1 Introduction

It has long been acknowledged, by speech-act theorists and theoretical linguists alike, that some modifiers are truth-conditional while others are not (e.g. Urmson Reference Urmson and Catón1963; Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972; Bellert Reference Bellert1977; Strawson Reference Strawson, Berlin, Forguson, Pears, Pitcher, Searle, Strawson and Warnock1973; Allerton & Cruttenden Reference Allerton and Cruttenden1974: 7–8; Bach & Harnish Reference Bach and Harnish1979; Chafe Reference Chafe, Chafe and Nichols1986; Palmer Reference Palmer1986; Fraser Reference Fraser1996; Ifantidou Reference Ifantidou1993; Mittwoch et al. Reference Mittwoch, Huddleston, Collins, Huddleston and Pullum2002). Thus, there seems to be general agreement that illocutionary adverbs like frankly and attitudinal adverbs like unfortunately do not contribute to the truth-conditionality of the proposition (are not part of the proposition), but instead serve as comments on the proposition.Footnote 2 In Functional Discourse Grammar (FDG), where modifiers, on the basis of their semantic, syntactic and discourse-pragmatic properties, are assigned to a particular level and layer of representation, the notion of non-truth-conditionality plays an important role, as it helps to determine which modifiers belong to the Interpersonal Level and which to the Representational Level of analysis: while interpersonal (higher-layer) modifiers are by definition non-propositional, and as such non-truth-conditional, representational (lower-layer) modifiers are part of the proposition (restricting the denotation of a particular semantic layer), and are as such taken to be truth-conditional (e.g. Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 121, 128–9).

As it turns out, however, there are at least two groups of representational modifiers which are non-truth-conditional. First, there is the group of what are traditionally referred to as subject-oriented adverbs, like cleverly, wisely and stupidly in example (1),Footnote 3 which are generally assumed to belong to a relatively low level of analysis (e.g. Cinque Reference Cinque1999; Ernst Reference Ernst2002), and which in FDG have been analysed at the Representational Level (Dik et al. Reference Dik, Hengeveld and Nuyts1990; Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008); nevertheless, they do not affect the truth-conditional value of the proposition.

(1)

(a) Flo had flared when he'd raised that possibility and he'd wisely not brought it up again. (COCA, fiction)

(b) The service manual you cleverly purchased years ago will unlock all the secrets, (COCA, magazine)

(c) I selflessly took on the job, (COCA, magazine)

The same is true for the non-restrictive attribute adjectives in example (2). These, too, do not contribute to the truth conditions of the clause that they appear in, but merely add additional information about the referent in question (e.g. Bolinger Reference Bolinger1967, Reference Bolinger1989: 198; Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 1239; Ferris Reference Ferris1993; Biber et al. Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 242; Huddleston et al. Reference Huddleston, Payne, Peterson, Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1353; Larson & Maruśić Reference Larson and Marušič2004: 275; Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Haegeman and Stavrou2007: 334–5; Cinque Reference Cinque2010: 6–7; Matthews Reference Matthews2014: 168):

(2)

(a) There were seven of us, my three kids, wife, my father-in-law, my old mother and me (COCA, spoken)

(b) Our friendly staff is here to make sure that you have an outstanding experience. (www.brecksvilledermatology.com/meet-us/our-friendly-staff/)

(c) The prolific Toni Morrison returned this year with her first novel set in the current time. (COCA, magazine)

The present article will consider the consequences of this apparent anomaly both for the analysis of the modifiers in question, and, more generally, for the role of truth-conditionality in FDG. On the basis of data from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies Reference Davies2008), the News on the Web Corpus (NOW; Davies Reference Davies2015), and some additional examples from the internet, it will be argued that the fact that adverbs like cleverly and non-restrictive adjectives are non-truth-conditional is not incompatible with their being analysed at the Representational Level, as long as they are not analysed as restrictors, but instead as part of a separate proposition that can scope over various layers of analysis.

In what follows I will first provide a brief introduction to the relevant aspects of the theory of FDG, focusing on the different levels and layers of representation and the way they are used in the analysis of adverbs (or modifiers in general) (section 2). Next I will discuss the group of subject-oriented adverbs, looking at their truth-conditionality status and their syntactic features. I will propose an analysis of these adverbs that can reconcile their non-truth-conditionality with their representational status, and which can also deal with the seemingly conflicting syntactic evidence (section 3). I will then turn to the non-restrictive prenominal adjectives. I will discuss their non-restrictive (non-truth-conditional) status and their specific formal features, before arguing that the analysis proposed for the subject-oriented adverbs can also be applied here (section 4). Section 5 will conclude.

Before we start, I would like to comment briefly on the terminology used. As mentioned above, adverbs like cleverly and wisely are typically called subject- (or agent-)oriented adverbs in the literature. However, the participant in question does not necessarily function as the subject, as in those cases where the adverb applies to the (implied) agent in a passive sentence (as in example (3); see Mittwoch et al. Reference Mittwoch, Huddleston, Collins, Huddleston and Pullum2002: 678–9; Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 576). In other cases, there may not even be an agent (example (4); see Potts Reference Potts2005: 14).

(3) The speedometer was wisely placed above the cockpit display, in your sight line, (COCA, newspaper)

(4) Cleverly, there is a mesh bag which pulls out to keep wet or dirty items separate … (COCA, magazine)

For these reasons (and for additional reasons which will become clear later), I will here use the term predicative-evaluative (or evaluative for short) to refer to this group of adverbs.

2 Introduction to FDG

2.1 Overall characterization

Functional Discourse Grammar is a functional theory in that it takes a ‘function-to-form’ approach, based on the assumption that (both synchronically and diachronically) the shape of a linguistic utterance (or, more generally, of a language as a whole) is largely (if not exclusively) determined by the communicative function it fulfils (e.g. Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 29, with reference to Dik Reference Dik1986). At the same time, however, FDG is ‘form-oriented’, in that it captures only those pragmatic and semantic, as well as contextual, phenomena in underlying representation that are systematically reflected in the morphosyntactic and phonological form of an utterance (e.g. Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 39, 40).

These principles are reflected in the distinctive features of the model. Thus, the model is organized in a top-down manner, starting with the Speaker's communicative intention and ending with the articulation of a linguistic utterance. In this process, pragmatics takes precedence over semantics, while pragmatics and semantics together take precedence over morphosyntactic and phonological form (see Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 13). The privileged role of pragmatics is further reflected in the fact that FDG takes the Discourse Act rather than the sentence or the clause as its basic unit of analysis. Consequently, FDG can accommodate not only regular clauses, but also units larger than the clause, such as complex sentences, and units smaller than the clause, such as interjections or phrases.

