On the morning of the 8th February 1799, armed detachments of soldiers of the British East India Company broke into the homes of civilians in the French settlement of Pondicherry.Footnote 1 Pushing aside women, children, and the elderly, they seized and rounded up fifty-two men, who were thrown on board a ship just arrived from Madras, already loaded with three hundred French prisoners of war.Footnote 2 The ship then continued its journey to Portsmouth, by way of the Cape of Good Hope and St Helena.

This event was only the latest episode in a series of conflicts that had been opposing the French and the British in India since the end of the seventeenth century. With a population of perhaps sixty thousand in 1791, Pondicherry, on the Coromandel coast in southeast India, was one of the largest French possessions in Asia.Footnote 3 Established in 1673, this trading post was occupied by the Dutch from 1693–1699, and by the British from 1761–1765 and again from 1778 and 1785. During the 1790s, the British East India Company [hereafter EIC] sought to control the danger of revolution and insurrection in their newly conquered territories in the Indian Ocean, such as Dutch Ceylon and the Cape Colony.Footnote 4 In July 1793, Pondicherry was attacked and besieged by the armies of the EIC and capitulated on 23 August. The city would remain under military occupation until 1816. For a long time, few scholars of French India have looked beyond the Treaty of Paris of 1763, which was seen as marking the end of French imperial ambitions in the region.Footnote 5 The French Revolution in India and the Indian Ocean has been more intensively studied in the last decade.Footnote 6 However, the period of British occupation remains largely unexplored.Footnote 7

The sovereign of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, who cultivated friendly relationships with the French Directory, was a particular source of anxiety in Britain.Footnote 8 In 1798–1799 the fourth Carnatic War opposed Britain and Tipu, which resulted in his defeat and death in May 1799. Richard Wellesley, governor general of the British possessions in India, thus expressed his fear that the officials and employees of the EIC were seduced by the principles of the French Revolution, while “the strongest and boldest spirit of Jacobinism prevailed” among the colonists.Footnote 9 Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, and the presence of thousands of French mercenaries in the service of Indian princes, made the prospect of an alliance with Tipu all the more realistic.Footnote 10 Between 1793 and 1815, this conspiratorial thinking spread alongside British armies in the Subcontinent and in the British Empire more broadly.Footnote 11 The decision to deport alleged trouble-makers from Pondicherry should be seen in this context. In the Autumn 1798, EIC officials in India identified a plot linking French refugees in the Danish settlement of Tranquebar, Danish soldiers, emissaries from French Isle de France (Mauritius), and envoys from Tipu Sultan. The main funders and instigators of the conspiracy were Frenchmen based in Pondicherry, where five hundred Indian sepoys were also to be recruited to wage an insurrection.Footnote 12 On 3 January 1799, Robert Monckton Grant, the British captain freshly arrived and put in charge of the French city as “town major,” wrote to Captain Colin Macaulay, the secretary to the Commander-in-Chief of British India: “I shall in the course of this day endeavour to get as complete a List of the Rascals in this Place as possible, and transmit it to you for the Information of Government.”Footnote 13

In the weeks that followed, the main tool used to identify and select these men were lists, which circulated back and forth between Madras (the seat of the Presidency) and Pondicherry. Focusing on lists offers a good vantage point on concrete modes of colonial governance and knowledge, at a critical juncture in the history of European imperialism in Southeast Asia.Footnote 14 Those events were unfolding while the EIC was defeating its rivals in the region.

India under the rule of the EIC has been described as a laboratory of modernity, whether looking at imprisonment, surveillance, or identification. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s concept of biopolitics, anthropologist David Scott has highlighted the specific instantiations of colonialism, and its “effects … on the forms of life of the colonised.”Footnote 15 In the analysis of the nexus between knowledge and conquest in India, the authorship of colonial categories has been debated.Footnote 16 For some scholars, colonial knowledge was primarily produced by the colonizers.Footnote 17 Others have instead argued that the colonized often provided the conceptual apparatus which the colonizers built on. Works on imperial and colonial administration have, for example, emphasized the role played by precolonial writing practices in bureaucratic instruments.Footnote 18

Paper artefacts, like census registers and lists, say much about the mechanics and logistics of political authority.Footnote 19 “What’s in a list?” famously asked anthropologist Jack Goody. Lists are one of the most archaic instruments used by the state to govern land and people, recording births and deaths, ships, armies, and taxes, which can then be aggregated in statistics. Lists are used for addressing practical problems: they are tools for extracting, classifying, and synthetizing information, allowing for comparisons and hierarchies. Goody describes lists as “systems of storage” of information, which can be backward-looking and summative, such as inventories, or forward-looking, like shopping lists.Footnote 20 What differentiates lists from other forms of writing is the way they process information. The list “encourages the ordering of the items,” creating boundaries with the outside which make the categories more visible but also “more abstract.”Footnote 21

During the early modern period, the lists used by the Spanish Empire were “performative,” in the sense that their sole existence projected an image of control, order, and knowledge by the imperial state over territories and people.Footnote 22 STS work on lists has shown that, by formalizing uncertain data, they materialize and legitimize the political authorities that generate them.Footnote 23 Lists of suspected terrorists, for instance, have been analyzed, following Bruno Latour, as “inscription devices,” which “produce specific material, political and legal effects.”Footnote 24 Lists also coordinate activities across time and space.Footnote 25 By approaching documents as mediators, media theorists, anthropologists, and historians also suggest attending to the agents who produce, process, and use these documents, as well as to the people who are documented.Footnote 26 Focusing on signatures in twentieth-century India, anthropologist Veena Das has thus analyzed the “technologies of writing” introduced by the state as modes of government. Contradictions between legibility and “iterability,” she shows, can be a source of confusion, creating the possibility of imitation and fraud.Footnote 27 In the same way, in contemporary Pakistan, governmental lists of claimants against expropriation or the lists of the people who claimed compensation after a natural disaster are susceptible to manipulation.Footnote 28 As Martin Sökefeld puts it, “Lists do not simply document or represent a state of affairs.… Lists puts categories to action.”Footnote 29 Closer to the period of this article, and focusing on Southeast India as well, Bhavani Raman has emphasized the dynamic, processual, and iterative nature of paper documents by taking a media studies approach to the history of colonial intermediaries and scribal culture.Footnote 30 A central question raised by these studies is how, in specific contexts, bureaucrats and populations use lists for their own purposes. Technologies of writing do not reveal a panoptic state, but rather a complex social architecture riven by tensions.Footnote 31

Building on these insights, this article examines the lists of populations drawn by the EIC at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Whereas scholars studying contemporary lists often struggle, for lack of evidence, to understand the rationale behind a decision to put some people on a list and remove others from it, the 1799 case is exceptionally well-documented.Footnote 32 This article treats lists not as markers of the effectiveness of the colonial state’s grasp of the colonized, but instead as indicators of its internal contradictions as well as potential subversion by its subjects. The EIC lists embody many of the challenges—spatial, social, and intellectual—faced by imperial states in situations of emergency and war. Ruling over their distant possessions presented numerous obstacles to metropolitan authorities. But in India as in other empires, even across short distances, the gathering and transfer of information also depended on the state of the roads, the existence and effectiveness of the postal service, and the skills of paper-pushers.Footnote 33 The geopolitical and temporal situation in Pondicherry meant that the EIC had to not only contend with indigenous people but also compete with rival empires and grapple with European populations. In this context of military occupation, information also had to be gathered from other and previous colonial powers—here, the French. The features and functions of the lists were thus shaped by the circulation and adaptation of templates and categories from other empires.

By approaching the list as a media technology in the work of colonial and military officials, and by highlighting its iterative rather than fixed nature, this article offers a take on the issue of colonial governance that differs from readings of colonial archives primarily in terms of the colonizers’ “epistemic” and “administrative anxieties.”Footnote 34 Much of the paperwork gathered by the colonial state was undoubtedly “irrelevant to what state officials decided.”Footnote 35 But the lists which this article focuses on were not discounted by the colonial government. And they were not only summative of completed bureaucratic processes, but action-oriented. They were pivotal media of decision-making, at the central level in Madras, as well as at the local level in Pondicherry. The frictions between these two levels are crucial to understanding how lists operated.

