Poor diet is recognised as a major risk factor for ill health and premature death(Reference Scarborough, Bhatnagar and Wickramasinghe1,Reference Murray, Aravkin and Zheng2) . In 2018, just 28 % of adults and 18 % of children (5–15 years) in England were eating the recommended five portions of fruits and vegetables a day, and mean intake of free sugars and SFA exceeded recommendations in all age groups(3). Further, few people were meeting targets for salt, fibre and excess energy intake(4,5) . Between 2006 and 2020, voluntary government salt, sugar and energy reduction programmes were introduced in the UK as part of a comprehensive strategy to encourage reformulation of products contributing substantially to intakes of the targeted nutrients and where reformulation is possible(5–8).

About two-thirds (64 %) of adults in England are living with overweight or obesity(9), and one in three children leave primary school (aged 11 years) with overweight or obesity(10). As of 2020, the annual full cost of obesity in the UK has been estimated at £58 billion (about 3 % of the UK’s Gross Domestic Product), with an estimated £6·5 billion spent each year on treating obesity-related disease(Reference Bell11). Obesogenic food environments, characterised in part by the presence of extensive marketing of foods and beverages (hereafter: foods) high in saturated fat, sugar and/or salt (HFSS), are thought to be a key driver of rising levels of obesity worldwide(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall12). The recent National Food Strategy acknowledged that most marketing money is spent promoting unhealthy (HFSS) products, with 32 % of spend on brand-only advertising(Reference Dimbleby13). Digital advertising spend in the UK, as globally, is substantial and growing(Reference Tatlow-Golden and Parker14).

The WHO has set out recommendations and frameworks to guide Member States in the development and implementation of policies to restrict food marketing(15–17). While implementation of the WHO recommendations has been inconsistent(18,Reference Taillie, Grummon and Fleischhacker19) , a recent systematic review and analysis of implemented policies demonstrated that mandatory policies (more often than voluntary measures from industry) can achieve meaningful reductions in food marketing exposure and power, as well as reducing purchasing of unhealthy foods(Reference Boyland, McGale and Maden20).

Chile’s 2016 Food Labelling and Advertising law banned all unhealthy food marketing ‘directed to’ or ‘intended for’ children under 14 years, including via the Internet. A second phase extended the television advertising restrictions to cover 06.00–22.00 on all channels. Evaluations indicate this has effectively reduced children’s exposure to unhealthy food advertising(Reference Dillman Carpentier, Mediano Stoltze and Reyes21) and may have contributed to declines in unhealthy food consumption in young children(Reference Jensen, Carpentier and Adair22). In 2020, the UK Government launched a new obesity strategy(23) which included a number of measures designed to ‘help people live healthier lives’, including energy labelling for out-of-home food businesses, consultations on front-of-pack and alcohol energy labelling, and HFSS volume promotion and placement restrictions. Alongside these measures, the government announced its intention to ban HFSS products being marketed on TV before 21.00 and ban all paid-for HFSS food marketing online. The UK approach to legislation has been assessed to be comprehensive and more likely than other approaches (such as those in Chile and Canada) to meet its regulatory objectives(Reference Sing, Reeve and Backholer24), but implementation has been delayed until October 2025.

Over recent decades, increasing evidence has been accrued to demonstrate that the marketing and advertising practices of transnational food companies affect the attitudes, preferences, choices and eating behaviours of children(Reference Boyland, Nolan and Kelly25–Reference Boyland, McGale and Maden28) and adolescents(Reference Qutteina, De Backer and Smits29), as well as shaping social and cultural norms for entire populations(Reference Cairns30). Evidence supports ‘a hierarchy of effects’ of food marketing, that is, that exposure sequentially affects immediate outcomes such as attitudes and behaviours, and later weight-related outcomes(Reference Kelly, King and Chapman31).

However, much of this evidence relates to television food advertising(Reference Kelly, King and Chapman31) or individual forms of digital media such as advergames(Reference Folkvord and van’t Riet32) or social media(Reference Mc Carthy, de Vries and Mackenbach33). Television food advertising, while still extensive worldwide(Reference Kelly, Vandevijvere and Ng34), may no longer be the dominant form of marketing exposure for young people as time spent using digital media has overtaken that of TV viewing(35). In recent years, there has been extensive digital media take up and use in adults and children in the UK(35,36) . Previous reviews have noted that understanding of the impact of food marketing in all digital spaces is crucial(8,37) , particularly when sociodemographic differences in digital media use suggest the potential for it to widen health inequalities(Reference Rummo, Arshonsky and Sharkey38,Reference Pollack, Gilbert-Diamond and Emond39) . A 2015 evidence review by Public Health England (PHE)(8) reported on the findings of forty-five primary research articles on food marketing published between 2010 and 2014; here, it was noted that there was a dearth of evidence of impact of marketing from new and emerging strategies such as digital media and sponsorship. Furthermore, many reviews focus only on the effects on young people(Reference Boyland, McGale and Maden28), and not adults, which has implications for the comprehensiveness of health impact assessments for food marketing policies(40).

The aim of this systematic review was to provide an updated synthesis of the evidence since 2014 for behavioural and health impacts of food marketing on both children and adults, using the 4P’s framework (Promotion (e.g. advertising), Product (e.g. product design and packaging), Price (e.g. price-setting and discounts) and Place (e.g. location of products)). The 4Ps are frequently identified by systems mapping activities as being critical to successful obesity prevention at the population level(Reference McGlashan, Hayward and Brown41). The framework was used for consistency with, and to build directly on, the previous PHE review that adopted this approach(8).

Methods

This systematic review was preregistered on the PROSPERO database (CRD420212337093) and was reported in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)(Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt42) and MOOSE(Reference Stroup, Berlin and Morton43) guidelines (see online Supplementary File 1 for completed checklists) and the systematic review quality criteria of the updated AMSTAR tool(Reference Shea, Reeves and Wells44). An amendment to the original protocol is described in online Supplementary File 2. The methods used in the current review are largely consistent with those used in the 2015 review(8), although there are some differences in the search terms and inclusion criteria between the two reviews, reflective of the differing scopes (e.g. the focus solely on sugary foods and drinks in the earlier review, and inclusion of outcomes relating to dental health and non-communicable disease).

Search strategy

Searches were undertaken in MEDLINE, CINAHL, APA PsycInfo, Web of Science (all databases), EMBASE, ERIC, The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), Health Management Information Consortium, Communication & Mass Media Complete and Academic Search Complete using a comprehensive search strategy where search terms were refined from(8) to reflect the updated scope (online Supplementary File 2). Searches sought to identify studies added to databases from 1 October 2014 to January 2021 (i.e. recent evidence published after that included in ref. 8). Searches were conducted by an experienced information specialist (M.M. (Maden)). We conducted focused searches across grey literature, including key government and organisation websites, and Google Scholar. We also hand-searched the reference lists of relevant reviews captured by the searches and eligible articles. For publications with insufficient or missing information, email contact was attempted with corresponding authors a maximum of two times, three weeks apart.

