Introduction

English dialects demonstrate considerable variation in their pronominal systems (see for example Trudgill & Chambers, Reference Trudgill and Chambers1991 and Hernández, Reference Hernández, Hernández, Kolbe and Schultz2011). In England, pronouns in the north east of the country – the urban areas of Tyne and Wear and Teesside and the counties of Durham and Northumberland (hereafter NEE) – are often different from those found in Standard English (SE). The most extensive modern accounts of NEE pronouns are Beal (Reference Beal, J. and Milroy1993) and Beal, Burbano–Elizondo and Llamas (Reference Beal, Burbano–Elizondo and Llamas2012), but because they appear in chapters dealing with a wide range of morphosyntactic topics, the coverage is necessarily brief. This article is able to offer a more detailed overview of the morphology of NEE pronouns, based on a sizeable naturalistic corpus of vernacular writing.

The corpus is Ready to Go (RTG), an online forum for people with an interest in Sunderland A.F.C., a football club with a fanbase centred on a city on the North Sea littoral at the heart of the region. It is a written corpus, making it an unusual data-set in the study of regional non-standard morphosyntax. While ‘the research community is not exactly drowning’ in corpora that sample regional dialects (Szmrecsanyi & Anderwald, Reference Szmrecsanyi, Anderwald, Boberg, Nerbonne and Watt2018: 303), those that do exist consist mainly of orthographic transcriptions of interviews with informants. In some cases, such as the Diachronic Electronic Corpus of Tyneside English (DECTE), these interviews were carried out specifically for linguistic research; in others they have been co-opted for research after being recorded for other purposes (e.g. the Freiburg Corpus of English Dialects is mainly made up of local history interviews).

This focus on spoken rather than written language in corpus-based dialectology is unsurprising, given that audio recordings allow access to phonology, and also because the naturally occurring, spontaneous, unselfconscious, everyday speech of folk in their locally based communities has conventionally been seen as the ‘holy grail’ of the sociolinguistic enterprise (Holmes & Wilson, Reference Holmes and Wilson2017: 268). Certainly, there has been a bias against regarding writing as truly vernacular, because the acquisition of literacy has generally meant literacy in Standard English. In the UK at least, the Standard Language Ideology exerts its strongest influence at the level of morphosyntax, so when people write they typically use what they believe to be standard grammar. Should written text therefore be discounted as a source of non-standard forms? While in the past writing might have been constrained by proximity to the standard, in the era of Web 2.0 contemporary forms of writing online show ‘a relative lack of institutional regulation’ resulting in a proliferation of ‘spoken-like and vernacular features, traces of spontaneous production, innovative spelling choices’, and so on (Androutsopoulos, Reference Androutsopoulos and Coupland2010: 209). On the vernacular participatory web (Howard, Reference Howard2008; Androutsopoulos, Reference Androutsopoulos and Coupland2010) sites such as RTG are socio-pragmatically complex arenas of argument, anecdote, banter and debate, in which non-standard, regionally marked Englishes flourish. These are qualities which make them a valuable resource for social dialectologists (see Pearce, Reference Pearce2015). Indeed, in some respects the language of RTG is closer to the ideal object of sociolinguistic enquiry than is the language captured in speech-based corpora, because it has not been elicited for the purposes of research.

Another advantage of the corpus is its size. At approximately 12 million words (and growing) RTG is about 12 times bigger than DECTE, the closest comparable NEE corpus.Footnote 1 Size is important when morphosyntax is the research focus, since the larger the corpus, the more chance a particular form will occur. For example, yon is not found in DECTE, but appears 32 times in RTG. A description of NEE demonstratives based on DECTE would therefore have been incomplete. Size can also be measured in terms of the number of active individuals registered to use the site, which currently stands at over 12,000.

