Introduction

“It haunts you; it haunts you, it haunts me to this day” Footnote 1

– Survivor, Child and Parent Resource Institution (CPRI), London, Ontario

Across Canada, the horrors of the institutionalization of people labelled with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD)Footnote 2 haunt disabled lives and histories. For the first century following confederation, large-scale residential institutions were the primary response to the housing and support needs of disabled people. In these institutions, infants, children, and adults with IDD who were classified as “feebleminded,” were enclosed and isolated with no possibility of a life outside the walls (Burghardt, Reference Burghardt2018). Even in death, labelled people could be isolated in unmarked, or mass graves at cemeteries within the institutions. In many residential institutions, disabled children and adults slept 50 to a room, used toilets without doors, and were subject to solitary confinement, overmedication, and forced labour (Rossiter & Rinaldi, Reference Rossiter and Rinaldi2018). The largest institutions in Canada, such as the Rideau Regional Centre and the Huronia Regional Centre were built to contain more than 2000 disabled people, and at their peak more than 20,000 people were confined in institutions annually (Brown and Radford, Reference Brown and Radford2015).

The ghosts of confinement and isolation continue to haunt IDD housing policies today; despite commitments to inclusion and community-living within contemporary disability policies, such as Ontario’s Services and Supports to Promote the Social Inclusion of Persons with Developmental Disabilities Act, 2008, and Canada’s Disability Inclusion Action Plan, 2022. Although deinstitutionalization has been a guiding focus of organized disability advocacy since the establishment of the independent living movement over 50 years ago, traditional residential institutions remain operational in six Canadian provinces. Why does the institutionalization of people labelled with IDD still occur in Canada?

We argue that institutionalization persists because of an enduring policy legacy of systemic ableism, which haunts Canadian IDD housing policies. This legacy originated with the colonization of Canada and the construction of the first asylums and residential institutions prior to confederation. It continues through contemporary IDD housing models, such as group homes, which can replicate many of the same institutional characteristics (such as surveillance, isolation, restraint, and violence). To encapsulate these modern realities of IDD housing, this is how a joint task force including People First of Canada, Canada’s largest self-advocacy organization for people with IDD, defines an institution:

“An institution is any place in which people who have been labeled as having an intellectual disability are isolated, segregated and/or congregated. An institution is any place in which people do not have, or are not allowed to exercise control over their lives and their day to day decisions. An institution is not defined merely by its size.” Footnote 3

Drawing upon this definition, this article considers institutionalization as any form of IDD housing policy which contributes to these processes of isolation, segregation, congregation, and the loss of autonomy over one’s life and decisions. IDD housing policy refers to the various municipal, provincial, territorial or federal policies and programs which provide housing, funding, or supports (home care, or informal care supports) for people labelled with IDD. Contemporary IDD housing has a mix of operators, providers, and funders spanning social housing (identified units), health (long-term residential care, psychiatric settings), community/social services (group homes and institutions), and correctional services (justice-based settings) (Linton, Reference Linton, Rinaldi and Rossiter2023). Therefore, IDD housing policy can involve complex forms of multilevel governance, wherein broad approaches to IDD supports are communicated and coordinated across levels of government, ministries, service silos, jurisdictions, organizations and implementers (Dickson, Reference Dickson2022; Linton, Reference Linton, Rinaldi and Rossiter2023). This article focuses on developmental services (shorthand for IDD services), which constitute the vast majority of publicly funded IDD housing supports and fall under the jurisdiction of provincial ministries and departments in charge of social services. Provincially funded developmental services in IDD housing include group homes, semi-independent living/ IDD home care supports, and residential institutions.

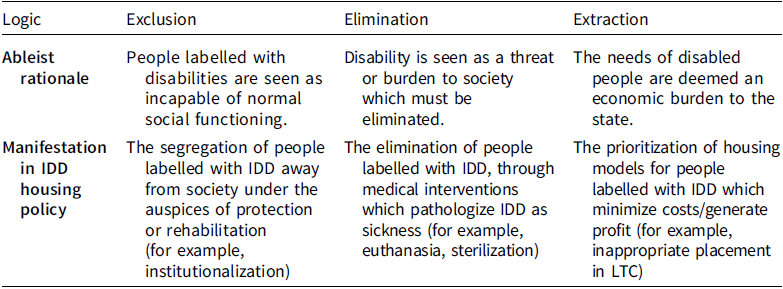

We further argue that systemic ableism “haunts” (Gordon, Reference Gordon1997) IDD housing policy through three persistent logics that rationalize discrimination against people labelled with IDD: exclusion, elimination and extraction. These spectral logics are embedded within Canada’s IDD housing policy institutions, and thus counteract formal commitments to the deinstitutionalization and social inclusion of people with IDD. We draw evidence from individual and focus group interviews with relevant policy actors and service users in two Canadian provinces, Ontario and Nova Scotia, which we complement with a review of historical IDD housing policy and program documents across Canada. In the next section, we situate systemic ableism as a policy legacy by identifying these three ableist logics, embedded within IDD housing policy structures since the establishment of residential institutions, which continue to haunt IDD housing policy.

Three Spectral Logics of Systemic Ableism

Systemic ableism in Canada shares a heritage with the discriminatory logic of settler colonialism, which broadly categorizes “whole groups of people as being undeveloped, underdeveloped and/or wrongly developed” (Mills & LeFrançois, Reference Mills and Lefrançois2018: 504). For the Canadian state, spatial and social exclusion has facilitated processes of identity and nation building (Alfred, Reference Alfred2005; Simpson, Reference Simpson2014). In this way, systemic ableism is part of the larger settler culture of removal, replacement, and elimination (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2006; Jaffee & John, Reference Jaffee and John2018). In this article, we identify three logics that undergird systemic ableism in Canadian IDD housing policy: exclusion, elimination, and extraction. By identifying these underlying logics and following their historical evolution from their origins to present manifestations, we contribute to understanding how systemic ableism haunts Canadian IDD housing policies.

Ableism refers broadly to prejudices against disabled people that assign a system of values to bodies and minds, wherein some forms of living (like walking instead of wheeling) are superior to others (Fritsch et al., Reference Fritsch, Monaghan and Van der Meulen2022; Nario-Redmond, Reference Nario-Redmond2019). The manifestation of ableism depends on context, form of impairment, identity, perceived identity, gender, religion, Indigeneity, ethnicity, and race. People labelled with IDD experience a specific form of ableism which infantilizes or renders them deviant, however the precise implications of these forms of stigma vary tremendously at the individual level (Werner and Scior, Reference Werner, Scior, Scior and Werner2016). Therefore, while manifestations of ableism are complex and multifarious, they share a common origin in the othering and exclusion of disabled people in contrast to non-disabled normativity.