Key protagonists in this story are mid-level British officers. Superficially, the captains and lieutenants put in charge of organizing the deportation appear to have been minor cogs in the colonial machine. But it was they who were placed in the central role of determining people’s fates by putting names into lists.Footnote 36 Following a pattern identified by sociologists of the state, subaltern officers were put between a rock and a hard place, enduring recriminations from both their hierarchy and the population.Footnote 37 Moreover, they were asked to perform their task without training and with instructions that were often impossible to implement without some level of discretion. The emotional impact this bureaucratic work had on these military officers-turned-list-makers cannot be overemphasized.

Conversely, local populations were not mere spectators of the process of list-making. They often resorted to “tactics” of concealment, if not to subvert the colonial state, at least to create “diversionary practices,” for example by lying about their familial status.Footnote 38 The act of listing thus encapsulates this tension between the strategies of the agents who identify, categorize, select, and trap individuals on paper, and “the tricks of the weak,” who often find creative ways to jam this process.Footnote 39

I begin with the story of a cover-up of a gigantic mess by a single army officer, who was put in charge of drafting the lists and removing allegedly dangerous Frenchmen from Pondicherry. Building on what Benedict Anderson calls the “power of the grid,” I underline the process by which categories that were above all the fruit of colonial imaginations started to gel and shape social representations.Footnote 40 But colonial categories also reveal the limitations of the capacity of the state to “make a society legible” when attempting to fix the populations’ surnames, marital relationships, or addresses.Footnote 41 The content of the 1799 lists was frequently updated and modified, as if the Company-state struggled to mirror the fluid society it was attempting to describe.Footnote 42 The second section shows the embeddedness of the list in social imaginaries. It focuses on the officer’s predicament and analyzes his deflection strategy, based on ideas of political, sexual, racial, and moral disorder that were prevalent within the EIC at the time.Footnote 43 The break-up of “mixed race” families and the reverse deportation of “European” men from India to Europe—poor white men were deported while women of color had to stay put—illustrates a gendered zoning of the British Empire.Footnote 44 This logic of containment generated intense discussions within the EIC. The third and final section analyzes lists as tools for population demarcation that support the biopolitical imperative, but also exposes its fault lines along age, heath, class, “race,” and gender.

A Bureaucratic Fiasco?

List-makers are always forced to grapple with preliminary work of reflection on category-making and the allocation of suitable units to classes.Footnote 45 And the soldiers-list-makers faced similar types of problems as the social scientists who input data in spreadsheets, reflecting on the comparability, intelligibility, and robustness of categories. Ultimately, tables and lists are modes of presentation of arguments.Footnote 46

On 1 February 1799, the Governor General in Council in Bengal, in Madras, informed the Board of Governors of the EIC that it intended “to remove from Pondicherry the whole of the French Prisoners of War, and inhabitants, who might have the means of forwarding the views of Tippoo Sultan against the British Interests.”Footnote 47 Robert Monckton Grant, captain commanding in Pondicherry, had accordingly been instructed to prepare a list of the individuals, “with such information annexed to each name as might enable the Board to select those whom it might be deemed expedient to embark on the Triton.”Footnote 48

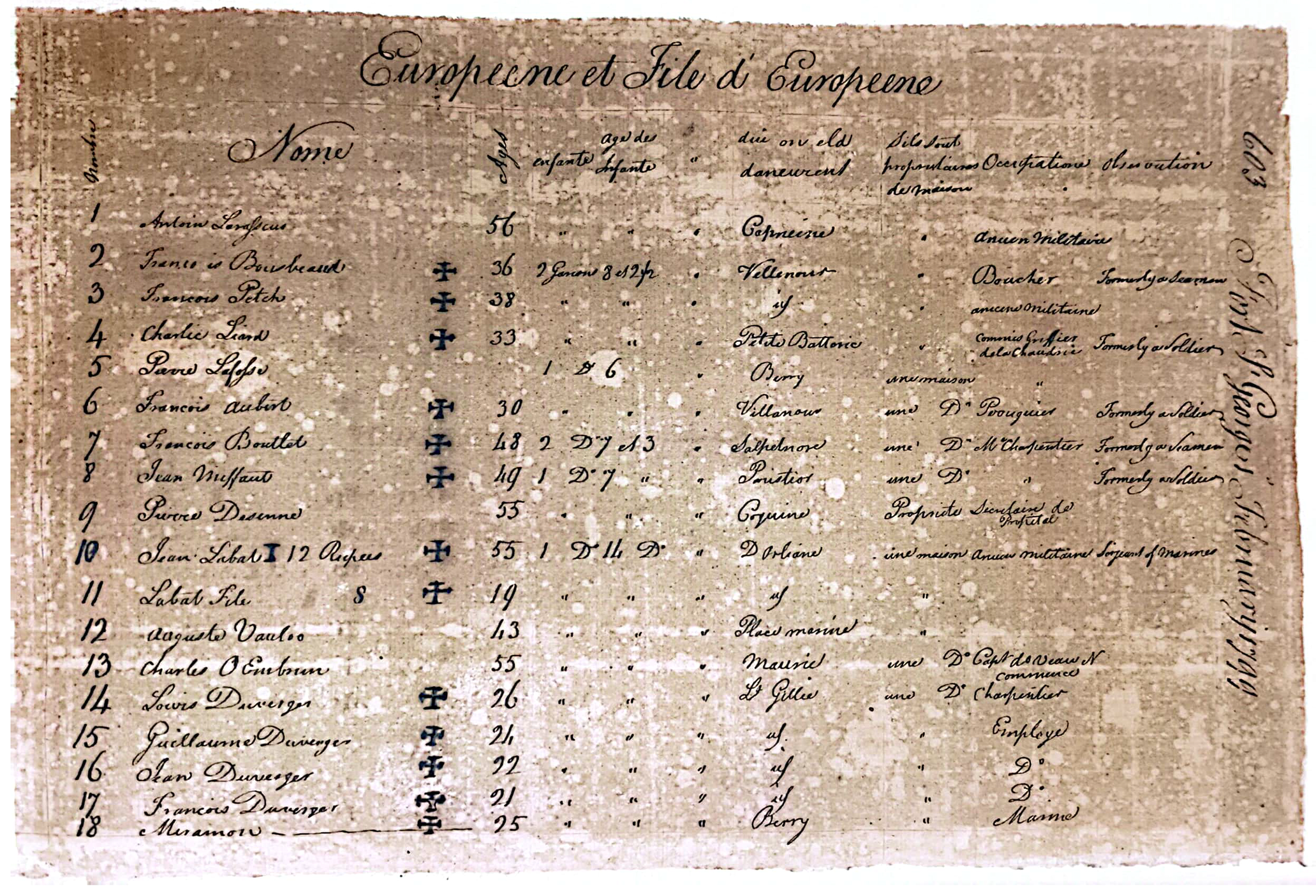

Given the context in which he was operating and given how he understood his brief, it is not very surprising that Grant “found” dangerous individuals in Pondicherry.Footnote 49 Following his orders, on 27 January 1799, Grant had sent his first list to Josiah Webbe, head of the Government Secretariat in Madras. Entitled “Europeene et File d’Europeene”—a title which makes no more sense in French than in English—it contained the names of 278 men, of whom 143 were earmarked for deportation. On eleven handwritten folios, stored today in the Tamil Nadu Archives in Chennai (Madras), were drawn neat tables, formatted in columns and numbered lines (see figure 1).Footnote 50 Although standardized printed tables became the norm by the 1820s, at least with respect to British censuses, preprinted bureaucratic lists were already in use well before this period. This type of documents illustrates the prominent role local officials played in the practical definition of categories which were aimed at addressing specific problems.Footnote 51

Figure 1. List of the inhabitants of Pondicherry drafted by Captain Robert Monckton Grant.

Source: Grant to Josiah Webbe, 27 January 1799, TNAC, Military Consultations of Fort St George, vol. 249A, f. 603.