2.2 Four levels of analysis

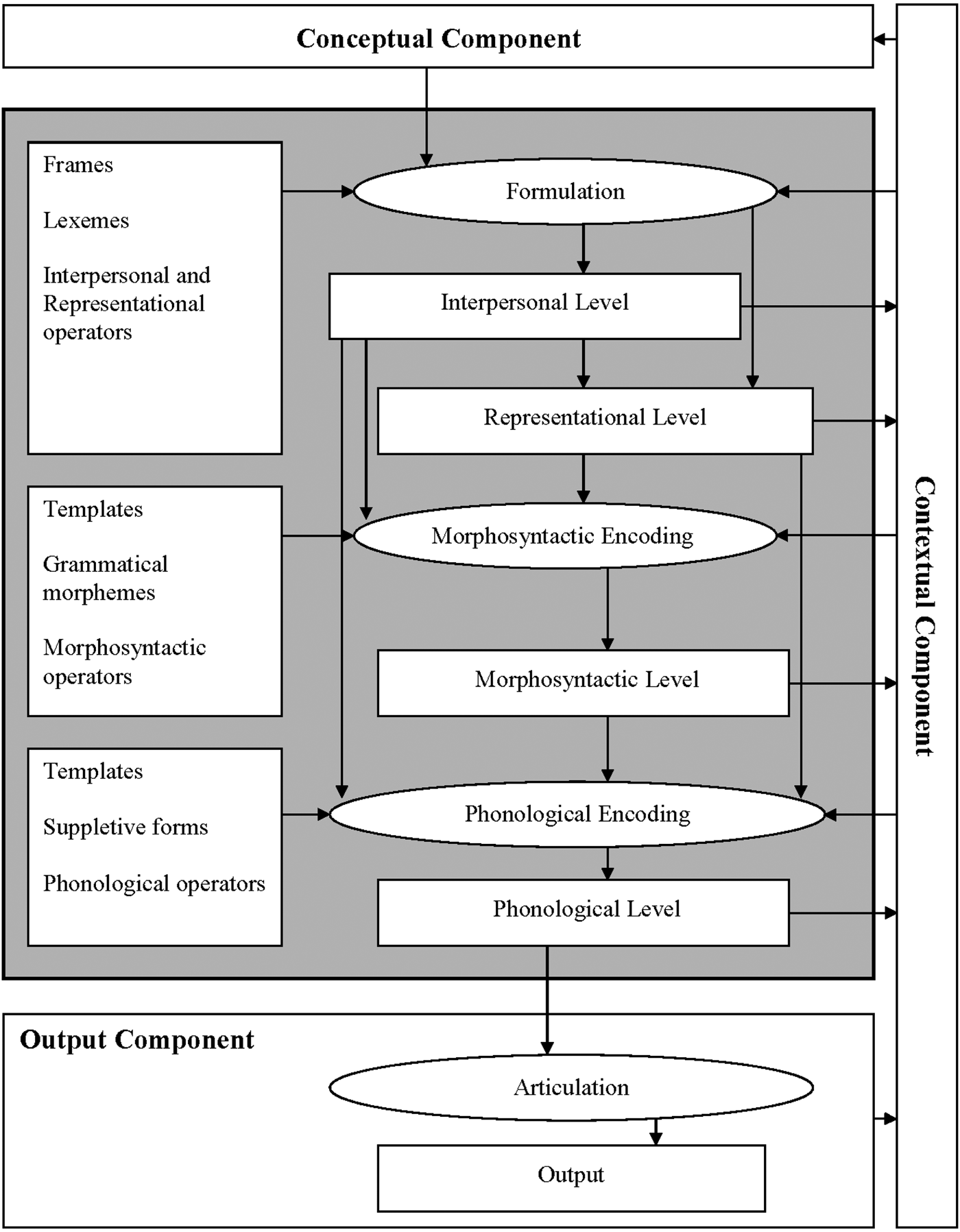

In order to represent all the pragmatic, semantic, morphosyntactic and phonological features of a linguistic expression, FDG analyses Discourse Acts in terms of four independent levels. Together, these four levels, and the primitives feeding into these levels, form the grammatical component of the model (the FDG proper). This grammatical component does not function in isolation, but interacts with three other components: a conceptual component, which consists of the speaker's communicative intentions, and which forms the driving force behind the grammatical component (see e.g. Connolly Reference Connolly2017); a contextual component, containing non-linguistic information about the immediate discourse context that affects the form of a linguistic utterance (see also Connolly Reference Connolly2007, Reference Connolly, Alturo, Keizer and Payrato2014; Cornish Reference Cornish, Keizer and Wanders2009; Alturo et al. Reference Alturo, Keizer, Payrato, Alturo, Keizer and Payrato2014; Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2014); and an output component, consisting of the spoken, signed or written realization of a linguistic utterance. An overview of the model is given in figure 1.

Figure 1. General layout of FDG (based on Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 13)

2.2.1 The Interpersonal and Representational Levels

The four levels of representation are the outcome of two types of operations. Proceeding in a top-down manner, the first operation is that of Formulation, which deals with all the meaningful elements of a linguistic utterance. The outcome of this operation takes the form of representations at the higher two levels of analysis, the Interpersonal and Representational Levels, which together capture all the pragmatic and semantic aspects of a linguistic expression. The second operation, that of Encoding, subsequently takes care of an expression's formal properties, and leads to representations at the Morphosyntactic and Phonological Levels. Each of these four levels is hierarchically organized into a number of different layers.

The highest level of representation, the Interpersonal Level (IL), deals with ‘all the formal aspects of a linguistic unit that reflect its role in the interaction between the Speaker and the Addressee’ (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 46). The most inclusive layer at this level is the Move (M), which forms ‘the largest unit of interaction relevant to grammatical analysis’ (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 50). Each Move consists of one or more Discourse Acts (A), defined as ‘the smallest identifiable units of communicative behaviour’ (Kroon Reference Kroon1995: 85; Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 60), but which, unlike Moves, ‘do not necessarily further the communication in terms of approaching a conversational goal’ (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 52). These Discourse Acts, in turn, consist of an Illocution (F), the Speech Participants (P1 and P2) and a Communicated Content (C), which ‘contains the totality of what the Speaker wishes to evoke in his/her communication with the Addressee’ (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 87). The Communicated Content, finally, consists of one or more Subacts of Reference (R), evoking entities, and Subacts of Ascription (T), evoking the properties the Speaker wishes to assign to these entities.

Each of these layers is provided with slots for operators and modifiers, which provide additional grammatical and lexical information, respectively, about the layer in question. Modifiers at the Interpersonal Level often take the form of interpersonal adverbs,Footnote 4 which are necessarily speaker-bound and non-truth-conditional (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 130, 144). Different groups of adverbs belong to (scope over) different interpersonal units, depending on their function: adverbs like frankly, expressing the manner in which the speaker performs the illocutionary act, are analysed as modifiers of the Illocution; adverbs like (un)fortunately and (un)surprisingly, expressing the speaker's attitude with regard to what is communicated, as modifiers of the layer of Communicated Content; and stylistic adverbs like briefly, indicating stylistic features of an expression, as modifiers of the Discourse Act or Move (e.g. Hengeveld Reference Hengeveld1989, Reference Hengeveld and Wotjak1997; Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008).

By way of illustration consider the following example:

(5)

(a) Dave surprisingly gave me a watch.

(b) (MI: (AI: [(FI: DECL (FI)) (PI)S (PJ)A (CI: [(TI) (RI) (RJ) (RK)] (CI): surprisingly (CI))] (AI)) (MI))

In (5b) we find a Move consisting of a single Discourse Act, which in turn consists of a declarative Illocution (FI), the two Speech Participants, (PI)S and (PJ)A, and a Communicated Content (CI). The Communicated Content consists of a Subact of Ascription (TI), evoking the property ‘give’, and three Subacts of Reference, (RI), (RJ) and (RK), evoking the entities described as he, me and a watch. The attitudinal adverb surprisingly is analysed as a modifier of the Communicated Content.

The Representational Level (RL) deals with the semantic aspects of a linguistic expression, i.e. with those aspects that reflect the way in which language relates to the (real or imagined) world it describes. The units at this level represent the different linguistically relevant types of entities in the extralinguistic world (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 131; compare Lyons's (Reference Lyons1977: 442–7) ‘orders of entities’). The highest layer at this level is that of the Propositional Content (p), which represents a mental construct that can be evaluated in terms of its truth. The Propositional Content consists of one or more Episodes (ep), i.e. sets of States-of-Affairs (SoA) that are coherent in terms of time, space and participants. Each SoA (e) is, in turn, characterized by a Configurational Property (fc), typically consisting of a verb (analysed as a Lexical Property, fl) and its arguments (which often take the form of Individuals (x), i.e. concrete entities).