Study selection

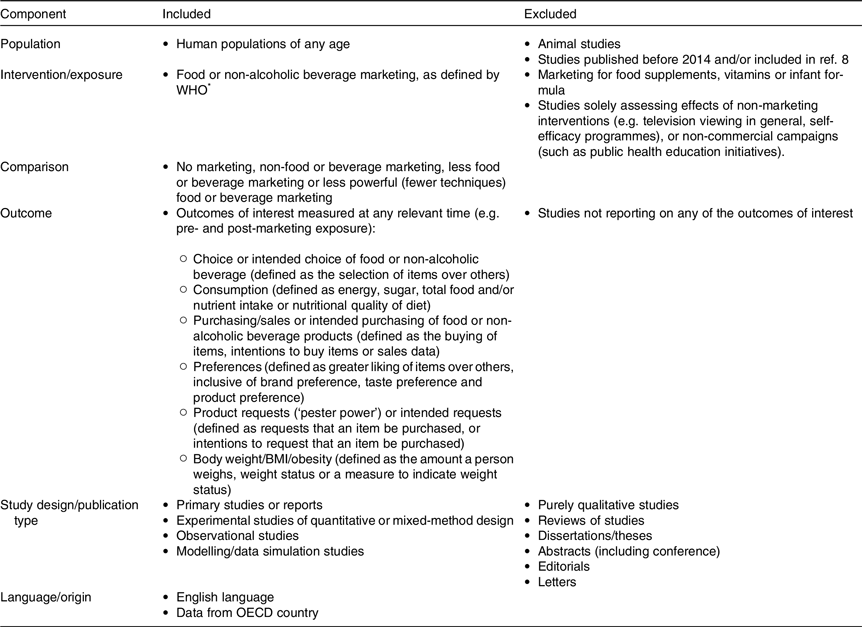

To be considered for inclusion, studies were required to meet the eligibility criteria set out in the Participant, Intervention/exposure, Comparator, Outcome, Study Design (PICOS) framework (Table 1). Studies were included if they provided quantitative data on one or more of the outcomes of interest (as defined in Table 1) in humans (any age) following exposure to unhealthy (as defined by study authors, relevant descriptors included HFSS, ultra-processed, discretionary and ‘high-in’ products) food marketing compared with a relevant comparator exposure. Types of articles included were primary data articles reporting experimental studies of quantitative or mixed-method design (including randomised controlled trials (RCT), pre-post designs and quasi experimental studies), observational studies (cross-sectional or longitudinal) and modelling/simulation studies. Excluded study and article types were qualitative studies, reviews, conference abstracts, dissertations, editorials, and letters to the editor.

Table 1. PICOS: inclusion and exclusion criteria of the review

OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

* WHO (2010). Set of recommendations for the marketing of food and non-alcoholic beverages to children. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241500210_eng.pdf

Articles retrieved from searches were uploaded into Endnote (Clarivate, Philadelphia, 2013) and duplicates removed. The Endnote library was exported to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation) for screening in two phases: (i) title/abstract screening and (ii) full text screening. Screening of each record was undertaken independently by at least two researchers from a pool of five (M.M. (Muc), J.M., J.S., A.C. and E.B.). Disagreements on inclusion or exclusion of studies were resolved through discussion, if necessary, a third reviewer was consulted. The reasons for exclusion of studies at full text were recorded.

Data extraction

Data extraction was undertaken by one researcher and independently checked in full by a second (M.M. (Muc), J.S., A.C. and E.B.) using standardised data extraction templates. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. The following data were extracted: reference (author, year and country), study funding, conflicts of interest, study design and methods, participant characteristics (where possible data relating to equity characteristics according to PROGRESS-Plus(Reference O’Neill, Tabish and Welch45)), relevant outcome measures and effect estimates (e.g. OR and risk ratios).

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed by one reviewer and independently checked in full for agreement by a second. Quality assessment was undertaken using the Cochrane risk of bias (RoB2) tool for RCT(46) and Newcastle–Ottawa scale for non-randomised studies(Reference Wells, Shea and D’Connell47). Modelling/simulation studies did not undergo a quality assessment due to the lack of an appropriate tool given the heterogeneity of study design and focus.

Data analysis

The decision was taken to not conduct meta-analyses where there were too few available effect sizes (≤ 5) to create a robust pooled effect size or to explore sources of heterogeneity. Analyses with small numbers of effect sizes would be more adversely affected by outlying effects which might lead to incorrect conclusions being drawn. We conducted meta-analytic power analysis for the effect on consumption using the ‘power.analysis’ function from the ‘dmetar’ package. We assumed a pooled effect of standardised mean difference (SMD) about 0·37, with twenty effect sizes, and approximately twenty in each condition, and the presence of heterogeneity, based on previous work(Reference Boyland, Nolan and Kelly25). This would provide us 95·6 % power.

Random effects restricted maximum likelihood estimator analyses were conducted for consumption and choice outcomes using the ‘metafor’ package in R(Reference Viechtbauer48). We fit multilevel meta-analytic models to account for some studies providing more than one effect size. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity of study results, with a value of I2 = 50 % or more indicating important or substantial heterogeneity. Where necessary, OR were converted to SMD using the formulas set out by Polanin and Snilstviet(Reference Polanin and Snilstveit49). These were handled using the R Package ‘effectsize’ and the specific command ‘odds_to_d’. Where data were not available in text but were presented in a figure, we used WebPlotDigitizer(Reference Rohatgi50) to extract the relevant information. We also converted SMD to a common language effect size to aid interpretation(Reference Mastrich and Hernandez51). Further details (and a link to the data and analysis scripts) are provided in online Supplementary File 3.

