Introduction

In the past decades, the study of Hellenistic poetry has witnessed a renaissance, fuelled especially by new papyrological discoveries, regular venues for discussion and exchange, and a broader disciplinary shift in Classics that has taken us further away from a narrow conception of the ‘canon’ and what is ‘worth’ studying.Footnote 1 This development has coincided, too, with renewed historical interest in the Hellenistic period and the use of a wider array of sources (particularly coinage and inscriptions) to broaden our perspective on the range of places and peoples that have interesting stories to tell from this era.Footnote 2 For all this awareness of a broad and brave new world, however, scholarship on Hellenistic poetry continues to be dominated by a single centre of Hellenistic literary production: Alexandria. In many respects, this is to be expected: papyri draw us particularly to the ambit of Ptolemaic Egypt; the majority of our complete, surviving Hellenistic works derive from the Ptolemaic court; and the Roman reception of Callimachus and his peers provides us with a ready-made narrative of literary history that has Alexandria at its heart.Footnote 3 The Ptolemaic capital was – undoubtedly – a major and influential centre for literary production in the Hellenistic world. But even so, we should not let this fact blind us to the synchronic and diachronic diversity of Hellenistic poetics: beyond third-century Alexandria, many other cities and kings patronised literary culture and the arts no less fervently than the Ptolemies, articulating their own distinctive conceptions of their cultural heritage and identity. For a richer perspective on the variegated texture of Hellenistic poetry, we should make every effort to look beyond the confines of Ptolemaic Alexandria and embrace our evidence for other literary cultures throughout the Hellenistic world, however fragmentary they may be.

In this spirit, I want to broaden our horizon in this paper to the literary dynamics of another Hellenistic kingdom – that of the Pergamene Attalids, whose efforts to fashion a new home of the Muses at Pergamon cast them as the fiercest cultural rivals to the Ptolemies.Footnote 4 The situation of our evidence at Pergamon, however, is almost the exact opposite of that in Alexandria. We are blessed with a rich archaeological record, but we have paltry literary remains, rendering the Attalids’ once active and flourishing literary climate almost fully obscured. In the past, scholars have turned to various sources in an attempt to reconstruct Pergamon's lost literary culture. Some have looked to the famous Great Altar's Gigantomachy and imagined baroque epics to parallel its grandeur;Footnote 5 others have explored potential hints of Attalid propaganda in Lycophron's Alexandra and Nicander's Theriaca;Footnote 6 while others, too, have mined later literary works, such as Philostratus’ Heroicus and Tzetzes’ Antehomerica, for potential reflections of putative Pergamene poems on Telephus.Footnote 7 All these approaches offer tantalising glimpses into the lost literary traditions of Attalid Pergamon, but they are all inevitably speculative and can only ever get us part of the way to a proper understanding of Pergamene poetry.

In this paper, by contrast, I seek to gain an insight into Attalid poetics by focusing on a rare fragment that explicitly praises the Attalid dynasty, Nicander's Hymn to Attalus (fr. 104 Gow–Schofield). In the past, this fragment has been studied primarily as a historical artefact, part of the larger puzzle of Nicander's chronology.Footnote 8 But I contend that it repays detailed literary analysis as an illuminating exemplar of Pergamene poetics. In this paper, I shall compare this fragment to surviving Ptolemaic praise poetry (especially Theocritus’ hymnic Encomium of Ptolemy Philadelphus, Id. 17), before exploring its sophisticated allusions to texts of the remote and more recent literary past. Given its fragmentary state, this poem can offer no more than another partial glimpse into Pergamon's lost literary culture, but in the following discussion we shall see how rich and valuable this glimpse nevertheless proves to be.

Royal Hymns, Ptolemaic and Pergamene

The first five lines of Nicander's Hymn to Attalus have been preserved through the Nicandrean biographical tradition (Vita Nicandri in schol. Ther., ii.1 Schneider):

Χρόνῳ δὲ ἐγένετο κατὰ Ἄτταλον τὸν τελευταῖον ἄρξαντα Περγάμου, ὃς κατελύθη ὑπὸ Ῥωμαίων, ᾧ προσφωνεῖ λέγων οὕτως·

In time, he lived under Attalus, the last ruler of Pergamon, who was deposed by the Romans and to whom he addresses the following words [Nicander fr. 104 Gow–Schofield]:

Descendant of Teuthras, O you who forever hold the heritage of your fathers, hear my hymn and do not thrust it away from your ear to be forgotten; for I have heard, Attalus, that your stock dates back to Heracles and wise Lysidice, whom Hippodame the wife of Pelops bore when he had won the lordship of the Apian land.

