Introduction

For children who must be removed from their birth parents, placement with an adoptive family provides stability, safety, and a nurturing environment (Brodzinsky & Palacios, Reference Brodzinsky and Palacios2023; Palacios et al., Reference Palacios, Adroher, Brodzinsky, Grotevant, Johnson, Juffer, Martínez-Mora, Muhamedrahimov, Selwyn and Simmonds2019). Yet each child adopted from public care has a complex and unique early life history that may increase their risk for developing mental health problems. Most children taken into care are removed from their birth families due to maltreatment, neglect, and/or household dysfunction (Palacios et al., Reference Palacios, Adroher, Brodzinsky, Grotevant, Johnson, Juffer, Martínez-Mora, Muhamedrahimov, Selwyn and Simmonds2019). Additionally, all adopted children experience loss of their birth family and encounter varying degrees of instability within their living arrangements before they are placed for adoption (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Litrownik and Landsverk2000). These early experiences, that for some children are possibly compounded by exposure to substances in utero and a genetic risk for mental health problems, place them at greater risk of developing enduring mental health problems (Dekker et al., Reference Dekker, Tieman, Vinke, van der Ende, Verhulst and Juffer2017; Paine et al., Reference Paine, Fahey, Anthony and Shelton2021).

Adopted children’s mental health

Adopted children’s developmental outcomes can vary widely (Grotevant & McDermott, Reference Grotevant and McDermott2014). Adoptees are more likely to have difficulties in domains of cognitive functioning, academic attainment, and to experience more socioemotional and mental health problems compared to non-adopted children (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Waters and Shelton2017). However, they tend to out-perform children who remain in vulnerable families or in institutional care; similar findings are suggestive of the protective role of adoptive families (Askeland et al., Reference Askeland, Hysing, La Greca, Aarø, Tell and Sivertsen2017; Sonuga-Barke et al., Reference Sonuga-Barke, Kennedy, Kumsta, Knights, Golm, Rutter, Maughan, Schlotz and Kreppner2017; Van den Dries et al., Reference Van den Dries, Juffer, Van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg2009; Vinnerljung & Hjern, Reference Vinnerljung and Hjern2011). Yet countries vary in the legislative and regulatory use of adoption and children’s outcomes differ according to the nature of the adoption context (Dekker et al., Reference Dekker, Tieman, Vinke, van der Ende, Verhulst and Juffer2017). For example, countries differ according to the prevalence of intercountry versus domestic adoption, of time spent in institutional care, with foster families, or in kinship care, and the extent to which contact between the adoptee and their birth family is allowed (Palacios et al., Reference Palacios, Adroher, Brodzinsky, Grotevant, Johnson, Juffer, Martínez-Mora, Muhamedrahimov, Selwyn and Simmonds2019). Context-specific research is therefore essential for informing policy and practice (Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, Sonuga-Barke, Beckett, Castle, Kreppner, Kumsta, Schlotz, Stevens, Bell and Gunnar2010).

In the UK, where domestic adoption is prevalent, adopted children are at greater risk for developing mental health problems than the general population and are over-represented in clinical settings (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Paine and Shelton2019; DeJong et al., Reference DeJong, Hodges and Malik2016). Children who are older at the time of their adoption are particularly at risk, being likely to have experienced a correspondingly longer exposure to maltreatment and neglect (DeJong et al., Reference DeJong, Hodges and Malik2016; Neil et al., Reference Neil, Morciano, Young and Hartley2020). Older children are also more likely to have spent longer in foster care, which has different associated risk factors; some children may experience instability via multiple moves in care or poor-quality foster care (Meakings & Selwyn, Reference Meakings and Selwyn2016; Newton et al., Reference Newton, Litrownik and Landsverk2000) and, upon adoption, some children may find separation from their foster carer very distressing (Neil et al., Reference Neil, Morciano, Young and Hartley2020). Although UK longitudinal research is limited, findings from our cohort study demonstrated that adopted children’s mental health problems remained consistently high 4-years post-adoption (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Fahey, Anthony and Shelton2021). When children’s trajectories of internalizing (emotional) and externalizing (behavioral) problems were modeled according to child age, children showed an accelerated increase in problems into middle childhood that differed as a function of their exposure to pre-adoptive risk factors (age at placement, days in care, and number of adverse childhood experiences) (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Perra, Anthony and Shelton2021). However, our ability to chart trajectories into the school years was limited due to the young age of the sample. Therefore, the overarching aim of this study was to model time-related changes in adopted children’s internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems from early to later childhood, now that children in the sample have all started school.

School transitions

Ecological perspectives emphasize that children develop within multiple, nested contexts, from the proximal interpersonal environment to the broader societal and cultural milieu (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1977, 1998). Starting school represents a major life transition for all children (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Reference Bronfenbrenner and Morris2007; Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1977; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, Reference Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta2000) and is an ‘agent of developmental change’ (Pianta et al., Reference Pianta, Steinberg and Rollins1995). Entry to school offers new experiences and challenges. Children must navigate relationships in a wider network of peers and with new adult authority figures. They are also expected to adjust to the demands of the new environment including contending with novel goals, routines, and expectations of increased autonomy. According to the Ecological and Dynamic Model of Transition (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, Reference Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta2000), a child’s adjustment in the school transition is determined by child characteristics (e.g., readiness, social and cognitive skills), direct (e.g., class size, child relationships) and indirect (e.g., parent-teacher communication) influences that interact through transactional processes. Evidence demonstrates that a good start at school is associated with positive academic and social outcomes (Dockett et al., Reference Dockett, Griebel and Perry2017).

The degree and types of challenges adopted children may experience in their transition to school will depend on each child’s individual pre- and post-adoption experiences (Goldberg & Grotevant, Reference Goldberg and Grotevant2023; Soares et al., Reference Soares, Barbosa-Ducharne, Palacios and Fonseca2017). Yet many adopted children find the social and academic context of school more challenging than their peers (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Waters and Shelton2017). Possibly, some of these difficulties may be underpinned by problems with processing social and emotional information (Paine et al., Reference Paine, van Goozen, Burley, Anthony and Shelton2023), and with cognitive abilities (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Burley, Anthony, Van Goozen and Shelton2021; Wretham & Woolgar, Reference Wretham and Woolgar2017) that contribute to success in school settings (Boivin & Bierman, Reference Boivin and Bierman2013; Sabol & Pianta, Reference Sabol and Pianta2017). Although numerous studies have documented child, parent, and teacher views about school experiences in the context of adoption (Crowley, Reference Crowley2019; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Frost and Black2017; Goldberg & Grotevant, Reference Goldberg and Grotevant2023), little is known about adopted children’s mental health trajectories through this transition. Moreover, we do not yet know whether age at placement is associated with this transition. Not only do prolonged experiences of early adversity place children at risk for more social, emotional, and cognitive difficulties (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Burley, Anthony, Van Goozen and Shelton2021; Paine et al., Reference Paine, van Goozen, Burley, Anthony and Shelton2023), but according to Life Course Theory, the timing of multiple transitions has consequences for development (Elder et al., Reference Elder, Johnson and Crosnoe2003; Elder, Reference Elder1998). For children adopted in later childhood, experiencing the transition of adoption alongside or in temporal proximity to their transition to school, may have important implications for their mental health.

