1 Introduction

Self-similar measures in

![]() ${\mathbb {R}}$

are perhaps the simplest examples of measures which exhibit complex local structure. These measures are associated with finite sets of similarity maps in

${\mathbb {R}}$

are perhaps the simplest examples of measures which exhibit complex local structure. These measures are associated with finite sets of similarity maps in

![]() ${\mathbb {R}}$

. To be precise, by an iterated function system of similarities (IFS), we mean a finite set of maps

${\mathbb {R}}$

. To be precise, by an iterated function system of similarities (IFS), we mean a finite set of maps

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

where each

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

where each

![]() $S_{i}(x)=r_{i} x+d_{i}$

and

$S_{i}(x)=r_{i} x+d_{i}$

and

![]() $0<|r_{i}|<1$

. The attractor, or self-similar set, of this system is the unique compact set K satisfying

$0<|r_{i}|<1$

. The attractor, or self-similar set, of this system is the unique compact set K satisfying

![]() $\bigcup _{i\in \mathcal {I}}S_{i}(K)=K$

. Given a probability vector

$\bigcup _{i\in \mathcal {I}}S_{i}(K)=K$

. Given a probability vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {p}=(p_{i})_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

where each

$\boldsymbol {p}=(p_{i})_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

where each

![]() $p_{i}>0$

and

$p_{i}>0$

and

![]() $\sum _{i} p_{i}=1$

, the associated self-similar measure is the unique Borel probability measure satisfying

$\sum _{i} p_{i}=1$

, the associated self-similar measure is the unique Borel probability measure satisfying

$$ \begin{align*} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(E)=\sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}}p_{i}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}\circ S_{i}^{-1}(E) \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(E)=\sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}}p_{i}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}\circ S_{i}^{-1}(E) \end{align*} $$

for any Borel set

![]() $E\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}$

. For a more through discussion of the background and basic properties of self-similar sets and measures, we refer the reader to Falconer’s book [Reference Falconer6].

$E\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}$

. For a more through discussion of the background and basic properties of self-similar sets and measures, we refer the reader to Falconer’s book [Reference Falconer6].

To understand the general structure of the measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

or the self-similar set K, one often considers basic dimensional quantities such as the Hausdorff dimension

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

or the self-similar set K, one often considers basic dimensional quantities such as the Hausdorff dimension

![]() $\operatorname {dim}_{\mathrm {H}} K$

and analogous statements for measures, or other notions of dimension. Computing these values can be highly non-trivial for general iterated function systems of similarities and there is significant literature on this matter (see, for example, [Reference Bandt and Graf2, Reference Feng and Hu12, Reference Fraser, Henderson, Olson and Robinson16, Reference Hochman23, Reference Jordan and Rapaport26, Reference Lau and Ngai29, Reference Ngai and Wang32, Reference Schief36]). In this paper, we focus on a more fine-grained notion of dimension known as the local dimension. Given a point

$\operatorname {dim}_{\mathrm {H}} K$

and analogous statements for measures, or other notions of dimension. Computing these values can be highly non-trivial for general iterated function systems of similarities and there is significant literature on this matter (see, for example, [Reference Bandt and Graf2, Reference Feng and Hu12, Reference Fraser, Henderson, Olson and Robinson16, Reference Hochman23, Reference Jordan and Rapaport26, Reference Lau and Ngai29, Reference Ngai and Wang32, Reference Schief36]). In this paper, we focus on a more fine-grained notion of dimension known as the local dimension. Given a point

![]() $x\in K=\operatorname {\mathrm {supp}}{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

, the local dimension is given by

$x\in K=\operatorname {\mathrm {supp}}{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

, the local dimension is given by

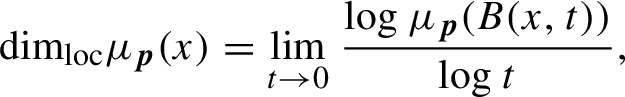

$$ \begin{align*} {\dim_{\operatorname{\mathrm{loc}}}}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(x)=\lim_{t\to 0}\frac{\log {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(B(x,t))}{\log t}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} {\dim_{\operatorname{\mathrm{loc}}}}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(x)=\lim_{t\to 0}\frac{\log {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(B(x,t))}{\log t}, \end{align*} $$

when the limit exists. From the perspective of multifractal analysis, one is interested in determining geometric properties of the sets

![]() $K(\alpha ):= \{x\in K:{\dim _{\operatorname {\mathrm {loc}}}}{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(x)=\alpha \}$

. However, the

$K(\alpha ):= \{x\in K:{\dim _{\operatorname {\mathrm {loc}}}}{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(x)=\alpha \}$

. However, the

![]() $L^{q}$

-spectrum of

$L^{q}$

-spectrum of

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

is given by

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

is given by

$$ \begin{align*} \tau({\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}},q)=\tau(q):= \liminf_{t\to 0}\frac{\log \sup\sum_{i}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(B(x_{i},t))^{q}}{\log t} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \tau({\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}},q)=\tau(q):= \liminf_{t\to 0}\frac{\log \sup\sum_{i}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(B(x_{i},t))^{q}}{\log t} \end{align*} $$

for each

![]() $q\in {\mathbb {R}}$

, where the supremum is over disjoint families of closed balls with centres

$q\in {\mathbb {R}}$

, where the supremum is over disjoint families of closed balls with centres

![]() $x_{i}\in K$

.

$x_{i}\in K$

.

An important objective of multifractal analysis is to understand the relationship between the

![]() $L^{q}$

-spectrum of the measure

$L^{q}$

-spectrum of the measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

and the dimension spectrum

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

and the dimension spectrum

![]() $\operatorname {dim}_{\mathrm {H}} K(\alpha )$

. A heuristic relationship between

$\operatorname {dim}_{\mathrm {H}} K(\alpha )$

. A heuristic relationship between

![]() $\tau (q)$

and

$\tau (q)$

and

![]() $\operatorname {dim}_{\mathrm {H}} K(\alpha )$

, known as the multifractal formalism, was introduced by Halsey et al. [Reference Halsey, Jensen, Kadanoff, Procaccia and Shraiman17]. The multifractal formalism states, roughly speaking, that the dimension spectrum can be computed as the concave conjugate of

$\operatorname {dim}_{\mathrm {H}} K(\alpha )$

, known as the multifractal formalism, was introduced by Halsey et al. [Reference Halsey, Jensen, Kadanoff, Procaccia and Shraiman17]. The multifractal formalism states, roughly speaking, that the dimension spectrum can be computed as the concave conjugate of

![]() $\tau (q)$

, that is,

$\tau (q)$

, that is,

$$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{dim}_{\mathrm{H}} K(\alpha) =\tau^{*}(\alpha):= \inf_{q\in{\mathbb{R}}}\{q\alpha-\tau(q)\} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{dim}_{\mathrm{H}} K(\alpha) =\tau^{*}(\alpha):= \inf_{q\in{\mathbb{R}}}\{q\alpha-\tau(q)\} \end{align*} $$

for any

![]() $\alpha $

in the domain of

$\alpha $

in the domain of

![]() $\tau ^{*}(\alpha )$

; see Definition 4.2 for a complete definition in our setting. This concave conjugate relationship has been studied by many authors (see, for example, [Reference Cawley and Mauldin3, Reference Feng7, Reference Feng10, Reference Feng and Lau13, Reference Feng, Lau and Wang14, Reference Halsey, Jensen, Kadanoff, Procaccia and Shraiman17, Reference Lau, Bandt, Graf and Zähle27, Reference Lau and Ngai28, Reference Patzschke33, Reference Pesin and Weiss34, Reference Shmerkin38]). As a particularly elegant example, it has been verified in general for iterated function systems satisfying the strong separation condition (

$\tau ^{*}(\alpha )$

; see Definition 4.2 for a complete definition in our setting. This concave conjugate relationship has been studied by many authors (see, for example, [Reference Cawley and Mauldin3, Reference Feng7, Reference Feng10, Reference Feng and Lau13, Reference Feng, Lau and Wang14, Reference Halsey, Jensen, Kadanoff, Procaccia and Shraiman17, Reference Lau, Bandt, Graf and Zähle27, Reference Lau and Ngai28, Reference Patzschke33, Reference Pesin and Weiss34, Reference Shmerkin38]). As a particularly elegant example, it has been verified in general for iterated function systems satisfying the strong separation condition (

![]() $S_{i}(K)\cap S_{j}(K)\neq \emptyset $

if and only if

$S_{i}(K)\cap S_{j}(K)\neq \emptyset $

if and only if

![]() $i=j$

) [Reference Cawley and Mauldin3]. This separation requirement has been relaxed to the open set condition [Reference Hutchinson25] and the concave conjugate relationship has been verified [Reference Arbeiter and Patzschke1, Reference Patzschke33, Reference Pesin and Weiss34]. In both cases,

$i=j$

) [Reference Cawley and Mauldin3]. This separation requirement has been relaxed to the open set condition [Reference Hutchinson25] and the concave conjugate relationship has been verified [Reference Arbeiter and Patzschke1, Reference Patzschke33, Reference Pesin and Weiss34]. In both cases,

![]() $\tau (q)$

is differentiable for all

$\tau (q)$

is differentiable for all

![]() $q\in {\mathbb {R}}$

and is determined uniquely by the implicit formula

$q\in {\mathbb {R}}$

and is determined uniquely by the implicit formula

$\sum _{i\in \mathcal {I}}p_{i}^{q} r_{i}^{-\tau (q)}=1$

.