The precise addressee of this hymn has been hotly debated in the past century, identified as either Attalus I or Attalus III, the first and last kings of the dynasty respectively.Footnote 9 This uncertainty relates to a larger problem concerning the conflicting ancient testimony for Nicander's dating, a persistent headache of Nicandrean scholarship.Footnote 10 However, I am persuaded by those who accept the ascription of the Vita and situate the poet of this fragment under Attalus III in the second half of the second century BCE, identifying him with the composer of the Theriaca and Alexipharmaca – a position that best takes account of both internal and external evidence.Footnote 11 The poem thus offers unique insight into the poetic celebration of a late Attalid king and a rare opportunity to delve into the mechanics and poetics of Pergamene panegyric.

Theocritus’ Encomium of Ptolemy II is a natural comparandum for Nicander's fragment, as another hexameter hymn addressed to a royal mortal. It begins as follows (Id. 17.1–8):

From Zeus let us begin and with Zeus you should end, Muses, whenever we take thought of song, since he is best of the immortals; but of men let Ptolemy be named first and last and in the middle, since he is the most excellent of men. Heroes who were descended from demigods in the past found skilled poets to celebrate their fine deeds, but I who know how to speak fine words must hymn Ptolemy: hymns are the reward even of the immortals themselves.

Even at a glance, the similarities between these two poems are clear, especially in their generic self-consciousness and genealogical focus. The hymnic genre of both poems is explicitly flagged early on: through the word ὕμνον in verse 2 of Nicander's fragment, and the emphatic repetition of ὑμνήσαιμ᾽· ὕμνοι in Theocritus’ Encomium (Id. 17.8).Footnote 13 Of course, this term alone is not sufficient to describe either poem as a ‘hymn’ in our sense of the word (a song praising a god): in its earliest uses, ὕμνος denotes little more than ‘song’ in general (e.g. Od. 8.429; Hes. Op. 662), and although we can find a clearer distinction in Plato between hymnoi addressed to gods and encomia to mortals (ὕμνους θεοῖς καὶ ἐγκώμια τοῖς ἀγαθοῖς, Rep. 10.607a, cf. Leg. 3.700b), such a dichotomy was never watertight.Footnote 14 Despite this semantic ambiguity, however, Nicander's fragment contains various other formal features which reinforce its generic status as a hymn, parallel to those addressed to divinities: the second-person forms and imperatives (ἐρύξῃς, v. 2; σεο, v. 3); the injunction to listen (κέκλυθι, v. 2);Footnote 15 the particle ὦ (v. 1);Footnote 16 and the relative pronoun ἥν (v. 4), the usual hymnic device for segueing into mythological material.Footnote 17 Other elements may also play with hymnic tradition: the poet's wish for his poem not to become forgotten (μηδ’ ἄμνηστον, v. 2) inverts the hymnic speaker's usual claim to remember the god (e.g. μνήσομαι οὐδὲ λάθωμαι Ἀπόλλωνος ἑκάτοιο, Hymn. Hom. Ap. 1); the poem has itself become an object of memorialisation.Footnote 18

Despite this generic parallel, however, we can also identify a difference of focus between these hexameter hymns: from the very start of Theocritus’ poem, Ptolemy competes for attention with Zeus, king of the gods, who is mentioned first and serves as both a foil and parallel for the Alexandrian king; in comparison to the ruler of the gods, Ptolemy only comes out as ‘the most excellent of men’ (προφερέστατος ἀνδρῶν, Id. 17.4).Footnote 19 At the start of Nicander's poem, by contrast, Attalus is presented as the sole recipient and auditor of the hymn. We cannot know whether other divinities appeared later in the poem, but it is notable that the fragment begins with an unqualified celebration of Attalus as the recipient of divine praise.Footnote 20 Such directness may lend further support to the identification of the addressee with King Attalus III, the only Pergamene king we know of who actively presented himself as equal to the gods during his own lifetime.Footnote 21

