Introduction

The present study focuses on the word cheeky which, in the past few decades, has taken on a new meaning of ‘mildly illicit’ in addition to, and partly overtaking, its original meaning of ‘impudent’. We examine how this semantic change is spreading in different age groups and in different parts of the English-speaking world. As we demonstrate, the newer meaning of cheeky is associated with younger speakers, so we examine whether this correlates with different age groups’ understanding of the new form. Furthermore, cheeky ‘impudent’ was used more frequently in the United Kingdom than in North America. If that earlier meaning was already marked for North America, how is the newer meaning cheeky ‘mildly illicit’ understood by speakers there?

Our starting point for this project and our interest in these two main aspects stem from a phrase that, in 2015, went viral on the internet: cheeky Nando's. A culture divide became apparent, not just because Nando's (a restaurant chain) was not widespread in the United States, but because cheeky is a very British word (example 1). UK users were happy to ‘help’ their US friends understand the phenomenon of a ‘cheeky Nando's’ by throwing more British jargon into the definitions (example 2).Footnote 1

(1) Obviously we all know what a cheeky Nando's is. It's when you go to Nando's, but it's cheeky.

(White, Reference White2015)

(2)

(Ahrned, 2015)

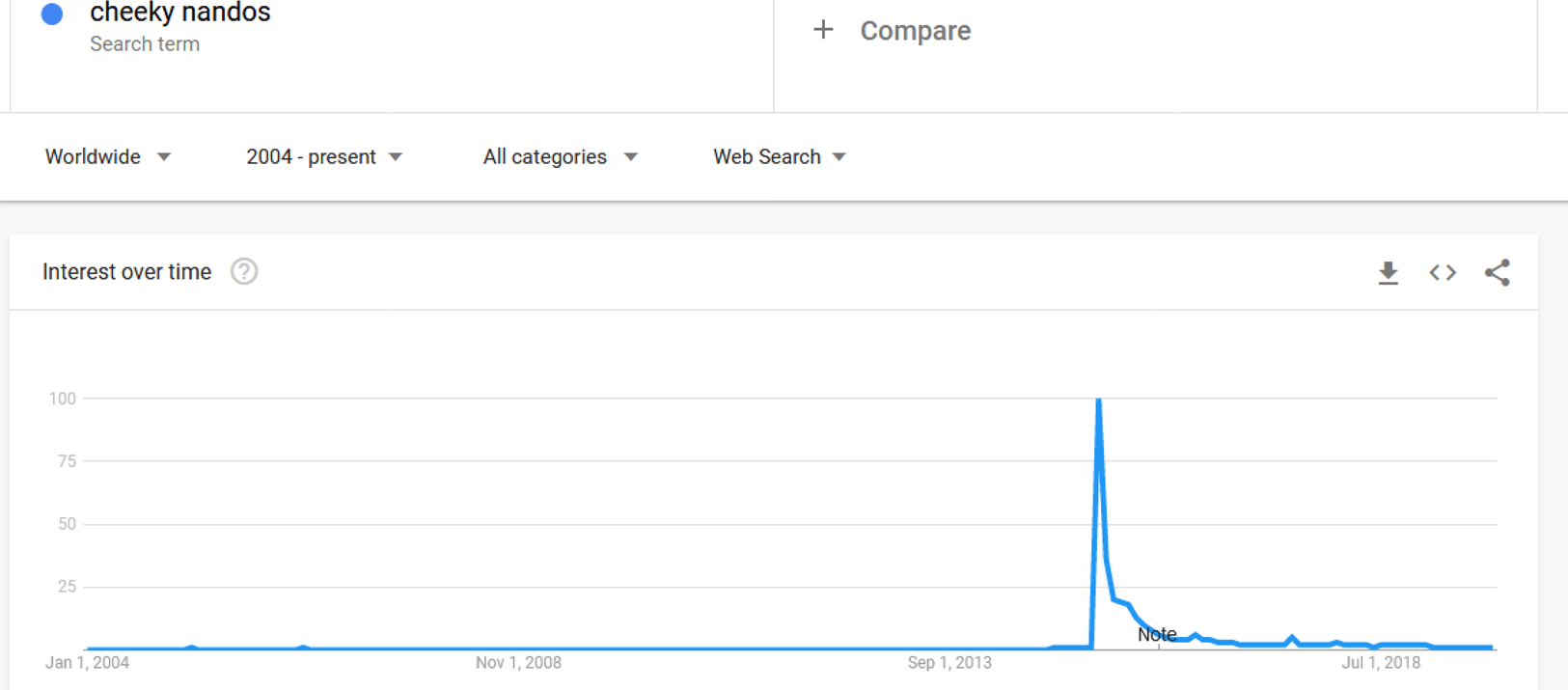

These multiple Tumblr threads and tweets about cheeky Nando's underline that the term was in the public consciousness at that point. In fact, an automated extraction onto a spreadsheet of all the public tweets containing the word cheeky (see Durham, Reference Durham, Durham and Morris2016 for the methodology used) in May 2015 crashed in less than a week because of the numbers (there were around 117,000 tweets with the term). A second extraction looking for cheekynandos (mostly occurring as #cheekynandos) collected over 36,000 tweets (including numerous retweets) in the same timeframe. Figure 1 charts the increase of searches for cheeky nandos in 2015.