$\sum _{i\in \mathcal {I}}p_{i}^{q} r_{i}^{-\tau (q)}=1$

.

However, when the open set condition fails, outside specialized analysis of some families of examples (for example, Bernoulli convolutions associated with the unique positive root of the polynomial

![]() $x^{k}-x^{k-1}-\cdots -x-1$

[Reference Feng9]), there has been much less progress on verifying the multifractal formalism at all

$x^{k}-x^{k-1}-\cdots -x-1$

[Reference Feng9]), there has been much less progress on verifying the multifractal formalism at all

![]() $q\in {\mathbb {R}}$

. For

$q\in {\mathbb {R}}$

. For

![]() $q\geq 0$

, the function

$q\geq 0$

, the function

![]() $x\mapsto x^{q}$

is non-decreasing so the summation in the definition of

$x\mapsto x^{q}$

is non-decreasing so the summation in the definition of

![]() $\tau (q)$

is dominated by closed balls with large measure. However, for

$\tau (q)$

is dominated by closed balls with large measure. However, for

![]() $q<0$

, the summation is dominated by closed balls of small measure. Generally speaking, understanding the multifractal analysis of measures when

$q<0$

, the summation is dominated by closed balls of small measure. Generally speaking, understanding the multifractal analysis of measures when

![]() $q<0$

is substantially more challenging than the case

$q<0$

is substantially more challenging than the case

![]() $q\geq 0$

. Gaining more information about this case is our focus in this document.

$q\geq 0$

. Gaining more information about this case is our focus in this document.

1.1 The weak separation condition

Notably, neither the strong separation condition nor the open set condition allows for the existence of exact overlaps. We introduce some notation: let

![]() $\mathcal {I}^{*}$

denote the set of all finite words on

$\mathcal {I}^{*}$

denote the set of all finite words on

![]() $\mathcal {I}$

. For

$\mathcal {I}$

. For

![]() $\sigma =(i_{1},\ldots ,i_{n})\in \mathcal {I}^{*}$

, write

$\sigma =(i_{1},\ldots ,i_{n})\in \mathcal {I}^{*}$

, write

![]() $S_{\sigma }=S_{i_{1}}\circ \cdots \circ S_{i_{n}}$

,

$S_{\sigma }=S_{i_{1}}\circ \cdots \circ S_{i_{n}}$

,

![]() $r_{\sigma }=r_{i_{1}}\cdots r_{i_{n}}$

and, if

$r_{\sigma }=r_{i_{1}}\cdots r_{i_{n}}$

and, if

![]() $n\geq 1$

,

$n\geq 1$

,

![]() $\sigma ^{-}=(i_{1},\ldots ,i_{n-1})$

. By exact overlaps, we mean the existence of words

$\sigma ^{-}=(i_{1},\ldots ,i_{n-1})$

. By exact overlaps, we mean the existence of words

![]() $\sigma \neq \tau \in \mathcal {I}^{*}$

such that

$\sigma \neq \tau \in \mathcal {I}^{*}$

such that

![]() $S_{\sigma }=S_{\tau }$

. To study examples allowing exact overlaps while still maintaining separation of non-overlapping words, Lau and Ngai introduced the weak separation condition and studied basic conditions under which the multifractal formalism holds [Reference Lau and Ngai28]. For any

$S_{\sigma }=S_{\tau }$

. To study examples allowing exact overlaps while still maintaining separation of non-overlapping words, Lau and Ngai introduced the weak separation condition and studied basic conditions under which the multifractal formalism holds [Reference Lau and Ngai28]. For any

![]() $t>0$

and Borel set

$t>0$

and Borel set

![]() $E\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}$

, define

$E\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}$

, define

Then the weak separation condition is equivalent to requiring that

$$ \begin{align} \sup_{x\in{\mathbb{R}},t>0}\#\{S_{\sigma}:\sigma\in\Lambda_{t}(U(x,t))\}<\infty, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \sup_{x\in{\mathbb{R}},t>0}\#\{S_{\sigma}:\sigma\in\Lambda_{t}(U(x,t))\}<\infty, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\# X$

denotes the cardinality of a set X and

$\# X$

denotes the cardinality of a set X and

![]() $U(x,t)$

is the open ball about x with radius t. Note that the definition only considers functions

$U(x,t)$

is the open ball about x with radius t. Note that the definition only considers functions

![]() $S_{\sigma }$

rather than the words

$S_{\sigma }$

rather than the words

![]() $\sigma $

so as to allow exact overlaps. To see an equivalent formulation with respect to exact overlaps or the equivalence with the original definition of Lau and Ngai, see [Reference Zerner40, Theorem 1].

$\sigma $

so as to allow exact overlaps. To see an equivalent formulation with respect to exact overlaps or the equivalence with the original definition of Lau and Ngai, see [Reference Zerner40, Theorem 1].

Under the weak separation condition, verification of the multifractal formalism is subtle. One of the earliest examples of exceptional behaviour is with respect to self-similar measures of the system of Bernoulli convolutions

![]() $\{x\mapsto \rho x,x\mapsto \rho x+(1-\rho )\}$

, where the contraction ratio

$\{x\mapsto \rho x,x\mapsto \rho x+(1-\rho )\}$

, where the contraction ratio

![]() $\rho $

is the reciprocal of the golden mean. In this case, the

$\rho $

is the reciprocal of the golden mean. In this case, the

![]() $L^{q}$

-spectrum

$L^{q}$

-spectrum

![]() $\tau (q)$

has a phase transition, or a point where

$\tau (q)$

has a phase transition, or a point where

![]() $\tau (q)$

is not differentiable. Nevertheless, the multifractal formalism still holds and

$\tau (q)$

is not differentiable. Nevertheless, the multifractal formalism still holds and

![]() $\tau (q)$

is analytic for other values of q [Reference Feng9]. Another example of exceptional behaviour is the

$\tau (q)$

is analytic for other values of q [Reference Feng9]. Another example of exceptional behaviour is the

![]() $3$

-fold convolution of the uniform Cantor measure. In this case, it was observed that the set of attainable local dimensions is not an interval and the multifractal formalism fails [Reference Hu and Lau24]. The problem here is, in some sense, that the measure

$3$

-fold convolution of the uniform Cantor measure. In this case, it was observed that the set of attainable local dimensions is not an interval and the multifractal formalism fails [Reference Hu and Lau24]. The problem here is, in some sense, that the measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

is too small at certain points in K. This measure, and other related measures, were studied in detail [Reference Feng, Lau and Wang14, Reference Hare, Hare and Shen21, Reference Lau and Wang31, Reference Shmerkin38] and a modified multifractal formalism was proven therein. In these cases, the failure occurs at some point

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

is too small at certain points in K. This measure, and other related measures, were studied in detail [Reference Feng, Lau and Wang14, Reference Hare, Hare and Shen21, Reference Lau and Wang31, Reference Shmerkin38] and a modified multifractal formalism was proven therein. In these cases, the failure occurs at some point

![]() $q<0$

.

$q<0$

.

In an important paper, Feng and Lau [Reference Feng and Lau13] obtain deep results about the multifractal formalism under the weak separation condition. Using a subtle Moran construction [Reference Feng, Lau and Wu15], they prove that the multifractal formalism holds for any value

![]() $q\geq 0$

, and for

$q\geq 0$

, and for

![]() $q<0$

, they give a modified multifractal formalism by considering suitable restrictions to an open ball

$q<0$

, they give a modified multifractal formalism by considering suitable restrictions to an open ball

![]() $U_{0}$

which attains the supremum in the definition of the weak separation condition of equation (1.1). Unfortunately, this result does not directly give information on the validity of the multifractal formalism for values

$U_{0}$

which attains the supremum in the definition of the weak separation condition of equation (1.1). Unfortunately, this result does not directly give information on the validity of the multifractal formalism for values

![]() $q<0$

. In some sense, the restriction avoids the breakdown of the multifractal formalism by avoiding points in K where the measure is too small.

$q<0$

. In some sense, the restriction avoids the breakdown of the multifractal formalism by avoiding points in K where the measure is too small.

