LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• compare the pharmacological actions of the three partial agonists currently approved for treatment

• understand the uses of aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine in the treatment of different psychiatric disorders

• be aware of the different side-effect profiles of the individual agents.

This is the second of our articles on partial agonists of dopamine receptors. In it we use the receptor theory introduced in the first article (Cookson 2021) to discuss the specific pharmacology and clinical uses of aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine. Detailed laboratory investigations have led to the selection of these three partial agonists, which have been proven by clinical trials and licensed for use in psychiatry. Their development as novel antipsychotics has built on understanding of neurotransmission, using laboratory and computational techniques that visualise receptor structures and detect biochemical changes. Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine are phenylpiperazine derivatives, each with subtly different pharmacological actions, clinical benefits and side-effects. They are intended to have fewer extrapyramidal side-effects than older antipsychotics that are full neutral antagonists of dopamine.

Pharmacology

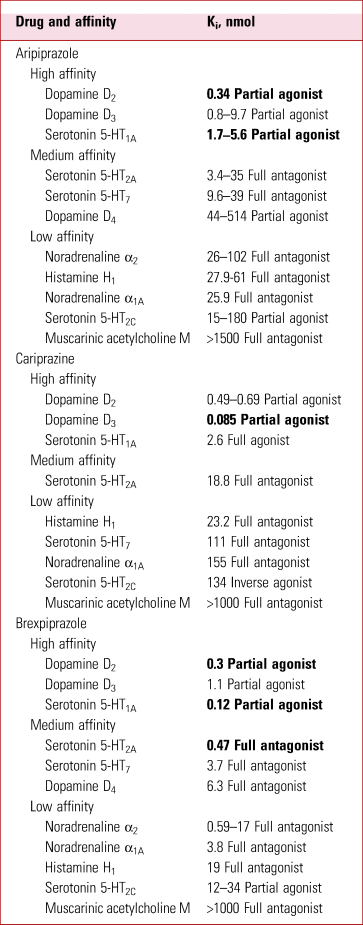

In cloned human receptors, all three have high affinities for D2-like dopamine receptors and for 5-HT1A serotonin receptors (being partial agonists at both), low affinities as full antagonists for histamine H1 and muscarinic acetylcholine M1 receptors, and intermediate affinities as full antagonists for many other receptors, including 5-HT2A and 5-HT7 (Tables 1 and 2). Clinical studies of receptor binding in positron emission tomography (PET) scans confirm some but not all these relative values.

TABLE 1 Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics characteristics of aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine

DM-3411, brexpiprazole S-oxide; DCAR, desmethyl cariprazine; DDCAR, didesmethyl cariprazine.

TABLE 2 Receptor affinity of aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazinea

a The most potent effects are highlighted in bold; smaller Ki indicates higher affinity.

Ki, binding affinity; Kd, dissociation constant.

Source: adapted from Roth & Driscol (Reference Roth and Driscol2017) and Citrome (Reference Citrome2018).

They have ‘intrinsic activity’ as agonists, a property explained in our previous article (Cookson Reference Cookson and Pimm2021).

They have long elimination half-lives (days) and are metabolised by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 to metabolites, which in the case of aripiprazole and cariprazine are active with a similar receptor binding profile to the parent compound.

Aripiprazole

Aripiprazole is a partial agonist with very high affinities for dopamine D2 and D3 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors (Roth Reference Roth and Driscol2017). Its active metabolite dehydroaripiprazole has similar activity and reaches similar blood levels.

The contribution of CYP3A4 to its metabolism is usually minor but in the presence of carbamazepine the enzyme is induced and doses may need to be doubled (to 20–30 mg/day). However, the CYP2D6 status is a major determinant and it is advised that doses are reduced in those on strong inhibitors (duloxetine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, risperidone, metoprolol or propranolol) and in poor metabolisers (Kiss Reference Kiss, Menus and Tóth2020). Beta blockers may be co-administered to treat akathisia.

Just 1 mg aripiprazole daily produces 50% occupancy of D2 receptors at steady state (which is reached after 2–3 weeks of regular doses); 10 mg daily produces 95% occupancy and near maximum efficacy in schizophrenia. Intrinsic activity has been estimated as 25%, so that its maximum effective antagonism of dopamine could reach 75% (Sparshatt Reference Sparshatt, Taylor and Patel2010). This would be expected to limit its ability to improve the most severe mania or agitation (Cookson Reference Cookson and Pimm2021).

The most common adverse events are akathisia, restlessness, tremor and insomnia (all of which can contribute to agitation) and nausea.