The present study

To our knowledge, no study has investigated adoptees’ trajectories of mental health problems across development as children make the transition to formal education. We harnessed six waves of data from a UK longitudinal cohort study that followed children and their adoptive families over eight years post-placement. Our first aim was to investigate trajectories of adopted children’s internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems by tracking age related patterns of change from early childhood to early adolescence. Our second aim was to investigate the impact of child (age at placement, sex, number of moves, and adverse childhood experiences) and family (socioeconomic status) factors on children’s trajectories. We hypothesized that age at adoption, number of moves and number of adverse childhood experiences would be associated with increasing and accelerated mental health problems (Nadeem et al., Reference Nadeem, Waterman, Foster, Paczkowski, Belin and Miranda2017; Paine et al., Reference Paine, Perra, Anthony and Shelton2021; Vandivere & McKlindon, Reference Vandivere and McKlindon2010). Our third aim was to investigate the effect of the transition to school on children’s trajectories of internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems. Given the changes and new challenges brought about by the school transition (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, Reference Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta2000) we hypothesized a discontinuity in the rate of change and elevation in internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems after school entry.

Method

Design

We used data from the Wales Adoption Cohort Study; a prospective longitudinal study of the early support needs and experiences adopted children and their families; see (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Perra, Anthony and Shelton2021) for more details of the study and (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Perra, Anthony and Shelton2021) and (Palacios et al., Reference Palacios, Adroher, Brodzinsky, Grotevant, Johnson, Juffer, Martínez-Mora, Muhamedrahimov, Selwyn and Simmonds2019) for background of adoption in the UK. Local authority adoption teams across Wales were asked to send out letters on behalf of the research team to every family with whom they had placed a child for adoption between July 1, 2014 and July 31, 2015. A strategy of rolling recruitment was used, with invitation letters timed to arrive with the families several weeks after the placement began.

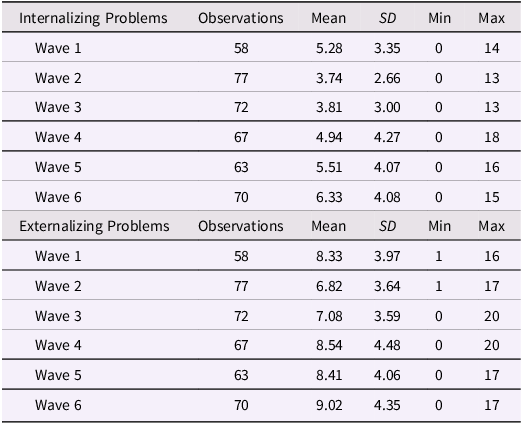

Ninety-six families returned the initial questionnaire at 5 months post-placement and were followed up longitudinally over 6 time points over 8 years post-placement. The present study focuses on the questionnaire follow-ups that took place at approximately 5–, 21–, 36–, 48–, 60– and 96-months post-placement (Waves 1 to 6 [W1 to W6] respectively). Of the 96 families that participated in the study at W1, 81 (84.4%) participated at W2, 73 (76.0%) at W3, 68 (70.8%) at W4, 63 (65.6%) at W5, and 70 (72.9%) participated at W6. The present study focuses on N = 92 (95.8%) families who completed information about children’s mental health on at least one wave out of the six waves of data collection (see Table 1). Among these families, n = 28 (30%) had provided data in all six waves of data collection, and further n = 28 provided data at five of the six survey points. Only n = 4 (4%) and n = 9 (10%) provided information on one and two waves of data collection respectively (see Supplementary Material S1 for more details). In the Plan of Analysis section, we make a case for including all these participants in the analyses to minimize bias. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses indicated that the pattern of results did not change when participants who completed less than three waves were excluded (see Supplementary Material Section 3).

Table 1. Means, SDs, and ranges of Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) internalizing and externalizing by wave of data collection

Note. The number of the sample with valid data was lower in W1 compared to W2 because children under 2 years of age were too young to have an SDQ completed by a parent.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from parents and ethical permission for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee for the School of Psychology at Cardiff University and permission to access the social work records was obtained from the Welsh Government via consultation with the Heads of Children’s Services Group and senior adoption managers across the country.

Participants

Of the 92 children who were reported on by their parents in the longitudinal follow-up questionnaires, 45 (48.9%) were female, and were placed for adoption at a mean age of 2.97 years (SD = 2.10, range 0 to 9.04 years). Children spent a mean of 541.80 (SD = 611.01, range 0 to 2344) days with their birth parents and a mean of 544.71 (SD = 285.01, range 207 to 1401) days in care. Children experienced a median of 1 move (IQR = 1 to 3) whilst in care and a median of 3 adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (IQR = 0 to 5) out of 10 categories (Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998) including childhood abuse (emotional, physical, or sexual), neglect, and household dysfunction (domestic violence, parental separation, substance abuse, alcohol abuse, mental illness, or incarceration) evidenced from social worker records for each child (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Perra, Anthony and Shelton2021). Twenty-six children (28.3%) were adopted as part of a sibling group.

Parents were a mean age of 40.61 (SD = 7.06, range 22 to 62) years at the time of adoption, and the majority (97.8%, n = 90) identified as white British. Most parents were in a heterosexual relationship (81.5%, n = 75), 5.4% (n = 5) were in a same sex relationship and 13% (n = 12) were single adopters. At the W1 assessment, there were a median of 4 (IQR = 3 to 4) people living in the household and most informants were in either full-time or part time paid work (n = 68, 73.9%). Gross family income and education levels were substantially higher than the UK average (ONS, 2019), where 13% earned more than £75,000 per year and 38% had postgraduate degrees.

Characteristics of the 92 adopted children in the present study were compared to those of all children placed for adoption in Wales the same time window (N = 374), by reviewing Child Adoption Reports for all children adopted between July 2014 and July 2015 in Wales (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Paine and Shelton2019). The sample was representative of children placed for adoption in this thirteen-month period regarding child sex, age at adoption, and past experiences of abuse and neglect (all ps > .05). Attrition analyses showed no differences in sociodemographic characteristics (child sex and age, parent age, relationship status, education, employment status, income, and ethnicity) between those who participated in W1 and W6 of the study (all ps > .05).

Procedure

Questionnaires

At each time point, families completed a questionnaire concerning sociodemographic information, pre- and post-adoption experiences, the child and parent’s mental health, and adoptive family relationships. Where groups of siblings were placed together, parents were asked to report on the eldest child in the placement to overcome the problem of dependencies in the data from children within the same family. The eldest child was selected to maximize the likelihood that the focal child would be in age range for measures to be completed for them. Questionnaires were completed by either a mother (88.0% at W1, 87.5% at W2, 97.1% at W3, 92.6% at W4, 93.0% at W5, 88.6% at W6), father or non-binary parent. It was encouraged that the questionnaires should be completed by the same parent at each wave, so all families who provided follow-up questionnaires returned at least one completed by the same informant. A remuneration £20 gift voucher was sent to the family upon receipt of the questionnaire at each time point.

Measures

Child internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems

Adoptive parents completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, Reference Goodman1997) at each wave of the study. We used internalizing symptoms (sum of emotional and peer problem scales) and externalizing problems (sum of conduct and hyperactivity scales). A higher score is indicative of more problems for all subscales (where children could score a maximum of 20 in each of these two subscales). The internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems scales had acceptable to good levels of internal consistency across all time points (α values ranged from .60 to .84).