Ableist normativity is the engine of systematization which subsumes these prejudicial attitudes into the broader project of removing some manifestations of disability from the public, and broader social imagination. In other words, the imagination of a state of “normal ability” legitimizes the absence of those whose disability excludes them from participating in social functions that they cannot access, creating what Titchkosky calls “(i)ndifference towards the absent presence of disability” (2011: 123). Against the imagined form of ableist normativity, IDD enlarges, disrupts, pauses, questions, and clarifies what it means to be human (Goodley and Runswick-Cole, Reference Goodley and Runswick-Cole2016). The negative social construction of disability is foundational to systemic ableism, and generates consensus around the problematization of disability, informing specific types of policy solutions within these structures. To this end, we propose three interrelated logics (see Table 1) to explain how ableism haunts the structure of IDD housing policy in Canada: the logics of exclusion, elimination, and extraction.

The logic of exclusion is fundamental to IDD housing policy in Canada and is best reflected by residential institutions. These human warehouses were designed to segregate people labelled with IDD from the rest of society, where they could either be rehabilitated, or permanently languish (Burghardt, Reference Burghardt2018). While the group home model has largely replaced the institutional model, it is haunted by many of the same abhorrent characteristics—such as surveillance, isolation, restraint, abuse, and invisibility—all legible in the underlying logic of exclusion. This logic is founded on false, ableist stereotypes that people with IDD are either incapable of social functioning, thus infantilizing and diminishing their capabilities to rationalize their exclusion, or are violent sources of social contagion, which justifies permanent detention (Ben-Moshe, Reference Ben-Moshe2020; Bach, Reference Bach2017; Oliver and Barnes, Reference Oliver and Barnes2012).

The second logic of elimination positions people with IDD as a threat or burden to society (McLaren, Reference McLaren1990). While exclusion offers a sheen of benevolence through the discourse of rehabilitation, the logic of elimination gives rise to solutions that legitimize the loss of disabled lives. We explore the amendments to Canada’s medical assistance in dying policy as a pertinent contemporary example of how this logic haunts IDD policy.

Table 1. Three Logics of Systemic Ableism in Canadian IDD Housing Policy

Finally, the logic of extraction represents the natural progression of the first two ableist logics when confronted by the desire to generate profit. While this logic shares the false stereotype of disabled bodies as essentially non-productive, it privileges solutions that constrain costs by extracting value or creating economies of scale in the provision of housing to people labelled with IDD. The spectre of extraction is evident in the recent re-emergence of congregate housing options due to resource constraints, particularly the inappropriate confinement of people labelled with IDD into long-term care (LTC) facilities.

In the next section, we introduce the haunting conceptual framework as a complement to historical institutionalist approaches to policy ideas and change. Following our methodology, we present textual evidence of contemporary manifestations of each of the three logics of systemic ableism. We then conclude by addressing the potential implications for advocates and policymakers seeking to exorcise the ableist logics of exclusion, elimination and extraction from Canadian IDD housing policy.

Haunting and Policy Legacies

We employ the haunting conceptual framework to overcome the limitations of focusing solely on ableism as a policy legacy. The concept of policy legacies originates from the study of historical institutionalism and has been tightly interlinked to the study of path dependency, policy feedbacks, and policy change (Pierson, Reference Pierson1993; Reference Pierson2004; Thelen, Reference Thelen1999; Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). While for some, policy legacies are understood as the institutions themselves, which reproduce embedded historical processes (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999: 382), others have positioned policy and political ideas as the catalyst for institutional legacies (see Hall, Reference Hall1993; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2002; Béland and Hacker, Reference Béland and Hacker2004). Ideas are more dynamic than institutions, but they are also more resilient to total disruption, and can be re-institutionalized in different forms (Béland and Cox, Reference Béland and Cox2010; Reference Béland and Cox2016). Systemic ableism is a broad idea that can be manifested in many social and political institutions. However, housing policy for people with IDD stands out as an exemplary case because of how deeply ableist ideas have been entrenched in policy instruments in this area. With the passage of legislation permitting and funding the development of residential institutions in Canada, explicitly ableist attitudes were legitimized by a broad and comprehensive policy approach to the perceived problem of IDD (Burghardt, Reference Burghardt2018). Therefore, we argue that the institutionalization of people with IDD continues to occur in Canada because the ideas of systemic ableism are still entrenched—both explicitly and spectrally—in current approaches to IDD housing policy.

Our argument expands upon neo-institutional approaches which emphasize gradualism to explain policy change. Within these approaches, policy legacies are commonly employed as a mechanism to explain path dependency within a specific policy area (Pierson, Reference Pierson2004; Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2009). Path dependency may result from the institutionalization of a policy idea, which gains legitimacy as it remains uncontested and proliferates over time (see Banting and Thompson, Reference Banting and Thompson2021). Policy legacies generate path-dependency by cultivating institutional avenues that limit the range of choices available to decision-makers, thereby locking in specific understandings of a policy problem (Pierson, Reference Pierson2004). The nature of path generation matters, as historical continuity and the culmination of lock-in effects disrupt the potential for transformative change (Djelic and Quack, Reference Djelic and Quack2007). For this reason, policy legacies are much more resistant to change than forms of policy discourse or policy frames, which are more receptive to contestation (see Rein, Reference Rein, Moran, Rein and Robert2006; Van Hulst and Yanow, Reference Van Hulst and Yanow2016). Therefore, within the scope of a policy legacy change is likely to be incremental and not significantly challenge the underlying ideational rationale.

Over the course of Canada’s history there has mostly been incremental change in the provision of IDD housing policy. The shift towards deinstitutionalization, propelled by the continued efforts of advocates in the independent living and community living movements beginning in the 1960s (Park et al., Reference Park, Monteiro, Kappel, Stienstra and Watters2003; Vanhala, Reference Vanhala and Smith2014), represented the most significant opportunity for major change. However, as we show in subsequent sections, despite the efforts of IDD advocates, and the explicit focus on deinstitutionalization in contemporary IDD policy design, residential institutions persist. The legacy of systemic ableism constrains the potential for more inclusive models of housing because these are incommensurable with the ableist logics that undergird Canadian IDD housing policy.

This highlights a shortcoming of the historical institutionalist literature, which has focused on how policy legacies make political institutions resistant to change at the expense of identifying the legacies themselves or why they persist. To ascribe linear causality to historical sequences through methods such as process tracing, historical institutionalist literature has given short shrift to the more ethereal ideational contexts that both limit the potential for change and disrupt accounts of history as progress. To fill this gap, we employ the concept of “haunting” or “hauntology” from sociology and cultural studies to identify the ways that discriminatory stereotypes about marginalized populations affect their broader social imaginaries, including their representation in contemporary policies (Derrida, Reference Derrida1994; Gordon, Reference Gordon1997; Bergland, Reference Bergland2000). Engaging with these social imaginaries is problematic for social scientific research precisely because these discriminatory legacies are often intangible by their nature (Wilson, Reference Wilson2018). To this end, we draw from Gordon, who describes the concept of haunting as “that which appears to be not there… a seething presence, acting on and often meddling with taken-for-granted realities, [for which] the ghost is just the sign, or the empirical evidence if you like, that tells you a haunting is taking place” (Reference Gordon1997: 8). Accounting for “that which is not there” is problematic for policy analysis, however identifying ghosts—in our case, the three “spectral” logics of systemic ableism—allows us to analyze how they haunt contemporary policies that explicitly oppose the logics of exclusion, elimination, and extraction.