Using WebCorp Live to interrogate the RTG site, I began my exploration by searching for all non-standard pronouns attested in previous studies of the region's grammar (Beal Reference Beal, J. and Milroy1993, Reference Beal, Kortmann and Upton2008; Beal et al., Reference Beal, Burbano–Elizondo and Llamas2012). My findings show that there is perhaps more variation in NEE pronouns than has previously been acknowledged. For example, I provide evidence for the retention of second-person pronouns in th– (e.g. thou, thee, thyself) and reveal an extensive system of reflexives. Furthermore, possessive pronouns and determiners, demonstratives, interrogatives, and indefinite pronouns receive more attention than they have to date. My account also has a ‘historical’ dimension, in that it draws on earlier dialectological studies – the Survey of English Dialects (SED) from the mid-20th century, and the research carried out under the aegis of the English Dialect Society in the late 19th century (in particular R.O. Heslop's Northumberland Words) – to assess the extent of conservatism in the system, and also the areal distribution of these forms, distinguishing (where it is of interest) between ‘pan-northernisms’ (features which are recorded widely across northern varieties of English) and those with a more focused NEE saliency.

Personal pronouns

First-person subject

The RTG spellings <a>, <ah> and <aa> suggest pronunciations such as [ɑ] and [a] for I.

(1) a think Henry was unreal as well but a still think Aguero is the best (2019)

(2) Ah’m not unhappy about living in Australia (2013)

The feature has been enregistered in NEE since at least the nineteenth century, as this entry from Northumberland Words (Heslop, Reference Heslop1892: 2) indicates:

AA, AW, AH, I the pronoun of the first-person. This long, broad sound is a characteristic of the dialect of the Tyneside and of South Northumberland. In local works it is generally represented by the letters aw.

For most present-day English speakers in the UK, forms in a– have a distinctly Scottish character (see the entry for A as a personal pronoun in the Dictionary of the Scots Language). They probably arose when I [ɪ] (a development of OE ic) was lengthened under stress in Middle English, and later diphthongized – probably to [ɑɪ]. The second element was lost under lack of stress and a new form [ɑ] and later [ɑ:] arose. Forms in a– are recorded for Northumberland (Nb) and Durham (Du) in the SED, as well as in the other northern counties, the midlands and East Anglia (see Upton, Parry & Widdowson, Reference Upton, Parry and Widdowson1994: 486).

In the plural, SED records us functioning as equivalent of SE we in Nb and Du, and also quite widely across the dialects (ibid.). It is to be found (though rarely) in RTG.

(3) It is what it is and us cant change nowt (2019)

First-person object

A more common colloquial use of us is as the equivalent of Standard English (SE) me. SED records objective singular us across the whole of England (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Parry and Widdowson1994: 486). It usually appears in imperative constructions such as ‘give us a kiss’ (with the pragmatic function of softening the force of the request). This feature is common in RTG (the broader context of the examples makes it clear that us has singular reference).

(4) Someone hoy us a link (2016)

In NEE, however, singular us is used more widely, meaning that sentences such as the following can also be heard, as they can in Scotland (Miller, Reference Miller, Schneider, Burridge, Kortmann, Mesthrie and Upton2004: 49).

(5) Are yer gonna knack iz marra? (2019)

(6) some aunty bought ez it (2011)

Spellings with <–z> are used to reflect the widespread northern pronunciation of the pronoun, while <i–> and <e–> spellings probably represent the unstressed form. Evidence for the regional saliency of this feature can be found in the SED. For example, in response to a prompt designed to elicit the order of pronouns in given it me/me it (Orton & Halliday, Reference Orton and Halliday1963: 1070), 8 of the 9 Nb informants and 3 of the 6 Du informants rejected me and substituted us. The entry for us in Northumberland Words (Heslop, Reference Heslop1893: 758) suggests this distinctive usage has been around for a while:

US, used for me. ‘Wiv us’ – with me. ‘Tiv us’ – to me. ‘He gov us ne answer.’ Sometimes shortened, as, ‘What'll ye gi's?’.

OED only refers to non-imperative us in relation to its use by ‘a sovereign, ruler, or magnate’, but the Dictionary of the Scots Language (DSL) has colloquial examples spanning the mid-19th century to the present day.