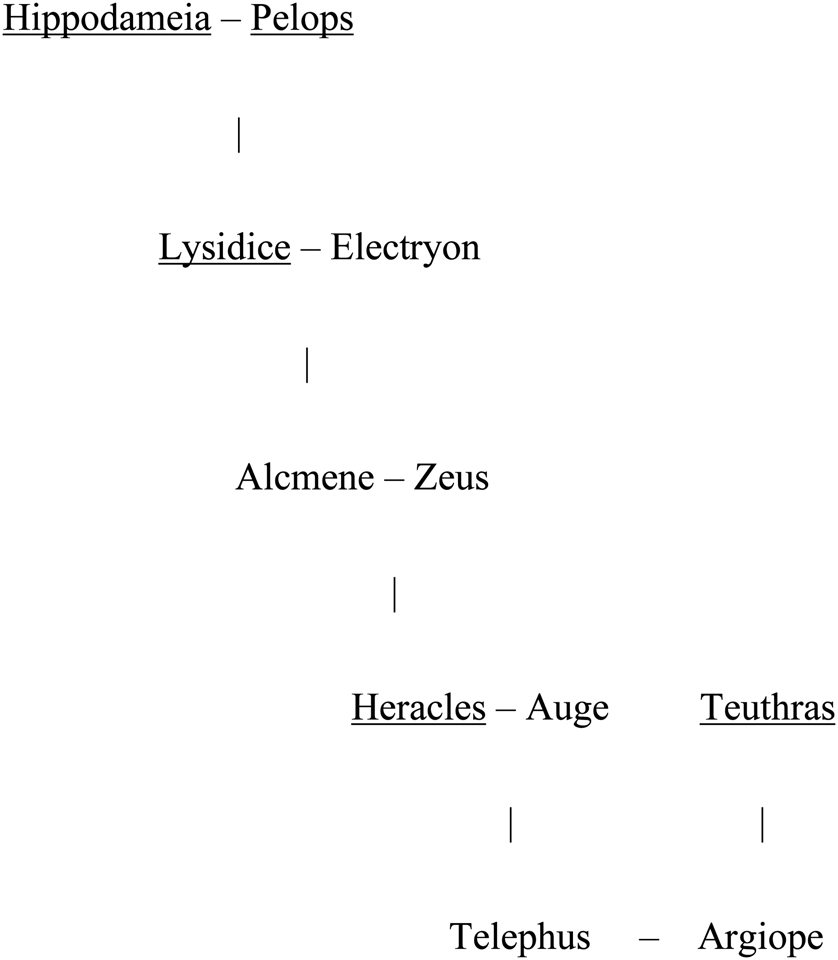

More interesting than this clear generic signposting, however, is our poem's emphasis on the royal laudandus’ ancestry, developing the initial mention of Attalus’ κλῆρον … πατρώιον (‘paternal heritage’, v. 1). In a mere five lines, Nicander emphasises the Attalids’ alleged descent from Teuthras, Heracles, Lysidice, Pelops and Hippodameia, an impressive string of mythological forebears. The common, though unnamed, link between all these individuals is Telephus, the keystone of the Attalids’ fabricated family tree, both as the successor to Teuthras, king of Mysia,Footnote 22 and as the son of Auge and Heracles (the great-grandson of Pelops and Hippodameia, and the grandson, in some traditions, of Lysidice: Hes. Cat. fr. 193.19–20 M–W; see Fig. 1). The Attalids’ celebration of their Telephean roots is well known: we need only compare the interior frieze of the Great Altar, whose linear narrative recounts the birth and maturation of Telephus, as well as the Attalids’ Teuthrania offering at Delos, a statue group of local Pergamene heroes and ancestors which certainly featured ‘Teutras’ (= Teuthras) and may have included Telephus as well.Footnote 23 It is thus unsurprising to find that this mythical ancestry also receives detailed attention in Nicander's poem.Footnote 24

Figure 1. Attalus’ mythical ancestry. Underlined names feature in Nicander's fragment.

Here too, however, the celebration of genealogical pretensions can be readily paralleled in Theocritus’ Encomium: near the start of his Idyll, Theocritus pictures the deified Ptolemy I Soter alongside his ‘relations’, Heracles and Alexander the Great, in the house of Zeus (Id. 17.13–33). And in Alexandrian poetry, more generally, we find a strong concern with familial continuity comparable to Nicander's insistence on Attalus’ protection of his paternal heritage (e.g. Callim. Hymn 4.170; Theoc. Id. 17.63–4; Eratosthenes fr. 35.13–16 Powell). Like these Alexandrian poets, Nicander emphasises the genealogical claims of his royal patrons. Admittedly, this parallel might not be particularly surprising in itself: genealogical boasts were a core element of praise from Homer and Pindar onwards, and became particularly important in a Hellenistic context, where all major dynasties placed a strong premium on the legitimising potential of mythical forebears, above all Heracles.Footnote 25 But even so, this general similarity affords us the opportunity to consider what is distinctive about Nicander's treatment of this genealogical topos.