Once again each layer is provided with a slot for operators and modifiers, the former expressing grammatical information (tense, aspect, modality, number), the latter providing additional lexical information concerning the layer in question. Representational modifiers often take the form of lower-layer adverbs, which are typically truth-conditional. The clearest examples are adverbs that are part of the predication, e.g. manner adverbs (modifying a verbal Property), frequency adverbs (modifying the SoA) and time adverbs (modifying the Episode). Modal and evidential adverbs like probably or evidently (modifying the Propositional Content), however, are also included in the set of representational adverbs.Footnote 5 Note that although these adverbs can be speaker-bound (expressing the speaker's degree of commitment to the truth of the Propositional Content), this need not be the case (e.g. probably in John says that he probably won't come tonight, where it is used to express someone else's (in this case John's) degree of commitment to the truth of the Propositional Content).

A Representational Level analysis of sentence in (6a) is provided in (6b):

(6)

(a) Dave will probably give me an expensive watch tomorrow.

(b) (pi: (fut epi: (ei: (fci: [(fli: give (fli)) (1xi)A (1xj)R (1xk: (flj: watch (flj)) (xk): (flk: expensive (flk)) (xk))U] (fci)) (ei)) (epi)) (pi): probable (pi))

The highest layer of analysis here is the Propositional Content pi. This Propositional Content contains a single Episode epi, which in turn consists of a single SoA ei. This SoA is headed by a Configurational Property fci, consisting of the verb give (a Lexical Property, fli) and its three arguments (the Individuals xi, xj and xk). The first two arguments, xi and xj, represent the noun phrases Dave and me, which consist of a variable only, as they lack descriptive content. The third argument, xk, is restricted by two Properties: first by the nominal Property ‘watch’ (the head, or first restrictor), and subsequently by the adjectival Property ‘expensive’ (a modifier, or second restrictor).Footnote 6 The representation contains two more modifiers, probable at the layer of the Propositional Contents and tomorrow at the layer of the Episode, as well as the tense operator ‘future’ at the layer of the Episode.

Finally, the fact that modifiers are assigned to a particular layer of analysis allows for predictions about which adverbs can occur in which verbal complements. On the assumption that different types of verbs take different layers as their clausal complement (i.e. have different selectional or subcategorizational properties), we may expect there to be constraints on the occurrence of adverbs in the clausal complement of a verb, in the sense that a complement cannot contain an adverb that functions as a modifier at a higher layer than that of the complement itself (Hengeveld Reference Hengeveld and Nuyts1990: 16–17; Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 363–5; cf. Ramat & Ricca Reference Ramat, Ricca and van der Auwera1998: 222; Bach Reference Bach1999: 358; Potts Reference Potts2005: 145–6). For instance, since verbs of knowing take a Propositional Content as their complement, these complements can contain propositional modifiers like probably, but not higher-layer adverbs like reportedly (which modifies the Communicated Content):

(7) Somebody back there was smart enough to know that Nairam probably (*reportedly) had the line tapped. (COCA, fiction)

2.2.2 The Morphosyntactic and Phonological Levels

The output of the operation of Formulation forms the input to the operation of Encoding. The first level of Encoding, the Morphosyntactic Level, accounts for all the linear properties of a linguistic expression, using the same placement rules for clauses, phrases and complex words. These placement rules are functionally inspired, applying in a top-down, outside-in manner, with operators, modifiers and functions belonging to the highest layer at the Interpersonal Level (the Move) being placed first, and those from the innermost layer at the Representational Level (the Property) being placed last. In the case of multiple modifiers this means that higher adverbs are more likely to be placed in more peripheral (preverbal) positions, and lower adverbs in more central or postverbal positions. By way of illustration, consider the following example:

(8) She will unfortunately probably leave for Brazil again tomorrow.

In this example, the attitudinal adverb unfortunately, as the only interpersonal modifier, is the first element to be placed. The adverb probably, as the highest representational modifier, is the next element to be placed, going to the position immediately following unfortunately. Next, the Episode modifier tomorrow is placed in clause-final position, and the frequency adverb again in pre-final position.

Finally, the Phonological Level converts the input from the three higher levels into phonological form. Once again the layers at this level are hierarchically organized into Utterances (u), which form the highest layer, Intonational Phrases (ip), Phonological Phrases (pp), Phonological Words (pw), Feet (f) and Syllables (s). The layer that is most relevant for the current discussion is that of the Intonational Phrase, which is characterized internally by the presence of a complete intonational contour and externally by the presence of intonational boundaries, and which, in the default case, corresponds to a Discourse Act at the Interpersonal Level.

3 Predicative–evaluative adverbs

3.1 Truth-conditionality

Predicative-evaluative adverbs like cleverly are used to express an evaluation of an action, as well as of the agent involved in this action (cf. Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1972: 465; Haumann Reference Haumann2007: 201). Thus, in (1c), the speaker assigns the Property ‘selfless’ to the entire SoA (‘the speaker taking on the job was a selfless thing to do’), as well as to the Actor for performing the SoA (‘it was selfless of the speaker to take on the job’):

(1) (c) I selflessly took on the job (COCA, magazine)

It is this combination of properties that distinguishes these adverbs from, on the one hand, attitudinal adverbs like unfortunately, which express a speaker's attitude towards the message conveyed, but do not evaluate the agent involved, and, on the other, volitional adverbs like reluctantly, which are agent-oriented, but do not offer a subjective evaluation of the event as a whole (Mittwoch et al. Reference Mittwoch, Huddleston, Collins, Huddleston and Pullum2002: 676).

In FDG, these evaluative adverbs have been analysed as representational modifiers at the layer of the SoA (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 209), an analysis compatible with those offered elsewhere (e.g. Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985; Cinque Reference Cinque1999; Ernst Reference Ernst2002; Mittwoch et al. Reference Mittwoch, Huddleston, Collins, Huddleston and Pullum2002). Such an analysis is, however, problematic, since in FDG, as well as in many other theoretical approaches, representational (lower-layer) modifiers (or adjuncts) function as restrictors (e.g. Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 14, 81; see also Dik Reference Dik and Hengeveld1997: 132–6): they restrict the denotation set of their head, i.e. of the semantic unit (SoA, Episode, Propositional Content, etc.) they scope over. This is not, however, what evaluating adverbs do: they do not restrict the set of SoAs denoted by their head, but provide additional information about this SoA (in the form of the speaker's evaluation). In other words, these adverbs are non-truth-conditional (see also Bellert Reference Bellert1977; Mittwoch et al. Reference Mittwoch, Huddleston, Collins, Huddleston and Pullum2002: 677), as confirmed by two common tests for truth-conditionality (see also Ifantidou Reference Ifantidou1993; Papafragou Reference Papafragou2006): the assent/dissent test and the scope (embedding) test.

I. The assent/dissent test

The assent/dissent test is based on the assumption that only propositional content can be denied directly by expressions like Yes or No, or I (don't) agree.Footnote 7 Any part of an expression that can be affirmed or denied in this way must therefore be propositional, and as such truth-conditional. In FDG, this test is used to support the distinction between interpersonal and representational adverbs (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 128–9). The former, being non-truth-conditional, cannot be denied or affirmed; the latter, being truth-conditional, can. As it turns out, evaluative adverbs behave in this respect like interpersonal adverbs, in that they cannot be confirmed or denied:

(9) Peter cleverly avoided the question. [evaluative]

(a) I agree. (He avoided the question.); No. (He didn't avoid the question.)

(b) *I agree. (It was a clever thing to do.); *No. (It was not a clever thing to do.)

(10) Peter avoided the question cleverly. [manner]

(a) I agree. (He avoided the question.); No. (He didn't avoid the question.)

(b) I agree. (He did so cleverly.); No. (He didn't do it cleverly.)

