Introduction

In a clichéd view, ‘lobbyists’ are often imagined to inhabit darkened, smoke-filled rooms, and to earn good money just by whispering in the ears of government ‘You’ve got to do a favor to my business, to my corporation’. What most people hardly think of is that the region, the state, the province, or the Land they live in also engages in lobbying.

However, in 21st-century multi-level governance, regional governments have indeed increasingly assumed the role of lobbyists themselves.Footnote 1 For example, more than 240 European regions maintain their own regional offices, staffed with lobbyists, in downtown Brussels—the capital of the European Union (EU) (Rodriguez-Pose and Courty, Reference Rodriguez-Pose and Courty2018, 200; see Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Donas and Fraussen2015; Tatham, Reference Tatham2016; Huwyler et al., Reference Huwyler, Tatham and Blatter2018). In the US, more than 900 State and local governments have annually spent around 70 million tax dollars on making lobbying contacts in Washington, DC (Zhang, Reference Zhang2022, 37). These governments-as-lobbyists make up almost a fifth of all organized interests groups with a presence in national politics (Goldstein and You, Reference Goldstein and You2017, 864). All 16 German Länder have set up shop in Berlin (Der Bundesrat, 2025)—a major trend also observed in many other multi-level polities (e.g., Mueller, Reference Mueller2024b; Freiburghaus, Reference Freiburghaus2024a, b; Payson and Freiburghaus, Reference Payson, Freiburghaus and Chari2025). Despite the steady rise in intergovernmental lobbyingFootnote 2 —where regional governments seek to influence upper-level policies in alignment with regional interests (e.g., Einstein and Glick, Reference Einstein and Glick2017; Freiburghaus, Reference Freiburghaus2024a, b, Payson, Reference Payson2020a, b; Reference Payson2022; Zhang, Reference Zhang2022)—we still know surprisingly little about why some regional governments succeed in shaping federal policy outcomes while others do not. Explaining interest group influence or lobbying success has long been central to the study of interest and advocacy group politics, lobbying, and public policy, and more broadly, democratic representation (e.g., Truman, Reference Truman1951; Dahl, Reference Dahl1961, Reference Dahl1971; Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967). Formative research has well explored what enables organized interests, corporations, pressure groups, and/or NGOs to achieve their policy goals effectively. But although the existing literature on interest group mobilization occasionally acknowledges that governments also engage in lobbying (e.g., Milbrath, Reference Milbrath1963; Baumgartner and Leech, Reference Baumgartner and Leech1998; Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009), this particular set of advocacy actors has often been excluded.

Even within the emergent field of intergovernmental lobbying, the crucial group of regional governments has been completely overlooked. Foundational studies of intergovernmental lobbying have predominantly focused on two areas: advocacy actions by local governments, particularly cities (e.g., Loftis and Kettler, Reference Loftis and Kettler2015; Goldstein and You, Reference Goldstein and You2017; Strickland, Reference Strickland2019; Payson, Reference Payson2020a; Payson, Reference Payson2020b; Payson, Reference Payson2022; Payson and Freiburghaus, Reference Payson, Freiburghaus and Chari2025; Zhang, Reference Zhang2022), and lobbying efforts of regional governments at the supranational level, particularly vis-à-vis the EU (e.g., Broscheid and Coen, Reference Broscheid and Coen2007; Callanan and Tatham, Reference Callanan and Tatham2014; Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Donas and Fraussen2015; Spohr et al., Reference Spohr, Bernhagen and Krüger2025; Tatham, Reference Tatham2016; Huwyler et al., Reference Huwyler, Tatham and Blatter2018; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2024). While both literatures provide valuable insights, they fall short in addressing the distinct position of regional governments lobbying at the domestic federal level (but see Freiburghaus, Reference Freiburghaus2024a). Unlike local governments, regional governments in domestic multi-level systems operate within a framework of constitutionally protected channels for participation in federal decision-making, such as bicameralism (see Watts, Reference Watts2008; Benz, Reference Benz2018).

In this article, I aim to explain the intergovernmental lobbying success of regional governments. I argue that, due to their unique position, neither ‘classical’ theories of membership-based, business-leaning interest group advocacy nor existing theories of intergovernmental mobilization are fully applicable to regional governments. Both sets of theories assume that key resources—namely money or legitimacy—are decisive for lobbying success. However, regional governments only have limited control over these key resources. Therefore, I propose a theoretical framework of intergovernmental lobbying success, specifically tailored to regional governments.

To empirically test my theoretical propositions, I rely on a new and original data set that comprehensively documents the policy influence of all 26 Swiss cantonal governments in federal siting decisions. Switzerland, long regarded as a ‘federation of particular interest’ (Watts, Reference Watts2008, 32), serves as a ‘typical case’ (Seawright and Gerring, Reference Seawright and Gerring2008)—an ideal context for exploring the varying success of regional governments in influencing federal policy decisions. Methodologically, I resort to Crisp-Set Qualitative-Comparative Analysis (csQCA) which is, as a set-theoretic method, the most suitable tool to detect multiple and complex conjunctural causal pathways to intergovernmental lobbying success (e.g., Ragin, Reference Ragin1987; Oana et al., Reference Oana, Schneider and Thomann2021; Schneider, Reference Schneider2024).

This article makes a significant contribution to the fields of comparative politics, multi-level governance, public policy, federalism, and interest group and lobbying studies. The central theoretical contribution is a theoretical framework of intergovernmental lobbying success, which bridges the gap between federalism and multi-level governance research, and interest group and lobbying studies. Despite their common roots in The Federalist Papers ([1787/88] Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Madison and Jay2008), these two foundational strands of political science have developed in isolation. This separation is a missed opportunity, as both areas fundamentally seek to explain political influence and the representation of diverse interests, which are core elements of pluralist democracy.

