1. Introduction

1.1. Metacognition: definition and other related concepts

A recent definition of metacognition emphasizes the inclusion of a wide range of activities. These activities range from those that are discrete, in which a person creates an idea about a specific thought or emotion, to those that are more synthetic, in which a person forms these distinct thoughts into complex representations of oneself or others [Reference Lysaker and Dimaggio1]. For example, in discrete activities a person can recognize and distinguish between cognition (i.e., remembering, imagining, dreaming, desiring) and emotion (i.e., anger, happiness, surprise, embarrassment, guilt), regarding oneself and others (e.g., “I remembered my mother was troubled yesterday”). In synthetic activities, a person can weave together the complex interplay of affect, thought and action to generate a story based on past and present information (e.g., “I think my mother was quiet yesterday because she was troubled by what my brother had done in school. She always gets quiet when she's worried”). Metacognitive abilities are those abilities that enable individuals to perform ongoing constructions of integrative and holistic representations of the self and others, which are needed in order to cope with daily challenges [Reference Lysaker, Vohs and Ballard2,Reference Lysaker and Hasson-Ohayon3]. Similar constructs such as social cognition and theory of mind are also widely addressed in the literature, but while likenesses between these constructs [Reference Pinkham, Penn and Green4,Reference Green and Leitman5] have been noted, social cognition and metacognition refer to distinct sets of abilities [Reference Lysaker and Dimaggio1,Reference Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan-Msika and Mashiach-Eizenberg6,Reference Vohs, Lysaker and Francis7]. Social cognition refers to the particular ability of assessing and judging specific situations, whereas metacognition emphasizes the synthetic ability to create complex and integrated representations of the self and others [Reference Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan-Msika and Mashiach-Eizenberg6]. The current study focuses on the construct of metacognition in accordance with the Lysaker and Dimaggio [Reference Lysaker and Dimaggio1] definition of metacognition, as described above.

Studies that have relied on the above definition, have encoded metacognitive abilities via the use of the Metacognition Assessment Scale (MAS), or its abbreviated version (MAS-A). This scale attempts to capture the different aspects of metacognition. Encoding is done by quantifying the frequency and level of detail in spontaneous speech with regard to the person's thoughts and feelings about the self and others. It is a scale that is therefore suitable for use with different types of transcripts, for instance those of psychotherapeutic sessions [Reference Lysaker, Leonhardt and Pijnenborg8,Reference Semerari, Carcione and Dimaggio9], as well as with semi-structured interviews, such as the Indiana Psychiatry Illness Interview (IPII) [Reference Lysaker, Clements and Plascak-Hallberg10]. The MAS-A includes four subscales: self-reflectivity (i.e., the capacity to form increasingly complex representations of oneself); understanding others’ minds (i.e., the ability to form increasingly complex representations of other people); decentration (i.e., the ability to take a non-egocentric view of the mind of others and recognize that others’ mental states are influenced by a range of factors); and mastery, (i.e., the ability to respond to and cope with psychological problems using increasingly complex metacognitive knowledge) [Reference Lysaker, Leonhardt and Pijnenborg8].

1.2. Metacognition deficits among people with schizophrenia

There is extensive literature on metacognitive impairments among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders [Reference Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan-Msika and Mashiach-Eizenberg6,Reference Lysaker, Buck, Leonhardt, Buck, Hamm, Hasson-Ohayon, Lysaker, Dimaggio and Brune11], expressed in the difficulties they have in reflecting on their own and others’ mental activities and in thinking about their own specific psychological problems [12–Reference Penn, Corrigan, Bentall, Racenstein and Newman14]. While these deficits are described as being stable over time and are assumed to be trait-like, the degree to which they are experienced depends on the cognitive and emotional demands of the situation [Reference Semerari, Carcione and Dimaggio9,Reference Dimaggio, Procacci and Nicolo15]. In complex situations, a person needs to be able to flexibly move between representations of oneself and others. The demands are greater when one must inhibit thoughts about his/her own mental state, so as to make room for recognizing other people's mental states and to distinguish other people's perspectives from one's own [Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio, Buck, Carcione and Nicolò16]. Moreover, in ambiguous situations, deficits in metacognitive abilities may cause people to simply give up. When people lack the ability to reason through their thoughts and feelings, they tend to jump to conclusions, i.e., arrive at decisions relatively quickly or in the presence of little data [Reference Buck, Warman, Huddy and Lysaker17].