In (9) the Propositional Content as a whole can be affirmed or denied (see (9a)), but the information conveyed by the evaluative adverb cleverly cannot (see (9b)). In (10), where cleverly is used as a representational (manner) adverb, it is possible to deny both the Propositional Content as a whole (see (10a)) and the contribution made by the adverb (see (10b)). This confirms that, unlike manner adverbs, evaluative adverbs are, indeed, non-truth-conditional.

II. The scope test

The scope (or ‘embedding’) test (e.g. Ifantidou Reference Ifantidou1993; Asher Reference Asher2000; Papafragou Reference Papafragou2006; see also Cohen Reference Cohen and Bar-Hillel1971; Wilson Reference Wilson1975) consists in embedding the sentence containing the adverb into a conditional to see if the adverb falls within the scope of if; if it does, the adverb is truth-conditional; if not, it is non-truth-conditional. To apply the test to the evaluative adverb stupidly, the sentence in (11a) is embedded into a conditional, yielding example (11b):

(11)

(a) Mary has stupidly decided not to give the plenary.

(b) If Mary has stupidly decided not to give the plenary, we must ask someone else.

Since the truth-conditions of the main clause (i.e. the conditions under which we must ask someone else) are not affected by the presence of the adverb stupidly (whether or not it was a stupid thing for Mary to decide not to give the plenary is in this respect irrelevant), the evaluative adverb stupidly is not truth-conditional.

As a manner adverb, on the other hand, stupidly is truth-conditional: in example (12b), George will have failed the test only if (i) he has answered the question, and (ii) if he has done so stupidly.

(12)

(a) George has answered this question stupidly.

(b) If George has answered this question stupidly, he will have failed the test.

3.2 Syntactic features

The unexpected combination of non-truth-conditionality and representational function is reflected in the syntactic behaviour of evaluative adverbs. As several linguists have pointed out, adverbs differ with regard to the possibility of clefting and questioning, as well as with regard to whether they do or do not fall within the scope of (predication) pronouns, ellipsis or negation. This has often been used as a means to distinguish so-called parenthetical adverbs from sentence adverbs (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 504–5, 612–31; Espinal Reference Espinal1991: 729; Haegeman Reference Haegeman, Shaer, Cook, Frey and Maienborn2009 [1991]). These properties, however, are a direct result of the non-predicational nature of the adverbs involved (rather than from their syntactic or prosodic non-integration), as clefting and questioning are restricted to elements that are part of the predication. The fact that, unlike manner adverbs, evaluative adverbs do not allow for questioning and clefting (compare (12aB) and (12a′) to (1c)Footnote 8 and (1c′)) thus indicates that they are not part of the predication (see also Keizer Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018).

(12) (a) George has answered this question stupidly.

A: How did George answer the question?

B: Stupidly.

(12) (a′) It was stupidly that George answered the question

(1) (c) I selflessly took on the job (COCA, magazine)

A:???

B:*Selflessly.

(1) (c′) *It was selflessly that I took on the job.

This also explains why these adverbs fall outside the scope of predicate negation, ellipsis and pronominalization. For negation, this is illustrated in example (1a), repeated here for convenience, where the adverb wisely clearly has scope over the negator not; for pronominalization, this is shown in example (13), where the adverb wisely is outside the scope of the pronoun it.

(1) (a) Flo had flared when he'd raised that possibility and he'd wisely not brought it up again. (COCA, fiction)

(13) Girardi wisely turned Baltimore down. He said it was because of his family. (COCA, newspaper)

In both these respects, evaluative adverbs behave like interpersonal adverbs, since both groups of adverbs are not part of the predication. It would be premature, however, to deduce from this that evaluative adverbs are interpersonal, since in other respects, such as (constraints on) modification, clausal position and embedding, they behave as representational adverbs. When it comes to modification, for instance, these adverbs allow for a range of representational adverbs – too, so, almost – that cannot be used to modify interpersonal modifiers:Footnote 9

(14)

(a) he'd found the still and silent epicenter of all that fatal action he had so wisely avoided. (COCA, fiction)

(b) They too recklessly reduce the myriad complexities of the Christian world into a bogus behemoth, (www.hoover.org/research/can-iran-become-democracy)

(c) ‘They have almost recklessly continued to proceed on a path that is going nowhere,’ Dr Ferguson said. (NOW, JM)

So far, we have been able to establish that, in terms of syntactic behaviour, evaluative adverbs, in keeping with what has been proposed in the literature, are representational. The next question to be answered is to which representational layer they belong. Here it is useful to look at their relative clausal position and occurrence in the complements of verbs. First of all, the relative clausal position of evaluative adverbs confirms their representational status, as they follow interpersonal adverbs (example (15); cf. Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 311–14). Note, in addition, that they do not occur at the lowest representational level, as indicated by the fact that they precede manner adverbs (example (16)); this seems to support their analysis as SoA or propositional adverbs.

(15)

(a) And because of that, I think we embraced them even more, and quite frankly selfishly (*selfishly quite frankly) enjoyed the fact that we got to keep them to ourselves.

(http://embed.scribblelive.com/Embed/v7.aspx?Id=2687300&Page=1&overlay=false)

(b) they will be asked to determine whether the Boy Scouts should pay up to $25 million in punitive damages for allegedly recklessly (*recklessly allegedly) allowing Dykes -- who had admitted to a bishop and Scouting coordinator that he'd molested 17 Boy Scouts -- to continue to associate with the troop. (COCA, US)

(16) And as the kids wisely quickly vacated the pool, (https://books.google.at, James G. Davies, Shifts, p. 336)

When it comes to the relative ordering of epistemic and subject-oriented adverbs, however, the picture is less clear. On the basis of examples like those in (17), Cinque (Reference Cinque1999) and Ernst (Reference Ernst2002) conclude that epistemic modals scope over evaluative adverbs (taking a higher position in the structure of the clause; e.g. Ernst Reference Ernst2002: 19, 105):

(17)

(a) She probably has wisely returned the money.

(b) *She cleverly has probably returned the money.

Haumann (Reference Haumann2007: 360; see also 411), on the other hand, uses examples (18) and (19) to argue that evaluative (subject-oriented) adverbs have a higher base position than epistemic adverbs:

(18)

(a) *Probably, he clumsily had tried to open the box.

(b) *Possibly, she foolishly had pulled her stitches.

(19)

(a) Wisely they probably decided to go… (www)

(b) Foolishly she possibly would pull her stitches.

As shown in example (20), instances of a modal adverb preceding (scoping over) an evaluative adverb are not ungrammatical:

(20)

(a) Yamaha certainly has wisely installed a boost system in their genset. (www.forestriverforums.com/forums/f30/yamaha-ef3000ise-vs-honda-eu2000i-companion-2-vs-honda-eu3000is-21195.html)

(b) Probably he wisely concluded that there could be no defense for such a straying away from tho [sic] ‘narrow path.’ (https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=DAC18700505.2.24)

However, the reverse order, regarded as ungrammatical by Cinque and Ernst, also seems to be possible:

(21) Stupidly they probably think they have their thirst under control. (www.wattpad.com/362362161-empire-trei)

Finally, some examples can be found of these adverbs occurring adjacently; again both orders seem to be acceptable:

(22)

(a) They probably foolishly believed the American Defense Department Big Lie that radiation does not hurt you. (NOW, US)Footnote 10

(b) Last year in MUT I foolishly probably spent between $750-$1000. (https://answers.ea.com/t5/FIFA-15/Packs/td-p/4556769)

In other words, the evidence from clausal position clearly confirms that evaluative adverbs operate at the Representational Level; the exact layer of analysis, however, remains unclear, with examples (20) and (22a) suggesting that they occur at the layer of the SoA or Episode, while examples (21) and (22b) seem to indicate that they function at the layer of the Propositional Content (an analysis also proposed by Dik et al. Reference Dik, Hengeveld and Nuyts1990; Ramat & Ricca Reference Ramat, Ricca and van der Auwera1998: 192).