On average, 4.42 SDQ assessments were completed for the 92 children included in data analyses (SD = 1.52): Only 4 children (4%) had a single SDQ completed, while 28 (30%) had five SDQs completed across the six waves of data collection, and the same number, 28, had SDQs completed in each of the six waves of data collection. Children’s age at the time of assessment varied depending on the timing of their adoption. The average age of the sample with valid data was lower in W2 compared to W1 because children under 2 years of age were too young to have an SDQ completed by a parent. As we illustrate in the Plan of Analyses, the time variable used to model change is children’s age, rather than the wave of data collection.

Socioeconomic characteristics

Adoptive parents’ sociodemographic information was collected at W1. A general index family socioeconomic status (SES) was created using Principal Component Analysis using Stata 13 (StataCorp, 2013). The indicators included were being a couple, working full-time, and level of family gross income, see (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Perra, Anthony and Shelton2021) for information.

Plan of analyses

A detailed description of our analyses and formal description of the models and their parameters is presented in the Supplementary Materials. To investigate trajectories of internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems across time, we applied multilevel growth curve models (also known as random effects regression models) using Stata 17 (StataCorp, 2021). The multilevel growth curve approach allowed the modeling of change in the outcomes as a function of participants’ age, rather than the scheduled wave assessment. To facilitate data interpretation, we centered age at 3 years, so that the intercept in the models represented the expected average outcome score at 3 years of age. Estimation of parameters for participants with incomplete waves was carried out using Maximum Likelihood methods where data were assumed to be Missing at Random (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Bartlett, Morris, Wood, Quartagno and Kenward2023). These methods provide more robust and reliable estimates compared to traditional methods such as listwise deletion or average-value imputation (Widaman, Reference Widaman2006). Trajectories of change over time were thus estimated on the full sample with complete and incomplete waves of data collection. However, we also ran sensitivity analyses that confirmed the pattern of results observed when we excluded participants who had completed fewer than three waves of data collection (see Supplementary Material, Section 3).

We modeled a linear, quadratic, and a cubic growth curve for internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems, respectively, comparing these models using the Likelihood Ratio (LR) test. The selected models were then refined by considering the plausibility of accessory parameters (e.g., covariance between intercept and slope residuals). After the best-fitting growth model was selected, covariates were added, thus fulfilling the second study aim. To allow for an asymmetric distribution of SES component scores, we transformed these scores using their square, then standardized the transformed scores to facilitate parameter interpretation in data analyses. A few cases did not provide information on model covariates (number of moves before placement and total number of ACEs). To avoid excluding these cases from analyses and introduce potential bias, we used multiple imputation (MI). MI methods allow to substitute missing data with plausible imputed values by sampling from a predictive distribution based on the observed data. Furthermore, the sampling process allows to account for uncertainty by creating multiple imputed datasets: parameter estimation accounts for this uncertainty by pooling estimates across the imputed datasets. In the analyses, we created 250 imputed datasets using multiple imputation chained equation methods, then used Rubin’s rule to integrate results from these datasets with imputed values. More details concerning the methods are provided in Supplementary Material Sections 1 and 2.

Finally, we tested whether children’s internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems followed different trajectories before and after entry to school (i.e., the September following their fourth birthday). For this aim, we used B-spline models (where the B stands for basis). B-spline models (henceforth, called spline models) allow modeling complex trajectories of change over time. They do so by splitting the time variable into different intervals. Within these intervals, different parameters and polynomial functions specify interval-specific patterns of change. For example, the outcome may display a linear increase in the first interval, followed by a quadratic accelerated decrease in the second interval. To describe the pattern of change across the whole study with a single continuous function, these polynomials are constrained to meet at pre-defined fixed points, called knot-points. This effectively means that interval-specific parameters are weighted to exert increasing influence as they reach their corresponding knot-point. Each parameter exerts an influence that is localized within a specific period: as time moves towards other periods and knot-points, other parameters are gradually “turned on.” In this way, spline models allow describing large variations across a study. This feature is particularly useful in modeling patterns of change that diverge or vary around key events or experiences.

In our study, a key event of interest was children’s entry to primary school. Therefore, we split the time variable into two intervals that represented the trajectory of children’s SDQ scores before and after school entry. Therefore, we used spline models to describe patterns of change in internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems across developmental periods characterized by a pivotal event, school entry. In our models the knot point was the exact age when each child started school. A detailed and formal presentation of the models is provided in Supplementary Material Section 4. The spline models only included n = 62 children who had provided data before and after starting school: The remaining 30 only provided data after they had already started school and were excluded from these analyses.

Since the n = 62 included in the Spline analyses had provided data before the transition into primary school, the participants included were significantly younger than the n = 30 excluded from the Spline analyses; average age at the start of the study 2.17 (SD = 1.03) and 6.07 years (SD = 1.10), respectively. Children in this subsample were also significantly younger at the time of placement compared to those excluded, average 1.18 (SD = 1.04) and 5.56 (SD = 1.13), respectively, and had been exposed to a significantly fewer number of ACEs, average 1.77 (SD = 2.56) and 5.00 (SD = 2.00) respectively. However, the participants included in the Spline analyses were not significantly different from those excluded considering number of moves before placement (average 1.94 [SD = 2.08] and 2.19 [SD = 1.50], Incidence Risk Ratio = 0.88, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.31) and their SES standardized score (average 0.05 [SD = 0.94] and -0.11 [SD = 1.14] respectively, t[90] = -0.70, p = 0.48). Overall, the subsample included in the Spline analyses represented a sample of younger adoptees that had been placed earlier and had been exposed to relatively fewer adverse childhood events.

