The recommended age at which solid foods should be introduced to infants has changed over time( Reference Krebs 1 ). For example, solid foods were recommended to be introduced to infants from 2 months of age in the 1950s, whereas they were recommended from 9 months of age in the early 1900s( Reference Krebs 1 ). The optimal age is still a current topic of debate( Reference Reilly and Wells 2 – Reference Koplin and Allen 4 ). In the UK, infant feeding guidelines were changed in 2003 to recommend exclusive breast feeding for the first 6 months of life, with solid foods introduced from then on alongside continued breast feeding( 5 ); before that the advice was to introduce solid foods between 4 and 6 months of age( 6 ). This change followed the Kramer & Kakuma( Reference Kramer and Kakuma 7 ) systematic review for the WHO and aligned UK recommendations with international infant feeding guidance.

Concerns have been expressed on the appropriateness of the revised infant feeding guidance in a developed and industrialised context, such as the UK( Reference Fewtrell, Wilson and Booth 3 , Reference Koplin and Allen 4 ). Some studies indicate that there may be ‘critical windows’ in infancy when children are receptive to new food flavours and textures( Reference Mennella and Beauchamp 8 – Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 ), suggesting that delaying the introduction of solid foods may lead to an aversion to certain flavours and textured foods, and possibly feeding difficulties in later childhood( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 – Reference Clark and Laing 16 ). There is also evidence showing that delaying the introduction of ‘lumpy solids’ to 9 or 10 months of age is associated with feeding difficulties in childhood( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 , Reference Coulthard, Harris and Emmett 17 ). However, to our knowledge, differences in age at introduction of any solid foods around varying ages in mid-infancy and later risk of feeding difficulties have not been evaluated.

The aim of this study was to determine whether the introduction of solid foods at or after 6 months of age is associated with feeding difficulties in later childhood. The present study was carried out using data from the Southampton Women’s Survey (SWS), which spanned the change in UK infant feeding guidance in 2003( 5 ), and the infants have been followed up in childhood. It provides an opportunity to examine differences in infant feeding practices in relation to risk of feeding difficulties assessed the same way in a large population of UK children.

Methods

The Southampton Women’s Survey

The SWS is an ongoing, prospective cohort study of 12 583 non-pregnant women aged 20–34 years, living in the city of Southampton, UK( Reference Inskip, Godfrey and Robinson 18 ). Assessments of lifestyle, diet and anthropometry were performed at study entry (April 1998–December 2002). Women enrolled in the SWS who subsequently became pregnant were followed up during pregnancy and postpartum, and the offspring have been studied through infancy and childhood. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Southampton and South West Hampshire Local Research Ethics Committee (06/Q1702/104). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating women and from a parent or guardian with parental responsibility on behalf of their children.

Measures

Maternal data

Before pregnancy, maternal socio-demographic and anthropometric data were collected through face-to-face interviews and self-completed questionnaires. Maternal educational attainment was defined in six groups according to highest academic qualification: (i) no academic qualification, (ii) General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE, approximately 16 years of age) grade D or below, (iii) GCSE grade C or above, (iv) advanced level (A-level, approximately 18 years of age) or equivalent, (v) Higher National Diploma or equivalent and (vi) degree. Pre-pregnancy height (cm) was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Harpenden; CMS Weighing Equipment Ltd), and weight (kg) was measured to the nearest 0·1 kg using a portable scale (Seca). Women were asked to remove their shoes and any heavy items of clothing or jewellery before measurements. Pre-pregnancy maternal diet was measured using an interviewer-administered, 100-item FFQ to assess habitual dietary intake over the previous 3 months( Reference Robinson, Godfrey and Osmond 19 ). Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed on reported frequencies of consumption of forty-eight foods and food groups derived from the FFQ, based on the correlation matrix to adjust for unequal variances of the original variables score( Reference Crozier, Robinson and Borland 20 ). The first principal component identified a pattern that was consistent with UK dietary recommendations( 21 , 22 ). From this pattern, ‘prudent’ diet scores before pregnancy were calculated by multiplying the coefficients from the PCA by each woman’s standardised reported frequencies of pre-pregnancy consumption and were interpreted as a measure of diet ‘quality’( Reference Crozier, Robinson and Borland 20 ). Among women who became pregnant, smoking status (yes, no) in pregnancy was ascertained at the 11- and 34-week interviews. Maternal employment was ascertained at the 2-year follow-up, with women being asked whether they were ‘in paid employment or self-employment in the week ending last Sunday’. Information on parenting difficulties was collected at 3 years using a thirty-item Child–Parent Relationship Scale( Reference Pianta 23 ). The questionnaire responses were summed to obtain a ‘closeness’ score and a ‘conflicts’ score.

