In the application for a Canadian visa filed by Dow Z. at the beginning of February 1948, a caseworker wrote that the seventeen-year-old Polish orphan ‘would be happy to go to Canada and have at last a home, study, work, and forget his ordeal and troublesome past’.Footnote 1 Dow had survived the war in hiding in the eastern part of Poland. After the liberation of the area, he wandered alone for several months, describing to the caseworker how he was ‘being fed from time to time by peasants’. In 1945, he travelled through Hungary and Austria in circumstances undocumented in his case file and ended up in the northeast of Italy where he was sent to a Jewish children's home in the Alps. In 1947 he went to Milan, from where he applied for a Canadian visa one year later. In the twelve months that followed his liberation, the boy had travelled over 1,500 kilometres and crossed at least three borders. To my knowledge, Dow never publicly wrote about his experience. Neither did he later participate in oral history projects such as the Shoah Foundation for Visual History and Education or the Canadian Holocaust Documentation projects.Footnote 2 His Canadian visa application is one of the few, if not the only, sources about his trajectory, but the document gives little information about why he ended up in Italy and subsequently why he went to Canada. Such scarcity of sources is common for refugees and migrants, especially children and adolescents, who are even less likely to have left any trace. How then can historians study their journeys and the motivations behind them?

Dow was among the 1,115 young Jewish survivors (a term that was not used to refer to them at the time) who were allowed to migrate to Canada between autumn 1947 and spring 1952. This refugee resettlement scheme was known as the War Orphans Project and was sponsored by the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC), the main organisation of Canadian Jewry.Footnote 3 These young people were predominantly from Eastern Europe and had been deported or survived in hiding during the war. After the war, the majority were living in displaced persons (DP) camps in Germany, Austria and Italy. Others lived in French and Belgian children's homes, or had left for the United Kingdom, Switzerland, or Sweden. Like Dow, many had complex journeys between the end of the war and their departure to Canada.Footnote 4 Little is known about how these journeys were shaped by factors at local, national and international levels, and about how they were experienced by the young survivors themselves.

In this article, I argue that despite the scarcity and limitation of available sources, one can better understand refugee journeys and the decision making behind them, first, by mapping what was and was not available to individuals at different moments of their displacement and, second, by looking at how individuals navigated these possibilities and constraints. At the core of this approach is the notion of a ‘world of possibilities’ (espace des possibles) that was developed by Claire Zalc and Nicolas Mariot in their 2010 book Face à la persecution in which they followed the wartime trajectories of the 991 Jews of Lens, a city in northern France.Footnote 5 Drawing on the ambitions of microstoria pioneers, they argued, alongside Tal Brutmann, that ‘reducing the level of analysis increases knowledge, because smaller spaces can better elucidate the complexities of decision making, helps re-establish the “space of the possible”, shows how reality was experienced at the individual level, and ultimately provides more compelling insights into the events that contemporaries faced in their day-to-day lives’.Footnote 6 Their efforts built on and contributed to wider discussions around the notion of choice in Holocaust studies that expanded with the work of scholars such as Saul Friedländer and Alexandra Garbarini, who used letters and diaries to capture the subjectivity of the victims and to go beyond the discourses of perpetrators.Footnote 7 In recent years, other scholars have similarly investigated the patterns of behaviour and experiences of persecution of specific groups.Footnote 8 Whether it be the Jewish residents of an eastern Polish town, three ghettos, or a city in northern France, this literature offers a middle ground between the omnipresent redemptive narratives of Holocaust survival – what Simone Gigliotti has called ‘sentimental heroism’Footnote 9 – and Lawrence Langer's notion of ‘choiceless choice’: being a target of mass violence radically limits but does not deprive individuals of agency.Footnote 10

In my article, I draw on this body of work to investigate the young survivors’ journeys but acknowledge one of its limitations: the focus on adults. The emphasis on the individual level and inherently on agency risks overshadowing the specificities of the young survivors’ experiences of displacement as children and youth. Agency has proven to be particularly ‘methodologically unsatisfactory’ with regard to young people.Footnote 11 It is not only under-theorised (in his work on child soldiers, David Rosen notes that agency is ‘more a general orientation toward the child than an operational concept’Footnote 12), but it also places children and adults in simplified binary relationships.Footnote 13 In this article, I therefore argue for an examination of ‘worlds of possibilities’ that takes into consideration age – and especially chronological age – as a category of analysis.Footnote 14 In other words, it is important to consider the young survivors as any other migrants – ‘active but constrained agents embedded in larger networks and institutions’Footnote 15 – but without uncritically emphasising their agency and erasing the specificity of their experiences of displacement as young people.

To conduct my analysis, I draw on valuable material: the young survivors’ Canadian visa application files that are stored at the Alex Dworkin Canadian Jewish Archives (CJA) in Montreal. With the opening of the International Tracing Service (ITS) archives, historians of the Holocaust and of displacement during and after the war have increasingly relied on similar sources.Footnote 16 The Canadian corpus is, however, original in its scope as it contains the individual files of all the young survivors accepted into a single large-scale resettlement project. The majority of these files were completed in Europe by workers from two key organisations of the immediate post-war refugee regime, the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC).Footnote 17 The IRO gradually took over the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) in 1947 and in 1952 was replaced by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The JDC was established in 1914 with headquarters in New York and was the main Jewish relief organisation at that time.Footnote 18 There is little information about the profiles and backgrounds of the caseworkers involved. The majority were women who were either from the children's community or had arrived in Europe from the United States, Canada, or the United Kingdom with the IRO or the JDC.Footnote 19 The forms contain many pieces of information to trace individual trajectories during and immediately after the war – especially one section called ‘Persons or institutions assuming care of the child’ that gives a timeline of locations from 1939 to the moment of the application – but say little about the reasons why the young survivors applied for a Canadian visa.