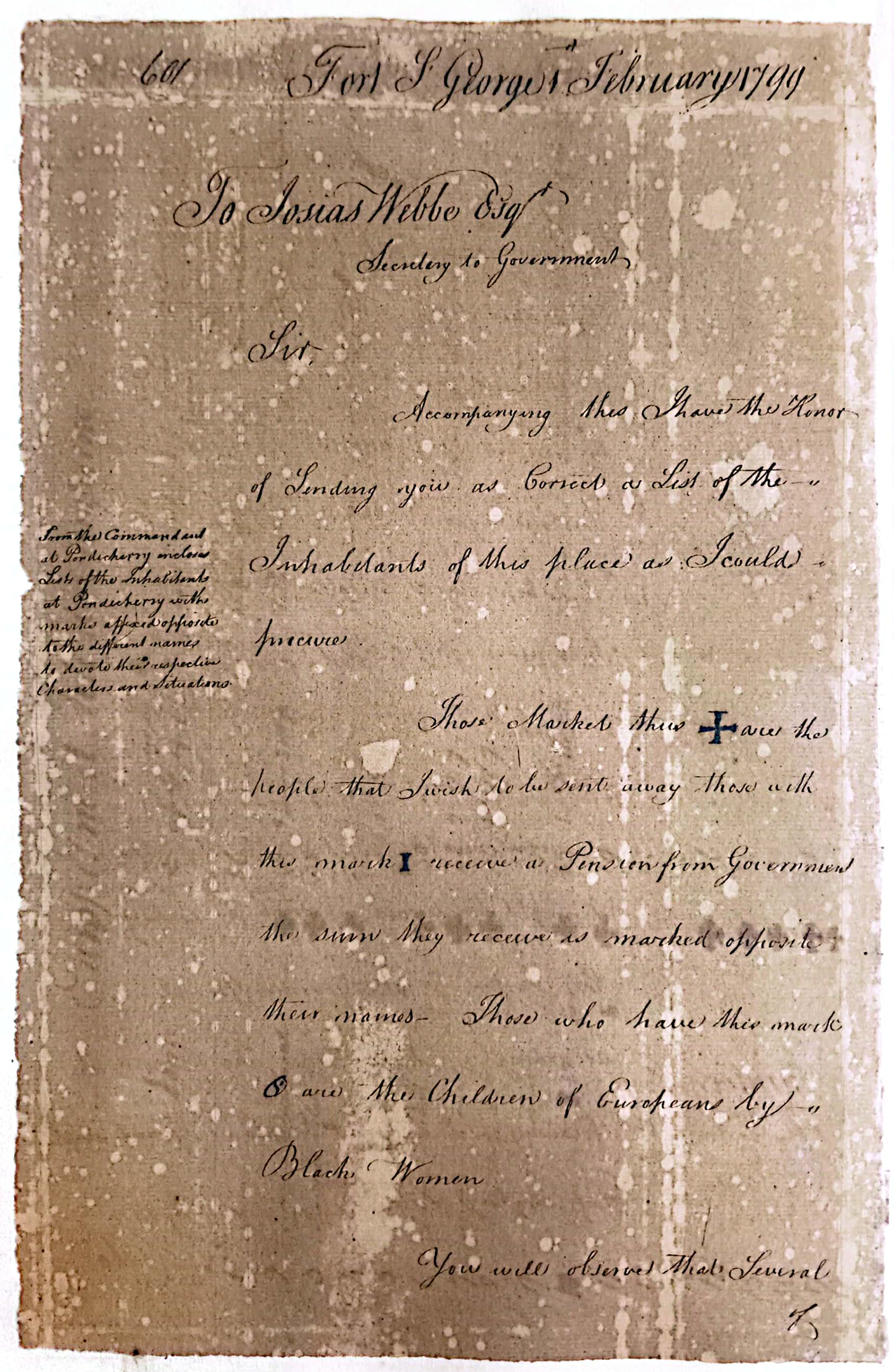

The following rubrics, in French, were differentiated: name, age, children and their age, address, whether they owned a house, occupation, and remarks. The reasoning behind the order of names is not specified. The list contained textual descriptions, mixing annotations in English and in French. For example, Theodore Gardelle (no. 128), a thirty-eight-year-old horloger (watchmaker), was described in the column “remarks,” in English, as “formerly a soldier and a very turbulent fellow.” We will return to this layering of languages, which tells us something about the conditions of production of this source. These categories did not come out of nowhere, and echoed principles that prevailed in Europe. The criterion of the domicile, in France and in Britain, helped to single out vagrants and migrants, commonly viewed as sources of disorder. Landed property was another criterion discriminating between worthy and unworthy mobile populations in the metropole: it was a key element of the English Poor Laws. Uprooting people or grounding them are two sides of the same coin. As we will see, the capacity to move reflected positions in terms of national belonging, class, gender, and race. Using symbols, Grant marked out three categories of individuals: those “people I wish to be sent away”; those who “receive a pension from Government”; and those who “are the children of Europeans by Black Women” (figure 2). Hypothetical revolutionary leanings were not mentioned at this stage.

Figure 2. Symbols used by Grant to mark out different categories of individuals.

Source: Grant to Josiah Webbe, 27 January 1799, TNAC, Military Consultations of Fort St George, vol. 249A, f. 601.

This raises numerous questions. In the first place, why did the British captain single out these categories? Perceived dangerousness had long been a reason for being put on a list. “Security lists” were not unprecedented, and inspiration from them probably came from elsewhere. Lists of suspected Jacobite agents had, for example, been compiled by the British government during and after the Jacobite uprisings, in 1715 and in 1745.Footnote 52 During the War of American Independence, the American insurgents drafted lists of persons suspected of aiding the enemy.Footnote 53 Since many of the soldiers and officers in India had also been serving in America and the Caribbean, the transfer of these technologies of paper across the British Empire was certainly plausible. During the 1790s, Pitt’s government also listed suspected United Irishmen, members of the London Corresponding Society, and other “Republicans” in Britain and Ireland.Footnote 54 This was not a specifically British practice either. From 1793, the French Terror created committees of surveillance subordinated to committees of general safety, which produced infamous “lists of suspects.”

Where did Grant get his information from? Since he had only just arrived in Pondicherry, how did he even know who had to go on the list? How did he know who was “mixed-race”? From the outset, and perhaps because he felt he was not on stable ground, the British captain justified his selections: “You will observe that Several of those who are marked to be sent away have large families who will consequently be left in great Distress yet I thought it my duty to put their names down being informed that they are men in which I cannot place any dependence should an Enemy enter the Country.”Footnote 55

Already at this early stage in the process appears a tension between the humanitarian duty to protect the families and the need to guarantee the security of the colony. After receiving Grant’s list, the Governor General updated the initial list along the same two principles. On the one hand, a concern for “Public Safety” may “deem the Entire Embarkation of all the Suspected persons from Pondicherry”; on the other, in some cases “the Unhappy Situation of the families of the persons described as dangerous” might support making an exception. A second iteration of the list was thus composed in Madras, which included “all the obnoxious persons … except all those, who appear to have families.”Footnote 56 It was sent to Captain Grant on 2 February 1799: from 143 in the first list, the number of the deportees was cut down to ninety-four.Footnote 57

These lists, in their very content, form, and use, reflected the context of global war and rife conspiracy theories which characterized this period. The extensive administrative correspondence of the EIC around these documents offers ways to analyze the intellectual and material reasons behind its internal dissensions. The lists served multiple purposes. While they were helping the government of the EIC to make political decisions, they were also instruments of justification, which would keep track of decisions long after the facts. The originals of the lists were archived in Chennai, while copies were bound and kept in London: at this point, they no longer informed decision-making. One of the problems faced by the Company when it tried to use these lists to inform the selection of deportees was the question of whether they were deductive or inductive forms of data: did the information gathered there validate preexisting categories and principles—for instance about the so-called character of these people—or were decisions to be induced from the lists, regardless of political background? To use Jack Goody’s definitions, were they backward-looking or forward-looking?