Empirically, this article provides, to the best of the author’s knowledge, the first explanation of intergovernmental lobbying success for regional governments. While prior studies have explored why regional governments engage in federal-level lobbying (e.g., Jensen, Reference Jensen2016; Zhang, Reference Zhang2022) or the specific mix of advocacy tools they use (e.g., Mueller, Reference Mueller2024b), the critical question of ‘winning’ or ‘losing’ in lobbying efforts has not yet been addressed.Footnote 3 This oversight is a significant gap in the literature, prompting Grossmann (Reference Grossmann and Grossmann2013), 61 to describe intergovernmental lobbying as ‘the largest hole in the mobilization literature’.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 critiques current interest group and intergovernmental mobilization theories, and introduces a theoretical framework of intergovernmental lobbying success. Section 3 outlines the data and methods, while section 4 presents my empirical findings. The conclusion evaluates implications and suggests future research directions (section 5).

Theoretical argument

Why existing theories of interest group and intergovernmental mobilization do not apply to regional governments

I argue that existing theories of interest group and intergovernmental mobilization are not fully applicable to regional governments. Both sets of theories assume that lobbying success depends on access to key resources—namely, money and legitimacy. However, regional governments have limited control over these key resources. The limited control over these resources distinguishes regional governments from other lobbying actors, such as business groups, which typically have greater access to these key resources.Footnote 4

Money is the resource that is implicitly assumed by existing theories of interest group mobilization. Arthur F. Bentley, widely regarded as the original proponent of the ‘group theory’, ‘viewed all politics […] as based on group actions seeking interests, with interest defined as economic interest’ (McFarland, Reference McFarland, Maisel, Berry and Edwards2010, 38; emphasis added; see Bentley, [1908] Reference Bentley1949). The strong Bentleyisian focus on economic preferences has strongly shaped the field. As a result, for much of its history, interest group and lobbying studies have concentrated on membership-based business groups and corporations (for an overview see de Figueiredo and Richter, Reference de Figueiredo and Kelleher Richter2014; Gilens and Page, Reference Gilens and Page2014).

This economic focus has often overlooked a key distinction: Business groups possess a unique advantage—money.Footnote 5 These groups command substantial financial resources, which scholars of interest groups and lobbying have consistently identified as a primary factor behind their disproportionate influence in policy-making. As Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960, 35) famously noted, ‘[…] the flaw in the pluralist heaven is that the heavenly chorus sings with a strong upper-class accent’, a critique that has been echoed across various political systems (e.g., Schlozman et al., Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012; Gilens and Page, Reference Gilens and Page2014; Aizenberg and Hanegraaff, Reference Aizenberg and Hanegraaff2020; De Bruycker and Colli, Reference De Bruycker and Colli2023; Persson and Sundell, Reference Persson and Sundell2024; Stevens and Willems, Reference Stevens and Willems2024).Footnote 6 The reason is straightforward: Financially privileged groups, including business associations, can leverage their resources to engage in lobbying activities under the principle that ‘more is better’ (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013, 47; see Potters and van Winden, Reference Potters and van Winden1992; Eising and Spohr, Reference Eising and Spohr2017).

As ‘greater money is linked to certain lobbying tactics and traits’ (McKay, Reference McKay2012, 908), affluent actors like business groups can amplify any lobbying success factor that helps them achieve their policy goals. Whether lobbying success is attained through a bigger and/or more diverse lobbying coalition (Klüver, Reference Klüver2013; Junk, Reference Junk2019; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2024), the use of many different lobbying tactics (e.g., De Bruycker and Beyers, Reference De Bruycker and Beyers2019), or more timely intervention (Crepaz et al., Reference Crepaz, Hanegraaff and Junk2023), subsequent theoretical approaches have consistently explained lobbying success through the lens of maximization.

However, maximization inherently requires substantial financial resources. Regional governments face significant limitations in mobilizing such resources. Unlike business groups, regional governments cannot harness the ‘power of the purse’, which is typically controlled by the more financially robust federal government (e.g., Watts, Reference Watts2008). This financial constraint makes it difficult for regional governments to compete using the prevalent ‘more is better’ approach to lobbying.

Previous intergovernmental mobilization theories, in turn, presuppose legitimacy as a resource. Legitimacy is often defined subjectively, meaning that something is ‘legitimate’ if it is ‘in accord with the norms, values, beliefs, practices, and procedures accepted by a group’ (Zelditch, Reference Zelditch, Jost and Major2001, 33). This concept closely ties to what organization theorists March and Olsen (Reference March and Olsen1984) describe ‘the logic of appropriateness’: According to this logic, actors within a polity behave in certain ways and adopt specific roles because they perceive them to be ‘right’, ‘appropriate’, or, ultimately, ‘legitimate’.

In a multi-level system, the expected actions, relationships, and roles of governments are often socially codified as well, varying by their status within the system. One key distinction arises between regional governments and local governments. Regional governments, as both the founders and sustainers of a multi-level system, hold a unique status. As classic federal theory holds, regional governments are the ‘[…] constituent parts of the national sovereignty, by allowing them a direct representation in the Senate’ (The Federalist Papers No. 9, [1787/88] Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Madison and Jay2008; emphasis added). Thus, when establishing a multi-level system, these formerly sovereign regional governments are compensated with constitutionally enshrined channels that provides them exclusive, legally protected access to the federal decision-making process, such as bicameralism (see Freiburghaus et al., Reference Freiburghaus, Arens and Mueller2021; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Chapman-Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair-Rosenfield2016; Benz, Reference Benz2018; Mueller, Reference Mueller2024b).

Following the ‘logic of appropriateness’, regional governments are expected to rely on these constitutionally enshrined channels to influence federal policy-making. For example, a second chamber—often symbolically referred to as ‘the regions’ voice’ (FreiburghausUA 2020, 972)—is widely regarded as the appropriate institutional mechanism for such influence. However, this prevailing sentiment presents a significant challenge for regional governments, as these formal channels have, in practice, largely lost their effectiveness (Freiburghaus, Reference Freiburghaus2024a; Mueller, Reference Mueller2024b).