Another distinctive first-person objective pronoun associated with NEE is we. Described by Beal et al. (2012: 53) as a limited form of pronoun-exchange, it is not recorded in SED, though it is attested for Nb in the English Dialect Dictionary, with the example used drawn from Northumberland Words: ‘WE, us. ‘Haw-way wi we.’ This is perhaps peculiar to Spittal and Tweedmouth’ (Heslop, Reference Heslop1893: 775). In RTG, objective we favours prepositional phrases, with spellings reflecting the unstressed form found in this position in speech.

(7) Don't know how I didn't know that story when he was with wuh (2018)

(8) they're way too smart for wah (2012)

Like non-imperative us, objective we is also found in Scotland (‘We pron.’ DSL, 2004).

Second-person subject and object

RTG also has a rich array of non-standard second-person pronouns. SED records ye as a singular second-person subjective and objective pronoun, realised as [ji:], [jɪ] and [jə] (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Parry and Widdowson1994: 486). In RTG <ye>, <yee> and <yer> are found (with <yee> and <yay> sometimes used to represent the emphatic/stressed pronunciation). Modern ye is derived from Old English ge, which was the subjective case of the second person plural pronoun. Ye with singular reference emerges in the Middle English period, used instead of thou originally as a marker of respect, deference or formality (OED). Ye develops an objective function in the later Middle English period. These examples show ye as singular subject (9) and object (10 and 11).

(9) Ye canna mak a savaloy out of an alsatian, man haway (2018)

(10) fuck ye Frank (2013)

(11) Is that yee on the phone like? (2017)

Like forms of I in a–, ye has a Scottish flavour, and is widely attested there (‘Ye pron., v.’ DSL, 2004).

Yous is also common in NEE. This analogically created innovatory plural probably originates in Irish English, and it is also found in Scotland and Merseyside (Beal et al., Reference Beal, Burbano–Elizondo and Llamas2012: 53–54). In RTG yous and yees like ye, function as both subject and object (note also the variant spellings in Table 1).

(12) Yous need to be careful (2019)

(13) Hope this shuts yous up (2019)

(14) Youse will survive, just (2014)

(15) Some of youse are ganning on like the mags (2014)

(16) If yees take offence to that you need to get a life you sad bastards (2014)

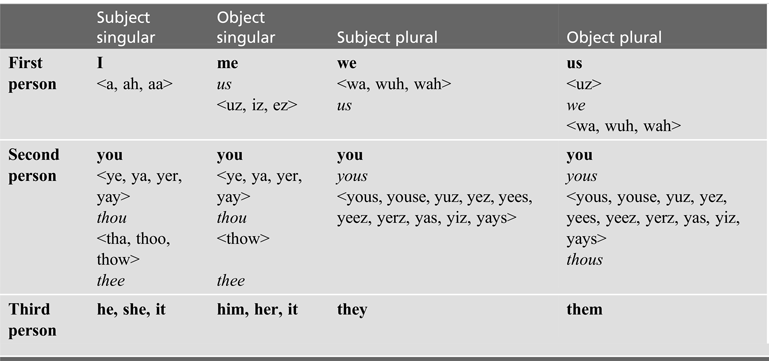

Table 1: Forms of personal pronouns in RTG

Standard forms in bold and more localized forms in italics

Selected orthographic representations from RTG are shown in angle brackets

Beal makes the important point that for ‘some younger speakers, yous has been generalised as the local form, and may be used to address one person’ (1993: 205), as in the following examples.

(17) It must be your little hands and beady eyes that give yous the edge like (2017)

(18) Love yous too marra (2019)

SED also records the older forms thou and thee as singular subjective and objective pronouns in NEE, with thou sometimes realised as [ðu:] or [ða] (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Parry and Widdowson1994: 486). Orthographic representations of these realisations occur in RTG. There are also examples of thou as a plural (25), which is possibly an innovation through analogy with yous.

(19) I shall have a pint with thee (2013)

(20) Does thoo not sleep Hank? (2018)

(21) thou's fukn crackers thou is (2018)

(22) You don't have to act like a scratter in a scratter shop thee nars (2014)

(23) ‘Tha's Got Hair Like a Ducks Arse’ (2011)

(24) I'd rather cut my tiddler off with a blunt comb than gan for a pint with thou (2015).