The idea that evaluative adverbs may in fact occur at a layer higher than the SoA is further supported by their scope in relation to other kinds of modifiers. Let us first consider example (23). Here the locative expression in the wagon modifies the SoA (the two sisters saying their goodbyes); since the SoA modifier clearly falls within the scope of wisely (it was wise of them to have performed the action in the wagon), we can conclude that wisely here functions at least at the layer of the SoA.

(23) Having wisely said their good-byes in the wagon, she and Sister Ida exchanged a chaste kiss, though tears were pouring down the nun's cheek. (COCA, fiction)

Turning to the two examples given in (24), however, we see that evaluative adverbs can also take an Episodical modifier in their scope. Thus, whereas in (24a) it is plausible to assume that the time modifier in 2006 falls outside the scope of wisely (which belongs to the layer of the SoA), the time adverbial in 1996 in (24b) clearly falls within the scope of wisely, which means it must be analysed as a modifier of the Episode:

(24)

(a) Washington wisely undertook a similar goodwill effort in 2006 by sending the Mercy into South and Southeast Asia. (COCA, academic)

→ It was wise of Washington to undertake a similar goodwill effort, which they did in 2006

(b) Former Enron president wisely left firm in 1996, uncomfortable with ‘asset light’ strategy. (COCA, magazine)

→ It was wise of the former Enron president to leave the firm in 1996 (i.e. before the fast expansion started (1997–2000) which led to the company's collapse and the ensuing scandal (2001))

Moreover, as we have seen, evaluative adverbs can also scope over epistemic adverbs (see examples (21) and (22b)), suggesting that they belong to the layer of the Propositional Content.

To complicate matters even further, however, evidence from the behaviour of these adverbs in embedded environments suggests that they must belong to a layer lower than that of the Propositional Content. Thus, as shown in (25), they readily occur in the SoA complement of the verb prevent – a clear indication that these adverbs do not operate at the layer of the Propositional Content (cf. Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 363–5):

(25)

(a) Sadly, when I saw the Chief he was powered down, to prevent passers by from stupidly sticking their fingers into the running fan blades of the GTX 1080. (NOW, US)

(b) But he asks his men to strap him to the ship's mast to prevent him from recklessly heeding the Sirens’ call. (https://hbr.org/2013/01/leaders-unplug-your-ears-and-l)

Interestingly, however, the following examples show that these adverbs can even appear in the complement of aspect verbs like continue and be able to, suggesting that they must belong to the layer of the Configurational Property:

(26)

(a) but when I see a sign that says ‘Bridge Out Ahead’, I don't need to convince myself by continuing to foolishly drive on… (NOW, AU)

(b) With the bundle, he is able to sensibly have an assortment of impeccable business shirts available at all times (NOW, US)

(c) they continue to recklessly lump all drug-related deaths together, (COCA, CA)

Clearly, these data are at odds both with the generally accepted view of these adverbs as modifying the SoA, as well as with the previous observations, based on clausal position and scope relations, that these adverbs can occur at the layer of the Propositional Content.

Note finally that the fact that these adverbs can be part of an embedded Propositional Content (irrespective of the precise layer of analysis) also means that they are not necessarily speaker-bound. Thus, in example (27), it is not the speaker who evaluates the embedded predication, but the subject of the main clause. This provides us with further evidence that these adverbs, despite their subjective, evaluative nature, are indeed representational.

(27) They believe their city wisely refused to build large levees, (COCA, academic)

The question that now arises is whether there is a way of analysing these adverbs that reconciles their truth-conditionality with their representational status, and which, at the same time, can account for the seemingly conflicting syntactic evidence concerning the exact layer of analysis. In the next section, it will be argued that such an analysis is indeed possible.

3.3 Evaluative adverbs as (parts of) separate Propositional Contents

As we have seen above, FDG analyses non-truth-conditional modifiers (e.g. illocutionary, attitudinal adverbs) at the Interpersonal Level, and truth-conditional modifiers (e.g. time, place and manner adverbs) at the Representational Level. All these modifiers are, however, represented in the same way, namely as restrictors of the variable at the relevant interpersonal or representational layer (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 14, 83; cf. Dik Reference Dik and Hengeveld1997: 132–6).

Nevertheless, it will be clear that restrictors play a different function at the two levels. At the Interpersonal Level, elements are analysed as restrictors (modifiers) when they provide additional information about an interpersonal layer (typically in the form of a speaker's comment on the unit in question) and are prosodically integrated. In a sentence like (28), for instance, the prosodically integrated modifier frankly is regarded as restrictive and is therefore represented as restricting the head of the Illocution (DECL) (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 82):

(28)

(a) I frankly fail to see the point of all this.

(b) (FI: DECL (FI): frankly (FI))

The theory also provides for the analysis of non-restrictive expressions at the Interpersonal Level (adverbs, relative clauses), but only when these are prosodically non-integrated, in which case they are analysed as separate Discourse Acts (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 49–50, 58, 81–2), as in example (29c) (see also Keizer Reference Keizer, Keizer and Olbertz2018):

(29)

(a) Frankly, I fail to see the whole point of this.

(b) Quickly, we don't have a lot of time left. (COCA, spoken)

(c) [(AI) (AJ)]

Traditional restriction, in the sense of restricting the potential set of referents, on the other hand, takes place at the Representational Level, where modifiers restrict the application of their head (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 109, 115, 121); this is what we find in the case of representational modifiers such as place and time indicators, which restrict the designation of the SoA and Episode, respectively, or adjectival modifiers, which restrict the designation of an Individual.

In sum, in FDG:

• prosodically integrated adverbs are analysed as restrictors (modifiers) at the Interpersonal or Representational Level;

• non-truth-conditional adverbs are analysed at the Interpersonal Level; they serve as speakers’ comments on the interpersonal unit they modify and are speaker-bound;

• truth-conditional adverbs are analysed at the Representational Level; they restrict the designation of the units they modify and are not necessarily speaker-bound;

• prosodically non-integrated expressions (adverbs, phrases and clauses realized as separate Intonational Phrases) are analysed as Discourse Acts at the Interpersonal Level.

The evaluative adverbs discussed above, however, do not fit this picture: they are prosodically integrated (part of a larger Discourse Act) and representational; as such they should be (and have been) analysed as restrictors at the Representational Level. At the same time, however, they are non-truth-conditional, i.e. they do not have a restrictive function. This means that they cannot be analysed as restrictors, and therefore not as modifiers in FDG.

Instead, I would like to suggest that, just as non-restrictive expressions at the Interpersonal Level are analysed as separate Discourse Acts, non-restrictive expressions at the Representational Level be analysed as (part of) a separate Propositional Content, as shown in (23′) for example (23):

(23) Having wisely said their good-byes in the wagon, … (COCA, fiction)

(23′) (pi: (epi: (ant ei: (fci: [(flj: say (flj)) (1xi)A (1ej)U] (fci)) (ei): (li) (ei)) (epi)) (pi))

(pj: (fcj: [(flk: wise (flk)) (ei)U] (fcj)) (pj))Add

In (23′), we have two Propositional Contents, pi and pj (corresponding to a single Communicative Content at the Interpersonal Level). The second Propositional Content (pj) consists of a Configurational Property (fcj) in which the Property ‘wise’ (flk) functions as a non-verbal predicate taking the SoA (ei) contained in the first Propositional Content as its argument (indicated by co-indexation).Footnote 11 The fact that the adverb wisely has scope over the place adverb in the wagon (li) shows that the argument of the non-verbal predicate must (at least) take the form of an SoA. The second Propositional Content cannot be used independently; it provides additional information about the unit in question. Therefore, it is analysed as a dependent Propositional Content with the semantic function Addition (Add). Since we are dealing with two separate Propositional Contents, neither affects the truth-conditionality of the other.