Children’s data

At birth, infant sex was recorded, and each baby was weighed, to the nearest gram, using calibrated digital scales (Seca). Gestational age at birth was determined using a computerised algorithm based on menstrual data or, when these were uncertain, with ultrasound assessment of fetal anthropometry in early pregnancy( Reference Robinson, Crozier and Harvey 24 ). Each mother–child pair was visited within 2 weeks of the infants attaining 6 months of age, and within a period of 2 weeks before and up to 3 weeks after their first birthday, when the primary caregiver was interviewed by a trained research nurse. Details of the infant’s milk-feeding history over the preceding 6 months and the age or date at which solid foods were first introduced into the infant’s diet were recorded at these 6- and 12-month visits. Duration of breast feeding was defined according to the date of the last breast feed.

When the children were aged 3 years, data were collected on the number of eating occasions (meals) per day, and dietary intake over the preceding 3 months was assessed using an eighty-item FFQ( Reference Jarman, Fisk and Ntani 25 ) completed by the child’s main carer. Prompt cards were used to show the foods included in each food group to ensure standardised responses to the FFQ. The average frequency of consumption of the listed foods was recorded, and a prudent diet score was calculated for each child using the same procedure as for the mothers’ diets( Reference Jarman, Fisk and Ntani 25 ). The scores describe compliance with the ‘prudent’ dietary pattern (characterised by high consumption of fruits, vegetables, water and wholemeal cereals) and were used as an indicator of the quality of the children’s diets( Reference Jarman, Fisk and Ntani 25 ).

Child outcome data

Data on child feeding difficulty at 3 years of age were collected through a questionnaire developed for the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) study( 26 ). In the questionnaire, mothers/carers were asked to rate six questions on potential feeding difficulties of their child on a four-point Likert scale, including one general question ((1) whether they felt there had been difficulties feeding their child) and five more specific feeding difficulty questions ((2) not eating sufficient amounts of food, (3) refusal to eat the right food, (4) being choosy with food, (5) over-eating and (6) being difficult to get into a feeding routine). Possible response options included: (1) ‘yes, worried me greatly’; (2) ‘yes, worried me a bit’; (3) ‘yes, but did not worry me’; and (4) ‘no, did not happen’, which were converted into a binary score to indicate whether feeding difficulties did (1–3) or did not occur (4). Weight was measured using portable scales (Seca) to the nearest 0·1 kg and height using Leicester Height measurer to the nearest 0·1 cm at 3 years of age. Child BMI (weight (kg)/height (m2)) was calculated. Overweight and obesity were defined according to the International Obesity Task Force child cut points( Reference Cole, Bellizzi and Flegal 27 ) and collapsed to a binary variable: ‘overweight/obese’ and ‘not overweight/obese’.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp LP). Descriptive data are presented as mean values and standard deviations or as medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and are presented as percentages of subjects for categorical variables. Significance levels were set at P<0·05. Children were categorised into three groups according to whether they were introduced to solid foods prior to 4 months of age, between 4 and less than 6 months (reference group), and at or after 6 months of age. To compare the characteristics of mothers and children included in the analysis with those for live singleton term births not in the study, t tests (for normally distributed variables), Mann–Whitney U tests (for non-normally distributed variables) and χ 2 tests (for categorical variables) were used. Unadjusted associations between maternal and childhood characteristics and age at introduction of solids were made using Pearson’s correlation (for normally distributed variables), Spearman’s correlation (for non-normally distributed variables) and t tests (for binary variables). The six feeding difficulty questions were assessed separately. In regression analyses, age at introduction of solids was considered as a categorical variable (with ≥4 and <6 months as the reference) and a continuous variable in weeks. Age at introduction of solids as a predictor of feeding difficulties was examined by fitting a Poisson regression model with robust standard errors, adjusting for age last breast fed, child sex, gestation, parity, pre-pregnancy maternal BMI, maternal age, maternal education, maternal employment, parenting difficulties and maternal diet quality. A directed acyclic graphic (a graphical representation of causal assumptions) was used to identify potential confounding variables (see online Supplementary material File S1). Relative risk and 95 % CI are presented.

