Introduction

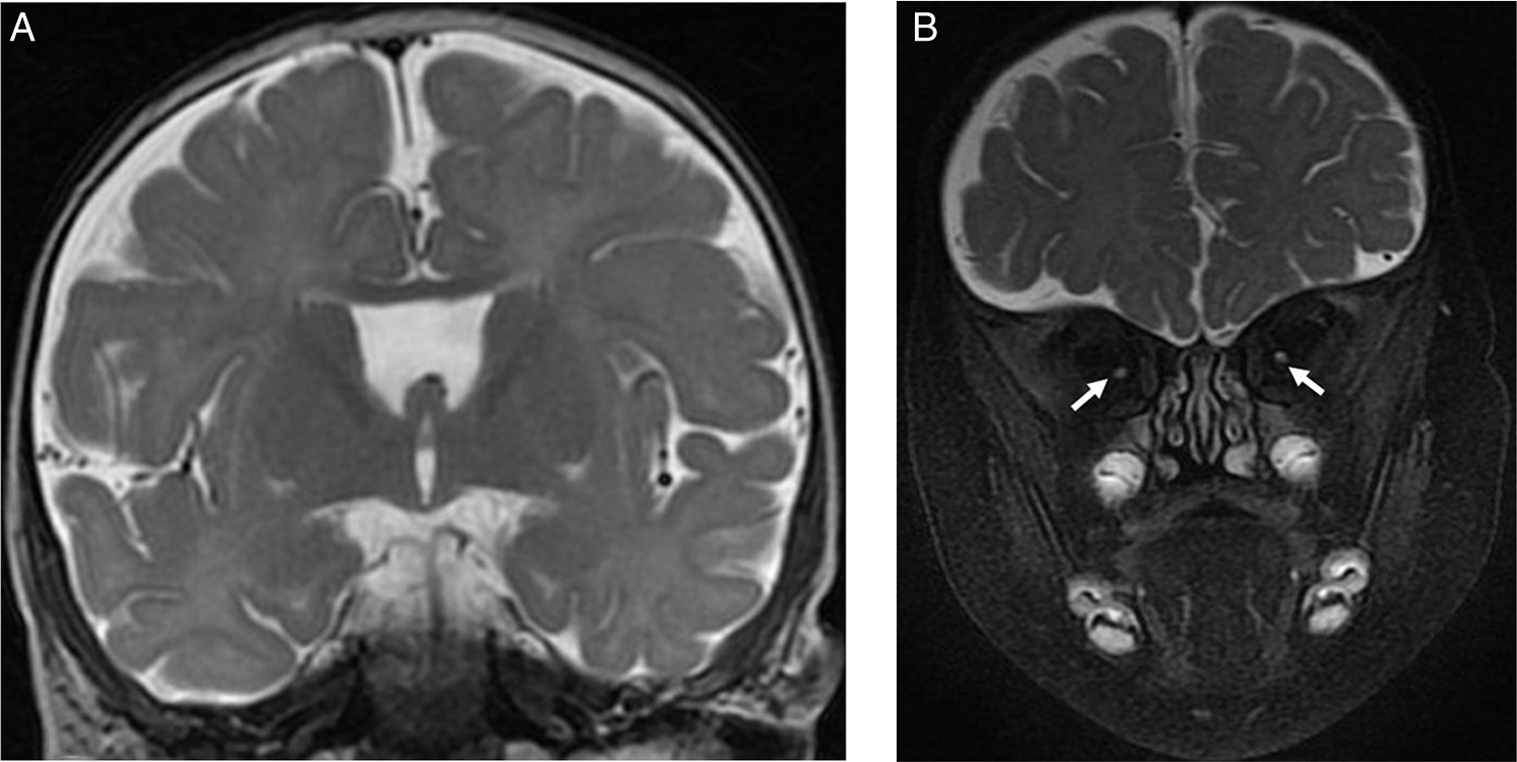

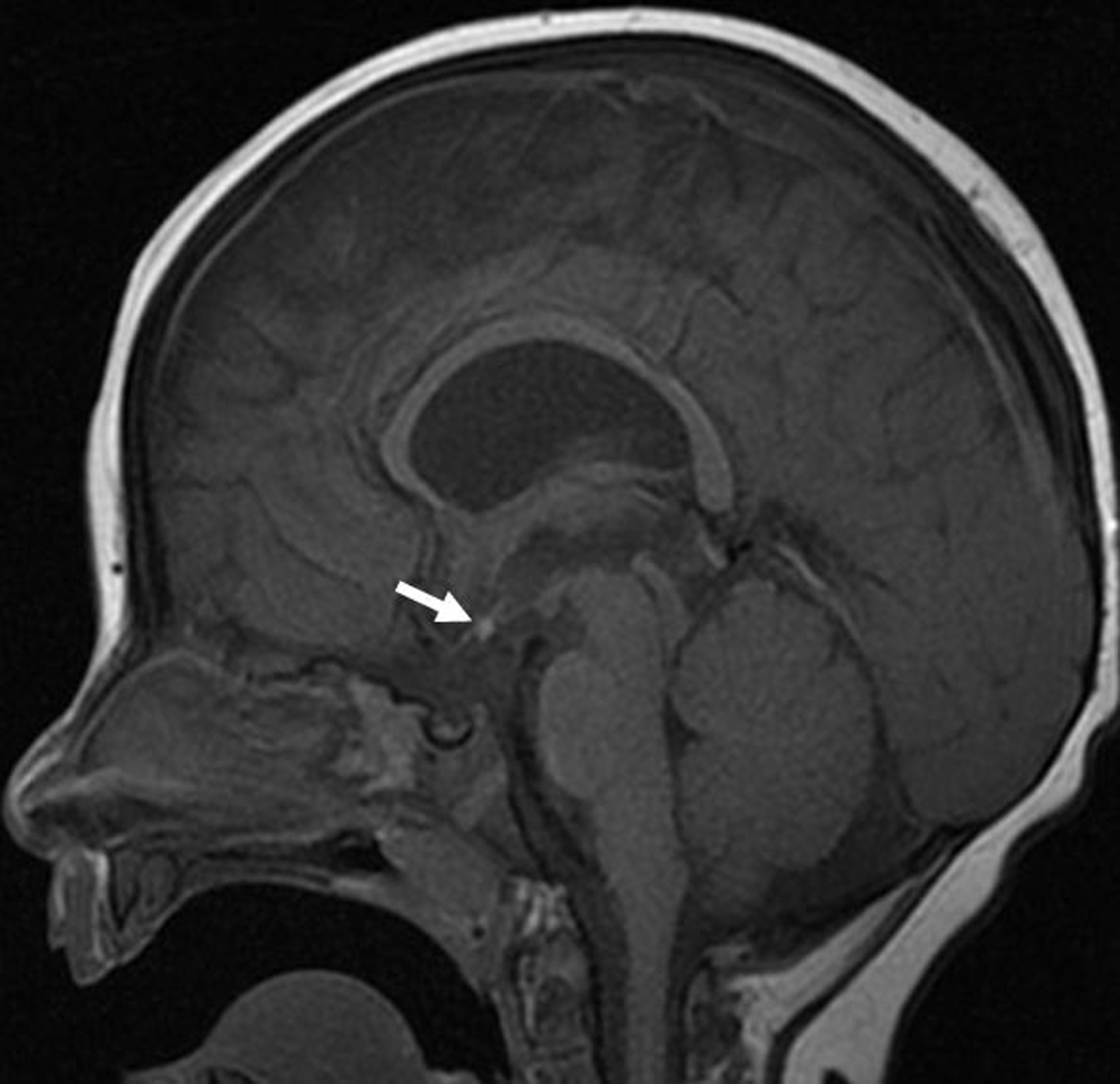

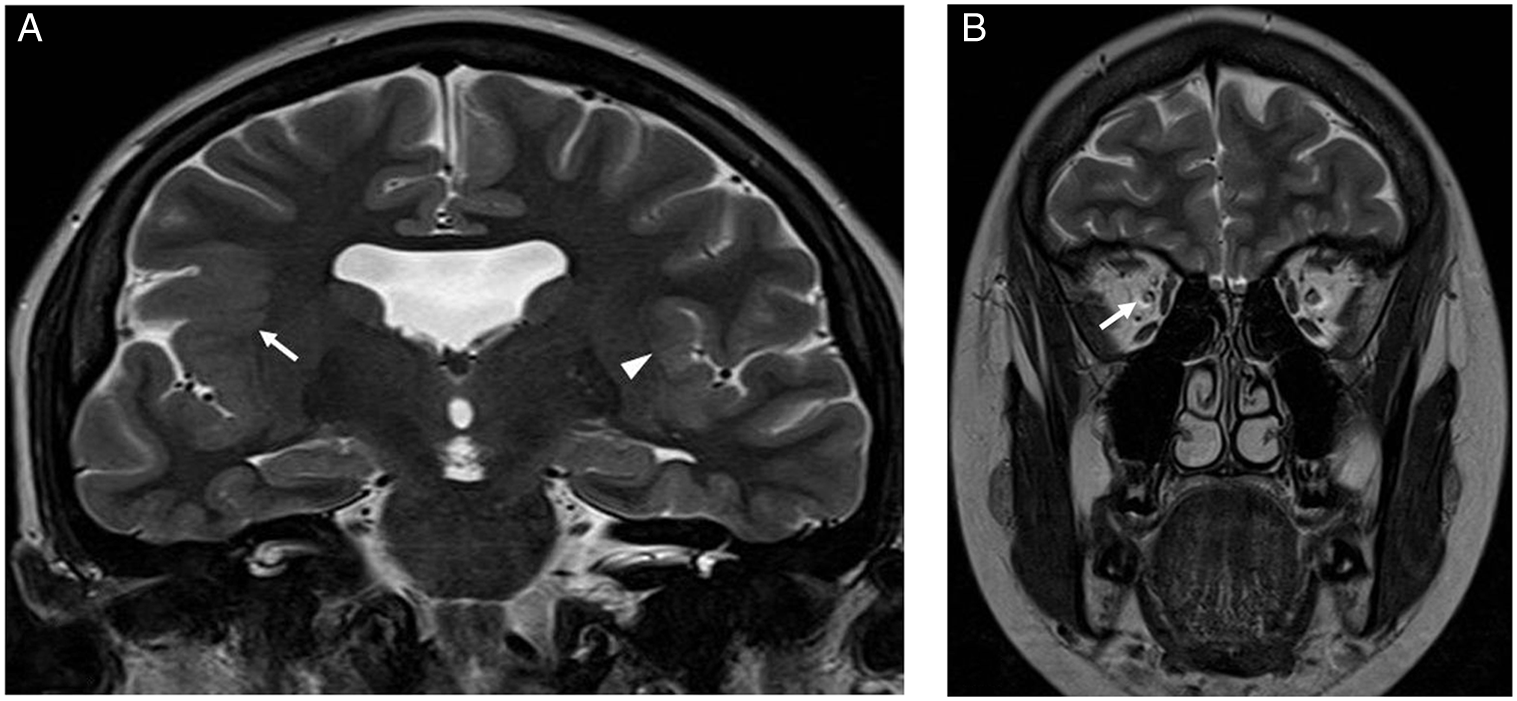

Septo-optic-pituitary dysplasia (SOD) is a neurodevelopmental abnormality that consists of optic nerve(s) hypoplasia (ONH) in association with hypopituitarism and/or midline brain abnormalities (absent septum pellucidum and/or abnormal corpus callosum) (Figures 1 and 2). In addition, neuronal migration disorders (NMD) (Figure 3) have been reported in some patients with SOD. ONH may also occur in isolation. Reference Garcia-Filion and Borchert1,Reference Webb and Dattani2

Figure 1: Brain MRI images of a 7-month-old male with severe bilateral visual impairment. (A) Coronal T2-weighted image showing absent septum pellucidum. (B) Coronal fat saturated T2-weighted image of the orbits showing small intraorbital optic nerves bilaterally (arrows).

Figure 2: Sagittal T1-weighted brain MRI image of a 7-month-old male with visual impairment showing an ectopic position of the neurohypophysis. The posterior bright pituitary spot (arrow) is visualized within the hypothalamus region. In addition, the pituitary infundibulum is absent.

Figure 3: Brain MRI images of a 17-year-old female with impaired vision of the right eye and focal epilepsy arising from the right cerebral hemisphere. (A) Coronal T2-weighted image showing absent septum pellucidum and polymicrogyria involving the left perisylvian region (arrow head) and right fronto-parietal-temporal lobes including the sylvian fissure (arrow). (B) Coronal T2-weighted image of the orbits showing a small right optic nerve (arrow).