Despite the silences of these forms, I address two essential questions regarding the decision making and motivations behind refugee journeys and migration trajectories more generally: the departure (why did the young survivors leave Europe?) and the destination (why did they go to Canada and not elsewhere?). After discussing the challenges inherent to the source, I first examine the young survivors’ situation in their countries of residency in Europe and consider potential explanations about why they left. These include the increasingly hostile national policies toward refugees, the stricter relief policies for DPs implemented by Allied military authorities and international organisations and the growing financial difficulties of Jewish aid organisations. Second, I explore what migration options were available to them: I argue that the limited possibilities of migration to mandatory Palestine/Israel and the United States are essential to understand the journeys of the young survivors and their resettlement. Third, I examine how various factors contributed to change this ‘world of possibilities’ and reduce the chances of the young survivors leaving for Canada.

By unravelling the fragmented nature of the young survivors’ journeys and the contingency of the decision making behind them, this article's contributions are threefold.Footnote 20 The first is specific to my case study: I challenge teleological and linear readings of the migration of Holocaust survivors to Canada and demonstrate how the country was often a second-choice destination. The second contribution applies to Holocaust studies, and especially to the subfield of aftermath studies as has been coined by Verena Buser and Laura Jockush.Footnote 21 By documenting both recurring patterns and more outstanding and marginalised trajectories, this article responds to Ivan Jablonka's call to examine the fates of Jewish children and youth ‘beyond the boundaries of their countries and communities’.Footnote 22 Alongside the work of Françoise Ouzan, Laura Hobson-Faure and Rebecca Clifford, it participates in a global history of the young Jewish people's post-war experiences of displacement.Footnote 23 The third contribution extends beyond Holocaust studies: I argue that the article's analytical framework – the notion of a ‘world of possibilities’ and an emphasis on age as a category of analysis – could be a useful alternative to the concept of agency, not only for historians but for all scholars determined to take into consideration the experiences and perspectives of young people on the move.Footnote 24

Mapping Uncertainty

The case files are valuable but their analysis is challenging for historians. First, one must keep in mind that the trajectories that emerge from the case files are narrated and mediated. As such, the source reveals only what the applicants were willing and able to recount and what the caseworkers understood and decided to write down. They are predominantly the words of the caseworkers, who may have misconstrued, reformulated, translated or misunderstood the stories they were being told. Many parts of these narratives are therefore untrustworthy or altogether silent.Footnote 25 This uncertainty and inherent speculation need to be acknowledged and accepted.

The second challenge is particularly important when looking at the experiences of young people. The crucial question of the influence of others, especially adults, in shaping the young survivors’ journeys is often partially answered in the case files. In his micro-study on the boys who were with Elie Wiesel in the January 1945 transport from Auschwitz to Buchenwald, Kenneth Waltzer argues that one of the leading ideas about prisoner society – the radical isolation of prisoners who ‘composed a coerced, seriated mass without solidarity or connection’ – must be reconsidered.Footnote 26 The same was also true after the end of the war: the rebuilding of many young survivors’ lives was importantly ‘based on pairs and small groups’.Footnote 27 This is true for adult refugees but even more important for children and youth, whose room for decision making is narrower. Many had siblings, relatives and friends, and these networks were crucial in shaping their ‘worlds of possibilities’.Footnote 28 The case file, alongside the wider tendency in Holocaust studies to focus on survivors as individuals and not as members of families and groups, can overshadow the collectiveness of their migration and the specificity of their experiences of displacement as young people.Footnote 29

Notwithstanding this uncertainty, documenting individual trajectories allows one to grasp the complex and transnational nature of the young survivors’ displacement in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust. Like Dow, who travelled over 1,500 kilometres, many of these trajectories are made of detours, wanderings, delays and roundtrips – what Paul-André Rosental has called the ‘invisible paths’ of migration.Footnote 30 This fragmentation predominantly disappeared from later narratives. Such invisibility has several explanations. First, scholarly works based on local, national or institutional frameworks frequently overlook the complexity and transnational nature of refugee journeys. It also disappears from the majority of Holocaust survivors’ memoirs and oral testimonies in which inconsistencies and hesitations are often erased. The post-war journey is either unmentioned or presented as a linear process and a rational choice. This absence reflects both the inherent need for coherence in individual narratives – what Pierre Bourdieu has contentiously called ‘biographical illusion’Footnote 31 – and how earlier events (survival during the Holocaust) or later events (life in a new country) often overshadow the significance of experiences of displacement in the immediate aftermath of the war.Footnote 32 Because the journey did not fit into the collective memories and national narratives of either their country of origin or arrival, it ended up being overlooked or ignored. This absence, reinforced by the low visibility of young people, should not undermine the fact that these journeys were often profoundly transformative and are essential to understand the survivors’ post-war lives.Footnote 33