Results

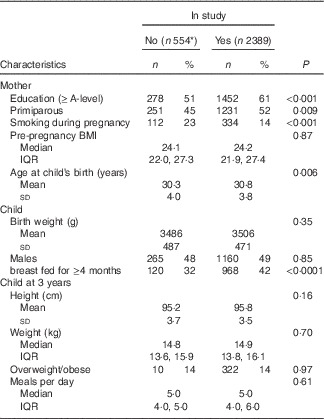

A total of 3158 live births were recorded in the SWS. Of these, there were eight neonatal deaths, and seven babies were born with major congenital growth abnormalities. In all, 200 babies were born pre-term, leaving 2943 term (after 37 weeks of gestation), live, singleton births. Of these, 194 babies had no information about age at starting solids, either because the 6-month questionnaire had not been completed (n 161) or information about the age at starting solids was not reported in either the 6- or 12-month questionnaire (n 33). One mother reported that her child started solid foods at 1 year of age, which was considered an outlier and removed from the analysis. Of these 2748 babies, 359 had no information on feeding behaviours, leaving 2389 in the final sample. Of the final sample, 55 % (n 1319) reached 4 months of age (former recommended age to introduce solids) before the change in guidance in May 2003. Mother–child pairs excluded from the analysis were more likely to have a lower maternal education level (P<0·001), be multiparous (P=0·009), have smoked during pregnancy (P<0·001) and to be slightly younger (P=0·006); infants were less likely to have been breast fed for at least 4 months (P<0·001) compared with mother–child pairs included in the analysis (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of mothers and children included the study compared with term, live, singleton births not included in the study (Numbers and percentages; medians and interquartile ranges (IQR); mean values and standard deviations)

* For some analyses total ‘n’ is much lower, particularly for the 3-year variables where ‘n’ is approximately 70.

Maternal and child characteristics and the age at introduction of solids

The distribution of the age at introduction of solids before and after the change in feeding guidance in May 2003 is shown in the online Supplementary material (File S2). There was a small shift in the distribution of the age at introduction of solids before and after the infant feeding guidelines changed. In total, 45 % (n 1070) of children were born before May 2013. Before May 2003, 61 % of infants were introduced to solid foods between 4 and 6 months and 39 % before 4 months. A few infants (0·1 %) were introduced to solid foods at or after 6 months of age. After the guidelines were revised, a greater proportion of infants were introduced to solids at or after 6 months (8 %); however, a larger proportion of infants were introduced to solids between 4 and 6 months (75 %), and the proportion introduced to solids before 4 months fell to 17 %. Overall, 95 % of mothers reported introducing solids before 6 months of age. The infants were grouped according to their age at introduction of solids; maternal and child characteristics according to these groups are presented in Table 2. All maternal and child factors considered were associated with the timing of introducing solids, with the exception of the proportion of children who were overweight or obese at 3 years. Earlier introduction of solids was observed among younger, multiparous mothers with lower educational attainment who continued to smoke during pregnancy. Earlier age at introduction of solid foods was associated with shorter duration of breast feeding and was more common in boys and among babies of higher birth weight, and after accounting for sex the association with birth weight remained (P<0·001; not reported in table). Differences in feeding practice at 3 years were found, such that earlier introduction to solid foods was associated with poorer diet quality and with small differences in eating frequency at this age.