Two differences between Nicander's and Theocritus’ hymn are particularly significant. First, Nicander's fragment places a greater emphasis on Attalus’ mythical female ancestry (Lysidice and Hippodameia), in contrast to Theocritus’ resolutely male focus (Soter, Heracles, Alexander, Zeus; only later at Id. 17.34 does Berenice enter the scene). This stronger female presence from the outset may well reflect a specific aspect of Pergamene ideology, its much-lauded virtue of familial harmony. The dynasty projected an image of harmonious unity throughout the royal family, not only between husband and wife, but also across generations between mother and son(s).Footnote 26 Particularly famous is the reverence shown by Eumenes II and Attalus II to their mother Apollonis, imitating the devotion of Cleobis and Biton (Polyb. 22.20) and dedicating a temple to her in her hometown of Cyzicus (AP 3), but we can equally cite the example of Attalus III himself, who was dubbed Philometor (‘mother-lover’) and was thought to have been particularly dedicated to his mother's memory.Footnote 27 Of course, Ptolemaic queens played their own significant role in Alexandrian propaganda as loving wives (Id. 17.38–44) and were even the subject of independent poetic praise elsewhere (e.g. Callimachus’ Victoria and Coma Berenices). But the Attalids’ emphasis on intergenerational harmony sets them apart from both the Ptolemies and their other rivals,Footnote 28 and our fragment certainly seems to respond to this self-image in its structure and language: the balanced interweaving of male and female names traces this harmonious symmetry all the way back to the Attalids’ mythical origins (Heracles – Lysidice – Pelops – Hippodameia – Apis), while the description of Lysidice as περίφρων (‘wise’) evokes the Odyssean Penelope, a prime model of marital ὁμοφροσύνη.Footnote 29 The greater attention which Nicander devotes to Attalus’ mythical female ancestors thus fits into a wider strategy of alluding to and exemplifying the Attalids’ unified kinship.

The second difference from Theocritus’ hymn lies in the fact that we can detect a more active geopolitical significance to the Attalid genealogy: in tracing the family back to Telephus and Pelops, Nicander retrojects the Attalids’ command of Mysia into mythical times. In archaic and classical literature, Telephus and Pelops both had a strong connection with the land of Mysia: in the Hesiodic Catalogue, Telephus is the ‘king of Mysia’ (Μυσῶν βασιλῆ̣[α], fr. 165.8 M–W), while at the opening of Euripides’ Telephus Pelops is said to be the one who first marked out the land's borders (ὦ γαῖα πατρίς, ἣν Πέλοψ ὁρίζεται, fr. 696.1 TrGF).Footnote 30 Both heroes thus authorise Attalid rule in the present, anchoring the dynasty's dominion in the distant past. Of course, the Theocritean Ptolemy's association with Heracles and Alexander has its own legitimising significance, but there we do not find the same geographical focus. Nicander's genealogical connection, by contrast, specifically authorises Attalid geopolitics through mythological precedent. Here, too, we might be able to locate this difference in the exigencies of the Attalids’ immediate context: originating as parvenu kings and breakaways from the Seleucid kingdom, they would have had even greater reason to legitimise their local rule.

Literary Learning and Allusive Exemplarity

Nicander's hymn thus reflects the Attalids’ cultural and political aspirations just as much as Alexandrian poetry echoes the pretensions of its rulers. Yet in addition to this, there is much of literary interest in this fragment, which on closer examination reveals a considerable degree of typically ‘Hellenistic’ learning. Such learning is most immediately visible in Nicander's selection of choice and rare vocabulary: Ἀπίδος in verse 5, for example, is a poetic and antiquarian name for the Peloponnese, derived from Apis, a mythical king of Argos.Footnote 31 The word and its cognates appear to have been a favourite among other Hellenistic poets.Footnote 32 By using it here, Nicander situates himself among the same erudite circles, while also nodding etymologically to the more familiar name (Peloponnese) through the adjective Πελοπηίς.Footnote 33 This word choice reflects more than just verbal games, however, for it also reinforces the Attalids’ cultural connection with old Greece, since the noun could point not only to the Peloponnese, but also to the ‘Apian plain’ in Pergamene territory.Footnote 34 Again, Pelops proves a pliant tool of Attalid geopolitics, forming the bridge between mainland Greece and Asia Minor. Literary learning coincides with political point.