Results

Study selection

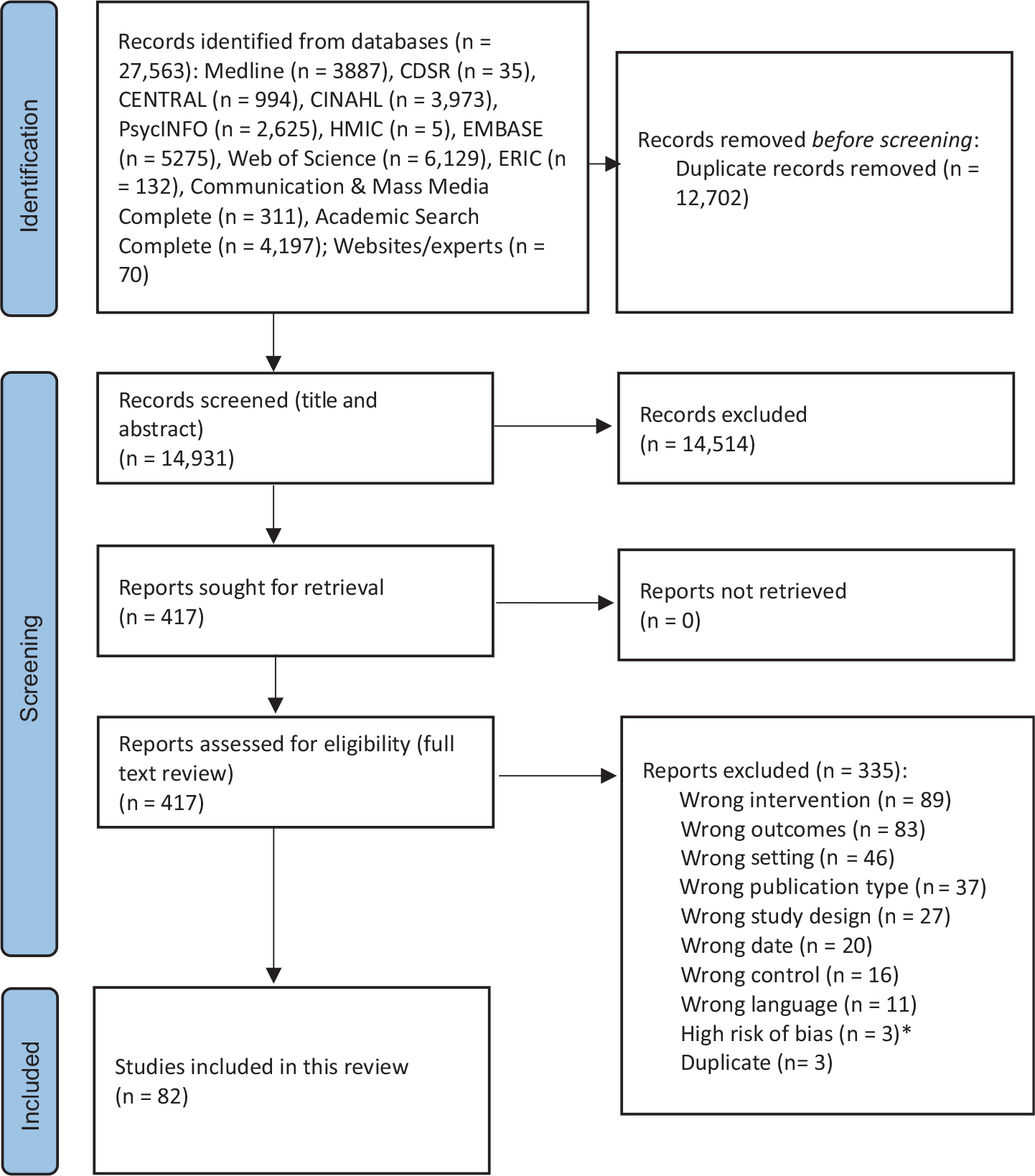

The search identified 14 931 unique titles after the removal of 12 702 duplicates. In total, 417 articles were eligible for full text screening. From this, eighty-two were included in the narrative review, of which twenty-three were also in the meta-analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow chart. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. *Papers authored by Professor Brian Wansink have been excluded on the grounds that they have a high risk of bias. To date, fifteen of his studies have been retracted because of academic misconduct1, and at least one of the studies retrieved by the searches has been found to have substantial flaws2. 1 https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/9/19/17879102/brian-wansink-cornell-food-brand-lab-retractions-jama. 2 https://www.lockhaven.edu/∼dsimanek/pseudo/cartoon_eyes.htm.

Study characteristics

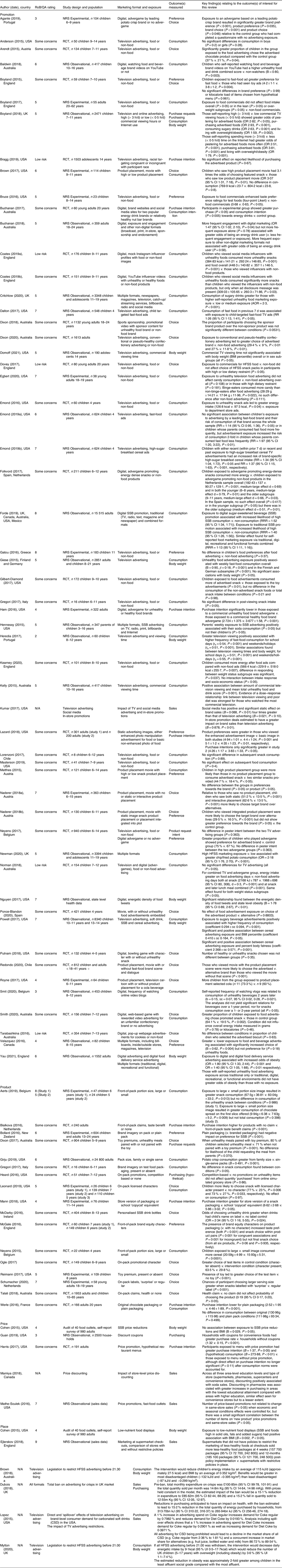

Details of all included studies, including outcomes of quality assessment, are provided in Table 2. Most (n 55) examined the food marketing in the context of ‘promotion’, n 17 explored ‘product’, n 15 studied ‘price’ and n 2 reported on ‘place’-based marketing (not mutually exclusive, some studies feature in more than one category). Not including modelling studies, publications reported on studies with child (n 48), adult (n 19), and child and adult participants (n 9, of which n 3 reported on retail sales data at the household level or above). The studies measured the relationship between food marketing and food consumption (n 38), choice (n 20), preferences (n 13), purchasing (n 12), purchase requests (n 3) and body weight (n 8) (some studies reported on more than one relevant outcome, all were included).

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies

RoB, risk of bias; QA, quality assessment.

QA scores ≤ 4 = unsatisfactory quality, 5–6 = satisfactory quality, 7–8 = good quality, 9–10 = very good quality.

RoB, risk of bias; QA, quality assessment; NRS, non-randomised studies; RCT, randomised controlled trial; HFSS, high in fat, sugar and/or salt; RR, risk ratio; RRR, relative risk ratio; AOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Publications reported on RCT (n 37), experimental non-randomised studies (NRS, defined as experimental studies where authors did not explicitly describe random allocation of participants to conditions; n 15), observational NRS (n 24, of which seven were longitudinal and the rest were cross-sectional) and modelling/simulation studies (n 6) ranging in size from small to very large (n 17 to 24 800 participants). Four simulation studies(Reference Brown, Ananthapavan and Veerman52–Reference Lopez, Liu and Zhu55) provided insight into the impact of food marketing by examining the potential effect of restrictive policies, and these are described separately (online Supplementary File 4).

Included studies provided evidence from Australia (n 11), Austria (n 4), Belgium (n 3), Canada (n 2), Chile (n 2), Finland and Germany (n 1), France (n 1), Greece (n 1), Ireland (n 1), Italy (n 1), Netherlands (n 3), Netherlands and Spain (n 1), New Zealand (n 1), Portugal (n 2), Spain (n 1), the UK (England n 8, UK-wide n 7), and the USA (n 32). Notably, all of these are high-income countries, and no included studies were conducted in low-income or middle-income economies.

Funding sources were declared for 55/82 publications. Of these, one study(Reference Lazard, Mackert and Bock56) was funded by the American Academy of Advertising, but no other explicit commercial funding was declared. All other funding was derived from research councils, banks, universities, charities, foundation trusts or government. Nine of the fifty-five publications declared that no specific funding had been received for the research.

Risk of bias assessments indicated that almost all RCT (n 32) had ‘some concerns’ of bias, with the remaining five RCT deemed to have low risk (online Supplementary File 5 Table S1). This largely reflected a lack of specific information in publications on the randomization procedure used, allocation concealment and any deviations from the intended interventions. Of the NRS (online Supplementary File 5 Tables S2–3), nine were deemed to be of unsatisfactory quality, twenty-one were satisfactory quality, eleven were good quality and one was very good quality. Quality issues in NRS related mostly to limited information being provided about participant sampling and non-respondents, while experimental studies tended to achieve higher scores due to the controlled exposures to marketing and objective measurement of outcomes compared with observational studies using self-report measures. As this review focused on a topic of contemporary public health policy relevance, all included study designs can be considered ‘good’ evidence through the lens of appropriateness(Reference Parkhurst and Abeysinghe57). However, it is notable that in both evidence hierarchies in evidence-based medicine(58) and the GRADE approach to assessing the certainty of available evidence (as applied to food marketing and eating behaviour in ref. 28, RCT are assumed to be a ‘better’ standard of evidence than observational studies. As such, an RCT with some concerns of bias would (within such frameworks) typically be considered more robust or ‘certain’ evidence than a high-quality observational study.