(25) I'll buy thous a gill (2012)

Historically, thee is the objective case of thou but this distinction is not maintained in the northern dialects where the pronoun is still used. Thee/thou in NEE is quite a rare phenomenon, and many instances in RTG involve contributors ‘impersonating’ people from further south in northern England, particularly from South Yorkshire, where it is an enregistered feature of the dialect (Cooper, Reference Cooper2019: 71). Since the SED was carried out, when forms in th– were widely distributed across England, at least amongst older, rural speakers (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Parry and Widdowson1994: 486), they have gone into steep decline. However, as the examples here show, there is enough evidence in RTG to suggest some contemporary currency in NEE, confirming that Burbano–Elizondo's informants who ‘argued that thou could be heard in Sunderland’ (Beal et al., Reference Beal, Burbano–Elizondo and Llamas2012: 54) were correct. In RTG it commonly occurs in the tag ‘thou knows’ (variously rendered orthographically to capture pronunciations such as [ða na:z] and [ði: na:z]).

(26) Has a turkish cap thee knas (2013)

(27) The NHS is creaking, tha knas (2016)

Heslop's remarks (1893: 727) are worth considering here:

THOO, thou; sometimes shortened to tu or ta. Thoo'll, thou wilt. Thoo's, thou art or thou shalt. Thoo is only used by intimates, or by a superior or senior to an inferior. Used in any other way it expresses the greatest possible contempt for the person addressed.

The pragmatics of 19th-century usage are echoed in the RTG data, especially in relation to the expression of social solidarity (examples 19, 20 and 25) and contempt (21 to 24).

Third-person

By and large, in both the subjective and objective, there is correspondence between SE and NEE third person forms, though pronoun exchange sometimes occurs when the subject element consists of a pronoun conjoined with a noun (this is common in many varieties of English).

(28) If him and his son want to come and watch as fans they're more than welcome (2018)

In the plural, them is recorded in the SED as a subject form in Du (and more widely) and also occurs in RTG.

(29) Them's the bastards that bombed me granny (2013)

We might also note the presence of ‘singular’ they, which is rapidly increasing in all varieties of English (see for example Paterson, Reference Paterson2014).

(30) Anyone who says they don't care is a joke of a fan in my opinion (2017)

Possessive determiners and pronouns

As with personal pronouns, contrasts with SE are confined mainly to the first- and second-persons of possessive determiners and pronouns (see Table 2).

Table 2: Possessive determiners and pronouns in RTG

Standard forms in bold and more localized forms in italics

Selected orthographic representations from RTG are shown in angle brackets

First person possessive determiners

Me is used widely in non-standard varieties where SE has my. In RTG, the spellings <mi> and sometimes <mee> occur, reflecting a vowel in the region of [ɪː].

(31) Me car's broke (2015)

(32) I'm just about to have mi tea (2019)

(33) Too right i want caviar on mee cheesy chips anarl! (2019)

In addition, we find the spelling <ma(h)>, reflecting a lower, backer vowel of the sort which has been attested in northern varieties of English since at least the 17th century (OED), but like a and ye is particularly associated with Scotland (McColl Millar, Reference McColl Millar2007).

(34) Ma Mam and Dad still live in Hendon (2014)

Of more local salience to NEE – though it is also found in Scottish varieties (‘Our possess. pron.’ DSL. 2004) – is the plural possessive determiner wor. In the SED wor is attested for Nb and Du, but it was also recorded across the northern counties and as far south as Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire as [wəʁ~wər~wəɹ] (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Parry and Widdowson1994: 488). Due to decline in rhoticity this is now often [wə] in speech, reflected in spellings such as <wa> in RTG.

(35) Ya have to understand wor pride and passion (2013)

(36) Only we could drop wa best player for a must win game (2019)

(37) I am getting wor lass to drop us off afterwards (2019)

In parallel with us, wor is sometimes used with singular reference. Example (37) shows a common pattern in NEE, where there is ‘a tendency for the first-person plural form to be used with reference to family members and sexual partners’ (Beal et al., Reference Beal, Burbano–Elizondo and Llamas2012: 53).