By going beyond individual narratives and national frameworks, writing the history of such a large cohort and mapping the trajectories that emerge from the case files helps to restore the unstable and transnational nature of post-war refugee journeys. It can also help to grasp the more outstanding trajectories that often stand at the peripheries – in meanings and in spaces – of our current definition of Holocaust survival. The following two case studies illustrate the need for a broader understanding of experiences of displacement both during and immediately after the war. The first is the trajectory of Max E., a young German Jewish orphan.Footnote 34 The boy had lived in Germany for just over a year: born in 1932, he left the country with his parents shortly after Hitler came to power. The family fled to Alexandria in British-ruled Egypt. Host of the largest Jewish community in the country, Alexandria was relatively free from any fighting during the war, but with the gradual withdrawal of British troops and the increased tensions around mandatory Palestine, the situation of Jewish populations in Egypt rapidly deteriorated. Riots and bombings targeted them in Cairo and Alexandria, especially after the start of the first Arab-Israeli war.Footnote 35 Max's parents were killed in a pogrom in 1949. Max left the country soon after and went to France, where he was taken care of by a Jewish youth organisation. There is no information about the nature of his journey, but his destination could be explained by the strong cultural and political links between Jewish populations in Egypt and France – French was by far the most common spoken language, other than English or Arabic, among Egypt's Jews. Aged seventeen at the time, Max might have travelled on his own initiative or benefitted from existing networks between the two countries that played a crucial role in the flight of Jewish refugees after 1956.Footnote 36 He lived in Paris until February 1950 and left for Canada a few days before his eighteenth birthday. Max is the only applicant who was not, strictly speaking, a Holocaust survivor but a victim of the violence that resulted in the aftermath and contributed to the massive departure of Jewish populations from the Maghreb and Mashriq.Footnote 37 His trajectory exemplifies how the case files can reveal marginalised journeys and help challenge the ‘nearly exclusive focus on Shoah-related events and people in Europe’ in conservative understandings of Holocaust survival.Footnote 38

The second case study details the trajectory of Rafael R., who was born in Poland in 1930.Footnote 39 Rafael grew up with his parents and siblings in Pultusk, a town 60 kilometres north of Warsaw. After the rapid collapse of the Polish state in September 1939, the boy was separated from his parents when he fled to the Soviet-occupied parts of the country with friends of the family. After the beginning of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, he was evacuated to Tashkent (now capital of Uzbekistan).Footnote 40 He spent the war there in a children's home – potentially one of the Christian-Polish orphanages that had been set up in the city – among other Jewish evacuees before being sent back to Poland after the war and leaving shortly thereafter for Germany.Footnote 41 The circumstances of his journey westward are not detailed in the case file, but his age can provide a potential explanation: being a minor and separated from his parents at the end of the war might have facilitated his return to Poland, as Polish children in Soviet orphanages were often prioritised in repatriation operations.Footnote 42 Rafael's experience was long forgotten and excluded from narratives of the Holocaust. Recent scholarship has demonstrated, however, that his fate was shared by the majority of the 350,000 Polish Jews who survived the Holocaust for which the Soviet Union, especially Muslim central Asia, provided ‘a crucial if extremely harsh and generally involuntary refuge’.Footnote 43 As suggested by Atina Grossmann and others, we need to redefine our current understanding of Jewish survival. This call should be extended to the aftermath of the Holocaust: rethinking survival also means rethinking post-war refugee journeys. The cases of Max and Rafael strikingly illustrate the wide-ranging experiences of refugees, and the need for a more global understanding of the population displacements that followed the war. They also exemplify, especially in the case of Rafael, the necessity to assess how age – as much as gender, citizenship, nationality or class – had a major influence on what happened or what might have happened during the young survivors’ journeys.Footnote 44

Pressured to Leave Europe?

