Overweight and obesity are defined as excessive fat accumulation that may impair health(1). The WHO(1) defines overweight as a BMI greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m². Overweight and obesity have increased in the UK since 1993(2); currently, an estimated 66·9 % of men and 59·7 % of women in England are living with overweight or obesity(3). Similarly, 60 % of adults in Wales and 66 % of adults in Scotland have overweight or obesity(4,5) . Overweight and obesity are non-communicable diseases that may increase the risk of premature mortality or co-morbidities such as CVD, type 2 diabetes and certain cancers. People with severe mental illness (SMI) are 1·8 times more likely to have obesity than the general population(6), and obesity rates in mental health secure units are 20 % higher than in the general population(Reference Day and Johnson7).

SMI includes the most serious mental health conditions that share basic characteristics including significant symptom severity, severe functional impairment and an enduring impact on a person’s daily life, defined as conditions related to schizophrenia, psychosis and bipolar disorder(8–10). In England alone, there are 490 000 people living with SMI(11,Reference Whitley, Palmer and Gunn12) .

The underlying reasons for overweight and obesity in SMI are not fully understood but include complex preventable risk factors such as poor diet, reduced physical activity and emotional eating, which often stems from feelings of worthlessness(Reference Teasdale, Samaras and Wade13–15). Access to healthy food is an issue in both inpatient and community settings(15). Inpatients are reliant on hospital food which can often be unhealthy and inappropriately portioned(15), while affordability can be a barrier to healthy food for community patients(Reference Afulani, Coleman-Jensen and Herman16,Reference Teasdale, Morell and Lappin17) . Evidence has shown that limited physical activity opportunities for inpatients may result in increased sedentary behaviour(15,Reference Stubbs and Rosenbaum18) , and in the community people with SMI are more sedentary than the general population(Reference Soundy, Wampers and Probst19,Reference Stubbs, Williams and Gaughran20) . Sedentary behaviours such as sitting and lying down(Reference Pate, O’Neill and Lobelo21) have been linked to increased odds of obesity particularly in terms of screen-based entertainment(Reference Shields and Tremblay22). Often antipsychotics can also have a sedative effect on patients, while some atypical antipsychotics, primarily olanzapine and clozapine, can also cause a lack of satiety which increases the risk of weight gain(Reference Wilton14,Reference Stubbs, Williams and Gaughran20) .

National strategies have aimed to improve mental health services in England, but challenges in system-wide implementation and the increasing prevalence of mental illness have resulted in inadequate services and worsening outcomes(11). In 2014/15, two million adults made contact with specialist mental health services and 90 % of adults with SMI accessed community services(11); however, there are variations in the implementation of existing weight management guidance for people with SMI(Reference Day and Johnson7). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance inpatient management includes regular assessment of BMI, medication and lifestyle behaviours(Reference Day and Johnson7), while more recent guidance endorses holistic and personalised approaches led by service users, for example, coproduced physical heath passports(23). Physical heath passports enable service users to set and monitor their own nutrition, physical activity and psychological needs(23). Further general guidelines for the commissioning of community Tier 2 Adult Weight Management Services recommend that services be multi-component while adhering to government dietary guidelines(Reference Coulton, Ells and Blackshaw24) and for those with mental illness, psychological therapies are also recommended when adapting weight management services(Reference Gatineau and Dent25).

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)(26) recommends Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) as a rich source of information for making health research more patient-centred. However, recent systematic reviews on weight management and SMI are restricted to randomised controlled trials (RCT)(Reference Mukundan, Faulkner and Cohn27–Reference Teasdale, Ward and Rosenbaum34). Furthermore, they focus on a single element of weight management or a single diagnosis(Reference Mukundan, Faulkner and Cohn27,Reference Stogios, Agarwal and Ahsan32,Reference Barak and Aizenberg35,Reference Grande, Bernardo and Bobes36) . Some reviews include obesity(Reference Tully, Smyth and Conway33) but not overweight, include participants with a healthy weight(Reference Mukundan, Faulkner and Cohn27,Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington37) , or do not stipulate weight or BMI thresholds(Reference Soundy, Muhamed and Stubbs29,Reference Pearsall, Thyarappa Praveen and Pelosi30,Reference Stogios, Agarwal and Ahsan32,Reference Bushe, Bradley and Doshi38) . This systematic review takes a broader approach, including a range of diagnoses, interventions and settings. A mixed methods approach was used in an attempt to capture both experimental data and the lived experience of participants.