Figure 1. WWW searches for ‘cheeky nandos’ over time (Google, 2019)Footnote 2

The popularity of the hashtag and the widespread discussion of the term, made it an ideal time to examine the different contexts people felt cheeky was used in and how its meaning was shifting, as people were already aware of it and thinking about it.

Tracking language change

While phonological and morphosyntactic change have been extensively studied through a sociolinguistic lens, this has not been the case so much for lexical change (Robinson, Reference Robinson2012), partly because specific terms do not occur as often in sociolinguistic interviews as phonemes and morphosyntactic constructions. To get around this issue, we used an online acceptability judgement questionnaire completed by 372 participants to study how cheeky was used. We found a clear effect of age and location on the acceptability ratings, with younger speakers and UK speakers favouring the newer use. Our results demonstrate that although the new meaning is being acquired by respondents on both sides of the Atlantic, it is a change in progress and a British innovation.

Our aim is not solely to examine how cheeky is used, but also to establish what it can tell us about semantic variation and change more generally. How willing are people to incorporate new forms into their repertoire and how quickly are they able to do so? The findings have implications not only for future viral change, but also for slower types of semantic change. Additionally, in an ever more connected world, it is valuable to know how new meanings spread from one English-speaking country to another. Cheeky is a particularly interesting case as the spread is from the UK towards the US rather than in the opposite direction (see Murphy, Reference Murphy2018: 40–5 for a discussion of American attitudes to Briticisms).

Meanings of cheeky

We are concerned here with the two meanings of cheeky as defined in OED sense 1a (3) and OED sense 2b (4):

(3) Impudent or insolent, esp. in speech; forward or presumptuous, esp. in a way that is amusing or disarming.

Cheeky little chap, aren't you. It's your immaturity of course. (J. P. Donleavy, Destinies Darcy Dancer x. 119, 1977)

(4) (Chiefly Brit) Of an item of food, drink, etc., or an activity: mildly irresponsible or illicit; indulgent.

Bourke that had his cheeky pint with George Blake in the King's Arms. (M. Curtin, League Against Christmas 87, 1989)

We refer to these respectively as the ‘old’ and ‘new’ meanings of cheeky. The earliest citation for the old meaning of cheeky (3) dates back to 1838, but the new meaning only dates back to 1989 (4). Because the older meaning has been around about 150 years longer than the newer meaning it is likely to be deemed more ‘acceptable’ by respondents.

Semantic change

This meaning change is a type of semantic broadening, where the adjective comes to refer to a wider range of referents than previously allowed. In this case, the old meaning of cheeky (5)–(6) can only refer to people or anthropomorphised animals.

(5) How cheeky r some people tho

Footnote 3

Footnote 3(6) Much love you cheeky monkey! xx

The new meaning of cheeky must apply to a non-animate entity or activity (7)–(8).

(7) Meeting this top guy and having a cheeky flirt haha

(8) cheeky spoons with the lasses

Footnote 4

Footnote 4

The pint in a cheeky pint is not acting in a cheeky way, but the person who goes for the pint may be. The core meaning, ‘naughty’, remains, but rather than an individual-level predicate describing a characteristic of a person (as in Sara is cheeky), new cheeky is a stage-level predicate describing an event (Sara was being cheeky to go for a pint).Footnote 5

Sociolinguistic change

Sociolinguistics presupposes that change is primarily due to social factors. New forms are picked up by younger speakers first (Bailey, Reference Bailey, Chambers, Trudgill and Schilling–Estes2002). Women are simultaneously conservative with respect to prestigious features and innovative with respect to incoming but not stigmatised features (Labov, Reference Labov2001). Different dialects pick up new lexical items at different points and in some cases one variety transmits a new lexical item to the other.

Due to how the viral meme of cheeky Nando's played out, we expect that there will be differences between speakers of British English, American English and possibly other varieties of English. We also expect that the newer form will be used more by younger people than older people, not merely because it is a newer form, but also because the viral spread of the form is likely to have been seen more by younger generations than older ones. In general, sites where memes are widely shared have a younger user base. For instance, 41% of TikTok users are aged 16–24 (Oberlo, 2019), while just 24% of Facebook users fall into this age group (Statista, 2019).