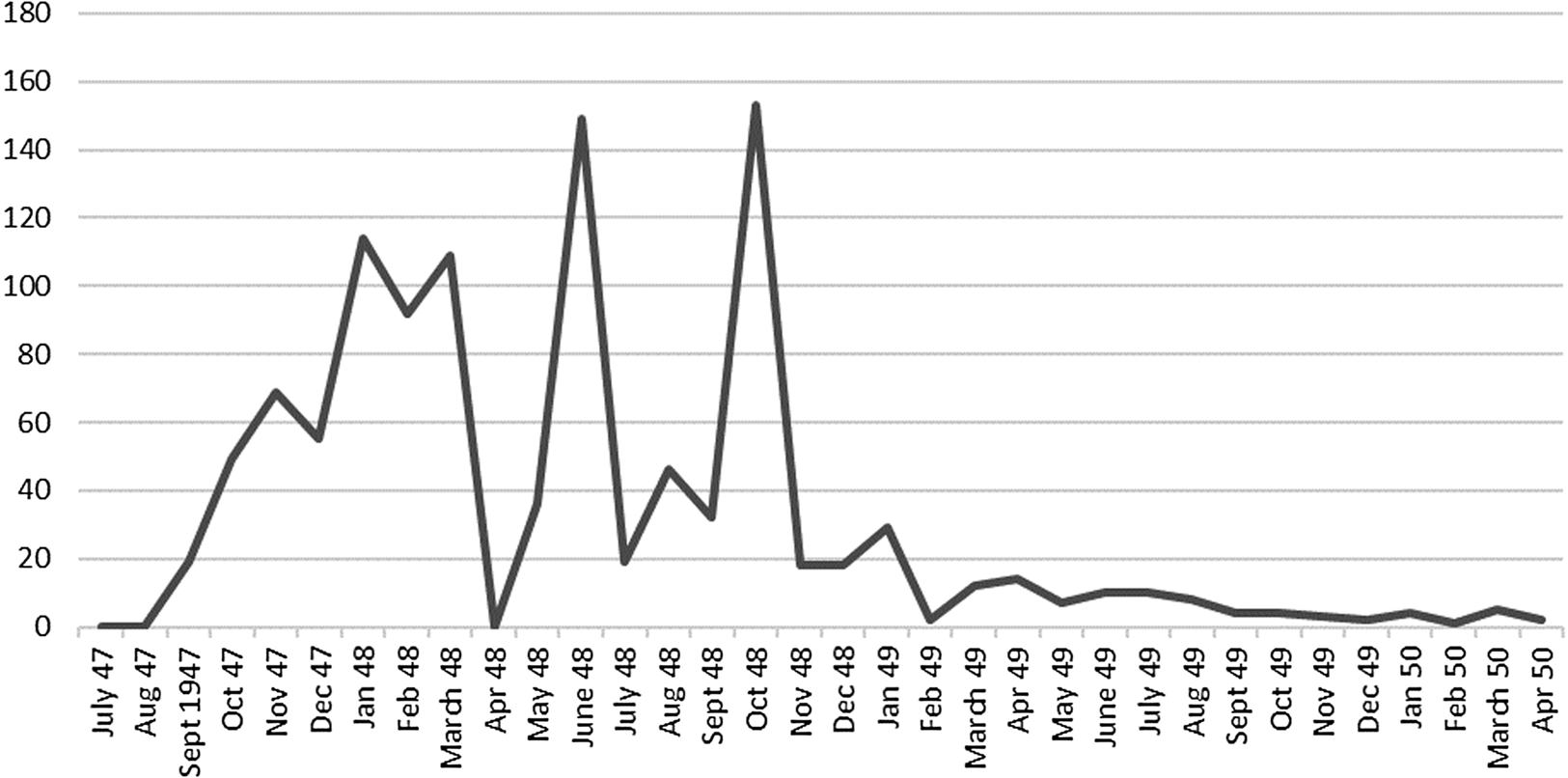

Acknowledging outstanding trajectories is essential to understand the diversity of Holocaust survivors’ experiences. However, in this article I focus on recurring patterns of displacement. I argue that, even though the analysis of migration trajectories cannot be reduced to simple push and pull factors, one can formulate hypotheses about the decision making behind them by mapping the ‘world of possibilities and constraints’. To do so with these case files, it first meant establishing a timeline of the young survivors’ departures to Canada (Figure 1) and, second, assessing what options were available at the time of departure.

Figure 1. Timeline of the departures to Canada, July 1947–April 1950 (y: number of orphans; x: month of departure).

The War Orphans Project was authorised in April 1947 by the Canadian federal authorities with an initial limit of 1,000 visas, which was later extended to 1,250. The selection started in July when the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) sent representatives to Europe. These representatives first received very pessimistic feedback: ‘very few children would be available, 100 to 150 being indicated as the likely maximum’.Footnote 45 They were told that the majority of young survivors had already left or were planning to go to Palestine. Others were hoping to leave for elsewhere, especially the United States. Unaccompanied Jewish children and youth were at the centre of fierce competition between local Jewish communities, nation-states, and similar immigration schemes: the Canadian project was one option among many.Footnote 46

However, the CJC representatives in Europe managed to find enough potential candidates willing to be resettled in Canada in a relatively short period. Most of the departures happened between September 1947 and January 1949. This article demonstrates that several factors in the young survivors’ countries of residency and in the potential countries of transit and arrival contributed in shaping their ‘world of possibilities’ in ways that favoured departure from Europe and, more specifically, a departure to Canada.

First, in 1947, the living conditions of unaccompanied and separated Jewish youth in Europe generally worsened because of various policy changes at local, national and international levels. In the cohort, more than 450 young survivors were in Germany and Austria when they applied for a Canadian visa, especially in the American Zone of Occupation. The majority of these had either been liberated in the east or repatriated from Germany and Austria to their home countries in the months following the end of the war. They had arrived in American-occupied Germany after April 1947 and were therefore regarded as ‘infiltrees’ – populations from Eastern Europe who had entered the country illegally. In 1946 and 1947, the Allied military authorities and the UN implemented stricter relief policies for DPs and gradually closed the occupation zones to ‘infiltrees’. The US Military Government decided to stop recognising any individual who had entered the zone after April 1947 as a United Nations Displaced Person (UNDP). As a result, the IRO was still in charge of the camps, but Jewish relief organisations had to take over most of the refugee services.Footnote 47 This shift in refugee politics affected the everyday lives of many young survivors in German and Austrian DP camps.

It also had consequences far beyond Germany and Austria because it put more pressure on the JDC, which was the main support to many unaccompanied Jewish children. The JDC was the driving force behind the ‘Jewish Marshall plan’ that aimed at rebuilding European Judaism.Footnote 48 It worked in DP camps and with local Jewish communities and invested widely in childcare. However, in September 1947, the JDC decided to adopt a new strategy and cut back its funding, especially in France and Belgium. This was a financial necessity that emerged from a downturn in its fundraising as well as from having to take over the care of the ‘infiltrees’, but it was also ‘a means of provoking a response from the agencies it funded’ and accelerating their centralisation.Footnote 49

This had massive implications for many European Jewish organisations, especially because the budget cuts were followed by policies that targeted childcare: the JDC decided to stop supporting summer camps, taking over the placement cost of children whose two parents were alive and, more importantly, supporting individuals over the age of eighteen.Footnote 50 The new policy forced the French Service Social des Jeunes (SSJ), the Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE) and the Belgian Aide aux Israélites Victimes de la Guerre (AIVG) to change their childcare policies dramatically. Canadian Jewish representatives in Europe were aware of the implications of the JDC's strategic shift, especially for teenagers and young adults. In various memorandums, they pointed out the increased difficulties for the SSJ, which ‘[had] no means to allow [children] to continue school nor [had] they facilities for proper supervision’.Footnote 51 They also noted that ‘with [the JDC] indicating that support may be cut soon and withdrawn some day in the not too distant future, the [AIVG] board is seriously considering giving up some of the children’.Footnote 52 In Belgium, the situation was complicated further because, in spring 1946, non-citizens were no longer eligible for state funding. In 1947, at the request of several Jewish organisations, the government agreed to consider foreign children born on Belgian soil as having de facto Belgian nationality. Between 2,000 and 3,000 children benefitted from this decision, but many others, those who were born outside Belgium, were now depending entirely upon Jewish aid organisations.Footnote 53 Organisations such as the AIVG were reluctant to let children go during the first months following the end of the war but they were now pressuring them, especially those approaching their eighteenth birthday, to leave their institutions and find a solution elsewhere. As is often the case, the strict divide between childhood and adulthood as legal categories determined whether an individual was eligible for assistance. This reliance on chronological age had a massive influence on the experiences of many adolescents and young adults.Footnote 54

The increasingly hostile national immigration and refugee policies, the stricter relief policies for DPs, and the subsequent growing financial difficulties of Jewish aid organisations all contributed to worsening the young survivors’ everyday lives. Some of these factors disproportionately impacted young people, especially adolescents: they sped up the decision-making process of individuals who were already planning to leave and pressured those who were not thinking about a departure to reconsider their options.