ONH/SOD likely develop in early pregnancy, around 4 to 6 weeks of gestation, reflecting a disruptive process occurring in the early stages of forebrain development and an important time for the formation of the anterior neural plate. Reference Webb and Dattani2–Reference Taylor4 Genetic etiology explains only a minority (<1%) of cases with causes acquired in utero being implicated in other patients. Reference Webb and Dattani2,Reference Garcia-Filion, Fink, Geffner and Borchert5,Reference Dattani, Martinez-Barbera and Thomas6

The incidence rate of ONH/SOD in the province of Manitoba, Canada, is very high at 53.3 per 100,000 live births during 2010–2014 (i.e., 1 in 1875 live births) for unknown reasons, Reference Khaper, Bunge and Clark7 while the annual incidence rates were lower at 10.9 per 100,000 in Northwest England, Reference Patel, McNally, Harrison, Lloyd and Clayton8 and significantly lower at 2.4 per 100,000 residents in Olmsted county, Minnesota, USA. Reference Mohney, Young and Diehl9

ONH/SOD are common causes of congenital visual impairment. The best-corrected visual acuity in patients with ONH/SOD vary widely from normal to no light perception. Reference Garcia-Filion and Borchert1 A prior study which focused on the ophthalmological features in our cohort has been published. Reference Salman, Hossain, Carson, Ruth and Clark10

Our primary hypothesis was that a wide range of neuroimaging abnormalities, beyond midline abnormalities, occur commonly in patients with ONH/SOD. The primary aim was to ascertain the prevalence of abnormal neuroimaging features and their associations with each other in patients with ONH/SOD and compare them with studies from the medical literature. A secondary hypothesis was that there is no sex difference in the various abnormal neuroimaging features, since most studies reported no sex difference among the clinical features in patients with ONH/SOD. Our secondary aim was to compare the prevalence of neuroimaging features among males and females who have ONH/SOD.

Methods

Patients

Our cohort of patients was identified from two sources. The first was clinic letters from the sections of pediatric neurology and pediatric ophthalmology from January 1990 to August 2019, and the second source was through searching a database of all patients assessed in the section of pediatric endocrinology since 1986, for patients with the diagnosis of ONH/SOD. The diagnosis was verified by one of the authors (MSS), who has clinical expertise in these disorders. A small optic disk or disks on ophthalmoscopy documented in the ophthalmology clinic letters confirmed the diagnosis of ONH in our cohort. Only residents of Manitoba were included in this study. Ethics approval was granted by the Health Research Ethics Board, University of Manitoba.