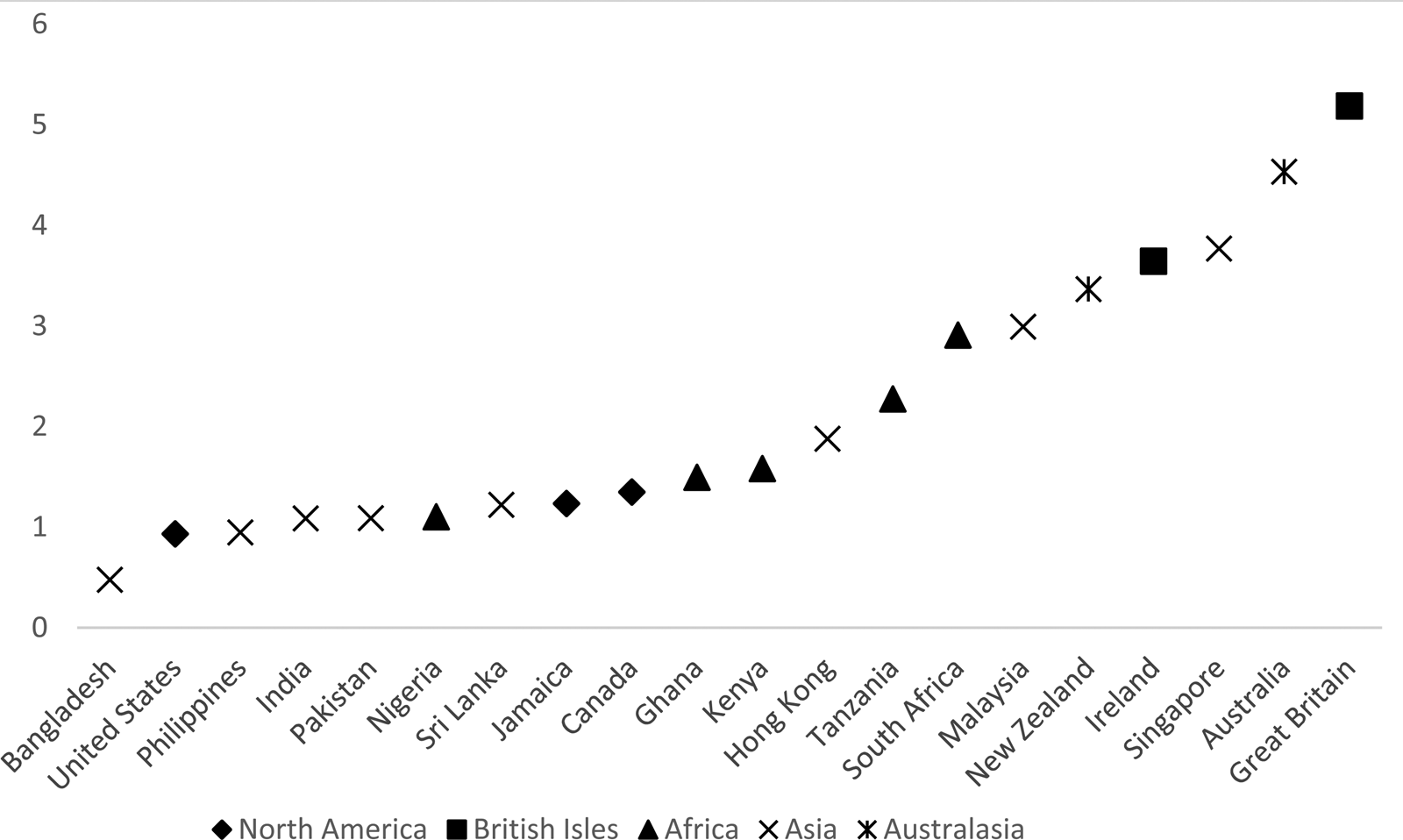

Before examining the differences between the new and old uses of cheeky, we used an online corpus to get a sense of the overall use of cheeky across the English-speaking world (GloWbE, 2013). Figure 2 presents the instances of cheeky per 1 million words for each regional dataset.Footnote 6

Figure 2. Instances of cheeky per 1 million words across different regional corpora

As expected, the United States and Canada have much lower rates of cheeky than Britain, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. The United Kingdom has around five times more instances per million words than the United States. This data was compiled between 2012 and 2013 and no doubt includes new and old uses of cheeky which we are not attempting to disambiguate. However, the dataset suggests that the lower rate of use in North America combined with the semantic shift occurring first in the UK will together contribute to North Americans being less likely to use and understand the new meaning of the term.

Method

Because of the difficulty in obtaining frequent enough instances of lexical variation to study, we used a response-based approach. We asked participants to rate a set of sentences (discussed below) on a scale from 1 ‘Awkward’ to 6 ‘Natural’. The participants were told that the sentences might seem informal and were asked if they would use them in any context, such as chatting to friends on the internet. We recruited the participants online by sharing the questionnaire (hosted on a Google form) on social media.

We obtained the data over two collection periods in 2015 (May and July). We modified three sentences between the first and the second collection period, as we found that the ungrammatical sentences were not ungrammatical enough, i.e. we were getting good ratings for uncontroversially ungrammatical sentences. While the participants in the first collection period came primarily from our own extended social networks, those in the second period came from a wider pool, as our preliminary findings had appeared in an article in Mental Floss (McCulloch, Reference McCulloch2015), which included a link to the updated questionnaire.

Sentences

The questionnaire consisted of 35 sentences which we created to fit into four categories: the old (9) and new (10) meanings of cheeky, plus a category for ‘extended’ meaning (11), where the new meaning is applied to an activity that could not easily be considered illicit, and ungrammatical sentences (12).