The results are presented as a narrative summary for each of the 4Ps followed by the quantitative syntheses for food consumption and choice. Due to the number of studies on ‘promotion’ and ‘product’, these sections are further subcategorised by marketing format. Evidence is also organised by study type and age of participants (child, adolescent and adult) and where relevant, greater prominence is given to studies of better quality. Given the volume of studies included in this synthesis, effect sizes (where reported in articles) could not always be provided in the text but are all in Table 2. Terminology is used as reported by study authors, if required further details and definitions can be found by consulting individual papers.

Promotion

Television advertising

Twenty-nine publications explored the impact of television food advertising, of which seventeen report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review.

Studies with children: randomised controlled trials (n 12)

All studies had some concerns of bias except one(Reference Norman, Kelly and McMahon59) which was low risk. Significant effects of television food advertising on relevant outcomes were reported in five of the RCT with children (participant ages ranged from 4 to 14 years), specifically that following exposure to television food advertising participants showed significantly greater preference for fast food(Reference Boyland, Kavanagh-Safran and Halford60), greater choice of advertised products over alternatives(Reference Arendt, Naderer and Abdollahi61) and increased consumption of the advertised foods and/or general snacks(Reference Kearney, Fitzgerald and Burnside62–Reference Gilbert-Diamond, Emond and Lansigan64). Eight of the RCT with children reported that there was no statistically significant effect of television food advertising on intention to request products(Reference Neyens, Smits and Boyland65), food brand preferences(Reference Boyland, Kavanagh-Safran and Halford60), choice of advertised foods over alternatives(Reference Ponce-Blandon, Pabon-Carrasco and Romero-Castillo66), or hypothetical(Reference Boyland, Kavanagh-Safran and Halford60) or actual food consumption(Reference Norman, Kelly and McMahon59,Reference Anderson, Khodabandeh and Patel67–Reference Masterson, Bermudez and Austen70) .

Studies with children: experimental studies (n 2)

One satisfactory quality experimental study in children (8–14 years) found significant effects of television food advertising on food preference, specifically enhanced taste preference for the test foods(Reference Bruce, Pruitt and Ha71), while a good quality study reported no difference in 11-year-old children’s food preferences after food advertising exposure compared with after non-food advertising(Reference Gatou, Mamai-Homata and Koletsi-Kounari72).

Studies with children: observational studies (n 7)

Of the seven observational studies conducted with children (age range 4–16 years), three were good quality. Two of these reported that television food advertising exposure was significantly associated with increased consumption of fast food (cross-sectionally)(Reference Dalton, Longacre and Drake73) and high-sugar breakfast cereals (longitudinally)(Reference Emond, Longacre and Drake74) in pre-school children. The third good quality observational study(Reference Powell, Wada and Khan75) analysed data from a longitudinal survey of 10–14-year-olds and reported that exposure to soft drink and sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) advertisements was significantly associated with higher frequency of soft drink consumption even when unexplained heterogeneity was controlled for. A significant association was also reported between food advertising exposure and greater body fatness and BMI percentile(Reference Powell, Wada and Khan75).

Three observational studies were of satisfactory quality. Two of these studies reported significant associations between television food advertising exposure and greater odds of requesting purchase of (OR 2·82) or purchasing (OR 2·93) advertised foods(Reference Boyland, Whalen and Christiansen76), greater consumption of unhealthy foods in general (OR 2·63)(Reference Boyland, Whalen and Christiansen76), poorer diet quality (in a dose–response relationship)(Reference Kelly, Freeman and King77), and greater odds of living with overweight or obesity (OR 1·59, P = 0·002)(Reference Boyland, Whalen and Christiansen76). A 1-year longitudinal study reported a significant association between food advertising exposure and greater risk of fast-food consumption only in children whose parents consumed fast food less frequently (risk ratio (RR) = 1·97)(Reference Emond, Longacre and Drake78). One cross-sectional observational study was of unsatisfactory quality (see Table 2 for results)(Reference Heredia, Hipolito and Nunes79).

Studies with children and adults: observational studies (n 1) and modelling studies (n 1)

A satisfactory quality observational study(Reference Giese, König and Tăut80) with children and adults (8–21 years) in Finland and Germany reported that unhealthy food advertising exposure was positively associated with weekly fast-food consumption, but there were no significant associations with body weight. A simulation identified that TV food advertising has a significant and strong effect in increasing demand for the advertised brand, and there is also a spillover effect whereby demand is also increased for other brands sold by the same company. Specifically, for direct effects the data showed that an increase in advertising spend on ‘regular’ Coke increases demand for that product and reduces demand for Diet Coke. The analysis including spillover effects showed that an increase in advertising spend for Diet Coke increases demand for both regular and diet Coke(Reference Lopez, Liu and Zhu55).

Studies with adolescents: randomised controlled trials (n 1) and observational studies (n 1)

An RCT with low risk of bias reported no effect of exposure to TV food advertising in which the racial targeting was either congruent with participants (actors the same race as the participants) or not (actors a different race to the participants) on 14-year-old adolescents’ likelihood of purchasing the advertised product(Reference Bragg, Miller and Kalkstein81), while a satisfactory quality cross-sectional NRS found no association between commercial TV viewing time and adolescent body weight (also 14 years)(Reference Domoff, Sutherland and Yokum82).

Studies with adults: randomised controlled trials (n 2)

An RCT with low risk of bias reported that exposure to commercials for HFSS food products compared with non-food products did not significantly affect choice of HFSS snacks in participants with high or low dietary restraint(Reference Dovey, Torab and Yen83). An online RCT with some concerns of bias reported that exposure to both conventional (promoting sensory benefits) and pseudo-healthy (promoting sensory benefits and health attributes such as ‘made with real fruit’) confectionery advertising led to significantly greater choice of the advertised brand relative to non-food advertising exposure(Reference Dixon, Scully and Wakefield84).

Studies with adults: experimental studies (n 2)

Two studies (one good quality and one satisfactory) reported that exposure to television advertising for unhealthy foods did not affect subsequent food consumption in adults(Reference Egbert, Nicholson and Sroka85,Reference Boyland, Burgon and Hardman86) .

Digital marketing: overall, websites, social media and influencers

Twelve publications explored the impact of digital food marketing, of which eleven report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review.

Studies with children: randomised controlled trials (n 3)

Two RCT (one with low risk of bias and one with some concerns of bias) reported significant effects of social media influencer marketing, via Instagram and YouTube, respectively, on food consumption in 9–11-year-olds (Reference Coates, Hardman and Halford87,Reference Coates, Hardman and Halford88) . The third RCT (low risk of bias) reported no significant difference in food choice, specifically selection of the advertised biscuit, between children (7–13 years) exposed to pop-up webpage advertisements for the biscuit or toys(Reference Tarabashkina, Quester and Crouch89).

Studies with children: Observational studies (n 3)

Two satisfactory observational studies in children (age range 7–16 years) reported significant associations between digital food marketing exposure and poorer diet quality(Reference Baldwin, Freeman and Kelly90), greater odds of requesting (OR 2·51) or purchasing (OR 3·81) advertising foods(Reference Boyland, Whalen and Christiansen76), and greater odds of living with overweight or obesity (OR = 1·79)(Reference Boyland, Whalen and Christiansen76). The results of a longitudinal study of unsatisfactory quality(Reference Smit, Buijs and van Woudenberg91) are given in Table 2.