The OED records forms in w– emerging in the sixteenth century in Scotland, and labels them as ‘northern’ by the nineteenth century. Wor has long had a particular cultural salience in NEE, as its repetition in this couplet from a patriotic Northumberland song indicates: ‘In defence o’ wor country, wor laws, an’ wor King, / May a Peercy still lead us to battle’ (1824). Its use as a badge of north east identity (particularly on Tyneside) is evident in its appearance on signs and artefacts in the ‘linguistic landscape’ (see Pearce, Reference Pearce, Beal and Hancil2017), as is its occurrence in national media contexts in conjunction with north east celebrities: ‘Why-aye that was reall-aye beautiful!’ weeps Wor Cheryl (Shelley, Reference Shelley2014).

Second-person possessive determiners

These usually coincide with standard your (sometimes spelled <yer> or <ya>). There are also rarer forms in [ð–] corresponding to the personal pronouns thou/thee, with thy [ðɪ~ðə] attested for Nb and Du in SED.

(38) Should have known thy ears would prick up! (2013)

(39) And wharrabout thy hair? (2014)

(40) Ad thee oss. Get thee pipe (2018)

(41) Mek thoos mind up lad (2018)

Possessive pronouns

While possessive determiners feature in Beal (Reference Beal, J. and Milroy1993) and Beal et al. (Reference Beal, Burbano–Elizondo and Llamas2012), possessive pronouns do not. Has some interesting variability therefore been overlooked? In the first-person singular, there is general correspondence with Standard English in RTG (i.e. mine), but in the plural we do see forms in [w–], cognate with wor as a possessive determiner.

(42) Got wors at Costco mate (2011)

(43) wors came today (2019)

Wors is recorded in SED for Nb and Du (Orton & Halliday, Reference Orton and Halliday1963: 1072–73). It seems that wors, like yous is a relatively late addition to the pronoun system. Heslop's earliest citation is from a song published in 1819, in which London is compared unfavourably with Newcastle. Indeed, despite the rumours, its streets turn out to be just ‘like wors – brave and blashy!’ (1893: 797).

Non-standard second-person singular forms are rare in RTG, though thine is to be found (and was recorded for Nb and Du in the SED).

(44) I wonder whee's shitty arse the wife there'll have to see to first, the bairn's or thine! (2014)

(45) With an avatar like that, I'd fuckin’ dread to see thine! (2014)

Reflexive pronouns

Beal notes that ‘in standard English, reflexives are formed by adding self/selves to the possessive forms of the first and second person pronouns, but to the objective form of the third person pronouns. Tyneside English is more consistent in this respect, adding self/selves to the possessive form in every case’ (1993: 206). This results in non-standard patterns exemplified in RTG.

(46) he didn't even do it by hisself (2012)

(47) County Durham Mags should be ashamed of theirselves (2012)

This ‘levelling’ is widespread in non-standard English. However, the full picture of reflexives in NEE also includes variability in the reflexive suffix (Buchstaller & Corrigan, Reference Buchstaller, Corrigan and Hickey2015: 87). Table 3 reveals the presence of –sel(s) and sen(s) alongside –self(ves) in RTG.