However, the argument of the non-verbal predicate within the second Propositional Content need not be an SoA. In those cases, for instance, where it occurs within the complement of an aspectual verb, it will take the form of a Configurational Property (fci in example (26a′)). When the evaluative adverb has scope over a time modifier, the argument will take the form of an Episode (epi in example (24b′)), and in those cases where it has scope over (and linearly precedes) an epistemic adverb, the argument will take the form of Propositional Content (pi in example (22b′)):

(26) (a) by continuing to foolishly drive on…

(26) (a′) (pi: … (fci: [(fli: drive-on (fli)) (1xi)A] (fci)) … (pi))

(pj: (fcj: [(flj: foolish (flj)) (fci)U] (fcj)) (pj))Add

(24) (b) Former Enron president wisely left firm in 1996,

(24) (b′) (pi: (past epi: (ei: (fci: [(fli: leave (fli)) (1×1)A (1×2)u] (fci)) (ei)) (epi): (ti) (epi)) (pi))

(pj: (fcj: [(flj: wise (flj)) (epi)U] (fcj)) (pj))Add

(22) (b) Last year in MUT I foolishly probably spent between $750-$1000.

(22) (b′) (pi: (past epi: (ei: (fci: [(fli: spend (fli)) (1xi)A (1xj)u] (fci)) (ei): (li) (ei)) (epi): (ti) (epi)) (pi): (flj: probable (flj)) (pi))

(pj: (fcj: [(flk: foolish (flk)) (pi)U] (fcj)) (pj))Add

In this analysis, the evidence from clausal position, scope relations and embedding is not conflicting: as non-verbal predicates in a separate Propositional Content, evaluative adverbs can take different representational units (from the Configurational Property upward) as their argument. This would thus explain the lack of consensus among linguists when it comes to the analysis of these adverbs: in many cases, evaluative adverbs do indeed modify the SoA (cf. Cinque Reference Cinque1999; Ernst Reference Ernst2002; Mittwoch et al. Reference Mittwoch, Huddleston, Collins, Huddleston and Pullum2002; Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008); in other cases, however, they scope over the Propositional Content (cf. Haumann Reference Haumann2007: 411; Dik et al. Reference Dik, Hengeveld and Nuyts1990; Ramat & Ricca Reference Ramat, Ricca and van der Auwera1998). In addition, they may scope over the Episode and the Configurational Property.

Finally, note that the analysis proposed can also be extended to those cases where the evaluative adverb precedes an attributive adjective within an NP (see also Lewis Reference Lewis2018), as in the following examples:

(30)

(a) When I was a child and then older she told me increasingly long and horrific stories about unlucky, stupidly curious children; trespassing, beer drinking, vandalism-on-the-brain teenagers; …. (COCA, fiction)

(b) Soros thinks America's approach to drug abuse is stupidly punitive. He supports programs to give away clean needles. (COCA, spoken)

It will be clear that in both these cases a manner reading of the adverb is not intended: in (30a) the children in question were not curious in a stupid manner; instead it was stupid of them to be curious; similarly, in (30b) Soros does not object to the fact that America's approach is being punitive in a stupid manner – he objects to the fact that it is punitive, which he considers a stupid thing. As in the case of evaluative adverbs with clausal scope, the adverbs in these examples are non-truth-conditional. This means that the best way to analyse these adverbs is as follows:

(30) (a) stupidly curious children

(30) (a′) (mxi: [(fli: child (fli)) (xi): (flj: curious (flj)) (xi))

(pi: (fci [(fll: stupid (fll)) (fcj: [(flj) (mxi)U] (fcj))U] (fci)) (pi))Add] (xi))

Here the Individual xi has been provided with a configurational head, consisting, on the one hand, of the first and second restrictors (‘x is a child and curious’), and, on the other, of a separate Propositional Content. This second, dependent, Propositional Content is headed by a Configurational Property (fci), consisting of a non-verbal predicate (the Property fll ‘stupid’), which takes as its argument another Configurational Property (fcj), consisting of the non-verbal predicate curious (flj, co-indexed with the second restrictor) and its argument (xi, co-indexed with the NP as a whole). The second Propositional Content thus provides the additional information that ‘the children (xi) being curious (flj) was stupid (flk)’.

4 Non-restrictive attributive modifiers

4.1 Truth-conditionality / non-restrictiveness

As has often been pointed out, not all prenominal adjectives function as restrictors (e.g. Jespersen Reference Jespersen1924: 111–12; Bolinger Reference Bolinger1967, Reference Bolinger1989: 198; Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 1239; Ferris Reference Ferris1993; Biber et al. Reference Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan1999: 242; Huddleston et al. Reference Huddleston, Payne, Peterson, Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1353; Larson & Maruśić Reference Larson and Marušič2004: 275; Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Haegeman and Stavrou2007: 334–5; Cinque Reference Cinque2010: 6–7; Matthews Reference Matthews2014: 168). These non-restrictive adjectives come in various kinds. Firstly, there are adjectives like poor in Poor you!, or mere in a mere child, which have a pragmatic function, and in FDG are analysed at the Interpersonal Level (poor as a modifier of the Referential Subact, expressing the speaker's sympathy towards the referent, and mere as a mitigating operator specifying the Ascriptive Act evoking the property ‘child’). As interpersonal elements, they will not be discussed here.

Non-restrictive adjectives can, however, also be representational in nature, in which case they designate a property to be attributed to a referent (set). Thus, whereas it is typically assumed that in a phrase like a blue car, the first restrictor ‘car’ restricts a set of Individuals to those with the Property ‘car’, with the second restrictor ‘blue’ further restricting the referent set to those cars that have the additional Property ‘blue’ (e.g. Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 109, 115; see also Dik Reference Dik and Hengeveld1997: 132–6), this need not always be the case.

Non-restrictive representational adjectives can be divided into (at least) two groups. The first group consists of adjectives denoting intrinsic, necessary features of the referent (set) denoted by the noun, as in white snow (white being a prototypical feature of snow) or in Bouchard's (Reference Bouchard2002: 94–5) example of les flegmatiques brittaniques, where adjective and noun together describe a generic concept (the assumption being that all Britons are phlegmatic; cf. Ferris Reference Ferris1993: 118). In these cases, the adjective does not restrict the denotation set of the noun (i.e. there is no intersection between the set of Britons and the set of entities with the property ‘phlegmatic’). Bouchard suggests that the noun does not actually have its own denotation set at all; instead, adjective and noun together form one complex property, combining at the level of the intension to denote a single set (Bouchard Reference Bouchard2002: 95).

Note, however, that although these adjectives are indeed non-restrictive, denoting intrinsic properties of the referent(s) denoted by the noun, they do still denote a property of the overall referent: it is still the Britons that are phlegmatic, not their Britishness. In this respect they differ from true intensional phrases like the present president or a criminal lawyer (see also section 4.3 below). Moreover, in the majority of cases the non-restrictive adjective does not combine with the noun to denote a ‘unitary concept’ (Givón Reference Givón1993: 268), but instead assigns an additional, non-intrinsic property to a referent. In those cases, there is no reference to a generic concept; instead, a property is being assigned to a specific discourse referent, one that is typically assumed to be identifiable for the hearer (retrievable or inferable from previous discourse of the immediate or larger situation;Footnote 12 e.g. Hawkins Reference Hawkins1978; Prince Reference Prince and Cole1981). Examples of this second group of non-restrictive adjectives can be found in example (2) (repeated here for convenience).