An Uncertain Aliyah

Resettlement options in 1946 and 1947 were, however, limited. First of all, a departure to Palestine was not an easy choice. In this section, I highlight two patterns of displacement in the cohort to argue that the difficulties of traveling to Palestine and the precarious situation there led some of the young survivors to give up or at least postpone their Aliyah (i.e. the immigration of diaspora Jews to Israel) in favour of a safer destination. The contingency of Jewish settlement in Palestine in the immediate post-war period had been at the centre of heated discussions. For instance Michael Marrus has argued that many Holocaust survivors would have chosen the United States over Palestine if they had been able to go there in the immediate aftermath of the war.Footnote 55 Similarly, Avinoam Patt has warned historians to dissociate the ‘choices of individual survivors’ from the ‘collective Zionism of the Surviving Remnant’.Footnote 56 Patt and others have further demonstrated that at the beginning of 1947 many Jews in Europe and North America voiced their concerns about the growing hopelessness of Holocaust survivors: many were more willing to explore other migration options because of the very low chances of migrating to Palestine.

Between 1946 and May 1948, British authorities maintained strict control over Palestine, which had been under their administration since 1920: less than 50,000 European Jews managed to migrate there – 30,000 of them illegally. Many more were rejected upon arrival and sent to Cyprus instead or back to Europe. In July 1947, the boat Exodus 1947, with 4,500 Jewish men, women, and children on board, was brutally rejected from Haifa and sent back to France, then Germany. The event was widely covered by international media and was a source of public embarrassment for Britain. It is now considered as a turning point in the diplomatic struggle that preceded the recognition of a Jewish state in 1948, but at that time it sent a clear message that echoed widely within the Jewish survivor population. In the words of the British ambassador in Paris, his government ‘intended to make an example of this ship’.Footnote 57 Entering Palestine was almost impossible.

Even after the UN adopted the Partition Plan for Palestine at the end of November 1947, many Jewish representatives were concerned that people who had just survived long years of persecution could be scared off by the uncertainty and rising tensions in the area and change their plans. Increased violence followed the Partition Plan and culminated after 15 May 1948 in the beginning of the first Arab–Israeli War, which ended in March 1949 with an Israeli victory. The area was at war from November 1947 to March 1949, which corresponds with the period – September 1947 to January 1949 – when the majority of the orphans left for Canada. It is thus very likely that the unstable situation in Palestine and the difficulties of going there led some young survivors, as individuals or as small groups, to reconsider their options.

