The first known document reporting the association between epilepsy and psychosis dates back to the second millennium BC, with an Assyrian medical text (Assyrian Medical Texts, AMT 96,7 British Museum and Keilschrifttexte aus Assur Religiösen Inhalts KAR 26, Berlin). Reference Kinnier Wilson, Güterbock and Jacobsen1,Reference Reynolds and Kinnier Wilson2 Subsequently the Greeks (e.g. Hippocrates) described the association between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders as arising in the brain and influenced by the moon. Reference Temkin3 In 20th-century neuropsychiatry, many authors have shown interest in the psychoses of epilepsy, including Slater, Landolt and Trimble, who introduced new concepts such as interictal schizophrenia-like psychoses of epilepsy, Forcierte Normalisierung and Ersatzpsychose (forced normalisation and alternative psychoses), providing accurate descriptions of clinical presentations and describing long-term outcomes. Reference Temkin3–Reference Landoldt8

With the new definition of epilepsy, psychiatric disorders become an integral part of the condition itself, leading to a rejuvenated interest in psychiatric disorders. Reference Fisher, Acevedo, Arzimanoglou, Bogacz, Cross and Elger9 Furthermore, the new multi-axial classification of epilepsy syndromes recognises the importance of comorbidities, along with aetiologies and seizure types. Reference Scheffer, Berkovic, Capovilla, Connolly, French and Guilhoto10 However, data on the management of psychotic symptoms in epilepsy remain limited, and clinical management is mainly based on individual experience or uncontrolled studies.

This is a narrative review discussing the interplay between epilepsy and psychosis and identifying challenges in diagnosing and managing psychotic symptoms in adults with epilepsy. Articles published between June 2014 and December 2024 were identified through searches in PubMed using the search terms ‘psychosis’, ’seizure, epilepsy and convulsion’, ‘epile*’, ’seizure*’ and ‘convuls*’. No language restrictions were applied. This search generated 749 abstracts. Articles were selected based on originality and relevance to the present topic. Additional articles were identified from the authors’ files and chosen bibliographies.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of any psychiatric disorder in unselected samples of adults with epilepsy is reported to be as high as 43.3%. The most frequent examples include mood disorders (up to 40% for lifetime diagnoses and up to 23% for current) and anxiety disorders (30.8% for lifetime and up to 15.6% for current). Psychotic disorders are also over-represented in epilepsy, in the region of 4%. Reference Gurgu, Ciobanu, Danasel and Panea11,Reference Lu, Pyatka, Burant and Sajatovic12 Psychiatric disorders have previously been shown to have a high prevalence in individuals newly diagnosed with epilepsy, Reference Kanner, Saporta, Kim, Barry, Altalib and Omotola13 and a complex relationship with somatic’ disorders has been hypothesised. Reference Rainer, Granbichler, Kobulashvili, Kuchukhidze, Rauscher and Renz14

Temporal lobe epilepsy, in particular, has long been recognised as a risk factor for psychosis. However, there is a lack of consistency in findings across studies on the effect size of this risk, which reflects methodological differences in studies and changes in diagnostic classifications within the disciplines of neurology and psychiatry. Various studies have adopted different definitions and classifications for psychosis. Within these limitations, a meta-analysis of 58 studies reported psychotic disorders (from schizophrenia to schizophreniform disorders) in up to 6% of people with epilepsy, which represents an almost threefold increased risk as compared with the general population, rising to eightfold in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Reference Clancy, Clarke, Connor, Cannon and Cotter15 Two recent meta-analyses provided similar estimates confirming previous observations. Reference Thapa, Panah, Vaheb, Dahal, Maharjan and Shah16,Reference Kwon, Rafati, Ottman, Christensen, Kanner and Jetté17 Nevertheless, patients with epilepsy present with an increased (two- to threefold) risk of being hospitalised for schizophrenia as compared with the general population. Reference Adachi and Ito18 Taken together, all of the above data clearly support the premise that epilepsy, involving the temporal lobe type in particular, represents a risk factor for the development of psychosis.