Consider the case of bicameralism: In the early stages of many federations, including the US and Switzerland, members of second chambers were typically appointed and delegated directly by regional authorities. However, institutional changes have gradually transformed this selection-by-appointment method, altering the way territorial interests are represented at the federal level. Footnote 7,Footnote 8

In contrast, local governments—legal entities created by their respective regional governments (Payson, Reference Payson2022, 2)Footnote 9 —do not enjoy direct participation in federal decision-making. Such rights are exclusively reserved for regional governments (see Ladner et al., Reference Ladner, Keuffer, Baldersheim, Hlepas, Swianiewicz, Steyvers and Navarro2019). Following the ‘logic of appropriateness’, local governments are generally perceived as legitimate actors in informal lobbying precisely because they lack constitutionally guaranteed access to federal policy-making (see Goldstein and You, Reference Goldstein and You2017; Payson, Reference Payson2020a; Payson, Reference Payson2020b; Payson, Reference Payson2022; Zhang, Reference Zhang2022). As a result, existing theories on intergovernmental mobilization—primarily designed with local governments in mind—assume these actors possess the legitimacy to engage in informal lobbying. In contrast, regional governments cannot readily claim this resource of legitimacy.

Five distinct success conditions of intergovernmental lobbying

I propose a theoretical framework of intergovernmental lobbying success tailored specifically for regional governments, regardless of their financial or legitimacy resources. This framework identifies five distinct success conditions that, when aligned, enable a regional government to effectively shape federal policy in line with its preferences.

#1 Pressure – The importance of being urged to take action (PRESS): Policy-making ultimately revolves around addressing societal problems. However, as public policy scholars have established, defining what constitutes a societal problem is far from straightforward. Agenda-setting involves issue framing—shaping how societal problems are interpreted by elevating specific viewpoints over others (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993; Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2005; Cobb and Elder, Reference Cobb and Elder1972). As articulated by Peters (Reference Peters2018, 35), ‘a problem well put is half solved’. In a regional polity, various actors vie to influence these interpretations of what a societal problem is. For instance, local governments may urge their regional government to take action at the federal level (e.g., Einstein and Glick, Reference Einstein and Glick2017; Strickland, Reference Strickland2019; Payson, Reference Payson2020a; Payson, Reference Payson2020b; Payson, Reference Payson2022). In regions with a parliamentary system, such as Germany, the regional government often faces challenging questions from opposition parties (e.g., Zittel et al., Reference Zittel, Nyhuis and Baumann2019). Conversely, in presidential federal systems like Argentina or the US, members of parliament frequently co-sponsor bills (e.g., Fowler, Reference Fowler2006). In any case, all these advocacy activities pressurize the regional government to act vis-à-vis the federal level. And I expect pressure to translate into lobbying success eventually.

#2 Timing – The importance of moving early (TEMP): No matter how skilled a professional lobbyist may be, and regardless of the utility of the information they provide, if it is not delivered at the right time, it will ‘simply be ignored’Footnote 10 . The importance of the right timing of lobbying efforts is ‘quite substantial’ (Crepaz et al., Reference Crepaz, Hanegraaff and Junk2023, 549). Early movers possess an information advantage (e.g., Hall and Deardorff, Reference Hall and Deardorff2006), allowing them to secure access points and take the time to build trust, loyalty, and support among fellow actors (Holyoke, Reference Holyoke2009). To leverage this ‘first mover advantage’, regional governments must advocate for their interests during the initial stages of federal policy-making. These stages involve the exploration and negotiation of policy alternatives (Lasswell, Reference Lasswell1956). Since policy formulation often occurs behind closed doors within specialized federal agencies—which tend to follow a technocratic rather than purely partisan approach—less overtly political processes provide regional governments with greater opportunities to effectively voice their preferences.

#3 Coalition-building – The importance of joining forces strategically (COAL): Interest groups and lobbying scholarship has long recognized that ‘lobbying is a collective enterprise’ (Klüver, Reference Klüver2013, 59). Forming lobbying coalitions is one of the most prominent strategies employed by interest groups (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009, 180). Larger (e.g., Klüver, Reference Klüver2011) or more diverse (e.g., Junk, Reference Junk2019) coalitions are often more successful in signaling broad political support, which enhances their ability to shape policy outcomes.Footnote 11 However, regional governments have only limited control over the resources needed to pursue such a maximization strategy (as discussed in section 2.1). Rather than partnering with a wide range of interest groups from various societal and economic sectors, regional governments are compelled to strategically form ad hoc alliances with other regional governments. A coalition of several regional governments signals a consensus among the key actors who, in most multi-level systems, are responsible for implementing federal policies (e.g., Pressman and Wildavsky, Reference Pressman and Wildavsky1973). Strategic coalition-building therefore increases the likelihood that the federal government will take such coalitions seriously, as these regional governments possess the power to obstruct federal directives during the implementation phase if their concerns are ignored.

#4 Multi-channel lobbying – The importance of combining formal and informal channels (MULT): Depending on the issue at stake, decisions are made in different ‘policy venues’ (Baumgartner and Jones, 1993), each characterized by distinct rules, actors, and power dynamics. Lobbying actors must therefore adapt flexibly to the policy context, strategically ‘shop around’ for the most advantageous venue. The choice of appropriate lobbying strategies is crucial for success (e.g., Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Donas and Fraussen2015; Tatham, Reference Tatham2016; Huwyler et al., Reference Huwyler, Tatham and Blatter2018; De Bruycker and Beyers, Reference De Bruycker and Beyers2019). Regional governments-as-lobbyists possess a unique advantage: They can engage in multi-channel lobbying by combining constitutionally enshrined formal channels for influencing federal policy-making, such as bicameralism, with informal lobbying tactics. This strategic flexibility allows them to shape federal policy using a mix of insider-outsider lobbying tactics (Berry, Reference Berry1977) and of approaches that either ‘socialize’ or ‘privatize’ conflict (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960, 7).