Aim

The aim of this systematic review was to collate and synthesise the available quantitative and qualitative evidence on a broad range of weight management interventions for adults with SMI and overweight or obesity.

Review questions:

Are weight management interventions effective for adults with overweight or obesity and SMI?

Which elements of weight management interventions are effective with overweight or obesity and SMI?

What is the acceptability of weight management interventions for adults with overweight or obesity and SMI?

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

This systematic review followed the PRISMA twenty-seven-item checklist for transparent reporting of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions (Appendix 1)(Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt39). The search strategy and protocol were published in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (registration number: CRD42021235318). Guidance was sought from an information scientist to generate the search strategy. The following databases were searched in February 2021 and in May 2022 for qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods primary studies evaluating interventions for weight loss in adults with overweight or obesity and SMI: AMED, CINAHL, Medline complete, Embase and Web of Science. The search strategy included a combination of key words and terms related to ‘severe mental illness’ and ‘overweight’ or ‘obesity’ (Appendix 2).

Eligibility criteria

We included papers published in English reporting on participants 18 years and above, with overweight or obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2) and a diagnosis of SMI. SMI included conditions related to schizophrenia, psychosis and bipolar disorder. We included weight management interventions involving elements of physical activity, pharmacology, diet, food and nutrition, healthy lifestyle, psychology, education, information giving and/or support. Following discussions with mental health clinicians, it was concluded that surgical interventions were out of the scope of this review as such services are provided by tier 4 weight management services in the acute sector. Comparator groups (CG) were treatment as usual (TAU), no care or an alternative intervention (any other weight management intervention).

To assess effectiveness, the primary outcomes of interest were change in BMI and body weight with secondary outcomes including changes in waist circumference, or/and body composition, quality of life (QoL), perceived impact on mental health and attrition. Studies were included if they were RCT or quasi-RCT. To assess acceptability, qualitative studies included focus groups, interviews or surveys. Non-English language papers were excluded as we lacked the capacity for translation.

Selection process

In stage one sifting, a reviewer (HS) screened all titles, subject headings and abstracts for key words guided by population, intervention, and study design. Full-text articles were obtained for eligibility assessment, and the reviewer screened all full-text articles for inclusion using Rayyan QCRI. Six independent reviewers (ELG, GJM, LB, JS, AI and SF) double-sifted all papers at each stage, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. Results and consensus were recorded on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Data collection process

Data from the included studies were recorded on a pre-piloted data extraction sheet. One reviewer extracted data for all included papers (HS) and four independent reviewers (ELG, GJM, LB and AI) checked extracted data, with disagreements resolved through discussion. Items extracted included SMI diagnosis, age, sex, setting, intervention components, outcomes measures and drop-out rates.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal of the conduct and reporting of included studies was assessed using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists for study design(40). One reviewer (HS) assessed all papers and four independent second reviewers (AI, ELG, GJM and LB) checked the appraisals independently, with disagreements resolved through discussion.

Data synthesis

Mean differences (MD) and 95 % CI were calculated to compare differences in treatment effects between intervention and comparison for BMI (kg/m2) and weight (kg). Review Manager software (RevMan 5.3) was used to conduct meta-analyses where appropriate and results graphically displayed as forest plots(Reference Higgins, Li and Deeks41). Effect size was judged as 0·8 a large effect, 0·5 a moderate effect and 0·2 a small effect. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the χ 2 test (P = 0·1) and quantified using I2 statistic as per Cochrane Collaboration Guidelines(Reference Deeks, Higgins and Altman42). Sensitivity analysis was to be conducted by removing any study that had potential issues with bias(Reference Deeks, Higgins and Altman42). Where possible, subgroup analyses were to be performed to explore potential sources for heterogeneity(Reference Deeks, Higgins and Altman42) by category of intervention, setting or SMI diagnosis.

An inductive, thematic analysis approach was pre-specified for extracted qualitative data to identify codes and develop themes that potentially address the review questions(Reference Robson and McCartan43). The final master themes and quantitative results were to be synthesised in a mixed method approach.

Results

Study selection

Identification of studies and reasons for exclusion are illustrated in Fig. 1. Following searches of scientific databases in February 2021, 3408 studies were identified, after removal of duplicates, 2581 records were screened of which 233 full-text articles were reviewed to determine eligibility and sixteen included in the review. In May 2022, a further rerun identified 608 studies of which twenty-nine full-text articles were screened for eligibility and two included in the review. A record of excluded studies can be found as supplementary material with this article.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow chart.