However, although the relationship between epilepsy and psychoses has been shown not to be simply unidirectional, people with psychoses have also been shown to be at increased risk of developing epilepsy. A matched, longitudinal cohort study including 3773 people with epilepsy and 14,025 controls, matched by year of birth, sex, general practice and years of medical records prior to the index date, indicated an incidence rate ratio (IRR) of psychosis, depression and anxiety significantly increased for all years preceding epilepsy diagnosis (IRR, 1.5–15.7) and following (IRR, 2.2–10.9), suggesting a bidirectional relationship between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, including psychoses. Reference Hesdorffer, Ishihara, Mynepalli, Webb, Weil and Hauser19

A Swedish population-based case-control study involving 1885 subjects with new onset of unprovoked seizures and 15 080 random controls showed an age-adjusted odds ratio for unprovoked seizures of 2.3 following a hospital discharge for psychosis for >2 years. Reference Adelöw, Andersson, Ahlbom and Tomson20 A retrospective cohort study investigating the co-occurrence of epilepsy and psychosis showed a two- to threefold increased risk of epilepsy in people admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and a four- to fivefold increased risk of schizophrenia in those admitted with a diagnosis of epilepsy. Reference Wotton and Goldacre21 Taking these data together, it is now recognised that epilepsy is between four and six times more frequent among individuals with psychosis and thought disorders as compared with the general population. Reference Adachi and Ito18

However, further research in this area is needed. No gender or age difference was identified across studies, but there remains a lack of data about the role of demographic variables, particularly ethnicity and special populations. Furthermore, numbers of studies looking at multiple psychiatric comorbidities in epilepsy remain minimal. One recent meta-analysis showed that depression and anxiety comorbidity is more frequent in people with epilepsy than without (odds ratio 3.7, 95% CI 2.1–6.5, P < 0.001, I 2 = 0%, Cochran Q P-value for heterogeneity 0.84), as well as the association between depression and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (odds ratio 5.2, 95% CI 1.8–15.0, P = 0.002, I 2 = 0%, Cochran Q P-value for heterogeneity 0.79), but data on psychosis were not available. Reference Kwon, Rafati, Gandy, Scott, Newton and Jette22 However, current data do not suggest, for example, that depression in epilepsy is more likely to be associated with psychotic symptoms than in the general population. Reference Zinchuk, Kustov, Pashnin, Pochigaeva, Rider and Yakovlev23,Reference Mula, Brodie, de Toffol, Guekht, Hecimovic and Kanemoto24

Pathophysiology

The neurobiological links between epilepsy and psychoses have not been clarified. First, it is essential to point out that the relationship between epilepsy and psychosis as brain disorders is different from that between psychotic symptoms and seizures, and the epidemiological data supporting the bidirectional relationship looked specifically at the two brain conditions. This bidirectional relationship between these two disorders suggests shared or common neurobiological mechanisms, and data on temporal lobe epilepsy seem to indicate that psychoses may represent a marker of severity of temporal lobe pathology, given the number of abnormalities identified in the mesiotemporal structures. Reference Schmitz and Wolf25–Reference Van Elst, Baeumer, Lemieux, Woermann, Koepp and Krishnamoorthy28 However, a systematic review of the structural and functional neuroimaging studies on the psychosis of epilepsy shows that brain abnormalities in individuals with epilepsy and psychoses go beyond the mesiotemporal structures, involving networks that may be distant, but still connected, to the frontotemporal networks. Reference Allebone, Kanaan and Wilson29 In terms of epilepsy, an early onset of epilepsy and a long duration of active disease are also well-recognised epilepsy-related risk factors. Reference Adachi, Matsuura, Okubo, Oana, Takei and Kato30 Data on the relative contribution of additional neurological factors, such as dementia or stroke, for example, are lacking despite their potential role, given that they are also associated with an increased risk of epilepsy. Reference Martin, Faught, Richman, Funkhouser, Kim and Clements31–Reference Fischer and Agüera-Ortiz33