(9) He's a cheeky monkey

(10) Let's go for a cheeky Nando's

(11) Let's go for a cheeky walk

(12) He's cheeky a boy

The ungrammatical sentences were included to provide us with a baseline of acceptability and also as a way to ensure that the respondents were paying attention. The extended meaning set was intended to allow us to establish whether the new meaning was spreading further, but also to get a gauge of people's likelihood of simply accepting new forms, particularly for the North American respondents who were expected to use the new meaning less frequently than UK respondents.

Sentences were automatically randomised for each participant. We also collected information about where the participants were from, their age and their gender. We also included a section where respondents could include their own comment about their own use and perceptions of cheeky. We discuss the results of the comments after the quantitative analysis.

In total, 372 people responded, 140 in May and 232 in July. We tested (with unpaired t-tests) whether there were differences in the responses in the two periods, taking region, age and so on into account and none were found, so we present the results from the two periods together. We calculated mean ratings for each sentence and each sentence category. These allow us to compare the different sentences and sentence types together and to establish whether there were differences between the different social categories.

Results

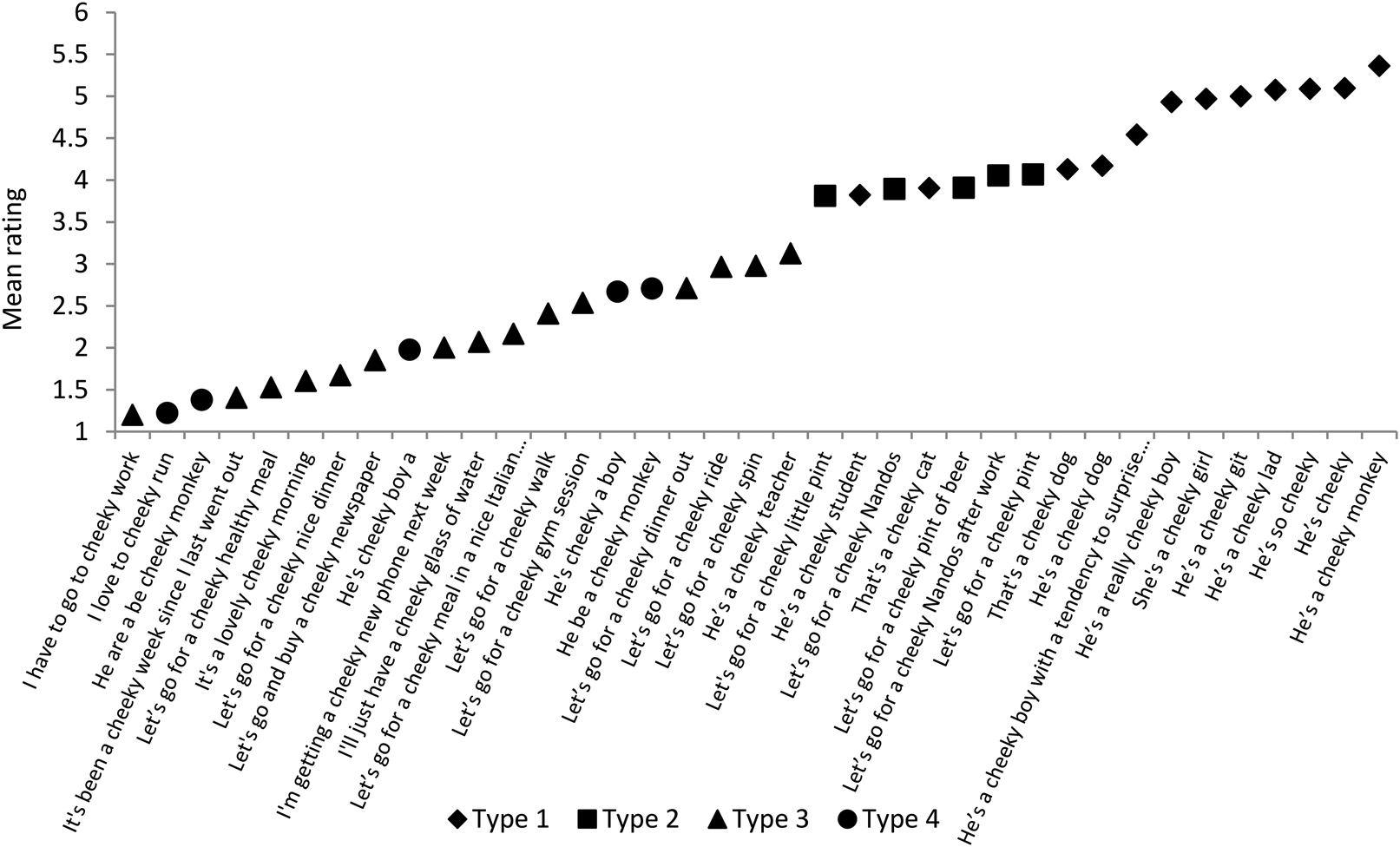

We label old meanings of cheeky as Type 1, new meanings as Type 2, extended meanings as Type 3 and ungrammatical meanings as Type 4. Although we do not present the full list of sentences in each figure, Figure 3 contains every sentence so that they are all presented at least once. The figures contain 38 sentences as they present those from the original data collection point and those of the second point (three are different).