Studies with adults: randomised controlled trials (n 3)

All three RCT on digital food marketing with adult participants had some concerns of bias. One article described two RCT funded by the American Academy of Advertising, and it reported that digital food marketing exposure (an enhanced photo manipulation advertisement for food) increased product preferences and purchase intentions(Reference Lazard, Mackert and Bock56). The other RCT reported that young adult participants exposed to the brand websites and social media sites of two popular energy drink brands showed greater purchase intention and intended consumption for energy drinks compared with the control group(Reference Buchanan, Kelly and Yeatman92).

Studies with adults: Observational studies (n 4)

A good quality observational international comparative study with adult participants from the UK, Canada, Australia, USA and Mexico(Reference Forde, White and Levy93) found that increased self-reported exposure to digital SSB promotion was associated with an increased likelihood of high SSB consumption (relative risk ratio (RRR) = 1·52). A good quality observational social media analysis study reported a positive association between the energetic density of tweets (energy content per 100 g for all foods mentioned in posts on the digital platform Twitter) and obesity prevalence in the US state where the tweet originated(Reference Nguyen, Meng and Li94).

Across two satisfactory quality observational studies, it was reported that exposure to both digital food advertising and digital food delivery service advertising were associated with increased odds of obesity (OR = 1·80 and 1·40, respectively)(Reference Yau, Adams and Boyland95), but associations between digital marketing and greater odds of being an energy drink user (OR = 1·47) were only apparent for those with more frequent engagement (such as liking or sharing posts) and not more frequent exposure alone(Reference Buchanan, Yeatman and Kelly96).

Digital marketing: game-based

Six publications explored digital game-based marketing, of which four report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review.

Studies with children: randomised controlled trials (n 4)

All RCT exploring digital game-based food marketing on outcomes in children (age range 4–14 years) had some concerns of bias. Two of these studies reported significant effects of digital game-based food marketing on preference for the advertised brand(Reference Neyens, Smits and Boyland65) and choice of the advertised snack over alternatives but not increased energy intake(Reference Smith, Kelly and Yeatman97). A third RCT reported a significant effect of exposure to an unhealthy food advergame on energy consumption in a sample of children (6–12 years) from the Netherlands (medium-large effect d => 0·60 overall and in younger and older age subgroups separately) but only in the older subgroup (d = 0·51, medium effect) in the Spanish sample. Another RCT reported no effect of digital game-based food marketing on children’s choice of healthy or unhealthy items(Reference Putnam, Cotto and Calvert98).

Studies with children: experimental studies (n 1)

This experimental study with children (6–9 years)(Reference Agante and Pascoal99) was deemed to be of unsatisfactory quality, and the results are given in Table 2.

Studies with adults: experimental studies (n 1)

This experimental study with young adults was also assessed as unsatisfactory quality(Reference Ham, Yoon and Nelson100); see Table 2 for the results.

Product placement in movies

Six publications examined product placement in movies, all six report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review. Three were RCT, all with some concerns of bias. Two RCT with children (ranging from 6 to 14 years) reported that exposure to food brand product placement significantly increased choice of the advertised snack(Reference Matthes and Naderer101,Reference Naderer, Matthes and Marquart102) but not attitudes towards the brand or product (i.e. whether they were ‘likeable’ and/or ‘funny’)(Reference Matthes and Naderer101,Reference Naderer, Matthes and Marquart102) . Another RCT with both children and adults (< 18 years to 41 years and over) reported that those viewing a movie with product placement were significantly more likely to choose the advertised brand over an alternative brand than those who had seen the same movie with that scene removed(Reference Redondo and Bernal103).

A good quality experimental study reported that product placement increased choice of the advertised snack over similar alternative snacks(Reference Naderer, Matthes and Zeller104), a satisfactory quality experimental study also reported effects on choice but not consumption(Reference Brown, Matherne and Bulik105). A third experimental study was unsatisfactory quality(Reference Royne, Kowalczyk and Levy106) (see Table 2 for results).

Sports-based marketing

One publication examined sports-based marketing; it did not report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review. The RCT, with some concerns of bias, reported that exposure to the unhealthy food brand version of a promotional video for the 2018 Commonwealth Games (v. the non-food brand version) did not affect subsequent choice of the sponsored product in young adults(Reference Dixon, Scully and Wakefield107).

Multiple marketing formats

Nine publications examined the effects of multiple marketing formats together, including various combinations of TV, digital, radio, print (e.g. magazines), recreational (e.g. leisure environments) amd functional (e.g. school, work and retail environments) advertising formats. Seven report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review.

One RCT (low risk of bias) reported that food consumption in children (7–12 years) was greater following a combination of television and online food advertising exposure (compared with non-food advertising exposure)(Reference Norman, Kelly and McMahon59).

Seven observational studies (of which only one(Reference Forde, White and Levy93) was good quality) reported on associations between combined advertising exposure from multiple sources and relevant outcomes. The good quality study reported greater exposure to food marketing to be associated with increased likelihood of high SSB consumption in an international sample of adults(Reference Forde, White and Levy93). Two satisfactory quality observational studies reported greater combined food marketing exposure to be significantly associated with food consumption in 11–19-year-old adolescents(Reference Critchlow, Bauld and Thomas108,Reference Newman, Newberry Le Vay and Critchlow109) , whereas another reported significant associations with parents’ consumption only (not that of their children aged 3–16 years)(Reference Hennessy, Bleakley and Piotrowski110) or no significant relationship with consumption in adolescents (11–19 years)(Reference Buchanan, Yeatman and Kelly96) or odds of obesity(Reference Yau, Adams and Boyland95) in adults. The results of an observational study of unsatisfactory quality(Reference Velazquez and Pasch111) are given in Table 2.

Using a modelling approach, one study reported that social media and in-store promotions had significantly greater effects on brand sales than television advertising(Reference Kumar, Choi and Greene112).

Product

Promotional characters

Three publications examined promotional characters on packaging, all three report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review. Three RCT, all with some concerns of bias, explored the impact of promotional characters on food packaging on relevant outcomes in children (age range 4–9 years). Two reported that the presence (v. absence) of promotional characters on packaging increased taste preference(Reference McGale, Halford and Harrold113) and snack choice(Reference McGale, Halford and Harrold113). Conversely, another(Reference Ogle, Graham and Lucas-Thompson114) reported that there was greater choice of test items in the character absent condition relative to when the character was present. A single article described three satisfactory quality experimental studies where children (5–7 years) were reported to be significantly more likely to choose a snack when a licensed character was present (v. absent) on the packaging, but there were no effects on consumption(Reference Leonard, Campbell and Manning115).

Product size

One publication examined product size; it reported an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review. The satisfactory quality observational study reported that adults’ crisp consumption was significantly greater from family size packs compared with single-serve packs(Reference Girju and Ratchford116).

Other packaging characteristics (such as design, personalisation, labels, size and portion size imagery)

Eleven publications examined other packaging characteristics, of which nine report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review.