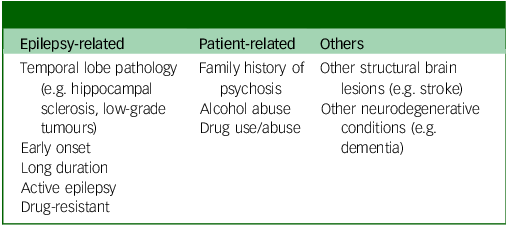

In the same way, there are no data about risk factors commonly identified for psychosis outside epilepsy, such as alcohol and drug use and family history, but it is reasonable to hypothesise that these can represent contributory factors. Finally, the emerging role of neuroinflammation in both epilepsy and psychosis has to be acknowledged. Neuroinflammation can act as a key contributor to the development and progression of these conditions, by creating an environment of excessive neuronal excitability through the activation of glial cells, which can lead to seizures in epilepsy and contribute to the distorted perceptions and thought patterns seen in psychosis; essentially, chronic inflammation in the brain can disrupt regular neural communication and function, leading to symptoms of these disorders. Reference Suleymanova34 There is no doubt that psychosis in epilepsy remains understudied, and studies are biased by small sample sizes and antipsychotic use Reference Sone35 (Table 1).

Table 1 Risk factors for the development of psychosis in epilepsy

At this stage, it is essential to point out that psychotic symptoms and seizures have historically shown an antagonistic relationship, meaning that the neurobiology of seizures seems to antagonise that of psychotic symptoms. One of the first observations dates back to the seminal work of Ladislas Meduna, Reference v. Meduna36–Reference de Meduna41 representing the theoretical basis for the subsequent development of shock therapies. Reference Scaramelli, Braga, Avellanal, Bogacz, Camejo and Rega43 In 1934, Meduna induced an epileptic seizure in a 33-year-old man with catatonic schizophrenia. Following 5 further seizures over 3 weeks, the psychosis was relieved. Meduna also observed greater concentrations of brain glia in individuals with epilepsy than in those with schizophrenia and, in his monograph Die Konvulsionstherapie der Schizophrenie, reported that more than half of 110 schizophrenic individuals recovered following seizures induced by pentylenetetrazol. Reference de Meduna41 By 1936, pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures were in use throughout the world, with electrical inductions later replacing pharmacologically induced seizures, opening the field for electroconvulsive therapy.

Clinical presentation

In people with epilepsy, psychotic symptoms may occur in three major clinical scenarios: seizure-related (peri-ictal), interictal and treatment-related (Table 2).

Table 2 Psychotic symptoms in epilepsy

Peri-ictal psychoses

Among peri-ictal psychoses, pre-ictal ones are the least common and least studied. These present with various unspecific symptoms during the hours (rarely up to 3 days) before a seizure, including derealisation and depersonalisation experiences, forced thinking, ideomotor aura, déjà vu, jamais vu, anxiety, euphoria and perceptual experiences such as hallucinations or illusions. Reference Agrawal and Mula44 These symptoms usually end with the seizure but are not associated with detectable electroencephalogram changes. Reference Gold, Sher and Maldonado45

Ictal psychoses are episodes of non-convulsive status epilepticus, mostly of temporal lobe origin, but they represent an infrequent occurrence. Reference Shorvon and Trinka46,Reference Subota, Khan, Josephson, Manji, Lukmanji and Roach47

Post-ictal psychoses

Among all post-ictal symptoms, psychotic ones occur in only 4% of cases while headaches and migraines are much more frequent. Reference Nadkarni, Arnedo and Devinsky48 However, when looking at peri-ictal psychotic symptoms, post-ictal ones are the most frequent, representing 60% of peri-ictal psychotic symptoms. Reference Gold, Sher and Maldonado45,Reference Laxer, Trinka, Hirsch, Cendes, Langfitt and Delanty49,Reference Oshima, Tadokoro and Kanemoto50 The classic clinical presentation is characterised by a period of normal mental state, known as the lucid interval, following a seizure or cluster of seizures and lasting between 24 and 48 h. Reference Devinsky, Abramson, Alper, FitzGerald, Perrine and Calderon51–Reference Tarrada, Hingray, Aron, Dupont, Maillard and de Toffol53 The psychotic episode is characterised by mixed moods with psychomotor excitation, ecstatic moods and mystic or religious delusions, Reference Kanemoto, Kawasaki and Kawai26 resembling more an affective psychosis than a pure psychotic disorder. Reference Logsdail and Toone54 However, post-ictal psychoses differ from depressive disorders with psychotic symptoms. While both post-ictal psychosis and psychotic symptoms in depression involve experiencing psychosis, the former occurs directly following a seizure, the psychotic symptoms do not necessarily follow the mood theme and, while post-ictal psychosis is usually temporary, resolving within days or weeks, psychotic depression may last longer depending on treatment.