Figure 3. Overall sentence ratings for all participants from all regions

We do not have an even balance of sentence types. There are more extended and ungrammatical contexts than old and new ones because part of our aim was to establish how far the new meaning was extending, i.e. beyond actions or things which could possibly have an illicit/naughty sense, such as ‘a healthy meal’, but also into more complicated grammatical structures, such as ‘a cheeky Nando's after work’).

Overall results

Figure 3 presents the overall sentence acceptability ratings for all participants together, clearly demonstrating that there are differences in acceptability between the Type 1 and 2 sets and the Type 3 and 4 sets.

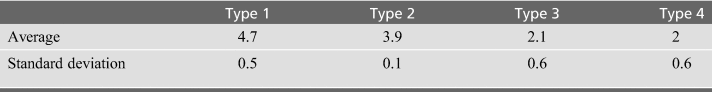

The difference between the types with respect to acceptability ratings is confirmed in Table 1, which provides the sentence type average ratings and the standard deviation within each.

Table 1: Overall acceptability ratings by sentence type

Some Type 1 responses score lower than some Type 2 responses, namely those that have to do with cheeky cats, dogs and students. As noted above, cheeky is less often applied to animals. He's a cheeky monkey, which has the highest overall score (5.36), is a special case as the expression is a fixed phrase used primarily to talk about babies rather than monkeys. If we exclude the examples with cats, dogs and the cheeky student, which out of context may seem like a less likely sentence, the Type 1 sentences all score substantially higher than the Type 2 ones indicating that, as expected, the older meaning is more acceptable than the new one.

There is also a substantial drop between the lowest-scoring Type 2 sentence (3.81) and the highest-scoring Type 3 sentence (3.12). This underlines that both the old and new meanings are entrenched in speakers’ repertoires. Interestingly, the standard deviation found in Type 2 responses is very narrow, which suggests that there is a greater consensus in the rating of these sentences than for other sentences. While there is a clear demarcation between Type 1 and Type 2 rates, Type 3 and Type 4 have similar averages, suggesting that semantic and grammatical infelicitousness are viewed similarly by our respondents. The lowest-rated sentence, I have to go to cheeky work, is both infelicitous and ungrammatical. The next two sections break the results down by location and age.Footnote 7