Variables

Basic demographic and neuroimaging data were extracted and included sex, and age at their clinic visits and at the end of the study (30th June 2020).

Neuroimaging data were obtained mostly from reviewing brain MRI scans. Infrequently, when the actual scans were not available, then data were extracted from the MRI report. Rarely, when MRI was not performed, a high-quality CT scan was reviewed. Brain MRI was acquired on 1.5- or 3-Tesla MRI scanner (GE) using standardized protocol with sagittal T1-weighted, axial/ coronal T2-weighted, and axial/ coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. Additional MRI scans with pituitary and orbital views were also reviewed. Supplemental imaging sequences were performed as needed including T2*, DWI, ADC (apparent diffusion coefficients) maps, fast spoiled gradient echo (FSPGR) images, and MRA. Contrast with Gadolinium was given at the discretion of the radiologist. All initial and subsequent brain MRI images available that were completed by June 2020 were reviewed by a pediatric radiologist with expertise in neuroimaging (KR).

The data extracted included age at the time of the neuroimaging scan(s), and structural abnormalities (i.e., abnormal size, shape, absence, laterality [unilateral vs. bilateral], and side [right vs. left]) in infra- and supratentorial structures including the cortex and white matter, pituitary gland, corpus callosum, septum pellucidum, deep gray matter, olfactory bulbs-tracts/sulci, falx cerebri, and optic nerves/ chiasm. Careful visual inspection of each scan by an experienced pediatric radiologist (KR) was used to determine if there was a decrease in the size of the various neuroimaging features described. When there was any doubt, then comparison with published age-specific normative data were undertaken. For example, for the assessment of optic nerve size, we used the standardized method and measurements stratified by age groups provided by Janthanimi and Dumrongpisutikul study. Reference Janthanimi and Dumrongpisutikul11 The data were converted to numerical variables to enable statistical analysis and modeling. All extracted data were checked at least twice.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were carried out using SAS/STAT® software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Chi-squared, Fisher’s exact, and Wilcoxon sign-rank tests were used to investigate the association between or among categorical variables. ANOVA was used to compare the mean of continuous variables against categorical variables. Normality assumption of continuous variables were checked by Shapiro–Wilk test and presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) if they had a normal distribution, otherwise median, quartiles, minimum, and maximum values were reported.

Results

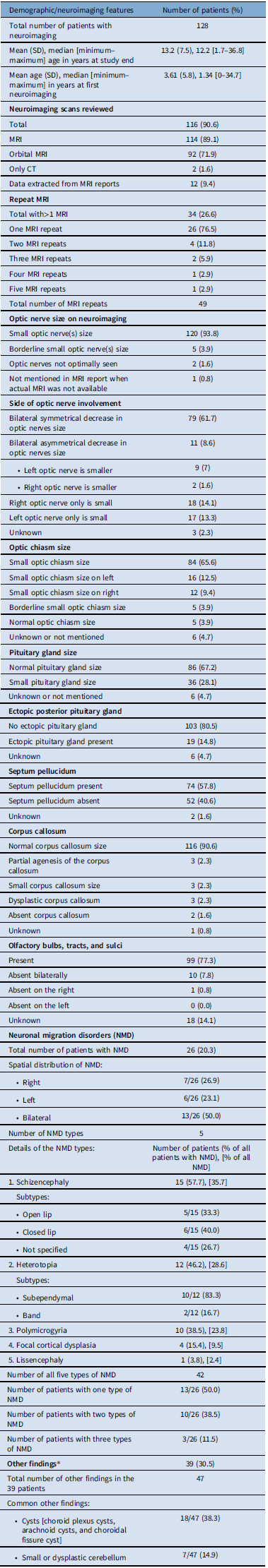

There were 128 patients (M = 70) with ONH/SOD who had neuroimaging studies. Their median age (interquartile range) at study end was 12.2 (7.4–17.6) years. Their neuroimaging characteristics and findings are displayed in Table 1. Figures 1 –3 show some of the abnormal neuroimaging features.

Table 1: Demographic and ‡neuroimaging features in patients with optic nerve hypoplasia and septo-optic-pituitary dysplasia

‡Adapted with permission from reference 37, Table 3, Salman MS, et al. Risk factors in children with optic nerve hypoplasia and septo-optic dysplasia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023;00:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15678; *See Supplementary Table 1 for details.

Almost all patients had small optic nerves and chiasm sizes on neuroimaging and in the majority it was bilateral. Most patients had normal corpus callosum. The olfactory bulbs-tracts were absent in 11 cases. The olfactory sulci were also absent in the same 11 cases. Five types of NMD were seen in our cohort with schizencephaly being the most common. NMD was bilateral in 13 of the 26 patients who had NMD. The falx cerebri was not adequately visualized in many scans to determine its presence or absence reliably. Incidental neuroimaging findings in 39 patients are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and notably include cerebellar abnormalities.