Studies with children: randomised controlled trials (n 3)

All RCT had some concerns of bias and reported on outcomes in participants aged between 4 and 13 years. Choice of less healthy drinks was reported to be significantly greater when items had the child’s name added to the label (v. control; OR 2·34)(Reference McDarby, O’Hora and O’Shea117). The presence of competition-based promotions (v. no promotions) on the packaging of unhealthy items was not reported to affect the quantity of such items ‘purchased’ from an online simulated grocery store(Reference Heard, Harris and Liu118). Children exposed to a large front-of-pack portion image were reported to consume significantly more cereal than those exposed to the small image(Reference Neyens, Aerts and Smits119). There was no reported difference in snack intake between groups of children who had been exposed beforehand to the snacks in their own branded packaging or had seen them unbranded(Reference Gregori, Lorenzoni and Ballali68).

Studies with children: experimental studies (n 2)

Across two experimental studies, children (5–6 years) exposed to packaging showing larger images of the food had significantly greater total snack consumption (good quality study) and significantly greater consumption of chocolate spread on the first slice but not overall (satisfactory quality study)(Reference Aerts and Smits120). The results of an unsatisfactory quality study with adolescents(Reference Mann121) are in Table 2.

Studies with children and adults: randomised controlled trials (n 1)

In an RCT with some concerns of bias, probability of choice of the less healthy item was not significantly different whether a health claim was present or absent in either children or adults (10–65 years)(Reference Talati, Norman and Kelly122).

Studies with adolescents and adults: experimental studies (n 1)

In a satisfactory quality study, plain packaging (v. branded packaging) had a significant, negative impact on preference for SSB in teenagers and young adults (13–24 years)(Reference Bollard, Maubach and Walker123).

Studies with adults: randomised controlled trials (n 2)

In two RCT with some concerns of bias, purchase intention was higher for products with no claim (v. a front-of-pack taste benefit claim)(Reference Bialkova, Sasse and Fenko124) and lower for plain (v. original) packaging, but there was no significant difference in adults’ consumption(Reference Werle, Balbo and Caldara125).

Studies with adults: experimental studies (n 1)

In a good quality experimental study, the chances of a young adult participant choosing a larger serving size was significantly greater when snacks were labelled with ‘surprise’ compared with a regular label(Reference Schumacher, Goukens and Geyskens126)

Premium offers (toys provided with meals)

For studies of premium offers, one RCT with some concerns of bias reported that when unhealthy meals were paired with a toy premium, a significantly greater proportion of children (5–9 years) selected an unhealthy meal, compared with when unhealthy meals were not paired with a toy premium (80 % v. 71 %)(Reference Dixon, Scully and Niven127). However, there was no significant difference between conditions for likelihood of the child requesting the meal from parents. An experimental study of satisfactory quality(Reference Reimann and Lane128) reported that the inclusion of a toy with the smaller-sized meal, but not with the regular sized version, predicted smaller-sized meal choice in 9-year-old children.

Price

Five publications examined ‘price’ marketing, of which four report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review.

In an RCT with some concerns of bias, adults exposed to a menu with a price promotion had significantly greater purchase intention and (hypothetical) energetic consumption than those exposed to the menu without a price promotion(Reference Harris and Thomas129). A good quality observational study used objective data on price promotions and sales from fast-food chains and found that the number of price-based promotions was not significantly related to change in same-store sales when economic and seasonal conditions effects were controlled for, but there was a small significant correlation between the number of items on ‘new product’ price promotions and same-store sales(Reference Mathe-Soulek, Krawczyk and Harrington130). Two further observational studies were of unsatisfactory quality (Reference Guan, Atlas and Vadiveloo131,Reference Cohen, Collins and Hunter132) ; see Table 2 for results. A simulation study modelled weekly store-level sales of soda as a function of store-level price discounting, reporting that discounting in convenience stores was associated with greater increases in purchasing in areas with the lowest educational attainment (v. higher education levels), but effects were considered to be small (although test statistics were not reported)(Reference Mamiya, Moodie and Ma133).

Place

Two publications examined ‘place’ marketing; both report an impact of food marketing on an outcome of interest for this review.

One very good quality observational study demonstrated that supermarkets that did not have policies to restrict the marketing of less-healthy foods at checkouts sold significantly more less-healthy food packages both 4 weeks (157 700 packages (95 % CI 72 700, 242 800)) and 12 months (185 100 packages (95 % CI 121 700, 248 500)) post-policy implementation compared with supermarkets with restrictive policies in place(Reference Ejlerskov, Sharp and Stead134). Another observational study was of unsatisfactory quality(Reference Cohen, Collins and Hunter132), and results are shown in Table 2.

Quantitative synthesis

Where possible, research evidence was quantitatively synthesized by outcome of interest (full details of methods and results including moderation analyses are given in online Supplementary File 3). Specifically, this type of synthesis was possible for the outcomes of consumption and choice, but not for purchasing/sales, preferences, product requests or body weight/BMI.