Post-ictal psychoses represent psychiatric emergencies, given the high prevalence of aggressivity and mortality rates for suicide or other accidents historically reported in up to 28.5% of cases. Reference Umbricht, Degreef, Barr, Lieberman, Pollack and Schaul55 Recent data on the prognosis of post-ictal psychoses are still lacking. In terms of long-term prognosis, historical data suggest the development of chronically unremitting psychotic symptoms in 21–25% of individuals. Reference Slater, Beard and Glithero5,Reference Umbricht, Degreef, Barr, Lieberman, Pollack and Schaul55 More recent data indicate the possibility of bimodal psychosis characterised by relapses, against a background of chronic symptoms. Reference Adachi and Ito18

Interictal psychoses

Historical descriptions of chronic psychosis in epilepsy include the so-called interictal schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy, which various authors have identified as distinct from sporadic schizophrenia in terms of clinical presentation and long-term outcomes. Reference Trimble56,Reference Adachi, Kato, Onuma, Ito, Okazaki and Hara57 In fact, according to historical descriptions, psychoses in epilepsy seem to be characterised by low rates of unfavourable symptoms, low rates of cognitive impairment, better response to treatment and lower rates of hospitalisation. Reference Laxer, Trinka, Hirsch, Cendes, Langfitt and Delanty49,Reference Adachi, Kato, Onuma, Ito, Okazaki and Hara57 Risk factors for the development of chronic psychosis in epilepsy include temporal lobe epilepsy, at least 15 years’ duration of active disease and a family history of psychosis. Reference Adachi, Matsuura, Okubo, Oana, Takei and Kato30 Adachi et al have pointed out that the course of the disease differs between patients with interictal psychoses as compared with those with schizophrenia, with a progressive deterioration occurring only in the latter. Reference Chen, Lusicic, O’Brien, Velakoulis, Adams and Kwan58

Treatment-related psychoses

A retrospective study involving 2630 people with epilepsy between 1993 and 2015 looked specifically at the aetiology of psychotic symptoms; only one out of seven cases showed a clear temporal relationship with the treatment. All individuals showed complete remission following drug discontinuation, with risk factors including a diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy, female gender and treatment with levetiracetam. Reference Chen, Choi, Hirsch, Katz, Legge and Buchsbaum59 One US retrospective study of 4085 adults newly started on antiseizure medication (ASM) found that around 17.2% developed psychiatric side-effects with any drug, with risk factors including a diagnosis of drug-resistant epilepsy and a previous psychiatric history. Reference Mula, Kanner, Jetté and Sander60 Psychotic symptoms have been described with most ASMs; sodium channel blockers are those with the lowest risk of psychiatric side-effects. Reference Löscher and Klein61 Cenobamate has a dual mechanism of action, blocking voltage-gated sodium channels through a pronounced action on persistent rather than transient currents and acting as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors independently from the benzodiazepine binding site. Reference Roberti, De Caro, Iannone, Zaccara, Lattanzi and Russo62–Reference Klein, Krauss, Aboumatar and Kamin64 Cenobamate has shown a low prevalence of psychiatric side-effects and a good overall tolerability profile. Reference Calle-López, Ladino, Benjumea-Cuartas, Castrillón-Velilla, Téllez-Zenteno and Wolf65