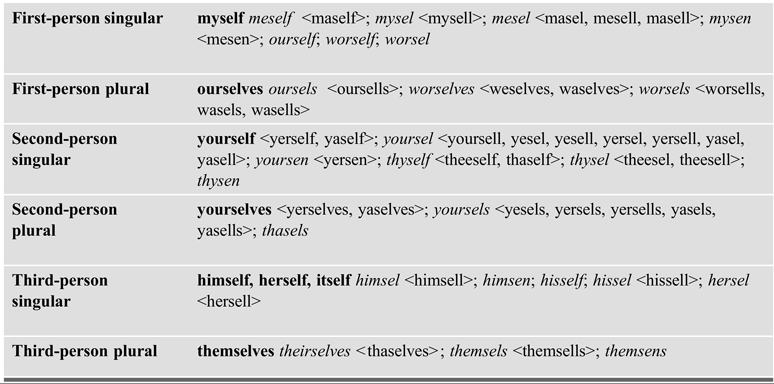

Table 3: Reflexive pronouns in RTG

Standard forms in bold and more localized forms in italics

Selected orthographic representations from RTG are also shown in angle brackets

The –self(ves) element is OE. It seems that –sel(s) emerged in the sixteenth century as a consequence of consonant cluster simplification, while –sen(s) perhaps reflects a development of a plural form in –n (as in eME sellfenn) and is recognized as dialectal by the 18th century. In SED the –sel form has wide distribution across the northern counties, the midlands and beyond, particularly in the first-person singular (i.e. mysel). It is also very common in colloquial Scottish English (‘Mysel pron.’ DSL, 2004). Forms in –sen are rarer with a narrower distribution focused on Yorkshire – where it is an enregistered feature (Cooper Reference Cooper2019) – and Lancashire, but they are also to be found in the East and West Midlands (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Parry and Widdowson1994: 488–489). Both –sel and –sen are identified as ‘pan-northernisms’ by Ruano–García, Sanchez–García and García–Bermejo Giner (Reference Ruano–García, Sanchez–García, García–Bermejo Giner and Hickey2015: 145).

In addition, the use of first-person w– and second–person th– forms (comparable to the related simplex pronouns) is notable.

First-person reflexives

SED records –sel for Nb and Du and –sen in other northern locations. Both are to be found in RTG, alongside the much more widespread colloquial form meself.

(48) I'm ashamed of meself! (2019)

(49) I got mysel a glass of sauvignon blanc at halftime yesterday (2011)

(50) I've landed mesel in a bit bother with all this (2019)

(51) I shat mysen (2014)

(52) Was just going to make mesen a Tuna salad baguette (2014)

Plural w– forms are common in Nb and Du. In the Basic Materials, [wəsɛlz] is recorded for Northumberland.

(53) We dust worselves down (2018)

(54) Wa dust worsels down (2019)

(55) We were shitting waselves (2019)

(56) We'll have to work it out for wasels i reckon (2010)

We also note the more standard form our combining with non-standard –sels.

(57) Aye, we don't want to give oursels too long to hang on like (2019)

Morphologically singular forms also occur, mainly with plural reference.

(58) If we compare ourself to league one clubs we'll stay as a league one club (2019)

Second-person reflexives

There is more variation in the second person in RTG than was found in SED, which only records thysel and yoursel(s) for Nb and Du (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Parry and Widdowson1994: 488–489). The following singular forms illustrate this variety:

(59) So gan fist thyself reet in ones rear orifice (2015)

(60) Gan fist thysel Warwick (2014)

(61) How's it gannin theeself? (2015)

(62) Get theesel down to the computer shop (2011)

(63) Whey behave thysen this time round Joe (2018)

(64) Don't be too hard on yoursel (2013)

(65) Get yesel on the train like man (2013)

(66) get yoursen down the match (2013)

Plural forms also occur.

(67) enjoy yoursels while i"m away you intelligent fuckers (2013)

(68) Perhaps decide between yesels? (2015)

Third-person reflexives

Hissel(l,f) and hersel(l) are recorded for Nb and Du in SED and both are found in RTG. In addition, we find forms in –en.

(69) he's shot hisself (2012)

(70) would anyone really be that bothered if he mangled himsel in his ferrari the morra (2014)

(71) Tell him to get hissel over to Roker and sort it out (2018)

(72) Carol has just bought hersel a new house (2010)

(73) unsurprisingly he drank himsen to death (2017)

In the plural, theirsels is recorded for Nb and Du in SED, but other variants also occur in RTG.

(74) how do the symptoms manifest theirsels there mate? (2017)

(75) Smoggy bastards don't like people enjoying themsels (2013)

(76) Baresi and Donadoni who had about 130 Italian caps in their career by theirselves (2015)

(77) they've really gone the full Guzman and all got themsens bulletproof Audis now (2019)

(78) They would just piss thasels (2017)

(79) They can't help thaselves (2014)

Spellings in tha– probably reflect a reduced their; [ðəsɛlz] was a pronunciation recorded in the SED for Nb and Du (Orton & Halliday, Reference Orton and Halliday1963: 1097).

We also see singular uses of these forms.