Since deficits in metacognition are considered one of the major causes of the difficulties experienced by people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, researchers have explored the links between these abilities and varied outcome measures, mainly symptoms and psychosocial functioning. Regarding the former – i.e., symptoms – studies that have explored these links have focused on the unique symptoms among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: i.e., positive symptoms, which refer to an excess or distortion in normal functioning; negative symptoms, which include lack of affect; emotional discomfort, which includes anxiety, depression, active social avoidance and guilt; cognitive symptoms, which include speech that evidences loose connections between ideas; and disorganized symptoms, which include disorganized speech or behavior.

To explore the link between deficits in metacognitive abilities and these symptoms, studies have often used the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [Reference Kay, Flszbein and Opfer18] and have found associations between poorer metacognitive abilities in all of the MAS-A subscales and symptomatic distress. For example, the MAS-A subscale of “understanding others’ minds” was related negatively with negative symptoms [Reference MacBeth, Gumley and Schwannauer19], disorganized symptoms [Reference Vohs, Lysaker and Francis7], positive symptoms [Reference Rabin, Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan, Rozencwaig, Shalev and Kravetz20] and emotional withdrawal [Reference Lysaker, Carcione and Dimaggio21]. The self-reflectivity subscale was negatively associated with disorganized symptoms [Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio, Buck, Carcione and Nicolò16,Reference Fridberg, Brenner and Lysaker22] and mastery and decentration were negatively associated with negative symptoms [Reference Nicolo, Dimaggio and Popolo23,Reference McLeod, Gumley, MacBeth, Schwannauer and Lysaker24].

Metacognitive deficits were also found to be associated with psychosocial functioning measures, independent from symptoms. These functions affect patients’ quality of life and include measures of social functioning [Reference Penn, Corrigan, Bentall, Racenstein and Newman14,Reference Lysaker, Roe and Yanos25,Reference Roberts and Penn26], vocational functioning [Reference Lysaker, Bell and Milstein27] and self-care [Reference Brüne, Schaub and Juckel28]. For example, a higher degree of self-reflectivity was associated with accurate appraisals of work behavior [Reference Luedtke, Kukla, Renard, Dimaggio, Buck and Lysaker29] and better work performance [Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio and Carcione30]. Mastery was found to be associated with the capacity for emotional investment [Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio, Buck, Carcione and Nicolò16] and social quality of life [Reference Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan-Msika and Mashiach-Eizenberg6,Reference Rabin, Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan, Rozencwaig, Shalev and Kravetz20]. Metacognitive deficits were also linked to impaired social and vocational functions [Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio and Carcione30,Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio and Daroyanni31], and social alienation, as such deficits seem to make it difficult for the individual to form social bonds or seek support from others [Reference Lysaker, Shea and Buck32,Reference Roe and Davidson33].

The role of metacognitive abilities has been assessed in different studies among clinical and non-clinical populations [Reference Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan-Msika and Mashiach-Eizenberg6,Reference Lysaker, Buck, Leonhardt, Buck, Hamm, Hasson-Ohayon, Lysaker, Dimaggio and Brune11,Reference Rabin, Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan, Rozencwaig, Shalev and Kravetz20,34–Reference Tas, Brown, Esen-Danaci, Lysaker and Brüne36]. In these studies, the researchers found that clients with different psychiatric diagnoses experienced different levels of metacognitive deficits, a variance that was also found in a non-clinical population [Reference Rabin, Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan, Rozencwaig, Shalev and Kravetz20]. Among people with schizophrenia, these abilities were significantly lower than in non-clinical populations [Reference Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan-Msika and Mashiach-Eizenberg6]. As such, given the potential effect of these deficits on both the individual's experience of his/her self and on his/her development and maintenance of interpersonal relationships [Reference Lysaker, Carcione and Dimaggio21,Reference Harrington, Langdon, Siegert and McClure37,Reference Langdon, Coltheart, Ward and Catts38], metacognitive deficits among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders are of particular clinical and theoretical interest. Although many studies have already revealed the link between these deficits and outcome measures among this population, to our knowledge, no meta-analysis on this topic has yet been published.