With regard to ASM-related psychotic symptoms, forced normalisation plays a unique role. This is an intriguing phenomenon characterised by the emergence of psychiatric disturbances following either the establishment of seizure control or reduction in epileptic activity in an individual with previous uncontrolled epilepsy. Reference Lee, Denton, Ladino, Waterhouse, Vitali and Tellez-Zenteno66 The mechanism is still unknown, but has been described with both ASM and vagus nerve stimulation, raising the hypothesis that the phenomenon is linked to the neurobiology of seizure control. Reference Weber, Dill and Datta67,Reference Macrodimitris, Sherman, Forde, Tellez-Zenteno, Metcalfe and Hernandez-Ronquillo68 Finally, one recent systematic review clarified that forced normalisation can be seen primarily in focal epilepsies (80%) and symptomatic aetiology (44%). Reference Lee, Denton, Ladino, Waterhouse, Vitali and Tellez-Zenteno66 Studies looking at the neurobiological mechanisms of forced normalisation would be able to elucidate the neurobiological links between epilepsy and psychosis.

Postoperative de novo psychoses represent specific conditions with hitherto minimal data; epidemiological data remain sparse, but these represent a serious complication of epilepsy surgery. Reference Devinsky, Barr, Vickrey, Berg, Bazil and Pacia69–Reference Kanemoto, Tsuda, Goji, Tadokoro, Oshima and Tachimori71

Diagnosing psychotic disorders in epilepsy

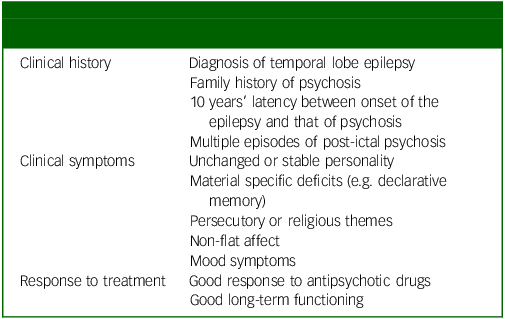

Given the complexities of clinical presentations, it can be challenging for neurologists to identify early psychotic problems, especially for those with limited psychiatric training (Table 3).

Table 3 Clinical elements requiring consideration when diagnosing interictal psychosis in epilepsy

The prompt identification of symptoms represents the foremost step for a prompt referral to psychiatric services. There is only one screening instrument proposed for the identification of psychotic symptoms in epilepsy, namely the Emotions with Persecutory Delusions Scale (EPDS). Reference Akrout Brizard, Limbu, Baeza-Velasco and Deb72 This self-reported questionnaire has shown good psychometric properties against clinical diagnosis. Nevertheless, the lack of a clear cut-off score and the complex scoring system significantly affect implementation in clinical practice. At present, there are no recommended screening instruments for psychotic symptoms in epilepsy. Clinicians, invividuals and their families need to be aware of the increased risk and potential clinical scenario, and neurologists should consider exploring with simple questions the presence of hallucinations or thought disorders for prompt referral of patients to mental health services. Patients with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy represent a unique population posing several challenges in terms of diagnosis and management of psychotic symptoms and, to date, data are still lacking. Reference Salpekar, Mula, Agrawal and Kaufman73 From a psychiatric perspective, it can be challenging for psychiatrists not trained in the neuropsychiatry of epilepsy to immediately distinguish epilepsy-related presentations (e.g. post-ictal psychosis or forced normalisation) from comorbid schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorders, and to distinguish between episodic versus chronic conditions. Understanding the nature of these conditions is vital to inform optimal treatments. The field of neuropsychiatry, as a subspecialty, clearly represents the opportunity to provide a comprehensive approach to clinical problems such as this, bridging between neurology and psychiatry. Reference Arora, Prakash, Rizzo, Blackman, David and Rogers74

Treatment issues

No evidence-based clinical practice guidelines exist for the management of psychotic symptoms in epilepsy, and evidence on the effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of psychotic symptoms in epilepsy is inconclusive. Reference Kerr, Mensah, Besag, de Toffol, Ettinger and Kanemoto75 During the past 10 years, several expert opinion papers have attempted to guide the management of these symptoms. Reference de Toffol, Trimble, Hesdorffer, Taylor, Sachdev and Clancy76,Reference Mula77 In general terms, it is reasonable to apply guidelines of treatment for psychoses outside epilepsy – keeping in mind the specific needs of this unique population of individuals, namely pharmacological interactions of psychotropic drugs with ASMs and the risk of seizure worsening with antipsychotic medications.