Results

Descriptive statistics

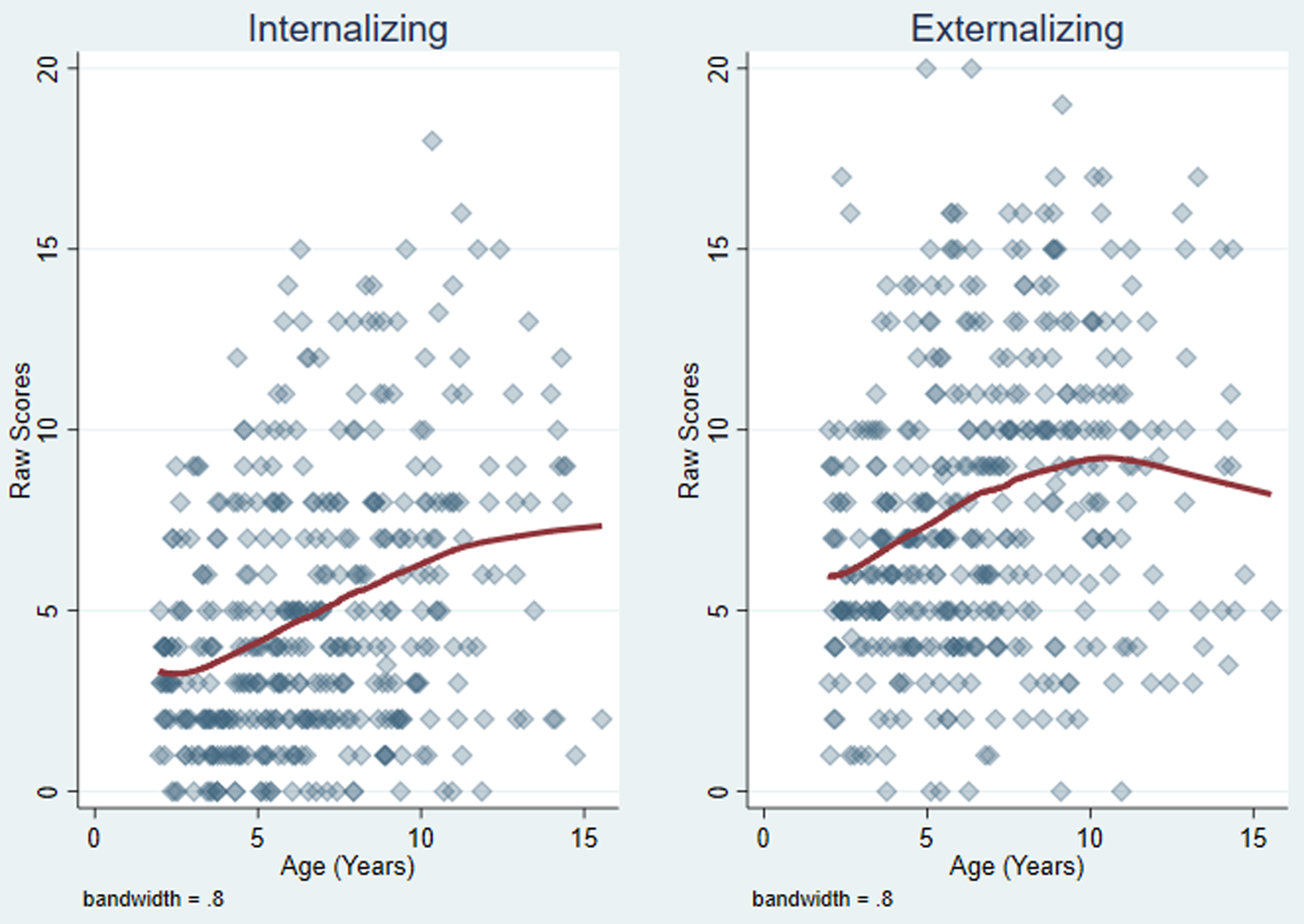

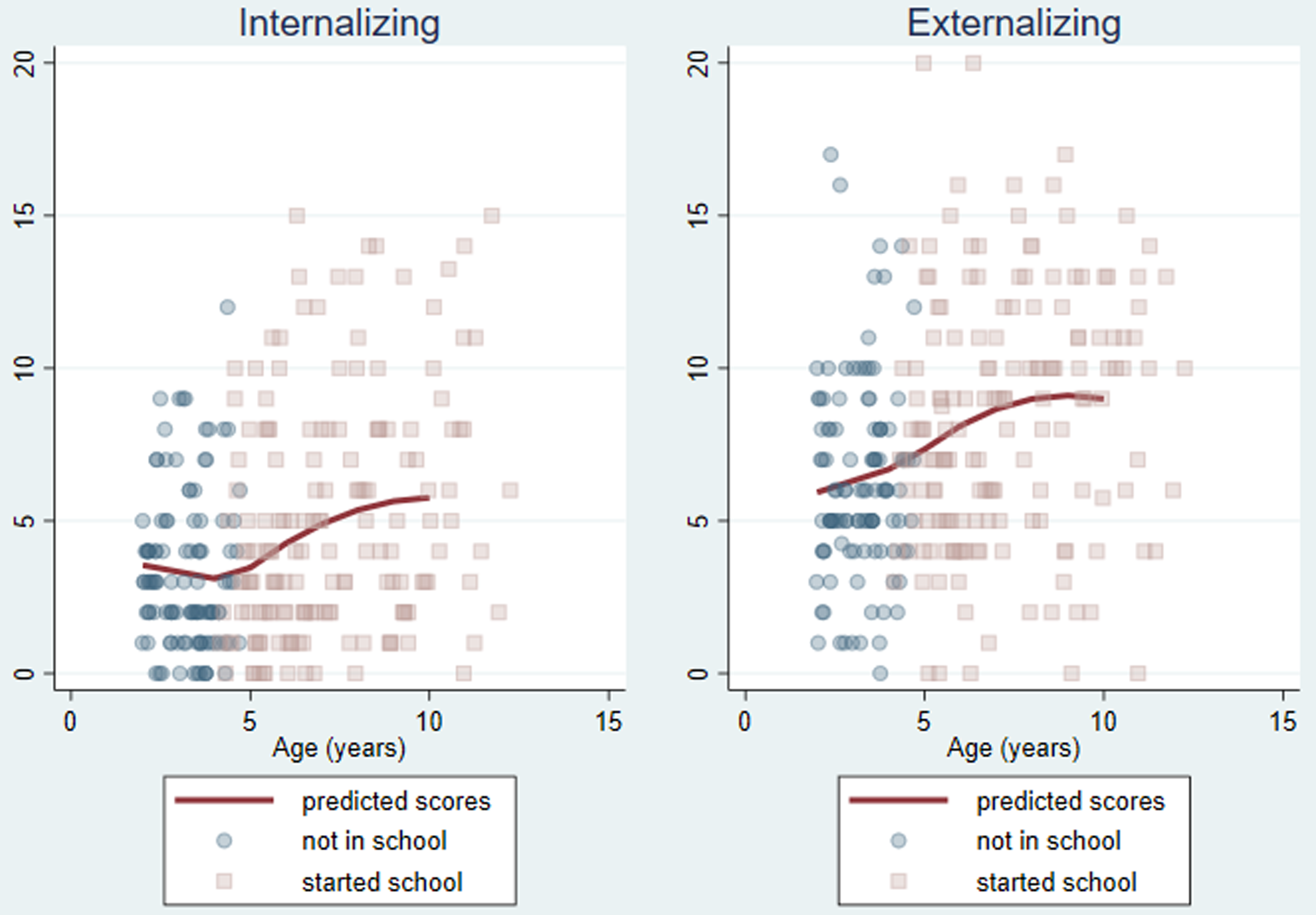

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. A lowess smoother function to represent internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems by children’s actual age is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Scatter plot and lowess smoother function across children’s age by Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire scale. Note. The diamond blue markers indicate the observed outcome scores by age across the N = 92 participants. Markers are transparent, therefore increasing opacity indicate increasing clustering of observations. The red lines indicate lowess smoother functions of outcomes by age (bandwidth = 0.80).