What causes haunting to persist and ghosts to re-appear? Hartman’s (Reference Hartman2008) writing on how “the afterlife of slavery” haunts Black Americans in the present suggests that “the perilous conditions of the present establish the link between our age and a previous one in which freedom too was yet to be realized” (p.133). The persistence of conditions that limit freedom means the ghosts of past injustices have never been laid to rest, but rather are made to continue to haunt. This is useful in connecting haunting to policy legacies because these too are discernible by their impact on present conditions, where the legacy of discriminatory policies is legible in inequitable outcomes. In this way, Good (Reference Good2019) argues that engaging with haunting allows us to re-remember past injustices, which may have been remembered and forgotten many times within social imaginaries, by assessing how they meddle with the tangible present.

Haunting blurs the lines between the past, present, and future, thus allowing for a complication of the notion of legacies by allowing them to be seen as more than rigid ideational boundaries, and instead as old (dead) ideas that are enacted—potentially violently—over and over in the present. Indigenous politics scholars have operationalized haunting to understand how settler colonialism haunts contemporary politics (Tuck and Ree, Reference Tuck and Ree2015; Bergland, Reference Bergland2000). This is further reflected in critical geography, where hauntology is used to examine the way settlers are haunted by the colonial past, and the threat of Indigenous insurgence (Baloy, Reference Baloy2016; Elliott, Reference Elliott2021; Fortier, Reference Fortier2022). To this end, Tuck and Ree argue that haunting is the contemporary manifestation of past injustice: “(i)n the context of the settler colonial nation-state, the settler hero has inherited the debts of his forefathers. This is difficult, even annoying to those who just wish to go about their day” (Reference Tuck and Ree2015: 643). This highlights a key characteristic of haunting, as the invocation of past/present injustices are inconvenient and disruptive to dominant narratives of contemporary justice, progress, or inclusion.

Studies of residential institutions invoke haunting to grapple with the legacies of both the physical sites (Stenberg, Reference Stenberg2023; Beitiks, Reference Beitiks2012) and their enduring impact on former inhabitants who, once deinstitutionalized, were confined once more in what Dear and Wolch (Reference Dear and Wolch1987) call haunted “zones of dependence” (p. 71). Labelled people live with the spectre of confinement when, even if current housing and supports are stable, the death of a caregiver, or a rent increase can result in institutionalization (Dubé, Reference Dubé2016). Haunting persists in the social imaginary, where shuttered institutions are given afterlives as trans-institutionalized sites where the physical remains of institutions are transformed into group homes, hospitals, and psychiatric or long-term care facilities (Moon and Kearns Reference Moon and Kearns2016; Steele et al., Reference Steele, Phillippa Carnemolla, Kelly, Naing and Dowse2023; Chari, Reference Chari2024). Huronia Regional Centre became a training centre for the Ontario Provincial Police and a probation office.

If sufficiently disrupted, the ideational foundations of a policy legacy represent the most effective focal point for targeting institutional change, because they are the engine of an institution’s reproductive mechanism (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999: 397). This point is reflected in the disability policy literature, where for IDD advocates, the most promising avenues to challenge ableist stigma are found at the inter- or intra-personal levels, rather than at the structural level where these ideas are institutionalized and legitimized, and difficult to dislodge (Werner and Scior, Reference Werner, Scior, Scior and Werner2016). In the conclusion of this article, we examine potential pathways to disrupt the haunting logics of systemic ableism and to promote more inclusive housing models in Canada.

Methods

This article draws empirical evidence primarily from interviews with implementers and service users in the IDD housing policy sector in the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia and Ontario. This is complemented by the analysis of IDD housing data cross-provincially, drawn both from publicly available sources and the use of freedom of information requests (see Linton, Reference Linton2021), and an analysis of all policies pertaining to IDD housing policy at the federal and provincial level (see Dickson, Reference Dickson2023). The interview component draws from a sample of 32 interview participants, including bureaucrats working within provincial departments with purview over IDD housing programs (n = 4), managers and support staff at developmental services agencies providing IDD housing (n = 15), and people living in IDD housing (n = 13). In some cases, interview respondents could speak to experience in multiple roles. For example, all 6 of the managers who were interviewed had prior experience working as frontline support workers, which allowed them to speak to both how the support worker role has evolved over time, and how staff interaction affects implementation in the IDD housing sector. This was not a comparative case study and the sample was not designed to elicit generalizations about any specific population within the IDD housing policy sector in either province. Interviews were semi-structured and lasted between 60 to 90 minutes. With the sample of developmental services users, both individual interviews (n = 2) and focus group interviews (n = 11) were used. The three focus groups were comprised of 3 to 4 respondents and were conducted on site in residential settings.

This project employs two primary safeguards to protect the rights of participants labelled with IDD and received ethics approval from Concordia University Human Research Ethics Committee. First, participation in the study involved acquiring the consent of not only the person with IDD, but also of a family member or support staff who could confirm consent. This has the advantage of belaying concerns over whether the subject’s agreement to participate meets the threshold of informed consent using a specialized instrument called an assent and consent form with attestation by both parties (Bach and Rock, Reference Bach and Rock1996). To this end, it was necessary to secure provisional consent from the person with IDD first because there can be doubt as to whether participation is truly voluntary when a support worker or family member has agreed first, potentially creating external pressure for someone dependent on care (Griffin and Balandin, Reference Griffin, Balandin, Emerson, Hatton, Thompson and Trevor2004). The second safeguard involves extra measures to protect respondent confidentiality. People with IDD are a demographically small group, such that including verbatim quotes that identify the location of the respondent, even without attribution, can allow readers to possibly identify research subjects. Therefore, in addition to omitting identifying information, it was necessary to meticulously screen any verbatim quotes prior to inclusion in the text. While alternative research designs allow for more relaxed approaches to the acquisition of informed consent—specifically as it pertains to the assent and consent procedure—the strategies employed in this research design encapsulate an approach to research ethics that prioritizes safety and anonymity for all participants.