Interactions and seizure risk

Regarding kinetic interactions, ASMs with enzyme induction properties such as phenytoin, carbamazepine and barbiturates reduce the blood levels of almost all antipsychotic drugs. Reference Löscher and Klein61 However, this interaction is particularly relevant for quetiapine because it is metabolised only by the enzyme CYP3A4, and concomitant use with any inducer would lead to almost undetectable blood levels below 700 mg. 78 Individual differences in treatment response should be carefully considered in regard to olanzapine and clozapine, which have complex metabolisms with multiple enzymatic pathways involved. Conversely, not all antipsychotics appear to influence the enzymatic pathways of ASMs significantly and, consequently, do not appear to affect ASM blood levels. Reference Gold, Sher and Maldonado45

Data on pharmacodynamic interactions are generally limited, but it is essential to consider the implications of combining antipsychotics and ASMs with a similar spectrum of side-effects, especially for sedation, weight gain and cardiotoxicity; and the apparent risk of bone marrow suppression in regard to the combination of carbamazepine and clozapine. Reference Gold, Sher and Maldonado45

Antipsychotic drugs have always been considered as being associated with an increased risk of seizure worsening. In psychiatric practice, antipsychotic medications are mainly chosen for their side-effect profile, in particular the propensity for extrapyramidal side-effects, weight gain or arrhythmias, Reference Alper, Schwartz, Kolts and Khan79 but it is obvious that the issue of seizures is particularly evident in regard to people with epilepsy.

A systematic review of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-controlled trials of antipsychotic drugs showed that clozapine is associated with the highest risk of seizures, with a standardised incident ratio of 9.5 (7.27–12.20) as compared with placebo, and such a risk seems to be dose and titration dependent. Reference Reichelt, Efthimiou, Leucht and Schneider-Thoma80 Olanzapine and quetiapine were also considered to carry some risk, with an incident ratio in the region of 2.50 (1.58–3.74) for olanzapine and 2.05 (1.21–3.23) for quetiapine. Reference Reichelt, Efthimiou, Leucht and Schneider-Thoma80 However, a very recent network meta-analysis showed that all second-generation antipsychotics, including even clozapine, are associated with no significantly increased risk of seizure occurrence as compared with placebo. Reference Ishibashi, Horisawa, Tokuda, Ishiyama, Ogasa and Tagashira81 This discrepancy with previous studies may be related to the adoption of high dosages and rapid titrations, which are not typically current standard of care. It is important to emphasise that all the above data are derived from psychiatric samples rather than from individuals with epilepsy. It is, therefore, evident that the issue of seizures as a side-effect of antipsychotics still deserves further clarification, and careful clinical monitoring is crucial in regard to people with epilepsy and psychosis. Among recent antipsychotics, lurasidone is a dopamine type 2 (D2), serotonin type 2 (5-HT2A) and 5-HT7 receptor antagonist Reference Solmi, Fornaro, Ostinelli, Zangani, Croatto and Monaco82 and showed a favourable side-effect profile with a very low rate of side compared with placebo. Reference Trimble, Kanner and Schmitz83

Treatment duration

Regarding psychosis in epilepsy, treatment requirements and duration represent a challenge because the time course of psychosis in epilepsy differs from that of new-onset psychosis and depends on the type of psychosis (Table 2). Post-ictal psychotic episodes in epilepsy are more likely to be recurrent, while interictal psychoses are more likely to be chronic.