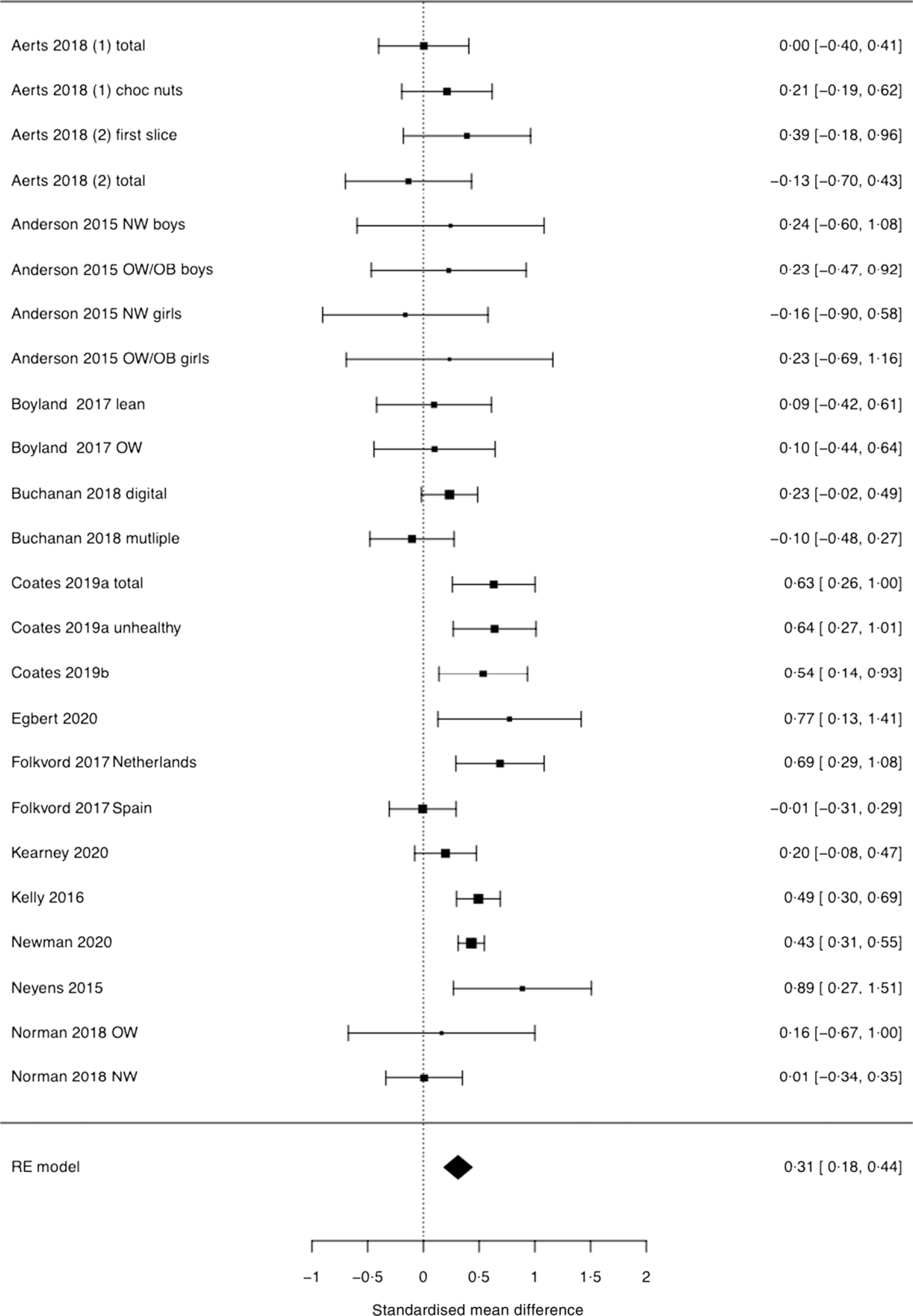

Food marketing exposure significantly increased food consumption (SMD = 0·311 (95 % CI 0·185 to 0·437), Z = 4·83, P < 0·001, I2 = 53·0 %) (Fig. 2). An SMD of 0·311 suggests that a person chosen randomly from an advertisement exposure group would be 58 % likely to consume more than a person chosen randomly from a control group. This also means that 62 % of individuals in the food advertisement groups will consume more than the control groups. The effect of food marketing on consumption was not significantly different across different marketing categories (4Ps), marketing formats (TV or digital), or by the age of participant sample (child or adult), or study quality. Additional analyses (P-curve) demonstrated that it was a likely to be a true effect (P < 0·001, online Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 2. Forest plot for pooled analysis of the effect of food marketing on food consumption.

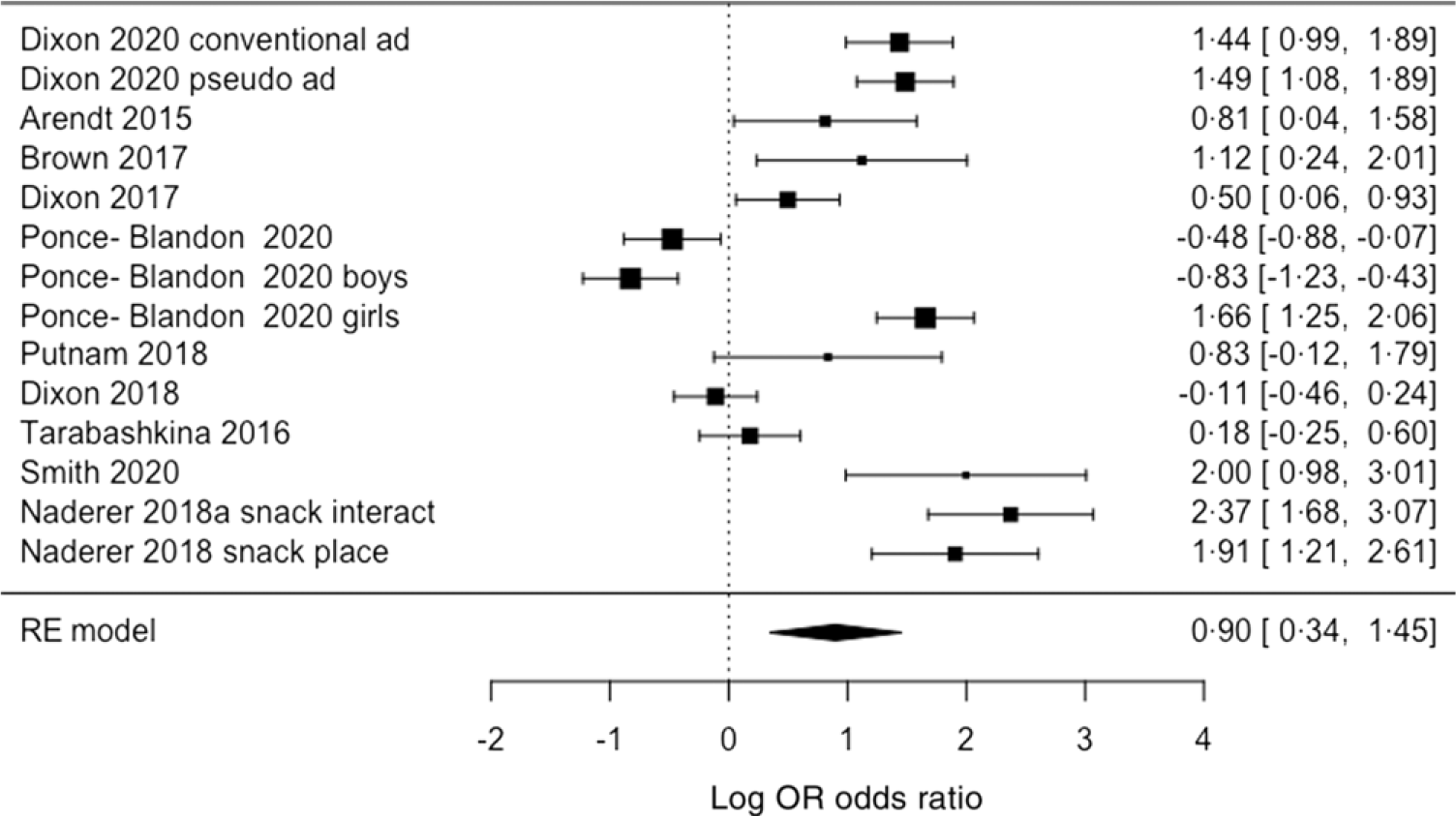

Food marketing exposure also significantly increased choice of advertised items/unhealthy foods relative to alternative/control items (OR = 2·43 (95 % CI 1·40, 4·26), Z = 3·18, P = 0·002, I2 = 93·1 %) (Fig. 3). It was not possible to check for differences by marketing category, format, participant age or study quality, but P-curve analyses demonstrated that it was likely to be a true effect (P < 0·001, online Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fig. 3. Forest plot for pooled analysis of the effect of food marketing on food choice. Explanatory note: studies assessed choice behaviour through participants pointing at images of foods, pointing at or picking up real food items, verbal choices, or hypothetical selection on paper or using computer-based tools.

Discussion

This review synthesized recent evidence from RCT and experimental and observational studies of impacts of food marketing on a range of eating and health outcomes in children and adults. It found that, while heterogeneous, there is evidence for food marketing impact on or associations with increased purchase intention, purchase requests, purchase, preference, choice, and consumption in both children and adults. While one study found a significant effect of food marketing on body fatness in children, data on body weight outcomes were relatively scarce.

The findings of this review are consistent with, and build upon, those of the previous PHE review on this topic in 2015(8). It is not possible to direct compare effect sizes between the current review and the 2015 review, as the latter did not include meta-analyses. Here, meta-analytic models and P-curve analyses added to the body of evidence indicating the significant impact of food marketing on food choice and consumption in children and adults. These findings are consistent with those previously published for limited marketing forms (e.g. television advertising, advergames and social media) and outcomes (e.g. choice(Reference Sadeghirad, Duhaney and Motaghipisheh135) and intake (Reference Boyland, Nolan and Kelly25,Reference Russell, Croker and Viner26,Reference Folkvord and van’t Riet32,Reference Mc Carthy, de Vries and Mackenbach33) ) in child populations. The current work adds additional value through the inclusion of studies with adults, data studies focused on newer formats of digital marketing (e.g. gaming) and the P-curve analyses indicate that these are not a result of selective reporting or poor analytical practices but have evidential value.