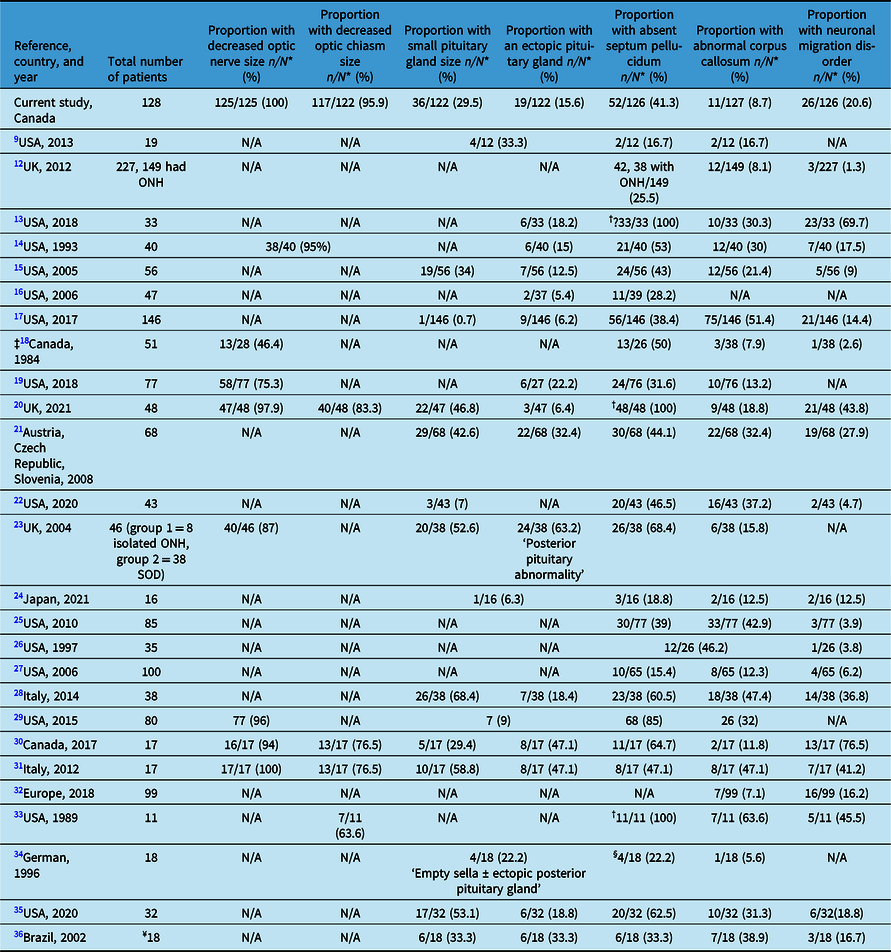

Table 2 shows the prevalence of the main abnormal neuroimaging features in patients with ONH/SOD from 26 studies in comparison with our cohort. Reference Mohney, Young and Diehl9,Reference Atapattu, Ainsworth and Willshaw12–Reference Antonini, Grecco Filho, Elias, Moreira and Castro36 A recent study on risk factors in ONH/SOD in 111 of our 128 cases shows additional clinical details in conjunction with a summary of some of the neuroimaging features. Reference Salman, Ruth, Yogendran, Rozovsky and Lix37

Table 2: Radiological features in optic nerve hypoplasia and septo-optic-pituitary dysplasia (ONH/SOD) based on reports from the medical literature

N*: Number of patients with adequate neuroimaging; N/A: not available; †: part of the inclusion criteria; ‡: older study with outdated imaging modalities (13 of 38 had pneumoencephalograms, three ventriculograms, six cerebral angiograms, and 26 of 38 CT scans); §: cavum septum pellucidum; ¥: 18 had cerebral midline developmental anomalies and 11 had ONH, who were not analyzed separately.

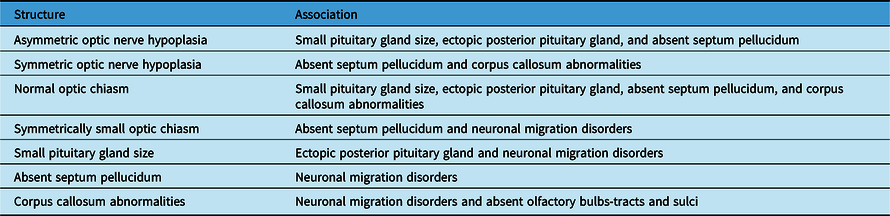

Table 3: Summary of the significant neuroimaging associations

Sex and Neuroimaging Findings

Optic nerves (N = 125) and chiasm sizes (N = 122) on MRI were significantly different by sex (p = 0.049). Males were significantly more likely to have bilaterally small optic nerves (79.7%) and optic chiasm (80.9%) sizes compared with females (62.5 and 63%, respectively), while females were significantly more likely to have a smaller left optic nerve (21.4%) and left chiasm (22.2%) sizes compared with males (7.3% and 5.9%, respectively).

Otherwise, sex was not associated with other neuroimaging structural abnormalities (i.e., small pituitary size, ectopic posterior pituitary gland, absent septum pellucidum, abnormal corpus callosum, presence of NMD, types and laterality of NMD, absent olfactory bulbs-tracts, and olfactory sulci).