Study characteristics

Following sifting, eighteen papers were included in the final review, which detailed the results of nineteen different interventions(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) (see Table 1 for study characteristics). Two studies included two intervention groups in addition to a CG(Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56), and Henderson et al. (Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51), compared two pharmacology interventions with no CG. Included studies were from Canada (n 2)(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Klam, McLay and Grabke53) , Italy (n 2)(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49) , Japan (n 1)(Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56), New Zealand (n 1)(Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47), Spain (n 1)(Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55), Taiwan ROC (n 2)(Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54,Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) , Turkey (n 1)(Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57), the UK(Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) and the USA (n 6)(Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50–Reference Katekaru, Minn and Pobutsky52,Reference Weber and Wyne58) . Studies were RCT (n 10)(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) and quasi-experimental studies (n 7)(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51–Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54) , and one was a nested qualitative study(Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60) of an included RCT(Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61). The total number of participants were n 1312 ranging from 17(Reference Weber and Wyne58) to 332(Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55) study participants. Baseline BMI values ranged from 28·55 kg/m2 which is classed the overweight category to 44·9 kg/m2 which is classed as the obese type 2 category(1). The weight of participants ranged from 75·5 kg to 117 kg.

Table 1. Table of characteristics and within-study results for all studies included in the systematic review

RCT, randomised controlled trial; IG, intervention group; CG, comparator group; Wt, weight; QoL, quality of life.

Of the primary outcomes which were the focus of this systematic review, BMI was included in seventeen studies(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44–Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Klam, McLay and Grabke53,Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54,Reference Weber and Wyne58,Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) and body weight in fourteen studies(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44–Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49–Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Klam, McLay and Grabke53,Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) . Of the secondary outcomes, four studies included measures of QoL(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55) , five of mental health outcomes(Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) , ten of waist circumference(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54–Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57,Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) and seven of other anthropometric measures(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) . Two studies included male-only participants(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45) , two studies included female-only participants(Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57) and one study did not report sex ratio(Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48). Of the total number of participants, 52 % (n 684) were female. The majority of studies reported on patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (n 11)(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50–Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) followed by bipolar disorder (n 2)(Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48) , borderline personality disorder (n 1)(Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49), and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (n 1)(Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55), and three studies included participants with a range of SMI(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) .

Four study settings were on hospital grounds or inpatients(Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57,Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) , eleven were community or outpatients(Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50–Reference Klam, McLay and Grabke53,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56,Reference Weber and Wyne58,Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) , and three studies did not report the settings(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49) . The length of interventions ranged from 6 weeks(Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51) to 5 years(Reference Katekaru, Minn and Pobutsky52). There were two qualitative studies(Reference Klam, McLay and Grabke53,Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60) ; one(Reference Klam, McLay and Grabke53) included a nested qualitative design but did not provide quotations; therefore, it was not possible to perform any qualitative analysis on this study.

Intervention components

Interventions were diverse and included psychological interventions, two of which were compared in the same study (n 3)(Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49,Reference Katekaru, Minn and Pobutsky52) information giving (n 1)(Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56), physical activity (n 2)(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45) , and pharmacology (two interventions within one study) and one which was an experimental study with a nested qualitative element (n 5)(Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) or multi-component interventions (n 9)(Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48,Reference Klam, McLay and Grabke53–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) (Table 1).

Psychology

Katekaru, Minn and Pobutsky(Reference Katekaru, Minn and Pobutsky52) trialled behavioural counselling during ad hoc check-up appointments. Participants were encouraged to attend local wellness classes that provided nutrition and exercise guidance. Galle et al. (Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49) implemented two interventions for bariatric surgery candidates, one focusing on interpersonal relationships and the other on behaviour change.

Information giving

The first of two interventions in the study by Sugawara et al. (Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56) included brief advice on body weight with weigh-in sessions delivered by psychiatrists.

Physical activity

Abdel-Baki et al. (Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44) assessed the feasibility of individual aerobic interval training, and Battaglia et al. (Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45) implemented soccer training sessions with an aim of improving the psychophysical condition of participants including QoL, body weight and physical performance.

Pharmacology

Henderson et al. (Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50) investigated the effect of sibutramine for weight loss and in a further study(Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51) compared the effect of ziprasidone as an adjunct treatment for olanzapine and for clozapine. Elmslie et al. (Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47) investigated carnitine supplementation, and Whicher et al. (Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) compared liraglutide as an adjuvant to promote weight loss compared with placebo.