Table 2 Characteristics of 2389 mother–child pairs according to age at introduction of solid foods in infancy (Numbers and percentages; mean values and standard deviations; medians and interquartile range (IQR))

Feeding difficulties at 3 years of age

Rates of feeding difficulties are reported in Fig. 1. The majority of mothers/carers (61 %) reported some feeding difficulties in their child at 3 years of age. In response to questions about specific aspects of feeding difficulties, the majority of mothers/carers reported difficulties with their child eating enough food (61 %), eating the right food (66 %) and being choosy with food (74 %). However, of those who did report difficulty for these feeding aspects, the majority of mothers/carers indicated that they were not worried about the feeding issue. Over-eating and problems with establishing a routine were less common, with just 16 and 21 % of mothers/carers reporting these feeding difficulties, respectively.

Fig. 1 Proportion of reported child feeding issues at 3 years of age. (a) Proportion of parents reporting general feeding difficulties in their child at 3 years of age. (b) Proportion of parents reporting that their child had not eaten a sufficient amount of food at 3 years of age. (c) Proportion of parents reporting that their child refused to eat the right food at 3 years of age. (d) Proportion of parents reporting that their child had been choosy with food at 3 years of age. (e) Proportion of parents reporting that their child had over-eaten food at 3 years of age. (f) Proportion of parents reporting that it had been difficult to get their child in to an eating routine at 3 years of age.

Association between age at introduction of solids and risk of feeding difficulties at 3 years of age

The relative risks of feeding difficulties at 3 years of age according to the age at introduction of solid foods are presented in Table 3. Infants were grouped according to whether they were introduced to solid foods (i) before 4 months, (ii) between 4 and 6 months (reference group) and (iii) at or after 6 months of age. The model adjusted for potential confounding variables in childhood (age last breast fed, gestation, sex) as well as maternal variables (pre-pregnancy BMI, age, parity, education, employment, parenting difficulties and diet quality). There were no differences between the three feeding groups for the five specific feeding difficulties of not eating sufficient foods, refusing to eat the right food, being choosy with food, overeating or being difficult to get into an eating routine in the adjusted model. However, a significant association between the general feeding difficulty question and age of introducing solids was found. After taking account potential confounding factors, children who were introduced to solid foods at or after 6 months of age had a lower relative risk of feeding difficulties (RR 0·73; 95 % CI 0·59, 0·91, P=0·004) than children who were introduced to solids between 4 and 6 months of age.

Table 3 Relative risk (RR) of feeding difficulties at 3 years of age according to age at introduction of solid foods in infancy (Unadjusted and adjusted relative risks and 95 % confidence intervals)

* Model adjusted for age last breast fed, gestation, maternal BMI, maternal age, maternal education, maternal employment, parenting difficulties, parity, sex and maternal diet.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess whether age at introduction of solid foods was associated with feeding difficulties in a large population of children aged 3 years. The principal finding was that general feeding difficulties were reported to be less common among infants who were introduced to solid foods at or after 6 months of age; this association was not explained by differences in maternal and background characteristics. There were no other significant associations between the age of introducing solids and the risk of difficulties in specific aspects of feeding at 3 years. Male and larger babies were more likely to be introduced to solid foods earlier, consistent with findings from the Millennium babies study( Reference Wright, Parkinson and Drewett 28 ). The tendency to introduce solid foods earlier to boys may be partly due to their larger size and consequently higher energy requirements and feeding drive( Reference Wright, Parkinson and Drewett 28 ), although after accounting for sex the association with birth weight remained. The magnitude of the change in distribution of the age at introduction of solids following the change in infant feeding guidelines in May 2003 was small but distinct. Although the majority of mothers/carers still introduced solids between 4 and 6 months (before May 2003=61 %; after May 2003=75 %), fewer infants were introduced to solids before 4 months (from 39 to 17 %) and more infants were introduced to solids at or after 6 months of age (from 0·1 to 8 %).

