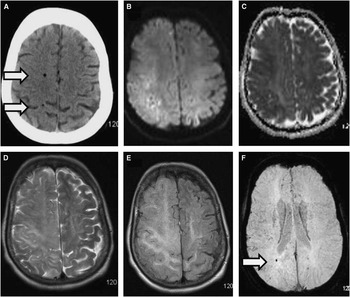

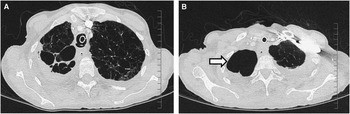

This is the case of a 69-year-old woman with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who rapidly lost consciousness during an air flight, necessitating emergency landing shortly after takeoff. Noncontrast computed tomography of the brain showed two locules of air (Figure 1A) in the right frontal and parietal lobes. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed scattered foci of diffusion restriction (Figure 1B,C), ill-defined vasogenic edema (Figure 1D,E), and microhemorrhages (Figure 1F) in the right frontal and parietal lobes. The findings were consistent with cerebral air embolism and resultant right middle cerebral artery territory infarction. Computed tomography of the thorax (Figure 2) showed a large right apical bulla and extensive emphysematous changes. The patient was treated with full supportive measures in an intensive care setting. The patient eventually made a good clinical and neurological recovery.

Figure 1 Axial noncontrast computed topography (CT) of the brain (A) showed intraparenchymal air in the right frontal and parietal lobes (arrows). Axial magnetic resonance (MR) diffusion (B) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map (C) sequences showed foci of diffusion restriction in the right frontoparietal white matter. T2 (D) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (E) sequences showed vasogenic edema. A susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) sequence (F) showed right parietal microhemorrhages (arrow).

Figure 2 Axial computed topography (CT) of the thorax lung windows (A, B) show diffuse emphysematous changes including a large right apical bulla (arrow).

Only a small number of similar cases have been reported in literature.Reference Gudmundsdottir, Geirsson, Hannesson and Gudbjartsson 1 Cerebral air emboli are very rare but can occur secondary to central venous catheter insertion, cardiothoracic surgery, chest trauma, deep sea diving, or rupture of a lung bulla or cyst.Reference Sviri, Woods and van Heerden 2 In this case, the mechanism was likely related to external decompression during air flight ascent. Boyle’s law states that gas volume is inversely proportional to the pressure exerted upon it.Reference Yeung, Ma, Mak and Lam 3 Cabin pressure dropping by up to 200 mmHg routinely between ground level and cruising altitude can lead to a 33% expansion in the volume of pulmonary bullae or cysts.Reference Zaugg, Kaplan, Widmer, Baumann and Russi 4 This can result in microscopic tears or rupture of the lining of the bullae. Air locules or bubbles can then track into the adjacent small blood vessels and into the systemic circulation. The brachiocephalic trunk is the most proximal of the great vessels of the aorta and is preferentially affected. Air bubbles can then flow through to the right middle cerebral artery, leading to occlusion of smaller vessels and resultant infarction. However, neurological deficits with cerebral air emboli may be reversible. Providing 100% oxygen may reduce the size of the air locules by depleting nitrogen and restore blood flow to an occluded artery. Hyperbaric therapy compresses the bubbles and steroids reduce cerebral edema. However, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and large bullae, such treatments carry the risk of further bulla rupture.Reference Yeung, Ma, Mak and Lam 3 , Reference Edwardson, Wurth, Lacy, Fink and Becker 5

The vast majority of cases of cerebral air embolism in the medical literature prove fatal; thus, early recognition and diagnosis with the radiographic techniques described here is essential.

Disclosures

None of the authors has anything to disclose.

Statement of Authorship

DB researched, drafted, and developed the manuscript. PB helped evaluate and edit the manuscript. JO’R acquired manuscript data. SL supervised and helped in manuscript development, editing, and evaluation.