Multi-component

Centorrino et al. (Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46) investigated a combination of behaviour, diet and exercise which included both aerobic and strength training. Kuo et al. (Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54) included a weight reduction intervention as part of a wider study and included behaviour therapy, exercise and dietary elements. Other multi-component interventions included structured behaviour change classes, healthy eating, physical activity and smoking cessation(Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48); group education, exercise and social community activities(Reference Klam, McLay and Grabke53); physical activity in local streets, nutrition and tailored weight reduction plans(Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57); education, physical activity and diet(Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55); and tailored dietary plans and physical activity(Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59). The second intervention in the study by Sugawara et al. (Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56) built on the first intervention by including a structured food and nutrition programme delivered by dietitians. Another study used behavioural strategies including barriers to change, problem-solving and goal setting with additional focus on diet and activity(Reference Weber and Wyne58).

Comparator characteristics

The majority of CG were TAU, but three of these provided no detail(Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56,Reference Weber and Wyne58,Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) . In other studies, TAU involved medical check-ups, psychological evaluation and meetings with a bariatric surgeon(Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49) and regular psychiatrist check-ups(Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55). In the soccer intervention, the CG were instructed not to perform any organised physical activity during the experimental period(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45). In three of the pharmacological interventions, the CG was administered a placebo capsule(Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) and in the fourth there was no CG(Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51). The CG in Frank et al. (Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48) was described as high-quality medical monitoring. In one study, the CG received the same treatment as the intervention group but did not have an SMI diagnosis(Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57).

Quality appraisal

A summary table of the CASP results is presented in Appendix 3.

Randomisation and blinding

Of the ten RCT, four did not report the method of randomisation(Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) and six did not report the method of allocation concealment(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) . Three RCT reported comprehensive blinding of participants, study investigators and outcome assessors(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) .

Results

In seven of the included studies, five studies performed an intention-to-treat analysis using Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF)(Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) . Of the studies that did not perform an intention-to-treat analysis, ten reported results in favour of the intervention(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48,Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49,Reference Katekaru, Minn and Pobutsky52–Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56,Reference Weber and Wyne58,Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) . Additionally, one of the studies had a high drop-out rate (29 %) and lost seven participants for reasons that pertained to the intervention(Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56).

Generalisability of the results

All studies addressed weight-related issues in adults with SMI and overweight or obesity as per our inclusion criteria. However, the intervention by Galle et al. (Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49) was tailored to bariatric patients, and Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) assessed obesity as BMI > 27 kg/m2 using Asian population standards, as such these two interventions may lack sufficient generalisability.

Data synthesis

BMI (kg/m2)

Of the ten RCT, three studies reported BMI change score(Reference Elmslie, Porter and Joyce47,Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59,Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) , three reported BMI follow-up score(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55) , and one reported both BMI follow-up and change score(Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57). Two studies reported BMI outcomes as percentages and as such were not included in statistical synthesis(Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48,Reference Weber and Wyne58) . Sugawara et al. (Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56) conducted a multi-arm study; as double counting of a CG is not recommended, the two interventions were combined (Doctor’s Weight Loss Advice group and Nutrition Education group) using a recommended formulae for combining summary statistics via Review Manager 5.3 calculator(Reference Higgins, Li and Deeks41). Additionally, Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) assessed obesity using a different standard to that of our inclusion criteria, as such this study was also excluded from pooled synthesis. In 2010, sibutramine, an appetite suppressant which had previously been used for the treatment of obesity, was suspended by the EU due to associated cardiovascular risks(62). The pharmacological study by Henderson(Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50) which trialled sibutramine was therefore excluded from analysis.

The pooled data for mean differences in BMI at follow-up for four studies(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55–Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57) (n 566) were calculated via meta-analysis using a fixed effects model as there was evidence of low statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 13 %, P = 0·33). The results showed no overall effect in favour of intervention or comparison (MD –0·42, 95 % CI –1·27, 0·44, P = 0·34) (Fig. 2). As only four studies were included, pre-specified subgroup analysis was not performed.

Fig. 2. Pooled results of BMI outcomes from four RCT for intervention v. comparator groups.

Only four of the of the quasi-experimental studies reported mean BMI (sd)(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51) , two of which compared two interventions(Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51) ; therefore, pooled analysis of outcomes was deemed inappropriate. Mean differences (95 % CI) were instead calculated using pre-post results(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51) . Only one study(Reference Gallé, Cirella and Salzano49) indicated a very large effect for both interventions at follow-up (interpersonal therapy group MD 14·20, 95 % CI, 12·19, 16·21; dialectical behavioural group MD 9·40, 95 % CI, 7·32, 11·48).