(80) Whoever that was needs to take a long hard look at theirself (2018)

(81) So you are seriously commending a person for drinking themself to death? (2017)

Demonstrative pronouns and determiners

Generally, in contemporary NEE, the demonstratives used to mark whether something is near or distant from the speaker (in Cartesian or social space) correspond to SE (e.g. this/that, these/those). However, in RTG we occasionally find the distals thon and yon, both of which were recorded in the SED for Nb and Du and also widely across the northern counties (Orton & Halliday, Reference Orton and Halliday1963: 1089).

(82) Thon shite player Maja (2018)

(83) You cool fuckers in yon end wouldn't be able to hear (2019)

Heslop records pronominal uses of thon and yon e.g. ‘Whe's thon?’ (1893: 727), but in RTG thon only occurs as a determiner, as in the examples. Etymologically, thon seems to be a comparatively recent alteration of yon, the initial consonant being assimilated to this and that (OED). Yon and thon (used interchangeably as they are in RTG) are also features of Scots dialects (McColl Millar, Reference McColl Millar2007: 69).

Indefinite pronouns

NEE contrasts with SE mainly in relation to negative indefinite pronouns, because no as a quantifier is often pronounced [ni:], [ne:] or [neɪ] in NEE.

(84) Neebody is going to own up (2019)

(85) Hope nee one ever does a countdown to your redundancy then (2019)

(86) Well ney one can accuse you of sitting on the fence (2017)

(87) Neen o’ this turkey shite for me (2017)

Nee has a long northern history. For example, it occurs in Cursor Mundi, a poem probably written by a Northumbrian in c. 1300 (‘nee pride o pane’). Neen (none) appears in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (c. 1390): ‘By goddes sale, it sal neen other bee’. The Chaucerian example is from the Reeve's Tale. It is a line given to Aleyn, a student at Cambridge University who is from North East England.

It is also worth noting formulations such as the following which combine nee with an expressive noun. Occasionally the elements are orthographically conjoined, pointing towards grammaticalization.

(88) Nee fucker gives a fuck about Bradford either so bog off (2020)

(89) Nee cunt in my family looks like steve agnew marra :lol: (2012)

(90) Nee bugger else is allowed in (2019)

(91) neebugger believes it surely? (2019)

We also find the well known ‘pan-northernisms’ nowt and owt (with owt also occurring as the equivalent of SE –thing in conjunction with some–).

(92) Nowt happening (2019)

(93) Owt confirmed? (2017)

(94) Aren't you from Whitley bay or summat? (2020)

Like thou and –sen, these indefinites are strongly associated with Yorkshire dialect (Cooper Reference Cooper2019), though SED also records them for locations in the East and West Midlands, as well as all six northern counties (Orton & Halliday, Reference Orton and Halliday1963: 861–63; Orton & Barry, Reference Orton and Barry1971: 844–46; Orton & Tilling, Reference Orton and Tilling1971: 1047–49)

In addition, the pronoun which in SE is one sometimes occurs as a y– form in RTG.

(95) Layers and layers for this yin (2012)

(96) proper insult that yin (2019)

Forms of one in y– are northern English regional and Scots, dating from the seventeenth century, reflecting the development of a front glide before certain vowels (see the entry for yin in DSL, 2004).

Interrogative pronouns

SED elicits who and whose, providing transcriptions for Nb and Du which suggest pronunciations such as [hwi:] and [wi:] (Orton & Halliday Reference Orton and Halliday1963: 1078). In RTG, these pronunciations are rendered orthographically as <hwee, w(h)ee, hwee(s,z) and w(h)ee(s,z)>.

(97) Whee's this bloke then? (2017)

(98) whee can afford eight kids like (2013)

(99) weez daft fault was that though? (2013)

(100) ‘Weez keys are these keys’ (2013)

Whee is well established in nineteenth-century sources and has an entry in NW (Heslop, Reference Heslop1893: 780).