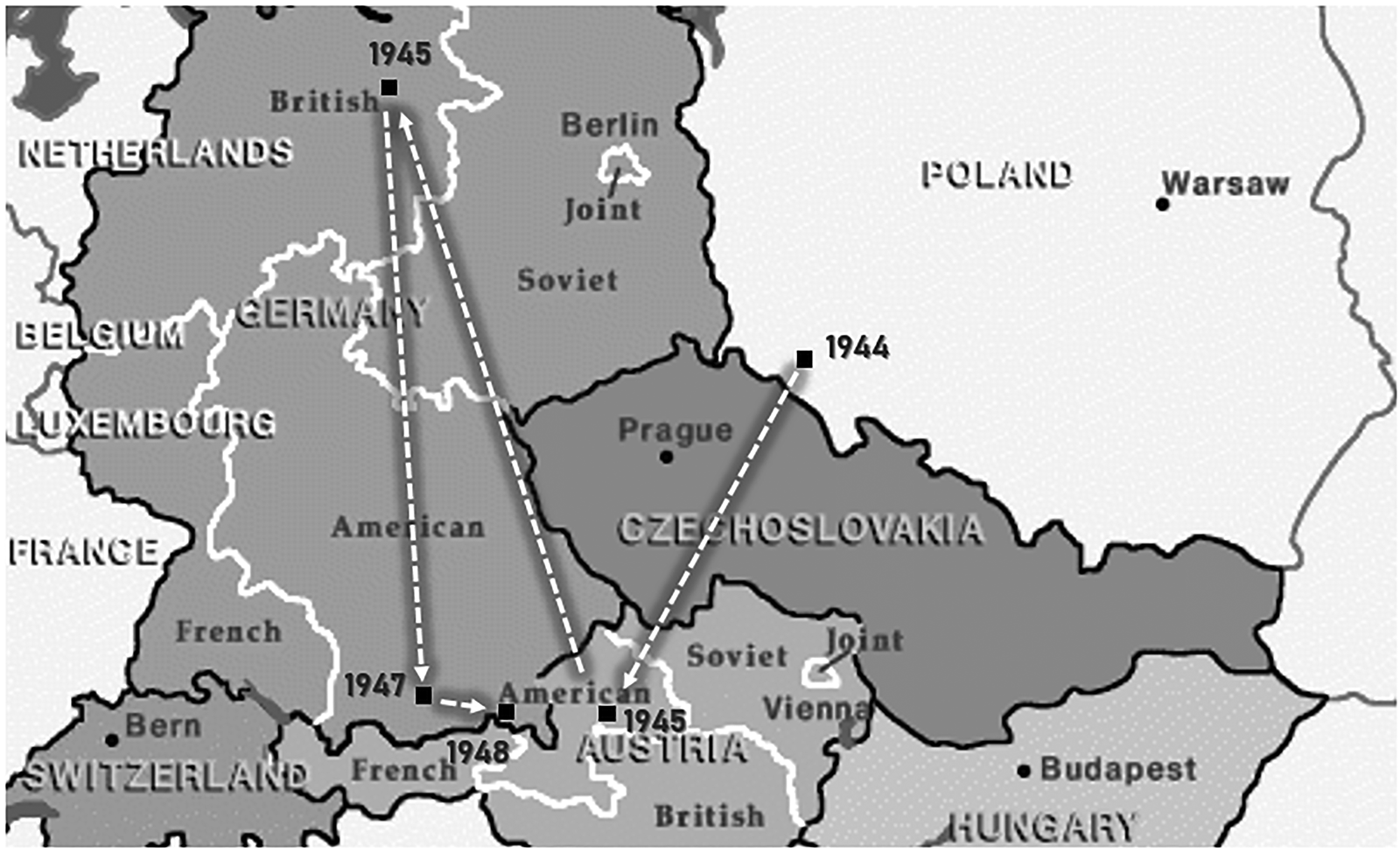

By mapping individual trajectories, I identified two patterns of displacement within the cohort that support this interpretation. First, many young survivors circulated between the British and American Occupied Zones in Germany. Zoltan and Karol, two Czechoslovakian brothers born respectively in 1930 and 1931, are representative of this pattern. After having been deported to Auschwitz, Wolfsberg and Ebensee, where they were liberated in May 1945, they travelled about 400 miles north to Bergen-Belsen, which had been turned into a DP camp.Footnote 58 They stayed there for two years, leaving the camp only for short periods to search for their parents. In 1947, they left Belsen to return south and ended up living in various DP camps and children's centres near Munich. They migrated to Canada the following year (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Listed locations of Zoltan and Karol L. (1944–1948).

Their trajectory is common within the cohort. Many travelled from southern Germany and Austria to the British occupation zone at the end of the war and then back to the American zone in 1947 or 1948. We can interpret this as a shift in individual and collective migration strategies. Their journey to Belsen may have been motivated by a hope of going on to Palestine, since the DP camp had become the centre of Zionist activism in Germany.Footnote 59 Conversely, their journey back to the south of Germany may indicate their willingness to explore new options since the American occupation zone was the waiting room for every survivor who wanted to go to North America, especially in 1947.

Such movements between DP camps and occupation zones are a common pattern within the cohort. They are good examples to support Suzanne Brown-Fleming's argument that it is necessary to go beyond individual refugee camps as a scale of analysis and to connect them with one another.Footnote 60 There are other potential explanations to be considered. The search for surviving relatives frequently motivated travels to nearby camps, but also longer journeys to other parts of the country and beyond. Discontent with the living conditions in the camp, rumours about better opportunities elsewhere, restlessness, boredom and a sense of adventure also shaped these trajectories.Footnote 61 The frequency of this pattern of travel from south to north to south within the cohort is likely to reflect how, because of various motivations that were sometimes entangled, the young survivors moved from one area to another to maximise their chances of leaving as quickly as possible.Footnote 62

A second recurring pattern within the cohort also supports the idea that many young survivors applied for a Canadian visa after being unable to get to Palestine. More than 100 were in northern Italy when they applied for a Canadian visa. The majority of them had complex trajectories that were similar to Samuel and Etta's.Footnote 63 Samuel C. and Etta C., both Polish and born in 1930, had been liberated in labour camps near Mauthausen. Shortly after their liberation, they crossed the Austrian-Italian border illegally and travelled to the south of Italy. They spent more than two years in several DP camps near harbours of the south-eastern Italian coast. In 1947 and 1948 respectively, the two orphans travelled back north and ended up living on the outskirts of DP camps near Milan and Turin.

Once again, this is a recurring pattern within the cohort that could represent a shift in migration strategies. The journeys of Samuel, Etta and many others to southern Italy very likely meant that they intended to leave for Palestine. Crossing the Austrian-Italian border was relatively easy, as authorities in French-occupied Austria turned a blind-eye to these circulations, and southern Italy was seen as a springboard to Palestine, especially in 1945.Footnote 64 The majority of the ships that sailed from Europe to Palestine between 1945 and 1948 left from Italian harbours in the south. Their trip back to the north may indicate how, after more than two years of waiting in the south, the difficulties of going to Palestine and increasing tensions there might have convinced the young survivors to explore other options closer to the American zone, which was now the main gateway out of Europe. Both patterns of circulation – south-north-south in Germany and north-south-north in Italy – highlight the fragmented nature of the young refugees’ journeys and the contingency of the decision making and motivations behind them.

Closed American Doors

As Michael Marrus, Françoise Ouzan and Beth Cohen have pointed out, the United States was another favoured potential destination among Jewish survivors. However, other than a few small-scale schemes, the borders of the country were almost entirely shut to unaccompanied Jewish youth in 1947 and 1948.Footnote 65 In this section, I demonstrate how challenges in entering the United States might have led many young survivors to reconsider their plans. Canada, which was widely perceived as a gateway to the United States, appeared to be one of the easier options.

At the end of 1945, the Truman directive suggested a possible relaxation of the country's immigration policy. Following the recommendations of the Harrison Report, the American president claimed that the ‘immensity of the problem of displaced persons and refugees [was] almost beyond comprehension’ and pled for his country to ‘do something to relieve human misery’.Footnote 66 In two years, about 23,000 DPs – two-thirds of them Jewish – migrated to the United States.Footnote 67 This provision, however, did not alter the country's long-term immigration policy and system of quotas.