All interviews were audio recorded with accompanying notes for later analysis. Transcription and coding were conducted using qualitative analysis software. Parent codes were created for prevalent topic areas such as “implementation,” “austerity,” and “role of government,” with lower-level nodes generated for more specific thematic categories under each parent code. The interview data was collected as part of a larger project focusing more broadly on social inclusion policies for people with IDD in Canada (Dickson, Reference Dickson2023). This meant that the inclusivity of current housing models was a specific focus of interview discussions. Moreover, the interview sample contained staff and residents from several different housing models, including the residential institutional, group home and supported independent living models. Systemic ableism was not an explicit focus of the interview research; however, its frequent emergence in the interview discussions with governance actors at multiple levels of IDD housing policy lends support to its policy legacy.

Ghosts of Exclusion: The Persistence of Institutionalization

In 1839, the province of Upper Canada passed An Act to Authorise the Erection of an Asylum within this Province for the Reception of Insane and Lunatic Person, the first legislation in Canada to construct, fund, and develop criteria for admission and enclosure in residential institutions for people labelled with mental disorders. When passed, the policy was rationalized as an act of benevolent government interventionFootnote 4 , and Canada’s first residential institution, the Huronia Regional Centre (originally, the Orillia Asylum for Idiots) in Orillia, Ontario was designed to provide medical treatment to people with IDDFootnote 5 . As with all of Canada’s residential institutions, the Huronia Regional Centre was operated solely by the provincial government. From the outset, residential institutions pathologized IDD, thus rationalizing the need to isolate and contain “patients” away from the public (Spagnuolo, Reference Spagnuolo2019; Hutton et al., Reference Hutton, Peter Park, Johnson and Bramesfeld2017). This philosophy pervades contemporary approaches to institutionalization, where residents are housed in isolated buildings, often sharing small living spaces with several roommates. The quote below is taken from a focus group conducted with institutional residents in Nova Scotia, where residents shared small sleeping quarters in a single room with as many as four roommates whom they were assigned without choice:

“Myself, I have three roommates” (Institutional Resident 3)

“It can be pretty noisy where we are living. It can be pretty loud sometimes” (Institutional Resident 2)

“You can’t sleep at night. My roommate will wake you up and snore like a cow. I’d like to go back home and sleep in my bed. I miss my bed so much” (Institutional Resident 1)

These three residents are older adults, who have spent most of their lives confined in various residential institutions. The longing for the feeling of home and the comfort of their childhood mattress in their older age, speaks to the unsettling and overcrowded conditions that these places impose. In two focus group interviews inside a residential institution, participants spoke often of home, but never used this term to refer to their current residence. Another institutional resident identified their family’s house that they visit only once a year as home, while yet another spoke of their desire to live in a mobile home of their own one day. For institutional residents, the institution was never meant to feel like home. The buildings were placed in remote areas and designed with grand and imposing facades that gave the impression that “the asylum was a positive space, a symbol of medical and psychiatric advancement, and generally, a symbol of the growing authority of medicine in Canada at the time” (Viscardis Reference Viscardis2020: 60). The framing of IDD as a medical problem led to the residential institution as a policy solution. This solution was equally guided by the logic of exclusion, as the pathologization of IDD legitimized the segregation of afflicted persons, creating an ableist ideational foundation for Canadian IDD policy.

Failure of the Group Home Model

While the failure to fully deinstitutionalize is the most obvious evidence of the ableist logic of exclusion in Canadian IDD housing policy, the interviews demonstrate that the community living models that replaced the institutional model have also failed to deliver inclusive outcomes. Most notably, the group home model—predicated on housing three to eight individuals in standalone community residences with requisite support staff—maintains many institutional characteristics. This is due both to a lack of public investment to provide suitable staffing and funding, coupled with a “one size fits all” approach to service delivery that fails to engage the flexibility and creativity of person-centred care practices, instead replicating the procedures and culture of residential institutions (Mansell, Reference Mansell2006; Bigby et al., Reference Bigby, Wilson, Stancliffe, Balandin, Craig and Gambin2014). As a result, group home residents are often confronted by a lack of autonomy, both individually and relationally (see Chattoo and Ahmad, Reference Chattoo and Ahmad2008), which fundamentally limits their potential for social inclusion (Gappmayer, Reference Gappmayer2021). For example, without requisite support, people with IDD living in group homes are often denied the most basic opportunities for inclusion, such as the freedom to go to a café, see friends, have sex, or do their own grocery shopping (Bigby et al., Reference Bigby, Wilson, Stancliffe, Balandin, Craig and Gambin2014; Chin, Reference Chin2018). In these ways, the community living movement has been stalled by a pervasive logic of exclusion in Canadian IDD housing policy.

This can be partially understood as implementation failure of community living models due to resource scarcity and austerity in Canadian social services. The growth of neoliberalism both in policy and ideology was foundational to the development of the new disability services sector that emerged with the onset of deinstitutionalization. Sonpal-Valias identifies four components of neoliberalization in disability services: “program cutbacks and limitations; a new structure for program delivery; increased family and individual responsibility; and managerial techniques for scrutiny and accountability” (Reference Chartrand2019: 2). These components confound the provision of inclusive social services, which requires decentralized, tightly coordinated, and person-centred approaches to service planning, and can be expensive in the early stages of implementation (Joffe, Reference Joffe2010; Dickson, Reference Dickson2022; Reference Dickson2023). This emphasis on the importance of coordination and planning was evident in the following quotation from a senior civil servant in Nova Scotia:

We have a range of disability types and levels of support needed, some of which are really off the scale, and to support all of those people. It’s complicated. So, I talk about deinstitutionalization but we need to make sure that when people leave those places that the supports in place are going to be there in community… If you live in an institution where you have your prescriptions delivered… an occupational therapist, a behavioural interventionist, a dentist who comes to you, you know, nursing care, all that kind of stuff. When you go out into community, even into a small option home, we have to make sure that those same services are available… Like, everybody doesn’t have a doctor in Nova Scotia, so how easy is that going to be? (Nova Scotia Senior Civil Servant)

The hesitancy of this civil servant to support the transition from residential institutions to group homes belies serious doubts about the capacity of the provincial health and social services systems to sustain disabled life outside of an institution. The provinces that have failed to deinstitutionalize are those most constrained by austerity in the social services sector (Dickson, Reference Dickson2023: 140). Austerity jeopardizes deinstitutionalization, by limiting the capacity to build and sustain quality community living options. As Fritsch (Reference Fritsch2015a) notes, the independent living movement emerged alongside neoliberalism, intertwining processes of deinstitutionalization with frameworks of privatization, decentralization, and commercialization. Provinces seeking to address the conditions inside institutions had been simultaneously tasked with social housing by the federal government following new cost-sharing arrangements under the CAP in 1965 (Dear and Wolch, Reference Dear and Wolch1987), and leading to first generation community housing policies, such as Ontario’s Homes for Retarded Persons Act, 1966 (Simmons Reference Simmons1982, 185). In this period, watershed reports on the conditions of institutions were equally concerned with high costs, such that provinces were attracted by the ability to privatize group homes, and by the lower costs associated with decentralized care (Welch, Reference Welch1973; Williston, Reference Williston1971). From the outset, the group home model was communicated through advocacy channels to governments through inherently contradictory logics of inclusiveness and short-term cost-saving.