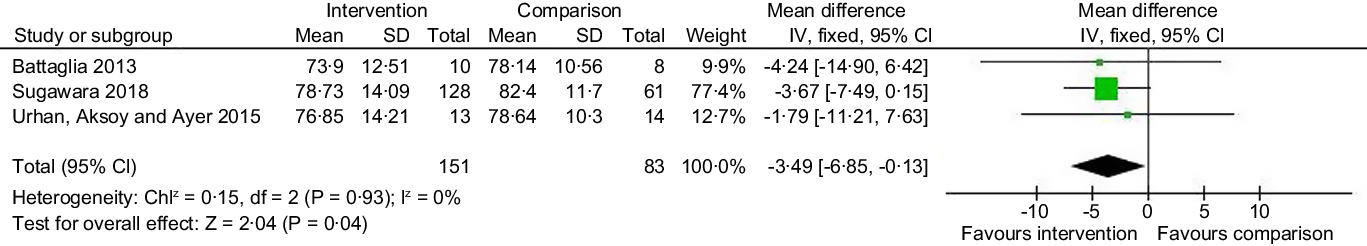

Body weight

The pooled data for mean differences in body weight (kg) at follow-up for three studies (n 234)(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57) were calculated via meta-analysis using a fixed effects model as there was evidence of low statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0 %, P = 0·93). The results indicated a small effect in favour of the intervention (SMD –3·49, 95 % CI –6·85, –0·13, P = 0·04), although the upper boundary of the CI of all three studies indicated some uncertainty in the effect size (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Pooled results of body weight outcomes from three RCT for intervention v. comparator groups.

Of the quasi-experimental studies, only three reported mean (sd) and one study reported two pharmacological interventions(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51) ; individual measures of effect were calculated but showed no pre-post effect for the interventions in terms of reductions in weight.

Due to insufficient data to conduct meta-analyses, secondary outcomes were assessed using the results reported by individual study authors.

Quality of life

For QoL, one study(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45) found in favour of the intervention for the SF-12 Mental Component Score and the SF-12 Physical Component Score at 12-week follow-up (P < 0·0001), while a further study author(Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55) reported in favour of the intervention for the SF-36 Standardized Physical Component Scale (Intervention 1·83, 95 % CI 0·70, 2·95 and CG 0·24, 95 % CI –0·74, 1·22) but in favour of the CG for the Standardized Physical Component Scale (Intervention –0·39, 95 %CI: –1·97, 1·19 and CG 2·19, 95 % CI 0·58, 3·81). While one study(Reference Centorrino, Wurtman and Baldessarini46) reported no significant differences in the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire from baseline to follow-up but omitted the results of the SF-36.

Impact on mental health

For mental health outcomes, three studies(Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55) reported no effect for either the intervention or CG. Similarly, one quasi-experimental study(Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51) also found no significant differences for any mental health outcome (The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms) for either intervention group (clozapine or olanzapine groups).

Body composition

There were contrasting results across measures of body composition. One study(Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57) reported that both the intervention and CG showed decreases in waist-to-hip ratio, while in contrast another study(Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50) found a significantly greater increase in waist-to-hip ratio in the intervention group (P = 0·07). A third study(Reference Weber and Wyne58) found no significant between groups differences in waist-to-hip ratio. While one quasi-experimental study(Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54) found a significant decrease in waist-to-hip ratio at follow-up (P < 0·05).

Two studies(Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57) reported significantly greater decreases in waist circumference in favour of the CG (P < 0·05), while in contrast a further study(Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50) reported significantly greater decreases in waist circumference in favour of the intervention (P < 0·005). A third study(Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55), found slight mean increases in the intervention group (0·98, 95 % CI, 0·01, 1·95).

There were also differences across the quasi-experimental studies where two studies(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44,Reference Kuo, Lee and Hsieh54) reported a significant decrease in waist circumference at follow-up (P < 0·01). In contrast, a further study(Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51) found no significant decreases in waist circumference at follow-up in either the clozapine or olanzapine groups but a clear increase within the olanzapine group.