The list sent to Grant from Madras was accompanied by the Governor’s instructions to ruthlessly enforce his orders. In a language downplaying the cruelty of the measure, Josiah Webbe thus conceded that one should expect “some reluctance on the Part of these persons,” but he was confident that “no Serious Opposition will be made by them.” In any case, Madras trusted that since “none of the persons who have families are included in the present list,” no more exceptions should be made.Footnote 58 The family situation of the suspects had thus been paramount in determining whether they should be deported or not. However, Grant decided to further trim this second list, according to an entirely different logic: “In the List which I have had the Honor to receive from you this Morning there are about twenty six Half Cast Men Marked down in it to be embarked on the Triton.—The greater part of these are very black indeed, and I imagine it is not the intention of Government to send such people to Europe.”Footnote 59

For Grant, that these men were “half cast”—a derogative term that would become omnipresent among British colonial administrators in the nineteenth century—and that they mostly had dark skin, superseded other criteria. Furthermore, he alluded to the Company’s policy to control and restrict the immigration of such people to Britain.Footnote 60 He thus wished to withdraw these individuals from the list, while eleven unfortunate “Europeans very indifferent Subjects” were to take their place.Footnote 61 The third and final version of the list was thus a compromise, bringing together men who had been selected at different moments, on the basis of various criteria (character, place of origin, familial status, class, and phenotype).Footnote 62 At this point, the list was reified, and presented as coherent.

On 8 February 1799, fifty-two French inhabitants were put aboard the Triton. The following day, the British captain sent the list of these men to Madras. He explained that he had exempted three groups: “either Natives, Fathers of large families, or so extremely ill as to be unable to embark.” The only ones left on the ship, he insisted, were “those Characters from whom most was to be apprehended.”Footnote 63 But what did he mean by “large families”? This would become a major problem in the days and weeks that followed.

On 14 February 1799, the Board congratulated Grant for his expedition in accomplishing “this unpleasant duty.”Footnote 64 To complete the process, the captain was asked to write a report on the destitute families who would be granted support because of the deportation of their husbands and fathers. He accordingly sent a list of the twenty-one “fathers and heads of the families embarked on the Triton.”Footnote 65 Louis Blanchette, an assistant surgeon, had left behind a mother, “aged and depending on him for support.” Prudent Boutroux, a pensioned former prisoner of war, left a wife and two children. François de Brande had one child and a pregnant wife. Theodore Gardelle had a wife, one child, and “Sisters and children depending on him alone for subsistence.” Louis Pierre Ferray had a “Wife & many Children.” Pierre Morpin had “Six children entirely destitute.” And so on. Grant clearly did not realize how damning the list was for him, merely observing: “I find that these families are in the deepest misery, and bear fair Characters.”Footnote 66 Grant sent a more extensive list to the Board on 17 February: it now appeared that twenty-six of the deportees had left family in Pondicherry. For seven of them, in addition to wives and children, there was “an aged mother left without support.” He noted matter-of-factly at the bottom of that document: “It is probable that a few other names may hereafter appear that may desire the consideration of Government.”Footnote 67 By that point, the Triton was 1,000 kilometers away from Pondicherry, and about to sail past the Maldives.Footnote 68 Back in India, the controversy was only beginning to heat up.

It only took three days for Josiah Webbe to reply, by express letter; he did not mince his words. Conveying “the grief and astonishment” of the Governor, Webbe accused Grant of committing a “fatal error” with “disastrous” effects. The actions of the Company in Madras had been guided by the dual considerations of patriotism and humanitarianism, carefully balancing the protection of those in “real distress” with “the national character.” All these efforts had been nullified by Grant’s rashness: “half of the whole number embarked on the Triton appear at this late moment (when it is impossible to correct the unhappy error) to have been heads of families.”Footnote 69 Grant would have to take the blame publicly. He was to “inform the inhabitants of Pondicherry that the Government had not intended to separate any father of a family from his Wife and Children.”Footnote 70 This reads as a comment about social norms: the importance of the families to order. But the economic burden of having to support destitute families who stayed behind might also have played a part in this thinking. Consequently, the Governor General chose to mitigate Grant’s mistake by canceling it. The captain was to inform the inhabitants that orders would be sent to the Cape of Good Hope to return all the fathers put on the Triton, while their families would be cared for. Grant’s sloppy work and incapacity to transmit accurate information was to blame for this disaster. His “own Errors” had led to the transmission of an “incorrect list” to his superiors. The Company’s subsequent orders had been founded upon “that erroneous information.”Footnote 71

Let us pause briefly here. This “minor” incident tells us something bigger about the state’s capacity to collect information and process, interpret, and act upon it. The problem for states is not so much to collect accurate information than to cross-reference it.Footnote 72 An efficient bureaucracy relies on the coordination of multiple actors. When sources of information contradict each other, procedures of arbitration are needed. This was not the case in India, and even less so when time was scarce. Grant’s final update of the list did not aim to change the course of this decision; it only served a purpose of self-justification.

Grant was sanctioned and removed from his command at Pondicherry.Footnote 73 Lieutenant Bose, the most senior officer left, replaced him. After such a debacle, the distraught commandant tried to explain himself.

The Deflection Strategy

Grant first underscored the material conditions of information-gathering, which left him exposed to manipulations. He also drew on a set of French and British anti-revolutionary discourses, characteristic of a region of imperial entanglement. Finally, he argued that racial hybridity was a major threat to the British Empire in India.

The first stage in Grant’s enterprise of self-rehabilitation was to demean others. He had previously praised the support he had received from royalist French officers, like the Chevalier de Courson, who had supervised the embarkation of the deportees and “facilitated … the collection, distribution, and other detail regarding these people.” His second in command, lieutenant Bose, had also been of considerable assistance, thanks to his understanding of the French language.Footnote 74 Grant now attempted to shift the blame onto his predecessor in Pondicherry. It was indeed Major Tolfrey who had transmitted to him a recently drafted “General list of Inhabitants”: “Stranger as I was here at that moment I consulted those who I thought best qualified to afford me the truest information on the Subject, and they agreed that it really was a true Statement of the numbers of the Inhabitants, at least so far as their knowledge of such a Class as was therein included, extended.”Footnote 75

This was probably a reference to the 1796 “recensement des habitants de Pondichéry,” which had been “made by the English authorities,” and “only included Europeans and descendants of Europeans.”Footnote 76 Grant might have used it to build his first list, of 27 February 1799, which would explain its quirky title: “Europeenne et file à Europeene” reads like a transcription from the French by someone whose knowledge of that language was limited. Other French administrative documents used the same expression. Thus, a list established in 1790 by a relief distribution committee included the names of “the Europeans and descendants of Europeans”—or more specifically, the names of men and single women.Footnote 77 The same terms were also used in the Pondicherry births, marriages, and death registers of the same period: “Actes de Mariage des Européens et de Fils d’Européens” [Wedding certificates of Europeans and sons of Europeans]. While this might indicate that these French documents were one source of information for the British lists, there are significant differences in the categories used in 1796 and in 1799. The 1796 census stated the name of the householder and, when it was a man, whether he had a wife and the number of their children. Single women or single mothers were also listed individually, together with their “servants and slaves.” Finally, while they were not identified individually in the census, the “Recapitulation” at the end of the census counted distinctly “Europeans their wives and children,” “Métis their wives and children,” “Topas their wives and children,” and “domestics and slaves.”

By contrast, Grant’s 1799 list did not systematically indicate the age or gender of the children and did not mention servants or slaves. It only contained 278 names, all men. And it individually marked out twenty-three of them, “the Children of Europeans, by Black Women.” Although some of the names in his list were not in the 1796 census, this earlier document might have been one of the templates that Grant relied on in 1799. The borrowing and re-use of preexisting data by new administrations, especially in newly conquered territories or situations of transition of sovereignty, was common to all empires.Footnote 78 The mention of property-ownership might be explained by the concern that the wealthier people were, the less reliant on British support they would be. The age and gender of children addressed other preoccupations: younger children would be more difficult to evacuate, and they might be put to work appropriate to their gender.

