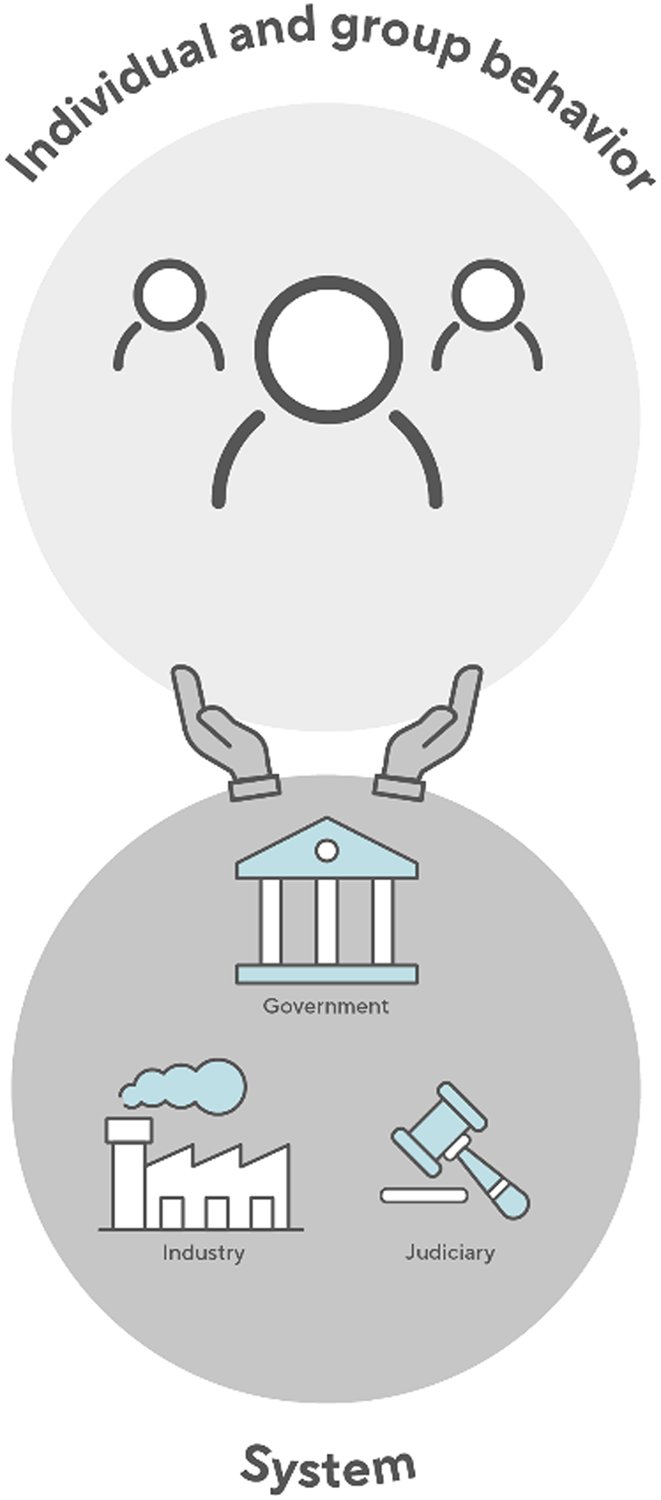

People getting together in collective action arrangements is an important pathway for bridging the gap between behavioral change and system change, as explained in our discussion of Pathway 3. However, only highly committed individuals may arrive at doing so without the help of supportive policy arrangements. Collectives are often initiated by minorities of people who are able and willing to organize themselves and challenge the status quo (Bolderdijk & Jans, Reference Bolderdijk and Jans2021). Policy arrangements can offer a larger, diverse group of people (including non-frontrunners) the opportunity to contribute by promoting self-organization across communities – indeed, widespread contributions to sustainability transitions are critical to unleashing system change. Here, we describe how such policy arrangements can promote citizen contributions to climate change mitigation (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Creating policy arrangements supports (groups of) individuals.