The current study therefore provides a meta-analysis of studies that used the MAS-A in order to assess the associations between metacognition and outcomes among persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Although different operational definitions of metacognition exist, we chose to focus on the MAS-A, as it represents the most comprehensive and updated definition of metacognition, whose reliability and validity have been consistently reported [1–Reference Lysaker and Hasson-Ohayon3]. In recent years, over 115 studies have used this measure, 33 of which were published in 2015–2016, indicating the high degree of its continued relevance. Also, in conducting such an analysis, it seems important to differentiate between studies that have assessed illness symptomatology and studies that have assessed psychosocial functioning outcomes. Measure type – i.e., global symptomatology as opposed to psychosocial functioning – refers to different outcome domains and therefore needs to be addressed. Accordingly, the goals of the current meta-analysis were to:

summarize the direction and magnitude of the relationship between metacognitive abilities and outcome measures among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders;

determine whether measure type (symptoms versus psychosocial functioning outcomes) acts as a moderator.

2. Method

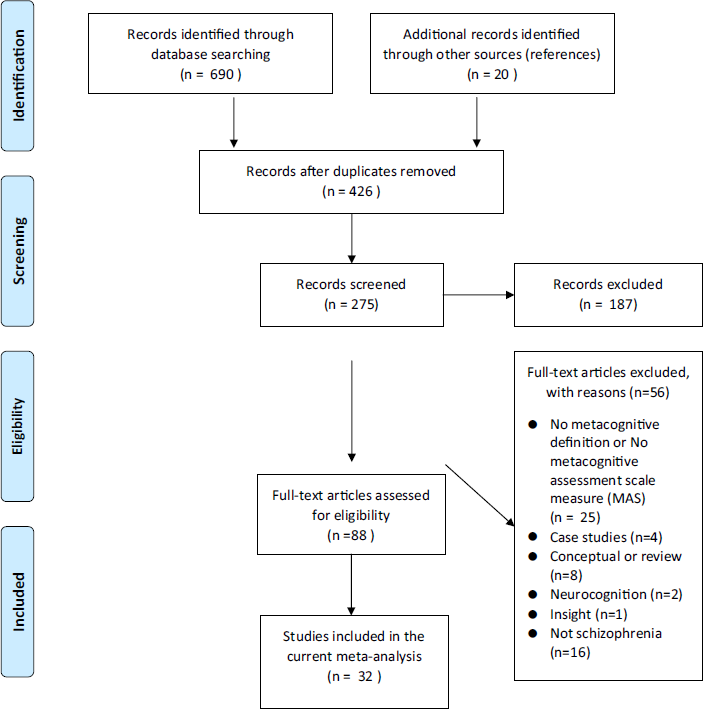

In order to maintain a high level of meta-analytic quality, we used the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist and literature flow chart as methodological standards and reporting guidelines [Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Grp39].

2.1. Literature Search

We conducted the literature search using Google Scholar, Medline and PsycNET and looked at all relevant studies that had been published prior to August 31, 2016. Keywords were “metacognition” and “schizophrenia” paired with “symptoms” and “outcome measures” for studies published in English at any time prior to the search date. We conducted an initial screening by examining titles to eliminate studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. Next, we examined the abstracts of all remaining articles and if an article appeared likely to meet the inclusion criteria, we obtained the full text. This process enabled the identification of 32 studies. We included only peer-reviewed, published studies, as they are likely to be of higher quality.

2.2. Study selection: inclusion & exclusion criteria

In order to be included in the meta-analysis, studies were required to include patient groups with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder or a first-time psychotic episode. Case studies were not included. In these studies, metacognitive abilities had to be encoded via use of the Metacognitive Assessment Scale (MAS) [Reference Semerari, Carcione and Dimaggio9] or its abbreviated version (MAS-A) [Reference Lysaker, Carcione and Dimaggio21]. Only one study used the Metacognition Assessment Scale-Revised version (MAS-R) [Reference MacBeth, Gumley and Schwannauer19]. Seventeen studies using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [Reference Kay, Flszbein and Opfer18] and 15 studies with psychosocial functioning measures were included. Symptoms included PANSS items and factors: positive, negative, disorganized and emotional discomfort [Reference Bell, Lysaker and Beam-Goulet40]. Psychosocial functioning measures included social and vocational functioning measures. These measures included: work performance measures [Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio and Carcione30,Reference Lysaker, Erickson and Ringer41,Reference Lysaker, McCormick and Snethen42], quality of life measures [Reference Lysaker, Carcione and Dimaggio21,Reference Lysaker, Shea and Buck32,Reference Luther, Firmin and Minor43], global assessment of functionings [Reference Bo, Abu-Akel, Kongerslev, Haahr and Bateman44,Reference Abu-Akel, Heinke, Gillespie, Mitchell and Bo45] and interpersonal relationship measures [Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio and Daroyanni31,Reference Davis, Eicher and Lysaker46]. We did not include studies that explored the link between metacognitive abilities and other measures (e.g., neurocognition) or studies that explored concepts related to metacognition (e.g., theory of mind, mentalization, social cognition).