According to interview respondents, the estimated wait time to get into a group home can be up to 20 years, making it difficult to refuse placement, even if the fit is poor. In their early development, group homes were designed to abandon institutional characteristics, most notably the reliance on large scale congregate housing. This was evident in the interprovincial “Challenges and Opportunities” report, which outlined the use of “minimum separation distances” between group homes, and a maximum number of persons in group homes per zoning area (IWGGH, 1978). These policy recommendations attempted to mitigate anticipated public backlash against group homes by spreading the locations out and giving oppositional municipalities the freedom to determine their own bylaws (Association of Municipalities of Ontario, 1981). Because large residential institutions had been intentionally located outside of large municipalities, urban neighborhoods felt threatened by the sudden influx of disabled people migrating in (Dear and Wolch, Reference Dear and Wolch1987).

The development of group homes was stalled in Winnipeg, Ottawa, Toronto, Edmonton and Vancouver, where citizens invoked not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) sentiments to stall and prevent implementation (Finkler & Grant, Reference Finkler and Grant2011). Throughout the 1980s in Ontario, both concerned citizens and elected officials protested the proposed development of group homes, with some suggesting they posed a safety risk to communities (O’Mara, Reference O’Mara1982; Finkler & Grant, Reference Finkler and Grant2011). NIMBYism still pervades the discourse around group home development, including in Ontario where current Premier Doug Ford made public comments about how a group home “ruined” a communityFootnote 6 . This sentiment also abounds in communities with group homes where, as the quote below demonstrates, there remain attitudinal barriers to social inclusion:

You’re in a community. You’re in a neighbourhood. But there’s not much interaction with your neighbours or with other community members. It ends up just being a small thing that still feels somewhat institutional.

(Ontario Group Home Manager)

Despite inclusion policies, reports of abuse and segregation, and restrictions on autonomy persist in group homes. Shrinking the social universe of people labelled with IDD is fundamental to the politics of exclusion because with less interaction comes less engagement and visibility. This is potentially dangerous, as developmental services agencies can utilize restrictive interventions including overmedication, physical restraints, and seclusion without accountability (Spagnuolo, Reference Spagnuolo2016). While congregate settings can be beneficial, autonomous, and supportive when they are among a range of residential options, they become institutional when residents’ freedom of choice is removed.

In group homes, developmental service workers are tasked with observing, recording, and reporting behaviours they may deem as problematic into individual plans (Spivakosvky, Reference Spivakovsky2017). Group home residents have signified that this level of surveillance interferes with their ability to maintain social ties and engage in intimate relationships (Chin, Reference Chin2018). Interview respondents also pointed to the use of electronic surveillance devices such as cameras and motion detectors to impose similar limitations on the freedom and autonomy of group home residents. Taken together, these practices of surveillance, restraints, segregation, and isolation are all legible within the ableist logic of exclusion that haunts contemporary IDD housing policy.

Ghosts of Elimination: Eugenics Policies in Canada

In the early era of Canadian IDD policy, ableism was explicit in policy design, most notably in eugenics policies such as Alberta’s Sexual Sterilization Act, 1928. Based on false assumptions about the heritability of IDD, this act elaborated processes of forced surgical sterilization for inmates of residential institutions to eliminate what section 5 of the act calls the “attendant risk of multiplication of the evil by transmission of the disability to progeny”Footnote 7 . When implemented at Alberta’s Michener Centre, the policy was interpreted such that any inmate with an IQ lower than 70 could be subjected to forced sterilization (Malacrida, Reference Malacrida2015: 29). Eugenics policies underscore the biomedical framing of IDD as disease/pathology, and the corresponding intention to separate and eliminate IDD from society. This framing was also used to deny people with IDD the right to marry, as with Saskatchewan’s 1933 amendment to Section 55 of its Marriage Act to forbid marriage for people designated as “imbeciles” or “idiots” (Dyck and Deighton, Reference Dyck and Deighton2017: 18). The prevalence of this framing during Canada’s first century both legitimized ableism and embedded the logic of elimination within Canada’s social and political institutions.

At the dawn of the 20th century, institutions and those who were confined within them would transform and evolve to meet the needs of capitalist political economies. As a site of elimination, institutions served to remove those who were labelled as dangerous or a burden on the state. People labelled as “feeble-minded,” were deemed incurable and forced into lifetimes of confinement. This was plainly evident in Alberta, where shortly after the Sexual Sterilization Act, 1928, the province amended the Mental Defective Act in 1933 to make sterilization a condition of release from residential institutions for individuals who proved they were both capable of earning income and abiding by the law (Harris, Reference Harris2010: 52). Similarly, eugenic policies in other provinces maintained this logic in other forms. In Ontario, the desire to cull the population of people labelled with IDD is evident in this passage from the government-commissioned Williston Report, which states that men and women labelled with IDD were segregated even during burial: “(s)o keen were the officials that there be no possibility of sex or propagation by these deviants that upon death men and women were sometimes buried in separate burial grounds” (Reference Williston1971: 24).

Transcripts from class action lawsuits and inquests into the deaths of people labelled with intellectual disabilities, archival documents, and interviews with survivors, are all replete with stories of elimination—of friends, roommates, and fellow inmates, disabled people who died by suicide in the institution, or sometimes years after escaping, haunted by their experiences inside (Linton, Reference Linton2024: 252). At critical junctures, these suicides were a catalyst for policy change, resulting in government commissions and inquiries into their deaths. The Williston Inquest in 1971 followed the suicide of Elijah Sanderson at an Ontario institution, just as the Jobin Inquest followed the death of 14-year-old Stephanie Jobin, an autistic teen who was suffocated by four adults restraining her. However, over time cultural acceptance of this normalized violence renders invisible these institutions and the disabled people confined within them. Neoliberal governance makes visible only the disabled people who are capacitated enough to become productive neoliberal subjects (Fritsch, Reference Fritsch2015b). This disappearance of disabled lives is made possible by the impenetrable walls of the institution, as Pietropaolo explains “(t)he more out of sight they were, the less one had to carry the weight of thinking about them” (2010: 14). Disappearance has its benefits—both for the state which avoids accountability for its role in facilitating elimination and for society at large, which is freed from knowledge of these injustices.