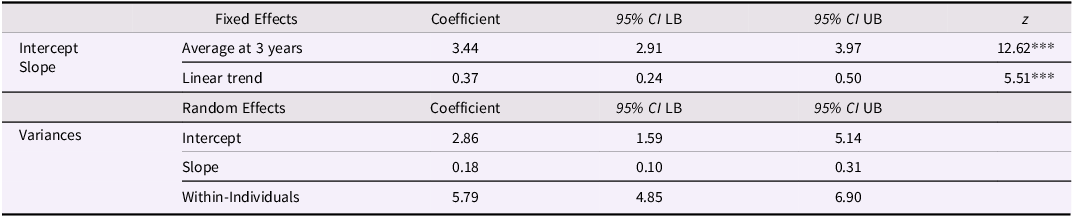

Trajectories of internalizing symptoms

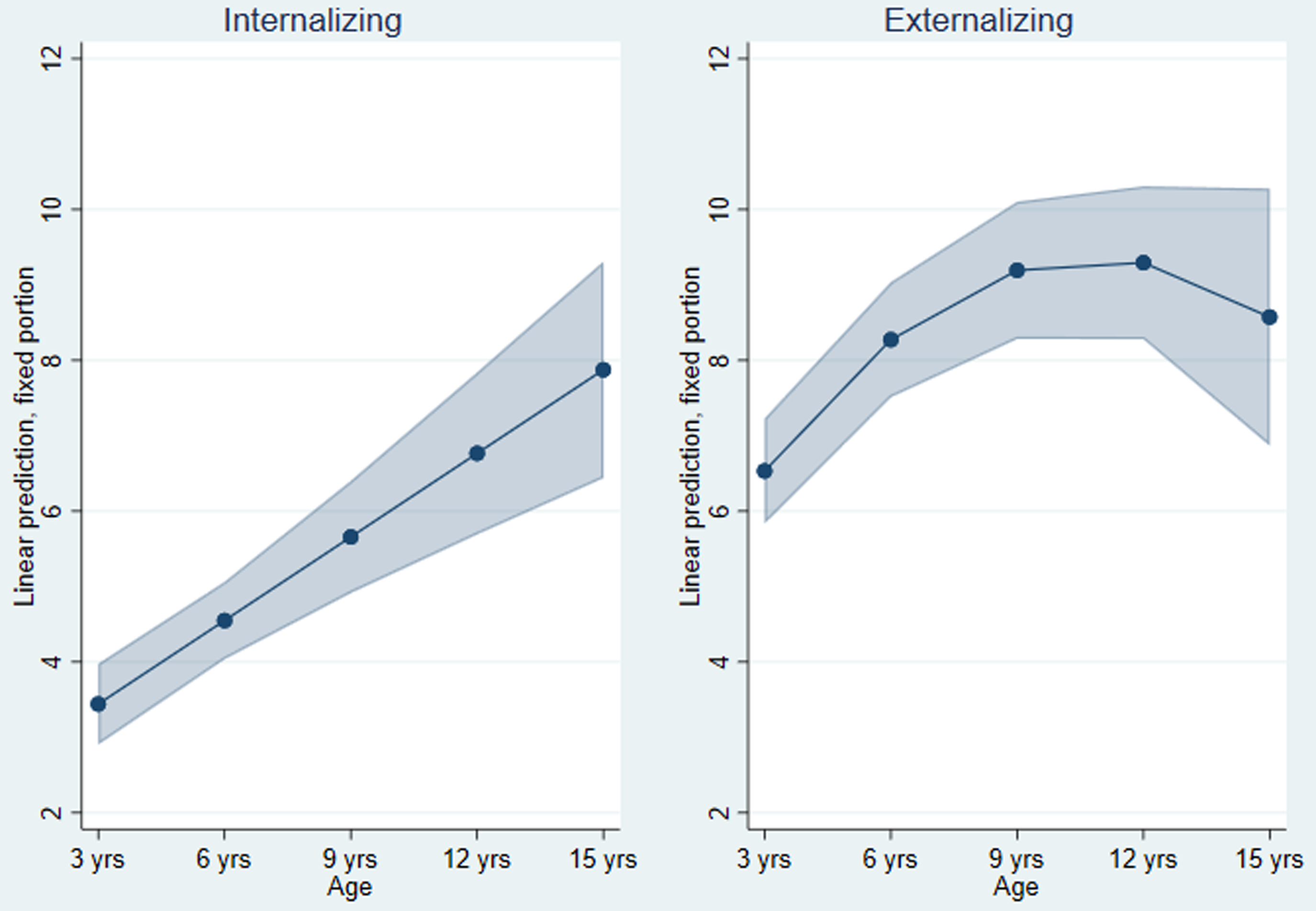

A multilevel regression indicated a significant linear increase in internalizing symptom scores across age. Adding polynomial slopes (quadratic, and cubic) did not improve model fit. More detailed results are reported in Supplementary Material Section 3. The final model retained inter-individual variability around the sample initial status (intercept) and rate of change (slope), but not associations (covariance) between the two. The parameters of the linear multilevel regression of internalizing symptoms on age are reported in Table 2a, while Figure 2 reports the predicted scores in the internalizing symptoms according to these parameters. The model provided a significant fit to the data, Wald χ 2 (1) = 30.33, p < .001, and indicated that internalizing symptom raw scores increased by 0.37 units every year on average (95% CI 0.24 to 0.50).

Figure 2. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems fitted trajectories by age. Note. Trajectories based on the parameters of multilevel growth models reported in Table 2a and Table 3a. The blue dots and lines represent the scores predicted by the models. The shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals of predicted scores.

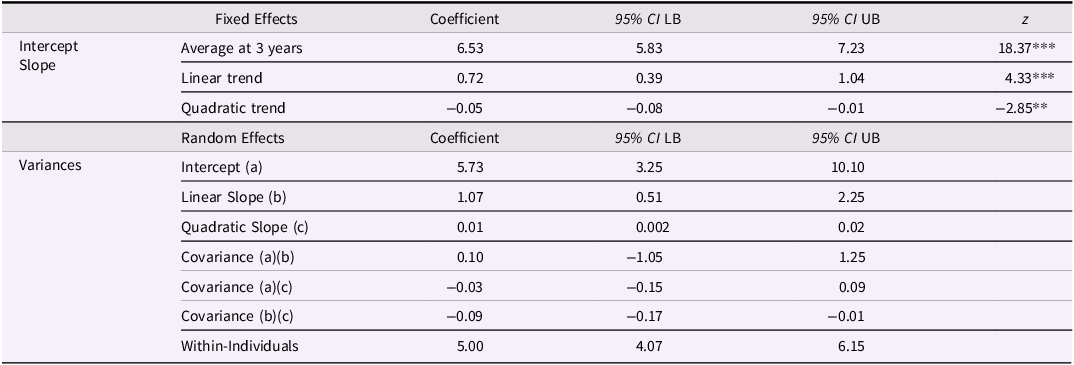

Table 2. (a) Parameters of the unadjusted multilevel growth curve of internalizing symptoms

Table 3. (a) Parameters of the unadjusted multilevel model of externalizing problems