2.3. Coding

We coded variables from each sample using a codebook that we developed on the basis of suggestions from Lipsey and Wilsons [Reference Lipsey and Wilson47] and Cards [Reference Card48]. Data were extracted from papers and coded by the first author. A random subsample of papers was coded independently by the third author. Inter-rater reliability was 100%.

2.4. Sample-level information

We included sample-level information regarding year, authors, measures, sample size, and diagnosis type (i.e., schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder or first-time psychotic episode).

2.5. Effect size

For each study, we collected correlations of the symptoms or psychosocial functioning measures for the clinical group only, which included patient groups with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder or first-time psychotic episode. We used these values to calculate Cohen's d. Given the rich data in each study, when a study reported multiple effect sizes – i.e., multiple correlations between MAS-A subscales and outcome measures – we chose for the analysis of the association between metacognitive abilities and outcome measures the highest correlation to represent the study. For the heterogeneity analyses of symptoms/psychosocial functioning measures with MAS-A subscales, as well as the heterogeneity analyses for PANSS factors with MAS-A, when a study reported multiple effect sizes – i.e., multiple correlations between the examined subscale and outcome measures – we again chose the highest correlation to represent the study. All data for which we calculated effect sizes were coded into Microsoft Excel in formulas that were programmed on the basis of Hunter & Schmidts [Reference Hunter and Schmidt49].

2.6. Analyses

We produced a forest plot of the effect size point estimates, allowing for an examination of how much each study impacted the overall effect size. Presence of bias was assessed in two ways. First, we plotted studies’ effect sizes against their sample size, creating a funnel plot. Second, we visually examined funnel plots for asymmetry, which can indicate the presence of publication bias [Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein50].

2.7. Main analyses

The standardized mean difference was calculated as Cohen's d. Effect sizes ≤ .20 were considered small; effect sizes of .50 were considered medium; and effect sizes ≥ .80 were considered large. Effect sizes at the study level were weighted by sample size. All meta-analytic calculations were conducted using Microsoft Excel, in formulas that were programmed on the basis of Hunter & Schmidts [Reference Hunter and Schmidt49].

2.8. Heterogeneity and moderator analyses

Heterogeneity is a concern in meta-analysis as it may introduce the problem of “comparing apples with oranges”. Heterogeneity was tested with a χ 2 test. We also reported the I 2 statistic. When I 2 = 0%, 25%, 50% or 75%, then no, low, moderate or high heterogeneity, respectively, must be assumed [Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman51].

We examined the Q-statistic to assess the presence of heterogeneities [Reference Card48]. We conducted moderator analyses when Q was significant, a common cut-off point for moderation analyses [Reference Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez and Botella52]. We then calculated effect sizes for each group and compared them to the total effect, and Q and I 2 were evaluated at the level of the potential moderator. We considered potential categorical moderators to significantly moderate the total effect when subgroup effect sizes differed, confidence interval ranges and I 2 values were reduced, and Q-between was significant [Reference Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez and Botella52].

3. Results

3.1. Study selection & characteristics

Fig. 1 displays the article identification and inclusion, while Table 1 includes detailed study characteristics at the individual study level. Thirty-two studies met inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis, for a total of n = 1995.

Fig. 1 PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1 Studies included in meta-analysis.

3.2. Sensitivity analyses & publication bias

Visual examination of the funnel plot and forest plot revealed heterogeneous effect sizes. All studies were retained for analyses. Trim and fill analyses indicated no change in the effect size after looking for extreme values, suggesting that results were robust against publication bias.

3.3. Main analyses

Results indicated a negative, small effect size for the association between metacognitive abilities and outcome measures (k = 32, Cohen's d = −.12, 95% CI .−1.92 to 1.7). Heterogeneity analyses produced a significant Q-statistic (Q = 445.84) and a high amount of heterogeneity indicated by the I 2 statistic (93.04%), suggesting that moderator analyses were appropriate. Fig. 2 presents the forest plot of meta-analytic results.

Fig. 2 Forest plot of studies included in the meta-analysis.