A similar degree of erudition can also be found in Nicander's application of the phrase ἀπ’ οὔατος (v. 2). On the face of it, this might seem a rather innocuous expression, but it is in fact an extremely rare idiom: a Homeric dis legomenon, used by speakers wishing for something to be ‘far from their ears’ (Il. 18.272, 22.454). Given its rarity, this phrase was imbued with much intertextual potential, especially since it appears barely anywhere else in the Greek literary tradition.Footnote 35 By Nicander's day, however, it was also the subject of Hellenistic scholarly debate: the Homeric scholia reveal that some ancient scholars interpreted it not as a prepositional phrase (ἀπ’ οὔατος), but rather as a single word (ἀπούατος), glossed as κακός (‘bad’, presumably ‘bringing bad news’).Footnote 36 This zētēma evidently dates back at least to the third century, since Callimachus himself alluded to it in the Hecale, where he used the compound form, perhaps expressing implicit support for that interpretation of the crux (ἀπούατος ἄγγελος ἔλθοι, ‘an unwelcome messenger might come’, fr. 122).Footnote 37 Nicander, by contrast, deploys the word in its divided form, favouring a very different solution. Rather than endorse the bizarre adjectival form like Callimachus, he flattens out the oddity, naturalising it even further by adding a verb of motion (‘thrust away from the ears’). By employing the rare phrase in this way, the Pergamene poet alludes to and engages in contemporary scholarly debate like many of his Alexandrian predecessors; but he takes a strikingly different approach to Callimachus, suppressing rather than revelling in the grammatical peculiarity – perhaps a reflection of broader methodological differences between the two.Footnote 38

It is the very first word of the poem (Τευθρανίδης), however, which is packed with the most allusive and scholarly significance. Ostensibly, the word refers to the Attalids’ ancestor Teuthras, Telephus’ predecessor as king of Mysia. Yet this extremely rare patronymic occurs only once elsewhere in the extant literary tradition as a hapax legomenon in Homer's Iliad, where it refers not to Telephus, but to the otherwise unknown Trojan ally Axylus from Arisbe (Τευθρανίδην, Il. 6.13). We cannot rule out the possibility that the patronymic once featured in now-lost Cyclic treatments of Telephus, especially the Cypria, but it is significant that all our earliest poetic references to Telephus employ a completely different patronymic, Arcasides. They emphasise not Telephus’ descent from Teuthras, but rather his Arcadian roots as a descendant of Arcas (Τήλεφος Ἀ̣ρκα̣[σίδης], Archilochus fr. 17a.5 Swift; Τήλεφον Ἀρκασίδην, Hes. Cat. fr. 165.8 M–W).Footnote 39 Nicander's alternative patronymic thus diverges pointedly from earlier literary tradition in foregrounding the Attalids’ Mysian heritage. The Pergamene poet repurposes the Homeric patronymic for its expected and more illustrious genealogy, precisely how Homer should have used it: the Attalids are descended not from the otherwise unknown Arisbean of Iliad 6, but from the more famous Teuthras, eponymous king of Mysian Teuthrania.Footnote 40

In addition, however, this verbal echo encourages an implicit association of Attalus with the Homeric Axylus, an archetype of guest-friendship. As Axylus is slain by Diomedes at the start of Iliad 6, he is granted one of Homer's most moving and pathetic obituaries (Il. 6.12–17):Footnote 41

And Diomedes, good at the war-cry, slew Axylus, the son of Teuthras, who lived in well-built Arisbe, a man rich in livelihood and hospitable to men: for he lived in a home by the road and used to give hospitality to all. But not one of his former guests then faced Diomedes before him and protected him from woeful destruction.

This poignant description of a once welcoming host's fate resonates meaningfully against key themes of Hellenistic royal ideology – a point to which we shall turn shortly. But first it is worth noting that this passage clearly appealed to Hellenistic sensibilities, since it is also echoed in Callimachus’ Hecale, in a now fragmentary obituary for the poem's eponymous protagonist (fr. 80):

Go, gentle among women, along the road which heartrending pains do not pass. Often, good mother, we shall remember your hospitable hut, for it was a common shelter to all.

In concise and quasi-epigrammatic language, both Homer and Callimachus memorialise the deaths of generous hosts who, while alive, had extended their hospitality to one and all: note especially the repetition of πάντας (Il. 6.15) in Callimachus’ ἅπασιν (fr. 80.5), as well as both passages’ emphasis on continuous friendship through the iterative verbs and the repeated φιλ- root (φίλος, φιλέεσκεν, Il. 6.14, 15 ~ φιλοξείνοιο, ἔσκεν, fr. 80.4, 5). Yet, despite their kindness and generosity, neither figure could escape death. Callimachus conveys this inevitability through refined variatio, as the road upon which Axylus’ house once stood (ὁδῷ, Il. 6.15) is transformed into Hecale's euphemistic road to death (τὴν ὁδόν, fr. 80.2). By evoking Axylus’ death amid the din of the Trojan battlefield, Callimachus injects an additional level of pathos into Hecale's fate. Although her death was the natural and peaceful culmination of a long life, her many years were no less painful and difficult than those of the Trojan ally.