Location

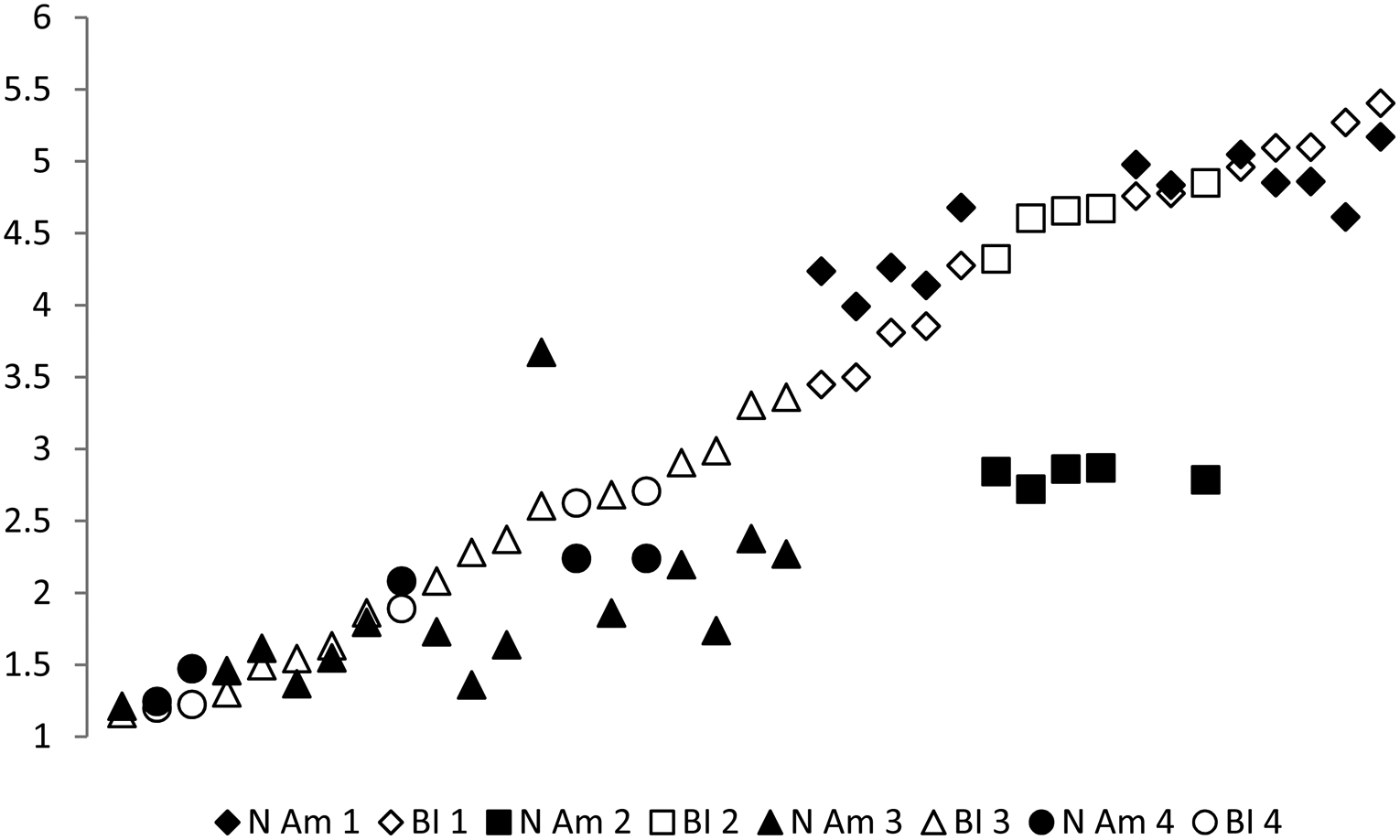

Of the 372 responses, 181 were from Britain and Ireland,Footnote 8 122 from North America,Footnote 9 45 were other native English speakers,Footnote 10 and 24 were non-native English speakers. As there were fewer responses outside of Britain and Ireland on the one hand, and North America on the other, Figure 4 only presents the results for these two groups (Table 2 provides the average score for each type for all four groups). This figure again uses different symbols for the different sentence types, and the sentences are ordered on the x-axis from the lowest scoring to the highest scoring for the Britain and Ireland respondents. Although the GloWbE results suggested that Canadian speakers were likely to use cheeky more than US speakers, the number of responses we have make it difficult to establish whether this affects the ratings and so we have not attempted to separate speakers from these two countries. Our decision to merge Ireland and the United Kingdom is based on the same principle.

Figure 4. Sentence ratings for participants from North America and Britain and Ireland

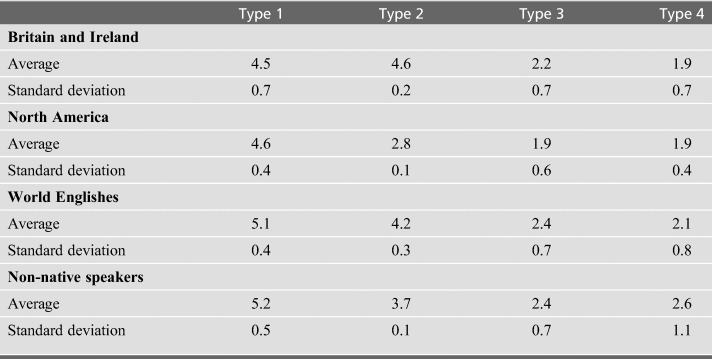

Table 2: Overall acceptability ratings by sentence type and region

Figure 4 and Table 2 show that there are differences in acceptability ratings for the North American and European groups, particularly in terms of Type 2 sentences as expected, where the UK/Ireland ratings averaged 4.6 compared to the North American rating of 2.8. For Type 1 sentences, the overall score for these respondents is very similar, except that North American speakers were much more accepting of the original use when applied to dogs, cats and students. UK speakers rated these lower than the very highly rated cheeky gits, monkeys and predicative cheeky, but North American speakers rated them all the same, at approximately the same level as their other Type 1 sentences.

However, whereas the average for Type 2 sentences is very close to Type 1 for the British and Irish respondents (4.5), this is not the case for the North American respondents or the other two groups. This confirms our intuition that the newer forms of cheeky are more acceptable (because they are more used) in the United Kingdom and Ireland. All four groups rate Type 3 and Type 4 sentences much lower. Importantly, even though North American speakers were much less accepting of the Type 2 sentences than UK speakers, they still rated them higher than Type 3. This shows that there is some transfer or acquisition of the new meaning, even if it has not taken hold.

North American respondents also rated He's a cheeky teacher much higher than the UK respondents (in fact, we categorised this as Type 3, consistent with its British rating, but its North American rating is nearly as high as Type 1). Types 3 and 4 were low-rated (1–3) for all respondents, but again a regional difference was apparent: North American speakers gave more uniform ratings between Types 1 and 2, while UK speakers were more accepting of cheeky spins, gym sessions, dinners out and similar activities. Unsurprisingly, the lowest-scoring sentences are very low for both groups: very close to 1.