(2)

(a) There were seven of us, my three kids, wife, my father-in-law, my old mother and me (COCA, spoken)

(b) Our friendly staff is here to make sure that you have an outstanding experience. (www.brecksvilledermatology.com/meet-us/our-friendly-staff/)

(c) The prolific Toni Morrison returned this year with her first novel set in the current time. (COCA, magazine)

In (2a), the identity of the referent of the NP as a whole can be assumed to be inferable for the hearer on the basis of the sense of the noun mother and the presence of the possessor my. The adjective old, being non-restrictive, does not contribute to the identification of the referent, but is added because the speaker considers this property to be relevant in the given discourse context. In (2b), the adjective friendly is potentially ambiguous, but the context clearly favours a non-restrictive reading, in which all the people we employ (again an inferable set) have the property friendly. Finally, in (2c), where the NP is headed by a proper name, the referent is assumed to be identifiable on the basis of assumed shared long-term knowledge; the adjective once again plays no role in the identification process.

In what follows, discussion will be restricted to this second group of non-restrictive adjectives; both groups, the generic-concept and specific-discourse-referent adjectives, will, however, be provided with the same analysis. In both cases it will be assumed that the head noun does have its own denotation, which is identical to that of the NP as a whole, and that the non-restrictive adjective provides an additional property. The only difference between the two groups is that on the generic use, the adjective, denoting a prototypical feature of the referent, is discourse-new, but hearer-old (part of speaker-hearer shared knowledge; Prince Reference Prince, Mann and Thompson1992), whereas on the discourse use the adjective denotes information that is both discourse-new and hearer-new. In both cases, however, the adjective provides information that is regarded as relevant (salient) in the given discourse.

So far, FDG has analysed all prenominal adjectives as modifiers, typically at the layer of the Individual, as in the case of an expensive watch in example (31):

(31)

(a) an expensive watch

(b) (1xi: (fli: watch (fli)) (xi): (flj: expensive (flj)) (xi))

In (31b) the adjective expensive functions as a modifier of the referent (Individual) represented by the variable xi: the Nominal Property ‘watch’ (fli) functions as the first restrictor (the head), the Adjectival Property ‘expensive’ (flj) as the second restrictor (the modifier). The relation between head and modifier is thus one of intersection, restricting the referent set to those entities that are both watches and expensive.Footnote 13

Such an analysis is, however, clearly inappropriate in the case of the non-restrictive adjectives in (2), where the adjective merely adds a property to a previously established set of entities. Here the relation between head and modifier is not intersective: rather than referring to a subset of entities with the property ‘our staff’ who have the property ‘friendly’, the property ‘friendly’ is predicated of all the entities with the property ‘(our) staff’.Footnote 14 From this it follows that non-restrictive (non-truth-conditional) adjectives should not be analysed as restrictors, i.e. not as modifiers. This of course raises the question of how to deal with these adjectives.

Note finally that this phenomenon is not restricted to adjectives, but also applies to prenominal past participles: in (32a) there is only one, identifiable sun, which is at that moment hidden, and in (32b) the most likely reading is that there is only one curtain between the room and the balcony, which is drawn. In both cases, therefore, the past participle does not restrict the set of potential referents.

(32)

(a) Across the road the cemetery hill shimmered under the last rays of the hidden sun. (COCA, fiction)

(b) Air admitted from the balcony under the folds of the drawn curtain grazes his face. (COCA, fiction)

4.2 Formal features

What is important from the point of view of FDG is that the non-restrictiveness of prenominal adjectives and past participles (henceforth referred to as adjuncts)Footnote 15 is also reflected in their formal behaviour. Starting at the Morphosyntactic Level, we find that in those cases where an adjunct can go in both prenominal and postnominal position, there is a strong tendency, in both Germanic and Romance languages, for non-restrictive adjuncts to precede the noun (e.g. Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Haegeman and Stavrou2007: 334; Cinque Reference Cinque2010: 7–8). Thus, in Romance languages, which more readily allow for both positions, the postnominal position is typically used to code restrictivity, while a prenominal position triggers a non-restrictive reading.Footnote 16, Footnote 17 In the following example from Portuguese, for instance, the adjunct hospitalar, being used restrictively (indicating a particular kind of discharge), is in its usual postnominal position, whereas the adjective polémica, in prenominal position, indicates that the property denoted is presupposed (‘the law, which everyone knows is controversial, …’), and is, as such, used non-restrictively; placing it in postnominal position – a lei polémica – would trigger a restrictive reading (the controversial law as opposed to other, more generally accepted, ones) (Lachlan Mackenzie, p.c.).

(33) O Presidente d-a República teve alta

m.def president of-f.def republic have.pst.prf.3sg all.clear

hospitalar este domingo. Ainda no hospital Curry Cabral,

medical this Sunday still in.m.def hospital Curry Cabral

em Lisboa, Marcelo fal-ou sobre a polémica

in Lisbon Marcelo speak.pst.prf.3sg on f.def controversial

lei que alter-a o financiamento a-o-s partido-s.

law rel alter- prs.3sg m.def financing to-m.def-pl party-pl

(http://sicnoticias.sapo.pt/pais/2017-12-31-Marcelo-vai-analisar-lei-do-financiamento-dos-partidos)

‘The President of the Republic was discharged from hospital this Sunday. While still in Lisbon's Curry Cabral Hospital, President Marcelo spoke about the controversial law that alters the financing of the parties.’

In English, which is far less flexible when it comes to the placement of (unmodified) adjectives within the NP, the postnominal position is highly restricted (basically to adjectives ending in -ible/-able and to certain groups of past participles). However, in those cases where an adjective or past participle can occur in both positions, the postnominal position cannot trigger a non-restrictive interpretation (e.g. Bolinger Reference Bolinger1967; Larson & Maruśić Reference Larson and Marušič2004: 275; Matthews Reference Matthews2014: 168). This is shown in example (34) (from Larson & Maruśić Reference Larson and Marušič2004: 275) for the adjective unsuitable:

(34)

(a) Every unsuitable word was deleted.

Restrictive: ‘Every word that was unsuitable was deleted’.

Non-restrictive: ‘Every word was deleted; they were unsuitable’.

(b) Every word unsuitable was deleted.

Restrictive: ‘Every word that was unsuitable was deleted’.

#Non-restrictive: ‘Every word was deleted; they were unsuitable’.

Some attested examples are given in (35). Although in (35a) available is strictly speaking ambiguous, the context triggers a non-restrictive reading. Placing the adjective in postnominal position, however, leads to a restrictive reading (incompatible with the demonstrative these).

(35)

(a) The advantages and disadvantages of these available options are briefly discussed here. (COCA, academic)

(b) The advantages and disadvantages of *these/the options available …

In English, the difference between the two positions in terms of restrictivity is clearest in the case of past participles, which occur more freely in both positions. Consider, for instance, the two examples in (36), both of which contain the combination of the past participle arrested and the noun men. In (36a) the past participle is used prenominally, which, in principle, allows for both a restrictive and a non-restrictive interpretation; the context, however, favours a non-restrictive reading (there is only one relevant (and inferrable) set of men, namely those listed in the preceding sentence). In (36b), on the other hand, the past participle in postnominal position is used restrictively, in order to enable the listener to identify the set of men in question.