Existing evidence on the timing of introducing solid foods in infancy and later risk of feeding difficulties is limited and is a current topic of debate. There is growing evidence on the programming of flavour preferences and its influence on later food choices, particularly flavour preferences developed through exposure to breast milk( Reference Forestell and Mennella 29 ) or formula milk in early life( Reference Mennella, Griffin and Beauchamp 9 , Reference Mennella and Beauchamp 30 , Reference Mennella, Forestell and Morgan 31 ). However, much less is known about children with feeding difficulties specifically in relation to the timing of introducing solid foods. The evidence base on feeding difficulties includes animal experiments and a human case study( Reference Illingworth and Lister 11 ), as well as observational studies prone to confounding issues( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 , Reference Coulthard, Harris and Emmett 14 ). Follow-up studies of feeding difficulties have been conducted in children who were tube-fed before introducing solids( Reference Mason, Harris and Blissett 12 ); however, these findings are unlikely to be generalisable to a healthy population. Caution should be taken in drawing conclusions from this evidence base.

There are therefore very few studies that can be compared directly with the SWS. The most relevant data have come from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood (ALSPAC), in which feeding difficulties in childhood were assessed using the same questions, although the follow-up studies were conducted at different ages (6 and 15 months( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 ) and 7 years( Reference Coulthard, Harris and Emmett 14 )). In addition, an important difference in the ALSPAC analyses was that the infant feeding exposure used was the age at which lumpy solids were introduced (<6 months; 6–9 months; 10+ months)( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 ), whereas the present analyses considered introduction of any solid foods. Introduction of lumpy solid foods before 6 months of age in ALSPAC was associated with a lower likelihood of reporting four of the specific feeding difficulties at 15 months of age, when compared with introduction between 6 and 9 months( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 ), but the relative risk of over-eating in this group was higher( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 ). When the children were 7 years old, reported feeding difficulties were most common in relation to late (10+ months) introduction of solid foods( Reference Coulthard, Harris and Emmett 14 ); there were a few differences between the children fed lumpy foods before 6 months when compared with the 6–9-month group. The authors suggest that the data provide evidence to support a sensitive period in the 1st year, when infants may be more likely to accept tastes and textures. These findings are in contrast with the present study, in which there was no evidence of differences in feeding difficulties among children who were introduced to (any) solid foods later in infancy. Infants who complied with the latest feeding guidance, starting on solid foods at 6 months, had the ‘healthiest’ dietary patterns at 3 years of age (Table 2) and were reported to have fewer feeding difficulties when compared with children who had been introduced to solid foods earlier in infancy.

A high proportion of mothers/carers indicated that their child displayed some degree of feeding difficulty; however, they were ‘not worried about it’. This raises a couple of questions: first, whether the mother/carer was not concerned as the specific feeding difficulty was infrequent, or whether the feeding difficulty was regularly encountered but the mother/carer was not concerned about the issue. If the latter, then it would be interesting to understand why some mothers/carers are not concerned about feeding difficulties in their child. Although there were significant associations between the timing of introducing solids and risk of feeding difficulties assessed through the general question, no significant associations were detected through the five more-specific, feeding difficulty questions. It may be that an additive effect was observed in that there were small differences in each of the specific feeding difficulties, which only led to a significant association when assessed through the general feeding difficulty question. Or it may be that there was a specific aspect of feeding difficulties that was not assessed through the individual-specific questions (e.g. a child taking a considerable amount of time to eat a meal).

Recommendations for practice

Although 86 % of UK mothers report a good understanding of the WHO infant feeding recommendations( Reference Moore, Milligan and Goff 32 ) and the majority express an initial desire to comply, some mothers report that waiting to introduce solids until 6 months is challenging( Reference Walsh, Kearney and Dennis 33 , Reference Hoddinott, Craig and Britten 34 ). The 2010 UK Infant Feeding Survey found that 94 % of mothers reported introducing solids before 6 months of age( 35 ), consistent with the SWS findings (95 %). Similar trends have been reported in other developed countries that have adopted the WHO infant feeding recommendation, including the USA( Reference Clayton, Li and Perrine 36 ) and Australia( Reference Scott, Binns and Graham 37 ). The small proportion of mothers meeting the infant feeding recommendation internationally indicates that additional efforts and resources are required to support mothers. Evidence from the SWS and other studies indicate that younger mothers, with a lower education level, who had a higher pre-pregnancy BMI and smoked during pregnancy, are more likely to introduce solid foods to infants earlier than recommended( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 , Reference Scott, Binns and Graham 37 – Reference Rebhan, Kohlhuber and Schwegler 39 ), and are a high risk subgroup who could benefit from additional support during the first 6 months of motherhood.