To extend this perspective, we develop some new ideas. Even in regions where the overlap is not dense (that is, away from any maximal open ball

![]() $U_{0}$

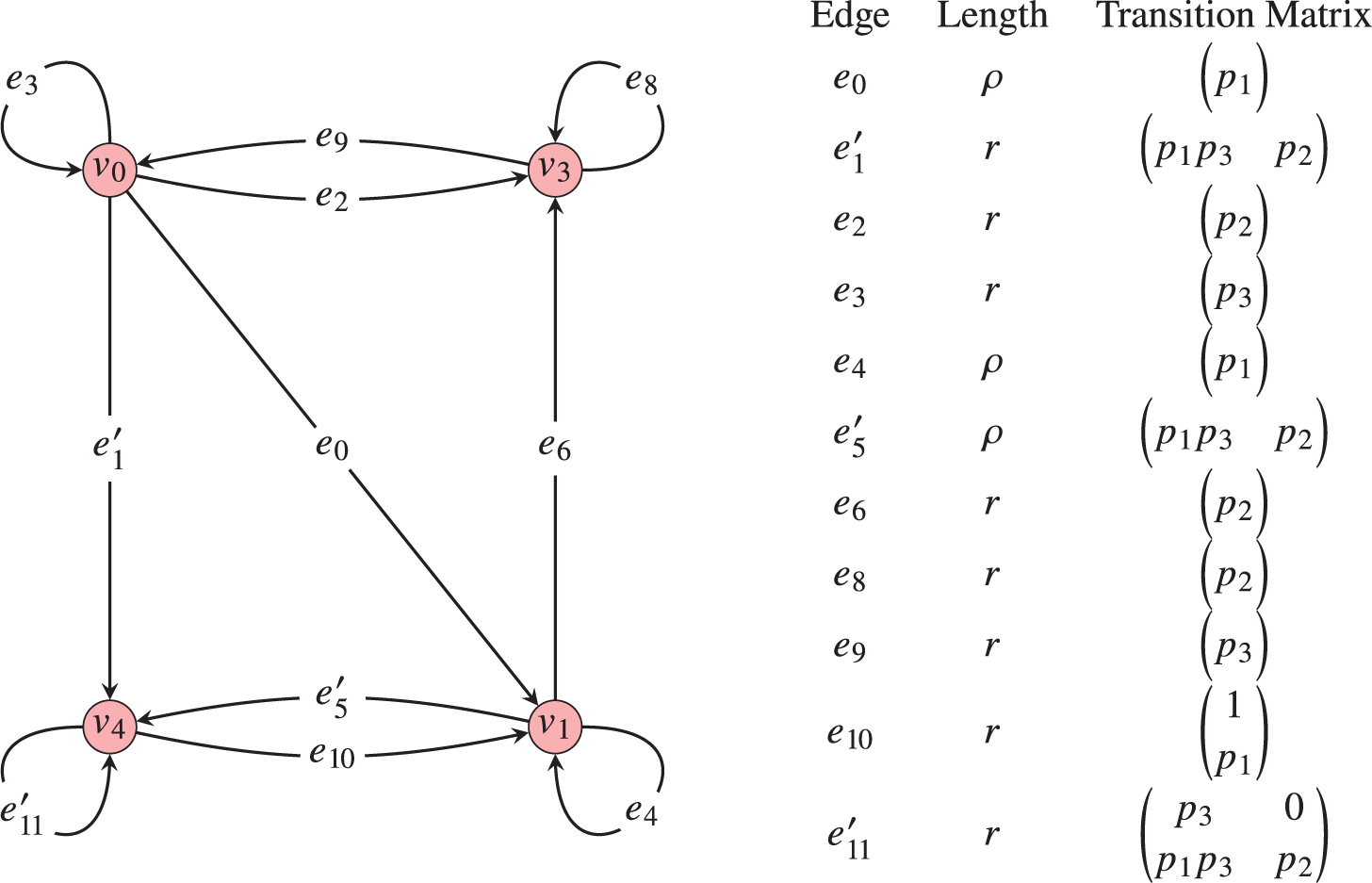

), through a general graph construction, we will show that the measure may be ‘combinatorially linked’ to regions with high density where the multifractal formalism holds. For example, consider the IFS given by the maps

$U_{0}$

), through a general graph construction, we will show that the measure may be ‘combinatorially linked’ to regions with high density where the multifractal formalism holds. For example, consider the IFS given by the maps

where

![]() $\rho>0$

,

$\rho>0$

,

![]() $r>0$

satisfy

$r>0$

satisfy

![]() $\rho +2r-\rho r\leq 1$

. This IFS was first studied by Lau and Wang [Reference Lau and Wang30] and satisfies the weak separation condition. In §5.3.3, we show that the maximal open sets

$\rho +2r-\rho r\leq 1$

. This IFS was first studied by Lau and Wang [Reference Lau and Wang30] and satisfies the weak separation condition. In §5.3.3, we show that the maximal open sets

![]() $U_{0}$

can never contain the point

$U_{0}$

can never contain the point

![]() $1$

in the self-similar set, which is a phenomenon similar to the situation of the Cantor convolution. Despite this, we can prove (as a consequence of our more general results) that the multifractal formalism still holds for the measure

$1$

in the self-similar set, which is a phenomenon similar to the situation of the Cantor convolution. Despite this, we can prove (as a consequence of our more general results) that the multifractal formalism still holds for the measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

, without restriction to a subset and with any probabilities. Our main goal in this paper is to provide a new, natural perspective for understanding the failure of the multifractal formalism, and to provide combinatorial conditions under which the multifractal formalism holds or in which one might suspect that it fails.

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

, without restriction to a subset and with any probabilities. Our main goal in this paper is to provide a new, natural perspective for understanding the failure of the multifractal formalism, and to provide combinatorial conditions under which the multifractal formalism holds or in which one might suspect that it fails.

Our starting point is the net interval construction of Feng [Reference Feng8]. In that document, for iterated function systems of the form

![]() $\{x\mapsto rx+d_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

with

$\{x\mapsto rx+d_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

with

![]() $0<r<1$

satisfying a combinatorial overlap condition known as the finite-type condition [Reference Ngai and Wang32], he obtains formulae for the values of

$0<r<1$

satisfying a combinatorial overlap condition known as the finite-type condition [Reference Ngai and Wang32], he obtains formulae for the values of

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(\Delta )$

on families of intervals

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(\Delta )$

on families of intervals

![]() $\mathcal {F}_{n}$

as products of non-negative matrices. He then uses properties of matrix products to verify differentiability of the

$\mathcal {F}_{n}$

as products of non-negative matrices. He then uses properties of matrix products to verify differentiability of the

![]() $L^{q}$

-spectrum (and thus the multifractal formalism by the prior work of Lau and Ngai [Reference Lau and Ngai28]) for values

$L^{q}$

-spectrum (and thus the multifractal formalism by the prior work of Lau and Ngai [Reference Lau and Ngai28]) for values

![]() $q>0$

. Using some different perspectives but with the same underlying approach, he proves a modified multifractal formalism for values of

$q>0$

. Using some different perspectives but with the same underlying approach, he proves a modified multifractal formalism for values of

![]() $q<0$

[Reference Feng10].

$q<0$

[Reference Feng10].

In recent work, following the techniques of Feng and operating in the same setting, Hare, Hare and various collaborators [Reference Hare, Hare and Matthews18, Reference Hare, Hare and Ng19] define a finite graph called the transition graph corresponding to the IFS. Then they determine that the set of local dimensions at special points in K called interior essential points form a closed interval, and show that the failure for the set of local dimensions to be a closed interval is determined by the existence of certain combinatorial structures in the transition graph called non-essential loop classes.

However, as observed by Testud [Reference Testud39], when the IFS does not have a common contraction ratio or a similar property (for example,

![]() $\log r_{i}/\log r_{j}\in {\mathbb {Q}}$

for all

$\log r_{i}/\log r_{j}\in {\mathbb {Q}}$

for all

![]() $i,j$

[Reference Hare, Hare and Simms22]), one cannot apply Feng’s net interval construction in a natural way.

$i,j$

[Reference Hare, Hare and Simms22]), one cannot apply Feng’s net interval construction in a natural way.

1.2 Summary of main results

Our first contribution is a generalization of the net interval construction to apply to any IFS of similarities. We determine that the distribution of

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

on certain intervals, which we call net intervals, is determined by a local overlap structure, which we call the neighbour set of the net interval (see [Reference Hare, Hare and Rutar20] for the first appearance of this construction). Our first key observations, Lemma 2.3 and Theorem 2.8, are that the neighbour set completely determines the local geometry of the attractor K and the distribution of the measure

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

on certain intervals, which we call net intervals, is determined by a local overlap structure, which we call the neighbour set of the net interval (see [Reference Hare, Hare and Rutar20] for the first appearance of this construction). Our first key observations, Lemma 2.3 and Theorem 2.8, are that the neighbour set completely determines the local geometry of the attractor K and the distribution of the measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

(up to fixed constants of comparability). This allows us in §2.4 to construct a countable directed graph which we call the transition graph of the IFS, where the vertices are the distinct neighbour sets. Then in §2.5, we associate to each edge of the transition graph a non-negative matrix called a transition matrix such that the distribution of

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

(up to fixed constants of comparability). This allows us in §2.4 to construct a countable directed graph which we call the transition graph of the IFS, where the vertices are the distinct neighbour sets. Then in §2.5, we associate to each edge of the transition graph a non-negative matrix called a transition matrix such that the distribution of

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

on net intervals is given by products of these non-negative matrices. Since we do not make any assumptions on the contraction ratios, we introduce two simple but important ideas: the notion of the transition generation (Definition 2.4) and the notion of the length of an edge (Definition 2.9). These definitions resolve the issues with the original net interval construction recognized above.

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

on net intervals is given by products of these non-negative matrices. Since we do not make any assumptions on the contraction ratios, we introduce two simple but important ideas: the notion of the transition generation (Definition 2.4) and the notion of the length of an edge (Definition 2.9). These definitions resolve the issues with the original net interval construction recognized above.

In §3, we turn our attention to the IFSs satisfying the weak separation condition. In particular, we prove the existence of a relatively open subset

![]() $K_{\operatorname {\mathrm {ess}}}\subseteq K$

called the set of interior essential points, and a corresponding subgraph of the transition graph called the essential class on which the self-similar measure has certain important regularity properties (Lemma 3.10). We call a net interval essential if its neighbour set is a vertex in the essential class. We determine that the set of interior essential points is large in two different senses.