(36)

(a) Look what happened here in Brooklyn when police moved in on this chop shop. They made arrests, sent the arrested men to the police station and before they could finish their paperwork, one of the arrested men was back, (COCA, spoken)

(b) The families are very skeptical about all this. The mother of one of the men arrested said if my son were a terrorist, the Earth would open up and swallow me. The men will appear in court here today (COCA, spoken)

In many cases, however, ambiguity between the two readings remains, due to the fact that whereas the postnominal position triggers a restrictive reading, the prenominal position allows both interpretations. This means that in languages like English, where most adjectives, as well as many past participles, can only occur prenominally, position is not very helpful in coding the (non-)restrictiveness of the adjective. In some cases, however, prosodic features may provide a clue. Thus, non-restrictive adjuncts cannot be used contrastively (since all members of the set designated by the noun have the property designated by the adjunct, there is no contrast with members that do not have this property), whereas restrictive adjuncts can: the examples in (37a), where only a non-restrictive reading is available, are unacceptable, while the contrastive adjectives in (37b) trigger a restrictive reading:

(37)

(a) *my OLD mother (see (2a)); *the HIDden sun (see (32a))

(b) every UNsuitable word (see (34)); these aVAILable options (see (35a))

In non-contrastive contexts, however, there seems to be little difference in prosodic realization between restrictive and non-restrictive prenominal adjectives,Footnote 18 which means that their interpretation (as restrictive or non-restrictive) depends entirely on context. Nevertheless, given the positional and prosodic restrictions described above, it will be clear that non-restrictive adjectives and past participles cannot be given the same analysis as restrictive ones.

4.3 Non-restrictive prenominal adjectives as (parts of) separate Propositional Contents

The adjectives and past participles discussed in the previous sections are clearly representational: they do not express a ‘speaker's subjective attitude with respect to the referent being evoked’ (Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 121), but have a descriptive function, denoting an additional property of the entity (or set of entities) denoted by the head (cf. Hengeveld & Mackenzie Reference Hengeveld and Mackenzie2008: 109, 115). Nevertheless, they are non-restrictive, and as such cannot be analysed as restrictors (i.e. as modifiers) at the Representational Level.

Instead, we can apply the same analysis as proposed for evaluative adverbs to these adjuncts; the only difference is that in this case the argument of the non-verbal predicate in the separate Propositional Content is an Individual:

(38)

(a) The prolific Toni Morrison returned this year … (= (2c))

(b) (pi: (past epi: (ei: (fci: [(fli: return (fli) (xi)A] (fci)) (ei)) (epi): (ti) (epi)) (pi))

(pj: (fcj: [(flj: prolific (flj)) (xi)U] (fcj)) (pj))Add

The proposed analysis accounts for the fact that the Property ‘prolific’ is non-restrictive (non-truth-conditional): rather than restricting the denotation of a layer within a Propositional Content pi, this Property functions as a non-verbal predicate in a separate, dependent Propositional Content pj, providing additional information about a particular layer in pi (in this case an Individual).

The question now arises whether the analysis may also apply to the next layer down, that is to the Nominal Property (fl) functioning as the head of the Individual. This does indeed seem to be the case in NPs for so-called intensional adjectives. So far, the discussion of non-restrictive adjectives in this section has been restricted to extensionally used adjectives, i.e. adjectives used to assign a property to the referent of the NP as a whole; e.g. old in an old friend when it refers to the age of the friend in question. On an intensional reading, the adjunct does not designate a property of the referent, but rather modifies the property designated by the noun: it is the friendship that is old, not (necessarily) the friend.Footnote 19 The distinction is particularly clear in NPs with deverbal nouns, such as a beautiful dancer, where beautiful can either be interpreted extensionally (the person who dances is beautiful) or intensionally (describing the manner in which the action of dancing is performed).

Like (non-)restrictiveness, the intensional-extensional distinction is relevant for the position of the adjunct in the NP, in that, in languages where both positions are generally available (such as Romance languages), only prenominal adjectives can have an intensional reading (e.g. Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Haegeman and Stavrou2007: 306, 329–30; Cinque Reference Cinque2010: 9). Note, however, that the two distinctions need to be kept apart (see Alexiadou et al. Reference Alexiadou, Haegeman and Stavrou2007: 336), as the restrictive/non-restrictive distinction applies to both extensional and intentional adjuncts.Footnote 20 This is shown in examples (39) and (40) for the adjective old in combination with the noun friend. In both examples, old is used intensionally, modifying the friendship, not the friend. In (39a), it is used restrictively, as is clear from the fact that it contrasts with the adjective new. In that case the noun phrase an old friend will be represented as in (39b), where the Adjectival Property ‘old’ (flj) modifies the Nominal Property ‘friend’ (fli), with the two properties together restricting the denotation of the Individual (xi). The adjective old thus functions as a restrictor at the layer of the Lexical Property. The analysis is therefore the same as that of the extensionally used adjective expensive in example (31b), except that it scopes over a different layer of analysis.

(39)

(a) And while Anderson is an old friend, Tech coaches made a new one in Lou d'Almeida – Marbury's AAU coach (COCA, newspaper)

(b) (1xi: (fli: friend (fli)): (flj: old (flj)) (fli)) (xi))

In (40a), on the other hand, the intensional adjective old is used non-restrictively: it does not restrict the denotation of the head noun, but assigns an additional Property to its denotation. It is therefore analysed in the same way as the other non-restrictive adjuncts discussed in this section, except that the argument of the non-verbal predicate in the dependent Propositional Content is now a Lexical Property (the Nominal Property ‘friend’, flj, in (40b)).

(40)

(a) Suddenly those eyes were distracted by the flair of a familiar crimson cloak. ‘Doctor,’ Marlowe called out, stepping into the light to greet his old friend. (COCA, fiction)

(b) (pi: … (ei: (fci: [(fli: greet (fli)) (xi: (fcj: [(flj: friend (flj)) (xj)Ref] (fcj)) (fci)) (ei)) … (pi))Footnote 21

(pj: (fck: [(flk: old (flk)) (flj)Ref] (fck)) (pj))Add

The examples discussed in this section thus not only show that the analysis proposed for evaluative adverbs can be fruitfully applied to non-restrictive prenominal adjectives and past participles, but also allow us to capture the interaction between restrictive/non-restrictive readings on the one hand, and intensional/extensional readings on the other.

5 Conclusion

This article has been concerned with two groups of (prosodically integrated) modifiers: evaluative (‘subject-oriented’) adverbs and non-restrictive prenominal adjectives and past participles. What these modifiers have in common, and what makes them interesting, is that both are representational (i.e. low-level) elements and non-truth-conditional/non-restrictive. In the case of the evaluative adverbs, it has been shown that the non-truth-conditional status of these adjuncts triggers a number of specific formal features (in terms of clefting, questioning and scope of (predication) negation, ellipsis and pronominalization), while other syntactic features (e.g. clausal position and distribution) show them to be representational. When it comes to the question of exactly which representational layer these adverbs belong to, however, evidence turns out to be contradictory. Similarly, it has been shown that many prenominal adjectives and past participles, which are clearly representational (attributing properties to the referent or its nominal head), are at the same time non-restrictive (and as such non-truth-conditional). Here, too, the non-restrictive nature of these elements is reflected in their formal behaviour, imposing restrictions on their phrasal position and prosodic realization. Theoretical accounts of these two groups of modifiers, however, do not reflect the semantic, syntactic and formal properties of these adjuncts, and the interaction between these features, in a principled and insightful manner.

FDG is no exception, as it does not have a way of dealing with non-truth-conditional elements that are at the same time representational elements; so far all these adverbs, adjectives and past participles have been analysed as restrictors (modifiers) of the head at a particular representational layer. In this article, I have proposed a new analysis of these non-truth-conditional/non-restrictive elements in which they are dealt with as non-verbal predicates in a separate, dependent Propositional Content, predicating an additional property of a particular layer in the main Propositional Content. The argument of the non-verbal predicate can be any representational layer: a Lexical Property or Individual in the case of non-restrictive adjectives and past participles, and a Configurational Property, SoA, Episode or Propositional Content in the case of evaluative adverbs. Analysing these elements as (parts of) separate Propositional Contents thus not only captures both their non-truth-conditional/non-restrictive nature and their representational status, but also brings out the similarities between the two apparently quite different groups of adjuncts discussed. In the case of evaluative adverbs, the analysis moreover offers an explanation for the conflicting syntactic evidence (in terms of clausal position/scope and embedding).