Brexpiprazole

In cloned receptors, brexpiprazole is a high-affinity partial agonist at 5-HT1A, D2 and D3 receptors (Roth Reference Roth and Driscol2017). However, its main receptor binding actions in clinical studies are at D2 and 5-HT2A receptors, with negligible occupancy at D3 or 5-HT1A; a dose of 4 mg/day reached 80% occupancy of D2 receptors after 10 days, and little D3 occupancy (Girgis Reference Girgis, Forbes and Abi-Dargham2020).

Brexpiprazole has less intrinsic activity than aripiprazole at D2 receptors and was therefore expected to cause less akathisia and insomnia than aripiprazole, trends that are seen in treating schizophrenia (Huhn Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou and Schneider-Thoma2019). It failed to show efficacy in mania, consistent with the view that mania commences in more ventral dopamine pathways, richer in D3 than D2 (Cookson Reference Cookson2013). There are no published controlled trials in bipolar depression.

Brexpiprazole is licensed in both the USA and UKbut there are no plans yet to launch in the UK. Additional information about its use in schizophrenia is provided by Ward & Citrome (Reference Ward and Citrome2019), suggesting a possible advantage over aripiprazole in terms of reduced akathisia and weight gain.

Cariprazine

Cariprazine is a partial agonist at D2-like dopamine receptors and a full agonist at 5-HT1A receptors. Its affinity is greatest for D3 receptors (where it is a partial agonist with about 60% intrinsic activity) and less for D2 (with about 40% intrinsic activity) (Roth Reference Roth and Driscol2017; Citrome Reference Citrome2018).

After 2 weeks of 3 mg/day, the mean D3 and D2 receptor occupancies were 92 and 79% (Girgis Reference Girgis, Slifstein and D'Souza2016).

Cariprazine has active metabolites with similar receptor binding activities, but very long half-lives (1–3 weeks). Its main metabolite didesmethyl cariprazine (DDCAR) reaches three times higher plasma levels at steady state and has higher selectivity for D3 receptors than cariprazine, and is a full agonist at 5-HT1A receptors (Tadori Reference Tadori, Miwa and Tottori2005; Kiss Reference Kiss, Némethy and Fazekas2019).

Cariprazine is primarily metabolised through CYP3A4. Co-administration with a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 (fluoxetine, ketoconazole) or grapefruit juice may necessitate a halving of the usual dose but clinical interactions have not been reported (Citrome Reference Citrome2018).

The licensed dose is 1.5–6 mg/day for acute schizophrenia and maintenance treatment, and in the USA it is also licensed for mania and for bipolar depression.

Clinical use of aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine

Licensed uses

The licensed indications of the three drugs vary and are shown in Table 3. Aripiprazole is also licensed for irritability associated with autism spectrum disorder. Only aripiprazole (intramuscular injection) is licensed for agitation in schizophrenia or mania. Aripiprazole is also available for long-acting injection (with steady state reached after 5 months and a notional half-life of 1 month).

TABLE 3 Licensed indications for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine in the UK and/or USA in 2020

Side-effects

In general, partial agonists of dopamine receptors cause fewer receptor blockade-related side-effects than full antagonists (few Parkinsonian or dystonic side-effects and fewer side-effects related to increased prolactin). However, the most common are akathisia, restlessness, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, diarrhoea, constipation, insomnia and sedation (Zhao Reference Zhao, Lin and Teng2016; Huhn Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou and Schneider-Thoma2019; Ward Reference Ward and Citrome2019).

A common adverse event in long-term treatment is worsening of symptoms in both schizophrenia and mania. In a long-term study using continuation on medication as a measure of effectiveness, aripiprazole was not as effective as most other antipsychotics for continuation or preventing readmission to hospital (Zhao Reference Zhao, Lin and Teng2016).

Over 1 year, the most common adverse events were akathisia, headache, insomnia, and increase in body weight.

Weight changes

Short-term (8 weeks) weight gain with these drugs is slight, comparable with haloperidol and much less than with olanzapine or clozapine (Pillinger Reference Pillinger, McCutcheon and Vano2020).

In maintenance treatment, gradual weight gain and metabolic effects occur. In early-episode psychosis, no advantage was seen for cohorts on aripiprazole compared with paliperidone in weight change over 1 year, although aripiprazole was associated with lower triglycerides and prolactin levels (Shymko Reference Shymko, Grace and Jolly2021). A 1-year randomised controlled trial (RCT) of aripiprazole, quetiapine and ziprasidone in drug-naive first-episode non-affective psychosis found overall increases in weight, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides, but no significant differences between drugs (Vázquez-Bourgon Reference Vázquez-Bourgon, Pérez-Iglesias and de la Foz2018).