Policies of explicit elimination in Canadian IDD policy were eventually abandoned as the medical and disability sectors drew parallels to the violent forms of elimination catalyzed in the Nazi mass murder program, which targeted hundreds of thousands of institutionalized disabled people who “threatened the health and purity of the German race” (Evans, Reference Evans2004: 15; McLaren, Reference McLaren1990). But despite attempts to distance from the rhetoric of explicit eugenics, institutions are fundamentally interlocked with this ideology (Ben-Moshe, Reference Ben-Moshe2020), as is evident in contemporary care practices for people with IDD, who are infantilized, isolated, and discouraged from exploring sexual intimacy by support workers (Santinele Martino, Reference Santinele Martino2022). Thus, while forced sterilization is no longer practiced within the developmental services sector, the logic of elimination is still reflected in implicit forms of population suppression.

Medical Assistance in Dying

In addition to these implicit manifestations, the logic of elimination is also reflected in policies that disproportionately affect people requiring the most resource-intensive supports. Within the public administration literature, this process of limiting the implementation of new policies to clients who are the easiest to support is known as creaming (Döring & Jilke, Reference Döring and Jilke2023). The tendency towards creaming explains why there is a double movement in IDD housing policy—on the one hand promoting inclusive models (for example home care, shared housing, and semi-independent living models) for easy to accommodate service users, while on the other re-institutionalizing people whose needs are likely to place greater strain on resource allotments. Creaming is most likely where resources are spread thinly, and people most disadvantaged by the process are rendered invisible. The politics of austerity in the developmental services system facilitate resource scarcity conditions, but disability advocates are even more concerned about new forms of invisibilization that return IDD politics to the era of elimination.

The enactment of Bill C-7, Canada’s medical assistance in dying (MAiD) legislation and its subsequent reforms, have made advocates call into question the government’s commitment to disability inclusion. The bill qualifies people with disabilities as the only group that is eligible for assistance in dying, even when death is not imminent. In response, Canadian disability advocacy groups rallied together to protest the extension of MAiD to people with disabilities who are not facing death, arguing that the policy is being offered in lieu of basic disability supports and services.Footnote 8 Several publicized cases explicitly connect lack of access to affordable housing as the catalyst for applying for and accessing MAiDFootnote 9 ,Footnote 10 ,Footnote 11 . This is especially dubious because disabled people who are most likely to apply for MAiD are also more likely to require the most resource-intensive supports and/or to be currently unsupported, thus doubly incentivizing MAiD as an alternative for austere governments.

For the advocates we interviewed, this bill was symbolic of a fundamental devaluation of disabled lives:

I don’t know how the federal government can talk about a policy of inclusion in the face of Bill C-7. I just, I don’t know what to do with it. (National IDD advocate)

Coupled with an awareness of the deleterious effects of recent austerity measures on the developmental services sector, IDD advocates shared the common sentiment that Bill C-7 is evidence that the government would rather people with disabilities die than provide them with necessary supports. This sentiment is supported by early evidence, as 4.3 per cent of MAiD recipients reported that they required disability supports that were not received in 2021Footnote 12 . MAiD confers disadvantage and death to disabled people at the far margins, echoing eugenics policies of the past in the designation of non-productive bodies (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2015: 214-216). This is emblematic of the ableist ideas that continue to pervade Canada’s social and political institutions—enduring barriers from a time when the logic of elimination was more explicit.

Ghosts of Extraction: Current Approaches to IDD Housing Policy

Providing housing for people labelled with IDD involves significant budgetary resources. In Ontario alone, annual services allocations for people labelled with IDD hover between $2-3 billionFootnote 13 . The logic of extraction supports policies and processes where the needs of labelled people are commodified and outsourced to for-profit companies, privileging the idea that labour is the sole contribution we make to society. Extraction can be practiced on people considered to have “resource-intensive needs” and unable to be included the labour market. This is legible in the LTC system, where disabled people are worth more to the GDP in an institutional bed than in their own bed (Russell, Reference Russell1998: 213). Private LTC homes can draw profit from their residents, whose bodies are transformed into raw commodities, where needs for food, care, and cleanliness are contracted out to staffing agencies, conglomerates, and transnational corporations.

The logic of extraction is tied to deinstitutionalization, as rationales of austerity and cost-reduction help legitimize the presence of this logic within the Canadian social policy agenda. Widely recognized from their outset as financially inefficient, large-scale residential institutions have been consistently austere, relying on the labour of residents for their maintenance (Burghardt, Reference Burghardt2018). As public attention to the deaths and abuse at institutions grew, government officials ran cost-benefit analyses on the economic and political impacts of deinstitutionalization (Williston, Reference Williston1971). Early policy documents and government recommendations point to LTC facilities as an opportune solution for higher needs residents.

In this same vein, contemporary solutions to the lack of available community living alternatives involve moving people with IDD outside of the developmental services system, thus shifting the onus onto social housing and health systems. A pertinent recent example of extraction is Ontario’s More Beds Better Care Act, 2022, where hospitalized people who are deemed ready for discharge but require alternative levels of care (ALC)—like support dressing, eating, or bathing—are to be transferred to a LTC facility, or be charged $400/day for their hospital bed.Footnote 14 People labelled with IDD, particularly those with psychiatric diagnoses, are at greater risk for an ALC designation, given the extensive waitlists for community supports (Selick et al., Reference Selick, Morris, Volpe and Lunsky2023). Group homes are intended to remedy this solution, but their extensive waitlists can position LTC as the sole alternative. As of December 2023, Ontario’s waitlist for placement in developmental services supported living was 28,128 people as compared to only 17,856 receiving services (Ontario 2024, 20). In response to these massive gaps between demand and supply, provinces are looking outside of the developmental services sector to provide IDD housing.

Dangers of Long-Term Care

A form of both health and social care, the passage of the Canada Health Act, 1984 excluded LTC, homecare, and long-term disability supports, permitting widescale privatization of these services (Armstrong and Armstrong, Reference Armstrong and Armstrong2020). Simultaneously, as large-scale institutions began planning for closure, they identified LTC facilities to house older residents and people with more complex needs. There has been a recent increase in the inappropriate placement of younger people with IDD into LTC, which has been described as a process of “re-institutionalization” by scholars and IDD advocates (Ouellette-Kuntz et al., Reference Ouellette-Kuntz, Martin and McKenzie2017; Barber et al., Reference Barber, Weeks, Spassiani and Meisner2021; Linton, Reference Linton, Rinaldi and Rossiter2023). As of 2020, Statistics Canada reported that there were 12,755 Canadians under the age of 65 in LTCFootnote 15 . While it is difficult to ascertain what percentage of the Canada-wide numbers are people with IDD, a recent report by Ontario’s Auditor General identifies a 162 per cent increase in the number of autistic residents in LTC over the past decade (OAGO, 2023: 38).