Interestingly, research suggests that citizens often support more ambitious climate policies than those currently implemented by their governments (e.g., Tyson and Kennedy, Reference Tyson and Kennedy2020). Whereas most policymakers aim at finding the right mix of different types of interventions, de facto, they often choose to either mandate certain behavior or ask individuals to voluntarily adopt the behavior (Ockwell et al., Reference Ockwell, Whitmarsh and O’Neill2009). In doing so, they miss out on opportunities to involve large groups of people who are willing to contribute to system change but may need some guidance in adjusting their behavior. Nudging green choices, for example, may be particularly effective (e.g., Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Bernauer, Sunstein and Reisch2020; Carlsson et al., Reference Carlsson, Gravert, Johansson-Stenman and Kurz2021; He et al., Reference He, Pan, Park, Sawada and Tan2023). To give one example, in the United States, the Opower program was effective in reducing household energy use by sending reports to households informing them about how their energy use relates to their neighbors’ use (Alcott and Rogers, Reference Alcott and Rogers2014). Importantly, green nudges are generally appreciated by citizens (Steffel et al., Reference Steffel, Williams and Pogacar2016; Wachner et al., Reference Wachner, Adriaanse and De Ridder2020), particularly when they are dissatisfied with their own behavior (Kukowski et al., Reference Kukowski, Bernecker, Nielsen, Hofmann and Brandstatter2023; cf. De Ridder et al., Reference De Ridder, Kroese and Van Gestel2022). Thus, people may consider climate policies a helpful tool to realize desired behavioral changes in their own lives.

We note that such policies do not necessarily need to promote individual responsibility. For one, policymakers may explicitly communicate their own pro-environmental actions and invite others to join (Attari et al., Reference Attari, Krantz and Weber2016), thus acting as ‘norm entrepreneurs’ (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2019) to facilitate public acceptance of climate change regulation. Policymakers may also encourage citizen collectives for promoting green behavior. Citizen collectives come in wide varieties. Some of these collectives are true grassroots, bottom-up initiatives; others are neighborhood communities that are promoted and supported by local governments or other institutions; and yet others are initiated by state or national governmental bodies responsible for sustainability transitions (Jans, Reference Jans2021). Despite the growing popularity of citizen collectives, it is not well understood why some of them are more successful than others. Whereas some collectives thrive, others have yielded more disappointing results – both in terms of group coherence and actual sustainable achievements (Bamberg et al., Reference Bamberg, Rees and Seebauer2015). The European Newcomers project on energy communities, for example, failed in its efforts to bring together people to work on their common interest in energy reduction (Blasch et al., Reference Blasch, Van der Grijp, Petrovic, Palm, Bocken and Mlinaric2021).

Capitalizing on the promise of citizen collectives in governing the energy transition requires an improved understanding of how and when people collaborate successfully on shared goals. Previous research on collective agency has emphasized how a sense of group belonging can create a willingness to act together on behalf of the common good (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997). Research on ‘commons’ has demonstrated that people tend to choose collective benefit (over individual benefit) when they meet in self-governing collectives and cooperatives (Vriens et al., Reference Vriens, Buskens and De Moor2021). In view of the growing popularity of the Ostromian perspective in political circles (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1998), it is important to back up this approach with quantifiable elements that lend themselves for application in group settings to accelerate the contribution of people to the sustainability transition.

Specifically, it is essential to adopt a collaborative governance approach to ensure that stakeholders from different backgrounds (e.g., the general public, public and private agencies) can experience at least some level of responsibility for the design and implementation of climate mitigation measures. In spite of reports of incidental failures in such cocreation processes, a collaborative governance approach is considered critical for citizen engagement with pressing societal challenges (e.g., Ansell and Gash, Reference Ansell and Gash2008; Fung, Reference Fung2015) including climate change mitigation (Amel et al., Reference Amel, Manning, Scott and Koger2017), as well as other policy domains such as pandemic mitigation (Marston et al., Reference Marston, Renedo and Miles2020; Mouter et al., Reference Mouter, Hernandez and Itten2021) or improving food environments (Koski et al., Reference Koski, Siddiki, Sadiq and Carboni2018; Poore and Nemecek, Reference Poore and Nemecek2018). In the case of sustainability specifically, the Earth System Governance framework (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Betsill, Gupta, Kanie, Lebel, Liverman, Schroeder, Siebenhüner and Zondervan2010), for example, highlights the importance of multilayered or multilevel governance that is marked by the participation of public and private non-state actors at all levels of decision-making, ranging from networks of experts and environmentalists to social enterprises and local communities. It has also been acknowledged that an institutionalized involvement of civil society representatives in decision-making makes governance more legitimate and accountable (Biermann and Gupta, Reference Biermann and Gupta2011). Notwithstanding these promising features, it should be recognized that the implementation of collaborative governance arrangements can also be challenging. The codesign of policies together with community stakeholders requires openness in discussion and effective procedures for consensus decision-making to achieve a shared understanding of problems and outcomes – requirements that may not naturally fit within the institutional framework in which public organizations operate (Peters, Reference Peters2015; Bianchi et al., Reference Bianchi, Nasi and Riverbark2021). Still, experiences with citizen collectives show that involving people as a group may not only accelerate system change but is, in fact, crucial to achieve system change in the first place.