In the autumn of 1947, the directive's quotas had been mostly filled and ‘infiltrees’ were ineligible, making a departure to the United States very unlikely. The Canadian Jewish representatives were frequently informed of unaccompanied children and adolescents who were about to leave for the United States but had their applications rejected, especially because of their age or nationality. Some young survivors contacted the CJC themselves, but such connections were predominantly made through close collaboration with American Jewish organisations working in Europe. In mid-August, the JDC sent to the CJC a list of Jewish children who were living in DP camps and were registered for departure to the United States but were no longer eligible, often because they had recently turned sixteen (the age limit for non-quota admissions under the Truman directive).Footnote 68 A few weeks later, one CJC representative expressed his hopes that several applications could be ‘easily transferred’ to the Canadian scheme.Footnote 69 Accordingly, many young survivors ended up applying for a Canadian visa after having their American visa rejected. Chronological age – in this case, being under or over sixteen – again crucially shaped their experiences of displacement.

The contingency of their departure for Canada is sometimes visible in the case files. For instance, Carol B.'s caseworker notes that the boy ‘was supposed to go to the US but was informed he was over age the day before the departure of his transport’.Footnote 70 A departure to Canada was sometimes seen as a way to get the child closer to surviving relatives in the United States. For instance, Peter L., a Hungarian boy whose grandparents had left for the United States, was not eligible for a non-quota admission. The caseworker in charge of his application wrote: ‘normal quota case should have to wait for years here alone. In Canada the family may at least visit him’.Footnote 71 Getting family members closer was a delicate position for the CJC representatives, as they feared the young survivors would use Canada as only a temporary refuge while they awaited entry to the United States. The American relatives often had to vow that they would not encourage and assist the young applicant to join them. For instance, in the case of Clara G., her Detroit-based uncle and aunt signed an affidavit stating that the girl was ‘to stay in Canada and not try and come into the United States’.Footnote 72 Such measures were often insufficient as many young newcomers went south shortly after their arrival in Canada, sometimes crossing the American border illegally.Footnote 73 In 1947 and 1948, Canada was regarded by many survivors as their safest option but was often considered a merely temporary destination. This mobility beyond arrival at their first destination confirms the difficulties in determining when exactly the refugee journey ends.

Shifting Possibilities

The limited ‘world of possibilities’ of the period, especially the difficulty of going to Palestine or the United States, can explain why the young survivors went to Canada. In this section, I argue that such an assumption is further reinforced by looking at the timeline of their departures (Figure 1). The number of departures dramatically decreased after October 1948, and the CJC had to end the scheme before reaching the additional quota of 250 visas that they had with difficulty obtained from the Canadian government (only 115 were used). This decline happened in the aftermath of the reopening of the American borders and during the stabilisation of the conflict in Israel. It could reflect how the context became less favourable to a departure to Canada with increased possibilities of migrating elsewhere.

In the United States, the passing of the DP Act at the end of June 1948 authorised 100,000 DPs entry over two years. Even though Jewish DPs were far from being automatically accepted, these new quotas directly impacted the Canadian scheme: after the second half of 1948, several cases were closed when applicants told the CJC they wanted to wait or find a closer intermediate destination such as France before going to the United States. The evolution of the situation in Israel had a similar effect. In August 1948, the Canadian Jewish representatives in Europe wrote to the Montreal headquarters about what ‘may be indicative of a new trend in the Orphans’ project’.Footnote 74 After being granted Canadian visas, a group of children in Salzburg appeared reluctant to leave. One boy even ‘sent back words that he had changed his mind about going to Canada, and that he had decided to go to Israel to where most of his friends were bound . . . it is the first time that there has been a group that showed any hesitancy or change of mind after my approval of their applications’. Many other applications were also cancelled in the following months. For instance, in September 1948, the visa for Gisela F. had to be sent back because the girl was now ‘unwilling to leave for Canada [and] would prefer to emigrate for Palestine when grown up’.Footnote 75 Israeli independence in May 1948, the ensuing military successes of the new state and the stabilisation of the conflict between October 1948 and March 1949 seem to have revived many young survivors’ plans to make Aliyah. Even though the potential influence of adults and of other children needs to be acknowledged, some individuals, like Gisela, voiced their desire to change their plans. This highlights that young survivors were involved to some extent in the decision making behind their journeys and in the reconfiguration of their migration strategies.

Although we must consider other factors to explain the drop in the number of departures to Canada in the fall of 1948 and the winter of 1949 – notably the increased difficulty of leaving Eastern European countries amidst growing Cold War tensionsFootnote 76 – political changes in the United States and Israel undoubtedly affected the Canadian scheme. Its outcomes may have been dramatically different if, for instance, the Canadian federal government authorisation had not happened in April 1947 but a few months before or after. Before April 1947, many young survivors might have decided to stay because of better prospects in their country of residence, especially access to housing and education. Afterward, they might have chosen another destination than Canada, with increased possibilities (or at least greater hopes) of migrating to the United States or Israel. This represents an important reminder of how crucial timing is in shaping refugee journeys and migration trajectories more generally.