Additionally, recent high-profile cases have pointed to the significance of re-institutionalization cross-provincially. One such example is the case of Vicky Levack, a Nova Scotia woman with cerebral palsy who, after 10 years of intense advocacy culminating in a lawsuit against the province, was able to move out of the nursing home she had been placed in inappropriatelyFootnote 16 . The re-institutionalization of younger adults labelled with IDD is a harbinger of severe deficits in capacity within the Canadian IDD housing policy system, resulting in a failure to provide age-appropriate care (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Weeks, Spassiani and Meisner2021). These deficits are reflected by evidence of growing waitlists for housing placement amongst the few Canadian provinces who disclose this data (Dickson, Reference Dickson2023: 122). For younger adults, who at the age of 18 graduate to adult care services, the prospect of toiling on the waitlists or being inappropriately placed in LTC demonstrates the negative momentum of inclusive housing models.

The developmental services system equally remains marked by pronounced biases against older adults with IDD. For example, recent changes to improve quality measures in residential supports in Ontario are geared only to children and young persons in licensed residential settings, making ageist bias explicit in the very design of the policy (Ontario 2022). These ageist biases have been further exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several interview participants described the onset of social isolation following the closure of day programming for older adults during the pandemic. They also described the anxiety and fear that resulted from outbreaks throughout the housing sector, with a greater likelihood of fatality for older people with IDD who contracted COVID-19 compared to their peers (see Lunsky et al., Reference Lunsky, Andrew Jahoda, Campanella and Havercamp2022). Finally, they pointed to a trend of increased re-institutionalization—a fate that must be particularly devastating for institutional survivors:

And it’s a whole re-institutionalization. So, sometimes we’re seeing people who were institutionalized when they were younger, and with the move towards deinstitutionalization they’re out there in the community. And now that they’re older and their needs are changing, we don’t know what to do with them and are placing them back in institutions. And so, I’ve seen that happen to a number of people and it’s just such a depressing way for them to spend their final years. (Ontario IDD advocate)

In addition to capturing the potential traumas of re-institutionalization, the above quotation also reveals how developmental services structures continue to be unprepared to support older adults with IDD. The current cohort of older adults with IDD contains a generation for whom residential institutions were the most dominant model of IDD housing when they entered adulthood. For this reason, the re-institutionalization of survivors of residential institutions both demonstrates regress in the IDD housing sector and is evidence of the haunting policy legacy of systemic ableism. Many LTC facilities are residential institutions, designed to accommodate people with complex support needs who require 24-hour support. Over the last 60 years, LTC facilities have been used to institutionalize people labelled with IDD who require more support (Ouellette-Kuntz et al., Reference Ouellette-Kuntz, Martin and McKenzie2017), often as a last resort when there are no other possibilities.

Overseen by provincial ministries, and delivered by private and public operators, the 2,076 LTC facilities across Canada accommodate 198,220 peopleFootnote 15 . Over the past ten years, provinces have made significant investments in the number of LTC beds and facilities to accommodate the growing aging population (Marier, Reference Marier2021). Conversely, the civil servants and advocates interviewed reported that over the same period investments in community living services through provincial developmental services have maintained a low rate of growth.

The deficiencies of the LTC model were laid bare during the COVID-19 pandemic, when 81per cent of all COVID-19 fatalities in Canada occurred in LTC facilities (Akhtar-Danesh et al., Reference Akhtar-Danesh, Baumann, Crea-Arsenio and Antonipillai2022). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional barriers for people with IDD (Lunsky et al., Reference Lunsky, Andrew Jahoda, Campanella and Havercamp2022), highlighting the dangers of housing people with IDD in isolative and exclusionary congregate living facilities (Landes et al., Reference Landes, Turk, Formica, McDonald and Stevens2020; Hansford et al., Reference Hansford, Ouellette-Kuntz and Martin2022). Infection prevention and control strategies in LTC facilities increased experiences of isolation for people with disabilities, as caregivers, family and friends were prohibited or limited from entering LTC facilities (Landes et al., Reference Landes, Turk and Wong2021). Access to caregivers, visitors, and family for LTC residents are essential to interrupting cycles of abuse, resulting in substantial health and safety outcomes.

LTC facilities are not designed for people labelled with IDD. They lack access to recreation, relevant health and social supports, and community engagement. However, despite the increased reliance on LTC to fill the gaps in IDD housing policy, there is evidence that governments are aware this is unsustainable. The Ministry of Community, Children and Social Services in Ontario responded to the use of LTC facilities for people labelled with IDD by developing “Long-Term Care Home Access Protocol for Adults with a Developmental Disability”Footnote 17 . Although guidelines do not address the potential for trans- and re-institutionalization, they nonetheless acknowledge that autonomy and appropriateness of fit are key criteria for LTC placement. However, given the economic incentive to favour LTC over community-based models, there is a risk that re-institutionalization will continuously increase.

Conclusion

Systemic ableism continues to haunt Canadian IDD housing policies. While this policy legacy continues to manifest in the logics of exclusion and elimination, the key informants we spoke to focused most on the logic of extraction. Unlike the other two logics, the logic of extraction is less “ghostly,” and is more often made explicit in the policy and scholarly discourse. We point to the re-institutionalization of people with IDD as evidence of this explicit logic of extraction, but examples can also be drawn from disability employment policies, which similarly privilege the commodification of disabled bodies over the inclusion of disabled people, as with the sheltered workshop model (see Galer, Reference Galer2018). In our interviews, senior civil servants and representatives from disability advocacy groups frequently emphasized that in the austere developmental services sector, proposals for increasing social inclusion must be both cost-effective and produce quick, deliverable outcomes. As such, the logic of extraction explicitly limits the potential of inclusion policies, which is ironic considering the shift towards extractive politics has coincided with the ascent to the agenda of policy designs that rhetorically commit to the promotion of social inclusion for people with IDD.

The politics of extraction originates with policy commitments towards deinstitutionalization and the promotion of community living alternatives. These rhetorical commitments within provincial level policies—such as Nova Scotia’s de-institutionalization plan (Nova Scotia, 2013)—commit to the removal of ableist barriers in IDD housing policy but are not matched with actionable methods of implementation. Ahmed examines these mechanisms as forms of “institutional commitment,” which she defines as a subset of the “non-performative” ways that (social and political) institutions behave. Using the example of racial equality policies within the institutional environment of the university, she points to how non-performatives are designed precisely not to achieve the effect that they name (Reference Ahmed2012: 116-121). Drawing directly from Ahmed, Mitchell (Reference Mitchell2015) critiques the phenomenon of “inclusionism” in disability policy as a non-performative form of institutional commitment, where mechanisms of integration—that favour disabled people who are most able to meet the performative expectations of an ableist society—produce a weak form of inclusion that more forcefully excludes and further renders invisible all other disabled people. Mitchell argues that this is particularly true of weak accommodation policies which ignore the diversity of disability embodiment and tend to privilege types of disability that are easiest to accommodate (Reference Brown and Radford2015: 36). The phenomenon of inclusionism has constrained the potential for genuine reform in the IDD housing sector. While transformative models have emerged, these are often very small in scale and offered to people who require the most minimal support.