$K_{\operatorname {\mathrm {ess}}}\subseteq K$

called the set of interior essential points, and a corresponding subgraph of the transition graph called the essential class on which the self-similar measure has certain important regularity properties (Lemma 3.10). We call a net interval essential if its neighbour set is a vertex in the essential class. We determine that the set of interior essential points is large in two different senses.

Theorem 1.1. Let

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS satisfying the weak separation condition.

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS satisfying the weak separation condition.

-

(i) If

$U_{0}$

is any open set which attains the maximality in equation (1.1), then

$U_{0}$

is any open set which attains the maximality in equation (1.1), then

$K\cap U_{0}$

is contained in a finite union of essential net intervals. In particular,

$K\cap U_{0}$

is contained in a finite union of essential net intervals. In particular,

$K\cap U_{0}\subseteq K_{\operatorname {\mathrm {ess}}}$

.

$K\cap U_{0}\subseteq K_{\operatorname {\mathrm {ess}}}$

. -

(ii) If

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

is any associated self-similar measure, then

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

is any associated self-similar measure, then

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(K\,{\setminus}\,K_{\operatorname {\mathrm {ess}}})=0$

.

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(K\,{\setminus}\,K_{\operatorname {\mathrm {ess}}})=0$

.

See Proposition 3.7 and Theorem 3.11 for proofs of these facts.

We also obtain dimensional results at certain points in K called periodic points, an idea introduced by Hare, Hare and Matthews. In Proposition 3.16, we prove that an elegant formula holds for the local dimensions at such points, and in Theorem 4.1, we show that the sets of local dimensions at periodic points are dense in the sets of upper and lower local dimensions at points in

![]() $K_{\operatorname {\mathrm {ess}}}$

. This generalizes a pre-existing result [Reference Hare, Hare and Ng19, Corollary 3.15] to the weak separation case.

$K_{\operatorname {\mathrm {ess}}}$

. This generalizes a pre-existing result [Reference Hare, Hare and Ng19, Corollary 3.15] to the weak separation case.

We then focus on understanding the multifractal formalism from the perspective of the essential class. We introduce the notion of weak regularity in Definition 4.3. Our main result in this section is the following (see Theorem 4.11 for a complete statement and proof).

Theorem 1.2. Let

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS satisfying the weak separation condition and let

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS satisfying the weak separation condition and let

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

be an associated self-similar measure. Let

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

be an associated self-similar measure. Let

![]() $E=\Delta _{1}\cup \cdots \cup \Delta _{n}$

be a finite union of essential net intervals such that

$E=\Delta _{1}\cup \cdots \cup \Delta _{n}$

be a finite union of essential net intervals such that

![]() $E\cap K$

is weakly regular. Then

$E\cap K$

is weakly regular. Then

![]() $\nu ={\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}|_{E}$

satisfies the multifractal formalism and

$\nu ={\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}|_{E}$

satisfies the multifractal formalism and

Moreover, the values of

![]() $\tau (\nu ,q)$

do not depend on the choice of

$\tau (\nu ,q)$

do not depend on the choice of

![]() $\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n}$

, and for

$\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n}$

, and for

![]() $q\geq 0$

,

$q\geq 0$

,

![]() $\tau ({\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}},q)=\tau (\nu ,q)$

.

$\tau ({\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}},q)=\tau (\nu ,q)$

.

Our verification of this modified multifractal formalism begins with [Reference Feng and Lau13, Theorem 1.2], but then uses the matrix product structure of the transition graph to move the weight of the measure from the sets

![]() $U_{0}$

to any net interval in the essential class. We note some minor improvements: rather than considering restrictions of the

$U_{0}$

to any net interval in the essential class. We note some minor improvements: rather than considering restrictions of the

![]() $L^{q}$

-spectrum to an open set, we obtain the results as a restriction to a compact subset

$L^{q}$

-spectrum to an open set, we obtain the results as a restriction to a compact subset

![]() $\Delta _{1}\cup \cdots \cup \Delta _{n}$

, where this subset can strictly contain a neighbourhood of any open set

$\Delta _{1}\cup \cdots \cup \Delta _{n}$

, where this subset can strictly contain a neighbourhood of any open set

![]() $U_{0}$

attaining the maximum in equation (1.1) (combine Theorem 1.1 and Lemma 4.6). This boundary regularity condition is discussed in detail in §4.3.

$U_{0}$

attaining the maximum in equation (1.1) (combine Theorem 1.1 and Lemma 4.6). This boundary regularity condition is discussed in detail in §4.3.

In fact, our matrix product structure provides a more general perspective for understanding the quasi-product property of Feng and Lau [Reference Feng and Lau13]; a natural analogue holds in our setting where their set

![]() $\Omega $

is replaced by a set of net intervals which have the neighbour of a fixed essential net interval. As a result, a more direct proof of Theorem 1.2 is possible. However, many details of this proof overlap with the approach of Feng and Lau, so we do not include this approach.

$\Omega $

is replaced by a set of net intervals which have the neighbour of a fixed essential net interval. As a result, a more direct proof of Theorem 1.2 is possible. However, many details of this proof overlap with the approach of Feng and Lau, so we do not include this approach.

Combining this result with Theorem 1.1, we prove the following modified multifractal formalism for any IFS satisfying the weak separation condition.

Corollary 1.3. Let

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS satisfying the weak separation condition with associated self-similar measure

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS satisfying the weak separation condition with associated self-similar measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

. Then there exists a sequence of compact sets

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

. Then there exists a sequence of compact sets

![]() $(K_{m})_{m=1}^{\infty }$

with

$(K_{m})_{m=1}^{\infty }$

with

![]() $K_{m}\subseteq K_{m+1}\subseteq K$

for each

$K_{m}\subseteq K_{m+1}\subseteq K$

for each

![]() $m\in {\mathbb {N}}$

such that:

$m\in {\mathbb {N}}$

such that:

-

(i)

$\lim _{m\to \infty }{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(K_{m})=1$

;

$\lim _{m\to \infty }{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(K_{m})=1$

; -

(ii) each

$\mu _{m}:= {\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}|_{K_{m}}$

satisfies the multifractal formalism; and

$\mu _{m}:= {\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}|_{K_{m}}$

satisfies the multifractal formalism; and -

(iii)

$\tau (\mu _{m},q)$

and

$\tau (\mu _{m},q)$

and

$D(\mu _{m})$

do not depend on the index m.

$D(\mu _{m})$

do not depend on the index m.

We note the similarity of this result to a result of Feng [Reference Feng10, Theorem 1.2], which follows from general results about the multifractal formalism of certain matrix-valued functions satisfying an irreducibility condition. However, the techniques used therein only apply naturally in the finite-type case for IFSs of the form

![]() $\{x\mapsto rx+d_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

.

$\{x\mapsto rx+d_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

.

We also obtain the following important corollary.

Corollary 1.4. Let

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS satisfying the weak separation condition with transition graph

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS satisfying the weak separation condition with transition graph

![]() $\mathcal {G}$

. Suppose there is a bound on the maximum length of a path with no vertices in the essential class. Then any associated measure

$\mathcal {G}$

. Suppose there is a bound on the maximum length of a path with no vertices in the essential class. Then any associated measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

satisfies the multifractal formalism.

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

satisfies the multifractal formalism.

In particular, suppose

![]() $\mathcal {G}$

is finite. In this situation, the only mechanism for the failure of the multifractal formalism is the existence of a cycle (a path in the transition graph which begins and ends at the same vertex) which is not contained in the essential class. This gives a combinatorial condition which guarantees that the multifractal formalism holds. In this situation, it is possible to write a finite algorithm to determine whether such a cycle exists.

$\mathcal {G}$

is finite. In this situation, the only mechanism for the failure of the multifractal formalism is the existence of a cycle (a path in the transition graph which begins and ends at the same vertex) which is not contained in the essential class. This gives a combinatorial condition which guarantees that the multifractal formalism holds. In this situation, it is possible to write a finite algorithm to determine whether such a cycle exists.

In particular, in Theorem 5.7, we apply this to the family of IFS defined in equation (1.2).

Corollary 1.5. Let

$\{S_{i}\}_{i=1}^{3}$

be the IFS defined in equation (1.2). Then for any probability weights

$\{S_{i}\}_{i=1}^{3}$

be the IFS defined in equation (1.2). Then for any probability weights

$\boldsymbol {p}=(p_{i})_{i=1}^{3}$

, the associated self-similar measure

$\boldsymbol {p}=(p_{i})_{i=1}^{3}$

, the associated self-similar measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

satisfies the complete multifractal formalism.

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

satisfies the complete multifractal formalism.

To the best knowledge of the author, this is the first example of an IFS with exact overlaps and without logarithmically commensurable contraction ratios for which the complete multifractal formalism is proven to hold. Understanding failure of the multifractal formalism is based critically on understanding the properties of cycles in the transition graph outside the essential class.

By combining our results with the work of Deng and Ngai [Reference Deng and Ngai4], we can also gain information about the differentiability of the

![]() $L^{q}$

-spectrum. In a slightly specialized case, [Reference Deng and Ngai4, Theorem 1.2] states that, for probabilities

$L^{q}$

-spectrum. In a slightly specialized case, [Reference Deng and Ngai4, Theorem 1.2] states that, for probabilities

![]() $p_{2}>p_{3}$

,

$p_{2}>p_{3}$

,

is the concave conjugate of a differentiable function. Combining this with Corollary 1.4 and involutivity of concave conjugation, we obtain the following result.