It also highlights how, by mapping the possibilities and constraints of an individual, one can formulate hypotheses about the decision making and motivations behind their journey. Addressing the ‘interrelatedness’ of structure and agency when examining migration trajectories is essential.Footnote 77 People on the move have their ‘world of possibilities’ shaped by developments both in their country of residency and in potential countries of transit and arrival, but they navigate this ‘world’ differently. In the present case study, mapping individual trajectories allowed me to identify patterns of displacement within the cohort and highlight how many young survivors circulated between DP camps and occupation zones, travelled to areas that were widely regarded as ‘springboards’ among Jewish survivors, simultaneously applied for several visas, or postponed their departure to wait for further developments elsewhere. Retracing the trajectories of Dow across central Europe, Zoltan and Karol in Germany, or Samuel and Etta in Italy strikingly reveals the often-forgotten complexity of young Holocaust survivors’ experiences in the immediate aftermath of the war. Their trajectories highlight the need to look beyond existing coherent narratives of displacement and are a useful reminder for migration scholars of the broader danger of considering displacement only in terms of a point of departure and a point of arrival. The fragmentation of these journeys and their formative and transformative nature cannot be ignored.Footnote 78 Many of the young survivors pursued other options, tried to return to the life they had before the war, or started again elsewhere before applying for a Canadian visa.

However, as has been acknowledged earlier, the influence of others is crucial for young people on the move. In the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, many young survivors grew up in collective spaces, such as children's homes and Kibbutzim, where opportunities for individual decision making were limited. Kibbutzim in particular were based on subtle and sometimes more coercive peer pressure.Footnote 79 It is possible that Samuel and Etta travelled from Austria to southern Italy as part of one of these Kibbutzim. They might also have been part of groups sponsored by Bricha (‘flight’ in Hebrew), a Zionist organisation that assisted approximately 200,000 Jews to go to Palestine.Footnote 80 Even though they indicated that they had travelled alone, Zoltan and Karol could have moved from Bergen-Belsen to the American occupation zone as part of a transport set up by a Jewish aid organisation, or been pushed by surviving relatives to do so, as teenage boys were often part of larger familial migration strategies.Footnote 81

The influence of adults on the journey sometimes appears in the correspondence of CJC officials who often worried about their potential negative impact on the young survivors’ decisions to go to Canada. After the unexpected change of mind of the group of children in Salzburg, one CJC representative argued: ‘some of it, I think, is due not only to personal feelings as in the case of the boy who was going to Israel, but also to the general opinion in the camps on the question of going to Israel’.Footnote 82 She repeatedly advocated for sending applicants to children's facilities as quickly as possible in order to protect them from peer pressure and separate them from ‘collective Zionism’. Her worries confirm the major role of networks, relatives, social workers and aid organisation representatives in shaping the journeys of young people and influencing their decision making. Like most young refugees today, many were separated or unaccompanied but not actually alone.

Conclusion

The case files and the sometimes uncertain narratives that emerge from them are valuable. Through them, this article has contributed to unravelling the diversity and complexity of young Holocaust survivors’ experiences of displacement. Documenting forgotten trajectories, like those of Max E. or Etta C., challenges the current perception of ‘refugeedom’ in the aftermath of the Second World War that predominantly focuses on a local scale of analysis (the experiences of refugees in DP camps) or linear displacement (from Eastern Europe to Western Europe, from Central Europe to Israel, from Western Europe to North America, etc.). It helps to restore the fragmented and unstable nature of the young survivors’ journeys and the contingency of the decision making behind them. By doing so, this article has nuanced teleological and simplistic readings of Holocaust survivors’ migration and especially demonstrated how Canada was often a second-choice destination.

One of the main challenges for scholars interested in children and youth is to find the right balance between overestimating their agency (and erasing the specificity of their experiences as young people) and completely ignoring their capacity to be actors in their everyday lives. The notion of ‘worlds of possibilities’ can offer an alternative to the concept of agency and help better understand young people's experiences of displacement. In this article, such a framework has allowed me to identify potential factors that shaped the young survivors’ trajectories by mapping what was and was not available to them. These include, on the one hand, increasingly hostile immigration and refugee policies in several Western European countries, the gradual withdrawal of American Jewish relief organisations and the subsequent financial difficulties of European Jewish organisations; and, on the other hand, the limited possibilities of migrating to Palestine or the United States. These factors all contributed to shaping the young survivors’ ‘world of possibilities’ in ways that were favourable to a departure to Canada. This situation changed in late autumn 1948 and winter 1949 with increased opportunities to migrate elsewhere and growing difficulties in leaving some countries. These developments in the young survivors’ countries of residency and in their potential countries of transit and arrival shaped their ‘worlds of possibilities’.

Recreating these ‘worlds’ helps us to formulate hypotheses about the decision making and motivations behind the refugee journeys. Many questions remain unanswered but administrative records can still give voice to the individual and collective experiences of refugees. By replacing both outstanding trajectories and recurring patterns of displacement in a broader ‘world of possibilities’, this article has foregrounded the necessity to further examine these journeys. They are particularly pertinent since the experiences of many young Holocaust survivors – the fragmented nature of their journeys and the mixed motivations behind them, the importance of networks, the overall hostile environment they navigated and, moreover, their voicelessness both as young and displaced people – strongly resonate with those of today's young people on the move.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by the support of the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah. I am grateful to Tim Cole, Peter Gatrell, Mona Gleason, Laura Hobson-Faure and Célia Keren for their insightful comments, as well as to Jonathon Catlin and Stéphanie Rinaldi for their thorough copyediting. I am also grateful to the three anonymous reviewers whose thought-provoking suggestions have greatly strengthened this article. Previous versions of this text have been presented at the ‘Microhistories of Flight from Nazi Germany’ conference (University of Luxembourg) in January 2018, the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute research seminar (University of Manchester) in October 2018, the Histories and Historiographies of the Shoah seminar (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales) and the ‘Lessons and Legacies’ conference in November 2018 (Washington University in St Louis). I would like to thank all the organisers and participants for their feedback, especially Roisin Read, Marion Kaplan, Anna Hájková, Claire Zalc, Nicolas Mariot and Sarah Gensburger.