#5 Information-sharing – The importance of sharing exclusive policy-relevant information (INFO): According to the influential ‘informational lobbying model’, lobbying revolves around the exchange of policy-relevant information with decision-makers (e.g., (Salisbury, Reference Salisbury1969; Schnakenberg, Reference Schnakenberg2017)). Interest groups, with their specialized focus, offer technical expertise crucial for developing informed policy solutions. This information serves as the ‘currency’ (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013, 39) they trade for access, making lobbyists more influential when they provide useful insights to politicians (McKay, Reference McKay2022, 9). However, given the multitude of advocates representing diverse interests like the environment or the economy, the information provided by individual interest groups often offers limited competitive advantage. In contrast, regional governments hold a unique resource: knowledge of what works on the ground (see Watts, Reference Watts2008). Because they are responsible for implementing federal policies, regional governments can foresee potential challenges and offer credible insights into effective policy implementation. By sharing this exclusive, practical information, regional governments enhance their influence over federal policy decisions, as the federal government seeks to avoid implementation failures (Pressman and Wildavsky, Reference Pressman and Wildavsky1973; Peters, Reference Peters2018; Sager and Hinterleitner, Reference Sager, Hinterleitner, Ladner and Sager2022).

Data and methods

My empirical analyses are based on a multi-year data collection effort that involved gathering, cleaning, and compiling data from the ‘legislative footprint’ of all 26 Swiss constituent units (named cantons). This full sample covers all federal policy decisions regarding the location of specific facilities (i.e. federal siting decisions).Footnote 12

For two specific reasons, Switzerland is a ‘typical case’ (Seawright and Gerring, Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) to test the proposed theoretical framework of intergovernmental lobbying success. First, in the Swiss federation, like in most federations globally, constitutionally protected channels for participation in federal decision-making have lost practical relevance, implying that regional governments need to adopt genuine lobbying tactics (e.g., Mueller, Reference Mueller2024b). Second, in Swiss politics, as elsewhere, ‘money is often the name of the game’ (Weschle, Reference Weschle2022, blurb), with a huge population of interest organizations competing for power forcing regional governments to lobby successfully in order to have an edge over moneyed interests (Mach and Eichenberger, Reference Mach, Eichenberger and Emmenegger2024).

I focus on siting decisions because they are unique in that they allow measuring lobbying success as ‘preference attainment’. Preference attainment is a major approach in the study of interest groups and lobbying, where ‘the outcomes of political processes are compared with the ideal points of actors’ (Dür, Reference Dür2008, 566; see Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2007; Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009; Bernhagen et al., Reference Bernhagen, Dür and Marshall2014; De Bruycker and Beyers, Reference De Bruycker and Beyers2019). However, in practice, there often exists a ‘gap’ between the intended or expected outcomes of a policy and its actual effects, which may unfold differently over time (see Peters, Reference Peters2018). Regional governments thus face considerable challenges in accurately ex ante assessing the potential impact of proposed policy initiatives, such as structural funds, on the regional economy, making it difficult for them to effectively articulate their preferences during the policy adoption phase.

In contrast, siting decisions offer a concrete issue where regional governments can conduct a relatively straightforward cost-benefit analysis in terms of the building zone it necessitates and the potential rewards in terms of e.g., additional jobs.Footnote 13 They are indeed the only federal policy-making processes where regional governments can express informed preferences before adoption. Furthermore, siting decisions create unambiguously identifiable ‘winning’ and ‘losing’ regional governments, thus enabling me to apply preference attainment measurement.

To match a given regional government’s preference to either host or not host a given facility with the federal authorities’ siting decision, I conducted extensive document analysis, screening official documents, archival records, and press statements for clearly articulated siting preferences and assessing whether they align with the federal policy outcome or not.Footnote 14 To cross-check the validity of my data collection, I conducted expert interviews on which I also drew to impute missing information.

In a similar vein, I proceeded with the dichotomous operationalization of the five success conditions (section 2.2). A detailed codebook including the coding rules and ‘anchor examples’ is provided in the online Appendix. The resulting new and original database is a truth table, i.e. a matrix with k columns, where k = 5 is the number of causal conditions, plus a column for the outcome

![]() $Y$

(

$Y$

(

![]() $SUCC$

) (‘1’ if the siting decision aligns with preference of the regional government

$SUCC$

) (‘1’ if the siting decision aligns with preference of the regional government

![]() ${x_i}$

; ‘0’ if not; see Table 1.

${x_i}$

; ‘0’ if not; see Table 1.

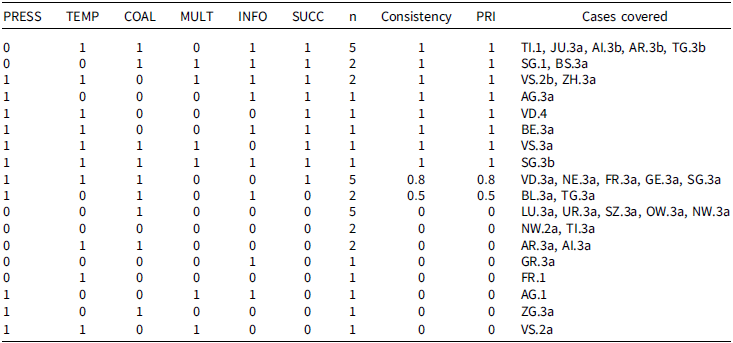

Table 1 Truth table (SUCC = 1)

Note: Following the ESA protocol, untenable assumptions as well as contradictory simplifying assumptions have been omitted (see section 3 for detailed information). PRESS = pressure; TEMP = timing; COAL = coalition-building; MULT = multi-channel lobbying; INFO = information-sharing; SUCC = intergovernmental lobbying success (outcome); n = number of cases represented by the same configuration of success factors; PRI = proportional reduction in inconsistency. The numbers behind the abbreviations of the cantons indicate the specific site decision: 1 = seat of the Federal Criminal Court and the Federal Administrative Court (created by the 2000 Swiss judicial reform); 2a = 2013 deployment concept of the Swiss Army; 2b = 2017 Sachplan Militär; 3a = network locations of the Swiss Innovation Park; 3b = further sites of the Swiss Innovation Park; 4 = location of federal asylum centers. Please refer to the online Appendix for further information on the cases examined.