Corollary 1.6. Let

$\{S_{i}\}_{i=1}^{3}$

be the IFS defined in equation (1.2). Then if

$\{S_{i}\}_{i=1}^{3}$

be the IFS defined in equation (1.2). Then if

![]() $p_{2}>p_{3}$

, the

$p_{2}>p_{3}$

, the

![]() $L^{q}$

-spectrum

$L^{q}$

-spectrum

![]() $\tau ({\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}},q)$

is differentiable for any

$\tau ({\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}},q)$

is differentiable for any

![]() $q\in {\mathbb {R}}$

.

$q\in {\mathbb {R}}$

.

This answers some of the questions raised in [Reference Deng and Ngai4].

Finally, in §5, we investigate some specific families of IFSs to illustrate these results; notably, we give an in-depth analysis of the IFS given in equation (1.2). In fact, every example in that section has a finite transition graph: this is equivalent to the generalized finite condition of Lau and Ngai [Reference Lau and Ngai29] holding with respect to an open interval (see [Reference Hare, Hare and Rutar20, Theorem 3.4] and Remark 5.2 for a proof). Moreover, when K is a convex set, a recent result gives that the weak separation condition is equivalent to the finiteness of the transition graph [Reference Hare, Hare and Rutar20, Theorem 4.4] (see also [Reference Feng11]). In general, the author believes this to be true without any convexity assumption on K.

Conjecture 1.7. Let

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS in

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS in

![]() ${\mathbb {R}}$

with transition graph

${\mathbb {R}}$

with transition graph

![]() $\mathcal {G}$

. Then

$\mathcal {G}$

. Then

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

satisfies the weak separation condition if and only if

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

satisfies the weak separation condition if and only if

![]() $\mathcal {G}$

is finite.

$\mathcal {G}$

is finite.

The results obtained in this paper under the weak separation condition, and the similar strength to results proven under various finite-type conditions, provide some more evidence towards this equivalence in general.

1.3 Limitations and future work

We note here that Corollary 1.4 is not a dichotomy. While the non-existence of cycles outside the transition graph guarantees that the multifractal formalism holds, the converse need not hold. We have examples of measures satisfying the open set condition (with respect to an open set that is not an open interval) with cycles outside the essential class, while the open set condition guarantees that the multifractal formalism does hold. This situation is likely a by-product of the net interval construction, since our perspective is always with respect to images of the entire interval

![]() $[0,1]$

. However, there are also cases such as the Bernoulli measure associated with the IFS

$[0,1]$

. However, there are also cases such as the Bernoulli measure associated with the IFS

![]() $\{x\mapsto \rho x,x\mapsto \rho x+(1-\rho )\}$

, where

$\{x\mapsto \rho x,x\mapsto \rho x+(1-\rho )\}$

, where

![]() $1/\rho $

is the Golden mean. In this situation, the attractor is the entire interval

$1/\rho $

is the Golden mean. In this situation, the attractor is the entire interval

![]() $[0,1]$

so that the net interval construction is a natural choice. Here, even though the

$[0,1]$

so that the net interval construction is a natural choice. Here, even though the

![]() $L^{q}$

-spectrum contains a point of non-differentiability at some

$L^{q}$

-spectrum contains a point of non-differentiability at some

![]() $q_{0}<0$

and contains a cycle not contained in the essential class, the measure still satisfies the multifractal formalism [Reference Feng9]. These phenomena, and other related special cases, are studied in the recent work of Hare, Hare and Shen [Reference Hare, Hare and Shen21].

$q_{0}<0$

and contains a cycle not contained in the essential class, the measure still satisfies the multifractal formalism [Reference Feng9]. These phenomena, and other related special cases, are studied in the recent work of Hare, Hare and Shen [Reference Hare, Hare and Shen21].

More work is needed to address the general case. In [Reference Rutar35], the author investigates the multifractal analysis of measures when the transition graph is finite to provide a more detailed understanding of such examples. In particular, we obtain a greater understanding of the multifractal formalism outside the essential class as a continuation of our analysis here.

1.4 Notational conventions

We briefly mention here some of the conventions we use throughout the document. Given any set X, we write

![]() $\# X$

to denote the cardinality of X. The set

$\# X$

to denote the cardinality of X. The set

![]() ${\mathbb {R}}$

is always the metric space equipped with the usual Euclidean metric. The set

${\mathbb {R}}$

is always the metric space equipped with the usual Euclidean metric. The set

![]() ${\mathbb {N}}$

is the set of natural numbers beginning at

${\mathbb {N}}$

is the set of natural numbers beginning at

![]() $1$

. The set

$1$

. The set

![]() $B(x,t)$

is always a closed ball about x with radius t, and

$B(x,t)$

is always a closed ball about x with radius t, and

![]() $U(x,t)$

denotes the open ball. Let

$U(x,t)$

denotes the open ball. Let

![]() $E,F\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}$

be Borel sets. We denote by

$E,F\subseteq {\mathbb {R}}$

be Borel sets. We denote by

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(E)=\sup \{|x-y|:x,y\in E\}$

and

$\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(E)=\sup \{|x-y|:x,y\in E\}$

and

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(E,F)=\inf \{|x-y|:x\in E,y\in F\}$

. Given

$\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(E,F)=\inf \{|x-y|:x\in E,y\in F\}$

. Given

![]() $\delta>0$

, we write

$\delta>0$

, we write

![]() $E^{(\delta )}=\{x\in {\mathbb {R}}:\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,E)\leq \delta \}$

. By

$E^{(\delta )}=\{x\in {\mathbb {R}}:\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,E)\leq \delta \}$

. By

![]() $E^{\circ }$

, we mean the topological interior of E.

$E^{\circ }$

, we mean the topological interior of E.

Boldface quantities are typically vectors. If M is a square matrix, we denote by

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {sp}}(M)$

the spectral radius of M and

$\operatorname {\mathrm {sp}}(M)$

the spectral radius of M and

${\lVert M\rVert }=\sum _{i,j}|M_{i,j}|$

the matrix 1-norm. If

${\lVert M\rVert }=\sum _{i,j}|M_{i,j}|$

the matrix 1-norm. If

![]() $\boldsymbol {v}$

,

$\boldsymbol {v}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {w}$

are vectors with the same dimension, we write

$\boldsymbol {w}$

are vectors with the same dimension, we write

![]() $\boldsymbol {v}\preccurlyeq \boldsymbol {w}$

if

$\boldsymbol {v}\preccurlyeq \boldsymbol {w}$

if

![]() $\boldsymbol {v}_{i}\leq \boldsymbol {w}_{i}$

for each i. All matrices in this document are non-negative.

$\boldsymbol {v}_{i}\leq \boldsymbol {w}_{i}$

for each i. All matrices in this document are non-negative.

Given families of real numbers

![]() $(a_{i})_{i\in I}$

and

$(a_{i})_{i\in I}$

and

![]() $(b_{i})_{i\in I}$

, we write

$(b_{i})_{i\in I}$

, we write

![]() $a_{i}\asymp b_{i}$

if there exist constants

$a_{i}\asymp b_{i}$

if there exist constants

![]() $c_{1},c_{2}>0$

such that

$c_{1},c_{2}>0$

such that

![]() $c_{1}a_{i}\leq b_{i}\leq c_{2}a_{i}$

for all

$c_{1}a_{i}\leq b_{i}\leq c_{2}a_{i}$

for all

![]() $i\in I$

.

$i\in I$

.

The maps

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

always denote an iterated function system. We assume that

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

always denote an iterated function system. We assume that

![]() $\#\mathcal {I}\geq 2$

and its attractor K is not a singleton. Sets denoted by

$\#\mathcal {I}\geq 2$

and its attractor K is not a singleton. Sets denoted by

![]() $\Delta $

are closed intervals and often net intervals. Indices

$\Delta $

are closed intervals and often net intervals. Indices

![]() $s,t$

are used to refer to generations and radii of open and closed balls. Greek letters

$s,t$

are used to refer to generations and radii of open and closed balls. Greek letters

![]() $\sigma ,\tau ,\omega ,\phi ,\xi $

typically refer to words in

$\sigma ,\tau ,\omega ,\phi ,\xi $

typically refer to words in

![]() $\mathcal {I}^{*}$

. The Greek

$\mathcal {I}^{*}$

. The Greek

![]() $\eta $

typically refers to a path in the transition graph. The character T refers to either a transition matrix or, more occasionally, a similarity map, depending on context.

$\eta $

typically refers to a path in the transition graph. The character T refers to either a transition matrix or, more occasionally, a similarity map, depending on context.

2 Iterated function systems through net intervals

2.1 Iterated function systems of similarities in

${\mathbb {R}}$

${\mathbb {R}}$

Let

![]() $\mathcal {I}$

be a non-empty finite index set. By an iterated function system of similarities (IFS)

$\mathcal {I}$

be a non-empty finite index set. By an iterated function system of similarities (IFS)

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

, we mean a finite set of similarities

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

, we mean a finite set of similarities

with

![]() $0<\vert r_{i}\vert <1$

. We say that the IFS is (positive) equicontractive if each

$0<\vert r_{i}\vert <1$

. We say that the IFS is (positive) equicontractive if each

![]() $r_{i}=r>0$

.