Impulsivity and compulsive sexual urges

All three drugs can cause new or intense gambling urges, compulsive sexual urges, compulsive shopping, binge or compulsive eating, or other urges (Etminan Reference Etminan, Sodhi and Samii2017).

Tourette syndrome

The verbal and motor tics of Tourette syndrome are improved by aripiprazole (Sallee Reference Sallee, Kohegyi and Zhao2017).

Stimulant misuse

In people dependent on methamphetamine, use of the stimulant drug was increased on aripiprazole at a dose of 15 mg/day (Tiihonen Reference Tiihonen, Kuoppasalmi and Föhr2007). This cautions against its use in methamphetamine psychosis; a network meta-analysis found it inferior to olanzapine, quetiapine, haloperidol and paliperidone, with no difference in drop-out rates (Srisurapanont Reference Srisurapanont, Likhitsathian and Suttajit2020).

Schizophrenia

In a network meta-analysis of the efficacy of 32 antipsychotics in RCTs in acute schizophrenia, the rank order of efficacy of partial agonists on overall symptoms was aripiprazole > cariprazine > brexpiprazole, with little difference between them (Huhn Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou and Schneider-Thoma2019). All were less efficacious than risperidone; brexpiprazole was less efficacious than haloperidol.

Cariprazine required more anti-Parkinsonian medication than placebo. Akathisia was seen more often with aripiprazole and cariprazine than with placebo.

Prolactin was lowered by aripiprazole and unchanged with brexpiprazole or cariprazine.

The corrected QT interval (QTc) was unchanged. Sedation was rare and seen more often with aripiprazole. No anticholinergic side-effects were seen.

The network analysis showed no obvious advantage on negative symptoms, but aripiprazole and cariprazine were among the best for the improvement of depressive symptoms.

However, in an RCT involving stable patients with predominantly negative symptoms of schizophrenia, a change of medication to cariprazine (mean 4.2 mg/day) led to greater improvement in negative symptoms than a change to risperidone (3.8 mg/day) over 26 weeks (effect size 0.3) (Németh Reference Németh, Laszlovszky and Czobor2017), and this was not attributable to a change in depressive symptoms.

Autism spectrum disorder

A network meta-analysis concluded that risperidone and aripiprazole were the two best atypical antipsychotics, with comparable efficacy and safety, for young people with autism spectrum disorder, beneficial in improving irritability (Fallah Reference Fallah, Shaikh and Neupane2019).

Mania

Aripiprazole and cariprazine are superior to placebo in mania. Aripiprazole is significantly less efficacious than haloperidol or risperidone; the efficacy of cariprazine (up to 12 mg/day) is intermediate between aripiprazole and risperidone (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Barbui and Salanti2011; Yildiz Reference Yildiz, Nikodem and Vieta2015), but the trials permitted additional benzodiazepines for agitation.

There are guidelines for the use of aripiprazole in mania that advise combination with a benzodiazepine initially; it is rarely a first-line choice, perhaps because of lack of sedation and lower efficacy than full antagonists of D2-like receptors (Aitchison Reference Aitchison, Bienroth and Cookson2009; Goodwin Reference Goodwin, Abbar and Schlaepfer2011). By contrast, cariprazine has a greater effect than aripiprazole on ventral striatal D3 receptors, which may be important for treating mania (Cookson Reference Cookson2013).

Agitation in mania or schizophrenia

Aripiprazole has been used in rapid tranquillisation (Cookson Reference Cookson2018).

Intramuscular aripiprazole as monotherapy improves moderately severe agitation in people with mania (mean Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score 24 out of maximum 60) (Zimbroff 2007) and in people with schizophrenia (mean Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale-Excited Component (PANSS-EC) score 19 out of maximum 35) (Tran-Johnson Reference Tran-Johnson, Sack and Marcus2007).

Bipolar depression

Aripiprazole has been investigated for depression in bipolar I disorder and has no proven efficacy.

Two large RCTs of cariprazine in bipolar I depression showed efficacy. The number needed to treat (NNT) for response 50% improvement in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score with a dose of 1.5 mg/day was 4 (95% CI 4–16) and with 3 mg/day 8 (95% CI 5–58) (Durgam Reference Durgam, Earley and Lipschitz2016a). Earley (Reference Earley, Burgess and Rekeda2019) found an NNT of 9 with 3 mg/day but at 1.5 mg/day the result was not significant. At the higher dose, the drop-out rate was greater; the side-effects were mainly akathisia, insomnia, nausea and irritability.

This striking difference between aripiprazole and cariprazine may relate to the greater stimulant action of cariprazine on D3 receptors.