Discussion and conclusion

By examining the non-standard pronouns in RTG through the lens of earlier dialectological studies, I have shown their considerable pedigree in northern varieties of English, with distributions reflecting the external history of the region (Beal, Reference Beal, Kortmann and Upton2008: 373). Some have been recorded in both southern Scotland and across the northern counties of England, revealing the significance of a ‘greater Northumbria’, stretching back to the Anglo-Saxon period and persisting into the present-day (e.g. I as [ɑ ~ a]; singular non-imperative us; cluster simplification in –self; forms of one in y–). Some also reflect the commonalities that parts of NEE have with the ‘Scandinavian Belt’ – the Norse-influenced territories further south (e.g. pronominal forms in th– and the reflexive suffix –sen). And some, if not unique to NEE, have a particular cultural salience there, such as wor and yous.

Evidence from RTG might be used, therefore, to support claims that in the North East – a peripheral region suffering from social and political marginalization (Pearce 2009) – the forces of linguistic conservatism are stronger than in other parts of England. But caution is needed. While the RTG corpus is undoubtedly large, it is not necessarily ‘representative’ of the broader population. The dispositions, structures of feeling, schemes of thought, tastes, preferences and values revealed on the site (the ‘habitus’ in Bourdieusian terms) is working-class and masculinist, and most contributors seem to be in their thirties, forties and fifties with strong local affiliations and network ties. What is potentially missing from the picture are the very people often identified as the vanguard of dialect levelling in the region: the young, women, the middle classes (see for example Watt, Reference Watt2002). RTG is perhaps fertile ground for a type of linguistic conservatism that might not fully reflect the English of the wider North East.

Nevertheless, what RTG lacks in representativeness, it makes up for in socio-pragmatic diversity. In the charged rhetorical performances that are a feature of the site, items that might well be ‘recessive’ in the wider context can function as identity markers or be used for particular stylistic effects (Robinson, Reference Robinson and Hickey2016: 29). We see how pronouns – along with other lexical, orthographic and morphosyntactic features – can be deployed in cultural performances in which the voices of others are adopted and characters are brought to life. Often these performances are nostalgic and affectionate, but sometimes they caricature the social and cultural ‘other’, as in these examples in which people from Sunderland ‘voice’ people from Tyneside.Footnote 2

(101) started a job once working with 2 lasses one from magland the other from Jarrow, about 12 o'clock they got up from their desks announced ‘Wagoingforwadinnaz’ I honestly could not understand what they had just said (2014)

(102) Played indoor footy in the Sunderland Leisure centre years ago against some lads from Boldon, when leading them 6–nowt one of them said; ‘Wa hafta play for wor pride noo lads’ (2014)

(103) But ivverybody loves wuh man! (2014)

The creation of such performances reveals an implicit understanding of and receptivity towards variation. But sometimes metalinguistic knowledge is explicitly expressed, even in relation to features as generally ‘unmarked’ as pronouns.

(104) Hordenites say chor for variation as well as thee, thou, thyne etc haha (2017)

(105) Marra is more a word used by us yackers than by townies. Like ‘thou’ or ‘the’ for ‘you’ and so on, all yackerisms (2014)

(106) my mates from Pennywell use ‘us’ instead of ‘we’ (2019)

(107) how well do you think Wally will be able to pronounce ‘wu dust waselves down’ (2014)

But such performativity and receptivity should not distract us from the fact that the NEE pronouns presented here are typically deployed in a far less ‘knowing’ and deliberative manner, often appearing as the ‘natural’, ‘unmarked’ choice of the contributor, pointing to the preservation and wider usage of these venerable forms in the speech community beyond the participatory vernacular web.

MICHAEL PEARCE is a Senior Lecturer in English language at the University of Sunderland. Before moving to North East England, he was a lecturer in the School of English at the University of Leeds. His work on the language and culture of Northumbria has been published in journals such as English Studies and Journal of English Linguistics, as well as English Today. Email: mike.pearce@sunderland.ac.uk

MICHAEL PEARCE is a Senior Lecturer in English language at the University of Sunderland. Before moving to North East England, he was a lecturer in the School of English at the University of Leeds. His work on the language and culture of Northumbria has been published in journals such as English Studies and Journal of English Linguistics, as well as English Today. Email: mike.pearce@sunderland.ac.uk