$r_{i}=r>0$

.

Each IFS generates a unique non-empty compact set K satisfying

$$ \begin{align*} K=\bigcup_{i\in\mathcal{I}}S_{i}(K). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} K=\bigcup_{i\in\mathcal{I}}S_{i}(K). \end{align*} $$

This set K is known as the associated self-similar set. Throughout, we will assume K is not a singleton. By rescaling and translating the

![]() $d_{i}$

if necessary, without loss of generality, we may assume the convex hull of K is

$d_{i}$

if necessary, without loss of generality, we may assume the convex hull of K is

![]() $[0,1]$

.

$[0,1]$

.

Given a probability vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {p}=(p_{i})_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

, where

$\boldsymbol {p}=(p_{i})_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

, where

![]() $p_{i}>0$

and

$p_{i}>0$

and

![]() $\sum _{i\in \mathcal {I}}p_{i}=1$

, there exists a unique Borel measure

$\sum _{i\in \mathcal {I}}p_{i}=1$

, there exists a unique Borel measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

with

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

with

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {supp}}{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}=K$

satisfying

$\operatorname {\mathrm {supp}}{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}=K$

satisfying

$$ \begin{align} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(E) = \sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}}p_{i}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(S_{i}^{-1}(E)) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(E) = \sum_{i\in\mathcal{I}}p_{i}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(S_{i}^{-1}(E)) \end{align} $$

for any Borel set

![]() $E\subseteq K$

. This measure

$E\subseteq K$

. This measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

is known as an associated self-similar measure.

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

is known as an associated self-similar measure.

Let

![]() $\mathcal {I}^{*}$

denote the set of all finite words on

$\mathcal {I}^{*}$

denote the set of all finite words on

![]() $\mathcal {I}$

. Given

$\mathcal {I}$

. Given

![]() $\sigma =(\sigma _{1},\ldots ,\sigma _{j})\in \mathcal {I}^{*}$

, we denote

$\sigma =(\sigma _{1},\ldots ,\sigma _{j})\in \mathcal {I}^{*}$

, we denote

Given

![]() $t>0,$

put

$t>0,$

put

We refer to the set of

![]() $\sigma \in \Lambda _{t}$

as the words of generation t. We remark that in the literature, it is more common to see this defined by the rule

$\sigma \in \Lambda _{t}$

as the words of generation t. We remark that in the literature, it is more common to see this defined by the rule

![]() $|r_{\sigma }|\leq t <|r_{\sigma ^{-}}|$

. The two choices are essentially equivalent, but this choice is more convenient for our purposes.

$|r_{\sigma }|\leq t <|r_{\sigma ^{-}}|$

. The two choices are essentially equivalent, but this choice is more convenient for our purposes.

2.2 Neighbour sets

The notions of net intervals and neighbour sets were introduced in [Reference Feng8, Reference Hare, Hare and Simms22]. In [Reference Hare, Hare and Rutar20], these notions were extended to an arbitrary IFS, and we present those definitions here. We then continue the discussion to define the children of a net interval, and show in Theorem 2.8 that the children depend only on the neighbour set of the parent.

Let

![]() $h_{1},\ldots ,h_{s(t)}$

be the collection of distinct elements of the set

$h_{1},\ldots ,h_{s(t)}$

be the collection of distinct elements of the set

![]() $\{S_{\sigma }(0),S_{\sigma }(1):\sigma \in \Lambda _{t}\}$

listed in strictly ascending order; we refer to this set as the endpoints of generation t. Set

$\{S_{\sigma }(0),S_{\sigma }(1):\sigma \in \Lambda _{t}\}$

listed in strictly ascending order; we refer to this set as the endpoints of generation t. Set

Elements of

![]() $\mathcal {F}_{t}$

are called net intervals of generation t. Write

$\mathcal {F}_{t}$

are called net intervals of generation t. Write

![]() $\mathcal {F}=\bigcup _{t>0}\mathcal {F}_{t}$

to denote the set of all possible net intervals.

$\mathcal {F}=\bigcup _{t>0}\mathcal {F}_{t}$

to denote the set of all possible net intervals.

Suppose

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}$

. We denote by

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}$

. We denote by

![]() $T_{\Delta }$

the unique contraction

$T_{\Delta }$

the unique contraction

![]() $T_{\Delta }(x)=rx+a$

with

$T_{\Delta }(x)=rx+a$

with

![]() $r>0$

such that

$r>0$

such that

Of course,

![]() $r=\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )$

and a is the left endpoint of

$r=\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )$

and a is the left endpoint of

![]() $\Delta $

.

$\Delta $

.

Definition 2.1. We will say that a similarity

![]() $f(x)=Rx+a$

is a neighbour of

$f(x)=Rx+a$

is a neighbour of

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

if there exists some

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

if there exists some

![]() $\sigma \in \Lambda _{t}$

such that

$\sigma \in \Lambda _{t}$

such that

![]() $S_{\sigma }(K)\cap \Delta ^{\circ }\neq \emptyset $

and

$S_{\sigma }(K)\cap \Delta ^{\circ }\neq \emptyset $

and

$f=T_{\Delta }^{-1}\circ S_{\sigma }$

. In this case, we also say that

$f=T_{\Delta }^{-1}\circ S_{\sigma }$

. In this case, we also say that

![]() $S_{\sigma }$

generates the neighbour f. The neighbour set of

$S_{\sigma }$

generates the neighbour f. The neighbour set of

![]() $\Delta $

is the maximal set

$\Delta $

is the maximal set

where each

$f_{i}=T_{\Delta }^{-1}\circ S_{\sigma _{i}}$

is a distinct neighbour of

$f_{i}=T_{\Delta }^{-1}\circ S_{\sigma _{i}}$

is a distinct neighbour of

![]() $\Delta $

.

$\Delta $

.

Since

![]() $K=\bigcup _{\sigma \in \Lambda _{t}}S_{\sigma }(K)$

, every net interval has a non-empty neighbour set.

$K=\bigcup _{\sigma \in \Lambda _{t}}S_{\sigma }(K)$

, every net interval has a non-empty neighbour set.

If

![]() $\sigma $

generates a neighbour of

$\sigma $

generates a neighbour of

![]() $\Delta $

, then

$\Delta $

, then

![]() $S_{\sigma }([0,1])\supseteq \Delta $

. When the generation of

$S_{\sigma }([0,1])\supseteq \Delta $

. When the generation of

![]() $\Delta $

is implicit, we will simply write

$\Delta $

is implicit, we will simply write

![]() ${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )$

. For notational convenience, we define the quantity

${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )$

. For notational convenience, we define the quantity

![]() ${{R_{\max }}}(\Delta )=\max \{|R|:\{x\mapsto Rx+a\}\in {\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )\}$

, which depends only on

${{R_{\max }}}(\Delta )=\max \{|R|:\{x\mapsto Rx+a\}\in {\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )\}$

, which depends only on

![]() ${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )$

.

${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )$

.

Remark 2.2. For an IFS of the form

![]() $\{S_{i}(x)=r x+d_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

where

$\{S_{i}(x)=r x+d_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

where

![]() $0<r<1$

is fixed, the notion of a neighbour set is related to the characteristic vector of Feng [Reference Feng8]. We describe the equivalence here.

$0<r<1$

is fixed, the notion of a neighbour set is related to the characteristic vector of Feng [Reference Feng8]. We describe the equivalence here.

Let

![]() $\Delta =[a,b]\in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

be some net interval and let n be such that

$\Delta =[a,b]\in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

be some net interval and let n be such that

![]() $r^{n}<t\leq r^{n-1}$

. Let

$r^{n}<t\leq r^{n-1}$

. Let

![]() $\sigma _{1},\ldots ,\sigma _{m}$

generate distinct neighbours of

$\sigma _{1},\ldots ,\sigma _{m}$

generate distinct neighbours of

![]() $\Delta $

, so that

$\Delta $

, so that

![]() $r_{\sigma _{i}}=r^{n}$

for each

$r_{\sigma _{i}}=r^{n}$

for each

![]() $1\leq i\leq m$

. Then the (reduced) characteristic vector of

$1\leq i\leq m$

. Then the (reduced) characteristic vector of

![]() $\Delta $

(see [Reference Feng8, §2] for notation) is determined by

$\Delta $

(see [Reference Feng8, §2] for notation) is determined by

whereas the neighbour set of

![]() $\Delta $

is given by

$\Delta $

is given by

$$ \begin{align*} {\mathcal{V}}(\Delta) &= \{T_{\Delta}^{-1}\circ S_{\sigma_{i}}\} = \bigg\{x\mapsto \frac{S_{\sigma_{i}}(x)-a}{\operatorname{\mathrm{diam}}(\Delta)}\bigg\}\\[6pt] &= \bigg\{x\mapsto \frac{x}{r^{-n}\operatorname{\mathrm{diam}}(\Delta)}+\frac{S_{\sigma_{i}}(0)-a}{\operatorname{\mathrm{diam}}(\Delta)}\bigg\}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} {\mathcal{V}}(\Delta) &= \{T_{\Delta}^{-1}\circ S_{\sigma_{i}}\} = \bigg\{x\mapsto \frac{S_{\sigma_{i}}(x)-a}{\operatorname{\mathrm{diam}}(\Delta)}\bigg\}\\[6pt] &= \bigg\{x\mapsto \frac{x}{r^{-n}\operatorname{\mathrm{diam}}(\Delta)}+\frac{S_{\sigma_{i}}(0)-a}{\operatorname{\mathrm{diam}}(\Delta)}\bigg\}. \end{align*} $$

Thus, when the IFS has a common positive contraction ratio, our neighbour set construction can be interpreted directly as a normalized version of Feng’s characteristic vector.