Qualitative result

As only one qualitative study was included(Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61), overall thematic analysis was not possible. Within this individual study, semi-structured interviews explored expectations and experiences of taking part in the RCT, in addition to broader experiences of attempted weight loss. Within the study, thematic analysis reported by the authors showed that participants had pre-trial reservations about the liraglutide injections but reported no post-trial issues with this(Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60). Other reported themes related to: medication associated weight gain; an improvement in the QoL as a result of the study; study information and support from trial being well received by the participants and practical aspects of attending the clinic such as issues with travel(Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60).

Discussion

Summary of findings

The aim of this mixed methods systematic review was to assess the available evidence for the effectiveness of weight management interventions for people with SMI and overweight or obesity, effective elements of weight management interventions and to collate qualitative evidence of acceptability. Eighteen studies, representing nineteen diverse interventions were included in the systematic review, and four RCT were included in two meta-analyses(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55–Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57) . As the number of studies included in the meta-analyses was small, subgroup analysis could not be conducted, and therefore the research question regarding which elements of interventions are effective was not answered. It was also not possible to conduct a meta-analysis of included quasi-experimental studies due to methodological heterogeneity.

While one meta-analysis of three studies in this systematic review showed a small effect in favour of the interventions in terms of reduction in body weight, the other meta-analysis found no effect for BMI. Individual study authors reported mixed results for anthropometric and QoL outcomes and no improvement in mental health outcomes. Only one qualitative study(Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60) was included in the systematic review which was nested within an RCT(Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61); therefore, the question of acceptability could not be addressed.

Interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that weight management interventions for people with overweight or obesity and SMI had a small effect on decreases in body weight. However, this finding was based on only three studies(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57) . Furthermore, combined summary statistics were calculated for two interventions within one of the studies which was a multi-arm RCT(Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56), and this resulted in an imbalance between the number of participants in the intervention arm (n 128) v. the control arm (n 61). As such this finding should be treated with caution. However, this finding is also consistent with other systematic reviews on weight management interventions for people with SMI. For example, one systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on pharmacological interventions for antipsychotic weight gain also found in favour of the intervention for decreases in body weight (MD –3·12, 95 % CI, –4·03, –2·21); although in contrast to this systematic review a small effect for BMI outcomes was also found (MD –0·94, 95 % CI, –1·45, –0·43)(Reference Caemmerer, Correll and Maayan28), and this was based on sixteen studies as opposed to only three that were included in this meta-analysis. In another systematic review of weight management interventions for people with schizophrenia, cognitive behavioural therapy interventions were found to have a modest effect on weight reduction (WMD –1·69 kg CI –2·8, –0·6), and this was also based on only three studies(Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington37). It was highlighted that inconsistency in the reporting of results by individual study authors impacted the scope for analysis(Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington37). Inadequate reporting of results by study authors was also a barrier to more comprehensive analysis within this systematic review, for example, where outcomes were reported as percentages(Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48,Reference Weber and Wyne58) rather than mean (sd).

The three studies(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45,Reference Sugawara, Sagae and Yasui-Furukori56,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57) included in the meta-analysis of body weight outcomes for this systematic review included physical activity components. This observation may be based on only three studies but is potentially interesting particularly as evidence suggests that people with SMI partake in lower levels of physical activity than the general population which is due to a range of factors such as low mobility(Reference Wilton14,63) and physical health problems(Reference Bassilios, Judd and Pattison64). Of the nineteen interventions included in this systematic review, twelve included physical activity components(Reference Abdel-Baki, Brazzini-Poisson and Marois44–Reference Frank, Wallace and Hall48,Reference Katekaru, Minn and Pobutsky52–Reference Masa-Font, Fernández-San-Martín and Martín López55,Reference Urhan, Ergün and Aksoy57–Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) , but none described taking mobility or physical health challenges into consideration as a potential barrier to physical activity. For example, the soccer practice intervention(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45) involved moderate to vigorous activity(Reference Battaglia, Alesi and Inguglia45), and a further intervention included walking up and downstairs(Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59) potentially excluding people with SMI and mobility challenges. This perhaps highlights the importance of tailoring weight management interventions to SMI.