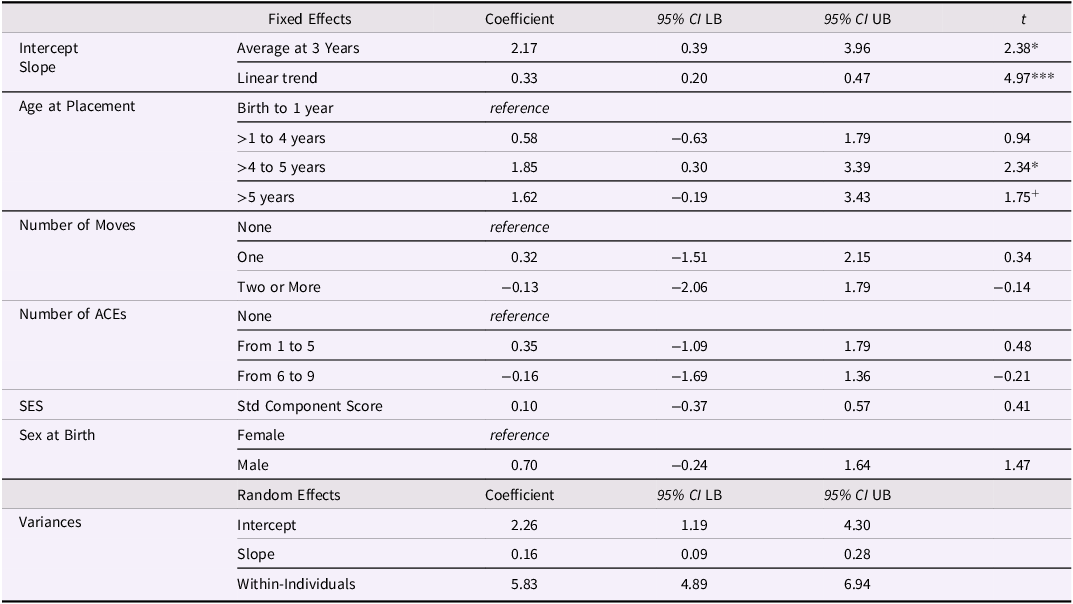

The results of a subsequent model where we entered the main covariates are reported in Table 2b. The model, run on 250 imputed datasets (see Plan of Analyses), indicated a good fit to the data, F (10, 919297.0) = 4.26, p < .001. In Supplementary Material Section 3 we also report that the analyses did not indicate differences in the rate of change according to covariates sex, family SES, or age at time of placement. The final adjusted model reported in Table 2b indicates no significant associations between average internalizing symptom scores and sex or SES. While there were no significant associations between the average internalizing symptoms and indicators of previous adversity such as the number of moves and the number of ACEs, there was a significant association between internalizing symptom scores and age at time of placement: the results indicated that, compared to children who were placed within the first year of life, those that went into placement around the age when they started school (age >4 to 5) displayed a significant 1.85-unit increase in average internalizing symptom scores. There was also a marginal difference between those that went into placement at birth and those that went into placement aged over 5 years, whereby the latter were predicted to show a 1.62-unit increase in internalizing symptom scores, t = 1.75, p = 0.079, see Table 2b.

Table 2. (b) Parameters of the adjusted multilevel growth curve of internalizing symptoms

Note. 95% CI: 95% Confidence Intervals; LB = Lower Bound; UB = Upper Bound. + p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

The results of the adjusted model (Table 2b) also indicated a relatively high level of internalizing symptom scores variability within individuals. Estimated variance within-individual once we controlled for covariates and change over time was approximately 6 points (5.83, see Table 2b).

Overall, the results indicated a significant linear increase in internalizing symptoms across age, but the results also indicated a considerable amount of inter-individual variation in these trajectories, as well as within-individual variation across time. The only covariate that displayed significant associations with this variable was age at time of placement: compared to children that were in placement within their first year of life, those that went into placement aged between >4 to 5 years displayed higher internalizing symptoms on average.

Trajectories of externalizing problems

The analyses suggested that externalizing problem scores followed a quadratic trajectory: adding a quadratic trend according to participants’ age increased model fit significantly, LR χ 2 (4) = 29.23, p < .001. Furthermore, results suggested significant inter-individual variation in the quadratic slope. The final model and its parameters are reported in Table 3a, while in Figure 2 we report the predicted externalizing problem scores by age. Details concerning model selection and comparisons are reported in Supplementary Material Section 3. The final model had a significant fit to the data, Wald χ 2 (2) = 29.21, p < .001. The quadratic trend indicated a steeper increase in externalizing problem scores that became shallower between 7 and 9 years and reached a peak between 9 and 12 years, to then decrease, see Figure 2.

In a further model run based on 250 imputed datasets, we also included covariates: the final parameter estimates are reported in Table 3b. Previous model tests indicated the rate of change of externalizing problem scores was not affected by key covariates (sex, age at time of placement, family SES), see Supplementary Material Section 3. Overall, none of the covariates on their own indicated a significant association with the average externalizing problem scores, as indicated by model parameters in Table 3b. The model with covariates displayed a significant fit to the data, F(11, 498961.0) = 3.28, p < .001.

Table 3. (b) Parameters of the adjusted multilevel model of externalizing problems

Note. 95% CI: 95% Confidence Intervals; LB = Lower Bound; UB = Upper Bound. + p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01 ; *** p < .001.

Overall, the results indicated that participants’ pattern of change in externalizing problems followed a curvilinear trajectory: externalizing problems increased from age 3 years, but this increase decelerated progressively to reach a peak in late childhood. Similarly to the internalizing scores, the results indicated a considerable amount of variation between participants’ externalizing trajectories, and furthermore, there was a large within-child variability in externalizing problem scores from one age to another (see Table 3b). None of the covariates considered displayed a unique association with the externalizing scores while we controlled for other covariates.

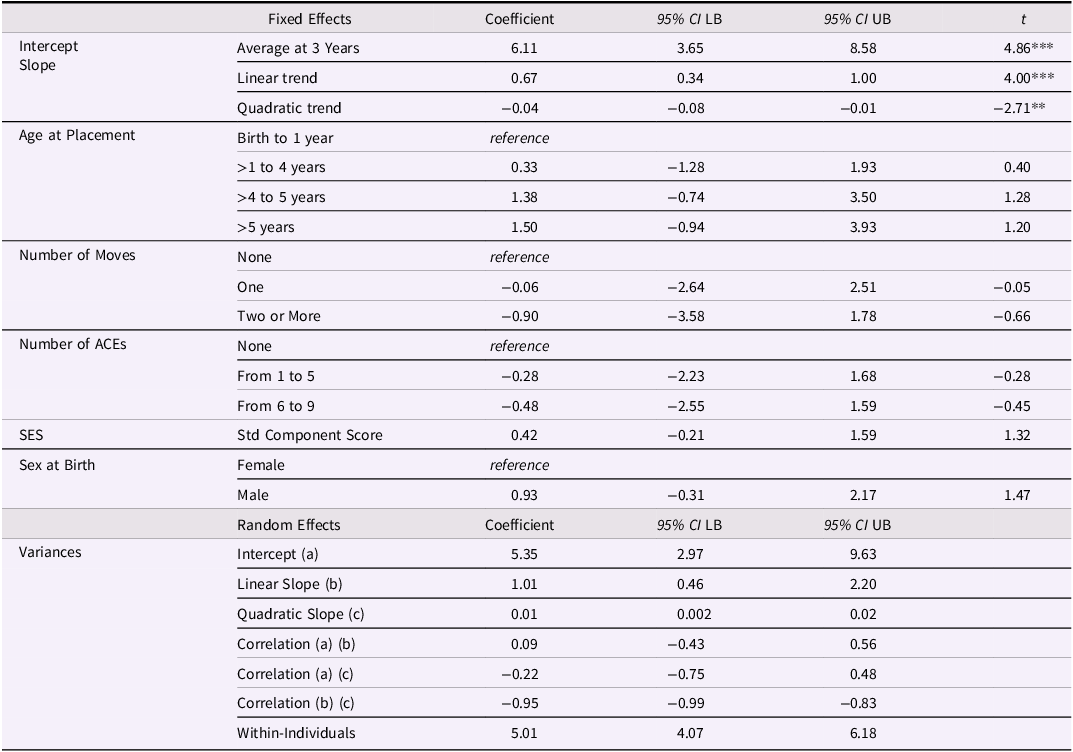

Internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems at the transition to schooling