Strengths and weaknesses

The present study has several strengths. In the SWS, young women were recruited from the general population regardless of whether they were planning a pregnancy, making the SWS study unique in the Western world. The SWS provided a novel opportunity to examine differences in age at introduction of solid foods within a longitudinal study that spanned the 2003 change in infant feeding recommendations in the UK, thus providing a wide range of ages of introduction of solids. The study has a large sample size and assessed the outcome of feeding difficulties in children using a previously developed questionnaire( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 ), enabling the comparison of findings between feeding difficulty studies. However, it is a limitation that a binary outcome to indicate the presence or absence of each feeding problem was used, in order to avoid any subjective reporting bias associated with perceived severity of the feeding difficulty. Future studies that use other feeding difficulty questionnaires and alternate methods of classifying the presence of a feeding difficulty will be needed to confirm and extend our findings. Other limitations of the study also need to be acknowledged. As with other infant feeding studies( Reference Northstone, Emmett and Nethersole 10 , Reference Coulthard, Harris and Emmett 14 ), parental report data on infant feeding methods and feeding difficulties were collected that could be prone to misreporting and a social desirability bias. In all, 81 % of the pregnant cohort who gave birth to healthy, term, live, singleton births were included in the study, and there were significant differences between mother–child pairs that were included and excluded from the analysis. Owing to the change in infant feeding policy, almost all infants in the ‘at or after 6 month’ group were born later in the study, which may have implications for the findings. Only a small proportion of mothers reported introducing solid foods to infants at or after 6 months of age (5 %, n 110). It will be important in future studies to extend and replicate these findings in a more balanced analysis, with similar numbers of children in each group. Future studies could also examine the association between weaning methods (e.g. baby-led weaning) and risk of feeding difficulties, which was not assessed in the SWS. Care should be taken in interpreting the findings as they may not be generalisable outside the UK. Despite adjusting for potential confounders, some confounders may have been missed. For example, the model adjusted for duration of breast feeding, but we did not consider whether effects differed between infants who were partially or exclusively breast fed, which should be addressed in future studies. A causal pathway cannot be assumed because of the observational nature of the SWS. Further research may be needed to ascertain causal mechanisms to determine the optimum age to introduce solid foods in relation to other infant outcomes (such as allergies, asthma, overweight and obesity, and iron status) that were outside the scope of this study.

Conclusions

Since the revision of the infant feeding recommendations 13 years ago, there has been continued debate on the evidence behind the change in recommendations. Questions have been raised as to whether the delayed introduction of solid foods to 6 months of age leads to an aversion to certain flavours and textured foods and possibly feeding difficulties in later childhood. Evidence from the SWS showed few associations between age at introduction of solid foods and feeding difficulties in childhood, although general feeding difficulties were less common among children who were introduced to solid foods at or after 6 months of age, in line with current UK feeding policy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the women of Southampton and their children who gave their time to take part in these studies and to the research nurses and other staff who collected and processed the data.

This work was supported by grants from the UK Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, UK Foods Standard Agency, the Dunhill Medical Trust, the National Institute for Health Research through the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and projects EarlyNutrition and ODIN (under grant agreement numbers 289346 and 613977). J. L. H. received an Endeavour Research Fellowship funded by the Australian Government (Department of Education and Training).

J. L. H., S. R. C., H. M. I., C. C., K. M. G. and S. M. R. were responsible for the design of the study and formulated the research questions. S. R. C. analysed the data and J. L. H. drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors are responsible for drafting and revising the manuscript and have approved the final version.

K. M. G. has received reimbursement for speaking at conferences sponsored by companies selling nutritional products; K. M. G., H. M. I. and C. C. are part of an academic consortium that has received research funding from Abbot Nutrition, Nestec and Danone. None of the other authors had any potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1017/S0007114516002531