Associations Between Optic Nerves and Chiasm Sizes with Other Structural Brain Abnormalities

Optic Nerves and Chiasm

A symmetrically small optic chiasm size was significantly associated with a symmetrical or an asymmetrical ONH compared with unilateral ONH (N = 121, 96.1% or 100% vs. 14.7%, p < 0.0001), and in cases with an asymmetrically small optic chiasm size, the affected side of the chiasm was significantly concordant with the unilateral ONH side (p < 0.0001).

Optic Nerves

A small pituitary gland size was significantly associated with an asymmetrically small compared with a symmetrically or a unilaterally small optic nerve(s) (N = 120, 90% vs. 30.3% or 5.9%, p < 0.0001). Similarly, the presence of an ectopic posterior pituitary gland was significantly associated with an asymmetrically small compared with a symmetrically or a unilaterally small optic nerve(s) (N = 120, 50% vs. 14.5% or 2.9%, p = 0.002). Absent septum pellucidum was significantly associated with an asymmetrically or a symmetrically reduced optic nerves sizes compared with a unilaterally reduced optic nerve size (N = 123, 54.6% or 50% vs. 17.7%, p = 0.004). There was a trend for corpus callosum abnormalities to be associated with a symmetrically small optic nerves compared with an asymmetrically or a unilaterally small optic nerves (N = 124, 12.7% vs. 0% [for each asymmetrically or a unilaterally small optic nerves], p = 0.051). The presence of NMD and the absence of olfactory bulbs-tracts and sulci were not associated with the laterality of ONH on MRI.

Optic Chiasm

A small pituitary gland size was significantly associated with a normal compared with a symmetrically or an asymmetrically small optic chiasm size (N = 120, 60% vs. 35.6% or 0%, p < 0.0001). Similarly, the presence of an ectopic posterior pituitary gland was significantly associated with a normal compared with a symmetrically or an asymmetrically small optic chiasm size (N = 119, 40% vs. 17.4% or 0%, p = 0.008). Absent septum pellucidum was significantly associated with a symmetrically small or a normal optic chiasm size compared with an asymmetrically small chiasm size (N = 122, 50.6% or 40% vs. 10.7%, p = 0.0003). Corpus callosum abnormalities were significantly associated with a normal optic chiasm size compared with a symmetrically or an asymmetrically small chiasm size (N = 122, 40% vs.7.9% or 0%, p = 0.02). The presence of NMD was significantly associated with a symmetrically small optic chiasm compared with an asymmetrically small or a normal optic chiasm size on MRI (N = 122, 27% vs. 3.6% or 0%, p = 0.01). The absence of the olfactory bulbs-tracts and sulci was not associated with optic chiasm size on MRI.

Associations among Structural Brain Abnormalities

Pituitary Gland

A small pituitary gland size was significantly associated with the presence of an ectopic posterior pituitary gland compared with a normal pituitary gland size (N = 121, 48.6% vs. 1.2%, p < 0.0001) and the presence compared with absence of NMD (N = 122, 33.3% vs. 16.3%, p = 0.04). Pituitary gland size was not significantly associated with absent septum pellucidum, corpus callosum abnormalities, and the absence of the olfactory bulbs-tracts and sulci.

Ectopic Posterior Pituitary Gland

The presence of an ectopic posterior pituitary gland was not associated with absent septum pellucidum, corpus callosum abnormalities, the presence of NMD, and the absence of the olfactory bulbs-tracts and sulci.

Septum Pellucidum

Absent septum pellucidum was significantly associated with the presence compared with absence of NMD (N = 126, 36.5% vs. 9.5%, p = 0.0002). Absent septum pellucidum was not associated with abnormalities in the corpus callosum and the absence of the olfactory bulbs-tracts and sulci.

Corpus Callosum

Corpus callosum abnormalities were significantly associated with the presence compared with absence of NMD (N = 127, 63.6% vs. 16.4%, p = 0.001) and the absence compared with the presence of the olfactory bulbs-tracts and sulci (N = 106, 30% vs. 4.2%, p = 0.02).

Number of Neuronal Migration Disorders Types Per Patient

There were no associations between the number of NMD types in each patient and: the laterality or asymmetry of the reduced optic nerves and chiasm sizes on MRI, small pituitary gland size, ectopic posterior pituitary gland, absent septum pellucidum, and corpus callosum abnormalities.

Olfactory Bulbs-Tracts and Sulci

The presence of heterotopia was significantly associated with the absence compared with the presence of the olfactory bulbs-tracts and sulci (N = 106, 40% vs. 8.4%, p = 0.02). There were no associations between the presence of all NMD combined, schizencephaly, and polymicrogyria and the absence of the olfactory bulbs-tracts and sulci.

Table 3 shows a summary of the significant associations among structural abnormalities found on neuroimaging in patients with ONH/SOD.