Besides his predecessors, Grant also blamed local populations. Gathering reliable data by way of interviewing people was arduous: “It has appeared and that mostly since the embarkation that these people highly displeased at the order for giving in their Names, families &c &c., proved very insincere, for several of them, whose families have since come forward with Claims were not so set down on that list.”Footnote 79 Assuming him truthful here, none of this is surprising. In the eighteenth century, populations were notoriously reluctant to give officials this type of information. In 1716, when general G. A. Hébert, the then governor of Pondicherry, tried to make a recensement of the local population, he faced opposition: “These people who are alarmed by very little, having got it into their heads that there were hidden agendas in this research that could be detrimental to them later on.”Footnote 80 British attempts to conduct censuses provoked similar reactions in the nineteenth century.Footnote 81 This was not a colonial specificity. In Britain, when the 1753 bill for a general census was brought before parliament, the project was defeated, on the grounds that numbering people would attract divine anger, and that it was an assault against traditional English liberties.Footnote 82 Casual obfuscation and avoidance were common whenever state officials tried to obtain information that could be used for taxation purposes.Footnote 83 The imperfect design and standardization of the questionnaires, and the surveyors’ lack of technical expertise, also meant that population statistics were often inaccurate.Footnote 84

This colonial context, in an occupied city, added a further layer of difficulty to the surveyors’ work: Grant, and presumably his predecessor, had no experience doing this.Footnote 85 He was dealt a bad hand from the start, because his orders were inapplicable as such and had to be adjusted on the ground. The soldier-amateur-list-maker faced foreign and enemy populations who had good reasons to be less than forthcoming in their exchanges with him. So Grant emphasized the travails of the conqueror. The poor English commanding officer had faced “nothing but hatred and disobedience,” which made it impossible for him “to discover in so short a time the real truth.”Footnote 86

With this statement, Grant was raising fundamental epistemological issues. How does a colonial authority assess “the real truth” about populations, in a situation of domination? When making political decisions, what is the acceptable threshold between truth and falsehood? If a procedure follows the rules, does it matter if the result is erroneous? How much administrative discretion is it advisable to resort to?Footnote 87 Turning the Governor General’s arguments around, Grant wrote that the “incorrectness” of the general list was entirely the fault of “the deceit practiced by these Inhabitants in disobeying the Order issued to that effect.”Footnote 88 A few days later, now in Madras, he added that Major Tolfrey, his predecessor, had explicitly instructed the inhabitants to indicate if they had families, which they had neglected to do. Their “motives,” reported Grant, were driven by their apprehension that their families “should be sent along with themselves.”Footnote 89

What does this all tell us about colonial biopolitics? The EIC necessarily relied on local information, and some locals sometimes chose to remain silent or refused to collaborate. But one should not overplay the efficacy of this “resistance”: the manipulation of data by both sides could have unintended consequences for both parties.Footnote 90 Far from interpreting this attitude as a sign of moral rectitude, Grant described those embarked on the Triton as men “of the lowest order and most pernicious principles,” and “their female Connections left behind mostly similar to those of our European Privateers.”Footnote 91 This implicit reference to illegal and immoral trades was not chosen at random; he criminalized these individuals by painting them as prostitutes and vagrants. It is not a big stretch to imagine that, from the family members’ perspective, disclosing too much information would be seen as risky. But how much was Grant overstating his case, blaming local populations to cover his own mistakes? It is possible that he was simply resorting to an administrative trope, invoking the alleged resistance of local people to shield himself. Either way, Grant chose to highlight the near-impossible task he was given: “I was enjoined the strictest secrecy, a Circumstance that prevented my making all these necessary enquiries from the apprehension of causing suspicion of what was going forward.”Footnote 92

In addition to showcasing his logistical and material difficulties, and laying the blame at the foot of others, Grant played down the importance of his own errors. Whether they were fathers of families or not, most of the deportees were not simply fierce characters: they were blood-thirsty Jacobins. So Grant introduced the notion of revolutionary danger after getting in trouble for deporting the wrong people. These men had been holding clubs in Pondicherry “for the purpose of irritating less violent men against the English Government.” Without identifying a specific source, and vaguely alluding to “the Knowledge of many respectable men here,” he quoted the deportees at their moment of embarkation: “If we have a regret it is that we do not remain long enough here to drink the blood of every Aristocrat but we shall return and long for the accomplishment of our wish.”Footnote 93 Recycling anti-Jacobin tropes, Grant was certainly playing to his audience of EIC officials. Fort William College, in Calcutta, was for example established in 1800 by Richard Wellesley, Governor-General of British India, with the explicit aim of fighting against the dissemination of the “‘erroneous principles’ of the French Revolution” among its employees.Footnote 94 Sending the Frenchmen out of the “colony,” concluded Grant, was a truly “indispensible [sic] and praiseworthy duty.”Footnote 95

The British captain thus chose to shift the conversation to the ideological terrain. By emphasizing the danger of the French Revolution, he showed himself, as the French saying goes, as “more royalist than the king.” As far-fetched as this might appear, Grant was not completely making things up, but he cleverly muddied the waters by conflating the alleged political conspiracy against the EIC with a past plot against the French monarchy. Far from disobeying his superiors, he stressed his ability to understand the true meaning of their intentions and act decisively. He thus mentioned the discovery by the French authorities in Pondicherry, in August 1790, of a “dreadful Conspiracy … for the Massacre of all the better sort of Inhabitants.”Footnote 96 This plot is described in some detail by a Tamil man named Vîrânaicker, in his diary.Footnote 97 Vîrânaicker wrote that the conspirators had planned to “kill all the leading figures in Poudouvai [Pondicherry in Tamil]…, to loot the homes of certain Frenchmen and Tamijars [Hindus],” and had entered the colonial assembly with charged pistols to seize power.Footnote 98 The way in which the French authorities had dealt with this threat, implied Grant with some reason, was not so different from what he himself had done almost a decade later. Indeed, as described by Vîrânaicker, upon the discovery of the plot, seven of these men had been escorted to a ship by soldiers and deported to France by the authorities of Pondicherry, despite the pleas of their families.Footnote 99 And several of them, having returned from France, were again involved in the 1799 events. Rather implausibly, Grant added that they had actually been sent back to Pondicherry by the French Directory, “as fit instruments to carry on their sanguinary purposes.”Footnote 100 This demonstration legitimized his decision to put three of the 1790 deportees on board the Triton. He was reworking his data, in order to offer a new narrative in defense of his actions.

As shown by Jack Goody, the way in which items are arranged in a list creates an expectation as to the coherence of the whole.Footnote 101 Being placed on the same list as so-called suspect and violent people generated, by an effect of visual coexistence, the sense that all of them belonged together. In this table, the comments were almost all of a negative nature, contaminating by contiguity the other members of the “group.” If the 1799 conspiracy was not sufficient to justify the deportation of the Frenchmen from Pondicherry, the precedent of 1790 would be. Despite the succession of regime changes, and whether it targeted the French colonial government or the EIC, the Jacobin danger remained the same.

Another list was produced to bolster this rhetorical strategy. Thirteen members of a “violent Democratic Club here … [had] publicly expressed their hope of the arrival of Tippoo Sultaun and Buonaparte in the Carnatic.”Footnote 102 This allegation played on the well-founded fears at the time of an alliance between Tipu and France.Footnote 103 They were all among those deported on the Triton. Did it really matter then that most of them had left relatives in India, like Morpin, who had “six natural children,” Pottier, who “separated from his wife 6 years ago,” or Le Normand, who left a “Wife & two children”? Since he had so cleverly second-guessed the government’s intentions, Grant surely should not be blamed for not exempting any of these “wretches.”Footnote 104 Another list of nineteen “Conspirators of 1790,” “which will be attested by every respectable Inhabitant of Pondicherry,” furthered his point. Louis Ferray was “A violent Democrat,” Jules “a Sanguinary Villain,” Carcassonne “a most abandoned Profligate,” and Bertaud “an infamous Subject.”Footnote 105 These damning epithets had one single purpose: to turn the gaze of the Governor away from the family situation of the deportees.