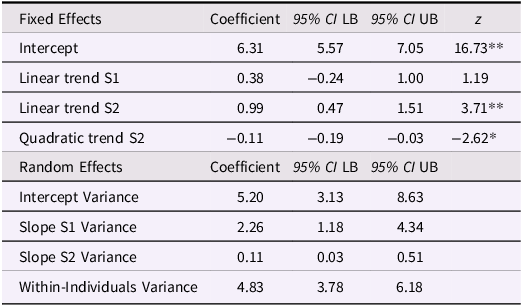

We ran spline models on the n = 62 children that were observed before and after entering school. Details about model selection are reported in Supplementary Materials Section 5. The spline model for internalizing symptoms indicated a non-significant linear rate of change in the period before children school entry, while the period following school entry was characterized by a quadratic rate of change: we report the estimated parameters of the final spline model in Table 4a. In Figure 3 we report the estimated predicted scores based on the spline model parameters: the model predicted that internalizing symptoms remained relatively stable before school entry but increased steadily after school entry. Internalizing symptom scores continued to increase, but a shallower decrease was predicted after age 8 years. Inclusion of covariates in the model confirmed the trends indicated, and, similarly to the results from the multilevel growth curve analyses reported in the previous section, indicated elevated internalizing symptom scores of children who were placed for adoption around the time they were bound to start school (age >3 to 5 years), see Supplementary Materials Section 5.

Figure 3. Predicted Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire scores by age according to spline models. Note. N = 62 children who provided data before and after school entry. Spline models divided the observation period into intervals, before school entry and after school entry. The red lines represent predicted score according to spline models for internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems respectively. The markers represent the observed outcome scores for individual children. The blue circles indicate scores reported before school entry, while red square markers are used to indicate scores obtained after school entry. Markers are transparent: greater density of colors indicate more observations obtaining the same score at the same age.

Table 4. (a) Parameters of the final spline model of internalizing symptoms

Spline models run on externalizing problems indicated a non-significant linear increase in these scores before children school entry, while externalizing problems were predicted to follow a quadratic trend after children school entry: the model parameters are reported in Table 4b and the predicted scores based on the model are represented in Figure 3. Externalizing problems were predicted to increase more steeply after children school entry. Compared to internalizing symptoms, however, they reached a peak earlier (approximately by 7 years of age) and, while internalizing symptoms were still expected to increase by 10 years of age (although at a slower rate), externalizing problems were predicted to start decreasing by this age. Inclusion of covariates did not indicate these showed significant associations with externalizing problem trajectories, see Supplementary Material Section 5.

Table 4. (b) Parameters of the final spline model of externalizing problems

Note. S1: Spline 1 — Before school entry; S2: Spline 2 — After school entry; 95% CI: 95% Confidence Intervals; LB: Lower Bound; UB: Upper Bound. * p < .01; ** p < .001.

Overall, the results of the spline models run on a sub-sample of participants observed before and after school entry suggested large variations in the patterns of change of mental health problems across different stages of childhood, with patterns diverging in correspondence of the transition into primary school. Internalizing symptoms increased steeply after school entry, while after age 8 years they continued to increase at a lower rate. Externalizing problems also increased steeply after school entry, but this increase decelerated after age 7 to then decrease following age 10 years. The results indicate, however, substantial between-child variation in the fitted trajectories, as well as considerable within-child variation from one assessment to another.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study represents the first longitudinal study that has charted the mental health trajectories of UK domestically adopted children from early childhood to early adolescence. Across this period, we identified a linear increase in children’s internalizing symptoms and a quadradic pattern for externalizing problems, where problems increased from early to middle childhood and appeared to decelerate and decline from late childhood to adolescence. Age at adoption was associated with children’s trajectories of internalizing symptoms. Children who were older at the time of adoption had more internalizing symptoms, but this association weakened when children were adopted after age five. Spline models indicated that entry to school marks a turning point of significant increases in children’s internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems in their first years of school. Our findings have important implications for guiding interventions and support for adoptees across childhood and into adolescence.

Trajectories and predictors of children’s internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems

We found that children’s trajectories appeared to mirror what tends to be a minority of children in the general population who exhibit increasing internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems from early childhood to adolescence. In our sample, children’s internalizing symptoms followed a linear increasing trajectory from 3 to 15 years. Population studies typically identify a small proportion of children who follow trajectories characterized by increasing levels of internalizing symptoms from early childhood to adolescence (i.e., 11% low and increasing, 3% high and increasing internalizing symptoms; (Papachristou & Flouri, Reference Papachristou and Flouri2020); see also (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Votruba-Drzal and Silk2015; Fanti & Henrich, Reference Fanti and Henrich2010; Parkes et al., Reference Parkes, Sweeting and Wight2016). For externalizing problems, adopted children in this sample tended to follow a trajectory of high and increasing scores, following a similar pattern to what is observed in a small proportion of children in population studies (i.e., 5% high and increasing externalizing problems, (Papachristou & Flouri, Reference Papachristou and Flouri2020); see also (Patalay et al., Reference Patalay, Fink, Fonagy and Deighton2016). Our findings suggest, however, that this increase in externalizing problems was followed by a deceleration and decline from late childhood to early adolescence. Nonetheless, the patterns of increasing internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems across childhood for adoptees is concerning, given increasing trajectory patterns are associated with adverse outcomes, such as negative changes in academic attainment (Patalay et al., Reference Patalay, Fink, Fonagy and Deighton2016) and self-harm and drug use in adolescence (Papachristou & Flouri, Reference Papachristou and Flouri2020).

On the basis of prior literature (Nadeem et al., Reference Nadeem, Waterman, Foster, Paczkowski, Belin and Miranda2017; Paine et al., Reference Paine, Perra, Anthony and Shelton2021; Vandivere & McKlindon, Reference Vandivere and McKlindon2010) we expected that number of moves before adoption, ACEs, and age at adoption would be associated with increasing and accelerated mental health problems. Our findings partially supported these expectations. Children who were older at the time of adoption experienced more internalizing symptoms, yet the association weakened when children were adopted after the age of 5 years. Although age at adoption does not fully capture pre-adoptive history, it can represent a proxy for early adversity (Tan & Marfo, Reference Tan and Marfo2016). Children adopted from public care later in childhood are more likely to have experienced prolonged adversity (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Paine and Shelton2019) and instability (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Litrownik and Landsverk2000) associated with negative cascades into different domains of development (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2013). Although these findings provide a useful indicator for practitioners to monitor children at greater risk of difficulties, more research is needed to disentangle specific risk and protective factors associated with children’s trajectories of mental health problems (Lacey & Minnis, Reference Lacey and Minnis2020). Furthermore, it is noteworthy that we detected great intra-individual variability in internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems that we were not able to explain with our age and time-invariant covariates. A question of interest could be to investigate how adoptees’ intra-individual variability compares to that of the general population in terms of (in)stability of mental health problems. Quite possibly, the unexplained variability and intra-individual instability in adoptees may be explained by contextual, age-specific factors that were not included in these analyses, such as onset of puberty.