Age

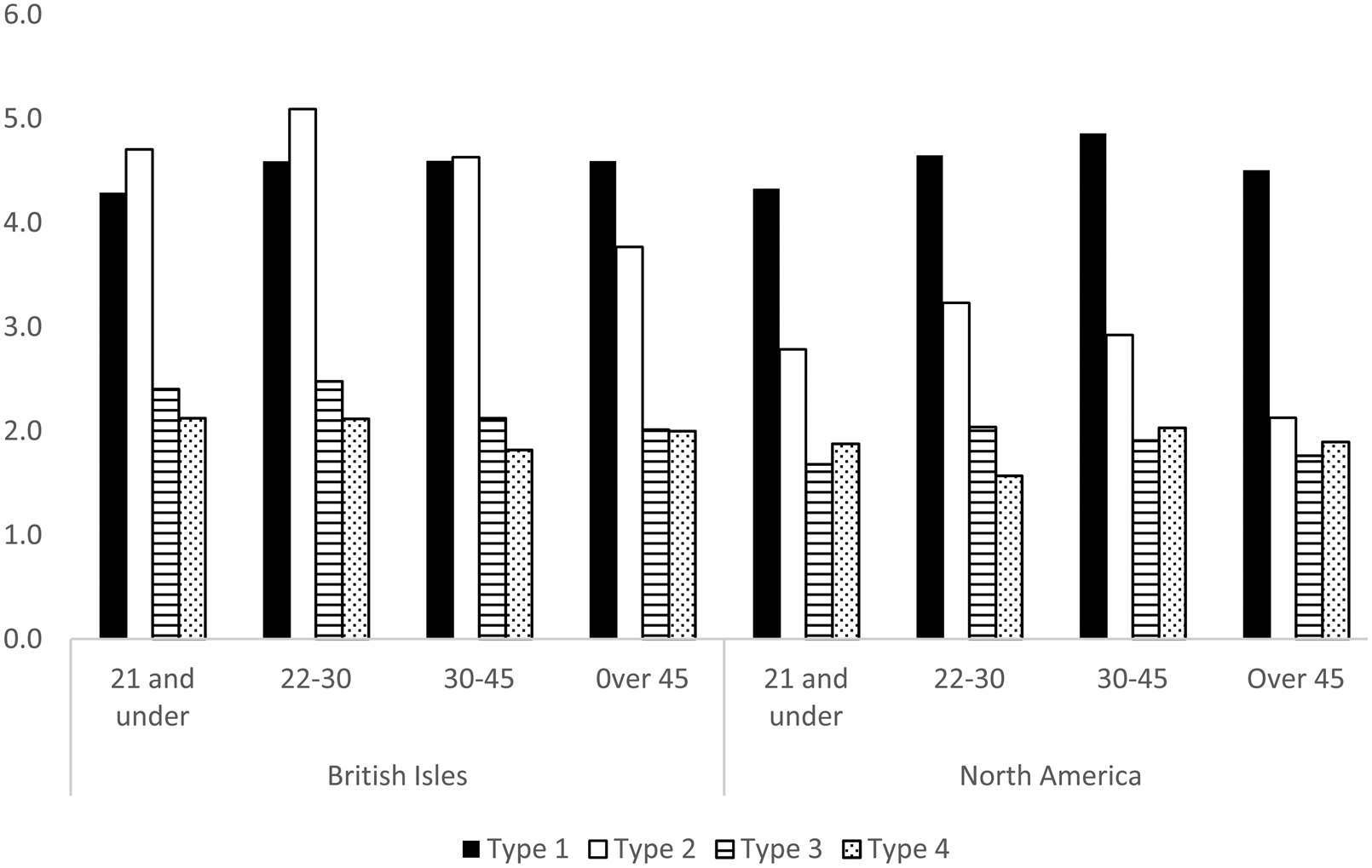

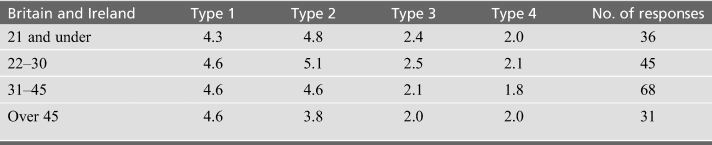

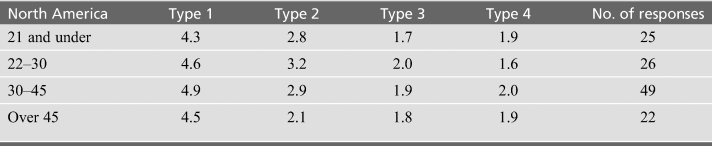

We present the results for Britain and Ireland and North America separately for age. In order to have some balance in numbers across the age groups we have a four-way split: respondents 21 and under, 22 to 30, 30 to 45, and over 45. The range in each category reflects the fact that we expected the responses to be more differentiated for the youngest generations. Tables 3 and 4 present the results for Britain and Ireland, and North America, respectively. Figure 5 presents them together.

Figure 5. Acceptability ratings for Britain and Ireland and North America by age

Table 3: Acceptability ratings for Britain and Ireland by age

Table 4: Acceptability ratings for North America by age

The ratings for Type 2 sentences are higher than Type 1 sentences for the three youngest groups from Britain and Ireland, although not significantly for the 30–45 year olds, whereas they are considerably lower for the over 45-year-olds in Britain and Ireland and all the North American age groups. This underlines that this is a relatively recent change in North America. For the oldest North American group, Type 2 sentences are rated only slightly better than Type 3 and 4 ones.