Source: Freiburghaus (Reference Freiburghaus2024a), 537 with own adjustments.

Given the expectation that multiple success conditions need to converge to produce the outcome, it becomes necessary to employ methodological techniques that adequately account for the assumed ‘causal complexity’ (Ragin, Reference Ragin1987, 19) involved. Being part of a broader ever-thriving universe of ‘set-theoretic methods’ (e.g., Rohlfing and Schneider, Reference Rohlfing and Schneider2016; Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012; Schneider, Reference Schneider2024), Crisp-Set Qualitative-Comparative Analysis (csQCA) is among the most suitable tools to uncover the multiple causal pathways that can produce the outcome (conjunctural causation). The method also captures that a given outcome may have several mutually non-exclusive explanations (equifinality), and the non-occurrence of the outcome does not simply mirror the conditions that explain its occurrence (asymmetric causation; e.g., Ragin, Reference Ragin1987; Oana et al., Reference Oana, Schneider and Thomann2021; Schneider, Reference Schneider2024). Set-based explanations thus model a given outcome as complex causal configurations of necessary conditions without which the outcome cannot occur, and sufficient conditions, which are always present whenever the outcome is present.Footnote 15

To detect the multiple causal pathways that explain intergovernmental lobbying success, logical, or Boolean minimization of the truth table is applied. Following the most recent advances in computational set-theoretic methods, I implemented a new, fast, and particularly powerful minimization algorithm called ‘Consistency Cubes’ (CCubes), provided by the QCA package in R/RStudio (Duşa, 2023). To account for the challenges of ‘limited empirical diversity’ (Ragin, Reference Ragin1987, 104–13)Footnote 16 , my empirical analyses follow the state-of-the-art ‘Enhanced Standard Analysis’ protocol (ESA). The ESA protocol starts with the necessity analysis and then proceeds to the analysis of (configurations of) sufficient conditions, calculating three different solutions that each treat the aforementioned logical remainders differently. The ESA protocol also prevents ‘untenable assumptions’, i.e. assumptions that are ‘[…] logically contradictory or run counter to basic or uncontested knowledge’ (Oana et al., Reference Oana, Schneider and Thomann2021, 130).

For the subsequent interpretation, I draw on the parsimonious solution that has been recently found to be the correct and the most trusted one (Baumgartner and Thiem, Reference Baumgartner and Thiem2020). I ran a series of validity and robustness checks with the help of the SetMethods package (Oana et al., 2023; see online Appendix for further details).

Empirical results

Necessity analysis: no singular success condition

Is there a singular indispensable success condition without which a regional government cannot effectively shape federal policy-making in alignment with its preferences? In other words, what factor is always present when a regional government succeeds in prevailing over its competitors in a contested siting decision?

Table 2 provides a clear and unambiguous answer: There is no single necessary condition that consistently explains why a regional government secures its desired policy outcomes. All conditions fall well below the conventional consistency threshold of

![]() $ \ge 0.9$

.Footnote

17

Contrary to assumptions in interest group mobilization theories—largely developed for business groups—regional governments cannot rely on maximizing a single success condition due to resource constraints (section 2.1). The findings indicate that even if such maximization were feasible, it would not be sufficient to guarantee their policy success.

$ \ge 0.9$

.Footnote

17

Contrary to assumptions in interest group mobilization theories—largely developed for business groups—regional governments cannot rely on maximizing a single success condition due to resource constraints (section 2.1). The findings indicate that even if such maximization were feasible, it would not be sufficient to guarantee their policy success.

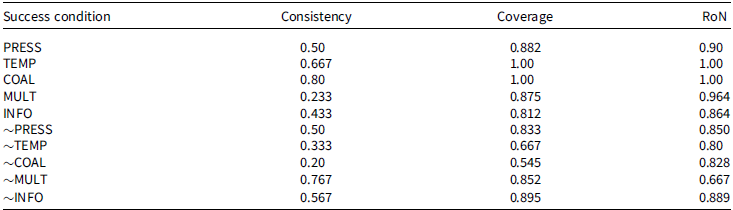

Table 2 Necessity analysis (SUCC = 1)

Note:

![]() $\sim $

= non-occurrence of the success condition. Consistency quantifies the percentage to which a success condition is necessary for the outcome, with a lower value of coverage indicating an empirically lesser relevant condition. Coverage expresses the empirical relevance of a success condition as the proportion of individual cases explained by a condition, relative to the total number of cases. RoN is a more conservative measure of empirical relevance (for further details see online Appendix).

$\sim $

= non-occurrence of the success condition. Consistency quantifies the percentage to which a success condition is necessary for the outcome, with a lower value of coverage indicating an empirically lesser relevant condition. Coverage expresses the empirical relevance of a success condition as the proportion of individual cases explained by a condition, relative to the total number of cases. RoN is a more conservative measure of empirical relevance (for further details see online Appendix).

Source: Freiburghaus (Reference Freiburghaus2024a, 557) with own adjustments.

Sufficiency analysis: five causal pathways to intergovernmental lobbying success

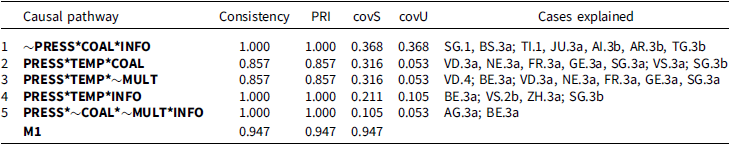

How do specific success conditions need to converge for a federal policy decision to align with a particular regional government’s preferences, given the absence of any singular indispensable condition? Table 3 identifies five distinct configurations of sufficient conditions that explain intergovernmental lobbying success. These configurations are alternative pathways, and their high coverage measures suggest they account for about 95 percent of the cases studied, indicating their strong explanatory relevance. In what follows, I will illustrate these five ‘winning formulae’ with concrete examples, demonstrating how regional governments successfully lobbied for the site allocations they sought within their territories.