When the IFS has arbitrary contraction ratios, there is no clear choice of normalization factor analogous to

![]() $\ell _{n}(\Delta )$

that is uniform across all net intervals

$\ell _{n}(\Delta )$

that is uniform across all net intervals

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

. This issue is resolved by normalizing directly by

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

. This issue is resolved by normalizing directly by

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )$

, but now it is no longer clear how to define the children of a net interval in a global way. Instead, a local definition for the children of net intervals and the analogue of [Reference Feng8, Lemma 2.1] are given in §2.3.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )$

, but now it is no longer clear how to define the children of a net interval in a global way. Instead, a local definition for the children of net intervals and the analogue of [Reference Feng8, Lemma 2.1] are given in §2.3.

Neighbour sets of net intervals are relevant in the sense that they completely determine the local geometry of K in the net interval, as well as the behaviour of associated self-similar measures on Borel subsets of the net interval. To be precise, we have the following lemma.

Lemma 2.3. Let

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS as in equation (2.1) with attractor K and associated self-similar measure

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an IFS as in equation (2.1) with attractor K and associated self-similar measure

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

. Suppose

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}$

. Suppose

![]() $\Delta _{1},\Delta _{2}$

are net intervals with

$\Delta _{1},\Delta _{2}$

are net intervals with

![]() ${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{1})={\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{2})$

. Then there exists a surjective similarity

${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{1})={\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{2})$

. Then there exists a surjective similarity

![]() $g:\Delta _{1}\cap K\to \Delta _{2}\cap K$

and constants

$g:\Delta _{1}\cap K\to \Delta _{2}\cap K$

and constants

![]() $c_{1},c_{2}>0$

such that if

$c_{1},c_{2}>0$

such that if

![]() $E\subseteq \Delta _{1}$

is any Borel set,

$E\subseteq \Delta _{1}$

is any Borel set,

Proof. By definition of the neighbour set, if

![]() $\Delta $

is any net interval, we have

$\Delta $

is any net interval, we have

$$ \begin{align*} \Delta\cap K = \bigcup_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta)}(T_{\Delta}\circ f(K))\cap\Delta. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \Delta\cap K = \bigcup_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta)}(T_{\Delta}\circ f(K))\cap\Delta. \end{align*} $$

Set

$g=T_{\Delta _{2}}\circ T_{\Delta _{1}}^{-1}$

so that g is clearly a similarity, and applying this observation to

$g=T_{\Delta _{2}}\circ T_{\Delta _{1}}^{-1}$

so that g is clearly a similarity, and applying this observation to

![]() $\Delta _{1}$

and

$\Delta _{1}$

and

![]() $\Delta _{2}$

, we have

$\Delta _{2}$

, we have

$$ \begin{align*} g(\Delta_{1}\cap K) &= \bigcup_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta_{1})}g(T_{\Delta_{1}}\circ f(K)\cap\Delta_{1}) = \bigcup_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta_{1})}(g\circ T_{\Delta_{1}}\circ f(K))\cap g(\Delta_{1})\\[3pt] &= \bigcup_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta_{2})}(T_{\Delta_{2}}\circ f(K))\cap\Delta_{2} = \Delta_{2}\cap K. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} g(\Delta_{1}\cap K) &= \bigcup_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta_{1})}g(T_{\Delta_{1}}\circ f(K)\cap\Delta_{1}) = \bigcup_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta_{1})}(g\circ T_{\Delta_{1}}\circ f(K))\cap g(\Delta_{1})\\[3pt] &= \bigcup_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta_{2})}(T_{\Delta_{2}}\circ f(K))\cap\Delta_{2} = \Delta_{2}\cap K. \end{align*} $$

Thus g is surjective with the correct image.

We now verify the measure property. By the invariant property of the self-similar measure in equation (2.2), if

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

is any net interval and

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

is any net interval and

![]() $E\subseteq \Delta $

is any Borel set,

$E\subseteq \Delta $

is any Borel set,

$$ \begin{align*} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(E) &= \sum_{\sigma\in\Lambda_{t}}p_{\sigma{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}}\circ S_{\sigma}^{-1}(E)= \sum_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta)}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(f^{-1}\circ T_{\Delta}^{-1}(E))\sum_{\substack{\sigma\in\Lambda_{t}\\ \sigma\text{ generates }f}}p_{\sigma}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(E) &= \sum_{\sigma\in\Lambda_{t}}p_{\sigma{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}}\circ S_{\sigma}^{-1}(E)= \sum_{f\in{\mathcal{V}}(\Delta)}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(f^{-1}\circ T_{\Delta}^{-1}(E))\sum_{\substack{\sigma\in\Lambda_{t}\\ \sigma\text{ generates }f}}p_{\sigma}. \end{align*} $$

Since f is a neighbour of

![]() $\Delta $

, there is at least one

$\Delta $

, there is at least one

![]() $\sigma $

generating f. In particular, say

$\sigma $

generating f. In particular, say

![]() $\Delta _{1}\in \mathcal {F}_{t_{1}}$

and

$\Delta _{1}\in \mathcal {F}_{t_{1}}$

and

![]() $\Delta _{2}\in \mathcal {F}_{t_{2}}$

, write

$\Delta _{2}\in \mathcal {F}_{t_{2}}$

, write

![]() ${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{1})={\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{2})=\{f_{1},\ldots ,f_{m}\}$

, and set for each

${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{1})={\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{2})=\{f_{1},\ldots ,f_{m}\}$

, and set for each

![]() $1\leq i\leq m$

and

$1\leq i\leq m$

and

![]() $j=1,2$

$j=1,2$

$$ \begin{align*} q_{i,j} := \sum_{\substack{\sigma\in\Lambda_{t_{j}}\\ \sigma\text{ generates }f_{i}}}p_{\sigma}>0. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} q_{i,j} := \sum_{\substack{\sigma\in\Lambda_{t_{j}}\\ \sigma\text{ generates }f_{i}}}p_{\sigma}>0. \end{align*} $$

Set

![]() $c_{1} = \min \{q_{i,2}/q_{i,1}:1\leq i\leq m\}$

. We then have for

$c_{1} = \min \{q_{i,2}/q_{i,1}:1\leq i\leq m\}$

. We then have for

![]() $E\subseteq \Delta _{1}$

that

$E\subseteq \Delta _{1}$

that

![]() $g(E)\subseteq \Delta _{2}$

so that

$g(E)\subseteq \Delta _{2}$

so that

$$ \begin{align*} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(g(E)) &= \sum_{i=1}^{m}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(f_{i}^{-1}\circ T_{\Delta_{2}}^{-1}\circ g(E))q_{i,2}\\[3pt] &\geq c_{1}\sum_{i=1}^{m} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(f_{i}^{-1}\circ T_{\Delta_{1}}^{-1}(E)) q_{i,1}= c_{1}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(E). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(g(E)) &= \sum_{i=1}^{m}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(f_{i}^{-1}\circ T_{\Delta_{2}}^{-1}\circ g(E))q_{i,2}\\[3pt] &\geq c_{1}\sum_{i=1}^{m} {\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(f_{i}^{-1}\circ T_{\Delta_{1}}^{-1}(E)) q_{i,1}= c_{1}{\mu_{\boldsymbol{p}}}(E). \end{align*} $$

Similarly, we have

![]() ${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(g(E))\leq c_{2}{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(E)$

, where

${\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(g(E))\leq c_{2}{\mu _{\boldsymbol {p}}}(E)$

, where

![]() $c_{2}=\min \{q_{i,1}/q_{i,2}:1\leq i\leq m\}$

.

$c_{2}=\min \{q_{i,1}/q_{i,2}:1\leq i\leq m\}$

.

We will revisit these ideas in §2.5.

2.3 Children of net intervals

Let

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}$

have neighbour set

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}$

have neighbour set

![]() $\{f_{1},\ldots ,f_{m}\}$

, and for each i, let

$\{f_{1},\ldots ,f_{m}\}$

, and for each i, let

![]() $S_{\sigma _{i}}$

generate the neighbour

$S_{\sigma _{i}}$

generate the neighbour

![]() $f_{i}$

(recall that this means that

$f_{i}$

(recall that this means that

![]() $S_{\sigma _{i}}(K)\cap \Delta ^{\circ }\neq \emptyset $

and

$S_{\sigma _{i}}(K)\cap \Delta ^{\circ }\neq \emptyset $

and

$f_{i}=T_{\Delta }^{-1}\circ S_{\sigma _{i}}$

).

$f_{i}=T_{\Delta }^{-1}\circ S_{\sigma _{i}}$

).