Commencing formal schooling represents a major life transition and period of rapid change for all children (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, Reference Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta2000). Taking a life course perspective (Elder et al., Reference Elder, Johnson and Crosnoe2003; Elder, Reference Elder1998), we hypothesized that the demands of this transition might be particularly challenging for children adopted in a similar timeframe. Our subsequent analyses, therefore, pinpointed the short window of time as adoptees made the transition to school. We used Spline models to investigate variations in the patterns of change before and after transition to school. An advantage of using these models resides in the ability to allow for piecemeal patterns of growth at different stages of development, which, in turn, makes them suitable to model significant variations in correspondence of key events or turning points (Howe et al., Reference Howe, Tilling, Matijasevich, Petherick, Santos, Fairley, Wright, Santos, Barros, Martin and Kramer2013). One of the challenges in using Spline models lies in choosing sensible numbers and timings of knot-points that define intervals within a study period: in our study we selected a single knot-point that represented the key transition to school and, furthermore, the actual age when each individual child started school defined this knot-point. Thus, the partition of the study period into two intervals with piecemeal growth patterns was based on an objective criterion that represented a key transition in children’s lives.

The results of Spline models indicated discontinuities in the rate of change children’s internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems following transition to school. Both children’s internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems showed a significant linear increase after children started school. Children’s internalizing symptoms continued to rise across the school years, but externalizing problems plateaued after the first three years of school. Later age of adoption was associated with elevated children’s internalizing symptoms. Being adopted around school age ( >3 to 5 years) was associated with increased internalizing symptoms after school entry compared to children adopted shortly after birth or in early childhood.

Practical implications

The first years of school are vital for future success (Dockett et al., Reference Dockett, Griebel and Perry2017). Our findings highlight the need for special consideration of children who are experiencing multiple life transitions. Our findings underscore the importance of avoiding unnecessary delays to permanency planning, while making sure that transitions move at a pace that is comfortable for the child and accounts for other life events (Neil et al., Reference Neil, Morciano, Young and Hartley2020). Emphasis should also be placed on building collaborative and cohesive interpersonal systems between those who support the child through these normative and less normative transitions (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Dearing and Zachrisson2018). Part of this approach should involve shared professional understanding of children’s adoption status and pre-placement history, where appropriate, to facilitate and anticipate support needs (Goldberg & Grotevant, Reference Goldberg and Grotevant2023).

The escalating trajectories of adoptees’ internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems through childhood underscores the importance of early intervention when signs of mental health problems emerge. Some children may experience elevated, yet subthreshold problems, that mean they may not qualify for specialist support from mental health services (DeJong et al., Reference DeJong, Hodges and Malik2016). However, taken together with other research (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Wolke, Shanahan and Costello2015) our findings suggest these early difficulties place adoptees at risk for escalating problems and disorder later in life. It is vital that alongside the present findings, practitioners recognize the heterogeneity of adoptees’ early experiences and the consequences these have for their neurodevelopmental profiles at an individual level (DeJong et al., Reference DeJong, Hodges and Malik2016; Woolgar & Simmonds, Reference Woolgar and Simmonds2019). Our previous work indicates that systematic assessment of adoptees’ areas of need is a promising way to identify socioemotional and cognitive transdiagnostic risk factors that may underpin mental health problems (Paine et al., Reference Paine, Burley, Anthony, Van Goozen and Shelton2021, Reference Paine, van Goozen, Burley, Anthony and Shelton2023) that may be targeted with early intervention.

Limitations

We acknowledge some study limitations. First, the relatively small sample size precluded disentangling multiple trajectories that can be achieved via larger population studies (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Votruba-Drzal and Silk2015; Fanti & Henrich, Reference Fanti and Henrich2010; Papachristou & Flouri, Reference Papachristou and Flouri2020; Parkes et al., Reference Parkes, Sweeting and Wight2016; Patalay et al., Reference Patalay, Fink, Fonagy and Deighton2016). Second, the spline models were based on a smaller subsample of children who had questionnaires returned by parents before and after school entry; children in these analyses entered the study at a younger age, which also meant that many were in placement at an earlier age and were exposed to fewer adverse events relative to the rest of the sample. Third, our findings relied on single informant reports. Although parent reports are a critical source of information, future larger scale studies should avail of multiple reports of more domains of children’s school readiness and social and cognitive development (Pears et al., Reference Pears, Fisher, Kim, Bruce, Healey and Yoerger2013). This information could also be complemented by children’s self-report about their school experiences.

Finally, it is also important to note that relatively few children had reached secondary school age by the time of our last follow up. This therefore precluded us from investigating the transition to secondary school as a further turning point for mental health problems. As such, the apparent deceleration and decline of externalizing problems later in childhood to adolescence should be taken with caution. Transition to secondary school is a period of heightened worry for young people, often concerning new academic and social pressures, a new physical environment (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Angel, Brown, Van Godwin, Hallingberg and Rice2021; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Ng-Knight, Riglin, Powell, Moore, McManus, Shelton and Frederickson2021) and coinciding with ongoing pubertal development. Evidence suggests that children who have high levels of difficulties at the end of primary school continue to experience difficulties across the transition to secondary (Donaldson et al., Reference Donaldson, Hawkins, Rice and Moore2024). For adoptees, these challenges occur alongside a period where they develop a deeper social and cognitive understanding of adoption and adoptive identity (Brodzinsky & Palacios, Reference Brodzinsky and Palacios2023). Despite these limitations, the results are based on advanced models that enabled a thorough investigation of complex patterns of change, while accounting for potential limitations including the timings of data collection and missingness.

Conclusion

Adoption provides one of the best alternatives for children to have a secure family for life (Brodzinsky & Palacios, Reference Brodzinsky and Palacios2023). Despite the quality of parenting and home life offered by adoptive families (Anthony et al., Reference Anthony, Paine and Shelton2019; Paine et al., Reference Paine, Perra, Anthony and Shelton2021), our analyses demonstrate that through early childhood to early adolescence, children adopted from public care are at greater risk for experiencing increasing internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems. Entry into school may represent a particular challenge and time of vulnerability for young adoptees, particularly if they experience this alongside or temporally close to their adoption. These findings emphasize the vital importance of continued support for adoptive families. Indeed, efforts to support adopted children through the school transition, particularly those also contending with other major life events, may enable them to flourish through the school years.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579425100175.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, ALP. The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research and privacy/ethical restrictions, the supporting data is not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks go to the staff from the local authority adoption teams in Wales, who kindly assisted with contacting families, and to our research advisory group for their guidance. We thank the families who took part in this study and Sarah Meakings, Charlotte Robinson, and Janet Whitley for research assistance.

Funding statement

The preparation of this manuscript was funded by the Welsh Government. The Wales Adoption Study was initially funded by Health and Care Research Wales, a Welsh Government body that develops, in consultation with partners, strategy and policy for research in the NHS and social care in Wales (2014–2016, Grant reference: SC-12-04; Principal Investigator: Katherine Shelton, co-investigators: Julie Doughty; Sally Holland; Heather Ottaway). Amy L. Paine was funded by the Waterloo Foundation (Grant reference: 738/3512) and the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant ref: ES/T00049X/1).

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.