Table 3 Five causal pathways to intergovernmental lobbying success (SUCC = 1)

Note:

![]() $\sim $

= non-occurrence of the success condition;

$\sim $

= non-occurrence of the success condition;

![]() ${\rm{*}}$

= logical AND;

${\rm{*}}$

= logical AND;

![]() $ + $

logical OR; PRI = proportional reduction in inconsistency; covS = raw coverage; covU = unique coverage (see online Appendix for further details). Reported is the parsimonious solution (please refer to the online Appendix where the other solutions that have been calculated according to the ESA protocol are documented). There is no ‘model ambiguity’, but only one causal model that can account for the configurational data (M1; see Baumgartner and Thiem, Reference Baumgartner and Thiem2015):

$ + $

logical OR; PRI = proportional reduction in inconsistency; covS = raw coverage; covU = unique coverage (see online Appendix for further details). Reported is the parsimonious solution (please refer to the online Appendix where the other solutions that have been calculated according to the ESA protocol are documented). There is no ‘model ambiguity’, but only one causal model that can account for the configurational data (M1; see Baumgartner and Thiem, Reference Baumgartner and Thiem2015):

![]() $\sim $

PRESS*COAL*INFO+PRESS*TEMP*COAL+PRESS*TEMP*

$\sim $

PRESS*COAL*INFO+PRESS*TEMP*COAL+PRESS*TEMP*

![]() $\sim $

MULT+PRESS*TEMP*INFO+PRESS*

$\sim $

MULT+PRESS*TEMP*INFO+PRESS*

![]() $\sim $

COAL*

$\sim $

COAL*

![]() $\sim $

MULT*INFO

$\sim $

MULT*INFO

![]() $ \Rightarrow $

SUCC. The numbers behind the abbreviations of the cantons indicate the specific site decision: 1 = seat of the Federal Criminal Court and the Federal Administrative Court (created by the 2000 Swiss judicial reform); 2a = 2013 deployment concept of the Swiss Army; 2b = 2017 Sachplan Militär; 3a = network locations of the Swiss Innovation Park; 3b = further sites of the Swiss Innovation Park; 4 = location of federal asylum centers. Please refer to the online Appendix for further information on the cases examined. A visualization of the five causal pathways can be found in the Fiss chart (see Table 4).

$ \Rightarrow $

SUCC. The numbers behind the abbreviations of the cantons indicate the specific site decision: 1 = seat of the Federal Criminal Court and the Federal Administrative Court (created by the 2000 Swiss judicial reform); 2a = 2013 deployment concept of the Swiss Army; 2b = 2017 Sachplan Militär; 3a = network locations of the Swiss Innovation Park; 3b = further sites of the Swiss Innovation Park; 4 = location of federal asylum centers. Please refer to the online Appendix for further information on the cases examined. A visualization of the five causal pathways can be found in the Fiss chart (see Table 4).

Source: Freiburghaus (Reference Freiburghaus2024a, 560) with own adjustments.

In the most frequently occurring causal pathway to intergovernmental lobbying success, the regional government is not pressured to act by any external actor, but builds on its own initiative a coalition with at least one fellow regional government, and actively shares its exclusive policy-relevant information with the federal authorities (

![]() $\sim $

PRESS*COAL*INFO). The cantons of Ticino and St. Gallen are cases in point. Both were eager to host the Federal Criminal Court and the Federal Administrative Court, respectively; i.e. the two new federal courts that have been created by the 2000 Swiss judicial reform (Flick Witzig et al., Reference Flick Witzig, Rothmayr Allison, Varone and Emmenegger2024). On their own free will, the Ticino and the St. Gallen cantonal governments took voluntary action, seeking alliances with other cantons, most notably with the canton of Zurich that is, by far, the most populous constituency and thus carries the biggest weight in federal parliamentary votes. At the same time, the two cantonal governments also tried to convince more reluctant federal-level MPs by providing them with well-tailored information such as sophisticated construction plans. These plans outlined how they intended to convert existing neighboring buildings within their territories into a ‘functional complex’, which could serve as a suitable location for the new federal courts in due time.

$\sim $

PRESS*COAL*INFO). The cantons of Ticino and St. Gallen are cases in point. Both were eager to host the Federal Criminal Court and the Federal Administrative Court, respectively; i.e. the two new federal courts that have been created by the 2000 Swiss judicial reform (Flick Witzig et al., Reference Flick Witzig, Rothmayr Allison, Varone and Emmenegger2024). On their own free will, the Ticino and the St. Gallen cantonal governments took voluntary action, seeking alliances with other cantons, most notably with the canton of Zurich that is, by far, the most populous constituency and thus carries the biggest weight in federal parliamentary votes. At the same time, the two cantonal governments also tried to convince more reluctant federal-level MPs by providing them with well-tailored information such as sophisticated construction plans. These plans outlined how they intended to convert existing neighboring buildings within their territories into a ‘functional complex’, which could serve as a suitable location for the new federal courts in due time.

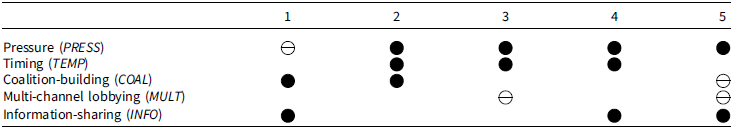

Table 4 Fiss chart: five causal pathways to intergovernmental lobbying success (SUCC = 1)

![]() Presence of the success condition

Presence of the success condition

![]() Absence of the success condition

Absence of the success condition

Source: Freiburghaus (Reference Freiburghaus2024a, 561) with own adjustments.

According to the second and also often occurring ‘winning formula’, the pressure to act, early interventions, and coalition-building lead to intergovernmental lobbying success (PRESS*TEMP*COAL). This is precisely how the cantons of Fribourg, Vaud, Valais, Neuchâtel, and Geneva proceeded in the early 2010s. For decades, they have harbored aspirations to become ‘cités de l’innovation et du savoir’, a vision being repeatedly affirmed by both ambitious regional-level MPs and local government officials. The governments of those five French-speaking cantons were thus forced to start exploring collaboration opportunities early for they realized that, as a linguistic minority in a predominantly German-speaking country, they would just be outvoted if they lobbied each individually. And, indeed: They agreed on an intercantonal coalition well before the federal authorities were to officially communicate the details of the siting process, paving the way to success (SBFI, 2023).