3.4. Moderator analyses

Seventeen studies included symptoms as an outcome measure, while the rest (k = 15) used varied outcome measures (e.g., social quality of life, work performance). We assumed that measure type (symptom measures and psychosocial functioning measures), could be a moderator that would sub-divide the studies’ effect size into two homogenous groups. We then split effect sizes into two groups: those with symptom measures and those with psychosocial functioning as outcome measures. For both measures, the heterogeneity analysis revealed a non-significant Q, indicating a homogenous effect size. For symptoms as outcome measure, the result was: Q = 19.87, I 2 = 0%, d = −1.07 (95% CI −1.18 to −.75). For psychosocial functioning as outcome measure, the result was: Q = 9.81, I 2 = 19.47%, d = .94 (95% CI .58 to 1.2).

Further analysis examined the heterogeneity for each of the MAS-A subscales, as well as PANSS factors. As detailed in Table 2, this analysis revealed homogenous effect sizes for PANSS factors. For MAS-A subscales, the analysis revealed homogenous effect sizes for all MAS-A subscales with functioning measures and for all MAS-A subscales except the “other” subscale with symptom measures (see Table 3). After excluding the study of Minors [Reference Minor and Lysaker53], which was the only study that found a correlation with the PANSS factor “reality distortion”, a homogenous effect was revealed (d = −.85, Q = 4.79, I 2 = 0%).

Table 2 Heterogeneity analyses for PANSS factors with MAS-A.

Table 3 Heterogeneity analyses for symptoms and psychosocial functioning measures with MAS-A subscales.

4. Discussion

The present meta-analysis included a total of 32 studies, which assessed the associations between metacognitive abilities, as defined and assessed by the MAS, and outcome measures of symptoms and psychosocial functioning. This is the first meta-analysis to synthesize the literature regarding these links among people diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Analyzed together, measures that assess symptoms and measures that assess psychosocial functioning were found highly heterogeneous. A moderator analysis revealed two homogenous groups, according to measure type. In other words, metacognitive abilities among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders were associated negatively with levels of symptoms and positively with psychosocial functioning measures. These associations were found in all of the metacognitive subscales.

We were also interested in the associations between each of the MAS-A subscales, as well as the PANSS factors, and our analyses found strong negative associations between metacognitive abilities and symptom severity, as reflected in all of the MAS subscales and PANSS factors. These results were found in all of the PANSS factors except for “reality distortion”, which assesses delusions, hallucinations and unusual thought content.

Several accounts offer possible explanations for the negative association between symptoms and metacognitive abilities and the influence this negative association has on social quality of life. Friths [Reference Frith13] suggests that symptoms of schizophrenia mediate the association between metacognitive abilities and social quality of life. This mediation model is viewed as opposing the intuitive perception that suggests that symptoms of schizophrenia influence metacognitive deficits and that these deficits, in turn, affect social quality of life. One study examined these competing models and the reported results support the first models [Reference Rabin, Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan, Rozencwaig, Shalev and Kravetz20]. Consequently, it was found that among people diagnosed with schizophrenia, negative symptoms mediated the association between understanding others’ minds and social quality of life [Reference Rabin, Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan, Rozencwaig, Shalev and Kravetz20].

Evolutionary and developmental perspectives provide another possible explanation for the association between symptoms, metacognitive abilities and psychosocial functioning. These perspectives have also supported the distinction between psychosocial functioning and symptoms in their association with metacognitive abilities and suggest that deficits in metacognitive abilities impact psychosocial functioning. In turn, this association affects the symptomatology of schizophrenia. It may be that metacognitive ability helps individuals adjust their social behaviors [Reference Suddendorf and Whiten54,Reference Brüne55]. Among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, therefore, deficits in metacognitive abilities may negatively impact interpersonal relationships, resulting in an increased symptomatology that may be expressed by a tendency to withdraw [Reference Salvatore, Dimaggio, Popolo and Lysaker56].

With regard to the positive association between metacognition and psychosocial functioning, a recent study suggested that this association was independent of symptoms [Reference James, Hasson-Ohayon and Vohs57]. In other words, the study indicated that metacognitive abilities moderated the association between dysfunctional self-appraisal and social functioning: a relationship that persisted after controlling for severity of psychopathology and levels of positive and negative symptoms [Reference James, Hasson-Ohayon and Vohs57]. Thus, in line with the results of this meta-analysis (showing type of measure as a moderator), the abovementioned recent study further supports the need to differentiate between symptoms and psychosocial functioning as correlates of metacognition.