Definition 2.4. We define the ancestral generation of

![]() $\Delta $

, denoted

$\Delta $

, denoted

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )$

, and the transition generation of

$\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )$

, and the transition generation of

![]() $\Delta $

, denoted

$\Delta $

, denoted

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )$

, to be positive real values such that

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )$

, to be positive real values such that

$$ \begin{align*} \bigcap_{i=1}^{m} (|r_{\sigma_{i}}|,|r_{\sigma_{i}^{-}}|]=(\operatorname{\mathrm{tg}}(\Delta),\operatorname{\mathrm{ag}}(\Delta)]. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \bigcap_{i=1}^{m} (|r_{\sigma_{i}}|,|r_{\sigma_{i}^{-}}|]=(\operatorname{\mathrm{tg}}(\Delta),\operatorname{\mathrm{ag}}(\Delta)]. \end{align*} $$

Note that

![]() $0<\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )\leq 1$

; if

$0<\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )\leq 1$

; if

![]() $\Delta =[0,1]$

, we say

$\Delta =[0,1]$

, we say

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )=\infty $

. It is straightforward to verify that:

$\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )=\infty $

. It is straightforward to verify that:

-

•

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )={{R_{\max }}}(\Delta )\cdot \operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )$

;

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )={{R_{\max }}}(\Delta )\cdot \operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )$

; -

•

$t\in (\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta ),\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )]$

;

$t\in (\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta ),\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )]$

; -

• for any

$s\in (\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta ),\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )]$

,

$s\in (\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta ),\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )]$

,

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{s}$

and

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{s}$

and

${\mathcal {V}}_{s}(\Delta )={\mathcal {V}}_{t}(\Delta )$

; and

${\mathcal {V}}_{s}(\Delta )={\mathcal {V}}_{t}(\Delta )$

; and -

• if

$s\notin (\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta ),\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )]$

, either

$s\notin (\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta ),\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta )]$

, either

$\Delta \notin \mathcal {F}_{s}$

or

$\Delta \notin \mathcal {F}_{s}$

or

${\mathcal {V}}_{s}(\Delta )\neq {\mathcal {V}}_{t}(\Delta )$

.

${\mathcal {V}}_{s}(\Delta )\neq {\mathcal {V}}_{t}(\Delta )$

.

Let

![]() $t>0$

and

$t>0$

and

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

. Let

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

. Let

![]() $(\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n})\in \mathcal {F}_{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )}$

be the distinct net intervals, ordered from left to right, of generation

$(\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n})\in \mathcal {F}_{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )}$

be the distinct net intervals, ordered from left to right, of generation

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )$

contained in

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )$

contained in

![]() $\Delta $

. Note that either

$\Delta $

. Note that either

![]() $n>1$

or if

$n>1$

or if

![]() $n=1$

, then

$n=1$

, then

![]() ${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )\neq {\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{1})$

. Then we call the tuple

${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )\neq {\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{1})$

. Then we call the tuple

![]() $(\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n})$

the children of

$(\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n})$

the children of

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

. Note that for any child

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

. Note that for any child

![]() $\Delta _{i}$

of

$\Delta _{i}$

of

![]() $\Delta $

,

$\Delta $

,

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta _{i})=\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )$

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {ag}}(\Delta _{i})=\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )$

.

Similarly, we define the parent of

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

to be the net interval

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

to be the net interval

![]() $\widehat \Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{s}$

with

$\widehat \Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{s}$

with

![]() $s> t$

, where

$s> t$

, where

![]() $\Delta $

is a child of

$\Delta $

is a child of

![]() $\widehat \Delta $

.

$\widehat \Delta $

.

Remark 2.5. One way to think about the children of a net interval is as follows. Enumerate the points

![]() $\{\prod _{i\in \mathcal {I}}|r_{i}^{a_{i}}|:a_{i}\in \{0\}\cup {\mathbb {N}}\}$

in decreasing order

$\{\prod _{i\in \mathcal {I}}|r_{i}^{a_{i}}|:a_{i}\in \{0\}\cup {\mathbb {N}}\}$

in decreasing order

![]() $(t_{i})_{i=1}^{\infty }$

. Since

$(t_{i})_{i=1}^{\infty }$

. Since

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )=|r_{\sigma }|$

for some

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )=|r_{\sigma }|$

for some

![]() $\sigma \in \mathcal {I}^{*}$

, the transitions to new generations must happen at some

$\sigma \in \mathcal {I}^{*}$

, the transitions to new generations must happen at some

![]() $t_{i}$

. However, if

$t_{i}$

. However, if

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t_{k}}$

, it may not hold that

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t_{k}}$

, it may not hold that

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )=t_{k+1}$

. The children are the net intervals in generation

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )=t_{k+1}$

. The children are the net intervals in generation

![]() $t_{m}$

, where

$t_{m}$

, where

![]() $m\geq k+1$

is minimal such that either

$m\geq k+1$

is minimal such that either

![]() $\Delta \notin \mathcal {F}_{t_{m}}$

or

$\Delta \notin \mathcal {F}_{t_{m}}$

or

![]() ${\mathcal {V}}_{t_{m}}(\Delta )\neq {\mathcal {V}}_{t_{k}}(\Delta )$

.

${\mathcal {V}}_{t_{m}}(\Delta )\neq {\mathcal {V}}_{t_{k}}(\Delta )$

.

If the IFS is of the form

![]() $\{x\mapsto rx+d_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

for some fixed

$\{x\mapsto rx+d_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

for some fixed

![]() $0<r<1$

and

$0<r<1$

and

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{r^{n}}$

, then

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{r^{n}}$

, then

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )=r^{n+1}$

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )=r^{n+1}$

.

Example 2.6. For a worked example of neighbour set and children computations of a non-commensurable IFS, see §5.3.

A key feature of the preceding definitions is that, in a sense that will be made precise, the neighbour set of some net interval

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{\alpha }$

completely determines the placement and the neighbour set of each child of the net interval.

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{\alpha }$

completely determines the placement and the neighbour set of each child of the net interval.

Definition 2.7. Suppose

![]() $\Delta =[a,b]\in \mathcal {F}$

has children

$\Delta =[a,b]\in \mathcal {F}$

has children

![]() $(\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n})$

in generation

$(\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n})$

in generation

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )$

. For some fixed child

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )$

. For some fixed child

![]() $\Delta _{i}=[a_{i},b_{i}]$

, we define the position index

$\Delta _{i}=[a_{i},b_{i}]$

, we define the position index

![]() $q(\Delta ,\Delta _{i})=(a_{i}-a)/\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )$

.

$q(\Delta ,\Delta _{i})=(a_{i}-a)/\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )$

.

One purpose of the position index is to distinguish the children of

![]() $\Delta $

which have the same neighbour set.

$\Delta $

which have the same neighbour set.

We have the following basic result. The insight behind this result is straightforward. The children of a net interval are determined precisely by the words which generate the neighbours of maximal length. Up to normalization by the position of

![]() $\Delta $

, these correspond uniquely to the neighbours of

$\Delta $

, these correspond uniquely to the neighbours of

![]() $\Delta $

with maximal contraction factor.

$\Delta $

with maximal contraction factor.

Theorem 2.8. Let

![]() $\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an arbitrary IFS. Let

$\{S_{i}\}_{i\in \mathcal {I}}$

be an arbitrary IFS. Let

![]() $\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

have children

$\Delta \in \mathcal {F}_{t}$

have children

![]() $(\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n})$

in

$(\Delta _{1},\ldots ,\Delta _{n})$

in

![]() $\mathcal {F}_{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )}$

. Then for any

$\mathcal {F}_{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )}$

. Then for any

![]() $\Delta ^{\prime }\in \mathcal {F}_{s}$

with

$\Delta ^{\prime }\in \mathcal {F}_{s}$

with

![]() ${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )={\mathcal {V}}(\Delta ^{\prime })$

and children

${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta )={\mathcal {V}}(\Delta ^{\prime })$

and children

![]() $(\Delta _{1}^{\prime },\ldots ,\Delta _{n^{\prime }}^{\prime })$

in

$(\Delta _{1}^{\prime },\ldots ,\Delta _{n^{\prime }}^{\prime })$

in

![]() $\mathcal {F}_{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta ^{\prime })}$

, we have that

$\mathcal {F}_{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta ^{\prime })}$

, we have that

![]() $n=n^{\prime }$

and for any

$n=n^{\prime }$

and for any

![]() $1\leq i\leq n$

:

$1\leq i\leq n$

:

-

(i)

${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{i}^{\prime })={\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{i})$

;

${\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{i}^{\prime })={\mathcal {V}}(\Delta _{i})$

; -

(ii)

$q(\Delta ^{\prime },\Delta _{i}^{\prime })=q(\Delta ,\Delta _{i})$

;

$q(\Delta ^{\prime },\Delta _{i}^{\prime })=q(\Delta ,\Delta _{i})$

; -

(iii)

${\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta _{i}^{\prime })}/{\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta ^{\prime })}={\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta _{i})}/{\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )}$

; and

${\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta _{i}^{\prime })}/{\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta ^{\prime })}={\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta _{i})}/{\operatorname {\mathrm {diam}}(\Delta )}$

; and -

(iv)

${\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta _{i})}/{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )}={\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta _{i}^{\prime })}/{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta _{i})}$

.

${\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta _{i})}/{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta )}={\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta _{i}^{\prime })}/{\operatorname {\mathrm {tg}}(\Delta _{i})}$

.

Proof. Given a map

![]() $f(x)=rx+d$

, we set

$f(x)=rx+d$

, we set

![]() $R(f)=|r|$

.

$R(f)=|r|$

.