This systematic review identified only one eligible qualitative study and as such could not address intervention acceptability; a previous systematic review of interventions for people with bipolar disorder and obesity also reported a lack of qualitative evidence in this area(65). Qualitative evidence can add meaning to findings(Reference Brown, Buscemi and Milsom66). For example, Davidson(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras67) questioned patients with SMI about their experiences of an intervention to reduce readmission to hospital and found that the study had mistakenly focused on addressing the dysfunctions associated with SMI rather than the social difficulties following discharge that made hospitalisation seem the preferred option for some patients with SMI(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras67). Other qualitative research involving people with SMI has highlighted the wider socio-economic challenges of managing weight(68) including feelings of stigmatisation and isolation(Reference Wilton14,Reference Brown, Buscemi and Milsom66) , food insecurity and a lack of long-term support(Reference Teasdale, Samaras and Wade13), while for those in an inpatient setting loss of control and a sense of confinement(Reference Brown, Buscemi and Milsom66). The one qualitative study included in this systematic review highlighted the acceptability of text message reminders for appointments to receive liraglutide injections and concerns about the potential side effects of the medication(Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61). Text message reminders have been shown to increase aherence to treatment(Reference Menon, Selvakumar and Kattimani69) and reduce missed community mental health appointments by up to 28 %, which is important as this has a potential national cost-saving benefit of an estimated £150 million a year(Reference Sims, Sanghara and Hayes70).

Limitations of the evidence included in the review

The NICE recommends using waist circumference in addition to BMI for people with a BMI < 35 kg/m2(71), while the WHO recommends the use of waist circumference alone or in conjunction with BMI(72); waist circumference is an indicator of body fat accumulation around the abdominal area which is associated with obesity(Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington37,65) . Combined waist circumference measurements and BMI also provide estimated cut-off points for disease risk associated with overweight and obesity(72). However, only ten studies included in this systematic review reported both BMI and waist circumference. The secondary outcomes in this review did include other anthropometric measures of adiposity, but with mixed results as reported by study authors.

The Standard Evaluation Framework for weight management interventions(65) suggests that data relating to the success of weight management interventions is patchy and inconsistent, as has been seen within this systematic review; one reason being that inappropriate measures are often used(65). Complementary weight management-related outcomes could be included in studies, such as the proportion of participants who achieve 5 to 10 % reductions in body weight. Research has shown that weight loss of between 5 and 10 % reduces cardiovascular risk factors for the general population(Reference Brown, Buscemi and Milsom66) and has also been recommended by Public Health England as an outcome measure(65). Within this systematic review, one study included this as an outcome(Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61) reporting that at 3-month follow-up, n 8 (50 %) of the intervention group had experienced weight reductions of more than 5 % compared with only n 1 (5 %) of the control group; perhaps indicating this as a potential measure of short-term weight loss for studies of limited duration. Other additional outcomes potentially include assessing changes in intake of fruit and vegetables(65) as SMI is associated with lower dietary quality such as inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption and higher intakes of takeaways than the general population(Reference Teasdale, Ward and Samaras67).

A lower cut-off point than the standard threshold value (BMI 25 kg/m2) is recommended by NICE Guidelines for Black and Asian groups as these populations are at an increased risk of chronic health conditions at a lower BMI compared with White populations(68). Only one study included in this systematic review adjusted BMI thresholds using an Asian standard at a lower threshold(Reference Wu, Wang and Bai59). Only four studies reported ethnicity(Reference Henderson, Copeland and Daley50,Reference Henderson, Fan and Copeland51,Reference Weber and Wyne58,Reference Barnard-Kelly, Whicher and Price60) ; Henderson reported more than a quarter (27 %) of participants were of African American ethnicity but did not adjust BMI thresholds. Only one study included in the meta-analysis for BMI outcomes reported ethnicity, but this was reported as ‘other ethnic group’ (13 %) which lacked clarity(Reference Whicher, Price and Phiri61). Evidence shows that ethnic background can impact weight loss outcomes(Reference West, Prewitt and Bursac73,Reference Buffington and Marema74) , as such had there been adequate data, subgroup analysis by ethnic background may have been of benefit to determine whether ethnicity impacts weight-related outcomes for people with SMI. This is particularly important as evidence shows that people from Black and ethnic minority groups are overrepresented in psychiatric inpatient settings compared with other people with SMI(Reference Wilton14) and may have worse mental health outcomes(63,Reference Smith, Yamada and Barrio75) .