Discussion

Patients with ONH/SOD make up one of the largest groups of patients with congenital visual impairment. The etiology of ONH/SOD remains unknown in most cases and appears to be multifactorial. ONH has been described in various syndromic, chromosomal, inherited, and de novo genetic disorders. Overall, genetic abnormalities account only for a very small fraction of cases (<1%) with ONH. Reference Webb and Dattani2 Mutations in HESX, acting as a transcriptional repressor, was the first of a handful genes described as being causative of ONH/SOD in 1998. Reference Dattani, Martinez-Barbera and Thomas6 Other genes include mutations in PAX6, SOX2, SOX3, and OTX2. Reference Chen, Yin, Lewis and Schaaf38,Reference Ganau, Huet, Syrmos, Meloni and Jayamohan39

Various neuroimaging abnormalities, and especially absent septum pellucidum and small pituitary gland size with or without hypopituitarism, have been described in patients with SOD. Reference Riedl, Vosahlo and Battelino21,Reference Birkebaek, Patel and Wright23,Reference Severino, Allegri and Pistorio28,Reference Alt, Shevell, Poulin, Rosenblatt, Saint-Martin and Srour30,Reference Wadams, Gupta, Novotny and Tebben35,Reference Antonini, Grecco Filho, Elias, Moreira and Castro36 Table 2 summarizes some of the neuroimaging findings reported in 26 studies from 5 countries (Canada, USA, Europe, Japan, and Brazil) across four continents. Reference Mohney, Young and Diehl9,Reference Atapattu, Ainsworth and Willshaw12–Reference Antonini, Grecco Filho, Elias, Moreira and Castro36 Most studies from the 1990s onward, when brain MRI resolution improved substantially, like our study confirmed the reduced sizes of the optic nerve(s) and optic chiasm on brain MRI in the majority of patients with ONH/SOD. Reference Ward, Connolly and Griffiths20,Reference Cemeroglu, Coulas and Kleis29,Reference Alt, Shevell, Poulin, Rosenblatt, Saint-Martin and Srour30

The clinical features of ONH/SOD are similar in both males and females. Therefore, we were not expecting to find an association between sex and any neuroimaging abnormality. The association of sex and laterality of the reduced optic nerves and chiasm sizes in our study is interesting but needs to be replicated before any conclusions can be drawn. Its significance is uncertain.

Our study, unlike most other studies, included details on the symmetry in addition to laterality of the reduced optic nerves and chiasm sizes on neuroimaging. The analysis revealed interesting associations among the abnormal neuroimaging features in patients with ONH/SOD (Table 3). As anticipated, both the symmetry and laterality of ONH and reduced chiasm size were concordant, as reported previously. Reference Ward, Connolly and Griffiths20 Symmetric or asymmetric ONH (rather than unilateral ONH), and normal or symmetrically small optic chiasm (rather than asymmetric optic chiasm) were significantly more likely to be associated with other neuroimaging abnormalities. Other studies also reported that bilateral ONH was more likely than unilateral ONH to be associated with: more severe pituitary gland abnormalities and corpus callosum hypoplasia on MRI, Reference Riedl, Vosahlo and Battelino21 and clinical or neuroimaging abnormalities. Reference Mohney, Young and Diehl9,Reference Garcia-Filion, Almarzouki, Fink, Geffner, Nelson and Borchert17 However, some studies reported no association between ONH laterality and the presence of pituitary abnormalities, Reference Qian, Fouzdar Jain, Morgan, Kruse, Cabrera and Suh19 or absent septum pellucidum, Reference Garcia-Filion, Almarzouki, Fink, Geffner, Nelson and Borchert17 on MRI. In general, it appears that unilateral ONH, with or without an asymmetrically small optic chiasm, may potentially have a different etiology from bilateral ONH based on the associated neuroimaging features. This speculation deserves further study.

Absence of the septum pellucidum is associated with corpus callosum abnormalities but not pituitary gland malformation. Reference Garcia-Filion, Almarzouki, Fink, Geffner, Nelson and Borchert17 Our study concurred with the latter finding only, since absent septum pellucidum was not associated with corpus callosum abnormalities among our patients.

NMD were significantly associated with all midline structural abnormalities reported in this study including symmetrically small optic chiasm size, but not ONH. Cortical malformations were also reported to occur more commonly in patients with midline abnormalities, Reference Alt, Shevell, Poulin, Rosenblatt, Saint-Martin and Srour30 especially absent SP. Reference Riedl, Vosahlo and Battelino21 These associations may be related to the etiology of SOD, for example, a hemorrhage occurring around 2–3 months postconception causing disruption of neuronal migration and at the same time interfering with the development of midline brain structures. Reference Alt, Shevell, Poulin, Rosenblatt, Saint-Martin and Srour30

The prevalence of the various other neuroimaging abnormalities reported in our study generally falls within the ranges described in other studies (Table 2). Reference Mohney, Young and Diehl9,Reference Atapattu, Ainsworth and Willshaw12–Reference Antonini, Grecco Filho, Elias, Moreira and Castro36 In most studies, a small pituitary gland size was reported in less than 60% of patients and in many studies in about 30–55%, while ectopic posterior pituitary gland was described less frequently (<50%) and in many studies in 5–33% of patients. A wider range for the occurrence of absent septum pellucidum (17 and up to 100%) and a narrower prevalence range for abnormal corpus callosum (mostly 8–40%) have been reported across many studies. The wide ranges reported in Table 2 are likely due to the variable inclusion criteria among various study participants, source of the patients (i.e., general/specialized health care centers or clinics for example, neurology/endocrinology clinics), sample size, genetic/ethnic background of the patients, variable phenotype of SOD, selection bias of the study participants (those with more severe clinical or neuroimaging abnormalities are more likely to be included), the focus of the study (i.e., the neuroimaging abnormalities investigated), and type of study (i.e., clinical or radiological). Reference Benson, Nascene, Truwit and McKinney13