In a similar manner, I would argue that Nicander echoes this Iliadic passage, but not so much for pathos as for panegyric. Through the hapax legomenon Τευθρανίδης (which notably occurs in the same hexametric sedes),Footnote 42 the poet implicitly equates Attalus with a Homeric archetype of guest-friendship: as a prosperous and hospitable host, Axylus exhibits paradigmatic traits of Hellenistic kingship. The allusive implication is that Attalus too, as another ‘descendant of Teuthras’, is equally wealthy and just as capable of displaying a similar level of generosity. Indeed, such an image parallels Attalus III's own public self-image: in a famous decree found near Elaea, for example, he is characterised as ‘being well-disposed to and a benefactor of the people’ (εὔνουν [ὄντα] καὶ εὐ̣ε̣ρ̣γέτην τοῦ δήμου, IvP i.246.53), striving ‘always to be the cause of some good for the people’ ([ἀ]εί τινος ἀ̣γα[θ]οῦ παραίτι̣ον γίνεσθαι αὐτὸν δ̣[ι]ὰ τὸν δ̣ῆ̣μον, IvP i.246.54–5).Footnote 43 Here too, however, we should note that this allusive praise is similar to, but far more subtle than, that offered to Ptolemy by Theocritus in his Idylls. In Idyll 14, the king is directly praised for being generous to many and never refusing a request, ‘just as a king should’ (οἷα χρὴ βασιλῆ', Id. 14.63–4, cf. οἷ’ ἀγαθῷ βασιλῆι, Id. 17.105), while in Idyll 17 Theocritus celebrates Ptolemy's concern for not piling his great wealth up uselessly in his palace like a worker ant, but bestowing it on his companions and cities, as well as the gods and other kings (Id. 17.106–11).Footnote 44 Euergetism and beneficence were an important part of the royal image, and Nicander here, just like Theocritus, highlights his ruler's adherence to the expected pattern of royal behaviour. In a single word, Nicander combines scholarly erudition, Homeric allusion and courtly praise. Despite its fragmentary state, it would seem that this poem employs very similar encomiastic strategies to those of its Alexandrian predecessors.

Interdynastic Poetics

Even within the few lines that survive, therefore, we can detect Nicander's sophisticated and detailed engagement with his Homeric heritage. I would like to close, however, by exploring how the Pergamene poet positions his hymn more directly against the literary and ideological precedent of Ptolemaic Alexandria. We have already noted some key differences between Nicander's hymn and Ptolemaic comparanda (especially the undiluted emphasis on Attalus’ divinity, the stronger focus on mythical female ancestors and the geopolitical concentration on Mysia) – differences which reflect the distinctive cultural and political priorities of the Attalid kingdom. But we can also identify further divergences which seem to carry a more polemical edge, as Nicander constructs an image of Pergamene kingship in opposition to the ideology and literature of Ptolemaic Alexandria, especially as articulated by one of its most prominent poets, Callimachus.

One such difference revolves around the Attalids’ Telephean ancestry and descent from Heracles (Ἡρακλῆος, v. 3). By emphasising this genealogical line, Nicander departs from that favoured by the Ptolemies and their poets, who instead claimed descent from Heracles’ son Hyllus.Footnote 45 Callimachus, in particular, reflects this tradition in the Theiodamas episode of the Aetia, when he focuses on the boy's ravenous hunger (πείνῃ, fr. 24.1; [κακὴν β]ούπειναν, fr. 24.11) which is only cured by Heracles’ confiscation of Theiodamas’ ox; as Annette Harder has attractively suggested, this story ‘shows how Heracles saved the dynasty from which the Ptolemies were to descend by preventing Hyllus’ death from starvation’.Footnote 46 In the face of such a Ptolemaic genealogy, the Attalids’ Telephean roots prove an alternative and rival path to gain legitimacy. By celebrating them at the outset of his hymn, Nicander establishes the Attalids’ family tree as a worthy match for that of the Ptolemies.Footnote 47

From such an interdynastic perspective, we might also be able to draw further significance from Nicander's reference to the Apian land in the final line of our fragment (Ἀπίδος, v. 5). We have already noted the connection which this phrase draws between Peloponnesian and Pergamene territories. But we can also draw a contrast with Ptolemaic attempts to co-opt the authority of the Apian Peloponnese, especially through association with the Apis bull, a key element in Ptolemaic ideology. At the outset of the Victoria Berenices, Callimachus famously alludes to the pharaonic ritual of mourning the bull of Memphis (fr. 54.13–16) and appears to hint at its Argive pedigree by associating the Egyptian Apis with ‘cow-born Danaus’ (Δαναοῦ … βουγενέος, fr. 54.4). Within the poem's broader intercultural strategy of blurring Greek and Egyptian traditions, scholars have suspected an attempt here to align the Apis bull with its Peloponnesian namesake, Apis king of Argos (who was elsewhere associated with the foundation of Memphis: Aristippus FGrH = BNJ 317 F 1).Footnote 48 Faced with such a Ptolemaic tradition of co-opting the Argive king, Nicander's opening genealogy gains considerably more point. By tracing the Attalids’ heritage all the way back to Pelops and the Apian land, Nicander articulates an alternative ancestry which competes with Callimachus’ own: he emphasises Apis’ connection with Attalid Pergamon, rather than the pharaonic traditions of Ptolemaic Egypt.