The creaming of social services provision to exclude those with the greatest support needs is just one effect of inclusionism. Equally, the rhetorical commitment to inclusion in policy documents such as the Accessible Canada Act, 2019 creates a false sense of progress. Indeed, while progressive in language, the newest wave of IDD policies has taken the form of framework legislation, where the benchmarks for implementation are unarticulated by the policies themselves. This significantly stalls the implementation process, as is evidenced by the standards developed following the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act 2005 (AODA), which have fallen far short of the legislation’s progressive language on the promotion of inclusion, especially for people with IDD (Onley, Reference Onley2019). In a similar vein, the Canada Disability Benefit, which was introduced in the 2024 federal budget following the passage of Bill C-22 to reduce poverty among people with disabilities, has fallen far short of even the most conservative scenarios for both coverage and generosity set forth by the Parliamentary Budget OfficerFootnote 18 . Over and over, disability policy instruments fall far short of the aspirational commitments to inclusion made by policymakers during policy design processes.

Overcoming these discursive barriers requires disrupting the ideational foundations of systemic ableism, but the literature on policy legacies paints a rather pessimistic vision of policy change against deeply embedded ideas (Pierson, Reference Pierson2004; Béland and Cox, Reference Béland and Cox2010). Indeed, the interviews with senior civil servants and policy advocates in Canada align with this vision, suggesting that existing political institutional avenues limit the potential for disrupting the logic of systemic ableism in IDD housing policy. However, focusing only on the policy legacy as an insurmountable, systemic bias ignores the potential for paradigmatic shifts in public policy.

Engaging with haunting allows for a complication of our understanding of legacies. Most importantly, it allows for actionable strategies for advocates to disrupt the legacy of systemic biases by disrupting their implicit logic. While the present contribution focuses specifically on developmental services as the primary form of IDD housing policy, future research should explore the ways systemic ableism—alongside other embedded biases—equally haunts other forms of housing policy in Canada. This agenda can potentially disrupt the pervasive and pernicious biases that continue limit the potential for equal outcomes across Canadian society.

For example, the logic of exclusion resonates with experiences of social isolation experienced by older adults in Canada, for whom increasing housing instability is limiting their potential to age in place (Grenier et al., Reference Grenier, Equity Burke, Watson and Ward2022). Both older adults and people labelled with IDD have been advocating for community-based housing as a preferable alternative to institutional care, but this does not sufficiently disrupt the ageist/ableist logic that privileges institutional alternatives. Reckoning with the logic of exclusion allows the discussion of supported housing alternatives to move beyond build-form and staffing ratios to focus on selecting and building inclusive communities as a part of the policy process. Pretending that housing is nothing more than a box is being haunted by a delusion. Group homes continue to isolate and restrict labelled people because these structures are haunted by a logic of exclusion which positions their residents as inferior and unworthy of belonging in their communities.

Similarly, the logic of elimination is also evident in supported housing policies for drug users, which mandate zero tolerance for drug use, despite the evidence that it increases risk of fatal overdose (Linton and Fritsch, Reference Linton and Fritsch2024). Like MAiD policies, the false protectionism of this approach to addiction creates conditions for people to die rather than funding and providing the supports they require to live. Reckoning with the logic of elimination allows us to escape the false pathologization of both drug addiction and IDD as incurable diseases or impairments, and properly situate these social phenomena within Canada’s austere social services systems, which have long privileged the elimination of groups for whom equality and inclusion necessitates the provision of resource-intensive supports.

Moreover, the logic of extraction is also applicable to the mass-incarceration of Indigenous people in Canada, which has been described as a modern form of colonial dispossession that continues prior legacies of segregation (Chartrand Reference Chartrand2019; Blackstock Reference Blackstock2007). Carceral expansion and re-institutionalization share a common commitment to prioritizing cost-effectiveness in the control of populations who pose a problem to the dominant ableist and colonialist ways of knowing privileged by the institutions of the Canadian state. Reckoning with the logic of extraction allows Canadians to situate the injustice of carceral expansion within a long lineage of policies that have sought to squeeze value from the imposition of suffering.

Reckoning with the spectral logics of systemic ableism also facilitates a more nuanced understanding of the history of IDD housing policy alongside other carceral policies. As others have argued, there is a tendency to falsely equate all carceral institutions—most commonly by labelling prisons as the new asylums (Ben Moshe Reference Ben-Moshe2017) or the new residential schools (Chartrand Reference Chartrand2019)—but this obscures and acts against the transformative potential of deinstitutionalization or decolonial movements. As Ben Moshe (Reference Ben-Moshe2017; Reference Ben-Moshe2020) asserts, deinstitutionalization is best understood as an anti-segregationist mindset, rather than a policy or process. Understood this way, one cannot claim that deinstitutionalization has failed simply by pointing to policy outcomes, such as waitlists for community-based housing or even the persistence of residential institutions. As the logics of systemic ableism continue to appear and rationalize the imposition of exclusion, elimination and extraction upon labelled people, the transformative potential of deinstitutionalization will be stifled. Exorcising the ghosts of systemic ableism requires intervening with political and policy institutions prior to the design and implementation of IDD policies.

Naming these spectral logics is useful but eliminating them requires power-ceding to IDD advocacy communities through formal mechanisms such as non-tokenistic consultation and policy co-design (see Bach, Reference Bach2017; Stainton, Reference Stainton2016; Reference Stainton2005) and through building informal linkages at the interpersonal and familial levels among those who bear the brunt of ableist structures (Werner and Scior, Reference Werner, Scior, Scior and Werner2016). Historically, the power of these linkages was evident in the successful development of the Canadian deinstitutionalization movement by family and self-advocates (Hutton et al., Reference Hutton, Peter Park, Johnson and Bramesfeld2017; Vanhala, Reference Vanhala and Smith2014). Despite the failure of this movement to permanently end institutionalization, advocacy group mobilization during this pivotal period forced Canadian governments to confront the ableism of IDD housing policies. Self-advocacy has grown significantly since then, and our interviews with advocacy groups and actors revealed a broad consensus on the foundations of systemic ableism, particularly amongst those who are the most unentangled with existing policy design and implementation structures. Therefore, to extend the metaphor of Canada’s political institutions as a haunted house, where the legacy of systemic ableism confounds policy change towards inclusive housing models, exorcising or reckoning with the spectral logics of this policy legacy requires breaking the inertia of IDD housing policy by empowering self-advocacy groups through co-design and governance arrangements that can encompass the full transformative potential of deinstitutionalization.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.