The ratings for Type 1 sentences only show minor differences across the age groups. Given that one of our initial questions was whether the younger North Americans had acquired the new form of cheeky, these results suggest that they have not fully acquired it yet, but may be in the process of doing so. Having presented the quantitative results of our survey, we turn now to the qualitative responses.

Qualitative observations

Many respondents had not heard the new meaning of cheeky at all. Those who said this were all non-Brits, corroborating the original internet meme. The traditional usage was seen as just that. A number of respondents said that it seemed old-fashioned, and older people were more likely to say that they would use it, but only for people (example 13).

(13) i have heard the word like twice from my grandparents before the cheeky british invasion oh my god

Conversely, many people especially from Britain and Ireland said that they use the new meaning and that one only, indicating that this meaning is becoming more common. Far more North Americans commented that they only used the old meaning of the form. Many of the North Americans who reported that they did use the new meaning made it clear they had spent time abroad or knew people from the UK or Australia, or that they had picked it up online because of the meme.

The new meaning is synonymous for our respondents with words like naughty and sneaky, and it is used for a ‘guilty pleasure’ or a ‘treat’. This sense was given in the responses of over 50% of the Britain and Ireland respondents, but only in two cases in the North American respondents, further indicating that the new meaning has not completely spread to North America yet.

We also received some comments about how the construction itself works. It cannot, one respondent notes, be combined with an adjective other than little: a cheeky little pint is fine, but a cheeky naughty pint is not. However, a cheeky sly half and a cheeky swift half both seem fine to the authors. It must, however, be in an indefinite DP: the cheeky [noun] simply cannot have any meaning other than the old one.

Interestingly, the phrase a cheeky pint seems to have become idiomatised to the point that the adjective can stand for the noun. A respondent provided the example a couple of cheekies after work.

Conclusion

The new usage of cheeky represents an additional meaning of ‘mildly illicit’, related to the original meaning ‘rude’. The new use of the word is distinct from the old one in its range of possible referents, namely certain activities, as opposed to the behaviour or character of certain humans. Because an inanimate noun simply cannot be ‘cheeky’, the adjective is necessarily interpreted as referring to the behaviour of the human involved in the act.

While the new cheeky brought the Britishness of the word to our attention, both old and new cheeky are British. The judgements and comments underline that both forms of cheeky are used and recognised in Britain and Ireland by most age groups, whereas in North America, the original meaning is seen as ‘very old-fashioned [to me], like something no one says anymore except maybe your grandma’ and the newer form is not understood by all. Despite this, the North American respondents are able for the most part to separate the sentences with the new cheeky from the expanded cheeky which we created, demonstrating that there is some awareness of the new form with the connotations of illicitness that characterise it in the UK.

Finally, our findings regarding cheeky and its new meaning illustrate the importance of social media for spreading linguistic change rapidly across communities. This change had been in progress in the UK for the last few decades, but the viral meme brought the new use to a wider group of speakers and brought the regional differences into the spotlight.

LAURA BAILEY is a Lecturer in English Language and Linguistics at the University of Kent. She is interested in the formal analysis of non-standard syntax and has most recently published work on preposition-dropping in varieties of English and other languages (Iberia 2019). Her research is parametric and cross-linguistic in nature. Previous publications include work on question particles and disjunction, and her other work on ‘internetese' includes an in-depth study of the syntax of the ‘because X’ phenomenon. Email: l.r.bailey@kent.ac.uk

LAURA BAILEY is a Lecturer in English Language and Linguistics at the University of Kent. She is interested in the formal analysis of non-standard syntax and has most recently published work on preposition-dropping in varieties of English and other languages (Iberia 2019). Her research is parametric and cross-linguistic in nature. Previous publications include work on question particles and disjunction, and her other work on ‘internetese' includes an in-depth study of the syntax of the ‘because X’ phenomenon. Email: l.r.bailey@kent.ac.uk

MERCEDES DURHAM is Reader in Sociolinguistics at Cardiff University. Her research is broadly concerned with how linguistic variation (and with it, language change) is acquired, transmitted and viewed by individual speakers and across successive generations. Her recent publications include Sociolinguistic Variation in Children's Language (with Jennifer Smith) (CUP 2019), The Acquisition of Sociolinguistic Competence in a Lingua Franca Context (Multilingual Matters 2014) and an edited volume Sociolinguistics in Wales (with Jonathan Morris) (Palgrave 2016). Email: DurhamM@cardiff.ac.uk

MERCEDES DURHAM is Reader in Sociolinguistics at Cardiff University. Her research is broadly concerned with how linguistic variation (and with it, language change) is acquired, transmitted and viewed by individual speakers and across successive generations. Her recent publications include Sociolinguistic Variation in Children's Language (with Jennifer Smith) (CUP 2019), The Acquisition of Sociolinguistic Competence in a Lingua Franca Context (Multilingual Matters 2014) and an edited volume Sociolinguistics in Wales (with Jonathan Morris) (Palgrave 2016). Email: DurhamM@cardiff.ac.uk