Just as frequently, a third causal pathway can be observed. This combination of sufficient conditions is characterized by third actors exerting pressure on the regional government, and the regional government making efforts to take early advocacy action. However, simultaneously, the regional government (intentionally) avoids exploiting multiple access points (PRESS*TEMP*

![]() $\sim $

MULT). Such is exemplified by the canton of Vaud’s efforts during the search for federal asylum centers. Migration has long been a recurrent and polarizing issue in Vaud politics because of certain small towns having been early hosts of refugee homes. In the aftermath of the 2015 migration crisis, and heightened tensions between communities, some local government members thus expressed concerns that ‘it’s too much’Footnote

18

. They pressured their cantonal government to intervene early and negotiate a favorable deal. Instead of employing various lobbying tactics, the Vaud government deliberately focused on a particular channel—direct and informal engagement with the responsible federal bureaucracy agencies—and, thus, secured a major concession (EFK, 2022): The federal asylum center situated in the canton of Vaud will exclusively accommodate asylum-seekers under the UNHCR ‘Resettlement program’Footnote

19

, as they were considered to have a higher likelihood of successful integration.

$\sim $

MULT). Such is exemplified by the canton of Vaud’s efforts during the search for federal asylum centers. Migration has long been a recurrent and polarizing issue in Vaud politics because of certain small towns having been early hosts of refugee homes. In the aftermath of the 2015 migration crisis, and heightened tensions between communities, some local government members thus expressed concerns that ‘it’s too much’Footnote

18

. They pressured their cantonal government to intervene early and negotiate a favorable deal. Instead of employing various lobbying tactics, the Vaud government deliberately focused on a particular channel—direct and informal engagement with the responsible federal bureaucracy agencies—and, thus, secured a major concession (EFK, 2022): The federal asylum center situated in the canton of Vaud will exclusively accommodate asylum-seekers under the UNHCR ‘Resettlement program’Footnote

19

, as they were considered to have a higher likelihood of successful integration.

In the fourth causal pathway, intergovernmental lobbying success is achieved by the co-occurrence of pressure to act, early intervention, and information-sharing (PRESS*TEMP*INFO). Here, the canton of Valais during the formulation of the 2013 deployment concept of the Swiss Army serves as a telling illustration. Regional-level MPs in Valais strongly opposed the federal government’s decision to shut down the Sion air base, located in the canton’s capital city. As the Sion air base has always been a major employer, they thus submitted almost two dozen parliamentary bills, each pushing the regional government to take prompt advocacy action (Canton du Valais, 2024). Simultaneously, the regional government convened a working group which was to elaborate proposals how the operation of the Sion air base could become more cost-effective and profitable—and these proposals were actively shared with the federal authorities who in turn overturned their initial closure decision.

Lastly, there is a fifth explanation for why a particular regional government manages to shape federal policy-making processes in alignment with its preferences (a causal path that, in practice, occurs rather seldom, though): The regional government is put under pressure and willingly shares its exclusive policy-relevant information with the federal government but, at the same time, refrains from both coalition-building and multi-channel lobbying (PRESS*

![]() $\sim $

COAL*

$\sim $

COAL*

![]() $\sim $

MULT*INFO). Here, I shall point at the canton of Berne when the federation tried to allocate sites for the ‘Swiss Innovation Park’, beginning in 2014. The local government of Biel/Bienne—the second largest Bernese city which has long been notorious to be home to the less fortunate (BFS, 2023)—thus pressurized the regional government, e.g., by transmitting the findings of a commissioned study that meticulously calculated how such an innovation hub would offer an important stimulus for the regional economy. Instead of joining forces with fellow regional governments and/or employing a wide array of lobbying tactics, the pressurized Bernese government empowered one of its seven cabinet members with a clear mandate to lobby the small circle of the responsible federal decision-makers confidentially, and successfully.

$\sim $

MULT*INFO). Here, I shall point at the canton of Berne when the federation tried to allocate sites for the ‘Swiss Innovation Park’, beginning in 2014. The local government of Biel/Bienne—the second largest Bernese city which has long been notorious to be home to the less fortunate (BFS, 2023)—thus pressurized the regional government, e.g., by transmitting the findings of a commissioned study that meticulously calculated how such an innovation hub would offer an important stimulus for the regional economy. Instead of joining forces with fellow regional governments and/or employing a wide array of lobbying tactics, the pressurized Bernese government empowered one of its seven cabinet members with a clear mandate to lobby the small circle of the responsible federal decision-makers confidentially, and successfully.

While, in this paper, I endeavored to explain intergovernmental lobbying success, knowing why regional governments lose in federal policy-making processes also bears high practical relevance. (To reiterate, please remember that due to asymmetric causality the causal pathways I have just presented cannot simply be mirrored to deduce ‘what does not work’.) For reasons of brevity, I leave it with the empirically most frequently occurring explanation of intergovernmental lobbying failure, that is a configuration of a non-pressurized regional government, no multi-channel lobbying, and no proactive information-sharing (

![]() $\sim $

PRESS*

$\sim $

PRESS*

![]() $\sim $

MULT*

$\sim $

MULT*

![]() $\sim $

INFO).Footnote

20

This occurs whenever a particular regional government is too confident, expecting to carry off its ‘siting decision win’ for sure. For example, the government of Fribourg mainly sat back as soon as the federal government suggested, in its dispatch to the federal parliament, that the capital city of Fribourg should host the newly created Federal Administrative Court. Hence, no third actor deemed it necessary to put pressure on the regional government, and hardly any advocacy action was taken, let alone the exploitation of multiple access points. And while the victorious government of St. Gallen even submitted plans how they intend to support the newly-settled federal judges in moving to the city of St. Gallen (e.g., language schools), the government of Fribourg even failed to outline possible buildings that could host the Federal Administrative Court (BBl 2001 605).