Discussion

We have mapped four pathways that illustrate how individual behavior and system change are fundamentally co-dependent drivers of climate change mitigation. Our aim was to review research demonstrating how individual behavior change can be consequential for system change, and vice versa. As such, we build on work that moves away from scientific and public discourse that has viewed behavior and system change as separate or even mutually exclusive, and that has prioritized one of both drivers as more central to sustainability transitions. As behavioral scientists, we both acknowledge the power of behavior change of individuals, and recognize its limitations. Indeed, individual behaviors can have major climate impacts if large groups of people would change their lifestyles (e.g., consume less meat, reduce air travel or conserve more energy). At the same time, individuals cannot be held accountable for systemic failures, such as governments failing to invest in better public transport or the food industry being slow to develop plant-based alternatives for meat. Individuals who are committed to pro-environmental behavior change should be accommodated by supporting policies from responsible parties. Yet, people are not just passive followers waiting for governments and industries to take action – they themselves can stimulate policy changes as voters and consumers. Moreover, individuals matter to the extent that their acceptance of policies is required for their effectiveness. Thus, individual and systemic change can critically reinforce each other.

Of course, people are not always able and willing to take responsibility for their own lives and contribute to the common good. Merely providing people with clear information will typically not suffice to promote behavior change. Even if many people know perfectly well what they ‘ought’ (or would want) to do, they may fail to act accordingly, in part because they are not always capable of deliberating their choices (Keizer et al., Reference Keizer, Tiemeijer and Bovens2019; Whitmarsh et al., Reference Whitmarsh, Poortinga and Capstick2021). When designing policies, regulations and institutions, governments should appreciate that people are not interested and agentive all the time and consider supportive arrangements for creating opportunities for individuals to engage with public policies (De Ridder, Reference De Ridder2024).

As such, the recognition of the fundamental codependency between individual behavior change and system change calls for next steps. For one, we encourage research efforts to systematically scrutinize mutual influences between individual and system change, to learn more about their potential and boundary conditions for reaching climate impact. As one example: the European Human Rights Court ruled in 2024 that the Swiss government had violated the human rights of its citizens by failing to sufficiently invest in climate change mitigation (https://www.echr.coe.int/). It would be valuable to examine how the Court’s decision influences public opinion on climate change mitigation policies. Documenting such influences requires an interdisciplinary effort from scholars working in the behavioral and political sciences and law. Such collaborations can yield a well-rounded understanding of how system and individual changes coevolve. Even though interdisciplinary research on climate change mitigation is not new in itself, we call for greater attention to how system and individual behavior perspectives may boost one another.

Research on how behavior and system change are codependent in sustainability transitions should also inform policymakers working at the system level. Still, little is known about the extent to which policymakers are influenced by norms about climate policies within the population when implementing such policies. Whereas implementing these policies is part of complex political processes, it is critical to better understand at what point governments are able and willing to work together with citizens on climate mitigation, rather than initiating policies without active citizen contributions. Importantly, the codependency of individual behavior and system change may well vary across sociocultural contexts. For example, research has shown that individuals’ pro-environmental engagement is predicted by personal beliefs about environmental problems (e.g., environmental concerns) in individualistic, high-socioeconomic status (SES) or nonreligious contexts, but more strongly by social factors (e.g., perceived social norms) in collectivistic, lower-SES or religious contexts. This may be consequential for effective and culturally informed public policy, which may primarily target internal attributes (e.g., by raising awareness) in the former set of cultures, and social influence (e.g., by changing social norms) in the latter set of cultures (Eom et al., Reference Eom, Kim, Sherman and Ishii2016, Reference Eom, Papadakis, Sherman and Kim2019). In closing, behavioral scientists are well aware that behavior change is not a panacea to the complex problems posed by climate change and its mitigation. Nevertheless, a behavioral perspective is an indispensable element of climate change mitigation as it can accelerate system change as much as it depends on it.

Funding statement

This research has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 864137, awarded to Sander Thomaes).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.