Regarding post-ictal psychosis, an international Delphi survey among a group of experts suggested that symptomatic antipsychotic treatment is generally warranted but should subsequently be tapered off (e.g. after some weeks), given the episodic nature of the condition. Reference de Toffol, Trimble, Hesdorffer, Taylor, Sachdev and Clancy76 Moreover, given the condition’s self-limiting time course, it must be acknowledged that, in many cases, minor episodes can also be managed by observation, nursing or carer supervision. Reference Adachi, Ito, Kanemoto, Akanuma, Okazaki and Ishida84 In many instances there is no need for long-term antipsychotic treatment, which is mainly prescribed to reduce mortality and morbidity; Reference Gold, Sher and Maldonado45 however, in one out of four cases, post-ictal psychosis may progress to a chronic psychosis, Reference Vivekananda, Cock and Mula85 and this would pose the question of long-term treatment with antipsychotics. Complete seizure control would represent the best preventive treatment for post-ictal psychoses and the long-term development of chronic psychoses. However, there are isolated case reports of individuals who developed psychosis even years following successful epilepsy surgery. Reference Vivekananda, Cock and Mula85

For other peri-ictal psychoses, psychotropic medications are not generally indicated Reference Gold, Sher and Maldonado45 and resolve with effective management of the epilepsy, with no need to treat the psychosis directly.

Finally, the treatment of chronic interictal psychosis tends to be similar to that of primary schizophrenia, i.e. long term, with preferential use of antipsychotic medications, paying attention to the risk for interactions and seizure relapse. Reference de Toffol, Trimble, Hesdorffer, Taylor, Sachdev and Clancy76,Reference Mula77 To date, no studies have specifically investigated depot or long-acting injectable antipsychotics in people with epilepsy, or whether these are associated with an increased risk of seizure deterioration as compared with oral formulations.

In conclusion, psychosis in epilepsy still represents a clinically relevant comorbidity deserving clinical attention. The relationship between these two conditions is complex and multifaceted, involving both shared neurobiological mechanisms and the impact of seizures on mental health. Epilepsy, in particular temporal lobe epilepsy, has been linked to an increased risk of psychotic disorders, but such a relationship is bidirectional. The precise mechanisms involved remain incompletely understood, but multiple factors are likely to be in play, from the involvement of specific brain structures or networks to neurochemical imbalances and individual genetic predisposition, all contributing to this co-occurrence. Treatment approaches often involve antipsychotic medications, although managing both conditions simultaneously can be challenging due to potential drug interactions and side-effects. Early identification and a holistic, individualised treatment plan are crucial for improving outcomes and quality of life for individuals affected by both epilepsy and psychosis.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ethos for managing the logistics, paper formatting and submission process.

Author contributions

M.M. wrote the first draft of the paper. M.M., A.M.K., A.H.Y., A.D.G., A.S.-B. and E.T. contributed equally to its conception and critical revision.

Funding

This work was realised with an unconditional contribution from Angelini Pharma.

Declaration of interest

M.M. received speaker fees from UCB, Bial and Angelini, consultancy fees from Bial and Angelini and MEDSCAPE and is editor-in-chief of Epilepsy & Behavior and deputy editor of BJPsych Open. A.H.Y. received fees from lectures and advisory boards from Flow Neuroscience, Novartis, Roche, Janssen, Takeda, Noema Pharma, Compass, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, LivaNova, Lundbeck, Sunovion, Servier, Livanova, Janssen, Allegan, Bionomics, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sage and Neurocentrx, and is editor of Journal of Psychopharmacology and deputy editor of BJPsych Open. A.S.-B. has received research funding from BIAL, Precisis and UNEEG, and personal honoraria for lectures or advice from Angelini Pharma, BIAL, EISAI, JAZZ Pharma, Precisis, UCB and UNEEG. E.T. received personal fees from EVER Pharma, Marinus, Arvelle, Angelini, Argenx, Medtronic, Biocodex, Bial-Portela & Cª, Newbridge, GL Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, LivaNova, Eisai, Epilog, UCB, Biogen, Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Actavis, and his institution received grants from Biogen, UCB Pharma, Eisai, Red Bull, Merck, Bayer, the European Union and FWF Österreichischer Fond zur Wissenschaftsforderung, Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung and Jubiläumsfond der Österreichischen Nationalbank (none related to the presented work). A.M.K. and A.D.G. have nothing to declare.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.