Several studies reported NMD in patients with ONH/SOD (typically <45% of the cases) and in many studies in about 1–20% of cases. Such patients have been described as having “SOD plus” by some authors. Reference Alt, Shevell, Poulin, Rosenblatt, Saint-Martin and Srour30 NMD are not part of the inclusion criteria for the diagnosis of SOD. NMD were seen occasionally in our cohort (20%). In 13 of our 26 patients with NMD, both cerebral hemispheres were involved, which has been reported previously, Reference Ward, Connolly and Griffiths20,Reference Alt, Shevell, Poulin, Rosenblatt, Saint-Martin and Srour30 suggesting a widespread abnormal process occurring during a critical period of cerebral hemispheres development. Such patients may have an acquired cause, at least in some cases, since some had more than one type of NMD. Indeed, two or more types of NMD have been reported in some patients with SOD including schizencephaly and polymicrogyria. Reference Ward, Connolly and Griffiths20,Reference Alt, Shevell, Poulin, Rosenblatt, Saint-Martin and Srour30 The number of NMD types seen in some of our patients, varying between 1 and 3, and the laterality of NMD were not associated with the laterality of the small optic nerves or chiasm sizes on neuroimaging, suggesting that the two entities occur independently, that is, one abnormality does not seem to cause the other.

The significant associations between the absence of the olfactory bulbs-tracts/olfactory sulci and: corpus callosum abnormalities and the presence of heterotopia in intriguing and requires confirmation in future studies. Benson et al. reported that 42–44% of their 33 patients with SOD also had olfactory sulcus and/or olfactory bulbs-tracts hypoplasia, and that in some patients there was discordance between the two sides in the aforementioned abnormalities. Reference Benson, Nascene, Truwit and McKinney13 In our study, a smaller percentage of our cases (8.6%) showed the absence of these structures and that there was full concordance between olfactory bulbs-tracts absence and olfactory sulci absence. In 18 of our cases, these structures could not be adequately assessed on neuroimaging. In addition, the study by Benson et al. noted that anterior falx dysplasia was present in 16 of their 33 cases with SOD. Reference Benson, Nascene, Truwit and McKinney13 Several scans among our cases were not adequate in quality to assess for the presence and integrity of this structure.

Interestingly, all these abnormal inconstant midline features, together with absent septum pellucidum and corpus callosum or pituitary gland abnormalities, are shared with the various types of holoprosencephaly. However, failure of the prosencephalon to separate into two cerebral hemispheric to varying extents in holoprosencephaly is a distinct feature of this disorder. Reference Fitz40

ONH/SOD should be considered as a disease spectrum rather than discrete; albeit, somewhat related disease entities. The latter being: ONH with hypopituitarism, ONH with midline brain defects, or a triad of ONH, hypopituitarism, and midline brain defects, since variable clinical and neuroimaging features may or may not be associated with either unilateral or bilateral ONH. ONH should be considered the central feature of this disorder occurring with or without a variable spectrum of other neuroimaging features and/or hypopituitarism.

In addition to the importance of investigating the laterality of ONH, we have also shown that the symmetry of the reduced optic nerves and chiasm sizes should also be considered and evaluated in future studies. It remains to be proven whether the variable disease spectrum described is caused by different etiologies, for example, genetic or acquired disruption of brain development in utero occurring at different critical time periods, which ultimately determines the various phenotypes seen.

Study Limitations

Our investigation is subject to the limitations of a retrospective neuroimaging review. Some of the neuroimaging studies were performed a few decades ago with poorer MRI resolution than contemporary MRI studies. A few MRI scans were not available for review and rarely, and some patients only had CT scans. Therefore, the information extracted from such cases may not be comprehensive.

Future Research Directions

More research is needed to elucidate the cause for the wide spectrum of neuroimaging abnormalities seen in patients with ONH/SOD.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.263.

Data availability statement

All data are displayed in the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We thank the staff at the section of endocrinology for sharing their database of patients.

Statement of authorship

MSS initiated and designed the study. He contributed to patients’ ascertainment, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. He wrote the first draft of the manuscript and edited subsequent drafts. SH performed the statistical analysis, checked and interpreted the results, and edited several versions of the manuscript. KR performed the neuroimaging data collection, reviewed available MRI/CT, checked the accuracy of the imaging data, helped in neuroimaging data interpretation, made Figures 1–3, and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the last version of the paper.

Competing interests

The authors report that there are no competing or conflict of interests to declare.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study has been granted by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba.

List of abbreviations

SD: standard deviation; NMD: neuronal migration disorders; ONH: optic nerve hypoplasia; SOD: septo-optic-pituitary dysplasia