$\sim $

INFO).Footnote

20

This occurs whenever a particular regional government is too confident, expecting to carry off its ‘siting decision win’ for sure. For example, the government of Fribourg mainly sat back as soon as the federal government suggested, in its dispatch to the federal parliament, that the capital city of Fribourg should host the newly created Federal Administrative Court. Hence, no third actor deemed it necessary to put pressure on the regional government, and hardly any advocacy action was taken, let alone the exploitation of multiple access points. And while the victorious government of St. Gallen even submitted plans how they intend to support the newly-settled federal judges in moving to the city of St. Gallen (e.g., language schools), the government of Fribourg even failed to outline possible buildings that could host the Federal Administrative Court (BBl 2001 605).

Conclusion

Nowadays, regional governments are among ‘the most profilic but understudied’ (Payson, Reference Payson2020b, 689) lobbyists, spending million in taxpayer money on advocacy tactics traditionally associated, in a clichéd view, with moneyed and organized interests. Despite the ubiquitous phenomenon of intergovernmental lobbying, the critical question that has guided the study of interest group politics—‘who wins, who loses—and why?’ (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009, subtitle)—has not yet been explicitly addressed in the context of regional governments.

A major reason for the lack of empirical analysis of intergovernmental lobbying success is the absence of suitable theoretical frameworks. Existing classical theories of interest group advocacy, which focus on membership-based and business-leaning groups (e.g., de Figueiredo and Richter, Reference de Figueiredo and Kelleher Richter2014; Gilens and Page, Reference Gilens and Page2014), and existing theories of intergovernmental mobilization (e.g., Callanan and Tatham, Reference Callanan and Tatham2014; Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Donas and Fraussen2015; Tatham, Reference Tatham2016; Goldstein and You, Reference Goldstein and You2017; Strickland, Reference Strickland2019; Payson, Reference Payson2020a; Payson, Reference Payson2020b; Payson, Reference Payson2022; Zhang, Reference Zhang2022), are not equipped to explain why regional governments succeed in shaping federal policy to their advantage. Both sets of theories assume the availability of key resources—money and legitimacy—over which regional governments have only limited control (see Freiburghaus, Reference Freiburghaus2024a).

In this article, I introduced a theoretical framework of intergovernmental lobbying success specifically tailored to regional governments. The framework centers around five distinct success conditions—pressure, timing, coalition-building, multi-channel lobbying, and information-sharing. The convergence of these success conditions provides a compelling explanation for why some regional governments ‘get what they want’, while others do not. According to my argument, these success conditions are crucial to understanding how regional governments can influence federal policy in their favor.

Drawing on state-of-the-art set-theoretic methods (csQCA) and examining the ‘typical case’ of Switzerland, I demonstrated that no single necessary success condition guarantees that a federal policy decision will align with a particular regional government’s preferences. In other words, there is no single indispensable factor that regional governments must simply ‘maximize’ to ensure they are heard by the federal level. Instead, five distinct configurations of sufficient conditions were identified, each offering an alternative explanation for intergovernmental lobbying success.

In the most frequently observed causal pathway to intergovernmental lobbying success, a regional government acts independently—free from external pressure (e.g., from MPs or local governments)—forms a coalition with at least one other regional government, and proactively provides exclusive policy-relevant information to federal authorities. These empirical findings underscore the potential to integrate previously separate areas and fields of comparative politics, multi-level governance, public policy, federalism, and interest group and lobbying studies. Both vested interests and governments-as-lobbyists can be understood using common concepts such as lobbying tactics, as long as the resource constraints of regional governments are acknowledged.

This study is the first to specifically focus on the successful advocacy of regional governments, thereby advancing our understanding of intergovernmental lobbying. However, several promising avenues for future research remain. First, empirical analyses could and should be extended to other multi-level systems as well as to other types of federal policy decisions, or else from siting decisions, and triangulating different measurements of interest group influence (e.g., Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2007; D ür, 2008; Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009; Bernhagen et al., Reference Bernhagen, Dür and Marshall2014). The study’s theoretically grounded success conditions—derived from various fields—, combined with its configurational explanations rather than idiosyncratic ones, suggest that these findings could be relevant in other multi-level systems. Nonetheless, context-specific factors must be carefully considered in future cross-country comparisons, where researchers must balance the notorious trade-off between ‘maximizing the empirical scope’ and ‘maximizing measurement validity’.

A second promising avenue for future research concerns the broader effects of intergovernmental lobbying beyond single federal policy outcomes. Intergovernmental lobbying has far-reaching implications for democratic representation, regional inequality, and unequal policy responsiveness. As such, intergovernmental lobbying ties into fundamental questions of democratic theory and practice: ‘who governs?’ (Dahl, Reference Dahl1961, title; see Truman, Reference Truman1951; Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Persson and Sundell, Reference Persson and Sundell2024). This study notably shows that lobbying success is not exclusive to the most populous, powerful, or wealthiest regional governments.Footnote 21 However, further investigation is needed to determine whether, across all federal policy decisions, wealthier regional governments are disproportionately able to ‘[…] to translate their economic advantage into political power’ (Payson, Reference Payson2022, 106), similar to the way cities-as-lobbyists do in the US (see Payson, Reference Payson2020a; Payson and Freiburghaus, Reference Payson, Freiburghaus and Chari2025). Just as research on major interest group and lobbying dynamics has consistently shown, it is worth exploring whether there is a systematic bias in intergovernmental lobbying success favoring regional governments with particular attributes. This potential bias could exacerbate regional inequalities such as unequal access to public services within multi-level systems, potentially contributing to rising political discontent, growing rural resentment, or citizen alienation (see Beramendi, Reference Beramendi2012; Ejrn æ s et al., Reference Ejrnæs, Jensen, Schraff and Vasilopoulou2024; Cremaschi et al., Reference Cremaschi, Rettl, Cappellut and De Vries2024; Schraff and Pontusson, Reference Schraff and Pontusson2024).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773925100088.