Though our findings are in accord with the majority of studies, some results diverge from our main findings. First, as noted above, we also examined the association between the MAS-A subscales PANSS factors and found negative associations. Metacognitive abilities among individuals with schizophrenia were found to be negatively associated with levels of symptoms in all of the PANSS factors excluding “reality distortion”, which assesses delusions, hallucinations and unusual thought content. As Minor and Lysaker [Reference Minor and Lysaker53] suggested, it might be that symptoms of reality distortion and cognitive processes share only a small percentage of variance; aiming to improve delusions and hallucinations by addressing metacognitive abilities, therefore, produces limited results. Second, although metacognitive abilities were found to be negatively associated with symptom severity, the item “depression” (PANSS) was found to positively associate with the metacognitive subscale “self-reflectivity”. The authors suggested that this link might reflect the fact that when clients are more aware of their own thoughts, they experience more pain. Third, not all of the studies are consistent in their results regarding the metacognitive subscale correlates. For example, only one study found an association between self-reflectivity and positive symptoms [Reference Lysaker, Carcione and Dimaggio21], while others did not find this association [Reference Hasson-Ohayon, Avidan-Msika and Mashiach-Eizenberg6,Reference Fridberg, Brenner and Lysaker22]. This discrepancy can be explained statistically, as this link was found only at a trend levels [Reference Lysaker, Carcione and Dimaggio21]. The association between negative symptoms and understanding others’ minds was found in one study [Reference Fridberg, Brenner and Lysaker22] but not in another [Reference Vohs, Lysaker and Liffick58]. Perhaps illness duration can explain the discrepancy, as this association was found among patients in a stable or postacute phase of their disorders [Reference Fridberg, Brenner and Lysaker22], as opposed to patients with a first psychotic episode [Reference Vohs, Lysaker and Liffick58]. Our results are also in line with the current literature regarding psychotherapy. Though case studies were not included in the meta-analysis, metacognitive abilities were found to be negatively associated with symptoms [Reference Hillis, Leonhardt and Vohs59] and positively associated with psychosocial functionings [Reference Arnon-Ribenfeld, Bloom, Atzil-Slonim, Peri, de Jong and Hasson-Ohayon60].

4.1. Limitations

Though this meta-analysis highlights the importance of the association between metacognitive abilities and increased levels of symptoms and reduced psychosocial functional outcomes, the results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, as illustrated in Table 1, not all of the studies had independent samples, a factor which might reduce our ability to generalize the current results. Second, a control group of persons without schizophrenia, or with other diagnoses, was not part of this analysis. Third, the present meta-analysis was limited to studies that used the MAS to assess metacognitive abilities. Fourth, although the studies presented in the meta-analysis were conducted in a variety of settings, the majority of them came from the same research group, another factor that may limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings. Finally, meta-analyses are always and inherently limited by the primary studies on which they are based. Specifically, some of the included studies in the current analysis were limited by methodological issues (e.g., incomplete moderator data); these limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the meta-analytic results.

4.2. Clinical implications

Metacognitive deficits are generally considered to constitute a central challenge for people diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders; as such, there are several interventions and guidelines whose goal is to enhance these abilities [Reference Hasson-Ohayon, Kravetz and Lysaker61], such as Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy (MERIT)s [Reference Lysaker, Buck, Leonhardt, Buck, Hamm, Hasson-Ohayon, Lysaker, Dimaggio and Brune11]. By encouraging clients to reflect on their own and others’ mental activities and to recognize their own psychological problems, MERIT aims to allow clients to form a better understanding of their own and others’ mental states and to respond to psychological challenges in a more flexible and adaptive way. Case studies have demonstrated that using MERIT with persons with schizophrenia can increase their metacognitive abilities and reduce their symptoms [Reference Hillis, Leonhardt and Vohs59,Reference Arnon-Ribenfeld, Bloom, Atzil-Slonim, Peri, de Jong and Hasson-Ohayon60,Reference Buck and Lysaker62].

The current study represents the first meta-analysis to investigate the association between metacognitive abilities and outcome measures of global symptomatology and psychosocial functioning among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Our findings showed significant effects for both symptoms and outcome measures, with measure type as moderator. These links emphasize the significant role played by metacognitive abilities in various aspects of the lives of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. It has been observed that a significant reduction in symptoms and an increase in functioning can be effected by enhancing these abilities through psychotherapy.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on the first author's doctoral dissertation in the Department of Psychology, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel. The study was conducted with the support of an internal scholarship. The dissertation was mentored by Prof. Ilanit Hasson-Ohayon and Dr. Dana Atzil-Slonim.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.