Maintenance in bipolar disorder

Aripiprazole has mood-stabilising properties, reducing manic relapses without evident benefit for depressive relapses (Miura Reference Miura, Noma and Furukawa2014).

Unipolar depression

Aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are efficacious as adjuncts to antidepressants in unipolar depression. From five pooled studies, aripiprazole had the largest effect size (ES) of any antipsychotic as an adjunct to antidepressants (including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and mirtazapine) (ES = 0.50, 95% CI 0.31–0.67); for brexpiprazole the effect size was small (ES = 0.18, 95% CI 0.10–0.26) (Carter Reference Carter, Strawbridge and Husain2020) and the NNT for response was 14 (Thase Reference Thase, Zhang and Weiss2019). Cariprazine was also efficacious as an adjunct in an RCT, with ES = 0.5 and NNT = 9 for response on 2–4.5 mg/day. The most common side-effects were akathisia (22%), insomnia (14%) and nausea (13%) (Durgam Reference Durgam, Earley and Guo2016b); it is not currently licensed for this indication. The adjunctive efficacy in unipolar depression may relate to actions stimulating 5-HT1A and blocking 5-HT2A (brexpiprazole) and 5-HT7 receptors (aripiprazole and brexpiprazole).

Conclusions

Partial agonists at dopamine D2-like (and 5-HT1A) receptors have been developed as novel antipsychotics primarily for schizophrenia, with low risks of Parkinsonism or hyperprolactinaemia, modest increases in body weight and moderate efficacy. They are also useful in some stages of bipolar disorder and as adjuncts for unipolar depression. Each has a distinct profile of efficacy rather than a unified class effect. Their side-effect profiles make them attractive potential alternatives to other antipsychotics in some people; these might include those with lesser degrees of excessive dopamine release, requiring lower antagonistic occupancy, for example in early phases of schizophrenia (Kane Reference Kane, Schooler and Marcy2020) and in very late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis (Rado Reference Rado and Janicak2012).

However, switching to, or adding, partial agonists to full antagonists has theoretical implications that call for careful judgements in prescribing to avoid triggering relapse by displacing antagonist occupancy.

The efficacy of cariprazine in bipolar disorder and for negative symptoms in schizophrenia highlights the importance of D3 dopamine receptors which are predominant in ventral areas of dopamine pathways involved in reward and motivation (Sokoloff Reference Sokoloff and Le Foll2017).

Author contributions

J.C. and J.P. contributed equally to this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

J.C. is a member of the BJPsych Advances editorial board and did not take part in the review or decision-making process for this article.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Regarding the pharmacology of aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine:

a all three act as full antagonists at the D2-like receptor and the 5-HT1A receptor

b all three have high affinities for the D2-like receptor and low affinities for the 5-HT1A receptor

c all three have low affinities for the D2-like receptor and the 5-HT1A receptor

d all three have high affinities for the D2-like receptor and the 5-HT1A receptor

e all three act as partial agonists at the H1 and acetylcholine M1 receptors.

2 Elimination and metabolism of all three partial agonists aripiprazole, brexpiprazole and cariprazine from the body:

a is rapid compared with other antipsychotics

b takes place over several days because they have long half-lives

c takes place over hours because they have short half-lives

d involves the production of active metabolites with similar receptor profiles to the parent compound

e may need to be increased in patients who are also taking fluoxetine or drinking grapefruit juice.

3 Regarding aripiprazole's occupancy of the D2 receptors:

a 1 mg daily will reach 50% occupancy after 14–21 days

b 10 mg daily will reach 10% occupancy after 14–21 days

c 4 mg daily will reach occupancy of 20% after 10 days

d 3 mg daily will reach 50% occupancy after 10 days

e 1 mg daily will reach 10% occupancy after 14–21 days.

4 Which of the following pairings of common adverse effects and partial agonist is correct?

a aripiprazole and worsening of verbal and motor tics in Tourette syndrome

b brexpiprazole and akathisia

c cariprazine and weight loss

d aripiprazole and decrease in the use of methamphetamine in dependent patients

e cariprazine and tardive dyskinesia.

5 Little evidence for the efficacy of treating psychiatric disorders using partial agonists has been shown with:

a aripiprazole in schizophrenia and rapid tranquillisation

b cariprazine in bipolar I depression and in mania

c aripiprazole in bipolar I depression and on the negative symptoms of schizophrenia

d brexpiprazole as an adjunctive treatment to antidepressants in unipolar depression

e aripiprazole in autism spectrum disorder and in mania.

MCQ answers

1 d 2 b 3 a 4 b 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.