At several points in these opening verses, therefore, Nicander articulates a vision of Pergamene kingship which differs significantly from the ideology of Ptolemaic Alexandria. The Callimachean passages cited above do not necessarily constitute direct intertexts for Nicander, but rather offer evidence for the competing traditions against which the Pergamene poet positioned his own poem and king. At other points in this fragment, however, we can identify a more direct engagement with Callimachus’ poetic output.Footnote 49 The epithet Πελοπηίς in verse 4, for example, used there to describe ‘Pelopean’ Hippodameia, occurs only once previously in extant poetry, in Callimachus’ Hymn to Delos (Hymn 4.70–2):

Arcadia fled, and Auge's holy hill Parthenium fled, and behind them aged Pheneius fled, and the whole land of Pelops that lies beside the Isthmus fled.

Such a precise parallel is unlikely to be accidental, especially since the Callimachean use of the word follows closely upon the mention of Auge, Telephus’ mother (Αὔγης, Hymn 4.70): her hill, where Telephus was born (cf. Eur. Telephus fr. 696.5–7 TrGF), joins the land of Pelops in fleeing from Leto's approach. The context of the Callimachean lexeme thus resonates against the larger concerns of Nicander's opening, again foregrounding the theme of the Attalids’ genealogy, while also hinting at the unmentioned common denominator: Telephus. Nicander appropriates a choice word from his literary predecessor to reinforce his own panegyric purposes. From this word alone, however, we cannot gain a clear sense of how Nicander situated himself against this Callimachean precedent. If anything, it only shows that already in the second century, Callimachus was being treated much as he had once treated Homer: as a sourcebook of lexical rarities. In knowingly nodding to this Callimachean hapax, Nicander acknowledges Callimachus’ status as a new classic.Footnote 50

However, we may be able to identify a further allusion earlier in the fragment which exhibits a more eristic relationship with Callimachus. The key to this interpretation is Nicander's request that Attalus ‘not thrust this hymn away from your ear to be forgotten’ (μηδ’ ἄμνηστον ἀπ’ οὔατος ὕμνον ἐρύξῃς, v. 2). We have already noted above how Callimachus and Nicander employed the Homeric rarity ἀπ’ οὔατος in fundamentally divergent ways. But the appearance of the phrase here in the context of divine hearing also invites a broader comparison between the two poets’ depictions of the divine reception of poetry. Ears are a recurring motif in Callimachus’ poetry, reflecting his larger concern with the sources of specific information and the transmission of news.Footnote 51 In particular, he displays a regular interest in communication with the divine by means of their ears.Footnote 52 Amid this wider Callimachean motif, however, one particular passage stands out for its formal and thematic similarities to Nicander's phrase: the programmatic conclusion of Callimachus’ Hymn to Apollo, when Envy secretly speaks into Apollo's ears (Callim. Hymn 2.105–6):Footnote 53

Envy spoke secretly into the ears of Apollo: ‘I do not admire the poet who does not even sing as much as the sea.’

Like Nicander's ἀπ’ οὔατος, Callimachus’ ἐπ’ οὔατα is another Homeric rarity: a hapax legomenon used in Odyssey 12 when Odysseus anoints his men's ears with wax to block the song of the Sirens (Od. 12.177). But it is an even rarer expression, appearing nowhere else in the extant literary tradition. It is a distinctive and memorable phrase, embedded in a famous Callimachean ‘purple patch’, and thus ripe for imitation by later poets. In addition, it is metrically identical to Nicander's ἀπ’ οὔατος, occurs in the very same metrical sedes (in a poem of the very same genre: hexametric hymn), and exhibits a similar thematic concern: at issue in both Callimachus’ epilogue and Nicander's fragment is the divine reception of a specific kind of song (in the latter, Nicander's hymn itself; in the former, poetry which fails to match the expanse of the sea). Of course, a sceptical reader could contend that both phrases are simply independent applications of an established Homeric verse pattern.Footnote 54 But given the contextual similarities, I believe we can see Nicander here evoking and adapting a famous Callimachean passage which is equally concerned with the proper appreciation of poetry, swapping one Homeric rarity for another. With an intertextual precision comparable to his reuse of Πελοπηίς, Nicander engages in a common Hellenistic reversal of beginnings and endings, echoing the close of the Callimachean hymn at the outset of his own.Footnote 55