The next step was to question the nature of these relations. Whatever Grant’s attempts at demonstrating the rationality of his selection, he still had to explain how so many men with family had ended up on board the Triton. He chose to blame the deportees: they had disobeyed his orders and “concealed having family” until after their embarkation.Footnote 106 François Aubert, for instance, appeared as single on Grant’s 27 January list, whereas the British officer had subsequently found out that he was married and had one child. This was not an exception: “I can venture to affirm upon the best information as of my own present Knowledge that there are not ten men in Pondicherry from the age of Twenty years upwards, who are not either married, have Children mothers Sisters, &c &c such being the case, how could I have Carried into effect the recent orders of Embarkation of so many bad men without leaving dependents on their bounty, not ten unconnected Men could have gone.”Footnote 107

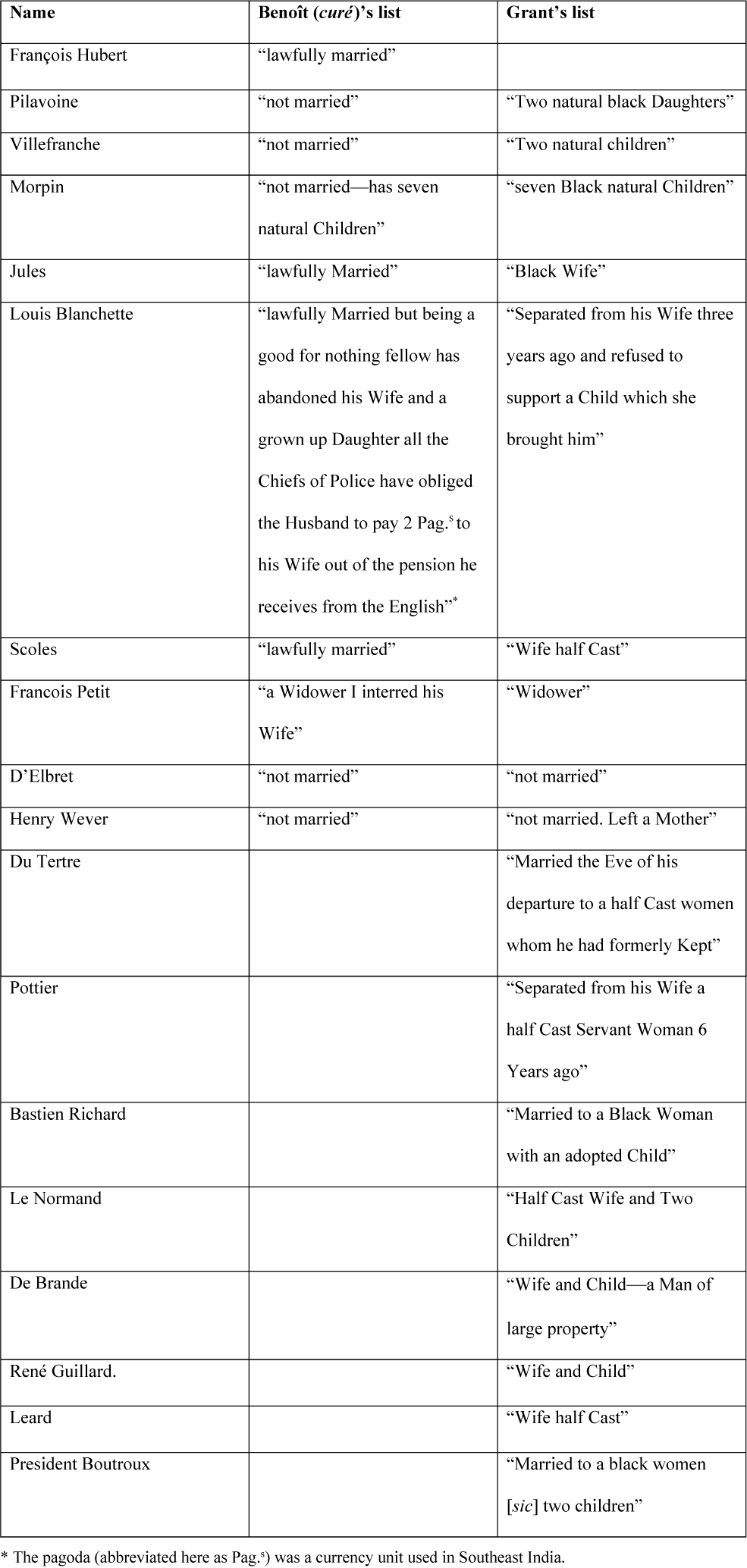

Who were these men’s partners? What was their matrimonial status? And where did Grant get this information? Let us begin with the latter question. One of the main holders of local knowledge in eighteenth-century Pondicherry, as in metropolitan France, was the parish priest. Only after the Triton had sailed did Grant ask the curé about the deportees’ families. On 22 February 1799, Grant wrote to the Governor that he had obtained “Certain tho’ late Knowledge” about “the legitimacy of these families & of their respective Characters.”Footnote 108 A few days later, he sent the copy of a list (a “certificate”) written for him by Benoît, the Capucin curé. Footnote 109 This list confirms what we know about demographical patterns in French India, and more broadly in colonial territories: formal relationships, by way of marriages, were not the rule.Footnote 110 The list is also rich in terms of the information that it does not tell us. In our sources—and this is a characteristic of colonial archives and a problem for historians of women more generally—women’s names are not specified. But it is also striking that the curé’s “certificate” says nothing about the phenotype of these women and children. This is surprising not so much because colonial officials and bureaucrats used a coded language to describe women of color, but because it contrasts with a second list that Grant drafted on the same day (figure 3).Footnote 111

Figure 3. Two Lists Grant Sent to Madras.

Source: Grant to Webbe, 22 February 1799, TNAC, MDC, 250A, ff. 1210–11.

The first contains ten names, and the second seventeen, with eight men featured in both. Morpin was described by the curé as having “seven natural Children,” whereas Grant specified that his children were “Black”—a term which, in this context, probably meant Indian/Tamil. Likewise, the French certificate mentions that Scoles was “lawfully Married,” whereas Grant stated that his wife was “half Cast.” Although the curé had not indicated the phenotype of Pilavoine’s and Morpin’s partners and children, it is seemingly Grant who introduced racial categories in his account and his lists. Eight out of the seventeen marital partners or children were thus labeled as “black” or “half cast.” Grant might have gotten this information after questioning Benoît and consulting the Pondicherry parish registers. While the latter did not specify people’s phenotype, they indicated their birthplace, as was common throughout the French colonies in the Indian Ocean.Footnote 112 Thus, Antoine Scolscé or Scolse was a “native of Trinquamalé,” whose mother hailed from Ceylon, and was married in 1788 to Marie Françoise Moitié, a “native of Pondicherry,” whose father came from Mayenne in metropolitan France and whose mother was a native of Madras.Footnote 113 Prudent Boutroux was described by Grant as “married to a black Woman two children.” The parish registers stated that Boutroux, then aged twenty-nine, had been married in 1788 to Victoire de Regine, a fifteen-year-old minor and native of Pondicherry.Footnote 114

The information contained in Grant’s list was, then, generally consistent with that available in the parish registers. Read alongside this source, Grant’s list also gives a sense of the conditions under which some of these unions were contracted. Du Tertre was “Married the Eve of his departure to a half Cast Woman whom he had formerly kept.” The marriage registers for 8 February 1799 state that the curé Benoît married Jean Baptiste Tertre, marine officer and native from metropolitan France, and Marie Albert, born in Cadéhépè (Kalapettai?) to a mother who was a native of Pondicherry. The newly wed were exempted from the banns of marriage “for just and legitimate reasons.” At the same time, the parents legitimated their seventeen-month-old son by baptizing him.Footnote 115

All this confirms that lists should also be read as rhetorical strategies, aimed, in this instance, at showing that Grant had selected the right people. Benoît had presumably not mentioned this information in his certificate because Catholicism and the union’s legitimacy were his main preoccupations, more than his parishioners’ phenotype. Taken together, Grant’s lists were calling into question the deportees’ conjugal status, either because their marriage was too recent, because the partners lived in concubinage, or because their wives were not “European.”

Grant was thus putting his finger on a fundamental aspect of Pondicherry society, and more broadly of the Francophone Indian Ocean, namely its high degree of miscegenation.Footnote 116 But why did he feel the need to stress the racial hybridity of these families in his correspondence with the Company? All European empires faced a similar challenge of gender imbalance. While local marriage was encouraged by the EIC, only a minority of the poor whites in British India married Indian or Eurasian women, whereas the rest lived in concubinage.Footnote 117 Among Company officials, concubinage was seen as illegitimate, and was increasingly regarded with hostility, just as the numbers of children born out of these relationships was growing. By the end of the eighteenth century, the mothers of mixed-race children were beginning to be described as exerting a corrupting influence on British soldiers.Footnote 118 This is certainly why Company officials did not lose sleep over the fate of the children of the French deportees in 1799.