The growth of literature on the impact of digital marketing in recent years is apparent. While in the 2015 review only seven studies were identified and all focused on advergames(8), here seventeen digital marketing studies were identified, covering marketing impact from websites, social media, influencers and gaming. In both reviews, these studies demonstrated impacts of digital marketing exposures on outcomes such as food consumption, choice and preference. Although most studies included in the current review did not provide a direct comparison of the relative impact of digital marketing exposures compared with more traditional marketing approaches, previous analyses have suggested that the effect sizes for impact on diet-related behaviours are similar across both media(Reference Boyland, McGale and Maden28) and here there was also no moderating effect of marketing format for the consumption effect, that is, a subgroup analysis comparing the effect sizes for digital and TV marketing demonstrated no significant difference (results reported in the supplementary material).

Studies exploring product, price and place remain sparse (particularly relative to promotion), but the current review adds weight to what was previously known(8). A total of twenty-one studies were identified for the 3Ps (minus promotion) in the previous review(8); here, we add a further twenty-five recent studies published between 2014 and 2021. This additional evidence demonstrates that product and portion size impact on consumption, that promotional characters and other packaging characteristics affect preference and choice, and branding influences preferences and purchase intention. These overall findings are consistent with the previous review(8) and other recent more focused reviews on the influence of packaging on consumer behaviour(Reference Simmonds and Spence136). Furthermore, this review showed that both price promotion and place-based marketing impact food purchasing behaviours.

We were also able to draw upon the findings of more research conducted in the UK than was possible in the previous review (n 15 studies in this review v. n 5 previously(8)), which can support the development of UK policies based on the most relevant evidence for this population.

Several research gaps were identified. Most studies focused on school-aged children with a relative lack of data on impact of food marketing on pre-schoolers or older adolescents. There also remains a lack of evidence of impact of other food marketing approaches (such as outdoor sports-based marketing activities, and promotion via food delivery apps and video-on-demand services) and formats (e.g. audio advertising). There was also a lack of research evidence on the impact of brand-only marketing (where no product is shown, as distinct from product-based marketing). However, modelling data from Lopez et al. (Reference Lopez, Liu and Zhu55) provided useful insight by demonstrating that advertising for one brand appears to have a spillover effect on sales for other brands produced by the same company. This has implications for current UK policy proposals given that diet drinks can continue to be marketed under the new regulations. Few studies reported on impact findings disaggregated by sociodemographic characteristics (with gaps for sex including LGBTQAI+, weight status, socio-economic status and ethnicity), rather where these data were reported they were typically provided for descriptive purposes only or ‘adjusted for’ in analyses rather than group-specific analyses being undertaken. Therefore, even where these data were collected, it was not possible to demonstrate the extent to which food marketing may contribute to inequalities in health. This is also consistent with the previous review, where due to limited studies or heterogeneity of design, authors were unable to draw firm conclusions around differences by these characteristics. Future research should seek to address these limitations.

As with the previous review(8), the evidence of food marketing impact is still dominated by studies on promotion, and this remains reliant on relatively small-scale experimental studies or RCT of typically moderate quality exploring acute effects and proximal outcomes (e.g. intake) rather than effects of repeated exposure (especially via multiple different media) or with outcomes such as body weight or health. It is important to acknowledge, however, that hierarchy of effects models of food marketing dispute the idea of there being simple direct links between marketing and these more distal outcomes and instead propose that food marketing operates both directly and indirectly with effects occurring in parallel and recurringly(Reference Kelly, King and Chapman31). In addition, there is substantial complexity in the aetiology of obesity and notable methodological challenges in using health and metabolic measures beyond BMI or weight (e.g. nutritional deficiencies caused by inadequate diets) and in seeking to account for potential confounding factors in any study with body weight or related outcomes. Nevertheless, this is also a research gap that warrants attention. Similar hierarchical pathways have been proposed to explain the impact of alcohol marketing on consumption(Reference Petticrew, Shemilt and Lorenc137) which, given the known energetic contribution of alcohol to weight gain and obesity(138), may suggest that there is value in considering policies that act on food and alcohol together, or even more broadly(Reference Knai, Petticrew and Capewell139) to minimise migration of marketing from food to other harmful commodities.

This work has several strengths, including adhering to robust research integrity practices by using preregistration and the provision of open data and analysis scripts. However, the authors also acknowledge the following limitations. This review defined marketing as per the WHO framework for implementing the set of recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children(16); therefore, evidence on the impact of other marketing (such as relating to distribution channels, business to business marketing, lobbying) and broader market strategies (for a review see(Reference Wood, Williams and Nagarajan140)) was not included. It is also notable that there is considerable heterogeneity in the evidence base, likely to be a consequence of the large volume of studies and nuanced differences in study design (as has been noted elsewhere(Reference Boyland, McGale and Maden28)) which can render it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the strength of evidence in some cases. Further, there are many studies using observational methods such as recall of marketing exposure that may be inaccurate(Reference Kelly, Backholer and Boyland141) and cross-sectional designs that do not facilitate inferences of causality. This review also did not explore moderation effects by country or region as this was beyond the aims of this research.

Findings from this review are consistent with the evidence from previous reviews that marketing has an impact on diet-related behaviours in both children and adults. There is now further evidence to support an effect for television food advertising on these outcomes, but also increasing data to demonstrate that exposure to digital food marketing has similar impacts on behaviours such as purchasing and consumption. There are trends towards greater investment in digital marketing approaches that are predicted to continue over the coming years in the UK, largely reflecting global patterns. Digital food marketing regulation is necessary, and the UK’s proposals establish a crucial principle while taking an important step towards reduced exposure to unhealthy food promotion online for children and adults in the UK. Research and policy attention towards brand marketing and new digital strategies is warranted, while robust studies on the impact of marketing via outdoor and sports-based marketing are also needed to inform public health policy development.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jemma Smith for her support with article screening. The authors thank Alison Tedstone and Natasha Powell at PHE and the project Expert Advisory Group for their input.

This work was commissioned and funded by PHE. Responsibility for the project moved to the Office of Health Improvement & Disparities (OHID) on 1 October 2021. OHID had no role in the design or analysis of the study, but members of OHID staff are authors and did contribute to the interpretation of findings and the preparation of the manuscript.

E. B. conceptualized the analytical protocol, screened articles and was the primary writer. V. T. and M. Y. formulated the research questions and reviewed the search criteria. M. M. (Muc) contributed to the design of the study, screened articles, extracted data and conducted quality assessments. A. C. and J. M. screened articles and extracted data. M. M. (Maden) conducted the literature search. L. E., J. C. G. H., M. J. M., J. R. and M. T. G. contributed to the design of the study. A. J. conducted the analyses and assisted with figure creation. All authors reviewed the contents of the manuscript.

L. E. and E. B. have honorary academic contracts with OHID and have received research funding to their institution from OHID and NIHR. Jason Halford has been a consultant for Dupont, Novo Nordisk and Mars Inc., and all funds are paid to the University of Leeds. He is also an investigator on a study examining sugar replacement at the University of Liverpool funded by the American Beverage Association. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Z. H. and V. T. are, and M. Y. was when the research was conducted, employed by the Department of Health and Social Care in England. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health and Social Care.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114524000102