Such reversal, moreover, extends to Nicander's revision of the Callimachean intertext.Footnote 56 In the Hymn to Apollo, invidious Φθόνος speaks into the ear of the divine Apollo, claiming that he rejects the poet who fails to sing as much as the sea (just as Odysseus rejects the song of the Sirens); yet Nicander speaks into the ear of the quasi-divine Attalus and bids him embrace, not reject, this poetic hymn. The poet thus distances Attalus from the Callimachean Φθόνος (and Odysseus’ deafened companions) and aligns him instead with the poetic sensibilities of Apollo, the Callimachean patron of poetry. Attalus becomes an idealised recipient of praise, as sophisticated and attuned as Apollo himself.Footnote 57 Moreover, Nicander's injunction for his royal addressee to listen (κέκλυθι, v. 2) directly parallels the poet's own behaviour in the very next line: he has heard of Attalus’ renowned genealogy (ἐπέκλυον, v. 3) – a word that gestures to tradition in the manner of an ‘Alexandrian footnote’.Footnote 58 Here, however, we should focus on the significance of this lexical parallel, which suggests the complementarity of poet and divine ruler as open and receptive auditors. In contrast to the riotous disagreements of Callimachus’ epilogue, Nicander articulates a harmonious acoustic reciprocity shared by poet and divine/royal patron. Through this verbal and thematic echo, Nicander polemically repurposes Callimachus, the literary ‘poster boy’ of a rival kingdom, to establish Attalus as a worthy cultural and political rival to the Ptolemies.

Callimachus’ hymn would have been a natural target for Nicander, providing an opportunity for him to position himself and his patron against a rival kingdom within the very same genre. But there may also be a larger political significance to his specific choice of the Apolline epilogue. In recent years, this conclusion of the Hymn to Apollo has been read as a veiled slight against the Seleucids, the contemporary rulers of the debris-filled Assyrian river. The closing verses not only assert Callimachus’ poetic preferences, but also involve a subtle dig against the Ptolemies’ eastern rivals.Footnote 59 Given this background, Nicander's allusion to this specific passage of Callimachus’ corpus gains further point: Nicander could have picked up on Callimachus’ interdynastic polemic and turned it back against him. The Ptolemaic Apollo may have surpassed the Seleucid-loving Φθόνος, but – on Nicander's reading – Attalus himself is a fair match for the Callimachean Apollo. From this evidence, it would seem that the interdynastic polemics of Hellenistic poetry ran in multiple directions and spanned multiple different kingdoms.Footnote 60

Conclusion

Despite its fragmentary state, therefore, this poem illuminates the larger agonistic and international context of Hellenistic poetry and expands our gaze beyond the single centre of Ptolemaic Alexandria. Even from its few surviving lines, we can gain a strong flavour of this Pergamene composition. In many ways, it is comparable to more familiar Alexandrian poetry – in its generic self-consciousness; in its celebration of a ruler as quasi-divine; and in its allusive use of obscure words and Homeric hapax or dis legomena. But in addition, the hymn agonistically positions itself against the literary output of a rival kingdom, epitomised by Callimachus’ own encomiastic poetry. It sets itself against the programmatic conclusion of Callimachus’ Hymn to Apollo, while also carving out the Attalids’ own claims to Heraclean and Peloponnesian ancestry.

The range of literary details and allusions that we have explored above demonstrate the depth and sophistication of Nicander's panegyrical project. We can only speculate how the hymn might have continued, and how this might have impacted the larger literary and political strategies that we have been tracing. Perhaps Nicander went on to make explicit mention of Telephus, the unnamed figure whose shadow hangs over the whole opening; or after the relative pronoun in verse 4, he might have continued with a fuller narrative of Pelops’ successful wooing of Hippodameia through a chariot race – an episode which would have resonated with the Attalids’ own reputation for equestrian success and prompted allusion to another famous opening in the literary tradition (the first poem in the collection of Pindar's Olympians: Ol. 1.67–96).Footnote 61 What we can conclude with certainty, however, is that this fragment allows us a rare glimpse into the post-Callimachean, international and agonistic world of Hellenistic poetics. Over the course of this analysis, we have seen how Nicander adopted two divergent methods to cope with the burden and precedent of Alexandria. On the one hand, he replicated the encomiastic strategies of his Alexandrian predecessors. But simultaneously, he repurposed Callimachean precedent to articulate a distinctive and unique view of his ruler, who even proves to be a peer of Apollo, the divine patron of Ptolemaic Egypt – a typically Hellenistic combination of tradition and innovation.