To return to Grant, we do not know whether he was “disciplined” in the “empiricist practices of colonial rule,” or whether he improvised, in the spur of the moment.Footnote 119 What seems clear is that his justification resorted to a discourse that he knew would strike a chord among his superiors. Himself a product of the EIC’s army, Grant might have applied the same principles when confronted with mixed-race couples in French India. But might there also have been personal reasons for his ambivalent attitude toward the deportees?

Here we must speculate whether the British captain’s own professional and personal trajectory might also explain his predicament. Robert Monckton Grant was born in Montreal between 1758 and 1761, in another space of intersection between the British and French empires.Footnote 120 He was the illegitimate son of Scotsman Lt-Gen Francis Grant. Francis’ offspring appears indirectly in one paragraph in the pedigree of the “Grants of Grant”: “Francis, born 10th August 1717. He became a General in the army. He married Catherine Sophia Cox, and died on 29th December 1781, leaving issue.”Footnote 121 In the same manner that Grant erased illegitimate children from the archive, he was himself barely visible in the colonial records. The birth certificate of Robert Monckton’s son James Ludovick tells us that he was born in India in 1807, probably out of wedlock, to a woman named Maria Tressenah, who died in childbirth.Footnote 122 Based on her name, she might have been Indian. One could venture further into the terrain of Freudian family romance.

Grant did not waste ink and paper: his supplication led his interlocutors to a U-turn. The Company hierarchy in Madras realized that some of the deportees should have been exempted, but they did not recall the ship to India; instead, they accepted Grant’s plea for indulgence. Webbe wrote back to him on 1 March 1799, expressing the relief of the Governor-General of Bengal, Lord Wellesley, upon reading his account.Footnote 123 It was certainly the case that the information upon which the embarkation on the Triton had proceeded was “defective and erroneous,” but he said neither Grant nor his predecessors in Pondicherry should be blamed for it.Footnote 124 Instead, the chief cause of the mistake, which had led Grant to disregard the exemption of “the heads of families from embarkation,” was to be “imputable to those alone who were chiefly interested in the event”: the families themselves.Footnote 125 In a perverse reversal, the letter drew an analogy between the suffering of the British officials and the victims of their disastrous decision: Wellesley was said to be relieved from an “anxiety” that had been caused “by the apprehension of having occasioned severe but unintended distress.”Footnote 126 The “national honour” was safe: no one could accuse the Company of “the inhumanity of separating the families by compulsion from their husbands and fathers.”Footnote 127 The measure of a nation’s moral worth on the basis of how it treated its enemies was a common discourse in this period, which was applied to prisoners of war as well as civilians.Footnote 128 Apart from these attempts at rewriting history, this exchange also tells us something fundamental about colonial knowledge: if the families were able to provide officials with erroneous or misleading information, it is because they were the main font of information. Either way, it was logical to stick to the initial plan, and let the Triton continue its journey to Europe with its human cargo.

In a letter of 13 August 1799, the Fort St George government rationalized the whole affair ex post facto. Grant’s damning portrayal of the men and their wives was stiffened: the former were all “of the most abandoned characters and desperate fortunes,” while the families they had left behind were “chiefly of the lowest class of the natives of this country.” This reinforced Grant’s crude dichotomies, which were themselves based on a racialized reading of the French curé’s lists. The frequency of intermarriages between “Europeans” and “natives” in French India would have made a strict application of the Company’s instructions impossible, added the government after the facts. Moreover, it now seemed clear that the wives of the deportees were not so sad to see their husbands’ backs: “even the recall of those who had departed would not be acceptable to their families.” “Nothing,” concluded Grant’s superiors, “was wanting in attention to humanity.”Footnote 129

The Company was only too happy to accept Grant’s explanation that the deportation had been a blessing in disguise for the families of the deportees. In his lament, Grant had emphasized his “feeling for those persons who were embarked on the Triton,” using the passive voice to downplay his own role in the process. In these informal exchanges he also presented himself as a model soldier and “public” servant, whose ethical concerns should be condoned by the Company, because they were also the values of the institution.Footnote 130 Showcasing his profound sense of humanity, Grant reported the gratitude of the families for “the lenient manner” with which he had executed his orders and “the consolation” which he afforded those left behind.Footnote 131 The deportation had given the families access to new sources of income: “Since the embarkation several of these families came forward with their Claims perfectly happy at the event, alledging that they were before the departure of their husbands fathers or Sons, in a state of Starvation, that now the English Government would amply provide for their wants.”Footnote 132

The rule of the EIC was thus presented as beneficial to the local populations, as substituting itself for the pater familias who failed to fulfil their duties. This cheerful letter reads very differently when compared to an earlier one, that Grant wrote on 17 February: “I am sorry to announce, that the wife of one of those embarked, died yesterday, in consequence of the alarm and grief which the sudden seizure of her husband caused her. She was pregnant, and this event brought on a premature labor, that carried her off; another in an almost similar situation now lies at the point of death, so that both these persons will in all probability be erased from the list, or at least considerably diminished.”Footnote 133

Neither woman was mentioned by name by the British captain, and my attempts to identify them have so far been unsuccessful.Footnote 134 In this administrative correspondence, the female partners of the deportees were always described as anonymous victims, who would be relieved from the burden of their criminal husbands. These statements buried these women’s voices under a thick layer of patriarchal discourse. Indrani Chatterjee has warned against the unquestioned assumption that indigenous women were inherently waiting to be saved.Footnote 135 Behind the Company’s discourse on Franco-Indian couples was the idea that they were not real relationships, and that, for Indian women, their male European partners were interchangeable. Grant might also have been alluding to the exploitative nature of some of these relationships, expressed in the language of humanity and illegitimacy.Footnote 136

The policies of assistance that were put in place after the deportation were rooted in the same racialized, gendered, and social ideology.

The Politics of Relief: The Wives, the Old, and the Weak

What happened to those who stayed behind? The EIC always knew that families would struggle financially once these men were gone and had planned to distribute pensions and allowances as soon as the Triton would leave the port.Footnote 137 To select those who would be eligible to relief, Grant’s successor was influenced by the consequences of his misadventures. He also relied on lists but limited their interactive and iterative nature.

This wartime social relief was triggered by the breakup of families, which the Company itself had caused. An apparent schizophrenia saw the state try to fix with one hand what it had broken with the other. Instead of seeing this as a contradiction, one needs to understand that the two sets of actions—deporting the men and caring for their families—were two sides of the same coin. In India, charitable endeavors have been described as manifestations of the British claims to moral superiority, couched in terms of the “civilizing mission.”Footnote 138 Humanitarian relief was also folded into a broader military objective, which often entailed coercing colonized populations, fixing them on the territory, and forcefully putting them to work.Footnote 139 In the same way, as I mentioned, using Foucauldian concepts of colonial governmentality and biopower, historians, geographers, and anthropologists have explained the Company’s policies of assistance as modes of regulation over colonial sexuality and reproduction.Footnote 140

But it might also make sense to situate these policies of assistance within other contexts, too. In the metropole as well as in India, the EIC had by this time long relied on philanthropic policies and corporate charity.Footnote 141 The French Compagnie, too, for similar reasons, had a long history of supporting European orphans, widows, and the poor.Footnote 142 In Pondicherry, the three groups singled out as deserving the EIC’s charity were the parents of large families, the elderly, and the infirm, as long as, based on “their known principles or Situation in life,” “there may be no fear of their engaging openly or clandestinely to promote the Service of Tippoo Sultan.”Footnote 143 In eighteenth-century England, also, the same groups were customarily identified as particularly worthy of parish relief.Footnote 144 But in this colonial context, the politics of care intersected in specific ways with race and class. Once again, the selection of the worthy was supported by lists crafted by army officers. But, as we will see, lessons were learned from Grant’s misadventures, and the new lists were less dynamic than previous ones.