Limitations of the review processes used

Although a thorough search of databases was conducted, due to time constraints sources of grey literature did not form part of the search strategy for this systematic review. Grey literature refers to articles not published by a commercial reviewer such as those produced by governments and organisations(Reference Haddaway, Collins and Coughlin76,Reference Mahood, Van Eerd and Irvin77) . Inclusion of such material in a systematic review is considered good practice for minimising the risk of publication bias where publication of research findings is influenced by the direction of results(Reference Lefebvre, Glanville and Briscoe78) as evidence shows that studies reporting positive outcomes are more likely to be published which can cause overestimation of effect sizes in meta-analyses(Reference Haddaway, Collins and Coughlin76). However, there is also some criticism surrounding the search engines commonly used for grey literature searches such as Google Scholar and Web of Science. One study on the role of Google Scholar in the search for grey literature highlighted constraints in search string complexity(Reference Haddaway, Collins and Coughlin76) which could potentially limit search results. Additionally, some systematic reviewers restrict grey literature searches to the first one hundred records, an activity that has been described as not evidence based and disproportionate to the volume of records found via other databases(Reference Haddaway, Collins and Coughlin76). This is of particular concern as Google Page Rank, lists results according to popularity(Reference Mahood, Van Eerd and Irvin77). In addition to these drawbacks, despite guidance on where to find grey literature(Reference Mahood, Van Eerd and Irvin77) there is also a lack of standardised methodology(Reference Mahood, Van Eerd and Irvin77).

Best practice is for reviewers to independently extract data; however, this was not possible as the systematic review formed part of a wider 12-month project. However, to ensure reliability and accuracy of the screening process, four reviewers independently checked extracted data.

Implications for practice and policy

This systematic review was inconclusive as inadequate evidence was found to inform practice or policy on weight management for people with SMI and overweight or obesity as there is an absence of a rigorous evidence particularly in terms of the acceptability of interventions.

Future research

The results of this review have highlighted a severe lack of qualitative studies specifically looking at the experiences of adults with SMI participating in weight management interventions. Therefore, future experimental studies should focus on mixed methods approaches that incorporate a qualitative element such as interviews and focus groups to capture further insight into the barriers and facilitators to successful weight management. Participant feedback on weight management interventions has been advocated by Public Health England as an essential opportunity to identify the strengths and weaknesses of interventions(65).

It is recommended that studies include other measures of weight loss such as measures of central adiposity or 5 to 10 % weight loss as outcome measures in addition to weight and BMI. BMI can be limited as it does not account for fat and fat-free mass(Reference Rothman79) and has been shown to misclassify participants. A comparison between bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) and BMI as outcome measures in men with obesity and schizophrenia showed that BMI calculations misclassified men who had 30 % body fat as having a healthy weight rather than having obesity(Reference Sharpe, Byrne and Stedman80).

Finally, there was inadequate reporting within some of the studies included in this review. Consistency and completeness in the reporting of primary studies would give more scope for performing a meta-analysis. To ensure optimal reporting primary study, authors should follow standardised guidelines for the reporting of primary studies such as Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)(Reference Moher, Hopewell and Schulz81). This was also noted by another systematic reviewer of weight reduction interventions for people with schizophrenia(Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington37).

Conclusions

People living with SMI have higher rates of overweight and obesity than the general population. This mixed methods systematic review aimed to assess both quantitative and qualitative evidence on weight management interventions for adults living with SMI and overweight or obesity. There was a lack of qualitative evidence and a small effect for body weight reduction based on three studies but no effect on BMI. It is recommended that future primary studies integrate qualitative methodology into experimental study design to capture participants’ experiences of weight management and follow standardised guidelines to enable complete and transparent reporting. It is also recommended that additional outcome measures be used to complement weight and BMI outcomes such as measures of central adiposity and reductions in 5 to 10 % of body weight or changes in dietary quality.

Acknowledgements

Kerry Casey for assisting with writing the introduction. Fatemeh Eskandari for assisting with the rerun of study searches.

H. S. – conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualisation, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Re-run: data extraction, review, writing and editing. J. S.– conceptualisation, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, and writing – review and editing. Re-run: searches, review and editing. L. B. – conceptualisation, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, and writing – review and editing. A. I.– investigation, validation, review and editing. Re-run: searches, data extraction and editing. G. McG. – supervision, investigation, validation and writing. Re-run: data extraction, review and editing. S. F. – investigation, searches and data extraction. Re-run: data extraction and review. E. G. – conceptualisation, investigation, data curation, methodology, project administration, supervision, and writing – review and editing.

The authors of this review declare no conflict of interests. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix 1 PRISMA twenty-seven-item checklist for transparent reporting of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions.

Appendix 2 Search strategy.

Appendix 3 Summary of CASP results for included studies. RCT, randomised controlled trial.