Captain Grant was also in charge of the next phase of the plan. He was to “entirely evacuate” Pondicherry and march its European inhabitants to the camp of Poonamally (Poonamallee, in the vicinity of Madras), 147 kilometers away.Footnote 145 The journey could not be done in one stage. Walking this distance while carrying personal properties also necessitated some support for transport and accommodation, and tents were to be carried along the way by boats and bullocks.Footnote 146 A constellation of human and material factors determined the success of the evacuation, and it commenced a full month after the Triton’s departure. On 9 March, Grant, commanding the detachment, wrote from Killanoor camp, about 22 kilometers from Pondicherry, that he had only begun the march on the previous day, because “of the great trouble and confusion attending the removal of these people.”Footnote 147

He did not pass on the opportunity to draft more lists. One contained the names of eighty-nine “European Inhabitants of Pondicherry” proceeding to the Presidency with the detachment. Another listed forty-eight “topas” inhabitants being sent to the same place, following the Governor’s instructions.Footnote 148 The so-called topas were usually Catholic descendants of Portuguese settlers in India who had a mixed Portuguese and Tamil ancestry.Footnote 149 At the beginning of the 1790s, the French Colonial Assembly repeatedly attempted to class them as “indigenous Indians” in order to deprive them of political rights.Footnote 150 This same process of racialization was taking place at the same time in other French colonies in the Indian Ocean, where mixed-race unions, long frowned upon, if tolerated in practice, were increasingly regarded with hostility by royal and colonial administrators.Footnote 151

In Pondicherry, Lieutenant P. Bose inherited Grant’s responsibilities. Having witnessed his predecessor’s struggles, Bose pelted his superiors with demands for specific instructions.Footnote 152 Because many inhabitants sought exemptions from the expulsion, Bose designed a procedure to ascertain the legitimacy of their claims to stay. He first drew up a list of sixty-seven names, which accounted for their age, infirmity, familial responsibility, and character.Footnote 153 Read in sequence, this is a litany of personal misfortunes, combined with relative affluence and impeccable moral conduct. Camus, aged seventy-four, was described as “Of Inoffensive Conduct,” and “Infirm Invalid.” Augustin Dauzas, fourty-six, was “a very good man” and also “very sickly—large Property.” Bayet father, sixty-eight, was “a very good Character” and “bed ridden.”

It is well known that British health policies in India, such as the regulation of prostitution, were aimed at guaranteeing the reproduction of populations.Footnote 154 But how should one understand the protection of the elderly and disabled? Among these individuals, we also find non-white men, listed as “topas” and “half cast.” The emphasis on property also shows that class, in this instance, trumped race. Giving these men the right to remain in Pondicherry owing to their physical frailty was a marker of the Company’s attempts at shaping populations by controlling their mobility and immobility through a security imperative.

This is clear in Bose’s second list, which exempted thirty-seven individuals for various reasons.Footnote 155 Some were too ill to travel, while others were family carers. By comparison with the language Grant used to justify his final selection of deportees, Bose did not focus on the revolutionary or radical intentions of potential suspects, but on their incapacity to cause trouble: “their very inoffensive Characters … render them free from the intention or power to do wrong.”Footnote 156 At the same time, for Bose, race remained one of the main criteria of categorization. He used racial descriptors, such as “country born,” “half cast,” “topass,” or “very dark,” for sixteen out of the thirty-seven individuals. In addition to health, “usefulness” to the local community was a criterion of exemption. This was the case of teachers: Gilles Lois, twenty-four and a “half cast,” “keeps a School for poor Children,” while Dom Damoy, twenty-eight, also a half cast, was “left behind at the intercession of several families whose Children he teaches.” Medical professions were crucial given the number of the poor, the elderly, and the sick who now constituted a large proportion of the population: Jos[eph] Sochont, aged forty-one, was allowed to stay because he was “The only Medical Man consulted by the Whole of the Families here—his removal would be most severely felt.” Some rich merchants were also on this list because the prosperity of the town depended on their business. Finally, a few paper pushers were left in the city to allow for some administrative continuity.

Overall, this paperwork allows us a glimpse of the daily troubles faced by a colonial officer, made to do bureaucratic work and implement crucial decisions with little support on the ground. Worried due to the fate of his predecessor, Bose insisted that the details he had collated were accurate, “as far as information and my own knowledge affords.” In a tear-inducing plaidoyer, he tried to elicit sympathy: “In the course of this Complex and … painful Service, I stood alone and unassisted except in the case of a few enquiries as to Character and property, and even herein I reserved some decision from my own observations if therefore I have erred I sincerely hope that it will be ascribed to my Judgement and to no want of zeal for the public Service, or real wish to meet the wishes and pay due obedience to the Orders.”Footnote 157 Professing his ethos as a dedicated public servant, well aware of the chain of command, he also defended his recourse to discretion, and tried to preempt future reprimands. This language, which echoes Grant’s own self-justification, illustrates how far the experience of these soldiers was from that of bureaucrats.

*****

By approaching colonial lists as a media form, and thus highlighting their iterative quality, this article sheds light on the conundrums of imperial administration. Looking at the work of the officials who drafted and used this type of documents helps us understand their fundamentally political nature. The lists were unstable and based on contingent and constantly evolving information that bureaucrats and army officers on the ground inherited from previous colonial regimes as well as local populations. This article has focused not on the construction of categories, but rather on the process by which individuals were placed on one list, and then erased or moved across to others. To explain these transfers, I have emphasized the international and military context, power relations within the EIC, and the agency of families and individuals who contested their allocation to a given category.

The Pondicherry lists were produced at a particular moment in the history of the British colonization of India. At the same time as the EIC was expanding territorially at the expense of its European and Indian rivals, the awareness that its domination was precarious fueled fears of conspiracies. In turn, this led authorities to inflict violence on various groups, embodied in the lists. As in other empires, during periods of transition in the British Empire, officials looked for guidance to their predecessors’ accumulated experiences. In the present case, the knowledge that was collected in the colonial lists came, in large part, from previous French documents and actors.

The struggles around list-making and revising also bring to the fore the conflicts and contradictions that existed within the imperial state between two presumptive biopolitical logics of imperialism: security and protection. From 1792 onward, the Company’s wars of conquest on the Subcontinent transformed the early colonial state into “a very military state.”Footnote 158 Major Tolfrey, Captain Grant, and Lieutenant Bose were given assignments that would later be considered “civil” duties, such as making lists of deportees. Their task entailed interpreting ambiguous orders from above while adapting to ever-changing local situations. The categories the Company used to deport people were based on irreconcilable criteria. Captain Grant’s struggled to come up with a satisfactory list in the eyes of his superiors because they had given him an impossible job. Originally, he was supposed to list people according to two different logics. On one hand, he had to apply humanitarian principles, which led him, for instance, to exempt the fathers of numerous families—a principle that was ill-defined, both because “numerous” is a subjective term and what constitutes a “family” is a cultural construction. Women, children, the elderly, and the disabled were also seen as harmless and so exempted. On the other hand, Grant had to list potential troublemakers, dangerous individuals, or those sympathetic to the French Revolution. But that notion was based on mere possibilities; that is, the hypothesis, rarely based on evidence, that these individuals might someday be involved in violent action against the EIC. Other criteria, such as class, could also play a part in categorial assignation: a rich merchant could be suspected of bankrolling the conspiracy, while poverty might indicate that one could be bought off.

As shown by the treatment of “mixed-race” people, colonial officials increasingly saw the populations of extremely diverse origins and statuses who coexisted in Southeast India through the lens of miscegenation. This explains why most of those described as “half cast” were not deported to Europe, unlike “Europeans.” By the same logic, “topas” people were not trusted enough to allow them to remain in Pondicherry and so were removed to Madras. However, racial categories were highly contextual, as shown by Grant’s creative reading of French birth registers, translating women’s and children’s birthplaces into designators of their phenotype. While a comparable process of racialization was taking place across the Indian Ocean, in different European empires, it was left to actors on the ground to decide who belonged in a list and who did not.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this article were presented at seminars in Munich (LMU-Global Dis:Connect), Tübingen (ERC Atlantic Exiles), and Zurich (History seminar), whose audiences offered generous critical feedback. I am also grateful to Martin Dusinberre, Jan Jansen, and Simon Schaffer for their insights. For their comments and suggestions on previous drafts, I wish to thank Shane Boyle, Sara Caputo, Julian Hoppit, and Jean-Paul Zuniga, as well as the anonymous readers for CSSH.